'Tit-bits from Temperley' - Durham Bird Club

'Tit-bits from Temperley' - Durham Bird Club

'Tit-bits from Temperley' - Durham Bird Club

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Tit-<strong>bits</strong> <strong>from</strong> Temperley<br />

The <strong>Bird</strong>s of <strong>Durham</strong> Heritage Project<br />

‘Bringing the wildlife of the past, to the people of tomorrow’<br />

‘Tit-<strong>bits</strong> <strong>from</strong> Temperley’<br />

Introduction<br />

2011 marks sixty years since the publication of George Temperley‟s ground-breaking<br />

‘A History of the <strong>Bird</strong>s of <strong>Durham</strong>’, in 1951. Amongst natural historians of the north<br />

east region, his book bears that rare accolade, it does not go by its title, it is known<br />

simply as „Temperley‟. At the time of publication, <strong>Temperley'</strong>s work was at the<br />

„cutting edge‟ of documenting the natural heritage of the area and, in part, for his<br />

efforts on this work, George W. Temperley (GWT) was awarded the British Trust for<br />

Ornithology's highest award, the Bernard Tucker medal.<br />

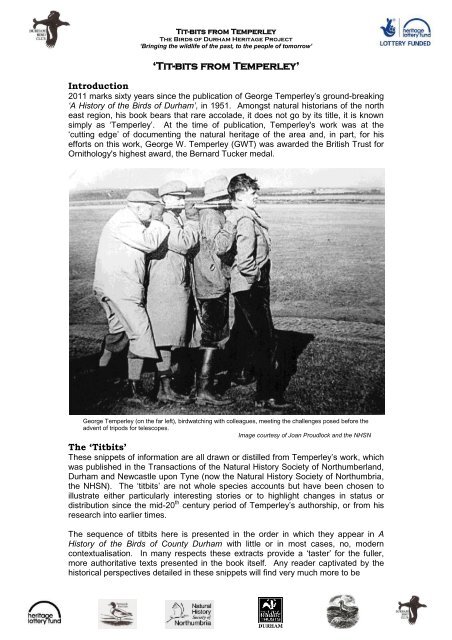

George Temperley (on the far left), birdwatching with colleagues, meeting the challenges posed before the<br />

advent of tripods for telescopes.<br />

Image courtesy of Joan Proudlock and the NHSN<br />

The ‘Tit<strong>bits</strong>’<br />

These snippets of information are all drawn or distilled <strong>from</strong> Temperley‟s work, which<br />

was published in the Transactions of the Natural History Society of Northumberland,<br />

<strong>Durham</strong> and Newcastle upon Tyne (now the Natural History Society of Northumbria,<br />

the NHSN). The „tit<strong>bits</strong>‟ are not whole species accounts but have been chosen to<br />

illustrate either particularly interesting stories or to highlight changes in status or<br />

distribution since the mid-20 th century period of Temperley‟s authorship, or <strong>from</strong> his<br />

research into earlier times.<br />

The sequence of tit<strong>bits</strong> here is presented in the order in which they appear in A<br />

History of the <strong>Bird</strong>s of County <strong>Durham</strong> with little or in most cases, no, modern<br />

contextualisation. In many respects these extracts provide a „taster‟ for the fuller,<br />

more authoritative texts presented in the book itself. Any reader captivated by the<br />

historical perspectives detailed in these snippets will find very much more to be

Tit-<strong>bits</strong> <strong>from</strong> Temperley<br />

The <strong>Bird</strong>s of <strong>Durham</strong> Heritage Project<br />

‘Bringing the wildlife of the past, to the people of tomorrow’<br />

fascinated by in the book itself, and they are heartily recommended to seek out a<br />

copy.<br />

Copies of A History of the <strong>Bird</strong>s of <strong>Durham</strong> by George W. Temperley are available<br />

(for £15) <strong>from</strong> the Natural History Society of Northumbria based at the Great North<br />

Museum at the Hancock, Barras Bridge, Newcastle upon Tyne www.nhsn.ncl.ac.uk/<br />

The illustrations in this article have been contributed by the <strong>Durham</strong> <strong>Bird</strong> <strong>Club</strong> and<br />

include drawings by Ken Baldridge, Chris Donald, Chris Gibbins amongst others.<br />

This document has been developed by volunteers <strong>from</strong> the Natural History Society of<br />

Northumbria and the <strong>Durham</strong> <strong>Bird</strong> <strong>Club</strong>, as a contribution to The <strong>Bird</strong>s of <strong>Durham</strong><br />

Heritage Project.<br />

The <strong>Bird</strong>s of <strong>Durham</strong> Heritage Project (2010-2011) is a multi-faceted project that<br />

sets out to „bring the wildlife of the past to the people of tomorrow’. The <strong>Bird</strong>s of<br />

<strong>Durham</strong> Heritage Project is a joint initiative between, the:<br />

o <strong>Durham</strong> <strong>Bird</strong> <strong>Club</strong> (the Lead Partner)<br />

o <strong>Durham</strong> Upland <strong>Bird</strong> Study Group<br />

o <strong>Durham</strong> Wildlife Trust<br />

o Natural History Society of Northumbria<br />

o Teesmouth <strong>Bird</strong> <strong>Club</strong><br />

As part of the <strong>Bird</strong>s of <strong>Durham</strong> Heritage Project <strong>Durham</strong>, it is the Partners‟ aspiration<br />

to create an all-new, „Temperley‟ fit for the 21 st century, ready for publication in 2011.<br />

The <strong>Bird</strong>s of <strong>Durham</strong> Heritage Project <strong>Durham</strong> is a partnership project supported by<br />

the Heritage Lottery Fund.

Siskin<br />

Tit-<strong>bits</strong> <strong>from</strong> Temperley<br />

The <strong>Bird</strong>s of <strong>Durham</strong> Heritage Project<br />

‘Bringing the wildlife of the past, to the people of tomorrow’<br />

Temperley said that it was noted, “in winter in varying<br />

numbers, it has bred” and it was often associated with<br />

redpoll. The first reference to the species in the County<br />

was <strong>from</strong> the „Allan document‟ of 1791, when it was<br />

referred to as a winter visitor, though not known to breed.<br />

By the first half of the twentieth century, Temperley said, “a<br />

pair or two, occasionally remains to breed.” In ‘A History’,<br />

George Temperley documented that, Hancock (1874)<br />

reported that a nest had been „taken‟ on 7 th May 1848 near<br />

Brancepeth, it contained four eggs.<br />

Hornemann’s (Arctic) Redpoll<br />

George Temperley called this a very rare vagrant. A bird was „taken‟ on sea banks at<br />

Whitburn on 24 April 1855 with a „clod of earth‟. It had been observed for a few days<br />

before this. This was the first spring record of the species for Britain.<br />

Twite<br />

In Temperley‟s time this was an “irregular winter<br />

visitor in small numbers”. He thought that „a few<br />

pairs may still breed on western moors‟ but there<br />

were, then, no recent records. Hancock (1874)<br />

said it was not an uncommon breeder on heather<br />

moorlands in both <strong>Durham</strong> and Northumberland.<br />

Pine Grosbeak<br />

The first British record of this species was once collected at Bill Quay (in modern<br />

Gateshead) „sometime before 1835‟. It was a female-type bird, of a yellowish colour,<br />

possibly a first winter male.<br />

Crossbill<br />

Temperley said that the first reference to the species in <strong>Durham</strong> was <strong>from</strong> Hogg<br />

(1827), who recorded that a „hen bird‟ was taken sometime „before 1810‟ in a garden<br />

at Norton on Teesside. Some years later, on 14 July 1810 a male and a female were<br />

shot in a garden at the same place. Hutchinson, 1840 said, “flocks…not infrequently<br />

met with <strong>from</strong> July to September”. In July, 1828 it was said to be abundant in<br />

woodlands near Lanchester, birds were met there until the following March; a female<br />

killed there 23 rd April and three pairs said to be there on 25 th April. A family party,<br />

including young birds thought to be bred in that area were noted around this time, but<br />

no definite proof of breeding in the County was obtained until 27 years later. Thomas<br />

Grundy found the first nest in <strong>Durham</strong> on<br />

24 February 1856, at Coalburns near<br />

Greenside, in what is now west<br />

Gateshead. On 1 st March, this<br />

contained three eggs. On July 14 th<br />

1856, the same Thomas Grundy found a<br />

pair nesting at High Marley Hill.<br />

Two-barred Crossbill<br />

The first record for <strong>Durham</strong> was of a party of five at Forest Lodge, Wolsingham <strong>from</strong><br />

10 th to 28 th January 1943. They were often in the company of common crossbill,<br />

which were there throughout the winter.

Tit-<strong>bits</strong> <strong>from</strong> Temperley<br />

The <strong>Bird</strong>s of <strong>Durham</strong> Heritage Project<br />

‘Bringing the wildlife of the past, to the people of tomorrow’<br />

Brambling<br />

A regular autumn and winter visitor, in varying numbers often found where beech<br />

mast was abundant or most available. It was particularly numerous in the winter<br />

1934/35, with a flock of at least 500 being seen near Blanchland on 23 December<br />

1934. Nelson (1907), documented the species‟ arrival at the Tees estuary in<br />

October. Temperley mentions Dr Blair‟s observation of a male singing (presumably<br />

at South Shields) on March 17 th 1929.<br />

Corn Bunting<br />

Described by Temperley as a „resident of local occurrence‟, and he commented on its<br />

being „less numerous than formerly‟.<br />

Little Bunting<br />

C. Braithwaite shot a female on the sea walls at Seaton Snook, Teesmouth on 11<br />

October 1902, the first county record. The specimen was later exhibited at a meeting<br />

of the British Ornithologists‟ <strong>Club</strong> on 22 nd October and was at that time, only the<br />

second record for Britain.<br />

Lapland Bunting<br />

At Temperley‟s time, it was considered by him a very rare vagrant, with just a single<br />

occurrence in the region, as noted by Hancock 1874. One was shot out of a flock of<br />

„snow flakes‟ in the neighbourhood of <strong>Durham</strong> in January 1860. This specimen went<br />

to <strong>Durham</strong> University Museum. The actual place of shooting, as revealed by William<br />

Proctor of the Museum, was Whitburn, near Sunderland in January 1860, a location<br />

that still attracts the species today.<br />

Snow Bunting<br />

“Regular winter visitor in varying<br />

numbers”, usually coastally distributed<br />

though less regularly noted on the<br />

moorlands in the west of the county.<br />

GTW thought it less regular inland,<br />

though he highlighted Backhouse‟s<br />

(1885) description of it as “a winter<br />

visitant of regular occurrence” in upper<br />

Teesdale.<br />

House Sparrow<br />

Called an “abundant resident and winter visitor” by Temperley, he identified some<br />

decreases as a result of a change <strong>from</strong> horse-drawn to motor vehicles in the first part<br />

of the 20 th Century.<br />

Woodlark<br />

Edward Backhouse (1834) wrote, “Occasionally killed near <strong>Durham</strong>”. Hancock had<br />

two specimens, of three killed by Thomas Robson near Swalwell in 1844. One, at<br />

South Shields on 3 rd May 1929, found by George Bolam and Dr H.M.S. Blair, stayed<br />

a few days, whilst another was found the following day at Hebburn Ponds.<br />

Tree Pipit<br />

A “summer resident” said Temperley, “well distributed and numerous in areas where<br />

there are deciduous trees”, arriving in late April.

Tit-<strong>bits</strong> <strong>from</strong> Temperley<br />

The <strong>Bird</strong>s of <strong>Durham</strong> Heritage Project<br />

‘Bringing the wildlife of the past, to the people of tomorrow’<br />

Blue-headed Wagtail<br />

“Very rare summer visitor”. Temperley said of it, „no records of breeding in <strong>Durham</strong><br />

since the end of the 19 th century‟, though he did note that it had been recorded on<br />

spring migration in the 20 th Century. Thomas Robson shot the first specimen, a<br />

male, on 1 st May 1836 at Dunston Haugh, with a second bird there being possibly an<br />

attendant female. This was the first British record of the sub-species. Two nests<br />

were collected at this location some years later, in May 1869, birds were suspected<br />

of breeding. Another nest was found on 13 June 1870 at the same place, but this<br />

was trodden on by a horse, on July 5 th . Hancock visited the site, observed the<br />

crushed nest and he saw two or three young birds of another brood, the parents<br />

feeding them. Two of these were shot in the next couple of days, and went to<br />

Hancock. A nest was found on Shibdon Flats, near Dunston Haugh in 1892, the<br />

female being shot „off the nest‟.<br />

Nuthatch<br />

This was a “Resident in very small but increasing numbers” at Temperley‟s time of<br />

writing. The first reference to the species in the county was made by Selby (1831),<br />

who said “I have frequently seen the Nuthatch”, “in the neighbourhood of <strong>Durham</strong>”.<br />

Edward Backhouse (1834), presumably writing of Teesdale, said it was “not very<br />

common”. Hutchinson (1840) considered it “very scarce”. He recorded its<br />

occurrence around <strong>Durham</strong> in woodlands, including Marsden Castle, Houghall, Great<br />

High and Little High Woods, and noted that it was still found in Auckland Park, where<br />

trees of a “great age” occur. Hogg (1845) wrote, “for many years I have observed it<br />

near the City of <strong>Durham</strong>”. He thought that the species<br />

was at its northern limit in Britain in Co. <strong>Durham</strong>.<br />

Hancock documented its regular breeding in Auckland<br />

Park „30-40‟ years ago ... but that it was now “a rare<br />

casual visitant”. From then, until the early part of the<br />

20 th century, it remained a „casual visitant‟, with no<br />

reports of breeding, most sightings were of single birds<br />

in the south of the County, until in 1901 at least one,<br />

possibly, two pairs bred near Wynyard.<br />

Crested Tit<br />

“In the second week of January 1850 a male specimen of the crested tit was shot on<br />

Sunderland Moor”, the record was published in the Zoologist in 1850. It was in the<br />

possession of Mr Calvert of that place, the record was placed by Joseph Duff of<br />

Bishop Auckland 11 March 1850. Calvert was the author of „The Geology and<br />

Natural History of <strong>Durham</strong>, 1884‟. William Proctor had, previous to the above<br />

occurrence, described crested tit as „very rare‟. In Ormsby‟s „Sketches of <strong>Durham</strong>,<br />

1846’, there were vague reports <strong>from</strong> Proctor of three or four birds seen near Witton<br />

Gilbert, „some twenty years ago‟, i.e. around 1825. Hancock‟s later researches<br />

indicate that Duff also had a specimen of crested tit shot at Sunderland Moor, in his<br />

possession so presumably more than one had been obtained. Calvert originally lived<br />

at Sunderland, he later moved to Bishop Auckland. Nelson (1891), corresponding<br />

with Calvert on the topic of crested tit, had learned that two had been shot in 1850,<br />

one was presented to Nelson and this found its way into the collection in the Hancock<br />

Museum.<br />

Willow Tit<br />

Temperley called it a “resident in small numbers”. At Temperley‟s time, the<br />

distribution of this species was very imperfectly known. W.B. Alexander, who saw<br />

two birds at Crimdon Dene on 17 November 1929, first identified it in the field in the

Tit-<strong>bits</strong> <strong>from</strong> Temperley<br />

The <strong>Bird</strong>s of <strong>Durham</strong> Heritage Project<br />

‘Bringing the wildlife of the past, to the people of tomorrow’<br />

county. G. Robinson recorded it near Neasham on 1 August 1930. The first<br />

observation documentation of breeding was actually made by George Temperley<br />

himself, at Ravensworth in the Team valley. In April 1934, he observed a pair<br />

building and nesting in the woods at Ravensworth. Temperley felt that it had bred,<br />

“undetected in the County for an unknown period”, its eggs had been collected under<br />

the name of marsh tit. For example, a clutch of eggs taken at Wild‟s Hill, Rowlands<br />

Gill on 20 th June 1888 <strong>from</strong> a „bored hole‟ was undoubtedly those of willow tit.<br />

Red-backed Shrike<br />

This was a “very rare summer visitor, of which breeding records are few”, according<br />

to George Temperley. In the nineteenth century there were records of the species<br />

nesting at Ravensworth, sometime before 1831. One was shot near Ushaw College,<br />

<strong>Durham</strong> on 10 th September, 1824, this had previously been described as a Woodchat<br />

Shrike, by Thomas Bewick. James Backhouse recorded its having bred near<br />

Newbiggin in Teesdale. The nest was built low in a bush, four or five years before<br />

1885. He recorded a male in the same area in 1885 and again in 1887.<br />

Spotted Flycatcher<br />

George Temperley called it a “summer resident, widely distributed over the eastern<br />

part of the County, wherever there are open woodlands, parks and gardens”.<br />

Temperley also noted that its status did not appear to have changed during the last<br />

century.<br />

Red-breasted Flycatcher<br />

A “very rare and irregular passage migrant”, the first record occurred on 24 th October<br />

1947. This was a day of continuous drizzle at Whitburn Bents, to the north of<br />

Sunderland, where a bird was found by J.R. Crawford. At this time, the species had<br />

been recorded 11 times in neighbouring Northumberland.<br />

Firecrest<br />

Temperley described it as a “very rare straggler”, with “only<br />

one really well authenticated record” at his time of writing. In<br />

1905, Canon H.B. Tristram wrote of possessing a bird shot<br />

by a keeper at Brancepeth, in April 1852. There was an<br />

earlier record documented by Hutchinson, of one shot by<br />

William Proctor near Countyhose, Bowbank on October<br />

1835, but this record was not mentioned in Proctor‟s list of<br />

birds of the county, published in 1846.<br />

Great Reed Warbler<br />

Temperley told of a single record dating <strong>from</strong> the nineteenth century. One was shot<br />

by Thomas Robson of Swalwell, in the mill race which runs down to the Derwent, at<br />

Swalwell, on 28th May 1847. This was the first documented record of the species in<br />

the British Isles.<br />

Reed Warbler<br />

George Temperley documented this as a “rare casual summer visitor”, “records for<br />

County <strong>Durham</strong> only three in number”. The first records of nesting in the region come<br />

<strong>from</strong> between Blaydon and Derwenthaugh, whilst the second breeding record was at<br />

Ravensworth, in the Team valley. The third breeding record was of a nest, exhibited<br />

at a meeting of the Darlington and Teesdale Naturalist‟s Field <strong>Club</strong> on 12 June 1894,<br />

this had been found near Hell‟s Kettles, Darlington that summer. At Temperley‟s<br />

time, it was widely accepted that reed warblers did not usually breed further north<br />

than Yorkshire.

Tit-<strong>bits</strong> <strong>from</strong> Temperley<br />

The <strong>Bird</strong>s of <strong>Durham</strong> Heritage Project<br />

‘Bringing the wildlife of the past, to the people of tomorrow’<br />

Mistle Thrush<br />

Temperley said of it, “a common resident”. “In autumn and winter, flocks visit more<br />

open country to feed on the field”. Hogg (1827) said that Bewick had reported that<br />

this species was rare in the north around 1800, though numbers had increased very<br />

much by Hogg‟s time of writing. In the bad winter of February/March 1947, this<br />

species suffered major losses, being almost wiped out in some areas. It was still<br />

decidedly scarce by 1950.<br />

Whinchat<br />

Described by Temperley as a “widely-distributed and, in places, fairly common<br />

summer resident; also a passage migrant”. He said it bred on clear fells, thickets and<br />

hedgerows in the low country and scrubby land on the fringes of the moors. At his<br />

time of writing, George Temperley described it as particularly numerous in the middle<br />

and upper portions of Teesdale, where it bred to an altitude of 1000 feet.<br />

Black Redstart<br />

“Once a rare vagrant, now a regular winter visitor” is how Temperley described it. He<br />

noted that it was more frequently noted in the 1940s and early 1950s. Prior to Selby<br />

(1831), there were no known records in Northumberland or <strong>Durham</strong> and Hancock<br />

(1874) thought it extremely rare as a winter visitor; however he<br />

also documented a record of its breeding in <strong>Durham</strong> the first<br />

such occurrence in Britain. This concerned a pair that nested<br />

in 1845, in the garden of the Rev. James Raines in <strong>Durham</strong><br />

City. The nest site was at Crook Hall on the north bank of the<br />

Wear, half a mile below Elvet Bridge, in <strong>Durham</strong> City. Proctor<br />

took the nest and he documented it as containing five eggs, in<br />

the summer 1845. The nest had been built in a cherry tree<br />

trained up a wall of the garden. Canon B. Tristram noted, in the vice-county history<br />

of <strong>Durham</strong>, that the birds had been shot. The identification of the nest and eggs was<br />

confirmed by Guy Charteris at the British Museum.<br />

Nightingale<br />

Temperley thought that there were no reliable records of truly wild birds but he<br />

documented an account of breeding birds at Stampley Moss. In the summer of 1931<br />

a Nightingale was found singing at Stampley Moss (adjacent to Thornley Woods),<br />

close to Rowlands Gill. It was heard singing <strong>from</strong> 24th April to 23rd June. The<br />

singing bird was seen by many observers, including George Temperley himself, and<br />

on a few occasions a pair were seen, indeed one rumour suggested that the birds<br />

nested but that the eggs were taken. Over 100 people were said to have come to<br />

hear the birds, which led to rowdy scenes and stones being thrown at the birds. This<br />

probably constitutes the first birdwatching „twitch‟ in the region. It was later found<br />

that the Reverend Father F. Kyute of St. Agnes, Crawcrook had, on more than one<br />

occasion, lost or released captive Nightingales. In a letter written in 1932, he stated<br />

that he had released two pairs at Alnwick in March 1931. Later in 1931 a bird was<br />

reported singing at Bradley Hall close to Crawcrook, and Father Kyute said that he<br />

had released birds there in both 1928 and 1929. This is the only known breeding<br />

attempt by the species in the Vice-county of <strong>Durham</strong>.<br />

Alpine Swift<br />

Temperley called it a “rare migrant”. The first county record, one on the coast near<br />

Souter Point, was seen by Abel Chapmen on 24 July 1871. Chapmen was<br />

accompanied at the time by his uncle George Crawhall, who was familiar with the

Tit-<strong>bits</strong> <strong>from</strong> Temperley<br />

The <strong>Bird</strong>s of <strong>Durham</strong> Heritage Project<br />

‘Bringing the wildlife of the past, to the people of tomorrow’<br />

species <strong>from</strong> the continent. In the preceding months birds had been noted in Norfolk,<br />

Essex and Kent.<br />

Nightjar<br />

It was called a “summer resident; not numerous and very<br />

local in its distribution” by Temperley. He said, “breeds about<br />

the fringes of the moorlands in the western part of the<br />

County”, “less frequently on scrubby open ground, amongst<br />

heather, gorse or young trees”, in the east. He said that it<br />

was probably more common in Hutchinson‟s time (1840s) but<br />

George Temperley thought it unlikely to have been common<br />

in the previous 150 years. A nightjar breeding on the<br />

outskirts of South Shields in 1933 and 1943 was seen every<br />

night within three miles of the town. Temperley also said that on the Derwent it can<br />

still be found at favoured spots a few miles <strong>from</strong> its confluence with the Tyne.<br />

Blue-tailed Bee-eater (Meriops superciliosus philippinus)<br />

This species was recorded by Hancock as having been shot near Seaton Carew in<br />

1862, but Temperley said that it was not admitted to the British list and he believed<br />

that the specimen was shot at Branch End on the Yorkshire side of the Tees,<br />

presumably an escaped bird or a deliberate hoax? This sub-species is native to<br />

India, south east Asia east to New Guinea and has not been recorded in Britain.<br />

Roller<br />

There were two records in the Victorian period. One, according to Selby (1831) was<br />

shot near South Shields, sometime before 1831. The second record, was also of a<br />

bird that was shot, in the Hunwick Estate, in the Wear valley, on the 25 th or 26 th May<br />

1872, by H. Gornall of Bishop Auckland.<br />

Kingfisher<br />

Temperley said, “A resident, more common than is usually<br />

supposed”. He mentioned its moving to the coast in the autumn and<br />

winter, and records sightings of, presumably dispersing juveniles, in<br />

autumn at unusual locations such as Hebburn Ponds, Saltwell Park<br />

Lake (Gateshead) and Darlington South Park Lake. A bird found on<br />

Back Redheugh Road, Gateshead on September 1943 had been<br />

ringed at Kirkley Mill near Ponteland, Northumberland.<br />

Green Woodpecker<br />

George Temperley said of it a “not uncommon resident in wooded districts”. He<br />

recorded a change in its status during his „recorded times‟. Until the early 1800s, he<br />

thought that it must have been a common and widespread species, this was followed<br />

by a severe decline, after which it was considered „rare‟ for quite a period of time.<br />

Not until well into the 1900s did a significant increase in numbers occur again, and,<br />

<strong>from</strong> then on, the species spread quickly after its first burst of population expansion<br />

during the first two or three decades of the 20 th century.<br />

Great Spotted Woodpecker<br />

George Temperley said that it was rare in the early part of the 1800s, and it was not<br />

included in some early catalogues of species, e.g. Hogg (1824) had never seen one<br />

in north Cleveland, indicating that it was genuinely scarce in that area. Edward<br />

Backhouse thought it less plentiful than green woodpecker Picus viridis which was<br />

then not uncommon. Hogg (1840) stated that it was “an exceedingly rare bird in the<br />

County”. Sclater, at Castle Eden, saw one there on 10 February 1876, only the third

Tit-<strong>bits</strong> <strong>from</strong> Temperley<br />

The <strong>Bird</strong>s of <strong>Durham</strong> Heritage Project<br />

‘Bringing the wildlife of the past, to the people of tomorrow’<br />

he had noted in that area in 16 years. By Hancock‟s, time of writing, it appeared<br />

somewhat more common, and by then he thought it more common than the green<br />

woodpecker. From specimens in the Hancock Museum, it is clear that it bred at<br />

Maiden Castle, <strong>Durham</strong> City in 1863 and at Cleadon (a juvenile) by 1880. By 1905,<br />

Tristram reported that it was “occasionally met with at all times of the year in the<br />

wooded parts of the County and breeds regularly in some localities”. Temperley<br />

thought that this was the beginning of the spread of the British race into County<br />

<strong>Durham</strong>, where it was established in the Derwent valley during the early 20 th century.<br />

Temperley, himself, first saw it at Ravensworth in 1921 and by the early 1950s; it was<br />

found in all of the County‟s major woodlands.<br />

Lesser Spotted Woodpecker<br />

It was documented as a „very rare visitor‟, with „one<br />

record of breeding‟. “One shot ‘some years ago’ at<br />

Stockton Bridge”, according to Hogg 1845. Robson<br />

recorded one that one had been obtained in Gibside,<br />

with no definite date, but „about 1888‟. There were<br />

anecdotal reports of birds in Gibside and Bradley Park<br />

during the mid 1880s. Temperley‟s only breeding record<br />

was of a pair nesting in West Cemetery, Darlington in<br />

1934.<br />

Wryneck<br />

George Temperley thought it “now a rare casual visitor”, though it was formerly a<br />

summer resident. “Used to be pretty common”, said Selby in 1831. Hutchinson<br />

(1840) said that woods near <strong>Durham</strong> were a „favourite resort‟. A number of authors<br />

recorded it being persecuted in the northeast. Edward Backhouse (1835) said it was<br />

„not uncommon‟ in the Sunderland area. Hogg (1845) thought it „not uncommon‟ in<br />

south east <strong>Durham</strong>, and still not uncommon around <strong>Durham</strong> in 1846 (Proctor, 1846r).<br />

The species bred in a garden in Cleadon House between 1813 and 1818, and it also<br />

occurred as a passage migrant around South Shields/Whitburn/Cleadon at the time.<br />

Robson (1896) said it was common in the lower Derwent valley up to 1842, breeding<br />

took place in 1834 at Swalwell, with a male shot in 1836 in Axwell Park. From the<br />

middle 1800s, it was much less common as a passage migrant The last records in<br />

Temperley refer to its loss as a breeding bird in Cumberland, Westmorland and<br />

Lancashire, and of its being much less common even further south.<br />

Snowy Owl<br />

One record in Temperley, courtesy of Hancock, who said that on 7 November 1858,<br />

„a fine specimen‟, was shot at Helmington near Bishop Auckland, and it was in the<br />

possession of Henry Gornall „of that place‟.<br />

Tengmalm’s Owl<br />

There were three records of this species for the County documented in Temperley.<br />

Hancock reported buying a fresh specimen in a poulterer‟s shop in Newcastle, which<br />

had been shot near Whitburn on 11 th or 12 th October 1848. This was reported in the<br />

Zoologist of 1850, as being killed on the sea coast near Marsden in October 1848.<br />

The specimen is in the Hancock Museum. Hogg recorded that one was shot in<br />

November 1861 near Cowpen, to the northeast of Norton. One was shot at North<br />

Hylton on 4 October 1929. This specimen was presented to the Natural History<br />

Society and the specimen is in the Hancock Museum.

Tit-<strong>bits</strong> <strong>from</strong> Temperley<br />

The <strong>Bird</strong>s of <strong>Durham</strong> Heritage Project<br />

‘Bringing the wildlife of the past, to the people of tomorrow’<br />

Little Owl<br />

Temperley said that at his time of writing, it was “a resident in increasing numbers, as<br />

yet chiefly confined to the east of the County”. He said at 1951, that it was<br />

“spreading rapidly”. The first specimen of a bird in <strong>Durham</strong> was shot at Chilton Moor<br />

near Fencehouses in April 1918.by T. Harrison a gamekeeper of New Seaham, and<br />

was identified by Dr. H.M.S. Blair. In 1931, F.J. Burlenson and J. Bishop reported<br />

that a pair had attempted to nest near Rushyford, two to three years previously, the<br />

actual date being 1926.<br />

Merlin<br />

A “resident in small numbers”, “breeding sporadically on the moors in the western<br />

portion of the County” according to George Temperley. Once persecuted, as noted<br />

by Hancock (1874), “this beautiful little falcon is rapidly disappearing, by the hands of<br />

the gamekeeper”. James Backhouse (1885) said, “still every year, one pair or more<br />

of these elegant little falcons nest on the high moors, both on the Yorkshire and<br />

<strong>Durham</strong> side of the Tees”. Temperley mentioned an estate in Weardale, where birds<br />

were tolerated, up to three pairs, and likewise an estate in the Derwent valley.<br />

Red-footed falcon<br />

Temperley called this a “very rare vagrant”. There were two records up to George<br />

Temperley‟s time, an adult male shot at Trow Rocks, South Shields in October 1836,<br />

the specimen going to the Hancock Museum. Secondly, there was a record of a<br />

female or an immature male that was seen at Seaton Carew on 30teh October 1949,<br />

a fortnight previously two red-footed falcons had been on Holy island in<br />

Northumberland.<br />

Golden Eagle<br />

Temperley thought that in the days when golden eagles bred on Cheviot and in the<br />

Lake District, i.e. in the 18 th Century, that wandering birds would have occasionally<br />

visited <strong>Durham</strong>. He mentioned several examples of this but was uncertain as to<br />

whether „the eagle‟ referred to in some records was golden eagle or white-tailed<br />

eagle. Some early examples were proven to be „white-tails‟, e.g. that of Hogg at<br />

Teesmouth on 25 th November 1823. A definite record came <strong>from</strong> the „Gentleman‟s<br />

Magazine‟ for 1756, which, according to George Temperley, on p.490 reads, “on 17<br />

October 1765, a golden eagle was shot at Ryhope, Sunderland, wing span 7 feet and<br />

six inches”. Canon H.B. Tristram, writing in 1905, recounted the tale of some 30<br />

years previous, when in November he was crossing <strong>from</strong> Teesdale to Nenthead on<br />

foot, over Killhope Fell, when fog cam down and he sat down to rest. On rising as<br />

the fog lifted, he realised that an eagle was perched on a post within a few feet of<br />

him.<br />

Buzzard<br />

Temperley said that it was a “rare occasional visitor, except in upper Teesdale,<br />

where of late years, it has occurred fairly regularly”. Temperley thought that it would<br />

breed in Teesdale if not „molested‟. Hutchinson (1840) highlighted the contrast in its<br />

status <strong>from</strong> elsewhere in England, saying specimens of rough-legged buzzard… and<br />

honey buzzard…. were more frequently encountered in Co. <strong>Durham</strong> than was<br />

common buzzard. Hancock in 1874 further highlighted the persecution of this<br />

species. He told of several specimens, in the collections of Mr Smurthwaite of<br />

Staindrop, which had been taken in that neighbourhood. Hancock himself had one<br />

that was taken at Ravensworth in February 1837. The only suggestion that buzzard<br />

was ever common, comes <strong>from</strong> Canon Tristram (1905), who said, within living<br />

memory, “it regularly bred in many parts of the County but has been exterminated by<br />

game preservers aided by egg-collectors”. At 1951, Temperley said that it was not

Tit-<strong>bits</strong> <strong>from</strong> Temperley<br />

The <strong>Bird</strong>s of <strong>Durham</strong> Heritage Project<br />

‘Bringing the wildlife of the past, to the people of tomorrow’<br />

an uncommon sight for a single or even a pair of birds to be seen in the breeding<br />

season. Nest building had taken place, but not continuing to the egg-laying or<br />

incubation stage.<br />

Montagu’s Harrier<br />

“For many years merely a very rare casual visitant, but for the last four (written by<br />

Temperley in 1951) a summer resident”. This species was probably a rare passage<br />

migrant and rare intermittent breeder in the 19 th century. In the 20 th Century, in May<br />

1929, an unidentified hawk was at Wolsingham Park Moor. The bird was trapped on<br />

15 th May and proved to be an adult male Montagu‟s Harrier; there was no sign of a<br />

second bird. Subsequently, successful breeding took place in 1947, 1948, 1949 and<br />

1950 and then onwards for a few more years. Possibly two pairs were present in<br />

1947, keepers reported three juveniles present until the latter part of August. In<br />

1948, three pairs bred on same moors and in 1949, one pair bred successfully, with<br />

single birds elsewhere in other parts of the County. In 1950, one pair raised four<br />

young with at least one other nest built.<br />

White-tailed Eagle<br />

Temperley said of it, “a very rare casual visitor”. Selby (1831) stated that several had<br />

been killed in Northumberland and neighbouring counties. Hogg told of one shot at<br />

Teesmouth 5 th November 1823 by L. Rudd, this bird was shot on the Yorkshire side,<br />

but Edward Backhouse stated that it had been previously recorded at Norton, near<br />

Hartlepool. This bird was originally reported as a golden eagle but re-identified <strong>from</strong><br />

the corpse. A possible sea eagle was reported in September 1837 near Cocken on<br />

the Wear….‟but it could never be approached within gunshot‟, the probability is that<br />

this was a white-tailed eagle. Hancock (1874), gave a <strong>Durham</strong> record <strong>from</strong><br />

Ravensworth Park. In a letter to George Bolam, in January 1916, C.E. Milburn talked<br />

of two white-tailed eagles at Teesmouth in October 1915, for a few nights they<br />

roosted on a headland like slagheap near Grangetown, on the Yorkshire side of the<br />

Tees. Milburn said he watched one of these cross over to Greatham without it once<br />

flapping its wings.<br />

Honey Buzzard<br />

This was called “a rare casual visitor in spring and<br />

autumn, formerly an occasional summer resident”.<br />

George Temperley documented that Selby had<br />

considered it “one of the rarest of the Falconiidae”,<br />

and he gave no <strong>Durham</strong> records. Edward<br />

Backhouse, in 1834, wrote of „several specimens of<br />

this elegant bird “having lately been shot in various<br />

parts of this county”. Hutchinson (1840) said that<br />

autumn honey buzzards, were “frequently met with” in<br />

September and October, but their stay was short; it<br />

was seldom observed at other times of the year. In<br />

1874, Hancock, said, “It is certainly now, according to my experience, one of the<br />

commonest large birds of prey”, but this may rather better reflect the scarcity of other<br />

large birds of prey at the time. He documented the „taking‟ of 25 specimens between<br />

1831 and 1868 in the two counties of Northumberland and <strong>Durham</strong>. He also noted<br />

that “it occasionally breeds in the district”, but gave no details of this breeding in<br />

<strong>Durham</strong>. However, it was well documented as breeding in the Derwent valley in<br />

1897. The Honey Buzzard is mentioned at some length by both Robson (<strong>Bird</strong>s of the<br />

Derwent Valley, 1896) and Temperley in their respective texts. The first nest was<br />

found in the autumn of 1896, though according to local anecdotes birds may have<br />

been present for some years previously. In 1897 Thomas Robson himself found the

Tit-<strong>bits</strong> <strong>from</strong> Temperley<br />

The <strong>Bird</strong>s of <strong>Durham</strong> Heritage Project<br />

‘Bringing the wildlife of the past, to the people of tomorrow’<br />

nest „some 60 feet up‟ a beech tree, it apparently contained two young honey<br />

buzzard and three pieces of wasp's nest. A pair was once again present in 1898,<br />

though they did not nest. However, in 1899 the locally nicknamed "Big Hawks"<br />

produced two young. This proved to be the last confirmed breeding in the area. It is<br />

conceivable that birds may have nested a little higher up the Derwent valley in 1898,<br />

for birds were noted at Shotley Bridge and a bird of the year was shot nearby.<br />

White Stork<br />

Classified as a “very rare vagrant” by Temperley, at his time of writing, there were<br />

just three documented records. Two birds were at Cowpen Marsh in the spring of<br />

1830, one of these was shot. The second occurrence was of a bird shot at Morton<br />

Tinmouth, near Gainford on 14 th February 1884. The third bird was one that<br />

frequented the southeast <strong>Durham</strong> and northeast Yorkshire areas <strong>from</strong> October to<br />

December 1938, most of the time it spent on the south side of the Tees, but it was<br />

also seen at Hurworth Burn Reservoir and at Hartlepool.<br />

Black Stork<br />

Temperley documented two records, of this species which he called a “very rare<br />

vagrant”. One of these was shot at Greatham Creek in August 1862, the specimen<br />

being sent to the Hartlepool Museum and the second was of one caught alive, after a<br />

gale, at the South Docks, Sunderland in October 1880.<br />

Spoonbill<br />

“A very rare vagrant” according to Temperley, the first<br />

record, was recorded by Hogg (1845), “a single spoonbill<br />

having been killed on the Tees Marshes and this was<br />

some years ago”. The second record was of a female in<br />

its first year plumage, which was shot at Seal Sands in<br />

1929. The third record was of one passing within 60<br />

yards of Seaton Carew golf links, on 11 th April 1941.<br />

This bird was well-observed and seen to be a full adult. The final record in<br />

Temperley‟s time, was of one in the Tees Estuary on 19 th April 1951.<br />

Glossy Ibis<br />

This was a “very rare vagrant” at the time of the publication of ‘A History of the <strong>Bird</strong>s<br />

of <strong>Durham</strong>’ (1951) with just two records at that time. The first of these was of a bird<br />

killed near Sunderland, in 1831; it was actually shot at Ryhope to the south of<br />

Sunderland and the specimen sent to the Sunderland Museum. The second one<br />

was shot at Billingham Bottoms, on 25 th November 1900, this was reported to have<br />

been an adult, but the sex was not noted.<br />

Mute Swan<br />

Temperley called it “a common resident wherever there are suitable lakes, ponds or<br />

rivers, breeding freely where protection is afforded”. He said that at that time, 1951,<br />

it was increasing in numbers. He pointed out that for many centuries the mute swan<br />

was semi-domesticated in England though originally of wild stock, he pointed out that<br />

at his time of writing, few birds were kept in pinioned flocks, most birds being „wild‟ or<br />

„feral‟.<br />

Red-breasted Goose<br />

Temperley, did not officially include this species in his list of birds for <strong>Durham</strong>, but he<br />

mentioned it on the strength of Hancock (1874) documenting two <strong>Durham</strong> records.<br />

Marmaduke Tunstall had a specimen in collection, but also mentioned a bird taken<br />

alive in the neighbourhood of Wycliffe-on-Tees. This later bird was kept alive until

Tit-<strong>bits</strong> <strong>from</strong> Temperley<br />

The <strong>Bird</strong>s of <strong>Durham</strong> Heritage Project<br />

‘Bringing the wildlife of the past, to the people of tomorrow’<br />

1785. it is not known exactly where the individual was captured. Many of Tunstall‟s<br />

specimens went to the Hancock Museum. The second of Hancock‟s records came<br />

<strong>from</strong> John Hogg (1845), who said that two specimens had been seen at the mouth of<br />

the Tees „of late years‟. One of these was shot at Cowpen Marsh, though the exact<br />

details are not known. Temperley expressed his doubts about the veracity of this<br />

record.<br />

Canada Goose<br />

Temperley recorded that this introduced species was then<br />

living in a feral state in the County, with some birds being<br />

escapes <strong>from</strong> captivity.<br />

Ruddy Shelduck<br />

George Temperley thought that this was a very rare vagrant. One was shot <strong>from</strong> a<br />

“small flock” in the „interior‟ of the County‟ and brought to a Mr. Cullingford for<br />

presentation on September 23 rd 1892. There was a reported influx to Britain during<br />

June-September 1892.<br />

Blue-winged Teal<br />

Temperley told of Nelson recording a specimen that was shot at Cowpen Marsh on<br />

3 rd September 1881.<br />

Garganey<br />

Temperley said of it, a “summer visitor in very small but<br />

increasing numbers, which breeds occasionally”. Nelson<br />

(1907), recorded it as breeding at Teesmouth between<br />

1880 and 1887, and again in the same place some years<br />

later in 1914. It bred at Teesmouth again in 1927 and<br />

1928, and in 1933, Bishop saw three males together in<br />

April and was „sure it was nesting‟.<br />

Pochard<br />

Temperley called it “a rare summer resident”, “common as a spring and autumn<br />

visitor” but rare in winter, he thought it a species of „inland waters‟. Hogg (1845),<br />

quoted it as being „not uncommon‟ at Teesmouth in winter, but never numerous.<br />

Slightly later, Tristram (1905) wrote of its being „frequently met with during winter‟.<br />

He also said it had bred at Teesmouth. The first definite breeding record came <strong>from</strong><br />

a pond on an old brickfield site in south east <strong>Durham</strong> in 1903. The nest was found<br />

there by J. Bishop (Bishop, 1904). It also bred at the same site in 1919, then on an<br />

annual basis for some years afterwards, one or two pairs being present, but the site<br />

was lost in the early 1940s. Before the draining of the west Rainton Marsh, in 1928,<br />

a few pairs of Pochard bred there, young being noted in 1924, nests in 1925, 1926,<br />

1927 and 1928. In 1946, two pairs, reared young at a brick-field in northeast <strong>Durham</strong><br />

these birds were seen by Temperley, and bred again in 1948.<br />

Ferruginous Duck<br />

There was just one record of this species at Temperley‟s time. On April 3 rd 1948, a<br />

male was found on Hebburn Ponds, associating with a pair of Tufted Duck. It was<br />

seen by Temperley on 7 th April, it was wary and he believed it to be a wild bird; it was<br />

not present on 8 th .<br />

Cormorant<br />

Temperley called this “a very common resident on the north-east coast” but that it did<br />

not normally breed on the <strong>Durham</strong> coast. He quoted the earliest records as being

Tit-<strong>bits</strong> <strong>from</strong> Temperley<br />

The <strong>Bird</strong>s of <strong>Durham</strong> Heritage Project<br />

‘Bringing the wildlife of the past, to the people of tomorrow’<br />

<strong>from</strong> 1544, by William Turner, who stated “I have seen mergi nesting on sea cliffs<br />

about the mouth of the Tyne river”, this is not a specific reference to the <strong>Durham</strong> side<br />

of the river, and may refer to Tynemouth, but possibly the Marsden area.<br />

Manx Shearwater<br />

“Passage migrant off the coast”, with “one<br />

record of attempted breeding”. The<br />

attempted breeding took place at Marsden<br />

Rock. During the summer of 1939, an egg<br />

was collected <strong>from</strong> under over-hanging<br />

vegetation on top of the Rock. It was<br />

identified by Dr HMS Blair, some five years<br />

later as being that of a „manxie‟. Temperley<br />

speculated that birds might have bred on the<br />

summit for years without being known about.<br />

Fulmar<br />

Temperley described it as “a resident, breeding on the coast in increasing numbers”.<br />

For many years, up to the early part of the 20 th century, it was a rare casual migrant.<br />

The first record is referred to by Edward Backhouse (1834), who said, that one was<br />

killed near Sunderland in 1814. Around 1919, the pattern of occurrences changed,<br />

with odd birds „haunting‟ the cliff tops of the north-east coast, birds being noted onshore<br />

on the Farnes and Bempton that spring. In 1924 or 1925, birds began to<br />

frequent cliffs at Marsden Bay and Frenchman‟s Bay at South<br />

Shields; there were 12 there in spring of 1926, most of these<br />

were shot. In 1927, 22 were counted and one nestling noted on<br />

the mainland cliff of Marsden Bay. In 1928, 24 adults were<br />

present, eight pairs laid eggs and seven well-grown young were<br />

seen on the Rock, with others on the main cliffs. There was<br />

then a period of steady growth and colony expansion. A survey<br />

in June 1945 found 36 adults on ledges; 48 young on ledges in<br />

mid-August 1945.<br />

Black-necked Grebe<br />

Temperley said that this was “normally a very rare winter visitor” however he also<br />

recorded a then, „recent breeding record‟. He said that it was the rarest of the grebes<br />

in County <strong>Durham</strong> and related that after „recent‟ summer records in Northumberland<br />

and North Yorkshire in the early 1940s, he was not surprised when black-necked<br />

grebes bred in County <strong>Durham</strong> in 1946 and 1947. On 3 rd June 1946, two adults were<br />

present on a flooded brick-field in north east <strong>Durham</strong>. On 23 rd July they were feeding<br />

a juvenile, with two juveniles there on 28 th and a third adult present on 9 August<br />

1946. <strong>Bird</strong>s were still present on 22 August. On 18 August 1946, at another site in<br />

north east <strong>Durham</strong>, two fledged juveniles were seen by Dr H.M.S. Blair. These were<br />

not believed to be the birds <strong>from</strong> the other breeding site. In 1947, a pair again bred<br />

at the first of these sites, rearing two young. In 1948, just one of the adults appeared<br />

at the site, likewise, in 1949 and 1950.<br />

Stock Dove<br />

Temperley called this a “common resident”, though he felt it “rather local” as a<br />

breeding species. He said that it was unknown in <strong>Durham</strong> until around 1860, as in<br />

the rest of northern England, though at his time of writing, 1951, it had become a<br />

well-established resident. This species was not mentioned by the early chroniclers<br />

and authors. It was first documented by Tristram (1905), having been recorded in<br />

1862 or 1863 at Elton, and it was possibly breeding there by 1865, and definitely so

Tit-<strong>bits</strong> <strong>from</strong> Temperley<br />

The <strong>Bird</strong>s of <strong>Durham</strong> Heritage Project<br />

‘Bringing the wildlife of the past, to the people of tomorrow’<br />

by 1867. Gurney (1876) said he discovered it at Castle Eden Dene in May 1866,<br />

describing the taking of specimens at Darlington and High Coniscliffe, he speculated<br />

on its becoming abundant in the County, “before long”. Hancock (1874) found a nest<br />

at Castle Eden Dene in 1871, shortly after it was noted breeding at Brancepeth and<br />

the Ravensworth Estate, in 1874. By 1877, stock doves were considered fairly<br />

common in Castle Eden Dene.<br />

Turtle Dove<br />

Temperley called it “a rare and irregular passage migrant”. He said it was suspected<br />

of breeding occasionally in the South of the County, though this was not proven.<br />

Edward Backhouse (1834) described it as “rare”. He reported that it was<br />

occasionally killed near Darlington and he documented one caught alive at West<br />

Hendon, Sunderland. Hogg (1845), said it was „very rare‟ in south east <strong>Durham</strong>, but<br />

that he had a female that had been shot on 14 September 1829 at Norton and he<br />

also recorded one shot 26 years before in the same area, which may have been the<br />

first documentation of the species for County <strong>Durham</strong>.<br />

Pallas’ Sand-grouse<br />

Temperley called it “a very rare irregular summer visitor”. He documented two main<br />

invasions, both in the 19 th century, these occurred in 1863 and 1888. The first<br />

records of the species in the County occurred in May 1863, when Hancock<br />

documented the „taking‟ of 22 or 23 specimens in Northumberland and <strong>Durham</strong>.<br />

These included: a female at Ryton on 2 nd June, out of a flock of about 16 birds; on<br />

30 th June, a male was shot at Cowpen out of a flock of around 12; on 24 November<br />

1863, a female was taken to William Proctor, in <strong>Durham</strong>, after being killed by flying<br />

into wires. This bird came <strong>from</strong> one of two flocks near Whitburn in the middle of<br />

June. There was also a flock of 16 or 17 birds at Port Clarence on 13 May 1863.<br />

Tristram described the 1863 invasion “<strong>from</strong> the month of May to July many more<br />

were seen and taken on the coast, and on the sand hills of Seaton and Cowpen<br />

Marshes. I saw a flock of very nearly twenty for several days, but I regret to say that<br />

most of them were shot”. Nelson (1907) recorded three birds were taken “on the<br />

sand near the Teesmouth” in late August 1876.<br />

In 1888, a larger scale influx than in 1863 took place. Large flocks occurred in<br />

Yorkshire and Northumberland, and at least two pairs bred in Yorkshire. Detailed<br />

records included: six at Teesmouth about the middle of May; two shot at Whickham<br />

during May 1888; two seen about half a mile out of <strong>Durham</strong> on 25 May; two shot at<br />

Warden Law, May; and, six in a field between Bishop Auckland and Byers Green on<br />

3 June. Tristram (1905), writing of the 1888 invasion, said that numbers were shot all<br />

over the County. One taxidermist, Mr Cullerford, of <strong>Durham</strong>, had over 60 specimens<br />

brought to him. A note in the Zoologist for 1888, told of “sand-grouse breeding in<br />

<strong>Durham</strong>”, “a nest with three young is near here”. Temperley had no confirmation of<br />

this breeding record but it seemed credible as birds bred in Yorkshire. In 1890, a<br />

further small invasion occurred, with one bird being shot near Swalwell on 28 May<br />

1890. Three days previously a male was shot at Whickham and around the same<br />

time a female was picked up alive near Blaydon.<br />

Woodcock<br />

Temperley called it a “resident and winter visitor”. The first<br />

evidence of this species in County <strong>Durham</strong> comes <strong>from</strong><br />

Tunstall‟s manuscript, which recorded the shooting of a young<br />

bird, two-thirds grown, in September 1782 near <strong>Durham</strong>.<br />

Selby (1833) thought it mainly a winter visitor, though „regular‟

Tit-<strong>bits</strong> <strong>from</strong> Temperley<br />

The <strong>Bird</strong>s of <strong>Durham</strong> Heritage Project<br />

‘Bringing the wildlife of the past, to the people of tomorrow’<br />

at other times of the year. By 1840, Hutchinson was documenting it as having bred<br />

in <strong>Durham</strong>, with three young out of a brood of four being shot near Allensford on the<br />

Derwent in May 1830. In the 1860s and 1870s, Temperley recorded that several<br />

nests were found in the Derwent valley and elsewhere. By 1874, Hancock said it<br />

was breeding in the area of the Tyne, around the confluence with the Derwent and<br />

was not as uncommon as previously supposed. By Temperley‟s time of writing, he<br />

noted it as nesting in all suitable woodlands, often close to centres of population, e.g.<br />

at Ravensworth Castle, in the Team valley and at Gibside. An enquiry into its status<br />

as a breeding bird in Britain, reported that 12 pairs nested in 7000 acres near<br />

Stockton-on-Tees and 10-12 pairs nested annually in a 2000 acres estate near<br />

Chester-le-Street.<br />

Great Snipe<br />

Temperley said it was a “very rare passage migrant”, though in relative terms, much<br />

more common in the past than in modern times. The first county record is one<br />

mentioned by Hogg (1827) of one shot flying over the Tees, “about four years ago”.<br />

Selby (1831) recorded it as a rare and occasional visitant; several were shot during<br />

the dry autumn of 1826 in a marsh near Sedgefield. Hutchinson (1840) wrote that<br />

„solitary individuals had been shot in other parts of the County in autumn and winter‟.<br />

Hancock (1874) gave ten records for Northumberland and <strong>Durham</strong>, three of these<br />

<strong>from</strong> <strong>Durham</strong>. One was near Thornley in September 1874; one was near Witton-le-<br />

Wear in October 1830 and one near Bishop Auckland in 1893. In addition, one was<br />

shot in early October 1885, at Burnledge in Weardale and another shot „about<br />

fortnight ago‟. Tristram (1905) said that it was very occasionally seen at Darlington<br />

Sewage Farm in September!<br />

Red-necked Phalarope<br />

Temperley said it was “a very rare autumn passage migrant”. None of the Victorian<br />

chroniclers of <strong>Durham</strong>‟s birds mentioned this species. Hancock (1874) gave no<br />

records but there was by Temperley‟s time, a specimen, of a juvenile, in the Hancock<br />

Museum that was labelled as taken at South Shields, but no date was attached to<br />

this. The first definite record of the species seems to be <strong>from</strong> 23 October 1881 at<br />

Teesmouth. Nelson (1907) picked up a dead bird on that date. One, an immature<br />

was shot on a pond near the Golf-house at Seaton Carew on 6 September 1901.<br />

Another one was near Graythorp Shipyard on 2 October 1943.<br />

Temminck’s Stint<br />

Temperley described it as a “very rare spring and autumn passage migrant”. The<br />

first documented record for <strong>Durham</strong> was by Edward Backhouse (1834), who said it<br />

was „rare‟ though one had been shot at Seaton Snook in the autumn of 1833 it was<br />

shot in the company of a small flock of grey plover. One was also killed on the Kings‟<br />

Meadow, an island in the middle of the River Tyne near Dunston, on 25 th May 1843.<br />

Pectoral Sandpiper<br />

Temperley, called it “a very rare casual”. He documented three records and<br />

discussed the doubts over the first of these, a bird shot in October 1841; very near<br />

Hartlepool by Dr. Edward Clark, which was documented by Yarrell in his volume on<br />

British birds. Consequently, Temperley assumed that this added authenticity to the<br />

record. It was certainly a good time of the year for such a record of the species, but<br />

there is no known specimen <strong>from</strong> the incident. One was recorded as shot at<br />

Teesmouth on 30 August 1853. The third record, documented by Hancock (1874),<br />

was of one shot near Bishop Auckland,‟ a few years before 1873‟. Temperley<br />

expressed his concern about this specimen and where it was shot, but felt it was<br />

acceptable, but with some reservations.

Tit-<strong>bits</strong> <strong>from</strong> Temperley<br />

The <strong>Bird</strong>s of <strong>Durham</strong> Heritage Project<br />

‘Bringing the wildlife of the past, to the people of tomorrow’<br />

Ruff<br />

Temperley called it a “fairly regular autumn passage migrant, in small numbers”, “has<br />

been known to breed”. He gave no evidence to state that breeding was ever regular<br />

in the past. Sharp (1816), described it as a „very rare‟ bird in the Hartlepool area;<br />

Hogg (1827) said it was „extremely rare‟, though he noted its passage status at<br />

Teesmouth. By contrast, Edward Backhouse (1834) described it as „not uncommon‟<br />

at Teesmouth, rarely met with in breeding plumage. He did note that one was shot at<br />

Whitburn Moors, „a few years ago‟. Hutchinson (1840) noted it as occasionally found<br />

in small parties in September and October. Breeding occurred at Teesmouth<br />

„probably, 1901‟ and definitely in 1902 (two nests), in 1903 birds possibly bred, but<br />

there were no birds in 1904. Tristram (1905), had it on good authority that ruff<br />

formerly bred at Boldon Flats.<br />

Kentish Plover<br />

Temperley called it “a very rare vagrant”. Three records up to 1951, Temperley‟s<br />

time of publication. The first record of the species was of one at Teesmouth on 8<br />

June 1902, observed by J. Bishop, and C.E. Milburn. The second record was on 20<br />

May 1904, Bishop found one at Seaton Carew – an adult female was picked up dead<br />

near the North Gare breakwater at the end of May, and this was presumably, the<br />

same bird. The third record was on 11 th May 1924, when a pair was at Teesmouth,<br />

found by the same pair of observers who had found the first bird almost 22 years<br />

earlier.<br />

Dotterel<br />

Temperley said that it was “a passage migrant in very small numbers”. He said that it<br />

was mainly a spring migrant, annually recorded in the late 1940s and early 1950s at<br />

Teesmouth, though records elsewhere in County <strong>Durham</strong>, he called „exceptional‟.<br />

Three birds were noted at Darlington Sewage Farm on 3 September 1929 but it is<br />

very rare in the autumn in the County. Temperley commented that when the species<br />

nested more regularly in the north Pennines and the Lake District, then he felt it was<br />

then more commonly documented as occurring in <strong>Durham</strong>, particularly in the west of<br />

<strong>Durham</strong>. Hutchinson (1840) reported its passage in autumn as rapid, but more<br />

lingering in spring, with the greatest numbers in May. He said that it had not been<br />

recorded breeding in <strong>Durham</strong>, but he speculated on where successful breeding might<br />

occur, these included Burnhope, Killhope and Wellhope. Temperley observed that<br />

since 1840, the <strong>Durham</strong> Moors had been extensively searched „in vain‟ by<br />

ornithologists, including Temperley himself, but no Dotterel were found breeding, and<br />

passage birds were rare on moorlands by Temperley‟s time of writing.<br />

Stone Curlew<br />

Temperley documented that this “was a very rare vagrant”, his first record was one<br />

taken in the neighbourhood of Wycliffe-on-Tees in August 1782. The second record<br />

was of one killed at Saltholme Pool in 1843. The third was courtesy of Hancock<br />

(1874), who told of one shot in a grass field near Frenchman‟s Bay, South Shields,<br />

on 4 February 1864, the first winter record. Tristram stated that one was at<br />

Teesmouth on 11 November 1901.<br />

Little Bustard<br />

Temperley said one was shot at Harton, South Shields in December 1876, the<br />

specimen was sent to Hancock to „improve the stuffing‟ on 9 March 1877. A<br />

specimen was presented to the Natural History Society of Northumberland, <strong>Durham</strong><br />

and Newcastle upon Tyne in 1935; the details of this indicate that it had been shot at

Tit-<strong>bits</strong> <strong>from</strong> Temperley<br />

The <strong>Bird</strong>s of <strong>Durham</strong> Heritage Project<br />

‘Bringing the wildlife of the past, to the people of tomorrow’<br />

Marsden about 1860. Temperley thought it possible that this was the same bird seen<br />

by Hancock in 1877.<br />

Common Crane<br />

Temperley said that it was “a very rare vagrant, of which<br />

there is only one record for the County”. A specimen<br />

was shot on the Hart Estate, at Dyke House Farm in<br />

1865. Temperley said that at one time, there is little<br />

doubt that the Crane was a once regular winter visitor to<br />

<strong>Durham</strong>, a couple of centuries or so ago.<br />

White-winged Black Tern<br />

Temperley called it “a very rare vagrant”. There was one documented record, by<br />

Hancock (1874), an adult bird shot on 15 May sometime before 1871at Port<br />

Clarence, Teesmouth. Nelson (1907) said it was killed on 15 May 1869.<br />

Common Tern<br />

Temperley highlighted the Cott manuscript (1670), which recorded “a shelf of sand,<br />

raised above the highe water marke that entertaines an infinite number of sea-fowle,<br />

which lay their Egges here and there”.<br />

Herring Gull<br />

First known to breed in 1943 on Marsden Rock. <strong>Bird</strong>s were recorded breeding in<br />

1943 when the coast was closed off to the public, at least one nest, possibly more<br />

pairs, bred then. <strong>Bird</strong>s then bred annually after that on Marsden rock, <strong>from</strong> then until<br />

1951.<br />

Kittiwake<br />

Temperley said that it was, “a common summer resident and passage migrant”,<br />

“winter visitor in small numbers”. Hutchinson (1840) said that it didn‟t breed in<br />

<strong>Durham</strong>. In 1934 a small colony was established on the seaward side of the<br />

Marsden Rock, spreading to other ledges and faces as the colony grew in<br />

subsequent years. By 1937, there were an estimated 300 nests and by 1944, about<br />

1000 pairs were estimated to be present, with the mainland cliffs now occupied.<br />

Ivory Gull<br />

Temperley said it was a “very rare winter visitor”. There were four records of the<br />

species up to Temperley‟s time of publication, only of one of which was felt to be fully<br />

and completely authenticated. One, an immature was shot at Seaton Carew in<br />

March 1837. Hogg (1845), reported one found dead at Cowpen Marsh, the date<br />

unspecified; the specimen was considered too decayed for preservation. Another<br />

was shot off the mouth of the Tyne prior to 1874 (Hancock, 1874), but was thought<br />

by some e.g. George Bolam, to be „not above suspicion‟. One was reported by<br />

Lofthouse (1887), as being shot at Teesmouth on 14 February 1880.<br />

Great Auk<br />

An upper mandible of a specimen of Great Auk was discovered alongside other bird<br />

and mammal remains “in some old sea caves in the limestone cliffs at Whitburn<br />

Lizard”. In fact, these remains were found in a cave in a quarry on Cleadon Hills, not<br />

actually on the coast. Essentially the cave contained a midden of food remains<br />

(alongside human remains), including those of red deer, roe deer, badger, marten<br />

amongst others. This discovery was made in 1878.

Tit-<strong>bits</strong> <strong>from</strong> Temperley<br />

The <strong>Bird</strong>s of <strong>Durham</strong> Heritage Project<br />

‘Bringing the wildlife of the past, to the people of tomorrow’<br />

Corncrake<br />

In 1951, Temperley called it “a summer resident, once abundant, now scarce”. He<br />

said that „most had been lost „in recent years‟. Late in the 19 th century and early in<br />

the 20 th century, Temperley said that it was to be found breeding in “almost every<br />

meadow” of <strong>Durham</strong>, even on the outskirts of towns. However, numbers fluctuated<br />

<strong>from</strong> year to year. In 1861, Hogg noted a scarcity of these species around Norton<br />

over a 3-4 year period. Nationally, the major decline commenced earlier, further<br />

south, around 1907 this became marked and widespread. In <strong>Durham</strong>, decreases<br />

were noted <strong>from</strong> around 1915, continued through 1929 and <strong>from</strong> that time it was a<br />

scarce bird in <strong>Durham</strong>. Temperley, in 1951, said that it was quite usual to “live in the<br />

County and not to hear the call of the corn-crake once in a season”.<br />

Baillon’s Crake<br />

This species was called a “very rare vagrant of which only two records”. Hancock<br />

(1874), told of Thomas Thompson shooting one on the side of the Derwent on, or<br />

about, 12 July 1874; it was in breeding plumage and the specimen is in the Hancock.<br />

One in the Dorman Museum was shot at „Saltholme Marsh‟, in September 1882, it<br />

was shot by T.H. Nelson on 16 September 1882.<br />

Capercaillie<br />

Extinct but Temperley noted that, in 1878, numerous bones of this species were<br />

found in a limestone cave on the <strong>Durham</strong> side of the Tees in upper Teesdale, at<br />

about 1600 feet above sea level.<br />

Black Grouse<br />

Temperley said that it was “a resident; less common now than formerly”. He said, at<br />

1951, that it had a very local distribution, being found on the fringes of the western<br />

moorlands – where woodland, birch scrub provides cover.<br />

Red Grouse<br />

“Plentiful on the heather moors to the west of the county,<br />

where it is encouraged...by game preservers”. Only moves in<br />

exceptionally cold, snow-covered weather as on 24 November<br />

1884, when a heavy snowstorm was followed by a thaw and<br />

re-freeze, leading to a „glazing‟ of the moors. <strong>Bird</strong>s were<br />

consequently driven off the moors and twelve were seen at<br />

Ferryhill, and single birds seen as far east as Heworth and<br />

even Seaham (at the <strong>Durham</strong> coast).<br />

Serin<br />

“A very rare vagrant”, said Temperley and he documented the first county record, a<br />

bird found in a garden near Westoe, South Shields, by John Coulson on 12<br />

November 1950. It was seen again on 19 th and 26 th of the month and was an adult<br />

male.<br />

Aquatic Warbler<br />

On 28 August 1951, one was found by John Coulson, in Frenchman‟s Bay, South<br />

Shields. It was reported to Fred Grey, who saw it and concluded that it was an<br />

aquatic warbler. It was later also seen by Dr. H.M.S. Blair. This was the first record<br />

of the species for the northeast of England.<br />

Prepared by the Natural History Society of Northumbria and the <strong>Durham</strong> <strong>Bird</strong> <strong>Club</strong>, as a contribution to<br />

The <strong>Bird</strong>s of <strong>Durham</strong> Heritage Project, <strong>from</strong> A History of the <strong>Bird</strong>s of <strong>Durham</strong> by George W. Temperley,<br />

published in the Transactions of the Natural History Society of Northumberland, <strong>Durham</strong> and Newcastle<br />

upon Tyne Vol. IX