Biodiversity of the Rewa Head B Zoological Society of London ...

Biodiversity of the Rewa Head B Zoological Society of London ...

Biodiversity of the Rewa Head B Zoological Society of London ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>Zoological</strong> <strong>Society</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>London</strong>, Regents Park, <strong>London</strong> NW1 4RY<br />

www.zsl.org<br />

Registered Charity no. 208728<br />

<strong>Biodiversity</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rewa</strong> <strong>Head</strong> B

ZSL Conservation Report No.10<br />

A <strong>Biodiversity</strong> Assessment<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rewa</strong> <strong>Head</strong>, Guyana<br />

July 2009<br />

Rob Pickles<br />

Niall McCann<br />

Ashley Holland

Published by: The <strong>Zoological</strong> <strong>Society</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>London</strong>, Regents Park, <strong>London</strong>, NW1 4RY<br />

Copyright: © <strong>Zoological</strong> <strong>Society</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>London</strong> and contributors 2009.<br />

All rights reserved. The use and reproduction <strong>of</strong> any part <strong>of</strong> this<br />

publication is welcomed for non-commercial purposes only,<br />

provided that <strong>the</strong> source is acknowledged.<br />

ISSN: 1744-3997<br />

Citation: R. Pickles, N. McCann, A. Holland (2009)<br />

A <strong>Biodiversity</strong> Assessment <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rewa</strong> <strong>Head</strong>, Guyana.<br />

ZSL Conservation Report No. 10. The <strong>Zoological</strong> <strong>Society</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>London</strong>,<br />

<strong>London</strong>.<br />

Key Words: Guyana, <strong>Rewa</strong>, biodiversity, threatened species, conservation, giant<br />

otter, logging, mining, ecosystem services<br />

Front cover: Jaguar photographed in <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rewa</strong> <strong>Head</strong> © Gordon Duncan 2004<br />

Page layout: candice@chitolie.com<br />

The <strong>Zoological</strong> <strong>Society</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>London</strong> (ZSL), founded in 1826, is a world-renowned<br />

centre <strong>of</strong> excellence for conservation science and applied conservation (registered<br />

charity in England and Wales number 2087282). Our mission is to promote and<br />

achieve <strong>the</strong> worldwide conservation <strong>of</strong> animals and <strong>the</strong>ir habitats. This is realised<br />

by carrying out field conservation and research in over 80 countries across <strong>the</strong><br />

globe and through education and awareness at our two zoos, ZSL <strong>London</strong> Zoo and<br />

ZSL Whipsnade Zoo, inspiring people to take conservation action.<br />

The aim <strong>of</strong> this Conservation Report series is to inform people <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> work that<br />

ZSL and its partners do in field conservation. Results <strong>of</strong> work carried out in field projects<br />

are <strong>of</strong>ten only reported in unpublished technical reports. This series seeks to bring<br />

this grey literature into a more accessible form to help guide conservation<br />

management and inform policy. The main intention is to report on particular<br />

achievements, especially where lessons learnt form <strong>the</strong> field can benefit o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

conservation pr<strong>of</strong>essionals. The results <strong>of</strong> field surveys will also be disseminated<br />

through this series.<br />

The primary audience for <strong>the</strong>se reports is ZSL’s conservation partners. These<br />

include government departments, private sector actors and conservation<br />

organisations. In some cases this type <strong>of</strong> report will also be useful for local<br />

communities. This series will be published in English and o<strong>the</strong>r languages as<br />

appropriate. Because only a limited number <strong>of</strong> hard copies will be produced,<br />

electronic versions <strong>of</strong> all <strong>the</strong>se reports will be available through <strong>the</strong> ZSL library.<br />

(https://library.zsl.org)

A <strong>Biodiversity</strong> Assessment<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rewa</strong> <strong>Head</strong>, Guyana<br />

July 2009<br />

R.S.A. Pickles<br />

N.P. McCann<br />

A.P. Holland

Co n t e n t s<br />

Executive Summary 3<br />

Acknowledgements 4<br />

Team 5<br />

Introduction 6<br />

Background to <strong>the</strong> expedition 6<br />

The Guianan Shield 6<br />

Situation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rewa</strong> <strong>Head</strong> 7<br />

Human occupancy and visits above Corona Falls 8<br />

The Expedition 10<br />

Chapter 1. Mammal Species Diversity and Relative Abundance 11<br />

Flagship Species: The Giant Otter 11<br />

Camera Trapping Survey 13<br />

Observations 17<br />

Chapter 2. Bird Species Diversity and Relative Abundance 20<br />

Mist Netting Survey 20<br />

Drift Spot Count Survey 22<br />

Chapter 3. Reptile Species Diversity 24<br />

Chapter 4. The Future State <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rewa</strong> <strong>Head</strong>:<br />

Identification <strong>of</strong> Stakeholders 26<br />

Chapter 5. Conservation 31<br />

Conservation Recommendations 32<br />

References 34<br />

Appendix 1. Mammalian Diversity 37<br />

Appendix 2. Avian Diversity and Relative Abundance 39<br />

Appendix 3. Reptilian Diversity 47<br />

Appendix 4. EPA permission to conduct biodiversity research 48<br />

<strong>Biodiversity</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rewa</strong> <strong>Head</strong> 1

Figure 1. Jaguar (Pan<strong>the</strong>ra onca) Photograph taken by Gordan Duncan in 2004. During that six<br />

week trip <strong>the</strong> water level was exceptionally low and 10 jaguar were observed.<br />

Figure 2. Goliath bird-eating spider (Theraphosa blondii), one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> giants <strong>of</strong> Guyana’s interior.<br />

Gordon Duncan.<br />

2 <strong>Biodiversity</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rewa</strong> <strong>Head</strong>

ex e C u t i v e su m m a r y<br />

The reason for <strong>the</strong> expedition<br />

This report lays out <strong>the</strong> findings <strong>of</strong> a six week expedition above Corona Falls to<br />

<strong>the</strong> split between <strong>the</strong> East and West River <strong>Rewa</strong> in Guyana’s Upper Takutu-Upper<br />

Essequibo Region, documenting <strong>the</strong> fauna observed along 60 river miles. The <strong>Rewa</strong><br />

flows between <strong>the</strong> Conservation International Upper Essequibo Concession and<br />

<strong>the</strong> proposed Kanuku Mountains Protected Area, feeding <strong>the</strong> biologically important<br />

Rupununi Basin. Yet despite <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rewa</strong> <strong>Head</strong> appearing to be preserved in a pristine<br />

state it has not been explored scientifically to assess its conservation value. The<br />

initial focus <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> expedition was <strong>the</strong> endangered giant otter (Pteronura brasiliensis),<br />

but alongside <strong>the</strong> giant otter research we set up a line <strong>of</strong> camera traps and mist-net<br />

stations as well as conducting drift surveys to record <strong>the</strong> riparian and forest fauna.<br />

Major Findings<br />

A line <strong>of</strong> camera traps positioned in <strong>the</strong> 25 miles immediately above Corona Falls<br />

recorded a total <strong>of</strong> 17 mammal species, including puma (Puma concolor), margay<br />

(Leopardus wiediii), giant anteater (Myrmecophaga tridactyla) and Brazilian tapir<br />

(Tapirus terrestris). In total, 33 mammal species were recorded during <strong>the</strong> course<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> expedition including all 8 <strong>of</strong> Guyana’s monkey species. Mist netting and<br />

drift spot counts yielded a total <strong>of</strong> 187 bird species from 47 families. With <strong>the</strong><br />

inclusion <strong>of</strong> Smithsonian Institution data from 2006, <strong>the</strong> species list for <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rewa</strong><br />

<strong>Head</strong> rises to 251. These include 10 Guianan Shield endemics, two species <strong>of</strong> which<br />

had particularly small ranges: Todd’s antwren (Herpsilochmus stictocephalus) and<br />

<strong>the</strong> little hermit (Phaethornis longuemareus); as well as <strong>the</strong> rare and charismatic<br />

harpy eagle (Harpia harpyja) and crested eagle (Morphnus guianensis). We also saw<br />

evidence <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> threatened bush dog (Speothos venaticus), yellow-footed tortoise<br />

(Geochelone denticulata) and giant armadillo (Priodontes maximus). In total, 50%<br />

<strong>of</strong> Guyana’s threatened species were observed above or immediately below Corona<br />

Falls. Goliath bird-eating spider (Theraphosa blondii) was recorded in <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rewa</strong> <strong>Head</strong><br />

and <strong>of</strong> particular note, 5 green anacondas (Eunectes murinus) over 15ft long were<br />

encountered. One individual measured was found to be 18’2”. Wildlife, particularly<br />

game species, was found to be naïve, with tapir, paca and black curassow allowing<br />

us to approach within several metres without fleeing.<br />

Birds: 251 species<br />

Mammals: 33 species<br />

Threatened fauna: 14 species<br />

Conservation Recommendations<br />

The results <strong>of</strong> this brief survey reveal <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rewa</strong> <strong>Head</strong> to be biologically rich and an<br />

important region for threatened lowland rainforest and riparian fauna. It is also <strong>the</strong><br />

headwater <strong>of</strong> an important tributary feeding <strong>the</strong> Essequibo. The <strong>Rewa</strong> <strong>Head</strong> is currently<br />

under no protection and although <strong>the</strong> government has recently outlawed small-scale<br />

gold mining from <strong>the</strong> river, <strong>the</strong> area does constitute a logging concession which<br />

may well be developed in <strong>the</strong> coming years. Due to <strong>the</strong> ease with which charismatic<br />

rainforest fauna such as tapir, anaconda and harpy eagle can be seen; <strong>the</strong>re is <strong>the</strong><br />

potential for developing a modest, regulated tourist industry with <strong>the</strong> villages <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Rewa</strong> and Yupukari. The infrastructure already in place in <strong>the</strong>se villages could play an<br />

important role in establishing programmes <strong>of</strong> scientific investigation in <strong>the</strong> area for<br />

exploring <strong>the</strong> biodiversity <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Guianan Shield ecoregion as well as <strong>the</strong> distribution<br />

and biology <strong>of</strong> endangered species.<br />

<strong>Biodiversity</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rewa</strong> <strong>Head</strong> 3

aC k n o w l e d g e m e n t s<br />

Many thanks go to Diane McTurk for help and advice, allowing us to stay in Karanambu<br />

while analysing our data and collecting samples from her Rupununi otters. Thanks<br />

to Margaret Chan-a-sue for logistical support in Georgetown and to Peter Taylor<br />

for sound advice, tireless energy and for pointing us in <strong>the</strong> right direction. We are<br />

extremely grateful to Graham Watkins for criticism and advice and to Nicole Duplaix,<br />

for introducing us to <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rewa</strong> to begin with. This expedition was funded through<br />

generous grants from <strong>the</strong> Linnaean <strong>Society</strong>’s Percy Sladen Memorial Foundation, ZSL’s<br />

Daisy Balogh Travel Award and through NERC expedition funds. The majority <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

expedition costs were self-financed.<br />

4 <strong>Biodiversity</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rewa</strong> <strong>Head</strong>

te a m<br />

Rob Pickles. BSc Zoology<br />

Rob and Niall first worked toge<strong>the</strong>r on giant otters in a Royal Geographical <strong>Society</strong><br />

funded expedition to Bolivia in 2003. Following on from this in 2006 Rob began a<br />

PhD investigating <strong>the</strong> population genetics <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> giant otter at <strong>the</strong> Institute <strong>of</strong> Zoology,<br />

<strong>Zoological</strong> <strong>Society</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>London</strong> (ZSL) and <strong>the</strong> Durrell Institute <strong>of</strong> Conservation and<br />

Ecology (DICE) at <strong>the</strong> University <strong>of</strong> Kent. He is now in his third year <strong>of</strong> study.<br />

Niall McCann. BSc Zoology<br />

After finishing his degree in zoology at Bristol University, Niall worked as a research<br />

assistant on ZSL’s jackal project in Namibia and is about to embark on a PhD studying <strong>the</strong><br />

population connectivity <strong>of</strong> Baird’s tapir in Honduras based at <strong>the</strong> University <strong>of</strong> Cardiff.<br />

Ashley Holland<br />

Ash has worked with both <strong>the</strong> Smithsonian Institute and <strong>the</strong> BBC and was <strong>the</strong> local expert<br />

and naturalist as well as providing <strong>the</strong> logistical support to get up to <strong>the</strong> survey area.<br />

He has explored <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rewa</strong> <strong>Head</strong> on several occasions and worked with Conservation<br />

International during <strong>the</strong>ir Rapid Assessment Programme to <strong>the</strong> Eastern Kanukus after<br />

working at Karanambu Ranch for many years and is currently <strong>the</strong> manager <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> black<br />

caiman research project in Yupukari.<br />

Kevin Alvin<br />

Kevin is a resident <strong>of</strong> Katoka village and knows <strong>the</strong> river well, working with <strong>the</strong><br />

Smithsonian Institution mist netting and with <strong>the</strong> BBC in <strong>the</strong> filming <strong>of</strong> ‘Lost land <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Jaguar’ and ‘Planet Earth’ series. He has worked with Ash for over five years.<br />

Ryol Merriman<br />

Ryol is a resident <strong>of</strong> Yupukari and has been working with Ash for over 10 years and has<br />

visited <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rewa</strong> <strong>Head</strong> on several occasions, working with <strong>the</strong> Smithsonian and BBC.<br />

Fernando Li<br />

Nando is <strong>the</strong> manager <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> black caiman project at Yupukari, funded by <strong>the</strong> Rupununi<br />

Learners Foundation. It is a long-term ecological study looking at <strong>the</strong> ecological role<br />

<strong>the</strong> species plays as well as sustainable resource use by local villages.<br />

Doris Merriman<br />

Doris was <strong>the</strong> expedition cook<br />

Figure 3. Ryol and Doris Merriman and bowman ‘Nando Li.<br />

<strong>Biodiversity</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rewa</strong> <strong>Head</strong> 5

in t r o d u C t i o n<br />

Background to <strong>the</strong> expedition<br />

The expedition was initially conceived as a sampling trip to collect faecal samples from<br />

<strong>the</strong> giant otter (Pteronura brasiliensis) to obtain DNA for use in a phylogeographical<br />

study being carried out by Rob Pickles at <strong>the</strong> <strong>Zoological</strong> <strong>Society</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>London</strong> and <strong>the</strong><br />

University <strong>of</strong> Kent. The <strong>Rewa</strong> <strong>Head</strong> was purported to have evaded <strong>the</strong> depredations <strong>of</strong><br />

hunters during <strong>the</strong> trade in giant otter fur and due to its isolated nature has witnessed<br />

little human impact over <strong>the</strong> centuries. It was recommended by Nicole Duplaix who<br />

conducted <strong>the</strong> first study on giant otters in <strong>the</strong> 1970s in Suriname. Due to <strong>the</strong> unexplored<br />

and unprotected status <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rewa</strong> <strong>Head</strong>, it was decided to maximize <strong>the</strong> time spent<br />

above Corona Falls by conducting coincidental biodiversity studies, namely camera<br />

trapping, mist-netting and spot-count transects.<br />

The Guianan Shield<br />

Figure 4. The Guianan Shield straddles five countries in nor<strong>the</strong>rn South America and its streams feed<br />

three drainage basins. High degrees <strong>of</strong> endemism and species diversity coupled with <strong>the</strong> largest tract<br />

<strong>of</strong> unbroken tropical forest anywhere in <strong>the</strong> world makes this an extremely important eco-region.<br />

Guyana is located in <strong>the</strong> nor<strong>the</strong>rn part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Guianan Shield, a vast Precambrian craton<br />

uplifted during <strong>the</strong> formation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Andes in <strong>the</strong> Oligocene, 3.5 million years ago. The<br />

craton formation has determined <strong>the</strong> hydrology <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> region, resulting in a watershed<br />

across its back which splits <strong>the</strong> flow <strong>of</strong> streams north-south. Across this 250 million<br />

hectares <strong>of</strong> nor<strong>the</strong>rn South America lies <strong>the</strong> largest tract <strong>of</strong> pristine forest anywhere in<br />

<strong>the</strong> tropics. The Guianan Shield contains some <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> most carbon-rich forests in South<br />

America and represents an important carbon dioxide sink in <strong>the</strong> fight against climate<br />

change (Saatchi et al 2007). Added to this, <strong>the</strong> Shield possesses extremely high levels<br />

<strong>of</strong> biodiversity and endemism as a result <strong>of</strong> Pleistocene refugia. Over 20,000 species <strong>of</strong><br />

vascular plants are found in <strong>the</strong> Guiana Shield, 35% <strong>of</strong> which are endemic. Similarly 975<br />

bird species are found in this eco region, <strong>of</strong> which 15% are endemic (Ellenbroek 1996).<br />

Lying between 1 and 9 degrees north <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Equator with a coast in <strong>the</strong> Carribean,<br />

Guyana receives most <strong>of</strong> its wea<strong>the</strong>r patterns from <strong>the</strong> Caribbean Intertropical<br />

Convergence Zone (ICZ) with a seasonality driven by a rainy season arriving in early<br />

May lasting until mid-August, followed by ano<strong>the</strong>r short rainy season in December. Its<br />

forests are hot and humid with between 2000-4000mm <strong>of</strong> rain annually.<br />

6 <strong>Biodiversity</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rewa</strong> <strong>Head</strong>

Unlike its larger neighbour to <strong>the</strong> south, Guyana has never had government-led drives to open<br />

up <strong>the</strong> interior <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> country and so <strong>the</strong> forests have remained largely intact. While at 215,000<br />

km 2 it is similar in land mass to Great Britain, its population is only 870,000 strong with a<br />

population density <strong>of</strong> 3.5 per km 2 , 90% <strong>of</strong> whom live in a strip <strong>of</strong> land around <strong>the</strong> industrialised<br />

nor<strong>the</strong>rn cities <strong>of</strong> Georgetown, Bartica and Linden. Land cover remains 76% rainforest and<br />

while some cattle ranching occurs in <strong>the</strong> natural Rupununi savannahs and small-scale gardens<br />

are cultivated by Amerindian communities, <strong>the</strong>re is very little agriculture in <strong>the</strong> interior.<br />

Situation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rewa</strong> <strong>Head</strong><br />

Figure 5. Location <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rewa</strong> <strong>Head</strong> and extent surveyed by this expedition.<br />

<strong>Biodiversity</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rewa</strong> <strong>Head</strong> 7

The <strong>Rewa</strong> <strong>Head</strong> is located in Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Guyana, in Upper Takutu-Upper Essequibo<br />

Administrative Region. It takes its water from tributaries feeding from <strong>the</strong> Kanuku<br />

Mountains in <strong>the</strong> South and drains north into <strong>the</strong> Rupununi and Essequibo before<br />

flowing into <strong>the</strong> Atlantic. The <strong>Rewa</strong> is termed a ‘blackwater river’ due to <strong>the</strong> humic, yet<br />

relatively sediment-free waters. Following <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rewa</strong> upstream from where it is met by<br />

<strong>the</strong> Kwitaro, <strong>the</strong> lowland rainforest vegetation type continues up above Corona Falls.<br />

Above here <strong>the</strong> river is fractured by a series <strong>of</strong> cataracts and falls which prevent <strong>the</strong><br />

colonisation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> headwaters by fish common in <strong>the</strong> Lower <strong>Rewa</strong>, such as arapaima<br />

(Arapaima gigas), lukanani (Cichla ocellaris) and arawana (Osteoglossum bicirrhosum).<br />

Likewise <strong>the</strong> black caiman (Melanosuchus niger), spectacled caiman (Caiman yacare)<br />

and giant Amazonian river turtle (Podocnemis expansa) are not found above Corona<br />

Falls. Above <strong>the</strong> falls <strong>the</strong> only fish species <strong>of</strong> human value are haimara (Hoplias aimara)<br />

and black piranhas (Serrasalmus rhombeus). A series <strong>of</strong> narrow tributaries flow into<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>Rewa</strong> along its meandering path above <strong>the</strong> falls. Some, such as Louis Creek and<br />

Kubrar Creek, can be followed for 6 miles or so, before fallen trunks block passage.<br />

Some <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> names <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> creeks, camps and falls used here are old and date back to<br />

<strong>the</strong> balatta bleeders, though most are names given by Ashley Holland and his guides<br />

from previous trips. Continuing upstream, <strong>the</strong> river narrows to 20ft wide by N2° 45.358’<br />

W58° 37.415’ and shortly after, at N2° 45’ W58° 33’ <strong>the</strong> vegetation becomes scrubby<br />

riparian bush with dense bamboo groves, cecropia and guava, continuing with patchy<br />

forest to N2° 42’ where dense forest once again predominates.<br />

Human occupancy and visits above Corona Falls<br />

The <strong>Rewa</strong> has historically been inhabited by Amerindians. Evidence can be seen in<br />

<strong>the</strong> petroglyphs found on <strong>the</strong> falls, predominantly Corona, where geometric designs<br />

along with grooves purported to be for sharpening hand-axes can still be seen. Those<br />

responsible for <strong>the</strong> artwork have long since disappeared, leaving <strong>the</strong> forests above <strong>the</strong><br />

falls empty <strong>of</strong> people.<br />

Figure 6. Hand-axe sharpening grooves and geometric designs below Corona Falls on <strong>the</strong> River<br />

<strong>Rewa</strong> testify to <strong>the</strong> fact that <strong>the</strong>re were once indigenous people inhabiting this area.<br />

8 <strong>Biodiversity</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rewa</strong> <strong>Head</strong>

The first outsiders to begin exploitation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> region were <strong>the</strong> balata bleeders in <strong>the</strong><br />

early 20 th Century, who even ventured up as far as <strong>the</strong> East-West Split in order to tap<br />

<strong>the</strong> low-grade latex from <strong>the</strong> trees. The bleeders cut paths through <strong>the</strong> forest which<br />

are still recorded in <strong>the</strong> 1970 aerial survey. The petrochemical industry spelled <strong>the</strong> end<br />

for <strong>the</strong> balata industry and <strong>the</strong> last few bleeders likely ventured above Corona Falls in<br />

<strong>the</strong> 1960s. The gold found in <strong>the</strong> alluvial sand <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rewa</strong> <strong>Head</strong> has been a lure in <strong>the</strong><br />

past and several small mining operations worked <strong>the</strong> river above <strong>the</strong> falls in <strong>the</strong> early<br />

1990’s. Low gold prices coupled with <strong>the</strong> expense and extreme logistical difficulty<br />

<strong>of</strong> portaging dredging equipment over <strong>the</strong> falls led to <strong>the</strong> eventual abandonment <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong>se claims after a few years. The rotting equipment used during <strong>the</strong> dredging can<br />

still be found in <strong>the</strong> forest.<br />

Figure 7. Old compressor used by dredgers to compress air for <strong>the</strong> divers to brea<strong>the</strong>. Abandoned<br />

and now rotting in <strong>the</strong> forest.<br />

Since <strong>the</strong> last venture <strong>the</strong>re have not yet been any fur<strong>the</strong>r dredging operations anywhere<br />

along <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rewa</strong> and <strong>the</strong> forests have never been explored for commercial timber.<br />

Macushi Amerindians from <strong>Rewa</strong> Village hold garden plots in <strong>the</strong> fertile alluvial soil<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Lower <strong>Rewa</strong> and Wapishanan Amerindians from Shea in <strong>the</strong> shouth savannahs<br />

travel to <strong>the</strong> Kwitaro to farm by <strong>the</strong> river <strong>the</strong>re. The river and <strong>the</strong> forests here are<br />

extremely important to <strong>the</strong> Amerindians and people travel as much as 75 miles from<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir village to work a plot <strong>of</strong> land or fish and collect turle eggs at certain times <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

year. However <strong>the</strong> villagers do not travel above Corona Falls and consequently, since<br />

<strong>the</strong> decline <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> balata industry and <strong>the</strong> dredgers above <strong>the</strong> falls, <strong>the</strong> wildlife has<br />

ceased to be exposed to hunting pressure and is allowed to flourish.<br />

Our expedition in January 2009 followed on from a Conservation International (CI)<br />

Rapid Assessment Programme in <strong>the</strong> Eastern Kanuku Mountains and Lower Kwitaro<br />

River in 2001 and a Smithsonian Institution bird specimen collecting expedition to<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>Rewa</strong>, collecting from two sites, one below Corona Falls in <strong>the</strong> Lower <strong>Rewa</strong> and<br />

<strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r above <strong>the</strong> falls. In 2007 <strong>the</strong> BBC carried out an expedition to <strong>the</strong> Upper<br />

Essequibo and spent several days above Corona Falls. filming wildlife. Ashley Holland<br />

has explored <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rewa</strong> <strong>Head</strong> several times with Gordan Duncan. Duane de Freitas has<br />

also led several trips above <strong>the</strong> falls for birdwatchers and tourists.<br />

<strong>Biodiversity</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rewa</strong> <strong>Head</strong> 9

th e ex p e d i t i o n<br />

The expedition ran from <strong>the</strong> 31 st December 2008 to <strong>the</strong> 31 st January 2009. Niall and<br />

Rob met with Ash and <strong>the</strong> rest <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> team at Annai on <strong>the</strong> 31 st and proceeded up <strong>the</strong><br />

Rupununi before heading up <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rewa</strong>. The next few days were spent motoring up to<br />

Corona Falls, <strong>the</strong> juncture between <strong>the</strong> Lower <strong>Rewa</strong> and <strong>Rewa</strong> <strong>Head</strong>, arriving <strong>the</strong>re on<br />

<strong>the</strong> 3 rd January. The next three days were spent portaging over <strong>the</strong> string <strong>of</strong> falls and<br />

cataracts, before motoring on up to <strong>the</strong> split between East and West <strong>Rewa</strong>, setting<br />

up <strong>the</strong> camera trap grid as we went. In this way we worked our way up as far up <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Rewa</strong> as was navigationally feasible, before slowly working our way back down <strong>the</strong><br />

river, surveying as we went. We took two 7m heavy duty aluminium boats with 15hp<br />

outboard engines owned by Ashley Holland and carried 150 gallons <strong>of</strong> fuel for <strong>the</strong> trip,<br />

leaving caches above and below Corona Falls for <strong>the</strong> return journey. We carried three<br />

GPS units: two Garmin E-Trex and a Garmin GPSmap 60Cx for work under <strong>the</strong> canopy.<br />

General positioning was conducted using Guyana Survey maps printed at <strong>the</strong> Survey<br />

Department <strong>of</strong> Guyana, Georgetown.<br />

Figure 8. Portaging <strong>the</strong> boats over a cataract upstream <strong>of</strong> Bamboo Falls.<br />

First base was at <strong>the</strong> East-West Split at N2° 37.752’ W58° 37.152’, from which we<br />

explored <strong>the</strong> West branch <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rewa</strong> up to 2°37’ before a series <strong>of</strong> fallen trees blocked<br />

passage. Three days were spent at “Split Camp” from <strong>the</strong> 10 th to <strong>the</strong> 13 th January. From<br />

<strong>the</strong>re we travelled downstream to “Tayra Camp” at N2° 45.358’ W58° 37.415’, erecting<br />

<strong>the</strong> second netting site, conducting drift transects and searching for sign <strong>of</strong> giant otter<br />

until <strong>the</strong> 16 th . The following camp was at N2° 53.697’ W58° 35.225’, known as “Onca<br />

Camp”. We remained here until <strong>the</strong> 19 th , surveying and netting before moving fur<strong>the</strong>r<br />

downstream to “Monkey Ladder Camp” at N2° 59.773’ W58° 35.971’. While here we<br />

explored Louis Creek up to N2° 58.381’ W58° 32.799’. We were severely hampered<br />

by inclement wea<strong>the</strong>r, experiencing two torrential downpours which lasted for 36hrs<br />

and resulted in <strong>the</strong> river level rising by 10ft. The final camp above Corona Falls was at<br />

“Powis Camp”, below Powis Falls at N3° 07.901’ W58° 37.896’. We remained at Powis<br />

until <strong>the</strong> 27 th January surveying and netting, before collecting up <strong>the</strong> string <strong>of</strong> camera<br />

traps and portaging our gear back over Bamboo and Corona Falls. The night <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

27 th we stayed at a campsite below Corona Falls, before departing <strong>the</strong> following day,<br />

motoring <strong>the</strong> next three days back down <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rewa</strong> and Rupununi, reaching Karanambu<br />

on <strong>the</strong> 31 st <strong>of</strong> January. In total we spent 22 days above Corona Falls. This report is a<br />

presentation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> wildlife encountered during that time.<br />

10 <strong>Biodiversity</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rewa</strong> <strong>Head</strong>

Chapter 1. Mammalian Species Diversity and Relative Abundance<br />

The study <strong>of</strong> mammalian diversity and relative abundance was principally based on a<br />

line <strong>of</strong> camera traps erected in <strong>the</strong> 25 miles <strong>of</strong> river immediately upstream <strong>of</strong> Corona<br />

Falls. The species list presented in <strong>the</strong> appendix is a combination <strong>of</strong> observations<br />

recorded through camera trapping, sightings made while on drift transects and<br />

opportunistically as well as indirect evidence such as scats, footprints and burrows.<br />

Our reference was Emmons and Feer (1997) Neotropical Rainforest Mammals however<br />

we have used <strong>the</strong> most recent taxonomic revisions including <strong>the</strong> Guianan red howler<br />

monkey, (Alouatta macconnelli) and red-backed bearded saki (Chiropotes chiropotes).<br />

Principal Findings<br />

• 33 species <strong>of</strong> mammal recorded including all 8 <strong>of</strong> Guyana’s primates and 5<br />

species <strong>of</strong> felid.<br />

• Healthy population <strong>of</strong> endangered giant otter ( Pteronura brasiliensis) with 5<br />

groups recorded above <strong>the</strong> falls, equating to one group every 12 miles. Four<br />

groups were recorded below <strong>the</strong> falls.<br />

• 17 species <strong>of</strong> medium to large mammal recorded in camera traps including<br />

puma (Puma concolor), giant anteater (Myrmecophaga tridactyla) and margay<br />

(Leopardus wiedii).<br />

• Indirect evidence for <strong>the</strong> presence <strong>of</strong> bush dog ( Speothos venaticus) and giant<br />

armadillo (Priodontes maximus).<br />

• High abundance <strong>of</strong> Brazilian tapir ( Tapirus terrestris) with 5 encountered on<br />

<strong>the</strong> river and approximately 2.5 tapir roads crossing <strong>the</strong> river every mile. The<br />

animals encountered appeared naïve, due to <strong>the</strong> absence <strong>of</strong> hunting.<br />

Flagship species: The Giant Otter<br />

The highly charismatic giant otter (Pteronura brasiliensis) was <strong>the</strong> main focus <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

expedition, as we were <strong>the</strong>re to collect faecal samples for genetic analysis. The giant<br />

otter population is in <strong>the</strong> process <strong>of</strong> recovering from a hunting-mediated population<br />

crash in <strong>the</strong> last century which drove <strong>the</strong> species down to an estimated 3000 individuals<br />

range-wide (Carter & Rosas 1997). While no <strong>of</strong>ficial estimate <strong>of</strong> pre-hunting population<br />

size exists, judging by skin export figures (Carlos et al 1985, Schenck 1996), it could<br />

easily have been as high as 50,000. Since placing <strong>the</strong> giant otter in CITES Appendix<br />

1, <strong>the</strong> removal <strong>of</strong> an international market in giant otter skins has seen numbers rise.<br />

However, it remains under threat particularly through habitat degradation, mercury<br />

poisoning, and direct conflict with fishermen (Harris et al 2005, Groenendijk et al 2005).<br />

Throughout <strong>the</strong> population crash <strong>the</strong> Guianan Shield remained a stronghold for <strong>the</strong><br />

species, a low human population density coupled with an interior which had yet to be<br />

opened up led to <strong>the</strong> giant otter surviving in this region while in o<strong>the</strong>r parts <strong>of</strong> South<br />

America it suffered local extirpation.<br />

The work <strong>of</strong> Diane McTurk and Karanambu Ranch fomented <strong>the</strong> impression <strong>of</strong><br />

this charismatic predator in <strong>the</strong> public’s eye, creating an irrevocable association<br />

between Guyana and <strong>the</strong> giant otter that has since been streng<strong>the</strong>ned by recent BBC<br />

documentaries in <strong>the</strong> region. Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Guyana remains one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> top sites in South<br />

America to see giant otters and as such <strong>the</strong> species acts as a huge draw to many <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> eco-tourists that venture to <strong>the</strong> Rupununi ensuring that <strong>the</strong>re is also an economical<br />

interest in <strong>the</strong> survival <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> species.<br />

Rob Pickles’ PhD is an investigation into <strong>the</strong> phylogeography <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> giant otter,<br />

using mitochondrial DNA to analyse patterns <strong>of</strong> relatedness between populations<br />

determining whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong>re has been any divergence according to drainage basin,<br />

or whe<strong>the</strong>r palaeoclimatic events may have been responsible. It also investigates<br />

<strong>the</strong> degree <strong>of</strong> gene flow between populations which has important implications for<br />

effective management <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> species.<br />

<strong>Biodiversity</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rewa</strong> <strong>Head</strong> 11

Figure 9a. Territorial display by a group <strong>of</strong> giant otters above Corona Falls. Termed ‘periscoping’<br />

<strong>the</strong> behaviour is accompanied by a cacophony <strong>of</strong> wails and snorts <strong>of</strong>ten backed up by a mock<br />

charge. For <strong>the</strong> biologist, periscoping allows pictures to be taken <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> unique throat patterns<br />

allowing identification <strong>of</strong> individuals.<br />

Figure 9b. Inquisitive adult male giant otter approaching <strong>the</strong> boat. While some individuals are<br />

remarkably fearless and will approach to within several yards <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> boat, <strong>the</strong> mood <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> group<br />

is determined by <strong>the</strong> breeding female. If she feels threatened <strong>the</strong> group will normally periscope<br />

and disappear.<br />

12 <strong>Biodiversity</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rewa</strong> <strong>Head</strong>

Method<br />

In surveying <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rewa</strong> for signs <strong>of</strong> giant otters we followed <strong>the</strong> guidelines <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

IUCN/SSC Otter Specialist Group (Groenendijk et al 2005). The river was searched for<br />

sign during drifts downstream, looking out for evidence <strong>of</strong> holts, latrines or scratch<br />

walls or for <strong>the</strong> groups <strong>the</strong>mselves. The position <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se was recorded using GPS<br />

to delineate group territories. Group sizes were obtained by directly counting all<br />

individuals when a group was encountered in <strong>the</strong> river. We used two Canon EOS<br />

400D cameras with 300mm and 500mm lenses to capture throat markings and a Sony<br />

Handycam mini DV. Giant otters have a unique throat pattern which can be used to<br />

identify individuals, preventing <strong>the</strong> same group being counted twice. When an active<br />

site was located, any faecal deposits evident were collected and stored in ethanol for<br />

subsequent genetic analysis.<br />

Results<br />

In <strong>the</strong> 65 miles <strong>of</strong> <strong>Rewa</strong> <strong>Head</strong> explored above Corona Falls, we found evidence <strong>of</strong><br />

5 groups with an estimated population size <strong>of</strong> 35 animals and collected 17 faecal<br />

samples. Due to <strong>the</strong> unseasonably heavy rains experienced it proved more difficult<br />

than anticipated to locate and observe groups. The narrow streams feeding <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rewa</strong><br />

were full, resulting in groups spending much <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir time hunting in <strong>the</strong>se difficult<br />

to access creeks. We found that groups frequently had latrines at <strong>the</strong> confluence <strong>of</strong><br />

a forest stream and <strong>the</strong> main river. Although we did not survey <strong>the</strong> Lower <strong>Rewa</strong> for<br />

giant otters, we did encounter 4 groups and collected 13 faecal samples from <strong>the</strong>m.<br />

We also observed <strong>the</strong> neotropical otter (Lontra longicaudis) in <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rewa</strong> <strong>Head</strong> on four<br />

occasions and encountered two sprainting sites.<br />

While <strong>the</strong>re currently appears to be no direct threat to <strong>the</strong> giant otter’s survival in <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Rewa</strong> and <strong>the</strong> population appears healthy, in informal discussions with fishermen it is<br />

apparent that <strong>the</strong>y view <strong>the</strong> giant otter as a competitor. Work in Bolivia, by Beccera-<br />

Cardona (2006) has shown that in rivers <strong>the</strong>re, <strong>the</strong>re is only a small overlap in fish<br />

species and size selection by fishermen and giant otters, however <strong>the</strong> more generalist<br />

nature <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Guyanese fishermen would inevitably lead to a degree <strong>of</strong> competition.<br />

This competition is generally tolerated, with actual killing <strong>of</strong> otters by villagers being<br />

rare. However food shortages in unproductive years might exacerbate antagonistic<br />

feeling towards giant otters leading to conflict.<br />

In <strong>the</strong> Lower <strong>Rewa</strong> evidence that <strong>the</strong> river might be mined for gold or diamonds was<br />

recorded. We found claims staked in April 2008 spread over 20 river miles. As this<br />

report was being prepared <strong>the</strong> Guyanese Government revoked all claims in <strong>the</strong> Lower<br />

<strong>Rewa</strong> and has put a moratorium on mining throughout both <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rewa</strong> <strong>Head</strong> and Lower<br />

<strong>Rewa</strong>. The giant otter is a top predator in its food chain and is thus extremely sensitive<br />

to mercury bioaccumulation. Mercury concentration has been shown to cause a range<br />

<strong>of</strong> neurological disorders, impaired reproduction and immunocompetency (Klenavic et<br />

al 2008, Fonseca et al 2005).<br />

Camera Trapping Survey<br />

In this study we used <strong>the</strong> Reconyx RC55 camera trap due to its fast ‘wake-up’ time and<br />

rate <strong>of</strong> image capture, able to record 1 frame per second. This enables a more accurate<br />

estimate to be made <strong>of</strong> animals travelling in groups. The use <strong>of</strong> digital technology<br />

proved essential in <strong>the</strong> high humidity <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> forest and despite torrential rains, no<br />

camera was lost to mould. 2GB Extreme III CF cards were used and proved ample<br />

to contain all images captured. The traps were triggered by a PIR motion sensor and<br />

were mounted with an infrared LED illuminator. Camera setup was as follows. Image<br />

quality: medium; Firing delay: no delay; Firing sensitivity: extremely high.<br />

<strong>Biodiversity</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rewa</strong> <strong>Head</strong> 13

Figure 10. Rapidity with which all 17 species <strong>of</strong> mammal<br />

recorded in <strong>the</strong> camera traps were captured.<br />

14 <strong>Biodiversity</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rewa</strong> <strong>Head</strong><br />

Method<br />

Twelve Reconyx RC55 camera<br />

traps were set up along <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Rewa</strong> above Corona Falls. Each<br />

trap was fixed to a tree or stake<br />

approximately 50cm above <strong>the</strong><br />

ground. The traps were set up in<br />

pairs, with one on <strong>the</strong> river bank<br />

itself facing inland and its partner<br />

150 metres perpendicular to <strong>the</strong><br />

river bank facing a direction<br />

estimated to best increase <strong>the</strong><br />

likelihood <strong>of</strong> capture. Each camera<br />

was considered a separate<br />

sampling site for determining <strong>the</strong><br />

Relative Abundance Index (RAI).<br />

The pairs were arranged 5 miles<br />

apart and left for a maximum <strong>of</strong><br />

22 days before collection. While<br />

game trails were not sought for<br />

in <strong>the</strong> placement <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> traps, local judgment was employed in <strong>the</strong>ir positioning<br />

in order to prevent focusing on dead ground. Due to <strong>the</strong> strict adherence <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

5mile/150m rule, we ensured that to some extent <strong>the</strong> placement <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> traps was<br />

randomised and took in a variety <strong>of</strong> micro-habitats from dense scrubby marshland<br />

to hill tops to open riparian bush.<br />

Figure 11. Layout <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> string <strong>of</strong> camera traps along <strong>the</strong> river.<br />

Results<br />

In total, 5227 camera trap hours were accumulated resulting in 214 triggering events.<br />

Of <strong>the</strong>se, discounting false triggerings due to movement <strong>of</strong> leaves by wind or in cases<br />

where animals had passed too rapidly to be captured, 167 individual animals could<br />

be identified from 16 species <strong>of</strong> mammal, 5 species <strong>of</strong> bird: Black curassow (Crax<br />

alector), grey-winged trumpeter, (Psophia crepitans), grey-fronted dove, (Leptotila<br />

rufaxilla), great tinamou (Tinamus major) and cinereous tinamou (Crypturellus<br />

cinereus); and one species <strong>of</strong> reptile: <strong>the</strong> jungle runner (Ameiva ameiva). From <strong>the</strong><br />

raw images <strong>of</strong> animals in which individual identification or sexing was impossible,<br />

we filtered <strong>the</strong> data based on <strong>the</strong> assumption that multiple firing episodes taken<br />

at <strong>the</strong> same site in <strong>the</strong> same 24 hour period constituted <strong>the</strong> same animal or group.<br />

Number <strong>of</strong> individuals was <strong>the</strong>n estimated from this as 157. Number <strong>of</strong> estimated<br />

individuals for each species was <strong>the</strong>n divided by this total to obtain <strong>the</strong> Relative<br />

Abundance Index (RAI).

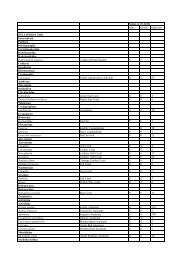

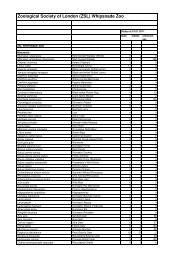

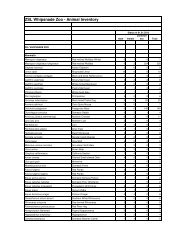

Table 1. Species diversity and relative abundance index <strong>of</strong> mammals recorded in <strong>the</strong> camera traps.<br />

Common Name Latin Name<br />

Number<br />

<strong>of</strong> firings<br />

Estimated<br />

number <strong>of</strong><br />

individuals<br />

Relative<br />

Abundance<br />

(%)<br />

Red-rumped Agouti Dasyprocta cristata 42 28 25.2<br />

Paca Agouti paca 18 17 15.3<br />

Green Acouchy Myoprocta exilis 27 15 13.5<br />

Collared Peccary Tayassu tajacu 2 9 8.1<br />

Brazilian Tapir Tapirus terrestris 9 9 8.1<br />

Nine-banded Long-nosed<br />

Armadillo<br />

Dasypus novemcinctus 9 9 8.1<br />

Red Brocket Deer Mazama americana 4 4 3.6<br />

Ocelot Leopardus pardalis 4 4 3.6<br />

Common Grey Four-eyed<br />

Oppossom<br />

Philander opossum 3 3 2.7<br />

Common Oppossom Didelphis marsupialis 2 2 1.8<br />

Jaguarundi Puma yagouaroundi 2 2 1.8<br />

Margay Leopardus wiedi 2 2 1.8<br />

Puma Puma concolor 2 2 1.8<br />

Spiny Rat sp Proechimys sp 2 2 1.8<br />

Guianan Squirrel Sciurus aestuans 1 1 0.9<br />

Giant Anteater Myrmecophaga tridactyla 1 1 0.9<br />

Tayra Eira barbara 1 1 0.9<br />

17 131 111 100<br />

Discussion<br />

The frequency <strong>of</strong> triggerings were not evenly distributed throughout <strong>the</strong> line <strong>of</strong> traps, but it<br />

appeared that several traps were set up in areas that were ‘dead ground’ with <strong>the</strong> worst site<br />

(3.1) only firing three times, with only one triggering event yielding species identification<br />

shots, while o<strong>the</strong>rs were in ‘hot spots’. Traps 4.2 and 6.1 proved <strong>the</strong> most successful, both<br />

recording 11 species from 30 and 39 triggering events respectively. Trap 4.2 was actually<br />

set up on a hill, 150m from <strong>the</strong> river’s edge and proved to be an extremely successful spot.<br />

All traps except one continued to work well despite <strong>the</strong> torrential downpours and high<br />

humidity experienced during <strong>the</strong> expedition, battery power was between 60-80% when<br />

<strong>the</strong> traps were recovered after 22 days and <strong>the</strong> 2GB CF cards were between 1-40% full. To<br />

a certain extent, <strong>the</strong> lack <strong>of</strong> triggerings made in <strong>the</strong> poorer sites might reflect inaccurate<br />

set up. Judging <strong>the</strong> exact angle at which to point <strong>the</strong> trap in order to both capture small<br />

rodents passing in <strong>the</strong> foreground and anything passing in <strong>the</strong> background was not always<br />

successful. We recommend using a laser pen for setting up as this can help to achieve <strong>the</strong><br />

perfect angle. While <strong>the</strong> company Moultrie have a camera trap on <strong>the</strong> market with this<br />

function built in, <strong>the</strong> lack <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ability to have constant firing function, coupled with a<br />

slower wake-up time meant we rejected that model for this study.<br />

There appeared to be no difference in species capture success depending on <strong>the</strong><br />

placement <strong>of</strong> camera traps whe<strong>the</strong>r at <strong>the</strong> river’s edge, or set 150m inland. The bank<br />

traps captured a total <strong>of</strong> 17 species in 79 triggerings, whereas <strong>the</strong> inland traps captured<br />

19 species in 91 triggerings. Four species were exclusively caught in <strong>the</strong> river edge<br />

traps (Guianan squirrel (Sciurus aestuans), ocelot (Leoprardus pardalis), puma (Puma<br />

concolor), and jungle runner (Ameiva ameiva) whereas 6 were caught only by <strong>the</strong><br />

inland traps (red brocket deer (Mazama americana), giant anteater (Myrmecophaga<br />

tridactyla), tayra (Eira barbara), margay (Leopardus weidii), common opossum<br />

(Didelphis marsupialis) and grey-winged trumpeter (Psophia crepitans)).<br />

One reason for setting up <strong>the</strong> traps in a paired string was to test <strong>the</strong> hypo<strong>the</strong>sis that<br />

felids follow watercourses and so will be more likely to be captured near to <strong>the</strong> river<br />

bank. While our data are not numerous enough to make meaningful statements, out <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> 10 cats photographed, 7 <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>m were captured by <strong>the</strong> river’s edge traps.<br />

<strong>Biodiversity</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rewa</strong> <strong>Head</strong> 15

Figure 12. Male puma (Puma concolor) filmed captured<br />

following a female (tail just visible on far right).<br />

Figure 14. Inquisitive female Brazilian tapir<br />

(Tapirus terrestris).<br />

Figure 16. Rainforest dwelling giant anteater<br />

(Mymecophaga tridactyla).<br />

16 <strong>Biodiversity</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rewa</strong> <strong>Head</strong><br />

Figure 13. Herd <strong>of</strong> collared Peccary (Tayassu tajacu).<br />

Figure 15. Tayra (Eira Barbara).<br />

Figure 17. Margay (Leopardus wiedii).<br />

Figure 18. Ocelot (Leopardus pardalis). Figure 19. Jaguarundi (Puma yagouaroundi).

The data reveal a typical situation <strong>of</strong> high numbers <strong>of</strong> prey species to predators. Redrumped<br />

agouti (Dasyprocta cristata), paca (Agouti paca) and green acouchy (Myoprocta<br />

exilis) were <strong>the</strong> most abundant, comprising 25.2%, 15.3% and 13.5% respectively <strong>of</strong><br />

mammals recorded. Surprisingly no jaguars (Pan<strong>the</strong>ra onca) were recorded despite<br />

a known high density from previous expeditions. The reason for this is unclear<br />

although may be related to <strong>the</strong> unseasonably high water levels experienced during<br />

<strong>the</strong> expedition, meaning game would be more dispersed throughout <strong>the</strong> forest and<br />

less focussed on <strong>the</strong> river. In comparing our results with those from Pobawau Creek<br />

and Cacique Mountains camera trapping sites set up by CI in <strong>the</strong> Eastern Kanukus RAP,<br />

it is interesting to note that white-lipped and collared peccaries (Tayassu pecari and<br />

T.tajacu) were <strong>the</strong> most abundant species recorded <strong>the</strong>re, whereas <strong>the</strong>y recorded no<br />

Brazilian tapir (Tapirus terrestris), which is <strong>the</strong> fifth most abundant species recorded in<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>Rewa</strong> <strong>Head</strong> camera traps.<br />

When looking at <strong>the</strong> effectiveness <strong>of</strong> identifying medium to large mammalian species in<br />

a short period <strong>of</strong> time using camera traps, table 1 reveals that <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> 17 species observed<br />

this way, all were recorded after only 12 days <strong>of</strong> camera trapping. It appears <strong>the</strong>refore that<br />

in order to record more species requires ei<strong>the</strong>r a much longer sampling period, or a much<br />

broader camera network. This would also give more robust RAI figures.<br />

Observations<br />

We found a high diversity <strong>of</strong> primates, with all <strong>of</strong> Guyana’s 8 species recorded. Of<br />

particular importance were <strong>the</strong> Guianan Shield endemics, <strong>the</strong> black spider monkey (Ateles<br />

paniscus) classified as ‘Vulnerable’ by <strong>the</strong> IUCN, <strong>the</strong> Guianan saki (Pi<strong>the</strong>cia pi<strong>the</strong>cia)<br />

and, <strong>the</strong> Guianan red howler monkey (Alouatta macconnelli), recently upgraded to full<br />

species, <strong>of</strong> which over 7 groups were recorded during drift transects.<br />

Figure 20. Fresh bush dog (Speothos venaticus) print at <strong>the</strong> entrance to a paca den on <strong>the</strong><br />

riverbank. Rare and elusive animals, bush dog are an indicator <strong>of</strong> undisturbed habitat.<br />

Fresh footprints <strong>of</strong> bush dog (Speothos venaticus) seen investigating <strong>the</strong> burrow<br />

<strong>of</strong> a paca along <strong>the</strong> banks <strong>of</strong> a tributary feeding <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rewa</strong> are firm evidence for <strong>the</strong><br />

presence <strong>of</strong> this unusual canid in <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rewa</strong> <strong>Head</strong>. The bush dog is an elusive and<br />

poorly understood animal, with most data on its behaviour and diet derived from<br />

anecdotes. In one study on diet in <strong>the</strong> Brazilian Pantanal, de Souza Lima et al (2009)<br />

recorded that <strong>the</strong> predominant prey found in faeces was <strong>the</strong> nine-banded long-nosed<br />

armadillo (Dasypus novemcinctus), which appears abundant in <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rewa</strong> <strong>Head</strong>.<br />

Although its range is large and it is found throughout Amazonia, it is considered to<br />

<strong>Biodiversity</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rewa</strong> <strong>Head</strong> 17

occur in low densities throughout that extent. The IUCN red list classifies <strong>the</strong> species<br />

as ‘Near Threatened’ being likely to suffer a 10% decline over <strong>the</strong> following decade due<br />

to habitat degradation (Zuercher et al 2008).<br />

Several burrows <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> giant armadillo (Priodontes maximus) were found in <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rewa</strong><br />

<strong>Head</strong>. This species is classified as ‘Vulnerable’ by <strong>the</strong> IUCN.<br />

Figure 21. Brazilian tapir (Tapirus terrestrisi) photographed 10ft from boat.<br />

Brazilian tapir (Tapirus terrestris) appeared to be abundant in <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rewa</strong> <strong>Head</strong>. During<br />

drift surveys we observed 5 in total on <strong>the</strong> banks or in <strong>the</strong> river. As with curassow<br />

and paca, <strong>the</strong> tapirs we encountered appeared remarkably nonchalant about our<br />

presence, allowing us to approach to within several yards without causing alarm.<br />

To give a rough guide to <strong>the</strong> density <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se animals in <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rewa</strong> <strong>Head</strong>, along a 40<br />

mile stretch <strong>of</strong> river, while conducting drift transects over several days, we recorded<br />

97 fresh tapir roads, equating to approximately 2.5 fresh roads every river mile. This<br />

coupled with <strong>the</strong> fact that <strong>the</strong>y were <strong>the</strong> fifth most numerous species in <strong>the</strong> camera<br />

traps suggests a strong, healthy population.<br />

Table 2. Comparison <strong>of</strong> diversity <strong>of</strong> mammalian orders in three survey sites in Guyana.<br />

Site Iwokrama <strong>Rewa</strong> <strong>Head</strong> Eastern Kanukus<br />

Reference<br />

18 <strong>Biodiversity</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rewa</strong> <strong>Head</strong><br />

Lim and Ergsrtom<br />

2004<br />

Pickles, McCann, Holland<br />

2009<br />

Montambault and Missa<br />

2002<br />

Survey duration<br />

(days)<br />

37 + 49 22 8<br />

Marsupialis 7 2 11<br />

Xenarthra 4 4 9<br />

Primates 5 8 8<br />

Carnivora 8 10 16<br />

Perissodactyla 1 1 1<br />

Artiodactyla 4 2 5<br />

Rodentia 15 5 9<br />

44 32 59

Figure 22. Pale-throated three-toed sloth (Dasypus tridactylus) photographed at <strong>the</strong> river’s edge.<br />

Jaguar were glimpsed twice above <strong>the</strong> falls and <strong>the</strong>ir presence was noted in fresh<br />

scratch patches and scats left near camp. However, due to <strong>the</strong> high level <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> river<br />

following several torrential downpours, <strong>the</strong>re was a lack <strong>of</strong> exposed rocks where<br />

<strong>the</strong>y have been filmed basking on previous trips. During a 6 week trip above Corona<br />

Falls in 2004 for instance, Ashley Holland and Gordon Duncan filmed 10 jaguars at<br />

extremely close proximity. Jaguarundi (Puma yagouaroundi) was seen once. From<br />

sightings and camera trap evidence we recorded five <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> six species <strong>of</strong> felid known<br />

to exist in Guyana, and given <strong>the</strong> nature <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> habitat and lack <strong>of</strong> disturbance, it is<br />

likely that <strong>the</strong> oncilla (Leopardus tigrinus) will exist in <strong>the</strong> area as well. The cryptic<br />

pale-throated three-toed sloth (Bradypus tridactylus) was also seen on drift surveys,<br />

three were recorded in <strong>the</strong> duration <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> expedition.<br />

In total we recorded <strong>the</strong> presence <strong>of</strong> 33 species <strong>of</strong> non-volant mammal, including<br />

2 marsupials, 4 xenarthrans, 8 primates, 10 carnivores, 1 perrissodactyl, 2 artiodactyls,<br />

and 6 rodents, equating to 35% <strong>of</strong> Guyana’s total non-volant, non-marine mammalian<br />

fauna. Guyana’s total mammalian species count is 225, 121 <strong>of</strong> which are bats and<br />

8 are marine cetaceans. In comparing <strong>the</strong> results <strong>of</strong> our survey in <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rewa</strong> <strong>Head</strong> with<br />

those from o<strong>the</strong>r surveys in Guyana such as Iwokrama and <strong>the</strong> Eastern Kanukus, one<br />

should note that no small-mammal trapping took place during our expedition and we<br />

only present in our species list animals recorded during <strong>the</strong> course <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> expedition.<br />

<strong>Biodiversity</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rewa</strong> <strong>Head</strong> 19

Chapter 2. Bird Species Diversity and Relative Abundance<br />

Avian diversity and relative abundance was measured by conducting a series <strong>of</strong> spot<br />

counts drifting downstream along 60 miles <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rewa</strong> <strong>Head</strong>, and through mist netting<br />

at camps set roughly 12 miles apart along from <strong>the</strong> East-West Split to Powis Falls.<br />

For reference we used Steven Hilty’s Birds <strong>of</strong> Venezuela in conjunction with Robin Restall’s<br />

Birds <strong>of</strong> Nor<strong>the</strong>rn South America and <strong>the</strong> Smithsonian Institution’s A Field Checklist <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> Birds <strong>of</strong> Guyana. In English names we have chosen to follow Hilty’s nomenclature.<br />

Principal Findings<br />

• 187 species recorded through drift spot counts and mist netting. This rises to<br />

251 with <strong>the</strong> inclusion <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Smithsonian Institution’s 2006 data.<br />

• 10 Guianan Shield Endemics.<br />

• Confirmed presence <strong>of</strong> threatened harpy and crested eagle.<br />

• High diversity <strong>of</strong> raptors with 12 species recorded.<br />

Mist Netting Survey<br />

We conducted mist net surveys at 5 points along <strong>the</strong> 60 miles <strong>of</strong> river on which we<br />

were focussing our research. We used three 40ft standard BTO NR nets with a mesh<br />

size <strong>of</strong> 3cm. These proved fine enough to capture small birds such as antbirds and<br />

hummingbirds, and strong enough to capture species up to <strong>the</strong> size <strong>of</strong> a pigeon.<br />

Figure 23. Ash and Rob identifying a plain-brown woodcreeper (Dendrocincla fuliginosa).<br />

Method<br />

The nets were erected 50-200m from camp in a variety <strong>of</strong> habitats such as near vine<br />

tangles, tree falls and along <strong>the</strong> river edge in order to catch unobtrusive species which<br />

would not have been recorded during a drift transect. The nets were erected at 6am<br />

and taken down at 5:30pm during surveys and were checked every hour. Five netting<br />

sites were used from <strong>the</strong> East-West <strong>Rewa</strong> split down to Powis Falls covering a variety<br />

<strong>of</strong> habitats from open, scrubby bush, to palm thickets and dense forest. Ashley Holland<br />

has been identifying birds in <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rewa</strong> for several years and he, Ryol Merriman and<br />

Kevin Alvin had worked previously with <strong>the</strong> Smithsonian Institution during <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

collecting expedition in 2006 and were adept at removing and identifying birds in <strong>the</strong><br />

nets, being familiar with <strong>the</strong> majority <strong>of</strong> species caught.<br />

20 <strong>Biodiversity</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rewa</strong> <strong>Head</strong>

Figure 24. A White-plumed Antbird (Pithys<br />

albifrons).<br />

Figure 25. Blue-crowned Motmot (Motmotus<br />

motmota).<br />

Figure 26a. Rufous-belled antwren (Myrmo<strong>the</strong>rula guttata) and Figure 26b. brown-bellied<br />

antwren (Myrmo<strong>the</strong>rula gutturalis), two Guianan Shield endemics.<br />

Figure 27. Rufous-throated antbird (Gymnopithys<br />

rufigula).<br />

Figure 28. Pygmy kingfisher, (Chloroceryle<br />

aenea).<br />

Figure 29. Variegated antpitta (Grallaria varia). Figure 30. Red-necked woodpecker (Campephilus<br />

rubricollis)<br />

<strong>Biodiversity</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rewa</strong> <strong>Head</strong> 21

Results<br />

In total 420 mist net hours were accumulated (140 hours per net) at <strong>the</strong> five netting<br />

sites. 91 birds were caught, resulting in 41 different species being identified. Four birds<br />

were unidentified; two <strong>of</strong> which were likely to have been female long-winged antbirds<br />

(Myrmo<strong>the</strong>rula longipennis). Twenty-three <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> species caught in mist nets were not<br />

observed during <strong>the</strong> drift transects.<br />

The most frequently caught family was <strong>the</strong> Thamnophilidae with 15 <strong>of</strong> all species<br />

and 27% <strong>of</strong> total number <strong>of</strong> individuals caught, followed by <strong>the</strong> Dendrocolaptidae (5<br />

species) and Trochilidae (4 species). The most common species encountered in <strong>the</strong><br />

nets was <strong>the</strong> wedge-billed woodcreeper (Glyphorynchus spirurus).<br />

Drift Spot Count Survey<br />

Method<br />

In conducting drift spot count surveys, we divided <strong>the</strong> river from <strong>the</strong> East-West Split at<br />

N2° 37.740’ W58° 37.040’ down to Corona Falls at N3° 10.579’ W58° 40.433’, into 5 mile<br />

stretches. Each stretch was surveyed once by drifting downstream with three spotters in a<br />

boat, taking turns at inputting <strong>the</strong> data, resulting in a single surveyed transect <strong>of</strong> 60 miles.<br />

We used a portable mp3 player containing <strong>the</strong> vocalisations <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> birds <strong>of</strong> Venezuela to<br />

identify calls and song. We kept to mid-river when it was narrow enough to cover both<br />

banks, but when <strong>the</strong> river widened to over 40m we kept within 15m <strong>of</strong> one bank. To<br />

standardise <strong>the</strong> surveys we attempted to maintain a steady speed <strong>of</strong> around 2 miles per<br />

hour, by paddling through slower stretches though <strong>the</strong> speed invariably depended on <strong>the</strong><br />

volume <strong>of</strong> water flowing. Following heavy rains transect duration was shorter by at least<br />

half an hour due to <strong>the</strong> increased flow. Occasionally it was necessary to break up a stretch,<br />

such as when portaging. When this occurred we halted <strong>the</strong> count until <strong>the</strong> obstacle had<br />

been passed. Spot counts were carried out in <strong>the</strong> morning, when animal activity was<br />

greatest. However, due to <strong>the</strong> logistics <strong>of</strong> moving camp, several times we had to carry on<br />

with conducting <strong>the</strong> surveys into <strong>the</strong> afternoon, when activity generally declined.<br />

Figure 31. Crimson topaz (Topaza pella). In total nine<br />

species <strong>of</strong> hummingbird were recorded in <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rewa</strong>.<br />

22 <strong>Biodiversity</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rewa</strong> <strong>Head</strong><br />

Results<br />

We recorded over 4000 birds<br />

during <strong>the</strong> transects, resulting in<br />

<strong>the</strong> identification <strong>of</strong> 158 species<br />

through both visual observation<br />

and vocalisations. Through <strong>the</strong><br />

combination <strong>of</strong> sightings made<br />

on drift transects, mist-netting,<br />

opportunistic sightings and<br />

vocalisations, we positively identified<br />

187 species from 48 different<br />

families. The most diverse family<br />

observed was <strong>the</strong> Tyrannidae<br />

(34 species) closely followed by<br />

Thamnophilidae (31 species), <strong>the</strong>n<br />

Accipitridae (11 species), Psittacidae<br />

(11 species), Ardeidae (10 species)<br />

and Trochilidae and Thraupidae (9<br />

species). The most abundant family<br />

was <strong>the</strong> Hirudinidae comprising<br />

20% <strong>of</strong> total observations,<br />

followed by <strong>the</strong> Apodidae, with<br />

16%, Psittacidae with 10% <strong>the</strong>n<br />

Icteridae with 5%.<br />

Discussion<br />

In August 2006 Ashley Holland led a Smithsonian Institution collecting expedition to <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Rewa</strong>, coordinated by Chris Milensky and Brian Schmidt. They set up two mist netting<br />

sites, one above Corona Falls at Louis Creek (2 58’ 17” N, 58 35’ 37” W) and <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

below. Above <strong>the</strong> falls <strong>the</strong>y erected 20 nets and netted for 10 days. Combining our data

with <strong>the</strong> Smithsonian’s gives a more complete picture <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> region’s avifauna as <strong>the</strong>y were<br />

<strong>the</strong>re in <strong>the</strong> wet August, while we were <strong>the</strong>re in January, entering <strong>the</strong> dry season. In <strong>the</strong><br />

species list we present our observations toge<strong>the</strong>r with those <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Smithsonian Institute<br />

for direct comparison. This brings <strong>the</strong> total number <strong>of</strong> bird species seen in <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rewa</strong> to 250<br />

and number <strong>of</strong> families to 53, equating to 31% <strong>of</strong> all Guyana’s bird species (796).<br />

The difference in season is most apparent in <strong>the</strong> presence <strong>of</strong> migratory species such as<br />

<strong>the</strong> Osprey (Pandion haliaetus) and <strong>the</strong> relative abundance <strong>of</strong> frugivorous species such<br />

as <strong>the</strong> Psittacidae which were no doubt more noticeable in January due to congregations<br />

forming on fruiting trees. Likewise, whereas <strong>the</strong> Smithsonian recorded <strong>the</strong> family Ictericidae<br />

as Uncommon, we <strong>of</strong>ten encountered large flocks <strong>of</strong> yellow-rumped cacique (Cacicus<br />

cela), red-rumped cacique (Cacicus haemorrhous) and crested oropendola (Psarocolius<br />

decumanus) as <strong>the</strong>y were nesting, leading us to surmise that <strong>the</strong>y were Common in <strong>the</strong> area.<br />

Of chief interest in <strong>the</strong> sightings are 10 Guianan Shield endemics, <strong>the</strong> Guianan toucanet<br />

(Selenidera culik), green aracari (Pteroglossus viridis), black nunbird (Monasa atra),<br />

rufous-throated antbird (Gymnopithys rufigula), brown-bellied antwren (Myrmo<strong>the</strong>rula<br />

gutturalis), rufous-belled antwren (Myrmo<strong>the</strong>rula guttata), caica parrot (pionopsitta caica)<br />

and black curassow (Crax alector). Two species recorded have particularly small ranges<br />

within <strong>the</strong> Guianan Shield ecoregion, Todd’s antwren (Herpsilochmus stictocephalus)<br />

and little hermit (Phaethornis longuemareus). This expedition also confirms <strong>the</strong> presence<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> awesome harpy eagle (Harpia harpyja) and crested eagle (Morphnus guianensis)<br />

in <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rewa</strong> <strong>Head</strong>. A potential sighting <strong>of</strong> a dusky purpletuft (Idopleura fusca) is worth<br />

mentioning, although fur<strong>the</strong>r confirmation is required that <strong>the</strong>y are found in this area.<br />

The species’ current known range in Guyana is restricted to Iwokrama Reserve, which<br />

would make <strong>the</strong> discovery <strong>of</strong> a second population extremely important.<br />

Figure 32. The crested eagle (Morphnus guianensis), classed as<br />

‘’near threatened” in <strong>the</strong> IUCN Red List.<br />

The presence <strong>of</strong> harpy and<br />

crested eagle, with good<br />

observations made reflects <strong>the</strong><br />

pristine nature <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> habitat<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rewa</strong> <strong>Head</strong>, with large<br />

mature kapok trees (Ceiba<br />

pentandra) providing nesting<br />

sites and a high abundance<br />

<strong>of</strong> primate, sloth and cracid<br />

prey to sustain <strong>the</strong> population.<br />

Shortly after our expedition<br />

Duane de Freitas reported<br />

10 harpy sightings in <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Rewa</strong> <strong>Head</strong>, including several<br />

pairs, suggesting that <strong>the</strong>se<br />

birds are breeding above<br />

<strong>the</strong> falls. The abundance and<br />

naivety <strong>of</strong> cracids, both black<br />

curassow (Crax alector) and<br />

blue-throated piping-guan (Pipile cumanensis), favoured game birds, illustrates <strong>the</strong> fact<br />

that hunting does not take place in <strong>the</strong> area. The high diversity <strong>of</strong> raptors recorded is <strong>of</strong><br />

particular interest, six <strong>of</strong> which were not recorded by <strong>the</strong> Smithsonian Institute during <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

collecting expedition in 2006, and again points to a pristine habitat rich in prey.<br />

When seen in <strong>the</strong> context <strong>of</strong> Conservation International’s 2001 Rapid Assessment Program<br />

to <strong>the</strong> Eastern Kanukus and Lower Kwitaro (Montambau and Missa 2003), our findings<br />

become more relevant. CI recorded a total <strong>of</strong> 264 species in <strong>the</strong> Lower Kwitaro, Eastern<br />

Kanukus after combining data from <strong>the</strong>ir 2001 RAP with that <strong>of</strong> Davis Finchs survey in<br />

1998. Of <strong>the</strong> combined 250 species from ZSL’s 2009 expedition and <strong>the</strong> Smithsonian’s 2006<br />

expedition, 68 were not recorded in <strong>the</strong> Eastern Kanukus and Lower Kwitaro, <strong>the</strong>se are<br />