MPA Symposium - Zoological Society of London

MPA Symposium - Zoological Society of London

MPA Symposium - Zoological Society of London

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

symposium<br />

• AT THE ZOOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF LONDON •<br />

MARINE PROTECTED AREAS<br />

ON THE HIGH SEAS<br />

Thursday 3 and Friday 4 February 2011<br />

Organised by Kirsty Kemp<br />

Matthew Gollock<br />

Alex Rogers<br />

The Meeting Rooms<br />

The <strong>Zoological</strong> <strong>Society</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>London</strong><br />

Regent’s Park<br />

<strong>London</strong> NW1 4RY<br />

www.zsl.org/science/scientific-meetings<br />

Image credits (from top): Alex Rogers and Fundação Rebik<strong>of</strong>f-Niggeler; Kirsty Kemp and Fundação Rebik<strong>of</strong>f-<br />

Niggeler; Oddgeir Alvheim; Philipp Boersch-Supan; Oddgeir Alvheim; Philipp Boersch-Supan; Oddgeir Alvheim

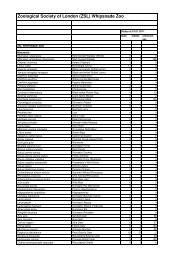

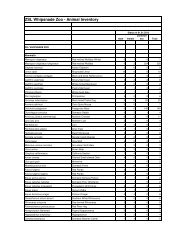

MARINE PROTECTED AREAS ON THE HIGH SEAS<br />

AN INTERNATIONAL SYMPOSIUM HELD AT ZSL ON 3 AND 4 FEBRUARY 2011<br />

ABSTRACTS OF TALKS<br />

9.15–9.30 Welcome from Tim Blackburn<br />

Director, Institute <strong>of</strong> Zoology, <strong>Zoological</strong> <strong>Society</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>London</strong><br />

SESSION I: DO <strong>MPA</strong>s WORK? (PROGRESS TOWARDS 2012 GOALS and the STATE OF<br />

PROGRESS ON HIGH SEAS <strong>MPA</strong>s)<br />

Chair: Kirsty Kemp (Institute <strong>of</strong> Zoology, ZSL)<br />

9.30–9.55 The need for High Sea Marine Protected Areas<br />

Alex D. Rogers, Department <strong>of</strong> Zoology, University <strong>of</strong> Oxford, UK<br />

The oceans have a mean depth <strong>of</strong> 3800m and comprise 90% <strong>of</strong> the Earth’s biosphere, the<br />

majority <strong>of</strong> which is constituted by the high seas. This region includes the water column and<br />

seabed and hosts a startling variety <strong>of</strong> ecosystems, a high diversity <strong>of</strong> species and plays a<br />

pivotal role in the Earth system. At present, the high seas are governed through a principle <strong>of</strong><br />

mare liberum or freedom <strong>of</strong> the seas. However, the dramatic increase in human activities<br />

exploiting the resources <strong>of</strong> the high seas or impacting on them has rendered this concept a<br />

recipe for uncontrolled destruction <strong>of</strong> the natural capitol <strong>of</strong> our oceans. Moreover, the variety <strong>of</strong><br />

human activities now taking place in our seas will inevitably force us to adopt marine spatial<br />

planning not only within the exclusive economic zones <strong>of</strong> states but beyond them, in the high<br />

seas. It is essential that marine protected areas form a key part <strong>of</strong> such efforts to manage<br />

activities on the high seas. The United Nations Convention on the Law <strong>of</strong> the Sea (UNCLOS)<br />

has resulted in management <strong>of</strong> some activities in the oceans. Mining, for example, is managed<br />

by the International Seabed Authority, whilst fishing, in many areas <strong>of</strong> the high seas is managed<br />

with varying degrees <strong>of</strong> success by Regional Fisheries Management Organisations. However,<br />

conventional forms <strong>of</strong> management are <strong>of</strong>ten either focused upon the biotic resource being<br />

exploited (target species) or has a narrow regional focus. Such forms <strong>of</strong> management allow the<br />

degradation <strong>of</strong> diversity at a variety <strong>of</strong> levels and will inevitably end in the extinction <strong>of</strong> species<br />

and loss <strong>of</strong> goods and services to humankind. Marine protected areas can protect the wider<br />

diversity <strong>of</strong> marine ecosystems including by-catch species from fishing and important biophysical<br />

structure in the oceans critical for ecosystem integrity. They can allow the rebuilding <strong>of</strong> fish<br />

stocks with associated overspill and improved recruitment to the surrounding ecosystem and act<br />

as an important insurance mechanism when management fails. Science must now address<br />

important questions as to how to maximise the conservation and economic benefits <strong>of</strong> networks<br />

<strong>of</strong> high seas marine protected areas whilst fitting them into a broader context <strong>of</strong> ocean<br />

management. Politicians, lawyers and managers must work towards filling the legislative gaps<br />

that currently prevent the adoption <strong>of</strong> a holistic approach to sustainable management <strong>of</strong><br />

ecosystems beyond national jurisdiction.<br />

For further information, please contact: Publications and Meetings, ZSL, Regent’s Park, <strong>London</strong> NW1 4RY, UK. anne.braae@zsl.org

MARINE PROTECTED AREAS ON THE HIGH SEAS<br />

AN INTERNATIONAL SYMPOSIUM HELD AT ZSL ON 3 AND 4 FEBRUARY 2011<br />

ABSTRACTS OF TALKS<br />

9.55–10.20 Progress with global ocean protection<br />

Dan Laffoley, Senior Advisor, Marine Science and Conservation, IUCN, and<br />

Marine Vice Chair, IUCN’s World Commission on Protected Areas UK<br />

In recent decades many countries have signed up to targets for the protection and management<br />

<strong>of</strong> the world’s ocean. This is at a global scale, through such fora and agreements as the World<br />

Summit on Sustainable Development and the Convention on Biological Diversity. A number <strong>of</strong><br />

regional targets have also been created within this context by country leaders working together,<br />

such as in the coral triangle in the Far East and the Caribbean. At the same time there has been<br />

a growing recognition <strong>of</strong> the need to focus attention on areas beyond national jurisdictions, as<br />

the footprint <strong>of</strong> human impacts moves ever further from the coast into deeper waters in search <strong>of</strong><br />

resources. In recent years a significant scale-up <strong>of</strong> activity has occurred to secure protection for<br />

the High Seas.<br />

This presentation will provide an introductory context and overview to the symposium, by<br />

considering progress against global ocean protection targets. It will explain the current<br />

achievements, the amount <strong>of</strong> ocean now within <strong>MPA</strong>s, as well as identifying challenges for the<br />

future. This will include an understanding <strong>of</strong> significant moves by some countries to scale-up the<br />

level <strong>of</strong> protection provided, perhaps 100 fold, through the identification <strong>of</strong> large <strong>MPA</strong>s that are<br />

<strong>of</strong>ten fully no-take, where extraction <strong>of</strong> living resources is prohibited. The presentation will also<br />

touch on some <strong>of</strong> the new guidance and mechanisms that are being employed to attract greater<br />

attention to ocean protection, and to engage a greater understanding in policy advisors and<br />

decision makers <strong>of</strong> the need for urgent action.<br />

10.20–10.45 Quantifying the impact <strong>of</strong> the almost complete cessation <strong>of</strong> commercial<br />

fishing on the Piscean population <strong>of</strong> the northern North Sea during<br />

World War II<br />

Doug Beare, Wageningen IMARES, Netherlands<br />

Understanding the mechanisms via which commercial fishing pressures, management regimes<br />

and environmental changes interact with the ecology <strong>of</strong> wild fish populations is a key question<br />

for fisheries management science. Such questions are, however, difficult to address using<br />

recent time-series datasets, say 1950 to the present, because fishing pressure was sustained<br />

and ubiquitous during that period. The only reliable way to separate the effect <strong>of</strong> fishing from that<br />

<strong>of</strong> the environment would be to set up huge 'designed experiments' in which different marine<br />

regions were subjected to different 'treatments'. Manipulation <strong>of</strong> such large ecosystems is ,<br />

however, probably impossible. An 'experiment' did, however, occur in the North Sea during<br />

World War II (WWII) when commercial fishing ceased almost completely. Using scientific trawl<br />

survey data collected before and after the WWII, I will show how the Piscean population (agestructure,<br />

size structure, diversity, species richness) reacted to this sudden change in<br />

exploitation. I will also comment on the lessons these observations can teach us in the context<br />

<strong>of</strong> Marine Protected Areas.<br />

10.45–11.15 POSTER SESSION (TEA/COFFEE)<br />

For further information, please contact: Publications and Meetings, ZSL, Regent’s Park, <strong>London</strong> NW1 4RY, UK. anne.braae@zsl.org

MARINE PROTECTED AREAS ON THE HIGH SEAS<br />

AN INTERNATIONAL SYMPOSIUM HELD AT ZSL ON 3 AND 4 FEBRUARY 2011<br />

ABSTRACTS OF TALKS<br />

SESSION I (cont): DO <strong>MPA</strong>s WORK? (PROGRESS TOWARDS 2012 GOALS and the STATE<br />

OF PROGRESS ON HIGH SEAS <strong>MPA</strong>s)<br />

Chair: Matthew Gollock (International Marine and Freshwater Conservation Programme, ZSL)<br />

11.15–11.40 Extrapolating lessons learned from coastal and nearshore <strong>MPA</strong>s to<br />

increase efficiency and connectivity for effective high seas <strong>MPA</strong>s<br />

Colleen Corrigan, United Nations Environment Programme- World<br />

Conservation Monitoring Centre, Cambridge, UK<br />

As we move toward the World Summit on Sustainable Development 2012 marine target and the<br />

continued implementation <strong>of</strong> the Convention on Biological Diversity’s Programme <strong>of</strong> Work on<br />

Marine and Coastal Biodiversity, it is clear that we are globally short <strong>of</strong> our marine protection<br />

targets and that a large percentage <strong>of</strong> the ocean is simply not represented in current marine<br />

protection efforts. Despite the trend toward establishment <strong>of</strong> large-scale marine protected areas<br />

(<strong>MPA</strong>s), it is imperative that we accelerate our progress in protecting areas <strong>of</strong> the high seas that<br />

are severely underrepresented. As technical capacities to access, research, and monitor high<br />

seas areas improves, so does our knowledge about best practices in protecting and effectively<br />

managing nearshore marine environments. In addition, we have underestimated the contribution<br />

<strong>of</strong> indigenous peoples and local communities who can provide lessons from their customary<br />

practices in governing marine managed and protected areas, as well as important socioeconomic<br />

considerations that can be beneficial to high seas <strong>MPA</strong>s. There is a great need to<br />

begin synthesizing lessons learned from the processes that oversee the more than 5000 existing<br />

<strong>MPA</strong>s around the world so that we can adapt and apply these lessons to the successful<br />

implementation <strong>of</strong> <strong>MPA</strong>s on the high seas. This presentation will explore a range <strong>of</strong> concepts<br />

that can be extrapolated from our collective years <strong>of</strong> rich experience in designing, planning and<br />

implementing coastal <strong>MPA</strong>s to help increase the efficiency toward which we plan and implement<br />

high seas <strong>MPA</strong>s. Insights will be shared from a Pacific-based mapping project that reviews<br />

large-scale connectivity across political boundaries, bringing together the biological processes<br />

and species-specific migratory routes that extend from near-shore areas to the high seas. It will<br />

also present input on the linkage between local communities, social contexts, and cultural<br />

customs that can influence our collective work in protecting static and dynamic areas <strong>of</strong> the high<br />

seas.<br />

11.40–12.05 Assessing capture risk <strong>of</strong> pelagic fish by satellite-tracked longline<br />

vessels and the effectiveness <strong>of</strong> Marine Protected Areas<br />

Nicolas E. Humphries 1 , Nuno Queiroz 1,2 , Gonzalo Mucientes 3 , Lara Sousa 2<br />

and David W. Sims 1<br />

1 Marine Biological Association <strong>of</strong> the United Kingdom, Plymouth, UK<br />

2 CIBIO – U.P., Centro de Investigação em Biodiversidade e Recursos<br />

Genéticos, Campus Agrário de Vairão, Vairão, Portugal<br />

3 Instituto de Investigaciones Marinas, CSIC, Vigo, Spain<br />

In order to assess whether a possible Marine Protected Area (<strong>MPA</strong>) will be effective it is<br />

desirable to have an understanding <strong>of</strong> the three dimensional spatio-temporal interactions<br />

between the fishing fleet and the fish population needing protection. Without such reference,<br />

an <strong>MPA</strong> could feasibly be created where fish might be abundant but where fishing pressure is<br />

already low, or may lead to unnecessarily reduced fishing in areas where there is in fact little<br />

sustained interaction with target, or perhaps more likely, by-caught species. Ideally, therefore,<br />

For further information, please contact: Publications and Meetings, ZSL, Regent’s Park, <strong>London</strong> NW1 4RY, UK. anne.braae@zsl.org

MARINE PROTECTED AREAS ON THE HIGH SEAS<br />

AN INTERNATIONAL SYMPOSIUM HELD AT ZSL ON 3 AND 4 FEBRUARY 2011<br />

ABSTRACTS OF TALKS<br />

detailed information about the movements <strong>of</strong> both fish and fishery should be used when<br />

planning an <strong>MPA</strong>.<br />

In the case <strong>of</strong> the Spanish and Portuguese longlining fleets, vessel movements are tracked by<br />

GPS and recorded as part <strong>of</strong> the vessel monitoring system (VMS). Using this data we mapped<br />

the distribution <strong>of</strong> fishing effort spatially and through time for the Northeast Atlantic, providing<br />

interesting insights into the spatio-temporal distribution <strong>of</strong> fishing effort. Because the vessels<br />

target swordfish (Xiphias gladius) it is likely that the observed distribution reflects that <strong>of</strong> the<br />

movements, migrations and habitat preferences <strong>of</strong> swordfish. Blue sharks (Prionace glauca)<br />

are an important by-catch species <strong>of</strong> longline vessels and, because the sharks have different<br />

movements and habitat preferences to swordfish, the impact <strong>of</strong> the fishery on the species is<br />

more difficult to assess, especially as there is no formal management <strong>of</strong> pelagic shark catches<br />

in this area.<br />

Satellite tracking data on individual blue sharks has allowed us to record their thermal<br />

preferences and general movement patterns. This information was used to parameterise a<br />

simulation <strong>of</strong> a generic pelagic predator, with similar movement patterns and seasonal<br />

migrations to the blue shark, moving through the Northeast Atlantic. Individual, annual<br />

movements were then ‘run’ in time with the longline vessel movements and close spatial<br />

interactions, indicative <strong>of</strong> capture events or increased capture risk, were recorded. We then<br />

placed different sized <strong>MPA</strong>s at different locations to assess the relative impact on capture risk<br />

for the model sharks. The results <strong>of</strong> the analysis will be described. It is evident that the results<br />

provide interesting insights into the effect that <strong>MPA</strong>s, fleet reductions or seasonal closures<br />

might have on the fishing pressure experienced by non-target species.<br />

12.05–12.30 High Seas Marine Protected Areas: How could they work?<br />

Phil MacMullen, Seafish, UK<br />

Fisheries are notoriously difficult to manage. With all the resources available in developed<br />

economies it has taken over 100 years to understand the science <strong>of</strong> exploited marine<br />

ecosystems, and governments are still struggling to apply this understanding effectively.<br />

Fishermen want to be independent and they instinctively resist most attempts at monitoring and<br />

control. Prescriptive management has its place but can only ever be a part <strong>of</strong> the answer.<br />

Market forces are another part <strong>of</strong> the jigsaw but how do we use them most effectively? We need<br />

to put together a package <strong>of</strong> measures and provisions tailored to work with the forces that drive<br />

the behaviour <strong>of</strong> fishermen. This presentation looks at some lessons learned and identifies the<br />

tools in the toolbox, and the factors that need to be taken into account, if we are to seek<br />

confidence in compliance.<br />

12.30–13.00 DISCUSSION LED BY PANEL OF SESSION I SPEAKERS<br />

13.00–14.00 LUNCH<br />

For further information, please contact: Publications and Meetings, ZSL, Regent’s Park, <strong>London</strong> NW1 4RY, UK. anne.braae@zsl.org

MARINE PROTECTED AREAS ON THE HIGH SEAS<br />

AN INTERNATIONAL SYMPOSIUM HELD AT ZSL ON 3 AND 4 FEBRUARY 2011<br />

ABSTRACTS OF TALKS<br />

SESSION II: BARRIERS TO PROGRESS<br />

Chair: Alex D. Rogers (University <strong>of</strong> Oxford, UK)<br />

14.00–14.25 Legal and technical barriers towards progress<br />

Matthew Gianni, Deep Sea Conservation Coalition, Netherlands<br />

Abstract not available at time <strong>of</strong> print.<br />

14.25–14.50 Monitoring, control and surveillance options for high seas Marine<br />

Protected Areas<br />

John Pearce, MRAG Ltd, UK<br />

Marine Protected Areas in high seas fisheries have been highlighted as a possible means to<br />

protect habitats and fish stocks that may be subjected to increased levels <strong>of</strong> fishing effort by<br />

both legitimate regulated and unregulated fishing vessels. The particular monitoring, control<br />

and surveillance requirements <strong>of</strong> different types <strong>of</strong> high seas <strong>MPA</strong>s are discussed. The current<br />

toolkit <strong>of</strong> potential methods and means <strong>of</strong> monitoring, control and surveillance <strong>of</strong> fisheries are<br />

then presented along with their applicability to the requirements. The costs <strong>of</strong> MCS <strong>of</strong> high<br />

seas <strong>MPA</strong>s are highlighted.<br />

14.50–15.15 Establishing <strong>MPA</strong>s where the high seas overlays the continental shelf<br />

Daniel Owen, Fenners Chambers, UK<br />

Where coastal States have an outer continental shelf (i.e. a shelf extending beyond 200 nm from<br />

the baseline), the water column above that outer shelf will be high seas. The scientific case for<br />

an <strong>MPA</strong> in such circumstances may relate to the water column or to the seabed or both. This<br />

presentation will examine the interaction between the international law <strong>of</strong> the sea's regimes for<br />

the high seas and the continental shelf, with a view to identifying how intergovernmental<br />

organisations, such as regional seas organisations and regional fisheries management<br />

organisations, may cooperate with relevant coastal States, and vice versa, in order to achieve<br />

effective protection for the marine environment.<br />

15.15–15.45 POSTER SESSION (TEA/COFFEE)<br />

For further information, please contact: Publications and Meetings, ZSL, Regent’s Park, <strong>London</strong> NW1 4RY, UK. anne.braae@zsl.org

MARINE PROTECTED AREAS ON THE HIGH SEAS<br />

AN INTERNATIONAL SYMPOSIUM HELD AT ZSL ON 3 AND 4 FEBRUARY 2011<br />

ABSTRACTS OF TALKS<br />

SESSION III: SOLUTIONS AND POLICY<br />

Chair: Alex D. Rogers (University <strong>of</strong> Oxford, UK)<br />

15.45–16.10 The economic aspect <strong>of</strong> <strong>MPA</strong> development<br />

Pippa Gravestock, University <strong>of</strong> York, UK<br />

This presentation will look at the current state <strong>of</strong> knowledge <strong>of</strong> the costs and benefits <strong>of</strong> High<br />

Seas Marine Protected Areas (HS<strong>MPA</strong>s).<br />

Marine conservationists operate in an environment where their plans and priorities are set<br />

against very powerful forces – political, economic and cultural. Any attempt to shift policy<br />

towards a more benign framework for the world’s oceans must understand the broader socioeconomic<br />

context in which policy objectives are pursued. This applies especially in an<br />

environment <strong>of</strong> scarce resources and constant competition for funds.<br />

The main focus <strong>of</strong> this presentation will be on the costs <strong>of</strong> HS<strong>MPA</strong> implementation. A practical<br />

understanding <strong>of</strong> implementation costs is highly desirable for effective planning as the various<br />

programmes currently attempting to establish HS<strong>MPA</strong> networks around the world move forward.<br />

Looking at data from HS<strong>MPA</strong> proxies, such as large <strong>of</strong>f-shore protected areas and fishery<br />

management zones, it seems likely that the costs <strong>of</strong> implementing a HS<strong>MPA</strong> or network <strong>of</strong><br />

protected areas will be considerable, not always easy to estimate in advance and likely to be<br />

incurred by a range <strong>of</strong> service providers. The scale <strong>of</strong> these costs in any given situation will<br />

depend on a range <strong>of</strong> criteria including the size <strong>of</strong> the protected area, its objectives,<br />

management organisations and location and the governance <strong>of</strong> the relevant fisheries.<br />

Not all <strong>of</strong> the costs <strong>of</strong> implementing a HS<strong>MPA</strong> or a network <strong>of</strong> HS<strong>MPA</strong>s are the direct<br />

implementation costs. Another group <strong>of</strong> costs that must be considered are the opportunity costs<br />

associated with implementation – in other words the costs <strong>of</strong> forsaking certain economic<br />

activities in order to create the protected area. Research suggests that the potential opportunity<br />

costs <strong>of</strong> creating a HS<strong>MPA</strong> network covering 10% <strong>of</strong> the high seas would be de minimis in<br />

relation to the size <strong>of</strong> the global fishery catch: representing a reduction <strong>of</strong> less than 1% in the<br />

annual marine capture fisheries take. In addition, only a handful <strong>of</strong> the mostly wealthy western<br />

nations who dominate the high seas bottom trawl industry (estimated to be 12 in total) would be<br />

impacted by the creation <strong>of</strong> such an area.<br />

The establishment <strong>of</strong> a network <strong>of</strong> HS<strong>MPA</strong>s should also bring benefits, including the<br />

preservation <strong>of</strong> a healthy marine ecosystem for future generations. Efforts to analyse and<br />

quantify the economic value <strong>of</strong> these benefits are still at an early stage and this is a subject that<br />

will be reviewed only at a high level in this presentation.<br />

When assessing the overall case for creating HS<strong>MPA</strong>s, some obvious questions relate to who<br />

should pay for them, how funding should be channelled and to whom the benefits would accrue.<br />

In some cases there may be a disconnection between who is asked to bear the costs and who<br />

sees the benefits. One pool <strong>of</strong> money <strong>of</strong>ten identified by conservationists as an obvious source<br />

<strong>of</strong> funding for a global HS<strong>MPA</strong> programme is the vast subsidies issued by governments to high<br />

seas fishing fleets. Achieving a redirection <strong>of</strong> this funding is not something that seems likely to<br />

happen any time soon – the majority <strong>of</strong> subsidies to high seas bottom-trawl fleets are made by<br />

countries with little or no historical interest in marine conservation priorities.<br />

For further information, please contact: Publications and Meetings, ZSL, Regent’s Park, <strong>London</strong> NW1 4RY, UK. anne.braae@zsl.org

MARINE PROTECTED AREAS ON THE HIGH SEAS<br />

AN INTERNATIONAL SYMPOSIUM HELD AT ZSL ON 3 AND 4 FEBRUARY 2011<br />

ABSTRACTS OF TALKS<br />

16.10–16.35 What is needed in terms <strong>of</strong> law to facilitate progress towards the 2012<br />

goals?<br />

Kristina M. Gjerde and Anna Rulska-Domino, IUCN Global Marine Programme,<br />

Poland<br />

The biggest hurdle to establishing protected areas in the ocean beyond national jurisdiction was<br />

long thought to be scientific. However, initiatives such as the Census <strong>of</strong> Marine Life<br />

(www.CoML.org) and the Global Marine Biodiversity Initiative (www.GOBI.org) are shedding new<br />

light on the once remote open ocean and deep sea, making it realistic to seek to identify key<br />

habitats and migratory corridors.<br />

Challenges however remain on the institutional and legal side. In 2008, the parties to the<br />

Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) adopted scientific criteria for identifying ‘ecologically or<br />

biologically significant areas’ and guidance for designing networks <strong>of</strong> protected areas in the open<br />

ocean and deep sea. In 2010, the CBD agreed a scientific process through regional workshops<br />

to help States to identify ecologically or biologically significant areas based on these CBD<br />

criteria.<br />

While specific places can be protected through existing international and regional processes and<br />

agreements, we lack a global legal instrument that lays out the procedures and responsibilities<br />

for protecting areas in the high seas or seabed area. What exists instead is a patchwork <strong>of</strong><br />

agreements and bodies that govern specific human uses, such as fishing, shipping or seabed<br />

mining, under the general umbrella <strong>of</strong> the United Nations Convention on the Law <strong>of</strong> the Sea.<br />

While the Law <strong>of</strong> the Sea Convention contains a very explicit obligation for all States to protect<br />

and preserve the marine environment, it did not provide a clear institutional arrangement to<br />

accomplish this. A global-scale agreement could support such efforts by enhancing progress<br />

across all regions and sectors, and not just in regions with the scientific, legal and technical<br />

capacity to manage large ocean areas.<br />

The United Nations has established an informal working group specifically to discuss and<br />

develop recommendations on the conservation and sustainable use <strong>of</strong> marine biological diversity<br />

in areas beyond national jurisdiction. At the Working Group’s third meeting in February 2010,<br />

governments expressed willingness to accelerate progress on protected areas.<br />

Recommendations <strong>of</strong> the Working Group have been endorsed by United Nations General<br />

Assembly resolution. To facilitate the scale <strong>of</strong> progress needed to meet the 2012 WSSD target<br />

for representative networks <strong>of</strong> marine protected areas, this informal UN Working Group will need<br />

to tackle the institutional and legal challenges.<br />

At the same time, wider reforms will be needed to ensure international and cross-sectoral<br />

cooperation and to increase capacities to sustainably and equitably manage ocean resources<br />

beyond the zones <strong>of</strong> national jurisdiction.<br />

For further information, please contact: Publications and Meetings, ZSL, Regent’s Park, <strong>London</strong> NW1 4RY, UK. anne.braae@zsl.org

MARINE PROTECTED AREAS ON THE HIGH SEAS<br />

AN INTERNATIONAL SYMPOSIUM HELD AT ZSL ON 3 AND 4 FEBRUARY 2011<br />

ABSTRACTS OF TALKS<br />

16.35–17.00 WWF´s engagement towards establishing a comprehensive network <strong>of</strong><br />

marine protected areas in the high seas<br />

Christian Neumann and Sabine Christiansen,<br />

International WWF Centre for Marine Conservation<br />

Ecosystems in areas beyond national jurisdiction are affected by a range <strong>of</strong> human activities.<br />

Fishing, and in particular bottom fishing, has been identified as the most significant impact on<br />

biodiversity and ecosystem integrity; however, shipping, pollution and the looming extraction <strong>of</strong><br />

mineral resources pose further risks. While sectoral competent authorities, such as Regional<br />

Fisheries Management Organisations (RFMOs), the International Maritime Organisation (IMO)<br />

and the International Seabed Authority (ISA), can address threats to ecosystems arising from<br />

activities falling within their regulatory mandate, only few international bodies take a crosssectoral,<br />

comprehensive approach to spatial conservation in areas beyond national jurisdiction.<br />

WWF addresses this gap by coordinating through its world-wide network an integrated local,<br />

regional and global effort to establishing <strong>MPA</strong>s in areas beyond national jurisdiction. Working<br />

on a wide range <strong>of</strong> issues, WWF engages in dialogues with governments, regional and global<br />

organisations, including scientific advisory bodies, such as International Council for the<br />

Exploration <strong>of</strong> the Sea (ICES), towards achieving comprehensive conservation in the High<br />

Seas. The presentation will provide examples <strong>of</strong> this global engagement.<br />

17.00–17.30 DISCUSSION LED BY PANEL OF SESSION II AND III SPEAKERS<br />

17.30–18.45 POSTER SESSION with cash bar<br />

18.45 End <strong>of</strong> Day One<br />

19.00–21.00 <strong>Symposium</strong> dinner for speakers and guests with tickets<br />

For further information, please contact: Publications and Meetings, ZSL, Regent’s Park, <strong>London</strong> NW1 4RY, UK. anne.braae@zsl.org

MARINE PROTECTED AREAS ON THE HIGH SEAS<br />

AN INTERNATIONAL SYMPOSIUM HELD AT ZSL ON 3 AND 4 FEBRUARY 2011<br />

ABSTRACTS OF TALKS<br />

SESSION IV: SOLUTIONS AND THE TRANSLATION OF SCIENCE INTO POLICY<br />

Chair: Kirsty Kemp (Institute <strong>of</strong> Zoology, ZSL)<br />

9.00–9.25 Minimizing fisheries displacement in <strong>of</strong>fshore <strong>MPA</strong> design<br />

Jason M. Hall-Spencer, Mariagrazia Graziano, Emma L. Jackson and Martin J.<br />

Attrill, Marine Institute, University <strong>of</strong> Plymouth, UK<br />

Fisheries closures are rapidly being developed to protect vulnerable marine ecosystems<br />

worldwide. It is possible to create lose-lose situations with the loss <strong>of</strong> good fishing grounds<br />

within fisheries closures causing displacement <strong>of</strong> effort that may increase damage to sensitive<br />

habitat types, create unintended conflicts with other uses <strong>of</strong> the seas or forcing fishermen further<br />

<strong>of</strong>fshore, increasing fuel costs and CO2 emissions. Displacement <strong>of</strong> demersal towed gear is<br />

highly likely if closures are set up in areas that are currently heavily fished with towed demersal<br />

gear and have conservation objectives designed to protect or allow the recovery <strong>of</strong> features that<br />

are vulnerable to the effects <strong>of</strong> demersal towed gear. Win-win situations are also possible;<br />

satellite monitoring <strong>of</strong> fishing vessel activity indicates that <strong>of</strong>fshore closures can work effectively<br />

with good compliance by international fleets even in remote areas. Here we show how remote<br />

fisheries closures have been designed to protect Lophelia pertusa habitat in a region <strong>of</strong> the NE<br />

Atlantic that straddles the EU fishing zone and the high seas. Scientific records, fishers’<br />

knowledge and surveillance data on fishing activity can be combined to provide a powerful tool<br />

for the design <strong>of</strong> Marine Protected Areas that minimises displacement <strong>of</strong> fishing effort.<br />

This work is funded by the EC Framework 7 project Knowledge-based Sustainable Management<br />

for Europe’s Seas (KnowSeas-226675).<br />

9.25–9.50 Understanding deep sea Vulnerable Marine Ecosystems and Fisheries in<br />

the NW Atlantic: links between productivity and biodiversity<br />

Andrew Kenny and Christopher Barrio Frojan, CEFAS, UK<br />

Over-fishing, together with climate change and other human pressures, is producing impacts <strong>of</strong><br />

unprecedented intensity and frequency on both shallow and deep-sea ecosystems, causing<br />

changes in biodiversity, structure and organisation <strong>of</strong> marine assemblages directly and indirectly.<br />

A general relationship exists between marine ecosystem productivity and biodiversity, such that<br />

increased biodiversity is <strong>of</strong>ten associated with enhanced productivity and biomass when<br />

measured at the regional scale, but when assessed at more local scales and in closed systems,<br />

patterns are found to be mainly unimodal. By contrast, analysis <strong>of</strong> certain biotic components <strong>of</strong><br />

deep-sea ecosystems has shown that functioning <strong>of</strong> these ecosystems is not only positively, but<br />

is exponentially related to biodiversity. Such results suggest that higher biodiversity in the deep<br />

sea supports higher rates <strong>of</strong> ecosystem processes and an increased efficiency with which these<br />

processes are performed. These exponential relationships support the hypothesis that mutually<br />

positive functional interactions (ecological facilitation) are much more prevalent in deep-sea<br />

ecosystems compared with coastal and shelf-sea ecosystems, and it seems likely this is<br />

associated (in part) with increased environmental stability and increased habitat structural<br />

complexity. In particular, the importance <strong>of</strong> habitat structural complexity in facilitating increased<br />

benthic productivity in the deep sea has probably been underestimated. This assertion (if<br />

proven) would have significant implications for fisheries management in the deep sea, as it<br />

highlights the importance <strong>of</strong> protecting seabed habitats in order to sustain deep-sea fisheries<br />

production compared to shallow shelf-sea ecosystems.<br />

For further information, please contact: Publications and Meetings, ZSL, Regent’s Park, <strong>London</strong> NW1 4RY, UK. anne.braae@zsl.org

MARINE PROTECTED AREAS ON THE HIGH SEAS<br />

AN INTERNATIONAL SYMPOSIUM HELD AT ZSL ON 3 AND 4 FEBRUARY 2011<br />

ABSTRACTS OF TALKS<br />

We propose to present a relatively crude unified comparative analysis <strong>of</strong> deep-sea and shelf-sea<br />

ecosystems to evaluate biological, structural and functional benthic diversity in relation to<br />

fisheries management approaches.<br />

9.50–10.15 The application <strong>of</strong> habitat mapping and predictive modelling in high seas<br />

<strong>MPA</strong> network design: lessons from the UK deep-sea <strong>MPA</strong> project<br />

Kerry Howell 1 , Jaime Davies 1 , Heather Stewart 2 , Colin Jacons 3 , Inés Pulido<br />

Endrino 1 , Sophie Mowles 1 , Andy Foggo 1 , Neil Golding 4 , Charlotte Marshall 1<br />

and Bhavani Narayanaswamy 5<br />

1 Marine Institute, University <strong>of</strong> Plymouth, UK, 2 British Geological Survey, UK,<br />

3 National Oceanography Centre, Southampton, UK, 4 Joint Nature<br />

Conservation Committee, UK, 5 Scottish Association for Marine Science, UK<br />

Internationally there is political momentum to establish networks <strong>of</strong> marine protected areas<br />

(<strong>MPA</strong>s) in the high seas for the conservation <strong>of</strong> biodiversity. Practical implementation <strong>of</strong> such<br />

networks requires at its base biologically meaningful maps on which to base the complex task<br />

that is <strong>MPA</strong> network design. Species and habitat distribution data in the deep-sea and high seas<br />

are sparse, therefore how do we produce maps <strong>of</strong> use with the data that are available? We<br />

present an example from the UK deep-sea <strong>MPA</strong> project and illustrate its application to the highseas.<br />

Broad-scale biologically meaningful maps are produced using a three level classification<br />

system comprising (biogeography, depth, and substrate) that captures what is known about the<br />

variation in benthic biological communities in the UK deep-sea. As substrate maps are not<br />

available for much <strong>of</strong> the high seas, the use <strong>of</strong> geomophological surrogates and their biological<br />

meaning is discussed; as well as the use <strong>of</strong> additional surrogates that may be required in order<br />

to produce globally biologically meaningful maps for high seas areas. Predictive species<br />

distribution modelling is a natural extension <strong>of</strong> habitat mapping in that it effectively uses<br />

integrated maps <strong>of</strong> environmental variables (‘habitat’ maps) to predict the distribution <strong>of</strong> species<br />

<strong>of</strong> interest. These approaches can also be applied to biological ‘habitats’, such as cold water<br />

coral reefs, sponge aggregations and coral gardens. Fine-scale maps <strong>of</strong> the distribution <strong>of</strong><br />

vulnerable marine ecosystems (VMEs) are produced using predictive modelling approaches<br />

(Maxent) and the importance <strong>of</strong> habitat vs species level predictions at a fine scale is illustrated<br />

using the example <strong>of</strong> Lophelia pertusa reef on Hatton Bank and George Bligh Bank (NE<br />

Atlantic). The application <strong>of</strong> predictive modelling approaches in the wider high seas is<br />

discussed.<br />

10.15–10.45 POSTER SESSION (TEA/COFFEE)<br />

For further information, please contact: Publications and Meetings, ZSL, Regent’s Park, <strong>London</strong> NW1 4RY, UK. anne.braae@zsl.org

MARINE PROTECTED AREAS ON THE HIGH SEAS<br />

AN INTERNATIONAL SYMPOSIUM HELD AT ZSL ON 3 AND 4 FEBRUARY 2011<br />

ABSTRACTS OF TALKS<br />

SESSION IV (cont): SOLUTIONS AND THE TRANSLATION OF SCIENCE INTO POLICY<br />

Chair: Alex D. Rogers (University <strong>of</strong> Oxford)<br />

10.45–11.10 The South Orkney Islands Southern Shelf Marine Protected Area<br />

Susie Grant, Phil Trathan, Janet Silk and J. Tratolos, British Antarctic Survey,<br />

Cambridge, UK<br />

The South Orkney Islands Southern Shelf Marine Protected Area was agreed by the<br />

Commission for the Conservation <strong>of</strong> Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR) in November<br />

2009. It is the world’s first marine protected area (<strong>MPA</strong>) located entirely within the ‘High Seas’.<br />

The <strong>MPA</strong> covers a large area <strong>of</strong> the Southern Ocean, south <strong>of</strong> the South Orkney Islands. The<br />

<strong>MPA</strong> was the result <strong>of</strong> four years <strong>of</strong> development work. It is just less than 94,000 square<br />

kilometers, which is more than four times the size <strong>of</strong> Wales. No fishing activities and no<br />

discharge or refuse disposal from fishing vessels are allowed in the area, which will allow<br />

scientists to better monitor the effects <strong>of</strong> human activities and climate change on the Southern<br />

Ocean.<br />

The marine protected area for the South Orkneys includes important sections <strong>of</strong> an<br />

oceanographic feature known as the Weddell Front, which marks the northern limit <strong>of</strong> waters<br />

characteristic <strong>of</strong> the Weddell Sea and the southern limit <strong>of</strong> the Weddell Scotia Confluence. The<br />

Weddell Scotia Confluence is a key habitat for Antarctic krill, one <strong>of</strong> the main species harvested<br />

in the Antarctic and a key focus for CCAMLR. The <strong>MPA</strong> also includes important foraging areas<br />

for Adélie penguins that breed at the South Orkney Islands, and important submarine shelf areas<br />

and seamounts, including areas that have recently been shown to have high biodiversity.<br />

The South Orkneys <strong>MPA</strong> will thus better conserve marine biodiversity and forms the first link in a<br />

representative system <strong>of</strong> marine protected areas for the Antarctic. Planning to develop the other<br />

parts <strong>of</strong> the system are under active consideration by CCAMLR scientists. The network will help<br />

conserve important ecosystem processes, vulnerable areas, and create reference sites that can<br />

be used to make scientific comparisons between fished areas and no-take areas. Such<br />

networks will become increasingly important as climate change impacts become increasingly<br />

evident in the Antarctic in the future.<br />

11.10–11.35 BirdLife’s marine Important Bird Areas Programme – providing the<br />

science behind candidate <strong>MPA</strong>s for seabirds<br />

Ben Lascelles and Phillip Taylor, BirdLife International Global Seabird<br />

Programme, UK<br />

The BirdLife Important Bird Area (IBA) programme has been used to provide scientific<br />

justification for the selection <strong>of</strong> priority sites for conservation for over 25 years. In recent years it<br />

has been adapted and extended to the marine environment, including the high seas.<br />

This talk will present an outline <strong>of</strong> BirdLife’s marine IBA Programme and highlight our work with<br />

the scientific community to develop several datasets to help determine the location <strong>of</strong> priority<br />

sites for seabird conservation. It will focus on the Global Procellariiform Tracking Database and<br />

explain the innovative analysis techniques we have been using to identify priority sites using the<br />

data held there. The analysis includes developing measures <strong>of</strong> regularity and intensity <strong>of</strong> use <strong>of</strong><br />

For further information, please contact: Publications and Meetings, ZSL, Regent’s Park, <strong>London</strong> NW1 4RY, UK. anne.braae@zsl.org

MARINE PROTECTED AREAS ON THE HIGH SEAS<br />

AN INTERNATIONAL SYMPOSIUM HELD AT ZSL ON 3 AND 4 FEBRUARY 2011<br />

ABSTRACTS OF TALKS<br />

an area, concepts that we have found are readily understandable in policy arenas, such as the<br />

EU Birds Directive and the Convention on Biological Diversity.<br />

Having described the methods we use to identify a site we will explain how we go about<br />

describing it using a combination <strong>of</strong> habitat modelling and other techniques. The overall aim is<br />

to assess why a particular site is located where it is, and determining what the underlying<br />

important environmental variables are. This can provide vital information for future management<br />

and allows us to determine whether fixed spatial or mobile/temporal <strong>MPA</strong>s might be appropriate.<br />

We will touch on what the appropriate monitoring and management <strong>of</strong> such areas is likely to<br />

involve. This will to some degree depend on the species involved, but will not necessarily mean<br />

closure or no-take zones, but it is likely to include enforcement <strong>of</strong> bycatch mitigation measures,<br />

assessment <strong>of</strong> key prey species, oil spill management plans etc.<br />

Finally, we will highlight how BirdLife plans to develop this work in the coming years, and how<br />

we hope to link to relevant policy mechanisms and improve the sustainable management <strong>of</strong> the<br />

oceans.<br />

11.35–12.00 Chemosynthetic ecosystems: Understanding what’s at risk and tools for<br />

effective management<br />

Cindy Lee Van Dover 1 , Craig R. Smith 2 , Laurent Godet 3 and the Dinard<br />

Workshop Participants<br />

1 Marine Laboratory, Nicholas School <strong>of</strong> the Environment, Duke University,<br />

USA, 2 Department <strong>of</strong> Oceanography, University <strong>of</strong> Hawaii at Manoa, Honolulu,<br />

USA, 3 Laboratoire Géolittomer (UMR 6554 LETG), Université de Nantes,<br />

France<br />

Discovery <strong>of</strong> chemosynthetic ecosystems in the 1970s changed the way we think about<br />

dynamic processes <strong>of</strong> the Earth and Ocean and about the extremes at which life can exist on<br />

this planet and elsewhere in the universe. Chemosynthetic ecosystems support organisms that<br />

rely on microbial primary production based on energy from chemical reactions, i.e., organisms<br />

with exquisite biochemical, physiological, morphological, and behavioural adaptations to their<br />

environment. Since their discovery, chemosynthetic ecosystems have served as living libraries<br />

for science stakeholders, and scientific literature on these ecosystems is abundant, <strong>of</strong> high<br />

impact, and expanding exponentially. In addition to their biodiversity and ecosystem services,<br />

a major conservation stake <strong>of</strong> chemosynthetic ecosystems is thus a type <strong>of</strong> service seldom<br />

reported in conservation studies: their knowledge value. The potential for environmental<br />

impacts resulting from scientific research at hydrothermal vents motivated the InterRidge<br />

Statement <strong>of</strong> Commitment to Responsible Research Practices at Hydrothermal Vents. While<br />

this Statement reminds scientists <strong>of</strong> their responsibilities as stewards <strong>of</strong> the environment they<br />

study, management areas that include conservation and scientific research objectives are likely<br />

more effective stewardship tools. A greater level <strong>of</strong> threat to chemosynthetic ecosystems is<br />

posed by industries that seek to mine mineral deposits at vents or engage in oil and gas<br />

extraction near seeps, and by the extensive collateral impacts <strong>of</strong> bottom fishing. Oil extraction<br />

and bottom trawling already affect large areas <strong>of</strong> potential seep habitat, and licensing activity<br />

for mining exploration around hydrothermal vent systems is underway. These activities impose<br />

urgency to establishment <strong>of</strong> guidelines for networks <strong>of</strong> managed chemosynthetic areas in<br />

regions within and beyond national jurisdiction. We present a set <strong>of</strong> design principles<br />

formulated to safeguard biodiversity, ecosystem function, and the knowledge value <strong>of</strong><br />

chemosynthetic ecosystems within the framework <strong>of</strong> exploitation <strong>of</strong> seabed resources. The<br />

patchy distribution <strong>of</strong> chemosynthetic ecosystems in space and time requires coarse- to fine-<br />

For further information, please contact: Publications and Meetings, ZSL, Regent’s Park, <strong>London</strong> NW1 4RY, UK. anne.braae@zsl.org

MARINE PROTECTED AREAS ON THE HIGH SEAS<br />

AN INTERNATIONAL SYMPOSIUM HELD AT ZSL ON 3 AND 4 FEBRUARY 2011<br />

ABSTRACTS OF TALKS<br />

filter spatial management strategies, depending on where habitat patch distributions fall along a<br />

gradient from semi-continuous to highly dispersed across a bioregion. Because the distribution<br />

and biogeography <strong>of</strong> chemosynthetic habitats in the deep sea are still very poorly known,<br />

management plans to maintain ecological, scientific, and commercial values must be adaptive<br />

to incorporate increasing ecosystem knowledge and demand trust and collaboration among all<br />

stakeholders.<br />

12.00–12.30 DISCUSSION LED BY PANEL OF SESSION IV MORNING SPEAKERS<br />

12.30–13.30 LUNCH<br />

SESSION IV (cont): SOLUTIONS AND THE TRANSLATION OF SCIENCE INTO POLICY<br />

Chair: Matthew Gollock (International Marine and Freshwater Conservation Programme, ZSL)<br />

13.30–13.55 The establishment <strong>of</strong> the OSPAR network <strong>of</strong> <strong>MPA</strong>s including in the High<br />

Seas <strong>of</strong> the North East Atlantic<br />

Henning von Nordheim and Tim Packeiser, German Federal Agency for Nature<br />

Conservation, Germany<br />

The ministers for the environment <strong>of</strong> the Contracting Parties to the Oslo-Paris (OSPAR) and<br />

Helsinki (HELCOM) Conventions agreed in 2003 during their joint meeting in Bremen, Germany,<br />

to establish by 2010 an ecologically coherent network <strong>of</strong> well-managed Marine Protected Areas<br />

(<strong>MPA</strong>s) in the Baltic Sea and the North-East Atlantic. This commitment is seen as a significant<br />

and coordinated regional contribution to the agreement <strong>of</strong> the World Summit <strong>of</strong> Sustainable<br />

Development/WSSD in 2002 in Johannesburg, South Africa, to establish a worldwide network <strong>of</strong><br />

protected areas by 2012, including in the marine realm.<br />

Until the Ministerial Meeting <strong>of</strong> the OSPAR Contracting Parties in September 2010 (Bergen,<br />

Norway) the OSPAR Network <strong>of</strong> <strong>MPA</strong>s consisted <strong>of</strong> 159 sites collectively covering 147 322 km²<br />

in the North-East Atlantic.<br />

With the aim to extend the Network <strong>of</strong> <strong>MPA</strong>s to the Wider Atlantic Region which makes up about<br />

40% <strong>of</strong> the OSPAR maritime area, OSPAR has over the past years assumed a pioneering role<br />

in the global process to establish <strong>MPA</strong>s in Areas beyond National Jurisdiction (ABNJ). With<br />

substantial support <strong>of</strong> the scientific community, a number <strong>of</strong> ecologically and biologically<br />

significant areas that are representative for the diverse open-ocean and deep-sea ecosystems in<br />

the North-East Atlantic have been identified. The resulting proposals for <strong>MPA</strong>s in ABNJ,<br />

however, remained subject to agreement by OSPAR Contracting Parties on a number <strong>of</strong><br />

complex political and legal issues, in particular in conjunction with recent submissions by some<br />

Contracting Parties for an extended continental shelf within the OSPAR maritime area.<br />

As a conclusion <strong>of</strong> a longsome process <strong>of</strong> negotiations, the OSPAR Ministers finally agreed on<br />

24 September 2010 on the establishment <strong>of</strong> a network <strong>of</strong> additional six Marine Protected Areas<br />

in the High Seas <strong>of</strong> the North-East Atlantic. These <strong>MPA</strong>s cover a total area <strong>of</strong> 285 000 km² and<br />

protect a series <strong>of</strong> seamounts and sections <strong>of</strong> the Mid-Atlantic Ridge (MAR) hosting a range <strong>of</strong><br />

For further information, please contact: Publications and Meetings, ZSL, Regent’s Park, <strong>London</strong> NW1 4RY, UK. anne.braae@zsl.org

MARINE PROTECTED AREAS ON THE HIGH SEAS<br />

AN INTERNATIONAL SYMPOSIUM HELD AT ZSL ON 3 AND 4 FEBRUARY 2011<br />

ABSTRACTS OF TALKS<br />

vulnerable deep-sea habitats and species. While two <strong>of</strong> these <strong>MPA</strong>s are situated entirely in<br />

Areas beyond National Jurisdiction, the four other <strong>MPA</strong>s have been established in collaboration<br />

with Portugal as the seabed in these areas is subject to the submission by Portugal for an<br />

extended continental shelf.<br />

This ground-breaking decision by OSPAR Ministers on ocean governance has extended the<br />

coverage <strong>of</strong> the OSPAR Network <strong>of</strong> <strong>MPA</strong>s to about 427 000 km² or 3.1% <strong>of</strong> the North-East<br />

Atlantic, and it might well set a precedent for other regions working towards the WSSD goal <strong>of</strong><br />

implementing representative systems <strong>of</strong> <strong>MPA</strong>s by 2012.<br />

13.55–14.20 Bottom fisheries closures introduced by Atlantic RFMOs as elements <strong>of</strong><br />

new regulatory frameworks to facilitate sustainable resource utilization<br />

and conserve biodiversity<br />

Odd Aksel Bergstad, Institute <strong>of</strong> Marine Research, Norway<br />

During the past decade, efforts to regulate Atlantic fisheries for deepwater resources in areas<br />

beyond national jurisdiction increased significantly. Conservation <strong>of</strong> vulnerable benthic<br />

invertebrate species and fish resources were key aims, maintaining also a potential for<br />

continued or future sustainable resource utilization.<br />

Governments and relevant international fisheries management organizations introduced<br />

comprehensive classical fishery management measures, including closure <strong>of</strong> sub-areas to<br />

certain fisheries and practices. Background and principles underlying current regulations are<br />

explained and discussed, including the interaction between science and management, and<br />

between management organizations with complimentary authorities and roles.<br />

A need for an analysis <strong>of</strong> the effectiveness <strong>of</strong> the new regulatory framework is recognised. Such<br />

a review would have to consider the relative impacts <strong>of</strong> new regulations and other factors, such<br />

as rising fuel costs, reduced subsidies, and enhanced fishing opportunities elsewhere. A<br />

provisional evaluation <strong>of</strong> current fishery trends in view <strong>of</strong> recent regulatory efforts suggests that<br />

the incentive to fish unsustainably on the high seas is significantly reduced. <strong>MPA</strong>s introduced by<br />

regional fisheries management organizations constituted just one <strong>of</strong> several regulatory elements<br />

together creating a new environment for deepwater fisheries on the high seas.<br />

14.20–14.45 Data gaps and Quiet <strong>MPA</strong>s: use <strong>of</strong> passive acoustic monitoring to detect<br />

presence <strong>of</strong> whales and dolphins and to quantify human use<br />

Rob Williams, Erin Ashe, Erich Hoyt and Kristin Kaschner<br />

University <strong>of</strong> St Andrews, UK<br />

The <strong>MPA</strong> siting algorithms used in conservation planning s<strong>of</strong>tware have a well-known tendency<br />

to gravitate toward data-rich areas. This has important implications for marine biodiversity<br />

protection, where the high cost <strong>of</strong> ship-board surveys <strong>of</strong>ten results in patchy data. When spatial<br />

bias in sampling is ignored, selection <strong>of</strong> priority areas will be biased toward locations <strong>of</strong> sampling<br />

points. We recently completed a gap analysis that compiled and mapped density estimates for<br />

cetaceans (whales, dolphins and porpoises) in the North Pacific from line transect data. We<br />

found that much <strong>of</strong> the North Pacific beyond the range <strong>of</strong> countries' EEZs was unsurveyed.<br />

Marxan best practice requires filling in those data gaps, but there is little guidance for cases<br />

where ‘gaps’ constitute large fractions <strong>of</strong> the Earth’s surface. We see two complementary<br />

options. One <strong>of</strong> us (KK) has pioneered methods to predict cetacean distribution based on<br />

habitat suitability models. Another (RW) has developed methods for filling in data gaps with<br />

For further information, please contact: Publications and Meetings, ZSL, Regent’s Park, <strong>London</strong> NW1 4RY, UK. anne.braae@zsl.org

MARINE PROTECTED AREAS ON THE HIGH SEAS<br />

AN INTERNATIONAL SYMPOSIUM HELD AT ZSL ON 3 AND 4 FEBRUARY 2011<br />

ABSTRACTS OF TALKS<br />

relatively low-cost field work, through platform-<strong>of</strong>-opportunity surveys on the high seas, coastal,<br />

small-boat surveys and recently through autonomous passive acoustic monitoring on continental<br />

shelf waters <strong>of</strong> British Columbia, Canada. Acoustic monitoring can detect the presence <strong>of</strong><br />

vocalizing cetaceans in poorly surveyed areas and seasons, while simultaneously measuring<br />

ambient noise levels, which constitute an important human-use layer for measuring habitat<br />

quality for acoustically sensitive species. Acoustic research now allows estimation <strong>of</strong> acoustic<br />

space that whales lose from chronic shipping and seismic survey noise. Some policy<br />

frameworks, such as Canada’s Species at Risk Act and possibly the EU Habitats Directive, may<br />

allow this science to lead to mitigation through <strong>MPA</strong> planning. Our vision is for a network <strong>of</strong><br />

Quiet <strong>MPA</strong>s. Our recommended approach would (1) map data and gaps, (2) make predictions<br />

about species presence based on habitat suitability, and (3) test those predictions on a randomly<br />

chosen subset <strong>of</strong> regions and species using field data collected from surveys and passive<br />

acoustic monitoring. Based on our experience on the continental shelf, we see our approach as<br />

one that could be transported to the high seas. We cannot consider <strong>MPA</strong>s to be wholly<br />

protected if the management plans ignore acoustic elements, given the importance <strong>of</strong> sound as<br />

the primary modality by which many marine species obtain information about their environments.<br />

14.45–15.15 POSTER SESSION (TEA/COFFEE)<br />

SESSION IV (cont): SOLUTIONS AND THE TRANSLATION OF SCIENCE INTO POLICY<br />

Chair: Kirsty Kemp (Institute <strong>of</strong> Zoology, ZSL)<br />

15.15–15.40 Seamounts are hotspots <strong>of</strong> pelagic biodiversity in the open oceans and<br />

areas <strong>of</strong> special interest for management <strong>of</strong> marine pelagic predators<br />

Telmo Morato 1 , Simon D. Hoyle 2 , Valerie Allain 2 and Simon J. Nicol 2 ,<br />

1 Universidade dos Açores, Portugal, 2 Oceanic Fisheries Program, Secretariat<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Pacific Community, Noumea, New Caledonia<br />

The identification <strong>of</strong> biodiversity hotspots and their management for conservation have been<br />

hypothesized as effective ways to protect many species. There has been a significant effort to<br />

identify and map these areas at a global scale, but the coarse resolution <strong>of</strong> most datasets<br />

masks the small-scale patterns associated with coastal habitats or seamounts. We used tuna<br />

longline observer data to investigate the role <strong>of</strong> seamounts in aggregating large pelagic<br />

biodiversity and to identify which pelagic species are associated with seamounts. Our analysis<br />

indicates that seamounts are hotspots <strong>of</strong> pelagic biodiversity. Higher species richness was<br />

detected in association with seamounts than with coastal or oceanic areas. Seamounts were<br />

found to have higher species diversity within 30–40 km <strong>of</strong> the summit, whereas for sets close to<br />

coastal habitat the diversity was lower and fairly constant with distance. Higher probability <strong>of</strong><br />

capture and higher number <strong>of</strong> fish caught were detected for some shark, billfish, tuna, and<br />

other by-catch species. Our study supports hypotheses that seamounts may be areas <strong>of</strong><br />

special interest for management for marine pelagic predators. We have also evaluated the<br />

existence <strong>of</strong> an association between seamounts and tuna longline fisheries at the ocean basin<br />

scale to identify significant seamounts for tuna in the western and central Pacific Ocean. Our<br />

study identified many seamounts throughout the western Pacific Ocean that may act as<br />

important aggregating points for tuna species. This indicates that management <strong>of</strong> seamounts<br />

For further information, please contact: Publications and Meetings, ZSL, Regent’s Park, <strong>London</strong> NW1 4RY, UK. anne.braae@zsl.org

MARINE PROTECTED AREAS ON THE HIGH SEAS<br />

AN INTERNATIONAL SYMPOSIUM HELD AT ZSL ON 3 AND 4 FEBRUARY 2011<br />

ABSTRACTS OF TALKS<br />

is important Pacific-wide, but management approaches must take account <strong>of</strong> local conditions.<br />

Management <strong>of</strong> tuna and biodiversity resources in the region would benefit from considering<br />

such effects.<br />

Morato, T., S.D. Hoyle, V. Allain, and S.J. Nicol (2010) Seamounts are hotspots <strong>of</strong> pelagic biodiversity in the open ocean.<br />

Proceedings <strong>of</strong> the National Academy <strong>of</strong> Science USA 107(21): 9707-9711. doi:10.1073/pnas.0910290107.<br />

http://www.pnas.org/content/early/2010/05/05/0910290107.full.pdf+html<br />

Morato, T., S.D. Hoyle, V. Allain, S.J. Nicol (2010) Tuna longline fishing around West and Central Pacific seamounts. PLoS<br />

ONE 5(12): e14453. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0014453.<br />

15.40–16.05 Effects <strong>of</strong> high seas <strong>MPA</strong>s on commercial fisheries: Examples from the<br />

Atlantic and Indian Oceans’ tuna fleets<br />

Emmanuel Chassot 1 , Edgar Torres 1 , David M. Kaplan 1 , Daniel Gaertner 1 ,<br />

Misael Morales 1 , Alicia Delgado 2 , Javier Ariz 2 , 1 IRD, Centre de Recherche<br />

Halieutique, UMR 212 EME (IRD/Ifremer/U Montpellier II), France, 2 IEO,<br />

Centro Oceanográfico de Canarias, Canary Islands, Spain<br />

The impact <strong>of</strong> high seas <strong>MPA</strong>s on commercial fishing fleets is a central question in the debate<br />

about the efficacy and utility <strong>of</strong> such measures for managing pelagic ecosystems. There are at<br />

least two well-studied cases <strong>of</strong> spatial closures that impacted high-seas tropical tuna fisheries.<br />

In the eastern tropical Atlantic, a partial temporal closure was implemented in 1996 to reduce the<br />

catch <strong>of</strong> juvenile tropical tuna species. This closure did reduce overall catch <strong>of</strong> juveniles by<br />

European fleets, but there was a significant displacement <strong>of</strong> fishing effort to non-closure areas<br />

and non-observance <strong>of</strong> the closure by certain fleets led to its virtual abandonment in 2005. In<br />

the Indian Ocean, the Somali EEZ has been <strong>of</strong>f limits for fishing since 2004 and pirate activity<br />

has significantly reduced fishing activity in a large area around Somalia since 2007. Tuna<br />

catches in this zone historically represent no less than 25% <strong>of</strong> the total Indian Ocean catch by<br />

European fleets and are dominated by small, <strong>of</strong>ten immature, individuals caught <strong>of</strong>f artificial fish<br />

aggregation devices (FADs). Fishing activity in the area has been significantly reduced by this<br />

‘closure’, particularly in 2008 when pirate activity was at its peak and before military intervention<br />

reduced risk from piracy, but the European fishing fleet has been able to recoup most losses in<br />

other areas <strong>of</strong> the Indian Ocean and a number <strong>of</strong> fishing boats have switched to the Atlantic<br />

Ocean, <strong>of</strong>ten fishing in areas previously in the eastern Atlantic temporal closure. These<br />

examples demonstrate the potential <strong>of</strong> reducing juvenile catches with large, well-placed<br />

protected areas, but also the complexity <strong>of</strong> reactions by the fishing industry to closures that can<br />

reduce or eliminate any benefits.<br />

16.05–16.30 Options for fisheries-independent monitoring in pelagic <strong>MPA</strong>s<br />

Matthew Gollock and Heather Koldeway, Conservation Programmes, ZSL, UK<br />

On 1 April 2010, the British Government announced designation <strong>of</strong> the British Indian Ocean<br />

Territory or Chagos Archipelago (Chagos/BIOT) as the world’s largest marine protected area<br />

(<strong>MPA</strong>). This near pristine ocean ecosystem now represents 16% <strong>of</strong> the world’s fully protected<br />

coral reef, 60% <strong>of</strong> the world’s no-take protected areas and an uncontaminated reference site for<br />

ecological studies. While the benefits <strong>of</strong> <strong>MPA</strong>s for coral-reef dwelling species are established,<br />

there is uncertainty about their effects on pelagic migratory species such as tuna, tuna-like<br />

species and elasmobranchs. Further, the majority <strong>of</strong> available data on pelagic species is<br />

fisheries-based – primarily from long-line and purse seine tuna fisheries. Consequently, we<br />

need to assess available techniques, modelling approaches and emerging technologies that<br />

For further information, please contact: Publications and Meetings, ZSL, Regent’s Park, <strong>London</strong> NW1 4RY, UK. anne.braae@zsl.org

MARINE PROTECTED AREAS ON THE HIGH SEAS<br />

AN INTERNATIONAL SYMPOSIUM HELD AT ZSL ON 3 AND 4 FEBRUARY 2011<br />

ABSTRACTS OF TALKS<br />

could be applied to monitor these large pelagic predators. Additional considerations include the<br />

lack <strong>of</strong> baseline data, available resources and the remote nature <strong>of</strong> Chagos/BIOT.<br />

On the 12–13 July 2010 a multi-stakeholder workshop was held at ZSL to address, and<br />

prioritise, the future options for management and research in the Chagos/BIOT <strong>MPA</strong>, however, it<br />

was also an opportunity to address monitoring options for pelagic species in the open ocean<br />

generally. Expert opinion was gathered in relation to what methods would be available, what<br />

time scale they should be used over and how they could work complementarily. After the<br />

workshop, more focussed research was carried out in the form <strong>of</strong> an intra-ZSL meeting on the<br />

subject, and a literature search carried out by MSc students.<br />

This presentation will review existing and potential methodologies and discuss what might be<br />

most appropriate for researching the response <strong>of</strong> pelagic species to the new <strong>MPA</strong>. The authors<br />

would greatly appreciate comments and input on this review.<br />

16.30–17.30 DISCUSSION LED BY PANEL OF SESSION IV AFTERNOON SPEAKERS<br />

17.30 End <strong>of</strong> <strong>Symposium</strong><br />

For further information, please contact: Publications and Meetings, ZSL, Regent’s Park, <strong>London</strong> NW1 4RY, UK. anne.braae@zsl.org

MARINE PROTECTED AREAS ON THE HIGH SEAS<br />

A TWO-DAY INTERNATIONAL SYMPOSIUM HELD AT ZSL ON 3 AND 4 FEBRUARY 2011<br />

POSTER ABSTRACTS<br />

MARINE PROTECTED AREAS ON THE HIGH SEAS<br />

3 AND 4 FEBRUARY 2011 — SYMPOSIUM<br />

RESEARCH POSTERS PRESENTED<br />

Evaluating the effectiveness <strong>of</strong> <strong>MPA</strong>s in the open ocean: how do changes in fishing fleet<br />

dynamics impact upon conservation objectives?<br />

Davies, T.<br />

Imperial College <strong>London</strong>, UK. Email: timothy.davies08@imperial.ac.uk<br />

No-take <strong>MPA</strong>s intentionally exclude fishing activity, causing fleet dynamics to change as fishers<br />

inevitably respond to the closure <strong>of</strong> their fishing grounds. It has been argued that in the open<br />

ocean, displacement <strong>of</strong> fishing effort has the potential to diminish the conservation benefits <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>MPA</strong>s, with fishing pressure continuing to impact upon populations <strong>of</strong> highly migratory species<br />

as they move outside <strong>of</strong> reserve boundaries. An additional threat is the persistence <strong>of</strong> illegal<br />

fishing within a closed area, which may increase if fishers perceive improved fishing<br />

opportunities within an <strong>MPA</strong>.<br />

My research aims to model the response <strong>of</strong> fishing fleets to a protected area established in an<br />

open ocean system, in order to explore the effectiveness <strong>of</strong> area-based management in<br />

conserving highly mobile, pelagic species. Models representing tuna fleets and pelagic<br />

species <strong>of</strong> the Western Indian Ocean will simulate a system that contains a protected area<br />

based on the recently established Chagos <strong>MPA</strong>. In addition to the current <strong>MPA</strong> fixed area<br />

design, a number <strong>of</strong> alternative reserve configurations will also be evaluated against a set <strong>of</strong><br />

holistic conservation objectives (rather than narrow objectives related to fisheries<br />

management).<br />

The principal focus <strong>of</strong> the project is to construct realistic models <strong>of</strong> fleet dynamics, which<br />

account for the social, cultural, institutional and economic drivers <strong>of</strong> fisher behaviour, for both<br />

the legal and illegal tuna fleets operating in the Western Indian Ocean. This will involve direct<br />

interviews with tuna fishermen, analysis <strong>of</strong> fisheries data and review <strong>of</strong> historical illegal activity<br />

within British Indian Ocean Territory. Models will be used to predict the threat <strong>of</strong> illegal fishing<br />

within the <strong>MPA</strong>, as well as the impact <strong>of</strong> effort displacement on populations <strong>of</strong> highly migratory<br />

species.<br />

This poster describes my early findings, including a short literature review <strong>of</strong> the utility <strong>of</strong><br />

pelagic <strong>MPA</strong>s based on the Chagos <strong>MPA</strong> public consultation.<br />

High seas deep-sea fisheries in an ecosystem context: the South-West Indian Ocean<br />

Ridge project<br />

Rogers, A.D. 1 , Boersch-Supan, P. 1,2 and Kemp, K. 3<br />

1 University <strong>of</strong> Oxford, UK, 2 Pelagic Ecology Research Group, Scottish Oceans Institute,<br />

University <strong>of</strong> St Andrews, Fife, UK, 3 Institute <strong>of</strong> Zoology, <strong>Zoological</strong> <strong>Society</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>London</strong>, UK.<br />

Email: alex.rogers@zoo.ox.ac.uk<br />

The ecology <strong>of</strong> seamounts <strong>of</strong> the Indian Ocean is almost unstudied. However, exploitation <strong>of</strong><br />

fisheries resources associated with seamounts in the region has taken place at least since the<br />

early 1980s. The South West Indian Ocean Ridge (SWIOR) is a range <strong>of</strong> seamounts in the<br />

high seas that were subject to a major boom-bust fishery for orange roughy in the early 1990s<br />

and are still subject to deep-sea bottom fishing. To date the management <strong>of</strong> the deep-sea<br />

For further information, please contact Scientific Publications and Meetings, ZSL, Regent’s Park, <strong>London</strong> NW1 4RY, UK. anne.braae@zsl.org

MARINE PROTECTED AREAS ON THE HIGH SEAS<br />

A TWO-DAY INTERNATIONAL SYMPOSIUM HELD AT ZSL ON 3 AND 4 FEBRUARY 2011<br />

POSTER ABSTRACTS<br />

bottom fisheries on the SWIOR has been undertaken by industry and for reasons <strong>of</strong><br />

commercial sensitivity little information is available publicly on fishing activities or stock status.<br />

Delays in the initiation <strong>of</strong> a regional fisheries management organisation, the South Indian<br />

Ocean Fisheries Agreement (SIOFA), have led to the voluntary designation <strong>of</strong> protected areas<br />

by the fishing industry in the region. However, there is little understanding <strong>of</strong> what is driving the<br />

production <strong>of</strong> these ecosystems, what the status is <strong>of</strong> targeted and non-targeted fish<br />

populations and whether voluntary management measures have been effective in protecting<br />

vulnerable marine ecosystems.<br />

We describe the development <strong>of</strong> a new project aimed at furnishing fisheries and environmental<br />

managers in the southern Indian Ocean with data on the ecosystems <strong>of</strong> the SWIOR. The<br />

project, funded by the GEF and implemented by UNDP / IUCN, has undertaken a cruise to<br />

investigate the pelagic biology <strong>of</strong> the SWIOR. Data were collected on biological oceanography,<br />

pelagic communities and aquatic predators (birds). Results indicate that seamount fisheries<br />

may be driven by trapping <strong>of</strong> migrating mesopelagic zooplankton and micronekton<br />

communities. Furthermore, important new data on the distribution <strong>of</strong> deep-water pelagic<br />

communities, including both new records for the region and new species <strong>of</strong> organisms have<br />

been collected. In 2011 a further cruise will be undertaken to survey and sample benthic<br />

ecosystems <strong>of</strong> the seamounts both within and outside <strong>of</strong> voluntary benthic protected areas.<br />

The project is the result <strong>of</strong> international collaboration between scientists, intergovernmental<br />

organisations and the fishing industry. The implications <strong>of</strong> the project for high seas fisheries<br />

management, <strong>MPA</strong> designation within the region and capacity building are discussed.<br />

Preliminary proposal <strong>of</strong> marine areas in the High Seas <strong>of</strong> the SW Atlantic to be<br />

considered for protection<br />

Portela, J. 1 , Acosta, J. 2 , Cristobo, J. 4 , Parra, S. 3 , Muñoz, A. 5 , del Río, J.L. 1 , Tel, E. 1 and<br />

Patrocinio, T. 1<br />

1 Instituto Español de Oceanografía, Centro Oceanográfico de Vigo, Spain, 2 Instituto Español<br />

de Oceanografía, Sede Central de Madrid, Spain, 3 Instituto Español de Oceanografía, Centro<br />

Oceanográfico de A Coruña, Spain, 4 Instituto Español de Oceanografía, Centro Oceanográfico<br />

de Gijón, Spain, 5 Grupo Multidisciplinar de Cartografiado (TRAGSATEC-SGM), Spain.<br />

Email: julio.portela@vi.ieo.es<br />

This study examines ongoing concerns about the effects <strong>of</strong> bottom trawling on benthic<br />

Vulnerable Marine Ecosystems (VME) on the High Seas <strong>of</strong> the Southwest Atlantic, and<br />

explores the proposal <strong>of</strong> marine areas to be considered for protection in the zone. Currently,<br />

this region is the only significant area for High Seas fisheries not covered by a Regional<br />