High Schools: Size Does Matter - The College of Education - The ...

High Schools: Size Does Matter - The College of Education - The ...

High Schools: Size Does Matter - The College of Education - The ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Issue Brief<br />

March 2004<br />

Volume 1, Issue 1<br />

Study <strong>of</strong> <strong>High</strong><br />

School<br />

Restructuring<br />

Inside This Issue<br />

Findings on school size:<br />

Achievement<br />

Equity<br />

Affiliation<br />

Dropout<br />

Postsecondary<br />

preparation<br />

Curriculum quality<br />

Cost<br />

Optimal <strong>Size</strong><br />

Effective Small <strong>Schools</strong><br />

<strong>The</strong> University <strong>of</strong> Texas<br />

Dept. <strong>of</strong> <strong>Education</strong>al<br />

Administration<br />

1 University Station<br />

D5400<br />

Austin TX 78712<br />

512-475-8569<br />

www.edb.utexas.edu/hsns<br />

<strong>High</strong> <strong>Schools</strong>:<br />

<strong>Size</strong> <strong>Does</strong> <strong>Matter</strong><br />

by<br />

Thu Suong Thi Nguyen<br />

<strong>The</strong> University <strong>of</strong> Texas at Austin<br />

Context<br />

In the last 50 years the percentage <strong>of</strong><br />

schools enrolling more than 1,000 students<br />

has grown from 7% to 25%. Between<br />

1988–1989 and 1998–1999, the number <strong>of</strong><br />

high schools with more than 1,500<br />

students doubled (Klonsky, 2002, as cited<br />

in Lawrence et al., 2002). Additionally, the<br />

number <strong>of</strong> schools in America has<br />

decreased by 70%, and the average<br />

school size has increased by 5 times<br />

(Klonsky, 2000). In Texas, a report by the<br />

Texas <strong>Education</strong> Agency (TEA, 1999)<br />

indicated an increase in enrollment <strong>of</strong><br />

666,961 students between 1987and 1998.<br />

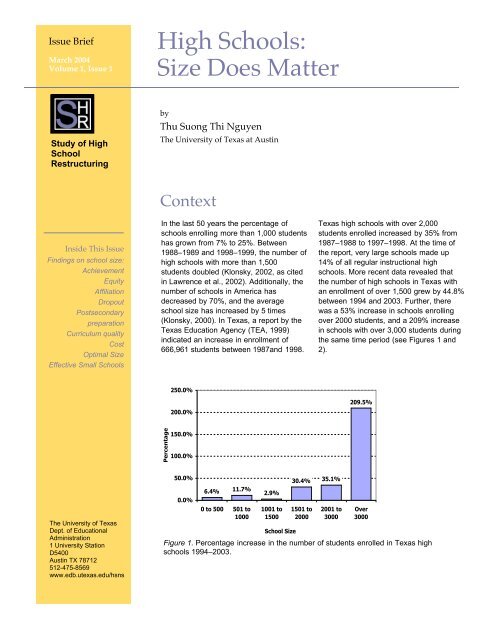

Percentage<br />

250.0%<br />

200.0%<br />

150.0%<br />

100.0%<br />

50.0%<br />

0.0%<br />

6.4% 11.7% 2.9%<br />

0 to 500 501 to<br />

1000<br />

1001 to<br />

1500<br />

School <strong>Size</strong><br />

30.4%<br />

1501 to<br />

2000<br />

Texas high schools with over 2,000<br />

students enrolled increased by 35% from<br />

1987–1988 to 1997–1998. At the time <strong>of</strong><br />

the report, very large schools made up<br />

14% <strong>of</strong> all regular instructional high<br />

schools. More recent data revealed that<br />

the number <strong>of</strong> high schools in Texas with<br />

an enrollment <strong>of</strong> over 1,500 grew by 44.8%<br />

between 1994 and 2003. Further, there<br />

was a 53% increase in schools enrolling<br />

over 2000 students, and a 209% increase<br />

in schools with over 3,000 students during<br />

the same time period (see Figures 1 and<br />

2).<br />

35.1%<br />

2001 to<br />

3000<br />

209.5%<br />

Over<br />

3000<br />

Figure 1. Percentage increase in the number <strong>of</strong> students enrolled in Texas high<br />

schools 1994–2003.

Small <strong>Schools</strong> Page 2 <strong>of</strong> 7<br />

Issue Brief Vol. 1, Issue 1<br />

Small schools have<br />

fewer than 300 students;<br />

large schools have more<br />

than 1,000.<br />

“<strong>The</strong>re is considerable<br />

evidence that large<br />

schools can have<br />

deleterious effects on<br />

students’ social<br />

development”<br />

(Haller et al., 1990).<br />

Percentage <strong>of</strong> Students<br />

100.0%<br />

90.0%<br />

80.0%<br />

70.0%<br />

60.0%<br />

50.0%<br />

40.0%<br />

30.0%<br />

20.0%<br />

10.0%<br />

0.0%<br />

25.8%<br />

22.0%<br />

38.2%<br />

Figure 2. Percentage <strong>of</strong> total number <strong>of</strong> students enrolled in schools <strong>of</strong> varying sizes<br />

in 1994 and 2003.<br />

Small <strong>Schools</strong> and the Findings<br />

<strong>The</strong> research and literature on small<br />

schools have revealed multiple variations<br />

<strong>of</strong> small schools, including small learning<br />

communities, autonomous small schools,<br />

theme-based schools, historically small<br />

schools, freestanding schools, alternative<br />

schools, schools-within-a-school, schoolswithin-a-building,<br />

house plans, career<br />

academies, pathways or clusters, multi- or<br />

scatterplexes, charter schools, pilot<br />

schools, and magnet schools. <strong>The</strong>se<br />

school types are fundamentally<br />

distinguished by their degree <strong>of</strong> autonomy<br />

and separateness from their host schools.<br />

In her summary <strong>of</strong> current literature on<br />

small schools, Raywid (1998) contended<br />

that a shift to smaller schools would better<br />

Achievement and Equity<br />

35.1%<br />

Studies have shown that small schools<br />

affect student achievement in positive<br />

ways. Fowler and Walberg (1991)<br />

summarized findings <strong>of</strong> studies conducted<br />

between the 1960s and 1980s. <strong>The</strong>se<br />

studies showed the following:<br />

1. <strong>The</strong>re is a negative relationship<br />

between achievement tests (math and<br />

verbal ability tests) and school size.<br />

36.0%<br />

42.9%<br />

0 to 1000 1001 to 2000 Over 2000<br />

School <strong>Size</strong><br />

1994<br />

2003<br />

serve students. She wrote,<br />

<strong>The</strong> small schools literature began with<br />

the large-scale quantitative studies <strong>of</strong> the<br />

late 1980s and early 1990s that firmly<br />

established small schools as more<br />

productive and effective than large ones.<br />

<strong>The</strong>se studies, involving large numbers <strong>of</strong><br />

students, schools, and districts,<br />

confirmed that students learn more and<br />

better in small schools (Lee & Smith,<br />

1995). (p. 1)<br />

Between 1966 and 2000, however, only 22<br />

research reports defined school size,<br />

socioeconomic status, and school-size<br />

issues as important to the focus <strong>of</strong><br />

research investigations (Howley, Strange,<br />

& Bickel, 2000).<br />

2. Increase in size <strong>of</strong> school is<br />

detrimental to test scores.<br />

3. Smaller schools increased learning at<br />

elementary and senior levels. African<br />

American elementary students seem<br />

particularly to benefit from being in<br />

smaller schools, and low achievers<br />

benefit from being in smaller senior<br />

high schools.

Small <strong>Schools</strong> Page 3 <strong>of</strong> 7<br />

Issue Brief Vol. 1, Issue 1<br />

4. School size is negatively related to<br />

third-grade reading and mathematics<br />

achievement when controlling for<br />

student socioeconomic status.<br />

5. As school districts increased either the<br />

number <strong>of</strong> schools in the district or the<br />

size <strong>of</strong> the school, supervisory services<br />

were being financed at the expense <strong>of</strong><br />

students’ instructional services.<br />

Recent studies have corroborated the<br />

aforementioned findings. In their 1997<br />

study, Lee and Smith found that schools in<br />

the 600–900 enrollment range have the<br />

highest achievement gains in both low and<br />

high socioeconomic schools and that<br />

school size appears to matter more in<br />

schools that enroll less-advantaged<br />

students. <strong>The</strong> TEA’s report on school size<br />

also cited recent studies that showed<br />

greater gains on the SAT and ACT in<br />

states with smaller schools as well as the<br />

disruption <strong>of</strong> negative effects <strong>of</strong><br />

socioeconomic status on achievement.<br />

Further, as can be inferred from the<br />

findings related to poverty and<br />

achievement in small schools, learning is<br />

Affiliation, Participation, School Climate, and Dropout<br />

Large schools appear also to have<br />

negative effects on student identification<br />

with schools and, thus, participation and<br />

affiliation. Pittman and Haughwout (1987)<br />

found that “larger student bodies appear to<br />

produce a less positive social environment,<br />

less social integration, and less identity<br />

with the school. <strong>The</strong>se may translate into<br />

more premature school leavings” (p. 343).<br />

School climates that are less alienating and<br />

fearful for both students and teachers<br />

contribute to the finding that “smaller<br />

school size is consistently related to<br />

stronger and safer school communities<br />

(Franklin & Crone, 1992; Zane, 1994)”<br />

(Wasley et al., 2000).<br />

Preparation for Postsecondary <strong>Education</strong><br />

Findings on the relationship between<br />

school size and student preparation for<br />

postsecondary school were meager and<br />

tenuous, likely owing to the fact that many<br />

small school start-ups have not been in<br />

more equitably distributed in smaller<br />

learning environments.<br />

<strong>The</strong> findings <strong>of</strong> the Matthew Project<br />

(Howley et al., 2000), a series <strong>of</strong> replicated<br />

studies, showed that although academic<br />

“excellence” results varied by state, overall,<br />

the influence <strong>of</strong> school size varied by<br />

socioeconomic level.<br />

A negative influence on achievement in<br />

impoverished schools and a positive<br />

influence in affluent schools were found. In<br />

their analysis <strong>of</strong> Texas schools, this finding<br />

translated into 57% <strong>of</strong> schools being too<br />

big to maximize achievement at the 10 th -<br />

grade level. <strong>The</strong> Matthew Project also<br />

looked at academic equity effects and<br />

determined that these effects were highly<br />

consistent across states and that the<br />

relationship between achievement and<br />

socioeconomic status was far weaker in<br />

smaller schools than in large schools. <strong>The</strong>y<br />

found that in Georgia, Ohio, and Texas,<br />

smaller schools reduced the negative effect<br />

<strong>of</strong> poverty on average student achievement<br />

in every grade tested.<br />

TEA reported that large schools, especially<br />

in large cities, experience a higher rate <strong>of</strong><br />

dropout than do small schools in small<br />

districts. Additionally, Lawrence et al.<br />

(2002, citing Steifel et al., 1998) reported,<br />

“<strong>Schools</strong> with fewer than 600 students had<br />

a 5% dropout rate, while larger schools<br />

averaged a 13% loss” (p. 11). <strong>The</strong><br />

researchers asserted that this finding is<br />

particularly encouraging because the small<br />

schools served a higher percentage <strong>of</strong> poor<br />

students and part-time special education<br />

students than did the larger schools.<br />

existence long enough for such an<br />

examination. However, Cotton (2001)<br />

summarized the evidence <strong>of</strong> two studies<br />

regarding college-going rates. A study by<br />

Ancess and Ort (1999) described a number<br />

Violence: Large vs.<br />

Small <strong>Schools</strong><br />

Larger schools have:<br />

825% more violent<br />

crime;<br />

270% more vandalism;<br />

378% more theft and<br />

larceny;<br />

394% more physical<br />

fights or attacks;<br />

3,200% more robberies;<br />

1,000% more weapons<br />

incidents.<br />

Source: Violence and Discipline<br />

Problems in U.S. Public <strong>Schools</strong><br />

1996–97, by the U.S. Department<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>Education</strong> (1998), Washington,<br />

DC: National Center for<br />

<strong>Education</strong>al Statistics.

Small <strong>Schools</strong> Page 4 <strong>of</strong> 7<br />

Issue Brief Vol. 1, Issue 1<br />

Cautions About Small<br />

<strong>Schools</strong>:<br />

Most <strong>of</strong> the researchers<br />

cited in this issue brief<br />

have agreed that the<br />

effects <strong>of</strong> school size are<br />

indirect and that school<br />

size may only facilitate or<br />

inhibit conditions that<br />

promote student<br />

achievement. Additionally,<br />

they have warned that<br />

small size cannot become<br />

a “simply mechanistic<br />

policy option” (Ayers,<br />

2000, p. 6) as this may<br />

open the door to elitist<br />

small schools that do not<br />

serve the goal <strong>of</strong> equitably<br />

distributed learning.<br />

<strong>of</strong> small schools in New York City, and<br />

Wasley and her colleagues (2000) looked<br />

at small schools in Chicago. Both studies<br />

showed significantly more college-bound<br />

students among the small-school<br />

graduates than among demographically<br />

similar graduates <strong>of</strong> larger schools. In<br />

particular, Ancess and Ort found an 89%<br />

college-going rate among the examined<br />

New York City small-school graduates.<br />

Curriculum Quality<br />

Proponents <strong>of</strong> consolidation argue that<br />

small schools cannot provide an adequate<br />

curriculum to their students. <strong>The</strong>y believe<br />

that comprehensive high schools are better<br />

able to <strong>of</strong>fer a broad array <strong>of</strong> course<br />

<strong>of</strong>ferings. However, Monk and Haller<br />

(1993, as cited by the TEA, 1999) found<br />

that “although large schools <strong>of</strong>ten <strong>of</strong>fer<br />

more courses, many <strong>of</strong> the additional<br />

courses are introductory or vocational in<br />

nature rather than enrichment in areas<br />

such as mathematics, science, or foreign<br />

languages” (p. 6). Furthermore, the<br />

research on small high schools has<br />

reported that (a) small schools are able to<br />

<strong>of</strong>fer courses that are well aligned with<br />

national goals, and (b) high schools<br />

enrolling as few as 100 to 200 students are<br />

able to <strong>of</strong>fer base courses in core curricular<br />

areas such as mathematics and science at<br />

rates comparable to high schools enrolling<br />

between 1,200 and 1,600 students<br />

(Roelke, 1996).<br />

Related to curricular quality, some studies<br />

have examined tracking <strong>of</strong> students within<br />

schools. Lee and Smith (1997), in<br />

particular, addressed the tracking issue.<br />

<strong>The</strong>y cited Lee and Bryk as having found<br />

that “increasing size promotes curriculum<br />

specialization, resulting in differentiation <strong>of</strong><br />

students’ academic experiences and social<br />

stratification <strong>of</strong> student outcomes” (p. 207).<br />

In contrast, the curriculum in smaller<br />

Cost<br />

A study conducted by Stiefel and others in<br />

New York City was the most frequently<br />

cited study in the literature reviewed. <strong>The</strong><br />

study looked at 128 high schools using<br />

Additionally, Wasley et al.wrote,<br />

On average, students attending smaller<br />

schools complete more years <strong>of</strong> higher<br />

education (Sares, 1992), accumulate<br />

more credit (Fine, 1994; Oxley, 1995),<br />

and score slightly better on standardized<br />

tests than students attending larger<br />

schools (Bryk & Driscoll, 1988; Fine,<br />

1994; Lee & Smith, 1996; Sares, 1992).<br />

schools is more constrained, so nearly all<br />

students follow the same course <strong>of</strong> study.<br />

This results in higher average academic<br />

achievement and achievement that is more<br />

equitably distributed across student ability<br />

and social background (Lee & Smith,<br />

1997).<br />

Although small school settings create<br />

constraints on curriculum, Unks (1989)<br />

contended that small schools <strong>of</strong>fered<br />

greater opportunities for learning than the<br />

number and scope <strong>of</strong> course <strong>of</strong>ferings<br />

would suggest. He suggested that the<br />

curriculum in small schools could be<br />

modified more easily because <strong>of</strong> the lean<br />

administrative structure, and that<br />

scheduling was flexible and easily altered.<br />

Because small schools tend to have lower<br />

student-to-teacher ratios, learner-centered<br />

atmospheres were also more viable. Unks<br />

wrote, for example,<br />

Schedules can be arranged in order to<br />

allow for field trips and assembly<br />

programs. Individualized instruction<br />

suggests that many different topics will<br />

be studied by individual students rather<br />

than all students studying the same thing<br />

in the large room in the large school.<br />

Cross-age teaching and peer tutoring<br />

also suggest that many topics—outside<br />

the textbook—will be part <strong>of</strong> the<br />

curriculum in the small school. (p. 184)<br />

school-by-school budget information for<br />

1995–1996. <strong>Schools</strong> with fewer than 600<br />

students spent $7,628 per student<br />

annually, an annual cost $1,410 more than

Small <strong>Schools</strong> Page 5 <strong>of</strong> 7<br />

Issue Brief Vol. 1, Issue 1<br />

that spent by schools with over 2,000<br />

students. What is more, looking at cost per<br />

graduate has been argued to be more<br />

useful than the traditional cost per student<br />

comparison. When looking at the cost per<br />

graduate, the cost for small schools was<br />

$49,553, compared to $49,578 at larger<br />

schools.<br />

Lawrence et al. (2002) and Wasley et al.<br />

(2000) asserted that it is far more costly to<br />

allow students to drop out than it is to<br />

Optimal <strong>Size</strong><br />

Findings on what consititutes the optimally<br />

small school have varied drastically from<br />

one researcher to the next. Some have<br />

recommended schools as small as 100<br />

total enrollment to no more than 900<br />

students. <strong>The</strong> most recent findings<br />

reported numbers between 150 and 300<br />

students, depending on the school level.<br />

Lawrence et al. (2002) provided the<br />

following guidelines for the ideal upper<br />

limits <strong>of</strong> small size for schools with<br />

Effective Small <strong>Schools</strong><br />

In her summary <strong>of</strong> the literature on small<br />

schools, Cotton (2001) outlined a number<br />

<strong>of</strong> elements necessary for the effectiveness<br />

<strong>of</strong> small schools:<br />

1. a high degree <strong>of</strong> autonomy<br />

2. separate physical and psychological<br />

boundaries between schools<br />

3. distinctive attributes setting it apart<br />

from schools in close proximity<br />

4. a self-selected student body, faculty,<br />

and staff<br />

5. flexibility in scheduling<br />

6. a self-created vision and mission<br />

7. a thematic focus<br />

8. an emphasis on academic press as<br />

well as social support<br />

9. clear, concrete, and detailed plans <strong>of</strong><br />

underpinnings and procedures<br />

10. knowing students well<br />

invest in students’ graduating. Social costs<br />

<strong>of</strong> large schools examined in the Lawrence<br />

et al. (2002) report include higher dropout<br />

rates, lower graduation rates, high rates <strong>of</strong><br />

violence and vandalism, higher<br />

absenteeism, and higher teacher<br />

dissatisfaction. Lawrence et al. wrote, “This<br />

report indicates that creating facilities for<br />

small schools can be done cost effectively,<br />

and that in fact, the cost <strong>of</strong> large schools is<br />

higher considering their negative<br />

outcomes” (p. 21).<br />

conventionally wide grade spans:<br />

• <strong>High</strong> schools (Grades 9–12): 75<br />

students per grade level (300 total<br />

enrollment);<br />

• Middle schools (Grades 5–8): 50<br />

students per grade level (200 total<br />

enrollment); and<br />

• Elementary schools (Grades 1–6): 25<br />

students per grade level (150 total<br />

enrollment) (Lawrence et al., 2000).<br />

11. heterogeneity and nontracking<br />

12. looping<br />

13. consensus building<br />

14. self-directed and conducted<br />

pr<strong>of</strong>essional development<br />

15. integrated curriculum and teaching<br />

teams<br />

16. a large repertoire <strong>of</strong> instructional<br />

strategies<br />

17. multiple forms <strong>of</strong> assessment<br />

18. authentic accountability and credibility<br />

19. support <strong>of</strong> districts, boards, and<br />

legislatures<br />

20. networking with other small learning<br />

communities for support, increased<br />

accountability, and mutual learning<br />

21. a thorough implementation <strong>of</strong> all small<br />

school structures and practices in a<br />

timely manner.<br />

Optimal Number <strong>of</strong><br />

Students:<br />

<strong>High</strong> <strong>Schools</strong>: 300<br />

Middle <strong>Schools</strong>: 200<br />

Elementary <strong>Schools</strong>: 150

Small <strong>Schools</strong> Page 6 <strong>of</strong> 7<br />

Issue Brief Vol. 1, Issue 1<br />

<strong>The</strong> work reported here<br />

is an outgrowth <strong>of</strong> the<br />

larger Houston A+<br />

Challenge initiative.<br />

Conclusion<br />

Within the last several years, the renewed<br />

small schools movement has been heading<br />

towards breaking up large comprehensive<br />

high schools into schools-within-schools<br />

serving between 200 and 500 students<br />

(Gregory, 2001). Dewees (1999) wrote,<br />

“While considerable data exists on<br />

outcomes associated with small schools,<br />

there is much less evidence about<br />

outcomes associated with school-within-aschool<br />

programs (Cotton, 1996b)” (p. 1).<br />

However, this model <strong>of</strong> small schools is<br />

believed to be a cost-effective approach to<br />

school reform in terms <strong>of</strong> start-up costs<br />

and, in some cases, maintenance.<br />

Additionally, Dewees cited evidence that<br />

References<br />

Ancess, J., & Ort, S. W. (1999). How the coalition<br />

campus schools have re-imagined high school:<br />

Seven years later. New York: National Center for<br />

Restructuring <strong>Education</strong>, <strong>Schools</strong>, and Teaching.<br />

Ayers, W. (2000). Simple justice: Thinking about<br />

teaching and learning, equity, and the fight for<br />

small schools. In W. Ayers, M. Klonsky, & G.<br />

Lyon (Eds.), A simple justice: <strong>The</strong> challenge <strong>of</strong><br />

small schools. New York: Teachers <strong>College</strong> Press.<br />

Cotton, K. (2001). New small learning communities:<br />

Findings from recent literature. Portland, OR:<br />

Northwest Regional <strong>Education</strong>al Laboratory.<br />

Darling-Hammond, L. (1997). <strong>The</strong> right to learn: A<br />

blueprint for creating schools that work. San<br />

Francisco: Jossey-Bass.<br />

Dewees, S. (1999). <strong>The</strong> school-within-a-school<br />

model (ERIC Digest). Charleston, WV: ERIC<br />

Clearinghouse on Rural <strong>Education</strong> and Small<br />

<strong>Schools</strong>.<br />

Fowler, W., & Walberg, H. J. (1991). School size,<br />

characteristics, and outcomes. <strong>Education</strong>al<br />

Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 13(2), 189-202.<br />

Gregory, T. (2001). Breaking up large high schools:<br />

Five common (and understandable) errors <strong>of</strong><br />

execution. Charleston, WV: ERIC Clearinghouse<br />

on Rural <strong>Education</strong> and Small <strong>Schools</strong>.<br />

Haller, E. J., Monk, D. H., Spotted Bear, A., Griffith,<br />

J., & Moss, P. (1990). School size and program<br />

comprehensiveness: Evidence from <strong>High</strong> School<br />

downsized school models can have a<br />

positive social impact on students.<br />

Some <strong>of</strong> the critiques <strong>of</strong> the school-withina-school<br />

model, as cited in Dewees (1999),<br />

include the creation <strong>of</strong> divisiveness in<br />

schools due to organizational realignment;<br />

conflicts concerning allegiances to the<br />

larger school versus the smaller school<br />

unit, thus creating rivalries (Muncey &<br />

McQuillan, 1991; Raywid, 1996b, both as<br />

cited in Dewees); inequitable tracking if<br />

only one population is targeted for a<br />

subschool (McMullan, Sipe, & Wolfe, 1994;<br />

Raywid, 1996a, both as cited in Dewees);<br />

and the model may negatively affect school<br />

coherence and the role <strong>of</strong> the principal.<br />

and Beyond. <strong>Education</strong>al Evaluation and Policy<br />

Analysis, 12(2), 109-120.<br />

Howley, C., Strange, M., & Bickel, R. (2000).<br />

Research about school size and school<br />

performance in impoverished communities.<br />

Charleston, WV: ERIC Clearinghouse on Rural<br />

<strong>Education</strong> and Small <strong>Schools</strong>.<br />

Klonsky, M. (2000). Remembering Port Huron. In<br />

W. Ayers, M. Klonsky, & G. Lyon (Eds.), A simple<br />

justice: <strong>The</strong> challenge <strong>of</strong> small schools. New<br />

York: Teachers <strong>College</strong> Press.<br />

Lawrence, B. K., Bingler, S., Diamond, B. M., Hill,<br />

B., H<strong>of</strong>fman, J. L., Howley, C. B., Mitchell, S.,<br />

Rudolph, D., & Washor, E. (2002). Dollars and<br />

sense: <strong>The</strong> cost effectiveness <strong>of</strong> small schools.<br />

Cincinnati, OH: Knowledge Works Foundation.<br />

Lee, V. E., & Smith, J. B. (1995). Effects <strong>of</strong> high<br />

school restructuring and size on early gains in<br />

achievement and engagement. Sociology <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Education</strong>, 68, 241-270.<br />

Lee, V. E., & Smith, J. B. (1997). <strong>High</strong> school size:<br />

Which works best and for whom? <strong>Education</strong>al<br />

Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 19(3), 205-227.<br />

Pittman, R. B., & Haughwout, P. (1987). Influence<br />

<strong>of</strong> high school size on dropout rate. <strong>Education</strong>al<br />

Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 9(4), 337-343.<br />

Raywid, M. (1998). Current literature on small<br />

schools. Charleston, WV: ERIC Clearinghouse<br />

on Rural <strong>Education</strong> and Small <strong>Schools</strong>.

Roelke, C. (1996). Curriculum adequacy and<br />

quality in high schools enrolling fewer than 400<br />

Pupils (9–12). Charleston, WV: ERIC<br />

Clearinghouse on Rural <strong>Education</strong> and Small<br />

<strong>Schools</strong>.<br />

Texas <strong>Education</strong> Agency. (1999, January). School<br />

size and class size in Texas public schools. (TEA<br />

report 12). Austin: Texas <strong>Education</strong> Agency<br />

Policy Planning and Evaluation Division.<br />

U.S. Department <strong>of</strong> <strong>Education</strong>. (1998, March).<br />

Violence and discipline problems in U.S. public<br />

schools 1996–97. (NCES No. 98030).<br />

Washington, DC: National Center for <strong>Education</strong>al<br />

Statistics.<br />

About Our Organization…<br />

<strong>The</strong> Houston A+ Challenge received funding from the Carnegie Corporation and the Bill<br />

and Melinda Gates Foundation to support a 5-year initiative to work with 24 large high<br />

schools in the Houston Independent School District engaged in a student-focused, wholeschool<br />

change effort. <strong>The</strong> initiative, called Houston <strong>Schools</strong> for a New Society, redesigns<br />

high schools into small, theme-based academies to produce graduates ready for the<br />

demands <strong>of</strong> the 21st century.<br />

<strong>The</strong> central goal <strong>of</strong> the challenge is to determine whether it is possible to develop and to<br />

institutionalize high school reform nationally by investing in specific urban areas through<br />

intensive intervention. <strong>The</strong> HA+C strategy undertakes work in four areas:<br />

1. Restructure large comprehensive high schools into small learning communities.<br />

2. Install a literacy framework across the core curriculum.<br />

Unks, G. (1989). Differences in curriculum within a<br />

school setting. <strong>Education</strong> and Urban Society,<br />

21(2), 175-191.<br />

Wallach, C. A., & Lear, R. (2003). An early report<br />

on comprehensive high school conversions.<br />

Seattle, WA: <strong>The</strong> Small <strong>Schools</strong> Project.<br />

Wasley, P. A, Fine, M., Gladden, M., Holland, N.<br />

E., King, S. P., Mosak, E., & Powell, C. (2000).<br />

Small schools: Great strides. A study <strong>of</strong> new<br />

small schools in Chicago. Chicago: Bank Street<br />

<strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Education</strong>.<br />

3. Create an adult advocacy program to mentor and to help each high school student.<br />

4. Create new knowledge about the challenges and issues related to the restructuring <strong>of</strong><br />

high schools in urban areas.<br />

We have designed an evaluation program to learn from the HA+C experience to promote<br />

further high school improvement in Houston and other urban school districts across the<br />

country.<br />

Study <strong>of</strong> <strong>High</strong><br />

School<br />

Restructuring<br />

Principal Investigator:<br />

Pedro Reyes, Ph.D.<br />

Study <strong>of</strong> <strong>High</strong><br />

School<br />

Restructuring<br />

Project Manager:<br />

Ed Fuller, Ph.D.<br />

We’re on the Web!<br />

www.edb.utexas.edu/hsns<br />

Houston <strong>Schools</strong> for a New Society<br />

Evaluation<br />

<strong>The</strong> University <strong>of</strong> Texas<br />

Dept. <strong>of</strong> <strong>Education</strong>al Administration<br />

1 University Station D5400<br />

Austin, TX 78712<br />

512-475-8569<br />

512-475-8580<br />

© 2004 Study <strong>of</strong> <strong>High</strong> School<br />

Restructuring, University <strong>of</strong> Texas<br />

Edited and designed by<br />

Jennifer E. Cook