In Search of an Enforceable Medical Malpractice Exculpatory

In Search of an Enforceable Medical Malpractice Exculpatory

In Search of an Enforceable Medical Malpractice Exculpatory

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

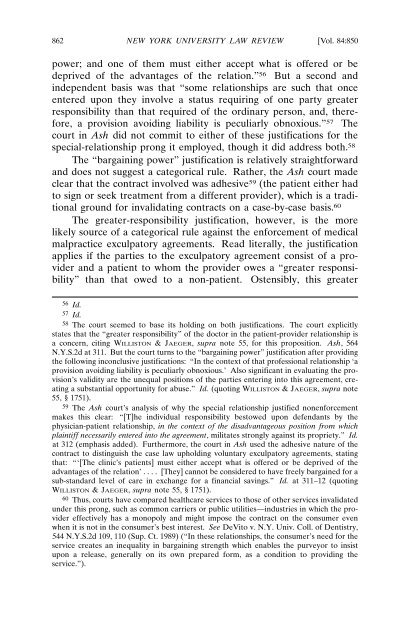

862 NEW YORK UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW [Vol. 84:850<br />

power; <strong>an</strong>d one <strong>of</strong> them must either accept what is <strong>of</strong>fered or be<br />

deprived <strong>of</strong> the adv<strong>an</strong>tages <strong>of</strong> the relation.” 56 But a second <strong>an</strong>d<br />

independent basis was that “some relationships are such that once<br />

entered upon they involve a status requiring <strong>of</strong> one party greater<br />

responsibility th<strong>an</strong> that required <strong>of</strong> the ordinary person, <strong>an</strong>d, therefore,<br />

a provision avoiding liability is peculiarly obnoxious.” 57 The<br />

court in Ash did not commit to either <strong>of</strong> these justifications for the<br />

special-relationship prong it employed, though it did address both. 58<br />

The “bargaining power” justification is relatively straightforward<br />

<strong>an</strong>d does not suggest a categorical rule. Rather, the Ash court made<br />

clear that the contract involved was adhesive 59 (the patient either had<br />

to sign or seek treatment from a different provider), which is a traditional<br />

ground for invalidating contracts on a case-by-case basis. 60<br />

The greater-responsibility justification, however, is the more<br />

likely source <strong>of</strong> a categorical rule against the enforcement <strong>of</strong> medical<br />

malpractice exculpatory agreements. Read literally, the justification<br />

applies if the parties to the exculpatory agreement consist <strong>of</strong> a provider<br />

<strong>an</strong>d a patient to whom the provider owes a “greater responsibility”<br />

th<strong>an</strong> that owed to a non-patient. Ostensibly, this greater<br />

56 Id.<br />

57 Id.<br />

58 The court seemed to base its holding on both justifications. The court explicitly<br />

states that the “greater responsibility” <strong>of</strong> the doctor in the patient-provider relationship is<br />

a concern, citing WILLISTON & JAEGER, supra note 55, for this proposition. Ash, 564<br />

N.Y.S.2d at 311. But the court turns to the “bargaining power” justification after providing<br />

the following inconclusive justifications: “<strong>In</strong> the context <strong>of</strong> that pr<strong>of</strong>essional relationship ‘a<br />

provision avoiding liability is peculiarly obnoxious.’ Also signific<strong>an</strong>t in evaluating the provision’s<br />

validity are the unequal positions <strong>of</strong> the parties entering into this agreement, creating<br />

a subst<strong>an</strong>tial opportunity for abuse.” Id. (quoting WILLISTON & JAEGER, supra note<br />

55, § 1751).<br />

59 The Ash court’s <strong>an</strong>alysis <strong>of</strong> why the special relationship justified nonenforcement<br />

makes this clear: “[T]he individual responsibility bestowed upon defend<strong>an</strong>ts by the<br />

physici<strong>an</strong>-patient relationship, in the context <strong>of</strong> the disadv<strong>an</strong>tageous position from which<br />

plaintiff necessarily entered into the agreement, militates strongly against its propriety.” Id.<br />

at 312 (emphasis added). Furthermore, the court in Ash used the adhesive nature <strong>of</strong> the<br />

contract to distinguish the case law upholding voluntary exculpatory agreements, stating<br />

that: “‘[The clinic’s patients] must either accept what is <strong>of</strong>fered or be deprived <strong>of</strong> the<br />

adv<strong>an</strong>tages <strong>of</strong> the relation’ . . . . [They] c<strong>an</strong>not be considered to have freely bargained for a<br />

sub-st<strong>an</strong>dard level <strong>of</strong> care in exch<strong>an</strong>ge for a fin<strong>an</strong>cial savings.” Id. at 311–12 (quoting<br />

WILLISTON & JAEGER, supra note 55, § 1751).<br />

60 Thus, courts have compared healthcare services to those <strong>of</strong> other services invalidated<br />

under this prong, such as common carriers or public utilities—industries in which the provider<br />

effectively has a monopoly <strong>an</strong>d might impose the contract on the consumer even<br />

when it is not in the consumer’s best interest. See DeVito v. N.Y. Univ. Coll. <strong>of</strong> Dentistry,<br />

544 N.Y.S.2d 109, 110 (Sup. Ct. 1989) (“<strong>In</strong> these relationships, the consumer’s need for the<br />

service creates <strong>an</strong> inequality in bargaining strength which enables the purveyor to insist<br />

upon a release, generally on its own prepared form, as a condition to providing the<br />

service.”).