SECTION 1 - via - School of Visual Arts

SECTION 1 - via - School of Visual Arts

SECTION 1 - via - School of Visual Arts

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

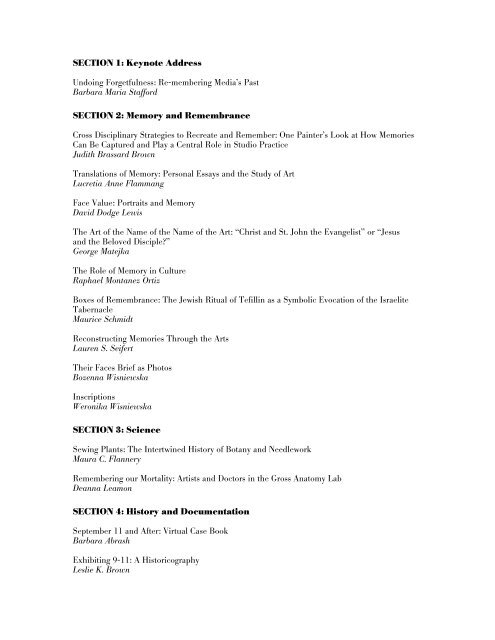

<strong>SECTION</strong> 1: Keynote Address<br />

Undoing Forgetfulness: Re-membering Media’s Past<br />

Barbara Maria Stafford<br />

<strong>SECTION</strong> 2: Memory and Remembrance<br />

Cross Disciplinary Strategies to Recreate and Remember: One Painter’s Look at How Memories<br />

Can Be Captured and Play a Central Role in Studio Practice<br />

Judith Brassard Brown<br />

Translations <strong>of</strong> Memory: Personal Essays and the Study <strong>of</strong> Art<br />

Lucretia Anne Flammang<br />

Face Value: Portraits and Memory<br />

David Dodge Lewis<br />

The Art <strong>of</strong> the Name <strong>of</strong> the Name <strong>of</strong> the Art: “Christ and St. John the Evangelist” or “Jesus<br />

and the Beloved Disciple?”<br />

George Matejka<br />

The Role <strong>of</strong> Memory in Culture<br />

Raphael Montanez Ortiz<br />

Boxes <strong>of</strong> Remembrance: The Jewish Ritual <strong>of</strong> Tefillin as a Symbolic Evocation <strong>of</strong> the Israelite<br />

Tabernacle<br />

Maurice Schmidt<br />

Reconstructing Memories Through the <strong>Arts</strong><br />

Lauren S. Seifert<br />

Their Faces Brief as Photos<br />

Bozenna Wisniewska<br />

Inscriptions<br />

Weronika Wisniewska<br />

<strong>SECTION</strong> 3: Science<br />

Sewing Plants: The Intertwined History <strong>of</strong> Botany and Needlework<br />

Maura C. Flannery<br />

Remembering our Mortality: Artists and Doctors in the Gross Anatomy Lab<br />

Deanna Leamon<br />

<strong>SECTION</strong> 4: History and Documentation<br />

September 11 and After: Virtual Case Book<br />

Barbara Abrash<br />

Exhibiting 9-11: A Historicography<br />

Leslie K. Brown

Photography Through Documentation and Intention<br />

Anna Heineman<br />

<strong>SECTION</strong> 5: The Art <strong>of</strong> Persuasion<br />

Meritorious or Meretricious<br />

Jacqueline Belfort-Chalat<br />

<strong>SECTION</strong> 6: The Educated Artist<br />

Shared Spaces, Unexpected Sources<br />

Bowdoin Davis, Jr<br />

Remembering Rabindranath Tagore<br />

Mark W. McGinnis<br />

<strong>SECTION</strong> 7: Public Memorials<br />

Monuments in Minimalism: Safely Universal<br />

David Evenhuis<br />

Brancusi at Tirgu-Jiu<br />

Maureen Korp<br />

<strong>SECTION</strong> 8: The Holocaust<br />

Mourning, Absence, and Trauma: Representations <strong>of</strong> the Holocaust in Contemporary Art and<br />

Architecture<br />

Milton S. Katz<br />

<strong>SECTION</strong> 9: Curriculum<br />

With a Pen as His Word and Me as His Witness<br />

Michael Fink<br />

From Idealism to Totalitarianism: The History <strong>of</strong> History Painting<br />

Robert Hendrick<br />

Inhumane Humanities: Colleges <strong>of</strong> Education in Retreat From the Human Experience<br />

James E. Nowlin<br />

Teaching Art Education in a Studio Oriented Art Department<br />

Shari S. Stoddard<br />

Vers Collage: The Remembrance Work <strong>of</strong> Poetry<br />

Beverly Schneller

THE SCHOOL OF VISUAL ARTS NATIONAL CONFERENCE ON LIBERAL ARTS<br />

AND THE EDUCATION OF ARTISTS: ART REMEMBERS<br />

Guest Speaker: Barbara Maria Stafford, University <strong>of</strong> Chicago<br />

Dr. Hendricks: This afternoon I have the pleasure to introduce our keynote speaker, Barbara<br />

Maria Stafford, the William B. Ogden distinguished service pr<strong>of</strong>essor at the University <strong>of</strong><br />

Chicago. Dr. Stafford specializes in art and imaging theory from the late 17th century to the<br />

Romantics and her focus has been on the intersection between the arts and the sciences in<br />

early modern and modern periods. Her two recent works, <strong>Visual</strong> Analogy and Devices <strong>of</strong><br />

Wonder, help reconcile the diverse elements <strong>of</strong> the history <strong>of</strong> western art through the concept<br />

<strong>of</strong> visual analogy. Dr. Stafford emphasizes the connections—“proliferations” is the term she<br />

uses—and not the chain <strong>of</strong> cause and effect. Dr. Stafford’s books include, Symbol and Myth,<br />

Voyage into Substance, Body Criticism, Artful Science, Good-looking, <strong>Visual</strong> Analogy and, with<br />

Francis Turpac, Devices <strong>of</strong> Wonder: From the World in a Box to Images on Screen. Will you<br />

please welcome Dr. Stafford.<br />

Dr. Stafford: Thank you. It’s a great honor for me to be here in this worthwhile endeavor and I<br />

hope to contribute to the proceeding. I’m going to be using material from the Devices <strong>of</strong><br />

Wonder exhibition to reflect on some major themes that I hope that it will intercept rather<br />

nicely with the topics <strong>of</strong> the conference. Rudolph Arnheim, in an essay that has really been<br />

forgotten from the 1960’s, a plea for perceptual thinking. In it he suggests that optical<br />

technology can become a thoughtful medium. I’m going to suggest that it is not yet become<br />

that. We’re still waiting for that to happen and I’m going to try and demonstrate in my<br />

presentation that contemporary media needs memory.<br />

Contemporary medium needs to recall that vast and sophisticated repertoire <strong>of</strong> earlier medium,<br />

medium that we’ve just thrown on the junk heap <strong>of</strong> history to fulfill the potential that Arnheim<br />

saw. Arnheim’s summons in the 60’s in turn was a re-remembering. He is in a way re-casting<br />

some <strong>of</strong> the prior writings <strong>of</strong> Abby Warburg writing in the 20s and in the 30s. Now Abby<br />

Warburg, that pr<strong>of</strong>ound historian <strong>of</strong> visual culture, proposed that visual images—those<br />

imaginative spatial forms ranging from high art to popular emergent media—roused the eyes at<br />

action, that lovely phrase <strong>of</strong> his. But these fleeting shapes and mutable figures also excite our<br />

memory, consciousness and desire by their ability to intensify and so alter reality.<br />

Not surprisingly then such vivid apparitions spun merely from light, shadow, and color engaged<br />

the total person at the sensory, psychological and social levels. And again I’d like to say it’s<br />

important that what people like Warburg, like Arnheim, like Kepes, for that matter, were<br />

talking about was not immersive media but rather the ability <strong>of</strong> media to create personal<br />

coherence at very deep level. I’m going to try to suggest ways in which these older media do<br />

that and what we have not yet achieved today. I’m going to show you some images rather<br />

quickly and then I’m going to ponder them and bring in other ones as we go on.<br />

[The first two slides; both please.] When optical devices such as mirrors and lenses actually<br />

appear, I’m going to be showing you because <strong>of</strong> the other thing that we’ve forgotten is the<br />

complexity <strong>of</strong> mirroring; just simply think <strong>of</strong> mirrors as flat. This is not the case. When mirrors,<br />

lenses here in a zograscope [the next two slides please], magic lanterns, peep show boxes or<br />

1

computer screens for that matter are placed between our eyes in the world, those natural<br />

images that Arnheim or Warburg spoke about become ramped up into high fidelity. I show you<br />

here a crank magic lantern slide from the 19th century and a mondo nuovo if you could see it<br />

in one <strong>of</strong> John [sounds like “DeMangochapello’s”] famous frescos. These just give you a sense<br />

<strong>of</strong> range <strong>of</strong> devices.<br />

Perception amplifying technology is going to be my theme <strong>of</strong> the next two images. I’m going to<br />

show you how they entangle with quests for other worldly revelation. Here, a late 18th century<br />

print shows a phantom - actually ghost projecting technologies and on the right, from the<br />

middle <strong>of</strong> the 19th century, the media that re-mediates other medias. So these are stereo cards<br />

but you notice that the stereo cards, which belong in one kind <strong>of</strong> technology, are reproducing<br />

another in this case a polyorama panoptique so again just to get multiple levels <strong>of</strong> complexity<br />

before your minds. So perception amplifying technology is entangled with quests for other<br />

worldly revelation, for a kind <strong>of</strong> escapist entertainment. [Next on the right please], and <strong>of</strong><br />

course also worldly pursuits <strong>of</strong> knowledge. This is a wonderful French mid 18th century<br />

microscope. It was thought to have belonged to the abbé Nollet who was the tutor to Louis<br />

XV’s children but now we know it isn’t but you notice this teeters between scientific equipment<br />

and sculpture but the perception amplifying technology embracing all <strong>of</strong> these domains. It lures<br />

us with the prospect <strong>of</strong> boundlessness, immediacy and connectedness. Viewers are swiftly<br />

displaced from their normal surroundings and effortlessly thrust into a synthetic or better than<br />

ordinary hyper-realm.<br />

[Both slides please] We tried to show, there have been many many exhibitions devoted to<br />

technology and the arts in one fashion or another since the bit-stream show at San Francisco,<br />

MoMA had Zero One Zero One Zero One. Barbicon just closed a show on video games. This is<br />

all the rage. Most <strong>of</strong> these exhibitions are busy in one fashion or another tracing the function <strong>of</strong><br />

modern scientific equipment in art from futurist and constructivist movements and their<br />

enthrallment with machines to kinetic sculpture onto cave environments. Now we had some<br />

pieces like that and I will show you two but, hopefully, in an unexpected way. This is Jesuit,<br />

17th century, the invention <strong>of</strong> pantographic machines to make reproducing drawings and other<br />

materials easier and this is a very early Alexander Calder pantograph so yes, we had some <strong>of</strong><br />

these things but our interest was more in recuperating something more complex. This haunted<br />

view <strong>of</strong> eye machines old and new other aspects <strong>of</strong> these complex technologies. These are both<br />

personal reality enhancers.<br />

Material [next two slides please] more like this. Here is a transparent screen from the<br />

Metropolitan and on the right, a Feliciano Béjar cluster <strong>of</strong> Magiscopios from the middle <strong>of</strong> the<br />

1960s but themselves remembering the great Jesuit catoptrical experiments about which I’m<br />

going to speak a little bit late. So in interest and through which I think speaks more to the<br />

memory aspect <strong>of</strong> this convention about the enhancement <strong>of</strong> one’s personal reality and how it<br />

impinges on all aspects <strong>of</strong> the human psyche. Part <strong>of</strong> what it means to be human has<br />

increasingly involved the instrumentalization <strong>of</strong> the biological self. We routinely construct our<br />

emotional and cognitive states not just from the inside out, from the outside in with gadgetized<br />

additives. We’re quite accustomed to that but it’s really a very, very old practice. Already since<br />

the 16th century, mind-bending apparatus has been busy altering solid bodies into more<br />

vibrant virtual events.<br />

2

[Both please.] There’s another paradox that I want to suggest from this perspective <strong>of</strong> memory;<br />

with all the emphasis on now-ness, the emergent aspect <strong>of</strong> technologies—what tends to get<br />

forgotten—is that what persists <strong>of</strong>ten in the cultural imaginary is the obsolete artifact most<br />

remote from the future-obsessed present. Even the most dead-seeming media hint at an<br />

undercurrent <strong>of</strong> unsatisfied desires still alive but submerged in the new medium world. Here<br />

again from the 17th century, a split level print all showing the private and the public<br />

conducting a Jesuit machine for capturing and tracing solar spots. This was the age <strong>of</strong><br />

wunderkammern, the age <strong>of</strong> the little ice age where there was an enormous amount <strong>of</strong> sun spot<br />

activity and this—in this dark chamber and up above the private—the public conducting <strong>of</strong><br />

science as in, as the obverse <strong>of</strong> this private investigation. I want to link that to desires that<br />

never get satisfied and that thrive in a kind <strong>of</strong> undercurrent. These—this is a series <strong>of</strong><br />

photomontages by Michael Light taken from NASA shots <strong>of</strong> the moon—it seems to me that<br />

there is a pr<strong>of</strong>ound connection between these two if we unearth them and that is on one level<br />

the attempt to seize the remote and the elusive and bring that down to earth. The potency <strong>of</strong><br />

sense-extending instruments links today’s motorized joysticks, mobile mouses, touch pads and<br />

cosmic architecture to the optical contrivances <strong>of</strong> the prior curiosity ridden age. Here from the<br />

London Royal Science Museum these are multiplying spectacles and I’m juxtaposing it with the<br />

brilliant Lucas Samaras’ Infinity Box, that Leibnizian box at the Albright-Knox which could not<br />

have been conceived without Jesuit experiments.<br />

I also want to draw your attention to something else—the ability to see like another. I mean<br />

quite clearly in the 17th century, the days <strong>of</strong> Hooke, Micrographia and the Royal Society,<br />

people realized that human beings don’t see like this and you have to ask what did they think<br />

when they looked through spectacles like this and saw a totally different other—like an insect. It<br />

was a way <strong>of</strong> imagining another, a totally alien way <strong>of</strong> looking just as obversely if I can turn<br />

around Samaras and suggest that it’s interesting to look at Samaras’ box and I write about that<br />

this way in <strong>Visual</strong> Analogy that Leibniz actually found his entire monadology on the idea that<br />

you multiply almost digital because they are digital panes <strong>of</strong> glass to infinity and what you get<br />

just like with the monads is not sameness, you get difference. So we can turn in both cases, we<br />

can reverse the system.<br />

So another aspect <strong>of</strong> this [both please], if these things got talked about at all, I suggest that<br />

whether they get thrown into one <strong>of</strong> these mass exhibitions that are marching the arts and<br />

sciences forward, or they’re hauled in as a bit <strong>of</strong> legacy, or they are shown, considered or<br />

remembered at all, they are employed as stages on the road to cinema or to photography, the<br />

animated image. This is the other place they appear. Even the few items that I have shown you,<br />

how can they be reduced to such a monalogical trajectory? For example these are magnetic<br />

paintings. They had concealed magnets in them and they spin, they twirl. You can see that they<br />

are immensely interesting from the point <strong>of</strong> view <strong>of</strong> complex surfaces. Simply by rotating<br />

yourself or them, different information is given to you. They are ciphered and decipherable at<br />

the same time so that these ingenious complex artifacts can’t be marched down narrow<br />

trajectories.<br />

Optical technology then is a vast and diverse region. It contains multitudes and I want to help<br />

recuperate, as we did in the Devices <strong>of</strong> Wonder show, some glimmers <strong>of</strong> its multiple functions<br />

and multiple realities, its polyopticalities that have been forgotten. We talk about multi-media<br />

but it’s really a multi-medium. Everything compresses into narrower, narrower platforms, which<br />

look the same. Here it’s the polyopticality that’s important and to demonstrate some <strong>of</strong> the<br />

3

vicissitudes <strong>of</strong> these wonder inducing, spiritual and supernatural and knowledge producing<br />

technologies all these different ranges that help to give the early moderns a kind <strong>of</strong> coherence<br />

which our media have yet to give us.<br />

[Sorry I’m going to skip; both please] The folks at Micros<strong>of</strong>t, DreamWorks, and Electronic <strong>Arts</strong>,<br />

may indeed be at the leading edge <strong>of</strong> breaking the boundaries <strong>of</strong> the monitor but this tendency<br />

that I’ve suggested to you with these personal reality enhancers <strong>of</strong> fictional experience bleeding<br />

into real life and for real life to emancipate itself through sublime magictry started much<br />

earlier. From Rococo automata—here I show you a playbill and we actually had the stage<br />

reconstructed at the show—up there you can see there are two automata. There is the type <strong>of</strong><br />

dancer and the Turk—the twisting Turk from Rococo automata that are rouged, powdered, and<br />

bewigged to Steven Spielberg’s and Stanley Kubrick’s A.I. with its winsome robot child, biology<br />

has been steadily leaking into cybernetics. Both early modern and post-human engineered<br />

organisms resonate with this symbolism <strong>of</strong> domesticated technology, it’s also technology that is<br />

being brought into the home.<br />

[Both please.] Where do we consider [sounds like “beaucoups sans”?] refined eating, digesting<br />

and defecating or van Oeckelen’s romantic, virtuoso over-life size Android Clarinetist or with<br />

the mephistophelean title <strong>of</strong> Antonio Diabolo designed by - engineered by - Robert Houdini,<br />

the same Robert Houdini who was a magician and one <strong>of</strong> the founders <strong>of</strong> cinema. Or<br />

Spielberg’s industrial prototype, we could consider him as well, David waiting to be persuaded<br />

by his programming that he exists in the flesh. All these artificial life forms [both please], we<br />

need to recall that the early moderns were also aware that they inhabited a familiar if<br />

ambiguous information universe and these types <strong>of</strong> images are very useful as a reminder how<br />

old the realization is that robotics teeters between covert and overt operations, that technology<br />

is very much alive with slight <strong>of</strong> hand. I show you a vase <strong>of</strong> cups and balls and a wonderful<br />

blow book used by the fairground charlatan where, just by skill, with a series <strong>of</strong> blank pages in<br />

between, they could be rotated and shifted because they were also notched on the side. This<br />

aspect <strong>of</strong> technology has always been fraught with ambiguity but, again, realized quite early on.<br />

[The next two please.] I want now to take the core piece <strong>of</strong> our exhibition, the one that gave<br />

the title The World in a Box which we saw also as the root <strong>of</strong> that universal toolbox, the<br />

computer and use it as a way to explore some <strong>of</strong> these things that I have said rather rapidly in<br />

more detail. Perhaps only contemporary viewers can fully appreciate that the early modern<br />

cabinet <strong>of</strong> wonder—and I show you a rather small one here—is no mere period piece. It’s not<br />

something just to be dismissed and thrown on the scrap heap <strong>of</strong> history. It’s a global project to<br />

order actual complex world <strong>of</strong> information coming from many different fields and standpoints is<br />

a project that still beckons and vexes us. The mysterious gatherings concealed inside this<br />

wunderschränke are hinted at by an encyclopedic map, new creations and marvels crowning the<br />

top. Now what you have to understand is these sorts <strong>of</strong> boxes have been written about as<br />

theaters <strong>of</strong> the world, as bringing the macrocosm <strong>of</strong> the universe into a small confines, as the<br />

ancestor <strong>of</strong> the museum but what it hasn’t been written about is a cabinet/instrument, which I<br />

do in the catalog. That is, these are also quasi-automata. They belong to a class <strong>of</strong> furniture,<br />

smart furniture we would say today that the French called “mobile a secret”- secret furniture.<br />

Furniture with secrets, why? Because they rotate, they fold out, they have springs, they have<br />

concealed drawers. When you first approach, you notice here it swung open, I’ll show you that<br />

all four sides open and the doors themselves open. It telescopes out and I use the instrumental<br />

analogy quite on purpose. When you first approach it, it’s cloaked in dark ebony wood and<br />

4

actually this mountain on top is an encyclopedic compendant that gives you a hint <strong>of</strong> the<br />

secrets that you will find when you open it. There are <strong>of</strong> course ranges <strong>of</strong> much larger ones, the<br />

famous one in [sounds like “Oupsella”?] which is almost room size; it takes by the way four<br />

rooms to empty all the contents out that are in there but what I want to draw your attention to<br />

is that if you walk around the one in [sounds like “Oupsella”?] there are water splashes on the<br />

back because <strong>of</strong> you could also wash your face; there’s a basin in there so that not only did- so<br />

it’s the all purpose toolbox. I want you to think <strong>of</strong> it in that mechanical term, a way in which<br />

one can also make the analogy to the Internet.<br />

One final point because I don’t want to get- lose my time is these are also haptic. There are<br />

drawers that pull out, a panel that pulls out so that you could lay contents, you could speak<br />

with people that you show. Some <strong>of</strong> the larger ones actually have musical instruments, spinets,<br />

claviers, and there were both artificial and natural clocks concealed in the shelves and so on.<br />

So that we can say that the way in which you experience these devices is a totally sensory<br />

involving way. It’s not merely optical and so a kind <strong>of</strong> divination is technological ritual in the<br />

way you would explore it. I show you here just the remainder <strong>of</strong> the gallery space.<br />

[The next on the right please.] I’m now going to show a series <strong>of</strong> six installation shots, just<br />

simply to show them, so that you can see the kinds <strong>of</strong> juxtapositions coming actually out <strong>of</strong> my<br />

analogy book—a news kind <strong>of</strong> organization where the pattern itself is informative. Where the<br />

past is not that beautiful quote, the White Queen quote by Maryhelen <strong>of</strong> that the past is not<br />

separated from the present, the past is the future. There’s Suzanne Anker’s lovely piece so that<br />

we have the Michael Light and Suzanne Anker; we have the microcosm, macrocosm <strong>of</strong> the<br />

body and the Michael Light and looking straight through because there’s a tunnel in the<br />

middle so that not only do you have all the drawers but you have crisscrossing. Very nice in<br />

terms <strong>of</strong> analogical structure just showing you some <strong>of</strong> the details. It floats on top as you saw it,<br />

this podium which has glass so that you’re not constantly having the obtrusiveness <strong>of</strong> vitrines,<br />

documentation and art materials at the same level not separated. Looking through here, a<br />

wonderful rare Jeff Wall, A Ventriloquist at a Birthday Party in October 1947, and facing, the<br />

Lucas Samaras box which almost killed Fran and me; we argued for a complex exhibition,<br />

getting away from linear constructions to a non-linear layout.<br />

I’m totally leaving behind Plato’s cave as primeval cabaret. This is just to show you something<br />

<strong>of</strong> the foldout potential, as in cladistics or phylogenetics which try to show how species both<br />

extent and extinct are related. The potency <strong>of</strong> all these objects and their workings out in the<br />

wundertrunk derive less from sheer number that from their complex branching surprise<br />

groupings and multitude-ness interactions with the changing environment and the shifting<br />

perceiver or the shifting beholder so that you’re constantly moving in and out and this<br />

arrangement, this pattern is an intelligent pattern, an associational pattern in that sense. It’s not<br />

a free for all.<br />

[Both slides please.] Both a crafty container housing a microcosm <strong>of</strong> natural and artificial<br />

prodigies and an absolute instrument drawing into itself no less than everything, the<br />

wundertrunk and its progeny invite the user to join the distributive singularities into a network<br />

or correspondences so you get away from this notion <strong>of</strong> a passing viewer. The need to handle or<br />

perform the objects—this theatrical performative dimension—has to do with an active notion <strong>of</strong><br />

knowledge, an active theory <strong>of</strong> education if you will. Collections <strong>of</strong> rarities, now I want to show<br />

you how quickly they’re remediated so you don’t think that this is just one kind <strong>of</strong> object.<br />

5

These objects became remediated in many, many ways and I want to show you two possible<br />

ends <strong>of</strong> this remediation. Collections <strong>of</strong> rarities, shells, gems, coins, sculpture, painting,<br />

watches, and automata were material expressions <strong>of</strong> the turn towards the empirical first<br />

emerging in the 16th and 17th centuries.<br />

[Both <strong>of</strong> them please; focus please]. Here on one end you see that it expands into rooms upon<br />

rooms. This is Levinus Vincent’s famous collection in Amsterdam and print from 1715 where<br />

you have rooms and rooms going on but I want to draw your attention to the interactive mode,<br />

the conversational mode, <strong>of</strong> knowing but here something that fits in the palm <strong>of</strong> my hand at the<br />

other end <strong>of</strong> the spectrum for five pence even, the infant’s cabinet <strong>of</strong> shells. There was also an<br />

infant’s cabinet <strong>of</strong> flowers and so on that is a learning tool, a high art object but also a private<br />

object. Here you have a more public aspect but here you have kind <strong>of</strong> private educational<br />

aspect and you also have a whole economic range in between so these media get re-mediated.<br />

I’m proposing then that the wundertrunk or the cabinet is an inter-sensual for personal<br />

realization and transformation as the little child would be if it handled those little blocks and as<br />

the adult is on my example in the left. Such assemblages, however—and this has to do with the<br />

panel this evening—also constituted a cultural inventory and artismo archive exposing the<br />

collective heritage <strong>of</strong> nature and humanities greatest handiwork. But the French have been<br />

great in recent years—everything is [UI] this and [UI] that you know, this is our national<br />

patrimony. Nobody has ever pointed out what is in these wonder cabinets is, in a way, God, the<br />

great unusual singularities produced by God but also the singularities proved and produced by<br />

human skill, by ingenuity, by the power <strong>of</strong> the imagination <strong>of</strong> the artist and that the items in<br />

there are kind <strong>of</strong> cultural inventory. A cultural archive <strong>of</strong> empirical skill, <strong>of</strong> skills, <strong>of</strong> skills <strong>of</strong><br />

the hand. Another aspect <strong>of</strong> this material that has not been pointed out is that it also points<br />

elsewhere, the beyondness <strong>of</strong> this technology and that we’re familiar with in the contemporary<br />

world but I want to try and show it to you much earlier. This technology broadened horizons by<br />

exposing an intangible domain, lying beyond the boundary <strong>of</strong> the unaided senses and<br />

accessible only through optical devices.<br />

[Both please.] I want to propose to you that cabinets and instruments also share certain formal<br />

properties. Here again, in a bulging bulbous mirror a convex mirror and a wonderful joke one<br />

<strong>of</strong> Joseph Cornell’s crystal cages, a continuation <strong>of</strong> that wundertrunk tradition. The practice <strong>of</strong><br />

confining and isolating rarities in a compressed space is not just western; you find it in Japan,<br />

in China, in India. No matter what else you do to it, compression intensifies the aura and<br />

strangeness <strong>of</strong> those objects.<br />

[Next on the right please.] Like the wooden cabinet with its swirl away oddities, optical devices<br />

similarly capture and frame transitory phenomena. This is a terrific globe, a mid-19th century<br />

globe on a Chinese vase from the Smithsonian, quartz and that is not some weird mutant<br />

floating inside. That is literally optically captured from the collection, the Smithsonian<br />

collection, which occurs back in the room but that almost automatic snatching <strong>of</strong> things and<br />

making them present, making them there, giving them to you in all <strong>of</strong> their reality but at the<br />

same time making them hyper-real. It’s that double function that I want to stress. Just as the<br />

wundertrunk [right please] compartmentalizes the scattered bounty <strong>of</strong> the cosmos in niches<br />

and drawers to accentuate them so apparatus boxes <strong>of</strong> universe <strong>of</strong> disembodied images. This is<br />

the slide drawer to the microscope that I showed you earlier. The rush <strong>of</strong> space and time [right<br />

please] is halted for an instant in a flat and curved mirror or stalked temporarily inside the lens<br />

and slides <strong>of</strong> microscopes and telescopes letting us observe miniscule objects, right, in grand<br />

6

detail. This is from a digital high-definition microscopic camera invented by the Japanese two<br />

years ago and you notice what happens. The sharpened and concentrated visions appear doubly<br />

real and hallucinatory at the same time just as they do when you pull them into our cabinet.<br />

[Left please.] I want now to move through different kinds <strong>of</strong> instruments and to demonstrate<br />

this issue <strong>of</strong> polyopticality and what has been lost by our not remembering these functions.<br />

This is a sorcière mirror. I know you’ve never heard <strong>of</strong> it, wonderful strange mirror, part <strong>of</strong> that<br />

excess which drove the entire Baroque machinery <strong>of</strong> transcendence. In order to show you the<br />

ways in which, totally forgotten, these were glassy metaphysical devices. The Jesuit words for<br />

mirrors were “crystalline machines,” crystal machines, and they were meant to put us, for an<br />

ecstatic moment, in the presence <strong>of</strong> God. It gives a sense <strong>of</strong> an other world totally forgotten. We<br />

think that [sounds like “Greg Kirkwild”?] invented the age <strong>of</strong> the spiritual machine. Well, he<br />

did not but fantasy, religious anguish in a parade <strong>of</strong> extravagant metamorphic devices blurred<br />

the lines between the natural and the supernatural, and I should tell you we do have still an<br />

online active website which one a Weby Award. We won it in the weird category. I feel this is<br />

the acme <strong>of</strong> my career that I finally got recognized for what I ultimately am basically weird<br />

[laughter]. The Weby—actually there will be Oscars in the Internet and I can say all <strong>of</strong> this<br />

because I didn’t design it. I had a lot to do with what went into it like Vicky Porter did it and I<br />

will give you the URLs for it because all <strong>of</strong> these things—I’m sorry, not all <strong>of</strong> these things a<br />

number <strong>of</strong> things that we can reproduce on the web. [Please make it dark.] A number <strong>of</strong> things<br />

that we can reproduce on the web are interactive and the sorcière mirror is frankly one <strong>of</strong> them.<br />

So, remind me and I’ll give that to you.<br />

Now instead, we were in this baroque atmosphere <strong>of</strong> access where instead <strong>of</strong> providing a<br />

smooth repetition <strong>of</strong> outward appearance, both please, cylindrical and parametal mirrors<br />

exaggerated and tortured shapes, they thinned and thickened, fragmented and overturned<br />

regular forms, warping them beyond recognition into irregular hybrid creatures only to<br />

miraculously rescue to them again, by the deformations and monstrous transformation<br />

shimmered in the glaze catoptrics <strong>of</strong> the Jesuits <strong>of</strong> which as I said, Samarus is a wonderful<br />

example. Among the hundreds <strong>of</strong> hermetic mechanisms from the hydraulic to the magnetic<br />

devised by that natural magician Athanasius Kircher the Jesuit museum in the Collegio<br />

Romano, many were perception altering crystalline boxes. These glassy metaphysical<br />

instruments [on the right please] manipulated in ocular demonstrations ingeniously probed the<br />

hidden workings <strong>of</strong> creation and anamorphic apparatus and it goes into the realm <strong>of</strong> painting.<br />

This is a so called big [UI] lent to us by none other then Umberto Eco, I feel this is very<br />

appropriate. [UI] encrypted and decrypted information you know, this is where it used to. This<br />

is from the web but this is information. These surfaces are so dense and complex that they are<br />

literally encrypted and you need a key, a clavis to un-key it so that turning makes a difference<br />

here, whether you see it as a landscape or as a portrait. So, it’s teaching us something about<br />

the transposability <strong>of</strong> the human into the non-human and back again just as I suggested those<br />

multiple on spectacles did.<br />

This switching <strong>of</strong> the biological into the geological also occurred in the symbolic level with<br />

mirrors. Mirrors are inverting and converting machines. They rectify and perspective. How do<br />

you teach those <strong>of</strong> us who are Protestants and Catholics, who inhabit the fallen world, how do<br />

you teach the fact that all our sight is skewed? You teach it through anamorphosis but then<br />

how do you know that anybody else has an un-skewed point <strong>of</strong> view? You rectify it and<br />

suddenly one is given this vision <strong>of</strong> clarity and you are able to make an analogy to how perhaps<br />

7

God might see but we see only through a glass darkening. We see only in a distorted fashion.<br />

These mirrors are not just amusements, they teach these deep, deep principals in quite<br />

extraordinary ways.<br />

[Both please]. There is, <strong>of</strong> course also a whole industry and engineering component here. The<br />

ascent <strong>of</strong> glass in secular surroundings becomes really evident in wealthy residents proliferating<br />

throughout pre-revolutionary Europe and I want to make a distinction. These are from the<br />

Huntington Library late 18 th century but this witty, totally artificial person is a courtier—this is<br />

by Larmessin who did prints <strong>of</strong> the trades and this is a spectacle—obviously the spectacle and<br />

mirror maker but what I want to point out to you is that he is dressed in, but I want to point out<br />

how small the glass is. It’s only in the late 17 th and beginning in the 18 th century we can begin<br />

as the advertisements said to get glass as smooth and level as a pool <strong>of</strong> water because there’s a<br />

new kind <strong>of</strong> engineering and what happens? When you get glass like that then suddenly the<br />

flesh and blood occupants <strong>of</strong> Parisian salons and London drawing rooms begin to generate airy<br />

companions, <strong>of</strong> doubles, artificial persons that came and went according to the [sounds like<br />

“Bour’s”?] movements and position. [Next on the left, please.] And here is an example. This is<br />

the origin <strong>of</strong> the rear view mirror. This is a very large and very unusual claw glass that came in<br />

many different formats. This one is probably the salon and unusual because you see them from<br />

behind and the tinting also gives a kind <strong>of</strong> unification to that view. So, again in my plea for the<br />

complexity <strong>of</strong> mirrors; people say, “oh, mirrors are so boring,” you know this is repeating and<br />

think <strong>of</strong> all the theoretical drivel dismissing my [sounds like “niches”?] as simple mirroring—as<br />

if that were a simple concept. But anyway I want to point out that mirrors are not just a<br />

replicating technology. That’s what they get dismissed as but they’re taught coordinating<br />

system. They coordinate the space and you don’t necessarily just need mirrors.<br />

[Both, please.] They’re smart, we have smart furniture. If I could please—I had a whole wall, a<br />

whole wall with this kind <strong>of</strong> stuff and actually paintings by Z<strong>of</strong>fany, by Chardin that all showed<br />

the uses <strong>of</strong> reflecting everything from a Georgian dessert service which shows you both convex<br />

and concave mirrors to a bulbous chocolate urn, to [next on the right], a faceted crystal bowl<br />

where furniture—it’s kind <strong>of</strong> being big versus little science. This is kind <strong>of</strong> the little science and<br />

I’m not making this up. Until the end <strong>of</strong> the 19 th century there were wonderful books written on<br />

the [sounds like “Ouzen Metier”?] Museum in Paris, the Museum <strong>of</strong> <strong>Arts</strong> and Technology and<br />

they pointed out that they had exhibits <strong>of</strong> c<strong>of</strong>fee pots where people could look at them and like<br />

in a fun house mirror, can look at yourself in a spoon and that would teach you principals <strong>of</strong><br />

science without fancy equipment. So, again a very, very old way <strong>of</strong> using simple objects to teach<br />

rather complex topics.<br />

I want to switch again both please], take us from the realm <strong>of</strong> light into the obverse, the whole<br />

world <strong>of</strong> shadow and shade equally complex. Shadow arises from the expanding and<br />

contracting effects <strong>of</strong> light swiftly traveling over a surface and shades and it’s this connotation<br />

that we need also and certain artists Tony Oursler to certain length has gone back in the<br />

contemporary world shades are phantasms. In myth they are directly associated with death and<br />

resurrection and I have a whole section in the catalogue called, “Techniques <strong>of</strong> Epiphany”<br />

where I show really that there’s a whole other theory <strong>of</strong> the origin <strong>of</strong> the art. You know you all<br />

know the Corinthian potter, the shadow cast on the wall like this, these Montmatre ballet <strong>of</strong> the<br />

hands which themselves link back the cave painting and recent periods <strong>of</strong> the perception but<br />

there’s a whole other theory <strong>of</strong> the origin <strong>of</strong> art that’s put forward interpreting the black and<br />

red figure vases <strong>of</strong> people like Sir William Hamilton as showing you the mysteries <strong>of</strong> Eleusis<br />

8

that those religious mysteries which brought back the dead, which put the initiate into a<br />

narcotic state. Of course in the full presence <strong>of</strong> the gods that red figure were transparencies or<br />

what Sir William Hamilton called, “Transparent shows” and black figure were “Shadow shows”<br />

and the bat was <strong>of</strong> the origin <strong>of</strong> art. So, this deep sense you have it here, that’s late 19 th . It’s<br />

Hooggstraten from his famous treatise on painting where he has his students, his apprentices in<br />

the studio very simply just by casting, using a low position lantern creating this sort <strong>of</strong> primeval,<br />

hirsute satyr-like group that captures this shadow world. We have forgotten these complex<br />

connotations, this ominous spatial system beyond our control, which always lurks within<br />

shadows. [Both please.] So, I’m suggesting that all <strong>of</strong> modern projection technologies, including<br />

video, are the spectral descendants <strong>of</strong> this ancient shadow show that cast mobile silhouettes<br />

first on natural walk faces and later on muslin sheets and translucent screens. In the case <strong>of</strong><br />

Indonesia, the Balinese puppets, a distinction has to be made. These were activated, by the way<br />

by priests. It incurred an illuminated threshold and we have them exhibited that way in an<br />

apartment that was divided. The men sat facing the front, that is facing the buffalo, <strong>of</strong> hide<br />

figures that were gilt and painted. The women sat on the opposite side <strong>of</strong> the apartment and<br />

saw the gods and the heroes <strong>of</strong> legend only in shadows.<br />

[Both please.] This continued—I mean the power, if we can get the power work like Kara<br />

Walker, for example, linking up to old machine, Au Chinoise. I’m showing you a satirical print<br />

by [sounds like “Gombil”?] instead <strong>of</strong> Au Chinoise, it’s “Oeuvre Françoise” where appropriately<br />

the Chinese are sitting in the audience looking at the French disporting themselves rather than<br />

the other way around but I want to say that even in the satirical works <strong>of</strong> [sounds like<br />

“Lucissa”?] Kara Walker and her mordant caricature the use <strong>of</strong> cut-out, the use <strong>of</strong> shadow in<br />

its unnerving retains something about unnerving property that I think artists instinctively have<br />

seized about this medium that is in the history <strong>of</strong> that medium. It’s both in the future medium<br />

and in the past <strong>of</strong> it.<br />

[Both please.] I want to move this issue forward and suggest that David Hockney is quite right<br />

to see various 16 th and 17 th century lenses as having developed in part from mirrors and he’s<br />

talking particularly about the concave mirror that I showed you here, Archimedes burning<br />

mirror because these mirrors have the special, the wondrous property <strong>of</strong> projecting images as<br />

well as reflecting them. Do you remember that phantasmagoria I showed you earlier? Here you<br />

see how it actually is done with smoke and a very special kind <strong>of</strong> mirror. This amazing<br />

painterly ability to thrust the three dimensional and even extra dimensional world on to a two<br />

dimensional surface lurks behind a state <strong>of</strong> mechanized projections creating ghostly entities<br />

separate from our bodies as Tony Oursler did, I think last Halloween in and about Central<br />

Park. So, again reverting to an earlier technology and implicitly seizing some <strong>of</strong> its properties<br />

that tend to become overlooked. [Both please.] In the world <strong>of</strong> the magic lantern first referred<br />

to by the physicist, Christiaan van Huygens, was primarily used to amaze and edify in the 17 th<br />

century where figures were painted on mica or glass slides and cast from a light emitting box so<br />

as to make and I quote Huygens “to make strange things appear.”<br />

[Next on the left.] Like the wundertrunk, these popular demonstrations in here, by the way<br />

other meta-media this is very unusual. It’s quite large glass slide by the French 19 th century<br />

painter [sounds like “Juanee”?] and you’ll notice it’s a glass slide that shows a magic lantern<br />

demonstration with a demonstrator. So, it falls in this where media thinks about itself in this<br />

meta way. These magic lanterns also opened up spaces <strong>of</strong> excess, <strong>of</strong> extravagant worldly and<br />

unworldly powers. In Japan, they were called devil machines. The Japanese were quite<br />

9

fascinated with them and you can see because <strong>of</strong> the iconography, the original iconography was<br />

raised a conjuring up <strong>of</strong> scenes <strong>of</strong> hell in the atmosphere <strong>of</strong> the Reformation and the Counter-<br />

Reformation. [Both, please.} They displayed exotic flora and fauna for the stay at home, use <strong>of</strong><br />

distant lands. This is from Harvard. It was probably used in teaching the triunal microscope<br />

and I show you here a scene that would have been shown in it. These are—this is the bizarre in<br />

Kabul, Afghanistan—so that it moves out from the transcendent world to the world at large<br />

bringing home sights.<br />

[Both please.] The magic lantern however, like all <strong>of</strong> these technologies never loses traces <strong>of</strong> its<br />

ancestry and here this demonic potential that is existing in projective technologies. Look at the<br />

kind <strong>of</strong> iconography you have in a print on the left and I don’t have to remind you that Goya in<br />

his House [UI] the strange demonic grotesques. We know that after dinner, they were painted<br />

in his dining room he would take a magic lantern with no slides and simply shoot the beam,<br />

cast the beams and activate the scenes and Goya, <strong>of</strong> course was an enlightener; it fits within the<br />

iconography <strong>of</strong> the enlightenment as well. That is also revealing and deconstructing. It’s easy to<br />

laugh at things like the phantasmagoria. This is Tony Oursler who redid it for New York, a<br />

phantasmagoria. What is really important is that these were séances, musical. They hum a<br />

strange—a mount monium was used. About 40 people were locked into a black velvet draped<br />

room and demons and phantoms and the dead would be brought back. They would come like<br />

that apparition on smoke that I showed you earlier. Bear in mind this is just before and after<br />

the French Revolution when so many émigrés had gone to England, so many people had lost<br />

loved ones and desired to bring them back. This is exactly the same impulse that moved the<br />

original Madame Tussaud—and if you haven’t gone to the London Madame Tussaud you<br />

should particularly to the chambers <strong>of</strong> horrors with the death masks <strong>of</strong> Maha but where again,<br />

an attempt to bring back to life events that are almost unthinkable. So, these technologies have<br />

to be thought <strong>of</strong> in that light as a thaumaturgy and instruments for resurrection.<br />

[Both please.] This craze for boxing light as de-materialized colors, tones and shifting sites was<br />

fed by succession <strong>of</strong> room size and portable dark chambers, camera obscuras. I show you an<br />

unusual one. We have three in our show. This is a book and interestingly on the spine it says,<br />

“Theatre de l’univere,” Fear <strong>of</strong> the Universe. You just simply flip it open, you put it under your<br />

arm, a little clock pops up, you could put your head in and you have a portable camera<br />

obscuras. We had one that was again, smart piece <strong>of</strong> furniture. Salon camera obscura and we<br />

had a tent so the whole range <strong>of</strong> things. This is the thing that I would call Hockney on. He<br />

talks about it as if it’s only one kind <strong>of</strong> instrument but the camera obscura has been made so<br />

much that I only introduce it to you now because it has to be situated against all <strong>of</strong> these other<br />

[sounds like “bouls”?] and boxes with their varying environments. This is truly a cabinet meant<br />

to be seen in the dark and, if you want to make a pre-cinema analogy, here is the place to do it<br />

because in the case <strong>of</strong> the camera obscura what happens is that the world moves in color, not<br />

in black and white. The effect is dreamy. You get hovering phantoms, a sort <strong>of</strong> natural<br />

automata because it pops up on your sheet or screen with no effort. The effect is at once filmy<br />

and lucid at the same time.<br />

I want to revert again to my September 11 memory because these have been talked about by<br />

like people like Jonathan Crarey. Everything was reduced to the camera obscura and I write<br />

very much against his position. I want to take the case—this is one <strong>of</strong> the seven extent<br />

Hoogstraten boxes, this one is in Detroit—and suggest to you that what you see normally is just<br />

an anamorphic distortion and only when you look in the peephole does the world suddenly<br />

10

scream into clarity and the effect is not to control you but to reward you with that rarest <strong>of</strong><br />

visions in the fallen world, a perfect spaciously coherent artificial universe wrested from what<br />

we know to be an all too perfect world. And if I want to be an optimistic, it’s rather [sounds like<br />

“Crustian”?] because the minute you move away from the whole inside <strong>of</strong> the box, everything<br />

collapses. It has the fragility <strong>of</strong> the Madeleine, yet it is not an overall total illusion.<br />

[Both please.] These—this whole theatrical dimension—develop and I want to show you a few<br />

printed. By the way, I want to see waste paper archived in a way that we use <strong>of</strong> other media.<br />

These are waste papers and it’s interesting to read sometimes what these boxes are printed on.<br />

A pleated paper fears to be viewed with or without a box, here you can see as many as seven <strong>of</strong><br />

them. [Both please.] You can see everything. The world is now literally brought into a box, this<br />

is a Lisbon earthquake and this is [sounds like “Algamoria”?] <strong>of</strong> the Four Seasons that these<br />

boxes, which continue they have wonderful descendence. The entire Victorian Toy Theatre<br />

Thomas Mann writes about it in Budddenbrooks that has a wonderful after life <strong>of</strong> these shapes<br />

that have.<br />

[Next on the left, please.] This is a Lisbon earthquake scene and you can see how they’re<br />

arranged in the complexity <strong>of</strong> their construction. Now, to accomplish this prints older media,<br />

yet re-purposed, they have to be totally re-purposed on their fine art categories in a broader<br />

cultural applications by becoming [sounds like “nu dotique”?]. The [sounds like<br />

“Goukasken”?] which wandered in the middle class parlor from open air fairs and markets on<br />

the backs <strong>of</strong> peddlers utilized, pricked, hand colore [next on the right, please] varnished and<br />

oil etchings by the likes <strong>of</strong> [sounds like “Pernierz”?], torturing them into transparency. All<br />

these high art artists, their etchings, their engravings were taken and they were embroidered by<br />

women and children usually in kind <strong>of</strong> cotton industry; they were oiled. They were, as you can<br />

see, pricked to a folderol. This is the Royal Place in Beijing. If you flipped open the top you got<br />

the daylight scene, which I showed you a moment ago and if you had shown in the light from<br />

the back you got this kind <strong>of</strong> effect just as postcards were altered in the 19 th century for<br />

photographic albums.<br />

[Both please.] I want to show you two other categories and then I will lead into my conclusion.<br />

These commodious and episodic loosely linked collections <strong>of</strong> glowing images had no overall<br />

plot that rolled them into a single unified picture. Like camcorders, high resolution TV and<br />

video games these customized but still circumscribed do it yourself kits, prefigure the<br />

impending privatization and internalization <strong>of</strong> mass media. This is a portable diorama, the large<br />

duck air’s panorama <strong>of</strong> [sounds like “Durin Down”?] in Paris but this is again, the remediation<br />

<strong>of</strong> it. You will be interested to know that it came with pre-fabricated scenery but you were also<br />

given blank sheets to paint your own so that you can put in the customization <strong>of</strong> media. They<br />

forecast this sort <strong>of</strong> imagery, forecast the ascent <strong>of</strong> the in-house electronic sanctuary. That is<br />

more and more things brought and that became sequestered within the intimacy <strong>of</strong> your home.<br />

Like ubiquitous computing with its exaltation <strong>of</strong> the aware user and the emergence <strong>of</strong><br />

experience design in designing history, designing practice and theory, there was almost a<br />

promise <strong>of</strong> divine direct interactivity at the interface.<br />

[Both please.] By contrasting gulfing panorama looked ahead to the rise <strong>of</strong> streamlined<br />

industrial design. Jeff Wall’s Restoration here. This is the Bourbaki Panorama in Lucerne,<br />

which opened up again about a year and a half ago. It was quite extraordinary to see. Here<br />

instead <strong>of</strong> the private view you have the all view, the kind <strong>of</strong> beginning <strong>of</strong> the 19 th century wrap<br />

11

around view. By the way, here you’ll say to me, well this isn’t a wrap around view this is a very<br />

large, yes, long water color by [sounds like “Mussieri”?] which Sir William Hamilton had on<br />

the top floor <strong>of</strong> his villa in Naples but in a bow window with the window behind so that the<br />

window completed the circle. So, one medium completing another to create wrap around.<br />

[Both please.] And just to show you the range <strong>of</strong> it and also to suggest that it is weirdly related<br />

to other kinds <strong>of</strong> instruments like something you’ve never heard <strong>of</strong>. This is the zograscope that<br />

I showed you earlier which had a similar high platform, from which you looked down, giving<br />

cleaned up urban spaces, battlefields and even a child’s version. Here rolling out where you’ve<br />

had a little journey from Hamburg to its outskirts but ranges again, media with its ranges.<br />

These immersive ensembles drown the spectator in self-contained and pre-programmed<br />

ambient media insulated from the polluting, crowded physical geography <strong>of</strong> the actual<br />

manufacturing cities in which the viewers lived. Now at first blush, the relentless quest after<br />

augmenting digital technologies that insulate us from physical realities while walking us into<br />

the hyper-real must appear remote from the creaking wooden boxes, crude cardboard devices<br />

and overt apparatus <strong>of</strong> the pre-modern era. Yet a number <strong>of</strong> older and younger techno-artists<br />

are tapping into this rich repertory to escape this fate <strong>of</strong> rapidly warping computer graphics,<br />

spinning endless simulations <strong>of</strong> terrifying life like creatures are caught in violent, vivid mortal<br />

combat.<br />

[Both please.] James Turrell and we have—as part <strong>of</strong> his ongoing Arizona Crater<br />

project—produced a dream like series <strong>of</strong> three-dimensional sky scrapes that demand leisure<br />

viewing. One <strong>of</strong> the things I didn’t say is the time spent viewing, the amount <strong>of</strong> attention paid<br />

which was very gratifying also in viewers who went back and forth and through the exhibition.<br />

It’s perfect too because you notice it literally boxes blue sky so the box analogy is reminiscent<br />

<strong>of</strong> monumental coalfield paintings like those <strong>of</strong> Ellsworth Kelly. Diana Thater’s [next on the<br />

right, please] video <strong>of</strong> spotty clouds, which we put opposite the magic lanterns, from which it is<br />

a descendant evokes the meteorology <strong>of</strong> cyber space, either blank or shifting with the<br />

mounding nebulosities <strong>of</strong> electronic information and these will be my last two slides.<br />

[Next two, please.] Tiffany Holmes and I can only show you the simple game <strong>of</strong> breakout at the<br />

end but in a way in which old media can be remembered within the very fabric <strong>of</strong> the new, she<br />

created a wonderful censor based work called a_maze@getty.edu which relied on live ware. She<br />

had spy cameras which she placed in things like the book Camera Obscura and so on and she<br />

moved from the scene <strong>of</strong> Robert Irwin’s panoramic maze lying outside <strong>of</strong> the Getty which was<br />

on the screen and as you approached, it would become fractured which is what you see<br />

happening here and then the feeds reported live from people actually looking at or through<br />

some <strong>of</strong> these devices and they were captured on a plasma screen on the outside. So, that you<br />

constantly had the sense that the old was fed through the new and the new was fed through the<br />

old and they were interrelated; the viewer is always a part <strong>of</strong> the medium. There is no such<br />

thing as passive viewing and the process—she’s brilliant in it—she made us acutely aware how<br />

visual technology structures perception and how we structure visual technology,<br />

I now want to go to my conclusion. [Turn the machines <strong>of</strong>f, please.] Recently, William Gibson<br />

declared in a film—this is Mark Neil’s film <strong>of</strong> No Max For These Territories—“That the long<br />

mediated world has become a country from which we cannot find our way back to and he goes<br />

on.” I’m quoting him. I don’t think it’s possible to know what we’ve lost but there’s a pervasive<br />

sense <strong>of</strong> loss and a sense <strong>of</strong> Christmas morning at the same time. It seems to me he captures in<br />

12

a nutshell our conflicted attitude towards the artificial domains we have made. It is one <strong>of</strong> elegy<br />

and marvel, estrangement and beauty rolled into one but is it accurate history and I return to<br />

Maryhelen’s opening remark. Was there ever a past free <strong>of</strong> optical technology given the fact<br />

that the eye was the first tool extending humans beyond the outer edge <strong>of</strong> their body? What I’ve<br />

tried to do this afternoon is to undo our forgetfulness by recognizing that visual technologies<br />

are both discreet implements thriving with a specific historical context and interrelated events<br />

that become layered and superimposed with time and I want to give Arnheim and Wogart the<br />

last word. Instead <strong>of</strong> extravagant fictions breaking out <strong>of</strong> the monitor to merge symbiotically<br />

with reality, which is what has always held before us the VR experience as the nonplusultra <strong>of</strong><br />

simulacra simulation, so called older legacy applications, all this stuff I’ve been showing you,<br />

which one wants to simply to shove in the legacy category, possessed modest gifts <strong>of</strong><br />

compression and intensification that were as limited, impermanent and mysterious as life<br />

reformulating Abby Warberg’s insight that I quoted at the beginning <strong>of</strong> this paper. I’d like to<br />

suggest that those older technologies enhanced the total person at the sensory, memory,<br />

imaginative and cognitive levels. Something we desperately need today. Thank you.<br />

Dr. Hendricks: Are there any questions for Dr. Stafford or are we prepared for the other room?<br />

None? Yes, there must be.<br />

Question: A very small question. That scroll <strong>of</strong> the long . . .<br />

Dr. Stafford: The Hamburg?<br />

Question: Yeah, how big is that?<br />

Dr. Stafford: That is a very good question and I would have to look at the catalogue. In the<br />

installation shot, there was the Jeff Wall Restoration, there was a long, long vitrine which did<br />

not enroll it fully. It probably goes on for about a mile. It’s just enormous, and on the other<br />

side—given by the London Daily News with your subscription—an unfurling, hand panorama <strong>of</strong><br />

the Great Exposition, which is brilliant. It’s a chromolithograph and you have the little viewers<br />

up on top, the wonderful Crystal Palace and then all <strong>of</strong> the installations, all <strong>of</strong> the exhibitions<br />

rolled by you, labeled. Then there’s this great cartographical orientation thing too so that—but<br />

that one is about this high whereas the [sounds like “Chilo’s”?] one from Hamburg which just<br />

shows the day trip from Hamburg to its outskirts. Hamburg, <strong>of</strong> course, is a sailor’s town, you go<br />

by four brothels and then you go past a . . .<br />

Question: Those are labeled?<br />

Dr. Stafford: Those are labeled, yes, and then you go and there’s a little panorama building.<br />

There’s a diorama <strong>of</strong> the building so all <strong>of</strong> the—again this media incorporating other media so<br />

it’s really quite, quite wonderful and very detailed. [sounds like “Franter Ech”?] who does<br />

short essays, I do the big long introductory one when Fran does beautiful short essays, does one<br />

specifically on that and tells you all the scenes and their [sounds like “abrobouts”?] and all<br />

sorts <strong>of</strong> fairs and so on. So, yes they’re quite . . .<br />

Question: Another short question having to do with that, how were they meant to be read?<br />

Dr. Stafford: How do you mean? How do you mean “reading”?<br />

13

Question: I mean, if I were the user would I enroll it and—what was involved with memory <strong>of</strong><br />

the image before and then where you’re getting to?<br />

Dr. Stafford: You would never unroll the whole thing all at once. I mean it’s useful actually and<br />

do we cite many examples say from [sounds like “Norvels”?] or from the period where you get<br />

a sense <strong>of</strong> how they’re used but you would never unfold them. You would probably unfold<br />

them about this much. In other words and you’d get a scene and then you would just keep on<br />

going. There are other things. You see I had to throw so much out that go along with it,<br />

puzzles, wonderful puzzles at the same time where you get, for example metamorphic. I left out<br />

the whole metamorphic section, landscapes where you would create your own quite literally<br />

that you get a box <strong>of</strong> pieces the horizon line is the same but you could put them together in a<br />

way. So, that this whole notion <strong>of</strong> new ability and what we think <strong>of</strong> choosing you know but I<br />

mean choosing <strong>of</strong> course within parameters obviously under a certain limit that’s there but<br />

that’s connected in a way to your question. The medium has stretched but it suggests to you<br />

how far you unfurl it. In other words, you can unfurl it, people look at all <strong>of</strong> your four brothels<br />

you know and go on. But I mean it’s very human in its dimension and also that’s a child’s so<br />

that the level <strong>of</strong> detail is quite different or the stretch if I could put it, is different from if you<br />

just walked around the corner, not around the corner, around the edge and looked at the Great<br />

Exposition one which was meant for adults. So you know that kind <strong>of</strong> tailoring. Just like the<br />

little infant’s cabinet is literally meant for a child’s hand.<br />

Question: I was wondering if that journey to Hamburg could be used in a Zoetrope or<br />

something? You know a spinning toy and have more <strong>of</strong> a sense <strong>of</strong> a journey. Is that where that<br />

question is going?<br />

Dr. Stafford: I don’t know. That’s a different medium. You see that’s a different—one could say<br />

that’s a different technology. No, because in Zoetrope it’s repetitive. You see what’s interesting<br />

about these, these don’t repeat the scenes, they’re quite different. In other words, in the sense<br />

that it is a journey, you’re going from Hamburg to Altoona. In the universal exposition it’s a<br />

little bit different, and the thing that’s amazing is that you can enter it anywhere. We arbitrarily<br />

opened it in the middle; we could have unrolled it at the end just so you would see the amount<br />

<strong>of</strong> roll that was left on the left and the right, here that we couldn’t unroll. Otherwise we’d need<br />

you know to wrap it around the museum but the Zoetrope that’s rather different because there<br />

are certain images there that are repeated. What it’s closer to—do you remember the blow book<br />

that I showed you where certain images were repeated? I’m sorry, I really compressed so much,<br />

but in the blow book there are sets <strong>of</strong> images. There are nuns, there are different kinds <strong>of</strong><br />

images then there are blank sheets <strong>of</strong> paper, then you get them again and <strong>of</strong> course, what the<br />

charlatan does is amazing; he makes them disappear i.e., the blank pages and then suddenly<br />

down the pike he makes them reappear again. So, that’s a little bit closer to the Zoetrophic<br />

experience.<br />

Question: I guess I was thinking that Jeff Wall in a way—it’s sort <strong>of</strong> like that trip to Hamburg.<br />

You put it in a large enough spinning theatre and you have kind <strong>of</strong> a resistance, resistance <strong>of</strong><br />

vision and screen in between, that might be a sort <strong>of</strong> moving picture as well and it pre-figured<br />

the movies.<br />

14

Dr. Stafford: Well, I’m trying really hard. I see where you’re going with this but no, I mean it’s<br />

an interesting thing what you’re saying but I’m trying to point out some differences here. This<br />

has to do with the polyopticality. I don’t want to go, I’m resisting this pre-figure although <strong>of</strong><br />

course what did I say with camera obscura, that, <strong>of</strong> course, certain things in certain ways prefigure<br />

but they do so much more than pre-figuration. They are about so much more.<br />

Question: Did you look at all the finding connections with sound processing technologies? I<br />

mean I’m vaguely aware <strong>of</strong> sort <strong>of</strong> free electric music and stuff.<br />

Dr. Stafford: You know, [sounds like “Atanasus Cuhrer”?] I mean again that I threw out<br />

because I was really trying to hit the mirror business but you know he invented—he was quite<br />

amazing. He invented all sort <strong>of</strong> crucible instruments. Actually there’s a guy in Germany now<br />

who has tried to put some <strong>of</strong> his music, these strange sounds <strong>of</strong> the universe. I have a disc, I<br />

should have brought it along and played it to you. Cuhrer also invented a device for over<br />

hearing secret conversations, very baroque, very contemporary, but the musical dimension is an<br />

interesting thing. It’s clear in the phantasmagoria, everybody writes about the weird wail <strong>of</strong> the<br />

harmonica. That is in everything so sort <strong>of</strong> coordinate those and there are other examples as<br />

well. I have not myself personally gotten so deeply into that but surely that is a very good<br />

question because these are really sensory scenarios and you’re quite right. Smells you know,<br />

smells were unleashed you know like the smoke. We have descriptions <strong>of</strong> that plus all the<br />

people fainting, hallucinating, screaming all sorts <strong>of</strong> things like that going on. So, it’s quite a<br />

process but thank you for raising your question.<br />

Question: You gave us this wonderful background on the entertainment, artistic and scientific<br />

uses. Were these early optical devices used for surveillance as well?<br />

Dr. Stafford: For surveillance—well I just gave the example <strong>of</strong> Cuhrer.<br />

[Overlapping Voices]<br />

Dr. Stafford: For spying you mean for spying? Yes, yes.<br />

Question: Or for in terms <strong>of</strong> control like observing prisoners or students.<br />

Dr. Stafford: No but . . .<br />

[Overlapping Voices]<br />

Dr. Stafford: Actually in my Artful Science when I first got involved in all this; it’s a long, long<br />

love affair. Your question reminds me <strong>of</strong> something. You have to understand that particularly<br />

as time went on—let’s say by the time you hit the 18 th century—there are also all <strong>of</strong> these books<br />

that appear and I’m thinking <strong>of</strong> one book now to answer your question [sounds like “Ed<br />

Mackioltz”?] eight volumes, well it depends whether it’s in court or [Indecipherable] but<br />

anyway make your own and there are sections in there that say, if you want to spy on your lover<br />

like you can imagine some <strong>of</strong> these myriad things. Those are great. Yes, they’re quite witty and<br />

funny and excruciatingly comely. I’ve been thinking how in the hell would I make this thing?<br />

But it tells you, first you do this, then you find the closet, then you do that, but be sure to drill<br />

the hole here and then there has to be—so, there is that, there is that dimension. Now, whether<br />

it was used—now we know, for example anamorphic the thing that’s interesting—see nobody’s<br />

really studied—iconography as well that’s what I think is really important as well even if you go<br />

back to anamorphic images from the 16 th century keeping things whole bind. Of course, the<br />

15

eligious dimension here is quite clear but there were prints that were made at the same time<br />

that inlayed in the landscape the portraits <strong>of</strong> [sounds like “Francois Premiere”?] for example so<br />

the political. Already the notion that you have to hide, which means that you have to reveal,<br />

which then suggests that maybe some <strong>of</strong> these instruments, not just parametal mirrors and so<br />

on would have been used that way but I don’t have any evidence other than this later stuff. It’s<br />

a good question. That’s a good question. I guess—a little bit what you want.<br />

Question: Hi, I have one question. With regard to David Hockney’s secret knowledge and your<br />

exhibition, a recent symposium at NYU on Kircher.<br />

Dr. Stafford: On what?<br />

Question: On Kircher, which was fabulous.<br />

Dr. Stafford: I bet! Yes, we had it. I was in Stamford but that’s a dog and pony show. I was in<br />

the Stamford one. Right, I couldn’t go to NYU. Thanks.<br />

Question: The question that was raised was whether all <strong>of</strong> this interest in the pre-modern right<br />

now is an antidote to post-modernism. So, can you just comment about secret knowledge as<br />

being a way to change the conversation?<br />

Dr. Stafford: You know in one way David Hockney is absolutely right about the camera<br />

obscura. Let me just say that up front. On the other hand, I think his argument is narrow just as<br />

what I read and I was not here for all the big hoop-la report in the New York Times. When was<br />

it, about a year ago? You know, Suzanne Sontag saying that—I’ll never forget this—if Vermeer<br />

had used the camera obscura it would have been like all the great lovers <strong>of</strong> history using<br />

Viagra. I remember that statement. I thought that was low—unless the New York Times skewed<br />

it somehow—I thought both parties missed the relevance <strong>of</strong> this and I’m not saying that I’m a<br />

great holder <strong>of</strong> truth but it seems to me these technologies I am interested in. I’m interested in<br />

them because, as a teacher who studies the past, I also deal with very contemporary media: how<br />

can I make the past speak to the present? This is not about nostalgia for me, so I have to<br />

explain that. To me it’s part <strong>of</strong> a larger project about rethinking the past. Okay, now your point.<br />

I don’t think we can just reduce it to that. I can only say why I am really interested in<br />

recuperating this and enriching our technological landscape. I put it that way and I have been<br />

for a long, long time. I mean I’ve been doing this since Body Criticism where I was talking<br />

about MRI and cat scans. David Hockney has a—I don’t know—I think he has a separate agenda<br />

but I think he’s right but I don’t think he’s necessarily right. He kind <strong>of</strong> throws it up when they<br />

attacked him and he said, oh well you know, these are much more than artists’ aids. I think<br />

that’s my bottom line. These are much more than artists’ aids. The best thing about our<br />

contemporary technology is that they’re much more than just about simulation. There’s a lot<br />

more going on and that’s what I meant at the beginning. We have to get at the level <strong>of</strong> desire.<br />

What’s a desire that doesn’t get satisfied? It kind <strong>of</strong> goes on and on and I think something<br />

religious. Thank you. It’s a very rich and difficult question.<br />

Dr. Hendricks: I think that’s it. Thank you very much.<br />

[Applause]<br />

16

CROSS DISCIPLINARY STRATEGIES TO RECREATE AND REMEMBER: ONE<br />

PAINTER’S LOOK AT HOW MEMORIES CAN BE CAPTURED AND PLAY A<br />

CENTRAL ROLE IN STUDIO PRACTICE<br />

Judith Brassard Brown<br />

Montserrat College <strong>of</strong> Art<br />

With the advent <strong>of</strong> photography, practitioners in the arts and sciences were quick to use the<br />

medium in their particular fields. <strong>Visual</strong> artists had a new art form. Additionally, painters<br />