Blanch It, Mix It, Mash It - Thomas M. Cooley Law School

Blanch It, Mix It, Mash It - Thomas M. Cooley Law School

Blanch It, Mix It, Mash It - Thomas M. Cooley Law School

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

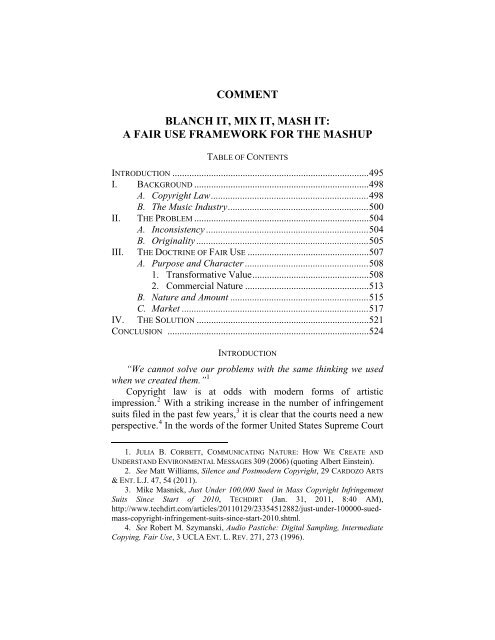

COMMENT<br />

BLANCH IT, MIX IT, MASH IT:<br />

A FAIR USE FRAMEWORK FOR THE MASHUP<br />

TABLE OF CONTENTS<br />

INTRODUCTION ................................................................................. 495<br />

I. BACKGROUND ........................................................................ 498<br />

A. Copyright <strong>Law</strong> ................................................................. 498<br />

B. The Music Industry .......................................................... 500<br />

II. THE PROBLEM ........................................................................ 504<br />

A. Inconsistency ................................................................... 504<br />

B. Originality ....................................................................... 505<br />

III. THE DOCTRINE OF FAIR USE .................................................. 507<br />

A. Purpose and Character ................................................... 508<br />

1. Transformative Value ................................................ 508<br />

2. Commercial Nature ................................................... 513<br />

B. Nature and Amount ......................................................... 515<br />

C. Market ............................................................................. 517<br />

IV. THE SOLUTION ....................................................................... 521<br />

CONCLUSION ................................................................................... 524<br />

INTRODUCTION<br />

“We cannot solve our problems with the same thinking we used<br />

when we created them.” 1<br />

Copyright law is at odds with modern forms of artistic<br />

impression. 2 With a striking increase in the number of infringement<br />

suits filed in the past few years, 3 it is clear that the courts need a new<br />

perspective. 4 In the words of the former United States Supreme Court<br />

1. JULIA B. CORBETT, COMMUNICATING NATURE: HOW WE CREATE AND<br />

UNDERSTAND ENVIRONMENTAL MESSAGES 309 (2006) (quoting Albert Einstein).<br />

2. See Matt Williams, Silence and Postmodern Copyright, 29 CARDOZO ARTS<br />

& ENT. L.J. 47, 54 (2011).<br />

3. Mike Masnick, Just Under 100,000 Sued in Mass Copyright Infringement<br />

Suits Since Start of 2010, TECHDIRT (Jan. 31, 2011, 8:40 AM),<br />

http://www.techdirt.com/articles/20110129/23354512882/just-under-100000-suedmass-copyright-infringement-suits-since-start-2010.shtml.<br />

4. See Robert M. Szymanski, Audio Pastiche: Digital Sampling, Intermediate<br />

Copying, Fair Use, 3 UCLA ENT. L. REV. 271, 273 (1996).

496 THOMAS M. COOLEY LAW REVIEW [Vol. 28:3<br />

Justice George Sutherland, “while the meaning of constitutional<br />

guaranties never varies, the scope of their application must expand or<br />

contract to meet the new and different conditions which are<br />

constantly coming within the field of their operation. In a changing<br />

world, it is impossible that it should be otherwise.” 5 To ensure that<br />

the purpose of copyright—”[t]o promote the Progress of Science and<br />

useful Arts” 6 —is never varied, we must adhere to Justice<br />

Sutherland’s principle when addressing the issue before us. 7<br />

The advent of the digital age has brought many developments in<br />

the music industry. Digital sampling 8 is exceedingly prevalent on the<br />

scene; 9 in fact, sampling technology that was only available in the<br />

studio is now affordable for the everyday consumer. 10 Additionally,<br />

the Internet provides unauthorized and unfettered access to nearly the<br />

entire history of recorded music to those who seek it. 11 As a result,<br />

not only is it now possible to manipulate an infinite collection of<br />

copyrighted music, but we must also consider what an ordinary use<br />

for copyrighted music is. 12 As this sampling practice becomes more<br />

commonplace in the music industry, our notions of “popular music”<br />

will also be tested. 13<br />

5. Vill. of Euclid v. Ambler Realty Co., 272 U.S. 365, 387 (1926).<br />

6. U.S. CONST. art. I, § 8, cl. 8.<br />

7. Euclid, 272 U.S. at 387.<br />

8. See discussion infra Part II B.<br />

9. See A. Dean Johnson, Comment, Music Copyrights: The Need for an<br />

Appropriate Fair Use Analysis in Digital Sampling Infringement Suits, 21 FLA. ST.<br />

U. L. REV. 135, 135 (1993) (citing Richard Harrington, The Groove Robbers’<br />

Judgment: Order on ‘Sampling’ Songs May Be Rap Landmark, WASH. POST, Dec.<br />

25, 1991, at D1, D7).<br />

10. See Reuven Ashtar, Theft, Transformation, and the Need of the Immaterial:<br />

A Proposal for a Fair Use Digital Sampling Regime, 19 ALB. L.J. SCI. & TECH.<br />

261, 284 (2009).<br />

11. See Emily Harper, Note, Music <strong>Mash</strong>ups: Testing the Limits of Copyright<br />

<strong>Law</strong> as Remix Culture Takes Society by Storm, 39 HOFSTRA L. REV. 405, 405<br />

(2010) (citing Edward Lee, Developing Copyright Practices for User-Generated<br />

Content, J. INTERNET L., July 2009, at 1, 13).<br />

12. See <strong>Law</strong>rence Lessig, Free(ing) Culture for Remix, 2004 UTAH L. REV.<br />

961, 968 (2004).<br />

13. Ashtar, supra note 10, at 301 (citing JOANNA DEMERS, STEAL THIS MUSIC:<br />

HOW INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY LAW AFFECTS MUSICAL CREATIVITY 8–9 (2006)).

2011] FAIR USE FRAMEWORK 497<br />

“A perfection of means, and confusion of aims, seems to be our<br />

main problem.” 14<br />

At the current juncture, “the law is widely dissociated from the<br />

social norm.” 15 As this sampling practice becomes more widespread,<br />

the disparity between law and practice becomes more apparent. 16<br />

There is such a great discrepancy between what copyright deems<br />

legal and what the public demands that our society is considered by<br />

some to be “‘a nation of infringers.’” 17 As it is currently applied,<br />

copyright law is not suitable for the reality of our time. 18 The digital<br />

age in which we live must eventually face the letter of the law. When<br />

that time comes, copyright law must stand down and “‘adapt to this<br />

new technology, as it has in the past, to foster, rather than inhibit, its<br />

benefit to society.’” 19 Our technology has again brought us to that<br />

time. “When technological change has rendered its literal terms<br />

ambiguous, the Copyright Act must be construed in light of this basic<br />

purpose.” 20 “Yet copyright law has not been amended or adjusted to<br />

keep pace with these technological changes.” 21<br />

14. PAUL F. PLOUTZ, GLOBAL WARMING: HANDBOOK OF ECOLOGICAL ISSUES<br />

320 (2011) (quoting Albert Einstein).<br />

15. Megan M. Carpenter, Space Age Love Song: The <strong>Mix</strong> Tape in a Digital<br />

Universe, 11 NEV. L.J. 44, 79 (2010).<br />

16. See Ashtar, supra note 10, at 268.<br />

17. Michael Katz, Recycling Copyright: Survival & Growth in the Remix Age,<br />

13 INTELL. PROP. L. BULL. 21, 40 (2008) (quoting Nate Anderson, Overly-broad<br />

Copyright <strong>Law</strong> has Made USA a “Nation of Infringers,” ARS TECHNICA (Nov. 19,<br />

2007, 1:01 PM), http://arstechnica.com/news.ars/post/20071119-overly-broadcopyright-law-has-made-us-a-nation-of-infringers.html).<br />

18. See Carpenter, supra note 15, at 79.<br />

19. Katz, supra note 17, at 40 (quoting <strong>Thomas</strong> David Kehoe, How Experts<br />

Fail: The Patterns and Situations in Which Experts Are Less Intelligent than Non-<br />

Experts, Paradigm Shifts and Profound Stupidity (Aug. 10, 2007),<br />

http://www.howexpertsfail.com).<br />

20. Twentieth Century Music Corp. v. Aiken, 422 U.S. 151, 156 (1975) (The<br />

“basic purpose” stated is “to stimulate artistic creativity for the general public<br />

good.” Id.) (citing Fortnightly Corp. v. United Artists Television, Inc., 392 U.S.<br />

390, 395–96 (1968)). “[T]his is a statute that was drafted long before the<br />

development of the electronic phenomena . . . . We must read the statutory<br />

language of 60 years ago in the light of drastic technological change.” Id.<br />

(citing Fortnightly Corp., 392 U.S. at 395–96).<br />

21. Katz, supra note 17, at 38.

498 THOMAS M. COOLEY LAW REVIEW [Vol. 28:3<br />

Thus, we approach a legal crossroads—one that may transform<br />

more than just the music industry. 22 This Article expounds on the<br />

legality of the mashup 23 under copyright law. Primarily, it proposes a<br />

fair use framework to be applied in the event that a mashup artist is<br />

sued for copyright infringement. The mashup may very well be the<br />

turning point of our time, and if not handled with great care, then the<br />

outcome could agitate the growth of our culture in more ways than<br />

one.<br />

Part II of this Article provides a brief glimpse into copyright law<br />

and the fair use doctrine, and it presents some information about the<br />

music industry and the popular art forms that thrive in it today. Part II<br />

also details two major concerns regarding the application of the fair<br />

use analysis. Part III addresses some major concerns revolving<br />

around recent applications of fair use. Part IV then takes a step-bystep<br />

approach to the fair use doctrine. In doing so, this section<br />

attempts to provide support for the mashup as a creature of<br />

appropriation that is above that of sampling. Part V demonstrates that<br />

amending the Copyright Act to solve our problems is not the most<br />

effective solution. A change in focus not only provides instantaneous<br />

results but also contains the forward thinking required to make a<br />

lasting change. Finally, Part VI combines these illustrations and<br />

reinforces the goal of copyright as the infrastructure upon which this<br />

Article’s framework stands.<br />

I. BACKGROUND<br />

A. Copyright <strong>Law</strong><br />

Copyright law stems from the same document that rooted our<br />

nation. The Copyright Clause contained within the Constitution of<br />

the United States gives Congress the power “[t]o promote the<br />

Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to<br />

Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective<br />

Writings and Discoveries.” 24 Copyright law grants the copyright<br />

owner the exclusive right to create “derivative works based upon the<br />

22. See Harper, supra note 11, at 408 (citing Mongillo, infra note 50, at 3)<br />

(“[T]here is great uncertainty surrounding the legality of mashups because courts<br />

have not yet addressed the matter.”Id.).<br />

23. See infra text accompanying note 40.<br />

24. U.S. CONST. art. I, § 8, cl. 8.

2011] FAIR USE FRAMEWORK 499<br />

copyrighted work.” 25 Thus, an artist who wishes to utilize the work<br />

of another must obtain a license from the original artist. 26 With<br />

excessive licensing fees, average artists may be faced with either<br />

deserting their art or breaking the law. 27 However, in 1976, Congress<br />

incorporated the fair use doctrine into the Copyright Act for the first<br />

time. 28 The Act recognized that a successful fair use defense is a<br />

complete defense to a claim of infringement: 29<br />

Notwithstanding the provisions of sections 106 and<br />

106A, the fair use of a copyrighted work, including<br />

such use by reproduction in copies or phonorecords or<br />

by any other means specified by that section, for<br />

purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting,<br />

teaching (including multiple copies for classroom<br />

use), scholarship, or research, is not an infringement<br />

of copyright. In determining whether the use made of<br />

a work in any particular case is a fair use the factors to<br />

be considered shall include (1) the purpose and<br />

character of the use, including whether such use is of a<br />

commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational<br />

purposes; (2) the nature of the copyrighted work; (3)<br />

the amount and substantiality of the portion used in<br />

relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and (4)<br />

the effect of the use upon the potential market for or<br />

value of the copyrighted work. The fact that a work is<br />

unpublished shall not itself bar a finding of fair use if<br />

such finding is made upon consideration of all the<br />

above factors. 30<br />

The fair use doctrine insists upon a lax view “‘of the copyright<br />

statute when, on occasion, it would stifle the very creativity which<br />

25. 17 U.S.C. § 106(2) (2006).<br />

26. See id.<br />

27. See Harper, supra note 11, at 437–38 (citations omitted).<br />

28. H.R. REP. No. 94-1476, at 65 (1976), reprinted in 1976 U.S.C.C.A.N.<br />

5659, 5678.<br />

29. Abilene Music, Inc. v. Sony Music Entm’t, Inc., 320 F. Supp. 2d 84, 88<br />

(S.D.N.Y. 2003).<br />

30. 17 U.S.C. § 107 (emphasis added).

500 THOMAS M. COOLEY LAW REVIEW [Vol. 28:3<br />

that law is designed to foster.’” 31 In that way, the statute was drafted<br />

to be malleable and “to accommodate periods ‘of rapid technological<br />

change.’” 32 Therefore, bright-line rules will not suffice for a fair use<br />

analysis; the statute “calls for [a] case-by-case analysis.” 33 Fair use<br />

should not be seen as an exception to the exclusive rights of the<br />

copyright owner, but rather as a fundamental aspect of copyright<br />

law. 34 If fair use is to be “bent to the service of copyright,” 35 then the<br />

very purpose of copyright is lost; a purpose that should be at the heart<br />

of every fair use decision. Therefore, copyright “must step aside in<br />

favor of fair use,” 36 because fair use is indispensible “to fulfill<br />

copyright’s very purpose.” 37<br />

B. The Music Industry<br />

Sampling occurs when an artist detaches certain portions of a<br />

recording and utilizes them in a new work. 38 The circuits are split on<br />

how best to handle a minimal use of sampling in audio recordings. 39<br />

However, this Article goes far beyond a minimal use of sampling and<br />

into the realm of the mashup. An audio mashup “is a type of<br />

sampling that ‘[t]ypically consist[s] of a vocal track from one song<br />

31. Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc., 510 U.S. 569, 577 (1994) (quoting<br />

Stewart v. Abend, 495 U.S. 207, 236 (1990) (citation omitted)).<br />

32. Johnson, supra note 9, at 145 (quoting H.R. REP. NO. 94-1476, at 5680).<br />

33. Campbell, 510 U.S. at 577 (citing Harper & Row, Publishers, Inc. v. Nation<br />

Enters., 471 U.S. 539, 560 (1985)).<br />

34. Pierre N. Leval, Toward a Fair Use Standard, 103 HARV. L. REV. 1105,<br />

1107 (1990).<br />

35. David Lange & Jennifer Lange Anderson, Copyright, Fair Use and<br />

Transformative Critical Appropriation 149 (2001) (unpublished essay) (on file with<br />

the Conference on the Public Domain at the Duke <strong>Law</strong> <strong>School</strong>), available at<br />

http://www.law.duke.edu/pd/papers/langeand.pdf.<br />

36. Lange & Anderson, supra note 35, at 149 (emphasis added).<br />

37. See Campbell, 510 U.S. at 575.<br />

38. See Szymanski supra note 4, at 275–76 (citing E. Scott Johnson, Protecting<br />

Distinctive Sounds: The Challenge of Digital Sampling, 2 J.L. & TECH. 273 (1987);<br />

R. Sugarman & J. Salvo, Sampling Gives <strong>Law</strong> a New <strong>Mix</strong>; Whose Rights?, NAT’L<br />

L.J., Nov. 11, 1991, at 1).<br />

39. Compare Newton v. Diamond, 388 F.3d 1189 (9th Cir. 2003) (holding that<br />

the sampling of a segment of three notes from a composition was de minimis), with<br />

Bridgeport Music, Inc. v. Dimension Films, 410 F.3d 792, 801, 803, 805 (6th Cir.<br />

2005) (taking a “literal reading” approach to the “interpretation of the copyright<br />

statute” and holding that any sampling is infringement.) (“Get a license or do not<br />

sample.” Id.).

2011] FAIR USE FRAMEWORK 501<br />

digitally superimposed on the instrumental track of another.’” 40<br />

Unlike the sampling artists who attempt to slyly dissolve the sample<br />

into a new work, the mashup artist is not attempting to “hide the<br />

authorship of the prior recordings, nor claim them as his own<br />

work.” 41 Although the practice of mashing could be seen as lacking<br />

creativity, 42 it is the product of this process that conceals the true<br />

creative engineering. 43<br />

Whether in a mashup or remix, sampling is so prevalent in the<br />

music industry that many see it as vital to our music culture. 44<br />

Notwithstanding the various infringement suits filed against sampling<br />

artists, the genre gains popularity at an ever-increasing pace. 45 For<br />

example, in 2005, a mashup album containing the work of the artists<br />

Jay-Z and Linkin Park made the Billboard Top Ten. 46 Billboard.com<br />

also hosts <strong>Mash</strong>up Mondays, in which a mashup and mashup artist<br />

are featured each week. 47 An even more impressive example is<br />

Danger Mouse’s The Grey Album, a mashup album created from Jay-<br />

Z’s The Black Album and The Beatles’s White album. 48 More than<br />

100 million tracks were downloaded in one day, making it the largest<br />

single-day download in history. 49 Although this style of music seems<br />

to exceed the boundaries of what is typical, 50 repurposing decades of<br />

40. Aaron Power, 15 Megabytes of Fame: A Fair Use Defense for <strong>Mash</strong>-ups as<br />

DJ Culture Reaches <strong>It</strong>s Postmodern Limit, 35 SW. U. L. REV. 577, 579 (2007)<br />

(alterations in original) (quoting Pete Rojas, Bootleg Culture, SALON (Aug. 1,<br />

2002, 3:30 PM), http://archive.salon.com/tech/feature/2002/08/01/bootlegs).<br />

41. Id. at 585.<br />

42. See Harper, supra note 11, at 410–11.<br />

43. See Power, supra note 40, at 589 (stating that the aim of the mashup is to<br />

“retain as much as possible from the original works so that the combination seems<br />

natural”).<br />

44. Szymanski, supra note 4, at 278 (citing Howard Reich, Send in the Clones,<br />

The Brave New Art of Stealing Musical Sounds, CHI. TRIB., Feb. 15, 1987, at 8).<br />

45. See Harper, supra note 11, at 410 (citing Power, supra note 40, at 583,<br />

586).<br />

46. See Katz, supra note 17, at 32.<br />

47. BILLBOARD, www.billboard.com/column/mashupmondays (last visited<br />

Nov. 20, 2012).<br />

48. See Power, supra note 40, at 580 (citing Rob Walker, The Grey Album,<br />

N.Y. TIMES MAGAZINE, Mar. 21, 2004, at 32).<br />

49. Id. at 580–81.<br />

50. See David Mongillo, The Girl Talk Dilemma: Can Copyright <strong>Law</strong><br />

Accommodate New Forms of Sample-Based Music?, 9 U. PITT. J. TECH. L. &<br />

POL’Y, Spring 2009, at 3.

502 THOMAS M. COOLEY LAW REVIEW [Vol. 28:3<br />

music that span a multitude of genres has “created a new and<br />

enduring form of music.” 51<br />

Living in what some call a remix culture, 52 society relishes<br />

“appropriation as a means of critical expression.” 53 Even with the<br />

myriad of infringement suits filling the dockets, this art form gains<br />

appreciation at a bristling pace. 54 Therefore, the courts would be wise<br />

to heed the words of former United States Supreme Court Justice<br />

Oliver Wendell Holmes:<br />

<strong>It</strong> would be a dangerous undertaking for persons<br />

trained only to the law to constitute themselves final<br />

judges of the worth of pictorial illustrations, outside of<br />

the narrowest and most obvious limits. At the one<br />

extreme, some works of genius would be sure to miss<br />

appreciation. Their very novelty would make them<br />

repulsive until the public had learned the new<br />

language in which their author spoke. 55<br />

Ergo, the “law cannot, and should not, dictate the norms of art.” 56<br />

Because the mashup has not yet been ruled on, there is concern that<br />

the law will dictate the norm of this art form. There is a high<br />

likelihood that the mashup will be shuffled in with cases interpreting<br />

digital sampling. Although the mashup is technically a form of digital<br />

sampling, it should instead be affiliated with appropriation art.<br />

Appropriation has been described as many things: a language; 57<br />

an allegorical mechanism; 58 and, most importantly, a movement. 59<br />

51. Johnson, supra note 9, at 138.<br />

52. Emily Meyers, Art on Ice: The Chilling Effect of Copyright on Artistic<br />

Expression, 30 COLUM. J.L. & ARTS 219, 236 (2007) (quoting Marjorie Heins and<br />

Tricia Beckles, Will Fair Use Survive? Free Expression in the Age of Copyright—<br />

A Public Policy Report, at 3 (2005), available at http://www.fepproject.org/<br />

policyreports/WillFairUseSurvive.pdf).<br />

53. Mary W.S. Wong, “Transformative” User-Generated Content in Copyright<br />

<strong>Law</strong>: Infringing Derivative Works or Fair Use?, 11 VAND. J. ENT. & TECH. L.<br />

1075, 1111 (2009).<br />

54. Id.<br />

55. Bleistein v. Donaldson Lithographing Co., 188 U.S. 239, 251 (1903).<br />

56. Xiyin Tang, That Old Thing, Copyright . . . : Reconciling the Postmodern<br />

Paradox in the New Digital Age, 39 AIPLA Q.J. 71, 72 (2011).<br />

57. Roxana Badin, An Appropriate(d) Place in Transformative Value:<br />

Appropriation Art’s Exclusion from Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc., 60<br />

BROOK. L. REV. 1653, 1656 (1995).<br />

58. Id. at 1660.

2011] FAIR USE FRAMEWORK 503<br />

Appropriation focuses on the selection and removal of another<br />

artist’s material and subsequent inclusion into a new creation. 60 “[T]o<br />

appropriate is to challenge, to expose, and thus to transcend the<br />

conceits and boundaries of the past, thereby gaining insight into what<br />

was unacknowledged or opaque.” 61 This art form “assume[s] a<br />

deliberate role in the transmission of [our] culture.” 62 Appropriation<br />

is the instrument with which the artist can combat this mass-media<br />

driven world in which we live. 63 <strong>It</strong> confronts the ideals of our past<br />

and forces the audience to see them in a new light. 64 Accordingly,<br />

appropriation “liberates us from [the] constructs” 65 of what is known<br />

by recontextualizing what would otherwise be familiar. 66 Thus, to<br />

fully appreciate the final work one must imagine the appropriated<br />

portion in its original context as well as the context in which it has<br />

been placed by the mashup artist. 67<br />

A common form of appropriation is collage, which creates a “new<br />

combination, use, or assemblage of existing works.” 68 Collage is not<br />

seen only in the visual-art world; many view digital sampling as a<br />

form of collage. 69 Like the visual artist, the sampling artist removes<br />

segments from recordings and “piece[s] them together into song<br />

collages.” 70 “Arguably, the whole point of such sampling is to<br />

dislocate the sound fragment from its initial context, and thereby to<br />

empty the sample of its former meaning by infusing it with a new<br />

59. Rachel Isabelle Butt, Appropriation Art and Fair Use, 25 OHIO ST. J. ON<br />

DISP. RESOL. 1055, 1059–60 (2010).<br />

60. Id. (citing Patricia Krieg, Copyright, Free Speech, and the Visual Arts, 93<br />

YALE L.J. 1565, 1571 (1984); William M. Landes, Copyright, Borrowed Images,<br />

and Appropriation Art: An Economic Approach, 9 GEO. MASON L. REV. 1, 1<br />

(2000)).<br />

61. Lange & Anderson, supra note 35, at 132.<br />

62. Id. at 137.<br />

63. Tang, supra note 56, at 97–98.<br />

64. See Badin, supra note 57, at 1660.<br />

65. Tang, supra note 56, at 101.<br />

66. Badin, supra note 57, at 1668.<br />

67. Tang, supra note 56, at 101.<br />

68. Wong, supra note 53, at 1086.<br />

69. Szymanski, supra note 4, at 282 (citing Alan Korn, Comment, Renaming<br />

that Tune: Aural Collage, Parody and Fair Use, 22 GOLDEN GATE U. L. REV. 321,<br />

326 (1992)).<br />

70. Mongillo, supra note 50, at 2 (citing Robert Levine, Steal this Hook? DJ<br />

Skirts Copyright <strong>Law</strong>, N.Y. TIMES, (Aug. 7, 2008), http://www.nytimes.com/2008/<br />

08/07/arts/music/07girl.html).

504 THOMAS M. COOLEY LAW REVIEW [Vol. 28:3<br />

one.” 71 This recontextualization is the essence of the mashup genre.<br />

One may view mashup artists as plagiarists, 72 but it is far more<br />

realistic to see them as conductors interpreting the compositions of<br />

the past. 73 For example, these artists often mash samples from genres<br />

that are poles apart, proving that “dissimilar genres can coexist in<br />

harmony.” 74 They also test the boundaries of “song structure, the<br />

limits of what can be accepted as musicianship, and the nature of<br />

authorship.” 75 The significance of the mashup, like all other types of<br />

appropriation art, is its “ability to speak critically of the society in<br />

which both the public and the artist live.” 76 Consequently, the<br />

mashup is the “art of now.” 77<br />

II. THE PROBLEMS<br />

“ONCE WE ACCEPT OUR LIMITS, WE GO BEYOND THEM.” 78<br />

A. Inconsistency<br />

The central issue with the application of fair use is its<br />

inconsistency. 79 Because fair use is analyzed on a case-by-case basis,<br />

“the doctrine has lost its original usefulness to protect certain uses<br />

consistently.” 80 However, the selective application of the doctrine is<br />

not the only source fueling the inconsistency; societal changes and<br />

growth have also contributed to the uncertainty surrounding fair<br />

use. 81 Furthermore, as the doctrine’s terminology has not been<br />

71. Szymanski, supra note 4, at 314.<br />

72. See Badin, supra note 57, at 1660.<br />

73. Cf. id. at 1668 (stating that we should see “the artist as the manipulator or<br />

modifier of existing material, rather than as the inventor or creator of new forms”).<br />

74. Harper, supra note 11, at 423.<br />

75. Power, supra note 40, at 586.<br />

76. Badin, supra note 57, at 1656.<br />

77. Tang, supra note 56, at 101.<br />

78. ANNA BELCASTRO, 2012: FROM HERE TO ETERNITY 166 (2011) (quoting<br />

Albert Einstein).<br />

79. See Mongillo, supra note 50, at 16.<br />

80. Butt, supra note 59, at 1058.<br />

81. See Debra L. Quentel, “Bad Artists Copy. Good Artists Steal.”: The Ugly<br />

Conflict Between Copyright <strong>Law</strong> and Appropriationism, 4 UCLA ENT. L. REV. 39,<br />

64–65 (1996).

2011] FAIR USE FRAMEWORK 505<br />

defined, “the fair use doctrine is open to variable interpretation by the<br />

courts.” 82<br />

The opinions construing the doctrine present varying views of<br />

fair use. 83 As each judge takes a unique approach to a fair use<br />

defense, “[e]arlier decisions provide little basis for predicting later<br />

ones.” 84 Yet, little effort has been made by the courts to bridge those<br />

gaps; as a result, the doctrine’s terrain remains cragged and<br />

unpredictable. 85 Therefore, it is a risky business to presume that a<br />

reliable fair use defense exists. 86 The unsettled nature of the fair use<br />

doctrine will likely create fear in the eyes of the artist. 87 And “[w]hen<br />

an artist fears litigation, and therefore does not create art, the goals of<br />

copyright to promote creation are not fostered.” 88 The artist’s<br />

alternative is to obtain licenses for the source material that he or she<br />

wishes to use. However, due to the high cost of licenses and the time<br />

required to clear the sample, the creative process is severely<br />

suffocated. 89 The solution is simple: consistent rulings on common<br />

uses would reduce the grey area and simplify the law for the<br />

consumers of content. 90 If changes are not made in our near future,<br />

then it could be the end of the mashup genre as we know it. 91<br />

B. Originality<br />

Another central issue with the application of fair use is the<br />

misconception surrounding originality. As stated by former United<br />

States Supreme Court Justice Joseph Story:<br />

In truth, in literature, in science and in art, there are,<br />

and can be, few, if any, things, which in an abstract<br />

sense, are strictly new and original throughout. Every<br />

book in literature, science and art, borrows, and must<br />

82. Meyers, supra note 52, at 229. The United States Supreme Court has yet to<br />

define language in the four-factor test such as purpose and character. Id.<br />

83. Leval, supra note 34, at 1107.<br />

84. Id. at 1106.<br />

85. See id. at 1106–07.<br />

86. Katz, supra note 17, at 26.<br />

87. See Butt, supra note 59, at 1059.<br />

88. Id.<br />

89. See Meyers, supra note 52, at 234.<br />

90. Katz, supra note 17, at 53.<br />

91. Power, supra note 40, at 597.

506 THOMAS M. COOLEY LAW REVIEW [Vol. 28:3<br />

necessarily borrow, and use much which was well<br />

known and used before. 92<br />

His words attempt to convey the understanding that “[t]here is no<br />

such thing as a wholly original thought or invention.” 93 For that<br />

reason, all creative works are, to an extent, imitative (perhaps even<br />

plagiaristic?). 94 An interesting theory describes the creative works of<br />

our past as “[r]ecognizable objects,” 95 and by virtue of their<br />

recognizability, they “belong to all of us.” 96 A similar principle,<br />

which the majority of artists would acknowledge, is that “[a]rt history<br />

is a ‘cumulative progression.’” 97 Likewise, “an artist’s work is<br />

meaningless absent contextualization of the relationship between that<br />

work with others and with society in general.” 98 Every breakthrough<br />

is enabled by the thinkers of the past, 99 and to disallow artists to<br />

“build[ ] on the works of others” only steers us further from<br />

Progress. 100 “Surely, defining ‘Progress’ as development and growth<br />

implies that there is something more to artistic output than mere<br />

numbers.” 101 Copyright law’s very existence is premised on the fact<br />

that creative works “move society forward.” 102 Until we are<br />

permitted to borrow from the creations of our past, artists will be<br />

further restrained from practicing their art. 103 <strong>It</strong> is time for our legal<br />

system to embrace the fair use doctrine as a vehicle of growth. The<br />

arts, including music, have the potential to “shape the changing<br />

social, political, and theoretical conditions of [our] time.” 104 If fair<br />

use can be tailored to allow reflection on our past through<br />

92. Emerson v. Davies, 8 F. Cas. 615, 619 (C.C.D. Mass. 1845).<br />

93. Leval, supra note 34, at 1109.<br />

94. See id.<br />

95. Tang, supra note 56, at 83 (internal quotations omitted).<br />

96. Id.<br />

97. Butt, supra note 59, at 1065 (internal quotations omitted).<br />

98. Id.<br />

99. See Leval, supra note 34, at 1109 (quoting Zechariah Chafee, Reflections of<br />

the <strong>Law</strong> of Copyright, 45 COLUM. L. REV. 503, 511 (1945)).<br />

100. Ashtar, supra note 10, at 317 (quoting Nash v. CBS, 899 F.2d 1537, 1540<br />

(7th Cir. 1990)).<br />

101. Tang, supra note 56, at 100.<br />

102. Quentel, supra note 81, at 41.<br />

103. See Meyers, supra note 52, at 219.<br />

104. Tang, supra note 56, at 78.

2011] FAIR USE FRAMEWORK 507<br />

appropriation, then our culture and society will surely grow as we<br />

navigate the road to Progress. 105<br />

III. THE DOCTRINE OF FAIR USE<br />

There may be light at the end of the tunnel. One court’s opinion<br />

stands above the rest on our quest to frame the mashup as a fair use.<br />

In <strong>Blanch</strong> v. Koons, 106 it seems that “old attitudes have been<br />

displaced or supplanted by new ones in the domain of culture.” 107 In<br />

<strong>Blanch</strong>, Jeff Koons, a well-known visual artist, appropriated a<br />

copyrighted photograph in a collage painting that was commissioned<br />

to be displayed at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation in New<br />

York City. 108 The photograph in question, Silk Sandals by Gucci, was<br />

taken by professional photographer Andrea <strong>Blanch</strong>. 109 Portions of the<br />

photograph were used in Koons’ painting, Niagara. 110 Koons<br />

prevailed on his fair use defense at the district-court and appellate<br />

levels. 111 The <strong>Blanch</strong> opinion demonstrates a decision that is most in<br />

tune with the purpose of copyright law.<br />

The fair use factors must be “weighed together, in light of the<br />

purposes of copyright.” 112 The preamble to 17 U.S.C. § 107 indicates<br />

fair uses such as criticism and comment. 113 <strong>It</strong> is important to note that<br />

the uses included are only examples and that the doctrine is not<br />

limited to those uses. 114 Some scholars claim that appropriation is a<br />

form of criticism and comment. 115 However, not all sampling and<br />

mashup artists appropriate work for the purpose of criticism or<br />

comment. 116 Furthermore, as previously addressed, mashups are<br />

“more aptly characterized as re-contextualization.” 117<br />

105. See id.<br />

106. <strong>Blanch</strong> v. Koons, 467 F.3d 244 (2d Cir. 2006).<br />

107. Williams, supra note 2, at 49 (quoting Peter Jaszi, Is There Such a Thing as<br />

Postmodern Copyright?, 12 TUL, J. TECH. & INTELL. PROP. 105, 105–06 (2009)).<br />

108. <strong>Blanch</strong>, 467 F.3d at 246.<br />

109. Id. at 248.<br />

110. Id. at 247–48.<br />

111. Id. at 246.<br />

112. Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc., 510 U.S. 569, 578 (1994).<br />

113. 17 U.S.C. § 107 (2006) (emphasis added).<br />

114. See Campbell, 510 U.S. at 577.<br />

115. Badin, supra note 57, at 1654.<br />

116. Harper, supra note 11, at 423 (citing Campbell, 510 U.S. at 578–85).<br />

117. Ashtar, supra note 10, at 295.

508 THOMAS M. COOLEY LAW REVIEW [Vol. 28:3<br />

A. Purpose and Character<br />

The first factor considers “whether and to what extent the new<br />

work is transformative.” 118 Again, to quote the words of Justice<br />

Story, the chief concern in assessing the transformative value is<br />

“whether the new work merely ‘supercede[s] the objects’ of the<br />

original creation, (‘supplanting’ the original), or instead adds<br />

something new, with a further purpose or different character, altering<br />

the first with new expression, meaning, or message.” 119 Because the<br />

purpose of copyright law is to promote Progress, the “creation of<br />

transformative works” embodies that purpose. 120 Therefore, “the<br />

more transformative the new work, the less will be the significance of<br />

[the] other factors, like commercialism, that may weigh against a<br />

finding of fair use.” 121 Furthermore, the commercialism component<br />

should not weigh too heavily in the analysis, regardless of the<br />

transformative value. Because most artists aspire to profit from their<br />

creations, the “courts should be wary of placing too much emphasis<br />

on the commercial nature in a fair use determination.” 122<br />

1. Transformative Value<br />

In <strong>Blanch</strong>, Jeff Koons detailed his mental processes during the<br />

creation of Niagara. 123 First, Koons explained his reasons for<br />

appropriating the photograph. He described how the legs in the<br />

photograph represented some worldly maxim to him. 124 The image of<br />

the legs was “a fact in the world, something that everyone<br />

experiences constantly.” 125 He went on to say that they were not<br />

“anyone’s legs in particular.” 126 His purpose for appropriating the<br />

photo was more reminiscent of Plato’s theory of Forms. 127 Forms<br />

“are independently existing entities whose existence and nature are<br />

graspable only by the mind, even though they do not depend on being<br />

118. Campbell, 510 U.S. at 579 (citing Leval, supra note 34, at 1111).<br />

119. Id. (alteration in original) (citation omitted).<br />

120. Id.<br />

121. Id.<br />

122. Robinson v. Random House, Inc., 877 F. Supp. 830, 840 (S.D.N.Y. 1995).<br />

123. <strong>Blanch</strong> v. Koons, 396 F. Supp. 2d 476, 480–81 (S.D.N.Y. 2005).<br />

124. Id.<br />

125. Id. at 481.<br />

126. Id.<br />

127. S. Marc Cohen, Theory of Forms, UNIV. OF WASH. (last visited Nov. 20,<br />

2012, 2:48 PM), http://faculty.washington.edu/smcohen/320/thforms.htm.

2011] FAIR USE FRAMEWORK 509<br />

so grasped in order to exist.” 128 Koons saw the legs in the photograph<br />

not as one woman’s legs but as the form of women’s legs. In Koons’s<br />

eyes, the legs were a commonplace image that he “transformed into a<br />

language” to communicate his message. 129 The district court<br />

acknowledged the character of the legs as “raw material in a novel<br />

context.” 130 The appellate court confirmed this view. 131 Koons did<br />

not merely repackage the photograph but employed the legs as a raw<br />

material into Niagara. 132<br />

“The secret to creativity is knowing how to hide your sources.” 133<br />

Appropriation requires the artist to lose sight of the source. 134<br />

New meaning is created in the “original images by creating new<br />

contexts and by deliberately erasing all signatures of authorship.” 135<br />

The sources gathered from the artist’s own experiences thus “become<br />

paint on a palette.” 136 Functionally, the artist creating a mashup is no<br />

different than the visual artist, like Koons, creating a collage. The<br />

artist approaches all genres with a nomadic attitude, considering all<br />

musical genres as raw materials. 137 Treating the source as a raw<br />

material is only one portion of the transformative diagnosis.<br />

Once Koons severed the “anonymous legs from the context of the<br />

photograph,” he positioned them over images of “ice cream, donuts<br />

and pastries.” 138 In doing so, he attempted to “suggest how<br />

commercial images like these intersect in our consumer culture and<br />

simultaneously promote appetites, like sex, and confine other desires,<br />

like playfulness.” 139 Koons’s artwork is “about how we relate to the<br />

things that we actually experience.” 140 Andrea <strong>Blanch</strong> constructed<br />

the photograph in a way that would “show some sort of erotic sense”<br />

128. Id.<br />

129. Badin, supra note 57, at 1656.<br />

130. <strong>Blanch</strong>, 396 F. Supp. 2d at 481.<br />

131. <strong>Blanch</strong> v. Koons, 467 F.3d 244, 253 (2d Cir. 2006).<br />

132. Id.<br />

133. LLOYD BRADLEY & THOMAS EATON, BOOK OF SECRETS 90 (2005) (quoting<br />

Albert Einstein).<br />

134. See Meyers, supra note 52, at 235–36.<br />

135. Badin, supra note 57, at 1668.<br />

136. Tang, supra note 56, at 83 (internal quotations omitted).<br />

137. See Szymanski, supra note 4, at 283.<br />

138. <strong>Blanch</strong> v. Koons, 396 F. Supp. 2d 476, 481 (S.D.N.Y. 2005).<br />

139. Id.<br />

140. Id.

510 THOMAS M. COOLEY LAW REVIEW [Vol. 28:3<br />

and bring more sensuality to the image. 141 The appellate court easily<br />

distinguished between the artists’ disparate purposes in use and<br />

creation, which confirmed “the transformative nature of the use.” 142<br />

“True art is characterized by an irresistible urge in the creative<br />

artist.” 143<br />

Koons considered the legs in Silk Sandals as “necessary for<br />

inclusion” in Niagara. 144 The legs in the photograph were so<br />

quintessential to Koons that taking a photograph himself was out of<br />

the question. 145 The New York Court of Appeals seemed to respect<br />

the words of Justice Holmes when considering “whether Koons had a<br />

genuine creative rationale for borrowing <strong>Blanch</strong>’s image.” 146 Faithful<br />

to the wisdom of Justice Holmes, the appellate court gave great<br />

deference to Koons’s reasoning for using the photograph and “his<br />

ability to articulate those reasons.” 147 As a result, the court’s opinion<br />

demonstrates how the focus of the transformative inquiry lies in the<br />

appropriator’s purpose rather than the actual transformation of the<br />

appropriated material. 148 The goal of the artist is met when the<br />

transformed “work enables the audience to perceive a new purpose or<br />

meaning for the preexisting work.” 149 There is a chance that some<br />

people will not see the transformative nature in the final work. 150<br />

Likewise, some believe that “mashups are not transformative because<br />

they do not change the original song’s purpose or connotation.” 151<br />

For example, DJ Earworm 152 mashed four songs together, all four<br />

141. <strong>Blanch</strong> v. Koons, 467 F.3d 244, 252 (2d Cir. 2006) (quoting Plaintiff’s<br />

Deposition at 112–13, <strong>Blanch</strong> v. Koons, 396 F. Supp. 2d 476 (S.D.N.Y. 2005) (No.<br />

03 Civ. 8026)).<br />

142. Id.<br />

143. BARNEY DAVEY, HOW TO PROFIT FROM THE ART PRINT MARKET 179<br />

(2005) (quoting Albert Einstein).<br />

144. <strong>Blanch</strong>, 467 F.3d at 255.<br />

145. Id.<br />

146. Id.<br />

147. Id. at n.5.<br />

148. Wong, supra note 53, at 1135.<br />

149. See Williams, supra note 2, at 73.<br />

150. See Meyers, supra note 52, at 231.<br />

151. Harper, supra note 11, at 416 (citing Michael Allyn Pote, Note, <strong>Mash</strong>ed-Up<br />

in Between: The Delicate Balance of Artists’ Interests Lost Amidst the War on<br />

Copyright, 88 N.C. L. REV. 639, 670–71 (2010)).<br />

152. Jordan “DJ Earworm” Roseman, About DJ Earworm, DJ EARWORM MUSIC<br />

MASHUPS, (Mar. 27, 2012, 7:32 PM), http://djearworm.com/about.

2011] FAIR USE FRAMEWORK 511<br />

written about togetherness. 153 A listener or, more importantly, a court<br />

may find the transformative value lacking in situations like this.<br />

However, the intent of the artist is not the only subject of inquiry in<br />

the transformative analysis.<br />

Analogous to a Koons collage painting, a mashup “creates<br />

something new by combining and recontextualizing the old.” 154<br />

Although both courts in <strong>Blanch</strong> put substantial weight on Koons’s<br />

purpose for appropriating and using the photograph, 155 future courts<br />

will likely favor the appropriator if the modifications made to the<br />

original are substantial. 156 Likewise, the more inventive the<br />

utilization of the original, the clearer the transformation will be to the<br />

court. 157 Koons did not merely copy the legs from the photograph—<br />

he made them his own creation. 158 Koons changed the direction of<br />

the legs, adjusted the color, and even “‘added a heel to one of the<br />

feet.’” 159<br />

“Imagination is everything. <strong>It</strong> is the preview of life’s coming<br />

attractions.” 160<br />

Although some claim that mashups “merely copy original works<br />

and rearrange them in a random way,” 161 others “see recontextualizing<br />

existent sounds as a greater creative challenge than<br />

starting from scratch with traditional instruments.” 162 In other words,<br />

the process of editing, altering, and arranging is transformative in<br />

itself. 163 Extracting the sample and preparing it for the new work is a<br />

demanding undertaking. 164 Brian Burton, also known as Danger<br />

Mouse, explains the process of crafting The Grey Album:<br />

153. See Harger, supra note 11, at 425.<br />

154. Mongillo, supra note 50, at 25.<br />

155. See id. at 26–27.<br />

156. See Johnson, supra note 9, at 158–59.<br />

157. See id. at 156.<br />

158. <strong>Blanch</strong> v. Koons, 396 F. Supp. 2d 476, 481 (S.D.N.Y. 2005).<br />

159. Id. (quoting Koons Aff. 5–6, June 10, 2005).<br />

160. PAUL HUTCHINS, THE SECRET DOORWAY: BEYOND IMAGINATION 87 (2008)<br />

(quoting Albert Einstein).<br />

161. Harper, supra note 11, at 423 (citing UMG v. MP3.com, Inc., 92 F. Supp.<br />

2d 349, 351 (S.D.N.Y. 2000)).<br />

162. Ashtar, supra note 10, at 284 (citing Amanda Webber, Note, Digital<br />

Sampling and the Legal Implications of <strong>It</strong>s Use After Bridgeport, 22 ST. JOHN’S J.<br />

LEGAL COMMENT. 373, 379–80 (2007)).<br />

163. Harper, supra note 11, at 424 (citing Mongillo, supra note 50).<br />

164. Ashtar, supra note 10, at 307.

512 THOMAS M. COOLEY LAW REVIEW [Vol. 28:3<br />

A lot of people just assumed I took some Beatles and,<br />

you know, threw some Jay-Z on top of it or mixed it<br />

up or looped it around, but it’s really a deconstruction.<br />

<strong>It</strong>’s not an easy thing to do. I was obsessed with the<br />

whole project, that’s all I was trying to do, see if I<br />

could do this. Once I got into it, I didn’t think about<br />

anything but finishing it. I stuck to those two because<br />

I thought it would be more challenging and more fun<br />

and more of a statement to what you could do with<br />

sampling alone. <strong>It</strong> is an art form. <strong>It</strong> is music. You can do<br />

different things, it doesn’t have to be just what some<br />

people call stealing. <strong>It</strong> can be a lot more than that. 165<br />

The mashup demands considerable creativity from the artist<br />

throughout the entire process. 166 Therefore, “[t]here is no discernible<br />

reason to discriminate against mash-ups because the transformation is<br />

exclusively done through production work.” 167 Realistically, the<br />

process may be more difficult for the mashup artist than for other<br />

appropriation artists. <strong>Mash</strong>up artists must overcome the obstacle of<br />

melding not only the clashing samples but also the genres and ideals<br />

that are contained in them.<br />

When the Supreme Court adopted Judge Pierre Leval’s<br />

transformative approach 168 in Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc., 169<br />

“it also embraced the aesthetic principle that a secondary user may<br />

legitimately use imitation to communicate new meaning about its<br />

target without the effect of superseding it—a dynamic central to<br />

appropriationism.” 170 <strong>It</strong> is time to embrace the mashup artist as a<br />

secondary user. <strong>Mash</strong>up artists are constantly challenging their<br />

listeners to consider music in new and alternative ways. 171 Even<br />

165. MATTHEW RIMMER, DIGITAL COPYRIGHT AND THE CONSUMER<br />

REVOLUTION: HANDS OFF MY IPOD 132–33 (2007) (quoting Corey Moss, Grey<br />

Album Producer Danger Mouse Explains How He Did <strong>It</strong>, MTV NEWS (Mar. 11,<br />

2004, 9:00 PM),<br />

http://www.mtv.com/news/articles/1485693/20040311/jay_z.jhtml).<br />

166. Johnson, supra note 9, at 150.<br />

167. Power, supra note 40, at 593.<br />

168. Leval, supra note 34, at 1111.<br />

169. 510 U.S. 569, 579 (1994).<br />

170. Badin, supra note 57, at 1692.<br />

171. See, e.g., Mongillo, supra note 50, at 27.

2011] FAIR USE FRAMEWORK 513<br />

though recontextualization is the means of transformation, as it was<br />

in <strong>Blanch</strong>, there is little doubt that Progress is the end result.<br />

2. Commercial Nature<br />

When courts find a transformative use, it tips the first factor in<br />

favor of the appropriation artist and often determines the outcome of<br />

the fair use analysis as a whole. 172 The commercial aspect of the first<br />

factor “‘concerns the unfairness that arises when a secondary user<br />

makes unauthorized use of copyrighted material to capture significant<br />

revenues as a direct consequence of copying the original work.’” 173<br />

However, courts do take into consideration any public benefit derived<br />

from the new work. 174 The public display of art and music clearly has<br />

“‘value that benefits the broader public interest.’” 175<br />

The district court in <strong>Blanch</strong> only commented on the commercial<br />

nature of the use; the court said that “[b]oth works were created for<br />

commercial purposes.” 176 The appellate court expanded on the<br />

commercial nature of the work by acknowledging that “Koons made<br />

a substantial profit from the sale of Niagara.” 177 Niagara was part of<br />

a seven-painting series commissioned by the bank. 178 Koons was<br />

paid $2 million for the entire series. 179 The compensation for Niagara<br />

was estimated at $126,877, whereas <strong>Blanch</strong> was paid $750 for her<br />

photograph. 180 Despite the profit derived from Niagra, the appellate<br />

court had no trouble finding in favor of Koons under the first<br />

factor. 181<br />

172. See Wong, supra note 53, at 1135 (citing Barton Beebe, An Empirical<br />

Study of U.S. Copyright Fair Use Opinions 1978–2005, 156 U.PA.L. REV. 549,<br />

604–05 (2008)).<br />

173. <strong>Blanch</strong> v. Koons, 467 F.3d 244, 253 (2d Cir. 2006) (quoting Am.<br />

Geophysical Union v. Texaco, Inc., 60 F.3d 913, 922 (2d Cir. 1994)).<br />

174. Id.<br />

175. Id. at 254; see also 20 U.S.C. § 951(4) (2006) (stating that “access to the<br />

arts and the humanities” fosters “wisdom and vision” and makes citizens “masters<br />

of their technology and not its unthinking servants”).<br />

176. <strong>Blanch</strong> v. Koons, 396 F. Supp. 2d 476, 481 (S.D.N.Y. 2005), aff’d, 467<br />

F.3d 244 (2d Cir. 2006).<br />

177. <strong>Blanch</strong>, 467 F.3d at 253.<br />

178. Id. at 248.<br />

179. Id.<br />

180. Id. at 248, 249.<br />

181. Id. at 251–54.

514 THOMAS M. COOLEY LAW REVIEW [Vol. 28:3<br />

The commercial aspect is likely to be in the artist’s favor whether<br />

or not the artist has economic motives. Some artists in the mashup<br />

community “choose not to release commercial albums.” 182 The result<br />

is a chilling effect on this modern form of artistic expression. 183<br />

Other artists create for purposes other than money, suggesting that at<br />

least some “mashup artists have noneconomic motives.” 184 That is<br />

why the majority of mashups are found on the Internet free of<br />

charge. 185 For those artists who seek a profit from their work, the<br />

<strong>Blanch</strong> decisions demonstrate how the transformative value greatly<br />

outweighs the commercial nature of the subsequent work. For<br />

example, due to the highly transformative nature of Niagara, even<br />

the hefty profit made by Koons was of little consequence to the<br />

outcome of the first factor.<br />

The ultimate goal of copyright law is to promote Progress. 186 <strong>It</strong><br />

clearly follows that the first factor “is the soul of fair use.” 187<br />

Therefore, a finding of justification under the first-factor analysis is<br />

“indispensible to a fair use defense.” 188 This section has shown that<br />

many aspects of appropriation art are transformative. There is<br />

transformative value in each step—from conception to unveiling. Not<br />

only are the artist’s purposes and goals direct support of the<br />

transformative value of the new work, but also the artistic process<br />

itself is highly transformative. The appropriated material goes<br />

through a metamorphosis of sorts. The appropriation artist captures<br />

the idea from the original image and employs it as raw material. The<br />

idea is given new context as the raw materials become native in the<br />

new work and all expression that stems from the original is stripped<br />

away. The final transformation gives appropriation art its meaning.<br />

The mélange of ideas at play in the new work transports the audience<br />

into a new dimension; a dimension where the seemingly familiar is<br />

unlike anything advanced in the past. In that way, the appropriation<br />

artist successfully transforms the audience, which in turn fosters<br />

public growth and Progress in the Arts. The above discussion<br />

182. Harper, supra note 11, at 410.<br />

183. See id.<br />

184. Id. at 427.<br />

185. Power, supra note 40, at 594.<br />

186. U.S. CONST. art. I, § 8, cl. 8.<br />

187. Leval, supra note 34, at 1116.<br />

188. Id.

2011] FAIR USE FRAMEWORK 515<br />

suggests that appropriation art is highly transformative; therefore, a<br />

mashup artist will likely prevail on the first factor.<br />

B. Nature and Amount<br />

The second and third factors will be addressed together. Due to<br />

their technical similarities to parodies, this section proposes that<br />

courts should treat mashups similar to parodies when considering<br />

these two factors. In the leading Supreme Court decision on fair use,<br />

Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc., the Court found the commercial<br />

parody of another artist’s song a fair use. 189<br />

The second factor in the fair use analysis is “the nature of the<br />

copyrighted work.” 190 This factor points to the notion that certain<br />

types of “works are closer to the core of intended copyright<br />

protection than others.” 191 This factor actually asks one to categorize<br />

the work as either expressive/creative or factual/informational. 192 In<br />

Campbell, the Court acknowledged that this distinction was “not<br />

much help in this case.” 193 Because “parodies almost invariably copy<br />

publicly known, expressive works,” this factor does not really tip in<br />

favor of either party. 194 The appellate court in <strong>Blanch</strong> realized that<br />

parodies and appropriation art are similar in that respect. 195<br />

Therefore, the appellate court in <strong>Blanch</strong> concluded that the second<br />

factor had limited usefulness in the overall fair use inquiry. 196 As in<br />

Campbell, the second factor in <strong>Blanch</strong> was, in essence, dismissed<br />

from the overall fair use analysis.<br />

The third factor is “the amount and substantiality of the portion<br />

used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole.” 197 This factor<br />

considers the quantity and quality of the materials used. 198 Again, the<br />

Campbell Court found this factor to be of little help. 199 Parody cannot<br />

189. 510 U.S. 569, 583–84 (1994).<br />

190. 17 U.S.C. § 107(2) (2006).<br />

191. Campbell, 510 U.S. at 586.<br />

192. <strong>Blanch</strong> v. Koons, 467 F.3d 244, 256 (2d Cir. 2006) (quoting HOWARD B.<br />

ABRAMS, THE LAW OF COPYRIGHT § 15:52 (2006)).<br />

193. Campbell, 510 U.S. at 586.<br />

194. Id.<br />

195. See <strong>Blanch</strong>, 467 F.3d at 257.<br />

196. Id.<br />

197. 17 U.S.C. § 107(3) (2006).<br />

198. Campbell, 510 U.S. at 587.<br />

199. Id. at 588.

516 THOMAS M. COOLEY LAW REVIEW [Vol. 28:3<br />

be effective or funny if the listener cannot recognize the original<br />

within the parody. 200 The test for parody is that “the parody must be<br />

able to ‘conjure up’ at least enough of that original to make the object<br />

of its critical wit recognizable.” 201 Hence, the art of the parody “lies<br />

in the tension between a known original and its parodic twin.” 202 This<br />

means that the parodist will often appropriate the most popular<br />

segments of a song, thereby allowing for easy identification of the<br />

original. 203 In <strong>Blanch</strong>, the appellate court gave great deference to<br />

Koons’s artistic goals. 204 The appellate court was charged with<br />

considering “whether, once he chose to copy Silk Sandals, he did so<br />

excessively, beyond his ‘justified’ purpose.” 205 The appellate court<br />

reviewed the creative efforts of the photographer to determine this<br />

factor. 206 <strong>Blanch</strong> put most of her creative expression into the<br />

background and setting of her photograph. 207 Because the<br />

background of the photograph was removed from the collage<br />

painting, the appellate court found that the third factor was “distinctly<br />

in Koons’s favor.” 208<br />

“All religions, arts and sciences are branches of the same<br />

tree.” 209<br />

The “privilege for parodies alone reaches no more than a fraction<br />

of the settings (a small fraction at that) in which transformative<br />

appropriations may take place.” 210 <strong>It</strong> is clear from the <strong>Blanch</strong> and<br />

Campbell opinions that parodies share many qualities with Koons’s<br />

work. <strong>It</strong> follows that mashups, parodies, and collage paintings are all<br />

branches of appropriation art. All forms of appropriation art signify<br />

their message through the reference, “‘which is expressible only if it<br />

is the original that gets used.’” 211 The parody in Campbell was in part<br />

200. Id.<br />

201. Id.<br />

202. Id.<br />

203. Id.<br />

204. See <strong>Blanch</strong> v. Koons, 467 F.3d 244, 257 (2d Cir. 2006).<br />

205. Id.<br />

206. Id. at 258.<br />

207. Id.<br />

208. Id.<br />

209. MARY MANN, SCIENCE AND SPIRITUALITY 174 (2004) (quoting Albert<br />

Einstein).<br />

210. Lange & Anderson, supra note 35, at 146.<br />

211. Tang, supra note 56, at 83 (quoting LAWRENCE LESSIG, REMIX 74–75<br />

(2008)).

2011] FAIR USE FRAMEWORK 517<br />

presumptively privileged. 212 In general, mashups “‘almost invariably<br />

copy publicly known, expressive works’” 213 and “can only exist with<br />

a high level of appropriation; anything less would be insufficient.” 214<br />

Although mashups “do not strictly meet the definition of a parody,”<br />

they should be analyzed in the same manner as parodies. 215<br />

Essentially, when addressing these two factors, mashups should<br />

receive the same presumptive privilege as parodies earn. 216<br />

C. Market<br />

Under the fourth factor of the analysis, courts determine both the<br />

market harm caused by the alleged infringer and the aggregate effect<br />

that this type of conduct would produce. Therefore, the inquiry<br />

considers any possible harm to the derivative market of the<br />

original. 217 The only concern when discussing the derivative market<br />

for the original is the possibility of market substitution. 218<br />

Some courts maintain the view “‘that the fourth factor will favor<br />

the secondary user when the only possible adverse effect occasioned<br />

by the secondary use would be to a potential market or value that the<br />

copyright holder has not typically sought to, or reasonably been able<br />

to, obtain or capture.’” 219 Therefore, “if the copying was not of the<br />

type that an author reasonably would have foreseen” prior to the<br />

alleged infringement, then the copying cannot be construed as<br />

encroaching on the intentions of the original artist. 220 In <strong>Blanch</strong>,<br />

<strong>Blanch</strong> admitted that Niagara did not cause any harm to her career or<br />

plans for the photograph. 221 Furthermore, <strong>Blanch</strong> conceded that the<br />

value of her photography was not lowered by its use in Niagara. 222<br />

212. Lange & Anderson, supra note 35, at 145.<br />

213. Mongillo, supra note 50, at 29 (quoting Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music,<br />

510 U.S. 569, 586 (1994)).<br />

214. Power, supra note 40, at 598.<br />

215. Id. at 592.<br />

216. See Lange & Anderson, supra note 35, at 145 (discussing how parodies<br />

became presumptively privileged).<br />

217. See NXIVM Corp. v. Ross Institute, 364 F.3d 471, 482 (2d Cir. 2004).<br />

218. Id. at 593.<br />

219. <strong>Blanch</strong> v. Koons, 396 F. Supp. 2d 476, 482 (S.D.N.Y. 2005) (quoting Am.<br />

Geophysical Union v. Texaco, Inc., 60 F.3d 913, 930 (1994)).<br />

220. Christopher Sprigman, Copyright and the Rule of Reason, 7 J. TELECOMM.<br />

& HIGH TECH. L. 317, 321 (2009).<br />

221. <strong>Blanch</strong> v. Koons, 467 F.3d 244, 258 (2d Cir. 2006).<br />

222. Id.

518 THOMAS M. COOLEY LAW REVIEW [Vol. 28:3<br />

“All that is valuable in human society depends upon the<br />

opportunity for development accorded the individual.” 223<br />

<strong>Mash</strong>up artists use their mashups instrumentally to disrupt the<br />

confines of our music culture. 224 They attempt to create works that<br />

bridge the gap between genres rather than supersede them. 225 The<br />

listeners who seek out these mashups do not do so to hear the<br />

originals individually; rather, they wish to invigorate their ears and<br />

challenge any musical profiles to which they may adhere. 226<br />

Therefore, “it is highly improbable that listeners will use a mashup as<br />

an alternative or substitute for the original songs in the mashup.” 227<br />

The fourth factor of the fair use doctrine should be more<br />

concerned with ensuring “‘that credit is given where credit is<br />

due.’” 228 Although most musicians would likely be content with<br />

simple accreditation by the appropriation artist, 229 requiring some<br />

form of accreditation in transformative-appropriation cases could<br />

solve most of the mashup artists’ problems. 230 Few artists should<br />

complain about appropriation artists remixing or mashing their work.<br />

One may infer that for an artist to remix or sample the work of<br />

another artist there is some inherent respect or appreciation for that<br />

artist. 231 Most importantly, as you will see below, the act of<br />

appropriating another’s work can have a promotional result for the<br />

original artist.<br />

Although the fourth factor, and fair use in general, seeks to<br />

determine whether the new work supplants the market of the original,<br />

there are theories that the new work actually creates a “new market<br />

for the original work[], actually expanding the audience and<br />

availability of the original work[].” 232 Although there is a chance that<br />

the new work could negatively impact the market of the original, it is<br />

223. NICK LYONS ET. AL., THE APPRAISER’S HANDBOOK: A GUIDE FOR DOCTORS<br />

120 (2006) (quoting Albert Einstein).<br />

224. Mongillo, supra note 50, at 27–28.<br />

225. See id.<br />

226. Id. at 31.<br />

227. Harper, supra note 11, at 434.<br />

228. Williams, supra note 2, at 57 (quoting Rogers v. Koons, 960 F.2d 301, 310<br />

(2d Cir. 1992)).<br />

229. Lange & Anderson, supra note 35, at 155.<br />

230. See id.<br />

231. See Lessig, supra note 12, at 972.<br />

232. Katz, supra note 17, at 57.

2011] FAIR USE FRAMEWORK 519<br />

highly unlikely. 233 The possibility that a mashup will infringe on the<br />

original artists’ plans to create their own mashups is just as<br />

improbable. 234 On the contrary, it is not unreasonable to believe that<br />

the mashup will produce beneficial results for the original artist (or in<br />

the worst case scenario, have no effect). A mashup has the power to<br />

create new fans of the original work(s). But for the mashup, the<br />

listener may not have been introduced to the original artist. 235 This<br />

new interest in the original artist may even lead to increased sales of<br />

the original work. 236 Especially for older works, which become<br />

appropriated, the mashup may give the original work “a new lease on<br />

life.” 237 The mashup could be a blessing in disguise for the original<br />

artist as the majority of pre-appropriated works have likely seen their<br />

sales peak. 238 Sampling practices such as these have not only<br />

promoted the sampled artists but have also fostered the “development<br />

of new postmodern musical forms.” 239<br />

Breaking loose from this tunnel vision would be beneficial. With<br />

this narrow viewing of the potential benefit to the original artist’s<br />

market, one can only glimpse at the tip of the mashup’s potential.<br />

Although this Article discusses the mashup only in the musical sense,<br />

there is evidence of the mashup’s footprint in other aspects of life. 240<br />

Therefore, let us broaden our view and explore the mashup’s effect<br />

on a larger scale.<br />

Living in the digital age has its benefits; certainly one benefit is<br />

how technology has allowed us to “connect and collaborate” with<br />

each other. 241 Due to the uncertainty of the mashup’s rightful place in<br />

233. See Mongillo, supra note 50, at 31.<br />

234. Harper, supra note 11, at 435.<br />

235. Id. at 441.<br />

236. Id.<br />

237. Meyers, supra note 52, at 243 (citation omitted).<br />

238. See Szymanski, supra note 4, at 320–21 (citing Jeffrey H. Brown, They<br />

Don’t Make Music the Way They Used To: The Legal Implications of Sampling in<br />

Contemporary Music, 1992 WIS. L. REV. 1941, 1974–75 (1992)).<br />

239. See id. at 288.<br />

240. E.g., Duane Merrill, <strong>Mash</strong>ups: The New Breed of Web App, IBM, July 24,<br />

2009, available at http://public.dhe.ibm.com/software/dw/xml/x-mashups-pdf.pdf<br />

(discussing mashup applications); Brian Lamb, Dr. <strong>Mash</strong>up; or, Why Educators<br />

Should Learn To Stop Worrying and Love the Remix, EDUCAUSE REV., July–Aug.<br />

2007, available at http://net.educause.edu/ir/library/pdf/ERM0740.pdf (discussing<br />

mashups in education).<br />

241. See Katz, supra note 17, at 39.

520 THOMAS M. COOLEY LAW REVIEW [Vol. 28:3<br />

our legal system, our culture’s development is greatly<br />

disadvantaged. 242 Companies with the capability to employ the<br />

mashup into their business model likely will not take the risk.<br />

However, if these companies were given the ability to integrate the<br />

mashup into their business, then the result could be beneficial to<br />

all. 243 Arguably, the mashup is the key innovation to our future;<br />

companies that ignore this innovation “‘risk becoming irrelevant<br />

spectators.’” 244 Allowing fair use to permeate our culture will allow<br />

American industry to not only remain the world leader in<br />

development, but also to induce a period of rapid growth extending<br />

well into our future. 245<br />

Fair use industries have stayed afloat during the recent economic<br />

decline. 246 These industries “make up one-sixth of the U.S. economy<br />

and employ one of every eight workers.” 247 From 2002 to 2007,<br />

“[f]air use industries . . . grew at a faster pace than the overall<br />

economy.” 248 And from 2002 to 2006, fair use industries were<br />

“directly responsible for more than 18% of U.S. economic growth<br />

and nearly 11 million American jobs.” 249 Fair use is a fundamental<br />

industry in our economy, and with the current decline in economic<br />

trends, it would be prudent to reevaluate our application of the fair<br />

use doctrine.<br />

“‘The ultimate test of fair use . . . is whether the copyright law’s<br />

goal of promoting the Progress of Science and useful Arts would be<br />

242. C.f. Lessig, supra note 12, at 971 (stating that modern-day industry could<br />

flourish if the remix were free).<br />

243. Id.<br />

244. See Katz, supra note 17, at 39 (quoting DON TAPSCOTT & ANTHONY D.<br />

WILLIAMS, WIKINOMICS: HOW MASS COLLABORATION CHANGES EVERYTHING 163<br />

(2006)).<br />

245. Id. at 21, 61.<br />

246. CCIA to Release 2011 Study Calculating Economic Value of “Fair Use,”<br />

COMPUTER & COMM. INDUST. ASS’N (July 8, 2011), http://www.ccianet.org/<br />

index.asp?sid=5&artid=244&evtflg=True.<br />

247. Id.<br />

248. THOMAS ROGERS & ANDREW SZAMOSSZEGI, FAIR USE IN THE U.S.<br />

ECONOMY: ECONOMIC CONTRIBUTION OF INDUSTRIES RELYING ON FAIR USE 8<br />

(2010), available at http://www.ccianet.org/CCIA/files/ccLibraryFiles/Filename/<br />

000000000354/fair-use-study-final.pdf.<br />

249. COMPUTER COMMC’NS INDUST. ASS’N, FAIR USE ECONOMY REPRESENTS<br />

ONE-SIXTH OF U.S. GDP (Sept. 12, 2007), available at<br />

http://www.ccianet.org/index.asp.

2011] FAIR USE FRAMEWORK 521<br />

better served by allowing the use than by preventing it.’” 250 If<br />

appropriation artists like Koons may exercise their talent through fair<br />

use, then there is no reason why mashup artists, such as Girl Talk or<br />

Danger Mouse, should not be extended the same privilege. 251 The<br />

fair use doctrine may prove to be a most powerful tool for our future.<br />

The <strong>Blanch</strong> opinions demonstrate a fair use determination in line<br />

with the original goal of copyright law. If courts use the <strong>Blanch</strong><br />

opinions as a framework when applying the fair use factors in<br />

appropriation cases, then Progress may finally be restored to<br />

copyright law.<br />

IV. THE SOLUTION<br />

“To raise new questions, new possibilities, to regard old<br />

questions from a new angle, requires creative imagination and marks<br />

real advance in science.” 252<br />

We live in an age where society is willing to accept the mashup<br />

as a legitimate, creative work. 253 Because America has been deemed<br />

a “nation of infringers,” 254 we could not be further from the purpose<br />

of copyright law than we are today. The current legal system<br />

disciplines those who employ this widespread practice. 255 “The<br />

refusal to acknowledge the new reactionary mode of artistic<br />

production actually means that it is defying Progress.” 256 If today’s<br />

copyright regime had been in power “‘from 1905 to 1975, we would<br />

not have modern art as we know it.’” 257 Before the digital age,<br />

copyright evolved with technology to provide our culture with the<br />

room to grow. 258 The expanded group of protected works enumerated<br />

in the Copyright Act today developed “in a somewhat piecemeal<br />

way, often in response to technological and cultural<br />

250. <strong>Blanch</strong> v. Koons, 467 F.3d 244, 251 (2d Cir. 2006) (quoting Castle Rock<br />

Entm’t Inc. v. Carol Publ’g Grp., 150 F.3d 132, 141 (1998)).<br />

251. C.f. Szymanski, supra note 4, at 289.<br />

252. R. KEITH SAWYER, EXPLAINING CREATIVITY: THE SCIENCE OF HUMAN<br />

INNOVATION 90 (2012) (quoting Albert Einstein).<br />

253. Tang, supra note 56, at 84.<br />

254. Katz, supra note 17, at 40.<br />

255. Harper, supra note 11, at 441 (citing Lessig, supra note 12, at 969).<br />

256. Tang, supra note 56, at 79.<br />

257. Meyers, supra note 52, at 238 (quoting Geraldine Norman, The Power of<br />

Borrowed Images, ART & ANTIQUITIES, 123, 128 (Mar. 1996)).<br />

258. See Quentel, supra note 81, at 64.

522 THOMAS M. COOLEY LAW REVIEW [Vol. 28:3<br />

developments.” 259 We are at a pivotal moment in this digital age<br />

where, if permitted, our culture could grow at an exponential rate. If<br />

we wish for this wave of development to continue, then the law must<br />

acquiesce to “a greater degree of appropriation” than it has in the<br />

past. 260<br />

Many seek to amend the fair use doctrine. <strong>It</strong> would be more<br />

judicious to scrutinize the principles embedded in the four factors.<br />

The moment Progress is found within every opinion, only then will<br />

the doctrine finally sing in tune with the goal of copyright. “We are at<br />

that moment in which we as readers can, and do, participate in<br />

writing our culture.” 261 Great technological growth of the digital age<br />

has brought greater interaction, creating what we now call a<br />

participatory culture. 262 Today’s technology enables consumers to<br />

“author their own lives.” 263 Under our current copyright practices,<br />

the user takes second place to the copyright owner. 264 But today’s<br />

user is tomorrow’s artist. 265 If the courts saw the user in the same<br />

light as they see the artist, then a dramatic cultural shift would surely<br />

follow. 266<br />

“The value of a man should be seen in what he gives and not in<br />

what he is able to receive.” 267<br />

The fair use analysis currently revolves around the defendant’s<br />

use of the plaintiff’s work. 268 However, if the courts were to<br />

centralize its analysis on the result of the defendant’s use rather than<br />

the steps used to reach those results, then not only would the doctrine<br />

better serve the purpose of copyright, 269 but it also would complete<br />

the long-awaited distinction between creative and consumptive<br />

259. Carpenter, supra note 15, at 51.<br />

260. Lange & Anderson, supra note 35, at 132.<br />

261. Tang, supra note 56, at 84.<br />

262. See Harper, supra note 11, at 444.<br />

263. Williams, supra note 2, at 63 (quoting YOCHAI BENKLER, THE WEALTH OF<br />

NETWORKS: HOW SOCIAL PRODUCTION TRANSFORMS MARKETS AND FREEDOM 175<br />

(2006)).<br />

264. Wong, supra note 53, at 1097.<br />

265. Id.<br />

266. See id. at 1080.<br />

267. JOEY O’BRIEN, THE GODS ARE ANGRY 37 (2011) (quoting Albert Einstein).<br />

268. Wong, supra note 53, at 1109.<br />

269. See id.

2011] FAIR USE FRAMEWORK 523<br />

infringement. 270 Our fair use standards do not treat “the enterpriselevel<br />

bootlegger and the creative mashup artist” any differently. 271 As<br />

a result, the war against piracy is smothering a movement, a genre, an<br />

industry, and a critical mode of expression in our current culture. 272<br />

The creative-versus-consumptive illustration evidences that an urgent<br />