The Long Road Home - Global Rights

The Long Road Home - Global Rights

The Long Road Home - Global Rights

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

G L O B A L R I G H T S<br />

<strong>Global</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> Magazine SUMMER 2005<br />

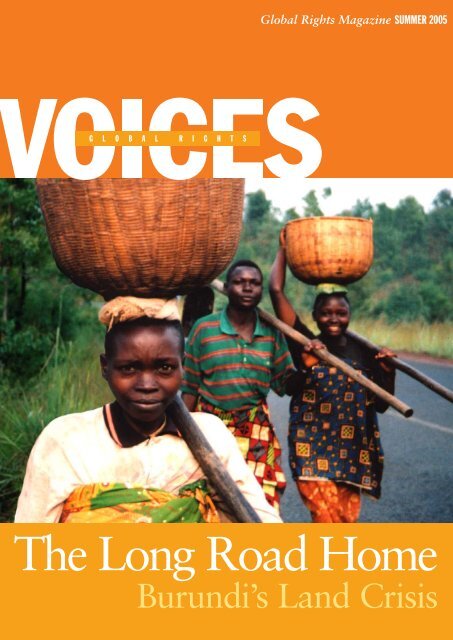

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Long</strong> <strong>Road</strong> <strong>Home</strong><br />

Burundi’s Land Crisis

Photos by Maria Koulouris<br />

C O V E R S T O R Y<br />

4 Summer 2005 <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> VOICES<br />

<strong>The</strong><br />

In 1972, when Etienne* was just<br />

five years old, a brutal campaign<br />

of ethnic violence swept Burundi,<br />

engulfing his village in the country’s<br />

north. Etienne’s mother, in an<br />

attempt to avoid the cruel fate of so<br />

many of her compatriots, fled to<br />

neighboring Rwanda with seven<br />

children in tow. <strong>The</strong> family left<br />

behind two parcels of land.<br />

Twenty-one years later, after<br />

historical elections brought Burundi’s<br />

first Hutu president to power,<br />

Etienne’s family, feeling hopeful for<br />

the future of their country, decided<br />

the time had come to return home.<br />

But upon arrival in Burundi, they<br />

quickly found that they had no land<br />

to which they could return. <strong>The</strong>ir<br />

primary family home had been<br />

illegally occupied, the second one<br />

was destroyed during the fighting<br />

they had fled.<br />

Seeking to reclaim what had been<br />

legally theirs, Etienne turned to the<br />

local governor for help. Recognizing<br />

the family’s right to the land, the<br />

governor ordered the new tenant off<br />

the disputed property. But the home’s<br />

wealthy new occupant simply<br />

*Names have been changed.<br />

<strong>Long</strong><br />

<strong>Road</strong><br />

<strong>Home</strong><br />

ignored the governor’s demand.<br />

Etienne’s family received no<br />

compensation for its loss and was<br />

soon forced to scatter across the<br />

country, each member settling<br />

wherever he or she could find work.<br />

Twelve years later, Etienne now<br />

scrapes together just enough money<br />

to pay his rent, unable to save enough<br />

to buy new land or rebuild his<br />

family’s property.<br />

Conflicts over land are all too<br />

common among the people of<br />

Burundi, a small landlocked country<br />

that borders Rwanda, Tanzania, and<br />

the Democratic Republic of Congo.<br />

With the country’s 6.8 million<br />

people living in an area<br />

approximately the size of Maryland,<br />

population density is the second<br />

highest on mainland Africa. <strong>The</strong><br />

population is growing at the<br />

staggering rate of three percent a year<br />

— a figure that, if maintained, will<br />

mean a doubling of the population<br />

every two decades. And although<br />

only 44 percent of Burundi’s land is<br />

arable, more than 90 percent of the<br />

population lives in the rural<br />

countryside (which begins just<br />

minutes outside the capital<br />

Bujumbura) and relies on agriculture<br />

for their subsistence. Per capita yearly<br />

income is just $100 and there are few<br />

other ways to earn a living.<br />

Family disagreements over the<br />

inheritance and sharing of property<br />

and the repeated sub-division of land<br />

into ever-smaller parcels are a source<br />

of conflict throughout the country.<br />

Compounding this problem,<br />

Burundi’s successive governments<br />

have poorly managed official land<br />

policies for decades, and Burundians<br />

— most of whom have been dissuaded<br />

by the lack of opportunity to raise<br />

their individual concerns in a<br />

traditionally centralized society —<br />

have not, for the most part, engaged<br />

local authorities on the issue.<br />

Making Burundi’s land issue even<br />

more complex, cycles of violence<br />

have forced several waves of<br />

refugees to flee their homes and,<br />

upon their return, serious disputes<br />

have arisen over the land left<br />

behind. <strong>The</strong>se disputes, many of<br />

which involve illegal occupations<br />

and state expropriations, threaten<br />

Burundi’s bid for a peaceful and<br />

stable future.

Burundi’s Land Crisis<br />

Today, with the country now enjoying<br />

peace for the first time in decades, the<br />

number of people who may soon return<br />

home is staggering. In April 2004,<br />

roughly 140,000 Burundians still resided<br />

in the country’s internally displaced<br />

persons camps; at the end of the year,<br />

almost three quarters of a million<br />

remained in Tanzania. <strong>The</strong>se figures<br />

indicate that as the situation in Burundi<br />

improves, nearly one in eight of the<br />

country’s citizens may soon embark on a<br />

return from exile. But according to<br />

Refugees International, more than 95<br />

percent of these displaced Burundians<br />

have no home to which they can return.<br />

History of the Conflict<br />

<strong>The</strong> 1972 violence from which Etienne’s<br />

family fled came just a decade after<br />

Burundi gained its independence from<br />

Belgium, a colonial power that had<br />

privileged the country’s minority Tutsi<br />

population and marginalized the majority<br />

Hutus. In the years leading up to the<br />

violence, a small sub-clan of Tutsis seized<br />

power in a bloody coup and stripped<br />

Hutus of all positions of authority. When<br />

the Hutus revolted, their efforts were met<br />

with disproportionate and systematic<br />

violence from the Tutsi-dominated<br />

military. In the fighting that ensued, about<br />

200,000 Burundians were killed.Hundreds<br />

of thousands of others,like Etienne’s family,<br />

fled to neighboring countries, leaving<br />

behind their land and property.<br />

In the years that followed, this land and<br />

property were illegally occupied,looted or,<br />

in many cases, expropriated by the state. In<br />

the southern city of Rumonge, for<br />

example, where valuable palm plantations<br />

dot the hills, the government seized<br />

property and arbitrarily distributed it to<br />

select businesses and powerful individuals.<br />

Elsewhere, people simply occupied the<br />

empty homes of those who had fled.And<br />

conflict continued unabated.<br />

In 1993, for the first time in Burundi’s<br />

history, a Hutu was elected to the<br />

country’s presidency. Before long, he<br />

began to urge those who had fled the<br />

violence to return home.A generation of<br />

refugees saw hope in this change and<br />

some, like Etienne’s family, began their<br />

journey back to Burundi.<br />

Just months after his election, however,<br />

the president and several members of his<br />

administration were assassinated —<br />

sparking what would beome a 12 year<br />

civil war. It is said that these killings were<br />

motivated, in part, by the government’s<br />

handling of land conflicts. About 300,000<br />

men, women, and children died in this<br />

wave of violence, and 800,000 were<br />

displaced from their homes. Many of<br />

these people fled to neighboring<br />

Tanzania, while others were displaced<br />

within Burundi, settling in squalid camps.<br />

Like those who had fled previous periods<br />

of conflict, these Burundians left behind<br />

property that was soon taken over, adding<br />

yet another layer to the country’s already<br />

serious land crisis.<br />

In 2000, things began to improve when<br />

the warring parties signed the Arusha<br />

Agreement, a comprehensive peace<br />

settlement. Even more significantly, the<br />

government and main rebel groups<br />

agreed to a critical ceasfire. And in early<br />

2005 the country held a peaceful<br />

referendum on its post-transition<br />

constitution, which includes a powersharing<br />

system between Hutus and Tutsis.<br />

A Truth and Reconciliation Commission<br />

has been established,the security situation<br />

has improved drastically, and general<br />

elections will begin in June 2005. With<br />

the possibility of peace now on the<br />

horizon, those forced to flee Burundi’s<br />

waves of conflicts have again begun to<br />

return home.<br />

<strong>Long</strong> <strong>Road</strong> <strong>Home</strong>, continued on page 6<br />

<strong>Global</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> VOICES Summer 2005 5

<strong>Long</strong> <strong>Road</strong> <strong>Home</strong>, continued from page 5<br />

Counselors and paralegals offer advice, Butarugera zone, province of Muyinga.<br />

But Burundi’s government seems ill-prepared to deal with<br />

all of the country’s potential returnees. “<strong>The</strong> government’s<br />

attempts to deal with the land issue have been weak, at best,”<br />

said Rene Claude Niyonkuru, of the Ngozi-based<br />

Association for Peace and Human <strong>Rights</strong>, a <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Rights</strong><br />

partner. “<strong>The</strong> Arusha Agreement established a National<br />

Committee for the Rehabilitation of Victims to address<br />

conflicts over land, but it has been understaffed,<br />

underfunded and ineffective.”<br />

Adding to the problem, Burundi lacks harmonized land<br />

laws or a comprehensive land policy and instead relies on<br />

HELPING A COMMUNITY HEAL<br />

6 Summer 2005 <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> VOICES<br />

P artners for Justice SPEAK OUT<br />

EMMANUEL NDABUMVIRUBUSA<br />

Paralegal<br />

Muyinga, Burundi<br />

In 2000, visitors from <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> came to my community in<br />

Muyinga to talk about how they wanted to help people resolve their<br />

problems through legal clinics. <strong>The</strong>y suggested that we elect<br />

persons from our colline (hill) whom we regarded as leaders, to be<br />

trained in problem solving at the community level. In selecting<br />

these people, we were asked to take into account integrity,<br />

morals, and the person’s capacity to relate to others. We also<br />

were asked to specifically consider the inclusion of the women and<br />

minorities among us.<br />

At the time, I was a farmer and had been only to primary school.<br />

But still, I was fortunate enough to be selected. Now, I serve my<br />

community as a trained paralegal, a role that I believe is<br />

important. Most of the problems that I help resolve are land<br />

conflicts, especially related to returnees whose land has been<br />

custom and outdated legislation. This includes the 1986<br />

Land Act, which grants legal title to whomever occupies<br />

land for at least 30 years, if no claims are made within two<br />

to three years of this period — regardless of how the land<br />

was obtained. <strong>The</strong> lack of coherent rules governing land<br />

ownership has had significant implications for people like<br />

Etienne. As Mr. Niyonkuru explained, “If Burundi is ever<br />

to address the enormity of its land crisis, a review of these<br />

laws and policies is critical.”<br />

As it stands, Burundi’s courts have not been effective in<br />

resolving land disputes. Although 80 percent of the<br />

contentious cases in the country’s judicial system involve<br />

conflicts over land, few Burundians have confidence in<br />

court verdicts, fewer than half of which are ever enforced.<br />

And for most people, even flawed legal proceedings are too<br />

lengthy, complex, and expensive to pursue. Etienne, for<br />

instance, says he has avoided the courts because the man<br />

living in his family’s home could afford the legal<br />

representation that Etienne could not. And Bashinganhahe,<br />

local elders who historically resolved disputes out of court,<br />

have begun to charge for their services, causing many<br />

Burundians to question their impartiality.<br />

How <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> Helps<br />

In an attempt to address these problems, <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Rights</strong>’<br />

Burundi program established both stationary and mobile<br />

clinics in Muyinga, Kirundo, and Ngozi provinces to help<br />

illegally occupied. Such problems are increasing as more people<br />

return to Burundi from neighboring countries. In Burundi, land is<br />

extremely important — it is what allows the population to eat, to<br />

survive. Most Burundians are farmers like me.<br />

I help mediate conflicts in my community and put people in touch<br />

with the appropriate authorities so that time and resources are not<br />

wasted seeking help from the wrong places. I also received training<br />

on listening skills and counseling people. <strong>The</strong> benefit of this kind of<br />

work is that it contributes directly to the community. Without this<br />

assistance, many people would have difficulty solving their<br />

problems. It feels very satisfying to be able to assist them.<br />

Mediation is particularly welcomed by local populations. Judicial<br />

proceedings are often lengthy and costly and many people don’t<br />

have the time or resources to go through the courts. Mediation, on<br />

the other hand, is less confrontational and takes less time than<br />

court proceedings. Parties are happy to have successful mediations<br />

because it means that they have reached an agreement In Burundi,<br />

we often say that a bad agreement is worth more than the<br />

imposition of a good decision.<br />

<strong>The</strong> training that I received from <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> has allowed me to fill<br />

gaps in my understanding of the law. Before, my community often<br />

relied solely on custom. That now has changed. Ten years from now,<br />

I hope people have even more trust in paralegals to help them<br />

resolve disputes. And I hope that through my work they also have a<br />

better understanding of their own human rights.

people solve their legal issues, most of which are landrelated.<br />

Staffed by full-time counselors, these clinics serve<br />

hundreds of clients each month, sometimes traveling to<br />

remote areas to reach people who otherwise would be<br />

unable to seek assistance. <strong>The</strong> counselors familiarize<br />

people with their rights, help mediate conflicts, and train<br />

paralegals — Burundians elected by their communities<br />

because of their integrity and fairness — to serve as local<br />

leaders.After learning about relevant aspects of Burundian<br />

law, including the Family Code and the Land Law, these<br />

paralegals are able to inform people about their rights and<br />

help them resolve their disputes. When paralegals are<br />

unable to solve a problem, they turn to the legal clinics<br />

established by <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> for support.<br />

<strong>Global</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> recently handed over two of these clinics<br />

to partner organizations, and has gradually shifted its<br />

focus to building the capacity of local NGOs to do the<br />

legal clinic work themselves. <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> has done this<br />

through training, mentoring, and creating legal networks<br />

that allow partners to work with and learn from one<br />

another. Says Louis-Marie Nindorera, <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Rights</strong>’<br />

Burundi country director,“After several years of running<br />

legal clinics, <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> has the privilege of now<br />

being able to share its experience with local NGOs that<br />

are providing similar services to their communities.”<br />

<strong>The</strong>se clinics provide much-needed assistance. Sylvestre<br />

Mpawenayo, a counselor at <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Rights</strong>’ legal clinic in<br />

Ngozi, explained: “We often say in Burundi that justice<br />

is ill.With such a huge problem of poverty in Burundi,<br />

people are afraid to bring cases before the courts because<br />

they don’t have the means. Others are simply ignorant of<br />

their rights and when they have a problem they don’t<br />

know where to turn. <strong>The</strong> legal clinics are a source of<br />

information for common people. When we are able to<br />

help them by informing them of their rights, directing<br />

them to the appropriate authorities, or resolving their<br />

disputes, through mediation for instance, it is to the<br />

advantage of everyone and the parties pay nothing.”<br />

Moreover, stated Mathilde*, one of the clinic’s clients:<br />

“Paralegals are people who have accepted a certain level<br />

of legal responsibility vis-à-vis their community.<strong>The</strong>y are<br />

people whom we can trust.”<br />

Just last year, <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Rights</strong>-trained paralegals successfully<br />

obtained reparations for 24 families from Ngozi whose<br />

land had been expropriated by the government in 1992.<br />

Under Burundi’s Constitution, expropriation is legal if<br />

carried out in the public interest.Yet in reality, much of<br />

the confiscated land has been transferred to powerful<br />

military or political elites without compensation to the<br />

owners.And, in the years since the expropriations, much<br />

of this land has continued to change hands.Today, many<br />

of the original owners want to return, while those who<br />

purchased the land and hold title to it are reluctant to<br />

give away what they see as rightfully theirs.<br />

<strong>Long</strong> <strong>Road</strong> <strong>Home</strong>, continued on page 18<br />

Partners for Justice SPEAK OUT<br />

LUCIE NIZIGAMA<br />

Association of Women Lawyers<br />

Bujumbura, Burundi<br />

PROMOTING WOMEN’S LAND RIGHTS<br />

I think my desire to help women stems from my childhood.<br />

After my father passed away, his siblings took all of my<br />

family’s land. My mother was left with only a tiny parcel on<br />

which to raise our family. She struggled before the courts for<br />

years to obtain justice for us. Ever since then, I have felt that<br />

I wanted to do something to help women in similar situations.<br />

Early in my career, I was the first female magistrate in Karusi<br />

province. Almost all of the conflicts that came before me were<br />

land-related, and most had to do with inheritance disputes.<br />

Most often, a widow would initiate a case against her brotherin-law<br />

after he tried to take away all of her deceased<br />

husband’s land. I constantly was troubled by the fact that<br />

women in my courtroom were unable to express their<br />

concerns adequately.<br />

I decided to join the Association of Women Lawyers because<br />

I wanted to work directly with women on land-related issues. I<br />

have found that when local associations stand behind<br />

common people, authorities are more likely to resolve<br />

conflicts properly. Although the organization is now focused<br />

primarily on handling individual cases, we also are trying to<br />

influence public policy. Currently, we are working on a law<br />

protecting women’s inheritance rights.<br />

Through the networks it has developed, <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> has<br />

increased our ability to help people. One network in which we<br />

participate is designed for Burundian NGOs that run legal<br />

clinics for indigent communities. That network allows us to<br />

share experiences, learn from one another, and develop joint<br />

strategies. <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> also provides us with technical<br />

training in areas such as listening, mediation, and advocacy.<br />

With these tools, we are better able to serve our<br />

communities.<br />

<strong>The</strong> second <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> network in which we participate is<br />

for local organizations that want to influence lawmakers on<br />

specific human rights issues. Together, we already have<br />

proposed amendments to key pieces of legislation, such as<br />

the law establishing the Truth and Reconciliation<br />

Commission, the Electoral Law, and the Constitution. This<br />

type of work is new to most Burundian NGOs. But as the<br />

political context has changed and opportunities now exist for<br />

such initiatives, we have learned to do it by working alongside<br />

<strong>Global</strong> <strong>Rights</strong>.<br />

As part of these networks, we are better able to push our<br />

government to respect human rights. And pursuing these<br />

activities makes us feel strong. Slowly but surely, we can<br />

sense that our positions are being taken more seriously.<br />

<strong>Global</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> VOICES Summer 2005 7

<strong>Global</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> in BURUNDI<br />

INHERITING LAND<br />

“When one speaks of problems related to inheritance<br />

rights, we think immediately of land because land<br />

equals survival in Burundi,” says Espérance<br />

Musirimu, <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Rights</strong>’ program officer in<br />

Bujumbura. “Families never really quarrel about<br />

inheritance of any other belongings. Land is always<br />

the issue.”<br />

Because there is no codified inheritance law in<br />

Burundi, the issue is regulated by custom. And while<br />

custom varies from province to province, in most<br />

cases, women are at a distinct disadvantage. When a<br />

man dies, for example, custom in a number of areas<br />

dictates that his land is divided between only his<br />

male heirs. In other regions, women may inherit land,<br />

but only parcels half the size of what their male family<br />

members may get and without the right to sell what<br />

has been left to them. <strong>The</strong> case is particularly dire for<br />

widows, women abandoned by their husbands, and<br />

female divorcees whose land is frequently taken by<br />

their husbands or his family. Such a reality<br />

undermines the economic rights of Burundi’s women<br />

and diminishes strides toward gender equality.<br />

“<strong>The</strong>se problems are so prevalent that we assist<br />

female clients who are seeking to resolve<br />

inheritance-related land disputes on a daily basis,”<br />

said Clotilde Ngendakumana, program associate in<br />

<strong>Global</strong> <strong>Rights</strong>’ Ngozi legal clinic. “And in addition to<br />

providing legal services, we are now working with the<br />

Association des Femmes Juristes (Association of<br />

Women Lawyers) and a broader network of local<br />

NGOs to push for a national inheritance bill that would<br />

guarantee equality for women.”<br />

While women face disproportionate discrimination<br />

when it comes to inheriting land, the customs that<br />

regulate the issue cause problems for all Burundians,<br />

including men — signaling the need for<br />

comprehensive land policy reforms. As the population<br />

grows and parcels of land are sub-divided among<br />

heirs into ever-smaller plots that are no longer large<br />

enough for cultivating sufficient foodstuffs, the land<br />

loses its value. Donna-Fabiola Nshimirimana, <strong>Global</strong><br />

<strong>Rights</strong>’ program officer in Ngozi, explained: “A parcel<br />

of land that has been handed down to one man from<br />

his father will need to be divided between his<br />

offspring as well, and in most cases between the male<br />

children alone. Each will inherit a portion of the land<br />

and they too will bear children. When will they stop<br />

dividing the parcel?”<br />

18 Summer 2005 <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> VOICES<br />

<strong>Long</strong> <strong>Road</strong> <strong>Home</strong>, continued from page 7<br />

Charles*, a member of one of the families from Ngozi,<br />

told <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> that his home had been demolished<br />

by the government as part of a plan to rebuild and<br />

beautify the city’s main road. As he explained, “My<br />

father was born in that house … Today there are at least<br />

six houses on that same parcel of land. On it, I grew<br />

bananas, coffee, and various fruits. I earned my living<br />

there, just selling coffee.That was the only land I had.”<br />

Charles’ family never received official notification that<br />

the demolition was to take place and saw no<br />

paperwork certifying what had been done. <strong>The</strong>y were<br />

paid a small amount for what was on the land, but were<br />

given nothing for the land itself or for its incomegenerating<br />

potential.<br />

<strong>Global</strong> <strong>Rights</strong>-trained paralegals and counselors from<br />

the Ngozi legal clinic recently brought Charles’ case,<br />

and others like it, to the attention of local administrators<br />

and pushed parliamentarians to support those who had<br />

lost their land. In the end, the paralegals were able to<br />

obtain payment for the property that had been taken<br />

more than a decade before.As Charles explained,“I was<br />

stunned that I finally was compensated.”<br />

Several months ago, after hearing about <strong>Global</strong><br />

<strong>Rights</strong>’ Ngozi-based legal clinic from a paralegal in<br />

his community, Etienne stopped by. Since then,<br />

<strong>Global</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> has met with local officials and<br />

representatives of the National Committee for the<br />

Rehabilitation of Victims, seeking redress for his<br />

family’s loss. Working free of charge, the clinic has<br />

made clear that it will pursue all appropriate<br />

administrative, judicial, and mediation-oriented<br />

possibilities to find a solution to his problem. Before,<br />

Etienne said, because he was “dealing with a 30 year<br />

old problem, I sometimes felt that nothing could be<br />

done.” But now, he says, he is hopeful.<br />

JOIN THE<br />

GLOBAL RIGHTS MOVEMENT<br />

<strong>The</strong>re is much work to be done, and we need your<br />

help to do it. Your contribution to <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Rights</strong>:<br />

supports women struggling to achieve equality<br />

and personal freedom, fights racial discrimination<br />

in the United States and around the globe,<br />

strengthens the efforts of advocates working to<br />

bring to justice perpetrators of unspeakable war<br />

crimes, emboldens regional and global networks<br />

fighting human trafficking, and tells human rights<br />

activists risking their lives and their freedoms<br />

that they are not alone on their long walk!<br />

Use the enclosed giving envelope, email us at<br />

Development@<strong>Global</strong><strong>Rights</strong>.org, or give on-line<br />

at www.globlarights.org to invest in <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Rights</strong>.