41119_Niro jubilaeumsbog_blok_uk - GEA Niro

41119_Niro jubilaeumsbog_blok_uk - GEA Niro

41119_Niro jubilaeumsbog_blok_uk - GEA Niro

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>Niro</strong>

<strong>Niro</strong> – 75 years without borders<br />

Published by <strong>Niro</strong> to mark the company’s 75th anniversary<br />

Copenhagen 2008 · ©<strong>Niro</strong>

Milk plant, Argentina.

Congratulations on the 75 years 6<br />

Johan Ernst Nyrop: the man behind the success 8<br />

The man who invented the wheel 14<br />

<strong>Niro</strong>’s global network 18<br />

The American dream came true 20<br />

Times change 22<br />

From Lilliput to world player 25<br />

A partner on many fronts 26<br />

Small department, great success 32<br />

The challenges of drying milk 34<br />

In cowboy country 38<br />

Infant formula: a vital alternative 40<br />

Practical problem cracker 43<br />

How <strong>Niro</strong> stacks up in the environment 44<br />

The coffee chronicle 48<br />

Plastic is used everywhere 52<br />

<strong>Niro</strong> strikes while the iron is hot 54<br />

Little brother standing on his own two feet 56<br />

About development and technological milestones 60

Congratulations on the 75 years<br />

Dear friends and colleagues,<br />

No matter how you look at it, <strong>Niro</strong> has had a<br />

remarkable history! The company’s growth from<br />

its founding in 1933 through today shows its strength<br />

and value. <strong>Niro</strong> was an international company<br />

long before globalization became a buzzword.<br />

Even more importantly, as the articles in this book<br />

show, <strong>Niro</strong> has been a pioneer within a number<br />

of technologies that are necessary for people and<br />

societies across the world.<br />

<strong>Niro</strong>’s results are impressive, but just how exactly<br />

have we achieved them? First and foremost, we’d<br />

like to point to two areas: namely, our fantastic<br />

employees and our strong corporate culture. We’ve<br />

been in a position to be able to attract and educate<br />

the best engineers within our field, and many of<br />

them have made their careers within <strong>Niro</strong> and<br />

have shown great loyalty to the company.<br />

This 75th anniversary book should be seen as a<br />

tribute to the generations of outstanding <strong>Niro</strong><br />

employees who have contributed to our valued<br />

corporate culture.<br />

6 | 7<br />

Openness and flexibility<br />

It is a culture that is marked by professionalism, high<br />

working standards as well as the courage to think<br />

innovatively – and not least of all the willingness<br />

to travel around the world in search of new opportunities.<br />

<strong>Niro</strong>’s employees have the right entrepreneurial<br />

spirit and are prepared to solve technological<br />

challenges, which makes us open to and flexible<br />

regarding new initiatives. These characteristics<br />

contributed to making us a global player and<br />

technological leader, and they made <strong>Niro</strong> attractive<br />

to <strong>GEA</strong> in 1993.<br />

<strong>Niro</strong>’s fundamental strengths are still the same.<br />

They have been an important tool as we’ve become<br />

part of <strong>GEA</strong>’s success, and they are the key to our<br />

future development.<br />

International collaboration<br />

In a world that is becoming increasingly globalized,<br />

we face new opportunities and challenges, and <strong>Niro</strong><br />

is well equipped to handle both. While we used to<br />

send Danish engineers and management abroad to<br />

handle the buildup of our sister companies, today

the <strong>Niro</strong> group has success completing projects by<br />

virtue of local collaborators.<br />

<strong>Niro</strong> now works with Strategic Business Units (SBU),<br />

where cross-collaboration within all essential industries<br />

gives greater focus and flexibility to pursue<br />

the same goals and create better results.<br />

Engineering a difference<br />

The initiatives we have underway clearly show that<br />

our pioneering spirit is still alive and well, and we’re<br />

firmly determined to continue to make a difference.<br />

The world has a pressing need for greater capacity<br />

for the processing of foodstuffs. We have extensive<br />

experience within sanitary drying technology, and<br />

in the future there will be opportunities for <strong>Niro</strong>,<br />

especially in regions undergoing great development,<br />

such as Asia and South America.<br />

The global focus on the environment and energy is<br />

expected to continue for many more years. Today<br />

our flue gas cleaning technology for power plants<br />

helps make the air cleaner many places in the world,<br />

and <strong>Niro</strong> will play a great role here in the future<br />

as well.<br />

<strong>Niro</strong>’s capacity for innovation within the chemical,<br />

food and pharma segments means that our expertise<br />

will make a difference in the future, too.<br />

To sum it up, our future looks just as exciting as<br />

our past. If we maintain our ability to meet new<br />

challenges and explore new ideas, if we continue<br />

to emphasize innovation and individual initiatives,<br />

and if we live up to our shared values, the next 75<br />

years will bring a collection of articles that are<br />

just as inspiring as this book.<br />

Very best regards<br />

Anders Wilhjelm<br />

Michael Andersen<br />

Niels Erik Olsen<br />

Kristian Skaarup

Johan Ernst Nyrop: the man behind the success<br />

By Christian Schwartzbach<br />

It wasn’t written in the stars November 10, 1933 that the<br />

company A/S <strong>Niro</strong> Atomizer, established at a meeting in a<br />

lawyer’s office in Copenhagen, would be a prolonged success.<br />

Around the globe, depression and unemployment prevailed<br />

after World War I and the Great Stock Market Crash.<br />

Denmark’s southern neighbor, Germany, was going through<br />

political upheaval that would have catastrophic consequences<br />

for the entire world. Yet there must have been a sense of<br />

optimism and courage among the assembly of enterprising<br />

men at their meeting in attorney Kaj Seth Oppenhejm’s office.<br />

The key person was engineer Johan Ernst Nyrop. His technical<br />

and scientific knowledge had resulted in a number of inventions<br />

and patents, the business potential of which must<br />

have given rise to optimism. A third important participant<br />

was banker Erik Birger Christensen, who had both capital<br />

available and faith in Nyrop.<br />

Johan Ernst Nyrop was born in 1892 and earned his M.Sc.<br />

in engineering in 1917. He was inventive, enterprising and<br />

innovative. As a young man he and his friend Einar Dessau<br />

experimented with broadcasting, among other things, and<br />

he took out his first patent for the telephone telegraph in 1911.<br />

8 | 9<br />

A tough beginning<br />

Nyrop participated in the establishment of the Danish<br />

Medicinal and Chemical Company A/S in 1919. In the 1920s<br />

he became interested in the spray drying of liquids, and in<br />

1924 he established both a Danish company, A/S <strong>Niro</strong>, and<br />

an English company, Nyrop Dehydrator, to make use of his<br />

new knowledge. That same year, he got a patent for a rotating<br />

atomizer.<br />

The times were hardly favorable, and since finances were<br />

not Nyrop’s strong suit, his efforts ended a few years later in<br />

bankruptcy and great personal loss. During that same time,<br />

Johan Ernst Nyrop cultivated his academic interests and<br />

wrote articles and books about the catalytic effect of metallic<br />

surfaces. In the early 1930s, he submitted a doctoral thesis<br />

on this topic. The fact that this thesis was rejected, together<br />

with the aforementioned bankruptcy, contributed to Nyrop<br />

seeking new challenges.

Johan E. Nyrop, founder of A/S <strong>Niro</strong> Atomizer.<br />

<strong>Niro</strong>’s building in Hellerup, Denmark,<br />

in the 1940s.

Hjalmar Bang, Managing Director<br />

from 1948-1971.<br />

10 | 11<br />

Indoor spray drying plant in wood<br />

from the late 1940s.

Fortunately, he had influential friends who were able to see<br />

the possibilities in his ideas and patents, and this resulted in<br />

the establishment of A/S <strong>Niro</strong> Atomizer in 1933. Nyrop had<br />

invaluable support in banker Erik Birger Christensen, who<br />

had gotten to know Nyrop through projects about agricultural<br />

products.<br />

Birger Christensen became a decisive person in the history<br />

of <strong>Niro</strong> Atomizer in many ways; during the early years mainly<br />

as financer, and later as a member of the board of directors<br />

with several important contributions. The first board had<br />

attorney Kaj Seth Oppenhejm as chairperson.<br />

On the road to success<br />

Nyrop himself had to come to terms with a position as<br />

consultant and shareholder. Because he previously had gone<br />

bankrupt, he could no longer sit on the board. Nils Brorsen<br />

worked the next five years as business manager. The total<br />

share capital was DKK 12,000, of which Nyrop owned a third.<br />

The deed of foundation carefully specifies that the consultant,<br />

engineer Johan Ernst Nyrop, should only be paid by<br />

the yield of his share of the share capital. Therefore, J.E.<br />

Nyrop did not deposit cash capital, but solely patents and<br />

rights.<br />

There is very little to be found in the delivered documentation<br />

about the course of the company during the early years.<br />

Johan Ernst Nyrop was the driving force and succeeded in<br />

securing orders for spray drying plants in Denmark and<br />

abroad. The dried products were milk, blood, eggs, feedstuff<br />

and soap.<br />

The large industrial company Titan A/S on Tagensvej in<br />

Copenhagen was from the beginning both a shareholder,<br />

with a sixth part of the share capital, and a supplier. Titan<br />

A/S made office space and workshops available and produced<br />

atomizers according to Nyrop’s instructions. The fundamental<br />

principle of <strong>Niro</strong> Atomizer from the beginning and for many<br />

years was that they constructed the plants, but left the production<br />

of the components to sub-suppliers.<br />

Standard components were bought at specialist firms, while<br />

specialized components were manufactured at different<br />

workshops in Denmark according to <strong>Niro</strong> Atomizer’s designs.<br />

For many years, the drying chambers were manufactured of<br />

wood and coated with galvanized plates inside. Not until<br />

later was stainless steel used. The technical side of the plants<br />

was completely Nyrop’s responsibility. Despite his creativity,<br />

he was quite conservative when it came to plant design.<br />

Atomization was carried out, without exception, with the<br />

rotating atomizer invented by Nyrop and drying air supplied<br />

through a central pipe with a dispersion device on the tip.<br />

Nyrop stuck to this design until his death in 1959. Without<br />

doubt, the fact that they didn’t throw themselves into questionable<br />

experiments prevented a number of difficulties for <strong>Niro</strong><br />

Atomizer; but when others took over technical management<br />

after Nyrop’s death, the time had come for new developments.<br />

History subsequently has also proven that it was necessary.<br />

Change and progress<br />

In 1938 <strong>Niro</strong> Atomizer got its own premises in Emdrupborg,<br />

with room for a research facility. In 1942 a better-suited location<br />

was found in a large villa on Aurehøjvej in Hellerup.<br />

By 1943 <strong>Niro</strong> Atomizer had acquired roughly 150 orders for<br />

spray drying plants. The palette of different products had<br />

grown significantly. The company’s results fluctuated greatly<br />

the first 12 years, and journal notes show significant additional<br />

expenses in connection with troubleshooting of individual<br />

plants. Concern about Johan Ernst Nyrop’s expense account<br />

is also expressed.

After the end of World War II, a longer period of sizeable<br />

profits began. This new period also included significant<br />

organizational changes. The business manager until that<br />

point, engineer K.J.S. Jensen, who had led <strong>Niro</strong> Atomizer<br />

through the risky years, left the company in 1947 after<br />

disagreements with the board. Shortly thereafter he founded<br />

the company Anhydro.<br />

Hjalmar Bang entered the company that same year as both<br />

shareholder, member of the board and daily manager. From<br />

a business standpoint, Bang was very experienced and dyna-<br />

12 | 13<br />

mic and initiated progress that Nyrop hardly could have<br />

achieved. Director Bang became a legendary leader of <strong>Niro</strong><br />

Atomizer’s expansion until 1971, when he retired and replaced<br />

K.S. Oppenhejm as chairperson.<br />

Hjalmer Bang was a personality on the same level as founder<br />

Johan Ernst Nyrop. Until Nyrop’s death in 1959, however,<br />

Johan Ernst Nyrop remained the central character in <strong>Niro</strong><br />

Atomizer. He entered the board in 1955 and must have been<br />

pleased with the progress his pri ncipal work created on the<br />

global scene.<br />

From left: J.E. Nyrop and Mrs. Nyrop,<br />

K.S. Oppenheim and Harry Larsen,<br />

later Managing Director of<br />

A/S <strong>Niro</strong> Atomizer.

A/S <strong>Niro</strong> Atomizer’s first building at<br />

Gladsaxevej 305 in Soeborg,<br />

Denmark, in 1957.<br />

A/S <strong>Niro</strong> Atomizer’s main building (today building B) from 1960.

The man who invented the wheel<br />

Engineer Kaj Nielsen has been almost as important to the<br />

development of <strong>Niro</strong> as its founder, Johan Ernst Nyrop. He was the<br />

man who, among other things, invented a durable atomizer wheel<br />

– later dubbed the KN-wheel.<br />

14 | 15<br />

Durable atomizer wheel for<br />

drying products that cause<br />

wear and tear.

KN are the initials of a very important person in the history<br />

of <strong>Niro</strong> Atomizer. His name was Kaj Nielsen. In 1962, at only<br />

age 36, engineer Kaj Nielsen, M.Sc., D. Tech., left the Danish<br />

Soy Cake Factory to join <strong>Niro</strong> Atomizer as head of research<br />

and development. His intended role was to replace Johan<br />

Ernst Nyrop as technical anchorman. And he played that role<br />

quite decisively. Johan Ernst Nyrop left an indelible stamp<br />

on the companies he established. Nyrop Dehydrator got his<br />

exact name, while A/S <strong>Niro</strong> got a name that obviously was<br />

derived from the English pronunciation of the name.<br />

By Christian Schwartzbach<br />

It was probably Nyrop’s intention that the company reestablished<br />

in 1933 be named A/S <strong>Niro</strong>. But a dispute with the<br />

German Krupp Group got in the way. Krupp used the name<br />

<strong>Niro</strong> as the brand for its line of stainless steel products. The<br />

outcome was that the company was named A/S <strong>Niro</strong> Atomizer,<br />

and it proved to be a durable name. Even in the year of its<br />

75th anniversary, the old name is still remembered by many<br />

people.<br />

The durable atomizer wheel<br />

Even though Johan Ernst Nyrop’s creativity continued for<br />

many years, it never resulted in a single invention or component<br />

for a spray drying plant carrying his name. With<br />

only one exception, the same can be said for other creative<br />

<strong>Niro</strong> Atomizer employees. The exception is the KN-wheel,<br />

and it belongs to the period after Nyrop’s death. While<br />

Johan Ernst Nyrop was quite conservative and with few<br />

exceptions stuck to the design of the plants he had chosen<br />

from the start, Kaj Nielsen was more open-minded and<br />

initiated a number of new developments.<br />

The area where Kaj Nielsen made his mark, and which still<br />

carries his name, was spray drying of liquids containing<br />

sharp, firm particles, which expose the rotating atomizer<br />

wheel to great wear and abrasion. This doesn’t apply to<br />

traditional products like milk, blood, eggs, feedstuff and<br />

soap; but in the beginning of the 1940s and ‘50s, products<br />

like ceramics, kaolin and tile clay became more prevalent.<br />

This was a new challenge for Nyrop, which resulted in the<br />

development of the first truly durable atomizer wheel,<br />

which was patented in 1956 with Nyrop as co-inventor.<br />

Kaj Nielsen, inventor of the durable<br />

atomizer wheel, the KN-wheel.

Applications in many areas<br />

This type of wheel was an improved version of the existing<br />

type, since hard metal plates were placed on the wheel<br />

where the wear occurred. This solution must have worked<br />

satisfactorily for a period of time, because not until many<br />

years later did a serious wear problem occur again – this<br />

time on two plants delivered in 1962 to what was then<br />

called Czechoslovakia. The product was tile clay for the<br />

manufacturing of glazed wall and floor tiles. As one of his<br />

first big assignments, Kaj Nielsen had to come up with a<br />

solution, and the result was what later came to be called the<br />

KN-wheel. Over the course of the following years, the invention<br />

helped open new markets, initially in the former Soviet<br />

Union, where the Russians had tried to build a number of<br />

large spray drying plants for double superphosphate themselves,<br />

but had failed because of wear and abrasion.<br />

The atomizer wheel is the heart of a spray drying plant.<br />

16 | 17<br />

New atomizers from <strong>Niro</strong> Atomizer with KN-wheels solved<br />

the problem. The next market to open up was the mining<br />

industry. Spray drying was excellent to use for the drying of<br />

mined nickel and copper concentrate. Significant orders were<br />

secured in Australia, the U.S., South Africa, Botswana and the<br />

Soviet Union. It is part of the story about <strong>Niro</strong> Atomizer and<br />

Kaj Nielsen that the development of the large F-600 atomizer<br />

plant began during his time, and that the combination of<br />

this large atomizer, now the F-800 and F-1000, with the KNwheel<br />

is the foundation for <strong>Niro</strong>’s leading position in another<br />

important market: flue gas cleaning by the spray drying<br />

method. Kaj Nielsen was appointed deputy director in 1965.<br />

Unfortunately, he didn’t live to see all the success his efforts<br />

led to. Kaj Nielsen died in 1970, at age 43. The few who still<br />

remember him talk about KN with fondness.

A spray drying plant for copper and nickel concentrate.

<strong>Niro</strong>’s global network<br />

Since the company’s founding in 1933, <strong>Niro</strong>’s family of subsidiary<br />

and sister companies has grown to become large and closely knitted.<br />

Johan Ernst Nyrop was very globally oriented and had already<br />

prior to the establishment of A/S <strong>Niro</strong> Atomizer spent a great<br />

deal of time in England. So when Johan Ernst Nyrop established<br />

<strong>Niro</strong> in 1933, the intention was for the company in the<br />

long run to have offices or agents in countries all around the<br />

world. The first agents <strong>Niro</strong> used were the same agents and<br />

contacts the old Danish machinery and hydro-extractor factory<br />

Titan A/S used. Part of that story is the fact that Titan A/S,<br />

besides producing Nyrop’s early atomizers in 1925, also made<br />

office space and workshops available during <strong>Niro</strong>’s early years.<br />

Therefore there was a natural and very close connection to<br />

Titan A/S, and the fact that Johan Ernst Nyrop's brother Aage<br />

was among the employees at Titan A/S did not harm the<br />

connection.<br />

In time, <strong>Niro</strong> established contacts itself, set up agencies and<br />

provided licenses for foreign companies. <strong>Niro</strong>’s first subsidiary<br />

was established by somewhat of a coincidence in France in<br />

Brazil<br />

18 | 19<br />

1952-53. <strong>Niro</strong>’s former agent and licensee had violated the<br />

contract, so in order to maintain <strong>Niro</strong>’s office and service in<br />

the French market, they denounced the license and the agency<br />

agreement and formed their own company in France. Now<br />

the foundation was laid for foreign subsidiary companies,<br />

which were established gradually as the need arose.<br />

The reasons for the establishment of the subsidiary companies<br />

are many: one was established because <strong>Niro</strong> had three agencies<br />

in one country who got into a fight over customers. Some<br />

companies were established because there suddenly was an<br />

increase in the sale of a specific type of plant. And others were<br />

established because it was impossible to import plants, which<br />

therefore needed to be manufactured locally, or because the<br />

traveling time would be too long if employees had to travel<br />

from Denmark. Today, transportation times and technical<br />

trade barriers are, after all, less than they used to be.<br />

Australia<br />

The photos in this<br />

article show some<br />

of our former<br />

subsidiary<br />

companies.

France<br />

England New Zealand<br />

By Sten Warburg

The American dream came true<br />

The American part of <strong>Niro</strong>, <strong>Niro</strong> Inc., did not have the best odds for<br />

success in the U.S. But hard work, great skills and a good understanding<br />

of American culture have turned <strong>Niro</strong> Inc. into a success story.<br />

<strong>Niro</strong>’s American sister company, <strong>Niro</strong> Inc., in Maryland.<br />

20 | 21

Three plants in a row from the 1960s for the mining industry in the U.S.<br />

By Jens Thousig Møller<br />

When <strong>Niro</strong> set foot on American soil for the first time in<br />

1946 to seek its fortune, like so many others, in the Promised<br />

Land, it did not immediately seem as though it would be a<br />

success. But hard work and a solid investment in good employees<br />

and infrastructure eventually made the foundation<br />

for the well-established company <strong>Niro</strong> Inc. From the start,<br />

<strong>Niro</strong> entered a partnership with the company Nichols, which<br />

was already an established name in the American market.<br />

After ending the partnership in 1975, <strong>Niro</strong> Corporation, as it<br />

was named back then, decided to go solo.<br />

<strong>Niro</strong> Inc. has developed into a genuine American company<br />

over the years, on the one hand benefitting from technical<br />

support from Denmark, and on the other having understood<br />

American business culture and customers. Today <strong>Niro</strong> Inc.<br />

encompasses nearly 400 employees, many of whom have<br />

more than 20 years of experience at <strong>Niro</strong>. <strong>Niro</strong> Inc. has expertise<br />

that covers all of <strong>Niro</strong>’s business units within food<br />

and dairy, pharma and the chemical industry. Competencies<br />

include sales, plant design, project management and products,<br />

and <strong>Niro</strong> Inc. has independent storage, workshop, research<br />

and development facilities. Over the course of the years,<br />

<strong>Niro</strong> Inc. has adjusted to the opportunities in changing<br />

markets and with its initiatives contributed to <strong>Niro</strong>’s global<br />

success.

Times change<br />

22 | 23<br />

Many of <strong>Niro</strong>’s employees travel around the world<br />

as part of their job. Here the oldest member of<br />

<strong>Niro</strong>’s senior club tells about one of his experiences<br />

from when Europe was still divided into<br />

East and West by the wall.

Times change, and I guess it’s a good thing – especially if the<br />

changes mean better times. But it may be worth remembering<br />

what it was like to work for <strong>Niro</strong> during the Cold War. In<br />

the happy days of the 1950s, Europe was divided by the<br />

so-called Iron Curtain into Eastern and Western Europe.<br />

At some point we got an order for a plant for the drying of<br />

sulphonated fat alcohol from a petrochemical factory in<br />

what was then called Czechoslovakia – today Slovakia. The<br />

factory was hidden in a beautiful wooded area in the mountains,<br />

close to a little village called Dubova.<br />

The legendary engineer Hoegsberg was responsible for the<br />

assembling, and I was to start up the plant. This was my first<br />

visit behind the Iron Curtain, and I was of course a bit excited<br />

about how it would turn out. I arrived at Prague in the middle<br />

of the day and was greeted by a representative of the company,<br />

which had its head office in Prague. However, I was<br />

not going to spend the night there, but was taking the night<br />

train far eastwards. The representative provided me with<br />

money and a train ticket and then hurried away. He didn’t<br />

want to be seen with a westerner longer than necessary.<br />

On the train I met two gentlemen from the factory who had<br />

been briefed about my trip. They had the neighboring com-<br />

Af Jørgen Wulff<br />

partment and invited me to join them for some good Czech<br />

beer. We discussed quite openly the conditions of the country,<br />

which I should not have done. One of the gentlemen turned<br />

out to be the chairman of the local communist cell. The next<br />

morning I was greeted at the station by Hoegsberg. He told<br />

me that for the first month he had been afraid to talk to<br />

anyone at the factory about anything but professional stuff.<br />

He had as his interpreter an old guy who had worked in<br />

Canada as a lumberjack in his younger days, and therefore<br />

spoke English well enough to be a good interpreter for us.<br />

The village inn was undergoing renovation, but the owner<br />

of the inn lived across the street in a villa. Hoegsberg had a<br />

small room here that I took over after his departure. There<br />

was a toilet, but no running water. I had to use my washing<br />

water to flush the toilet. On Monday, I had to go with my<br />

interpreter to the closest main city, where there was a police<br />

station. I was going to get a visa. Over the following years,<br />

during my trips to Eastern Europe, I realized that it wasn’t<br />

enough to get an entry visa. No, you needed an exit visa as<br />

well when you wanted to leave the country. Bureaucracy<br />

with a vengeance.

The start up of the plant was not without problems. Something<br />

was wrong when we couldn’t achieve the calculated dry air<br />

quantity. A valve must have been mounted incorrectly, or<br />

there had to be a blockage of the air supply pipe. But no,<br />

that wasn’t the case. Then I disassembled the suction ventilator<br />

and noted that the paddle wheel was laterally reversed. Now<br />

the situation was desperate, but I succeeded in rebuilding<br />

the suction ventilator, and then it worked.<br />

As time went on everything worked, and the staff was able<br />

to manage the operations. But they were not willing to let<br />

me go, because then the plant became their own responsibility.<br />

They dragged their feet, and I considered asking <strong>Niro</strong> to send<br />

a telegram to the factory saying they needed me at home.<br />

But suddenly they couldn’t get a connection to Denmark, or<br />

so they claimed. But I could give them a message, and then<br />

they would call Prague and ask them to deliver it. Of course<br />

that was not possible, so I had to hang in there. Finally they<br />

couldn’t keep me there anymore, and again I went to the police<br />

station, where I got an exit visa.<br />

Upon my departure from the factory, however, the manager<br />

of the factory took it away from me, because he wanted<br />

proof that I had actually been there. So I took the night<br />

train back to Prague, from where I was flying back to<br />

24 | 25<br />

Copenhagen. As the time for my departure drew nearer, we<br />

were called one by one into passport control. When it was<br />

my turn I was in trouble, because I didn’t have an exit visa.<br />

I suggested that they call the company in Prague to verify<br />

my identity. They did try that, I think, but the office was<br />

closed, since it was past four o’clock. We argued in English,<br />

German and the small amount of Czech that I knew, but it<br />

didn’t do me any good. I was held back, while the other<br />

passengers were attended to.<br />

I realized that I would be put in jail without the possibility<br />

of notifying Denmark. I was hoping that the infamous exit<br />

visa could be provided by the next day, so that I could get<br />

out of the Iron Curtain. But then everything was suddenly<br />

alright. I was one big question mark, but the explanation<br />

was easy. The commissar was tired of arguing and had left<br />

the room, and then the passport officer was not afraid to<br />

give me the precious stamp in my passport. It was an unpleasant<br />

event, and later that evening when I was home in<br />

my garden in Virum, I enjoyed the freedom. I had come to<br />

realize how good it was to live on the western side of the<br />

Iron Curtain. And as a little ironic postscript: today you<br />

can travel to 24 Schengen countries without a passport. Yes,<br />

times do change.

From Lilliput to world player By Christian Schwartzbach<br />

<strong>Niro</strong> started out as a Danish corporation with DKK 12,000 in<br />

capital. Today it is a world leader within the global market for<br />

spray drying plants.<br />

When <strong>Niro</strong> was established as the corporation A/S <strong>Niro</strong> Ato -<br />

mizer in 1933, the four shareholders contributed a modest<br />

DKK 12,000 in total. The shares were divided in this way:<br />

J.E. Nyrop and wife, DKK 4,400; Titan A/S, DKK 2,000; the<br />

clients of K.S. Oppenhejm, DKK 3,600; and Dr. Viggo Schmidt<br />

and wife, DKK 2,000.<br />

Titan A/S was only a minor shareholder, even though the<br />

company as a supplier of atomizers clearly had an interest<br />

in <strong>Niro</strong>. There is reason to believe that Paul Hannover, the<br />

director of Titan A/S, was not interested in getting personally<br />

involved in the risky project.<br />

Under the name “the clients of K.S. Openhejm” was the investment<br />

company Kipa, which was owned by Erik Birger Christensen.<br />

Dr. Viggo Schmidt was a well-known chief physician<br />

at that time and a friend of Johan Ernst Nyrop. As is apparent,<br />

the group of investors was limited and willing to take a risk.<br />

From 12,000 to 1 million<br />

Over the next 25 years, the share capital in A/S <strong>Niro</strong> Atomizer<br />

increased manifold. A statement from 1958 shows that <strong>Niro</strong>’s<br />

shareholders had stock with the value of DKK 1 million. The<br />

value of the company had risen significantly since the company’s<br />

founding in 1933. The big financial backers were Erik<br />

Birger Christensen, Hjalmar Bang and Nichols Engineering,<br />

<strong>Niro</strong>’s partner on the American market.<br />

In 1968 director H. Brüniche-Olsen joined the board, after<br />

the Danish Sugar Factories (DSF) had acquired a larger block<br />

of shares. Their block of shares was expanded in 1974, when<br />

<strong>Niro</strong> Inc. was established, and Nichols sold their shares.<br />

Brünich-Olsen became chairman of the board in 1978, when<br />

DSF took over all shares, which at that time had a value of<br />

DKK 45 million. <strong>Niro</strong> Atomizer became a subsidiary of DSF.<br />

In 1989 DSF, the Distilleries and Danisco merged into one<br />

company under the name Danisco A/S. <strong>Niro</strong> Atomizer became<br />

a subsidiary of Danisco and changed its name to <strong>Niro</strong> A/S.<br />

In 1993 <strong>Niro</strong> was sold to the German industrial enterprise <strong>GEA</strong><br />

in Bochum, which at that time was owned by the Happel<br />

family and headed by Dr. Otto Happel. At that point, share<br />

capital in <strong>Niro</strong> was roughly DKK 150 million. The strategic reason<br />

behind the purchase was, according to Volker Hannemann,<br />

head of <strong>GEA</strong>, that <strong>GEA</strong> needed the international experience<br />

that <strong>Niro</strong> had, in addition to its leading position on the world<br />

market for spray drying. Volker Hannemann became the<br />

chairman of <strong>Niro</strong>’s board in the period 1993-94, and today<br />

<strong>Niro</strong> has a central position in the <strong>GEA</strong> organization.<br />

The head office of the <strong>GEA</strong> Group in Bochum, Germany.

A partner on many fronts<br />

<strong>Niro</strong> has been part of the production of more everyday products than most<br />

end-users probably know – because many products today have to be<br />

long-lasting, cheap to transport and still maintain a high level of quality.<br />

Now serving: 10 good reasons why our customers use <strong>Niro</strong>’s technology.<br />

In 2001-2002, global coffee production constituted<br />

more than 6.6 billion tons of green beans.<br />

This corresponds to one trillion cups of coffee.<br />

26 | 27<br />

About 10 billion tons of milk powder were<br />

produced around the world in 2007. Spray<br />

drying of milk extends the shelf life and<br />

reduces transportation costs.

The red berries in cornflakes are dried in a <strong>Niro</strong> freeze dryer.<br />

Nearly all soups and sauces in powder form are spray dried.<br />

By Harald Klementsen

The WHO estimates that up to 50 percent of the vaccines given in<br />

third-world countries have no effect, because they’re not stored in<br />

a cool place. By removing the water through spray drying, storage in<br />

a refrigerator becomes unnecessary.<br />

28 | 29<br />

The blue color in a pair of jeans has<br />

been through a spray dryer.<br />

The basis for the white color in paint is<br />

spray dried titanium dioxide.

A lot of medication does not taste good – for example, vitamin pills for adults.<br />

In the spray drying process it is possible to hide the unpleasant taste by<br />

“coating” – that is, covering the pill with a substance that tastes good.

The raw material that is used all over the world for the manufacturing<br />

of plastic has been through a spray or fluid bed dryer.<br />

30 | 31

Tools made of hard metal, like a drill, are typically<br />

produced with spray dried wolfram carbide.

Small department, great success<br />

<strong>Niro</strong>’s Small Scale Plants department,<br />

which sells laboratory-sized spray<br />

drying plants, has sold more than<br />

3,000 of the two most popular plants<br />

since 1968.<br />

PRODUCTION MINOR spray dryer, one of <strong>Niro</strong>’s best-selling pilot plants.<br />

32 | 33<br />

November 14, 2002 was a big day for the Small Scale Plants<br />

department (SSP) at <strong>Niro</strong>. This was the day the department<br />

could celebrate the sale of MOBILE MINOR plant No.<br />

2,000, which was sold to an English company. The plant was<br />

placed in <strong>Niro</strong>’s reception area on January 6, 2003, and the<br />

next morning it was handed over to the customer.<br />

MOBILE MINOR, which is a laboratory-sized spray drying<br />

plant on wheels, was first introduced in 1948 and is actually<br />

older than its department, SSP. SSP is a continuation of the<br />

original department, the PM department, which was established<br />

in 1968 when the sales, order and service functions<br />

for small drying plants were unified. SSP delivers plants to<br />

all the industries that <strong>Niro</strong> covers, and its primary customers<br />

are educational institutions and development departments<br />

in companies. The plants are used to develop new products,<br />

for small-scale production, and to manufacture product<br />

samples for the companies’ own clients.<br />

The MOBILE MINOR spray dryer and the PRODUCTION<br />

MINOR spray dryer are SSP’s greatest successes. In a<br />

spray drying context, both plants are capable of producing<br />

only relatively small amounts of end product. The MOBILE<br />

MINOR spray dryer is able to dry a few kilos of product<br />

per hour, while the PRODUCTION MINOR has the capacity<br />

to produce up to 32 kilos. In comparison, a number of the<br />

big milk and coffee spray drying plants produce several<br />

tons per hour. The latter is from the end of the 1950s, and<br />

more than 1,000 PRODUCTION MINOR spray dryers have<br />

been sold. <strong>Niro</strong>’s Pharma Division originally began as part<br />

of the SSP department about 20 years ago, and at that time<br />

was only a small part of SSP. Later, sales to the pharmaceutical<br />

industry became so significant that an independent Pharma<br />

Division (the H-Division) was established. But that’s another<br />

story.

MOBILE MINOR number 2,000 – sold in 2002.<br />

By Per Puggaard and Gunnar Petersen

The challenges of drying milk<br />

Born on a Friday the 13th and fled from the communist regime<br />

with his family on October 13, 1968 at 1300 hours was perhaps<br />

not the most optimistic basis for a great career as head of <strong>Niro</strong>’s<br />

milk development department. But Jan Pisecký from the Czech<br />

Republic had other plans.<br />

With a background as a chemical engineer from the Technical<br />

University of Prague and a Ph.D. degree thereafter, Jan Pisecký<br />

became head of the Czech Dairy Research Institute – a position<br />

which for political reasons was intolerable to him. Until<br />

1968 there had not been many development projects at <strong>Niro</strong><br />

for milk powder spray plants, but after Jan Piceský was<br />

hired, things started to happen.<br />

The first challenge for <strong>Niro</strong> was to make a whole milk powder,<br />

which contains milk fat, soluble in cold water.<br />

Some of the milk fat is forced out onto the surface of the<br />

powder particles, which makes the particles water-repellent<br />

– especially when the water is cold. One of the requirements<br />

was that only “natural ingredients” which the milk already<br />

contained were allowed to be added. This sounded easy, but<br />

it took more than a year for two employees to take the process<br />

from the laboratory to an industrial plant that could produce<br />

a whole milk powder that was cold water-soluble.<br />

The task was solved by spraying a lecithin solution on the<br />

surface of the milk powder particles – a process that customers<br />

lined up to buy.<br />

34 | 35<br />

Need for product quality among customers<br />

Some of the development projects were inspired by the need<br />

to solve customers’ problems with product quality. The<br />

biggest problem was the density of the milk powder. Almost<br />

all of <strong>Niro</strong>’s milk plants were based on atomization of the<br />

fluid milk concentrate into small particles with a rotating<br />

ato mizer; that is, a component that converts the liquid into<br />

particles, which are then dried to powder.<br />

This resulted in a lighter powder than the one our competitors<br />

– especially from the U.S. and Japan – could produce. Not<br />

even <strong>Niro</strong>’s famous, patented “milk wheel” was able to solve<br />

the problem of product quality. During the energy crisis in<br />

the 1970s, when saving energy was a requirement, plants<br />

able to dry the powder in two steps were developed, since it<br />

is cheaper to remove the residual moisture in a vibrating<br />

after-dryer – called a VIBRO-FLUIDIZER ® – compared to a<br />

spray drying plant.<br />

Two-step drying, as it was called, provided better drying<br />

economy but also a heavier powder. With <strong>Niro</strong>’s high-pressure<br />

nozzles the powder became even heavier, and <strong>Niro</strong> was ahead<br />

of the competition again. But the development activities<br />

didn’t stop there. Customers required even better drying<br />

economy and higher quality drying, and showed interest

Jan Pisecký’s book, “Handbook of Milk<br />

Powder Manufacture,” from 1997.<br />

One of the world’s biggest spray drying plants<br />

for whole milk powder, a Multi-Stage Dryer<br />

– MSD, was developed by Jan Pisecký.<br />

By Vagn Westergaard

36 | 37<br />

An “instantizer,” here a VIBRO-FLUIDIZER at a modern milk<br />

powder factory in Vimmerby, Sweden.

in drying new products that couldn’t be dried by existing<br />

plants because of their high fat content. Thus a completely<br />

new plant concept was born. The MSD plant (Multi-Stage<br />

Dryer) was born in 1976. The ingenious aspect of this multiple<br />

step drying plant was the fact that a fluid bed was mounted<br />

in the base of the drying chamber; the moist powder from<br />

the drying chamber was caught by the dry powder in the fluid<br />

bed, preventing deposits in the drying chamber. It also became<br />

possible to dry products with a high fat content. <strong>Niro</strong> had once<br />

again positioned itself as the leading supplier of modern spray<br />

drying equipment, and the customers were standing in line.<br />

The COMPACT DRYER plant is born<br />

<strong>Niro</strong> management was not completely satisfied, however; the<br />

new wave of development in the latter half of the 1970s meant<br />

that more and more plants were delivered with high-pressure<br />

nozzles and not with the rotating atomizer that <strong>Niro</strong> was<br />

famous for. They had to invent a plant with a rotating atomizer<br />

and a static fluid bed. The solution became an old-fashioned,<br />

conventional plant where the conical bottom of the drying<br />

chamber was cut off and replaced by a ring-shaped static<br />

fluid bed.<br />

The COMPACT DRYER plant was born, and it became the<br />

basis for the rebuilding of many old plants, where the result<br />

in part was improved production capacity and at the same<br />

time an improved product in every way. On top of that came<br />

energy savings of 20 percent per kilo of produced powder.<br />

Many of Jan Pisecký’s “disciples” are still working on the<br />

development of <strong>Niro</strong>’s milk plants, highly inspired by him,<br />

along with their own ideas and new opportunities using advanced<br />

computer technology. That still makes <strong>Niro</strong>’s plants<br />

leading as far as technology, design and product quality are<br />

concerned.<br />

Operators in the control room.

In cowboy country<br />

Jens Thousig Moeller was one of the Danish employees who<br />

became part of <strong>Niro</strong>’s success in America. Here he recounts<br />

his experiences stationed in the U.S. in the 1970s.<br />

The year was 1974, with the energy crisis and car-free Sundays.<br />

After six good years in the development department and<br />

research laboratory at <strong>Niro</strong>, it was time for a change. Suddenly<br />

there was an exciting opportunity: working in another country,<br />

moving with my family to an unfamiliar place – to the land<br />

of cowboys and Indians, no less. Rent out the house, pack the<br />

moving boxes and buy a house in beautiful Maryland, in the<br />

newly developed and energetic city of Columbia, which was<br />

just the right place for the office. It became a wonderful “<br />

pioneer camp” with team spirit, long days with interesting<br />

projects and enthusiasm – because the colonization had to<br />

succeed – which also included the growing crowd of natives<br />

involved, who turned out to be very friendly and talented.<br />

The first temporary camp was traded for a big and beautiful<br />

white castle with many individual rooms (offices), lots of<br />

cupboard space (spare parts storage), large, modern reception<br />

facilities (test station) and a fine dining room (canteen). The<br />

Danes ate their flat, homemade rye bread lunches while the<br />

natives looked on in astonishment, munching on their big,<br />

soft, store-bought sandwiches with mayonnaise and pickles.<br />

Yes, it was a culture clash that certainly could cause the laughter<br />

to spread. As newcomers we tried to be very resourceful;<br />

communication took place via letters or telefaxes that were<br />

38 | 39<br />

difficult to understand, because phoning out of the country<br />

was very expensive back then. However, sometimes we were<br />

paid a visit by headquarters when the local merit badges were<br />

not adequate – and then we got supplies of herring and real<br />

rye bread. We learned about the natives’ institutions, like<br />

kindergartens and schools, where our children were very well<br />

treated – even though some of the teachers had serious doubts<br />

about the intelligence of our children, since they didn’t speak<br />

the local language very well.<br />

With wonderful memories and the belief that we’d gained a<br />

bit of insight into the way other people think, we headed home<br />

to Denmark. Here, there were still intense discussions about<br />

Christiania, the Great Belt Bridge and the weather, which sometimes<br />

require extra effort to stay on top of. Three years had<br />

gone by quickly, with all the good experiences and acquaintances<br />

that we were looking forward to telling people at home<br />

about, but which at the same time was complicated by the<br />

domestic Vietnam syndrome. Still, it was nice to return to<br />

our motherland, and it didn’t diminish our experience of a<br />

fantastic stay in a wonderful U.S. and the belief that the<br />

success of <strong>Niro</strong> Inc. was well on the way.

By Jens Thousig Møller<br />

A spray drying plant for Kaolin in the U.S.

Infant formula: a vital alternative<br />

One of <strong>Niro</strong>’s biggest markets is the delivery of drying plants<br />

for the production of infant formula. We have delivered plants<br />

to all of the world’s biggest infant formula manufacturers.<br />

Infant formula plant in the East.<br />

40 | 41

For those who have never tried it, it looks so easy – this<br />

thing with babies and nursing. In books and movies it’s<br />

often portrayed as though the woman just puts the baby to<br />

the breast, and then everything else happens naturally. But<br />

it’s not always that easy. The woman may lack milk, the<br />

child may be allergic to the breast milk, or a busy life can<br />

make it impossible for the mother always to be physically<br />

available to nurse her child.<br />

That’s why it’s always been necessary to find alternatives<br />

that could give infants vital nourishment if their mother was<br />

not able to produce milk herself or had died in childbirth.<br />

During the 19th century, scientists started experimenting<br />

with production of infant formula. Today, the production and<br />

marketing of infant formula is dominated by multinational<br />

companies such as Nestlé, Wyeth, Abbott and Nutricia. They<br />

all use <strong>Niro</strong> as their supplier of equipment to manufacture<br />

the finished powder.<br />

Manufacturing infant formula<br />

The raw material used is mixed in big tanks to get a composition<br />

of the final product that is as close to breast milk as<br />

possible. Based on regular milk, many different ingredients<br />

are added, such as vitamins, essential amino acids, special<br />

oils, extra sugar and different proteins, either in liquid or<br />

powder form.<br />

By Vagn Westergaard<br />

After mixing, the product is heat-treated to ensure a low<br />

content of bacteria before it is homogenized, evaporated<br />

and dried.<br />

To design and manufacture an entire process line, <strong>Niro</strong> works<br />

with many of our sister companies in <strong>GEA</strong>’s Processing Division.<br />

Our strength is that we listen to customers concerning<br />

how and in what order they want the different raw materials<br />

mixed. No two infant formulas are exactly the same. When<br />

it comes to evaporation and drying, customers listen to <strong>Niro</strong><br />

because our technology is world-leading. The most important<br />

thing for the baby is that it gets the right amount of nutrition,<br />

and that the formula is soluble in water without generating<br />

lumps in the bottom of the baby’s bottle or leaving small,<br />

undissolved particles that block up the holes in the nipple.<br />

As the amount of nutrition in the powder is stated in grams<br />

but often measured with a measuring cup, it is important<br />

that the density of the powder is adjustable in the drying<br />

process so that it is always the same.

Great emphasis on hygiene<br />

<strong>Niro</strong> places great emphasis on delivering plants with a high<br />

hygienic standard, which is vital for babies. Bacteria and<br />

contamination control is in focus, and the spray drying<br />

plants live up to stringent health and safety requirements.<br />

The density is primarily regulated by sending all the small<br />

particles formed during the drying process back through<br />

the process, so that they are pasted together with the larger<br />

particles in order to form an agglomerate. But since agglo -<br />

merates are the main cause of undissolved particles, <strong>Niro</strong><br />

has to master the agglomeration process. That <strong>Niro</strong> has<br />

done so is demonstrated by the fact that <strong>Niro</strong> has about 80<br />

percent of the world market for sales of plants for formula<br />

production.<br />

About infant formula<br />

• Infant formula makes up 45 percent of the market for<br />

food for babies.<br />

• The biggest markets for infant formula are India, China<br />

and the Far East.<br />

• It is expected that in 2010, Asia will make up half of the<br />

global market for infant formula.<br />

42 | 43<br />

Evaporator for milk.

Practical problem cracker By Vagn Westergaard and Thorvald Ullum<br />

The amazing tool Computational<br />

Fluid Dynamics (CFD) has saved<br />

time, money and headaches for both<br />

<strong>Niro</strong> and our customers.<br />

For a number of years, a customer in Asia had lived with a<br />

problem that seemed almost impossible to solve. They had<br />

bought a <strong>Niro</strong> spray drying plant for the manufacture of infant<br />

formula, but there was the problem that wet product stuck<br />

to the walls of the chamber. This meant the loss of a great<br />

deal of the product, a needless waste of time and an increased<br />

risk of fire in the chamber.<br />

The employees at <strong>Niro</strong> in charge of the plant discussed what<br />

could be done. One solution could be to carry out experiments<br />

on this plant to find a possible solution to the problem. This<br />

would have been incredibly expensive and time-consuming<br />

and very annoying for the customer. Instead they chose to<br />

use Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD). CFD gives the user<br />

the opportunity to test possible solutions faster and more<br />

inexpensively by means of a computer instead of real, physical<br />

tests. CFD simulations are carried out at <strong>Niro</strong> by CFD specialists,<br />

and the results are evaluated with process technologists<br />

who have extensive practical experience.<br />

With the help of CFD, the problem with the infant formula<br />

plant was solved with great success. A process technologist and<br />

a CFD specialist worked together closely on the remodeling of<br />

the plant, which translated into a financial gain for the customer<br />

of approximately DKK 3 million a year. In addition,<br />

solving the case has had great significance for the relationship<br />

between the customer and <strong>Niro</strong>.<br />

With CFD it is possible to study the flow of liquids and gasses.<br />

A mathematical model consisting of several million very complex<br />

equations is built, which describes the physical system<br />

one wants to study. When the model is complete and implemented,<br />

the computer is able to predict the movement of<br />

liquids and gasses, transport of heat and mass, loss of pressure,<br />

particle movement and drying.<br />

With CFD it is therefore possible to build a virtual model of<br />

a system and expose it to realistic physics and chemistry.<br />

The credibility of the model’s predictions is strongly dependent<br />

upon the input of the user as well as powerful computers<br />

for calculation, which is why <strong>Niro</strong> uses many resources on<br />

validating and developing the whole CFD environment.<br />

Among other things, <strong>Niro</strong> has developed an experimental<br />

method to determine the matter-specific drying velocities<br />

that are part of the CFD simulations of a spray drying chamber.<br />

Outside of <strong>Niro</strong>, CFD is used within many different areas such<br />

as meteorology, optimization of ship, airplane and car design,<br />

as well as within the whole chemical and process technology<br />

industry etc. Today, 3-4 <strong>Niro</strong> employees work with CFD full<br />

time. CFD is extensively used for problem-solving and design<br />

optimization in almost all of <strong>Niro</strong>’s components. The results<br />

are so reliable that <strong>Niro</strong> can design plants that are smaller<br />

and more efficient than before – a significant step in the effort<br />

to remain out front and competitive.

How <strong>Niro</strong> stacks up in the environment<br />

The Studstrup plant – one of two Danish<br />

power plants using <strong>Niro</strong> SDA technology.<br />

44 | 45

Flue gas cleaning is not a traditional business area for<br />

<strong>Niro</strong>, but being different doesn’t preclude success.<br />

A request from the Fiat factories in Torino for a plant that<br />

could remove sulphur compounds, SO2, from the flue gas<br />

emitted by a coal-fired power station in 1975 was the start of<br />

one of <strong>Niro</strong>’s most extraordinary adventures.<br />

New national and international requirements to reduce airborne<br />

pollution had resulted in power plants, among others,<br />

having to reduce their sulphur discharge. As a consequence<br />

of Fiat’s request, <strong>Niro</strong> looked into the possibility of using a<br />

traditional <strong>Niro</strong> spray dryer as a combined drying and absorption<br />

chamber. The idea was to use the hot flue gas in a<br />

spray dryer to dry a slurry of lime, which would also neutralize<br />

the acidic sulphur compounds in the flue gas. It worked<br />

and <strong>Niro</strong>’s Spray Drying Absorption (SDA) process was born.<br />

Since <strong>Niro</strong> saw significant market potential in flue gas<br />

cleaning, a large development project was started which,<br />

among other things, involved a pilot plant being placed at<br />

a power station in Fergus Falls in the U.S. <strong>Niro</strong> employees<br />

By Niels Jacobsen<br />

from all over the world staffed the pilot plant, which soon<br />

produced large amounts of data. At the same time, development<br />

work continued in Denmark, and the application was<br />

expanded to also include being able to clean flue gas from<br />

waste incineration plants. The big breakthrough came in<br />

1978, with the first commercial order of an SDA plant for an<br />

American power station, Antelope Valley.<br />

A flue gas cleaning plant of this magnitude meant that the<br />

spray dryers were much bigger than those <strong>Niro</strong> had ever<br />

built. Handling the large amount of flue gas required four<br />

Spray Drying Absorbers, plus one in reserve – each 14 meters<br />

in diameter. To ensure that this first plant became a success,<br />

the decision was made to build a pilot plant with a 14-meterlarge<br />

absorber in Minneapolis, Minnesota in the U.S. The<br />

plant was built as quickly as possible, and just before Christmas<br />

in 1980, flue gas was desulphurized for the first time<br />

with a full-scale industrial <strong>Niro</strong> SDA plant.

An adventure with a future<br />

After this the orders came in a steady flow from both<br />

Germany and the U.S., and <strong>Niro</strong> built large organizations in<br />

both the U.S. and Denmark to handle the extensive flue gas<br />

orders. In 1986 the business strategy in the area was changed<br />

drastically; instead of being the supplier of complete flue<br />

gas cleaning plants, <strong>Niro</strong> took one step back and entered<br />

into license agreements instead, so that other companies<br />

would now build <strong>Niro</strong> SDA plants. <strong>Niro</strong> maintained the role<br />

as technical, sales and marketing advisor. The flue gas group<br />

shrunk to a handful of employees, but the prospect of new<br />

markets in China, among others, resulted in more resources<br />

being provided, and the flue gas group successfully entered<br />

the Chinese, Korean and South American markets.<br />

The process and the plant components involved have been<br />

refined and the capacity increased over the years. Thus it is<br />

almost possible to obtain the same capacity as in Antelope<br />

Valley with one Spray Dryer Absorber with a diameter of<br />

over 20 meters, compared to the original 14 meters. The<br />

biggest atomizers are the F-1000, which can handle roughly<br />

120 tons of lime slurry per hour. Process improvements mean<br />

that today it is possible to clean the fluid gas almost 100%.<br />

Smoke and Muck, as the flue gas area has been called,<br />

can be compared to the ugly duckling in Hans Christian<br />

Andersen’s fairy tale. We don’t really fit into <strong>Niro</strong>’s normal<br />

business areas, nor do we run the business the same way –<br />

but when we look at our reflection on <strong>Niro</strong>’s bottom line,<br />

the view is pretty good.<br />

46 | 47<br />

A view from the top floor of a spray absorption plant (14 meters in diameter) in<br />

the Czech Republic. A reserve plant F 800 is ready for replacement, at the top<br />

right of the picture.

The power plant Antelope Valley in the U.S.,<br />

from where <strong>Niro</strong> got its first order for an SDA plant in 1978.

The coffee chronicle<br />

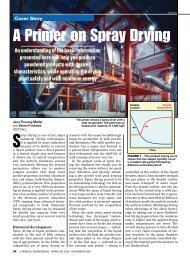

Around the world, more than a trillion cups of coffee are<br />

consumed every year. But how many people really know<br />

the story behind the popular drink?<br />

The word coffee gives many impressions and associations.<br />

A literature critic would probably think of Karen Blixen’s<br />

biographical novel Out of Africa, which has a coffee plantation<br />

as the setting for her tragic love story. A farmer would perhaps<br />

look at it as a very demanding and troublesome bush with a<br />

relatively expensive crop. And a <strong>Niro</strong> engineer would probably<br />

immediately think of big, rust-free production plants, in<br />

which one can turn green coffee beans into instant coffee.<br />

But what is coffee really? Coffee is a bush that originally<br />

grew in the highlands of the Horn of Africa and the Arabic<br />

peninsula. The coffee bush bears fruit (berries), each of<br />

which contains two stones or beans (normally called green<br />

beans). As the berries often are picked by very simple means,<br />

and the handling thereafter (where the flesh is removed from<br />

the green beans) often is very rough, the result is broken beans,<br />

which cannot be sold as grade A quality. These beans usually<br />

aren’t bad as far as taste goes, so instead of using the beans<br />

as fuel, there’s the possibility of using them and increasing<br />

their value by producing instant coffee. In this way, coffee<br />

farmers also get the full benefit of their crop.<br />

48 | 49<br />

Coffee during the war<br />

Instant coffee has been known since 1909, but it wasn’t until<br />

the 1940s, during World War II, that larger amounts of instant<br />

coffee were produced and supplied to the American and<br />

English troops. Instant coffee was manufactured with very<br />

doubtful profitability and quality (both taste and appearance<br />

could have been much better), but it served the purpose of<br />

soldiers being able to get coffee quickly, and it didn’t take a<br />

lot of effort to make coffee on the front line.<br />

The first real industrial spray drying plant for the production<br />

of instant coffee of reasonable quality was built in the years<br />

1950-1952. <strong>Niro</strong> was at the forefront and among the pioneers<br />

in Brazil. In 1947, <strong>Niro</strong> was able to offer and design industrial<br />

plants and matching pilot tests with extraction and spray<br />

drying for the first time. The first big boom in deliveries of<br />

extraction and spray drying plants came in the 1960s. In<br />

1965, the first freeze-drying plants also were delivered, and<br />

the former Atlas freeze-drying division (which today is a<br />

completely integrated part of <strong>Niro</strong>), was the frontrunner.

By Sten Warburg

<strong>Niro</strong> freeze drying plant Atlas, type RAY. FSD from the coffee factory HACO in Switzerland.<br />

<strong>Niro</strong> freeze drying plant Atlas, type CONRAD.<br />

50 | 51

How do you make instant coffee?<br />

But then how do you make instant coffee? Roughly speaking,<br />

the production of instant coffee starts the same way as at<br />

home in the kitchen. One grinds the roasted coffee beans<br />

and lets boiling water seep through them. Then the percolated<br />

water is dried out of the liquid coffee (the extract), and now<br />

one has instant coffee. Between the extraction step and the<br />

drying step another step can be inserted, where the aromatic<br />

content is optimized and the extract concentrated. The extraction,<br />

the evaporation and the drying of coffee in a <strong>Niro</strong><br />

plant is today executed in such a way that the quality is on<br />

the same level as freshly brewed coffee from newly roasted<br />

beans. Any differences in taste between instant coffee and<br />

fresh coffee are therefore today more a question of choice of<br />

beans and the desire for profit, which all comes down to the<br />

question of how much we want to pay for the product. Since<br />

1947, where the first small steps were taken towards extraction<br />

and spray drying of coffee, <strong>Niro</strong> has constantly sought to<br />

improve the spray drying process, and today <strong>Niro</strong> is the<br />

world’s leading supplier of equipment for instant coffee plants.<br />

Through purchases, working with knowledge databases and<br />

development, <strong>Niro</strong> today is able to offer complete turnkey<br />

coffee plants for freeze-dried, spray dried and agglomerated<br />

instant coffee – plants covering everything from reception<br />

of the green beans through the production of instant coffee,<br />

packed in glass and palletized, ready for shipment. Why have<br />

instant coffee at all today? Because it is easy and convenient<br />

to make a quick cup, it is easy to use in coffee machines<br />

(there are no coffee grounds to dispose of), the shelf-life is<br />

long, and it weighs and takes up very little space compared<br />

to coffee beans.<br />

Cool coffee facts<br />

• There are three main types of coffee: Arabica, Robusta<br />

and Liberica.<br />

• Arabica and Robusta make up about 98 percent of the<br />

coffee sold.<br />

• The total world production of coffee beans varies from<br />

year to year; it is between 6.5-7 million tons per year,<br />

which corresponds to more than one trillion cups of coffee.<br />

• Approximately 20 percent of the total coffee production<br />

is used to produce instant coffee.<br />

• <strong>Niro</strong> has delivered more than 180 coffee production<br />

plants all over the world.<br />

The top part of a coffee extractor.

Plastic is used everywhere<br />

<strong>Niro</strong> delivers drying plants for polymers, which are used<br />

in plastic toys, packaging and construction materials.<br />

CONTACT FLUIDIZER for drying of the polymer HDPE in Poland.<br />

52 | 53

NOZZLE TOWER spray dryer for production<br />

of the polymer Polyacrylonitrile in<br />

the Netherlands.<br />

By Henrik Bender Mortensen and Claus Lemb<br />

When the kids play with balls or LEGO ® blocks, <strong>Niro</strong> has<br />

probably been in the game. And when Dad plays handyman<br />

and uses electrical cables or puts up gutters, or Mom wipes<br />

down the deck chairs, <strong>Niro</strong> might also have been part of the<br />

process. LEGO ® blocks, electric cables, gutters and plastic<br />

garden furniture consist of polymers, which can have been<br />

dried in a <strong>Niro</strong> plant.<br />

There are many different polymers. Polymers are used in<br />

the fashion industry for shoes and belts, in kitchenware such<br />

as ladles and mixing bowls, as well as in packaging and white<br />

glue. Already in the early 1950s, <strong>Niro</strong> started selling spray<br />

drying plants to the part of the PVC business that produces<br />

soft toys and electrical cables, among other things. Good<br />

connections helped <strong>Niro</strong> get orders for a number of plants,<br />

and in the early 1960s <strong>Niro</strong> developed flash and fluid bed<br />

drying plants for a type of PVC used among other things for<br />

gutters and garden furniture.<br />

In the early 1970s the market changed, so that the type of<br />

PVC used in soft toys and cable insulation became by far<br />

the biggest part of the market. At that time <strong>Niro</strong> had sold a<br />

number of flash fluid bed plants and about 100 spray drying<br />

plants. The focus was switched, and since then <strong>Niro</strong> has sold<br />

roughly 200 flash and fluid bed plants and more than 100<br />

spray drying plants.<br />

The first PVC plant was able to produce four tons of product<br />

per hour, while the plants that <strong>Niro</strong> delivers today are able<br />

to produce more than 40 tons of product per hour. During<br />

the 1980s and ‘90s, the polymer market ran out of steam.<br />

But since 1998, <strong>Niro</strong> has sold more than 70 drying plants for<br />

the production of polymers, of which many large ones are<br />

sold especially to the Chinese market.

<strong>Niro</strong> strikes while the iron is hot<br />

<strong>Niro</strong> has created a unique position for itself as the leading supplier<br />

of spray drying plants for the production of hard metal powders.<br />

<strong>Niro</strong> has always had many irons in the fire – also when it<br />

comes to the spray drying of hard metals, which are used<br />

within the mining and tooling industries. When a smith<br />

stands at the lathe to work metal into tools, for example, he<br />

uses a cutting flat. The cutting flat is a tool that is used in a<br />

lathe to work on the metal object one wants to shape into<br />

another defined form. Hard metals are characterized by having<br />

great strength and hardness and are very suitable for making<br />

cutting flats for shaping metal and for mining equipment.<br />

Cutting flats and tools of hard metal are typically processed<br />

by pressing the hard metal powder into the desired object.<br />

The particle size of the hard metal powder being pressed<br />

greatly influences the physical qualities one can obtain. A<br />

fine hard metal powder typically has greater hardness and<br />

resistance against wear in the finished cutting flat. <strong>Niro</strong>’s<br />

spray drying plants have proven especially suitable for obtaining<br />

a well-defined particle size of the hard metal powder.<br />

A unique position in the hard metal market<br />

Today <strong>Niro</strong> has a unique position within the spray drying of<br />

hard metals, and during the last 40 years has delivered more<br />

than 120 spray drying plants for hard metals. The hard metal,<br />

cobalt and binding material are initially ground in a liquid<br />

for many hours until the right particle size is obtained.<br />

Then the mixture, called the hard metal feed, is dried in the<br />

spray drying plant. Hard metals are also used for the coating<br />

of metals, which thereby achieve greater mechanical strength.<br />

This means that the metal on a drill or saw, for example, can<br />

54 | 55<br />

be coated with a thin layer of hard metal, which gives it a<br />

very strong surface and thereby makes it more resistant to<br />

wear and tear.<br />

The use of hard metals is growing steadily. In 1930, the world’s<br />

total use of hard metals was 10 tons per year –1,000 tons a<br />

year at the beginning of the 1940s, and 10,000 tons a year at<br />

the beginning of the 1960s. Today approximately 50,000<br />

tons of hard metals are produced per year. Hard metals are<br />

so valuable that a very large part of the used cutting flats is<br />

collected by the hard metal companies and reused for the<br />

production of new cutting flats.<br />

About hard metal<br />

• Hard metals have different names, such as tungsten or<br />

wolfram, and the latter is not randomly named. Wolfram<br />

is Scottish and means wolf froth, which refers to the<br />

metal being so hard to dig out of the ground that back in<br />

the old days it simply “ate” the shovels, like a wolf consumes<br />

a sheep.<br />

• Wolfram was first isolated in 1781 by the Swedish<br />

pharmacist Carl Wilhelm Scheele.<br />

• In 1909 an American, W.D. Coolidge, succeeded in using<br />

metallic wolfram for filaments that could be used in<br />

incandescent lamps.<br />

• Wolfram can be found in several countries, while China<br />

has approximately 60 percent of the known wolfram<br />

reserves.

A <strong>Niro</strong> HC 600 plant for hard metals.<br />

By Allan Juel Pedersen<br />

A stainless steel object is being worked up on a lathe.<br />

Right beneath the white coolant is the cutting roll,<br />

utting into the steel.

Little brother standing on his own two feet<br />

<strong>Niro</strong>’s youngest division, the Pharma Division, became an<br />

independent part of <strong>GEA</strong> Pharma Systems on January 1, 2008.<br />

In 2007, <strong>GEA</strong> decided to create an independent Pharma Division<br />

(H-Division) within <strong>GEA</strong>. The division was established<br />

by transferring the former companies in <strong>Niro</strong> Pharma Systems<br />

from the P-Division in <strong>GEA</strong> into the newly established H-Division.<br />

With the establishment of the Pharma Division, it was<br />

natural to transfer <strong>Niro</strong>’s own Pharma Division.<br />

<strong>Niro</strong>’s Pharma Division is one of the newer <strong>Niro</strong> success stories.<br />

Not until the latter 1990s did pharmaceutical companies<br />

seriously start demanding spray drying plants for the drying<br />

of medicine. This new opportunity was clearly identified<br />

and led in 2000 to the establishment of a dedicated Pharma<br />

Division at <strong>Niro</strong>.<br />

During the last 10 years, the pharmaceutical industry has<br />

found it more and more difficult to find promising new drugs<br />

– the “easy” products have been found and are already on the<br />

market. In addition, the pressure on big pharmaceutical companies<br />

has been further increased, as patents on their main<br />

products expire and manufacturers of generic drugs are<br />

able to start production.<br />

The pharmaceutical industry spends vast amounts on research<br />

and development – typically between 10 and 30 percent of<br />

56 | 57<br />

their business. Unfortunately, the new drugs being discovered<br />

are predominantly very difficult to turn into commercial<br />