Lost River - Karst Information Portal

Lost River - Karst Information Portal

Lost River - Karst Information Portal

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

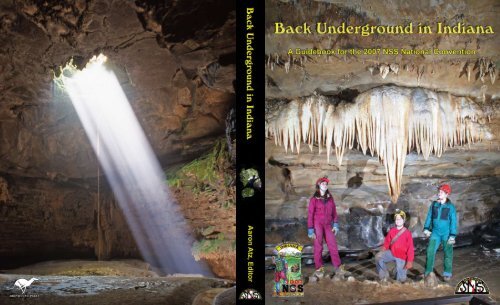

Back Underground in Indiana<br />

A Guidebook for the 2007 National Convention<br />

of the<br />

National Speleological Society<br />

Marengo, Indiana<br />

Aaron Atz, Editor<br />

Produced by the 2007 NSS Convention Committee<br />

Dave Haun, Chairman<br />

Layout and design by<br />

G. Thomas Rea<br />

National Speleological Society<br />

2813 Cave Avenue<br />

Huntsville, Alabama 35810-4431<br />

USA

Back Underground in Indiana<br />

Published by<br />

National Speleological Society<br />

2813 Cave Avenue<br />

Huntsville, Alabama 35810-4431<br />

256-852-1300<br />

http://www.caves.org/<br />

Front cover photograph: Meredith, Sean, and Karen Strunk at the Elephant Head in<br />

Marengo Cave, photo by Elliot Stahl (2007).<br />

Front cover inside: Postcard of Wyandotte Cave entrance, photo by Perry Griffith (1931).<br />

Back cover inside: “100 Foot Pit” photo by George Jackson, 1938.<br />

Back cover photograph: Sunbeams stream down into an unnamed cave, photo by<br />

Aaron Atz.<br />

On the spine: Looking out of the entrance to Maucks Cave, by Brian Killingbeck.<br />

© Copyright 2007 National Speleological Society<br />

All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in<br />

any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying,<br />

recording, or any data storage or retrieval system without the express written<br />

permission of the National Speleological Society, Inc.

Contents<br />

Welcome from the NSS President 3<br />

Welcome from the Convention Chairman 4<br />

Welcome from the Governor of Indiana 5<br />

Editor’s Notes 6<br />

Acknowledgements 7<br />

I The Harrison Crawford area and Southern Indiana 9<br />

Scenic Diversions (McDowell, Wilson, and Atz) 11<br />

About Indiana Caving (Tozer) 16<br />

A Short History of Early Crawford County (Eastridge) 17<br />

II Exploration 19<br />

The Saga of Easter Pit (Lemasters) 21<br />

The Discovery and Exploration of the <strong>Lost</strong> <strong>River</strong> Cave System (Deebel) 27<br />

Other Exploration in the <strong>Lost</strong> <strong>River</strong> Drainage Basin (Deebel) 39<br />

Two Bit Pit, Harrison County, Indiana (McNamara) 45<br />

An Exploratory Trip to Gory Hole (Greenwald) 57<br />

The Exploration of Harrison Spring (Strickland) 61<br />

III Geology and Cave Sciences 71<br />

The Geology of the Indiana <strong>Karst</strong> and the Geology Field Trip (Strunk) 73<br />

The Cave Fauna of Indiana (Lewis) 180<br />

The Geology of Wyandotte Cave (Frushour) 186<br />

Projected Passage Profiles for the Wyandotte Caves System (Powell) 195<br />

The History and Status of <strong>Karst</strong> Vertebrate Paleobiology in Indiana (Richards) 197<br />

<strong>Karst</strong> Hydrogeology of the Harrison Spring Area (Bassett) 212<br />

IV Indiana Cave Organizations 219<br />

The Indiana <strong>Karst</strong> Conservancy, Inc. (Vernier) 221<br />

The Indiana Cave Survey: Past, Present, and Future (Everton) 228<br />

Indiana Grottos: Past and Present (Torode) 234<br />

V History 235<br />

Lewis D. Lamon: Indiana’s Grand Ol’ Man of Caving (Benton) 237<br />

George F. Jackson, NSS 151 (Benton) 240<br />

The Barn (Paquette) 242<br />

Caves, Cave Rescue, and the National Cave Rescue Commission in Indiana (Mirza) 247<br />

A Not Uncommon Occurrence at Harrison Spring (Atz) 252<br />

A History of Indiana Caving (Benton) 253<br />

A Historical Narrative of Wyandotte Cave (George) 258<br />

VI Conservation 263<br />

The Richard Blenz Nature Conservancy: Home of Buckner Cave (Everton) 265<br />

Bats in Indiana Caves (Kennedy) 270<br />

A Conservation Message (Vernier) 276<br />

1

2007 NSS Convention Guidebook<br />

2<br />

VII Miscellaneous 279<br />

Indiana Showcaves 281<br />

VIII Cave Descriptions 291<br />

Cave Selection 293<br />

Crawford County 294<br />

Harrison County 331<br />

Lawrence County 384<br />

Monroe County 398<br />

Orange County 405<br />

Owen County 410<br />

Washington County 415<br />

IX Color Photography 429<br />

Index 447<br />

X Map Packet<br />

Wyandotte-Easter Cave<br />

Breathing Hole<br />

B-B Hole<br />

Sullivan Cave<br />

<strong>Lost</strong> <strong>River</strong> Cave<br />

Marengo Cave<br />

Blue Spring Caverns

Welcome from the NSS President<br />

Welcome to Marengo, Indiana, and the 2007 NSS National Convention. It is a pleasure to<br />

have everyone visit Indiana.<br />

A convention is a great opportunity to bring us together. The scientist, explorer, conservationist,<br />

and the recreational caver all are interested in caves. Take some time to visit the sessions, see the<br />

latest art, hear of the exciting exploration, or just enjoy a cave. Use the many social events to<br />

meet and talk with fellow cavers from across the country. And most important, spend some time<br />

underground breathing cave air.<br />

Bill Tozer, President<br />

National Speleological Society<br />

Charlie Rothrock in Wyandotte Cave in the Discovery of 1941 with candle<br />

in hand. Photo by George Jackson, NSS 151.<br />

From the John Benton photo collection.<br />

3

2007 NSS Convention Guidebook<br />

4<br />

Welcome from the Convention Chairman<br />

Welcome to the 2007 NSS National Convention!<br />

The 2007 NSS Convention Staff welcomes you to this convention. We hope you enjoy your<br />

stay in beautiful southern Indiana.<br />

Hopefully, by the time you read this, I will be the 27th person to welcome you to the convention<br />

and Indiana. We call that Hoosier Hospitality. If not, come see me 26 more times and I will<br />

welcome you personally.<br />

Crawford County and Harrison County are rich in history and caves, from the early explorers<br />

and scientists like William Henry Harrison (9th U.S. President), Squire Boone (Daniel’s brother),<br />

Cox, Blatchley, Collett, Owen, Addington, Mercer, Malott, Eigenmann, Cope, Hovey, and<br />

Mumford, to the more recent, like Ash, Quinlan, Art and Peg Palmer, Hobbs, Lewis, Pearson,<br />

George, and Richards. These are just a few fellow adventurers that you might have heard or read<br />

about with a connection to this area in Indiana.<br />

The Harrison Crawford area offers a vast contrast of caving sites to choose from. The caves<br />

vary from the famous commercial caves, Wyandotte, Marengo, and Squire Boone; to one of<br />

Indiana’s longest, Binkleys; to our most intense vertical caves, Two Bit Pit, Hanging Rock Drop,<br />

and Heisers Well. And, of course, don’t forget the “gold” that is buried in a cave and has never<br />

been found.<br />

Volunteers staff all NSS conventions. This year is no exception. We have been working hard<br />

for the past three years to put together what will surely be a convention to remember! We are<br />

trying to get back to some of the convention staples that might be fond memories for you. If you<br />

see a staff member, please thank them for volunteering and helping out the convention and the<br />

NSS.<br />

Landowner relations are very important in this part of the country. Please be courteous and<br />

keep low profiles while on private property. Practice minimum impact on the caves and the cave<br />

owners. Some of the caves you might have visited at a past convention or Cave Capers in this area<br />

may be closed or have special requirements. Please do not assume that you just park and go. Check<br />

out our Cave Kiosk at the campground for information about caving at this convention.<br />

Finally, please remember to cave safe and come back alive. NSS member John Benton recalls<br />

a tip Lewie Lamon gave him 30 years ago about caving, “… caves, yeah, I like to go in ’em … and I<br />

like to come out!”<br />

Welcome “Back Underground in Indiana!”<br />

Dave Haun, NSS 24672 RL FE<br />

2007 Convention Chairman

Welcome from the Governor of Indiana<br />

5

2007 NSS Convention Guidebook<br />

6<br />

Editor’s Notes<br />

About one year ago I took the job of editor for the 2007 National Convention Guidebook,<br />

with Tom Rea overseeing layout, graphic design, and publishing. It has been a very interesting<br />

year. After sending and receiving hundreds of e-mails, sorting and choosing from more than 2,000<br />

submitted cave photos, sorting or creating over 900 guidebook files, making scores and scores of<br />

phone calls, scanning several dozen historical items, and editing (and sometimes begging for)<br />

more than 20 original articles, the task is now complete.<br />

This guidebook has been a very ambitious undertaking, as it has done things no other NSS<br />

convention guidebook has done before. This guidebook is the first ever to offer a color photography<br />

section, something that was always too expensive to do. But with the generosity of Richard Blenz,<br />

the dream became a reality. This may also be the largest guidebook ever, but we went to great<br />

pains to strive for quality as much as quantity. With that said, we have strived for accuracy and I<br />

hope there are few errors.<br />

I am a photographer so naturally this guidebook is very photo-oriented. It is exciting to note<br />

that many of the photos shown in this guidebook record the original human exploration of the<br />

cave shown in the photo. This is the first time most of these photos have ever been published, and<br />

I am honored to be involved. I want to thank all of the photographers who submitted photos<br />

for publication, particularly David Black, who helped me extensively by allowing me access to his<br />

personal photography collection<br />

And lastly I’d like to thank my wife Janie and my son Christian. Without their support I<br />

wouldn’t have been able to attempt this endeavor.<br />

I hope you enjoy Crawford County and the 2007 NSS National Convention.<br />

Sincerely,<br />

Aaron Atz, Editor<br />

2007 NSS Convention Guidebook<br />

April 25, 2007

Color Photography Section<br />

We are much in debt to Richard Blenz for<br />

his generous donation, without which the color<br />

photography section wouldn’t have been possible.<br />

Layout and Graphic Design<br />

Tom Rea, and for giving so much of his<br />

time to the NSS.<br />

Lending of Historical Items<br />

John Benton lent George Jackson’s photo<br />

collection for scanning and also provided<br />

access to his numerous historical items. Gordon<br />

Smith lent his historical caving postcards to be<br />

scanned from his private collection. And thanks<br />

to Keith Dunlap for giving access to historic<br />

Bugs Armstrong and Don Martin slides.<br />

Scanning<br />

Special thanks to David Black and Bob<br />

Vandeventer for scanning slides for others.<br />

Photography<br />

The following submitted photographs for<br />

the guidebook: Keith Dunlap, Dave Strickland,<br />

Willie Hunt, Chris Schotter, Elliot Stahl,<br />

Todd Webb, Dave Black, Brian Killingbeck,<br />

Mark Deebel, Glenn Lemasters, Bill Baus, Bill<br />

Greenwald, Dave Everton, Andrew Peacock,<br />

Don Martin, Aaron Atz, Anmar Mirza, Tom<br />

Rea, Danny Dible, Ty Spatta, Kevin Strunk,<br />

Robert “Bugs” Armstrong, Bob Vandeventer,<br />

Hugh Couch, Richard Vernier, Julian Lewis,<br />

Jim Richards, Ron Richards, Sam Frushour,<br />

and Merlin Tuttle.<br />

Articles<br />

Thanks to the following who authored<br />

articles for the guidebook: Gordon Smith,<br />

Claudia Yundt, Jim Richards, Sam Frushour,<br />

Richard L. Powell, Ron Richards, Glenn<br />

Lemasters, Dave Everton, Julian Lewis, Kevin<br />

Strunk, Anmar Mirza, Greg McNamara,<br />

Bill Greenwald, Bill Tozer, Bill Torode, Bob<br />

Vandeventer, Dave Strickland, Mark Deebel,<br />

Richard Vernier, John Benton, Jim Kennedy,<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

Don Paquette, Dave Haun, John Bassett,<br />

Richard Eastridge, Angelo George, Aaron Atz,<br />

Dan McDowell, and Kent Wilson.<br />

Guidebook Production or Other<br />

Assistance<br />

Ron Adams: Landowner relations,<br />

production of the caves list.<br />

Dave Black: Providing numerous cave<br />

maps and descriptions, and sharing his vast<br />

knowledge.<br />

Dave Everton: Contacting landowners,<br />

helping assemble the caves list, providing maps,<br />

and writing several articles.<br />

Meredith Hall Johnson: Proofreading.<br />

Kate Siebert: Proofreading.<br />

Brian Killingbeck: Photography<br />

assistance.<br />

Other Assistance and Encouragement:<br />

Patti Cummings, Dave Everton, Bill<br />

Greenwald, Dave Haun, Tom Rea, and Bob<br />

Vandeventer<br />

Section Divider Page Photos<br />

Section I: David Stahl at Wyandotte Woods<br />

overlook, photo by Elliot Stahl.<br />

Section II: Mapping trip in Bluespring<br />

Caverns, 1965, photo by Art Davis.<br />

Section III: Sam Frushour and Kevin<br />

Komisarcik conducting the level tube survey of<br />

Wyandotte Cave, photo by Aaron Atz.<br />

Section IV: Members of the Harrison<br />

Crawford Grotto during a clean-up trip to<br />

Langdons Cave, photo by Aaron Atz.<br />

Section V: Large group at entrance of<br />

Wyandotte Cave, 1906, from the Gordon<br />

Smith photo collection (photographer<br />

unknown).<br />

Section VI: Cave Pearls in Bear Plunge,<br />

photo by Elliot Stahl<br />

7

2007 NSS Convention Guidebook<br />

Section VII: The Marengo Cave Band,<br />

from the Gordon Smith photo collection<br />

(photographer unknown)<br />

Section VIII: Three cavers on the Old Cave<br />

Route of Wyandotte Cave, photo by George<br />

8<br />

Jackson, 1935. From the John Benton photo<br />

collection.<br />

Section IX: Bob Braybender in Wyandotte,<br />

photo by George Jackson, 1935. From the John<br />

Benton photo collection.<br />

The entrance to Wyandotte Cave in 1923. Photo by George Jackson, NSS 151<br />

From the John Benton photo collection..<br />

Bob Braybender packing his caving and photography gear behind his Studebaker<br />

outside Wyandotte Lodge in 1939. Photo by George Jackson.<br />

From the John Benton photo collection.

Section I: The Harrison Crawford Area<br />

and Southern Indiana

2007 NSS Convention Guidebook<br />

10

The Convention Planning staff is pleased<br />

to have the opportunity to offer a wide<br />

variety of scenic and recreational attractions<br />

to the attendees of the 2007 NSS National<br />

Convention. Quite a few of these attractions<br />

can be visited or seen in conjunction with trips<br />

to visit caves featured in this guidebook. Or<br />

Crawford County offers a lot of fine scenery<br />

and many of the roads have overlooks.<br />

There are quite a few attractions to be seen in<br />

Crawford County.<br />

The Harrison Crawford State Forest is a<br />

25,000+ acre property located on the edge of<br />

Crawford and Harrison counties that contains<br />

hundreds of Indiana’s finer caves. Access is from<br />

State Road 62 and State Road 462. The latter<br />

road leads to the entrance of O’Bannon Woods<br />

State Park, a 2,400-acre park in the middle<br />

of the Harrison Crawford State Forest. There<br />

are three campgrounds in the complex ranging<br />

from primitive and horse camping to a 281-site<br />

campground that accommodates RV camping.<br />

This complex is bounded by the Ohio and<br />

Blue rivers as well as Indian Creek and offers<br />

the 24-mile Adventure Hiking Trail as well as<br />

numerous day trails. There are also over 100<br />

miles of horse trails. A brand-new, Olympicsize<br />

swimming pool should be finished in time<br />

for the convention. The “main” areas of the<br />

Harrison Crawford State Forest are located<br />

only 15 to 20 minutes from the convention<br />

site.<br />

Wyandotte Caves are located 20 minutes<br />

from the convention site. They are owned by<br />

the state of Indiana and managed by Marengo<br />

Cave. Wyandotte is famous for being a show<br />

cave since the 1850s and has very large rooms<br />

and passages on its 1½-hour tour. It is well worth<br />

a visit. Little Wyandotte Cave has a beautifully<br />

decorated 30-minute tour. Cave tours will be<br />

Scenic Diversions<br />

By Dan McDowell, updated by Aaron Atz and Kent Wilson<br />

Crawford County<br />

perhaps you may want to set aside a day or two<br />

for some specific trips or activities. We invite<br />

you to take a few minutes to check out the large<br />

variety of leisure activities available to you in<br />

southern Indiana. The information included in<br />

the registration packets will list many of these<br />

public attractions.<br />

half-price with your convention ID badge.<br />

Marengo Cave Park is just off State Road<br />

64 in Marengo in Crawford County, just<br />

4 miles north of the convention site. Two<br />

different tours are offered: the Crystal Palace<br />

and the Dripstone Trail. You must be at the<br />

cave by 2:00 p.m. to make both tours. Marengo<br />

Cave also offers a snack bar, a gift shop, and a<br />

nature trail. Cave tours will be half-price with<br />

your convention ID badge.<br />

Cave Country Canoes is a canoe livery<br />

service in Milltown, on the beautiful Blue <strong>River</strong>,<br />

4 miles east of Marengo. Canoeing on the Blue<br />

<strong>River</strong> is a very popular pastime. A number of<br />

caves can be seen in conjunction with certain<br />

canoe trips.<br />

The Blue <strong>River</strong> Café is located in Milltown<br />

just a stone’s throw from Cave Country Canoes.<br />

Gourmet food and impressive drink lists go<br />

nicely with their live music on weekends.<br />

Stephenson’s General Store is located<br />

in Leavenworth, about 9 miles south of the<br />

convention site. In addition to groceries and<br />

traditional country-style food items, the store<br />

sells and displays many unique antiques. Don’t<br />

forget to visit the basement.<br />

Hemlock Cliffs, 3 miles south of Mifflin,<br />

is a part of the Hoosier National Forest. High<br />

sandstone cliffs and numerous shelter caves<br />

are prominent features of this scenic area.<br />

Hemlock Caverns is a large sandstone shelter<br />

that was an early American Indian occupation<br />

site. The floor of the valley has a noteworthy<br />

11

2007 NSS Convention Guidebook<br />

floral growth of ferns and wildflowers. There<br />

are hiking trails among the cliffs. The cliffs are<br />

about a 30-minute drive from the convention<br />

site. There is a specific and dedicated State<br />

Nature Preserve with a 1-mile loop trail. To<br />

protect the endangered plants and sensitive<br />

resources, rappelling is not allowed. However,<br />

at the nearby Messemore Cliff area, it is<br />

permitted.<br />

Patoka Reservoir is located at the junction<br />

of Orange, Crawford, and DuBois counties.<br />

This lake is 25,000 acres. Seven different<br />

state recreational areas offer a wide variety of<br />

activities including numerous boat launch<br />

ramps, a swimming beach, fishing, boating,<br />

water skiing, campgrounds, hiking, fitness<br />

trails, and bicycle trails. The lake is about 30<br />

minutes west of the convention site.<br />

Salt Shake Rock is found on State Road 37<br />

at the bridge over Little Blue <strong>River</strong>, 10 miles<br />

south of English. As you cross the bridge, you<br />

will see a pull off at a small shelter cave on the<br />

right. Salt Shake Rock, an isolated sandstone<br />

tower, is about 300 feet up the hill. Salt Shake<br />

Holiday World Theme Park and Splashin’<br />

Safari is located about 80 minutes west<br />

of the convention site and is well worth a visit<br />

if you have a spare day. Holiday World has<br />

been family operated since the 1950s and in<br />

the past 20 years has reinvested and reinvented<br />

itself to become truly one of the world’s best<br />

theme park values. They showcase some of the<br />

biggest and most impressive roller coasters in<br />

the Midwest and have recently added a large<br />

wave pool and full-sized water park. Don’t<br />

think because of its location that it is lacking.<br />

Add to this the $33.95 entry fee (check the<br />

Harrison County is the cradle of Indiana’s<br />

post-Revolutionary War history. Historic<br />

Corydon, the county seat, was also the site of<br />

Indiana’s second territorial capital and the first<br />

state capital as well. These early state buildings<br />

12<br />

Spencer County<br />

Harrison County<br />

Rock Cave is less than 100 feet to the right on<br />

the bank of Little Blue <strong>River</strong>.<br />

The Shoe Tree is at the four-way stop in<br />

Devils Hollow south of Milltown. It can be<br />

reached by following Wyandotte Cave Road 3<br />

miles north from Wyandotte Cave, making a<br />

left at the “T,” and going west to the four-way<br />

intersection. If you trash your caving boots<br />

during convention, do what all Hoosier cavers<br />

(and the local populace) do: lace them hush<br />

puppies together and fling them into Indiana’s<br />

famous Shoe Tree.<br />

Rothrocks Mill (technically in Harrison<br />

County) was the site of a 19th-century grist<br />

mill on Blue <strong>River</strong> that was owned by the same<br />

family that owned Wyandotte Cave. Now only<br />

the remnants of the dam and foundation of the<br />

mill remain, and the site is used for recreational<br />

purposes only. Regardless, it is a beautiful spot<br />

on Blue <strong>River</strong> and is close to the convention<br />

site. From the Shoe Tree go east for about 1.5<br />

miles, drop into the Blue <strong>River</strong> valley, and the<br />

site is on the right a quarter of a mile past the<br />

bridge over Blue <strong>River</strong>.<br />

Web site for discounts) and unlimited free<br />

soft drinks and water and you have a great<br />

value. From the convention site take I-64<br />

west to exit 63 and then go 7.3 miles south<br />

on Indiana 162 to the park. This is only 45<br />

miles from the convention site, most of it<br />

interstate.<br />

Holiday World & Splashin’ Safari has been<br />

voted the World’s Friendliest Park and the<br />

World’s Cleanest Park for five years in a row by<br />

the readers of Amusement Today magazine.http://www.holidayworld.com.<br />

have been restored and are designated The<br />

Corydon Capital State Historic Site.<br />

<strong>Information</strong> on this and other notable historical<br />

homes and sites can be obtained at the Visitors<br />

Center at 202 East Walnut Street in Corydon.

The Harrison County Visitors’ Center is about<br />

25 minutes from the convention site.<br />

The Harrison Crawford State Forest,<br />

see the complete listing under “Crawford<br />

County”<br />

Squire Boone Caverns and Village is just<br />

off State Road 135, 12 miles south of Corydon<br />

and 30 miles from the convention site. Formerly<br />

known as Boones Mill Cave, this cave is noted<br />

for its cascading waterfalls and impressively<br />

large rimstone formations. There is a restored<br />

pioneer village with a number of early craft<br />

shops, souvenir and snack shops, nature trails,<br />

picnic grounds, and a campground. Half price<br />

admissions for cave tours, pioneer village, and<br />

hayrides are available with convention ID<br />

badges.<br />

The Battle of Corydon Memorial Park<br />

on the south side of town honors the only<br />

Civil War battle fought in Indiana. On<br />

July 9, 1863, 450 local militia and citizens<br />

were overwhelmed by 2,000 Confederates<br />

of Brigadier General John Hunt Morgan’s<br />

Calvary. A monument, a small museum, and<br />

a short trail are on this 5-acre site.<br />

Caesars Indiana Casino boasts the<br />

country’s largest gambling vessel and features<br />

Italian gourmet-style dining at Portico. There<br />

is also an impressive buffet, multi-story hotel,<br />

and professional-grade golf course. It is located<br />

<strong>Lost</strong> <strong>River</strong>, in north-central Orange County,<br />

is the classic example of sinkhole plains and<br />

related karst features. If you do not have the<br />

opportunity to participate in the geology field<br />

trip, consider seeing some of the highlights on<br />

your own. By following the lost river portion<br />

of the geology field trip road log you can visit<br />

some of the interesting highlights of this area.<br />

Two places along the <strong>Lost</strong> <strong>River</strong> dry bed,<br />

Wesley Chapel Gulf and the Orangeville Rise,<br />

are National Natural Landmarks and are easily<br />

accessed. <strong>Lost</strong> <strong>River</strong> is about 45 minutes north<br />

of Marengo.<br />

West Baden Springs and French Lick,<br />

located about an hour northwest of Marengo,<br />

Orange County<br />

Scenic Diversions<br />

about 45 miles southeast of the convention<br />

site, just 10 minutes south of New Albany.<br />

Hayswood Nature Preserve is located 1<br />

mile south of Corydon on the east side of State<br />

Road 135. This 160-acre park is highlighted<br />

by Pilot Knob, a prominent local landmark<br />

that overlooks Indian Creek. Besides picnic<br />

grounds and hiking trails, an 8-acre lake<br />

features fishing, rowboats, and canoe rentals.<br />

This park has a special blacktop trail for the<br />

handicapped.<br />

The Zimmerman Glass Factory is located<br />

on the east side of Corydon. Drop in and watch<br />

them make hand-blown glass paperweights and<br />

souvenirs right before your eyes.<br />

The Constitution Elm historic site<br />

commemorates the writing of Indiana’s<br />

constitution in 1816 under a stately elm tree.<br />

The monument displays the remaining trunk<br />

of the tree and a plaque detailing the event. The<br />

site is located on High Street one block north<br />

of the square in Corydon.<br />

Stage Stop Campground is located 3 miles<br />

east of Wyandotte Cave on State Road 62 and<br />

offers excellent fishing, primitive camping, and<br />

swimming on the Blue <strong>River</strong>. This large site is<br />

operated by the Indiana Department of Natural<br />

Resources as part of the Harrison Crawford<br />

State Forest.<br />

are historical resort communities with a<br />

number of attractions. The West Baden<br />

Springs Hotel is considered to be a remarkable<br />

architectural achievement. Built in 1901, the<br />

200-foot-diameter dome was the world’s largest<br />

unsupported dome until the advent of the New<br />

Orleans Superdome, built in the 1970s.<br />

French Lick Casino Resort is Indiana’s<br />

newest casino.<br />

The Indiana Railway Museum is on State<br />

Road 56 just west of the railroad crossing as<br />

you enter French Lick. The old Monon Railway<br />

station houses, preserves, and operates historic<br />

railway equipment. The French Lick, West<br />

Baden, and Southern Railway offers 18-mile<br />

13

2007 NSS Convention Guidebook<br />

trips on weekends behind an old steam engine.<br />

The trip goes through the state’s second longest<br />

tunnel, the 2,217-foot French Lick Tunnel,<br />

built in 1906. The Railway Museum also<br />

operates an electric trolley running between<br />

the resort hotels.<br />

The French Lick Springs Hotel, Golf,<br />

and Tennis Resort. Golf or tennis, anyone?<br />

Aside from its historical fame as a resort for<br />

Spring Mill State Park is in Lawrence<br />

County on State Road 60, 20 miles west<br />

of Salem and 3 miles east of Mitchell. Spring<br />

Mill is one of Indiana’s most popular parks.<br />

Highlights are a reconstructed pioneer village<br />

and water-powered grist mill showing rural<br />

southern Indiana life in the 1800s. The Virgil<br />

I. Grissom Memorial honors “Gus” Grissom,<br />

one of the original seven astronauts. America’s<br />

second man in space was from nearby Mitchell.<br />

Spring Mill is also noted for its caves and<br />

impressive karst features. Donaldson Woods<br />

Nature Preserve is a 67-acre virgin forest.<br />

Activities include camping, hiking, picnicking,<br />

Falls of the Ohio State Park is in Clarksville<br />

on the Ohio <strong>River</strong>, 40 miles east of the<br />

convention site. The largest exposed Devonian<br />

fossil beds in the world are here. Activities are<br />

fishing, hiking, picnicking, sightseeing, and<br />

fossil viewing. No fossil collecting is allowed!<br />

The site’s modern interpretive center displays<br />

many millennia of geological and human<br />

history and is well worth a visit.<br />

Deam Lake State Recreational Area<br />

borders the south edge of Clark State Forest,<br />

25 miles southeast of Salem on State Road 60.<br />

The 1,300-acre property has an excellent 194-<br />

Cave <strong>River</strong> Valley is 3 miles north of<br />

Campbellsburg and 8 miles west of Salem<br />

on State Road 60 in Washington County (see<br />

14<br />

Lawrence County<br />

Clark and Floyd Counties<br />

Washington County<br />

the socially elite, there are two 18-hole golf<br />

courses, 12 indoor tennis courts, and a really<br />

large, glass-domed, all-weather pool on this<br />

2,600-acre resort.<br />

Tucker Lake is in Springs Valley, a USDA<br />

Forest Service recreational area 12 miles south<br />

and east of French Lick, 4 miles off State Road<br />

145. This is a small, pleasant lake park that offers<br />

camping, hiking, picnicking, and fishing.<br />

swimming, boating, fishing, saddle horse<br />

riding, cave tours (both walking and by boat),<br />

and a nature center.<br />

Bluespring Caverns Park is off State Road<br />

50 on County Road 450S. Bluespring is about<br />

50 miles north of the convention site and is 4<br />

miles southwest of Bedford. With more than<br />

20 miles of passages, Bluespring is Indiana’s<br />

second longest cave. The commercial section<br />

offers an impressive hour-long custom boat<br />

tour on Myst’ry <strong>River</strong> featuring on-board<br />

electric lighting. A special half-price tour rate<br />

is available to NSS members during the 2007<br />

NSS National Convention.<br />

acre fishing lake plus a number of other services.<br />

There is a nature center, camping, hiking, and<br />

picnicking, as well as a boat launch ramp,<br />

rowboat rentals, and a swimming beach.<br />

The historic Ohio <strong>River</strong> towns of New<br />

Albany and Jeffersonville are located near I-64<br />

and display a history unique to the riverboat<br />

culture of the 1800s and early 1900s. The<br />

Howard Steamboat Museum in Jeffersonville<br />

as well as The Culbertson Mansion in New<br />

Albany are two very well restored mansion<br />

museums from this era.<br />

page 415). Cave <strong>River</strong> Valley is a privately<br />

owned picnic park with several wild caves, two<br />

of them extensive. They charge $5.00 per person

per day, which includes the right to go into<br />

any of these undeveloped caves. Please check<br />

with registration to get additional information<br />

during the convention. Cave <strong>River</strong> Valley is<br />

about an hour’s drive from the convention site.<br />

The Knobstone Trail, Indiana’s longest trail,<br />

extends across Clark and Jackson-Washington<br />

State Forests. The trail is 58 miles long and is a<br />

The Birdseye Multi-use Trail is located<br />

immediately off State Road 64, about 20<br />

miles west of Marengo. It is 11.8 miles long and<br />

fees apply for mountain biking and horseback<br />

riding. Low impact hiking is free.<br />

Ferdinand State Forest has 7,657 acres. Of<br />

the five hiking trails, the 2.6-mile-long Kyana<br />

Trail is the longest. There are 8.8 miles of<br />

Twin, Tipsaw, and Saddle Lake recreation<br />

areas: From the convention site take I-<br />

64 west to the St. Croix exit and go south on<br />

State Road 37 to excellent National Forest<br />

properties, the Twin Lakes, Tipsaw Lake, and<br />

Saddle Lake areas. Excellent mountain biking,<br />

camping, hiking, hunting, fishing, and canoeing<br />

are the highlights at these two areas. There are<br />

Within the city limits of Evansville, Indiana,<br />

find prehistoric Angel Mounds, the<br />

largest in the state; Wesselman Woods Nature<br />

Preserve; Mesker Park Zoo and Gardens; and<br />

Louisville is located 40 minutes east of the<br />

convention site at the junction of Interstates<br />

64, 65, and 71. Take the 9th Street exit off I-<br />

64 to get to the downtown area, which offers<br />

the following points of interest: The Louisville<br />

Slugger Bat Factory and Museum is well worth<br />

a visit for baseball fans. The Muhammad Ali<br />

Dubois County<br />

Perry County<br />

Evansville, Indiana<br />

Louisville, Kentucky<br />

Scenic Diversions<br />

back country trail that follows the Knobstone<br />

Escarpment, a prominent geologic feature.<br />

The trail is ideal for backpack trips but can be<br />

accessed at several points for shorter day trips.<br />

Many sections of the trail are rugged. The closest<br />

trail head is at the eastern end of Delaney Park,<br />

10 miles north of Salem.<br />

mountain-biking trails. Primitive camping only,<br />

fees apply. In existence since 1934 and built<br />

by the Civilian Conservation Corps, hunting,<br />

fishing, boating, canoeing, and picnicking can<br />

also be enjoyed here. It is located less than 5<br />

miles north of I-64 at the Dale exit, about 45<br />

minutes from the convention site.<br />

15.7 miles in the Twin Lakes loops and 5.9<br />

miles around Tipsaw Lake. If you would visit<br />

the Twin Lakes site, you might be amazed to<br />

discover a monstrous stone building known as<br />

the Rickenbaugh House. Constructed in 1875<br />

from locally quarried sandstone and virgin<br />

walnut, chestnut, and oak, the building is listed<br />

on the National Register of Historic Places.<br />

“LST 325,” a fully restored World War II Navy<br />

ship and on-water museum. Evansville is about<br />

a 100-minute drive from the convention site.<br />

Center is a recent addition to the Louisville<br />

skyline for boxing fans. Fourth Street Live is<br />

a collection of new bars and restaurants and<br />

offers frequent outside live music. Six Flags<br />

Kentucky Kingdom is located south near the<br />

airport.<br />

15

Welcome to Indiana caving. Our caves<br />

are located on private, federal, and state<br />

lands. Each of these caves probably has specific<br />

rules, requests, or procedures to follow when<br />

you visit them. Please keep this in mind. But<br />

above all, treat the landowners or property<br />

managers you encounter with respect. The trip<br />

leaders for the led cave trips have permission<br />

from the owners and will know the special<br />

procedures.<br />

Unless otherwise advised by the convention<br />

staff, cavers should ask permission to visit any<br />

cave. The convention staff at the campground<br />

will have the latest information on access to the<br />

caves.<br />

Cave owners usually give permission to<br />

people who respect them and their property.<br />

Of course they must make up their mind<br />

quickly based upon first impressions. They<br />

want to know that you will respect their<br />

property including the cave and will do all of<br />

this safely. Their judgment is based upon what<br />

they see. Dressing in nice clean clothing, being<br />

polite, and showing respect are a must. And the<br />

people in the car are held to the same standards.<br />

Needless to say, alcohol has no place at the cave<br />

or on the cave property.<br />

The state lands require a permit, which<br />

16<br />

About Indiana Caving<br />

By Bill Tozer<br />

must be filed with the state. This is an easy<br />

thing to do and keeps the caves open to cavers.<br />

The permits require the usual information<br />

regarding the cavers and the cave they intend<br />

to visit. Permits may be obtained at the caving<br />

kiosk at the campground or at the main office<br />

at the entrance to O’Bannon Woods State Park.<br />

Completed permits should be deposited at the<br />

same location.<br />

The Hoosier National Forest is federally<br />

administrated and no written permission is<br />

required.<br />

The Indiana <strong>Karst</strong> Conservancy owns and<br />

manages several caves. Most of these caves<br />

will be available for trips. The Indiana <strong>Karst</strong><br />

Conservancy requires a liability release and a<br />

statement acknowledging the dangers of caving<br />

and the importance of conserving the cave.<br />

Complete and turn these in at the campground<br />

before leaving the convention site. And when<br />

in doubt, always check at the campground at<br />

the convention site for clarification.<br />

There are plenty of caves to visit, from<br />

easy walking caves to pits to wet, miserable<br />

crawlways. So feel free to enjoy our caves,<br />

but remember to treat the private and public<br />

stewards of our caves with respect so we may all<br />

continue to visit them for years to come.<br />

Wyandotte Cave, inner end of the Air Torrent: George Jackson, Dick Hughes,<br />

Bob Braybender. Photo by George Jackson about 1935.<br />

From the John Benton photo collection.

A Short History of Early Crawford County<br />

Leavenworth, on the Ohio <strong>River</strong>, was<br />

established in 1814 and became a major<br />

shipping port. Most of the county depended<br />

on the merchants at Leavenworth for essential<br />

goods from the outside world. Shortly thereafter,<br />

Indiana achieved statehood in 1816.<br />

In January of 1818, Martin Tucker presented<br />

a bill to the General Assembly at Corydon to<br />

admit Crawford County. The name Crawford<br />

was selected based on the reputation of William<br />

H. Crawford, a friend of George Washington.<br />

The bill passed and was signed by the governor<br />

on the 29th of January. The act was to take<br />

effect on March 1, 1818. Crawford County<br />

was formed from parts of Harrison, Orange,<br />

and Perry counties.<br />

Some of Crawford County’s early settlers<br />

were John Peckinpaugh, Elias Tadlock, Martin<br />

From the Aaron Atz collection.<br />

By Richard Eastridge<br />

Crawford County Historian<br />

Tucker, Thomas Stroud, John Ruth, Henry<br />

Hollowell, Nenion Haskins, Issac Kellems, Gory<br />

Jones, the Wiseman family, Issac Eastridge, and<br />

many more.<br />

Seth and Zebulon Leavenworth built a<br />

dam and mill across the Blue <strong>River</strong> at Milltown<br />

in 1821, which contributed greatly to the<br />

development of that part of the county. The<br />

mill was heavily damaged by flooding and was<br />

razed in 1959.<br />

It was decided that Mt. Sterling would<br />

be the county seat. A courthouse was built<br />

along with a jail and lots were sold with the<br />

proceeds to go to the county library. Because<br />

of a shortage of water in the county, the county<br />

seat was moved to Fredonia in 1822. Allan<br />

Thom constructed a two-story brick building<br />

that he gave to the county along with 50 acres<br />

17

2007 NSS Convention Guidebook<br />

of land. The courthouse remained in Fredonia<br />

until 1843 when it was moved to Leavenworth.<br />

The courthouse remained at Leavenworth until<br />

1896 when it was moved to English.<br />

Marengo was established in 1835 after<br />

being called Big Springs, Tuckerville, and<br />

Proctorville. Marengo did not grow to any<br />

degree until after the completion of the Air<br />

Line Railroad.<br />

Hartford was started in 1838 and did not<br />

prosper until the Air Line Railroad was built<br />

18<br />

From the Richard Estridge collection.<br />

in 1882. The name Hartford was changed to<br />

English after W.H. English of Indianapolis.<br />

The railroad had a great impact on Crawford<br />

County’s industry. Soon Eckerty and Taswell<br />

had over 20 timbering firms. Merchants could<br />

order their supplies and have them delivered<br />

to the depot, whereas previous shipping went<br />

long distances by horse or wagon. The railroad<br />

changed life greatly for those in Crawford<br />

County and pushed them even closer to the<br />

Twentieth Century.

Section II: Exploration<br />

1

2007 NSS Convention Guidebook<br />

20

Deep below the hills of Crawford County,<br />

Indiana, lies Wyandotte Cave. For<br />

centuries it has intrigued explorers with its<br />

depth and beauty. It once was used as a valuable<br />

mineral source by American Indians and early<br />

pioneers. Parts of Wyandotte Cave have long<br />

been a commercial attraction, sporting guided<br />

tours for visitors from around the world.<br />

Those tours continue to this day, provided by<br />

Wyandotte Caves LLC, under contract from<br />

the Indiana Department of Natural Resources,<br />

which manages Wyandotte Caves. The cave<br />

also serves as a hibernaculum to the endangered<br />

Indiana bat, keeping it closed during the<br />

winter months. Numerous stories and books<br />

The Saga of Easter Pit<br />

(The Connection to Wyandotte Cave)<br />

Easter Pit Cave entrance.<br />

Story and Photos by Glenn E. Lemasters<br />

exist about the cave. Since the recording of<br />

history began, names like Bentley, Jones,<br />

Curry, Rothrock, Sears, Jackson, Louden, and<br />

Siebert ring with stories of exploration within.<br />

But this story is about the 1987 connection of<br />

Wyandotte Cave to Easter Pit, a cave that lay<br />

nearly a mile from Wyandotte’s entrance.<br />

Easter Pit Cave was discovered by a longtime<br />

local caver named Leo Schotter. In 1967,<br />

Leo showed the entrance to Ted Wilson.<br />

The entrance, a 38-foot pit, led to a passage<br />

extending for a few hundred feet. Below this<br />

passage, in an obscure lower level, they found<br />

another passage containing many tight canyons,<br />

pits, and crawlways. Over the next few years,<br />

Ted and others explored and mapped what<br />

they thought was the extent of the cave.<br />

About 17 years later, on October 26, 1986,<br />

Ted revisited Easter Pit with me and Danny<br />

Dible. Our goal was to re-check the lower-level<br />

passage. It required negotiating tight canyons,<br />

pits, and crawls that led to a lower level where<br />

we came to a small slot in the floor. It appeared<br />

to drop into a larger passage below and seemed<br />

impassable without enlarging it a bit. A strong<br />

air current billowing from the crack beckoned<br />

us to return. The three of us, with the addition<br />

of fellow caver Joe Oliphant, did return. After<br />

a small amount of enlarging the slot, and with<br />

the aid of a rope, Wilson made the initial drop<br />

through to the floor that lay 5 feet below.<br />

It was the beginning of many return<br />

exploration and survey trips to the cave. Below<br />

the slot was a short passage that led to the top<br />

of a big room. A steep slope of breakdown<br />

boulders led down to a large borehole below,<br />

where a void of blackness beckoned us on. It<br />

was a large trunk passage, reminiscent of those<br />

in Wyandotte Cave. With no survey gear in<br />

hand, we elected to explore.<br />

It continued as a flat-floored, sandy walkway<br />

21

2007 NSS Convention Guidebook<br />

intermittently broken<br />

by rooms strewn<br />

with breakdown.<br />

Selenite crystals hid<br />

indiscriminately in<br />

places where their<br />

alabaster beauty had<br />

never been seen by<br />

the eyes of mankind.<br />

A few bats hid in<br />

crevices and clung<br />

to the ceiling. There<br />

was no evidence of<br />

any previous visitors<br />

in this passage. It was<br />

virgin cave!<br />

At one point in<br />

this corridor an upper<br />

level side passage led from a high ledge we called<br />

the Overlook. The passage leading from it was<br />

later explored, surveyed, and christened the<br />

Bowling Alley. This name came from the many<br />

exposed areas of Wyandotte chert embedded<br />

within the limestone walls. The Bowling Alley<br />

became too low to negotiate after nearly 1,500<br />

feet.<br />

Continuing inward in the main corridor<br />

and just past the Overlook, an intersection<br />

with a trunk of similar size occurred. This<br />

large passage, named after the late Tom Fritsch,<br />

22<br />

The Overlook.<br />

Indiana Avenue.<br />

ended within a few hundred feet in sediment<br />

fill. Farther in, the main corridor met with<br />

another intersection. The obvious route turned<br />

low and required crawling on a sandy floor. The<br />

obscure route required negotiating through<br />

breakdown to open into a walking passage.<br />

This nice passage was christened Indiana<br />

Avenue. The long, sandy-floored crawl led us<br />

to a connection with yet another big walking<br />

passage. Indiana Avenue would re-connect here<br />

as well. We continued inward through walking<br />

passage.<br />

The floor and walls<br />

were covered with<br />

gypsum encrustations,<br />

giving the appearance<br />

of a fresh, glistening<br />

snow. We called it<br />

Snowflake Trail. We<br />

had to skirt along<br />

the passage walls to<br />

avoid stepping in<br />

areas abundant with<br />

selenite crystals. An<br />

occasional alabaster<br />

gypsum flower was<br />

found growing under<br />

a rock. It was certainly<br />

an area of nature’s<br />

delicacy at its best.

Gypsum flowers and crusts.<br />

Beyond Snowflake Trail the passage<br />

narrowed and proceeded up a slope. At the<br />

top lay the biggest room in the cave. Its size<br />

overwhelmed the power of our headlamps.<br />

Large rows of helictites and stalagmites draped<br />

from the ceiling above where we stood. They<br />

were dwarfed by the size of the room. In front of<br />

us were large piles of a truck-sized breakdown.<br />

There was no end in sight as the room was<br />

much longer than it was wide. We stood at the<br />

entrance to this gigantic room, a place never<br />

before seen or touched by mankind, a place<br />

created long ago by<br />

the forces of nature<br />

and decorated with<br />

the beauty of earthly<br />

mineral deposits. We<br />

called it the Inner<br />

Sanctum. “This is<br />

what it’s all about,” I<br />

thought.<br />

To pass through<br />

the Inner Sanctum<br />

required skirting the<br />

wall and jumping from<br />

one breakdown block<br />

to another. With<br />

careful footwork we<br />

reached the other<br />

side and found the<br />

The Saga of Easter Pit<br />

main corridor. We<br />

continued our search<br />

inward. The passage<br />

turned the corner<br />

and became blocked<br />

by a breakdown<br />

choke. Continuing<br />

solo, Dible made a<br />

determined search<br />

through some tight<br />

crawls that led into<br />

the breakdown<br />

and he soon found<br />

the continuing<br />

route. He reported<br />

climbing high into<br />

the breakdown and<br />

finding a small hole<br />

leading up into another huge room. We called<br />

it the Room Above. It was another room of<br />

immense proportions floored by the mountain<br />

of breakdown, not as big as the Inner Sanctum,<br />

but still of great proportion. We would retreat<br />

from the cave on that first day of discovery, but<br />

not without determination to return.<br />

On November 8, 1986, the project of<br />

surveying and mapping in Easter Pit began.<br />

Exploration would continue when the survey<br />

team reached the Room Above. As cavers who<br />

become protective of their find often do, we<br />

The Inner Sanctum.<br />

23

2007 NSS Convention Guidebook<br />

installed a chain gate in Easter Pit at the slot<br />

that drops through to the trunk passage below.<br />

It actually turned out to be a helpful foothold<br />

assisting in climbing up or down in the slot<br />

and was never used as a gate. For many months<br />

to follow we would intermittently survey and<br />

explore the cave. Some trips were long and<br />

arduous, but with help of the survey data we<br />

could see the passage trends. We logged many<br />

hours during the next few years as cavers Dave<br />

Black, Holly Cook, Greg McNamara, Ron<br />

Adams, Tony Akers, George Cesnik, Tina<br />

Shirk, Roger Gleitz, Sam Frushour, and Kevin<br />

Komisarcik joined our team. We began to call<br />

ourselves the Wyandotte Ridge Exploration<br />

Group (WREG).<br />

After surveying to the Room Above, we<br />

soon found the continuing route to the main<br />

corridor lying at the bottom of a large summit<br />

of breakdown and through an obscure hole.<br />

The borehole continued. It led us to the Room<br />

Beyond. Here, another breakdown choke<br />

occurred and we thought we had reached the<br />

end. We made many searches for more passages<br />

along the paths that lead to this area. The cave<br />

was not giving up its secrets easily, but we did<br />

not abandon hope. Between the Room Above<br />

and the Room Beyond was a slippery, mudcovered<br />

hill of shale we called the Shaley Slide.<br />

Near the bottom, through a narrow crack, a<br />

24<br />

The chain slot.<br />

low side passage was<br />

found. It revealed<br />

itself to be only a<br />

series of constricted<br />

crawlways, pits,<br />

and canyons, which<br />

required an expansive<br />

digging effort to<br />

penetrate. This<br />

crawlway became<br />

known as the Radio<br />

Flyer No. 9, after the<br />

little red wagon that<br />

hauled loads and loads<br />

of dirt out of the dig.<br />

Many dig trips would<br />

follow.<br />

The digging<br />

effort revealed an energy-sucking crawlway<br />

affectionately called the Buzz Stripper that led<br />

to a tight canyon called Chisel Canyon. It was<br />

tight and contorted and always stood as my own<br />

personal dread, as it required lying on your side,<br />

positioning yourself in the center, and wriggling<br />

through without sliding down into the crack<br />

of the canyon. It goes for only a body length<br />

but nevertheless is daunting. Just on the other<br />

side of Chisel Canyon is a dome called Fools<br />

Dome. With a bright light, one could peer to<br />

the top of this 45-foot-high dome and only<br />

wonder if more passage would continue above.<br />

Below this dome, through a small obscure hole,<br />

a 33-foot-deep pit was found. Requiring a rope<br />

for descent, it is the lowest point in the cave at<br />

215.5 feet lower than the Easter Entrance. The<br />

short passage leading from it would soon end.<br />

If the cave was to continue it would have<br />

to be at the top of Fools Dome. Upon initial<br />

examination by Dible and Wilson, it was<br />

deemed climbable. On the next trip the wellseasoned<br />

climber, Wilson, made it to the top<br />

with the patient Dible providing a belay line.<br />

It was a key event in the exploration. There<br />

was passage at the top! A rope was rigged for<br />

later trips and the surveying and exploration<br />

continued in the upper level.<br />

After learning the routes and knowing<br />

how to negotiate the passages, trips to the

top of Fools Dome<br />

began to take only an<br />

average of 2 hours.<br />

At the top of Fools<br />

Dome the survey<br />

indicated a possible<br />

connection with<br />

Wyandotte Cave to<br />

the southwest. Many<br />

trips passed through<br />

a place affectionately<br />

called Sleepy Hollow,<br />

a place that became<br />

reminiscent of the<br />

many long, sleepless<br />

trips into the cave.<br />

Camping inside the<br />

cave soon became<br />

common.<br />

Not far from Sleepy Hollow the passage<br />

seemed to end, but we found a small,<br />

inconspicuous hole in the floor leading to a<br />

small crawlway. Within this crawlway an item<br />

of curiosity was found. There in front of us was<br />

an antique flashbulb lying tucked upon a small<br />

alcove. It had to have been transported to this<br />

point by pack rats. Or had it been thrown there<br />

by humans from the other side? But what and<br />

where was the “other side”? The small crawlway<br />

narrowed abruptly except for a small hole the<br />

size of a half-squashed pie pan. Air flowed from<br />

it. This hole was one of the lowest and tightest<br />

crawlways found in the cave and if not for the<br />

airflow and the flashbulb, we probably would<br />

have left it abandoned. A line plot generated<br />

from our data showed the end of Flash Bulb<br />

Crawl to be amazingly close to Avenue No. 3 in<br />

Wyandotte Cave. A connection was inevitable.<br />

After a few trips to enlarge the hole which,<br />

by the way, was made through what had to be<br />

some of the hardest mineral deposition in the<br />

cave, it became penetrable.<br />

On October 3, 1987, Wilson, Dible, and<br />

Oliphant entered the hole and connected to<br />

Echo Avenue in Wyandotte Cave. The two<br />

caves were now one. The event would remain<br />

secret for a long time as we continued mapping<br />

passages stemming from Fools Dome and<br />

A typical crawlway.<br />

The Saga of Easter Pit<br />

making a few new discovery trips into the far<br />

reaches of Wyandotte Cave.<br />

Over the past 150 years various maps and<br />

stories of Wyandotte Cave have appeared,<br />

touting its length as much as 23 miles. In the<br />

late 1960s, Dr Richard L. Powell, an Indiana<br />

state geologist (now retired), with the help<br />

of the Bloomington Indiana Grotto, mapped<br />

Wyandotte Cave for the state. Indiana was<br />

going to buy the cave from its current private<br />

ownership and a reliable map was needed. That<br />

survey provided a total length of 5.36 miles<br />

of passage in Wyandotte Cave. As a fellow<br />

caver, Dr Powell assisted us in disclosing our<br />

discoveries to the Department of Natural<br />

Resources sometime in 1989. We were allowed<br />

some time to map the newly discovered passages<br />

within Wyandotte and continue mapping in<br />

Easter Pit.<br />

Our group surveyed the following areas<br />

within Wyandotte Cave:<br />

The Adventure Trail, an extension of what<br />

is known as the Old Cave. This led from Plutos<br />

Ravine through a series of breakdown climbs; a<br />

lengthy crawl led to a short walking passage that<br />

ended in a nonforgiving breakdown choke.<br />

Kings Gauntlet, a passage found long ago<br />

but subsequent to the 1966 Powell map.<br />

Teasing Wind Trail, a crawlway extending<br />

off to the southeast from Butler Point at the far<br />

25

2007 NSS Convention Guidebook<br />

northern reaches of the cave. The air current<br />

within provided just enough tease for another<br />

expansive push effort. It ended in a large room.<br />

Rothrocks <strong>Lost</strong> Passage, another passage off<br />

Butler Point mentioned in historical data but<br />

not found by the surveyors of the 1960s.<br />

Hall of Aeacus, a large room with short<br />

passage extension that was found off of<br />

Operation Exit, a passage extending from the<br />

Senate Chamber.<br />

A bypass route to the Double Pit route.<br />

A dome with no name off the end of the<br />

Owen Report Passage.<br />

Powell’s map is still used today, with<br />

additions made by Lemasters. Easter Pit and<br />

those aforementioned Wyandotte discoveries<br />

have been added. Combined, they added 3.74<br />

miles of passages to Wyandotte Cave. Easter Pit<br />

added 2.75 miles alone. In 2001, we presented<br />

26<br />

the Department of Natural Resources with a<br />

map of the two caves merged as one. Today, the<br />

cave stands at 9.10 miles in length and 215.5<br />

feet in depth.<br />

Over the years, many stories have been told<br />

about Wyandotte Cave—reports of obscure<br />

passageways leading to grand hallways and<br />

legends of chambers that often seemed elusive<br />

to the pursuing explorer. The exploration of<br />

Easter Pit Cave and those other elusive passages<br />

within Wyandotte can now be joined with<br />

those stories. My memories of those days are<br />

unforgettable. It was an extraordinary discovery<br />

resulting from the determined efforts of many<br />

cave explorers. I was honored and humbled to<br />

be a part of the discovery. A map of Easter Pit<br />

and Wyandotte Cave is included in the map<br />

package.<br />

The lodge at Wyandotte in 1948. Photo by George Jackson.<br />

From the John Benton photo collection.

The Discovery and Exploration of the <strong>Lost</strong><br />

<strong>River</strong> Cave System,<br />

Orange County, Indiana,<br />

1996–2007 By Mark Deebel, NSS 37025RL<br />

No discussion of the geology and caves of the<br />

<strong>Lost</strong> <strong>River</strong> drainage basin in southern Indiana<br />

can be complete without at least mentioning the<br />

work of Dr Clyde Malott. A professor of geology<br />

at Indiana University for more than 25 years, he<br />

was one of the first scientists to study the caves of<br />

the <strong>Lost</strong> <strong>River</strong> area and helped pioneer the field<br />

of karst hydrology. His contributions are too<br />

numerous to mention here, but have no doubt<br />

that those of us involved with the survey of the<br />

<strong>Lost</strong> <strong>River</strong> Cave System are deeply indebted to<br />

his lifetime of work.<br />

Wesley Chapel Gulf<br />

As it applies to karst terrain, the term<br />

“gulf ” was defined by Dr Malott (1931)<br />

to describe a steep-walled depression with a<br />

flat, alluvial floor in which an underground<br />

stream rises and sinks. There are several gulfs<br />

located within the <strong>Lost</strong> <strong>River</strong> drainage basin<br />

of southern Indiana. The most prominent,<br />

Wesley Chapel Gulf, is a large oblong sinkhole<br />

oriented generally northwest to southeast<br />

(Figure 53 on page 162 [Malott’s 1931 map of<br />

Wesley Chapel Gulf ]). It has a surface area of<br />

8 acres and a perimeter of about 2,700 feet. A<br />

rise pool is located at its southern end. During<br />

severe flood conditions the entire floor of the<br />

gulf can be covered in several feet of water.<br />

This is the reason for the flat, alluvial floor.<br />

Three caves were known to be located around<br />

Wesley Chapel Gulf. Elrod Cave is located in a<br />

small sinkhole just beyond the northern edge<br />

of the gulf and several passages in it terminate<br />

at the gulf ’s northern wall. Elrod Cave has<br />

been a popular cave to visit for over a century.<br />

It contains large, easy walking passage and a<br />

nicely decorated formation room in its 2,248<br />

feet of passage. Boiling Spring Cave, located<br />

at the southern end of the gulf above the rise<br />

pool, has a large entrance room but quickly<br />

descends to water level through breakdown.<br />

The cave receives the first stages of floodwater<br />

from a rise pool at the entrance, and for this<br />

reason the majority of its 1,055-foot length<br />

is inaccessible for a good part of each year.<br />

Finally, Wesley Chapel Gulf Cave is located in<br />

the western wall of the gulf and was known to<br />

be by far the largest of the three. Surveyed in<br />

1931 by Dr Malott and several of his graduate<br />

students, they measured the cave to be nearly<br />

a mile long.<br />

During flood conditions, as water from<br />

the rise pool ascends and Boiling Spring Cave<br />

is filled to capacity, two flood channels in the<br />

floor of the gulf divert water away from the rise<br />

pool. One channel meanders northward along<br />

the entire length of the gulf. Water is diverted<br />

underground through several swallowholes<br />

along the way, the furthest north of which<br />

feeds a stream passage in Elrod Cave. The<br />

other flood channel connects the rise pool<br />

to the entrance of Wesley Chapel Gulf Cave,<br />

and at times the entrance to the cave can be<br />

completely inundated with water.<br />

When accessible, however, the majority<br />

of Wesley Chapel Gulf Cave consists of large,<br />

easy, walking borehole containing various<br />

depths of water, from ankle to waist deep. Just<br />

inside the entrance the cave splits two ways.<br />

One branch of the cave contains a stream<br />

that travels northward, roughly parallel to<br />

27

2007 NSS Convention Guidebook<br />

the western wall of the gulf. It ends abruptly<br />

after 800 feet, however, with the water<br />

disappearing through breakdown. Following<br />

the other branch of the cave, the western half,<br />

it is possible to traverse a relatively large loop,<br />

while on the way there is a mazy section which<br />

has confused more than one unwary traveler.<br />

The far western extent of the cave contains a<br />

long, deep pool of stagnant water, the end of<br />

which was represented as a series of dashed<br />

lines on Malott’s 1931 map, and was the cause<br />

of much speculation as to where, if anywhere,<br />

that might lead.<br />

The Beginning<br />

The resurvey of the caves around Wesley<br />

Chapel Gulf began with Elrod Cave on<br />

January 13, 1996. Those of us on the initial<br />

survey team included Ted Bice, Craig Cantello,<br />

Reneé VanVeld, and me. Intending to make a<br />

project out of it and eventually survey all of<br />

the caves around the gulf, we chose to begin<br />

with Elrod because it was the driest of the<br />

three. The majority of the cave’s half mile of<br />

28<br />

The entrance to Wesley Chapel Gulf Cave.<br />

passage was also walking, which made it easy<br />

for us to practice our surveying techniques. A<br />

year later, by January 1997, we had surveyed<br />

2,066 feet in Elrod Cave during five trips. Also<br />

during this time we surveyed Boiling Springs<br />

Cave and conducted a surface survey of the<br />

entire perimeter of the gulf, the rise pool, and<br />

the flood channels. We surveyed to each of the<br />

three cave entrances so they could eventually be<br />

plotted in correct relationship to each other.<br />

The survey of Wesley Chapel Gulf Cave<br />

began uneventfully on January 19, 1997, with a<br />

survey party consisting of Ted Bice and me. We<br />

expected to increase the cave’s surveyed length<br />

to over a mile, since Malott had nearly that in<br />

1931; and surely there were passages that he did<br />

not bother to survey. We thought there might<br />

be 2 miles of cave there, which, at the time,<br />

seemed like a very long cave to survey.<br />

On that first trip we started at the entrance<br />

and surveyed only 213 feet, which was all that<br />

we could do and remain dry. From that point<br />

on we would be required to get wet, no matter<br />

which direction we chose. We had completed a

previous surface survey of the gulf earlier in the<br />

day, and tied the new cave survey in to it, linking<br />

the three caves together for the first time along<br />

with an outline of the gulf itself. We returned<br />

twice that winter and then, although we caved<br />

nearly every weekend, would not return to the<br />

gulf to work on the survey until later that fall.<br />

On October 19, 1997, Ted Bice and I<br />

returned to the gulf and were joined by Tony<br />

Cunningham on the final survey trip into<br />

Elrod Cave. The trip itself was uneventful, but<br />

as we were in the process of changing out of our<br />

caving clothes and about to head home we were<br />

visited by the neighbor from across the road,<br />

Paul Blanton. He had thought that we were<br />

deer hunters but seemed disappointed to find<br />

out that we were just cavers.<br />

We knew there were supposed to be<br />

one or two small caves over on his property<br />

but had not tried to find them. We took the<br />

opportunity to ask, and Mr Blanton was more<br />

than gracious. After putting on dry clothes,<br />

Ted, Tony, and I walked across the road and<br />

into the sinkhole located behind the barn. The<br />

cave was immediately apparent. It was a nice,<br />

dry, crescent-shaped room. We were told that it<br />

had been used as a root cellar at one time since<br />

an orchard used to be on the surrounding land.<br />

There was really not much unusual about the<br />

cave however, except for a rock wall that had<br />

been built at some point, and a small hole in the<br />

floor out of which a noticeable breeze flowed.<br />

The passage looked like it kept going, but it<br />

was only 3 inches high, being blocked mostly<br />

by loose rocks and mud.<br />

We each took turns examining the<br />

hole and decided that it would definitely be<br />

worthwhile to come back and try to dig our<br />

way in, on the odd chance that there might<br />

be virgin cave through there. However, with<br />

an already long list of digs to work on and<br />

easy passages to survey in Wesley Chapel Gulf<br />

Cave, we returned three more times to survey<br />

before the end of the year. Craig Cantello, who<br />

had been involved with the survey of Elrod<br />

Cave, returned to help, and Trae Spires made<br />

his first appearance on the project during this<br />

time.<br />

The <strong>Lost</strong> <strong>River</strong> Cave System<br />

The Discovery<br />

On January 2, 1998, Ted Bice, Trae<br />

Spires, and I had planned to work in Wesley<br />

Chapel Gulf Cave for the day while teaching<br />

new surveyor Sam Russell. When we arrived at<br />

the property there was a light rain coming down<br />

and we didn’t feel comfortable going into the<br />

cave under such circumstances. Having crossed<br />

off the main goal for the day, we decided that<br />

we could still teach Sam how to survey in the<br />

small cave across the road that we had visited<br />

the previous fall.<br />

The cave was named <strong>Lost</strong> <strong>River</strong> II, and<br />

had been sketched in 1972 for a length of 75 feet.<br />

Another small cave, <strong>Lost</strong> <strong>River</strong> I, was supposed<br />

to be located elsewhere on the property. While<br />

Trae, Sam, and I quickly surveyed the small<br />

cave, Ted began digging at the small crack in<br />

the floor, which was again blowing air. By the<br />

time we completed the survey, Ted had enough<br />

room for two people to fit down through a hole<br />

and into a small alcove where the crawlway<br />

continued to slope down under the opposite<br />

wall. Large rocks were being passed out at a<br />

regular pace. Soon my pack was taken over as a<br />

digging bag as dirt and small rocks were getting<br />

hauled out. We each took turns digging, but<br />

after awhile it became very difficult to reach in<br />

the sloping crawlway, since we had been digging<br />

with only our hands all of this time. We decided<br />

to call it a day and come back later with better<br />

tools to get the job done.<br />

Ted, Trae, Sam, and I returned to the dig the<br />

next day on Saturday, January 3, accompanied<br />

by Lori and Dakota Spires. Ted and Trae, whose<br />

arms were the longest, began digging again<br />

in the sloping crawlway, this time with some<br />

small shovels and a crowbar, while the rest of us<br />

waited above in the cold cave. The only relief<br />

from the boredom was occasionally being able<br />

to empty my pack of the rocks and dirt that<br />

had been placed in it, each time seeming to take<br />

longer and longer.<br />

An hour or so passed when Ted and Trae<br />

decided to come out for a break, since Ted’s<br />

light was going dim and needed new batteries.<br />

I was curious as to how much progress they had<br />

made, and so I slid through the hole and down<br />

2

2007 NSS Convention Guidebook<br />

to the dig, accompanied by Dakota Spires, who<br />

was six years old. It was obvious that they had<br />

made quite a bit of progress since the day before.<br />

I told Dakota to look down the crawlway to<br />

see if it opened up. She slid partway down the<br />

crawlway and then came back out since it was<br />

still partially blocked by dirt and rocks. Dakota<br />

then went back up out of the dig to allow Lori<br />

to come down and take a look. I slid down into<br />

the crawlway to take a look at how much more<br />

there was to do. With my helmet off I could<br />

see that the passage turned to the right slightly<br />

where, past a small pile of dirt and rocks, there<br />

was a black void. I backed out of the crawl and<br />

asked Lori to hand me the crowbar. I slid back<br />

down the crawl and used the crowbar to push<br />

the remaining rocks and dirt down the slope<br />

into the cave.<br />

After a few minutes I couldn’t wait any<br />

longer and had made a hole big enough that<br />

I thought I could fit through. I pushed my<br />

helmet in front of me and began to slide<br />

downhill through the last few feet of the<br />

dig. I had to exhale to pass through at one<br />

point, but once that was over the rest of<br />

me passed through without any problem.<br />

That is, except for my sweatpants, which<br />

had been pulled down to my ankles while<br />

passing through the tight spot. I was going<br />

to turn around and dig a little more from<br />

the inside to enlarge the last few feet of<br />

the crawl for everyone, but before I could<br />

even pull up my sweatpants Lori was<br />

coming through. I backed up to get out of<br />

the way, as everyone was lining up to get<br />

into the newly-discovered virgin cave.<br />

We had slid into one end of a long room<br />

about 4 feet high. The floor was mud and<br />

breakdown. At the where we were sitting was a<br />

talus slope, which is what we had dug through<br />

at the ceiling. The room turned out to be<br />

about 60 feet long and 15 feet wide. A tight<br />

crawlway led off from the far left corner into<br />

the darkness. We rushed down it, and only 20<br />

feet later it opened back up into a hands-andknees<br />

crawl in a wide, “V”-shaped passage<br />

with a mud floor. The distant sound of water<br />

could be heard. After continuing to follow<br />

30<br />

the crawlway we suddenly found ourselves<br />

sitting on the edge of a large mud bank about<br />

40 feet wide. Below us a very large amount of<br />

water was moving swiftly from left to right.<br />

The opposite wall was 60 feet away and the<br />

ceiling was 30 feet high. We were frozen in<br />