Symbol & Allegory The Road Not Taken Two roads diverged in a yello

Symbol & Allegory The Road Not Taken Two roads diverged in a yello

Symbol & Allegory The Road Not Taken Two roads diverged in a yello

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

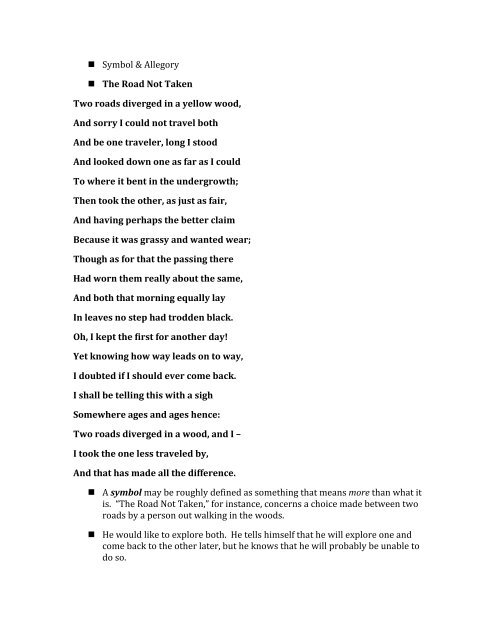

n <strong>Symbol</strong> & <strong>Allegory</strong><br />

n <strong>The</strong> <strong>Road</strong> <strong>Not</strong> <strong>Taken</strong><br />

<strong>Two</strong> <strong>roads</strong> <strong>diverged</strong> <strong>in</strong> a <strong>yello</strong>w wood,<br />

And sorry I could not travel both<br />

And be one traveler, long I stood<br />

And looked down one as far as I could<br />

To where it bent <strong>in</strong> the undergrowth;<br />

<strong>The</strong>n took the other, as just as fair,<br />

And hav<strong>in</strong>g perhaps the better claim<br />

Because it was grassy and wanted wear;<br />

Though as for that the pass<strong>in</strong>g there<br />

Had worn them really about the same,<br />

And both that morn<strong>in</strong>g equally lay<br />

In leaves no step had trodden black.<br />

Oh, I kept the first for another day!<br />

Yet know<strong>in</strong>g how way leads on to way,<br />

I doubted if I should ever come back.<br />

I shall be tell<strong>in</strong>g this with a sigh<br />

Somewhere ages and ages hence:<br />

<strong>Two</strong> <strong>roads</strong> <strong>diverged</strong> <strong>in</strong> a wood, and I –<br />

I took the one less traveled by,<br />

And that has made all the difference.<br />

n A symbol may be roughly def<strong>in</strong>ed as someth<strong>in</strong>g that means more than what it<br />

is. “<strong>The</strong> <strong>Road</strong> <strong>Not</strong> <strong>Taken</strong>,” for <strong>in</strong>stance, concerns a choice made between two<br />

<strong>roads</strong> by a person out walk<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the woods.<br />

n He would like to explore both. He tells himself that he will explore one and<br />

come back to the other later, but he knows that he will probably be unable to<br />

do so.

n By the last stanza, however, we realize that the poem is about someth<strong>in</strong>g<br />

more than the choice of paths <strong>in</strong> a wood, for that choice would be relatively<br />

unimportant.<br />

n This poem is about a critical life-‐alter<strong>in</strong>g choice.<br />

n Why a road?<br />

n We must <strong>in</strong>terpret the poet’s choice of a road as a symbol for any choice <strong>in</strong><br />

life between alternatives that appear almost equally attractive but will result<br />

through the years <strong>in</strong> a large difference <strong>in</strong> the k<strong>in</strong>d of experience one knows.<br />

n Image, metaphor, and symbol shade <strong>in</strong>to each other and are sometimes<br />

difficult to dist<strong>in</strong>guish.<br />

n Here’s an easy-‐to-‐follow breakdown:<br />

n In general, an image means only what it is.<br />

n <strong>The</strong> figurative term <strong>in</strong> a metaphor means someth<strong>in</strong>g other than what it is.<br />

n And a symbol means what it is and someth<strong>in</strong>g more, too.<br />

n A symbol functions literally and figuratively at the same time.<br />

n If I say that a shaggy brown dog was rubb<strong>in</strong>g its back aga<strong>in</strong>st a white picket<br />

fence, I am talk<strong>in</strong>g about noth<strong>in</strong>g more than a dog (and a picket fence) and<br />

am therefore present<strong>in</strong>g an image.<br />

n If I say, “Some dirty dog stole my wallet at the party,” I am not talk<strong>in</strong>g about a<br />

dog at all and am therefore us<strong>in</strong>g a metaphor.<br />

n BUT if I say, “You can’t teach an old dog new tricks,” I am talk<strong>in</strong>g not only<br />

about dogs but about liv<strong>in</strong>g creatures of any species and am therefore<br />

speak<strong>in</strong>g symbolically.<br />

n Images do not cease to be images when they become <strong>in</strong>corporated <strong>in</strong><br />

metaphors or symbols. We simply use the term most relevant to the aspect<br />

of the poem we are discuss<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

n If we’re discuss<strong>in</strong>g the sensuous qualities of “<strong>The</strong> <strong>Road</strong> <strong>Not</strong> <strong>Taken</strong>,” we would<br />

refer to the two leaf-‐strewn <strong>roads</strong> as an image.<br />

n If we are discuss<strong>in</strong>g the significance of the poem, we will talk about the <strong>roads</strong><br />

as symbols.<br />

n <strong>The</strong> symbol is usually so general <strong>in</strong> its mean<strong>in</strong>g that it can suggest a great<br />

variety of specific mean<strong>in</strong>gs.

n “<strong>The</strong> <strong>Road</strong> <strong>Not</strong> <strong>Taken</strong>” concerns a choice <strong>in</strong> life, but what choice? Was it a<br />

choice of profession? A choice of residence? A choice of mate? It could be all<br />

or none…<br />

n We cannot def<strong>in</strong>itively answer this question, and it is not important that we<br />

do so.<br />

n It is enough if we see <strong>in</strong> the poem an expression of regret that the<br />

possibilities of life experience are so sharply limited.<br />

n Because the symbol is a rich one, other mean<strong>in</strong>gs are also suggested.<br />

n It affirms a belief <strong>in</strong> the possibility of choice (as opposed to fate) and says<br />

someth<strong>in</strong>g about the nature of choice – how each choice narrows the range of<br />

possible future choices, so that we make our lives as we go, both freely<br />

choos<strong>in</strong>g and be<strong>in</strong>g determ<strong>in</strong>ed by past choices.<br />

n Though not a philosophical poem, it comments on the issue of free will and<br />

<strong>in</strong>dicates the poet’s own position. It can do all these th<strong>in</strong>gs, concretely and<br />

compactly, by its use of an effective symbol.<br />

n Consider the follow<strong>in</strong>g poem…<br />

n <strong>The</strong> Sick Rose<br />

Rose, thou art sick!<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>in</strong>visible worm<br />

That flies <strong>in</strong> the night,<br />

In the howl<strong>in</strong>g storm,<br />

Has found out thy bed<br />

Of crimson joy<br />

And his dark secret love<br />

Does thy life destroy<br />

William Blake (1757-‐1827)<br />

1. What figures of speech do you f<strong>in</strong>d <strong>in</strong> the poem <strong>in</strong> addition to symbol? How<br />

do they contribute to its force or mean<strong>in</strong>g?<br />

2. Can you th<strong>in</strong>k of and expla<strong>in</strong> a symbolic <strong>in</strong>terpretation of the poem?<br />

n <strong>The</strong> rose, apostrophized and personified <strong>in</strong> the first l<strong>in</strong>e, has traditionally<br />

been a symbol fem<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>e beauty and love, as well as of sensual pleasures.

n “Bed” can refer to woman’s bed as well as to a flower bed.<br />

n “Crimson joy” suggests the pleasure of passionate lovemak<strong>in</strong>g, as well as the<br />

brilliant beauty of a red flower.<br />

n <strong>The</strong> “dark secret of love” of the “<strong>in</strong>visible worm” is more strongly suggestive<br />

of a concealed or illicit love affair than of the feed<strong>in</strong>g of a cankerworm on a<br />

plant, though it fits that too.<br />

n For all these reasons, the rose almost immediately suggests a woman and the<br />

worm her secret lover – and the poem suggests the corruption of <strong>in</strong>nocent<br />

but physical love by concealment and deceit.<br />

n <strong>The</strong> worm is a common symbol or metonymy for death, and fans of Jon<br />

Milton (like Blake) would recall the “undy<strong>in</strong>g worm” of Paradise Lost,<br />

Milton’s metaphor for the snake that tempted Eve.<br />

n Are other <strong>in</strong>terpretations possible?<br />

n Yes.<br />

n “<strong>The</strong> Sick Rose” has been <strong>in</strong>terpreted as referr<strong>in</strong>g to the destruction of love<br />

by jealousy, deceit, or the possessive <strong>in</strong>st<strong>in</strong>ct; of <strong>in</strong>nocence by experience; of<br />

imag<strong>in</strong>ation and joy by analytic reason; of life by death.<br />

n We cannot say for sure what the poet had <strong>in</strong> m<strong>in</strong>d, nor do we need to.<br />

n A symbol def<strong>in</strong>es an area of mean<strong>in</strong>g, and any <strong>in</strong>terpretation that falls with<strong>in</strong><br />

that area is permissible.<br />

n In Blake’s poem, the rose stands for someth<strong>in</strong>g beautiful, or desirable, or<br />

good.<br />

n <strong>The</strong> worm stands for some corrupt<strong>in</strong>g agent.<br />

n With<strong>in</strong> these limits, the mean<strong>in</strong>g is largely “open.”<br />

n For <strong>in</strong>stance, the poem may rem<strong>in</strong>d some of a gifted friend whose promise<br />

and potential have been destroyed by drug addiction.<br />

n Digg<strong>in</strong>g<br />

Between my f<strong>in</strong>ger and my thumb<br />

<strong>The</strong> squat pen rests; snug as a gun.<br />

Under my w<strong>in</strong>dow, a clean rasp<strong>in</strong>g sound<br />

When the spade s<strong>in</strong>ks <strong>in</strong>to gravelly ground:<br />

My father, digg<strong>in</strong>g. I look down

Till his stra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g rump among the flowerbeds<br />

Bends low, comes up twenty years away<br />

Stoop<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> rhythm through potato drills<br />

Where he was digg<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

<strong>The</strong> coarse boot nestled on the lug, the shaft<br />

Aga<strong>in</strong>st the <strong>in</strong>side knee was levered firmly.<br />

He rooted out tall tops, buried the bright edge deep<br />

To scatter new potatoes that we picked<br />

Lov<strong>in</strong>g their cool hardness <strong>in</strong> our hands.<br />

By God, the old man could handle a spade.<br />

Just like his old man<br />

My grandfather cut more turf <strong>in</strong> a day<br />

Than any other man on Toner’s bog.<br />

Once I carried him milk <strong>in</strong> a bottle<br />

Corked sloppily with paper. He straightened up<br />

To dr<strong>in</strong>k it, then fell to right away<br />

Nick<strong>in</strong>g and slic<strong>in</strong>g neatly, heav<strong>in</strong>g sods<br />

Over his shoulder, go<strong>in</strong>g down and down<br />

For the good turf. Digg<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>The</strong> cold smell of potato mould, the squelch and slap<br />

Of soggy peat, the curt cuts of an edge<br />

Through liv<strong>in</strong>g roots awaken <strong>in</strong> my head.<br />

But I’ve no spade to follow men like them.<br />

Between my f<strong>in</strong>ger and my thumb<br />

<strong>The</strong> squat pen rests.<br />

I’ll dig with it.<br />

Seamus Heaney (b. 1939)

What emotional responses are evoked by the imagery?<br />

On the literal level, what does this poem present?<br />

-‐a writer who <strong>in</strong>terrupts himself to have a look at his<br />

digg<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> a flower garden below his w<strong>in</strong>dow. He is<br />

rem<strong>in</strong>ded of his father twenty years earlier, and by that<br />

memory is drawn farther back to his grandfather<br />

digg<strong>in</strong>g peat from a bog for fuel.<br />

n What clues us <strong>in</strong> to the idea that there is more go<strong>in</strong>g on than meets the eye?<br />

n <strong>The</strong> title and the emphasis on varieties of the same task carried out <strong>in</strong> several<br />

different ways over a span of generations alert the reader to the need to<br />

discover the further significance of this literal statement.<br />

n <strong>The</strong> last l<strong>in</strong>e is metaphorical, compar<strong>in</strong>g digg<strong>in</strong>g to writ<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

n Is it also symbolic?<br />

n No, because on a literal level, one cannot dig with a pen.<br />

n <strong>The</strong> symbolism comes from the act of digg<strong>in</strong>g itself.<br />

n Digg<strong>in</strong>g has mean<strong>in</strong>gs that relate to basic needs – for warmth, for<br />

sustenance, for beauty, and for the personal satisfaction of do<strong>in</strong>g a job<br />

well.<br />

n In the conclud<strong>in</strong>g metaphor, one basic need is implied, the need to remember<br />

and confront one’s orig<strong>in</strong>s, to f<strong>in</strong>d oneself <strong>in</strong> a cont<strong>in</strong>uum of mean<strong>in</strong>gful<br />

activities, to assert the relevance and importance of one’s vocation.<br />

n Mean<strong>in</strong>gs ray out from a symbol, like the corona around the sun or like<br />

connotations around a richly suggestive word.<br />

n However, we must use tact and careful judgment when <strong>in</strong>terpret<strong>in</strong>g symbols.<br />

n Although Blake’s “<strong>The</strong> Sick Rose” might rem<strong>in</strong>d us of drug addiction, it would<br />

be unwise to say that Blake uses the rose to symbolize this.<br />

n This <strong>in</strong>terpretation is private and narrow. <strong>The</strong> poem allows it, but does not<br />

itself suggest it.<br />

n Just because a symbol is “open,” we cannot make it say anyth<strong>in</strong>g we choose.<br />

We have to stay with<strong>in</strong> the range of the text.

n To <strong>in</strong>terpret “<strong>The</strong> <strong>Road</strong> <strong>Not</strong> <strong>Taken</strong>” as a choice between good and evil is to<br />

impose mean<strong>in</strong>g that is simply not there.<br />

n <strong>The</strong> poem tells us that the <strong>roads</strong> are much alike and lie “<strong>in</strong> leaves no step had<br />

trodden black.”<br />

n Whatever the choice may be, it is one between two goods.<br />

n <strong>The</strong> reader who reads <strong>in</strong>to such a poem anyth<strong>in</strong>g imag<strong>in</strong>able might as well<br />

discard the poem and simply daydream.<br />

n Avoid symbol-‐hunt<strong>in</strong>g. It is better to miss a symbol or two than to attempt to<br />

f<strong>in</strong>d one <strong>in</strong> every l<strong>in</strong>e of a poem.<br />

n Lastly, an allegory is a narrative or description that has a second mean<strong>in</strong>g<br />

beneath the surface.<br />

n Although the surface story or description may have its own <strong>in</strong>terest, the<br />

author’s major <strong>in</strong>terest is <strong>in</strong> the ulterior mean<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

n Examples of allegories:<br />

n Lord of the Flies<br />

n Animal Farm<br />

n <strong>The</strong> Matrix<br />

n V for Vendetta<br />

n Avatar