Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Introduction<br />

Welcome to <strong>Haud</strong> <strong>Yer</strong> <strong>Tongue</strong>, a series of five<br />

programmes for 10–14 year olds which explores the<br />

Scots language and offers support to teachers who are<br />

interested in ensuring that young people in Scottish<br />

schools have the opportunity to learn more about<br />

their own language. The series will also be of interest<br />

to all teachers who are keen to develop an<br />

understanding of language diversity and to increase<br />

their pupils’ knowledge about language in general.<br />

The series is introduced by Billy Kay, the writer and<br />

broadcaster. The programmes look at the history of<br />

the Scots language and investigate its development,<br />

tracing the impact of other languages on its<br />

vocabulary and structures and examining the<br />

influence of cultural events. The literary heritage of<br />

the language is also explored and contemporary<br />

writers and singers are featured. Scottish children and<br />

adults from all parts of the country talk about the<br />

language they speak and how it affects their identity.<br />

This offers the opportunity not only to note the<br />

similarities and differences within the various dialects,<br />

but also to discuss some of the more controversial<br />

issues surrounding language and culture.<br />

The programmes not only look to the past, but to the<br />

future, and emphasise that language is a living thing,<br />

capable of adaptation and change. Above all, the<br />

programmes stress how important it is for people to<br />

be able to express themselves freely and with<br />

confidence. Language diversity adds to the richness of<br />

our culture and is seen not as a threat, but as<br />

something to be valued and in which to take pride.<br />

<strong>Haud</strong> <strong>Yer</strong> <strong>Tongue</strong> is supported by this<br />

Teachers’ Guide, which offers suggestions for<br />

classroom activities and adds to the information given<br />

on-screen.<br />

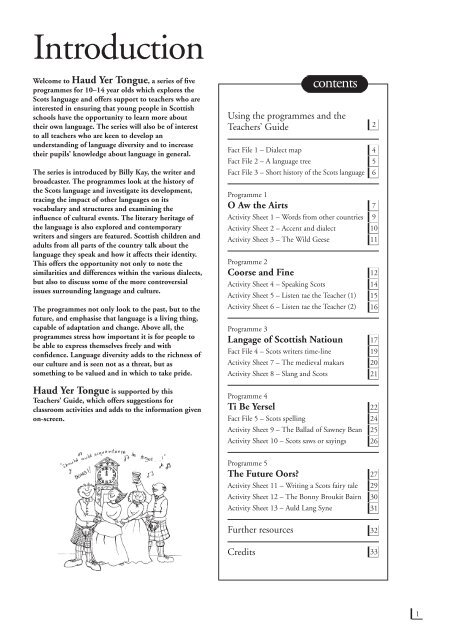

Using the programmes and the<br />

Teachers’ Guide<br />

Fact File 1 – Dialect map<br />

Fact File 2 – A language tree<br />

Fact File 3 – Short history of the Scots language<br />

Programme 1<br />

O Aw the Airts<br />

Activity Sheet 1 – Words from other countries<br />

Activity Sheet 2 – Accent and dialect<br />

Activity Sheet 3 – The Wild Geese<br />

Programme 2<br />

Coorse and Fine<br />

Activity Sheet 4 – Speaking Scots<br />

Activity Sheet 5 – Listen tae the Teacher (1)<br />

Activity Sheet 6 – Listen tae the Teacher (2)<br />

Programme 3<br />

Langage of Scottish Natioun<br />

Fact File 4 – Scots writers time-line<br />

Activity Sheet 7 – The medieval makars<br />

Activity Sheet 8 – Slang and Scots<br />

Programme 4<br />

Ti Be <strong>Yer</strong>sel<br />

Fact File 5 – Scots spelling<br />

Activity Sheet 9 – The Ballad of Sawney Bean<br />

Activity Sheet 10 – Scots saws or sayings<br />

Programme 5<br />

The Future Oors?<br />

Activity Sheet 11 – Writing a Scots fairy tale<br />

Activity Sheet 12 – The Bonny Broukit Bairn<br />

Activity Sheet 13 – Auld Lang Syne<br />

Further resources<br />

Credits<br />

contents<br />

2<br />

4<br />

5<br />

6<br />

7<br />

9<br />

10<br />

11<br />

12<br />

14<br />

15<br />

16<br />

17<br />

19<br />

20<br />

21<br />

22<br />

24<br />

25<br />

26<br />

27<br />

29<br />

30<br />

31<br />

32<br />

33<br />

1

2<br />

<strong>Haud</strong> <strong>Yer</strong> <strong>Tongue</strong><br />

Using the programmes and the Teachers’ Guide<br />

This booklet provides information and<br />

classroom activities to support the 4 Learning<br />

programmes about Scots language. The<br />

SOEID’s English Language Guidelines 5–14<br />

state that ‘the speech of Scottish people is often<br />

distinctive ... The first tasks of schools are<br />

therefore to enable pupils to be confident and<br />

creative in this language and to begin to<br />

develop the notion of language diversity’. The<br />

document also adds, ‘terms such as dialect and<br />

accent should be explained and used’.<br />

Throughout the programmes, pupils will hear<br />

the everyday voices of Scottish children and<br />

adults from all parts of the country. Songs,<br />

stories and poems in Scots – traditional and<br />

contemporary – will also be heard, as well as<br />

information about the history of the language<br />

and attitudes to Scots in society.<br />

The delivery of this information is often<br />

entertaining as well as educational. It permeates<br />

the programmes rather than being confined to<br />

individual parts of the series. However, each<br />

programme focuses on particular issues and<br />

themes, shown in this Guide in the programme<br />

synopses. While a main theme is identified in<br />

each programme, various issues are revisited<br />

during the course of the series. A build-up of<br />

knowledge should take place rather than<br />

discrete compartmentalised gathering of<br />

information.<br />

The support notes provide further linguistic<br />

and literary detail with reference to individual<br />

programme content.<br />

Fact-file pages are supplied to help explain<br />

linguistic and literary details.<br />

Fact files included are:<br />

1 Dialect map (courtesy of the Scottish<br />

National Dictionary Association). This allows<br />

pupils to locate people and voices for reference<br />

geographically throughout programmes.<br />

2 A language tree. This shows the main Indo-<br />

European languages and helps set Scots in a<br />

linguistic context.<br />

3 Short history of the Scots language.<br />

4 Scots writers time-line – referred to in the<br />

programmes.<br />

5 Scots spelling.<br />

In each programme one of the activity sheets<br />

focuses on literature and provides the text of a<br />

poem, prose extract or song.<br />

A resource list is supplied at the end of the<br />

book for further reading and reference as well as<br />

useful addresses and websites.<br />

Learning outcomes<br />

The workbook activities are designed to<br />

increase knowledge about Scots and its dialects<br />

as well as to increase pupils’ confidence and<br />

experience in reading, writing and talking in<br />

and about Scots.<br />

Activities are included which involve learning<br />

outcomes across all four strands of Listening,<br />

Talking, Reading and Writing.<br />

Many of the activities meet suggestions to be<br />

found in the 5–14 English Language<br />

document’s ‘Knowledge About Language’<br />

section. By Level D, it is suggested that ‘slang<br />

will be a term used in the discussion of diversity<br />

within spoken English’. Pupils will learn about<br />

the differences between accent and dialect:<br />

‘Accents will be a term used in considering<br />

diversity within spoken English’ (Level C) and<br />

‘standard English and dialect are necessary<br />

terms...’ (Level D).<br />

Pupils’ spoken language<br />

The range of ability and knowledge about Scots<br />

will vary within schools. A continuum will<br />

exist, from the pupils who are fluent native<br />

speakers of Scots, to those who speak Scottish<br />

Standard English (basically English with some<br />

Scots vocabulary), to those who neither speak<br />

nor understand it. The programmes and<br />

worksheets will be used in varying ways<br />

depending on the pupils’ and the teacher’s own<br />

stage of competence. In the main, the focus will<br />

be for Scots speakers, but frequently activities<br />

will be suitable for non-Scots speakers also – for

example, when literary texts are studied.<br />

Individual teachers will tailor resources to their<br />

own needs, differentiating not only by<br />

academic ability but also by recognising varying<br />

degrees of competence in Scots.<br />

Synopsis<br />

Programme 1<br />

Dialect variation throughout Scotland.<br />

Historical and foreign influences. Migrations of<br />

Scots and language legacy.<br />

Programme 2<br />

Hert an heid. The debate between Scots and<br />

English. Growing up in Scotland with language<br />

confusion.<br />

Programme 3<br />

The long pedigree of Scots literature. Some<br />

major Scots makars are introduced.<br />

Programme 4<br />

Current uses of Scots language for song,<br />

storytelling, poetry and prose and in society.<br />

Programme 5<br />

The future of the language.<br />

Key vocabulary<br />

A word list (leid leet) will be included for every<br />

programme. Teachers might use these to build<br />

up a dictionary of Scots-English and English-<br />

Scots. The words could be used in speaking or<br />

writing exercises, sentence creation, dialoguewriting,<br />

or illustrating with pictures. For many<br />

pupils it will be their first encounter with<br />

written Scots, and a gradual approach to<br />

writing might be desirable. It may be the basis<br />

for a class dictionary to which pupils add their<br />

own, families’ or friends’ Scots vocabulary.<br />

Before viewing<br />

Teachers may wish to carry out discussion or<br />

activities with pupils before viewing episodes.<br />

These are highlighted in the notes for each<br />

programme. The use of fact files will also be<br />

helpful.<br />

During viewing<br />

Extensive note-making should perhaps be<br />

avoided during viewing. Light noting of<br />

vocabulary or facts is recommended, and<br />

sometimes you might wish to return to<br />

particular parts of a programme or pause during<br />

transmission to explain particular points.<br />

Because the language may be unfamiliar to<br />

some pupils they may need to hear certain<br />

vocabulary again.<br />

After viewing<br />

Activity sheets are supplied for each programme.<br />

These consist of varied tasks for pupils to<br />

undertake. Activities related to Talking and<br />

Listening, and Reading and Writing, are<br />

included. Occasionally, cross-curricular<br />

suggestions are made which refer to the expressive<br />

arts and environmental studies curricula. Often<br />

songs or poems could be glossed and discussed,<br />

then memorised. Several of the ‘fact file’ pages<br />

will be useful for more than one programme and<br />

teachers may wish to encourage pupils to compile<br />

a Scots-language folder of their own in the course<br />

of watching all five programmes. Illustrating the<br />

front cover with Scots vocabulary and linked<br />

pictures will start the process of seeing Scots and<br />

becoming familiar with it. As pupils complete<br />

tasks and produce writing in Scots, they could<br />

add these to their booklets.<br />

You may wish to assess the work carried out in<br />

relation to the programmes. This can be done<br />

in the same way that English language is<br />

assessed. You may wish to insert a check list and<br />

assessment page in a pupil booklet. It might be<br />

interesting to include a diary section for pupils<br />

to enter their own responses to watching the<br />

programmes.<br />

3

4<br />

factfile 1<br />

Reference<br />

North East North<br />

Central<br />

South {<br />

East Central<br />

West Central<br />

South West<br />

H A U D Y E R T O N G U E<br />

Dialect map

factfile 2<br />

A language tree<br />

H A U D Y E R T O N G U E<br />

5

6<br />

factfile 3<br />

Short history of the Scots<br />

language<br />

Pre-5th century Pictish language. Ogam script – still difficult to decipher. Also a form<br />

of Welsh Brithonic was spoken in some parts of Scotland.<br />

5th century Arrival of Gaelic from Ireland.<br />

H A U D Y E R T O N G U E<br />

5th–8th centuries Angles and Saxons came to Britain. Inglis language came to Scotland<br />

and north England (Northumbria). Inglis developed into Scots in<br />

Scotland and English in England.<br />

11th–15th centuries Throughout this time Norse, Danish, Latin, French and Gaelic<br />

influenced Scots. Like all languages, Scots contains words from other<br />

countries.<br />

1424 By now, the language was called Scottis and was quite different, but<br />

still related, to English. Scots was spoken by royalty and used, with<br />

Latin, for official documents. It was the official language of Scotland.<br />

15th century Henryson and Dunbar wrote in Scots. King James IV greatly<br />

encouraged his Scots writers at court.<br />

16th century The Geneva Bible was translated into English but not Scots. Many<br />

Scots therefore wanted to learn English.<br />

1603 Union of Crowns. King James VI of Scotland became James I of<br />

England, too. He moved to London with his court. English became<br />

more popular with royalty and writers.<br />

1707 Union of Parliaments of Scotland and England. English became the<br />

official language of Scotland instead of Scots, though it was still<br />

spoken by the people.<br />

18th century A highly popular revival of written Scots by Robert Burns, Allan<br />

Ramsay and Robert Fergusson.<br />

1872 Scottish Education Act banned Scots from schools.<br />

20th century Revival again of written Scots. Hugh MacDiarmid used it for highly<br />

intellectual poetry.<br />

1991 Scottish Office National Guidelines encourage Scots in schools.<br />

1999 Higher Still exam encourages written Scots and Scots-language<br />

studies.

PROGRAMME<br />

1<br />

O Aw the Airts<br />

Programme outline<br />

Billy Kay, writer and broadcaster, introduces us to the<br />

voices of Scots speakers across the country. A brief<br />

outline is given of the history of Scots and foreign<br />

influences on the Scots language, including, for example,<br />

Old English, French, Latin, Norse and Gaelic.<br />

We visit the north-east of Scotland and hear from Steve<br />

Murdoch. Matthew Fitt talks about using the Internet to<br />

let pupils communicate in Scots.<br />

The dialect variations of Scots are named and Billy<br />

explains that he will travel all over the country to let us<br />

hear the voices. We hear ‘First Gemme’, a poem about<br />

football, from Derek Ross of Stranraer.<br />

There is an interview with an American named Donald<br />

McDonald about the linguistic influence of migratory<br />

Scots in countries such as America.<br />

A poem called ‘Scotland Oor Mither’ by Charles Murray<br />

is recited, and ‘The Wild Geese’ by Violet Jacob is sung<br />

by Sheena Wellington.<br />

The linguistic influence of migratory Scots in other<br />

countries, particularly America, is discussed.<br />

The changing status of the language is referred to, and<br />

the sometimes controversial aspects surrounding this<br />

complex language in the twentieth century. The attitudes<br />

and experiences of various Scots speakers are heard and<br />

we are made aware of the difficulties surrounding the use<br />

of the language. Favourite words are presented<br />

throughout the programme by pupils and adults.<br />

Learning outcomes<br />

Pupils will learn:<br />

● that the Scots language has a very long pedigree, where<br />

it has come from and the fact that it has been<br />

influenced by other languages and countries;<br />

● that Scots, like English, is a fluid and changing thing;<br />

● to appreciate the diversity of modern Scots and<br />

recognise that it is still spoken throughout the country<br />

by people of all ages;<br />

● that the Scots language is used for high-quality<br />

literature on a wide range of themes;<br />

● about written Scots, developing knowledge about<br />

spelling and speaking Scots.<br />

H A U D Y E R T O N G U E<br />

Leid leet<br />

bahookie (bottom)<br />

wanchancie (unreliable)<br />

dirdum (backside)<br />

grozet (gooseberry)<br />

vennels (streets)<br />

ports (gates)<br />

ashet (dish)<br />

tassie (cup)<br />

Doric (north-east Scots)<br />

shelpit (thin)<br />

lug (ear)<br />

fit lyke? (how are you?)<br />

Before viewing<br />

You might wish to ask questions to find out what<br />

they already know about Scots. Do pupils speak Scots?<br />

Can they understand it? The same questions might be<br />

asked first of all about the English language. What is a<br />

language? What language do the pupils speak? Is it<br />

English or Scots? Do they know?<br />

Pupils could be asked where English came from.<br />

What do they think Scots is? Where did the language<br />

come from? They might discuss whether they ever find<br />

themselves changing the way they speak.<br />

Notes might be made at this point in order that<br />

comparisons can be made later.<br />

During viewing<br />

Fact File 1 ‘Dialect map’ might be reproduced for<br />

each pupil to look at when various locations are visited.<br />

This helps to link dialects and accents to different parts<br />

of the country.<br />

Activity Sheet 1<br />

‘Words from other<br />

countries’ lists Scots words<br />

with a foreign influence.<br />

The sheet could be filled<br />

in during viewing.<br />

quines (girls)<br />

loons (boys)<br />

aucht (eight)<br />

bloater (kick)<br />

coortin (courting)<br />

heeligoleerie<br />

(state of confusion)<br />

poke (bag)<br />

totie (tiny)<br />

besom (rascal)<br />

chavin awa (working hard)<br />

7

8<br />

After viewing<br />

Compare the pupils’ initial ‘before viewing’ responses<br />

and the notes taken during the programme.<br />

Pupils could be asked to identify their own speech.<br />

How broad is their Scots? Is it English with a Scottish<br />

accent? (See ‘Knowledge about language’ below.)<br />

Fact File 2 ‘A language tree’ shows Scots in a wide<br />

linguistic context. It will help to involve pupils in the<br />

class from outside Scotland. Scots is shown in relation to<br />

English, a close cousin from the same branch. You might<br />

point out how far away on the tree Gaelic is. Discussion<br />

might take place on the ways in which a language so far<br />

removed from the indigenous ones arrives in a country.<br />

Fact File 3 ‘Short history of the Scots language’ might<br />

be cross-referenced with the above discussion on Indo-<br />

European languages.<br />

Pupils could discuss whether they have relatives in<br />

other countries and when or why they left Scotland.<br />

You can decide about the order in which to present these<br />

fact files.<br />

Knowledge about<br />

language<br />

It may be helpful to establish definitions of linguistic<br />

terms in order that future discussion will be clearly<br />

understood by most levels of ability. You may differentiate<br />

if necessary, but terms such as accent, dialect and slang are<br />

recommended at levels C and D.<br />

Activity Sheet 2 ‘Accent and dialect’ gives pupils<br />

opportunities to examine these definitions.<br />

Information for teachers<br />

For some people, Scots has become a language with low<br />

status rather than an ancient language with its own<br />

literature. Differentiating between Scots and slang is an<br />

important first step because often Scots has become<br />

synonymous with slang. Scots speakers are sometimes<br />

erroneously accused of ‘just speaking slang’.<br />

Slang is usually a modern, informal language. Because<br />

Scots has been restricted to the home, the playground or<br />

the company of friends, it is modern and informal too,<br />

and easily confused with slang. At one time Scots was<br />

capable of all registers, formal and informal. Listening to<br />

the various adults and children speaking in the<br />

programmes about the current status of Scots, and<br />

whether it should be used formally, will prompt lively<br />

classroom discussion.<br />

The same slang words can be heard outside Scotland –<br />

‘okay’, ‘he’s got a nerve’, ‘you must be kidding’, ‘taking<br />

the mickey’. They are not Scots. Scots words mostly have<br />

an ancient pedigree and often can be found in the<br />

literature of Scotland. Of course, modern Scots speech<br />

contains slang expressions, as does any twentieth-century<br />

language.<br />

Pupils and writers might use slang in the dialogue of their<br />

creative writing, but teachers may want to raise linguistic<br />

awareness amongst pupils as to what is slang and what is<br />

Scots. The SOEID’s English Language Guidelines 5–14<br />

suggest that ‘slang will be a term used in the discussion of<br />

diversity within spoken English’ (Level D, Knowledge<br />

about language).<br />

Activity Sheet 4 ‘Speaking Scots’ (supplied with<br />

Programme 3) will help explain these points.<br />

Activity Sheet 3 ‘The Wild Geese’. Pupils might be asked to<br />

translate the poem into English or to ‘gloss’ any words they<br />

are not sure about. You can treat the poem exactly as you<br />

would an English poem and analyse it for content and<br />

meaning as well as form and poetic techniques. Pupils<br />

might look carefully at where speech marks occur and<br />

decide why they are used. They could write four paragraphs<br />

to parallel the four verses. They might be asked which<br />

words could also have been in Scots. For example, in the<br />

words whit/what, ma/my, A’m/I’m, choices have been made.<br />

You might discuss rhythm, rhyme, verse, and lineage.<br />

Expressive arts<br />

Pupils could learn to sing the song, play music to it, or<br />

act it out as a drama. ‘The Wild Geese’ is available on the<br />

CD Clear Song by Sheena Wellington, from Dunkeld<br />

Records. Pupils might draw and write a storyboard for<br />

‘The Wild Geese’ or make a wall display with bubbles for<br />

speech captions for the North Wind and the traveller.<br />

This could be adapted for the less able, with very little<br />

writing required.<br />

Environmental studies<br />

Pupils could locate Angus, the River Tay and the Firth of<br />

Forth in relation to England on maps. The reference to<br />

the ‘siller tides’ could be discussed and classes asked which<br />

fish are being referred to.

Words from other countries<br />

During the programme you will discover that many Scots words have come from other countries.<br />

Listen during the programme and try to fill in the chart.<br />

Words From which country? English meaning<br />

grozet fair<br />

stoursooker<br />

ashet<br />

port<br />

vennel<br />

ben<br />

glen<br />

tassie<br />

poke<br />

dux<br />

janitor<br />

oxter<br />

dinna fash yersel<br />

stane<br />

Quiz<br />

Work out a Scots/English word for each of a) to e) below.<br />

Which country does each word come from?<br />

a) where you go for a coke with friends<br />

b) a dance at the village hall<br />

c) a popular alcoholic drink for adults<br />

d) a big fuss or fight<br />

e) your little finger<br />

A CTIVITY SHEET 1<br />

HAUD YER TONGUE © 2000 CHANNEL FOUR TELEVISION CORPORATION<br />

9

10<br />

Accent and dialect<br />

Accent means the way you pronounce words.<br />

Dialect means the words you actually use.<br />

Accent<br />

Everyone speaks with an accent. In your class, there might be pupils speaking with different accents.<br />

By this, we also mean English words which are pronounced in a certain way.<br />

In groups<br />

Talk about the different voices in your class. How many different accents can you find? Are they<br />

all Scottish? English? Do some pupils come from another country and speak English with a very<br />

different accent? What accent does your teacher have? Do the class agree that there is a local accent in<br />

your town or village?<br />

Dialect<br />

Scots dialect words will be different from English. Repeat the same exercise as for accent and find<br />

out, in your class, if anybody uses dialect words. For example, in Programme 1, one girl talks about<br />

loons and quines instead of boys and girls.<br />

Writing<br />

Make a class list of dialect words that are used by your class.<br />

Homework<br />

A CTIVITY SHEET 2<br />

At home, maybe over two nights, list any dialect words you hear from family and friends.<br />

Go into local shops and cafes and listen to people’s voices. You might want to work in pairs for<br />

this task. List any words you think might be dialect.<br />

Class activity<br />

Discuss your findings. Were there<br />

any words you weren’t sure about? Did<br />

you know which words were different<br />

from Standard English? Did you<br />

discover new words you’d never heard<br />

before? Who spoke these words? Old<br />

people? Young people?<br />

© 2000 CHANNEL FOUR TELEVISION CORPORATION HAUD YER TONGUE

The Wild Geese<br />

‘Oh tell me what was on yer road, ye roarin norlan wind<br />

As ye cam blawin frae the land that’s niver frae my mind?<br />

My feet they trayvel England, but I’m deein for the north –’<br />

‘My man, I heard the siller tides rin up the Firth o Forth.’<br />

‘Aye, Wind, I ken them well eneuch, and fine they fa and rise,<br />

And fain I’d feel the creepin mist on yonder shore that lies,<br />

But tell me, ere ye passed them by, what saw ye on the way?’<br />

‘My man, I rocked the rovin gulls that sail abune the Tay.’<br />

‘But saw ye naethin, leein Wind, afore ye cam to Fife?<br />

There’s muckle lyin yont the Tay that’s mair to me nor life.’<br />

‘My man, I swept the Angus braes ye haena trod for years –’<br />

‘O Wind, forgie a hameless loon that canna see for tears!’<br />

‘And far abune the Angus straths I saw the wild geese flee,<br />

A lang, lang skein o beatin wings wi their heids towards the sea,<br />

And aye their cryin voices trailed ahint them on the air:’<br />

‘O Wind, hae maircy, haud yer whisht, for I daurna listen mair!’<br />

By Violet Jacob<br />

This poem is written in a mixture of Scots and English.<br />

The two languages are very alike (like cousins).<br />

How many people are speaking in the poem? Who are they?<br />

What is this poem about?<br />

Take a verse at a time and rewrite, in Scots or English, what<br />

you think is the ‘story’ of the poem. You should end up with<br />

four paragraphs.<br />

A CTIVITY SHEET 3<br />

HAUD YER TONGUE © 2000 CHANNEL FOUR TELEVISION CORPORATION<br />

11

PROGRAMME<br />

2<br />

12<br />

Coorse and Fine<br />

Programme outline<br />

This programme considers the difficulties which can arise<br />

for Scots speakers. We hear ‘Listen tae the Teacher’ by<br />

Nancy Nicolson and the writer talks about her<br />

experiences as a child. Adults and young people describe<br />

their own experiences of being corrected for speaking<br />

Scots. Alison Flett recites ‘Saltire’.<br />

We visit Orkney and hear pupils and adults talk about<br />

living on Orkney and speaking their local dialect.<br />

We go to the north-east and hear about the influence of<br />

American and English on Scots. The poem ‘It’s ile rigs<br />

brings the breid, man’ is recited.<br />

Student Barbara Ann Burnett sings ‘The Farmyards o<br />

Dalgety’.<br />

Dr Jimmy Begg from Ayrshire talks about going to help<br />

during the Lockerbie disaster, and we hear the poem<br />

‘Lockerbie Elegy’ by William Hershaw.<br />

Matthew Fitt recites ‘Coal Pits’. We discover that the<br />

Scots voice is capable of expressing a wide range of<br />

sentiments.<br />

Throughout the programme we hear about the<br />

importance of retaining your own culture and language.<br />

Learning outcomes<br />

Pupils will become aware of:<br />

● bilingualism and code-switching;<br />

● varieties of speech forms;<br />

● the fact that the Scots language is capable of<br />

describing deeply serious issues;<br />

● issues and attitudes surrounding the use of Scots.<br />

Leid leet<br />

dinna (don’t)<br />

hoose (house)<br />

richt (right)<br />

wrang (wrong)<br />

leid (language)<br />

gantin (desperate for)<br />

Doric (north-east Scots)<br />

thrawn (stubborn)<br />

drookit (soaked)<br />

kye (cattle)<br />

chappit tatties<br />

(mashed potatoes)<br />

breeks (trousers)<br />

yestreen (yesterday)<br />

flix (frighten)<br />

stammygaster (astonished)<br />

ginger (lemonade)<br />

syne (since)<br />

H A U D Y E R T O N G U E<br />

Before viewing<br />

The focus during the first part of this programme is<br />

on pupils being corrected or prevented from speaking<br />

Scots. Pupils might discuss their own experiences before<br />

hearing the views of others in the progamme. You might<br />

prefer to let pupils first hear others’ views before<br />

discussing their own, although this may depend on the<br />

number of Scots speakers in the class. A class with very<br />

few speakers may not have enough experience of<br />

language repression to discuss it fully at this stage.<br />

During viewing<br />

Using Fact File 1 ‘Dialect map’, pupils might locate<br />

the Orkney Islands, north-east Scotland, Lockerbie, and<br />

Ayr in south-west Scotland.<br />

After viewing<br />

Knowledge about language<br />

Discussion could take place around the issue of<br />

language repression. Older pupils might cope with this<br />

better. Pupils’ knowledge and experience will vary<br />

according to their own spoken language and where<br />

they live.<br />

Fact File 3 ‘Short history of the Scots language’ might<br />

be useful during discussion. It informs pupils that Scots<br />

was banned by the 1872 Scottish Education Act and<br />

encouraged in the 1990s. Examples are given in the<br />

programme of language repression. Billy Kay talks about<br />

the days when the belt was given for speaking Scots. He<br />

highlights the phenomenon of pupils being allowed to<br />

speak Scots in January when they study the work of<br />

Robert Burns, but not at other times. Dauvit Horsburgh<br />

of Aberdeen University says that some people think you<br />

are ‘nae sae bright’ if you speak Scots. He states that ‘you<br />

can’t get wrang words’.<br />

Pupils could be asked about their own experiences<br />

and reactions to these statements. Do they agree with the<br />

speakers? Have they ever been asked to alter their voices?<br />

Have the pupils ever been asked to speak ‘properly’?<br />

What does ‘speaking properly’ mean to pupils? Do they<br />

think that Scots could be ‘spoken properly’?<br />

Activity Sheet 4 ‘Speaking Scots’ suggests Listening,<br />

Talking and Writing tasks related to this area.

Further discussion<br />

Billy Kay says that ‘a language has to adapt to survive’.<br />

Pupils might discuss what this means. Has Scots or<br />

English adapted? Can languages adapt by borrowing?<br />

Some pupils might have noticed in Gaelic television<br />

programmes that technological words often stand out<br />

very clearly in a Gaelic sentence.<br />

Activity Sheet 1 ‘Words from other countries’ supplies<br />

pupils with examples of shared words from other<br />

countries.<br />

Like the girl from Banff who sings ‘The Farmyards o<br />

Dalgety’, do pupils think it is important to preserve<br />

culture, and sing traditional songs?<br />

The north-east oil-rig poem uses Scots in a very<br />

modern context. Would pupils like to have Scots words<br />

for twentieth-century things? Pupils could create new<br />

Scots words for modern objects and events. For example,<br />

people could now talk about ‘stravaigin the web’ instead<br />

of ‘surfing the web’.<br />

Writing<br />

A student says ‘gie fowk the facts’. In a survey, he<br />

discovered that about two million people speak Scots.<br />

Pupils might conduct a survey in their own area or try to<br />

find out how many people speak Scots in their street or<br />

town or village. They could choose appropriate questions<br />

for the survey. They might consider whether everyone<br />

will be sure which language they speak. Pupils might be<br />

prompted to discuss a first question such as ‘Do you<br />

know what “Scots language” means?’<br />

Talking and listening<br />

The doctor at the Lockerbie tragedy speaks Scots.<br />

Pupils might think of their own doctors, teachers, bank<br />

managers, ministers and generally anyone in a position of<br />

responsibility. How many of them speak Scots? Do pupils<br />

have viewpoints or preferences as to the ‘voice’ of people<br />

in these positions?<br />

Pupils should ‘be made aware ... of the ways in which<br />

accent and dialect can cause listeners to react differently’<br />

(5–14 English Language: Talking strand on audience<br />

awareness). This is often a controversial element of<br />

language study and fuller understanding of the pedigree<br />

of Scots that it is not slang or ‘bad’ English will need to<br />

be discussed at some point. Activity Sheet 2 ‘Accent and<br />

dialect’ (supplied with Programme 1) and Activity Sheet 8<br />

‘Slang and Scots’ (supplied with Programme 3) might be<br />

referred to here. Also, teachers are asked to ‘foster respect<br />

for and interest in each pupil’s mother tongue...’ You<br />

might use opportunities arising during these programmes<br />

to encourage tolerance and reduce linguistic and cultural<br />

prejudice. Cross-curricular possibilities may present<br />

themselves for personal and social development.<br />

Activity Sheets 5 and 6 ‘Listen tae the Teacher’ are<br />

supplied with follow-up questions to allow further<br />

exploration of language repression.<br />

Hert and heid<br />

‘The Lockerbie Elegy’ by William Hersaw and ‘Coal<br />

Pits’ by Matthew Fitt illustrate Dr Begg’s point that Scots<br />

is a good language for pathos. Teachers might discuss this<br />

with pupils. Do they usually associate Scots with serious<br />

or sad events? A discussion of stereotypes might take<br />

place. You might look at the images conveyed by wellknown<br />

films like Trainspotting or television programmes<br />

like Rab C. Nesbitt. Pupils might write their own poems<br />

on sad or serious issues. Some Scots could be included.<br />

Background information for<br />

teachers<br />

Scots, like any language, consists of more than just items<br />

of vocabulary. Apart from words which are clearly Scots,<br />

there is also a distinct grammatical system. Some of the<br />

more common examples of Scots which differentiate the<br />

language from English are:<br />

● the frequent use of the definite article and possessive<br />

pronoun, as in ‘I’ve got the flu and I’m away to my<br />

bed’ rather than ‘I’ve got flu and I’m going to bed’;<br />

● leaving out the ‘s’ in a plural, as in ‘He’s twa year auld’<br />

rather than ‘He’s two years old’;<br />

● the use of the past-tense form as opposed to the pastparticiple<br />

form, as in ‘The bell has went’ rather than<br />

‘The bell has gone’.<br />

Frequently, pupils speaking an urban form of Scots,<br />

rather than a rural dialect, continue to employ Scots<br />

grammar but little Scots vocabulary. For this reason,<br />

dialects such as Glaswegian are often mistaken<br />

for ‘bad’ English.<br />

Further examples can be<br />

found in some of the<br />

reference books suggested<br />

on the resources page.<br />

13

14<br />

Speaking Scots<br />

Listening and talking<br />

One of the boys on Westray talks about speaking on the telephone. He says that sometimes he<br />

changes his voice in case he is not understood in Scots. For example, when he’s ordering from a<br />

catalogue he changes his Shetland dialect into English. He called this ‘chantin’.<br />

Do you ever change your voice?<br />

Do you ever hear your parents changing their voices?<br />

In what circumstances does this happen?<br />

Working in pairs<br />

Make up a short phone conversation in Scots. Unless you’re used to writing in Scots, don’t worry<br />

about spelling; this activity is mainly for speaking in Scots.<br />

Choose two people who might speak to each other.<br />

They might be:<br />

● discussing another member of the family;<br />

● talking about a friend;<br />

● arranging a future visit;<br />

● gossiping about someone or something that has happened;<br />

● asking advice about something.<br />

If you are a Scots speaker, try this task without any dictionary help.<br />

You could use the leid leet (word list) or a dictionary if you need to.<br />

You could mix Scots and English together in the dialogue.<br />

Individually or with a partner<br />

Now try using Scots for a serious issue, like the people in the programme.<br />

You might:<br />

A CTIVITY SHEET 4<br />

● select a news item to present;<br />

● discuss an area of your school curriculum;<br />

● conduct a job interview in Scots;<br />

● give a short book or film review in Scots.<br />

Do you think Scots worked well for serious issues? Can you think of any places you’d like to<br />

have more Scots? For example, would you like to hear more Scots on television or read it in<br />

newspapers?<br />

© 2000 CHANNEL FOUR TELEVISION CORPORATION HAUD YER TONGUE

Listen tae the Teacher (1)<br />

He’s five year auld, he’s aff tae school,<br />

Fairmer’s bairn, wi a pencil an a rule,<br />

His teacher scoffs when he says ‘Hoose’,<br />

‘The word is “House”, you silly little goose.’<br />

He tells his Ma when he gets back<br />

He saw a ‘mouse’ in an auld cairt track.<br />

His faither lauchs fae the stack-yaird dyke,<br />

‘Yon’s a “Moose”, ye daft wee tyke.’<br />

Listen tae the teacher, dinna say dinna,<br />

Listen tae the teacher, dinna say hoose,<br />

Listen tae the teacher, ye canna say munna,<br />

Listen tae the teacher, ye munna say moose.<br />

He bit his lip and shut his mooth,<br />

Which wan could he trust for truth?<br />

He took his burden ower the hill<br />

Tae auld grey Geordie o the mill.<br />

An did they mock thee for thy tongue,<br />

Wi them sae auld and thoo sae young?<br />

They werena makkin a fuil o thee,<br />

Makkin a fuil o themsels, ye see.<br />

Listen tae the teacher ...<br />

Say ‘Hoose’ tae the faither, ‘House’ tae the teacher,<br />

‘Moose’ tae the fairmer, ‘Mouse’ tae the preacher,<br />

When ye’re young it’s weel for you<br />

Tae dae in Rome as Romans do,<br />

But when ye growe and ye are auld<br />

Ye needna dae as ye are tauld,<br />

Nor trim yer tongue tae please yon dame<br />

Scorns the language o her hame.<br />

Listen tae the teacher ...<br />

The teacher thought that he wis fine,<br />

He kept in step, he stayed in line,<br />

And faither said that he wis gran,<br />

Spak his ain tongue like a man.<br />

And when he grew and made his choice<br />

He chose his Scots, his native voice.<br />

And I charge ye tae dae likewise<br />

An spurn yon poor misguided cries.<br />

By Nancy Nicolson<br />

A CTIVITY SHEET 5<br />

HAUD YER TONGUE © 2000 CHANNEL FOUR TELEVISION CORPORATION<br />

15

16<br />

A CTIVITY SHEET 6<br />

Listen tae the Teacher (2)<br />

Read the words of ‘Listen tae the Teacher’ carefully. Answer the following questions.<br />

Wha’s the main character in the poem?<br />

Whit age is he?<br />

Whaur does he live?<br />

Whit is his faither’s job?<br />

Look at verse 1. Whit does it mean when it says the teacher ‘scoffs’?<br />

Why dae ye think she does this?<br />

Whit does his faither say?<br />

Why does the wee boy ‘bite his lip’ and ‘shut his mooth’?<br />

Wha does he gan tae fir help?<br />

Auld Geordie gies some advice. Whit is it?<br />

Whit does this mean – ‘Tae dae in Rome as Romans do’?<br />

Why did the writer say this in the song?<br />

When the boy grows up, whit does he dae?<br />

Dae ye agree wi his decision? Explain yer answer.<br />

Hoose an moose are rhyming words. Fin twa mair pairs of words that rhyme.<br />

Think aboot the wey you talk.<br />

Dae ye ayeweys talk the same? How and when does it change?<br />

Dae ye need tae be able tae talk in Scots and English?<br />

Can ye think o times when ye need tae ken English?<br />

© 2000 CHANNEL FOUR TELEVISION CORPORATION HAUD YER TONGUE

PROGRAMME<br />

3<br />

Programme outline<br />

This programme informs us about the literary pedigree of<br />

Scots. For centuries, writers have been writing in Scots,<br />

although there have been high spots and low spots. We<br />

visit St Makar’s cathedral in Aberdeen, where Alisdair<br />

Allan, a researcher, talks about John Barbour. We hear an<br />

extract from Barbour’s poem The Bruce. We discover that<br />

royalty spoke Scots in medieval times and that the Scots<br />

spoke many languages.<br />

In St Makar’s we also hear about Robert Henryson. Actor<br />

Tom Watson recites an extract from one of Henryson’s<br />

famous fables, ‘The Preaching of the Swallow’, in which<br />

the winter weather is described. Heather Reid announces<br />

the weather in Scots and Drew Clegg recites ‘Noah of<br />

Limekilns’.<br />

Billy Kay explains that the medieval times were known as<br />

the Golden Age of Literary Scots. In the eighteenth<br />

century a revival of Scots writing was led by Allan<br />

Ramsay, Robert Fergusson and Robert Burns. Rod<br />

Paterson sings ‘Willy Wastle’ by Robert Burns.<br />

Billy Hastie of Ayrshire talks about lallans (lowland<br />

Scots) and Robert Burns.<br />

We learn that poet Hugh MacDiarmid revived Scots<br />

writing in the twentieth century.<br />

We visit Hawick High School in the Borders, where<br />

pupils discuss their language and culture. Hawick and<br />

Gala jokes are told by Ian Landles.<br />

Learning outcomes<br />

Pupils will:<br />

● recognise that Scotland was a very European country<br />

in medieval times and many European languages were<br />

spoken there;<br />

● discover that Scots was a language with high status<br />

and spoken by royalty;<br />

● learn about Scots literature from the past;<br />

● be introduced to the Border Scots dialect;<br />

● raise their awareness of the diversity of viewpoints and<br />

issues surrounding the Scots language today.<br />

H A U D Y E R T O N G U E<br />

Language of Scottish<br />

Natioun<br />

Leid leet<br />

radgie (mad fit)<br />

gadgie (man)<br />

sudden pudden<br />

(instant whip)<br />

whup (beat)<br />

heelstergoudie (head over<br />

heels in a fluster)<br />

drookit (soaked)<br />

smirr<br />

(fine drizzle of rain)<br />

founert (frozen)<br />

Wather words<br />

thole (put up with)<br />

taigle (fight)<br />

heelstergoudie (mixed up)<br />

airts (arts)<br />

kintra (country)<br />

chitterin (freezing)<br />

gey het (very hot)<br />

sooth (south)<br />

Before viewing<br />

Fact File 4 ‘Scots writers time-line’ might be studied<br />

to help place the writers referred to in the programme.<br />

During viewing<br />

Pupils could note down the languages that Scots<br />

people spoke years ago. These include Gaelic, Latin,<br />

French, Danish, Norse, Flemish. Afterwards they might<br />

compare these with the languages taught in their own<br />

school or spoken in their own families. Discussion might<br />

take place about the importance of learning languages<br />

other than their own.<br />

After viewing<br />

lallans (lowland Scots)<br />

gowpin (staring at)<br />

mockit (filthy)<br />

whittrick (weasel)<br />

dinnae (don’t)<br />

hornygoloch (earwig)<br />

jeegered (exhausted)<br />

scabbyheidit (head with<br />

scabs on it)<br />

wabbit (tired)<br />

dreich (miserable)<br />

drookit (soaking)<br />

fine smirr (thin rain)<br />

stoatin (heavy rain)<br />

cloods (clouds)<br />

birlin (spinning)<br />

saft an douce<br />

(soft and gentle)<br />

Classes could compile a wall-chart of Scottish writers.<br />

The names of major writers throughout the centuries<br />

17

18<br />

could be charted. Sample verses from their work could<br />

appear in the display. The contrast between medieval and<br />

contemporary Scots could be highlighted. English<br />

translations could be added if desired.<br />

Pupils could create a short Scots poem of their own to<br />

add to the chart. The selected writers’ verses could provide<br />

a model. Pupils might write in their own dialect variation.<br />

Expressive arts<br />

Art: illustrations might accompany some lines of<br />

poetry as they did on the walls of St Makar’s cathedral.<br />

The model of Henryson, which was seen on the<br />

programme, might be copied, in his red robes and<br />

flowing white hair. Pupils might decorate initial letters of<br />

poems as in the illuminated manuscripts.<br />

Music: pupils might learn some of the songs heard in<br />

the programme.<br />

Listening and talking<br />

Pupils could practise reading some verses from the<br />

display and discuss the differences between early<br />

(medieval) and modern Scots writing. Tapes of medieval<br />

Scots are available from Scotsoun and ASLS (see resource<br />

page 32) if teachers would like to let pupils hear examples.<br />

Modern conflicts between Scotland and England<br />

might be discussed if teachers feel this is suitable. The<br />

new Scottish Parliament might be discussed. Do pupils<br />

think that, as in King James IV’s court, playwrights and<br />

poets should be encouraged to write in Scots?<br />

Reading<br />

Border ballads and narrative<br />

poetry might be read to<br />

complement the reivers stories.<br />

Writers from other<br />

historical periods could be<br />

read and their language and<br />

subject matter investigated.<br />

Writing<br />

The Border men swapped<br />

jokes. Pupils could compile a<br />

Scots joke book of their own.<br />

Using the supplied list of weather words, forecasts<br />

could be written in Scots, read out in class and illustrated<br />

for display. Dictionaries and a thesaurus will supplement<br />

the vocabulary from the programmes.<br />

Activity Sheet 7 ‘The medieval makars’ gives an<br />

extract from Barbour’s ‘The Bruce’. This activity may be<br />

suitable for more able pupils.<br />

Activity Sheet 8 ‘Slang and Scots’. The tasks suggested<br />

on this activity sheet seek to inform pupils of the<br />

difference between Scots and slang. Given that the status<br />

of the language has fallen since it was the official state<br />

language of Scotland, confusion exists between colloquial<br />

English and authentic Scots. This activity sheet prompts<br />

pupils to use a Scots dictionary and become more<br />

informed about the language.<br />

Research work<br />

Pupils could investigate which writers – past and<br />

present – wrote in the pupils’ local area. Contemporary<br />

writers could be invited into the school. The Scottish<br />

Book Trust Writers’ Register supplies names and addresses<br />

of writers in Scotland (for Scottish Book Trust details, see<br />

resource page 32).<br />

Environmental studies<br />

Related topics include:<br />

● The wars of independence referred to in Barbour’s<br />

‘The Bruce’. ‘The Declaration of Arbroath’ is in print<br />

and written in Scots, Gaelic and English. Teachers may<br />

wish to obtain copies of this for a relevant example of<br />

written formal Scots.<br />

● The Union of Crowns and Parliaments. These were<br />

referred to by Billy Kay and sung in ‘The King is ower<br />

the border gane, in London for tae dwell, an friens we<br />

maun wi England be since he bides there himsel’.<br />

Pupils might investigate the demise or suspension of<br />

the Scottish Parliament in 1707.<br />

● The Border reivers discussed by the men from Hawick<br />

and Gala (contact Tullie House in Carlisle for<br />

resources).<br />

Knowledge about language<br />

Pupils might discuss Hugh MacDiarmid’s statement<br />

that the Scots language has ‘names for nameless things’.<br />

What does this mean? The pupils could discuss whether<br />

they agree with this statement. Can they think of good<br />

English equivalents for ‘dreich’, ‘wabbit’, ‘forfochen’...<br />

Some Scots words have a very descriptive, rhythmic<br />

sound to them or are onomatopoeic. This could be<br />

discussed. For example, Tom Watson the actor says that<br />

the word ‘whittrick’, a fast weasel, is an excellent word<br />

because it sounds just like the way the animal moves.<br />

Pupils could write animal or weather poems using<br />

descriptive, onomatopoeaic language, then illustrate and<br />

display them. ‘Smirr’, ‘heelstergoudie’ and ‘soughin<br />

soond’ are examples of this.

factfile 4<br />

Scots writers<br />

time-line (a<br />

short selection)<br />

John Barbour ?1320–95<br />

Golden Age of Literary Scots<br />

Robert Henryson ?1425–1505<br />

William Dunbar ?1460–1520<br />

Gavin Douglas 1475–1522<br />

Sir David Lindsay 1490–1555<br />

Eighteenth-century revival<br />

Allan Ramsay 1685–1758<br />

Robert Fergusson 1750–96<br />

Robert Burns 1759–96<br />

H A U D Y E R T O N G U E<br />

Twentieth-century revival<br />

Violet Jacob 1863–1946<br />

Hugh MacDiarmid 1892–1978<br />

William Soutar 1898–1943<br />

Robert Garioch 1909–81<br />

J K Annand 1908–93<br />

Some modern Scots writers<br />

Tom Leonard<br />

Sheena Blackhall<br />

Liz Lochhead<br />

Janet Paisley<br />

Matthew Fitt<br />

Michael Marra<br />

Irvine Welsh<br />

William McIlvanney<br />

19

20<br />

The medieval makars<br />

In the programme we heard about the Scots writers of the medieval period. They were known as<br />

makars (makers) and were highly respected in Scotland. They were supported by King James IV of<br />

Scotland.<br />

Here is an example of their work – an extract from one of John Barbour’s poems. He was writing about<br />

a great Scots hero, Robert the Bruce, who fought against the English. He wanted Scotland to remain an<br />

independent nation. This poem was written about sixty years after the Battle of Bannockburn.<br />

The Bruce was written around 1375 and is the earliest long poem, an epic, to have survived<br />

in Scots.<br />

At that time, when the land was owned by rich lords and dynasties, this poem speaks for the ordinary<br />

folk of Scotland. It praises individual freedom above everything else.<br />

Writing<br />

Try to translate the poem into English or into modern Scots.<br />

Talking<br />

A CTIVITY SHEET 7<br />

A! fredome is a noble thing,<br />

Fredome mays man to haiff liking, makes; choice<br />

Fredome all solace to man giffis,<br />

He leyvs at es that frely levys. ease<br />

A noble hart may haiff nane es<br />

Na ellys nocht that may him ples<br />

Gyff fredome failye, for fre liking fail; free choice<br />

Is yharnyt our all other thing. yearned for over<br />

from John Barbour’s The Bruce<br />

Discuss in class what you think this piece of writing is saying. Do you agree? Is freedom more<br />

important than anything else or would you rather be very rich but not free?<br />

You might want to talk about the Royal Family, film stars, football players or any other famous<br />

people. Are they free? What sort of restrictions do you think they have?<br />

© 2000 CHANNEL FOUR TELEVISION CORPORATION HAUD YER TONGUE

Slang and Scots<br />

Look at the chart below.<br />

We are going to use this to help separate Scots words from slang words.<br />

Sometimes people find it difficult to tell the difference between Scots and slang.<br />

Most Scots words have been used for hundreds of years. But slang words are often very recent.<br />

Usually, they are also spoken by people from other countries.<br />

You will need a Scots dictionary for this exercise.<br />

In the ‘word or phrase’ column, list a few words or phrases that you use or hear in Scotland. Three<br />

examples are started for you.<br />

word or phrase Scots slang<br />

ken<br />

ay<br />

okay<br />

Tick whether you think these words are Scots or slang.<br />

Now check your words and phrases in the Scots dictionary.<br />

Are they listed as Scots?<br />

Compare results throughout the class.<br />

Were you right about most of your choices?<br />

You might now make a new set of columns with Scots and slang under the correct<br />

headings. There may still be some words you haven’t found out about.<br />

Did the results surprise you? If so, why?<br />

Do you feel any different about Scots now you know it isn’t slang?<br />

Homework<br />

At home, you might try the above exercise on members of your family.<br />

In class, compare results. Did most families know which words were Scots?<br />

A CTIVITY SHEET 8<br />

HAUD YER TONGUE © 2000 CHANNEL FOUR TELEVISION CORPORATION<br />

21

PROGRAMME<br />

4<br />

22<br />

Ti Be <strong>Yer</strong>sel<br />

Programme outline<br />

In this programme Scots is used in contemporary<br />

writing. Mary McIntosh reads an alphabet game in Scots.<br />

Janet Paisley recites the poem ‘Skelp’. Sheena Blackhall<br />

talks about Scots words and recites her poem ‘The<br />

Check-Oot Quine’s Lament’ while pupils from Dunblane<br />

Primary School are shown re-labelling supermarket goods<br />

in Scots.<br />

The Proclaimers sing ‘Throw the R Away’ and discuss<br />

their experiences of being a Scots pop group. Matthew<br />

Fitt recites a poem about the Proclaimers while criticising<br />

stereotypical attitudes to Scots.<br />

We visit Portobello High School, where pupils and<br />

teacher Alan Keay talk about the school Scots magazine<br />

Porty Blethers. Pupils deliver a rap called ‘D & C’s Guide<br />

to Scotland’.<br />

Researcher Alisdair Allan explains how he sat all his<br />

degree exams in Scots.<br />

We go to Ayrshire, where Billy Kay and pupils from Park<br />

Primary School, Stranraer visit the cave of Sawney Bean,<br />

a cannibal from the past. A pupil recites ‘The Ballad of<br />

Sawney Bean’ by Lionel McLelland.<br />

Learning outcomes<br />

Pupils should:<br />

● practise using a Scots dictionary and learn about<br />

glossaries;<br />

● learn that, at the moment, the Scots language, unlike<br />

English, is not standardised;<br />

● consider the use of Scots in modern contexts;<br />

● learn more about modern Scots literature;<br />

● appreciate that extra Scots vocabulary enhances rather<br />

than restricts their language store.<br />

H A U D Y E R T O N G U E<br />

Leid leet<br />

foonert (freezing)<br />

trauchled (exhausted)<br />

forfochen (tired)<br />

skite (swipe)<br />

gansie (jumper)<br />

scunnert (annoyed)<br />

pieces (sandwiches)<br />

tatties (potatoes)<br />

bubblyjock (turkey)<br />

clabbiedoos (mussels)<br />

haddies (haddock)<br />

mingin (filthy)<br />

cannae (cannot)<br />

glaikit (stupid)<br />

Before viewing<br />

Teachers might prompt pupils to list all the Scottish<br />

writers they have read or heard of. Most pupils will have<br />

heard of, or studied, at least the work of Robert Burns.<br />

During viewing<br />

Pupils could note down any names of Scots writers<br />

that are mentioned in the programme. If possible, they<br />

could add the names of any songs or poems.<br />

After viewing<br />

Listening and talking<br />

barrie (brilliant)<br />

deek (a look)<br />

schule (school)<br />

pecht oot<br />

(out of breath)<br />

wabbit (tired)<br />

doitit (mixed up)<br />

scabbyheidit<br />

(a head with scabs)<br />

aul claes an parridge (old<br />

clothes and porridge)<br />

midden (a mess)<br />

Pupils could discuss the list of writers compiled<br />

before and during the programme. Do they now know<br />

the names and works of some other writers?<br />

Discuss whether pupils would like, as suggested by<br />

the pupil from Portobello High School, to sit exams in<br />

Scots. Should there be a choice of English or Scots to<br />

study? Discuss the Scots opportunities in Higher Still for<br />

studying Scots literature and language and for writing in<br />

Scots.<br />

Would pupils like to see supermarkets labelling in<br />

Scots as the children at Dunblane Primary School did?<br />

In the programme people spoke about their language<br />

being diminished if they lost their Scots vocabulary.

Pupils could discuss this point. Do they think it would<br />

mean a lessening of their self-expression if they couldn’t<br />

use Scots words? Will they encourage their own children<br />

to speak Scots in years to come?<br />

Reading<br />

After reading ‘The Ballad of Sawney Bean’ by Lionel<br />

McClelland (Activity Sheet 9), pupils can analyse the<br />

poem’s content and form. The poem describes the Bean<br />

family, their activities and their capture. Comprehension<br />

questions could be asked. Pupils could be introduced to<br />

other new Scots literature. Prose might be introduced (see<br />

resource page 32).<br />

Knowledge about language<br />

Pupils could analyse the poem’s technical construction<br />

and identify its rhythms and rhyme patterns. Crossreference<br />

might be made to any other ballads that may<br />

have been studied, for example Border ballads (from<br />

Programme 3) or the ballad of ‘Sir Patrick Spens’.<br />

Writing<br />

Pupils could compile an alphabet of Scots words as in<br />

the game played by the pupils in the programme. This<br />

might be similar to the game ‘The Minister’s Cat’.<br />

Pupils might write a rap in Scots, choosing modern<br />

themes and issues.<br />

Classes could compile a newspaper in Scots. Ask them<br />

to study some magazines or newspapers and list contents<br />

and ideas. You might include some of the following:<br />

horoscope, jokes, letters, articles, cartoons (speech<br />

bubbles in Scots), editorial comment about Scots issues,<br />

sports results, photographs and illustrations with<br />

captions, film, television and book reviews, weather<br />

reports, crosswords. The TV page might have ‘Hame an<br />

Awa’, ‘Neebours’, ‘Polis Academy Twa’. Different tasks<br />

might be allocated according to levels of ability. The use<br />

of Scots for functional writing might be encouraged<br />

through a newspaper report or article.<br />

Pupils may write a local legend set in their home<br />

town or village, or rewrite, in Scots, a well-known<br />

fairytale. Rewriting a well-known story is a good<br />

introduction to writing in Scots for some pupils. Those<br />

with limited ability in creative writing will be able to<br />

concentrate on their Scots vocabulary rather than<br />

inventing a new story. Frequently, these pupils, for<br />

sociological reasons, are the pupils whose Scots<br />

vocabulary is familiar and rich.<br />

Pupils could be encouraged to think of a local place they<br />

know well. They might already know a local legend, but,<br />

if not, can use the familiar landscape to prompt the<br />

imagination to create one. Often, local vocabulary is the<br />

pupils’ daily speech and a wide vocabulary store emerges.<br />

Using Activity Sheet 10 ‘Scots saws or sayings’, pupils<br />

are encouraged to recognise an important element of<br />

Scottish speech: idiomatic use of language. The use of<br />

idiomatic phrases, especially in dialogue, lends an<br />

authenticity to short stories or drama. Pupils could write<br />

a short dialogue between two Scots characters who<br />

employ idioms in their speech. Humorous sketches are<br />

particularly suitable for this.<br />

In the programme, the pop band The Proclaimers sing<br />

a pop song. Pupils could try writing their own Scots pop<br />

song. It could be set locally or it could include Scottish<br />

names. The rap form might lend itself well to this.<br />

Expressive arts<br />

Art: as suggested in Activity Sheet 10 ‘Scots saws or<br />

sayings’, illustrations could be made of sayings. ‘The<br />

Ballad of Sawney Bean’ might be illustrated. Each verse<br />

tells a different part of the story and a storyboard might<br />

be suitable for less able pupils, with short captions written<br />

in Scots underneath pictures. Words can be selected from<br />

the ballad to help supply vocabulary, and you might<br />

provide a bank of phrases for pupils to select from.<br />

Music: write and sing a Scots song or ballad. ‘The<br />

Ballad of Sawney Bean’ is available on Dunkeld Records<br />

sung by Black-Eyed Biddy.<br />

23

24<br />

factfile 5<br />

Scots spelling<br />

People spell Scots words in different ways.<br />

In English, there is now an agreed way to<br />

spell and it can be found in English<br />

dictionaries. But, at one time, English<br />

words also had many spellings. In<br />

Shakespeare’s plays you can find the same<br />

word spelt in different ways.<br />

In 1755 Samuel Johnson compiled a<br />

dictionary. He lived near London and<br />

decided to write words down in the way he<br />

spoke. Gradually Standard English became<br />

an agreed way to spell all over England –<br />

even though folk in different parts of the<br />

country spoke different dialects of English.<br />

At one time, the King of Scotland wrote in<br />

Scots, and in 1424 an Act of Parliament<br />

made Scots the official language of<br />

Parliament. Playwrights and poets were<br />

employed at Court to write in Scots.<br />

Scots dictionaries give a choice of spelling,<br />

and sometimes the way words are spelt<br />

changes depending on which part of<br />

Scotland you come from. Most of the<br />

different dialects are included in the<br />

dictionary.<br />

H A U D Y E R T O N G U E<br />

the ae<br />

wey<br />

Here is an extract from Chambers English-<br />

Scots school dictionary which shows how<br />

the different dialects are included:<br />

one – numeral, pronoun ane, yin<br />

CENTRAL, SOUTH, wan, WEST,<br />

SOUTHWEST, ULSTER; (mainly<br />

emphatic) ae: ‘the ae wey’, yae CENTRAL,<br />

SOUTH; (in children’s rhymes) eentie,<br />

eendie<br />

one another – ither, ilk ither<br />

oneself – yersel<br />

For discussion:<br />

In how many ways can we say the<br />

number one in Scotland?<br />

Which do you use?<br />

Would you like Scots to have standard<br />

spellings, like English?

The Ballad of Sawney Bean<br />

Go ye not by Gallowa,<br />

Come bide a while, my freen,<br />

I’ll tell ye o the dangers there –<br />

Beware o Sawney Bean.<br />

There’s naebody kens that he bides there<br />

For his face is seldom seen,<br />

But tae meet his eye is tae meet yer fate<br />

At the hands o Sawney Bean.<br />

For Sawney he has taen a wife<br />

And he’s hungry bairns tae wean,<br />

And he’s raised them up on the flesh o men<br />

In the cave o Sawney Bean.<br />

And Sawney has been well endowed<br />

Wi dochters young and lean<br />

And they aa hae taen their faither’s seed<br />

In the cave o Sawney Bean.<br />

An Sawney’s sons are young an strong<br />

And their blades are sherp and keen<br />

Tae spill the blood o travellers<br />

Wha meet wi Sawney Bean.<br />

So if ye ride fae there tae here<br />

Be ye wary in between<br />

Lest they catch yer horse and spill yer blood<br />

In the cave o Sawney Bean<br />

But fear ye not, oor Captain rides<br />

On an errand o the Queen<br />

And he carries the writ o fire and sword<br />

For the head o Sawney Bean.<br />

They’ve hung them high in Edinburgh toon<br />

An likewise aa their kin<br />

An the wind blaws cauld on aa their banes<br />

An tae hell they aa hae gaen.<br />

By Lionel McClelland<br />

A CTIVITY SHEET 9<br />

HAUD YER TONGUE © 2000 CHANNEL FOUR TELEVISION CORPORATION<br />

25

26<br />

Scots saws or sayings<br />

In the programme Billy Kay visits Sawney Bean’s cave. When the adventure is past he says ‘Oh weel,<br />

back tae aul claes an parridge’. What does he mean? The Scots language contains many well-known<br />

sayings and idioms. In Scots these are often called Scots saws or sayings.<br />

Group discussion<br />

Here are some more sayings. Try to work out what they mean.<br />

tae pit somebody’s gas at a peep<br />

whit’s fir ye’ll no gan by ye<br />

gan doon the brae<br />

he’s no backwards aboot comin forrit<br />

Writing in groups<br />

Can you add any more to this list?<br />

In your groups write down other sayings that you know, then test them out on the rest of the class.<br />

Did the other groups have any you didn’t have?<br />

Individual work<br />

Collect some more Scots saws or sayings at<br />

home. Sometimes old people know lots of them.<br />

Bring them back to school and share them<br />

with the class.<br />

Writing<br />

A CTIVITY SHEET 10<br />

On your own, or with the rest of the class,<br />

gather all your sayings together into a booklet.<br />

You might illustrate it with drawings<br />

connected with the saying. You could each<br />

draw a picture, with a caption underneath.<br />

The next time you’re writing a story, you might decide to use some<br />

sayings in it when somebody is speaking.<br />

© 2000 CHANNEL FOUR TELEVISION CORPORATION HAUD YER TONGUE

PROGRAMME<br />

5<br />

The Future Oors?<br />

Programme outline<br />

In this programme writers, politicians and actors talk<br />

about the future of the Scots language and its status in<br />

society.<br />

The voice of the new Scottish Parliament is discussed<br />

and views expressed that Scots, Gaelic and English<br />

should be included.<br />

Reinforcement is given to statements in earlier<br />

programmes that Scottish literature has always been<br />

about the working classes as well as royalty and rich<br />

folk. A poem, ‘Delinquent Sang’, from Sheena Blackhall<br />

illustrates this point.<br />

Demonstrations, from pupils and university students, of<br />

Scots language on the web and on CD-ROM show that<br />

Scots is part of modern technological society.<br />

Foreign students learning Scots are interviewed at<br />

Aberdeen University and the Aberdeen University Scots<br />

Leid Quorum explains why it was formed and what it<br />

does. The programme visits Dundee, a strong dialect<br />

area, where singer Sheena Wellington and a women’s<br />

choir sing a traditional working song. Michael Marra<br />

from Dundee sings ‘Hermless’ and explains why he<br />

enjoys using Scots words in his writing. A modern<br />

version of ‘Cinderella’ is recited by Donna McCracken.<br />

Actors, teachers and business people give their views on<br />

the importance of Scots in modern society and on<br />

retaining individuality in a globalised world.<br />

We hear ‘The Bonnie Broukit Bairn’ by Hugh<br />

MacDiarmid.<br />

Billy Kay explains that the pupils themselves will make<br />

decisions about the future of the Scots language.<br />

Learning outcomes<br />

Pupils will learn that:<br />

● many Scots speakers, including prominent people in<br />

Scottish public life, are concerned to retain their<br />

Scots voice;<br />

● a person’s own culture and language are crucial to<br />

maintaining a sense of identity in modern society;<br />

● Scots literature is wide-ranging in topics and target<br />

audiences;<br />

H A U D Y E R T O N G U E<br />

● Scots is available on the Internet and CD-ROM, like<br />

other twentieth-century languages;<br />

● it is the pupils themselves who will make decisions in<br />

the future.<br />

Leid leet<br />

haverin<br />

(talking rubbish)<br />

coup (a dump)<br />

scunnert (disgusted)<br />

thole (put up with)<br />

thrive (grow)<br />

stushie (a fuss)<br />

puckle<br />

(a small amount)<br />

dwam (a dream)<br />

greetin (crying)<br />

Before viewing<br />

Pupils might be encouraged to discuss their thoughts<br />

on the status of Scots in modern society. Having seen<br />

four programmes by now, they might have formulated<br />

their own views about the language, and in this last<br />

programme they will hear the views of others.<br />

During viewing<br />

Pupils might note any views expressed about the value<br />

of speaking their own language. If possible, pupils should<br />

identify the speaker and his or her occupation. For<br />

example, pupils could write down whether the speaker is<br />

an actor, a politician, or a pupil.<br />

After viewing<br />

Listening and talking<br />

hackit<br />

(horrible-looking)<br />

bummers (machines)<br />

walin (noise)<br />

almichty (almighty)<br />

glaikit (stupid)<br />

bowfin (smelly)<br />

dicht (wipe)<br />

breenge (rush)<br />

yersel (yourself)<br />

Pupils could discuss the place of Scots language in<br />

society and in their own lives. By the fifth programme,<br />

they should have formed their own viewpoint on this<br />

issue. It will, of course, vary according to individual<br />

circumstances – own speech, background, knowledge<br />

gained throughout the programmes. Pupils’ notes taken<br />

during viewing can be referred to. Discussion could take<br />

place on issues prompted by the programme, such as what<br />

the voice of the Scottish Parliament should be. A class<br />

27

28<br />

debate could be organised, with a motion of ‘Scots should<br />

be spoken in a Scottish Parliament’, with pupils chosen to<br />

speak for and against.<br />

Discussion<br />

In the programme, Billy Kay quotes Hugh<br />

MacDiarmid:<br />

‘Tae be yersel an tae mak that worth bein,<br />

Nae harder job tae mortals has been gien’<br />

What do pupils think this means?<br />

Billy also says that ‘it’s even harder tae be yersel if folk<br />

want tae deny ye the way ye speak’. Do pupils think this<br />

is true? Billy also says ‘Celebrate your culture and it’s a lot<br />

easier to accept other people’s tae’. Ask pupils to define<br />

their culture. What does it mean to them? A discussion of<br />

prejudice might also take place. Do pupils accept other<br />

people’s culture, habits, language?<br />

At the end of the programme, Billy Kay says that the<br />

pupils watching the programme are the decision makers<br />

of the future. Pupils might be prompted to discuss what<br />

sort of decisions they will need to take about language<br />

and culture. ‘May aw yer decisions be the richt yins’ is the<br />

last comment of the series. What does this mean to<br />

pupils? You might suggest some linguistic areas for pupils<br />

to discuss making decisions about. For example, the use<br />

of Scots in the media, including newspapers and<br />

television, films, books and comics, and the exam system.<br />

Extra-curricular activities<br />

Some schools might consider forming a group like the<br />

Aberdeen Scots Leid Quorum (ASLQ). It could be an<br />

after-school or dinner-time group. The Saltire Society<br />

encourages such groups for wide cultural themes<br />

(see page 32 for address).<br />

Writing<br />

Pupils could write a weaving or working poem or<br />

song. As demonstrated by the Dundee weaving song,<br />

there is always a strong rhythmic movement to these<br />

songs. You might introduce other waulkin/workin songs<br />