PATHways Newsletter.pub - NAMI

PATHways Newsletter.pub - NAMI

PATHways Newsletter.pub - NAMI

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

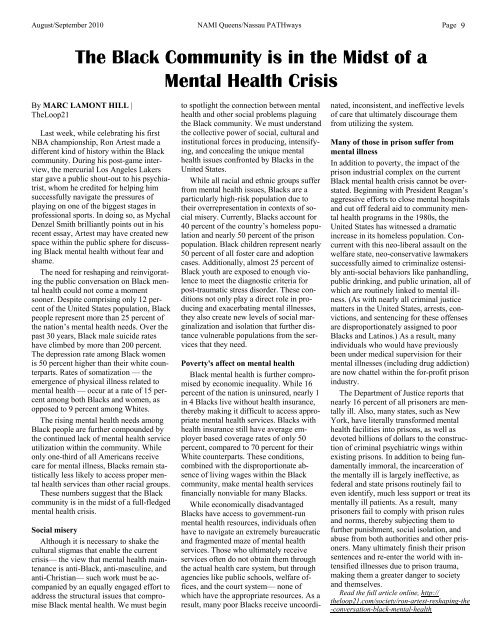

August/September 2010 <strong>NAMI</strong> Queens/Nassau <strong>PATHways</strong> Page 9<br />

The Black Community is in the Midst of a<br />

Mental Health Crisis<br />

By MARC LAMONT HILL |<br />

TheLoop21<br />

Last week, while celebrating his first<br />

NBA championship, Ron Artest made a<br />

different kind of history within the Black<br />

community. During his post-game interview,<br />

the mercurial Los Angeles Lakers<br />

star gave a <strong>pub</strong>lic shout-out to his psychiatrist,<br />

whom he credited for helping him<br />

successfully navigate the pressures of<br />

playing on one of the biggest stages in<br />

professional sports. In doing so, as Mychal<br />

Denzel Smith brilliantly points out in his<br />

recent essay, Artest may have created new<br />

space within the <strong>pub</strong>lic sphere for discussing<br />

Black mental health without fear and<br />

shame.<br />

The need for reshaping and reinvigorating<br />

the <strong>pub</strong>lic conversation on Black mental<br />

health could not come a moment<br />

sooner. Despite comprising only 12 percent<br />

of the United States population, Black<br />

people represent more than 25 percent of<br />

the nation’s mental health needs. Over the<br />

past 30 years, Black male suicide rates<br />

have climbed by more than 200 percent.<br />

The depression rate among Black women<br />

is 50 percent higher than their white counterparts.<br />

Rates of somatization — the<br />

emergence of physical illness related to<br />

mental health — occur at a rate of 15 percent<br />

among both Blacks and women, as<br />

opposed to 9 percent among Whites.<br />

The rising mental health needs among<br />

Black people are further compounded by<br />

the continued lack of mental health service<br />

utilization within the community. While<br />

only one-third of all Americans receive<br />

care for mental illness, Blacks remain statistically<br />

less likely to access proper mental<br />

health services than other racial groups.<br />

These numbers suggest that the Black<br />

community is in the midst of a full-fledged<br />

mental health crisis.<br />

Social misery<br />

Although it is necessary to shake the<br />

cultural stigmas that enable the current<br />

crisis— the view that mental health maintenance<br />

is anti-Black, anti-masculine, and<br />

anti-Christian— such work must be accompanied<br />

by an equally engaged effort to<br />

address the structural issues that compromise<br />

Black mental health. We must begin<br />

to spotlight the connection between mental<br />

health and other social problems plaguing<br />

the Black community. We must understand<br />

the collective power of social, cultural and<br />

institutional forces in producing, intensifying,<br />

and concealing the unique mental<br />

health issues confronted by Blacks in the<br />

United States.<br />

While all racial and ethnic groups suffer<br />

from mental health issues, Blacks are a<br />

particularly high-risk population due to<br />

their overrepresentation in contexts of social<br />

misery. Currently, Blacks account for<br />

40 percent of the country’s homeless population<br />

and nearly 50 percent of the prison<br />

population. Black children represent nearly<br />

50 percent of all foster care and adoption<br />

cases. Additionally, almost 25 percent of<br />

Black youth are exposed to enough violence<br />

to meet the diagnostic criteria for<br />

post-traumatic stress disorder. These conditions<br />

not only play a direct role in producing<br />

and exacerbating mental illnesses,<br />

they also create new levels of social marginalization<br />

and isolation that further distance<br />

vulnerable populations from the services<br />

that they need.<br />

Poverty's affect on mental health<br />

Black mental health is further compromised<br />

by economic inequality. While 16<br />

percent of the nation is uninsured, nearly 1<br />

in 4 Blacks live without health insurance,<br />

thereby making it difficult to access appropriate<br />

mental health services. Blacks with<br />

health insurance still have average employer<br />

based coverage rates of only 50<br />

percent, compared to 70 percent for their<br />

White counterparts. These conditions,<br />

combined with the disproportionate absence<br />

of living wages within the Black<br />

community, make mental health services<br />

financially nonviable for many Blacks.<br />

While economically disadvantaged<br />

Blacks have access to government-run<br />

mental health resources, individuals often<br />

have to navigate an extremely bureaucratic<br />

and fragmented maze of mental health<br />

services. Those who ultimately receive<br />

services often do not obtain them through<br />

the actual health care system, but through<br />

agencies like <strong>pub</strong>lic schools, welfare offices,<br />

and the court system— none of<br />

which have the appropriate resources. As a<br />

result, many poor Blacks receive uncoordi-<br />

nated, inconsistent, and ineffective levels<br />

of care that ultimately discourage them<br />

from utilizing the system.<br />

Many of those in prison suffer from<br />

mental illness<br />

In addition to poverty, the impact of the<br />

prison industrial complex on the current<br />

Black mental health crisis cannot be overstated.<br />

Beginning with President Reagan’s<br />

aggressive efforts to close mental hospitals<br />

and cut off federal aid to community mental<br />

health programs in the 1980s, the<br />

United States has witnessed a dramatic<br />

increase in its homeless population. Concurrent<br />

with this neo-liberal assault on the<br />

welfare state, neo-conservative lawmakers<br />

successfully aimed to criminalize ostensibly<br />

anti-social behaviors like panhandling,<br />

<strong>pub</strong>lic drinking, and <strong>pub</strong>lic urination, all of<br />

which are routinely linked to mental illness.<br />

(As with nearly all criminal justice<br />

matters in the United States, arrests, convictions,<br />

and sentencing for these offenses<br />

are disproportionately assigned to poor<br />

Blacks and Latinos.) As a result, many<br />

individuals who would have previously<br />

been under medical supervision for their<br />

mental illnesses (including drug addiction)<br />

are now chattel within the for-profit prison<br />

industry.<br />

The Department of Justice reports that<br />

nearly 16 percent of all prisoners are mentally<br />

ill. Also, many states, such as New<br />

York, have literally transformed mental<br />

health facilities into prisons, as well as<br />

devoted billions of dollars to the construction<br />

of criminal psychiatric wings within<br />

existing prisons. In addition to being fundamentally<br />

immoral, the incarceration of<br />

the mentally ill is largely ineffective, as<br />

federal and state prisons routinely fail to<br />

even identify, much less support or treat its<br />

mentally ill patients. As a result, many<br />

prisoners fail to comply with prison rules<br />

and norms, thereby subjecting them to<br />

further punishment, social isolation, and<br />

abuse from both authorities and other prisoners.<br />

Many ultimately finish their prison<br />

sentences and re-enter the world with intensified<br />

illnesses due to prison trauma,<br />

making them a greater danger to society<br />

and themselves.<br />

Read the full article online, http://<br />

theloop21.com/society/ron-artest-reshaping-the<br />

-conversation-black-mental-health