Wildlife of Lao PDR: 1999 Status Report - IUCN

Wildlife of Lao PDR: 1999 Status Report - IUCN

Wildlife of Lao PDR: 1999 Status Report - IUCN

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>IUCN</strong> - The World Conservation Union<br />

15 Fa Ngum Road PO Box 4340<br />

Vientiane <strong>Lao</strong> <strong>PDR</strong><br />

<strong>IUCN</strong><br />

The World Conservation Union<br />

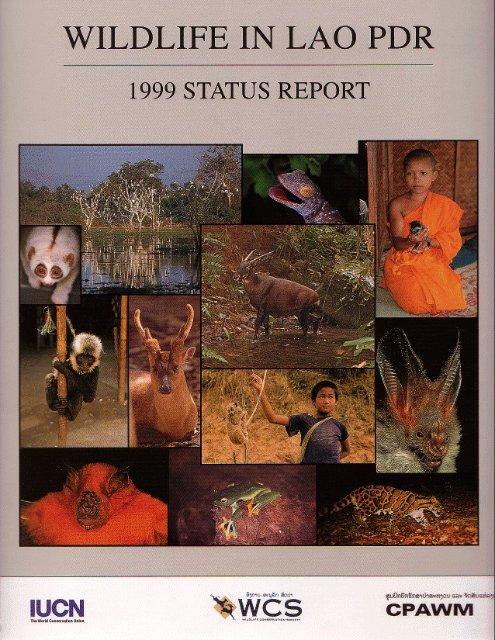

WILDLIFE IN LAO <strong>PDR</strong><br />

<strong>1999</strong> STATUS REPORT<br />

Compiled by<br />

J. W. Duckworth, R. E. Salter and K. Khounboline<br />

<strong>Wildlife</strong> Conservation Society<br />

PO Box 6712<br />

Vientiane <strong>Lao</strong> <strong>PDR</strong><br />

Centre for Protected Areas and<br />

Watershed Management<br />

Department <strong>of</strong> Forestry<br />

PO Box 2932<br />

Vientiane <strong>Lao</strong> <strong>PDR</strong><br />

Centre for Protected Areas and<br />

Watershed Management<br />

i

Published by: <strong>IUCN</strong>, Vientiane, <strong>Lao</strong> <strong>PDR</strong><br />

Reproduction: Reproduction <strong>of</strong> material from this document<br />

for education or other non-commercial purposes<br />

is authorised without the prior permission<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>IUCN</strong>, provided the source is acknowledged.<br />

Citation: Duckworth, J. W., Salter, R. E. and<br />

Khounboline, K. (compilers) <strong>1999</strong>. <strong>Wildlife</strong><br />

in <strong>Lao</strong> <strong>PDR</strong>: <strong>1999</strong> <strong>Status</strong> <strong>Report</strong>. Vientiane:<br />

<strong>IUCN</strong>-The World Conservation Union / Wild<br />

life Conservation Society / Centre for Protected<br />

Areas and Watershed Management.<br />

First edition: 1993<br />

Layout by: SuperNatural Productions ~ Bangkok<br />

Printed by: Samsaen Printing ~ Bangkok<br />

Available<br />

from: <strong>IUCN</strong><br />

PO Box 4340<br />

Vientiane<br />

<strong>Lao</strong> <strong>PDR</strong><br />

ii<br />

Telephone: + 821 21 216401<br />

Fax: ++ 821 21 216127<br />

Email: <br />

The findings, interpretations, conclusions and recommendations<br />

expressed in this document represent those <strong>of</strong> the compilers<br />

and do not imply the endorsement <strong>of</strong> <strong>IUCN</strong>, WCS or<br />

CPAWM. The designation <strong>of</strong> geographical entities in this<br />

document, and the presentation <strong>of</strong> the material, do not imply<br />

the expression <strong>of</strong> any opinion on the part <strong>of</strong> <strong>IUCN</strong>, WCS or<br />

CPAWM concerning the legal status <strong>of</strong> any country, territory,<br />

or area, or its authorities, or concerning the delimitation<br />

<strong>of</strong> its frontiers or boundaries.<br />

ISBN: 2 - 8317 - 0483 - 9<br />

Contact addresses <strong>of</strong> compilers and authors:<br />

Peter Davidson (WCS <strong>Lao</strong> Program), Woodspring,<br />

Bowcombe Creek, Kingsbridge, Devon TQ7 2DJ, U.K.<br />

William Duckworth (<strong>IUCN</strong> <strong>Lao</strong> <strong>PDR</strong>), East Redham Farm,<br />

Pilning, Bristol BS35 4JG, U.K.<br />

Charles Francis (WCS <strong>Lao</strong> Program), Bird Studies Canada,<br />

P.O. Box 160, Port Rowan, Ontario, N0E 1M0, Canada.<br />

Antonio Guillén (WCS <strong>Lao</strong> Program), Department <strong>of</strong><br />

Biology, University <strong>of</strong> Missouri - St Louis, 8001 Natural<br />

Bridge Road, Saint Louis, Missouri 63121, U.S.A.<br />

Khamkhoun Khounboline (CPAWM), Centre for Protected<br />

Areas and Watershed Management, PO Box 2932,<br />

Vientiane, <strong>Lao</strong> <strong>PDR</strong>.<br />

William Robichaud (WCS <strong>Lao</strong> Program), WCS, PO Box<br />

6712, Vientiane, <strong>Lao</strong> <strong>PDR</strong><br />

Mark Robinson (WWF Thailand), 11 Newton Road, Little<br />

Shelford, Cambridgeshire CB2 5HL, U.K.<br />

Richard Salter (<strong>IUCN</strong> <strong>Lao</strong> <strong>PDR</strong>), c/o <strong>IUCN</strong>, PO Box 4340,<br />

Vientiane, <strong>Lao</strong> <strong>PDR</strong>.<br />

Bryan Stuart (WCS <strong>Lao</strong> Program), Department <strong>of</strong> Zoology,<br />

North Carolina State University, Box 7617, Raleigh, NC<br />

27695-7617, U.S.A.<br />

Rob Timmins (WCS <strong>Lao</strong> Program), 25 Cradley Road,<br />

Cradley Heath, Warley, West Midlands B64 6AG, U.K.<br />

Funded by: German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ)

PREFACE<br />

In 1993 <strong>IUCN</strong>, in collaboration with the Department <strong>of</strong> Forestry’s Centre for Protected Areas and Watershed Management,<br />

published the first status report <strong>of</strong> wildlife in <strong>Lao</strong> <strong>PDR</strong>. Previous information was available through the reports <strong>of</strong><br />

European collectors and hunters dating back to the 1890s through to the 1960s. Over the past six years, a wealth <strong>of</strong> additional<br />

information on the wildlife <strong>of</strong> <strong>Lao</strong> <strong>PDR</strong> has been gathered as a result <strong>of</strong> various surveys that have been undertaken as well as<br />

enhanced knowledge <strong>of</strong> species distribution and the factors that influence range, population and conservation status <strong>of</strong> each<br />

species within the country. It is therefore timely and necessary that the earlier report has now been updated to reflect this<br />

increased knowledge base. The <strong>1999</strong> <strong>Status</strong> <strong>Report</strong> is a result <strong>of</strong> collaboration between the Centre for Protected Areas and<br />

Watershed Management, <strong>IUCN</strong> - The World Conservation Union, and The <strong>Wildlife</strong> Conservation Society, supported by<br />

funding from the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ).<br />

<strong>Lao</strong> <strong>PDR</strong> still has a rich wildlife heritage, with wildlife populations and their habitats probably less depleted than in<br />

most countries <strong>of</strong> the region. Many <strong>of</strong> the mammal, bird, reptile and amphibian species included in this review have been<br />

identified as being <strong>of</strong> national or global conservation significance. Indeed, <strong>Lao</strong> <strong>PDR</strong> has shared the discovery <strong>of</strong> new large<br />

and small mammal species in the Sai Phou Luang (Annamite) Range with neighbouring Vietnam since the first status report<br />

was published. However, virtually all wildlife is subject to increasing threat from habitat loss and, most significantly, unsustainable<br />

levels <strong>of</strong> harvest for subsistence use and trade. It has been estimated that annual sales <strong>of</strong> wildlife in Vientiane<br />

markets alone include up to 10,000 mammals (more than 23 species), 7,000 birds (more than 33 species) and 4,000 reptiles<br />

(more than eight species), with a weight <strong>of</strong> 33,000 kilograms. Particularly notable is the fact that hunting for the meat trade<br />

is higher in years <strong>of</strong> poor rice harvest, so the well-being <strong>of</strong> the country’s wildlife heritage is clearly linked to resolution <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Lao</strong> <strong>PDR</strong>’s broader development issues.<br />

As well as the national demand for wildlife and wildlife products, there is the major issue <strong>of</strong> the illegal, international<br />

trade in wildlife. As wildlife resources in nearby countries become more and more depleted, the relatively rich resource in<br />

<strong>Lao</strong> <strong>PDR</strong> becomes more valuable for illegal trade. The sad fact is that all recent surveys indicate that wildlife throughout <strong>Lao</strong><br />

<strong>PDR</strong>’s is declining.<br />

The Government <strong>of</strong> <strong>Lao</strong> <strong>PDR</strong> has taken numerous steps in recent years to halt this decline, including laws, policies,<br />

gun collection, protection <strong>of</strong> habitat in National Biodiversity Conservation Areas (NBCAs) and, in 1997, the declaration <strong>of</strong><br />

the annual ‘National <strong>Wildlife</strong> Conservation and Fish Release Day’ held on 13 July.<br />

In the face <strong>of</strong> an expanding human population and increasing development, the main hope for the conservation <strong>of</strong><br />

wildlife habitat in <strong>Lao</strong> <strong>PDR</strong> is in its protected area system, including NBCAs and provincial conservation areas. This is<br />

where the focus <strong>of</strong> attention, including international financial and technical support, is required. While zoos and captive<br />

breeding programmes can play an important role in education, awareness raising and research, the highest level <strong>of</strong> input is<br />

required to support in situ conservation in natural ecosystems. Critical to this approach is the development <strong>of</strong> collaborative<br />

management with local people who live in, as well as outside, protected areas and who depend to a large extent on forest<br />

products for subsistence and income generation. In turn, such collaborative approaches will require the formulation and<br />

application <strong>of</strong> effective conservation and development management models.<br />

However, if the <strong>Lao</strong> people are to maintain their wildlife heritage for future generations then the responsibility cannot<br />

only be placed on local people living in or near conservation areas. Effort is required at all levels, from district to national,<br />

from those who enforce laws and regulations to those who formulate the policies, laws and regulations. Further, education<br />

and awareness raising on wildlife conservation issues is everyone’s responsibility: those who purchase wildlife products in<br />

cities and towns are as much in need <strong>of</strong> this education as are villagers in rural areas who supply the demand. Finally, decline<br />

in wildlife populations is as much an international issue as it a national one. This means that international conventions on<br />

wildlife trade need to be enforced, but it also means that the international community should assist <strong>Lao</strong> <strong>PDR</strong> in conserving<br />

its wild species and habitats.<br />

Stuart Chape<br />

<strong>IUCN</strong> Representative<br />

<strong>Lao</strong> <strong>PDR</strong><br />

Venevongphet<br />

Director<br />

CPAWM<br />

Michael Hedemark<br />

Country Coordinator<br />

WCS<br />

iii

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS<br />

We gratefully acknowledge the contributions <strong>of</strong> many people to both the first and second editions <strong>of</strong> this status report. Bouaphanh<br />

Phanthavong, Khamphan Douangvilay, Khamphay Louanglath, Sansay Souriyakan, Sivannavong Sawathvong and Venevongphet organised<br />

the initial field surveys, which formed the basis for the modern understanding <strong>of</strong> the distribution on <strong>Lao</strong> wildlife, and conducted and<br />

translated village interviews. The bulk <strong>of</strong> the field information came from surveys <strong>of</strong> the joint Centre for Protected Areas and Watershed<br />

Management (CPAWM) / <strong>Wildlife</strong> Conservation Society (WCS) Cooperative Program and from surveys organised through <strong>IUCN</strong>-the<br />

World Conservation Union. These could not have been undertaken without the efforts in the field, over several years, <strong>of</strong> Boonhom<br />

Sounthala, Bounsou Souan, Chainoi Sisomphone, Chantavi Vongkhamheng, Khounmee Salivong, Padith Vanalatsmy, Pheng<br />

Phaengsintham, Phonasane Vilaymeing, Savanh Chanhthakoumane, Somphong Souliyavong and Soulisak Vanalath. Extensive conceptual<br />

advice for the second edition was received from many staff members <strong>of</strong> CPAWM, including Venevongphet, Chanthaviphone Inthavong,<br />

Sivannavong Sawathvong, Boonhom Sounthala, Savay Thammavongsa, Phetsamone Soulivong, Sirivanh Khounthikoumane and Sansay<br />

Souriyakan.<br />

We thank the following people who provided site records or other information on species status, particularly those who were willing<br />

to enter into correspondence to furnish supporting or other further details: Charles Alton, Ian Baird, John Baker, Jeb Barzen, Klaus<br />

Berkmüller, Bill Bleisch, Bob Dobias, Gordon Claridge, Skip Dangers, Nick Dymond, Tom Evans, Prithiviraj Fernando, Joost Foppes,<br />

Troy Hansel, Mike Hedemark, Rudi Jelinek, Nattakit Krathintong, Sirivanh Khounthikoumane, Stuart Ling, Clive Marsh, Mike Meredith,<br />

John Parr, Colin Poole, Alan Rabinowitz, Jean-François Reumaux, Philip Round, Sivannavong Sawathvong, George Schaller, Dave<br />

Showler, Boun-oum Siripholdej, Chainoi Sisomphone, Stephen Sparkes, Rob Steinmetz, Ole-Gunnar Støen, Tony Stones, Richard Thewlis,<br />

Rob Tizard, Joe Tobias, Chanthavi Vongkhamheng, Joe Walston, Laura Watson, James Wolstencr<strong>of</strong>t and Ramesh Boonratana a.k.a.<br />

Zimbo. Ian Baird, James Compton, Laurent Chazee, Ian ‘Johnny’ Johnson and Bounlueane Bouphaphan (Carnivore Preservation Trust),<br />

Esmond Bradley Martin, Pisit na Patalung and Sompoad Srikosamatara provided data and valuable insights into the trade in wildlife.<br />

Todd Sigaty (<strong>IUCN</strong> <strong>Lao</strong> <strong>PDR</strong>) made available his synthesis <strong>of</strong> wildlife law information. Sisouvanh Bouphavanh, Thanongsi Sorangkoun,<br />

Phayvanh Vongsaly and Xiong Tsechalicha <strong>of</strong> the <strong>IUCN</strong> Office in Vientiane assisted with data analysis and checking. Information on<br />

other topics was provided by Joost Foppes and Rachel Dechaineux (<strong>IUCN</strong> Non-Timber Forest Products Project), Bruce Jefferies (Forest<br />

Management and Conservation Project), Khankeo Oupravanh (CIDSE) and Kirsten Panzer (MRC/GTZ Forest Cover Mapping Project).<br />

Many people outside <strong>Lao</strong> <strong>PDR</strong> gave advice or assistance: George Allez; Per Alström; Lon Alterman (Clarke College, Iowa); Giovanni<br />

Amori (<strong>IUCN</strong>/SSC Rodent Specialist Group); Guy Anderson; Lehr Brisbin (Uni. Georgia, USA); Chen Hin Keong and Carol Wong<br />

(TRAFFIC South-east Asia); Nigel Collar, Jonathan Eames, Mike Evans and Janet Kwok (BirdLife International); Gabor Csorba (Hungarian<br />

Natural History Museum); Edward Dickinson; Robert Fisher and Linda Gordon (United States National Museum); Thomas<br />

Geissmann (Tierärztliche Hochschule, Hannover); Mariano Gimenez-Dixon (<strong>IUCN</strong>/SSC); Joshua Ginsberg, George Amato and Cheryl<br />

Chetkiewicz (WCS New York); Michael Green and Chris Wemmer (<strong>IUCN</strong>/SSC Deer Specialist Group); Huw Griffiths; Brian Groombridge<br />

and Jonathan Baillie (WCMC); Colin Groves (Australian National University); Clare Hawkins; Mandy Haywood and Alison Rosser<br />

(<strong>IUCN</strong>/SSC <strong>Wildlife</strong> Trade Programme); Lawrence Heaney and William Stanley (Field Museum <strong>of</strong> Natural History, Chicago); Simon<br />

Hedges (<strong>IUCN</strong>/SSC Asian Wild Cattle Specialist Group); Bob H<strong>of</strong>fmann (Mammal Division, Smithsonian Institution); Sakon Jaisomkom<br />

(WWF Thailand Project Office); Paula Jenkins and Daphne Hills (NHM, South Kensington); Ji Weizhi and Wang Yingxiang (Kunming<br />

Institute <strong>of</strong> Zoology); Ben King; Hans Kruuk; Bryn Mader and Fiona Brady (American Museum <strong>of</strong> Natural History); Tilo Nadler<br />

(Endangered Primate Rescue Center, Cuc Phuong National Park, Vietnam); Anouchka Nettelbeck; Jarujin Nabhitabhata (Thailand Institute<br />

<strong>of</strong> Science and Technological Research); Ronald Pine; Pamela Rasmussen, Philip Angle and Gary Graves (Bird Division, Smithsonian<br />

Institute); Philip Round; Nancy Ruggeri; Gerry Schroering; David Shackleton and Sandro Lovari (<strong>IUCN</strong>/SSC Caprinae Specialist Group);<br />

Chris Smeenk (National Natural History Museum, Leiden); Angela Smith; Paul Sweet (American Museum <strong>of</strong> Natural History); Lee<br />

Talbot; Julia Thomas; Harry Van Rompaey and Roland Wirth (<strong>IUCN</strong>/SSC Mustelid, Viverrid and Procyonid Specialist Group); Filip<br />

Verbelen; Wang Sung (Beijing Institute <strong>of</strong> Zoology, Academia Sinica); and David Willard (Field Museum <strong>of</strong> Natural History).<br />

Tim Inskipp’s work in maintaining an ornithological bibliography <strong>of</strong> Indochina laid considerably more than the cornerstone <strong>of</strong> the<br />

bird chapter and we gratefully acknowledge the free access to this draft document, provision <strong>of</strong> references and advice. We are also<br />

especially grateful to Craig Robson for answering many questions and providing frequent advice and a draft <strong>of</strong> his forthcoming identification<br />

guide to the birds <strong>of</strong> South-East Asia.<br />

The chapter on herpet<strong>of</strong>auna could never have been completed without the tremendous help <strong>of</strong> H. K. Voris and R. F. Inger and the<br />

rest <strong>of</strong> the staff in the Division <strong>of</strong> Amphibians and Reptiles at the Field Museum <strong>of</strong> Natural History, Chicago. Their identifications <strong>of</strong><br />

specimens and taxonomic discussions have been invaluable. Likewise, the field work which obtained most <strong>of</strong> the recent records could<br />

not have been conducted without the logistical and field support <strong>of</strong> the Department <strong>of</strong> Forestry, Vientiane. Thank you to the following<br />

curators and institutions for providing lists <strong>of</strong> <strong>Lao</strong> specimens held in their collections, and for granting permission to cite these specimens:<br />

Linda S. Ford, AMNH; Jens Vindum, CAS; Harold K. Voris, FMNH; Jose Rosado, MCZ; Greg Schneider, UMMZ; and Ron<br />

v

Crombie, USNM. Tanya Chan-ard allowed the author to examine his photographic and specimen records from <strong>Lao</strong> <strong>PDR</strong>. Rob Timmins<br />

kindly provided all <strong>of</strong> his unpublished field records <strong>of</strong> turtles and he and Peter Paul van Dijk gave much valuable insight. R. F. Inger<br />

provided helpful comments on the draft species accounts. This work was supported by the WCS <strong>Lao</strong> Program, National Geographic<br />

Society Grant # 6247-98, the Turtle Recovery Program <strong>of</strong> WCS, the Field Museum <strong>of</strong> Natural History Scholarship Committee, and the<br />

North Carolina Academy <strong>of</strong> Sciences. H. F. Heatwole and W. G. Robichaud provided general assistance throughout.<br />

C. M. Francis and A. Guillén thank the <strong>Lao</strong> Department <strong>of</strong> Forestry for permission to carry out field work for bats in <strong>Lao</strong> <strong>PDR</strong>, and<br />

Khamkhoun Khounboline, Chanhthavy Vongkhamheng, Khoonmy Salivong, Fung Yun Lin, Fiona Francis, Nik Aspey, Robert Tizard<br />

and Carlos Ibañez for assistance in the field. M. F. Robinson thanks the staff <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Lao</strong> <strong>PDR</strong> Department <strong>of</strong> Forestry and the Forest<br />

Management and Conservation Project (FOMACOP) for permission to survey small mammals in <strong>Lao</strong> <strong>PDR</strong> and for overseeing his field<br />

work; Robert Mather, Robert Steinmetz, and Bruce Jefferies for organising and ensuring the smooth running <strong>of</strong> the project; and Maurice<br />

Webber, Thongphanh Ratanalangsy, Sinnasone Seangchantharong, Kongthong Phommavongsa and Nousine Latvylay for assistance in<br />

the field. Financial support for CMF and AG was provided by WCS, the Senckenberg Museum, and Bird Studies Canada. MFR was<br />

funded by the Global Environment Facility (GEF) through the World Bank to the <strong>Lao</strong> <strong>PDR</strong> government, via a contract with Burapha<br />

Development Consultants and sub-contracted to World Wide Fund for Nature Thailand Project Office. Assistance with identifying some<br />

bat specimens was provided by Judith Eger, Dieter Kock and Paulina Jenkins. We thank Gabor Csorba (Hungarian Natural History<br />

Museum) for provision <strong>of</strong> information and Angela Smith for valuable advice on the manuscript.<br />

C. M. Francis thanks Mark Engstrom from the Royal Ontario Museum for assistance with identification <strong>of</strong> some <strong>of</strong> the rat specimens.<br />

Khamkhoun Khounboline, Chanhthavy Vongkhamheng, Nik Aspey, Robert Tizard and Antonio Guillén assisted with field work<br />

during his surveys <strong>of</strong> small mammals in <strong>Lao</strong> <strong>PDR</strong>. Financial support was provided by the WCS and Bird Studies Canada. Mark Robinson<br />

gave a critical review <strong>of</strong> an early draft <strong>of</strong> the murid chapter, and provided additional unpublished records. Guy Musser provided helpful<br />

information on taxonomy.<br />

Complete or partial drafts were reviewed by John Baker, Stuart Chape, Pete Davidson, Tom Evans, Colin Groves, Troy Hansel,<br />

Michael Hedemark and Arlyne Johnson, Clive Marsh, John Parr, Bill Robichaud, Sivannavong Sawathvong, Rob Timmins, Rob Tizard<br />

and Venevongphet. Their constructive comments did much to improve the quality <strong>of</strong> the eventual work. Margaret Jefferies sub-edited<br />

much <strong>of</strong> the text. We are very grateful to all the photographers (as listed in the captions) for permitting the free use <strong>of</strong> their images in this<br />

work.<br />

It would be remiss not to acknowledge the assistance <strong>of</strong> the drivers Bounthavi Phommachanh and Chansome, the Vientiane staff <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>IUCN</strong>, WCS and CPAWM, the many provincial and district <strong>of</strong>ficials who facilitated our surveys, and the villagers in rural <strong>Lao</strong> <strong>PDR</strong> who<br />

freely shared their knowledge <strong>of</strong> local wildlife during our surveys <strong>of</strong> remote rural areas.<br />

The support <strong>of</strong> Stuart Chape (<strong>IUCN</strong> Country Representative for <strong>Lao</strong> <strong>PDR</strong>), Bill Robichaud and Michael Hedemark (successive<br />

WCS <strong>Lao</strong> Program Co-ordinators) and Venevongphet (Director <strong>of</strong> CPAWM) at all stages <strong>of</strong> the project to produce a second edition was<br />

essential and is gratefully acknowledged. David Hulse generously permitted use <strong>of</strong> the facilities <strong>of</strong> the WWF <strong>of</strong>fice in Hanoi during<br />

preparatory data collation and extraction for the project. The base map is modified from one compiled by the ADB Regional Environment<br />

Technical Assistance Poverty Reduction and Environmental Management in Remote Watersheds <strong>of</strong> the Greater Mekong Subregion, using<br />

the data provided by CPAWM. Personally, the compilers thank the section authors for timely delivery, forbearance over editorial matters<br />

and in some cases extensive contribution to other aspects <strong>of</strong> the project.<br />

The second edition was produced with the assistance <strong>of</strong> <strong>IUCN</strong>’s South and Southeast Asia Regional Biodiversity Programme and the<br />

financial support <strong>of</strong> the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ).<br />

vi

ABBREVIATIONS AND CONVENTIONS<br />

Abbreviations<br />

Note: abbreviations specific to an individual chapter (e.g.<br />

those for frequently cited reference sources) are detailed at<br />

the front <strong>of</strong> the chapter in question.<br />

ARL At Risk in <strong>Lao</strong> <strong>PDR</strong> (see conventions)<br />

CARL Conditionally At Risk in <strong>Lao</strong> <strong>PDR</strong> (see conventions)<br />

CESVI Cooperazione e Sviluppo<br />

CIDSE Coopération Internationale pour le<br />

Developpement et la Solidarité.<br />

CITES Convention on International Trade in Endangered<br />

Species <strong>of</strong> wild fauna and flora<br />

CPAWM Centre for Protected Areas and Watershed<br />

Management <strong>of</strong> DoF<br />

DD Data Deficient (see conventions)<br />

DoF Department <strong>of</strong> Forestry <strong>of</strong> MAF<br />

FOMACOP Forest Management and Conservation<br />

Project<br />

GNT Globally Near-Threatened (see conventions)<br />

GT-CR Globally Threatened - Critical (see conventions)<br />

GT-EN Globally Threatened - Endangered (see conventions)<br />

GT-VU Globally Threatened - Vulnerable (see conventions)<br />

GTZ Deutsche Gesellschaft für Technische<br />

Zusammenarbeit<br />

<strong>IUCN</strong> The World Conservation Union<br />

LKL Little Known in <strong>Lao</strong> <strong>PDR</strong> (see conventions)<br />

LSFCP <strong>Lao</strong>-Swedish Forestry Cooperation<br />

Programme<br />

MAF Ministry <strong>of</strong> Agriculture and Forestry,<br />

Vientiane<br />

MNHN Muséum Nationale d’Histoire Naturelle,<br />

Paris, France.<br />

NBCA National Biodiversity Conservation Area<br />

NHM Natural History Museum, London and Tring,<br />

UK; formerly BM(NH)<br />

NR Nature Reserve<br />

PARL Potentially At Risk in <strong>Lao</strong> <strong>PDR</strong> (see conventions)<br />

PNBCA Proposed National Biodiversity Conservation<br />

Area<br />

Prov. PA Provincial Protected Area<br />

s.s. sensu stricto; used with species names where<br />

the content <strong>of</strong> the species varies. For example<br />

reference to Hylobates concolor (s.s.) does<br />

not include the forms gabriellae, siki and<br />

leucogenys, although some authors do include<br />

these forms within the species (see species<br />

account for further detail).<br />

SSC Species Survival Commission <strong>of</strong> <strong>IUCN</strong><br />

STENO National Office for Science, Technology and<br />

Environment.<br />

WCMC World Conservation Monitoring Centre,<br />

Cambridge, U.K.<br />

WCS <strong>Wildlife</strong> Conservation Society<br />

WWF WorldWide Fund for Nature/World <strong>Wildlife</strong><br />

Fund (North America only)<br />

• (at the start <strong>of</strong> a species account): the species<br />

is considered to be a key species: one <strong>of</strong><br />

special conservation significance.<br />

Conventions<br />

Global Threat Categories<br />

These categories are taken from the 1996 <strong>IUCN</strong> Red List<br />

<strong>of</strong> threatened animals (<strong>IUCN</strong> 1996) or, for birds, Collar et al.<br />

(1994). They relate to the threat to the survival <strong>of</strong> the species<br />

across its entire world range.<br />

Globally Threatened - Critical (GT-CR): the species faces<br />

an extremely high risk <strong>of</strong> extinction in the wild in the immediate<br />

future. Sometimes ‘Critically Endangered’ is used.<br />

Globally Threatened - Endangered (GT-EN): the taxon is<br />

facing a very high risk <strong>of</strong> extinction in the wild in the near<br />

future.<br />

Globally Threatened - Vulnerable (GT-VU): the taxon is<br />

facing a high risk <strong>of</strong> extinction in the wild in the mediumterm<br />

future.<br />

Globally Near-Threatened (GNT): the taxon is close to qualifying<br />

for Vulnerable.<br />

Data Deficient (DD): a taxon for which there is inadequate<br />

information to make a direct, or indirect, assessment <strong>of</strong> its<br />

risk <strong>of</strong> global extinction in the wild. This category does not<br />

imply that the species is certainly Globally Threatened, and<br />

further data could show that the species is presently secure<br />

globally. All species occurring in <strong>Lao</strong> <strong>PDR</strong> classified as Data<br />

Deficient (globally) by <strong>IUCN</strong> (1996) are clearly potentially<br />

or actually at risk in <strong>Lao</strong> <strong>PDR</strong>.<br />

These categories are discussed and defined formally (sometimes<br />

quantitatively) in <strong>IUCN</strong> (1996). Other categories listed<br />

there (e.g. Conservation Dependent) are not currently relevant<br />

to any species in <strong>Lao</strong> <strong>PDR</strong>.<br />

<strong>Lao</strong> <strong>PDR</strong> Risk Categories<br />

These categories relate specifically to the threat to survival<br />

<strong>of</strong> the species in <strong>Lao</strong> <strong>PDR</strong>. Elsewhere in its world range,<br />

it may be secure, even numerous. The classification system<br />

is taken from Thewlis et al. (1998), with modifications. Categories<br />

have been assigned to individual species specifically<br />

for the present work.<br />

vii

At Risk in <strong>Lao</strong> <strong>PDR</strong> (ARL): this category is roughly equivalent<br />

at a national level to the Globally Threatened categories<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>IUCN</strong> (1996). Minor amendments (see Thewlis et al. 1998)<br />

result in the exclusion <strong>of</strong> some species for which the only<br />

threat is long-term habitat loss and which might be considered<br />

‘Vulnerable’ following the criteria <strong>of</strong> <strong>IUCN</strong> (1996).<br />

Potentially At Risk in <strong>Lao</strong> <strong>PDR</strong> (PARL): this category includes<br />

species (a) suspected to be At Risk in <strong>Lao</strong> <strong>PDR</strong> but<br />

where information about threats or species status is insufficient<br />

to make a firm categorisation, and (b) species on or<br />

close to the borderline <strong>of</strong> At Risk in <strong>Lao</strong> <strong>PDR</strong>.<br />

Conditionally At Risk in <strong>Lao</strong> <strong>PDR</strong> (CARL): this category<br />

includes species which are not confirmed to be currently extant<br />

in <strong>Lao</strong> <strong>PDR</strong>, but if they are, will clearly be At Risk in<br />

<strong>Lao</strong> <strong>PDR</strong>. Usually, this judgement is made by analogy to the<br />

status <strong>of</strong> related species. This category is used with reptiles<br />

and mammals, but not birds: bird species now apparently<br />

extinct as breeders may recolonise from neighbouring countries,<br />

and some (perhaps all) <strong>of</strong> them continue to visit <strong>Lao</strong><br />

<strong>PDR</strong> as non-breeders in small numbers. Thus, categorisation<br />

<strong>of</strong> them as At Risk in <strong>Lao</strong> <strong>PDR</strong> is more appropriate.<br />

Little Known in <strong>Lao</strong> <strong>PDR</strong> (LKL): this category provides for<br />

species where the conservation status is difficult to assess,<br />

i.e. those with detection or identification problems, or where<br />

fieldwork within their preferred range and habitats has been<br />

restricted, or where threats or species status are not clear for<br />

other reasons.<br />

The <strong>Lao</strong> risk categories ARL/PARL/LKL are intended<br />

to be roughly equivalent to the global threat categories GT/<br />

GNT/DD applied at a national level. In order to forestall ambiguity,<br />

similar and therefore potentially confusable terms<br />

(e.g. ‘threatened in <strong>Lao</strong> <strong>PDR</strong>’/ ’near-threatened in <strong>Lao</strong> <strong>PDR</strong>’/<br />

’data deficient in <strong>Lao</strong> <strong>PDR</strong>’) were deliberately not chosen.<br />

A species <strong>of</strong> bird or large mammal not assigned a <strong>Lao</strong><br />

risk category is assessed to be secure in <strong>Lao</strong> <strong>PDR</strong> in the shortto<br />

medium-term. There are too few data for reptiles, amphibians,<br />

bats, murid rodents and insectivores to make conservation<br />

risk status assessments for all species.<br />

CITES Trade Categories<br />

These categories reflect the level <strong>of</strong> threat posed by international<br />

trade. Unlike global threat categories and <strong>Lao</strong> risk<br />

categories, which are merely designations to highlight a<br />

species’s status, CITES categories have a regulatory effect<br />

in trade between countries which are parties to the Convention<br />

on International Trade in Endangered Species <strong>of</strong> Wild<br />

Fauna and Flora.<br />

Appendix I: Species threatened with extinction which are or<br />

may be affected by trade. Trade in specimens between parties<br />

is only authorised in exceptional circumstances (although<br />

import and export for scientific purposes may be permitted).<br />

Appendix II: Species which although not necessarily now<br />

threatened with extinction may become so unless trade in<br />

specimens is subject to strict regulation in order to avoid overutilisation.<br />

Species may also be listed in Appendix II because<br />

<strong>of</strong> their similarity to more threatened species, as an aid to<br />

viii<br />

enforcement. Commercial trade in wild specimens listed on<br />

Appendix II is permitted between members <strong>of</strong> the convention,<br />

but is controlled and monitored through a licensing<br />

system.<br />

Miscellaneous definitions<br />

The region ‘Indochina’ indicates <strong>Lao</strong> <strong>PDR</strong>, Cambodia<br />

and Vietnam.<br />

Site names follow, where possible, the gazetteers <strong>of</strong> historical<br />

and recent <strong>Lao</strong> survey localities in Thewlis et al.<br />

(1998), Evans and Timmins (1998) and Duckworth et al.<br />

(1998a). These in turn were standardised to follow the<br />

République Democratique Populaire <strong>Lao</strong> Service<br />

Geographique d’Etat (SGE) 1:100,000 map series, with a few<br />

exceptions. For example, features straddling international<br />

boundaries were given their most usual international name,<br />

e.g. Annamite mountains rather than Sayphou Louang. In<br />

deference to widespread current usage, the map name ‘Nakay’<br />

(as used by Thewlis et al.) is changed here to ‘Nakai’. Showler<br />

et al. (1998a) used ‘Phou Ahyon’ for the area spelled ‘Phou<br />

Ajol’ in Thewlis et al. (1998); the massif is not named on the<br />

map series. Vientiane Municipality is also known as Vientiane<br />

Prefecture.<br />

Some <strong>of</strong> the map names are known to be erroneous, particularly<br />

with respect to transcription <strong>of</strong> <strong>Lao</strong> language into<br />

Roman characters. Rectifying these mistakes to produce a<br />

linguistically pure list <strong>of</strong> site names would be an enormous<br />

undertaking. More importantly, it is <strong>of</strong> very limited value to<br />

wildlife conservation to know whether Xaignabouli Province<br />

might better be spelt Sayabouri, Xaiaboury, or any <strong>of</strong><br />

the various other ways in which readers may encounter it:<br />

such knowledge is unlikely to affect conservation activity<br />

within it. Therefore, no changes are made on such grounds.<br />

Gazetteers in the above sources list co-ordinates and<br />

altitudes, except for some historical sites for which the<br />

locality was not traced. Names <strong>of</strong> sites used in the present<br />

work, but not in any <strong>of</strong> the foregoing gazetteers, are spelt as<br />

on the standard map series where possible. Otherwise, spelling<br />

from the original source is retained.<br />

Name elements <strong>of</strong> existing and proposed NBCAs follow<br />

Berkmüller et al. (1995a). Thus Nam Phoun is used here, in<br />

favour <strong>of</strong> Nam Phoui, although the latter is in wider current<br />

usage.<br />

Common <strong>Lao</strong> language elements in place names are: ban,<br />

village; don, island; dong, forest; doy, mountain; houay, river;<br />

lak, kilometer; muang, district capital town; nam, river; nong,<br />

pool or small lake; pa, forest; pak, river mouth; pha, exposed<br />

rocky peak (usually limestone); phou, mountain or peak;<br />

phouphiang, plateau; sayphou, ridge; sop, river mouth; thon,<br />

open area; vang, deep river pool; and xe, river. The map presentation<br />

for names incorporating lak is followed here, so that<br />

these names can be located by non-speakers <strong>of</strong> <strong>Lao</strong>. Spoken<br />

forms <strong>of</strong> sites <strong>of</strong> wildlife significance are:<br />

Ban Lak Kao: Ban Lak (9)<br />

Ban Lak Xao: Ban Lak (20)<br />

Ban Lak Xaophet: Ban Lak (28)<br />

Ban Lak Hasipsong: Ban Lak (52)

CONTENTS<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

PREFACE iii<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS v<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

ABBREVIATIONS AND CONVENTIONS vii<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

CONTENTS ix<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

INTRODUCTION 1<br />

INFORMATION SOURCES 2<br />

Protected Area Reconnaissance and Planning Surveys 1988-1993 2<br />

Site-and Species-specific <strong>Wildlife</strong> Surveys 2<br />

Trade Studies 2<br />

THE GEOGRAPHY AND BIOGEOGRAPHY OF LAO <strong>PDR</strong>: AN OVERVIEW 2<br />

Location and Political Units 2<br />

Human Population and Economy 3<br />

Physiography and Drainage 3<br />

Climate 5<br />

<strong>Wildlife</strong> Habitats 5<br />

Zoogeographic Relationships 9<br />

Geographical Subdivisions <strong>of</strong> <strong>Lao</strong> <strong>PDR</strong> 9<br />

HUMAN USE OF WILDLIFE 12<br />

Hunting Techniques 12<br />

Subsistence Hunting 13<br />

Recreational Hunting 16<br />

<strong>Wildlife</strong> Trade within <strong>Lao</strong> <strong>PDR</strong> 16<br />

Interprovincial and International <strong>Wildlife</strong> Trade 17<br />

Net Effects <strong>of</strong> Hunting 21<br />

<strong>Wildlife</strong> Farming 21<br />

Zoos 21<br />

Other <strong>Wildlife</strong>-Human Interactions 22<br />

WILDLIFE CONSERVATION IN LAO <strong>PDR</strong> 23<br />

Threats to <strong>Wildlife</strong> 23<br />

Legal Protection <strong>of</strong> <strong>Wildlife</strong> 25<br />

Public Conservation Education 25<br />

Field Management 27<br />

Research 32<br />

Staff Capacity Building 32<br />

CONCLUSIONS 32<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

AMPHIBIANS AND REPTILES 43<br />

INTRODUCTION 43<br />

CONVENTIONS 43<br />

ANNOTATED LIST OF SPECIES 44<br />

Ichthyophiidae: Caecilians 44<br />

Salamandridae: Salamanders 44<br />

Megophryidae: Asian horned frogs 44<br />

Bufonidae: True toads 45<br />

Ranidae: Typical frogs 45<br />

Rhacophoridae: Tree frogs 48<br />

Microhylidae: Leaf litter frogs 49<br />

ix

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

Platysternidae: Big-headed Turtle 50<br />

Emydidae: Typical turtles 50<br />

Testudinidae: Tortoises 52<br />

Trionychidae: S<strong>of</strong>tshell turtles 52<br />

Gekkonidae: Geckos 53<br />

Agamidae: Agamas 53<br />

Anguidae: Legless lizards 56<br />

Varanidae: Monitors 56<br />

Lacertidae: Old-world lizards 57<br />

Scincidae: Skinks 57<br />

Typhlopidae: Blind snakes 57<br />

Xenopeltidae: Sunbeam snakes 57<br />

Uropeltidae: Pipe snakes 57<br />

Boidae: Pythons 57<br />

Colubridae: Typical snakes 58<br />

Elapidae: Elapid snakes 60<br />

Viperidae: Vipers 60<br />

Crocodylidae: Crocodiles 60<br />

THREATS TO AMPHIBIANS AND REPTILES 64<br />

CONSERVATION OF AMPHIBIANS AND REPTILES 66<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

BIRDS 69<br />

INTRODUCTION 69<br />

Species Included 69<br />

Taxonomy and Nomenclature 69<br />

Distribution Within <strong>Lao</strong> <strong>PDR</strong> 69<br />

Seasonality <strong>of</strong> Occurrence 69<br />

Habitats and Altitudes 74<br />

Key Species <strong>of</strong> Special Conservation Significance 74<br />

Proposed Conservation Management and Research Measures 75<br />

CITES-listed and Restricted-range Species 75<br />

Historical Sources 77<br />

Recent Information 77<br />

ANNOTATED LIST OF SPECIES 79<br />

Phasianidae: Francolins, quails, partridges, pheasants etc. 79<br />

Dendrocygnidae: Whistling-ducks 94<br />

Anatidae: Geese, ducks 94<br />

Turnicidae: Buttonquails 95<br />

Picidae: Woodpeckers 96<br />

Megalaimidae: Asian barbets 98<br />

Bucerotidae: Hornbills 98<br />

Upupidae: Hoopoes 99<br />

Trogonidae: Trogons 99<br />

Coraciidae: Rollers 99<br />

Alcedinidae: River kingfishers 100<br />

Dacelonidae: Dacelonid kingfishers 100<br />

Cerylidae: Cerylid kingfishers 100<br />

Meropidae: Bee-eaters 101<br />

Cuculidae: Cuckoos 101<br />

Centropodidae: Coucals 103<br />

Psittacidae: Parrots 103<br />

Apodidae: Swifts 104<br />

Hemiprocnidae: Treeswifts 104<br />

Tytonidae: Barn owls 104<br />

x

Contents<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

Strigidae: Typical owls 105<br />

Batrachostomidae: Asian frogmouths 106<br />

Eurostopodidae: Eared nightjars 107<br />

Caprimulgidae: Typical nightjars 107<br />

Columbidae: Pigeons, doves 107<br />

Gruidae: Cranes 109<br />

Heliornithidae: Finfoots 110<br />

Rallidae: Rails, crakes, waterhens, coots 110<br />

Scolopacidae: Woodcocks, snipes, curlews, sandpipers, phalaropes 111<br />

Rostratulidae: Painted-snipes 115<br />

Jacanidae: Jacanas 115<br />

Burhinidae: Thick-knees 115<br />

Charadriidae: Stilts, plovers, lapwings 115<br />

Glareolidae: Pratincoles 116<br />

Laridae: Skimmers, gulls, terns 117<br />

Accipitridae: Osprey, bazas, kites, vultures, harriers, hawks, buzzards, eagles 118<br />

Falconidae: Falcons, falconets 121<br />

Podicepedidae: Grebes 123<br />

Anhingidae: Darters 123<br />

Phalacrocoracidae: Cormorants 123<br />

Ardeidae: Herons, egrets, bitterns 123<br />

Threskiornithidae: Ibises 125<br />

Pelecanidae: Pelicans 126<br />

Ciconiidae: Storks 126<br />

Pittidae: Pittas 127<br />

Eurylaimidae: Broadbills 128<br />

Irenidae: Fairy bluebirds, leafbirds 128<br />

Laniidae: Shrikes 129<br />

Corvidae: Whistlers, jays, magpies, crows, woodswallows, orioles, cuckooshrikes, minivets,<br />

flycatcher-shrikes, fantails, drongos, monarchs, paradise-flycatchers, ioras, woodshrikes 129<br />

Cinclidae: Dippers 132<br />

Muscicapidae: Thrushes, shortwings, true flycatchers, robins, redstarts, forktails, cochoas, chats 132<br />

Sturnidae: Starlings, mynas 137<br />

Sittidae: Nuthatches 138<br />

Certhiidae: Northern treecreepers 138<br />

Paridae: Penduline tits, true tits 139<br />

Aegithalidae: Long-tailed tits 139<br />

Hirundinidae: Swallows, martins 139<br />

Pycnonotidae: Bulbuls 142<br />

Cisticolidae: Cisticolas, prinias 143<br />

Zosteropidae: White-eyes 143<br />

Sylviidae: Tesias, old-world warblers, tailorbirds, grassbirds, laughingthrushes, babblers, parrotbills 144<br />

Alaudidae: Larks 154<br />

Nectariniidae: Flowerpeckers, sunbirds, spiderhunters 154<br />

Passeridae: Sparrows, wagtails, pipits, weavers, parrotfinches, munias 155<br />

Fringillidae: Finches, buntings 157<br />

Appendix: Species Omitted from the Foregoing List 157<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

LARGE MAMMALS 161<br />

INTRODUCTION 161<br />

Species Included 161<br />

Taxonomy and Scientific Nomenclature 161<br />

English Names 161<br />

Distribution and Habitat 161<br />

xi

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

Key Species <strong>of</strong> Special Conservation Significance 162<br />

Proposed Conservation Management and Research Measures 162<br />

CITES-listed and Restricted-range Species 162<br />

Historical Sources 162<br />

Recent Information 163<br />

ANNOTATED LIST OF SPECIES 165<br />

Manidae: Pangolins 165<br />

Tupaiidae: Treeshrews 173<br />

Cynocephalidae: Colugos 173<br />

Loridae: Lorises 173<br />

Cercopithecidae: Old-world monkeys 176<br />

Hylobatidae: Gibbons 179<br />

Canidae: Jackals, dogs, foxes 182<br />

Ursidae: Bears 183<br />

Ailuridae: Red Panda 185<br />

Mustelidae: Weasels, martens, badgers, otters 185<br />

Viverridae: Civets, linsangs, palm civets, otter civets 189<br />

Herpestidae: Mongooses 192<br />

Felidae: Cats 192<br />

Delphinidae: Marine dolphins 197<br />

Elephantidae: Elephants 198<br />

Tapiridae: Tapirs 199<br />

Rhinocerotidae: Rhinoceroses 200<br />

Suidae: Pigs 202<br />

Tragulidae: Chevrotains 203<br />

Moschidae: Musk deer 203<br />

Cervidae: Deer 206<br />

Bovidae: Cattle, goat-antelopes 209<br />

Sciuridae: Non-flying squirrels 213<br />

Pteromyidae: Flying squirrels 217<br />

Hystricidae: Porcupines 219<br />

Leporidae: Hares and rabbits 219<br />

Appendix: Species Omitted from the Foregoing List 220<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

ORDER INSECTIVORA 221<br />

INTRODUCTION 221<br />

ANNOTATED LIST OF SPECIES 221<br />

Erinaceidae: Gymnures 221<br />

Talpidae: Moles 221<br />

Soricidae: Shrews 222<br />

CONSERVATION MANAGEMENT AND RESEARCH PROPOSED FOR INSECTIVORA 223<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

ORDER CHIROPTERA: BATS 225<br />

INTRODUCTION 225<br />

ANNOTATED LIST OF SPECIES 225<br />

Pteropodidae: Old-world fruit bats 225<br />

Emballonuridae: Sheath-tailed bats 228<br />

Megadermatidae: False-vampires 228<br />

Rhinolophidae: Horseshoe bats 229<br />

Hipposideridae: Roundleaf bats, trident bats 230<br />

Vespertilionidae: Evening bats 231<br />

Molossidae: Free-tailed bats 234<br />

THREATS TO BATS 234<br />

CONSERVATION MANAGEMENT AND RESEARCH PROPOSED FOR BATS 235<br />

xii

Contents<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

ORDER RODENTIA, FAMILY MURIDAE 237<br />

INTRODUCTION 237<br />

ANNOTATED LIST OF SPECIES 237<br />

Murinae: Mice and rats 237<br />

Platacanthomyinae: Spiny and pygmy dormice 239<br />

Arvicolinae: Voles 239<br />

Rhyzomyinae: Bamboo rats 239<br />

RECENT INFORMATION ON MURIDAE 239<br />

CONSERVATION MANAGEMENT AND RESEARCH PROPOSED FOR MURIDAE 240<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

REFERENCES 241<br />

Written 241<br />

Unpublished personal communications 252<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

ANNEXES 253<br />

Annex 1. Selected mammal and bird species observed in markets, jewellery shops, souvenir shops, restaurants, zoos<br />

or otherwise in trade in <strong>Lao</strong> <strong>PDR</strong>, 1988-1993<br />

Annex 2. CITES-listed wildlife species reported by CITES parties as exported from or originating in <strong>Lao</strong> <strong>PDR</strong>,<br />

1983-1990<br />

Annex 3. Amphibian, reptile, bird and mammal species listed in CITES Appendix I or II recorded or reported from<br />

<strong>Lao</strong> <strong>PDR</strong><br />

Annex 4. Birds and large mammals associated with wetlands in <strong>Lao</strong> <strong>PDR</strong><br />

Annex 5. Distribution <strong>of</strong> selected species <strong>of</strong> mammal as assessed from village interviews in 1988-1993<br />

Annex 6. Revised list <strong>of</strong> key species <strong>of</strong> amphibians, reptiles, birds and mammals in <strong>Lao</strong> <strong>PDR</strong><br />

List <strong>of</strong> Tables<br />

Table 1. Relative frequency <strong>of</strong> wildlife species used as food in rural <strong>Lao</strong> <strong>PDR</strong><br />

Table 2. <strong>Report</strong>ed frequency <strong>of</strong> wildlife species as crop pests and livestock predators in rural <strong>Lao</strong> <strong>PDR</strong><br />

Table 3. Some recent reports <strong>of</strong> mammals attacking people in <strong>Lao</strong> <strong>PDR</strong><br />

Table 4: Threats to wildlife in <strong>Lao</strong> <strong>PDR</strong>, their root causes, and counter measures in place or in advance stages <strong>of</strong><br />

planning as <strong>of</strong> January <strong>1999</strong><br />

Table 5: Principal legal instruments addressing wildlife protection in <strong>Lao</strong> <strong>PDR</strong><br />

Table 6. National species conservation priorities for amphibians, reptiles, birds and mammals in <strong>Lao</strong> <strong>PDR</strong><br />

Table 7. Regions and divisions <strong>of</strong> <strong>Lao</strong> <strong>PDR</strong> as used for herpetological records<br />

Table 8. Results <strong>of</strong> interviews with local people on the presence <strong>of</strong> crocodiles<br />

Table 9. Possible future additions to the <strong>Lao</strong> avifauna<br />

Table 10. Changes to the list <strong>of</strong> key species <strong>of</strong> birds from Thewlis et al. (1998)<br />

Table 11. Records <strong>of</strong> key species <strong>of</strong> birds in survey areas across <strong>Lao</strong> <strong>PDR</strong> as <strong>of</strong> 28 February <strong>1999</strong><br />

Table 12. Records <strong>of</strong> key species <strong>of</strong> large mammals in survey areas across <strong>Lao</strong> <strong>PDR</strong> as <strong>of</strong> 28 February <strong>1999</strong><br />

Table 13. Hog Badger field records in <strong>Lao</strong> <strong>PDR</strong>, 1997-1998<br />

Table 14. Asian Golden Cat locality records in <strong>Lao</strong> <strong>PDR</strong>, 1992-1998<br />

Table 15. Summary <strong>of</strong> observations <strong>of</strong> rhinoceros products, 1988-1993<br />

List <strong>of</strong> Figures<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

Figure 1. Political subdivisions <strong>of</strong> <strong>Lao</strong> <strong>PDR</strong><br />

Figure 2. Physiographic units <strong>of</strong> <strong>Lao</strong> <strong>PDR</strong><br />

Figure 3. Biogeographic context <strong>of</strong> <strong>Lao</strong> <strong>PDR</strong><br />

Figure 4. <strong>Wildlife</strong> trade from <strong>Lao</strong> <strong>PDR</strong> through Vietnam to China<br />

Figure 5. Existing and proposed National Biodiversity Conservation Areas in <strong>Lao</strong> <strong>PDR</strong><br />

Figure 6. Areas where birds were surveyed for periods exceeding one week during 1992-1998 inclusive<br />

Figure 7. Areas where large mammals were surveyed for periods exceeding one week during 1992-1998 inclusive<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○<br />

253<br />

255<br />

257<br />

261<br />

266<br />

272<br />

13<br />

22<br />

23<br />

24<br />

26<br />

36<br />

44<br />

61<br />

70<br />

76<br />

80<br />

166<br />

188<br />

193<br />

201<br />

3<br />

5<br />

9<br />

17<br />

30<br />

78<br />

164<br />

xiii

List <strong>of</strong> Plates<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />