The Steppes: Crucible of Eurasia - units.muohio.edu - Miami University

The Steppes: Crucible of Eurasia - units.muohio.edu - Miami University

The Steppes: Crucible of Eurasia - units.muohio.edu - Miami University

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

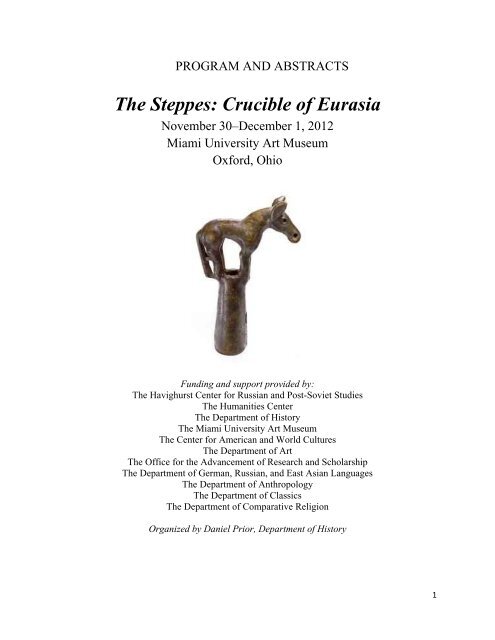

PROGRAM AND ABSTRACTS<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Steppes</strong>: <strong>Crucible</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Eurasia</strong><br />

November 30–December 1, 2012<br />

<strong>Miami</strong> <strong>University</strong> Art Museum<br />

Oxford, Ohio<br />

Funding and support provided by:<br />

<strong>The</strong> Havighurst Center for Russian and Post-Soviet Studies<br />

<strong>The</strong> Humanities Center<br />

<strong>The</strong> Department <strong>of</strong> History<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Miami</strong> <strong>University</strong> Art Museum<br />

<strong>The</strong> Center for American and World Cultures<br />

<strong>The</strong> Department <strong>of</strong> Art<br />

<strong>The</strong> Office for the Advancement <strong>of</strong> Research and Scholarship<br />

<strong>The</strong> Department <strong>of</strong> German, Russian, and East Asian Languages<br />

<strong>The</strong> Department <strong>of</strong> Anthropology<br />

<strong>The</strong> Department <strong>of</strong> Classics<br />

<strong>The</strong> Department <strong>of</strong> Comparative Religion<br />

Organized by Daniel Prior, Department <strong>of</strong> History<br />

1

PROGRAM<br />

This symposium is held in conjunction with the <strong>Miami</strong> <strong>University</strong> Art Museum exhibition, Grass Routes:<br />

Pathways to <strong>Eurasia</strong>n Cultures (August 20–December 8, 2012), which includes Ancient Bronzes <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Asian Grasslands, an exhibition from the Arthur M. Sackler Collections.<br />

http://muamgrassroutes.wordpress.com/<br />

http://arts.<strong>muohio</strong>.<strong>edu</strong>/art-museum/<br />

Friday, November 30<br />

9:15-9:45 a.m. Morning c<strong>of</strong>fee<br />

9:45-10:00 a.m. Welcome and opening remarks<br />

10:00-11:20 a.m. Claudia Chang and Perry Tourtellotte, Landscapes <strong>of</strong> Power and Elite<br />

Settlement at the Cusp <strong>of</strong> the Saka and Wusun Periods in Semirech’ye:<br />

<strong>The</strong> Talgar Case Study<br />

Jean-Luc Houle, Empire and Domestic Economy: Continuity and Change<br />

in Mongolia’s Bronze and Iron Age Archaeological Landscape<br />

Moderator: Michael Drompp<br />

11:20-11:40 a.m. Break<br />

11:40-1:00 p.m. Leland Rogers, Ancient DNA from the Elite Xiongnu at Ögiinuur Sum,<br />

Arkhangai, Mongolia<br />

Lois Hale, A Recreation <strong>of</strong> a Pazyryk Pouch<br />

Moderator: Katheryn Linduff<br />

1:00-2:30 p.m. Lunch<br />

Student Poster Session I (<strong>Eurasia</strong>n Nomads and History; Senior Capstone<br />

Seminar: <strong>The</strong> Horse in Human History)—in Gallery II:<br />

Robert Fink, Horse Meat Consumption in the United States; Zachary<br />

Horstman, Falconry on the <strong>Eurasia</strong>n <strong>Steppes</strong>; Thomas Hughes, <strong>The</strong> Takhi<br />

and Its Cousins: How People Have Interacted with Wild Equid Species;<br />

Laine Lagor, <strong>The</strong> Horse in the Circus; Andrew Mackin, Creating the<br />

Barbarian Myth; Troy Phillippe, <strong>The</strong> Horse in Early 20 th Century Film;<br />

Nicholas Schnitzler, America: A Country Built by Horses; Brian Smith,<br />

<strong>Eurasia</strong>n Nomads’ Geneses; Emily Volkmann, Horses <strong>of</strong> the Mexican-<br />

American War<br />

2:30-3:50 p.m. Michael Drompp, Political Dimensions <strong>of</strong> Religion in Early Medieval<br />

Inner Asian Empires<br />

Christopher Atwood, <strong>The</strong> Appanage Community: A New Model for<br />

Understanding Social Structure in the Pre-Modern Mongolian Plateau<br />

Moderator: Yihong Pan<br />

3:50-4:10 p.m. Break<br />

4:10-5:30 p.m. Robert Wicks, Bird-Headed Antler Tines: Stability and Change in Ancient<br />

<strong>Eurasia</strong>n Art<br />

Trudy Kawami, <strong>The</strong> Image <strong>of</strong> the Coiled Feline in the <strong>Eurasia</strong>n <strong>Steppes</strong><br />

Moderator: Kenneth Lymer<br />

2

Saturday, December 1<br />

9:30-10:00 a.m. Morning c<strong>of</strong>fee<br />

10:00-11:20 a.m. Sergey Miniaev, Ordos Style Bronzes in Russia: New Discoveries<br />

William Honeychurch (co-authors: James Lankton, Chunag Amartuvshin),<br />

Silk Roads or Steppe Roads: Gobi Evidence for Mediterranean Goods in<br />

the Xiongnu Polity<br />

Moderator: Claudia Chang<br />

11:20-11:40 a.m. Break<br />

11:40-1:00 p.m. Yihong Pan, Locating Advantages: <strong>The</strong> Survival <strong>of</strong> the Tuyuhun 吐谷渾<br />

State on the Edge (300-580s)<br />

Aleksandr Naymark, Sogdiana–Mawarannahr: <strong>The</strong> Life on the Edge <strong>of</strong><br />

the <strong>Steppes</strong><br />

Moderator: Matthew Gordon, Department <strong>of</strong> History, <strong>Miami</strong> <strong>University</strong><br />

1:00-2:30 p.m. Lunch<br />

Student Poster Session II (<strong>Eurasia</strong>n Nomads and History; Senior Capstone<br />

Seminar: <strong>The</strong> Horse in Human History)—in Gallery II:<br />

Rachel Blake, What Is It with Girls and Horses? How Societal Needs<br />

Fostered the Love between Horses and Girls; Daniel Brooks, <strong>The</strong> Horse<br />

and Cowboy Culture: Truth and Tall Tales; Brooke Clifford,<br />

Anthropomorphism: How Our View <strong>of</strong> the Horse Shapes Modern Society;<br />

Nicholas DiCesare, <strong>The</strong> Magyar Migration: <strong>The</strong> Transition from<br />

Nomadism to Sedentarism; Kimberly Foster, Kalmyk Sovereignty: From<br />

Nomadic Supremacy to Russian Ascendance; Vincent Kuertz, <strong>The</strong> New<br />

World, Plus and Minus Horses; Corey Lack, <strong>The</strong> Global Nomad: <strong>The</strong><br />

Comparison <strong>of</strong> Native American Indians and <strong>Eurasia</strong>n Nomads; Erin<br />

McCrate, <strong>The</strong> Modified Horse<br />

2:30-3:50 p.m. Kenneth Lymer, Animals Entangled in Art: <strong>The</strong> Lives <strong>of</strong> Zoomorphic<br />

Imagery in Central Asia during the 1st Millennium BCE<br />

Katheryn Linduff, Belt Buckles: Metallurgical and Iconographic Markers<br />

<strong>of</strong> Distinction<br />

Moderator: Trudy Kawami<br />

3:50-4:10 p.m. Break<br />

4:10-5:30 p.m. Daniel Prior, Integral or Incidental? Indo-European Mythic Fragments in<br />

Inner Asia<br />

Edward Vajda, Between Forest and Steppe: Language and Ethnicity in<br />

Early Inner Asia<br />

Moderator: Christopher Atwood<br />

3

ABSTRACTS<br />

Christopher Atwood, Department <strong>of</strong> Central <strong>Eurasia</strong>n Studies, Indiana <strong>University</strong><br />

(catwood@indiana.<strong>edu</strong>)<br />

<strong>The</strong> Appanage Community: A New Model for Understanding Social Structure in the Pre-Modern<br />

Mongolian Plateau<br />

Recent interventions in the study <strong>of</strong> nomadic societies have left foundational principles in<br />

flux. David Sneath’s Headless State has challenged existing paradigms, yet has also been itself<br />

challenged for skating too lightly over contrary data. While there is much to support in the recent<br />

challenges to the “tribal” paradigm, an alternative paradigm for ground-level social reality is still<br />

needed. Based on current research in thirteenth to nineteenth century Mongolian society, I<br />

propose that the “appanage community” as a fundamental concept for understanding the<br />

interaction <strong>of</strong> state and society on a local scale in Mongolia. <strong>The</strong> “appanage community” concept<br />

focuses on the key common aspects to the Qing-era banner, the sixteenth century otog, and the<br />

“thousands” in the Mongol empire, enabling them to be understood not just as a typology, but<br />

also the shape <strong>of</strong> a peculiar socio-political dynamic. This approach also supplies archaeologists<br />

with a potential model <strong>of</strong> local interaction to be tested in contexts preceding the thirteenth<br />

century.<br />

Claudia Chang and Perry Tourtellotte, Department <strong>of</strong> Anthropology, Sweetbriar College<br />

(cchang@sbc.<strong>edu</strong>; ptourtellotte@sbc.<strong>edu</strong>)<br />

Landscapes <strong>of</strong> Power and Elite Settlement at the cusp <strong>of</strong> the Saka and Wusun Periods in<br />

Semirech’ye: <strong>The</strong> Talgar Case Study<br />

How did the aristocratic elite nomads controlled the steppe and its vast resources<br />

throughout the first millennia BC ? In the Talgar region <strong>of</strong> Semirech’ye (Seven-Rivers) along the<br />

northern edge <strong>of</strong> the Tian Shan Mountains, ancient Iron Age cultures flourished, practicing both<br />

farming and animal herding. This paper explores two central questions: (1) What was the<br />

environmental and economic basis for mixed farming and herding during the first millennium<br />

BCE on the Talgar alluvial fan and (2) How did the mortuary practice <strong>of</strong> kurgan construction<br />

along ancient stream beds create both an ideological and political symbol <strong>of</strong> hierarchy among the<br />

‘nomadic confederacies?’<br />

We focus specifically on the Talgar alluvial fan as a land feature that serves as a model<br />

for settlement and hierarchy throughout the Semirech’ye region. Archaeological surveys and<br />

excavations conducted over the past 18 years by the Kazakh American Archaeological<br />

Expedition (KAAE) provide a substantial data base for examining the social evolution <strong>of</strong><br />

nomadic groups during the first millennium BC among the Saka (eastern variants <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Scythians) and the Wusun state. Yet recent studies contradict the ‘nomadic model’ in favor <strong>of</strong> a<br />

mixed economy <strong>of</strong> cereal farming and animal herding.<br />

<strong>The</strong> paleo-ethnobotanical evidence <strong>of</strong> both seeds and microscopic plant parts known as<br />

phytoliths demonstrates that between 400 BC and 200 BC the ancient herders <strong>of</strong> the Talgar<br />

region also cultivated wheat, millets, and barley (Spengler et al. in press; Chang et. al. 2003).<br />

Ongoing zooarchaeological research identifies the use <strong>of</strong> domesticated species <strong>of</strong> sheep and<br />

goats, cattle, and horses as well as occasional wild species such as roe and red deer, wild pig,<br />

4

fox, and birds (Chang et al. 2003). <strong>The</strong> recent excavations at Tuzusai, a large settlement in the<br />

Talgar region (ca. 8 to 10 hectares), reveals the existence <strong>of</strong> both common and elite households.<br />

At the most recent 2012 excavations, an elite platform or plaza area has been identified along<br />

with lower rooms and storage pits.<br />

<strong>The</strong> goal <strong>of</strong> this essay will be to summarize our most recent results that now show the<br />

Talgar fan as an agro-pastoral economy where an elite or aristocratic class <strong>of</strong> individuals, <strong>of</strong>ten<br />

associated with the rich inventories found at the burial kurgans controlled the commoners who<br />

practiced multi-resource pastoralism and agriculture. <strong>The</strong> prominent burial mounds which<br />

dominate the landscape throughout Talgar and neighboring fans served as symbolic<br />

representations <strong>of</strong> power and hierarchical control over vast territories. <strong>The</strong> geographic<br />

investigation <strong>of</strong> other alluvial fans along the base <strong>of</strong> the Tian Shan will also show the means by<br />

which elites controlled territory through a symbolic landscape <strong>of</strong> kurgan constructions.<br />

Michael R. Drompp, Department <strong>of</strong> History, Rhodes College (drompp@rhodes.<strong>edu</strong>)<br />

Political Dimensions <strong>of</strong> Religion in Early Medieval Inner Asian Empires<br />

In this paper I will examine some <strong>of</strong> the ways in which religious beliefs and practices<br />

have intersected with political beliefs and practices in early medieval Inner Asian empires. In<br />

considering the examples <strong>of</strong> the Rouran and Türks (Chinese Tujue), who dominated much <strong>of</strong><br />

Inner Asia from the early fifth to the mid-eighth centuries CE, I will focus on surviving historical<br />

accounts as well as preserved myths in order to search for the presence <strong>of</strong> mantic-religious<br />

beliefs and practices that could fall within the broad categorization <strong>of</strong> “shamanism” (which,<br />

admittedly, is a complex and even volatile term). I will then further explore the possible political<br />

connections and ramifications <strong>of</strong> these particular historical accounts and legends. Finally, I will<br />

consider the relationship <strong>of</strong> a posited “shamanic-political” complex to a broader “religiouspolitical”<br />

complex; the purpose <strong>of</strong> this will be to consider evidence as to how shamanic beliefs<br />

and practices may have related to the Rouran and Türk empires’ support <strong>of</strong> more highly<br />

organized religious beliefs and practices such as Buddhism or the state cult sometimes called<br />

“Tengrism.” Although the evidence at our disposal is relatively slim, my conclusion is that<br />

shamanic beliefs and practices were particularly useful for the promotion or reinforcement <strong>of</strong><br />

political legitimacy in Inner Asia; Rouran and Türk rulers employed mythologies, some <strong>of</strong> them<br />

quite likely borrowed, that indicated – through the evocation <strong>of</strong> a shamanic world view –<br />

powerful supernatural support for their states. Such mythologies provided ideological support<br />

for these steppe empires and thus helped strengthen their political power.<br />

Lois Hale, Hale! Art, Portland, Oregon (hlutwige@gmail.com)<br />

A Recreation <strong>of</strong> a Pazyryk Pouch<br />

1. Introduction<br />

In the Altai Mountain region <strong>of</strong> Siberia called Pazyryk, a group <strong>of</strong> barrows which<br />

belonged to tribes <strong>of</strong> Iron Age Scythians were excavated between 1929 through 1949 by Sergei<br />

Ivanovich Rudenko. <strong>The</strong> excavations <strong>of</strong> these barrows produced some <strong>of</strong> the most spectacular<br />

Central Asian artifacts ever unearthed. Among these artifacts was a small pouch which held,<br />

among other things, coriander seeds. Made with leather, felt, and leopard fur, decorated with<br />

gilded copper “duckling” figures and sewn with deer sinew, the pouch is notable due to the<br />

refinement <strong>of</strong> its construction and beauty <strong>of</strong> its decorative elements. It was found with other<br />

5

artifacts within a larger leather pouch and had suffered severe damage while entombed. It<br />

captured my imagination and has held my interest for more than a decade. Prior to my first<br />

attempts at a reconstruction I pored over thoughts <strong>of</strong> the pouch again and again always with the<br />

question in mind, “How was this made?” With only three illustrations and several paragraphs <strong>of</strong><br />

text from which I could draw information, its reconstruction has been a challenge.<br />

2. Process<br />

I studied the three illustrations provided in the English translation <strong>of</strong> “Frozen Tombs <strong>of</strong><br />

Siberia” by Rudenko as well as all the pertinent information I could glean from the text that<br />

referred to the construction <strong>of</strong> this and other like artifacts from the various barrows. Because<br />

there were no dimensions provided <strong>of</strong> this pouch, I used the illustration <strong>of</strong> the gilded copper<br />

ducklings which has a 1/1 ratio notation as my base “measurement”. I used it to gain an<br />

approximation <strong>of</strong> the actual size using the “reconstruction” illustration among the editions colour<br />

plates. After creating several mock-ups <strong>of</strong> the pouch I was satisfied with the similarity between<br />

my mock up and the illustrations, I moved on to reconstructing the pouch. Sable, which was<br />

found to have been used in other artifacts, rather than leopard fur was used. Cow and deer<br />

leathers were used for the excised decoration, pouch back and interior bag. Felt for the pouch<br />

was made from wool and dyed with madder and alum which according to my research are<br />

common dye stuffs <strong>of</strong> the time and area. A matrix was carved into a bronze plate for the copper<br />

figures. Deer sinew thread was used throughout the reconstruction process.<br />

3. Conclusion<br />

Over the course <strong>of</strong> four attempts at reconstructing the pouch I learned new lessons. Real<br />

sinew is versatile and very strong, and not as difficult to make as my early research indicated;<br />

indeed, making it as fine as modern sewing thread is a simple task with practice. <strong>The</strong> creation <strong>of</strong><br />

gilded copper ducks brought its own difficulties—experimenting with matrices, metal plaques<br />

and the gilding there<strong>of</strong>. Even the process <strong>of</strong> discovering how to make a small piece <strong>of</strong> felt<br />

remotely comparable to those used in the period was a challenge. <strong>The</strong> levels <strong>of</strong> craftsmanship<br />

and artistry were exceptional among the people <strong>of</strong> the Pazyryk. <strong>The</strong>y were highly skilled,<br />

influential and devoted artists and I find myself in awe <strong>of</strong> their ability to produce such stunning<br />

folk art. In my own endeavors, I continue to be inspired by their example.<br />

William Honeychurch, Department <strong>of</strong> Anthropology, Yale <strong>University</strong> (co-authors: James<br />

Lankton, Chunag Amartuvshin; william.honeychurch@yale.<strong>edu</strong>)<br />

Silk Roads or Steppe Roads: Gobi Evidence for Mediterranean Goods in the Xiongnu Polity<br />

Nomadic peoples <strong>of</strong> the Inner Asian steppe have long been credited with playing a role in<br />

facilitating exchange along the famous Silk Roads reaching across <strong>Eurasia</strong>. Steppe empires,<br />

including those <strong>of</strong> the Turks, Uighurs, and Mongols in cooperation with sedentary merchants,<br />

provided transport, protection, infrastructure, and in many cases negotiated access to some <strong>of</strong> the<br />

most prestigious Chinese goods traveling westward. However, since the historical record <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Silk Roads was written almost exclusively within sedentary, urban societies, the organizational<br />

role <strong>of</strong> nomadic groups and polities is <strong>of</strong>ten obscure. This is particularly true during the earliest<br />

period <strong>of</strong> Silk Road exchange contemporary with the Han Dynasty <strong>of</strong> China and the Xiongnu<br />

state (3rd c. BC - AD 2nd c.) <strong>of</strong> Mongolia. Some historians have argued that greater emphasis<br />

should be placed on the role <strong>of</strong> steppe nomadic groups in creating and sustaining the earliest<br />

forms <strong>of</strong> Silk Road exchange. Recent anthropological understandings <strong>of</strong> Inner Asian nomadic<br />

polities and steppe pastoralism suggest new possibilities for conceptualizing nomadic input to the<br />

6

ise <strong>of</strong> the Silk Roads. In this paper, I explore historical and archaeological evidence for Xiongnu<br />

state interaction with Central Asia and with China and critique the long standing assumption that<br />

eastern steppe nomads were peripheral to or predatory upon exchange between East and West. I<br />

suggest that nascent Silk Road activities were likely a critical part <strong>of</strong> the political economy <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Xiongnu state and examine the possibility <strong>of</strong> nomads as early architects <strong>of</strong> <strong>Eurasia</strong>n trade.<br />

Jean-Luc Houle, Department <strong>of</strong> Folk Studies and Anthropology, Western Kentucky <strong>University</strong><br />

(jean-luc.houle@wku.<strong>edu</strong>)<br />

Empire and Domestic Economy: Continuity and Change in Mongolia’s Bronze and Iron Age<br />

Archaeological Landscape<br />

This paper addresses the issue <strong>of</strong> social and political change from the Bronze Age to the<br />

Iron Age Xiongnu period by investigating continuity and change in the domestic economy in the<br />

Khanuy region <strong>of</strong> north central Mongolia. My goal is to assess the nature and the degree <strong>of</strong><br />

integration <strong>of</strong> ideology, economy and politics as the region’s populace shifted from a series <strong>of</strong><br />

independent small-scale polities to part <strong>of</strong> an ‘imperial’ state. We now know that during the Late<br />

Bronze Age herders in Khanuy Valley were becoming increasingly complex largely as a result <strong>of</strong><br />

local interaction (Houle 2010). Once incorporated into the Xiongnu imperial polity, political<br />

power became markedly more centralized and the political economy more extensive. In<br />

analyzing both pre Xiongnu and Xiongnu Period situations, I focus on the internal dynamics and<br />

the external links <strong>of</strong> production, distribution, and consumption. I am mostly interested here with<br />

the changes in daily life (or lack there<strong>of</strong>) that came about when Khanuy Valley people were<br />

incorporated into a political system that was greater in scale and focused on relationships<br />

external to Khanuy Valley. As radical as some changes were under Xiongnu rule, the evidence is<br />

equally interesting for the economic continuities. Most importantly, households and communities<br />

apparently continued to be largely self-sufficient in their subsistence and utilitarian craft<br />

production.<br />

Trudy S. Kawami, Arthur M. Sackler Foundation, New York<br />

(tkawami@arthurmsacklerfdn.org)<br />

<strong>The</strong> Coiled Feline in the Iron Age <strong>Steppes</strong>: An Art Historical View<br />

<strong>The</strong> image <strong>of</strong> the coiled feline, considered a typical motif in Scythian art <strong>of</strong> the 7 th<br />

century BCE, is an art historical puzzle. It has no immediate antecedents in the art <strong>of</strong> the steppes,<br />

and the excavated examples, which range from the Crimea to northern China, are strikingly<br />

similar in style. Furthermore, they are not randomly distributed, but occur in specific regions.<br />

Even in these regions, the image is found only in elite graves and even then rarely. Objects<br />

bearing the coiled feline are not multiples like the belt and garment ornaments <strong>of</strong> the steppe<br />

peoples, but are singular works found on horses or associated with horse gear. <strong>The</strong> sudden<br />

appearance <strong>of</strong> this distinctive image, its restricted occurrence, and rapid spread across the steppes<br />

suggest that it was an intentionally created emblem associated with the horses <strong>of</strong> a limited<br />

though widespread elite.<br />

7

Katheryn M. Linduff, Department <strong>of</strong> Anthropology and Department <strong>of</strong> the History <strong>of</strong> Art and<br />

Architecture, <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Pittsburgh (linduff@pitt.<strong>edu</strong>)<br />

Belt Buckles: Metallurgical and Iconographic Markers <strong>of</strong> Distinction<br />

Four thousand years ago cultures emerged in the area known variously as eastern <strong>Eurasia</strong>,<br />

Inner Asia, the beifang (北方), the Northern Zone, or the Northern Frontier. Delineated by<br />

Chinese historians <strong>of</strong> the second century BCE and later as a never-never land, they gave these<br />

peoples various names that marked them with a heritage distinct from peoples in the Dynastic<br />

heartland. So troublesome was this area for the dynasts, that they eventually set up a system <strong>of</strong><br />

‘border states’ and walls in their north that acted as a political, economic, cultural and military<br />

barrier reef meant to protect the ‘civilized’, agricultural states to their south.<br />

<strong>The</strong> signs <strong>of</strong> this separation were marked as well with lightweight and portable artifacts<br />

used in the beifang—small in scale but intricate in design—including belt plaques, appliqués for<br />

clothing as well as accompanying horse gear, bits, strap crossers and bridle ornaments and<br />

including chariot and cart fittings in gold, silver and bronze. <strong>The</strong>se were neither Chinese nor<br />

steppic in type or aesthetic, but rather were inspired by both models. <strong>The</strong>se pieces bear motifs <strong>of</strong><br />

the wild animals and birds <strong>of</strong> prey that inhabited the region—tigers, boar, deer, ibex—and<br />

including some domesticates such as camels, horses, donkeys and yaks. Even swords and knives<br />

bear animal ornamentation on their hilts and pommels. <strong>The</strong>se were created for the local<br />

inhabitants and the market, and most <strong>of</strong>ten in Chinese foundries, as best as we can tell. <strong>The</strong>y<br />

have <strong>of</strong>ten been thought to document a mobile lifeway, although that notion is rethought here.<br />

Study <strong>of</strong> the metallographic and casting technology used to produce these materials not<br />

only <strong>of</strong>fers a way to learn about their unique character, but also to discern distinctive cultural<br />

patterns and the process <strong>of</strong> interregional exchange in the region that led to their creation. Belt<br />

plaques, which I will particularly address here, were a very special category—not merely<br />

decorative, but given their final resting place in burial; their special types and iconography; their<br />

resourceful means <strong>of</strong> production; and their elaboration with inset semi-precious stones and<br />

gilding or silvering, marked them for special use. By the end <strong>of</strong> the first millennium BCE, they<br />

were in great demand in many areas <strong>of</strong> <strong>Eurasia</strong> and both the metallurgical and iconographic<br />

content are distinctive residue <strong>of</strong> invention as a result <strong>of</strong> culture contact and exchange. At the<br />

frontiers <strong>of</strong> the Chinese and Xiongnu Empires, they had become practicable signs <strong>of</strong> inter and<br />

intra community differentiation.<br />

Kenneth Lymer, Wessex Archaeology Ltd, Salisbury, UK (k.lymer@wessexarch.co.uk)<br />

Animals Entangled in Art: <strong>The</strong> Lives <strong>of</strong> Zoomorphic Imagery in Central Asia during the 1st<br />

Millennium BCE<br />

<strong>The</strong> art <strong>of</strong> early nomadic archaeological cultures that roamed the steppes <strong>of</strong> <strong>Eurasia</strong><br />

during the 1st millennium BCE is characterised as exhibiting predominantly zoomorphic imagery,<br />

the so-called Scytho-Siberian ‘animal style’. Moreover, it could be said that the concept <strong>of</strong> the<br />

‘animal style’ was born in Central Asian academic studies. O.M. Dalton in his monograph on the<br />

Oxus Treasure (1905) found objects recovered from what is known today as Tajikistan had a<br />

style similar to known Scythian objects recovered from the regions around the Black Sea.<br />

Furthermore, Dalton found this ‘Scythic art’ was also based upon animal decorative forms and<br />

held a uniform canon <strong>of</strong> taste that was an unmistakable characteristic <strong>of</strong> the cultures ranging<br />

from the Yenisei river to the Carpathians. <strong>The</strong> actual coining <strong>of</strong> the ‘animal style’, however,<br />

8

came to the fore after M.I. Rostovtseff’s seminal English publication on the Iranians and Greeks<br />

in South Russia in 1922. Nevertheless, these traditional concepts <strong>of</strong> art history from the<br />

beginning <strong>of</strong> the 20th century forged an Orientalist ideal <strong>of</strong> animal art and early nomads that still<br />

continues to be drawn upon to the present day.<br />

When we place these zoomorphic artefacts on display in a museum they become isolated<br />

and disparate objects intermixed with varying items from other cultures in time and space. Set on<br />

a neutral background under focused light in the display case their exoticness becomes the focus<br />

<strong>of</strong> attention. <strong>The</strong>re is no doubt to our eyes that many <strong>of</strong> these animal decorations are beautiful to<br />

look at; however, appreciating their visual aesthetics is only one aspect in the greater range <strong>of</strong><br />

sensory experiences connected to objects. Moreover, this was not how the art was originally<br />

intended to be perceived as the gallery is a contrived effect far removed from the actual living<br />

context <strong>of</strong> the animal imagery. As ethnographic studies have pointed out time and time again, the<br />

reality <strong>of</strong> material culture exists within the lives <strong>of</strong> their owners and users. Thus, Scytho-Siberian<br />

zoomorphic decorations were not solely objects <strong>of</strong> art but were intimately entangled in the daily<br />

lives <strong>of</strong> people within past societies.<br />

This entanglement is examined through a selection <strong>of</strong> case studies that focus upon<br />

different aspects <strong>of</strong> the lives <strong>of</strong> animal decorations and zoomorphic imagery. Within the early<br />

nomadic archaeological cultures <strong>of</strong> Kazakhstan, the Altai Republic and Tuva the animal images<br />

were intimately related to how individuals created and asserted their own identities through their<br />

choices <strong>of</strong> decoration on and <strong>of</strong>f their bodies, as well as the bodies <strong>of</strong> their horses. Moreover, the<br />

zoomorphics and their applications to various media embodied ‘ways <strong>of</strong> sensing’ by different<br />

societies. In particular, so-called ‘animal style’ iconography carved in the natural rock at<br />

petroglyph sites was part and parcel <strong>of</strong> sensual experiences <strong>of</strong> places and spaces in the landscape.<br />

Overall, animal decorated objects were not artefacts that operated autonomous to society<br />

but co-existed in dynamic relationships with individuals in their communities; the lives <strong>of</strong> the<br />

zoomorphic ornamentations were intimately entangled within people’s lives. Thus, it is by the<br />

closer scrutiny <strong>of</strong> their contextual complexity, as well as exploring their sensuous aspects, which<br />

enable us to explore fresher understandings about animal art in past societies in Central Asia<br />

during the first millennium BCE.<br />

Sergey Miniaev, Institute <strong>of</strong> the History <strong>of</strong> Material Culture, Russian Academy <strong>of</strong> Sciences, St.<br />

Petersburg (ssmin@yandex.ru)<br />

Ordos Style Bronzes in Russia: New Discoveries<br />

In recent years during scientific digs in Xiongnu archaeological sites in Russia a lot<br />

bronzes <strong>of</strong> “Ordos style” were found. <strong>The</strong> great value <strong>of</strong> the collection is that the objects were<br />

found in undisturbed tombs. Now we can know the disposition <strong>of</strong> all finds in the tombs and the<br />

function <strong>of</strong> every find. <strong>The</strong> majority <strong>of</strong> the “Ordos bronzes” were found on women’s and men’s<br />

belts. <strong>The</strong> sizes and quantity <strong>of</strong> details on the belts depended on the sex, age and social position<br />

<strong>of</strong> the owner.<br />

Thanks to new finds we can present different versions <strong>of</strong> Xiongnu belt sets, from the<br />

simplest belt to the most complicated. <strong>The</strong> most complicated belt consisted <strong>of</strong> the central part<br />

(two bronze plaques as a rule; many plaques had a special wood lining) and diverse other details<br />

- small plaques, open-work rings, small rings, fastenings, buttons, buckles etc. Besides, the belt<br />

frequently was decorated with different beads and buckles made from minerals. All bronze<br />

plaques have scenes in “Ordos style”: a skirmish between two horses, a beast <strong>of</strong> prey catching a<br />

9

herbivore, fantastic scenes (a struggle between two dragons for example). ). Simpler belts<br />

consisted <strong>of</strong> small bronze plaques and beads. <strong>The</strong> details <strong>of</strong> the simplest belt were constructed<br />

from one or two iron buckles only.<br />

<strong>The</strong> collection considerably supplements a presentation about Xiongnu art: an image <strong>of</strong> a<br />

he-goat on a seal; a plaque depicting a skirmishing between two dragons; other plaques and<br />

plates are unique.<br />

Aleksandr Naymark, Department <strong>of</strong> Fine Arts, Art History and Comparative Arts and Culture,<br />

H<strong>of</strong>stra <strong>University</strong> (Aleksandr.Naymark@h<strong>of</strong>stra.<strong>edu</strong>)<br />

(Abstract unavailable)<br />

Yihong Pan, Department <strong>of</strong> History, <strong>Miami</strong> <strong>University</strong> (pany@<strong>muohio</strong>.<strong>edu</strong>)<br />

Locating Advantages: <strong>The</strong> Survival <strong>of</strong> the Tuyuhun 吐谷渾 State on the Edge (300-580s)<br />

From the early fourth century, the proto-Mongolian-speaking Särbi (Xianbei 鮮卑 in<br />

Chinese) and four other semi-nomadic peoples—the Xiongnu 匈奴, Jie 羯, Di 氐, and Qiang 羌<br />

—established a series <strong>of</strong> states in north and northwest China. One <strong>of</strong> these states was Tuyughghun,<br />

or Tuyuhun in Chinese, which was established by a branch <strong>of</strong> the Murong 慕容 Särbi and<br />

located in present Qinghai 青海. While most other states lasted no more than a couple <strong>of</strong><br />

generations and the Dai 代 state <strong>of</strong> the Tabgatch (Ch. Tuoba 拓跋) Särbi went on to establish the<br />

Northern Wei 魏 dynasty (386-534), Tuyuhun was successful in transforming itself from a clanbased<br />

polity into a dynastic power that survived into the Sui 隋 dynasty (581-617). Although<br />

severely defeated by the Sui in 609, it recovered its territory with the collapse <strong>of</strong> the Sui and rose<br />

as a considerable power in the early Tang period (618-907), only to be conquered by the newly<br />

risen Tibetan empire in 663. Its history lasted for 350 years.<br />

Exploring why Tuyuhun was able to keep its ethnic and political identity for so long, this<br />

article asserts that Tuyuhun’s geographical location and ecological conditions on the<br />

northeastern Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau placed it in a relatively advantageous position. It enabled<br />

the Tuyuhun to develop a mixed economy <strong>of</strong> herding, farming, handicraft, and trade. It provided<br />

the space the Tuyuhun needed to evolve into an aristocratic, semi-nomadic power that ruled over<br />

a variety <strong>of</strong> ethnic peoples. It situated Tuyuhun on the edge <strong>of</strong> the core regions that were in<br />

competition with one another during the Period <strong>of</strong> Division: north China, south China, the Hexi<br />

corridor, the Mongolian steppes, and the Western Regions. <strong>The</strong>ir distance from these powers<br />

protected the Tuyuhun from destruction or incorporation, enabling their self-preservation,<br />

providing the Tuyuhun with space to retreat to and to expand and to exercise a multilateral form<br />

<strong>of</strong> diplomacy. Furthermore, Tuyuhun’s control over the Qinghai road, a branch <strong>of</strong> the Silk Road<br />

south <strong>of</strong> the Hexi corridor route, raised its status as a crucial intermediary for trade and regional<br />

diplomacy during the Period <strong>of</strong> Division (220-589) when the Hexi corridor route suffered from<br />

political instability.<br />

However, the Qinghai location in the end worked against the Tuyuhun when China and<br />

Tibet each became a unified power, and Tuyuhun was caught between them, leading to its land<br />

annexed by the Tibetan empire.<br />

In his study <strong>of</strong> the relationship between Inner Asia and China, Thomas Barfield has<br />

identified four key ecological and cultural areas: Mongolia, north China, Manchuria, and<br />

Turkestan. His paradigm leaves out Tuyuhun and Tibet. <strong>The</strong> article shows that states such as<br />

Tuyuhun were important players in the political history <strong>of</strong> China and Inner Asia and had ripple<br />

10

effects upon the geopolitics <strong>of</strong> the time. It is not an accident that the Tuyuhun land fell into the<br />

rising Tibetan empire from the 630s. <strong>The</strong>refore, Tuyuhun and Tibet could be added to Barfield’s<br />

analysis as another key ecological and cultural area that played an important role from the early<br />

seventh centuries onwards in China’s frontier relations with Inner Asia.<br />

Daniel Prior, Department <strong>of</strong> History, <strong>Miami</strong> <strong>University</strong> (priordg@<strong>muohio</strong>.<strong>edu</strong>)<br />

Integral or Incidental? Indo-European Mythic Fragments in Inner Asia<br />

In this paper I trace and seek to explain a number <strong>of</strong> thematic parallels between a midnineteenth<br />

century oral epic poem <strong>of</strong> the Kirghiz, entitled Joloy Qan, and two seemingly<br />

unrelated symbolic phenomena: a Hsiung-nu–era Siberian figurative bronze belt buckle plaque<br />

from the Arthur M. Sackler Collections, and a diverse set <strong>of</strong> mythic themes from a broad range<br />

<strong>of</strong> ancient Indo-European traditions. Judging the soundness <strong>of</strong> these correspondences is a matter<br />

<strong>of</strong> methodological and theoretical interest, as they involve ethnolinguistic diversities and spans<br />

<strong>of</strong> time and space on scales that push the bounds <strong>of</strong> plausible reconstruction. <strong>The</strong> movements <strong>of</strong><br />

peoples and ideas suggested by these correspondences conform to some models <strong>of</strong> Inner Asian<br />

prehistory while challenging others.<br />

<strong>The</strong> three items under comparison display “exquisite correspondences,” thematic<br />

parallels the number and narrative precision <strong>of</strong> which would seem to demand some kind <strong>of</strong><br />

explanation besides pure chance. A hero/god figure who is guilty <strong>of</strong> kin killing, breach <strong>of</strong> oath,<br />

and sexual transgressions, goes berserk and kills his own warriors, and decapitates an enemy; his<br />

sister has a sexual liaison with an enemy, and is dragged to death by horses; a young hero/god<br />

(the aforementioned one or his son) is born <strong>of</strong> the waters, has nine joint parents who are siblings,<br />

has sword- and sheep/goat-associations, and lacks a wife: these themes are found in Joloy Qan<br />

and in dispersed remnant form in Norse (Germanic), Roman (Italic), Vedic (Indo-Aryan),<br />

Ossetic (Iranian), and Nuristani (Dardic/Indo-Iranian) traditions. <strong>The</strong> young hero/god, who has a<br />

relationship with a hawk–spirit-maiden, transports his elders in a cart to a land <strong>of</strong> everlasting<br />

happiness: these themes are found in Joloy Qan and the Hsiung-nu belt buckle.<br />

Although the composition <strong>of</strong> the recent Kirghiz epic Joloy Qan is a process about which<br />

very little is known, it seems that some elements <strong>of</strong> the story preserve very ancient narrative<br />

complexes that have elsewhere been scattered almost beyond recognition.<br />

Leland Rogers, Department <strong>of</strong> Anthropology, Indiana <strong>University</strong> (lelroger@indiana.<strong>edu</strong>)<br />

Ancient DNA from the Elite Xiongnu at Ögiinuur Sum, Arkhangai, Mongolia<br />

It has been fairly well established that the Bronze Age inhabitants <strong>of</strong> the Hangai<br />

mountain range in Mongolia were predominantly “Europoid”; the Xiongnu population shows a<br />

substantial mixing. Nine Xiongnu period ancient bone samples from Elite Xiongnu period<br />

burials at Ögiinuur Sum, Arkhangai, have had preliminary testing <strong>of</strong> the HVS 1 region <strong>of</strong> their<br />

mitochondrial DNA. Seven <strong>of</strong> the samples have produced some results. While all the results<br />

must be confirmed, results suggest a higher proportion <strong>of</strong> “Europoid” markers than expected.<br />

<strong>The</strong> region <strong>of</strong> study was chosen due to its relative proximity to the ancient Mongol and Uyghur<br />

capitals, along with its relative proximity to known burials <strong>of</strong> the Xiongnu imperial house. This<br />

is a work in progress <strong>of</strong> 44 Xiongnu period samples from the southeast Hangai range granted by<br />

the National <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Mongolia.<br />

11

Edward Vajda, Department <strong>of</strong> Modern and Classical Languages, Western Washington<br />

<strong>University</strong> (Edward.Vajda@wwu.<strong>edu</strong>)<br />

Between Forest and Steppe: Language and Ethnicity in Early Inner Asia<br />

<strong>The</strong> linguistic identity <strong>of</strong> the earliest pastoral nomads to arise in eastern <strong>Eurasia</strong> – the<br />

Xiongnu and Huns – remains unresolved, and even the origins <strong>of</strong> the later Turks and Mongols<br />

cannot fully be understood by studying the steppes alone. This presentation considers the Kets<br />

and their extinct relatives – the Yugh, Arin, Assan, Kott and Pumpokol – forest tribes living<br />

north <strong>of</strong> the steppe zone in the taiga forest <strong>of</strong> central Siberia. <strong>The</strong>se peoples spoke languages<br />

belonging to the Yeniseian family, which today is represented by only a few elderly speakers <strong>of</strong><br />

the northernmost Ket dialects. Most studies <strong>of</strong> ancient steppe history do not focus attention on<br />

the Yeniseians, who were Siberia’s last hunter-gatherers and never developed, in constrast to the<br />

bettern known steppe pastoralists, large polities or empires beyond their immediate areas <strong>of</strong><br />

habitation. Present-day Turkic and Mongolian territory in or near South Siberia, however,<br />

contain numerous substrate river names <strong>of</strong> Yeniseian origin, suggesting that ancient geographic<br />

contact between taiga hunters and peoples who later expanded through pastoralism were once<br />

quite extensive.<br />

This presentation discusses the Yeniseian family <strong>of</strong> languages by describing what is<br />

known about its former geographic spread and internal dialectal division. Alongside the expected<br />

Turkic loanwords into Yeniseian involving metallurgy or pastoral products, other, presumably<br />

earlier lexical parallels are considered. Ancient Turkic shares with Yeniseian a range <strong>of</strong> words<br />

connected with forest life that can best be explained as Yeniseian substrate loanwords that<br />

entered Turkic before the rise <strong>of</strong> the First Turk Kaganate in the 6 th century AD. <strong>The</strong>se words<br />

reflect a specific Yeniseian dialect (the Ket-Arin branch <strong>of</strong> the family) and some <strong>of</strong> them show<br />

internal structure unique to Yeniseian, so they could not have been borrowed into Yeniseian<br />

from Turkic. This linguistic evidence parallels other facts from substrate river names and human<br />

genetics to suggest that a component <strong>of</strong> early Turkic ethnogenesis derives from Yeniseianspeaking<br />

forest tribes, though this fact became obscured by the subsequent disappearance <strong>of</strong><br />

Yeniseian languages from South Siberia and the adoption <strong>of</strong> Turkic pastoral loanwords into the<br />

Yeniseian dialects that survived farther north in the taiga.<br />

Also discussed are parallels between the Pumpokol branch <strong>of</strong> Yeniseian and the ancient<br />

Xiongnu. <strong>The</strong> scholar Alexander Vovin (2002) already suggested a Yeniseian origin for certain<br />

Xiongnu words. Pumpokol river names in northern Mongolian territory are examined in this<br />

connection. Although the surviving Xiongnu linguistic material is probably too sparse to support<br />

firm conclusions about ethnic and linguistic affiliation, the possibility that at least some elements<br />

within the Xiongnu Confederation spoke a Yeniseian dialect <strong>of</strong> the Pumpokol variety must be<br />

regarded as plausible.<br />

Finally, the presentation considers words common to both Yeniseian and Mongolian<br />

languages that appear to have been borrowed from an early Uralic source. <strong>The</strong>se lexical parallels<br />

suggest that the area south <strong>of</strong> Lake Baikal representing part <strong>of</strong> the homeland <strong>of</strong> the Xiongnu may<br />

have been inhabited in prehistory by people speaking a now extinct branch <strong>of</strong> Uralic. This<br />

suggests another possible linguistic origins for at least some <strong>of</strong> the tribes in the Xiongnu<br />

Confederation. A Uralic linguistic affiliation for the core ethnic element among the Xiongnu has<br />

not been considered previously, but comparative study <strong>of</strong> Yeniseian and Mongolic vocabulary<br />

appears to provide at least circumstantial evidence <strong>of</strong> such a possibility.<br />

12

Robert S. Wicks, <strong>Miami</strong> <strong>University</strong> Art Museum and Department <strong>of</strong> Art (wicksrs@<strong>muohio</strong>.<strong>edu</strong>)<br />

Bird-Headed Antler Tines: Stability and Change in Ancient <strong>Eurasia</strong>n Art"<br />

Although the original meanings ascribed to the bird-headed antler tine motif remain<br />

incompletely understood today, the transmission <strong>of</strong> such a distinctive visual sign over some<br />

4,000 miles <strong>of</strong> sparsely inhabited grasslands among non-literate populations together with its<br />

survival for a period <strong>of</strong> more than four centuries underscore the vitality and innate power <strong>of</strong> its<br />

symbolism. As an art historian I am particularly interested in determining the typological<br />

groupings <strong>of</strong> the material in order to gain a better understanding <strong>of</strong> the motif’s possible origins,<br />

thematic development, and, ultimately, meanings. This paper was inspired by the work <strong>of</strong><br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Esther Jacobson and is given in her honor.<br />

My presentation begins with an examination <strong>of</strong> the major morphological characteristics<br />

<strong>of</strong> the bird-headed antler tine motif and its geographical and temporal horizons within the visual<br />

art traditions <strong>of</strong> <strong>Eurasia</strong> during the second half <strong>of</strong> the first millennium B.C.E. Doubtless inspired<br />

by large birds <strong>of</strong> prey, such as the eagle with its hook-like beak, the bird-headed antler tine motif<br />

displays considerable regional variation. In Scythian art, for example, the cere, the waxy area<br />

around the opening <strong>of</strong> the nostrils, takes on the appearance <strong>of</strong> a duck's bill accompanied by a<br />

dramatic coiling <strong>of</strong> the upper beak. In its easternmost development, among the Xiongnu and<br />

Eastern Han, the bird acquires, in addition to leaf-like ears, a shovel-shaped beak structure<br />

similar to that <strong>of</strong> a flamingo.<br />

<strong>The</strong> main part <strong>of</strong> my presentation introduces an analytical strategy for examining the<br />

typological development <strong>of</strong> the bird-headed antler tine motif in isolated and narrative<br />

representations utilizing Esther Jacobson’s predation/transformation terminology for Scytho-<br />

Siberian art. While these observations and groupings do not necessarily explain the meaning<br />

behind a particular element or motif, they are valuable for pointing out unexpected patterns and<br />

relationships.<br />

13