Bulgaria e-book - iMedia

Bulgaria e-book - iMedia

Bulgaria e-book - iMedia

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

as centres to keep alive the national feeling. At the beginning of the<br />

nineteenth century, when Russia declared war against Turkey (1827),<br />

<strong>Bulgaria</strong> awoke.”<br />

From 1366 to 1827 <strong>Bulgaria</strong> had been enslaved by the Turk. Now<br />

within the space of a few days and with hardly an effort on her own<br />

behalf, she was suddenly to be restored to independence.<br />

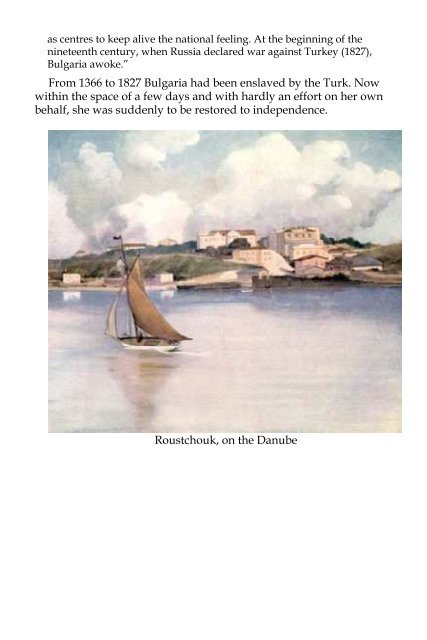

Roustchouk, on the Danube<br />

Chapter V<br />

The Liberation of <strong>Bulgaria</strong><br />

Significantly enough, the first sign of a renaissance of <strong>Bulgaria</strong>n<br />

national feeling was an agitation not against the Turks but the<br />

Greeks. Patriotic <strong>Bulgaria</strong>ns, under the Sublime Porte, sought to<br />

re-establish their old National Church and shake it free from its<br />

subjection to the Greek Patriarch at Constantinople. The Sublime<br />

Porte was induced to look upon this demand with favour. A step<br />

which promised to emphasise the divisions between the Christians<br />

evidently should be of advantage to the Turks. The Greek Patriarch<br />

was urged to consent to the appointment of a <strong>Bulgaria</strong>n bishop. He<br />

refused. In the face of that refusal Turkey acted as the creator of a<br />

new Christian Church, and in 1870 a firman of the Sultan created the<br />

<strong>Bulgaria</strong>n Exarchate, and <strong>Bulgaria</strong> had again a national ecclesiastical<br />

organisation. Two years later the first Exarch was elected by the<br />

<strong>Bulgaria</strong>n clergy. But gratitude for this religious concession did not<br />

extinguish the longings for political independence of the <strong>Bulgaria</strong>n<br />

people. When a Christian insurrection broke out in Herzegovina<br />

against Turkey in 1875, the <strong>Bulgaria</strong>n patriots rose in arms in<br />

different parts of their country. The massacres of Batak were the<br />

Turkish response, those “<strong>Bulgaria</strong>n atrocities” which sent a shudder<br />

through all Europe and set a term to Turkish rule over the Christian<br />

populations in her European provinces.<br />

I have been recently in the Balkans with the veteran war artist,<br />

Mr. Frederick Villiers, who has personal recollections of those times<br />

of massacre and atrocity. Speaking with him, an eye-witness of the<br />

devastation then wrought, it was possible to understand the fierce<br />

indignation with which the English-speaking world was stirred as the<br />

details of the horrors in the Balkans were unveiled. In all about 12,000<br />

<strong>Bulgaria</strong>n people perished, mostly butchered in cold blood. Turkish<br />

anger, it seems, was inflamed against the <strong>Bulgaria</strong>ns, because, in spite<br />

of the recent church concession, some of them had dared to strike for<br />

freedom; and this display of Turkish anger made the full freedom of<br />

<strong>Bulgaria</strong> certain.<br />

At first an attempt had been made by the Powers to exert peaceful<br />

pressure upon Turkey, so that her Christian provinces should be<br />

granted local autonomy. The project of the Powers for <strong>Bulgaria</strong><br />

proposed that the districts inhabited by <strong>Bulgaria</strong>ns should be divided