All Rachmaninoff - Milwaukee Symphony Orchestra

All Rachmaninoff - Milwaukee Symphony Orchestra

All Rachmaninoff - Milwaukee Symphony Orchestra

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

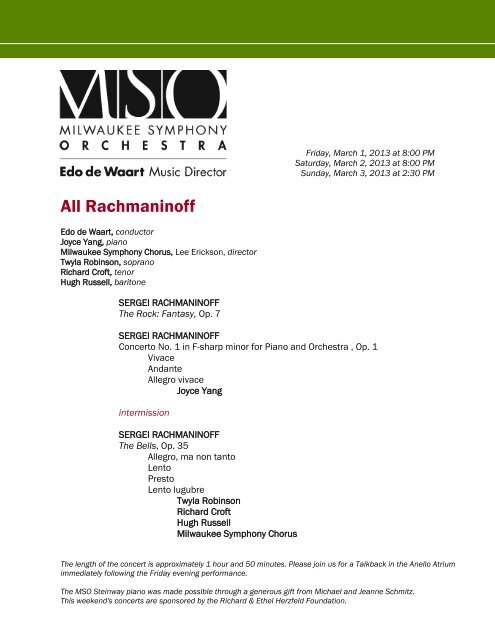

<strong>All</strong> <strong>Rachmaninoff</strong><br />

Edo de Waart, conductor<br />

Joyce Yang, piano<br />

<strong>Milwaukee</strong> <strong>Symphony</strong> Chorus, Lee Erickson, director<br />

Twyla Robinson, soprano<br />

Richard Croft, tenor<br />

Hugh Russell, baritone<br />

SERGEI RACHMANINOFF<br />

The Rock: Fantasy, Op. 7<br />

SERGEI RACHMANINOFF<br />

Concerto No. 1 in F-sharp minor for Piano and <strong>Orchestra</strong> , Op. 1<br />

Vivace<br />

Andante<br />

<strong>All</strong>egro vivace<br />

Joyce Yang<br />

intermission<br />

SERGEI RACHMANINOFF<br />

The Bells, Op. 35<br />

<strong>All</strong>egro, ma non tanto<br />

Lento<br />

Presto<br />

Lento lugubre<br />

Twyla Robinson<br />

Richard Croft<br />

Hugh Russell<br />

<strong>Milwaukee</strong> <strong>Symphony</strong> Chorus<br />

Friday, March 1, 2013 at 8:00 PM<br />

Saturday, March 2, 2013 at 8:00 PM<br />

Sunday, March 3, 2013 at 2:30 PM<br />

The length of the concert is approximately 1 hour and 50 minutes. Please join us for a Talkback in the Anello Atrium<br />

immediately following the Friday evening performance.<br />

The MSO Steinway piano was made possible through a generous gift from Michael and Jeanne Schmitz.<br />

This weekend's concerts are sponsored by the Richard & Ethel Herzfeld Foundation.

2<br />

GUEST ARTIST BIOGRAPHIES<br />

JOYCE YANG<br />

Described as “the most gifted young pianist of her generation” with a “million-volt<br />

stage presence,” pianist Joyce Yang captivates audiences across the globe with her<br />

stunning virtuosity combined with heartfelt lyricism and interpretive sensitivity. At<br />

just 26, she has established herself as one of the leading artists of her generation<br />

through her innovative solo recitals and notable collaborations with the world’s top<br />

orchestras. In 2010 she received an Avery Fisher Career Grant – one of classical<br />

music’s most prestigious accolades.<br />

Yang came to international attention in 2005 when she won the silver medal at the<br />

12th Van Cliburn International Piano Competition. The youngest contestant, she<br />

took home two additional awards: the Steven De Groote Memorial Award for Best Performance of<br />

Chamber Music (with the Takàcs Quartet) and the Beverley Taylor Smith Award for Best Performance of<br />

a New Work.<br />

Since her spectacular debut, Yang has blossomed into an “astonishing artist” (Neue Zürcher Zeitung),<br />

and she continues to appear with orchestras around the world. She has performed with the New York<br />

Philharmonic, Chicago <strong>Symphony</strong>, Los Angeles Philharmonic, Philadelphia <strong>Orchestra</strong>, San Francisco<br />

<strong>Symphony</strong>, Baltimore <strong>Symphony</strong>, Houston <strong>Symphony</strong> and BBC Philharmonic – among many others,<br />

working with such distinguished conductors as Edo de Waart, Lorin Maazel, James Conlon, Leonard<br />

Slatkin, David Robertson and Bramwell Tovey. In recital, Yang has taken the stage at New York’s Lincoln<br />

Center and the Metropolitan Museum; the Kennedy Center in Washington, DC; Chicago’s <strong>Symphony</strong> Hall;<br />

and Zurich’s Tonhalle.<br />

Joyce Yang appears in the film In the Heart of Music, a documentary about the 2005 Van Cliburn<br />

International Piano Competition, and she is a frequent guest on American Public Media’s nationally<br />

syndicated radio program Performance Today. Her debut disc, distributed by harmonia mundi usa,<br />

contains live performances of works by Bach, Liszt, Scarlatti and the Australian composer Carl Vine. A<br />

Steinway artist, she currently resides in New York City.<br />

TWYLA ROBINSON<br />

Twyla Robinson’s incisive musicianship, ravishing vocal beauty and dramatic<br />

delivery have taken her to the leading concert halls and opera stages of<br />

Europe and North America. She has performed with the London <strong>Symphony</strong><br />

<strong>Orchestra</strong>, New York Philharmonic, Berlin Staatskapelle, The Cleveland<br />

<strong>Orchestra</strong>, Philadelphia <strong>Orchestra</strong> and Los Angeles Philharmonic, among<br />

others. She has worked with conductors including Christoph Eschenbach,<br />

Alan Gilbert, Bernard Haitink, Pierre Boulez, Franz Welser-Möst, Donald<br />

Runnicles, Yannick Nézet-Séguin, Esa-Pekka Salonen, Hans Graf and Michael Tilson Thomas.<br />

Recent performances for Ms. Robinson include debuts with the BBC Scottish <strong>Symphony</strong> <strong>Orchestra</strong>,<br />

Toronto <strong>Symphony</strong> <strong>Orchestra</strong> and the Bavarian Radio <strong>Orchestra</strong>. She also made her Opera Colorado<br />

debut as the Countess in Le nozze di Figaro last season. In the summer of 2010, she was seen in a<br />

performance of Mahler’s <strong>Symphony</strong> No. 8 with Jiří Bělohlávek at the opening night of the BBC Proms,<br />

broadcast worldwide on BBC television. She made her Carnegie Hall debut with Robert Spano and the<br />

Atlanta <strong>Symphony</strong> in performances of Leoš Janáček’s Glagolitic Mass and was heard in Zemlinsky’s Lyric<br />

<strong>Symphony</strong> with Christoph Eschenbach and the National <strong>Symphony</strong> and with Yannick Nézet-Séguin and<br />

the Rotterdam Philharmonic.<br />

Upcoming performances for Ms. Robinson include Der Rosenkavalier with Cincinnati Opera in June<br />

2013, Dvořák’s Te Deum with the Dallas <strong>Symphony</strong> in October 2013 and Verdi’s Requiem with Seattle<br />

<strong>Symphony</strong> in November 2013.

3<br />

GUEST ARTIST BIOGRAPHIES<br />

RICHARD CROFT<br />

American tenor Richard Croft is internationally renowned for his performances<br />

with leading opera companies and orchestras around the world, including the<br />

Metropolitan Opera, The Salzburg Festival, Opéra National de Paris, the Berlin<br />

Staatsoper, Opera Zurich, Glyndebourne Festival, The Cleveland <strong>Orchestra</strong>,<br />

Boston <strong>Symphony</strong> <strong>Orchestra</strong> and The New York Philharmonic. His clarion voice,<br />

superlative musicianship and commanding stage presence allow him to pursue<br />

a wide breadth of repertoire from Handel and Mozart to the music of today’s<br />

composers.<br />

Mr. Croft began the 2012.13 season in the title role of Idomeneo with the<br />

Ravinia Festival of which the Chicago Tribune raved, "Friday's opening<br />

performance was dominated by Croft's towering performance as Idomeneo. A deeply expressive singer<br />

and a compelling stage presence, the American tenor caught the heroic, tragic dimension of his role. In<br />

his big showpiece aria in the second act, ‘Fuor del mar,’ he made each embellishment speak volumes<br />

about the terrible emotional conflicts raging within the king." Other operatic highlights included the title<br />

role in La Clemenza di Tito with the Wiener Staatsoper conducted by Adam Fischer. Symphonic<br />

engagements include the world premiere of Jake Heggie’s Ahab <strong>Symphony</strong> at the University of North<br />

Texas, Beethoven’s Missa Solemnis with Leipzig Gerwandhaus and the National <strong>Symphony</strong> <strong>Orchestra</strong>,<br />

Händel’s Messiah with the Singapore <strong>Symphony</strong> and <strong>Rachmaninoff</strong>’s The Bells with the <strong>Milwaukee</strong><br />

<strong>Symphony</strong> conducted by Edo de Waart.<br />

During the 2011.12 season, Richard Croft reprised his critically acclaimed performance as M. K. Gandhi<br />

in the Metropolitan Opera’s visually extravagant production of Philip Glass’s Satygraha, which was also<br />

broadcasted live in high definition to movie theaters around the world. His concert calendar included<br />

performances of Messiah with the Minnesota <strong>Orchestra</strong> and the San Francisco <strong>Symphony</strong>, Berlioz’s Te<br />

Deum with the Dallas <strong>Symphony</strong> and Beethoven’s Missa Solemnis with the Los Angeles Philharmonic<br />

and the Berliner Philharmoniker—both conducted by Herbert Blomstedt.<br />

HUGH RUSSELL<br />

Canadian baritone Hugh Russell continues to receive high praise for his<br />

charisma, dramatic energy and vocal beauty. He is widely acclaimed for his<br />

performances in the operas of Mozart and Rossini, and is regularly invited to<br />

perform with symphony orchestras throughout North America. At the center of<br />

his orchestral repertoire is Orff’s popular Carmina Burana, which Mr. Russell<br />

has performed with The Philadelphia <strong>Orchestra</strong>, The Cleveland <strong>Orchestra</strong>, Los<br />

Angeles Philharmonic, San Francisco <strong>Symphony</strong>, Houston <strong>Symphony</strong>,<br />

Pittsburgh <strong>Symphony</strong>, Seattle <strong>Symphony</strong>, Toronto <strong>Symphony</strong> and Vancouver<br />

<strong>Symphony</strong>, among others.<br />

In the 2012.13 season, Mr. Russell makes his debut with the Danish Radio<br />

<strong>Symphony</strong> in performances of Carmina Burana with Rafael Frühbeck de<br />

Burgos and for his debut with the Naples Philharmonic. Additional<br />

performances include <strong>Rachmaninoff</strong>’s The Bells with the Madison <strong>Symphony</strong> <strong>Orchestra</strong> and his return to<br />

Opera Theatre of St. Louis as General Stanley in The Pirates of Penzance.<br />

Mr. Russell has been seen at the New York City Opera, where he made his company debut singing the<br />

title role in Il barbiere di Siviglia, as well as the Los Angeles Opera, where he sang Harlequin in Ariadne<br />

auf Naxos conducted by Kent Nagano. He was both an Adler Fellow and a member of the Merola Opera<br />

Program at San Francisco Opera, where he was heard in Ariadne auf Naxos and in Messiaen’s St<br />

François d’Assise.

Notes by Roger Ruggeri © 2013<br />

4<br />

The Rock, Opus 7<br />

Sergei <strong>Rachmaninoff</strong><br />

b. April 2, 1873; Novgorod<br />

d. March 28, 1943; Beverly Hills, CA<br />

Written during the summer of 1893, this “fantasia for orchestra” enjoyed its first performance on March 20,<br />

1894 in Moscow, under the direction of Vasili Safonov. Dedicated to Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, the 18-minute<br />

score uses three flutes (third doubling piccolo), two each of oboes, clarinets and bassoons, four horns, two<br />

trumpets, three trombones, tuba, timpani, two percussionists, harp and strings. The music is presented for<br />

the first time on our series.<br />

<strong>Rachmaninoff</strong>’s formative years were difficult, for despite his highly evident musical talents, his adolescence<br />

was blighted by the death of his sister in a diphtheria outbreak, his father’s squandering of the family fortune<br />

and the ultimate separation of his parents. It’s not difficult to imagine him gravitating toward the epic Slavic<br />

melancholy that so often emerges from his music.<br />

Among his earliest such evocations is his tone poem or “fantasia for orchestra,” with the Russian title Utyos, a<br />

term which has been variously translated as “The Rock,” “The Crag” or “The Cliff.” <strong>Rachmaninoff</strong> appended<br />

two lines from a poem by Russian poet Mikhail Lermontov: “The little golden cloud slept through the night /<br />

Upon the chest of the giant crag.”<br />

Also interesting is that five years later, <strong>Rachmaninoff</strong> sent a copy of this score to the revered Russian author<br />

and physician Anton Chekhov with a note saying that it was the author’s story “Along the Way,” that formed a<br />

programmatic basis for his tone poem.<br />

In his Sergei <strong>Rachmaninoff</strong>: A Lifetime in Music, Sergei Bertensson explains:<br />

“Chekhov’s story is set in the travelers’ room of a roadside inn on Christmas Eve, with a blizzard<br />

howling outside. Two travelers, traveling in opposite directions, are detained here: a gruff,<br />

passionate, middle-aged failure (‘the giant crag’) and a delicate and lovely young woman (‘the golden<br />

cloud’). He tells her of his life and beliefs, the emotion in his voice drowning the storm’s roar outside.<br />

In the brightness of Christmas morning she is overcome with pity for him, but has to continue on her<br />

way as he prepares himself for his next painful failure. To read the story as <strong>Rachmaninoff</strong> may have<br />

read it makes us hear all the emotional musical imagery in it—the storm’s angry whistle penetrating<br />

every crack, the bell sounds filtered through the driving snow, the ‘sweet, human music’ of weeping,<br />

and the final picture that sounds as characteristic of <strong>Rachmaninoff</strong> as it does of Checkhov:<br />

Snowflakes settled greedily on his hair, his beard, his shoulders…soon the imprint of the sleigh<br />

runners vanished, and he himself, covered with snow, gradually assumed the appearance of a white<br />

crag, but his eyes still sought something in the white clouds of the drifts.<br />

…in The Crag he composed a vivid wordless drama.”<br />

Composer Mikhail Ippolitov-Ivanov attended a Moscow musical gathering including both Tchaikovsky and<br />

<strong>Rachmaninoff</strong>. He recalled: “At the close of the evening [<strong>Rachmaninoff</strong>] acquainted us with the newly<br />

completed symphonic poem, The Crag… The poem pleased all very much, especially Peter Ilyich, who was<br />

enthusiastic over its colorfulness. The performance of The Crag and our discussion of it must have diverted<br />

Peter Ilyich, for his former good-hearted mood came back to him. Tchaikovsky was so pleased with it, in fact,<br />

that he asked for it to play on his planned European tour this season.” (Unfortunately, Tchaikovsky died<br />

before the tour began.)<br />

continued

5<br />

Concerto No. 1 in F-sharp minor, for Piano and <strong>Orchestra</strong>, Opus 1<br />

Sergei <strong>Rachmaninoff</strong><br />

Written in 1890-91, <strong>Rachmaninoff</strong> premiered the first movement as soloist in a Moscow Conservatory<br />

student concert on March 17, 1892. There were subsequent revisions in 1917 and 1919; the present<br />

performance utilizes the more familiar version of 1917. In this 27-minute work, the solo piano is joined by<br />

pairs of flutes, oboes, clarinets and bassoons, four horns, two trumpets, three trombones, timpani, cymbals,<br />

triangle and strings. It was most recently performed on this series in April 2006 with pianist Mikhail Rudy and<br />

conductor Gilbert Varga.<br />

Ranked among the greatest musicians of the early 20th-century, <strong>Rachmaninoff</strong> gained tremendous fame as a<br />

composer, pianist and conductor. His pianistic abilities became legendary, but his late-Romantic<br />

compositions were successful only with the general public. Musical experts tended to sneer at what they<br />

considered to be his old-fashioned emotionalism. Speaking indirectly to these critics, <strong>Rachmaninoff</strong> once<br />

said: “I try to make my music speak simply and directly that which is in my heart at the time I am composing.<br />

If there is love there, or bitterness, or sadness, or religion, these moods become part of my music, and it<br />

becomes either beautiful, or bitter, or sad, or religious. For composing music is as much a part of my living as<br />

breathing and eating. I compose music because I must give expression to my feelings, just as I talk because I<br />

must give utterance to my thoughts.”<br />

<strong>Rachmaninoff</strong> was the son of a wealthy man who, by the time Sergei was nine, managed to deplete his<br />

fortune. Despite the fact that his family was no longer wealthy, <strong>Rachmaninoff</strong> retained the manner and<br />

bearing of a true aristocrat. As a student, he was unexceptional until he entered the Moscow Conservatory in<br />

1885 and the tremendous scope of his talents emerged.<br />

While still a Conservatory student, <strong>Rachmaninoff</strong> began to compose his first major work, the Piano Concerto<br />

in F-sharp minor, in 1890. When he premiered the work as soloist on March 17, 1892, the audience<br />

response was more polite than enthusiastic. Crushed by the failure of his First <strong>Symphony</strong> in 1897, the young<br />

musician entered into a period of depression and apathy toward composition. Only after a series of<br />

treatments by autosuggestion was he able, three years later, to compose his Second Concerto. It was not<br />

until 1917 that he reconsidered the Concerto No. 1. Just before leaving Russia forever, he revised the work,<br />

keeping the original materials, but reshaping structural and orchestration elements. Successful in its new<br />

form, the revision of 1917 is the work that for many years has been known as the Piano Concerto No. 1.<br />

I. Vivace, 4/4. After a few measures of orchestral fanfare, the soloist launches an impetuous series of<br />

descending octaves. Presented by the violins, the first theme is soon taken up by the piano. A scherzando<br />

transition prefaces the arrival of the contrasting second theme in the violins. Following development and<br />

recapitulation, the orchestra sets the stage for an extremely demanding piano cadenza; a brief coda then<br />

brings the movement to a close.<br />

II. Andante, 4/4. A lovely horn solo begins this brief, contemplative movement. Throughout, the piano seems<br />

to be ruminating in romantic solitude, while the orchestra provides respectfully muted comments.<br />

III. Finale: Vivace, 9/8. A middle section, a sentimental interlude lyrically voiced by strings and piano,<br />

contrasts the restlessly capricious mood of the final movement. The coda culminates in a series of rapid<br />

exchanges between piano and orchestra, as the work sprints to its conclusion.<br />

The Bells, <strong>Symphony</strong> for <strong>Orchestra</strong>, Chorus and Solo Voices, Opus 35<br />

Sergei <strong>Rachmaninoff</strong><br />

Written in the first half of 1913, this work was premiered on November 30, 1913, in St. Petersburg’s<br />

Maryinsky Theatre, under the composer’s direction. In addition to Soprano, Tenor and Baritone soloists and<br />

continued

6<br />

mixed chorus, this thirty-five minute work employs and orchestra of three flutes and piccolo, three oboes and<br />

English horn, three clarinets and bass clarinet, three bassoons and contrabassoon, six horns, three<br />

trumpets, three trombones, tuba, timpani, five percussionists (bass drum, cymbals, suspended cymbal, snare<br />

drum, tambourine, tam-tam, triangle, glockenspiel, bells), harp, celesta, upright piano (pianino), organ<br />

(optional) and strings. Zdenek Macal led the most recent series performances of the work in March 1993.<br />

Edgar <strong>All</strong>an Poe (1809-1849) is a particularly attractive figure to American artists, for, in addition to the<br />

intrinsic value of his poems and short stories, he was the first American whose works had a profound<br />

influence in Europe. The musical quality of Poe’s poetry gave it particular appeal to composers. Certainly one<br />

of Poe’s most musical poems is The Bells, written in 1848, just one year before the hard-living poet’s death<br />

(probably from encephalitis). Born of anguished genius, his poem magically evolves with word, rhythm, image<br />

and sound from the silver bells of childhood to the graveside’s clanging iron knell.<br />

Recalling the genesis of his 1913 choral symphony on this poem, <strong>Rachmaninoff</strong> said: “The inspiration for The<br />

Bells came from an unusual source. I had already during the previous summer sketched a plan for a<br />

symphony. Then, one day I received an anonymous letter from one of those people who constantly pursue<br />

artists with their more or less welcome attentions. The sender begged me to read [Constantin] Balmont’s<br />

wonderful [Russian] translation of Edgar <strong>All</strong>an Poe’s poem, ‘The Bells,’ saying that the verses were ideally<br />

suited for a musical setting and would particularly appeal to me. I read the enclosed verses, and decided at<br />

once to use them for a choral symphony. The structure of the poem demanded a <strong>Symphony</strong> in four<br />

movements. Since Tchaikovsky’s example [<strong>Symphony</strong> No. 6, “Pathetiqué”], the idea of a lugubrious and slow<br />

finale, which seemed necessary, held nothing strange. This composition, on which I worked with feverish<br />

ardor, is still the one I like best of all my works; after it comes my ‘Vesper Mass’—then there is a long gap<br />

between it and the rest. But this is only by the way.”<br />

In his biography of the composer, <strong>Rachmaninoff</strong>—The Man and His Music (Oxford University Press, NY, 1950),<br />

John Culshaw writes:<br />

Ironically, it was this work, more than any other, that caused the Soviet attack of 1931. Pravda, in<br />

that year, published a bitter article describing the composer as “the former bard of the Russian<br />

wholesale merchants and the bourgeoisie—a composer who was played out long ago and whose<br />

music is that of an insignificant imitator and reactionary.” Edgar <strong>All</strong>an Poe, who wrote the famous<br />

text, is very gently treated in comparison with the unfortunate Balmont, who is called “half-idiotic,<br />

decadent, and mystical.” Whether, in view of <strong>Rachmaninoff</strong>’s recent acquittal by the Soviet<br />

authorities, The Bells is among those works now reinstated in the U.S.S.R. is unknown. In any case,<br />

its lavish scoring has proved an obstacle to its regular performance anywhere.<br />

Poe’s poem is far too well known to call for any lengthy comment, but it must be remembered that<br />

<strong>Rachmaninoff</strong>’s music is based on Balmont’s version of the words, which differ considerably from the<br />

original. The difference is interesting and revealing; the original is a masterly piece of imagination,<br />

vivid, strong, and a fearfully objective as the bells whose spirit it seems to capture.… Balmont’s<br />

version is more of a paraphrase taking for its basis only the superficial story and the birth-death<br />

symbolism of Poe’s original. Where Poe is bitter and objective, Balmont is melodramatic and tending<br />

toward subjectivity.<br />

It says much for <strong>Rachmaninoff</strong> in that his setting reaches at times a degree of imagination worthy of<br />

the original. The poem is clothed in music of remarkable power, and the setting is only a failure on<br />

one point—it loses at once the urge, the unfailing progress of the original poem. The Bells as a poem<br />

is short not in length but in the terrible, almost hysterical momentum with which it carries the reader<br />

from the naïve opening to the cynical fatalism of the end. Balmont lost that momentum in a welter of<br />

melodrama, and <strong>Rachmaninoff</strong> nearly, but not quite, restored it. He maintains the tension and<br />

excitement by his use of the chorus, which for the larger part of the work is the most important<br />

continued

7<br />

factor, even when supporting the soloists, whose words it echoes with quiet, penetrating insistence.<br />

It is fascinating that this work was largely composed while the composer and his family were on an extended<br />

vacation in Rome; <strong>Rachmaninoff</strong> worked in the same apartment on the Piazza di Spagna that was once<br />

occupied by Modest Tchaikovsky, and was often visited by his brother, the famed composer Peter Ilyich.<br />

In four movements, corresponding to the four stanzas of Poe’s poem, The Bells begins with an <strong>All</strong>egro ma non<br />

tanto that features solo tenor. With soprano solo, the second movement is slow (Lento); the third is a large<br />

scherzo (Presto) and the finale features solo baritone in another slow movement, Lento lugubre.<br />

These performances will utilize Belmont’s Russian translation, for this is the way that <strong>Rachmaninoff</strong> originally<br />

composed the work. When the composer conducted this work in Chicago in 1941, he requested that the<br />

program contain Poe’s original poem; here, therefore, is that original poem:<br />

The Bells<br />

Edgar <strong>All</strong>an Poe<br />

I<br />

Hear the sledges with the bells—<br />

Silver bells!<br />

What a world of merriment their melody foretells!<br />

How they tinkle, tinkle, tinkle,<br />

In the icy air of night!<br />

While the stars, that oversprinkle<br />

<strong>All</strong> the heavens, seem to twinkle<br />

With a crystalline delight,<br />

Keeping time, time, time,<br />

In a sort of Runic rhyme,<br />

To the tintinnabulation that so musically wells<br />

From the bells, bells, bells, bells,<br />

Bells, bells, bells—<br />

From the jingling and the tinkling of the bells.<br />

II<br />

Hear the mellow wedding bells,<br />

Golden bells!<br />

What a world of happiness their harmony foretells!<br />

Through the balmy air of night<br />

How they ring out their delight!<br />

From the molten-golden notes,<br />

And all in tune,<br />

What a liquid ditty floats<br />

The turtle-dove that listens, while she gloats<br />

On the moon!<br />

Oh, from out the sounding cells,<br />

What a gust of euphony voluminously wells!<br />

How it swells!<br />

How it dwells<br />

On the Future! how it tells<br />

Of the rapture that impels<br />

To the swinging and the ringing<br />

continued

8<br />

Of the bells, bells, bells,<br />

Of the bells, bells, bells, bells,<br />

Bells, bells, bells—<br />

To the rhyming and the chiming of the bells!<br />

III<br />

Hear the loud alarum bells—<br />

Brazen bells!<br />

What a tale of terror, now, their turbulency tells!<br />

In the startled ear of night<br />

How they scream out their affright!<br />

Too much horrified to speak,<br />

They can only shriek, shriek,<br />

Out of tune,<br />

In clamorous appealing to the mercy of the fire,<br />

In a mad expostulation with the deaf and frantic fire,<br />

Leaping higher, higher, higher,<br />

With a desperate desire,<br />

And a resolute endeavour<br />

Now—now to sit or never,<br />

By the side of the pale-faced moon.<br />

Oh, the bells, bells, bells!<br />

What a tale their terror tells<br />

Of despair!<br />

How they clang, and clash, and roar!<br />

What a horror they outpour<br />

On the bosom of the palpitating air!<br />

Yet the ear it fully knows,<br />

By the twanging,<br />

And the clanging,<br />

How the danger ebbs and flows;<br />

Yet the ear distinctly tells,<br />

In the jangling,<br />

And the wrangling,<br />

How the danger sinks and swells,<br />

By the sinking of the swelling in the anger of the bells—<br />

Of the bells—<br />

Of the bells, bells, bells, bells,<br />

Bells, bells, bells—<br />

In the clamour and the clangour of the bells!<br />

IV<br />

Hear the tolling of the bells—<br />

Iron bells!<br />

What a world of solemn thought their monody compels<br />

In the silence of the night,<br />

How we shiver with affright<br />

At the melancholy menace of their tone!<br />

For every sound that floats<br />

From the rust within their throats<br />

Is a groan.<br />

continued

9<br />

And the people—ah, the people—<br />

They that dwell up in the steeple,<br />

<strong>All</strong> alone,<br />

And who tolling, tolling, tolling,<br />

In that muffled monotone,<br />

Feel a glory in so rolling<br />

On the human heart a stone—<br />

They are neither man nor woman—<br />

They are neither brute nor human—<br />

They are Ghouls:<br />

And their king it is who tolls;<br />

And he rolls, rolls, rolls,<br />

Rolls<br />

A paean from the bells!<br />

And his merry bosom swells<br />

With the paean of the bells!<br />

And he dances and he yells;<br />

Keeping time, time, time,<br />

In a sort of Runic rhyme,<br />

To the paean of the bells—<br />

Of the bells:<br />

Keeping time, time, time<br />

In a sort of Runic rhyme,<br />

To the throbbing of the bells,<br />

Of the bells, bells, bells—<br />

To the sobbing of the bells;<br />

Keeping time, time, time,<br />

As he knells, knells, knells,<br />

In a happy Runic rhyme,<br />

To the rolling of the bells—<br />

Of the bells, bells, bells,—<br />

To the tolling of the bells,<br />

Of the bells, bells, bells, bells,<br />

Bells, bells, bells,<br />

To the moaning and the groaning of the bells.<br />

In order to perform the music in English, Fanny S. Copeland created this translation from Konstantin<br />

Balmont’s Russian text:<br />

I<br />

Listen, hear the silver bells!<br />

Silver bells!<br />

Hear the sledges with the bells,<br />

How they charm our weary senses with a sweetness that compels,<br />

In the ringing and the singing that of deep oblivion tells.<br />

Hear them calling, calling, calling,<br />

Rippling sounds of laughter, falling<br />

On the icy midnight air;<br />

And a promise they declare,<br />

That beyond Illusion’s cumber,<br />

Births and lives beyond all number,<br />

continued

10<br />

Waits an universal slumber—deep and sweet past all compare.<br />

Hear the sledges with the bells,<br />

Hear the silver-throated bells;<br />

See, the stars bow down to hearken, what their melody foretells,<br />

With a passion that compels,<br />

And their dreaming is a gleaming that a perfumed air exhales,<br />

And their thoughts are but a shining,<br />

And a luminous divining<br />

Of the singing and the ringing, that a dreamless peace foretells.<br />

II<br />

Hear the mellow wedding bells,<br />

Golden bells!<br />

What a world of tender passion their melodious voice foretells!<br />

Through the night their sound entrances,<br />

Like a lover’s yearning glances,<br />

That arise<br />

On a wave of tuneful rapture to the moon within the skies.<br />

From the sounding cells upwinging<br />

Flash the tones of joyous singing<br />

Rising, falling, brightly calling; from a thousand happy throats<br />

Roll the glowing, golden notes,<br />

And an amber twilight gloats<br />

While the tender vow is whispered that great happiness foretells,<br />

To the rhyming and the chiming of the bells, the golden bells!<br />

III<br />

Hear them, hear the brazen bells,<br />

Hear the loud alarum bells!<br />

In their sobbing, in their throbbing what a tale of horror dwells!<br />

How beseeching sounds their cry<br />

‘Neath the naked midnight sky,<br />

Through the darkness wildly pleading<br />

In affright,<br />

Now approaching, now receding<br />

Rings their message through the night.<br />

And so fierce is their dismay<br />

And the terror they portray,<br />

That the brazen domes are riven, and their tongues can only speak<br />

In a tuneless, jangling wrangling as they shriek, and shriek, and shriek,<br />

Till their frantic supplication<br />

To the ruthless conflagration<br />

Grows discordant, faint and weak.<br />

But the fire sweeps on unheeding,<br />

And in vain is all their pleading<br />

With the flames!<br />

From each window, roof and spire,<br />

Leaping higher, higher, higher,<br />

Every lambent tongue proclaims:<br />

I shall soon,<br />

Leaping higher, still aspire, till I reach the crescent moon;<br />

continued

11<br />

Else I die of my desire in aspiring to the moon!<br />

O despair, despair, despair,<br />

That so feebly ye compare<br />

With the blazing, raging horror, and the panic, and the glare,<br />

That ye cannot turn the flames,<br />

As your unavailing clang and clamour mournfully proclaims.<br />

And in hopeless resignation<br />

Man must yield his habitation<br />

To the warring desolation!<br />

Yet we know<br />

By the booming and the clanging,<br />

By the roaring and the twanging,<br />

How the danger falls and rises like the tides that ebb and flow.<br />

And the progress of the danger every ear distinctly tells<br />

By the sinking and the swelling in the clamour of the bells.<br />

IV<br />

Hear the tolling of the bells,<br />

Mournful bells!<br />

Bitter end to fruitless dreaming their stern monody foretells!<br />

What a world of desolation in their iron utterance dwells!<br />

And we tremble at our doom,<br />

As we think upon the tomb,<br />

Glad endeavour quenched for ever in the silence and the gloom.<br />

With persistent iteration<br />

They repeat their lamentation,<br />

Till each muffled monotone<br />

Seems a groan,<br />

Heavy, moaning,<br />

Their intoning,<br />

Waxing sorrowful and deep,<br />

Bears the message, that a brother passed away to endless sleep.<br />

Those relentless voices rolling<br />

Seem to take a joy in tolling<br />

For the sinner and the just<br />

That their eyes be sealed in slumber, and their hearts be turned to dust<br />

Where they lie beneath a stone.<br />

But the spirit of the belfry is a sombre fiend that dwells<br />

In the shadow of the bells,<br />

And he gibbers, and he yells,<br />

As he knells, and knells, and knells,<br />

Madly round the belfry reeling,<br />

While the giant bells are pealing.<br />

While the bells are fiercely thrilling,<br />

Moaning forth the word of doom,<br />

While those iron bells, unfeeling,<br />

Through the void repeat the doom:<br />

There is neither rest nor respite, save the quiet of the tomb!<br />

■