contemplation - Milwaukee Symphony Orchestra

contemplation - Milwaukee Symphony Orchestra

contemplation - Milwaukee Symphony Orchestra

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

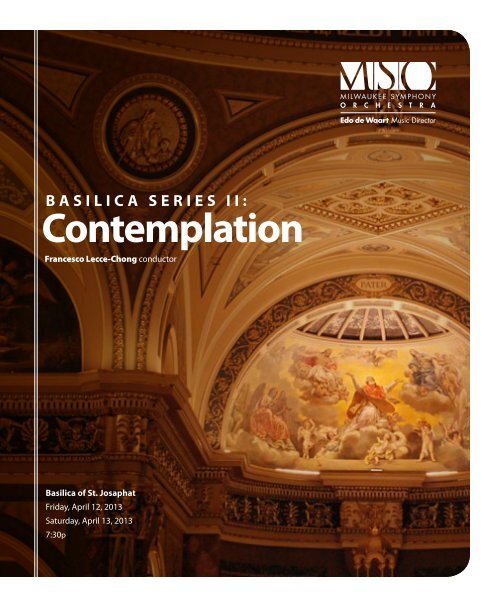

Basilica Series II:<br />

Contemplation<br />

Francesco<br />

Lecce-Chong conductor<br />

Basilica of St. Josaphat<br />

Friday, April 12, 2013<br />

Saturday, April 13, 2013<br />

7:30p

Basilica Series II:<br />

Contemplation<br />

Friday<br />

April 12, 2013 at 7:30 pm<br />

Saturday April 13, 2013 at 7:30 pm<br />

<strong>Milwaukee</strong> <strong>Symphony</strong> <strong>Orchestra</strong><br />

Francesco Lecce-Chong conductor<br />

Welcome<br />

Thank you for joining the <strong>Milwaukee</strong> <strong>Symphony</strong> <strong>Orchestra</strong> for our 2012.13 Basilica Series.<br />

Having had the opportunity to conduct several performances in the Basilica Series last<br />

season, I used the space itself as my primary source of inspiration in planning these<br />

concerts. When I first enter the Basilica, I am always awe-struck by the expansiveness and<br />

grandeur surrounding me. However, as I sit in quiet <strong>contemplation</strong>, the space begins to feel<br />

more intimate, and I become more aware of the sacred and profound aspects. It is amazing<br />

how such a huge external space can inspire internal reflection.<br />

With that in mind, our three programs this season explore the composer as philosopher.<br />

Most orchestral works bear such non-descript titles as “<strong>Symphony</strong>” and “Concerto,” making<br />

it easy to forget that compositions are never written solely as entertainment for the listener.<br />

Like writers and artists, every work is a composer’s personal statement. Through music,<br />

many composers comment on the philosophical issues of their days, such as the search<br />

HAYDN<br />

Intermission<br />

The Seven Last Words of Christ on the Cross<br />

Introduction<br />

Sonata I — “Father, forgive them; for they do not know what they are doing.”<br />

Sonata II — “Truly I tell you, today you will be with me in Paradise.”<br />

Sonata III — “Woman, here is your son.”<br />

Sonata IV — “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?”<br />

Sonata V — “I thirst.”<br />

Sonata VI — “It is finished.”<br />

Sonata VII — “Father, into your hands I commend my spirit.”<br />

The Earthquake<br />

for happiness, the fear of death or the existence of God.<br />

IVES<br />

The Unanswered Question<br />

The music I have chosen for these programs reflects a great variety of styles from composers<br />

both popular and neglected, but these pieces represent some of the most intensely personal<br />

WAGNER<br />

Prelude and “Liebestod” from Tristan und Isolde<br />

works from the composer. The musicians and I are very excited to share this special journey<br />

with you, and we hope you will find our programs invigorating for your mind and soul alike.<br />

Sincerely,<br />

Francesco Lecce-Chong<br />

MSO Associate Conductor<br />

The length of the concert is approximately 1 hour 50 minutes.<br />

<strong>Milwaukee</strong> <strong>Symphony</strong> <strong>Orchestra</strong> can be heard on Naxos, Telarc, Koss Classics, Pro Arte, AVIE, and Vox/Turnabout recordings. MSO Classics recordings (digital only)<br />

available on iTunes and at mso.org. MSO Binaural recordings (digital only) are available at mso.org.<br />

3

About the Artists<br />

Conductor’s Insight by Francesco Lecce-Chong<br />

Francesco Lecce-Chong<br />

Conductor<br />

American conductor Francesco Lecce-Chong, currently Associate Conductor of the<br />

<strong>Milwaukee</strong> <strong>Symphony</strong> <strong>Orchestra</strong> (MSO), is active with the orchestral and operatic<br />

repertories on the international stage. In his role with the MSO, Mr. Lecce-Chong works closely<br />

with renowned Music Director Edo de Waart and is directly responsible for leading over forty<br />

subscription, tour, education and community concert performances annually. During the MSO’s<br />

2012.13 season, Mr. Lecce-Chong has taken the podium for an acclaimed gala concert with Itzhak<br />

Perlman, led the orchestra through its statewide tour of Wisconsin and conducted a special<br />

three-week series at <strong>Milwaukee</strong>’s Basilica of St. Josaphat.<br />

A list of Mr. Lecce-Chong’s international appearances include leading the Hong Kong Philharmonic<br />

<strong>Orchestra</strong> (China), Pitesti Philharmonic (Romania), Ruse Philharmonic, (Bulgaria), and the Sofia<br />

Festival <strong>Orchestra</strong> (Italy). Equally at ease in the opera house, Mr. Lecce-Chong has served as principal<br />

conductor for the Brooklyn Repertory Opera and as staff conductor and pianist for the Santa Fe<br />

Opera. He has earned a growing reputation and critical acclaim for dynamic, forceful performances<br />

that have garnered national distinction. Mr. Lecce-Chong is a 2012 recipient of The Solti Foundation<br />

Career Assistance Award and The Presser Foundation Presser Music Award. He is also the recipient<br />

of the N.T. Milani Memorial Conducting Fellowship and the George and Elizabeth Gregory Award for<br />

Excellence in Performance.<br />

As a trained pianist and composer, Mr. Lecce-Chong embraces innovate programming, champions<br />

the work of new composers and, by example, supports arts education. His 2012.13 season<br />

presentations include two MSO commissioned works, two United States premieres and twelve<br />

works by composers actively working worldwide. He brings the excitement of new music to<br />

audiences of all ages through special presentations embodying diverse program repertoire and<br />

the use of unconventional performance spaces. Mr. Lecce-Chong also provides artistic leadership<br />

for the MSO’s nationally lauded Arts in Community Education (ACE) program — one of the largest<br />

arts integration programs in the country. He is a frequent guest speaker at organizations around<br />

<strong>Milwaukee</strong> and hosts, Behind the Notes, the MSO’s preconcert lecture series.<br />

Mr. Lecce-Chong is a native of Boulder, Colorado, where he began conducting at the age of sixteen.<br />

He is a graduate of the Mannes College of Music, where he received his Bachelor of Music degree<br />

with honors in piano and orchestral conducting. Mr. Lecce-Chong also holds a diploma from the<br />

Curtis Institute of Music, where he studied as a Martin and Sarah Taylor Fellow with renowned<br />

pedagogue Otto-Werner Mueller. He currently resides in <strong>Milwaukee</strong>, Wisconsin.<br />

Follow his blog, Finding Exhilaration, at www.lecce-chong.com<br />

Throughout history,<br />

composers have explored<br />

the philosophical issues of their<br />

day through music. Two famous<br />

examples come from Mozart<br />

and Beethoven. Mozart’s opera,<br />

The Magic Flute is based on<br />

Masonic principals and in<br />

Beethoven’s immortal Ninth<br />

<strong>Symphony</strong>, the “Ode to Joy”<br />

embraces the unifying outlook<br />

of Friedrich Schiller. This<br />

weekend, I am delighted to<br />

share with you three other<br />

important works that ask for our<br />

<strong>contemplation</strong> of their message.<br />

Hadyn: The Seven Last Words of Christ on the Cross<br />

Up until about 1850, most philosophical movements centered on religion and<br />

humankind’s relationship with God. Almost all music written at that time<br />

expressed the same, with the exception of the absolute music of symphonies<br />

and concerti which were based on musical form. Not being one of the latter,<br />

The Seven Last Words of Christ on the Cross is Haydn’s masterful meditation on<br />

the last sayings of Jesus. We are fortunate to have some wonderful insight from<br />

Haydn himself about the inception of the work:<br />

Some fifteen years ago I was requested by a canon of Cádiz to compose<br />

instrumental music on the seven last words of Our Savior on the Cross.<br />

It was customary at the Cathedral of Cádiz to produce an oratorio every year<br />

during Lent, the effect of the<br />

performance being not a little<br />

enhanced by the following<br />

circumstances. The walls,<br />

windows, and pillars of the<br />

church were hung with black<br />

cloth, and only one large lamp<br />

hanging from the center of the<br />

roof broke the solemn darkness.<br />

At midday, the doors were closed<br />

and the ceremony began. After a short service the bishop ascended the pulpit,<br />

pronounced the first of the seven words (or sentences) and delivered a discourse<br />

thereon. This ended, he left the pulpit and fell to his knees before the altar. The<br />

interval was filled by music. The bishop then in like manner pronounced the<br />

second word, then the third, and so on, the orchestra following on the conclusion<br />

of each discourse. My composition was subject to these conditions, and it was<br />

no easy task to compose seven adagios lasting ten minutes each, and to succeed<br />

one another without fatiguing the listeners; indeed, I found it quite impossible to<br />

confine myself to the appointed limits.<br />

FRANZ JOSEPH HAYDN 1732 – 1809<br />

Today, The Seven Last Words of Christ on the Cross is most commonly heard<br />

arranged for string quartet, and during Haydn’s lifetime it was known as an<br />

oratorio with chorus. However, the original version (and the only direct version<br />

4<br />

5

Conductor’s Insight<br />

Conductor’s Insight<br />

in Haydn’s words:<br />

“Each sonata is<br />

expressed by purely<br />

instrumental music in<br />

such a fashion that it<br />

produces the deepest<br />

impression in the<br />

soul even of the most<br />

uninstructed listener.”<br />

…<br />

from Haydn’s hand) from 1801 was written for a standard classical orchestra. Haydn<br />

did not consider it to be concert suitable, and that is partly why this version has<br />

been neglected. He conducted it as an oratorio with chorus many times, because<br />

he considered the original to be more appropriate in its intended environment:<br />

in a church with the text spoken between the movements. I have to admit that<br />

the moment I walked into the Basilica over a year ago, I have been waiting for an<br />

opportunity to bring this work here to recreate Haydn’s first conception.<br />

There are seven “sonatas” that present us with each of the seven sayings. They are<br />

framed by an introductory movement and a final movement, representing the<br />

earthquake. Each of the sonatas’ opening melodic lines coincide rhythmically with<br />

the syllabic underlay of the Latin text of each of the last words. Haydn included the<br />

text in the score to make his intent perfectly clear:<br />

F. Holland Day, The Seven Last Words of Christ, 1898, Prints & Photographs Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.<br />

The Seven Last Words of Christ on the Cross English with Latin text<br />

forgiveness<br />

I. When they came to the place that is called The Skull, they crucified Jesus there with the criminals,<br />

one on his right and one on his left. Then Jesus said, “Father, forgive them; for they do not know<br />

what they are doing.”<br />

Pater, dimitte illis, quia nesciunt, quid faciunt. Luke 23:34<br />

from the opening of Sonata I<br />

Haydn employed a remarkable number of compositional tactics to keep the listener engaged<br />

for the entire hour-long duration of the work. His orchestration demonstrates careful planning<br />

in the occasional use of flutes and extra horns, in order to save the trumpets and timpani until<br />

the final earthquake. His technique varies greatly, ranging from empty unisons to delicate<br />

melodies to thick, pounding chords. He even pushed the boundaries of dissonance and<br />

harmonic cohesion of his time to express the suffering of Christ. One can clearly see how<br />

he cherished this above all his works and it is revolutionary in the way it seeks to inspire the<br />

listener to inward <strong>contemplation</strong>. As Haydn himself noted: “Each sonata is expressed by purely<br />

instrumental music in such a fashion that it produces the deepest impression in the soul even<br />

of the most uninstructed listener.”<br />

salvation<br />

compassion<br />

angst<br />

resignation<br />

credence<br />

acceptance<br />

II. One of the criminals who were hanged there kept deriding him and saying, “Are you not the Messiah?<br />

Save yourself and us!” But the other rebuked him, saying, “Do you not fear God, since you are under<br />

the same sentence of condemnation? And we indeed have been condemned justly, for we are<br />

getting what we deserve for our deeds, but this man has done nothing wrong.” Then he said,<br />

“Jesus, remember me when you come into your kingdom.” He replied, “Truly I tell you, today you<br />

will be with me in Paradise.”<br />

Hodie mecum eris in Paradiso. Luke 23:43<br />

III. When Jesus saw his mother and the disciple whom he loved standing beside her, he said to his<br />

mother, “Woman, here is your son.”<br />

Mulier, ecce filius tuus. John 19: 26 –7<br />

IV. At three o’clock Jesus cried out with a loud voice, “Eloi, Eloi, lema sabachthani?” which means,<br />

“My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?”<br />

Deus meus, Deus meus, utquid dereliquisti me? Mark 15: 34<br />

V. After this, when Jesus knew that all was now finished, he said (in order to fulfill the scripture), “I thirst.”<br />

Sitio. John 19: 28<br />

VI. A jar full of sour wine was standing there. So they put a sponge full of the wine on a branch of hyssop<br />

and held it to his mouth. When Jesus had received the wine, he said, “It is finished.”<br />

Consummatum est. John 19: 30<br />

VII. Then Jesus, crying with a loud voice, said, “Father, into your hands I commend my spirit.” Having said<br />

this, he breathed his last.<br />

In manus tuas, Domine, commendo spiritum meum. Luke 23:46<br />

Haydn with Mozart, his student<br />

6<br />

7

Conductor’s Insight<br />

Conductor’s Insight<br />

Charles Ives 1874 –1954<br />

in ives’s words:<br />

“… as the time goes<br />

on, and after a “secret<br />

conference”, [the<br />

sections] seem to realize<br />

a futility, and begin to<br />

mock “The Question”<br />

— the strife is over for<br />

the moment.”<br />

…<br />

Ives: The Unanswered Question<br />

Subsequently, Romantic era composers would make grand philosophical works like the<br />

Seven Last Words commonplace (think Richard Strauss’ tone poem Also Sprach Zarathustra<br />

or Mahler’s Resurrection <strong>Symphony</strong>). Just a little after that came one of the most effective<br />

works in this genre, The Unanswered Question by Charles Ives. This brief, but evocative piece<br />

was written in 1906 as part of a pair of works titled “Two Contemplations”. There are three<br />

independent sections within the ensemble: strings sustaining ethereal chords, a calmly<br />

melodic solo trumpet and four wind players to contrast the trumpet. Once again, I will let Ives<br />

speak for himself:<br />

The strings are to represent “the Silences of the Druids — Who Know,<br />

See and Hear Nothing.” The trumpet intones “The Perennial Question of<br />

Existence”, and states it in the same tone of voice each time. But the hunt<br />

for “The Invisible Answer” undertaken by the winds, becomes gradually<br />

more active, fast and louder. “The Fighting Answerers”, as the time goes on,<br />

and after a “secret conference”, seem to realize a futility, and begin to mock<br />

“The Question” — the strife is over for the moment. After they disappear,<br />

“The Question” is asked for the last time, and “The Silences” are heard<br />

beyond in “Undisturbed Solitude.”<br />

The piece is vague enough to have puzzled, fascinated and haunted both musicians<br />

and audiences alike for the past century. It even became the title of a series of famous<br />

lectures given by Leonard Bernstein at Harvard on the universality of music.<br />

Leonard Bernstein at Harvard<br />

8<br />

Wagner: Prelude and “Liebestod” from Tristan und Isolde<br />

Richard Wagner<br />

1813 – 1883<br />

In stark contrast to Ives’ compact look at the question of existence,<br />

Wagner’s opera, Tristan and Isolde, is a four-hour long epic on<br />

the same question (and one could argue that it does no better<br />

at resolving it!). Unfortunately, it is easy to get stuck on the<br />

surface of the storyline with magic potions and love affairs.<br />

However, the plot begins to make more sense when we look<br />

at it through the philosophical lens of Arthur Schopenhauer.<br />

Wagner was immediately taken by Schopenhauer’s idea of<br />

two worlds with which we struggle — one in which we are<br />

consumed by desires and dreams and the other where we<br />

fail against the unknowable reality. So when Tristan and Isolde<br />

seem to be pathetically lamenting their impossible love for hours<br />

on end, it is actually a vehicle for discussion about the two worlds<br />

of human desire and reality.<br />

We finish our concert with the Prelude and “Love-Death” from Tristan<br />

and Isolde — the beginning and the end of the opera. The Prelude<br />

beautifully sets up this opera, giving us the famous “musical question” in the opening cello line and<br />

wind chords. The music then seems to contemplate the question of existence along with us, nearly<br />

finding answers, but<br />

always falling back into<br />

darkness. Suddenly,<br />

the music takes on an<br />

assertive quality when<br />

we reach the “Love-<br />

Death.” It starts with a<br />

far away breath, but<br />

then steadily builds<br />

in intensity. In an<br />

ecstatic trance, Isolde<br />

decides that she would<br />

rather die than give<br />

into the cold reality<br />

of life without Tristan.<br />

Interestingly enough,<br />

Wagner would return<br />

to this same question in Parsifal, but this time the hero chooses to overcome his desires in order to<br />

face reality. So in the end, like any good evening filled with philosophical undertakings, we leave<br />

with more questions than when we started — perhaps only learning that magic potions are best<br />

left untouched.<br />

9

2012.13 <strong>Milwaukee</strong> <strong>Symphony</strong> <strong>Orchestra</strong><br />

edo de waart<br />

Music Director<br />

Polly and Bill Van Dyke<br />

Music Director Chair<br />

FRANCESCO LECCE-CHONG<br />

Associate Conductor<br />

Lee Erickson<br />

Chorus Director<br />

Margaret Hawkins Chorus<br />

Director Chair<br />

Timothy J. Benson<br />

Assistant Chorus Director<br />

First VIOLINS<br />

Frank Almond, Concertmaster<br />

Charles and Marie Caestecker<br />

Concertmaster Chair<br />

Ilana Setapen, Associate Concertmaster<br />

Jeanyi Kim, Associate Concertmaster<br />

Third Chair<br />

Karen Smith<br />

Anne de Vroome Kamerling,<br />

Associate Concertmaster Emeritus<br />

Michael Giacobassi<br />

Peter Vickery<br />

Dylana Leung<br />

Andrea Wagoner<br />

Lynn Horner<br />

Zhan Shu<br />

Margot Schwartz<br />

David Anderson<br />

Robin Petzold**<br />

SECOND VIOLINS<br />

Jennifer Startt, Principal<br />

Timothy Klabunde, Assistant Principal<br />

Taik-ki Kim<br />

Lisa Johnson Fuller<br />

Shirley Rosin<br />

Juliette Williams**<br />

Paul Mehlenbeck<br />

Janice Hintz<br />

Les Kalkhof<br />

Glenn Asch<br />

Mary Terranova<br />

Laurie Shawger<br />

VIOLAS<br />

Robert Levine, Principal<br />

Richard O. and Judith A. Wagner<br />

Family Principal Viola Chair<br />

Wei-ting Kuo, Assistant Principal<br />

Friends of Janet F. Ruggeri Viola Chair<br />

Erin H. Pipal<br />

Sara Harmelink<br />

Larry Sorenson<br />

Nathan Hackett<br />

Norma Zehner<br />

David Taggart<br />

Helen Reich<br />

CELLOS<br />

Susan Babini, Principal<br />

Dorothea C. Mayer Cello Chair<br />

Scott Tisdel, Associate Principal<br />

Peter Szczepanek<br />

Gregory Mathews<br />

Peter J. Thomas<br />

Elizabeth Tuma<br />

Laura Love<br />

Margaret Wunsch<br />

Adrien Zitoun<br />

Kathleen Collisson<br />

BASSES<br />

Zachary Cohen, Principal*<br />

Donald B. Abert Bass Chair<br />

Andrew Raciti, Acting Principal<br />

Rip Prétat, Acting Assistant Principal<br />

Laura Snyder<br />

Maurice Wininsky<br />

Catherine McGinn<br />

Scott Kreger<br />

Roger Ruggeri<br />

HARP<br />

Danis Kelly, Principal<br />

Walter Schroeder Harp Chair<br />

FLUTES<br />

Sonora Slocum, Principal<br />

Margaret and Roy Butter Flute Chair<br />

Jeani Foster, Assistant Principal<br />

Jennifer Bouton<br />

PICCOLO<br />

Jennifer Bouton<br />

OBOES<br />

Katherine Young Steele, Principal<br />

<strong>Milwaukee</strong> <strong>Symphony</strong> <strong>Orchestra</strong> League<br />

Oboe Chair<br />

Martin Woltman, Assistant<br />

Principal Emeritus<br />

Margaret Butler, Acting<br />

Assistant Principal<br />

ENGLISH HORN<br />

Margaret Butler, Acting Philip and<br />

Beatrice Blank English Horn Chair<br />

in memoriam to John Martin<br />

CLARINETS<br />

Todd Levy, Principal<br />

Franklyn Esenberg Clarinet Chair<br />

Kyle Knox, Assistant Principal<br />

Donald and Ruth P. Taylor Assistant<br />

Principal Clarinet Chair<br />

William Helmers<br />

E FLAT CLARINET<br />

Kyle Knox<br />

BASS CLARINET<br />

William Helmers<br />

BASSOONS<br />

Theodore Soluri, Principal<br />

Muriel C. and John D. Silbar Family<br />

Bassoon Chair<br />

Rudi Heinrich, Assistant Principal<br />

Beth W. Giacobassi<br />

CONTRABASSOON<br />

Beth W. Giacobassi<br />

HORNS<br />

Matthew Annin, Principal<br />

Krause Family French Horn Chair<br />

Krystof Pipal, Associate Principal<br />

Dietrich Hemann<br />

Andy Nunemaker French Horn Chair<br />

Darcy Hamlin<br />

Joshua Phillips<br />

TRUMPETS<br />

Dennis Najoom, Co-Principal<br />

Martin J. Krebs Co-Principal<br />

Trumpet Chair<br />

Alan Campbell<br />

Fred Fuller Trumpet Chair<br />

TROMBONES<br />

Megumi Kanda, Principal<br />

Marjorie Tiefenthaler Trombone Chair<br />

Kirk Ferguson, Assistant Principal<br />

BASS TROMBONE<br />

John Thevenet<br />

TUBA<br />

Randall Montgomery, Principal<br />

TIMPANI<br />

Dean Borghesani, Principal<br />

Thomas Wetzel, Associate Principal<br />

PERCUSSION<br />

Thomas Wetzel, Principal<br />

Robert Klieger, Assistant Principal<br />

PIANO<br />

Wilanna Kalkhof<br />

Melitta S. Pick Endowed Chair<br />

PERSONNEL MANAGERS<br />

Linda Unkefer<br />

Rip Prétat, Assistant<br />

LIBRARIAN<br />

Patrick McGinn, Principal Librarian<br />

Anonymous Donor,<br />

Principal Librarian Chair<br />

STAGE & TECHNICAL MANAGER<br />

Kyle Remington Norris<br />

* Leave of Absence 2012.13 Season<br />

** Acting member of the <strong>Milwaukee</strong><br />

<strong>Symphony</strong> <strong>Orchestra</strong> 2012.13 Season<br />

Basilica season finale | 17 + 18 May 2013<br />

Basilica Series III:<br />

Remembrance<br />

Francesco Lecce-Chong conductor | Jennifer Startt violin<br />

Prokofiev Andante, Opus 50 bis, from String Quartet No. 1<br />

Weinberg <strong>Symphony</strong> No. 2 — U.S. Premiere<br />

Vaughan Williams Concerto in D minor for Violin and <strong>Orchestra</strong>,“Concerto accademico”<br />

Vaughan Williams Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis<br />

| 414mso.org<br />

291.7605<br />

10

Connect with us!<br />

MS<strong>Orchestra</strong> | @Milwsymphorch | MS<strong>Orchestra</strong>