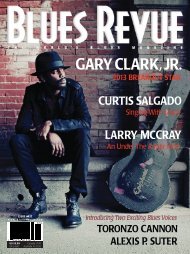

GARY CLARK,JR.

GARY CLARK,JR.

GARY CLARK,JR.

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

When I Left Home: My Story<br />

By Buddy Guy with David Ritz – Da Capo Press<br />

This isn’t the first time Buddy Guy<br />

has hunkered down to commit<br />

his spectacular career to the<br />

printed page. In 1993, he collaborated<br />

with Donald E. Wilcock on<br />

a 1993 memoir, Damn Right, I’ve<br />

Got The Blues, which took an oral<br />

history approach that surrounded<br />

Guy’s own quotes with pertinent<br />

substantiation from various musical<br />

collaborators and personal<br />

friends. While not the ultimate<br />

Guy bio, Damn Right did a reasonable<br />

job of presenting the<br />

highlights of his career at the<br />

flashpoint of what turned out to<br />

be a truly mammoth comeback.<br />

Since then, Guy has been anointed as the contemporary king of<br />

electric Chicago blues. As such a regal status requires, he collaborated<br />

with one of the top biographers in the music field, David Ritz, on When I<br />

Left Home: My Story. Ritz co-authored the autobiographies of Ray<br />

Charles, Aretha Franklin, Marvin Gaye, Smokey Robinson, Jerry Wexler,<br />

the Neville Brothers, the compositional duo of Jerry Leiber and Mike<br />

Stoller, and quite a few more, so he brings major cachet to the project.<br />

Guy and Ritz follow a traditional biographical narrative this time,<br />

tracing Buddy’s life from his rural Louisiana upbringing, where he was<br />

exposed up close and personal to the lowdown blues of Lightnin’ Slim,<br />

through his early musical exploits in Baton Rouge with harpist Raful<br />

Neal and then his September 25, 1957 migration to Chicago. Shy by<br />

nature, the young axeman scuffled at first. Once the mighty Muddy<br />

Waters graciously took Guy under his wing, feeding the starving musician<br />

a salami sandwich outside the 708 Club and offering more nourishment<br />

in the form of much-needed encouragement, Guy’s fortunes<br />

improved in a hurry.<br />

Locating his confidence and bringing an electrifying high-energy<br />

attack to his playing in the manner of his back-home hero Guitar Slim,<br />

Guy made his 1958 recording debut for Cobra Records’ Artistic<br />

imprint. In 1960, he graduated to the Chess label, where Waters,<br />

Howlin’ Wolf, Bo Diddley, and Chuck Berry ruled the roost. Over the<br />

next seven years, Guy earned a vaunted reputation as one of the<br />

most explosive electric fretsmen in his field with a series of blistering<br />

Chess singles (his harrowing vocals were just as exciting). Eric Clapton<br />

and a gaggle of blues-rock icons on both sides of the Atlantic<br />

adopted him as a primary influence.<br />

As he always seems to do in interviews, Guy decries those<br />

seminal Chess waxings here, claiming Leonard Chess prevented him<br />

from recording the way he really wanted to: like an ear-shattering blues<br />

version of Jimi Hendrix. Since Jimi didn’t really emerge on a national<br />

scale until 1967—near the end of Guy’s zChess tenure—that criticism<br />

has limited validity at best. Buddy’s magnificent Chess recordings still<br />

stand as a primary part of his recorded legacy, along with his exquisite<br />

’68 Vanguard LP A Man And The Blues.<br />

There are some convenient omissions in the text. Guy fails<br />

to cite his longtime partner at the Checkerboard Lounge, L.C.<br />

Thurman, or the two managers that guided his comeback campaign,<br />

Marty Salzman and his successor Scott Cameron. Precious<br />

few sidemen rate a mention either. There’s little insight into many of<br />

Guy’s commercially potent recent CDs, which his legion of fans<br />

have purchased in sizable quantities and would seemingly enjoy<br />

reading about.<br />

A disconcerting number of names are misspelled, notably that of<br />

guitarist Pat Hare, whose surname somehow becomes “Hair” (an<br />

account of Hare’s violent deeds is fraught with inaccuracy). A total<br />

lack of vintage photos from Guy’s early performing days is another<br />

disappointment; apart from a striking early picture of his dad, the<br />

entire photo section consists of comparatively recent shots of Buddy-<br />

-either alone, standing next to one celebrity or another (did we really<br />

need a shot of him and Jonny Lang?), or solo shots of Muddy and<br />

John Lee Hooker that seem like padding. Damn Right boasted plenty<br />

of great ‘50s and ‘60s promo pictures of Guy; one wonders why<br />

they’re nowhere to be found this time.<br />

When I Left Home is a snappy read, as one would expect from<br />

anything with Ritz’s name on the cover. It certainly offers a more intimate<br />

and enlightening portrait of Guy’s life and times than its predecessor.<br />

Still, the expectation was for more in-depth testimony from<br />

Chicago’s highest-profile contemporary bluesman. Since it seems<br />

unlikely a third Guy memoir will be forthcoming, we’ll have to content<br />

ourselves with what’s here and let his music say the rest.<br />

– Bill Dahl<br />

Big Road Blues: 12 Bars on I-80<br />

By Mark Hummel<br />

Hop in the van. ‘Cause Mark<br />

Hummel’s going out on tour and<br />

you are invited. But it might not<br />

be quite what you expect. The<br />

perspective of a musician new to<br />

the business changes after a few<br />

tours. That’s according Hummel,<br />

a bandleader who has been on<br />

the road since the late 1970s.<br />

“It’s like breaking the fantasy<br />

of what people think life is<br />

like on the road,” he said. “A<br />

year later, they have a different<br />

take on it.” The unpredictable,<br />

tumultuous, and sometimes<br />

hilarious travails of a professional<br />

musician is detailed in<br />

Hummel’s e-book, Big Road Blues: 12 Bars On I-80,” released in<br />

August. In order to not embarrass some artists, Hummel said he<br />

changed some names in the book. But the stories are true.<br />

Hummel didn’t reveal the identity of a musician who asked to sit<br />

in with the band a few years ago during a show in Oregon. The guitarist,<br />

Hummel surmised in the chapter “Sitting In and Falling Down,”<br />

expected to be turned down. After the bandleader acquiesced, the<br />

nervous guitarist proceeded to get smashed. When he finally got his<br />

chance to play, he was so drunk he fell off the stage. By the time<br />

Hummel’s regular guitar player retrieved his instrument, which was<br />

BLUES REVUE 65