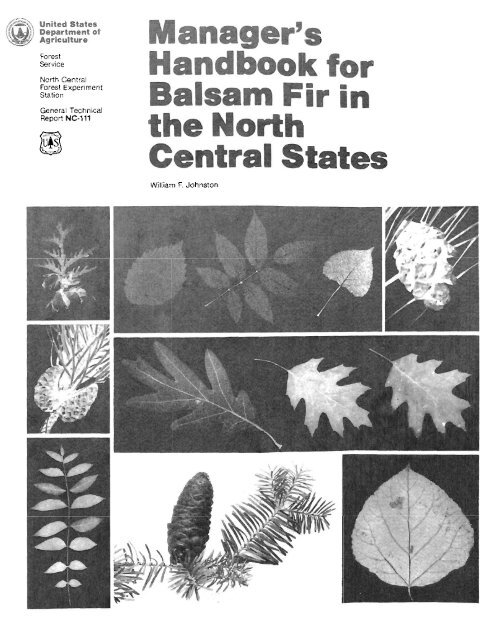

NCSM- Manager's Handbook for Balsam Fir in the Central States

NCSM- Manager's Handbook for Balsam Fir in the Central States

NCSM- Manager's Handbook for Balsam Fir in the Central States

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Forest<br />

Service<br />

North <strong>Central</strong><br />

Forest Experiment<br />

Station<br />

General Technical<br />

Report NC-111<br />

William F. Johnston<br />

I

O<strong>the</strong>r <strong>Manager's</strong> <strong>Handbook</strong>s are:<br />

Jack p<strong>in</strong>e-GTR-NC-32<br />

Red p<strong>in</strong>e-GTR-NC-33<br />

Black spruce-GTR-NC-34<br />

Nor<strong>the</strong>rn white-cedar-GTR-NC-35<br />

Aspen-GTR-NC-36<br />

Oaks-GTR-NC-37<br />

Black walnut-GTR-NC-38<br />

Nor<strong>the</strong>rn hardwoods-GTR-NC-39<br />

Elm-ash-cottonwood-GTR-NC-98<br />

North <strong>Central</strong> Forest Experiment Station<br />

Forest Service-U.S. Department of Agriculture<br />

1992 Folwell Avenue<br />

St. Paul, M<strong>in</strong>nesota 55108<br />

Manuscript approved <strong>for</strong> publication August 27,1986<br />

1986

FOREWORD<br />

This is one ofa series ofmanager's handbooks <strong>for</strong> important <strong>for</strong>est types<br />

<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> North <strong>Central</strong> <strong>States</strong>. The purpose of this series is to present <strong>the</strong><br />

resource manager with <strong>the</strong> latest and best <strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>mation available on manag<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>the</strong>se types. Timber production is dealt with more than o<strong>the</strong>r <strong>for</strong>est<br />

values because it is usually a major management objective and more is<br />

generally known about it. Ways to modify management practices to ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong><br />

or enhance o<strong>the</strong>r values are <strong>in</strong>cluded where sound <strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>mation is<br />

available.<br />

The handbooks have a similar <strong>for</strong>mat, highlighted by a "Key to Recommendations."<br />

Here <strong>the</strong> manager can f<strong>in</strong>d, <strong>in</strong> logical sequence, <strong>the</strong> management<br />

practices recommended <strong>for</strong> various stand conditions. These practices<br />

are based on research, experience, and a general silvical knowledge<br />

of <strong>the</strong> predom<strong>in</strong>ant tree species.<br />

All stand conditions, of course, cannot be <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> handbooks.<br />

There<strong>for</strong>e, <strong>the</strong> manager must use technical skill and sound judgment <strong>in</strong><br />

select<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> appropriate practice to achieve <strong>the</strong> desired objective. The<br />

manager should also apply new research f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs as <strong>the</strong>y become available<br />

so that <strong>the</strong> culture of <strong>the</strong>se important types can be cont<strong>in</strong>ually improved.<br />

The author has, <strong>in</strong> certa<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>stances, drawn freely on unpublished <strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>mation<br />

provided by scientists and managers outside his specialty. He<br />

is also grateful to several resource managers who shared <strong>the</strong>ir knowledge<br />

about <strong>the</strong> balsam fir type dur<strong>in</strong>g field trips and to several technical reviewers<br />

who made many helpful comments. In particular, Thomas R.<br />

Biebighauser of <strong>the</strong> Superior National Forest provided <strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>mation on<br />

manag<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> type <strong>for</strong> wildlife.

CONTENTS<br />

Page<br />

DEFINITION OF TYPE 1<br />

SILVICAL HIGHLIGHTS................................... 1<br />

MANAGEMENT OBJECTIVES AND NEEDS 1<br />

KEY TO RECOMMENDATIONS. .. . . . .. . . . .. . . .. . .. .. . . .. . . 3<br />

TIMBER MANAGEMENT CONSIDERATIONS 4<br />

Controll<strong>in</strong>g Growth '" . . . .. . . 4<br />

Site Productivity 4<br />

Rotation.............................................. 5<br />

Intermediate Treatments 6<br />

Controll<strong>in</strong>g Establishment and Composition . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8<br />

Reproduction Requirements 8<br />

Silvicultural Systems 9<br />

Conversion and Alternat<strong>in</strong>g Crops . 11<br />

Controll<strong>in</strong>g Damag<strong>in</strong>g Agents. .. . 14<br />

Spruce Budworm .. ;................................... 14<br />

Rot and W<strong>in</strong>d 16<br />

O<strong>the</strong>r Agents 17<br />

OTHER RESOURCE CONSIDERATIONS 18<br />

Boughs and Christmas Trees.. . 18<br />

Wildlife Habitat . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18<br />

Es<strong>the</strong>tics 20<br />

Water................................................... 20<br />

APPENDIX. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21<br />

Yield and Growth 21<br />

Site Index 22<br />

TWIGS......... 23<br />

Metric Conversion Factors 24<br />

Common and Scientific Names of Plants and Animals 25<br />

REFERENCES. . . . . . . . . . . . .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 25<br />

PESTICIDE PRECAUTIONARY STATEMENT 27

timber management objective is to grow stands of<br />

even-aged balsam fir that are large enough to be<br />

harvested efficiently with mechanized equipment<br />

but small enough not to be conducive to spruce budworm<br />

attack. Medium-sized stands ofabout 40 acres<br />

usually are recommended. To fur<strong>the</strong>r reduce costs<br />

and <strong>in</strong>crease utilization, <strong>the</strong>se stands need to produce<br />

at least moderate volumes of fir that are harvested<br />

be<strong>for</strong>e fungi appreciably decay or sta<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

wood.<br />

In many parts of <strong>the</strong> nor<strong>the</strong>rn Lake <strong>States</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

balsam fir type is important <strong>for</strong> wildlife habitat, especially<br />

<strong>for</strong> w<strong>in</strong>ter cover. Thus, ano<strong>the</strong>r common objective<br />

is to ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong> or improve <strong>the</strong> type <strong>for</strong> wildlife<br />

while still produc<strong>in</strong>g a moderate, susta<strong>in</strong>ed yield of<br />

merchantable timber. Unless special funds are<br />

available, habitat management will have to be done<br />

through timber management. This will require careful<br />

long-range plann<strong>in</strong>g and coord<strong>in</strong>ated action by<br />

timber and wildlife managers.<br />

The balsamfir type is significantly affected by <strong>the</strong><br />

spruce budworm, rots, and w<strong>in</strong>d. These damag<strong>in</strong>g<br />

agents cause substantial timber losses and, through<br />

tree mortality, can seriously reduce w<strong>in</strong>ter cover or /<br />

es<strong>the</strong>tic values. So, whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> primary objective <strong>in</strong><br />

manag<strong>in</strong>g balsam fir is timber production, wildlife<br />

habitat, or es<strong>the</strong>tics, we need to be able to control<br />

<strong>the</strong>se agents <strong>in</strong> present and future stands.<br />

The best way to manage balsam fir stands <strong>in</strong> terms<br />

of age structure and <strong>in</strong>tensity depends on <strong>the</strong><br />

owner's objective. Even-aged stands are preferred <strong>for</strong><br />

timber and wildlife management; uneven-aged<br />

stands tend to be better where es<strong>the</strong>tic values are<br />

paramount. Because <strong>the</strong> timber value of balsam fir<br />

is usually low, most stands will have to be managed<br />

extensively. However, moderately <strong>in</strong>tensive management<br />

to shorten pulpwood rotations or to produce<br />

small saw logs, <strong>for</strong> example, may be possible where<br />

economic conditions are particularly favorable.<br />

The practices recommended here should lead to<br />

improved management of<strong>the</strong> balsam fir type. Un<strong>for</strong>tunately,<br />

little <strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>mation exists on <strong>the</strong> costs and<br />

returns of us<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>se practices. General comments<br />

about costs are made <strong>in</strong> several <strong>in</strong>stances, but most<br />

economic decisions will have to be based on <strong>the</strong> particular<br />

situation and on <strong>the</strong> manager's experience<br />

and judgment.

istically have a thick layer ofraw humus and a welldef<strong>in</strong>ed<br />

E (<strong>for</strong>merly Az) horizon, which is usually<br />

gray from leach<strong>in</strong>g. Inceptisols <strong>in</strong>clude poorly developed<br />

soils such as those <strong>for</strong>merly called humic gleys.<br />

The latter are generally mottled and are periodically<br />

waterlogged. Histosols are organic soils (peats) that<br />

orig<strong>in</strong>ate under water-saturated conditions.<br />

Site productivity <strong>for</strong> balsam fir is usually expressed<br />

<strong>in</strong> terms ofsite <strong>in</strong>dex, which (along with age)<br />

is needed to determ<strong>in</strong>e yield and growth. <strong>Balsam</strong> fir<br />

site <strong>in</strong>dex is most reliable when estimated from a<br />

site <strong>in</strong>dex equation or from curves based on <strong>the</strong> total<br />

height and total age of dom<strong>in</strong>ant and codom<strong>in</strong>ant<br />

firs grow<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> even-aged stands (see Appendix,<br />

p. 22 and fig. 7). To use <strong>the</strong> equation or curves properly,<br />

trees measured <strong>for</strong> site <strong>in</strong>dex (site trees) should<br />

be un<strong>in</strong>jured dom<strong>in</strong>ant and codom<strong>in</strong>ant firs that are<br />

at least 20 years old and have never been suppressed.<br />

Un<strong>for</strong>tunately, many even-aged stands do not<br />

have suitable site trees <strong>for</strong> balsam fir. The exist<strong>in</strong>g<br />

firs often are not free ofsuppression because <strong>the</strong>y are<br />

ei<strong>the</strong>r overtopped or have developed from <strong>the</strong> understory.<br />

Also, some trees may have been <strong>in</strong>jured <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

past; <strong>for</strong> example, <strong>the</strong>y may have a broken top or be<br />

de<strong>for</strong>med from spruce budworm attack. In <strong>the</strong>se<br />

cases <strong>the</strong> site <strong>in</strong>dex of balsam fir can be estimated<br />

from <strong>the</strong> site <strong>in</strong>dex ofcerta<strong>in</strong> associated species, provided<br />

that at least one has suitable site trees. Comparative<br />

site <strong>in</strong>dexes <strong>for</strong> balsam fir and some common<br />

associates are given <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> follow<strong>in</strong>g<br />

generalized tablulation: 3<br />

<strong>Balsam</strong><br />

fir<br />

60<br />

50<br />

40<br />

30<br />

Quak<strong>in</strong>g Paper<br />

aspen birch<br />

70<br />

60<br />

50<br />

35<br />

(Site <strong>in</strong>dex, feet)<br />

70<br />

55<br />

40<br />

25<br />

Black<br />

spruce<br />

60<br />

50<br />

40<br />

30<br />

Nor<strong>the</strong>rn<br />

white-cedar<br />

40<br />

35<br />

30<br />

25<br />

Site <strong>in</strong>dex measurements are unreliable <strong>in</strong><br />

uneven-aged stands because most trees that appear<br />

suitable probably have been suppressed earlier.<br />

Measurements are also unreliable <strong>in</strong> stands less<br />

than 20 years old (unless quak<strong>in</strong>g aspen or paper<br />

birch is present 4 ) and <strong>in</strong> stands severely disturbed by<br />

harvest<strong>in</strong>g or damag<strong>in</strong>g agents. Under <strong>the</strong>se conditions,<br />

estimate site <strong>in</strong>dex without us<strong>in</strong>g site trees.<br />

3Based on equations from Carmean (1982); see Appendix,<br />

p. 23.<br />

4Site <strong>in</strong>dex curves beg<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g at 10 years ofage are<br />

available <strong>for</strong> quak<strong>in</strong>g aspen (Perala 1977) and paper<br />

birch (Tubbs 1977).<br />

Soil moisture availability and stand composition<br />

<strong>in</strong>dicate general site classes. For example, mesic<br />

sites with a nor<strong>the</strong>rn hardwood component usually<br />

have a balsam fir site <strong>in</strong>dex from 50 to 60, whereas<br />

wet (swamp) sites with a black spruce or nor<strong>the</strong>rn<br />

white-cedar component have a site <strong>in</strong>dex ofabout 35.<br />

In addition, general site classes <strong>for</strong> balsam fir can be<br />

determ<strong>in</strong>ed from soil characteristics as shown <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

follow<strong>in</strong>g tabulation: 5<br />

Site <strong>in</strong>dex Dra<strong>in</strong>age and textural class<br />

60 Well-dra<strong>in</strong>ed loams<br />

50<br />

40<br />

Moderately well-dra<strong>in</strong>ed silt<br />

loams, clay loams, and clays<br />

Well- to poorly dra<strong>in</strong>ed sandy<br />

loams and sands; welldecomposed<br />

peats (mucks)<br />

30 Excessively dra<strong>in</strong>ed sands;<br />

moderately decomposed peats<br />

Fertiliz<strong>in</strong>g probably would <strong>in</strong>crease balsam fir's<br />

growth rate on some sites <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Lake <strong>States</strong>, but no<br />

specific guidel<strong>in</strong>es are available. Gross periodic<br />

growth <strong>in</strong>creased moderately <strong>in</strong> dense, unmanaged,<br />

45- to 60-year-old balsam fir stands <strong>in</strong> eastern<br />

Canada after apply<strong>in</strong>g 150 to 200 pounds per acre of<br />

nitrogen (as urea). Un<strong>for</strong>tunately, tree mortality<br />

was high <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>se stands, so volume losses often exceeded<br />

fertilization ga<strong>in</strong>s. Thus, fertiliz<strong>in</strong>g ofbalsam<br />

fir is· not recommended <strong>in</strong> dense, unmanaged, 45year-old<br />

or older stands. However, some evidence<br />

<strong>in</strong>dicates that nitrogen fertilizer (especially ammonium<br />

nitrate) may be beneficial when applied to<br />

younger stands where stock<strong>in</strong>g has been reduced by<br />

spac<strong>in</strong>g or th<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

Rotation<br />

<strong>Balsam</strong> fir stands break up at fairly young ages<br />

even though <strong>in</strong>dividual trees may live <strong>for</strong> 200 years.<br />

This is because root (or butt) rots beg<strong>in</strong> enter<strong>in</strong>g<br />

balsam fir at about 25 to 30 years; eventually <strong>the</strong><br />

trees are weakened, which leads to severe<br />

w<strong>in</strong>dthrow and w<strong>in</strong>dbreakage.<br />

Root rot beg<strong>in</strong>s sooner on uplands than <strong>in</strong> swamps.<br />

<strong>Balsam</strong> fir stands <strong>in</strong> Michigan's Upper Pen<strong>in</strong>sula<br />

break up at about 70 years on uplands, 80 years on<br />

transition sites, and 90 years <strong>in</strong> swamps. These<br />

pathological rotations are too long, however, <strong>for</strong> timber<br />

management because w<strong>in</strong>d damage and cull are<br />

already substantial by <strong>the</strong>se ages.<br />

For maximum yield and utilization of balsam fir<br />

pulpwood, rotations should be shortened enough to<br />

5Adapted from Bowman (1944).<br />

5

On wet and wet-mesic sites, balsam fir<br />

grow above associated hardwoods;<br />

mesic sites it may become severely supnl"'olJ'QQ£Uof<br />

especially by nor<strong>the</strong>rn hardwoods.<br />

<strong>Balsam</strong> fir generally responds well to release; diameter<br />

growth rate at least doubles with<strong>in</strong> a few<br />

years after release. For best results <strong>the</strong> trees should<br />

be released while <strong>the</strong>y are still young and vigorous.<br />

Indicators of such trees are a current annual height<br />

growth of 6 <strong>in</strong>ches or more, a fairly po<strong>in</strong>ted crown,<br />

and smooth bark with raised res<strong>in</strong> blisters. Older,<br />

severely suppressed trees-current annual height<br />

growth of 1 or 2 <strong>in</strong>ches, flat-topped crowns, and<br />

rough bark-should not be released regardless of<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir size. Even small trees often are old and so respond<br />

poorly to release and have a high <strong>in</strong>cidence of<br />

rot.<br />

In<strong>for</strong>mation from <strong>the</strong> Nor<strong>the</strong>astern <strong>States</strong> <strong>in</strong>dicates<br />

that a s<strong>in</strong>gle release or clean<strong>in</strong>g about 8 years<br />

after f<strong>in</strong>al harvest or when stand height averages<br />

from 6 to 10 feet is usually enough to ensure balsam<br />

fir dom<strong>in</strong>ance. Aerial herbicide spray<strong>in</strong>g is <strong>the</strong> most<br />

practical way to kill back overtopp<strong>in</strong>g shrubs or<br />

hardwoods. Selective herbicides <strong>for</strong> releas<strong>in</strong>g balsam<br />

fir <strong>in</strong>clude 2,4-D, glyphosate (Roundup6), and<br />

triclopyr (Garlon); hexaz<strong>in</strong>one (Velpar) also shows<br />

promise. The most economical herbicide is 2,4-D,<br />

which is effective on quak<strong>in</strong>g aspen, paper birch,<br />

black ash, beaked hazel, speckled alder, and willow.<br />

Glyphosate is effective on a broad spectrum ofwoody<br />

and herbaceous vegetation (<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g grasses, some<br />

sedges, and bracken fern), whereas triclopyr is effective<br />

only on broadleaved species. Glyphosate is especially<br />

useful <strong>for</strong> controll<strong>in</strong>g red raspberry and American<br />

beech; triclopyr is better <strong>for</strong> maples.<br />

At present <strong>the</strong> two most important herbicides <strong>for</strong><br />

releas<strong>in</strong>g balsam fir are 2,4-D and glyphosate. A low<br />

volatile ester of 2,4-D is generally effective when<br />

applied at a total rate of3 pounds acid equivalent <strong>in</strong><br />

at least 4 gallons of water per acre. Spray when <strong>the</strong><br />

new growth of balsam fir has hardened off but<br />

shrubs and hardwoods are still susceptible-from<br />

late July to early August. Glyphosate is effective<br />

when applied at a rate of 1 1 /2 pounds active <strong>in</strong>gredient<br />

<strong>in</strong> at least 5 gallons of water per acre. Spray<br />

be<strong>for</strong>e foliage turns color or frost occurs-late summer<br />

or early fall.<br />

O<strong>the</strong>r herbicides may become available and herbicide<br />

labels are constantly revised. Thus, <strong>the</strong> manager<br />

should be alert to more effective or economical<br />

6Mention of trade names does not constitute endorsement<br />

of<strong>the</strong> products by <strong>the</strong> USDA Forest Service.<br />

herbicides and should always follow specific label<br />

<strong>in</strong>structions. Herbicide spray<strong>in</strong>g should be done<br />

carefully, follow<strong>in</strong>g all pert<strong>in</strong>ent precautions and<br />

regulations (see Pesticide Precautionary Statement,<br />

p. 27). It is particularly important not to contam<strong>in</strong>ate<br />

open water.<br />

Aerial herbicide spray<strong>in</strong>g cannot be used if a<br />

mixed stand with some hardwoods is desited. Instead,<br />

crop trees need<strong>in</strong>g release are selected and<br />

<strong>the</strong>n <strong>in</strong>dividual trees with<strong>in</strong> about 3 feet of<strong>the</strong>m are<br />

ei<strong>the</strong>r treated with herbicide or felled. Although it<br />

costs more than aerial spray<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>in</strong>ject<strong>in</strong>g herbicide<br />

<strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong> stem with a tree <strong>in</strong>jector is more efficient<br />

than fell<strong>in</strong>g with a power brush saw. Herbicide <strong>in</strong>jection<br />

can also be used to kill large, unwanted residual<br />

trees on harvest areas and it is a promis<strong>in</strong>g alternative<br />

to aerial spray<strong>in</strong>g <strong>for</strong> small stands.<br />

The herbicides commonly used <strong>for</strong> <strong>in</strong>jection are<br />

MSMA and Tordon 101 (a comb<strong>in</strong>ation of picloram<br />

and 2,4-D). These herbicides are usually applied<br />

undiluted, us<strong>in</strong>g 1 or 2 milliliters per <strong>in</strong>jection at<br />

about 2-<strong>in</strong>ch <strong>in</strong>tervals around <strong>the</strong> stem. Ano<strong>the</strong>r effective<br />

herbicide <strong>for</strong> <strong>in</strong>jection is glyphosate<br />

(Roundup); as a 20 percent solution <strong>in</strong> water, it<br />

should be <strong>in</strong>jected at <strong>the</strong> rate of2 milliliters per 2 to<br />

3 <strong>in</strong>ches of d.b.h. For safe and efficient use of <strong>the</strong>se<br />

herbicides, always follow specific label <strong>in</strong>structions.<br />

Desirable stand densities are not known <strong>for</strong> optimum<br />

timber growth ofbalsam fir <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Lake <strong>States</strong>.<br />

Densities that favor fast diameter growth are recommended<br />

because <strong>the</strong>y make it possible to grow pulpwood<br />

on shorter rotations or to produce saw logs<br />

be<strong>for</strong>e decay becomes serious. Stock<strong>in</strong>g guides <strong>for</strong><br />

even-aged spruce-balsam fir stands <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Nor<strong>the</strong>astern<br />

<strong>States</strong> provide estimates of desirable densities.<br />

For unmanaged sapl<strong>in</strong>g stands, average number<br />

and spac<strong>in</strong>g of potential crop trees required to<br />

produce at least <strong>the</strong> recommended m<strong>in</strong>imum stock<strong>in</strong>g<br />

of crop trees (curve B <strong>in</strong> fig. 2) are given <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

follow<strong>in</strong>g tabulation: 7<br />

Average stand<br />

diameter<br />

(Inches)<br />

1<br />

2<br />

3<br />

4<br />

Potential crop trees<br />

Number<br />

per acre Spac<strong>in</strong>g<br />

1,650<br />

1,350<br />

1,050<br />

850<br />

(Feet)<br />

5x5<br />

5 1/2 X 5 1/2<br />

6 1/2 X 6 1/2<br />

7x7<br />

A stock<strong>in</strong>g chart can be used to determ<strong>in</strong>e <strong>the</strong><br />

maximum and m<strong>in</strong>imum stock<strong>in</strong>g levels recom-<br />

7Adapted from Frank and Bjorkbom (1973).<br />

7

gradual. Clearcutt<strong>in</strong>g a balsam fir stand that conta<strong>in</strong>s<br />

some aspen, <strong>for</strong> example, often results <strong>in</strong><br />

prompt conversion to aspen by sucker<strong>in</strong>g. Or <strong>the</strong><br />

manager can quickly convert to o<strong>the</strong>r conifers by<br />

plant<strong>in</strong>g after clearcutt<strong>in</strong>g. In contrast, selection<br />

cutt<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>in</strong> a fir stand that conta<strong>in</strong>s nor<strong>the</strong>rn hardwoods<br />

may lead to gradual conversion to sugar<br />

maple and o<strong>the</strong>r tolerant hardwoods. The various<br />

options <strong>for</strong> convert<strong>in</strong>g to or alternat<strong>in</strong>g with o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

types or species should be considered <strong>in</strong> relation to<br />

both short- and long-term objectives. For example,<br />

prompt harvest<strong>in</strong>g after a budworm outbreak to salvage<br />

fir pulpwood can be followed by plant<strong>in</strong>g a longlived<br />

conifer to produce sawtimber.<br />

The opportunities to convert balsam fir to, or alternate<br />

it with, o<strong>the</strong>r types are many and varied<br />

because fir grows under a wide range of conditions<br />

and its seedl<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>for</strong>m an almost ubiquitous understory<br />

<strong>in</strong> many Lake <strong>States</strong> types. Only general<br />

guidel<strong>in</strong>es on conversion and alternat<strong>in</strong>g crops are<br />

presented here. More detailed <strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>mation on associated<br />

types is available <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> follow<strong>in</strong>g references:<br />

Type name<br />

Hardwood types<br />

Aspen<br />

Paper birch<br />

Nor<strong>the</strong>rn hardwoods<br />

P<strong>in</strong>e types<br />

Jack p<strong>in</strong>e<br />

Red p<strong>in</strong>e<br />

Reference 9<br />

Perala 1977<br />

Saf<strong>for</strong>d 1983<br />

Tubbs 1977<br />

Benzie 1977a<br />

Benzie 1977b<br />

Schone et al. 1984<br />

Lancaster and Leak 1978<br />

Eastern white p<strong>in</strong>e lO<br />

Spruce-fir types<br />

Spruce-fir ll Flexner et al. 1983<br />

Frank and Bjorkbom 1973<br />

White spruce ll Stie111976<br />

Black spruce Johnston 1977a<br />

Nor<strong>the</strong>rn white-cedar Johnston 1977b<br />

All types Burns 1983 12<br />

<strong>Balsam</strong> fir and aspen often exist toge<strong>the</strong>r .• and<br />

where <strong>the</strong>y do it is difficult to manage one to <strong>the</strong><br />

exclusion of <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r. <strong>Balsam</strong> fir and paper. birch<br />

are also commonly associated. Even if<strong>the</strong>.ma<strong>in</strong> objective<br />

is to grow balsam fir timber, an aspenor birch<br />

component probably should be ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>for</strong><br />

multiple-use purposes such as wildlife habitat and<br />

es<strong>the</strong>tics. In addition, aspen and birchareimportant<br />

<strong>in</strong> deal<strong>in</strong>g with <strong>the</strong> sprucebudworm.. Bomeaspen<br />

should be present <strong>for</strong> easy conversion by sucker<strong>in</strong>g<br />

12<br />

9For full citations, see Appendix,p.25.<br />

l01ncZudes eastern hemlock <strong>in</strong> Burns·(1983Y<br />

See eastern spruce-fir <strong>in</strong> Burns (19.83).<br />

12Provides up-to-date· summaries.<br />

<strong>in</strong> case of an outbreak, and a birch can<br />

significantly reduce fir mortality. However, if birch<br />

does not <strong>for</strong>m an overstory, fir mortality may be<br />

severe and suddenly expose <strong>the</strong> birch, caus<strong>in</strong>g<br />

dieback and death.<br />

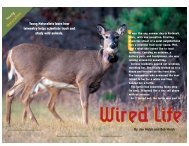

On most sites balsam fir and aspen should be managed<br />

as alternat<strong>in</strong>g crops (fig. 4), whereas balsam fir<br />

and paper birch should be managed toge<strong>the</strong>r. However,<br />

ifhigh-quality logs of nor<strong>the</strong>rn hardwoods, red<br />

p<strong>in</strong>e, or white spruce can be grown on a site (aspen<br />

and paper birch site <strong>in</strong>dexes 60 or more), <strong>the</strong> manager<br />

should consider conversion even though it may<br />

be costly.<br />

In a mature stand of fir with some aspen (at least<br />

18 square feet of basal area per acre), clearcut to<br />

produce a fully stocked stand ofaspen suckers (fig. 4,<br />

left). If fir advance growth is sparse, harvest areas<br />

should be with<strong>in</strong> 2 to 3 cha<strong>in</strong>s of seed-bear<strong>in</strong>g firs<br />

(see p. 10). Once <strong>the</strong> aspen is mature and fir <strong>for</strong>ms an<br />

understory (fig. 4, right), harvest <strong>the</strong> aspen to release<br />

<strong>the</strong> fir. Well-distributed open<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> fir<br />

stand will allow enough aspen suckers to develop so<br />

<strong>the</strong> cycle can be repeated when <strong>the</strong> fir matures.<br />

<strong>Balsam</strong> fir also commonly <strong>for</strong>ms an understory <strong>in</strong><br />

paper birch stands. When <strong>the</strong> birch is mature, it can<br />

be harvested to release <strong>the</strong> fir, just as <strong>in</strong> aspen<br />

stands. To reduce spruce budworm losses, ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong><br />

some overstory birch (or aspen) by clearcutt<strong>in</strong>g progressive<br />

strips or small patches ra<strong>the</strong>r than large<br />

areas. Harvest<strong>in</strong>g must be done carefully to leave an<br />

adequate stock<strong>in</strong>g offir (see p. 10 and 18). To ensure<br />

a birch component <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> new stand, scarify <strong>the</strong> soil<br />

<strong>in</strong> scattered open<strong>in</strong>gs and leave seed-bear<strong>in</strong>g birches<br />

with<strong>in</strong> 3 cha<strong>in</strong>s. Once <strong>the</strong> fir matures, treat <strong>the</strong><br />

stand as described below.<br />

Where mature balsam fir has at least three to five<br />

paper birch seed trees per acre, clearcut <strong>the</strong> stand <strong>in</strong><br />

progressive strips or small patches or use shelterwood<br />

cutt<strong>in</strong>g. Strips should be from 1 to 2 cha<strong>in</strong>s<br />

wide and patches 1 acre or less <strong>in</strong> size. Scarify about<br />

50 percent of <strong>the</strong> harvest area to prepare favorable<br />

seedbeds <strong>for</strong> both fir and birch. Full-tree skidd<strong>in</strong>g<br />

with branches and tops <strong>in</strong>tact prepares favorable<br />

seedbeds when <strong>the</strong> soil is not frozen or covered by<br />

snow. Seedl<strong>in</strong>g reproduction may be supplemented<br />

by vigorous stump sprouts if <strong>the</strong> birch is younger<br />

than 60 years. However, sprouts usually contribute<br />

no more than about 10 percent to birch stock<strong>in</strong>g because<br />

many are elim<strong>in</strong>ated by repeated deer brows<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

The future composition of <strong>the</strong> new stand can be<br />

controlled by releas<strong>in</strong>g potential crop trees about 8<br />

years after f<strong>in</strong>al harvest or when stand height averages<br />

from 6 to 10 feet. To obta<strong>in</strong> a mixed stand <strong>in</strong>

Figure 4.-These views show <strong>the</strong> key steps <strong>in</strong> manag<strong>in</strong>g balsam fir and aspen as alternat<strong>in</strong>g crops: clearcut<br />

mature fir and associated aspen to produce aspen suckers (left),. harvest mature aspen to release fir understory<br />

(right), preferably earlier than shown.<br />

which balsam fir is <strong>the</strong> dom<strong>in</strong>ant species, use <strong>the</strong><br />

guidel<strong>in</strong>es <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> tabulation on page 7, except <strong>in</strong>clude<br />

<strong>the</strong> release of about 150 paper birch per acre.<br />

<strong>Balsam</strong> fir is also commonly associated with<br />

nor<strong>the</strong>rn hardwoods and may even be dom<strong>in</strong>ant <strong>for</strong><br />

a while after disturbance. However, on fertile mesic<br />

sites (well-dra<strong>in</strong>ed loams), fir does not compete well<br />

with long-lived shade-tolerant hardwoods such as<br />

sugar maple. On sites with a sugar maple site <strong>in</strong>dex<br />

of 55 or more, control fir advance growth <strong>in</strong> order to<br />

favor hardwood reproduction and clearcut mature fir<br />

if hardwood advance growth is adequately stocked.<br />

The m<strong>in</strong>imum number per acre of well-spaced hardwoods<br />

should be 5,000 seedl<strong>in</strong>gs 3 to 4 feet tall or<br />

1,000 sapl<strong>in</strong>gs 2 to 4 <strong>in</strong>ches <strong>in</strong> d.b.h. Ifsuch stock<strong>in</strong>g<br />

is lack<strong>in</strong>g, remove <strong>the</strong> fir <strong>in</strong> two or more stages-by<br />

shelterwood cutt<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>for</strong> example-so <strong>the</strong> hardwoods<br />

can become established or better stocked.<br />

On less well-dra<strong>in</strong>ed hardwood sites (sugar maple<br />

site <strong>in</strong>dex less than 55), balsam fir should be managed<br />

along with its associated hardwoods. These <strong>in</strong>clude<br />

yellow birch-plus eastern hemlock <strong>in</strong> Michigan<br />

and Wiscons<strong>in</strong>-on somewhat poorly dra<strong>in</strong>ed<br />

sites and black ash and red maple on poorly dra<strong>in</strong>ed<br />

sites. To grow only pulpwood, reproduce all species<br />

when <strong>the</strong> fir is mature (about age 50); use clearcutt<strong>in</strong>g<br />

where fir advance growth is adequately stocked<br />

and shelterwood cutt<strong>in</strong>g where it is not. To grow<br />

both pulpwood and hardwood saw logs, clean or th<strong>in</strong><br />

young stands to obta<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> desired proportions of fir<br />

and hardwoods. Then harvest <strong>the</strong> fir at about age 50<br />

and leave <strong>the</strong> hardwoods until <strong>the</strong>ymature (roughly<br />

age 100). Depend<strong>in</strong>g on how much <strong>the</strong> stand is<br />

opened, fir may produce a second crop of pulpwood<br />

while <strong>the</strong> hardwoods develop <strong>in</strong>to sawtimber. \\Then<br />

<strong>the</strong> hardwoods are mature, reproduce all species as<br />

described above and repeat <strong>the</strong> process. Because of<br />

balsam fir's shade tolerance, selection cutt<strong>in</strong>g is<br />

suitable where a high proportion of fir is desired.<br />

Convert<strong>in</strong>g balsam fir to o<strong>the</strong>r conifers should be<br />

considered where aspen and paper birch site <strong>in</strong>dexes<br />

are less than 60 and nor<strong>the</strong>rn hardwoods are not<br />

aggressive. <strong>Balsam</strong> fir sometimes grows on dry to<br />

dry-mesic sites, especially as an understory ofjack or<br />

red p<strong>in</strong>e. However, <strong>the</strong>se sites (usually sandy soils)<br />

are better suited <strong>for</strong> p<strong>in</strong>e, with red p<strong>in</strong>e outproduc<strong>in</strong>g<br />

jack p<strong>in</strong>e except on extremely dry sites. In most<br />

cases <strong>the</strong> manager should elim<strong>in</strong>ate fir when harvest<strong>in</strong>g<br />

p<strong>in</strong>e and convert jack p<strong>in</strong>e to red p<strong>in</strong>e.<br />

<strong>Balsam</strong> fir is a common associate ofeastern white<br />

p<strong>in</strong>e on mesic to wet-mesic sites. <strong>Fir</strong>-ei<strong>the</strong>r pure or<br />

mixed with eastern hemlock-often <strong>for</strong>ms an understory<br />

<strong>in</strong> mature white p<strong>in</strong>e stands. This understory<br />

may improve wildlife habitat or es<strong>the</strong>tics, but usually<br />

it should be removed so white p<strong>in</strong>e or ano<strong>the</strong>r<br />

preferred conifer can be established. White p<strong>in</strong>e can<br />

be reproduced naturally by shelterwood cutt<strong>in</strong>g or<br />

artificially by clearcutt<strong>in</strong>g and plant<strong>in</strong>g. Blister<br />

rust-resistant stock is now available <strong>for</strong> areas where<br />

white p<strong>in</strong>e blister rust is a major problem. To convert<br />

to ano<strong>the</strong>r conifer, red p<strong>in</strong>e should be planted on <strong>the</strong><br />

drier, less fertile sites and white spruce on <strong>the</strong><br />

moister, more fertile sites.<br />

White spruce is generally a m<strong>in</strong>or associate <strong>in</strong> balsam<br />

fir stands on mesicto wet-mesic sites. However,<br />

because of its higher value, longer life, and greater<br />

tolerance of budworm defoliation, white spruce is<br />

usually preferred over.balsam fir. Common. objectives<br />

are to <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>the</strong> stock<strong>in</strong>g ofwhite spruce and<br />

13

to manage <strong>for</strong> spruce sawtimber. If a mature fir<br />

stand has more than 500 well-distributed white<br />

spruce 3 feet or taller per acre, clearcut <strong>the</strong> stand to<br />

release <strong>the</strong>m but use care to m<strong>in</strong>imize logg<strong>in</strong>g damage<br />

(see p. 18). If white spruce advance growth is<br />

<strong>in</strong>adequate, ei<strong>the</strong>r use shelterwood cutt<strong>in</strong>g and scarification<br />

to obta<strong>in</strong> natural reproduction or clearcut<br />

<strong>the</strong> stand and plant white spruce.<br />

As <strong>the</strong> new stand develops, <strong>in</strong>termediate treatments<br />

will be needed to favor white spruce over balsam<br />

fir or o<strong>the</strong>r species. To produce a stand ofspruce<br />

sawtimber, release-by clean<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>for</strong> example-200<br />

to 300 white spruce crop trees per acre dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong><br />

sapl<strong>in</strong>g stage. Then, <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> pole stage th<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> surround<strong>in</strong>g<br />

trees one or more times to keep <strong>the</strong> spruce<br />

crop trees dom<strong>in</strong>ant. Because white spruce sawtimber<br />

requires a rotation of80 to 100 years, most or all<br />

of <strong>the</strong> shorter-lived fir and o<strong>the</strong>r species should be<br />

removed be<strong>for</strong>e <strong>the</strong> f<strong>in</strong>al harvest.<br />

As <strong>in</strong>dicated earlier, balsam fir often grows on<br />

wet-mesic to wet sites, especially <strong>in</strong> mixed swamp<br />

conifer stands that conta<strong>in</strong> nor<strong>the</strong>rn white-cedar<br />

and black spruce. Although <strong>the</strong> pulpwood produced<br />

by balsam fir sometimes makes <strong>the</strong>se stands more<br />

attractive economically, fir is not well adapted to<br />

wet sites (ma<strong>in</strong>ly organic soils). In addition, balsam<br />

fir usually is not as valuable <strong>for</strong> wildlife habitat<br />

(particularly deeryards) as nor<strong>the</strong>rn white-cedar.<br />

Un<strong>for</strong>tunately, balsam fir often dom<strong>in</strong>ates <strong>the</strong> advance<br />

growth <strong>in</strong> mixed swamp conifer stands, so it<br />

commonly succeeds nor<strong>the</strong>rn white-cedar and black<br />

spruce after harvest<strong>in</strong>g or o<strong>the</strong>r disturbance.<br />

In most cases <strong>the</strong> manager should m<strong>in</strong>imize <strong>the</strong><br />

balsam fir component on wet sites and favor associated<br />

swamp conifers. On harvest areas· broadcast<br />

burn<strong>in</strong>g of slash simultaneously elim<strong>in</strong>ates fir advance<br />

growth and improves seedbeds <strong>for</strong> associated<br />

conifers. Usually nor<strong>the</strong>rn white-cedar or tamarack<br />

should be reproduced on <strong>the</strong> more productive sites<br />

and black spruce on <strong>the</strong> less productive sites.<br />

Controll<strong>in</strong>g Damag<strong>in</strong>g Agents<br />

Spruce Budworm<br />

The spruce budworm is <strong>the</strong> most serious pest of<br />

balsam fir <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Lake <strong>States</strong>. Recurr<strong>in</strong>g outbreaks<br />

have caused much growth loss and mortality. In addition,.<br />

severe defoliation by <strong>the</strong> budwormoften leads<br />

to attack by o<strong>the</strong>r <strong>in</strong>sects and rot fungi. Thus, <strong>the</strong><br />

sprucebudworm. is <strong>the</strong>. most.damag<strong>in</strong>gagentofbalsam·<br />

fir <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Lake <strong>States</strong>.<br />

14<br />

High mortality of balsam fir from <strong>the</strong> spruce budworm<br />

is most likely <strong>in</strong> fir stands with <strong>the</strong><br />

characteristics:13<br />

1. high basal area or percentage of stand (50 percent<br />

or more) <strong>in</strong> balsam fir and/or white spruce;<br />

2. mature stands (50 or more years old), especially if<br />

extensive;<br />

3. open stands with tops of balsam fir and/or white<br />

spruce protrud<strong>in</strong>g above canopy;<br />

4. stands on poorly dra<strong>in</strong>ed soils that are extremely<br />

wet or dry; and<br />

5. stands downw<strong>in</strong>d of a budworm outbreak.<br />

Hazard-rat<strong>in</strong>g systems are available <strong>for</strong> assess<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>the</strong> vulnerability of balsam fir to budworm-caused<br />

mortality. These systems help <strong>the</strong> manager make<br />

ei<strong>the</strong>r short-term decisions dur<strong>in</strong>g a budworm outbreak<br />

to m<strong>in</strong>imize present losses or long-term decisions<br />

between outbreaks to reduce future losses.<br />

Short-term rat<strong>in</strong>g systems can help <strong>the</strong> manager decide<br />

which stands to harvest or spray dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> next<br />

few years. These systems require technical pr"cedures<br />

and so are used ma<strong>in</strong>ly by pest management<br />

specialists. For detailed <strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>mation on short-term<br />

rat<strong>in</strong>g systems, consult Agriculture <strong>Handbook</strong> 636<br />

(Witter and Lynch 1985).<br />

Long-term rat<strong>in</strong>g systems help <strong>the</strong> manager set<br />

priorities and schedules <strong>for</strong> harvest<strong>in</strong>g or o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

treatments to reduce <strong>the</strong> vulnerability of fir stands.<br />

These systems are based on stand vulnerability,<br />

which has been related to different stand characteristics<br />

<strong>in</strong> different geographic regions of <strong>the</strong> Lake<br />

<strong>States</strong>. Separate, region-specific systems must be<br />

used to reliably estimate <strong>the</strong> potential loss ofbalsam<br />

fir from a budworm outbreak. Long-term rat<strong>in</strong>g systems<br />

have been developed <strong>for</strong> M<strong>in</strong>nesota and Michigan's<br />

Upper Pen<strong>in</strong>sula but not <strong>for</strong> Wiscons<strong>in</strong>.<br />

Both <strong>the</strong> M<strong>in</strong>nesota and Michigan systems are<br />

easy to use because <strong>the</strong>y utilize readily available (or<br />

easily obta<strong>in</strong>able) stand data and simple computations.<br />

Rout<strong>in</strong>e compartment exam<strong>in</strong>ations or <strong>in</strong>ventories<br />

usually provide <strong>the</strong> necessary data. To use <strong>the</strong><br />

M<strong>in</strong>nesota system, <strong>for</strong> example, <strong>the</strong> manager only<br />

has to determ<strong>in</strong>e <strong>the</strong> preoutbreak basal area of balsam<br />

fir and <strong>the</strong> percent of stand basal area <strong>in</strong> nonhost<br />

species (those o<strong>the</strong>r than fir or spruce). Agriculture<br />

<strong>Handbook</strong> 636 (Witter and Lynch 1985) should<br />

be consulted <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> procedures and tables needed to<br />

use <strong>the</strong> M<strong>in</strong>nesota and Michigan systems. Un<strong>for</strong>tunately,<br />

<strong>the</strong>se systems are region-specific and thus<br />

probably are not applicable elsewhere; <strong>for</strong> example,<br />

13Adapted from Witter and Lynch (1985) .

labels are subject to change. There<strong>for</strong>e, consult a<br />

pest management specialist to f<strong>in</strong>d out <strong>the</strong> latest<br />

recommended treatment <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> situation. Insecticide<br />

spray<strong>in</strong>g should be done carefully, follow<strong>in</strong>g all<br />

pert<strong>in</strong>ent precautions and regulations (see Pesticide<br />

Precautionary Statement, p. 27).<br />

The future management of low-value fir stands<br />

abandoned dur<strong>in</strong>g a spruce budworm outbreak depends<br />

on such factors as species composition, soilsite<br />

conditions, and <strong>the</strong> owner's objective. Death of<br />

<strong>the</strong> overstory fir commonly releases fir advance<br />

growth, allow<strong>in</strong>g it to develop <strong>in</strong>to a new stand.<br />

Death of<strong>the</strong> fir may also offer a good opportunity to<br />

change to ano<strong>the</strong>r <strong>for</strong>est type as discussed under<br />

"Conversion and Alternat<strong>in</strong>g Crops" (p. 11) (fig. 5).<br />

Between outbreaks <strong>the</strong> manager should undertake<br />

long-term measures or strategies to reduce future<br />

budworm losses. Probably <strong>the</strong> best measure is<br />

to <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>the</strong> amount of nonhost species. Harvest<strong>in</strong>g<br />

often offers a good opportunity to change a predom<strong>in</strong>antly<br />

fir stand to a mixed stand or ano<strong>the</strong>r<br />

type (see p. 11). When economically feasible, <strong>in</strong>termediate<br />

treatments such as release or clean<strong>in</strong>g can<br />

be used to produce mixed stands offir and hardwoods<br />

or fir and o<strong>the</strong>r conifers (see p. 6). For maximum<br />

effectiveness <strong>in</strong> reduc<strong>in</strong>g future budworm losses,<br />

<strong>the</strong>se various operations should be spatially arranged<br />

so as to break up large areas dom<strong>in</strong>ated by<br />

fir.<br />

Although mixed stands may reduce future budworm<br />

losses, <strong>the</strong>y also reduce <strong>the</strong> yield ofbalsam<br />

fir-at least <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> short run. This is especially true<br />

where fir is overtopped by o<strong>the</strong>rspecies such as hardwoods.<br />

The manager should weigh <strong>the</strong> benefits of<br />

<strong>in</strong>creased fir growth after release, <strong>for</strong> example,<br />

aga<strong>in</strong>st <strong>the</strong> potential losses from a budworm outbreak.<br />

Ifharvest<strong>in</strong>g or <strong>in</strong>secticide spray<strong>in</strong>g can be<br />

prompt.after an outbreak.beg<strong>in</strong>s, release •. or .o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

<strong>in</strong>termediate treatments will <strong>in</strong>crease. fir .• yield..If<br />

prompt action is doubtful, it is safer to manage fir <strong>in</strong><br />

mixed stands.<br />

O<strong>the</strong>r long-term measureS that.should helpreduce<br />

future budworm losses are to diversify <strong>the</strong> age class<br />

distribution of balsam fir stands and to shorten <strong>the</strong><br />

rotation. Utilization that equals, or temporarily exceeds,<br />

annual growth will often be needed to elim<strong>in</strong>ate<br />

<strong>the</strong> buildup of mature and overmaturefirthat<br />

exists.<strong>in</strong> many•areas. Unless<strong>the</strong> objective is •••tdproduce<br />

small saw logs, harvest fir stands as soon as<br />

possible·•• where ..<strong>the</strong>y·...exceed .<strong>the</strong>"quality" ••.·rotations<br />

given onpage 6. When economically feasible, th<strong>in</strong><br />

dense young stands;. this not only shortens<strong>the</strong>irrotation(seep.<br />

8) but also keeps <strong>the</strong>m vigorous and<br />

probablyless ••vulnerable to budworm damage.<br />

Figure 5.-Typical stand of balsam fir killed by <strong>the</strong><br />

spruce budworm and now dom<strong>in</strong>ated by red raspberry.<br />

The lack ofreproduction offers a good opportunity<br />

to convert-by plant<strong>in</strong>g-to ano<strong>the</strong>r conifer.<br />

Rot and W<strong>in</strong>d<br />

Trunk rot and root (or butt) rot are <strong>the</strong> two major<br />

types of decay found <strong>in</strong> liv<strong>in</strong>g balsam fir trees. The<br />

pr<strong>in</strong>cipal trunk-rot fungus is red heart rot, which<br />

causes two or three times more cull than root-rot<br />

fungi .. The economically important root-rot fungi <strong>in</strong>clude<br />

four white (or yellow) str<strong>in</strong>gy rots and two<br />

brown cubical rots (see Appendix, p. 25, <strong>for</strong> scientific<br />

names). Shoestr<strong>in</strong>g root rot, a white str<strong>in</strong>gy rot, is<br />

probably <strong>the</strong> most prevalent species. Root rots damage<br />

fir ma<strong>in</strong>ly by mak<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> tree susceptible to<br />

w<strong>in</strong>dthrow or w<strong>in</strong>dbreakage; <strong>the</strong>y also kill <strong>the</strong> tree<br />

directly (especially shoestr<strong>in</strong>g root rot), cause cull by<br />

extend<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong> trunk, and reduce growth.<br />

Red heart rot enters balsam fir trees through fresh<br />

wounds such as broken tops or branches and trunk<br />

<strong>in</strong>juries. These wounds are commonly caused by harvest<strong>in</strong>g<br />

and snow or ice storms; black bears sometimes<br />

wound trunks by stripp<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> bark. Root (or<br />

butt) rots enter balsam fir through root or basal<br />

wounds caused by harvest<strong>in</strong>g and various natural<br />

phenomena. Shoestr<strong>in</strong>g root rot <strong>in</strong>vades fir especially<br />

dur<strong>in</strong>g droughts and follow<strong>in</strong>g severe defoliation<br />

by <strong>the</strong> spruce budworm.<br />

Except <strong>for</strong> woodpecker holes, few reliable external<br />

<strong>in</strong>dicators of trunk and root rot exist <strong>for</strong> balsam fir.<br />

Old wounds probably <strong>in</strong>dicate <strong>the</strong> presence of rot,<br />

but <strong>the</strong> causal fungi rarely produce fruit<strong>in</strong>g bodies

on <strong>the</strong> important shoestr<strong>in</strong>g<br />

root rot below ground. However, as<br />

discussed under "Rotation" 5), stand age and site<br />

conditions <strong>in</strong>fluence <strong>the</strong> presence of rot.<br />

There<strong>for</strong>e, <strong>in</strong> most cases, <strong>the</strong> "quality" rotations<br />

given <strong>the</strong>re will m<strong>in</strong>imize losses from rot; <strong>the</strong>y may<br />

also reduce future budworm losses. Even<br />

shorter rotations should be considered <strong>for</strong> stands<br />

vulnerable to rot because ofsevere budworm defoliation<br />

or o<strong>the</strong>r significant damage.<br />

O<strong>the</strong>r ways to control losses from rot <strong>in</strong>clude grow<strong>in</strong>g<br />

balsam fir on suitable sites, releas<strong>in</strong>g fir advance<br />

growth, m<strong>in</strong>imiz<strong>in</strong>g damage from mechanized operations,<br />

and monitor<strong>in</strong>g budworm or o<strong>the</strong>r damage.<br />

In general, manage fir on wet-mesic sites where it<br />

grows well and has rot than on dry sandy sites<br />

or on highly (mesic) hardwood sites. Release<br />

not only <strong>in</strong>creases <strong>the</strong> growth rate but also<br />

apparently can reduce <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>cidence ofrot. However,<br />

if fir advance growth is severely suppressed (especially<br />

by nor<strong>the</strong>rn hardwoods), do not release or<br />

o<strong>the</strong>rwise manage it <strong>for</strong> timber. Mechanized equipment<br />

must be used carefully to m<strong>in</strong>imize wound<strong>in</strong>g<br />

ofresidual firs (see next section). This is particularly<br />

important if <strong>the</strong> rotation is leng<strong>the</strong>ned <strong>in</strong> order to<br />

produce saw logs. <strong>Fir</strong> stands that have suffered from<br />

budworm defoliation, drought, or storm damage<br />

should be checked periodically. If losses from rot<br />

beg<strong>in</strong> or appear imm<strong>in</strong>ent, reproduce <strong>the</strong> stand by<br />

us<strong>in</strong>g an appropriate silvicultural system (see p. 9).<br />

As already <strong>in</strong>dicated, w<strong>in</strong>d commonly uproots or<br />

breaks offbalsam fir trees weakened by root (or butt)<br />

rot. W<strong>in</strong>d also uproots balsam fir because of its shallow<br />

root system. This often occurs where <strong>the</strong> root<strong>in</strong>g<br />

zone is shallow, such as on sites with a high water<br />

table or a fragipan. Moderate w<strong>in</strong>dstorms blow down<br />

some trees-such as those weakened by rot-and<br />

leave <strong>the</strong>m ly<strong>in</strong>g crisscrossed, whereas severe w<strong>in</strong>dstorms<br />

generally blow down all trees <strong>in</strong> an area and<br />

leave <strong>the</strong>m ly<strong>in</strong>g parallel to each o<strong>the</strong>r. W<strong>in</strong>d damage<br />

is usually <strong>in</strong>creased by partial cutt<strong>in</strong>g-especially<br />

<strong>in</strong> stands not previously managed, <strong>in</strong> stands<br />

with considerable root (or butt) rot, and on sites with<br />

a shallow root<strong>in</strong>g zone.<br />

W<strong>in</strong>d damage to balsam fir can be controlled by<br />

good management. To m<strong>in</strong>imize losses from w<strong>in</strong>d<br />

and rot comb<strong>in</strong>ed, use <strong>the</strong> "quality" rotations given<br />

on page 6. Do partial cutt<strong>in</strong>g such as th<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g and<br />

shelterwood cutt<strong>in</strong>g only on areas or sites where fir<br />

is known to be w<strong>in</strong>dfirm. Ifw<strong>in</strong>d is a major problem,<br />

manage fir extensively-<strong>for</strong> example, do noth<strong>in</strong>g except<br />

clearcut when mature-or do not manage <strong>for</strong> fir<br />

at all.<br />

When sett<strong>in</strong>g up a fir stand <strong>for</strong> partial cutt<strong>in</strong>g,<br />

make sure <strong>the</strong> w<strong>in</strong>dward side is protected by a zone<br />

ofuncut timber at least 1 cha<strong>in</strong> wide. Also, make <strong>the</strong><br />

cutt<strong>in</strong>g boundary smooth and reasonably straight to<br />

avoid w<strong>in</strong>d damage result<strong>in</strong>gfrom sharp angles such<br />

as corners. In mixed stands of fir and hardwoods,<br />

leave a well-distributed hardwood component. For<br />

o<strong>the</strong>r ways to control w<strong>in</strong>d damage when do<strong>in</strong>g partial<br />

cutt<strong>in</strong>g, see "Intermediate Treatments" (p. 6)<br />

and "Silvicultural Systems" (p. 9). If damagewhich<br />

occurs especially dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> first 3 to 5 years<br />

after cutt<strong>in</strong>g-becomes severe, consider a salvage<br />

operation to m<strong>in</strong>imize <strong>the</strong> timber loss.<br />

O<strong>the</strong>r Agents<br />

Although <strong>the</strong> spruce budworm is <strong>the</strong> predom<strong>in</strong>ant<br />

<strong>in</strong>sect damag<strong>in</strong>g balsam fir (<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g cone crops) <strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> Lake <strong>States</strong>, a few o<strong>the</strong>r <strong>in</strong>sects can become important<br />

pests. Outbreaks oftwo defoliators, <strong>the</strong> hemlock<br />

looper and <strong>the</strong> eastern blackheaded budworm,<br />

have seriously damaged mature and overmature<br />

stands dom<strong>in</strong>ated by fir. Two secondary <strong>in</strong>sects, <strong>the</strong><br />

balsam fir bark beetle and <strong>the</strong> balsam fir sawyer,<br />

often attack fir weakened by <strong>the</strong> spruce budworm or<br />

drought. The fir coneworm commonly attacks fir<br />

cones and may cause significant seed loss. Diversify<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>the</strong> age class distribution of balsam fir stands<br />

and shorten<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> rotation-as discussed under<br />

"Spruce Budworm" (p. 14)-should reduce damage<br />

by <strong>the</strong> defoliators; control of <strong>the</strong> spruce budworm<br />

should reduce damage by <strong>the</strong> secondary <strong>in</strong>sects. No<br />

silvicultural measures are known <strong>for</strong> controll<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong><br />

coneworm.<br />

<strong>Balsam</strong> fir is host to many rusts, cankers, and<br />

o<strong>the</strong>r diseases, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g a conspicuous yellow<br />

witches' broom. But none except rots (see p. 16) is<br />

economically important, so control measures are not<br />

needed.<br />

Wildlife sometimes damages balsam fir by feed<strong>in</strong>g<br />

or o<strong>the</strong>r activities. For example, moose, white-tailed<br />

deer, and snowshoe hares browse reproduction; mice<br />

and voles feed on bark of reproduction; black bears<br />

strip bark of mature trees; birds (such as spruce<br />

grouse) and red squirrels nip buds; and mice, voles,<br />

and birds consume seed. It is <strong>for</strong>tunate <strong>the</strong>se activities<br />

usually do not severely damage fir because no<br />

practical control measures are known. Actually, as<br />

long as balsam fir stands can be established or ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong>ed,<br />

<strong>the</strong>se activities should be considered beneficial<br />

to wildlife ra<strong>the</strong>r than damag<strong>in</strong>g to fir.<br />

Because of its th<strong>in</strong> bark and·shallow root.system,<br />

balsam fir is susceptible to damage from harvest<strong>in</strong>g<br />

and o<strong>the</strong>r mechanized operations. Residual trees<br />

often develop rotfrom wounds to <strong>the</strong>ir base or roots<br />

17

(see p. 16), and advance growth commonly is crushed<br />

by equipment or buried by slash. Hence treatments<br />

that <strong>in</strong>volve keep<strong>in</strong>g residual trees or advance<br />

growth-<strong>for</strong> example, th<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g or shelterwood cutt<strong>in</strong>g-should<br />

be done carefully by skilled operators<br />

us<strong>in</strong>g small, maneuverable equipment. Ideally, such<br />

treatments should be done <strong>in</strong> w<strong>in</strong>ter when <strong>the</strong> base<br />

and roots of trees, and <strong>the</strong> stems of small advance<br />

growth, are protected by a snow pack. Full-tree skidd<strong>in</strong>g<br />

is recommended ifa heavy slash cover is likely;<br />

however, skidd<strong>in</strong>g damage needs to be controlled by<br />

follow<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> above precautions.<br />

To release balsam fir from large cull hardwoods,<br />

use herbicide <strong>in</strong>jection ra<strong>the</strong>r than fell<strong>in</strong>g to kill <strong>the</strong><br />

hardwoods (see p. 7). This not only m<strong>in</strong>imizes damage<br />

to <strong>the</strong> fir but also provides stand<strong>in</strong>g dead trees<br />

<strong>for</strong> cavity-nest<strong>in</strong>g wildlife.<br />

<strong>Balsam</strong> fir trees ofall sizes are easily killed by fire<br />

because of<strong>the</strong>ir th<strong>in</strong> res<strong>in</strong>ous bark, shallow root system,<br />

and flammable needles, which often are close to<br />

<strong>the</strong> ground. However, good fire protection now resuIts<br />

<strong>in</strong> little loss, and much of<strong>the</strong> fir type grows on<br />

wet-mesic to wet sites where wildfire risk is normally<br />

low. Heavy cutt<strong>in</strong>g, of course, produces large<br />

amounts of balsam fir slash, which can be a fire<br />

hazard <strong>for</strong> several years. There<strong>for</strong>e, use full-tree<br />

skidd<strong>in</strong>g ifa heavy slash cover is likely, such as after<br />

shelterwood cutt<strong>in</strong>g or clearcutt<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

OTHER RESOURCE<br />

CONSIDERATIONS<br />

Boughs and Christmas Trees<br />

Compared to timber production, balsam fir boughs<br />

and Christmas trees are m<strong>in</strong>or products of natural<br />

stands. However, large quantities of boughs (<strong>for</strong><br />

mak<strong>in</strong>g wreaths) and many Christmas trees are harvested<br />

<strong>in</strong> certa<strong>in</strong> areas of <strong>the</strong> nor<strong>the</strong>rn Lake <strong>States</strong>.<br />

Prolonged needle retention, color, and pleasant fragrance<br />

are characteristics that make balsam fir attractive<br />

<strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong>se uses.<br />

Boughs are cut from <strong>the</strong> lower branches of opengrown<br />

trees or from trees felled <strong>for</strong> pulpwood. Christmas<br />

trees <strong>in</strong>clude large ones (20 to 60 feet tall) <strong>for</strong><br />

community use as well as small ones <strong>for</strong> home use.<br />

The large trees must be open-grown, as occurs when<br />

sparse fir reproduction develops after heavy cutt<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

Some small firs are harvested from natural reproduction,<br />

but shear<strong>in</strong>g is needed to make <strong>the</strong>m competitive<br />

with sheared, plantation-grown trees.<br />

18<br />

The potential <strong>for</strong> produc<strong>in</strong>g more balsam fir<br />

Christmas trees by shear<strong>in</strong>g natural reproduction<br />

appears good on small, privately owned areas and on<br />

power l<strong>in</strong>e rights-of-way. However, little is known<br />

about <strong>the</strong> spac<strong>in</strong>g and o<strong>the</strong>r cultural requirements<br />

to grow marketable trees. Forest managers probably<br />

can obta<strong>in</strong> some advice from Christmas tree growers<br />

experienced with balsam fir. A potentially serious<br />

pest is <strong>the</strong> balsam gall midge, which <strong>for</strong>ms galls on<br />

<strong>the</strong> needles of young, open-grown firs. The <strong>in</strong>fested<br />

needles drop prematurely and nlake <strong>the</strong> trees unmarketable.<br />

If this <strong>in</strong>sect becomes a consult<br />

a pest management <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> most appropriate<br />

treatment.<br />

Wildlife Habitat<br />

The balsam fir type is important to many wildlife<br />

species <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> nor<strong>the</strong>rn Lake <strong>States</strong>. The timber<br />

wolf, an endangered species (threatened <strong>in</strong> M<strong>in</strong>nesota),<br />

and four species with sensitive habitat<br />

needs-p<strong>in</strong>e marten, fisher, Canada lynx, and bobcat-are<br />

all associated with this type. O<strong>the</strong>r species<br />

that use <strong>the</strong> balsam fir type <strong>for</strong> part or all of <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

habitat needs <strong>in</strong>clude: common mammals such as<br />

white-tailed deer, moose, black bear, snowshoe hare,<br />

and small rodents (<strong>for</strong> example, red-backed vole,<br />

deer mouse, and red squirrel); various birds, especially<br />

spruce grouse, warblers, and three-toed woodpeckers;<br />

and a few reptiles and amphibians, particularly<br />

salamanders and frogs.<br />

<strong>Balsam</strong> fir stands are beneficial <strong>for</strong> both "edge"<br />

and "<strong>in</strong>terior" wildlife species. Although edge species<br />

(such as deer and hare) are associated ma<strong>in</strong>ly<br />

with <strong>for</strong>est open<strong>in</strong>gs and young stands, <strong>the</strong>y often<br />

use middle-aged or mature fir stands <strong>for</strong> protection<br />

from wea<strong>the</strong>r or predators (fig. 6). Interior species<br />

(such as marten and warblers) use mature fir stands<br />

<strong>for</strong> most or all of<strong>the</strong>ir habitat needs. The best way to<br />

manage balsam fir stands <strong>for</strong> wildlife depends on <strong>the</strong><br />

species <strong>the</strong> <strong>for</strong>est owner wants to favor. Ifa diversity<br />

of species is desired, various stand conditions must<br />

be ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong>ed. This is most feasible on large (especially<br />

public) <strong>for</strong>ests.<br />

The balsam fir type protects several wildlife<br />

species from w<strong>in</strong>ter temperatures and snow. Although<br />

not as beneficial as nor<strong>the</strong>rn white-cedar or<br />

eastern hemlock <strong>for</strong> deeryards, balsam fir is important<br />

because it is more widespread and easier to<br />

establish than white-cedar or hemlock. Compared to<br />

white spruce, balsam fir generally has few branches<br />

near <strong>the</strong> ground; thus, deer can bed down closer to a<br />

fir tree and be less exposed to heat loss. <strong>Fir</strong> stands

Figure 6.-This closed stand ofpole-sized balsam fir<br />

provides important habitat <strong>for</strong> several wildlife species.<br />

Such stands often are used <strong>for</strong> protection from<br />

wea<strong>the</strong>r, both <strong>in</strong> w<strong>in</strong>ter and summer.<br />

more than 20 years old with a basal area of at least<br />

70 square feet per acre moderate temperatures. Also,<br />

snow is not as deep <strong>in</strong> balsam fir stands as it is <strong>in</strong><br />

aspen and paper birch stands. Consequently, fir<br />

stands often are heavily used by deer and by moose<br />

with calves dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> severe w<strong>in</strong>ter months. For<br />

similar reasons, deer and furbearers (such as fisher,<br />

lynx, and marten) use fir stands <strong>for</strong> travel lanes.<br />

Edge wildlife species benefit most from balsam fir<br />

when stands suitable <strong>for</strong> w<strong>in</strong>ter cover occur adjacent<br />

to young (especially hardwood) stands, which produce<br />

browse or o<strong>the</strong>r food. For good deer and moose<br />

cover, manage fir <strong>in</strong> even-aged stands and ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong><br />

a closed canopy. Ifcover is critical, avoid heavy partial<br />

cutt<strong>in</strong>g and try to prevent severe budworm defoliation.<br />

A well-developed fir understory beneath mature<br />

aspen or paper birch also provides w<strong>in</strong>ter cover,<br />

especially <strong>in</strong> areas without adequate white-cedar or<br />

hemlock stands.<br />

O<strong>the</strong>r habitat important to deer and moose-and<br />

also used by hare-is poorly to moderately stocked<br />

or patchy pole- and sawtimber-sized fir stands.<br />

These lower density stands (with a basal area ofless<br />

than 70 square feet per acre) support a welldeveloped<br />

shrub layer that provides food <strong>in</strong> close<br />

proximity to conifer cover. Convert<strong>in</strong>g such stands to<br />

spruce or p<strong>in</strong>e plantations-especially us<strong>in</strong>g herbicides<br />

to control shrubs and hardwoods-greatly reduces<br />

<strong>the</strong> use of<strong>the</strong>se areas not only by deer, moose,<br />

and hare but also by <strong>the</strong>ir predators such as <strong>the</strong> wolf,<br />

lynx, and fisher. Extensive areas of fir mixed with<br />

hardwoods are utilized especially by <strong>the</strong> bobcat and<br />

fisher.<br />

Dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> warm summer months balsam fir<br />

stands provide shade that helps cool deer,moose,<br />

and bear after feed<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> open areas. Moose commonly<br />

rest <strong>in</strong> fir stands near wetlands where <strong>the</strong>y<br />

feed. To provide cool<strong>in</strong>g sites <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong>se and o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

wildlife species, leave from 2- to 5-acre patches of<br />

well-stocked balsam fir distributed throughout large<br />

harvest areas. Un<strong>for</strong>tunately, <strong>the</strong>se patches can susta<strong>in</strong><br />

spruce budworm <strong>in</strong>festations and should not be<br />

left where budworm control is a more important consideration.<br />

Also dur<strong>in</strong>g summer various birds use fir<br />

stands <strong>for</strong> nest<strong>in</strong>g; warblers such as <strong>the</strong> Cape May,<br />

blackpoll, and blackburnian especially prefer this<br />

habitat.<br />

Ano<strong>the</strong>r value of balsam fir <strong>for</strong> several wildlife<br />

species is protection from predators. Species such as<br />

marten, hare, songbirds, and even deer will use wellstocked<br />

fir stands <strong>for</strong> protection. <strong>Balsam</strong> fir also benefits<br />

certa<strong>in</strong> predators; <strong>for</strong> example, s<strong>in</strong>gle fir trees<br />

left on harvest areas provide perches <strong>for</strong> hunt<strong>in</strong>g and<br />

roost<strong>in</strong>g hawks and owls. However, residual firs (or<br />

spruces) should not be left because <strong>the</strong>y are too vulnerable<br />

to w<strong>in</strong>d damage and can serve as <strong>in</strong>festation<br />

centers <strong>for</strong> budworm outbreaks (see p.15).<br />

Many wildlife species feed on balsam fir (see p. 17),<br />

but only a few use it to much extent. <strong>Fir</strong> needles and<br />

buds make up a major portion of<strong>the</strong> spruce grouse's<br />

diet. <strong>Fir</strong> browse may <strong>for</strong>m up to 30 percent of <strong>the</strong><br />

moose's fall and w<strong>in</strong>ter diet; however, <strong>the</strong> average is<br />

much lower. In addition, fir stands attacked by <strong>the</strong><br />

spruce budworm attract many <strong>in</strong>sect-eat<strong>in</strong>g birds,<br />

especially Cape May, black-throated green, and<br />

blackburnian warblers, and woodpeckers such as <strong>the</strong><br />

rare black-backed three-toed and nor<strong>the</strong>rn threetoed.<br />

Woodpeckers, <strong>in</strong> turn, produce tree cavities<br />

that are used by various wildlife species, thus enhanc<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>the</strong> value of<strong>the</strong> balsam fir type. On harvest<br />

areas slash supports <strong>in</strong>sects eaten by birds such as<br />

<strong>the</strong> dark-eyed junco and w<strong>in</strong>ter wren. However,<br />

some slash should be removed <strong>in</strong> heavily cut stands<br />

to favor fir reproduction and reduce <strong>the</strong> fire hazard<br />

(see p. 9).<br />

To benefit a diversity of wildlife species <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

nor<strong>the</strong>rn Lake <strong>States</strong>, ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong> from 10 to 20 per-<br />

19

cent of each management area (such as a compartment)<br />

<strong>in</strong> balsam fir stands. If conifer cover is lack<strong>in</strong>g,<br />

promote succession to fir on enough of <strong>the</strong> area<br />

to achieve <strong>the</strong> recommended range. If fir stands occupy<br />

much more than 20 percent ofan area, convert<br />

some of<strong>the</strong> area to o<strong>the</strong>r types, especially hardwoods<br />

(see p. 11). Convert<strong>in</strong>g excessive fir acreage to aspen<br />

would most benefit edge species, which <strong>in</strong>clude<br />

major game species such as white-tailed deer and<br />

ruffed grouse. Ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g a moderate-ra<strong>the</strong>r<br />

than large-proportion of fir should not only enhance<br />

wildlife habitat (and es<strong>the</strong>tics) but also reduce<br />

vulnerability to budworm damage.<br />

To manage balsam fir stands <strong>for</strong> a diversity of<br />

wildlife species, ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong> a range of age (or size)<br />

classes from young seedl<strong>in</strong>gs to mature trees. Although<br />

this range can be obta<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> uneven-aged<br />

stands, even-aged stands are preferred <strong>for</strong> wildlife<br />

(as well as timber) management <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Lake <strong>States</strong>.<br />

Depend<strong>in</strong>g on <strong>the</strong> food and cover needs <strong>in</strong> an area, fir<br />