Download a PDF version of this article here - Flames of War

Download a PDF version of this article here - Flames of War

Download a PDF version of this article here - Flames of War

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

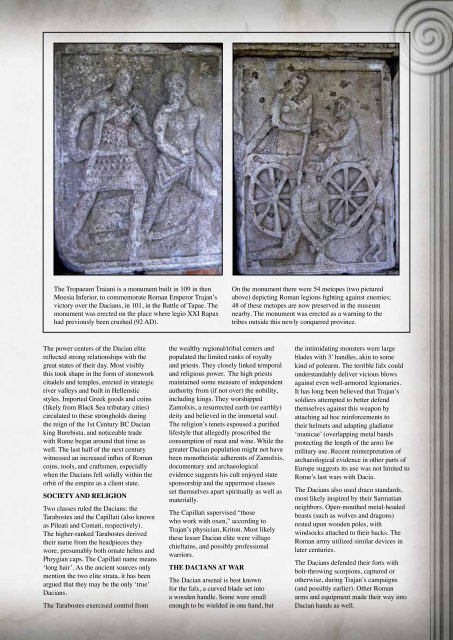

The Tropaeum Traiani is a monument built in 109 in then<br />

Moesia Inferior, to commemorate Roman Emperor Trajan’s<br />

victory over the Dacians, in 101, in the Battle <strong>of</strong> Tapae. The<br />

monument was erected on the place w<strong>here</strong> legio XXI Rapax<br />

had previously been crushed (92 AD).<br />

The power centers <strong>of</strong> the Dacian elite<br />

reflected strong relationships with the<br />

great states <strong>of</strong> their day. Most visibly<br />

<strong>this</strong> took shape in the form <strong>of</strong> stonework<br />

citadels and temples, erected in strategic<br />

river valleys and built in Hellenstic<br />

styles. Imported Greek goods and coins<br />

(likely from Black Sea tributary cities)<br />

circulated to these strongholds during<br />

the reign <strong>of</strong> the 1st Century BC Dacian<br />

king Burebista, and noticeable trade<br />

with Rome began around that time as<br />

well. The last half <strong>of</strong> the next century<br />

witnessed an increased influx <strong>of</strong> Roman<br />

coins, tools, and craftsmen, especially<br />

when the Dacians fell solidly within the<br />

orbit <strong>of</strong> the empire as a client state.<br />

SOCIETy AND RELIGION<br />

Two classes ruled the Dacians: the<br />

Tarabostes and the Capillati (also known<br />

as Pileati and Comati, respectively).<br />

The higher-ranked Tarabostes derived<br />

their name from the headpieces they<br />

wore, presumably both ornate helms and<br />

Phrygian caps. The Capillati name means<br />

‘long hair’. As the ancient sources only<br />

mention the two elite strata, it has been<br />

argued that they may be the only ‘true’<br />

Dacians.<br />

The Tarabostes exercised control from<br />

the wealthy regional/tribal centers and<br />

populated the limited ranks <strong>of</strong> royalty<br />

and priests. They closely linked temporal<br />

and religious power. The high priests<br />

maintained some measure <strong>of</strong> independent<br />

authority from (if not over) the nobility,<br />

including kings. They worshipped<br />

Zamolxis, a resurrected earth (or earthly)<br />

deity and believed in the immortal soul.<br />

The religion’s tenets espoused a purified<br />

lifestyle that allegedly proscribed the<br />

consumption <strong>of</strong> meat and wine. While the<br />

greater Dacian population might not have<br />

been monotheistic ad<strong>here</strong>nts <strong>of</strong> Zamolxis,<br />

documentary and archaeological<br />

evidence suggests his cult enjoyed state<br />

sponsorship and the uppermost classes<br />

set themselves apart spiritually as well as<br />

materially.<br />

The Capillati supervised “those<br />

who work with oxen,” according to<br />

Trajan’s physician, Kriton. Most likely<br />

these lesser Dacian elite were village<br />

chieftains, and possibly pr<strong>of</strong>essional<br />

warriors.<br />

ThE DACIANS AT WAR<br />

The Dacian arsenal is best known<br />

for the falx, a curved blade set into<br />

a wooden handle. Some were small<br />

enough to be wielded in one hand, but<br />

On the monument t<strong>here</strong> were 54 metopes (two pictured<br />

above) depicting Roman legions fighting against enemies;<br />

48 <strong>of</strong> these metopes are now preserved in the museum<br />

nearby. The monument was erected as a warning to the<br />

tribes outside <strong>this</strong> newly conquered province.<br />

the intimidating monsters were large<br />

blades with 3’ handles, akin to some<br />

kind <strong>of</strong> polearm. The terrible falx could<br />

understandably deliver vicious blows<br />

against even well-armored legionaries.<br />

It has long been believed that Trajan’s<br />

soldiers attempted to better defend<br />

themselves against <strong>this</strong> weapon by<br />

attaching ad hoc reinforcements to<br />

their helmets and adapting gladiator<br />

‘manicae’ (overlapping metal bands<br />

protecting the length <strong>of</strong> the arm) for<br />

military use. Recent reinterpretation <strong>of</strong><br />

archaeological evidence in other parts <strong>of</strong><br />

Europe suggests its use was not limited to<br />

Rome’s last wars with Dacia.<br />

The Dacians also used draco standards,<br />

most likely inspired by their Sarmatian<br />

neighbors. Open-mouthed metal-headed<br />

beasts (such as wolves and dragons)<br />

rested upon wooden poles, with<br />

windsocks attached to their backs. The<br />

Roman army utilized similar devices in<br />

later centuries.<br />

The Dacians defended their forts with<br />

bolt-throwing scorpions, captured or<br />

otherwise, during Trajan’s campaigns<br />

(and possibly earlier). Other Roman<br />

arms and equipment made their way into<br />

Dacian hands as well.