Download a PDF version of this article here - Flames of War

Download a PDF version of this article here - Flames of War

Download a PDF version of this article here - Flames of War

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

The Dacians<br />

A LOOk AT ThE LAST GREAT CONqUEST Of ROME By Paul Leach<br />

The Dacians have the dubious honor <strong>of</strong> serving as one<br />

<strong>of</strong> the last great conquests <strong>of</strong> Rome by none other<br />

than Emperor Trajan.<br />

His campaign memoirs are lost to us, but<br />

his famous column gives us a glimpse<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Dacians as they struggled against<br />

the might <strong>of</strong> the empire: siege weapons<br />

defend their forts, some warriors use<br />

scythe-bladed weapons, and their capped<br />

leaders would not look out <strong>of</strong> place in<br />

Persian steles. Greco-Roman writers shed<br />

limited light on <strong>this</strong> barbarian people<br />

who don’t quite fit the classical barbarian<br />

mold. Who were these Balkan tribes that<br />

doggedly fought against the Romans at<br />

the turn <strong>of</strong> the 2nd Century?<br />

ORIGINS<br />

The Dacians were an ancient people <strong>of</strong><br />

the Balkans region, concentrated in the<br />

northern and western areas <strong>of</strong> modern<br />

Romania. They, along with their Getae<br />

cousins, descended from the Gáva-<br />

Holihrad culture that emerged around the<br />

Carpathians after 1,000 BC. Celtic tribes<br />

proved a dominant influence upon the<br />

Dacians, especially during their zenith <strong>of</strong><br />

the 4th through 2nd Centuries BC, and so<br />

did the Sarmatians that migrated to the<br />

European limits <strong>of</strong> the eastern Greco-<br />

Roman world. Of course, other ethnic<br />

groups left their marks, including Greek<br />

and Thracian merchants and adventurers.<br />

The Hellenistic kingdom <strong>of</strong> Pontus,<br />

followed by the Roman Empire, brought<br />

about significant alterations to Dacian<br />

society, at least in regards to how the elite<br />

lived and governed in the two centuries<br />

before the complete demise <strong>of</strong> the Dacian<br />

kingdom in 106 AD.<br />

The Dacians were long believed to share<br />

deep roots with the Thracians, according<br />

to the earliest classical sources. Some<br />

modern studies wholeheartedly disagree<br />

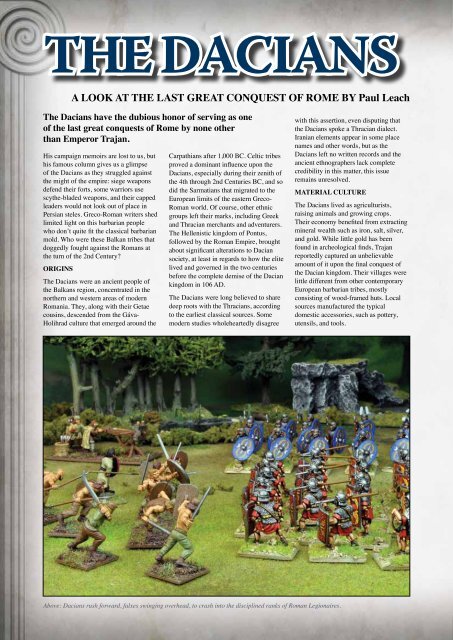

Above: Dacians rush forward, falxes swinging overhead, to crash into the disciplined ranks <strong>of</strong> Roman Legionaires.<br />

with <strong>this</strong> assertion, even disputing that<br />

the Dacians spoke a Thracian dialect.<br />

Iranian elements appear in some place<br />

names and other words, but as the<br />

Dacians left no written records and the<br />

ancient ethnographers lack complete<br />

credibility in <strong>this</strong> matter, <strong>this</strong> issue<br />

remains unresolved.<br />

MATERIAL CULTURE<br />

The Dacians lived as agriculturists,<br />

raising animals and growing crops.<br />

Their economy benefited from extracting<br />

mineral wealth such as iron, salt, silver,<br />

and gold. While little gold has been<br />

found in archeological finds, Trajan<br />

reportedly captured an unbelievable<br />

amount <strong>of</strong> it upon the final conquest <strong>of</strong><br />

the Dacian kingdom. Their villages were<br />

little different from other contemporary<br />

European barbarian tribes, mostly<br />

consisting <strong>of</strong> wood-framed huts. Local<br />

sources manufactured the typical<br />

domestic accessories, such as pottery,<br />

utensils, and tools.

The Tropaeum Traiani is a monument built in 109 in then<br />

Moesia Inferior, to commemorate Roman Emperor Trajan’s<br />

victory over the Dacians, in 101, in the Battle <strong>of</strong> Tapae. The<br />

monument was erected on the place w<strong>here</strong> legio XXI Rapax<br />

had previously been crushed (92 AD).<br />

The power centers <strong>of</strong> the Dacian elite<br />

reflected strong relationships with the<br />

great states <strong>of</strong> their day. Most visibly<br />

<strong>this</strong> took shape in the form <strong>of</strong> stonework<br />

citadels and temples, erected in strategic<br />

river valleys and built in Hellenstic<br />

styles. Imported Greek goods and coins<br />

(likely from Black Sea tributary cities)<br />

circulated to these strongholds during<br />

the reign <strong>of</strong> the 1st Century BC Dacian<br />

king Burebista, and noticeable trade<br />

with Rome began around that time as<br />

well. The last half <strong>of</strong> the next century<br />

witnessed an increased influx <strong>of</strong> Roman<br />

coins, tools, and craftsmen, especially<br />

when the Dacians fell solidly within the<br />

orbit <strong>of</strong> the empire as a client state.<br />

SOCIETy AND RELIGION<br />

Two classes ruled the Dacians: the<br />

Tarabostes and the Capillati (also known<br />

as Pileati and Comati, respectively).<br />

The higher-ranked Tarabostes derived<br />

their name from the headpieces they<br />

wore, presumably both ornate helms and<br />

Phrygian caps. The Capillati name means<br />

‘long hair’. As the ancient sources only<br />

mention the two elite strata, it has been<br />

argued that they may be the only ‘true’<br />

Dacians.<br />

The Tarabostes exercised control from<br />

the wealthy regional/tribal centers and<br />

populated the limited ranks <strong>of</strong> royalty<br />

and priests. They closely linked temporal<br />

and religious power. The high priests<br />

maintained some measure <strong>of</strong> independent<br />

authority from (if not over) the nobility,<br />

including kings. They worshipped<br />

Zamolxis, a resurrected earth (or earthly)<br />

deity and believed in the immortal soul.<br />

The religion’s tenets espoused a purified<br />

lifestyle that allegedly proscribed the<br />

consumption <strong>of</strong> meat and wine. While the<br />

greater Dacian population might not have<br />

been monotheistic ad<strong>here</strong>nts <strong>of</strong> Zamolxis,<br />

documentary and archaeological<br />

evidence suggests his cult enjoyed state<br />

sponsorship and the uppermost classes<br />

set themselves apart spiritually as well as<br />

materially.<br />

The Capillati supervised “those<br />

who work with oxen,” according to<br />

Trajan’s physician, Kriton. Most likely<br />

these lesser Dacian elite were village<br />

chieftains, and possibly pr<strong>of</strong>essional<br />

warriors.<br />

ThE DACIANS AT WAR<br />

The Dacian arsenal is best known<br />

for the falx, a curved blade set into<br />

a wooden handle. Some were small<br />

enough to be wielded in one hand, but<br />

On the monument t<strong>here</strong> were 54 metopes (two pictured<br />

above) depicting Roman legions fighting against enemies;<br />

48 <strong>of</strong> these metopes are now preserved in the museum<br />

nearby. The monument was erected as a warning to the<br />

tribes outside <strong>this</strong> newly conquered province.<br />

the intimidating monsters were large<br />

blades with 3’ handles, akin to some<br />

kind <strong>of</strong> polearm. The terrible falx could<br />

understandably deliver vicious blows<br />

against even well-armored legionaries.<br />

It has long been believed that Trajan’s<br />

soldiers attempted to better defend<br />

themselves against <strong>this</strong> weapon by<br />

attaching ad hoc reinforcements to<br />

their helmets and adapting gladiator<br />

‘manicae’ (overlapping metal bands<br />

protecting the length <strong>of</strong> the arm) for<br />

military use. Recent reinterpretation <strong>of</strong><br />

archaeological evidence in other parts <strong>of</strong><br />

Europe suggests its use was not limited to<br />

Rome’s last wars with Dacia.<br />

The Dacians also used draco standards,<br />

most likely inspired by their Sarmatian<br />

neighbors. Open-mouthed metal-headed<br />

beasts (such as wolves and dragons)<br />

rested upon wooden poles, with<br />

windsocks attached to their backs. The<br />

Roman army utilized similar devices in<br />

later centuries.<br />

The Dacians defended their forts with<br />

bolt-throwing scorpions, captured or<br />

otherwise, during Trajan’s campaigns<br />

(and possibly earlier). Other Roman<br />

arms and equipment made their way into<br />

Dacian hands as well.

Above: Dacia and some <strong>of</strong> the surrounding Roman provinces, circa 100 AD.<br />

ThE AGE Of BUREBISTA<br />

The Dacian kingdom reached its height<br />

just prior to the middle <strong>of</strong> the 1st<br />

Century BC, coinciding with collapse<br />

<strong>of</strong> Mithradates Eupator’s Pontic realm<br />

and the ascension <strong>of</strong> its greatest ruler,<br />

Burebista. Positioned at the edge <strong>of</strong><br />

Greco-Roman world, the Dacian king<br />

took advantage <strong>of</strong> the power vacuum<br />

left by the Pontic state and assumed<br />

control <strong>of</strong> Greek cities on the western<br />

coasts <strong>of</strong> the Black Sea. Based on the<br />

archeological evidence mentioned<br />

previously, he assumed the role <strong>of</strong> Asian<br />

Hellenistic royalty - a King <strong>of</strong> Kings. To<br />

be sure, Burebista aggressively pursued<br />

all that such a title implied, engaging in<br />

diplomatic and martial conquests well<br />

beyond the Dacian heartland during his<br />

reign. His rule stretched as far east as the<br />

Dnieper River in southern Russia, as far<br />

west as Moravia, and - just possibly -<br />

as far north as the Vistula River in<br />

southern Poland.<br />

Burebista’s aggressive policies touched<br />

the Roman world on several occasions.<br />

Through the subject Bastarnae tribe <strong>of</strong><br />

the northeast Balkans, he successfully<br />

competed against Roman attempts to grab<br />

Histria, one <strong>of</strong> the Mithradates’ orphaned<br />

cities, in 61 BC. He also warred against<br />

the Celtic tribes on his northwestern<br />

reaches. Most he conquered, but the Boii<br />

joined the Helvetians in their exodus to<br />

Gaul, which initiated Caesar’s Gallic<br />

<strong>War</strong>s. Burebista wielded enough strength<br />

that Pompey sought his friendship during<br />

the Civil <strong>War</strong>s and Caesar planned an<br />

expedition against the fractured Dacian<br />

kingdom after Burebista’s death during<br />

an uprising in 45 BC.<br />

DACIA AND ThE EARLy<br />

ROMAN PRINCIPATE<br />

The rebellion that claimed Burebista’s<br />

life broke the core <strong>of</strong> the Dacian kingdom<br />

into four or five smaller kingdoms and<br />

the farthest reaches <strong>of</strong> the old kingdom<br />

slipped away. This did not mean that the<br />

Dacians and Romans ended their mutual<br />

Balkan affairs. Octavius sought an<br />

alliance with the Dacian king Cotiso prior<br />

to his assumption <strong>of</strong> the imperial title,<br />

but declared a more adversarial attitude<br />

towards the Dacians <strong>of</strong>f and on during<br />

his 40-year reign. The Dacians and<br />

Bastarnae suffered defeat at the hands <strong>of</strong><br />

Crassus the Younger, one <strong>of</strong> Augustus’<br />

political rivals, in 29 BC. The Romans<br />

victoriously fought against them again<br />

in the Pannonian <strong>War</strong> (13-11 BC), and<br />

reportedly settled 50,000 Dacians within<br />

Roman territory after a major campaign<br />

in 11-12 AD.<br />

Above: The Dacians fought hard against the Roman invaders in 101 AD, staving <strong>of</strong>f Trajan and his desire for personal glory.

The Dacians enjoyed mostly peaceful<br />

relations with the empire for the next<br />

70 years, benefiting from an increase in<br />

imported Roman goods. The Sarmatian<br />

Iazyges complicated things for all<br />

parties, warring against and allying<br />

with both the Romans and Dacians at<br />

different times. The Dacian kingdom<br />

retrenched in Transylvania before the<br />

middle <strong>of</strong> the century, about 40 AD. To<br />

Rome’s relief, they declined to interfere<br />

in the imperial wars <strong>of</strong> succession that<br />

originated in Nero’s death in the Year <strong>of</strong><br />

Four Emperors (69 AD), although they<br />

couldn’t but help themselves to minor<br />

raiding in Moesia.<br />

ThE AGE Of DECEBAL<br />

Decebal was the last great Dacian king.<br />

He came to power at the beginning <strong>of</strong><br />

Domitian’s Dacian wars in the mid/late<br />

80s and he fell with his kingdom 20 years<br />

later to Trajan. Roman historian Cassius<br />

Dio lauded Decebal for his diplomatic<br />

and strategic talents. The wily king<br />

managed to keep his power despite long<br />

odds and refused to let Rome humiliate<br />

him in its final triumph.<br />

Emperor Domitian began his war against<br />

King Duras and the Dacians in response<br />

to their spectacular plundering <strong>of</strong> Moesia<br />

in 86 AD (they even slew the provincial<br />

governor in battle). Cornelius Fuscus,<br />

the Praetorian Guard commander,<br />

successfully led the Roman army in its<br />

restorative operations in the devastated<br />

province, completely repelling the raiding<br />

warbands. In the wake <strong>of</strong> their reverses in<br />

Moesia, Duras stepped down and Decebal<br />

took the Dacian kingship and prepared<br />

for the inevitable punitive campaign even<br />

as he dispatched embassies to negotiate<br />

peace.<br />

The Romans invaded Dacia nevertheless,<br />

and the armies decisively clashed at<br />

a mountain pass in 87 AD. Decabal’s<br />

showdown with Fuscus ended<br />

disastrously for the Romans. The Dacians<br />

inflicted massive casualties (including<br />

Fuscus) on their enemy, and captured<br />

many prisoners, standards, and weapons.<br />

The following year Tettius Julianus<br />

waged a promising campaign, defeating<br />

the Dacians at Tapae (in Transylvania).<br />

The Romans stopped short <strong>of</strong> absolutely<br />

conquering Dacia and turned their<br />

attention to the troublesome Sarmatians,<br />

Marcomanni, and Quadi. Rome accepted<br />

Dacia as a client state, re-establishing<br />

peace and a flow <strong>of</strong> gifts, goods, and<br />

skilled craftsmen.<br />

Despite his submission to Domitian,<br />

Decebal still stood in a position <strong>of</strong> power.<br />

Friendship with Rome rarely failed<br />

to elevate one’s status, and surely he<br />

benefited from his client status. Cassius<br />

Dio advises us that his onerous pride<br />

and receipt <strong>of</strong> Roman stipends provoked<br />

Top: The Dacians were one <strong>of</strong> the few “barbarian tribes” that employed war machines.<br />

Above: As the Second Dacian <strong>War</strong> drew to a close only small pockets <strong>of</strong> resistance held out.<br />

Trajan to war at the turn <strong>of</strong> the century.<br />

Considering the lack <strong>of</strong> threatening<br />

Dacian activity, the roots <strong>of</strong> Trajan’s<br />

wars against Decebal sprang more from<br />

his desire for personal glory and than a<br />

necessary defense <strong>of</strong> the empire.<br />

Trajan waged his first bloody war with<br />

Dacia in 101-102, and the second in<br />

105-106. Despite the harsh terrain and<br />

foes, the massive Roman army (and its<br />

many auxiliaries and mercenaries) fought<br />

until much <strong>of</strong> Dacia accepted Trajan’s<br />

authority and Decebal surrendered short<br />

<strong>of</strong> his removal and the destruction <strong>of</strong> his<br />

capital, Sarmizegethusa. The short-lived<br />

peace witnessed both side preparing for<br />

war again, and the following campaign<br />

saw the destruction <strong>of</strong> the Dacian capital<br />

and the transformation <strong>of</strong> the kingdom<br />

into another Roman province. Decebal<br />

committed suicide before his capture<br />

and Trajan displayed his head in the<br />

triumphal march in Rome.<br />

GAMING ROME’S DACIAN WARS<br />

The Dacians <strong>of</strong>fer a lot <strong>of</strong> interesting<br />

options to players who enjoy games<br />

that match Roman armies against<br />

barbarian opponents. Seriously, how<br />

many <strong>of</strong> Rome’s tribal enemies normally<br />

employed siege artillery in their own<br />

defense? Any attempts to replicate<br />

Rome’s Dacian campaigns should include<br />

challenging elements such as rough/<br />

wooded terrain and fortifications, plus<br />

contingents <strong>of</strong> Sarmatian cavalry and<br />

other auxiliaries.

DACIAN ARMy LISTS<br />

A number <strong>of</strong> rulesets place the Dacians<br />

in some kind <strong>of</strong> ‘other’ category when it<br />

comes to interpreting how they should<br />

work on the tabletop. Essentially, most<br />

games focus on one or more <strong>of</strong> these<br />

attributes when it comes to differentiating<br />

them from other contemporary<br />

barbarians: weaponry, discipline, and<br />

adaptability.<br />

The famous Dacian falx sometimes<br />

assumes the role <strong>of</strong> a significant combat<br />

factor, usually meaning that players field<br />

at least one superior unit <strong>of</strong> warriors<br />

armed with the weapon. De Bellis<br />

Antiquitatis, <strong>War</strong>master Ancients, and<br />

<strong>War</strong>hammer Ancient Battles both note<br />

the falx in their army lists. The existence<br />

WARhAMMER ANCIENT BATTLES<br />

VARIANT DACIAN LISTS<br />

The Dacians appear as variant Barbarian armies in WAB,<br />

first under Mountain Tribesmen in the core rules, and in the<br />

Barbarian Tribes appendix <strong>of</strong> Armies <strong>of</strong> Antiquity. Units <strong>of</strong><br />

these light infantry warbands may be armed with falxes,<br />

which the rules equate with two-handed weapons or halberds.<br />

Neither list allows the purchase <strong>of</strong> siege artillery. With a few<br />

tweaks, players may create other playable <strong>version</strong>s <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Dacian army. For example:<br />

• Players do not have to build entire units <strong>of</strong> falx-armed<br />

warriors, but may combine them with groups <strong>of</strong> infantry<br />

equipped with mixed weapons. Purchase shields, heavy<br />

<strong>of</strong> large Dacian formations strictly armed<br />

with falxes remains debatable, leaving<br />

the weapon’s impact on rules mechanics<br />

open to interpretation. The bow features<br />

prominently in many rules lists as well,<br />

usually in the hands <strong>of</strong> skirmishers.<br />

<strong>War</strong>master Ancients and <strong>War</strong>hammer<br />

Ancient Battles (WAB) both allow<br />

sizeable bodies <strong>of</strong> archers. Dacian army<br />

lists lack siege artillery in most game<br />

systems, with the notable exception <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>War</strong>master Ancients. Consider amending<br />

the unit rosters for scenarios in which<br />

the Dacians defend their homeland, and<br />

especially if they garrison fortifications.<br />

The most commonly addressed<br />

characteristic regards the Dacians’<br />

compatibility with the given game<br />

system’s warband rules, which typically<br />

give massed barbarian infantry an<br />

advantageous hard-charging shock value<br />

sometimes paired with tendencies toward<br />

compulsive moves and attacks. More<br />

<strong>of</strong>ten than not, the Dacians play the same<br />

as other barbarians in <strong>this</strong> respect for<br />

most miniature wargames. Some rulesets<br />

do not require the Dacians to make<br />

uncontrolled charges, differentiating them<br />

from other warband types.<br />

The Dacians fought well against the<br />

Roman armies that invaded their<br />

mountainous kingdom despite their<br />

eventual capitulation. Some rules handle<br />

them no differently from any other<br />

barbarian warband in rough ground and<br />

woods, while others treat them as light<br />

infantry types well-suited to such<br />

limiting ground.<br />

Above: The Dacians were very familiar with fighting in rough, forested terrain, the kind <strong>of</strong> terrain that broke up Roman formations.<br />

throwing spears, and javelins (+2 points per model).<br />

Note that no actual heavy throwing spears enter play,<br />

but their rules give the Dacians that extra punch.<br />

• Players may use up to 25% <strong>of</strong> the Dacian army points to<br />

purchase artillery, such as bolt throwers and catapults,<br />

in a siege scenario. This is WAB canon, per<br />

Siege & Conquest (p. 22).<br />

• Finally, players may use the Early Slavs list from the<br />

supplement Byzantium: Beyond the Golden Gate as a<br />

viable substitute. The Leadership values seem a bit low for<br />

the Dacians’ reputation, but the cavalry-to-infantry ratios,<br />

equipment options, and the Balkan Ruse special rule do much<br />

to commend its use.

COLLECTING A DACIAN ARMy<br />

Gamers and modelers do not need too<br />

look very hard to find miniature Dacians<br />

in a healthy range <strong>of</strong> scales, molded in<br />

metal and plastic (both s<strong>of</strong>t and hard).<br />

foundry, Old Glory, and <strong>War</strong>lord<br />

Games all market Dacian figures in<br />

25mm/28mm. foundry and <strong>War</strong>lord<br />

Games also include actual Dacian<br />

artillerists in their ranges, negating the<br />

need to supply stand-in or converted<br />

figures. Old Glory and Essex produce<br />

Dacian figures in 15mm. Magister<br />

Militum, Old Glory, and Pendraken<br />

mold them in 10mm, and Baccus 6mm<br />

has a Dacian range. haT Industries<br />

manufacture s<strong>of</strong>t plastic 1/72 scale<br />

Dacian figures. Collectors may obtain<br />

Sarmatian allies and foes as easily as they<br />

can purchase Dacian miniatures.<br />

Ancient Celt figures make great<br />

additions for a Dacian army. Their<br />

tribes not only existed at the edge <strong>of</strong><br />

the Dacian kingdom, but within it as<br />

well. Many tribal German miniatures<br />

pass can for rank and file Dacians so<br />

long as one avoids things that seem out<br />

<strong>of</strong> place (Suebian knots and fur jackets<br />

especially). A few Sarmatian infantry<br />

won’t spoil the look, either (Old Glory<br />

make them in 25mm/28mm scale). A<br />

good mix <strong>of</strong> appropriate miniatures<br />

stands to turn any Dacian army into a<br />

horde <strong>of</strong> barbarians that really sticks out<br />

on the table.<br />

CONVERSIONS<br />

Hard plastic miniatures brim with<br />

potential for easily creating awesome<br />

25mm/28mm Dacian characters equipped<br />

with Roman armor, shields, and weapons.<br />

PRIMARy SOURCES<br />

Cassius Dio (trans. Earnest Cary), Roman History (books<br />

67 & 68), Loeb Classical Library Harvard University Press,<br />

1914-1927<br />

Online public domain work: http://penelope.uchicago.edu/<br />

Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Cassius_Dio/home.html<br />

MODERN REfERENCES<br />

Gábor Vékony, Dacians-Romans-Romanians, Matthias<br />

Corvinus Publishing, Toronto-Buffalo, 2000 (Originally<br />

published by Akadémiai Kiadó/Budapest, 1989)<br />

Online English translation: http://www.hungarian-history.hu/<br />

lib/chk/index.htm<br />

This book critically sifts through ancient sources and<br />

modern studies <strong>of</strong> the Dacians, and presents some interesting<br />

thoughts on Berobista’s kingdom and its relation to the<br />

great Mithradates Eupator’s Pontic realm. It helps readers<br />

understand why the Dacian kingdom was much more than an<br />

exotic tribal confederation.<br />

Kimberly Kagan, Redefining Roman Grand Strategy, The<br />

Journal <strong>of</strong> Military History, Vol. 70, No. 2 (Apr., 2006), pp.<br />

It could not be any easier to plunder<br />

bits and pieces (including a helmeted<br />

head or two) for cherished leaders and<br />

champions. With a little work, one may<br />

draft Roman miniatures into their Dacian<br />

army. A suitably dynamic Roman <strong>of</strong>ficer<br />

figure only needs a piece <strong>of</strong> barbarian<br />

equipment to turn him into a chieftain or<br />

king: a Dacian head, possibly wearing a<br />

native cap or helmet; a falx or longsword;<br />

or a Dacian oval shield. Roman arms<br />

could make their way into Dacian<br />

hands through gifts, battle trophies, and<br />

deserters. <strong>War</strong>lord Games manufactures<br />

hard plastic Dacians, Celts, Early<br />

Imperial legionaries (some <strong>of</strong> the Veteran<br />

figures have manicae) and auxiliaries.<br />

<strong>War</strong>games factory <strong>of</strong>fer Caesarian<br />

legionaries, Early Imperial auxiliary<br />

cavalry, and Celts.<br />

These are some <strong>of</strong> Magister Militum’s 10mm Dacian<br />

range. Even at <strong>this</strong> small scale, the characteristic<br />

falx and s<strong>of</strong>t caps are clearly evident.<br />

In addition to their hard plastic Dacian <strong>War</strong>band, <strong>War</strong>lord Games also<br />

produces these great, metal Celtic Archers, perfect to use as Dacian allies.<br />

333-362, Society for Military History.<br />

Available online through JSTOR: http://www.jstor.org<br />

This <strong>article</strong> reviews and measures numerous military policies<br />

and actions <strong>of</strong> the Roman emperor, army, and state from<br />

a high-level perspective. It recommends that readers view<br />

Trajan’s campaigns against Dacia (as well as Mesopotamia)<br />

as wars <strong>of</strong> conquest and personal/imperial glory, as opposed<br />

to anything like a proactive defense against aggression or<br />

improved (easily guarded) boundaries.<br />

The Deva Museum <strong>of</strong> Dacian and Roman Civilization:<br />

http://museum.worldwidesam.net/index.html<br />

This interesting Romanian museum has a lot <strong>of</strong> online content<br />

for students <strong>of</strong> the period and wargamers. Of special interest<br />

is the virtual photographic and topographical map tour <strong>of</strong><br />

Dacian fortresses: http://museum.worldwidesam.net/en/<br />

sarmi/contents.htm