Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

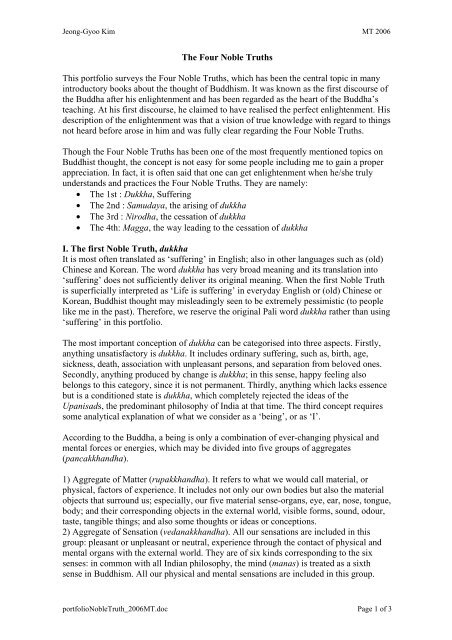

Jeong-Gyoo Kim MT 2006<br />

The <strong>Four</strong> <strong>Noble</strong> <strong>Truths</strong><br />

This portfolio surveys the <strong>Four</strong> <strong>Noble</strong> <strong>Truths</strong>, which has been the central topic in many<br />

introductory books about the thought of Buddhism. It was known as the first discourse of<br />

the Buddha after his enlightenment and has been regarded as the heart of the Buddha’s<br />

teaching. At his first discourse, he claimed to have realised the perfect enlightenment. His<br />

description of the enlightenment was that a vision of true knowledge with regard to things<br />

not heard before arose in him and was fully clear regarding the <strong>Four</strong> <strong>Noble</strong> <strong>Truths</strong>.<br />

Though the <strong>Four</strong> <strong>Noble</strong> <strong>Truths</strong> has been one of the most frequently mentioned topics on<br />

Buddhist thought, the concept is not easy for some people including me to gain a proper<br />

appreciation. In fact, it is often said that one can get enlightenment when he/she truly<br />

understands and practices the <strong>Four</strong> <strong>Noble</strong> <strong>Truths</strong>. They are namely:<br />

• The 1st : Dukkha, Suffering<br />

• The 2nd : Samudaya, the arising of dukkha<br />

• The 3rd : Nirodha, the cessation of dukkha<br />

• The 4th: Magga, the way leading to the cessation of dukkha<br />

I. The first <strong>Noble</strong> Truth, dukkha<br />

It is most often translated as ‘suffering’ in English; also in other languages such as (old)<br />

Chinese and Korean. The word dukkha has very broad meaning and its translation into<br />

‘suffering’ does not sufficiently deliver its original meaning. When the first <strong>Noble</strong> Truth<br />

is superficially interpreted as ‘Life is suffering’ in everyday English or (old) Chinese or<br />

Korean, Buddhist thought may misleadingly seen to be extremely pessimistic (to people<br />

like me in the past). Therefore, we reserve the original Pali word dukkha rather than using<br />

‘suffering’ in this portfolio.<br />

The most important conception of dukkha can be categorised into three aspects. Firstly,<br />

anything unsatisfactory is dukkha. It includes ordinary suffering, such as, birth, age,<br />

sickness, death, association with unpleasant persons, and separation from beloved ones.<br />

Secondly, anything produced by change is dukkha; in this sense, happy feeling also<br />

belongs to this category, since it is not permanent. Thirdly, anything which lacks essence<br />

but is a conditioned state is dukkha, which completely rejected the ideas of the<br />

Upanisads, the predominant philosophy of India at that time. The third concept requires<br />

some analytical explanation of what we consider as a ‘being’, or as ‘I’.<br />

According to the Buddha, a being is only a combination of ever-changing physical and<br />

mental forces or energies, which may be divided into five groups of aggregates<br />

(pancakkhandha).<br />

1) Aggregate of Matter (rupakkhandha). It refers to what we would call material, or<br />

physical, factors of experience. It includes not only our own bodies but also the material<br />

objects that surround us; especially, our five material sense-organs, eye, ear, nose, tongue,<br />

body; and their corresponding objects in the external world, visible forms, sound, odour,<br />

taste, tangible things; and also some thoughts or ideas or conceptions.<br />

2) Aggregate of Sensation (vedanakkhandha). All our sensations are included in this<br />

group: pleasant or unpleasant or neutral, experience through the contact of physical and<br />

mental organs with the external world. They are of six kinds corresponding to the six<br />

senses: in common with all Indian philosophy, the mind (manas) is treated as a sixth<br />

sense in Buddhism. All our physical and mental sensations are included in this group.<br />

portfolio<strong>Noble</strong>Truth_2006MT.doc Page 1 of 3

Jeong-Gyoo Kim MT 2006<br />

3) Aggregate of Perceptions (sannakkhandha). They are of six kinds, in relation to the six<br />

internal faculties and the corresponding six external objects like sensations. They are<br />

produced through the contact of our six faculties with the external world. It is the<br />

perceptions that recognise objects whether physical or mental.<br />

4) Aggregate of Mental Formations (samkharakkhandha). It includes all volition activities<br />

both good and bad. What is generally known as kamma/karma comes under this group.<br />

The Buddha’s definition of kamma is volition. Volition is mental construction and mental<br />

activity.<br />

5) Aggregate of Consciousness (vinnanakkhandha). Consciousness is a reaction or<br />

response which has one of the six faculties (eye, ear, nose, tongue, body and mind) as its<br />

basis, and one of the six corresponding external phenomena (visible forms, sound, odour,<br />

taste, tangible things and mind-objects, i.e., an idea and thought) as its object.<br />

Considering this analysis of a ‘being’, the existence as an ordinary human being is itself<br />

ddukha since every segment of one’s life span is composed of events having at least one<br />

of these aspects of dukkha. Therefore, the Buddha said: ‘in short these 5 aggregates of<br />

attachment are dukkha’.<br />

II. The origin of dukkha<br />

The origin of dukkha is said to be thirst or craving, tanha. It is craving which produces<br />

rebirth, companied by passionate clinging, and welcoming this and that. It is the craving<br />

for sensual pleasure, craving for existence and becoming, and craving for non-existence<br />

(self-annihilation). Craving occurs usually, but clearly not necessarily, from all sensory<br />

experience, including mental experiences.<br />

Thirst/craving is considered as the cause or origin of dukkha, which depends for its rising<br />

on something else, which is sensation, and sensation arises depending on contact, and so<br />

on and so forth goes on the circle which is known as Conditioned Genesis. So thirst is not<br />

the first or the only cause of the arising of dukkha, but it is the most obvious and<br />

immediate cause and principal thing. Thirst can be regarded as the emotional cause of<br />

dukkha; on the other hand, the cognitive cause is ignorance or misconception. Ignorance<br />

here means ignorance of the <strong>Four</strong> <strong>Noble</strong> <strong>Truths</strong>. In other words, it is not knowing things<br />

as they truly are, or oneself as one really is. It clouds all right understanding.<br />

These are the cause of arising dukkha, and this is found within the Aggregate of Mental<br />

Formations. In the Buddhist theory of karma, it means only ‘volitional action’, not all<br />

action which often misunderstood or inappropriately used. In Buddhist terminology<br />

karma never means effect; its effect is known as the ‘fruit’ or ‘result’ of karma.<br />

III. The cessation of dukkha<br />

The cessation of dukkha is nirvana. Since dukkha results from thirst/craving, it follows<br />

that if craving can be completely eliminated, dukkha will come to an end. To eliminate<br />

dukkha completely, one has to eliminate the main root of dukkha: thirst/craving and<br />

ignorance. Therefore, Nirvana is known also by the term tanhakkaya, ‘Extinction of<br />

Thirst’.<br />

However, the question of what is nirvana can never be answered completely and<br />

satisfactorily in words since it can be understood upon having experienced it. A few<br />

definitions and description of Nirvana found in Pali texts are: it is the complete cessation<br />

of that ‘thirst’, giving it up, renouncing it, emancipation from it, and detachment from it.<br />

That is the extinction of desire, the extinction of hatred, the extinction of illusion. The<br />

portfolio<strong>Noble</strong>Truth_2006MT.doc Page 2 of 3

Jeong-Gyoo Kim MT 2006<br />

abandoning and destruction of thirst and craving for these five Aggregates of Attachment:<br />

that is the cessation of dukkha.<br />

Nirvana is understood as liberation, and is broadly speaking the result of letting go, letting<br />

go the very forces of craving which power continued experiences of pleasure and<br />

inevitably suffering throughout this life, death, rebirth, and redeath. It is the complete and<br />

permanent cessation of all types of suffering, resulting from letting-go the forces of<br />

craving and due to overcoming ignorance through seeing things the way they really are.<br />

IV. The way to leading to the cessation of dukkha<br />

The way is called the ‘eightfold path’. The path is described as the ‘middle path’ in the<br />

Buddha’s early discourse in the sense that it is the middle path between two extremes:<br />

devotion to the indulgence of sense-pleasure and devotion to the self-mortification. The<br />

Buddha himself experienced both extremes and concluded that such asceticism could not<br />

bring to liberation. The Buddha equally understood liberation in psychological terms, as<br />

something to do with transforming the mind through correct understanding.<br />

The Buddhist path is the overcoming of greed, hatred, and delusion through the<br />

cultivation of their opposites: nonattachment, loving kindness, and wisdom or insight.<br />

The way is composed of eight factors, namely: Right understanding/view, Right thought/<br />

intention, Right speech, Right action, Right livelihood, Right effort, Right mindfulness,<br />

and Right concentration.<br />

All these should be developed simultaneously. These eight factors aim at promoting and<br />

perfecting the three essentials of Buddhist training and discipline: (a) Ethical conduct is<br />

built on the vast conception of universal love, and compassion for all living beings. Right<br />

speech, right action and right livelihood are classed under morality. (b) Wisdom: right<br />

view and right intention are classed under wisdom. (c) Mental discipline: the remaining<br />

factors, right effort, right mindfulness and right concentration, come under mental<br />

discipline.<br />

In all, the Buddha saw the problem of life correctly and analysed it. The Buddha’s<br />

analysis of ‘life’ and his suggestion of how to live are formulated into the <strong>Four</strong> <strong>Noble</strong><br />

<strong>Truths</strong>, which often referred to a medical diagnosis. The <strong>Four</strong> <strong>Noble</strong> <strong>Truths</strong> state the<br />

illness, the source of illness, the cure for the illness, and finally the way to lead to that<br />

cure. Hence, in Buddhism, knowing/ understanding what I am and seeing things the way<br />

they are exactly are very much emphasized. Then the knowing should be followed by<br />

experiencing or practicing to get enlightened. Buddha’s teaching described in the <strong>Four</strong><br />

<strong>Noble</strong> Truth is liberation of mind and liberation by wisdom.<br />

References:<br />

R. Gombrich, Lecture, OUDCE, MT 2006.<br />

W. Rahula, What the Buddha taught. Oneworld Publications, (including texts)1959.<br />

P. Williams, Buddhist thought. Routledge, 2003.<br />

R. Gethin, The foundations of Buddhism. Oxford University Press, 1998.<br />

portfolio<strong>Noble</strong>Truth_2006MT.doc Page 3 of 3