1 CHAPTER 1: AMERICAN INDIAN SELF-DETERMINATION AND ...

1 CHAPTER 1: AMERICAN INDIAN SELF-DETERMINATION AND ...

1 CHAPTER 1: AMERICAN INDIAN SELF-DETERMINATION AND ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

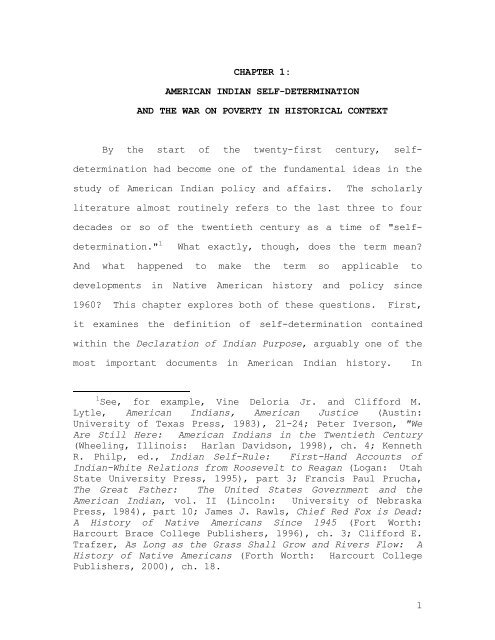

<strong>CHAPTER</strong> 1:<br />

<strong>AMERICAN</strong> <strong>INDIAN</strong> <strong>SELF</strong>-<strong>DETERMINATION</strong><br />

<strong>AND</strong> THE WAR ON POVERTY IN HISTORICAL CONTEXT<br />

By the start of the twenty-first century, self-<br />

determination had become one of the fundamental ideas in the<br />

study of American Indian policy and affairs. The scholarly<br />

literature almost routinely refers to the last three to four<br />

decades or so of the twentieth century as a time of "self-<br />

determination." 1 What exactly, though, does the term mean?<br />

And what happened to make the term so applicable to<br />

developments in Native American history and policy since<br />

1960? This chapter explores both of these questions. First,<br />

it examines the definition of self-determination contained<br />

within the Declaration of Indian Purpose, arguably one of the<br />

most important documents in American Indian history. In<br />

1 See, for example, Vine Deloria Jr. and Clifford M.<br />

Lytle, American Indians, American Justice (Austin:<br />

University of Texas Press, 1983), 21-24; Peter Iverson, "We<br />

Are Still Here: American Indians in the Twentieth Century<br />

(Wheeling, Illinois: Harlan Davidson, 1998), ch. 4; Kenneth<br />

R. Philp, ed., Indian Self-Rule: First-Hand Accounts of<br />

Indian-White Relations from Roosevelt to Reagan (Logan: Utah<br />

State University Press, 1995), part 3; Francis Paul Prucha,<br />

The Great Father: The United States Government and the<br />

American Indian, vol. II (Lincoln: University of Nebraska<br />

Press, 1984), part 10; James J. Rawls, Chief Red Fox is Dead:<br />

A History of Native Americans Since 1945 (Fort Worth:<br />

Harcourt Brace College Publishers, 1996), ch. 3; Clifford E.<br />

Trafzer, As Long as the Grass Shall Grow and Rivers Flow: A<br />

History of Native Americans (Forth Worth: Harcourt College<br />

Publishers, 2000), ch. 18.<br />

1

particular, the Declaration saw the maintenance of a "trust<br />

relationship" or "special relationship" between Native<br />

Americans and the United States as the key to self-<br />

determination. Second, the chapter offers a brief overview<br />

of the historical context in which self-determination<br />

emerged. In particular, the role of the War on Poverty in<br />

the 1960s is found to be a key factor in the emergence and<br />

eventual triumph of self-determination. More specifically,<br />

the War on Poverty facilitated self-determination by<br />

strengthening the trust relationship between the United<br />

States and Native American nations.<br />

The Declaration of Indian Purpose<br />

and the Components of Self-Determination<br />

"The year 1961 was a kind of watershed in Indian<br />

affairs," observed author D'Arcy McNickle (Salish-Kootenai). 2<br />

In June, after a series of regional meetings throughout the<br />

country, about 460 Native Americans from ninety Indian<br />

nations (along with observers from Canada and Mexico)<br />

attended the American Indian Chicago Conference (AICC). 3<br />

2 D'Arcy McNickle, Native American Tribalism: Indian<br />

Survivals and Renewals (London: Oxford University Press,<br />

1973), 115.<br />

3 For primary source information on the AICC and the<br />

regional meetings leading up to it, see Progress Report #2,<br />

22 February 1961; Sol Tax to All American Indians, 31 March<br />

1961; "Indians Meet Here to Discuss Problems," 23 June 1961;<br />

"The American Indian Chicago Conference: A Unique Experiment<br />

in Action Anthropology and Political Organization," n.d.; all<br />

documents in fd. 11, box 216, Sol Tax Papers, Department of<br />

Special Collections, University of Chicago Library, Chicago,<br />

Illinois. See also Progress Reports #4 and #5, 26 April<br />

2

Anthropologists Sol Tax and Nancy Lurie spearheaded the<br />

organization of the conference. The AICC had the support of<br />

the University of Chicago and the National Congress of<br />

American Indians (NCAI)--the largest and (at that time) the<br />

only nationwide, pan-tribal American Indian organization.<br />

Those in attendance drafted a Declaration of Indian Purpose,<br />

a statement of concerns and policy recommendations. 4<br />

1961, "American Indian Chicago Conference (Charter<br />

Convention), 1961)," series XI, box 148/5, National Congress<br />

of American Indian Papers, National Anthropological Archives,<br />

Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.<br />

For secondary accounts, see Thomas Clarkin, Federal<br />

Indian Policy in the Kennedy and Johnson Administrations<br />

(Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2001), 17-20;<br />

Thomas W. Cowger, The National Congress of American Indians:<br />

The Founding Years (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press,<br />

1999), 133-140; Laurence M. Hauptman, Tribes and<br />

Tribulations: Misconceptions About American Indians and<br />

Their Histories (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico<br />

Press, 1995), ch. 8; Alvin M. Josephy Jr., Now That the<br />

Buffalo's Gone: A Study of Today's American Indians (Norman:<br />

University of Oklahoma Press, 1982), 224; McNickle, Native<br />

American Tribalism, 115-117; Dorothy R. Parker, Singing an<br />

Indian Song: A Biography of D'Arcy McNickle (Lincoln:<br />

University of Nebraska Press, 1992), 187-191, 283.<br />

4 American Indian Chicago Conference (AICC), Declaration<br />

of Indian Purpose, 13-20 July 1961. The Declaration is<br />

reprinted in American Indian Policy Review Commission, Task<br />

Force Three, Report on Federal Administration and Structure<br />

of Indian Affairs (Washington: Government Printing Office,<br />

1976), 184-218; a partial reprint can be found in Alvin M.<br />

Josephy Jr., Joane Nagel, and Troy Johnson, Red Power: The<br />

American Indians' Fight for Freedom, 2d ed. (Lincoln:<br />

University of Nebraska Press, 1999), 13-15.<br />

For primary source information on the AICC and the<br />

regional meetings leading up to it, see Progress Report #2,<br />

22 February 1961; Sol Tax to All American Indians, 31 March<br />

1961; "Indians Meet Here to Discuss Problems," 23 June 1961;<br />

"The American Indian Chicago Conference: A Unique Experiment<br />

in Action Anthropology and Political Organization," n.d.; all<br />

3

According to historian Alvin M. Josephy Jr. and former NCAI<br />

Executive Director Robert Burnette (Rosebud Sioux), the<br />

Chicago Conference and the Declaration constituted a move<br />

toward "self-determination." 5<br />

To be sure, the creation of such a statement did not<br />

mean that the AICC participants were wholly united in their<br />

views. The proceedings of a series of regional meetings<br />

leading up to Chicago and the discussions at the conference<br />

itself revealed deep divisions. For example, Eastern and<br />

Western Indians clashed on several issues. A few critics<br />

felt that "elitist insiders" dominated the conference. 6<br />

documents in fd. 11, box 216, Sol Tax Papers, Department of<br />

Special Collections, University of Chicago Library, Chicago,<br />

Illinois. See also Progress Reports #4 and #5, 26 April<br />

1961, "American Indian Chicago Conference (Charter<br />

Convention), 1961)," series XI, box 148/5, National Congress<br />

of American Indian Papers, National Anthropological Archives,<br />

Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.<br />

For secondary accounts, see Thomas Clarkin, Federal<br />

Indian Policy in the Kennedy and Johnson Administrations<br />

(Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2001), 17-20;<br />

Thomas W. Cowger, The National Congress of American Indians:<br />

The Founding Years (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press,<br />

1999), 133-140; Laurence M. Hauptman, Tribes and<br />

Tribulations: Misconceptions About American Indians and<br />

Their Histories (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico<br />

Press, 1995), chapter 8; Alvin M. Josephy Jr., Now That the<br />

Buffalo's Gone: A Study of Today's American Indians (Norman:<br />

University of Oklahoma Press, 1982), 224; McNickle, Native<br />

American Tribalism, 115-117; Dorothy R. Parker, Singing an<br />

Indian Song: A Biography of D'Arcy McNickle (Lincoln:<br />

University of Nebraska Press, 1992), 187-191, 283.<br />

5 Alvin M. Josephy Jr., Red Power: The American Indians'<br />

Fight for Freedom, 1st ed. (New York: McGraw Hill, 1971),<br />

38; Philp, Indian Self-Rule, 211.<br />

6 Hauptman, Tribes and Tribulations, 99, 102-106; John<br />

4

Nevertheless, the Declaration identified several factors<br />

critical to self-determination: (1) the concept of inherent<br />

sovereignty and protection of Indian lands and resources, (2)<br />

federal services to tribes and opportunities for self-<br />

administration, and (3) preservation of distinctive Indian<br />

cultures. These factors make up what has come to be known as<br />

the "trust relationship" or "special relationship" between<br />

Indian nations and the federal government (although the<br />

Declaration did not use either of these specific phrases). 7<br />

Fahey, Saving the Reservation: Joe Garry and the Battle to<br />

be Indian (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2001),<br />

175; Progress Report No. 4, 26 April 1961.<br />

7 On trust relationship, see American Indian Policy Review<br />

Commission, Final Report, vol. I (Washington: Government<br />

Printing Office, 1977), 121-132; Robert L. Bennett, "Workshop<br />

on Tribal Government: National Congress of American<br />

Indians," 8 December 1959, fd. 12, box 16, series VI, William<br />

Zimmerman Papers, Center for Southwestern Research; National<br />

Tribal Chairmen's Association (NTCA), "The American Indian<br />

World," 9 February 1974, no fd., box 65, National Tribal<br />

Chairmen's Association Papers, National Anthropological<br />

Archives, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.; D'Arcy<br />

McNickle, Mary E. Young, and W. Roger Buffalohead, "Captives<br />

Within a Free Society: Federal Policy and the American<br />

Indian," chapter 2/part III, no fd., box 14, D'Arcy McNickle<br />

Papers, Newberry Library, Chicago, Illinois; Felix S. Cohen's<br />

Handbook of Federal Indian Law, 1982 ed. (Charlottesville,<br />

Virginia: Michie Bobbs-Merrill, 1982), 220-228; Vine Deloria<br />

Jr., "Trouble in High Places: Erosion of American Indian<br />

Rights to Religious Freedom in the United States," in The<br />

State of Native America: Genocide, Colonization, and<br />

Resistance, ed. M. Annette Jaimes (Boston: South End Press,<br />

1992), 271-273; Gilbert L. Hall, The Federal-Indian Trust<br />

Relationship: A Duty of Protection (Washington, D.C., 1979),<br />

2-3; National Congress of American Indians (NCAI), Historical<br />

Tribal Policies and Priorities, 1944-1975 (1989), 3; Philp,<br />

Indian Self-Rule, 302-310; David E. Wilkins and K. Tsianina<br />

Lomawaima, Uneven Ground: American Indian Sovereignty and<br />

5

Some observers might disagree over the relative importance of<br />

any given aspect of the relationship. Nevertheless, taken as<br />

a whole, the AICC's statement articulated a conception of<br />

self-determination relevant to a broad range of American<br />

Indian societies.<br />

Inherent Sovereignty and Protection of Lands and Resources<br />

Self-determination begins with the concept of inherent<br />

sovereignty. As the Declaration put it, "The right of self-<br />

government, a right the Indians possessed before the coming<br />

of the white man, has never been extinguished." 8 What this<br />

means is that American Indian nations' right to rule<br />

themselves did not and does not stem from a grant of power<br />

from the federal government. Rather, because tribes had<br />

existed separate from and prior to the creation of the United<br />

States, they had and have inherent sovereignty. While the<br />

expansion of United States power over the tribes' territory<br />

eroded some of their sovereignty, their right to self-rule<br />

had endured. 9<br />

Federal Law (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2001),<br />

64-97; Charles F. Wilkinson, American Indians, Time, and the<br />

Law: Native Societies in a Modern Constitutional Democracy<br />

(New Haven, Conn., 1987), 85-86.<br />

8 AICC, Declaration, 16.<br />

9 USDOI, Federal Indian Law, 395-396; AIPRC, Final Report,<br />

vol. 1, 126; Deloria, Behind the Trail, ch. 6; Deloria and<br />

Lytle, Nations Within, 158-161; Gerard, interview; O'Brien,<br />

American Indian Tribal Governments, 196; Prucha, American<br />

Indian Treaties, 2-9.<br />

6

Such sovereignty was often recognized by the United<br />

States through treaties and trust-protected lands.<br />

Throughout the late eighteenth and much of the nineteenth<br />

century, the United States entered into treaties with many<br />

Native peoples. The treaties--which usually involved Indians<br />

ceding land or agreeing to maintain peaceful relations with<br />

the United States--recognized that American Indian peoples<br />

had sovereignty. Certain court decisions, executive orders,<br />

and laws have also recognized inherent sovereignty. The<br />

classification of most reservation lands as "trust<br />

protected"--that is, occupied and used by the tribes but held<br />

"in trust" by the federal government--served to protect<br />

Native sovereignty. On the trust lands of the reservations,<br />

Indian nations and the federal government have jurisdiction;<br />

generally, states have no authority over Indian reservations,<br />

even those within a state's boundaries. (There have been and<br />

are some exceptions.) The trust relationship between tribes<br />

and the federal government also served to help preserve the<br />

Indians' lands by restricting the ability to sell, lease, or<br />

mortgage tribal territory. 10 The goal of the trust status<br />

was and is to prevent tribal lands and their resources from<br />

being taken or misused by non-Indian individuals or groups,<br />

10 AIPRC, Final Report, vol. 1, 126; Bennett, "Workshop on<br />

Tribal Government," 8 December 1959; Hall, Federal-Indian<br />

Trust Relationship, 2-3; Donald L. Fixico, The Invasion of<br />

Indian Country in the Twentieth Century: American Capitalism<br />

and Tribal Natural Resources (Niwot: University of Colorado<br />

Press, 1998), 177-178; Prucha, American Indian Treaties, 2-9.<br />

7

state governments, and/or federal agencies. (Of course, this<br />

goal has all-too-often not been met.) 11<br />

The loss of trust-protected lands--according to NCAI co-<br />

founder Archie Phinney (Nez Perce)--threatened Indians'<br />

existence. 12 Scholar Vine Deloria Jr. agrees. He has argued<br />

that "no people can continue" and "no government can<br />

function" unless "bound to a land area of its own." 13 So,<br />

the Indian land base allowed for the existence of Indian<br />

peoples and Indian self-determination, and the trust status<br />

helped preserve that land base. Admittedly, some Indian<br />

communities, especially in Oklahoma, have maintained tribal<br />

governments despite the loss of most if not all of their<br />

trust lands. Nevertheless, according to the AICC, "It is a<br />

universal desire among all Indians that their treaties and<br />

trust-protected lands remain intact and beyond reach of<br />

predatory men." 14 In addition, as will be discussed below,<br />

the trust relationship involves more than just land.<br />

Federal Services and Self-Administration<br />

11 O'Brien, American Indian Tribal Governments, 262.<br />

12 Archie Phinney, "Indian Thoughts about Indian Service,"<br />

n.d., 1, "NCAI Organizational Materials 1945," Box 1503,<br />

Portland Area Office, Record Group 75 (RG 75), Bureau of<br />

Indian Affairs (BIA), National Archives--Pacific Northwest<br />

Region (NAPNWR), Seattle, Washington. The NCAI consistently<br />

argued this point; see National Congress of American Indians<br />

(NCAI), Historical Tribal Policies and Priorities, 1944-1975,<br />

1989, 3.<br />

13 Deloria, Custer, 178-179.<br />

14 AICC, Declaration, 15.<br />

8

While tribes possessed an inherent right to run their<br />

own affairs, exercising self-determination proved far more<br />

difficult. Federal policies have all-too-often decimated<br />

Native American economies, and with it the ability to control<br />

and develop the economic resources necessary to exercise<br />

self-government. These federal policies have included<br />

dividing up tribal lands into individually-owned plots,<br />

allowing non-Indians to benefit from the use of Indian lands<br />

and resources at the expense of the tribes, reducing<br />

livestock herds, and flooding Native lands as part of water<br />

development projects. 15 Hence, many Indian peoples lacked<br />

the resources to effectively exercise their right to self-<br />

determination. 16<br />

Consequently, the AICC called on the federal government<br />

to live up to its "responsibilities" and its "positive<br />

national obligation" to assist tribes with developing their<br />

15 For just a few of the works on the subject, see<br />

Frederick E. Hoxie, A Final Promise: The Campaign to<br />

Assimilate the Indians, 1880-1920 (Cambridge: Cambridge<br />

University Press, 1984); Michael L. Lawson, Dammed Indians:<br />

The Pick-Sloan Plan and the Missouri River Sioux, 1944-1980<br />

(Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1982); Janet A.<br />

McDonnell, The Dispossession of the American Indian, 1887-<br />

1934 (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1991); Melissa<br />

L. Meyer, The White Earth Tragedy: Ethnicity and<br />

Dispossession at a Minnesota Anishinaabeg Reservation, 1889-<br />

1920 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1994); Richard<br />

White, The Roots of Dependency: Subsistence, Environment,<br />

and Social Change Among the Choctaws, Pawnees, and Navajos<br />

(Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1983).<br />

16 Gerard, interview.<br />

9

economies and providing services like health care and<br />

education. 17 Such assistance, and the identification of it<br />

as a federal responsibility, was an important part of the<br />

trust relationship and thus an important part of self-<br />

determination. The trust relationship between tribes and the<br />

United States involved not just land, but a moral and legal<br />

responsibility on the part of the federal government to aid<br />

Native Americans. 18 Such aid was and is owed to the tribes<br />

17 AICC, Declaration, 5-12; quotation taken from page 5.<br />

18 On trust relationship, see Robert L. Bennett, "Workshop<br />

on Tribal Government: National Congress of American<br />

Indians," Dec. 8, 1959, folder 12, box 16, series VI, William<br />

Zimmerman Papers, Center for Southwestern Research; Felix S.<br />

Cohen's Handbook of Federal Indian Law, 1982 ed.<br />

(Charlottesville, Virginia: Michie Bobbs-Merrill, 1982),<br />

220-228; Gerard interview; Gilbert L. Hall, The Federal-<br />

Indian Trust Relationship: A Duty of Protection (Washington,<br />

D.C., 1979); National Congress of American Indians (NCAI),<br />

Historical Tribal Policies and Priorities, 1944-1975 (1989),<br />

3; NCAI, "Treaties and Trust Responsibilities," 21 October<br />

1976, "National Congress of American Indians, 1976," box 5,<br />

Bradley H. Patterson Papers, Gerald R. Ford Library, Ann<br />

Arbor, Michigan; Donald L. Fixico, The Invasion of Indian<br />

Country in the Twentieth Century: American Capitalism and<br />

Tribal Natural Resources (Niwot, Colo., 1998), 177-178; David<br />

E. Wilkins and K. Tsianina Lomawaima, Uneven Ground:<br />

American Indian Sovereignty and Federal Law (Norman:<br />

University of Oklahoma Press, 2001), 64-97; David E. Wilkins,<br />

American Indian Politics and the American Political System<br />

(Lanhan, Maryland: Rowman and Littlefield, 2002), 44-45,<br />

339-340; Charles F. Wilkinson, American Indians, Time, and<br />

the Law: Native Societies in a Modern Constitutional<br />

Democracy (New Haven, Conn., 1987), 85-86.<br />

For a more critical view of the trust concept, see Frank<br />

Pommersheim, Braid of Feathers: American Indian Law and<br />

Contemporary Life (Berkeley: University of California Press,<br />

1995), 41-46; Francis Paul Prucha, The Indians in American<br />

Society: From the Revolutionary War to the Present<br />

(Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985), 91-92.<br />

10

in exchange for Indians ceding their lands to the United<br />

States. 19 As legal scholar Charles F. Wilkinson has<br />

observed, "the trust relationship extends to areas such as<br />

education, housing and health. . . . Congress has a moral<br />

obligation toward Indians." 20 Therefore, the AICC concluded<br />

that the federal government should make social and economic<br />

programs available to Native Americans at least until tribal<br />

governments could take them over. 21 Economic development<br />

activities in Indian Country would hasten that takeover by<br />

helping tribes to become more self-sufficient. As former<br />

Senator Benjamin Reifel (Rosebud Sioux) and authors Joe Sando<br />

(Jemez Pueblo) and Vine Deloria have argued, self-<br />

determination requires that tribes to have a solid economic<br />

base. 22<br />

Economic development and social programs were also<br />

important because they helped insure that there would be<br />

peoples in Indian Country to exercise their right to self-<br />

determination. High rates of Indian unemployment and<br />

poverty--combined with government relocation policies--played<br />

19 AIPRC, Final Report, vol. 1, 126-128; O'Brien, American<br />

Indian Tribal Governments, 261-262.<br />

20 Philp, Indian Self-Rule, 303; Charles F. Wilkinson,<br />

American Indians, Time, and the Law: Native Societies in a<br />

Modern Constitutional Democracy (New Haven: Yale University<br />

Press, 1987), 85-86.<br />

21 AICC, Declaration, 19-20; Gerard, interview.<br />

22 Deloria and Lytle, Nations Within, 258; Philp, Indian<br />

Self-Rule, 296; Sando, interview.<br />

11

a role in encouraging Native Americans to leave their home<br />

communities and move to urban areas. 23 Those most likely to<br />

relocate were individuals with skills and leadership<br />

abilities. To be sure, urban Indians often maintained ties<br />

with their tribe, and historian Donald L. Fixico has<br />

indicated that relocation's effect on tribal governments'<br />

effectiveness was uncertain. 24 Nevertheless, an increase in<br />

employment opportunities and services within Indian Country<br />

would be likely to help insure that tribes would have the<br />

leadership necessary to exercise self-determination.<br />

While the participants at Chicago advocated federal<br />

economic and social programs for Indians, the federal<br />

government frequently used the "trust responsibility" to<br />

justify administering existing programs in a paternalistic<br />

23 For examples of the lack of economic opportunity among<br />

several Southwestern tribal communities, see General<br />

Superintendent to Phillips, 5 December 1962, "C&S Packing<br />

Company-Isleta UPA," Box 2, 8NN-075-92-003, Albuquerque Area,<br />

BIA, RG 75, NARMR; "Summary Statement of Withdrawal Status,<br />

Alamo (Puertecito)," n.d., "053 Historical, Etc. Data Ute,"<br />

Box 10, 8NS-075-95-022, Albuquerque Area, BIA, RG 75, NARMR;<br />

"Overall Economic Development Program, Santo Domingo Indian<br />

Reservation, Santo Domingo Pueblo, New Mexico," n.d., Box 16,<br />

8NS-075-95-022, Albuquerque Area, BIA, RG 75, NARMR; Joseph<br />

G. Jorgensen, "Sovereignty and the Structure of Dependency at<br />

Northern Ute," American Indian Culture and Research Journal<br />

10:2 (1986): 82-83. Kenneth R. Philp, "Stride Toward<br />

Freedom: The Relocation of Indians to Cities, 1952-1960,"<br />

Western Historical Quarterly 16 (April 1985): 175-190.<br />

24 Ned Blackhawk, "I Can Carry on from Here: The<br />

Relocation of American Indians to Los Angeles," Wicazo Sa<br />

Review 2 (Fall 1995): 16-30; Fixico, Termination and<br />

Relocation, ch.7.<br />

12

fashion. Instead of working with Indian peoples to determine<br />

how to best address their needs, government officials imposed<br />

programs that they thought would be best. 25 The<br />

Declaration's authors opposed such paternalism. Non-Indians,<br />

no matter how well-intentioned, should not have the sole<br />

power to make decisions affecting Native peoples. Rather,<br />

policymakers needed to recognize and respect<br />

the desire on the part of Indians to participate in<br />

developing their own programs with help and guidance as<br />

needed and requested, from a local decentralized<br />

technical and administrative staff, preferably located<br />

conveniently to the people it serves. . . . The Indians<br />

. . . want to participate, want to contribute to their<br />

own personal and tribal improvements. 26<br />

Self-administration was not simply a procedural matter<br />

but constituted a vital component of self-determination. By<br />

accepting self-administration, government officials would<br />

recognize American Indian leaders' right to shape policies<br />

and programs affecting them. Such acceptance was important<br />

because Congress possessed plenary power over the tribes,<br />

which meant it had the legal authority to unilaterally alter<br />

the trust relationship and abrogate treaty provisions. 27<br />

25 See, for example, Ortiz, "Half a Century," 17. AIPRC,<br />

Final Report, 126-127.<br />

26 AICC, Declaration, 6.<br />

27 Deloria, Behind the Trail, ch. 7; Francis Paul Prucha,<br />

American Indian Treaties: The History of a Political Anomaly<br />

(Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994), 355-358;<br />

David E. Wilkins, The Masking of Justice: American Indian<br />

Sovereignty and the U.S. Supreme Court (Austin: University<br />

of Texas Press, 1997), 67-81.<br />

13

Thus, self-administration would help Native Americans to<br />

protect the trust relationship by insuring that the<br />

government did not simply impose policies on American Indians<br />

that would harm that relationship. 28<br />

Cultural Preservation<br />

A final component of the AICC's vision of self-<br />

determination was cultural preservation. As the Declaration<br />

explained,<br />

We believe in the inherent right of all people to retain<br />

spiritual and cultural values, and that the free<br />

exercise of these values is necessary to the normal<br />

development of any people. Indians exercised this<br />

inherent right to live their own lives for thousands of<br />

years before the white man came. 29<br />

Vine Deloria Jr. sees the maintenance of Native cultures--<br />

that is, cultural self-determination--as necessary for other<br />

kinds of self-determination. Cultural identity gives people<br />

a shared understanding of their world, their place in that<br />

world, and a way to adjust to changes. Such a shared<br />

understanding allows people to feel a common identity and to<br />

feel that they are part of a nation. The lack of a common<br />

cultural identity means that sovereignty cannot be exercised<br />

effectively because the people of a nation will feel no<br />

obligation to accept the decisions of the nation's leaders.<br />

Governments which lack the political support of their people<br />

cannot function well, if at all. Hence, preserving Native<br />

28 O'Brien, American Indian Tribal Governments, 266-267.<br />

29 AICC, Declaration, 5.<br />

14

cultures was necessary for tribal governments to operate and<br />

exercise meaningful self-determination and thus is part of<br />

the United States' responsibilities as part of the trust<br />

relationship. 30<br />

As can be seen, the components of the AICC's vision of<br />

self-determination are interconnected. The preservation of<br />

tribal cultural values required preservation of Indian lands<br />

and resources, which in turn required the maintenance of<br />

trust protection for those lands and resources. The trust<br />

relationship provided tribes with the right to federal<br />

economic and social assistance. This assistance helped<br />

insure that American Indians would remain in their homelands<br />

to shape and administer programs in a way consistent with<br />

tribal cultural values.<br />

The Context and Evolution of Self-Determination, 1945-1975<br />

Just as it is important to understand the interrelations<br />

between the Declaration's components of self-determination,<br />

it is also important to understand that the conference's<br />

conception of self-determination did not emerge in a vacuum.<br />

It stood out as the product of--and had an impact on--the<br />

history of Native peoples in the three decades after the<br />

Second World War. The period from 1945-1975 saw some of the<br />

most significant shifts in federal Indian policy. These<br />

30 Vine Deloria Jr., "Self-Determination and the Concept<br />

of Sovereignty," in Economic Development in American Indian<br />

Reservations, ed. Roxanne Dunbar Ortiz (Albuquerque:<br />

University of New Mexico Native American Studies, 1979), 27;<br />

Deloria and Lytle, Nations Within, 250-254.<br />

15

shifts ultimately moved policies away from attempts to break<br />

down tribal governments and societies and assimilate Native<br />

Americans into "mainstream" American society. The<br />

assimilationist agenda of the 1940s and 1950s--known as<br />

"termination"--would be replaced by one of "self-<br />

determination."<br />

From the Indian New Deal to Termination<br />

At the end of World War II, Indian policy was officially<br />

based on the "Indian New Deal." This policy had been<br />

initiated by Commissioner of Indian Affairs John Collier<br />

during the Franklin D. Roosevelt administration of 1933-1945,<br />

and it worked to reverse decades of efforts to assimilate<br />

Native Americans through allotment (ending tribal landholding<br />

in favor of individual ownership of land) and eradicating<br />

Native cultures. 31 Collier opposed government interference<br />

with tribal religious and cultural practices and won passage<br />

of the Indian Reorganization Act (IRA) of 1934. Among other<br />

provisions, the IRA ended allotment, created a revolving loan<br />

fund to underwrite Native American economic development<br />

projects, provided for placing more land under tribal<br />

control, and established a system through which Indian<br />

nations could set up elected governments. Granted, these IRA<br />

tribal governments suffered from significant problems. Among<br />

other things, they were limited in power, and they often<br />

supplanted existing traditional governments, which sometimes<br />

31 On assimilationist policies, see Hoxie, Final Promise.<br />

16

produced intratribal conflict. Nevertheless, the importance<br />

of Indian New Deal stemmed from its recognition that tribes<br />

had inherent right to self-determination. 32<br />

Not everyone saw Collier's policy as beneficial. The<br />

IRA had long been controversial, and by the 1940s its support<br />

among Indians and non-Indians alike had eroded. Many<br />

American Indians felt frustrated because the IRA had failed<br />

to bring the political and economic improvements promised by<br />

Collier. Consequently, some Native Americans desired to<br />

abolish federal oversight of Indian affairs and to enter more<br />

fully into mainstream society. 33 At least some non-Indians<br />

agreed. In 1943, Senate Report 310 condemned the IRA and<br />

32 The Indian New Deal has been the subject of a number of<br />

scholarly treatments, including Vine Deloria Jr. and Clifford<br />

M. Lytle, The Nations Within: The Past and Future of<br />

American Indian Sovereignty (New York: Pantheon Books,<br />

1984); Laurence M. Hauptman, The Iroquois and the New Deal<br />

(Syracuse, New York: Syracuse University Press, 1981);<br />

Lawrence C. Kelly, "The Indian Reorganization Act: The Dream<br />

and the Reality," Pacific Historical Review 45 (August 1975):<br />

291-312; Donald L. Parman, The Navajos and the New Deal (New<br />

Haven: Yale University Press, 1976); Kenneth R. Philp, John<br />

Collier's Crusade for Indian Reform, 1920-1954 (Tucson:<br />

University of Arizona Press, 1977); Philp, Indian Self-Rule,<br />

part 1; Paul C. Rosier, The Rebirth of the Blackfeet Nation,<br />

1912-1954 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2001);<br />

Elmer R. Rusco, A Fateful Time: The Background and<br />

Legislative History of the Indian Reorganization Act (Reno:<br />

University of Nevada Press, 2000); Graham D. Taylor, The New<br />

Deal and American Indian Tribalism: The Administration of<br />

the Indian Reorganization Act, 1934-1945 (Lincoln:<br />

University of Nebraska Press, 1980).<br />

33 Fixico, Termination and Relocation, 14-15, 17-18;<br />

Philp, Termination Revisited, 11.<br />

17

urged its abandonment. 34 American Indian service in the<br />

military convinced at least some Americans that Native<br />

Americans should be "rewarded" through assimilation into<br />

mainstream society. World War II and the subsequent Cold War<br />

placed a premium on national unity and made the continuation<br />

of distinctive American Indian communities seem subversive.<br />

In addition, a rising tide of fiscal conservatism emphasized<br />

cutting government spending and services. At the same time,<br />

a growing emphasis on racial integration among liberals<br />

discouraged support for preserving group identities. 35<br />

These trends led policymakers to replace the Indian New<br />

Deal with an assimilation-oriented policy known as<br />

"termination." Advocates of termination wanted to abolish<br />

(or "terminate") the trust status of Indian lands and special<br />

government services for American Indians. 36 Indian<br />

34 Philp, Indian Self-Rule, 115-116; John Collier, "The<br />

Senate Committee Again 'Reports' on Indian Affairs," 24<br />

October 1944, 1, Fd. 19, Box 82, Reel 18, Dennis Chavez<br />

Papers, Center for Southwestern Research (CSWR), University<br />

of New Mexico, Albuquerque, New Mexico.<br />

35 Fixico, Termination and Relocation, 14-15; Prucha,<br />

Great Father, 1015; Clayton R. Koppes, "From New Deal to<br />

Termination: Liberalism and Indian Policy, 1933-1953,"<br />

Pacific Historical Review XLVI (November 1977): 543-566.<br />

36 Works on termination include Larry W. Burt, Tribalism<br />

in Crisis: Federal Indian Policy, 1953-1961 (Albuquerque:<br />

University of New Mexico Press, 1982); Donald L. Fixico,<br />

Termination and Relocation: Federal Indian Policy, 1945-1960<br />

(Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1986); Larry<br />

J. Hasse, "Termination and Assimilation: Federal Indian<br />

Policy, 1943-1961" (Ph.D. diss., Washington State University,<br />

1974); R. Warren Metcalf, "Arthur V. Watkins and the Indians<br />

of Utah: A Study of Federal Termination Policy" (Ph.D.<br />

18

communities on trust lands were not subject to state<br />

jurisdiction. If the government removed the trust status,<br />

tribal laws in conflict with state laws would be null and<br />

void. In addition, Indian lands would be subject to state<br />

taxes. Once termination had been completed, its advocates<br />

expected that the government agency primarily responsible for<br />

Indian services--the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA)--would be<br />

liquidated. In other words, termination was a means of<br />

assimilating or "de-tribalizing" Indians. To facilitate this<br />

policy, the government also initiated a relocation program,<br />

which encouraged Native Americans to leave their home<br />

communities and move to urban areas. 37<br />

To be sure, the termination era had its roots in the<br />

years before and during World War II. It began in earnest,<br />

however, in 1950--during the presidential administration of<br />

Democrat Harry Truman--with the appointment of Dillon S. Myer<br />

as Commissioner of Indian Affairs. Myer, a government<br />

bureaucrat who managed the Japanese American internment camps<br />

during World War II, strongly favored assimilation and pushed<br />

for termination. 38 Myer characterized federal trusteeship<br />

diss., Arizona State University, 1995); R. Warren Metcalf,<br />

"Lambs of Sacrifice: Termination, the Mixed-Blood Utes, and<br />

the Problem of Indian Identity," Utah Historical Quarterly 64<br />

(Fall 1996): 322-343; Philp, Termination Revisited.<br />

37 Fixico, Termination, 183. Donald L. Fixico, The Urban<br />

Indian Experience in America (Albuquerque: University of New<br />

Mexico Press, 2000).<br />

38 Cowger, "'Crossroads,'" 127; Drinnon, Keeper, chs. 8-<br />

11; Clayton R. Koppes, "Oscar L. Chapman: A Liberal at the<br />

19

over Indian Country as paternalistic and as a cause of Indian<br />

segregation and poverty. The Commissioner's solution<br />

involved providing federal assistance to improve the Indians'<br />

economic and social status and then abrogating the trust<br />

relationship. 39 To this end, by January 1952, Myer's bureau<br />

had drafted proposed legislation to terminate Indian groups<br />

in Oregon and California. 40 While Myer emphasized that<br />

bureau policy called for consultation with the tribes, he<br />

nevertheless asserted that, in some cases, termination should<br />

be imposed regardless of Native American desires. 41<br />

The push for termination accelerated during the<br />

administration of Republican President Dwight D. Eisenhower<br />

from 1953-1961. Myer's successor was Glenn L. Emmons, a New<br />

Mexico banker active in state Republican party politics. The<br />

Interior Department, 1933-1953" (Ph.D. diss., University of<br />

Kansas, 1974), 220.<br />

39 Myer to Anderson, 20 April 1951, "Navajo-Hopi<br />

Rehabilitation Watch Dog Committee--S. 1407," Reel 19,<br />

Clinton P. Anderson Papers, CSWR; Dillon S. Myer, "The Needs<br />

of the American Indian," 12 December 1951, 2-3, "Myer, Dillon<br />

S.," Box 27, Helen Peterson Papers, National Anthropological<br />

Archives (NAA), Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.<br />

40 "Statement by Dillon S. Myer, Commissioner of Indian<br />

Affairs, Before a Subcommittee of the Senate Committee on<br />

Interior and Insular Affairs," 21 January 1952, 12, "Myer,<br />

Dillon S.," Box 27, Peterson Papers, NAA.<br />

41 Myer to Watkins, n.d., "Navajo-Hopi Rehabilitation<br />

Watch Dog Committee--S. 1407," reel 19, Anderson Papers,<br />

CSWR; Myer to All Bureau Officials, 5 August 1952, in United<br />

States Congress, House, Committee on Interior and Insular<br />

Affairs, House Report 2503, 82d Cong., 2d sess., 15 December<br />

1952, 3.<br />

20

new Commissioner favored the eventual abolition of federal<br />

trusteeship and maintained that such abolition could occur<br />

without tribal consent. 42 Congress concurred, and it passed<br />

two key termination measures in August 1953. The first,<br />

House Concurrent Resolution 108 (HCR 108), expressed the<br />

legislative branch's view that Native Americans "should be<br />

freed from Federal supervision" as soon as possible. 43<br />

Public Law 280 (PL 280), the second measure, allowed<br />

California, Minnesota, Nebraska, Oregon, and Wisconsin to<br />

assume criminal jurisdiction over all or most of the<br />

reservations within those states and allowed other states to<br />

assume jurisdiction if they so desired. 44<br />

With this legal structure in place, members of Congress-<br />

-particularly Republican Senator Arthur V. Watkins of Utah--<br />

began pushing legislation to terminate specific Indian<br />

42 "Address to be Delivered by Commissioner of Indian<br />

Affairs Glenn L. Emmons at Meetings with Indian Tribal<br />

Groups," September 1953, 10, Fd. 12, Box 2, Reel 3, Glenn L.<br />

Emmons Papers, CSWR.<br />

43 House Concurrent Resolution 108, Statues at Large, vol.<br />

67 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1953), B132.<br />

44 Public Law 280, Statutes at Large, vol. 67 (Washington:<br />

Government Printing Office, 1953), 588-590. Eventually,<br />

Alaska, Florida, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, and Washington<br />

became PL 280 states. Several states assumed jurisdiction<br />

over reservations prior to PL 280's passage: North Dakota,<br />

Iowa, Kansas, and New York. T.J. Reardon Jr. to Frank<br />

Lorenz, 4 June 1962, "IN/S," box 380, WHCF, Subject Files,<br />

JFKL; untitled document, n.d., "Jurisdiction over Indian<br />

Lands (PL 280) - General," box 3, Bradley H. Patterson Files,<br />

Gerald R. Ford Library, Ann Arbor, Michigan.<br />

21

eservations and communities. The Menominees of Wisconsin<br />

and Klamaths of Oregon stood out as the two largest tribes to<br />

be terminated during the 1950s. Congress subjected many<br />

smaller groups to the same policy, including the Southern<br />

Paiutes and mixed-blood Utes of Utah, the Alabama-Coushattas<br />

of Texas, many of the ranchería Indians in California, and<br />

the peoples of the Siletz and Grand Ronde reservations in<br />

Oregon. 45<br />

The Shift from Termination to Self-Determination<br />

The withdrawal of trusteeship had disastrous<br />

consequences, especially for the Menominees and the Klamaths.<br />

Termination resulted in the loss of federal lumber contracts,<br />

and the assessment of state taxes forced the Menominees to<br />

sell off hunting and fishing lands. The Menominees'<br />

hospital, lacking adequate funding, closed because it could<br />

not meet state licensing standards. Consequently, health and<br />

unemployment problems skyrocketed. Menominees also<br />

experienced an erosion of their cultural distinctiveness. 46<br />

The Klamath tribe disintegrated after termination, with many<br />

members ending up in prison or mental institutions. 47<br />

45 Vine Deloria Jr. and Clifford M. Lytle. American<br />

Indians, American Justice (Austin: University of Texas<br />

Press, 1983), 18; Fixico, Termination, 122.<br />

46 Nicholas C. Peroff, Menominee Drums: Tribal<br />

Termination and Restoration, 1954-1974 (Norman: University<br />

of Oklahoma Press, 1982), 169-173.<br />

47 U.S. Congress, Senate, Committee on Labor and Public<br />

Welfare, Indian Education: A National Tragedy--A National<br />

Challenge, Report 91-501, 91st Cong., 1st sess., 1969, 17;<br />

22

By the late 1950s and during the 1960s, such failures<br />

helped erode government officials' support for termination,<br />

but other reasons explain the declining support as well. 48<br />

Historian Thomas W. Cowger has argued persuasively that<br />

lobbying by the pan-tribal National Congress of American<br />

Indians (NCAI) played a key role in weakening policymakers'<br />

support for termination. 49 In 1954, for example, the NCAI<br />

held an "Emergency Conference of American Indians on<br />

Legislation" in Washington, D.C. to fight against<br />

termination. Native Americans from twenty-one states and the<br />

Alaska territory came to Washington, where they testified<br />

before Congressional committees and met with members of<br />

Congress, the Interior Department, and other government<br />

agencies. 50 In this context, the NCAI helped put on the<br />

American Indian Chicago Conference to express its opposition<br />

to termination. Undoubtedly hoping to shape policy, a<br />

delegation of American Indians presented a copy of the<br />

Declaration of Indian Purpose to President John F. Kennedy in<br />

1962, but he apparently paid little attention to the<br />

Drinnon, Keeper, xxvi.<br />

48 Nagel, American Indian Ethnic Renewal, 220.<br />

49 Thomas W. Cowger, "'The Crossroads of Destiny': The<br />

NCAI's Landmark Struggle to Thwart Coercive Termination,"<br />

American Indian Culture and Research Journal 20:4 (1996):<br />

127; Cowger, National Congress, ch. 5.<br />

50 "Emergency Conference of American Indians on<br />

Legislation," 25-28 February 1954, "Emergency Conference,"<br />

Box 32, Peterson Papers, NAA.<br />

23

document's content. 51 Nevertheless, the Declaration helped<br />

clarify the meaning of what would come to be known as self-<br />

determination. 52<br />

Sociologist Joane Nagel agrees with Cowger regarding the<br />

importance of lobbying in eroding support for termination and<br />

helping to open the way for self-determination, but she has<br />

identified additional causes of the shift. Native American<br />

51 Philleo Nash to Fred Dutton and attachment, 13 November<br />

1961, "IN 11-21-61 - 11-20-62," box 379, WHCF, Subject File,<br />

JFKL; "Statement by the President," n.d., "IN 11-21-61 - 11-<br />

30-62," box 379, WHCF, Subject File, JFKL. Clarkin, Federal<br />

Indian Policy, 79-80; Josephy, Now that the Buffalo's Gone,<br />

224.<br />

52 Some studies that deal with self-determination include<br />

George Pierre Castile, To Show Heart: Native American Self-<br />

Determination and Federal Indian Policy, 1960-1975 (Tucson:<br />

University of Arizona Press, 1998); Thomas Clarkin, Federal<br />

Indian Policy in the Kennedy and Johnson Administrations,<br />

1961-1969 (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press,<br />

2001); Daniel M. Cobb, "Philosophy of an Indian War:<br />

Community Action in the Johnson Administration's War on<br />

Indian Poverty, 1964-1968," American Indian Culture and<br />

Research Journal 22:2 (1998): 71-102; Vine Deloria Jr., ed.,<br />

American Indian Policy in the Twentieth Century (Norman:<br />

University of Oklahoma Press, 1985); Deloria, Behind the<br />

Trail of Broken Treaties: An Indian Declaration of<br />

Independence (New York: Delacorte Press, 1974); Deloria and<br />

Lytle, Nations Within; William T. Hagan, "Tribalism<br />

Rejuvenated," Western Historical Quarterly 12 (January<br />

1981): 5-16; Josephy, Now That the Buffalo's Gone; Josephy,<br />

Nagel, and Johnson, Red Power; Joane Nagel, American Indian<br />

Ethnic Renewal: Red Power and the Resurgence of Identity and<br />

Culture (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997); Kenneth<br />

R. Philp, ed., Indian Self-Rule: First-Hand Accounts of<br />

Indian-White Relations from Roosevelt to Reagan (Logan, UT:<br />

Utah State University Press, 1995); Rebecca L. Robbins, "The<br />

Forgotten American: A Foundation for Contemporary American<br />

Indian Self-Determination," Wicazo Sa Review VI (Spring<br />

1990): 27-33.<br />

24

activist protests in the 1960s and 1970s--such as those<br />

carried out by the pan-Indian American Indian Movement (AIM)-<br />

-highlighted the failures of termination and the need for an<br />

alternative. The Civil Rights and Black Power Movements<br />

challenged existing assumptions about federal policies and<br />

racial/ethnic relations; changes in the assumptions in these<br />

areas opened up the possibility for change in other areas,<br />

including Indian policies. 53<br />

As a result, by the late 1960s (if not earlier), another<br />

shift had occurred. This time, termination was replaced with<br />

self-determination. In 1968, Democratic President Lyndon B.<br />

Johnson and and Republican presidential candidate Richard M.<br />

Nixon (who would be elected in November of that year) both<br />

issued statements rejecting termination and endorsing self-<br />

determination. 54 In a March 1968 Special Message to Congress<br />

on American Indians, Johnson said that "the special<br />

relationship between the Indian and his government must grow<br />

and flourish." In other words, the trust relationship would<br />

not be ended. In addition, the speech demanded more Native<br />

American input into the policymaking process, greater respect<br />

for Indian cultures, and increased aid to help Indians deal<br />

with such issues as poverty, poor health, and education. 55<br />

53 Nagel, American Indian Ethnic Renewal, 219-226.<br />

54 Castile, To Show Heart, 68-69, 73-74, 91.<br />

55 Public Papers of the President of the United States,<br />

1968, (Washington, D.C., 1969), 335-344.<br />

25

In a September 1968 campaign address, Nixon echoed many<br />

of these themes. He pledged that termination would "not be a<br />

policy objective" if he won the White House. Instead, his<br />

administration would recognize the fact that society could<br />

allow "many different cultures to flourish in harmony." He<br />

would continue, therefore, the "special relationship" between<br />

Native nations and the federal government. His presidency<br />

would respect the tribes' "right of self-determination" while<br />

working to assist Native nations with their social and<br />

economic difficulties. 56<br />

About two years after his election, in July 1970,<br />

President Nixon issued an even stronger statement of support<br />

for self-determination. 57 He declared termination to have<br />

been "wrong" and the maintenance of the trust relationship<br />

between tribes and the federal government to be a moral and<br />

legal obligation. Thus, tribes could not be terminated<br />

without their consent. 58 Along with a rejection of<br />

termination, Nixon's self-determination policy included<br />

respecting cultural pluralism, increasing federal assistance<br />

to American Indians on reservations and in cities, and--<br />

perhaps most importantly--developing legislation to permit<br />

56 "A Bright Future for the American Indian," 27 September<br />

1968, "Indian Affairs 91st, National Council on Indian<br />

Opportunity," Series VII, Box 30, Allott Collection, AUCL.<br />

57 Castile, To Show Heart, 91-95; Public Papers of the<br />

Presidents, 1970, 564-576.<br />

58 Public Papers of the Presidents, 1970, 565-566.<br />

26

Indian nations to administer programs currently run by the<br />

federal government. The president stressed that the transfer<br />

of control to tribes was voluntary and could only occur if a<br />

tribe desired it. 59<br />

This statement had special significance because it<br />

served as the basis for a series of bills--passed by<br />

Democratic Congresses and signed by Nixon--that wrote the<br />

ideas of self-determination into the lawbooks. The<br />

legislation included laws to recognize certain land rights of<br />

the Taos Pueblo and Alaska Natives, to provide greater<br />

federal aid to Indian education, to allow Native Americans<br />

greater say over education policy, and to reverse the<br />

termination of the Menominee people of Wisconsin. Perhaps<br />

most significant was the Indian Self-Determination and<br />

Education Act of 1975. Signed by Nixon's successor,<br />

Republican President Gerald R. Ford, the act provided for<br />

tribes to take over the administration of federal programs--<br />

as Nixon had called for in his 1970 message. Granted, some<br />

critics argued that federal authorities still exercised<br />

significant power over Indians and that the act contained so<br />

many regulations that tribes had a difficult time utilizing<br />

the act. It nevertheless seemed clear that self-<br />

determination had triumphed over termination. 60<br />

59 Public Papers, 1970, 567-569.<br />

60 Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act,<br />

S. 1017, 93d Cong., 4 January 1975, "Indian Rights," box 10,<br />

Richard D. Parsons Files, Gerald R. Ford Library, Ann Arbor,<br />

Michigan; Statement by the President, 4 January 1975, "Self-<br />

27

Self-Determination and the War on Poverty<br />

While the above discussion helps to explain why<br />

termination was abandoned, it does not fully explain why<br />

policymakers chose to accept self-determination, as opposed<br />

to some other policy. To be sure, the drafting of the<br />

Declaration of Indian Purpose and other actions demonstrated<br />

a Native American desire for self-determination. The wishes<br />

of a particular group, however, do not automatically become<br />

government policy.<br />

Certainly, many factors help explain policymakers'<br />

embrace of Indian self-determination. As several scholars<br />

have pointed out, though, a critical factor was the Johnson<br />

administration's War on Poverty. 61 The War on Poverty<br />

Determination Act," box 5, Bradley H. Patterson Files, GRFL;<br />

Memorandum for the President, 31 December 1974, "1/4/75 S.<br />

1017," box 21, White House Records Office: Legislative Case<br />

Files, GRFL. Castile, To Show Heart, 100-108, 148-152, 168-<br />

169; Prucha, Great Father, 1160-1161. American Indian Law<br />

Center, "NCAI/NTCA Team for the Review and Analysis of<br />

Regulations for the Indian Self-Determination and Education<br />

Assistance Act," n.d.; Charles Trimble to William Youpee, 12<br />

July 1975; both documents in fd. 12, box 12:12, series VII,<br />

NCAI Papers, NAA.<br />

On Nixon's Indian policies, see, in addition to Castile<br />

and Prucha, Jack D. Forbes, Native Americans and Nixon:<br />

Presidential Politics and Minority Self-Determination, 1969-<br />

1972 (Los Angeles: University of California American Indian<br />

Studies Center, 1981); Joan Hoff, Nixon Reconsidered (New<br />

York: Basic Books, 1994), 27-44; Dean J. Kotlowski, Nixon's<br />

Civil Rights: Politics, Principle, and Policy (Cambridge,<br />

Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2002), chapter 7.<br />

61 Castile, To Show Heart, ch. 3; Clarkin, "New Trail,"<br />

ch. 4; Cobb, "Philosophy," 71; Nagel, American Indian Ethnic<br />

Renewal, ch. 5; Philp, Indian Self-Rule, pt. 3; Riggs,<br />

"Indians."<br />

28

constituted an important part of President Johnson's<br />

expansive vision for America, the "Great Society." Johnson<br />

saw the Great Society as a place where the nation's wealth<br />

would serve "to enrich and elevate . . . national life, and<br />

to advance the quality of . . . American civilization. . . .<br />

The Great Society rests on abundance and liberty for all." 62<br />

To assure "abundance for all," Johnson advocated a series of<br />

federal initiatives designed to eradicate or at least<br />

significantly reduce poverty. 63<br />

62 U.S. President, Public Papers of the Presidents of the<br />

United States (Washington: Government Printing Office,<br />

1965), Lyndon B. Johnson, 1963-1964, pt. I, 704.<br />

63 Numerous books examine the Great Society and the War on<br />

Poverty. Just a few of these include John A. Andrew III,<br />

Lyndon Johnson and the Great Society (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee,<br />

1998); Irving Bernstein, Guns or Butter: The Presidency of<br />

Lyndon Johnson (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996);<br />

Robert Dallek, Flawed Giant: Lyndon Johnson and His Times,<br />

1961-1973 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998); Gareth<br />

Davies, From Opportunity to Entitlement: The Transformation<br />

of Great Society Liberalism (Lawrence: University PRess of<br />

Kansas, 1996); Michael B. Katz, The Undeserving Poor: From<br />

the War on Poverty to the War on Welfare (New York: Pantheon<br />

Books, 1989); Allen J. Matusow, The Unraveling of America: A<br />

History of Liberalism in the 1960s (New York: Harper and<br />

Row, 1984); James T. Patterson, America's Struggle Against<br />

Poverty in the Twentieth Century (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard<br />

University Press, 2000); Bruce J. Schulman, Lyndon B. Johnson<br />

and American Liberalism: A Brief Biography with Documents<br />

(Boston: Bedford, 1995); Irwin Unger, The Best of<br />

Intentions: The Triumphs and Failures of the Great Society<br />

Under Kennedy, Johnson, and Nixon (New York: Doubleday,<br />

1996). Lyndon Johnson offers his perspective in his memoirs,<br />

The Vantage Point: Perspectives on the Presidency, 1963-1969<br />

(New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1971). None of these<br />

books pays any significant attention to Native American<br />

issues.<br />

29

The origins of the War on Poverty were multifaceted. By<br />

the early 1960s, a growing number of Americans had become<br />

aware of and concerned that, despite significant economic<br />

growth since World War II, millions of Americans continued to<br />

live in poverty. In particular, author Michael Harrington's<br />

1962 book, The Other America, publicized the fact that many<br />

in the United States did not enjoy the fruits of prosperity.<br />

Growing public anxiety that welfare costs would rise and<br />

experts' concern that economic growth had slowed all helped<br />

prompt the John F. Kennedy administration to develop programs<br />

to assist the poor and the Johnson administration to expand<br />

upon those initial Kennedy efforts. In addition, to at least<br />

some observers, the prosperity of the post-World War II era<br />

made a fight against poverty seem affordable and the<br />

existence of poverty itself un-American. 64<br />

President Johnson's background inclined him to favor<br />

governmental programs to aid the poor. Johnson had been born<br />

and raised in a poor community in Texas, and during his year<br />

teaching school at Cotulla, Texas in 1928-1929, many of his<br />

Mexican-American students came to school hungry and<br />

illiterate. According to biographer Robert Dallek, the<br />

experience at Cotulla sensitized him to the plight of the<br />

impoverished and convinced him that people with power had a<br />

64 Matusow, Unraveling of America, chapter 4; Patterson,<br />

America's Struggle Against Poverty, 97-111. O'Connor,<br />

Poverty Knowledge, chapter 6; Michael Harrington, The Other<br />

America: Poverty in the United States (New York: Macmillan,<br />

1962; reprint, Baltimore, Maryland: Penguin, 1968).<br />

30

esponsibility to open up opportunities for the less-<br />

fortunate. As a Congressional aide, New Deal administrator,<br />

and Congressman during the 1930s, Johnson became deeply<br />

enamored of President Franklin D. Roosevelt and his "New<br />

Deal." Johnson believed that the New Deal showed that<br />

government policies could make life better for the poor and<br />

downtrodden. 65<br />

In other words, the emergence of a War on Poverty<br />

reflected modern liberalism's belief in the benefits of a<br />

strong, activist federal government. 66 However, the Johnson<br />

administration rejected redistributing income to the less-<br />

fortunate (commonly called "welfare") or having the<br />

government employ the poor. Instead, the War on Poverty<br />

would provide the poor with greater opportunity to improve<br />

their own economic condition. Economic development,<br />

education, and other government services would give the poor<br />

the chance to help themselves. Antipoverty policy sought to<br />

change the poor, not the American economy. (The economy<br />

itself would be managed to insure the long-term growth<br />

necessary to pay for antipoverty and other new programs<br />

without having to raise taxes or redistribute income.) 67<br />

65 Robert Dallek, Lone Star Rising: Lyndon Johnson and<br />

His Times, 1908-1960 (New York: Oxford University Press,<br />

1991), 77-80, 107.<br />

82.<br />

66 Schulman, Lyndon B. Johnson and American Liberalism, 1,<br />

67 Davies, From Opportunity to Entitlement, 30-34;<br />

Bernstein,<br />

31

This philosophy could be seen clearly in the Economic<br />

Opportunity Act, which the administration drafted in the<br />

first few months of 1964 and which Congress passed in August<br />

1964. The act created the Office of Economic Opportunity<br />

(OEO) to coordinate and oversee the assault on poverty. 68<br />

The new agency's mission was "enabling low-income families<br />

and low-income individuals . . . to attain the skills,<br />

knowledge, and motivations and secure the opportunities<br />

needed for them to become fully self-sufficient." 69 R.<br />

Sargent Shriver, the Director of OEO from 1964-1968, said<br />

that his programs constituted a "hand up, not a handout."<br />

The goal was to give "millions of poor people . . . a new<br />

Guns or Butter, 102; Patterson, America's Struggle Against<br />

Poverty, 130-133. Ira Katznelson, "Was the Great Society a<br />

Lost Opportunity?" in The Rise and Fall of the New Deal<br />

Order, 1930-1980, ed. Steve Fraser and Gary Gerstle<br />

(Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1989),<br />

198. On economic growth, see Robert M. Collins, "Growth<br />

Liberalism in the Sixties: Great Societies at Home and Grand<br />

Designs Abroad," in The Sixties: From Memory to History, ed.<br />

David Farber (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina<br />

Press, 1994), 11-44.<br />

68 Dallek, Flawed Giant, 107-111.<br />

69 Congress, Senate, S. 2642, 88th Cong., 2d sess.,<br />

Congressional Record (23 July 1964), vol. 110, pt. 13, 16787-<br />

16795; "Quick Facts About the War on Poverty," n.d., fd. 12,<br />

box 70, J. Edgar Chenoweth Papers, Archives, University of<br />

Colorado Libraries, Boulder, Colorado (AUCL); Committee on<br />

Education and Labor, "Economic Opportunity Act of 1964, As<br />

Passed by the House and Senate," n.d., fd. 12, box 70,<br />

Chenoweth Papers, AUCL.<br />

32

chance to participate in the economic growth of our<br />

country." 70<br />

How would the Economic Opportunity Act open the doors of<br />

opportunity to the poor? It provided the OEO and other<br />

federal agencies with a number of mechanisms. The Job Corps<br />

provided young people with remedial education and vocational<br />

training; Adult Basic Education programs offered adult<br />

literacy instruction; the Neighborhood Youth Corps provided<br />

young adults with vocational training or employment designed<br />

to encourage them to stay in or return to school; other<br />

programs provided loans, grants, and technical assistance to<br />

farm families, migrants, and small business persons; the<br />

VISTA program served as a antipoverty, domestic version of<br />

the Peace Corps.<br />

Finally, Community Action Programs (CAPs) made available<br />

federal funds and technical assistance to local community-run<br />

efforts to battle poverty. 71 The government officials and<br />

social scientists who developed the idea for CAPs argued that<br />

the existing federal, state, and local welfare bureaucracies<br />

and officials had failed to effectively address the problem<br />

of poverty. Therefore, community action would bypass the<br />

70 Shriver's "hand up" quote taken from Isserman and<br />

Kazin, America Divided, 110; Shriver to James Patton, 11<br />

August 1964, fd. 5: "Sargent Shriver 1961-1966," box 7,<br />

James G. Patton Papers, AUCL.<br />

71 Congress, Senate, S. 2642, 88th Cong., 2d sess.,<br />

Congressional Record (23 July 1964), vol. 110, pt. 13, 16787-<br />

16795. Andrew, Lyndon Johnson, 70.<br />

33

established bureaucrats and politicians and allow the poor<br />

themselves meaningful input into the development and<br />

implementation of anti-poverty initiatives. Promoting<br />

"maximum feasible participation" of the poor was consistent<br />

with the opportunity model because it would (presumably)<br />

change the poor by discouraging dependency and fostering<br />

empowerment. 72<br />

The Community Action model and the War on Poverty have<br />

been and remain controversial. Nevertheless, antipoverty<br />

policies dramatically impacted Native Americans. The War on<br />

Poverty's emphasis on opportunity and self-help, and the<br />

CAPs' emphasis on local involvement, meant that the poor<br />

would be expected to act on their own behalf. Hence, the War<br />

on Poverty gave American Indian nations the opportunity to<br />

develop and administer their own policies and programs.<br />

At least, that was the possibility in early-to-mid 1964<br />

if the Economic Opportunity Act and the OEO took Indians and<br />

their situation into account. Native American inclusion in<br />

the War on Poverty did seem likely for three reasons. First,<br />

72 Katz, Undeserving Poor, 97-101, 112-123; Alice<br />

O'Connor, Poverty Knowledge: Social Science, Social Policy,<br />

and the Poor in Twentieth-Century U.S. History (Princeton,<br />

New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2001), 124-136, 168-<br />

173; James T. Patterson, America's Struggle Against Poverty<br />

in the Twentieth Century (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard<br />

University Press, 2000), 133-136, 144-149. For an excellent<br />

case study of a Native American-oriented CAP, see Daniel M.<br />

Cobb, "'Us Indians Understand the Basics': Oklahoma Indians<br />

and the Politics of Community Action, 1964-1970," Western<br />

Historical Quarterly 33:1 (Spring 2002): 41-66.<br />

34

the economic and social conditions in Indian Country made<br />

Indians a natural target for an antipoverty campaign. 73<br />

Native American communities commonly experienced double-digit<br />

unemployment rates: 14 percent for the Eastern Cherokees of<br />

North Carolina and 43 percent for the Rosebud Sioux in South<br />

Dakota in 1963, for example. 74 Disease and ill-health were<br />

ubiquitous as well. In 1963, the average age of death was<br />

forty-two for Indians and thirty for Alaska Natives, as<br />

compared to sixty-two for the general population. These<br />

figures were a consequence of an Indian infant mortality rate<br />

that was about twice as great as that of non-Indians. In<br />

fact, 21 percent of all Indian deaths in a given year were<br />

infant deaths; for the general population, the figure was 6<br />

percent. 75 Such figures were disturbing but not entirely<br />

surprising given that 75 percent of all Indians lived in sub-<br />

73 William T. Hagan, "Tribalism Rejuvenated: The Native<br />

American Since the Era of Termination," Western Historical<br />

Quarterly XII (January 1981): 5-16.<br />

74 Unemployment figures are for Indians aged eighteen to<br />

fifty-five. Congress, House, Committee on Interior and<br />

Insular Affairs, Indian Unemployment Survey, pt. 1,<br />

Questionnaire Returns, 88th Cong., 1st sess., 1963, 3, 34,<br />

567.<br />

75 "Report of Field Visit, Follow Up of White House<br />

Conference on Children and Youth," 17-20 May 1961, 6-7,<br />

"071.33-White House Conference," Albuquerque Area, 8NN-075-<br />

88-077, Box 1/1, BIA, RG 75, NARMR. Congress, House,<br />

Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs, Subcommittee on<br />

Indian Affairs, A Review of the Indian Health Program:<br />

Hearings Before the Subcommittee on Indian Affairs, 88th<br />

Cong., 1st sess., 23 May 1963, 6, 24-25.<br />

35

standard houses. 76 Native Americans age twenty-five and<br />

above only had about half as much education as non-Indians. 77<br />

Second, Native Americans served on the Johnson<br />

administration's poverty task force--which met in late 1963<br />

and early 1964 to develop antipoverty legislation--included<br />

Native Americans like federal official Forrest Gerard<br />

(Blackfeet) and Pueblo leader James Hena (Tesuque Pueblo).<br />

Secretary of the Interior Stewart L. Udall, who had developed<br />

a reputation as being sympathetic to Indian interests while<br />

serving as a Congressman from Arizona, also regularly showed<br />

up for the poverty task force meetings. 78<br />

Third, to help insure that members of Congress and<br />

federal bureaucrats understood Native Americans' desire to be<br />

included in the poverty program, the Council on Indian<br />

Affairs conducted an "American Indian Capital Conference on<br />

Poverty" on 9-12 May 1964 in Washington, D.C. The group was<br />

a "coordinating council" made up of several organizations<br />

interested in Indian affairs, including the NCAI and several<br />

church groups. 79 The conference opened with an evening<br />

76 Stan Steiner, "The American Indian Ghettos in the<br />

Desert," The Nation, 22 June 1964, 625.<br />

77 "Report to the Secretary of the Interior by the Task<br />

Force on Indian Affairs," 10 July 1961, 22-23.<br />

78 Nakai to Lester, 29 December 1964, "060 Tesuque-Gen.<br />

Supt. File," box 13, 8NS-075-95-022, Albuquerque Area, BIA,<br />

RG 75, NARMR; Gerard, interview. Bernstein, Guns or Butter,<br />

101, refers to Udall's regular attendance.<br />

79 "Hubert Humphrey to be Keynote Speaker at American<br />

Indian Conference on Poverty," 9-12 May 1964, "IN Indian<br />

36

address by Hubert H. Humphrey, a Democratic Senator (later<br />

Vice President) from Minnesota. Humphrey assured his<br />

audience of Natives and non-Natives that Indians would be<br />

"prime targets" in the administration's program because<br />

poverty disproportionately affected Native Americans and<br />

because of the federal trust responsibility. Robert Burnette<br />

(Rosebud Sioux), Executive Director of the NCAI from 1961-<br />

1964, spoke that same night on Indian poverty. 80<br />

The next day, Sunday, May 10, delegates attended a<br />

church service dedicated to American Indians at Washington<br />

Cathedral and led by Archdeacon Vine V. Deloria Sr. (Standing<br />

Rock Sioux). That afternoon, during another service at the<br />

Cathedral, a pan-tribal processional of Native Americans<br />

dressed in traditional fashion and carrying symbols of their<br />

respective nations took place. Interior Secretary Udall, in<br />

his statement to those in attendance, gave assurances that<br />

the administration would address Native Americans' economic<br />

problems.<br />

Affairs 11/23/64-2/29/64," box 1, WHCF, SF, IN, LBJL;<br />

"American Indian Capital Conference on Poverty: Findings,"<br />

9-12 May 1964, "American Indian Capital Conference on<br />

Poverty," box 32, Peterson Papers; "NCAI Eminent Objectives:<br />

Target--A New Dimension in Indian Affairs," The National<br />

Congress of American Indians (pamphlet), n.d., "NCAI<br />

Portland, Oregon, 10/2-6/67," box 1522, RG 75, BIA, NAPNWR;<br />

Clarkin, Federal Indian Policy, 113-117.<br />

80 Humphrey's speech is reprinted in Sheldon E. Engelmayer<br />

and Robert J. Wagman, Hubert Humphrey: The Man and His Dream<br />

(New York: Methuen, 1978), 272-277; Burnette, Tortured<br />

Americans, 88.<br />

37

On May 11, the Council on Indian Affairs put on a<br />

reception at the Capitol building. This allowed delegates to<br />

meet one-on-one with lawmakers and their staffers and to<br />

acquaint them with the deleterious social and economic<br />

conditions that were all-too-common in Indian Country. 81<br />

At least some of the recommendations made to the<br />

politicians and their aides at the reception came from the<br />

findings and recommendations of a series of Council on Indian<br />

Affairs working groups. The working groups met during the<br />

conference to discuss a variety of areas, including health,<br />

housing, education, and employment. Like the Declaration of<br />

Indian Purpose, the groups advocated increased federal<br />

assistance in all of those areas. The participants also<br />

echoed the Declaration's call for self-determination in their<br />

recommendations for self-administration, a rejection of<br />

paternalism, and preserving distinctive Native societies and<br />

cultures. The education work group, for example, urged that<br />

"all education programs be planned by the Indian group<br />

involved" and that they incorporate "traditional tribal<br />

values." The health group wanted health care personnel "who<br />

understand the American Indian." The housing group called on<br />

the federal government to defer to the wishes of tribal<br />

housing authorities in terms of project sites. Both the<br />

housing and employment groups opposed tribes having to go<br />

81 Clarkin, Federal Indian Policy, 114; "Hubert Humphrey<br />

to be Keynote Speaker," 9-12 May 1964.<br />

38

through states to access funds and programs; instead, tribes<br />

should be able to work directly with the federal<br />

government. 82<br />

The emphasis on self-determination and connection with<br />

the Declaration also could be seen in a statement made by<br />