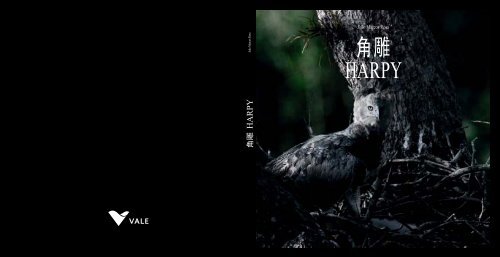

角雕

角雕

角雕

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>角雕</strong><br />

<strong>角雕</strong>

HARPY<br />

NITR<br />

巴西 2010

<strong>角雕</strong>原产于墨西哥南部至阿根廷北部的热带雨林 。如今这<br />

种鸟类依然栖息在卡拉加斯国家森林的山谷中,与命运抗衡<br />

7

HARPY<br />

17

Message from the CEO<br />

Commitment to sustainability is a key focus of Vale. By integrating our operational activities with<br />

conservation and restoration of the ecosystems of the areas where we are settled into, we became<br />

one of the Brazilian companies which contribute the most to the preservation of Brazil’s biodiversity.<br />

Therefore, we are very proud of being part of such an important and noble project: the preservation of<br />

the harpy eagle, one of the largest and most beautiful birds of prey in the world.<br />

In partnership with Chico Mendes Institute for Biodiversity Conservation (ICMBio) and National Institute<br />

for Amazonian Research (INPA) , during eight months Vale monitored two harpy nests found in the<br />

Carajás National Forest . As a result, this book is coming out with pictures not published before and with<br />

information on a species which is very important to the Brazilian biodiversity.<br />

I hope the images which beautify the pages in this book help stimulate environmental awareness. I also<br />

expect it to be evidence of our ability and obligation to preserve and protect our environment.<br />

Roger Agnelli<br />

President & CEO<br />

19

22<br />

R788h Rosa, João Marcos<br />

Harpia / João Marcos Rosa (fotos) . Textos de Frederico Drumond,<br />

Tânia Sanaiotti, Roberto Azeredo. Belo Horizonte: Nitro, 2010.<br />

144 p., principalmente fotografias (coloridas).<br />

Texto em português, com tradução paralela em inglês.<br />

ISBN: 978-85-62658-01-3<br />

1. Harpia – Fauna silvestre. 2. Biodiversidade – Pesquisa –<br />

Conservação. I. Título. II. Drumond, Frederico. III. Sanaiotti,<br />

Tânia. IV. Azeredo, Roberto.<br />

CDD: 598.2<br />

CDU: 598.2<br />

Informação bibliográfica deste livro, conforme a NBR 6023:2002 da<br />

Associação Brasileira de Normas Técnicas (ABNT):<br />

ROSA, João Marcos. Harpia. Belo Horizonte: Nitro, 2010. 144 p. ISBN<br />

978-85-62658-01-3.

24<br />

58<br />

90<br />

ABOUT THe AUTHOR<br />

138<br />

ACkNOwleDgeMeNTS<br />

144<br />

23

24<br />

卡拉加斯国家森林中的<strong>角雕</strong><br />

Frederico Drumond Martins<br />

Chico Mendes生物多样性保护研究所环境分析师<br />

卡拉加斯国家森林负责人

The Harpy Eagle in Carajás National Forest<br />

Frederico Drumond Martins<br />

Environmental Analyst for ICMBio - (Chico Mendes Institute for Biodiversity Conversation)<br />

Head of the Carajás National Forest<br />

It was with great honor that I accepted the invitation to participate in this book of wonderful pictures, which<br />

crowns the work on the Harpy Eagle, one of the species I admire the most. First of all, I would like to extend<br />

an invitation to the reader: Come visit the Carajás National Forest. It is a place of indescribable beauty,<br />

immense diversity of plants and animals, and it is the landscape in most of the pictures in this book.<br />

The Carajás National Forest is an area of 400 thousand hectares ( 988.4 acres ) of protected land<br />

and significant sample of Amazonian biodiversity. The forest borders four other preserved areas as well<br />

as an indigenous reserve. This mosaic of protected areas, within a one-million-hectare area of continuous<br />

rainforest, has become the biggest remaining preserved ecosystem in southern and southeastern Pará.<br />

For the great anthropogenic pressure in this part of Brazil, Carajás National Forest became shelter for<br />

several species of the rare and endangered fauna and flora.<br />

The Canopy Queen<br />

Among the more than 600 bird species already catalogued in Carajás, one can find the largest Brazilian<br />

eagle, the Harpy Eagle. The first accounts of seeing this species have been reported in the region since<br />

the first time there was a published list of birds. Two nests have recently been discovered – both with<br />

actively reproductive couples – indicating environmental protection. A preserved area is the primary<br />

requirement for the couple’s choice of a growing tree that will provide them with a good view of the<br />

whole forest. A good view will allow them to collect sticks for nest maintenance and mainly hunt in a defined<br />

territory, ensuring the survival of future generations.<br />

Studies of bioindicators, such as the Harpy Eagle, are fundamental tools for the management of a<br />

conservation unit. They help interpret the environment and direct priority actions for achieving the ultimate<br />

goal of any protected area: The conservation of their ecosystems. The finding and monitoring of these two<br />

nests raise some questions, such as the need to restrict the use of nesting areas, ranging from protection<br />

of the trees used for its construction to protection of the territory of the Harpy couples.<br />

25

Awareness and union<br />

The beauty and grandeur of the Harpy Eagle promotes the interest in knowing and preserving our<br />

biodiversity, thus making environmental education such an important tool to raise awareness of the<br />

surrounding forests dwellers. The accounts and information acquired from monitoring the nests have<br />

been shown in science fairs, academic lectures, and social works. These actions have raised awareness<br />

among the forest’s neighbors of the importance of environmental protection.<br />

The discovery of the first nest incited a strong partnership for the protection of these species.<br />

The Chico Mendes Institute for Biodiversity Conservation (ICMBio) , paved the way to the Harpy Eagle<br />

Protection Program by supporting the Carajás National Forest in becoming an important area in the<br />

studies of the Harpy. The mining company Vale, an environmentally responsible company, has embraced<br />

the program providing necessary resources for sharing research and visual records. The National<br />

Institute for Amazonian Research (INPA), a specialized institution in the region, coordinates the activities<br />

in Carajás, and with all its experience in this forest, is planting a seed that is already beginning to bear<br />

fruits.<br />

The second nest found further strengthened this partnership, encouraging each institution to reflect<br />

on their role in controlling human predatory activities, particularly deforestation and replacement of<br />

forests in landscapes that do not allow for the preservation of biodiversity. With the group work among<br />

the institutions involved, this project will open up, with realism and maturity, new ways toward the<br />

protection of the Harpy Eagle in Brazil.<br />

27

Despite its large size that can reach 2.2 m ( 7.2 feet ) the harpy<br />

shows grace and skill when landing in the nest. Carajás, Pará<br />

29

30<br />

In the small clearing amid the forest, the housing along the Águas<br />

Claras River serves as one of the main bases for the researchers.<br />

They fully utilize the structure, which was initially built to house<br />

mineral exploration teams. Carajás, Pará

As seen from a helicopter, the Carajás National Forest seems to<br />

be an impenetrable surface<br />

37

Detail of a nestling’s feather collected from under the tree where<br />

the Águas Claras nest is located. Carajás, Pará<br />

39

The prey taken by the male will feed the female and the<br />

one-month-old nestling. Until the nestling reaches two<br />

months of age, the mother remains close to the nest and<br />

only the male hunts. Carajás, Pará<br />

41

42<br />

The female harpy weighs 10 kg (22 lbs.) and is about one-third<br />

larger than the male. weighing no more than 6 kg ( 13.2 lbs. ),<br />

the adult male is more agile and a better hunter

44<br />

Students at the Jorge Amado School in the vicinity of the Carajás<br />

National Forest participate in a class about the harpy eagle.<br />

Researchers use environmental education as a tool to have<br />

the community sympathize with the project and become partners<br />

in it. Carajás, Pará

After being caught in a farmer’s house by the ICMBio team, this<br />

animal is going through a rehabilitation process at the Carajás<br />

Zoobotanica Foundation. It is being prepared to carry a radio<br />

transmitter once it returns to the wild<br />

45

The expansion of farming is one of the biggest threats to the<br />

species. In the picture, one can see a pasture land moving towards<br />

the Parauapebas River, a natural border of the Carajás National<br />

Forest<br />

47

52<br />

In this rarely documented moment, the female returns to its nest<br />

carrying a primate in its claws. when the nestling is two months<br />

old, it is more frequently fed; therefore, it quickly gains weight.<br />

Carajás, Pará

The Majestic Harpy in Brazil<br />

Tânia M. Sanaiotti<br />

Researcher, National Institute of Amazonian Research(INPA)<br />

Coordinator of the Harpy Conservation Program<br />

The study about the harpy is more than anything an exciting lesson of patience. Owner of discrete<br />

habits and often silent, this eagle is considered the strongest in the world because its claws can carry<br />

prey which weighs as much as it does. Males weigh about 6kg (13.2 lbs.) and female about 10kg (22<br />

lbs.). Unlike other birds, the harpy vocalizes only during mating periods and when feeding its nestlings.<br />

Therefore, it is not so simple of a task to dentify its presence in the forest; thus almost always requiring<br />

from the researcher few techniques used by its own object of study. Breath to climb trees over 40 meters<br />

tall (131.2 feet ), physical strength ,and a refined sense of observation are some of the requirements to<br />

spy on the harpy while it is majestically housed in the canopy, as well as to try and decipher some of<br />

the mysteries of the bird whose wingspan exceeds two meters (6.5 feet).<br />

It is from these tall trees with privileged views of the forest that the far-sighted and highly developed<br />

hearing harpy, after detecting its prey, takes flight in high speed to attack with perspicacity. The ability<br />

to rotate its head 180 degrees also contributes to the success of the hunt. Its target is primarily arboreal<br />

herbivorous animals, such as sloths and monkeys. Other vertebrates which also inhabit the canopy,<br />

such as porcupines, toucans and macaws, complement this predator’s diet. In Brazil, the harpy lives in<br />

the Amazon and Atlantic rainforest and in the riparian forests of the Cerrado. In the riparian forests, as<br />

well as in Pantanal, it flies over open green areas between mountains and rivers, feeding on armadillo,<br />

deer, and coati.<br />

59

A Conservation Program<br />

The first description of the harpy in the books was made by European naturalists in the eighteenth<br />

century, when the species lived in most of the great forests from southern Mexico to northern Argentina.<br />

Nearly three centuries of overexploitation of natural resources are between these publications and the<br />

first Brazilian research and conservation project about the species. The discovery of a nest near Manaus<br />

in 1999 prompted researchers from the National Institute of Amazonian Research (INPA) to turn their<br />

attention to the species. After that, new nests were recorded, mapped and monitored by biologists and<br />

climbers who form a multidisciplinary team in the “Programa de Conservação do Gavião Real”(Harpy<br />

Eagle Conservation Program).<br />

The project was named after one of the many names by which the eagle is known in the country.<br />

The nickname “gavião-real” (royal eagle) is due to the impressive size and the feather crown on its<br />

head. The scientific name Harpy harpyja refers to a Greek mythology being which is half eagle and<br />

half woman. However, among the people of the forest there are many nicknames:“Uiraçu-falso” (fake<br />

uiraçu), “gavião-preguiça” (sloth-hawk), and “ gavião-neném” (baby-hawk).<br />

Over a decade, the work of the program was made possible only with the collaboration of other<br />

good local observers. For the research of nests, INPA relies on the cooperation of various sources,<br />

mostly proprietors or neighbors of lands where harpies were seen, and the precious help of the staff of<br />

protected areas. Because of that, the strategy used in the Harpy Eagle Conservation Program is linked<br />

mainly to the involvement of traditional communities of the surroundings of the protected areas, and to<br />

the consolidation of partnerships with federal, state, and private institutions. These strategies facilitate<br />

the disclosure of the importance of environmental preservation and of the successful results already<br />

achieved.<br />

This support network enhances the activities of the biologists of the project in different fronts. It<br />

identifies the processes and variables that influence the distribution and abundance of the harpy in<br />

the Brazilian forests, and studies the degree of loyalty from species to nesting areas. Quantitative and<br />

qualitative analyses of collected preys are run in order to identify the animal’s diet.<br />

With the use of technology, the monitoring of young eagles by telemetry is another field of research.<br />

The tool helps determine the population dispersion, while analysis of population density contributes to a<br />

more accurate definition of the status of the species’ preservation. A group of researchers in a laboratory<br />

run genetic studies and collaborates with captive breeding programs of the species. Rehabilitation and<br />

reintroduction might also contribute, in some cases, to the expansion of protected areas, and to add<br />

value to existing forests in the surrounding areas.<br />

61

Threat<br />

The presence of this bird of prey collaborates with the natural equilibrium in the ecosystems where<br />

it lives. The harpy can control the number of individuals of prey species, hence the importance of its<br />

preservation, as it is considered an “umbrella” in other species protection. Located at the top of the food<br />

chain, the harpy has no predators other than men, which, historically, have been devastating their habitat.<br />

The indiscriminate hunting and the use of harpy in traditional rites of some societies also contributed<br />

to its endangerment according to the list of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). It<br />

is important to note that the conservation status of the harpy eagle in Brazil is controversial. The large<br />

geographical extent of our country provides contrasts. For instance, the existence of widely preserved<br />

forest areas in regions such as the Legal Amazon, where the population of the eagle still seems to be<br />

preserved, contrasts with the great anthropogenic pressure in areas such as the states of Espírito Santo,<br />

São Paulo and Rio Grande do Sul. These states, which are part of the Atlantic rainforest biome, officially<br />

list the harpy as endangered.<br />

There is still time to reverse the situation. For this, political, social, and economic measures based<br />

on data collected by researchers who seek answers to environmental conservation are imperative. The<br />

charisma of species such as the harpy eagle, considered by some indigenous people as the queen of<br />

the forest, can form a large network for the maintenance of biodiversity and of men, who are, like any<br />

other species, so dependent on this planet.<br />

63

64<br />

In flooded forests, the “igarapés” form the routes that lead to<br />

the nests . In this environment, canoes are the only possible<br />

means of transportation. Manacapuru, Amazonas

66<br />

Biologist Benjamim da Luz analyzes the first harpy nest found<br />

in Bahia. Private Nature Reserve estação Veracel, Porto Seguro

Part of forest land burned in Parintins, Amazonas. Collecting<br />

data on the harpy’s habitat before the deforestation is one of the<br />

major challenges of researchers<br />

69

70<br />

Under the gaze of an interested riverside child, Tania Sanaiotti<br />

observes a nest in Parintins, Amazonas

74<br />

Jaílson Santos from ICMBio and José eduardo Mantovani from<br />

INPe track two harpies that carry radio transmitters in the Pau<br />

Brazil National Park. eunápolis, Bahia

Researcher Alexander Blanco manipulating a nestling which,<br />

while on the ground, will be measured, have samples collected,<br />

and have a radio transmitter implanted . Imataca Forest Reserve,<br />

Venezuela<br />

75

Although still having juvenile plumage, this nestling already<br />

shows beneath its wings the standard gray and white colors<br />

that identify this species. Parintins, Amazonas<br />

81

Observed by a nestling, the researcher looks for anchorage in<br />

order to safely reach the nest. Parintins, Amazonas<br />

87

In a school by Cururu lake, biologist Tania Sanaiotti holds one<br />

more lecture on the harpy eagle. Involving locals in the conservation<br />

of the species is crucial to the project’s success. Manacapuru, Amazonas<br />

89

Men and Harpies<br />

Roberto Azeredo<br />

Researcher and President of CRAX Brazil-Society for Research on Reputation and Management of Wildlife<br />

It has been thirty years since I first saw a harpy eagle in nature. I was wandering around Vila Rica,<br />

northeast of Mato Grosso, in one of the most preserved places that I have ever been. Landing on a<br />

branch on the dry bank of the river, the harpy eagle suspiciously gazed at me. Petrified and astonished,<br />

I watched the grandeur and beauty of this bird. This image is still clearly engraved in my memory.<br />

Years later, we have already been working with extremely positive results in breeding and reintroducing<br />

into nature the red-billed curassow (Crax blumenbachii), the black-fronted piping-guan (Pipile jacutinga),<br />

and the solitary tinamou (Tinamus solitarius) in remnant areas of the Atlantic rainforest. Due to the<br />

success achieved by working with these endangered species, we set off for a new challenge: Develop<br />

a similar program for the Harpya harpyja.<br />

The first formation of a harpy couple in CRAX happened in 1998. To our delight, in April 1999, our<br />

research succeeded in getting a nestling to be hatched and raised in captivity by its parents. The work<br />

with reproduction succeeded and eleven more animals of this species were conceived in our research<br />

center in Contagem, Minas Gerais. These numbers encouraged us to move to the following phase. In<br />

mid-2006, in order to come up with an interdisciplinary project aiming at the reintroduction of harpies into<br />

nature, we gathered a group of leading researchers involved with the species. The plan was approved<br />

by IBAMA, but we didn’t get financial aid for its implementation.<br />

Nowadays, I am sure Brazil is ready to channel empirical studies to a practical consequence: The<br />

reintroduction of this animal into the wild. We can achieve the same success that the Spaniards achieved<br />

with their Spanish imperial eagle (Aquila adalberti), and the United States with the iconic bald eagle<br />

(Haliaeetus leucocephalus). There is no point in continuing the research if the ultimate goal is not the<br />

closing of a cycle: The return of the species to the forests. If we follow the pioneering example of working<br />

with the red-billed curassow, which starting from eight animals three hundred were reintroduced into<br />

nature, in a few decades we will be able to see the harpy flying in the remnants of Atlantic rainforest.<br />

91

Recently, a great achievement in Brazil broke several taboos and reheated the debate on the subject.<br />

For the first time an eagle after being in captivity for more than ten years was released and reintroduced<br />

to its habitat. It was a female, captured nearly 13 years ago on a farm, in Bahia. Researches, rehabilitation,<br />

and follow-up assessments considered the animal capable of returning to nature. The eagle then lifted its<br />

first flight in August this year, on the private nature reserve (PRNP) “Estação Veracel” ,in Porto Seguro.<br />

Constant monitoring of this animal free in the forest gives us important insights into believing that its<br />

adaption and equilibrium with nature is possible, despite the long time away from its environment.<br />

I dream of the day when people will know more about the harpy and will get involved in preservation<br />

projects, not only for this eagle but for the entire ecosystem involved. Disclosing the beauty and importance<br />

of the harpy as a flagship species for environmental protection is crucial to ecological training, as well as<br />

to encouraging the search for new projects. I believe this bird of prey, because of its mythical legends<br />

in Central and South America, can become an icon of environmental programs, as it did in Ecuador and<br />

Panama. In both countries, the harpy is representative of biological diversity.<br />

Keeping an eye on the future, the work developed in the Carajás National Forest is an example of local<br />

community participation in the fight for preservation. This kind of action should be spread throughout<br />

the country, and policies must encourage and support the development of projects about endangered<br />

species. Initiatives of this magnitude do not have immediate results, but in the long run can contribute to<br />

the improvement of the quality of life on the planet. I believe this beautiful publication is one more step<br />

on this long journey.<br />

93

Falconry techniques are used to help manipulate animals in captivity,<br />

preparing them for artificial insemination procedures. CRAX’s<br />

goal is to reintroduce into nature the nestlings that are born.<br />

Contagem, Minas gerais<br />

95

98<br />

A never- seen - before image: the hatching of a harpy’s egg.<br />

CRAX, Contagem, Minas Gerais

100

101

102<br />

In order to relate differences and consistencies between the harpy<br />

populations in Amazon and in Atlantic rainforest, feather<br />

fragments are collected for genetic studies of the species. Museum<br />

of Natural Science, PUC Minas

103

104

The black squirrel monkey (Saimiri vanzolinii) and other<br />

arboreal mammals are also part of the harpy’s diet<br />

105

106

Bones of eaten preys are collected by researchers in the nests<br />

and surrounding the respective trees. The analysis of these samples<br />

is essential to identifying the harpy’s prey<br />

107

108

Still fragile and clumsy , the nestling shows its claws on its first<br />

day of life. CRAX, Contagem, Minas Gerais<br />

109

110

During the warmest moments of the day, the mother’s shadow<br />

is the only protection for the nestling. Carajás, Pará<br />

111

112<br />

The name Harpia harpyja refers to greek mythology. It<br />

designates a hybrid being: half woman, half eagle

113

114<br />

The various roads in the Carajás National Forest make the<br />

work more dynamic and productive, as opposed to what<br />

occurs in other research areas, where access to nests is only<br />

through trails or rivers

115

116<br />

with its hallux up to 7cm long (2.75 in.) , a harpy’s claw is<br />

bigger than that of a brown bear

This harpy , equipped with a transmitter, was reintroduced into<br />

nature after 13 years in captivity. eunápolis, Bahia<br />

117

118

119

120

In order to increase nest observation time, the researchers’<br />

routine begins early<br />

121

122<br />

Benefitting from its wide wingspan, the harpy protrudes from<br />

the top of a chestnut tree. Carajás, Pará

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

The nestling’s first flight is normally within the branches<br />

of the tree where its nest is located . Because they are lighter<br />

than the females, males start these attempts when they are 5<br />

months old, while females may take up to 7 months to leave<br />

the nest. Carajás, Pará<br />

133

134

135

136<br />

Learning to fly and hunt , the nestling exercises its claws<br />

carrying a clump of roots. Carajás, Pará

137

138

About the author<br />

In the February 2006, an essay on harpies published in National Geographic Brazil was the first<br />

publication about João Marcos Rosa’s valuable work on the largest bird of prey in the Americas. It now<br />

culminates in the publication of this groundbreaking book.<br />

The idea of documenting this extraordinary species, the Harpy harpyja, arose in 2004. When João<br />

was introduced to the harpy in Parintins (AM), the sound of chainsaws next to the eagle’s nest warned<br />

him: It was necessary to show that the bird, despite being apparently imposing, was valuable and<br />

exposed to the folly of its habitat deforestation.<br />

Early in his career, João served as assistant to Araquém Alcântara who has been for over 30 years<br />

an important figure in environmental photography in Brazil. João inherited from his knowledge in using<br />

natural light and certain poetic vein to compose pictures of wildlife. Nevertheless, in an underlying<br />

aspect, João went further: the diversity of animals’ behavior. This book attests to that.<br />

He traveled dozens of times to the Pará, Mato Grosso do Sul, Amazonas, Bahia and Venezuela - he<br />

spent thousands of hours either on a plane, boat, canoe, ferry, helicopter, walking, or in a car. As done<br />

for the National Geographic magazine, which preaches the total immersion of the photographer into the<br />

environment of the species - whether it’s a polar bear or an ant - João had to literally get off the ground.<br />

He learned to climb trees to reach nests. He faced an old fear of heights (he says it still exists) to see<br />

the harpy’s life from its angle: the top.<br />

In the Amazon and in the Atlantic rainforest, he captured unseen images of the harpies hunting,<br />

showing their wingspan in full flights, protecting their nests, and feeding their nestlings. During his<br />

journey to Parintins, he had a remarkable moment when, amazed at the beauty of the enormous animal<br />

crossing the sky, he couldn’t trigger his camera. With trembling hands, a few seconds later he could<br />

finally capture the image of the bird landing on the tree with a prey in its claws. Seeking a balance<br />

between wildlife records and science, his work progressed toward recording the daily life of researchers<br />

in the field, in laboratories, and the efforts of captive breeding.<br />

The most special moments of his long journey have certainly happened in Carajás National Forest<br />

(PA) in 2009. From a 35m tall platform ( 14.8 feet) built on a chestnut tree, he could follow the copulation<br />

of a couple of harpies, the hatching of an egg, and the birth and development of the nestling. The history<br />

of this bird of Carajás is symbolic. Fortunately, as João Marcos Rosa’s pictures show us, life is renewed<br />

for the harpies in Brazil. This book is an encouragement for the preservation of the species.<br />

Ronaldo Ribeiro<br />

Senior Editor - National Geographic Brazil<br />

139

140

From a 131.2 feet high platform, photographer João Marcos<br />

Rosa records life in a nest. Carajás, Pará. (Photo: Marcus Canuto /<br />

SOS Falconiformes)<br />

141

142

143

144<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

巴伊亚(Bahia):Carlos André、Catão、Davi、Delgado、<br />

Denise、 Eduarda、Fernando Brutto、Gil、Jaílson、<br />

Lígia、Manoel、 Olândia、Rafael、Raquel、Sandro、<br />

Sara、Sérgio e Valdemir<br />

波尼多(Bonito):Adílio、 Alexandre、Faete e Nelson<br />

Chemin<br />

卡拉加斯(Carajás): Aline、Borges、Deuzimar、Duart、<br />

Edna、Ezaú、Fernanda、Figueiredo、Fred Drumond、<br />

Jardel、 Joãozinho、Josiel、Mesquita、Nívea、Nonato、<br />

Roberto、Renilson e Seu Manoel<br />

马纳卡普鲁(Manacapuru):Dunga、Peruano e comunidades<br />

do Lago do Cururu<br />

马瑙斯(Manaus):Adnes、Áureo、Benjamin、Capitão<br />

Ferreira、Dica、Helena、Ivan、Júlio、Marcelo、Olivier<br />

e Tânia<br />

米纳斯吉纳斯( Minas Gerais): Bete 、Bruno、Cadu、<br />

Canuto、Carol、Daniel、Eduardo、Geer<br />

Scheres、Gislene、Gustavo、James Simpson、Leo、<br />

Marcus、Nidin、Roberto Azeredo e Jorge。<br />

巴西国家地理杂志( National Geographic Brasil):Cris<br />

Catussatto、Cris Veit、Karen Pegorari、Matthew Shirts、<br />

Ronaldo Ribeiro e Roberto Sakai<br />

帕林廷斯(Parintins):Domingos、Seu Paraná e comunidades<br />

da Vila Amazônia<br />

淡水河谷(Vale):André、Alexandre Castilho、Eduardo、<br />

Fernanda Magalhães、Jeovanis、João Carlos Magalhães、<br />

José Carlos Martins、Karla Melo、Luiz Batista、Paulo<br />

Bueno、Regina e Sérgio<br />

委内瑞拉(Venezuela):Blás e família、Fernando Juaregui、<br />

Pilar Alexander Blanco e Roger<br />

协助单位 SUPPORT<br />

CRAX Brasil - Sociedade de Pesquisa do Manejo e da<br />

Reprodução da Fauna Silvestre<br />

FUNPZA - Fundación Nacional de Parques y Acuarios de<br />

Venezuela<br />

ICMBio - Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da<br />

Biodiversidade<br />

INPA - Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas da Amazônia<br />

National Geographic Brasil<br />

Revista Globo Rural<br />

SOS Falconiformes<br />

Veracel