SARF seminar notes - Surrey County Council

SARF seminar notes - Surrey County Council

SARF seminar notes - Surrey County Council

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>Surrey</strong> Archaeological Research Framework<br />

Seminar 1: Summary Notes<br />

Palaeolithic Report back/Upper Palaeolithic/Mesolithic/Neolithic/Bronze Age<br />

24 January 2006<br />

Jon Cotton (Chairman of the Seminar) outlined the <strong>SARF</strong> process, based on the<br />

Olivier model. The <strong>seminar</strong> was intended to concentrate on the second of the Olivier<br />

steps, namely the identification of the gaps in present knowledge and the material<br />

resources potentially available within <strong>Surrey</strong> to help answer the gaps. He stressed that<br />

the <strong>seminar</strong> was a first step and that all participants were encouraged to submit<br />

thoughts both at the <strong>seminar</strong> and afterwards.<br />

All participants should have received copies of the papers by Jon Cotton and Danielle<br />

Schreve/Peter Harp and the condensed version of the longer paper by Roger Ellaby.<br />

Palaeolithic Report back<br />

Discussion points following Peter Harp’s presentation of the paper:<br />

1. Congratulations to Peter Harp for encouraging a focus on the ‘peopling the dots in<br />

the landscape’ in his studies. Vital that the ‘people’ focus be at the forefront of<br />

setting strategies for research into the Palaeolithic (Geoffrey Gower Kerslake).<br />

Strong support from Jon Cotton, as it was the focus on the lives of people in the<br />

past that was the lifeblood of modern museums.<br />

2. Confirmation that John Wymer’s Southern Rivers Project in the 1990s was in<br />

many ways the starting point of the present paper, and that Robin Tanner’s results<br />

had been passed to John Wymer.<br />

3. Modern administrative boundaries had no relevance whatsoever for the<br />

Palaeolithic and therefore the smallest region of study that made sense for this<br />

period was South East England (Jon Cotton).<br />

4. (i) Old SMR records across many parts of England show an association between<br />

‘Clactonian flint’ and Late Bonze Age pottery. It is clear that ‘flint technology’<br />

did not in fact advance in a Darwinian fashion from the simplistic to the complex.<br />

It was accordingly necessary to be very wary of attributions of flint artefacts to the<br />

Palaeolithic in the older literature (Richard Bradley). In response Peter Harp said<br />

that he was aware of flint described as ‘Clactonian’ being found in Bronze Age<br />

and Iron Age contexts, but in the framework paper he had been referring<br />

specifically to ‘Clactonian-type’ flint found on the Clay-with-flints which,<br />

although not necessarily Palaeolithic (and particularly not necessarily ‘Clactonian’<br />

i.e. Lower Palaeolithic) in date, appeared by its condition that it might<br />

nevertheless be earlier than the Bronze Age (giving as examples the material<br />

labelled by Martin Green in Dorset as ‘Clactonian’ and artefacts found by Tom<br />

Walls in <strong>Surrey</strong> labelled ‘Clactonian-type’).<br />

(ii) Do we have technology to identify different sources of flint (Alan Hall)? Peter<br />

Harp replied that Sieveking’s work in the 1970s on provenancing Neolithic flint<br />

axes had demonstrated the problems with identifying flint sources, specifically<br />

that while flint can often be ascribed to a particular stratum deposit (in the Chalk)<br />

these strata cover very large geographical areas. With regard to the Farnham<br />

Terrace A yellow, cherty flint, these might reflect a particular stratum of flint in<br />

1

the Chalk which had been incorporated into the Clay-with-flints and so been<br />

available to the early hominims before such a deposit may have been eroded<br />

through solifluction. Beyond that, with regard to the Palaeolithic in <strong>Surrey</strong>, we are<br />

largely limited to describing flint as being derived from either the Chalk, the Claywith-flints,<br />

or gravel deposits.<br />

(iii) Material from Farnham Terraces should be re-examined and if possible small<br />

undisturbed Terrace deposits located for future excavation (Peter Harp).<br />

(iv) Lithic scatters are a big imponderable, in this and later periods (Jon Cotton)<br />

(v) Solifluction hollows on Walton Heath seem worthy of further examination<br />

(David Bird). Although deposits in solifluction hollows on the Chilterns seem to<br />

date back to the Palaeolithic it is undecided whether the solifluction hollows and<br />

sink-holes on the North Downs are as early or whether they developed more<br />

recently; they are potentially important as the deposits of loess which collected in<br />

them may contain faunal remains (Peter Harp).<br />

5. It is difficult to apply the Olivier model to this early period and the Research<br />

Framework when drafted would need to take this into account (David Bird)<br />

Richard Bradley’s address<br />

His forthcoming book would synthesis the results for Great Britain and Ireland for the<br />

Neolithic through to the Middle Iron Age arising from the great explosion of data in<br />

the past 20 years. It had rapidly become apparent that the Irish or Scots experience<br />

was very different from that of Wessex or the Thames Valley. What general lessons<br />

had he learnt from the five years of research?<br />

• The three stage Olivier model appears administratively simple but in the real<br />

world all the stages are mixed. The acquisition of data in the field is as much a<br />

part of the intellectual research process as synthesis. ‘Diggers are not technicians,<br />

they are researchers’. And researchers at the very forefront of acquiring<br />

knowledge.<br />

• There is no point in asking questions of an SMR without first having an ‘emerging<br />

theory’ to inform the extraction of data.<br />

• But beware of preconceived ideas! For example, the English Heritage Thesaurus<br />

of Monument Types may inhibit the emergence of fresh ideas. The monument<br />

types so described may well be (and probably are) atypical for much of Britain.<br />

• What is a ‘resource’? Need to take ‘resources’ (e.g. data) and utilise these to<br />

produce ‘public understanding’.<br />

• ‘Use research at particular scales to solve particular problems’<br />

• Research should be about ‘ideas’ (that is, about ‘themes’) rather than about<br />

‘periods’. But ‘themes’ do need to be chronologically framed.<br />

• Too much archaeological thinking is still based on the mid-Victorian ‘Three Age’<br />

model with its underlying implication of a steady ‘Darwinian’ improvement in<br />

technology. Such steady improvements may not necessarily be true (see the<br />

discussion section in the previous section on the probable mis-assignment of LBA<br />

flintwork to the Palaeolithic).<br />

• Much more attention needs to be given to defining and exploring intermediate<br />

‘transition points’ within the Three Age model, as these may have more<br />

significance for societal changes. The Bronze Age is now better viewed as two<br />

very distinct periods, with other distinct ‘transition points’ within the Neolithic<br />

and within the traditionally Iron Age/RB periods.<br />

2

Turning more specifically to the generation of an Archaeological Research<br />

Framework for <strong>Surrey</strong>:<br />

• ‘Privilege the Local’ over the national. Politics constrains the Framework to a<br />

modern administrative area, so play to the strengths of Local Studies.<br />

• Relate all studies to the contemporary (e.g. Palaeolithic) local topography<br />

• Let the ‘evidence have its strengths’. There is no a priori reason why areas in<br />

<strong>Surrey</strong> should follow some assumed national or regional ‘norm’. It is now clear<br />

that North Scotland is similar to Ireland and not the rest of Scotland, and it<br />

appears that the Wessex Neolithic is totally individual and not a model for the<br />

Neolithic elsewhere. However, evidence is emerging that the experiences up and<br />

down the East Coast are much more homogenous in many different periods,<br />

whereas the experiences change as one moves east to west along the South Coast.<br />

• So much of the current archaeological story of Britain seems to have been written<br />

about atypical sites.<br />

• Experiences in <strong>Surrey</strong> are likely to have been different from those in Kent,<br />

Wessex or the Middle or Upper Thames Valley.<br />

The following points appear important in ‘privileging the local’ in <strong>Surrey</strong>:<br />

• Do not be apologetic for not finding ‘monuments’ – these probably never existed<br />

in many regions of <strong>Surrey</strong>.<br />

• Beware of all typographies of ‘monuments’ defined many years ago. The standard<br />

EH set may have survived because they were large and atypical or because they<br />

were located on marginal ground. The ‘grey literature’ implies that the ‘standard’<br />

types of monument are not being discovered in any number today despite the huge<br />

explosion in archaeological coverage arising from developer-funded excavations.<br />

• Most things don’t get into rivers ‘by accident’. How far back in prehistory was<br />

this a prevalent practice in this area? What was going on in the Middle Thames<br />

area, where deposition of all sorts of items seems common? Is there some special<br />

ritual significance to Mortlake Ware? (And to what extent is there evidence for<br />

similar practices on tributaries of the Thames in <strong>Surrey</strong>?).<br />

• <strong>Surrey</strong> has an unusual preponderance of heathland barrows in the South of<br />

England. Can these be integrated with circular Bronze Age ring-ditches and/or the<br />

less regular ‘ring-works’ (some of which have been shown to have Bronze Age<br />

origins)? <strong>Surrey</strong> has the opportunity to try to link ring-works, field systems and<br />

extra-mural settlements. How local are these distributions?<br />

• Generally, where are the open settlements in <strong>Surrey</strong>?<br />

• We now have enough information to try to place the many finds of hoards of<br />

metalwork in the context of past landscapes (the burnt mounds, the settlements,<br />

the field systems). There is even the possibility of trying to derive predictive GIS<br />

models based on the known information within the historic topography.<br />

• Study ‘blocks of land within <strong>Surrey</strong>’, rather than <strong>Surrey</strong> as a whole. <strong>Surrey</strong> has<br />

enough richness of material to permit this. Much <strong>Surrey</strong> material is distinctive and<br />

important.<br />

• The core aim of the Research Framework should be to derive “Prehistoric<br />

Archaeologies in areas within <strong>Surrey</strong>”, not of the county as a whole.<br />

3

Discussion points:<br />

1. Runnymede is a unique site, with few apparent ‘features’ but a huge area of<br />

settlement and very good preservation of environmental evidence in the alkaline<br />

soils (Dale Serjeantson). Yes, lots of middens buried under alluvium, but few<br />

house sites. Aerial photography not good at picking up Neolithic middens or<br />

Bronze Age settlements. As elsewhere in <strong>Surrey</strong> need other methods of<br />

‘prospecting’ – field-walking, magnetometry (Richard Bradley).<br />

2. Rivers and/or river valley ‘corridors’ very important (Dale Serjeantson, David<br />

Bird), possibly more important than ridgeways (Richard Bradley).<br />

3. Changing views as to the degree to which there was thick forest cover (David<br />

Bird, Jon Cotton).<br />

4. Should investigate ‘blocks of land and features therein’ and inter-relationships of<br />

distinct blocks of land (Geoffrey Gower Kerslake). Look especially for ‘negative<br />

evidence’ on blocks of land where it should have survived if it was ever present<br />

(Richard Bradley).<br />

5. Why so little evidence of early settlement on chalk in <strong>Surrey</strong> (Jon Cotton)?<br />

Wessex not apparently forested. Currently in West Sussex much evidence coming<br />

to light of dense settlement on the loess of the coastal plain, whereas the surviving<br />

Neolithic ‘monuments’ are all on the chalk (Richard Bradley). But most of<br />

<strong>Surrey</strong>’s chalk is different, being covered with ‘Clay with Flints’ (David Bird).<br />

6. Only one <strong>Surrey</strong> hillfort is on chalk, the others are all on the Greensand. These all<br />

appear very different in function to the classic sites in Wessex (David Bird, Jon<br />

Cotton). But examples of even the classic type appear different one to another<br />

when excavated. The absence of finds from within <strong>Surrey</strong> Greensand hillforts may<br />

well reveal correctly ‘no substantial activity’ within the structures (Richard<br />

Bradley). How do we infer at the level of the ‘people’ what was going on,<br />

especially if this were essentially based on very local circumstances (David Bird)?<br />

7. Mesolithic material is present across many geological areas of <strong>Surrey</strong> and not just<br />

on the Greensand; the common belief that the Mesolithic is restricted to the<br />

Greensand is a myth. Much Mesolithic material is now coming from the Wealden<br />

clays. (Roger Ellaby, Robin Tanner).<br />

8. Repeated field-walking over 4 sq miles at Outwood over many years has revealed<br />

evidence of all periods. But the surface archaeology is fragile and fleeting. One<br />

field was walked for 12 years before a particular ploughing brought up a<br />

concentration of Iron Age/Romano-British pottery (Robin Tanner).<br />

9. Published geological maps of <strong>Surrey</strong> are based on relatively few exposures of the<br />

underlying materials, so important geological boundaries are interpolated<br />

(guessed) over large distances (Tim Wilcock).<br />

10. Soils can change quite quickly over time, e.g. significant soil changes in the<br />

Neolithic and LBA on Cranborne Chase (Richard Bradley). Soils on the <strong>Surrey</strong><br />

heaths appear to show signs of podsolisation even as field systems were being laid<br />

out (Judie English). Other examples of field systems being laid out in EBA and<br />

gone by LBA, before a marked discontinuity in the type of field systems laid out<br />

in the IA. Reference to David Yates’ extensive work on understanding the<br />

development of field systems in Southern England (Richard Bradley). The very<br />

clear plough marks discovered on sandy islands next to the Thames in South<br />

London could imply that early cultivation of these marginal lands was very shortlived<br />

(Jon Cotton). Perhaps there was not so much of an intensification of<br />

agriculture on existing land in the EBA, but rather the bringing under cultivation<br />

4

of much surrounding land, which then quite rapidly was abandoned (Richard<br />

Bradley). Seems to have been the case in the Weald (Roger Ellaby) and in the<br />

New Forest (Richard Bradley). Thus, as identified earlier, the archaeological<br />

evidence within <strong>Surrey</strong> heathland may well be of more than local significance.<br />

11. The current Royal Holloway College palaeo-environmental studies are a key stage<br />

in being able to understand more of the ‘people in the landscape’ (Jon Cotton).<br />

There is comparatively little known about the detail of the geomorphological<br />

development of the <strong>Surrey</strong> landscape, including its rivers. What was the palaeotopography<br />

at different periods?<br />

Finally, some issues regarding people and processes:<br />

• Need to develop ‘leaders’ in local areas to enthuse and encourage volunteers to<br />

take an active part. With the apparent professionalisation of archaeology, many<br />

potentially interested volunteers could be daunted in putting themselves forward.<br />

We need to build confidence among volunteers in order to grow the people<br />

resource base to allow many of the questions to be tackled (Alan Hall).<br />

• Hope that the <strong>Surrey</strong> Archaeological Society can restart training programmes<br />

(David Bird).<br />

• Volunteers still needed to help with the team publishing old sites (David Bird)<br />

• Need to build local archaeology on a bottom-up as opposed to a top-down basis,<br />

with ‘de-professionalisation’ – there should be no distinction between<br />

professionals and volunteers. There are massive opportunities for research at all<br />

levels (Jon Cotton).<br />

• It had been suggested earlier in the <strong>seminar</strong> that for the Palaeolithic the ‘smallest<br />

region that made sense was the SE England’ (Jon Cotton – see above). It would<br />

therefore be necessary for volunteers working on this period to gain more than a<br />

purely local basis of knowledge; it might even be that some locality in <strong>Surrey</strong><br />

produced a regionally atypical site, and this would need to be noted and , if<br />

possible, explained (Peter Youngs).<br />

• A discussion on what might be done with the large amount of unstratified lithic<br />

material in various <strong>Surrey</strong> museums? A difficult problem, possibly not central to<br />

deriving a Research Strategy (Richard Savage, Peter Harp, Jon Cotton).<br />

Jon Cotton closed the meeting by reiterating the request for thoughts. There was no<br />

hidden agenda. The Steering Group were genuinely seeking views from all involved<br />

in Archaeology in <strong>Surrey</strong>. Thoughts, particularly around the ‘Gaps in Current<br />

Knowledge’, could be sent by letter, e-mail or any other medium to any member of<br />

the Steering Group.<br />

RWS<br />

26.1.06<br />

5

<strong>Surrey</strong> Archaeological Research Framework<br />

Seminar 2: Summary Notes<br />

Iron Age and Romano-British periods<br />

31 January 2006<br />

Jon Cotton (Chairman of the Seminar) outlined the <strong>SARF</strong> process, based on the<br />

Olivier model. The <strong>seminar</strong> was intended to concentrate on the second of the Olivier<br />

steps, namely the identification of the gaps in present knowledge and the material<br />

resources potentially available within <strong>Surrey</strong> to help answer the gaps. The first<br />

<strong>seminar</strong> on the earlier prehistoric periods had stressed the importance of “building<br />

from the bottom-up, rather than from the top-down” by “privileging the local” and<br />

concentrating on “reconstructing life on topographic blocks of land within <strong>Surrey</strong>”,<br />

rather than across the whole of <strong>Surrey</strong>. He stressed that the <strong>seminar</strong> was a first step<br />

and that all participants were encouraged to submit thoughts both at the <strong>seminar</strong> and<br />

afterwards.<br />

The ‘Iron Age’ period(s)<br />

JD Hill’s address - “How do you fill a ‘black hole’?<br />

Much of the content of the presentation had been laid out in the national agenda<br />

“Understanding The British Iron Age: an Agenda for Action” by C Haselgrove et al in<br />

2001, published by the Trust for Wessex Archaeology on behalf of the Iron Age<br />

Research Seminar and the Prehistoric Society (funded by English Heritage and<br />

Scottish History). JD handed out around 20 copies of this publication, in which <strong>Surrey</strong><br />

was classified as the only <strong>County</strong> in the South East where knowledge of the Iron Age<br />

was akin to a ‘black hole’.<br />

But parts of the evidence from <strong>Surrey</strong> were very strong and further advances in<br />

understanding in <strong>Surrey</strong> could be of relevance both regionally and nationally. Our<br />

understanding of the Iron Age across Britain was undergoing significant<br />

transformation over the past 15 years and two new ‘edited’ volumes of papers were<br />

due to be published by Oxbow later this year, as part of the process of building a<br />

framework for a new synthesis of the Iron Age. But even these volumes could not<br />

take account fully of the explosion in data arising from the ‘grey literature’ from<br />

developer-funded evaluations and excavations.<br />

Key points from the national agenda included:<br />

• The traditional division into Early, Middle and Late IA periods was inadequate.<br />

• Existing chronologies were based on too few sites and too few data points (e.g.<br />

much of the synthesis for Southern England was based on the excavations at<br />

Danebury, but the pottery sequences in Kent, for example, do not match those at<br />

Danebury).<br />

• Carbon-dating for IA sites should be obligatory; most sites should produce enough<br />

carbonised seed for accurate dating. The difficulties of the calibration curve<br />

between 800 to 400BC should not be exaggerated, as sufficient samples and<br />

Bayesian statistical techniques would often lead to useful gains in knowledge.<br />

1

• Any local IA site with pottery securely datable by association would be of<br />

national significance.<br />

• IA ‘site topographies’ seem to be heavily driven by ritual. Thus all ditch terminals<br />

should be fully excavated and at least 20% of ring-ditches (rather than as little as<br />

2% of ditches as might be common of ditches forming field boundaries).<br />

<strong>Surrey</strong>’s IA should not be seen as difficult or a ‘problem’. It might well be that <strong>Surrey</strong><br />

would prove to be a litmus test for what was happening throughout the Greater<br />

London region. <strong>Surrey</strong> contained far more ‘marginal’ land than some of the ‘classic’<br />

areas and thus might be of greater relevance to the development of the Iron Age<br />

outside those classic areas.<br />

It seemed that the present lumping of IA sites of many different dates into a single<br />

‘collapsed’ IA synthesis hid very significant differences between the periods. Current<br />

thinking was based on a three-fold division (but it was not that of the traditional Early,<br />

Middle and Late IAs). The current three-fold division could be characterised as:<br />

(1) The Late Bronze Age<br />

(2) “The Gap”, encompassing the traditional Early and Middle IA.<br />

(3) The “Later” IA, encompassing the end of the Middle IA, all the Late IA and<br />

on into the first and second centuries AD.<br />

What evidence might be found in <strong>Surrey</strong> to help develop a synthesis on these lines?<br />

Taking each division in turn:<br />

• <strong>Surrey</strong> is very rich in LBA pottery, with settlement sites from the hills above<br />

Carshalton to the river terraces of the Thames. The so-called ‘Celtic fields’ in<br />

the region seem to belong to this period. There seems to have been an abrupt<br />

and rapid collapse of this society, but when did this happen? Emerging<br />

evidence suggests that in the Thames Valley it might have been around 800BC<br />

and thus not immediately at the end of the Bronze Age. ‘Post Deveril<br />

Rimbury’ assemblages have recently been dated to the EIA (i.e. post 800BC).<br />

• The following ‘Gap’ period in the Thames Valley and across much of the<br />

South East seems to have lasted from about 700/600BC to 300/200BC. In<br />

contrast to the earlier period there are very few clear settlement sites, but<br />

rather lots of wells and pit ‘scatters’. Evidence from the Channel Tunnel link<br />

work in Kent suggests that feasting was of importance to this society. What is<br />

this landscape about? Has there been a substantial fall in population? Is there<br />

possibly an agglomeration of previously scattered farms into more intensively<br />

occupied ‘settlements’, perhaps on hilltops rather than in the fertile valley<br />

bottoms? What part, if any, do the hillforts, especially the enigmatic <strong>Surrey</strong><br />

hillforts on the Greensand, play in this period?<br />

• There now occurs a radical change in the landscape, especially in West <strong>Surrey</strong>,<br />

with the emergence of many roundhouses associated with paddocks and<br />

trackways. The process is more patchy in East <strong>Surrey</strong> and Kent, but there are<br />

areas (e.g. around Ashford) where similar developments occur across blocks<br />

of landscape 15km to 20km wide. When does this phenomenon start? Current<br />

evidence suggests the Later IA, rather than the Late IA. Precise dating by<br />

pottery form is difficult. If the process is as rapid as it seems, where have all<br />

the people come from? Have they now left the hillforts and any postulated<br />

2

hilltop settlements and moved back to live on the valley bottoms, creating new<br />

paddocks and trackways?<br />

There seems to be a considerable ‘blurring’ on the traditional boundary between the<br />

Middle IA and the Late IA. Around 200/175BC there appears to be an ‘explosion’ in<br />

the adoption of iron, and a little later in metalwork in general and in the introduction<br />

of coinage (with recent evidence suggesting that Gallo-Belgic B coins were being<br />

minted in Hampshire as well as on the Continent). What changes in society have<br />

produced these changes, which appear to be broadly coincident with the emergence of<br />

the new landscape? Recent work suggests difficulties with the previous assumptions<br />

about ‘tribes’ and ‘affiliations’ in Southern England in this period.<br />

In summary, ‘regionality’ appears important throughout the Iron Age. The classic<br />

hillforts seem local to Wessex. The emergence of ‘patterned landscapes’ 15km to<br />

20km across during the Later Iron Age imply that there may be no parallels with<br />

immediately neighbouring areas at any given point in time. Studies based on local<br />

‘blocks of land’ seem particularly relevant. And what of the transition to the Romano-<br />

British landscape? Did regionality remain an important factor?<br />

Discussion points:<br />

1. <strong>Surrey</strong> is very rich in LBA material and this warrants special attention (Jon<br />

Cotton).<br />

2. The <strong>Surrey</strong> Greensand hillforts are clearly important and their use and function<br />

needs to be better understood. Because of their location and nature, the problems<br />

will not be solved by way of developer-funded archaeology and so should be a<br />

good topic for the <strong>Surrey</strong> Arch Society to tackle. These hillforts appear to face the<br />

Weald; we need to understand better whether they are involved in transhumance<br />

and, if so, work out the routes connecting them to other territories. It is thought<br />

that early routes into the Weald are aligned north-south, whereas some east-west<br />

routes are postulated in later times (e.g. in the medieval). (Peter Horitz, JD Hill,<br />

Jon Cotton, David Bird, Robin Tanner).<br />

3. How best to draw together an up-to-date list of all of the relevant ‘grey literature’,<br />

most of which is deposited at the SMR? Is it worth setting up a project team to do<br />

this? Probably not, as most <strong>Surrey</strong> grey literature is itemised in the Annual<br />

Roundups in the Society’s Collections or in the London Archaeologist. However,<br />

some reports are made very late – and these can only be tracked down by talking<br />

to the archaeological units concerned. The point was made that ‘relevance’ can<br />

only be determined in the light of a research agenda. (Tim Wilcock, Frank<br />

Pemberton, JD Hill, David Bird, Jon Cotton).<br />

4. The material from the old excavations at Purberry Shot in Ewell (dug in the 1930s<br />

and published after WWII) would merit investigation as this seemed to be a<br />

transitional MIA site which was difficult to assess (Peggy Bedwell, Jon Cotton). Is<br />

there any carbon-dateable material in the museum archives relating to this site (JD<br />

Hill)?<br />

5. While Sussex has more of an IA framework in place, there are still many<br />

difficulties with pottery sequences, with a lack of well-stratified and well-dated<br />

material. Work by Sue Hamilton has shown that the hillforts on the South Downs<br />

are very different from Danebury. One technique to clarify some of the older<br />

reports would be to re-excavate the old trenches to redraw the sections (David<br />

3

Rudling). There was support for looking critically at old reports and carrying out<br />

targeted returns to old sites, both in <strong>Surrey</strong> and in West London. Some of the West<br />

London sites might well ‘plug gaps’ in existing understanding (Alan Hall, Jon<br />

Cotton).<br />

6. There was a considerable discussion on the place of environmental evidence (both<br />

of fauna and flora) in trying to elucidate whether we were seeing evidence of<br />

transhumance per se, or some other form of ‘seasonality’. For example, do the<br />

concentrations of roundhouse ditches at Mucking in Essex and Tongham in <strong>Surrey</strong><br />

represent ‘villages’ of houses occupied concurrently or a single family returning<br />

to the site for the same season each year for many generations? A site at Daventry<br />

in the Midlands has the remains of hundreds of roundhouses but floods each<br />

winter. There are considerable doubts about the validity of the standard model of<br />

single roundhouses in ‘farmyards’, at least in Eastern England (the original<br />

Wessex examples may be a practice local to that area or perhaps even an<br />

exception in that area). Furthermore, many roundhouses contain very little pottery,<br />

far less than would be expected from a house occupied for many years. Were<br />

people more settled before the “Gap period” and then again after it, but did not<br />

live in the same house all year round during it? Attention was drawn to the<br />

dangers of imposing the medieval model of transhumance on earlier periods (Jon<br />

Cotton, Peter Youngs, JD Hill, David Bird).<br />

7. Why is there so much metalwork deposited in the Thames during this period,<br />

much of it brought in from considerable distances? What is the ritual significance<br />

of this? And how does the practice change over time? (JD Hill, Jon Cotton).<br />

8. Also a discussion on our knowledge of iron-working techniques. <strong>Surrey</strong> has quite<br />

a number of sites, including Brooklands (early), Thorpe Leas (later), Bagshot<br />

(later) and the Wealden sites (mainly later). It is difficult to draw up any<br />

connections between the sites. Brooklands is odd in many ways, early and very<br />

little production; it may be typical of earlier periods (800BC to 250BC).<br />

Production of iron seems to take off about 250BC, with a marked intensification<br />

around 100BC. A re-examination of the Purberry Shot material originally<br />

classified as slag suggests 30+ furnace bottoms; but are some of these actually<br />

hearth bottoms? A misidentification would lead to incorrect conclusions as to the<br />

prevalence of production versus smithing, the latter being more likely to be<br />

widespread. (JD Hill, Jeremy Hodgkinson, David Bird).<br />

9. Most IA sites have a little non-ferrous metalwork and it seems clear that<br />

production of such items was dispersed rather than concentrated (only five IA<br />

sites are known across the whole of Britain that show concentrated non-ferrous<br />

production). As already mentioned in the presentation, there seems to be a sudden<br />

increase in the number of brooches, dress accessories and coins, becoming an<br />

‘explosion’ during the first century BC. This appears to be a period of massive,<br />

radical change in society (Frank Pemberton, JD Hill, Jon Cotton). However, while<br />

Gallo-Belgic coins are coming to light under the Portable Antiquities Scheme,<br />

other IA finds are remarkably few – only 5 or so fragments out of 3,000+ objects<br />

recorded so far in <strong>Surrey</strong> (David Williams).<br />

10. How can we find new IA occupation sites? Aerial photography and field-walking<br />

are traditional methods in many areas of the country, but are not well suited to<br />

conditions in much of <strong>Surrey</strong>. ‘Evaluation’ of sites under PPG16 commonly<br />

involves trenches on only 2% of a site and is unlikely to pick up IA occupation.<br />

Areas on the river terraces are best ‘stripped and mapped’ before large-scale<br />

mineral extraction. (Charles Abdy, Richard Savage, JD Hill).<br />

4

The Romano-British period<br />

With most of the time at the Seminar devoted to the Iron Age, the session on the<br />

Romano-British period had to be compressed.<br />

The Roman Studies Group had drawn up the following list of themes:<br />

• Political and Administrative Geography<br />

• Communications<br />

• Security<br />

• Settlements<br />

• Land Use and Environment<br />

• Economy and Material Culture<br />

• Belief and Burial<br />

• Transition to the post-Roman world<br />

JD Hill suggested three additions to the list to aid practical research in a local context:<br />

• Food<br />

• Dress and Appearance<br />

• ‘Living Space’ (the form of houses)<br />

The Roman Studies Group has either set up or is setting up three Study Groups as<br />

follows:<br />

Settlements (Frank Pemberton). Would concentrate initially on Ewell and Dorking,<br />

with an archive study of Purberry Shot and other relevant sites. Were currently<br />

constructing full pottery archives for Ewell with a view to working out the pottery<br />

distribution for Ewell as a whole (along the lines of the study of Elms Farm in Essex).<br />

Would also be looking at coin distribution in Ewell. Where had the population come<br />

from? Was it resident or visiting? What relationship with the IA type sites up on the<br />

North Downs? Continuity of agricultural production?<br />

Points raised in discussion:<br />

1. Pleased that terminology remained ‘settlement’ and did not pre-judge the evidence<br />

(JD Hill).<br />

2. Archive of the King William IV site in Ewell contains over 25,000 bones or<br />

fragments of bone. Some analysis started but many questions could be asked of<br />

this material, including about butchery practices (Jon Cotton).<br />

3. The Ouse valley in Sussex showed similar location of more romanised dwellings<br />

in the valley bottoms with less romanised farming sites higher on the South<br />

Downs. However, detailed analysis showed that many of the sites were not<br />

occupied continuously from the 1 st to 4 th centuries. What is the intensity of use of<br />

different parts of the landscape over time? How do the different elements interact<br />

with each other at each period? (David Rudling).<br />

4. The proximity of Ewell to London merited further investigation. Who were the<br />

farmers producing for? To what extent was production destined for London? (Jim<br />

Davidson).<br />

Roads: (Alan Hall). The Group had developed a cost-effective technique and using<br />

this had in one and a half seasons of work located the route of Stane Street from<br />

Ashstead to Church Field in Ewell. Their work showed that the section within Ewell<br />

was only in use in the 1 st Century, so it may then have been diverted. The Group<br />

5

would now be turning their attention to the ‘missing’ section of the presumed<br />

London-Winchester road from Ewell to Farnham.<br />

Points raised in discussion:<br />

1. What was the impact of the Roman road-building programme on the pre-existing<br />

IA landscapes through which it passed? (Jon Cotton)<br />

2. It would be important to the research framework as a whole that attention was<br />

paid to the other Roman roads in <strong>Surrey</strong> (e.g. the continuation of the spur from<br />

Stane Street to Farley Heath) and to other routes to articulate settlements within<br />

the landscape (Jeremy Hodgkinson, Alan Hall).<br />

Villas: (David Bird) Surprisingly little was known about the various <strong>Surrey</strong> villas,<br />

which for the most part had been excavated in the 19 th or first half of the 20 th century.<br />

The present state of knowledge had been summarised in David’s recent book on<br />

Roman <strong>Surrey</strong> (published by Tempus, 2004). Currently envisaged work included:<br />

• A re-examination of old archives<br />

• Carefully targeted work in the field (initially at Ashstead, funded by the site’s<br />

owners, the Corporation of London).<br />

• A consideration of the non-villa settlements (i.e. the place of the villas in the<br />

contemporary landscape).<br />

• A consideration of the importance of woodland in the contemporary<br />

landscape, although this posed difficult problems as to evidence.<br />

Points raised in discussion:<br />

1. It appeared that a study of the Romano-British landscape would be a good way<br />

forward, integrating evidence from the SMR (including the many RB burials), the<br />

Portable Antiquities Scheme and from aerial photography (Frank Pemberton,<br />

Richard Savage, Jon Cotton).<br />

2. Environmental evidence was desperately short for this period (David Bird).<br />

3. It might be helpful to mount a specific study of the building materials used in the<br />

construction of the <strong>Surrey</strong> villas.<br />

4. There should be some aspect of the Research Framework devoted to Belief and<br />

Burial, given the significance of the ritual sites in <strong>Surrey</strong> (Jon Cotton).<br />

5. There should be some aspect of the Research Framework devoted to the transition<br />

in the early 5 th century, given the importance and distribution of the early ‘Pagan<br />

Saxon’ cemeteries in <strong>Surrey</strong>. Pottery dating for this period still had many<br />

uncertainties. (Jim Davidson, JD Hill, Jon Cotton, David Bird).<br />

Jon Cotton closed the meeting by reiterating the request for thoughts, which could be<br />

sent by letter, e-mail or any other medium to any member of the Steering Group.<br />

RWS<br />

3.2.06<br />

6

<strong>Surrey</strong> Archaeological Research Framework<br />

Seminar 3: Summary Notes<br />

Early Saxon/Later Saxon/Medieval<br />

14 February 2006<br />

Peter Youngs (Chairman of the Seminar) introduced the third <strong>seminar</strong>, which like the<br />

earlier <strong>seminar</strong>s was intended to be part of the process whereby ‘bottom up’ studies<br />

on local areas within <strong>Surrey</strong> would in time enable a new synthesis for the<br />

development of <strong>Surrey</strong>. Traditionally the periods under discussion in this <strong>seminar</strong> had<br />

been represented as a number of transitions at key dates but a major theme of any new<br />

synthesis was likely to be the relative importance of continuity over change, with<br />

change occurring more slowly and quite possibly at dates rather different from the<br />

‘headline’ dates. The periods discussed in the earlier <strong>seminar</strong>s have little or no<br />

contemporary documentary evidence but such evidence becomes increasingly<br />

available for the Later Saxon through Medieval periods and needs to be taken into<br />

account along with archaeological evidence. Peter emphasised that local studies<br />

needed to be grounded in a wider, regional appreciation if important patterns – and<br />

equally local exceptions to regional patterns - were to be recognised and explained.<br />

Mary Alexander’s address<br />

Mary referred to the full <strong>notes</strong> by herself, Denis Turner and Judie English that had<br />

been issued to all <strong>seminar</strong> participants before the meeting. She had been asked to be<br />

‘provocative’ in her address and the points she would be making should be taken in<br />

that light.<br />

The ‘Early Saxon’ period<br />

It appeared from the evidence of brooches that East <strong>Surrey</strong> was closely connected to<br />

Kent and from the evidence of place names that West <strong>Surrey</strong> had close links with<br />

Berkshire. Matters requiring study included:<br />

• The relationship of the presumed ‘regiones’ to the later county boundaries.<br />

• Whether the ‘-ingas’ names in West <strong>Surrey</strong> were Early or Middle Saxon.<br />

• Whether Middlesex and <strong>Surrey</strong> were once a single unit (as the eastern and western<br />

county borders of each were almost continuous across the Thames).<br />

• Whether <strong>Surrey</strong> had ever been an early kingdom, later swallowed up by others.<br />

• The implications of the Early Pagan Saxon cemetery at Guildown. Is it truly an<br />

outlier of the group otherwise known around Croydon and Mitcham or are there<br />

others not yet discovered? If it is truly an outlier, what is the significance of this?<br />

• The existence and period of use of any ‘London Way’ from the West, as<br />

postulated by Hill, coming from Farnham through Guildford and on to Dorking<br />

before going up Stane Street to London.<br />

The ‘Middle Saxon’ periods<br />

• When did the distinctive ‘north-south’ parishes across the North Downs and<br />

Greensand Ridge develop?<br />

1

• Should there be a Minster in each Hundred? Was there ever a Minster at Stoke, or<br />

was perhaps the original settlement at Guildford called Stoke and the name then<br />

migrated northwards? Did Farnham have a Minster?<br />

• Even the later (7 th century) burial sites seem to be concentrated on the dip slope of<br />

the Downs. Does this reflect the settlement density of the time? Was there very<br />

little Saxon settlement south of the Downs?<br />

• But we have very few known settlement sites in <strong>Surrey</strong>’s archaeological record<br />

anywhere.<br />

• And thus almost no knowledge of their building style in <strong>Surrey</strong> and the<br />

relationship of this to the emergence of the earliest known medieval buildings in<br />

the county.<br />

• What are the implications (and dating) of the ‘execution cemetery’ at Guildown at<br />

the site of the much earlier Pagan Saxon cemetery. Does continuity of use – or at<br />

least the re-use of the site respecting the position of the earlier graves – imply the<br />

continuing existence of landscape features, such as barrows?<br />

• Need much more work on the religious landscape of the growing Christian<br />

church, both the Minsters and the later spread of churches close to manors and in<br />

the villages. Does the survival of so many Late Saxon features in <strong>Surrey</strong> churches<br />

imply that <strong>Surrey</strong> remained a rural backwater for centuries?<br />

• Guildford deserves major study, as its early development is not clear. The Saxon<br />

planned town appears to have been laid out in the mid 10 th century, but is the<br />

church contemporary? We have no archaeological section across the presumed<br />

Saxon defences; there may be an opportunity to locate the northern line of<br />

defences in the planned extension to the Friary Centre in the next few years.<br />

• The burhs in the Burghal Hidage of 914 merit further study (e.g. Eashing and<br />

Southwark). A section across the presumed line of defence of the burh at Eashing<br />

would seem to be a suitable first step.<br />

• And finally, what about the Vikings in <strong>Surrey</strong>? Were they just transient passers-by<br />

or are there more significant sites awaiting discovery?<br />

The Medieval period (to 1500)<br />

• How did the villages and field systems develop?<br />

• What is the significance of the various ‘castle’ and ‘moated’ sites?<br />

• What is the impact in the wider landscape of the major religious sites (including<br />

Chertsey, Waverley and Newark)? These three sites were dug before the<br />

emergence of modern standards and although ground plans were ascertained there<br />

is little on their development over time, and few small finds have survived for<br />

study today. The more recent excavations of the Friary at Guildford have<br />

illustrated aspects of its development alongside the town. There is much<br />

documentary record of the Chertsey Abbey holdings but little is known about the<br />

location of barns, fish-ponds, etc on their various holdings. A geophysical survey<br />

of the lands immediately around Newark Priory is planned.<br />

• There are many issues involving the early development of the various industries in<br />

<strong>Surrey</strong> (e.g. potteries, tileries, wool, iron, glass, fullers’ earth and building stone).<br />

2

Discussion points<br />

The various discussion points made are here grouped together (perhaps a little<br />

arbitrarily) into the overarching themes identified in the summing up at the end of the<br />

Seminar. The final two sections summarise the discussions on ‘archaeological<br />

procedure’ and ways that the Society might develop to aid future research.<br />

1. Early Saxon period<br />

i) The Guildown cemetery was potentially extremely important. It was the only early<br />

cemetery apparently lying far from a Roman road. If this could be shown to be the<br />

case, then the site might tell us more about developments in this early period than<br />

the cluster of sites nearer London (Geoffrey Gower-Kerslake).<br />

ii) The dating of the ‘-ingas’ place names was controversial. Mary Alexander had<br />

favoured a Middle Saxon date whereas David Bird favoured an Early date, based<br />

on the observation that ‘ingas’ names occurred only in areas that did not have<br />

Early Saxon cemeteries; he postulates that these areas were still occupied by<br />

‘Britons’ as opposed to Saxons.<br />

2. Settlement and Population within areas of <strong>Surrey</strong><br />

Has <strong>Surrey</strong> always been a fairly lightly populated rural and wooded area? There are<br />

no large Romano-British towns and little archaeological evidence as yet of Saxon<br />

settlements. Southwark and Kingston are closely connected with London and the<br />

Thames. Guildford appears to be a late Saxon planned town. <strong>Surrey</strong> has no large<br />

surviving churches but many features of earlier small churches have survived to the<br />

present day (e.g. Compton, Wonersh, Alford, Godalming, and Cranleigh south of the<br />

Downs, Pyrford and Wisley in the Wey valley north of the Downs, together with the<br />

early tower of St Mary’s in Guildford).<br />

i) In other areas of England we see many settlements created from the 7 th century<br />

onwards and we should study the morphology of these to see if they are applicable<br />

to any areas in <strong>Surrey</strong> (Judie English). But these areas of early settlement patterns<br />

elsewhere generally lie in the broad band of good soils which run from Somerset<br />

through Bristol and up through the Midlands and East Anglia; it is probably<br />

significant that the areas of large Saxon and Medieval villages in the Midlands are<br />

coincident with the areas that contain large numbers of small Romano-British<br />

towns. These are the areas where the soils and agricultural possibilities support<br />

large numbers of people (David Bird). Much of <strong>Surrey</strong> is either wooded or<br />

heathland and has been agriculturally intractable throughout these periods (Peter<br />

Youngs, Jeremy Hodgkinson). Settlement may thus be more dispersed and not so<br />

intensive in total.<br />

ii) The history of Late Medieval <strong>Surrey</strong> (i.e. in the 14 th and 15 th centuries) is a bit of a<br />

mystery. Elsewhere this period seems to have seen boom to bust conditions (e.g.<br />

in the Midlands, with the many Deserted Medieval Villages of the period) and<br />

changes to a diet based more on meat, with changes to land use. Doesn’t seem to<br />

have happened in <strong>Surrey</strong> – perhaps because there were no boom conditions in<br />

<strong>Surrey</strong> earlier? Certainly there are no Perpendicular churches, despite the wellattested<br />

woollen industries in West <strong>Surrey</strong>. Is there any evidence of changes to the<br />

<strong>Surrey</strong> landscape in this period? But perhaps the development of vernacular<br />

3

uildings in <strong>Surrey</strong> during this period suggests a rather more positive picture?<br />

(Nigel Saul).<br />

iii) To date the work of the Villages Study Group cannot shed much light on these<br />

earlier periods (David Bird).<br />

iv) There were no large aristocratic landowners based in <strong>Surrey</strong> and this might be a<br />

major contributing factor to the failure to develop large churches in the later<br />

medieval periods. The Victoria <strong>County</strong> History contains a huge amount of<br />

information about the gentry of <strong>Surrey</strong> in the later medieval period and this could<br />

repay study to see what light it might throw on the development of villages and<br />

small towns in <strong>Surrey</strong> (Mary Alexander).<br />

3. Transport and Communications (roads and rivers)<br />

Little is known of the Saxon and medieval road patterns, but many doubt that<br />

movement around the <strong>County</strong> was as difficult as it was reputed to be in the 18 th<br />

century.<br />

i) The High Street at Guildford points to Leatherhead, not Dorking. Is this not a<br />

more likely early route to London than going from Guildford to Dorking and then<br />

up Stane Street? The route up Pewsey Hill was a drove road in the 18 th century.<br />

(Dennis Turner). Precise line of High Street likely to have been dictated by local<br />

topography, rather than its destination (David Bird).<br />

ii) Where precisely was the original ford at Guildford? In the 17 th century it lay<br />

immediately north of the town bridge – which itself led directly to the High Street.<br />

Some writers have conjectured the original ford as being located upstream at St<br />

Catherine’s but this seems unlikely on geographical grounds – if it were located<br />

there it would be subject to floods and the passage of a wide marshy area. It could<br />

only have been located in or to the north of constricted passage through the North<br />

Downs, possibly as far north as Woodbridge (Dennis Turner).<br />

iii) The Saxon and medieval road systems are not understood. Were there north-south<br />

roads and trackways in use to facilitate seasonal movement into and out of the<br />

Weald? Were these the continuation of prehistoric and Romano-British routes?<br />

What about east-west road links, which also appear important (Judie English)?<br />

And salt routes (David Bird)? Some RB and medieval products (e.g. tiles and<br />

building stone) could only have been moved to London by road, as there are no<br />

suitable rivers connecting areas of production around Reigate with London (Mary<br />

Alexander). Little evidence of river transport being important other than on the<br />

Thames, with evidence regarding the Wey tending to suggest only local and<br />

down-river transport (of timber and building materials in particular) (Mary<br />

Alexander, Richard Savage). Down-river transport has also been evidenced in the<br />

Chilterns (Dennis Turner). The Mole and the Wandle seem unlikely to have been<br />

suitable for much river traffic at any period.<br />

iv) It was important in gauging the place of <strong>Surrey</strong> in the wider regional picture that<br />

we develop a better understanding of the road system. A study of the early<br />

manorial records would probably reveal significant detail about the ‘public<br />

obligations’ to maintain roads, causeways and bridges, and thus the location of the<br />

road network (Nigel Saul).<br />

4

4. The Religious ‘landscape’ and its implications<br />

i) Consideration of Stoke as the postulated site of an early Minster should not be<br />

subject to preconceptions (Geoffrey Gower-Kerslake). Mary Alexander replied<br />

that she was unconvinced by John Blair’s evidence that it might be early.<br />

ii) There was much to understand in the development of parishes and other<br />

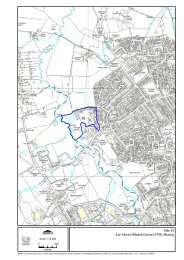

ecclesiastical establishments (Peter Youngs). The map displayed showed that<br />

priories had been created at many of the settlements at the foot of the scarp slope<br />

of the North Downs. Parishes in the NW of <strong>Surrey</strong> did not show the pronounced<br />

north-south pattern of those straddling the Downs and the Greensand ridge.<br />

However, these NW parishes originally lay either to the north of the Wey or to its<br />

south with the Wey as a parish boundary, with the parish churches almost<br />

invariably occupying plots that fronted the water meadows of the Wey. Parishes in<br />

the SW of the county often straddled the Wey (Richard Savage).<br />

iii) The Cistercian estates could be thought of as ‘industrial holdings’ designed to<br />

maximise the returns from agriculture; while details of the village settlements<br />

within the Chertsey estates were reasonably well known from the Charters this<br />

was not the case for the location of fishponds, tithe barns and the rest of the<br />

‘agricultural apparatus’ of the large monastic estates in <strong>Surrey</strong> (Judie English,<br />

Nigel Saul, Dennis Turner). Alan Crocker recommended James Bond’s “Monastic<br />

Landscapes”. Judie English is currently carrying out investigations into the<br />

Waverley monastic estates. The area around Newark Priory from Pyrford down to<br />

Wisley shows the creation of many new channels and remodelling of the historic<br />

course of the river, and at least some of these works may be associated with the<br />

foundation of the Priory at the end of the 12 th century. One of the newly created<br />

streams is a leat taken from the Wey to provide additional power to Ockham Mill,<br />

which lies a kilometre northeast of the take-off point in a side valley of the Wey.<br />

These works almost certainly predate by centuries the river channel work by Sir<br />

Richard Weston around Stoke and Sutton Place in the early 17 th century (Richard<br />

Savage, Mary Alexander). 10 th /11 th century ‘canalisations’ have been reported<br />

from Oxfordshire (Judie English).<br />

iv) Merton Priory merits further consideration (Mary Alexander, Dennis Turner).<br />

5. Castles and moated sites<br />

i) Differences of purpose were as important as differences of status; the debate was<br />

more complex than a simple differentiation between “castles” and “high status<br />

fortified houses”. See Charles Coulson’s works, including “Castles in Medieval<br />

Society: Fortresses in England, France, and Ireland in the Central Middle Ages”<br />

(Dennis Turner, Nigel Saul).<br />

ii) Abinger was a proto-typical small motte castle but there were not many of these in<br />

<strong>Surrey</strong> (Dennis Turner).<br />

iii) Reference was made to the recent Time Team programme on Waynflete’s Tower<br />

and the destroyed portions of Esher ‘castle’, and the links to Farnham and<br />

Tattershall (Dennis Turner).<br />

iv) Of the major castles in <strong>Surrey</strong>, that at Reigate merited a good deal of investigation<br />

(Nigel Saul).<br />

v) In general, our understanding of the development of the various <strong>Surrey</strong> castles<br />

was inadequate. Programmes of work integrating above and below-ground<br />

5

artefacts into describing the life of the people of the time as the castle sites<br />

developed and changed would be very valuable (Peter Youngs).<br />

6. <strong>Surrey</strong> industries<br />

Much work needs to be carried out on the precursors of some of the post-1500<br />

industries, as well as on those industries which seem to have been concentrated in the<br />

medieval period.<br />

i) Potteries and tileries. While Kingston and Cheam wares are common on central<br />

London sites, is there any record of Limpsfield or Earlswood wares being found in<br />

London (Dennis Turner)?<br />

ii) Wool. Sheep breeding is documented around Epsom on the Downs and in East<br />

<strong>Surrey</strong> at an early time, but the wool processing industries seem to have grown up<br />

in the medieval period in the West <strong>Surrey</strong> towns (especially Guildford and<br />

Godalming, with a fulling mill in Guildford by at least the mid 13 th century). What<br />

are the reasons for this (noting that in Kent wool shorn from sheep kept on<br />

Romney Marsh was woven into cloth in the Wealden villages inland)? A search of<br />

the Winchester Pipe Rolls might provide some answers for the West <strong>Surrey</strong><br />

towns. Sheep at Epsom may have been kept for meat for the London market.<br />

(Dennis Turner, Nigel Saul, Mary Alexander, David Bird).<br />

iii) Iron. There appears to be significant iron production in the low Weald around<br />

Horley and Burstow in the late medieval period, with hints that this used a<br />

different technology to that being practised in iron processing in towns such as<br />

Reigate. This could be a good research project (Jeremy Hodgkinson).<br />

iv) Glass, Building Stone, Fullers Earth No discussion at this <strong>seminar</strong>.<br />

7. Developer-funded archaeology and the Society<br />

It is inevitable that most excavation work in the future will be carried out by<br />

‘archaeological contractors’, funded under PPG16 procedures by developers. A key<br />

task falling to the Society and to academia will be the synthesis of all these results, as<br />

archaeological contractors have no funding for this (Judie English). A key part of the<br />

present process is to provide through the <strong>Surrey</strong> Archaeological Research Framework<br />

the means whereby <strong>Surrey</strong>’s ‘heritage planners’ and archaeological contractors, often<br />

from outside the <strong>County</strong>, can be informed as to the potential of each development site<br />

(Mary Alexander, David Bird). But this is not enough; we cannot rely on the<br />

professionals alone. The Society needs to gear up and enthuse a new generation of<br />

active ‘volunteers’, to talk to archaeological contractors and developers, to carry out<br />

watching briefs and to build public enthusiasm for archaeology (Andrew Norris). And<br />

the Society should also run its own research programmes (David Bird), especially as<br />

not all problems arise in areas where there will be any developer-funded work at all.<br />

There are technical difficulties with the PPG16 process, particularly around the<br />

narrow definition of ‘areas at risk’ and the present form of ‘evaluation’ trenches,<br />

which are both machine dug and too small to pick up many forms of medieval<br />

occupation. Similarly watching briefs are unlikely to recognise the ephemeral nature<br />

of much medieval occupation, especially where rubbish was swept from medieval<br />

houses into middens and taken from there to be spread on the fields (Dennis Turner,<br />

David Bird).<br />

6

8. Documentary sources.<br />

The main sources of material are the manorial records, many of which are now<br />

indexed on-line (with quite a lot of new manorial records found in the archives at<br />

Oxford, Cambridge and Eton). Some have been transcribed (e.g. by the <strong>Surrey</strong> Record<br />

Society) but in general it is best to go back to the original sources. The records of<br />

Chertsey Abbey are particularly important for NW <strong>Surrey</strong> (Nigel Saul). Are these<br />

easy to read (Pauline Hulse)? Best to learn first how to read documents of the 16 th to<br />

18 th centuries; the recently proposed FE course by <strong>Surrey</strong> University on this is not<br />

going ahead but the Society will consider arranging a similar course (Audrey Monk).<br />

The earliest manorial records are from the mid 13 th century and are difficult to read<br />

without first studying the later periods (Nigel Saul)<br />

Peter Youngs and David Bird closed the meeting by reiterating the request for<br />

thoughts, which could be sent by letter, e-mail or any other medium to any member of<br />

the Steering Group.<br />

RWS<br />

16.2.06<br />

7

<strong>Surrey</strong> Archaeological Research Framework<br />

Seminar 4: Summary Notes<br />

<strong>Surrey</strong> after about 1500: buildings, parks and gardens, agriculture<br />

21 February 2006<br />

Peter Youngs (Chairman of the Seminar) introduced the fourth <strong>seminar</strong>, which like<br />

the earlier <strong>seminar</strong>s was part of the process intended to construct a framework for<br />

future research. The earlier <strong>seminar</strong>s had been based primarily on chronological<br />

periods; those for the post 1500 period would be based primarily on themes.<br />

Documentary evidence for these more recent periods was much more plentiful,<br />

increasingly in English and easier (though often not easy) to read. Dendrochronology<br />

had been refined over recent years and become a key tool in dating the development<br />

of medieval and post-medieval houses and barns; our knowledge of the period under<br />

consideration this evening was based on a synthesis of archaeology, documentary<br />

sources and scientific techniques such as dendro-dating. The <strong>Surrey</strong> dendro project<br />

was also important to the <strong>SARF</strong> process in demonstrating the articulation of a project<br />

with clear aims, the raising of the necessary funding and the carrying out of the<br />

project to meet the original aims (while formulating new questions arising from the<br />

findings). Notes by Rod Wild about the Dendro Project and by Brenda Lewis about<br />

the Historic Parks and Gardens Project had been circulated to all participants before<br />

the <strong>seminar</strong>.<br />

Buildings and Dendrochronology<br />

Presentation by Rod Wild<br />

It would be assumed that <strong>seminar</strong> members had knowledge of both the basic sequence<br />

of building types in <strong>Surrey</strong> and of dendrochronology as a technique.<br />

The study of buildings helps to us to understand society in a wider context, including<br />

such matters as crafts, styles of living, privacy, how the family and their associates<br />

‘fitted’ into the house, classes of occupants, economics and the town/country divide<br />

(which was very pronounced in this period). Dendrochronology enables calibration<br />

(and sometimes amendment) of what was otherwise dating based on stylistic<br />

evolution. In many cases of oak buildings in <strong>Surrey</strong> it was now possible to date felling<br />

of the timbers (and as oak is used in its ‘green’ state, by implication, the date of<br />

construction of a building or amendment) to a precise year. This had produced many<br />

new insights (e.g. the replacement of open halls by smoke-bays seems to have<br />

occurred all over the county within a couple of years of the Dissolution of the<br />

Monasteries, although the reasons for this were still conjectural). Such precise dating<br />

of the construction of houses and additions enabled correlation with events known<br />

from, or to be found in, historical sources, such as the marriages and deaths of<br />

particular individuals who had owned the houses. The intensive recent studies had<br />

shown that in much of <strong>Surrey</strong> oak woods were being managed by the 15 th century,<br />

with the regular cutting-back of lower branches on a 15 or so year cycle – although<br />

oaks from the High Weald did not show this pattern. It was becoming clear that most<br />

timber was used close to where it was felled. But it was now possible to show that<br />

some houses (sometimes quite widely separated and of different social classes) were<br />

built from timbers cut from the same wood in the same year – this clearly had<br />

implications for our understanding of how woods were managed (e.g. in such cases,<br />

1

was an entire wood cleared, whether then replanted or the land used for agriculture?)<br />

and the wider societal and economic effects (how was the demand for new houses<br />

inter-related with the supply of suitable timbers?). The precise dating of so many<br />

early houses across <strong>Surrey</strong> seemed to show periods of much house building<br />

interspersed with periods of little building. And some work had been carried out on<br />

barns and churches (in the latter case demonstrating that published Church guides are<br />

often inaccurate).<br />

Rod showed a number of slides illustrating houses dated in the <strong>Surrey</strong> Dendrochronology<br />

Project, from the earliest at 1254 AD through to the early 17 th century.<br />

The styles of building in South West <strong>Surrey</strong> (around Godalming) were somewhat<br />

different from those in the centre of the <strong>County</strong>. Very little was known about the<br />

detail of medieval building in North East <strong>Surrey</strong>, as few medieval houses survived in<br />

the Greater London area.<br />

In summary, dendrochronology was able to calibrate all sorts of medieval and postmedieval<br />

studies.<br />

Discussion<br />

• Overall around 30% of old houses in <strong>Surrey</strong> proposed for dendro-dating were not<br />

suitable (generally because of species of tree or lack of adequate timbers); of the<br />

remainder some 75% produced good dates (either to a single year or to a short<br />

span of years). The overall statistics were however not necessarily a good<br />

representation. In the South Mole valley ‘cluster’ only about 10% of early houses<br />

were not suitable and of the remainder at least 90% gave good dates. In Horsley<br />

and Clandon many houses had a high proportion of elm, rather than oak, and the<br />

proportion of houses dated successfully was much lower. In Shere the oaks<br />

seemed to have grown particularly quickly and the sequences here could not be<br />

matched to more slowly growing oaks (this was probably a consequence of the<br />

geology, not of differences in arboricultural technique).<br />

• Studies of the geographical spread of techniques, informed now by the detailed<br />

dendro dates, are at an early stage. There appear to be similarities between East<br />

<strong>Surrey</strong> and Kent and between West <strong>Surrey</strong> and Hampshire, but even in these<br />

localised areas specific building features and techniques seem to migrate at<br />

different times! Clapboarding and tile-hanging are both later methods of covering<br />

a building, the core of which may be much earlier.<br />

• The dendro project has shown that in a number of cases houses and large barns<br />

were constructed at the same time, sometimes to replace earlier buildings and<br />

sometimes on sites not previously used. What are the implications of this on a<br />

case-by-case basis? Were some of these agricultural units built from the outset for<br />

rent?<br />

• It is uncertain whether agricultural buildings tended to be built ‘more<br />

conservatively’ than houses of the same date (as is sometimes claimed); it seems<br />

inherently unlikely that a carpenter would use different traditions in building a<br />

barn contemporary with a house, but of course the house is likely to have more<br />

domestic features included within it from the outset. There are many documented<br />

examples over the years of barns becoming houses and vice versa, and indeed<br />

cases where a building has been a house, then a barn and then a house again<br />

(sometimes in a very different format – whether in its later incarnation it is home<br />

2

to a single family and their servants or split up into multiple dwellings). Boxframe<br />

construction of large rectangular buildings is well suited to many forms of<br />

adaptation of use over time.<br />

• There are indications that ‘traditional’ methods that might otherwise be regarded<br />

as somewhat archaic might be used for the construction of church roofs (e.g. king<br />

post construction of some surviving church roofs has been dendro dated to periods<br />

after this technique had apparently largely gone out of use in houses).<br />

• Box-framed buildings on sleeper beams (whether Romano-British or medieval)<br />

often leave very little archaeological trace in the ground. Even demolished wings<br />

of buildings that are otherwise standing can be impossible to trace in an<br />

excavation, even though well attested by documentary sources. This is a major<br />

problem in tracing ancillary buildings that may once have stood around a house<br />

that has survived to the present day.<br />

• Precise dendro dating of a building helps researchers focus in more rapidly on the<br />

relevant documentary sources (i.e. the Court Rolls for the right period rather than<br />

40 or 50 years off, based on traditional stylistic dating).<br />

• Many Court Rolls have already been transcribed. Researchers were advised to<br />

check for such transcriptions and read any secondary sources before commencing<br />

a time-consuming study of the original sources. Such background of refreshing the<br />

collective memory would provide a sound basis for the next stage of research –<br />

while of course maintaining a critical approach to all such material.<br />

• How long did it take to build a domestic timber-framed house? Dendro studies<br />

and early contracts (see for the latter L. F. Salzman, Building in England down to<br />

1540 (Oxford, 1952) referred to in A. Quiney, Town Houses of Medieval Britain<br />

(Yale University Press, 2003)) seemed to show that many houses were built in a<br />

single season, although some other documentary sources seemed to record on<br />

occasion a building period of up to 4 years. Most timber-framed domestic<br />

buildings were built by carpenters, not by householders.<br />

• The loss of medieval buildings in North East <strong>Surrey</strong> was not a recent<br />

phenomenon. Studies of Hearth Tax returns showed that NE <strong>Surrey</strong> had lost most<br />

of its medieval buildings by the 17 th century. The Hearth Tax returns for the rest<br />

of <strong>Surrey</strong> had been mapped but the results not yet published.<br />

• The Villages Project group would be re-issuing some of its guidance <strong>notes</strong> where<br />

these were now out of stock and holding a series of <strong>seminar</strong>s (the next on 20 May<br />

when Annabelle Hughes will be talking about early documentation). Clearly the<br />

recent advances in understanding of the dating of buildings from the dendro<br />

studies would have relevance to the Villages Project, but (as recorded above)<br />

work was still in progress on aligning building features with dendro dates in each<br />

locality.<br />

• Much of the early archive material relating to estates in <strong>Surrey</strong> is held outside the<br />

county (a point also made in the preceding <strong>seminar</strong>).<br />

• Brick was used at Waynflete’s Tower in Esher and at Farnham Castle<br />

exceptionally early. It starts being used in chimneys more widely from about 1550<br />

and then comes into more general use about 1600. Tiles were widely in use from<br />

the medieval period. Where were the bricks and tiles made? Probably in clamps<br />

close to where the buildings were constructed. References to large numbers of<br />

bricks being made in the 1550s for Woking Palace at Sutton and Clandon<br />

Common. Where are the clay-pits and the remains of the clamps? Was transport<br />

by cart or by barge down the Wey?<br />

3

• Still a need for a study of the use and distribution of the various types of local<br />

building stone, both in the medieval period and in the years after 1500.<br />

Gardens<br />

Brenda Lewis confirmed that gardens were dated primarily on stylistic grounds,<br />

although dating by documentary sources was preferred where these were available.<br />

She noted that the later fashion for ‘landscape styling’ had largely destroyed any<br />

medieval gardens, including their mottes and mounds. She also noted that in the<br />

earlier periods gardens were often detached from the residential buildings, forming a<br />

separate feature in the wider agricultural landscape around them.<br />

Points made in discussion:<br />

• Gardens did not seem to become an integral part of a “house” until the 16 th<br />

century.<br />

• Walled gardens went back to the monasteries and were present in domestic<br />

settings by the later Tudor period.<br />

• While garden features were in principle detectable in archaeological excavations,<br />

the traces of many such features were very ephemeral and in practice little<br />

evidence of gardens was found by way of excavation (paths and hard landscaping<br />

sometimes survived, but by their nature gardens were frequently dug over and<br />

remodelled). As mentioned above, it was often very difficult to detect where even<br />

the buildings had stood if they had been based on sleeper beams. By their nature<br />

traditional ‘cottage gardens’ were even more ephemeral than more formal<br />

gardens. Dendro dating had not yet found much application in garden studies.<br />

Agriculture in <strong>Surrey</strong> after 1500<br />

From the chair, Peter Youngs posed the question as to what we know about the<br />

agriculture of <strong>Surrey</strong> from 1500 up to modern times, and in particular how<br />

agricultural practices in the county had changed over that period. David Bird asked<br />

what studies had already been published into this. From the lack of response it seems<br />

there may be no modern synthesis of the development of agriculture in <strong>Surrey</strong> since<br />

1500. Points made in discussion included:<br />

• There is a vast mass of material on particular aspects of agriculture in the county,<br />

much of it published in the form of articles spread over many journals. There are<br />