Responsible Relic Recovery Of Cherokee War Artifacts - Garrett

Responsible Relic Recovery Of Cherokee War Artifacts - Garrett

Responsible Relic Recovery Of Cherokee War Artifacts - Garrett

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>Responsible</strong> <strong>Relic</strong> <strong>Recovery</strong><br />

<strong>Of</strong> <strong>Cherokee</strong> <strong>War</strong> <strong>Artifacts</strong><br />

Story by Stephen L. Moore • Photos by Brian McKenzie<br />

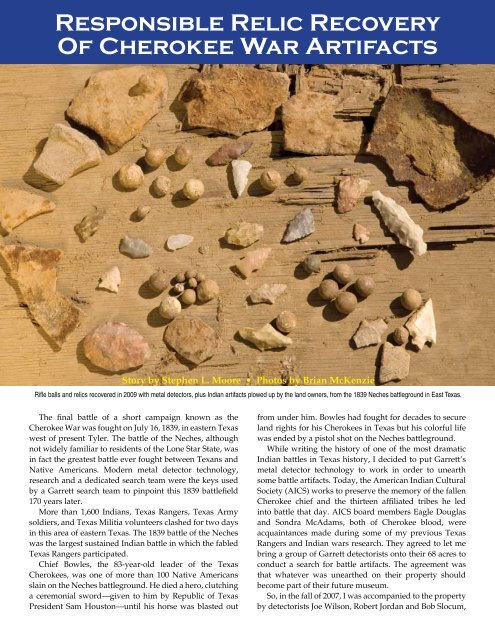

Rifle balls and relics recovered in 2009 with metal detectors, plus Indian artifacts plowed up by the land owners, from the 1839 Neches battleground in East Texas.<br />

The final battle of a short campaign known as the<br />

<strong>Cherokee</strong> <strong>War</strong> was fought on July 16, 1839, in eastern Texas<br />

west of present Tyler. The battle of the Neches, although<br />

not widely familiar to residents of the Lone Star State, was<br />

in fact the greatest battle ever fought between Texans and<br />

Native Americans. Modern metal detector technology,<br />

research and a dedicated search team were the keys used<br />

by a <strong>Garrett</strong> search team to pinpoint this 1839 battlefield<br />

170 years later.<br />

More than 1,600 Indians, Texas Rangers, Texas Army<br />

soldiers, and Texas Militia volunteers clashed for two days<br />

in this area of eastern Texas. The 1839 battle of the Neches<br />

was the largest sustained Indian battle in which the fabled<br />

Texas Rangers participated.<br />

Chief Bowles, the 83-year-old leader of the Texas<br />

<strong>Cherokee</strong>s, was one of more than 100 Native Americans<br />

slain on the Neches battleground. He died a hero, clutching<br />

a ceremonial sword—given to him by Republic of Texas<br />

President Sam Houston—until his horse was blasted out<br />

from under him. Bowles had fought for decades to secure<br />

land rights for his <strong>Cherokee</strong>s in Texas but his colorful life<br />

was ended by a pistol shot on the Neches battleground.<br />

While writing the history of one of the most dramatic<br />

Indian battles in Texas history, I decided to put <strong>Garrett</strong>’s<br />

metal detector technology to work in order to unearth<br />

some battle artifacts. Today, the American Indian Cultural<br />

Society (AICS) works to preserve the memory of the fallen<br />

<strong>Cherokee</strong> chief and the thirteen affiliated tribes he led<br />

into battle that day. AICS board members Eagle Douglas<br />

and Sondra McAdams, both of <strong>Cherokee</strong> blood, were<br />

acquaintances made during some of my previous Texas<br />

Rangers and Indian wars research. They agreed to let me<br />

bring a group of <strong>Garrett</strong> detectorists onto their 68 acres to<br />

conduct a search for battle artifacts. The agreement was<br />

that whatever was unearthed on their property should<br />

become part of their future museum.<br />

So, in the fall of 2007, I was accompanied to the property<br />

by detectorists Joe Wilson, Robert Jordan and Bob Slocum,<br />

Story by Stephen L. Moore • Photos by Brian McKenzie

plus Vaughan <strong>Garrett</strong> and Brian McKenzie to document any<br />

discoveries with video and still photography. We brought<br />

along a number of <strong>Garrett</strong>’s most advanced metal detectors:<br />

the GTI 2500, GTI 1500, GTP 1350 and an ACE 250. We worked<br />

into the late afternoon, doing reconnaissance scanning of<br />

the areas surrounding a field containing Bowles’ marker.<br />

We also ventured into the deep woods, working through<br />

deep creek beds and following them out toward the Neches<br />

River bottomlands. By the end of a full day’s hunt, we had<br />

collected shotgun shells, modern bullets and various rural<br />

farmland metallic junk. Joe even dug up some World <strong>War</strong><br />

I-era blunts, bullets somewhat similar to those used decades<br />

before during the Civil <strong>War</strong>.<br />

The artifacts we sought from the 1830s period had proven<br />

to be elusive. Several weeks later, I returned to search the<br />

AICS property again with Joe, Robert and Keith Wills. We<br />

searched over some of the likely areas near the creek and<br />

all around the large hilltop where a Delaware Indian village<br />

was said to have been. Once again, we found modern bullets,<br />

some coins, an old watch and miscellaneous metallic junk.<br />

The four of us then made a reconnaissance line and scouted<br />

with our detectors back toward the road, moving up another<br />

small hill and into the forest again before finally reaching the<br />

property’s barbed wire fence line.<br />

Keith and I agreed that we must be searching on the tail<br />

end of the battlefield. Obviously, there were some artifacts in<br />

this area at one time but even modern souvenir hunters and<br />

previous timber-cutting operations would not have removed<br />

all traces of such a heavily-contested battle. The next step<br />

was to research the earliest information on the Neches<br />

battle more thoroughly while attempting to gain permission<br />

from the adjacent landowners to conduct a survey on their<br />

property.<br />

(Left) In his "Battle of the Neches"<br />

painting from 1967, artist Donald M.<br />

Yena captured the closing moments of<br />

the 1839 battle. Chief Bowles (below),<br />

with his ceremonial sword upraised,<br />

is shot in the back after his horse has<br />

been crippled with numerous rifle ball<br />

shots. Painting used by permission of<br />

Frank Horlock and Michael Krueger.<br />

Bowles illustration courtesy of Texas<br />

State Library & Archives Commission.<br />

Since our first efforts to recover relics on the AICS land<br />

had been fruitless, I decided to forget about where the<br />

Bowles marker stands and where the battle was assumed<br />

to have been concentrated. It was time to dig back into the<br />

earliest accounts of the battle and to visit with others who<br />

might have some useful information.<br />

A 1920s article by Dr. Albert Woldert became my<br />

primary focus, particularly several detailed maps based on<br />

his research. The spot where he had labeled Chief Bowles<br />

to have died was on the opposite side of a particular<br />

creek than where I had expected it to be shown. Modern<br />

graphics programs allowed me to scan in this map and<br />

overlay it on a satellite image of the area and on a scanned<br />

page from a detailed Texas road map of the county. The<br />

new composited picture convinced me that we would<br />

find the main battle area somewhat south of the area<br />

owned by AICS. This map work convinced me that the<br />

old Delaware village was not exactly on the hilltop where<br />

the tribal stones have been placed. Could there be another<br />

significant hilltop within 300 yards to the southwest?<br />

Fortunately, landowners Thurman and Alice Jett<br />

were open to this historical quest and it was with great<br />

excitement that I led another group of detectorists to hunt<br />

their land in early 2009. Mr. Jett even mentioned that his<br />

family had plowed up bits of old pottery for years and<br />

had often found arrowheads on their property. It was all<br />

coming together like lost pieces to a puzzle. As our <strong>Garrett</strong><br />

search team first drove onto the property to meet the Jetts,<br />

there was the hill I had hoped to find! It rose up out of the<br />

heavy timber from the south, reached its peak right where<br />

the home sits and then fell off sharply on the north and<br />

east sides. Behind the Jett’s home is a steep hill that opens<br />

onto a vast farmland prairie containing a small creek.

The location we had reached on the Jett property had<br />

all of the necessary elements to make Woldert’s notes<br />

fit. We just needed to find evidence that would prove it<br />

beyond a doubt. For this recon mission, my companions<br />

were Joe Wilson, his uncle Stan May, Robert Jordan and<br />

Brian McKenzie, the latter doubling as both the excursion’s<br />

photographer and detectorist. We fanned out and began<br />

searching the vast prairie behind the Jett home, working<br />

our way along a small spring-fed pond back toward the<br />

Neches River bottomlands. Most of our efforts throughout<br />

the day were on the open prairie, in the heavy woods to the<br />

north of the field or in the bottomlands. As on the adjoining<br />

68 acres of AICS lands, we dug some metal junk and plenty<br />

of modern projectiles of all calibers.<br />

It was such a vast area of land for five detectors to cover<br />

that it was mid-afternoon before we finally tasted success.<br />

Robert Jordan, using a GTP 1350, had a solid hit in the<br />

forest that read as a 7 on his Target ID scale. With the aid<br />

of his trusty Pro-Pointer, he retrieved a genuine nineteenthcentury<br />

lead musket ball from a depth of four inches.<br />

This proved to be our only definite relic from the<br />

Neches battle this day but it was enough to encourage me<br />

to begin thinking about a return. Dr. Gregg Dimmick, who<br />

has long used metal detectors in his archaeological research<br />

on the Mexican Army’s retreat after the 1836 battle of San<br />

Jacinto, encouraged me to send the size, weight and photos<br />

of this musket ball to Doug Scott. Doug is a ballistics expert<br />

famous for his work on artifacts from the Little Bighorn<br />

battle. He quickly confirmed that it was a standard .69<br />

caliber ball which certainly would have been used in the<br />

1830s.<br />

Our search team returned to the Jett farm in March<br />

2009, with their permission to conduct another hunt. For<br />

this foray, we recruited additional volunteers from the<br />

Lone Star Treasure Hunting Club of Dallas. In addition to<br />

Robert, myself, Brian McKenzie, Joe Wilson, and Stan May,<br />

seven others were on hand to put their skills to the test:<br />

Paul Wilson, Mike Skinner, Rusty Curry, Bob Bruce, Matt<br />

Bruce, Robert Jeffrey, and Dave Totzke.<br />

Shortly after 11:00 a.m., Paul was the first to find a<br />

.69-caliber musket ball with his GTI 1500. Within minutes,<br />

Paul recovered another ball and Bob Bruce soon followed<br />

suit. By the time I emerged from a deep thicket, I found<br />

that Bob, Paul, Matt Bruce, Robert Jordan and Dave Totzke<br />

had each recovered 1830s musket balls. Before I could<br />

reach the middle of the field, Dave announced, “I’ve got<br />

another one!”<br />

He was curiously spinning a small metal orb in his<br />

fingers. “This must be from a pistol,” he mused. “It’s<br />

much smaller than the musket balls we’re finding.”<br />

Dave made another probe of his excavation area with his<br />

Pro-Pointer. It suddenly rattled and hummed with the<br />

distinctive announcement of another metallic target. What<br />

he recovered was even more exciting–three more smaller<br />

balls, each about twice the size of a child’s BB.<br />

“Do you know what this is?” he asked. “It’s a buck and<br />

ball load!”<br />

The pinpointer had enabled Dave to find the much<br />

smaller buckshot which he most likely would have missed.<br />

Such small targets easily blend in with the dirt. The prior<br />

First find! Robert Jordan holds<br />

the first .69-caliber lead rifle ball<br />

(seen above) found by the <strong>Garrett</strong><br />

search team on the property<br />

where <strong>Cherokee</strong> Indians and<br />

the Texas Rangers fought their<br />

greatest battle.<br />

Neches battleground search<br />

team on March 4, 2009. (Left<br />

to right, standing): Stan May,<br />

Mike Skinner, Paul Wilson, Dave<br />

Totzke, Robert Jeffrey, Robert<br />

Jordan, Steve Moore, Rusty<br />

Curry and Joe Wilson. (Kneeling,<br />

left to right): Matt Bruce and<br />

Bob Bruce.

(Left) This three-piece buck<br />

and ball load was recovered<br />

by Dave Totzke. The smaller<br />

buckshot balls measure .32<br />

inches in diameter.<br />

(Below) The author recovers<br />

a flattened .69 caliber rifle or<br />

musket ball.<br />

recovery of a nice, albeit smaller, musket ball might have<br />

satisfied a novice searcher that he or she had found the metal<br />

detector’s announced target. Before the day was out, Dave<br />

would find another similar buck and ball load with the aid<br />

of his Pro-Pointer.<br />

I have read Charles <strong>Garrett</strong>’s words and have heard him<br />

utter the phrase many times: “You can find treasure even<br />

in your own backyard!” In this case, we had found historic<br />

relics right in the Jetts’ own front yard!<br />

These musket balls and buck and ball loads were likely<br />

dropped by Texans who were firing at Indians in the creek<br />

bed below them. Some of the discovered shots had perhaps<br />

been fired back up at the Texans by the <strong>Cherokee</strong>s. Our<br />

team continued working the field during the next hour and<br />

most recovered at least a couple of musket balls. In addition,<br />

Dave, Paul, Joe Wilson, Robert Jordan, Rusty Curry and<br />

Mike Skinner each managed to recover pieces of an old iron<br />

cooking pot that appear to have been shattered many years<br />

ago by someone plowing the land.<br />

Following a quick lunch break, I struck out across the<br />

top of the hill in front of the Jett home toward the area where<br />

Robert had found the lone rifle ball weeks before. I topped<br />

the little prairie’s highest elevation and had just started<br />

down the back slope when my GTI 2500 sang out with a<br />

solid hit. It was right on the 7 mark on the scale, just where<br />

the other balls had been registering.<br />

Using my spade, I popped a six-inch-deep plug and<br />

began probing the recovery hole with my Pro-Pointer. In<br />

short order, it began vibrating and audibly rattling with the<br />

sweet sound of a solid target. From the soft soil, I retrieved<br />

a somewhat flattened hard piece of lead that was solid and<br />

heavy. Brushing it off, I quickly realized it to be a musket ball<br />

that had mushroomed on impact. It was a sobering thought<br />

These battlefield relics were dug on the main July 16 battle site. (Left to right) A<br />

1.1 oz. .69 caliber musket ball that has flattened upon impact; an intact .69 caliber<br />

musket ball which was likely never fired (notice the tip of the sprue that was not<br />

properly clipped off); a .42 caliber ball which also dropped (which appears to have<br />

not been trimmed after molding); and a properly formed .69 caliber musket ball.<br />

indeed to realize that this little pancaked treasure had likely<br />

ended someone’s life in 1839.<br />

Paul Wilson and Robert Jeffrey each soon discovered<br />

similarly flattened rifle balls while Stan found another intact<br />

ball that had obviously missed its mark. This area would<br />

prove to be the initial skirmish line where Texan scouts had<br />

been taken under fire by the <strong>Cherokee</strong>s in July 1839. A few of<br />

our recoveries were buck and ball loads in which the larger<br />

ball still possessed its little “nub” or the tab that might have<br />

been snipped off prior to packing a load.<br />

Gregg Dimmick, ballistics expert Doug Scott and Byron<br />

Johnson, Executive Director of the Texas Ranger Hall of<br />

Fame and Museum in Waco, all helped confirm that the<br />

.69-caliber and other smaller balls we had found were<br />

certainly available in 1839. With the help of Donaly Brice of<br />

the Texas State Archives, I later tracked down a July 1839<br />

document confirming that the Texas Rangers had indeed<br />

been supplied with 50 pounds of buckshot prior to the battle<br />

to use in buck and ball loads. Chief Bowles, in fact, is known<br />

to have been shot in the back by a buck and ball shot.<br />

The Jett family was kind enough to let us make an<br />

additional search of their land on April 1, and we were again<br />

able to further define the battle areas. My team this day<br />

included detectorists Mike Skinner, Robert Jordan, Richey<br />

Davidson, Brenda Davidson, Ray Wathar and Ronnie Morris,<br />

plus Vaughan <strong>Garrett</strong> and Brian McKenzie to document the<br />

recoveries with video and photos.<br />

Our search efforts were concentrated in the lower fields<br />

this day below the upper hill where many of the relics had<br />

been previously unearthed. A number of additional rifle<br />

balls were discovered within 30 yards of the twisting creek<br />

where the <strong>Cherokee</strong>s had been positioned during the Neches<br />

battle. Most of the lead balls this day were of the .69 caliber<br />

size and a few stray shots were even found on the far side of<br />

the creek, away from the main battle area.<br />

From the two concentrated areas of relic recoveries<br />

previously encountered and this hot spot near the creek,<br />

we could pretty clearly visualize the 1839 Neches battle.<br />

The terrain, the slope and the creek bed below the hill fit the<br />

various descriptions of the battlefield that were penned in<br />

1839 by some of the Texans. Beyond the creek bed, a heavy

(Above) These helping hands who helped hand back history are seen here displaying the musket balls,<br />

buckshot and bullet button found on the Neches battlefield.<br />

thicket eventually opens into the small clearing where the<br />

Chief Bowles monument now stands. We had discovered<br />

rifle balls all the way up to the edge of Mr. Jett’s property<br />

leading generally from the most heated area toward the<br />

Bowles marker—which was located perhaps 200 yards<br />

beyond this area of the creek through heavy forest.<br />

Our metal detectors had helped solve the mystery of<br />

where Bowles’ <strong>Cherokee</strong>s had made their last stand 170<br />

years ago. My thoughts now turned to preserving these relics<br />

so that future generations can benefit from the knowledge<br />

of this history that we had unearthed. From the start, I had<br />

promised Eagle Douglas and his American Indian Cultural<br />

Society that I would donate significant artifacts to his group<br />

to help promote their efforts. The Jett family kindly donated<br />

arrowheads and Native American pottery found on the<br />

battlefield for the donation cases.<br />

(Left) Ray Wathar digs into<br />

a weed patch to unearth another<br />

rifle ball near the creek.<br />

(Right) Detail photo of a<br />

.69-caliber ball and a 19th<br />

century bullet button found<br />

on the battlefield.<br />

This article is condensed from <strong>Garrett</strong> detectorist<br />

Stephen L. Moore’s new book called Last Stand of the<br />

Texas <strong>Cherokee</strong>s. In addition to an extended version<br />

of the relic recovery, Last Stand covers the life of Chief<br />

Bowles, his tribe’s land struggles and the subsequent<br />

frontier battles of the <strong>Cherokee</strong> <strong>War</strong>.<br />

In addition, it became clear to me that it would be<br />

proper to offer historical relics to both sides. The Texas<br />

Ranger Museum and Hall of Fame in Waco seemed like the<br />

natural fit, as six companies of early Rangers fought in this<br />

East Texas conflict. Both the Texas Rangers Museum and the<br />

AICS board members were thrilled to receive donation cases<br />

of our recovered relics. We know that these two groups will<br />

share the knowledge of these relics with any who possess an<br />

interest in this history.<br />

Many decades have passed since that last stand of the<br />

Texas <strong>Cherokee</strong>s and their affiliated tribes. Thanks to the<br />

sophisticated electronic circuitry of some modern metal<br />

detectors, we were able to brush aside the legends and<br />

precisely pinpoint the spot where Republic of Texas-era<br />

colonists had forever dimmed the light of hope held by the<br />

<strong>Cherokee</strong>s to peacefully settle on Texas soil.

Neches battleground scenes. (Clockwise from above.) Vaughan <strong>Garrett</strong> captures the look of<br />

genuine excitement as Robert Jordan finds a musket ball. Matt Bruce holds up another ball<br />

found with his ACE 250 in the upper field. The state of Texas erected this Centennial Marker<br />

in 1936 to mark the spot where Chief Bowles died in battle. Another of the <strong>Garrett</strong> search<br />

groups (l-r): Richey Davidson, Ronnie Morris, Brenda Davidson, Ray Wathar, Mike Skinner<br />

and Steve Moore.<br />

(Left to right): Author presents an artifact case to Texas Ranger officers Lieut. George Turner<br />

of Company F, Capt. Al Alexis of Company B, and Capt. Kirby Dendy of Company F, Waco.