Download The Changeling Education Pack - English Touring Theatre

Download The Changeling Education Pack - English Touring Theatre

Download The Changeling Education Pack - English Touring Theatre

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

25 Short Street<br />

London<br />

SE1 8LJ<br />

T: 020 7450 1982<br />

E: education@ett.org.uk<br />

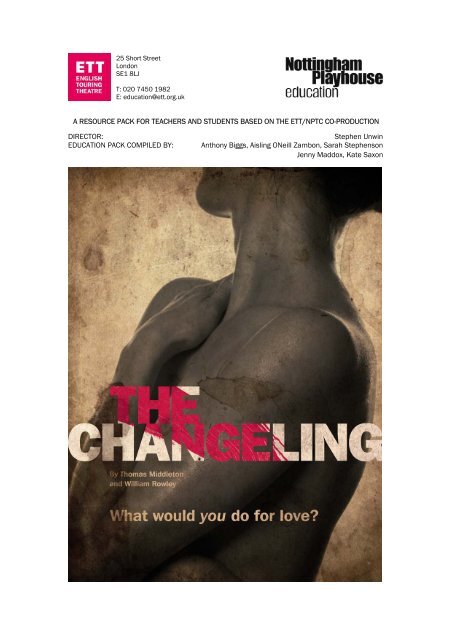

A RESOURCE PACK FOR TEACHERS AND STUDENTS BASED ON THE ETT/NPTC CO-PRODUCTION<br />

DIRECTOR:<br />

EDUCATION PACK COMPILED BY:<br />

Stephen Unwin<br />

Anthony Biggs, Aisling ONeill Zambon, Sarah Stephenson<br />

Jenny Maddox, Kate Saxon

CONTENTS<br />

<strong>English</strong> <strong>Touring</strong> <strong>The</strong>atre 3<br />

Introduction to this pack 3<br />

Cast and Creative team 4<br />

Stephen Unwin on <strong>The</strong> <strong>Changeling</strong> 5<br />

Synopsis of the play 6<br />

Thomas Middleton 7<br />

Background to <strong>The</strong> <strong>Changeling</strong> 8<br />

Jacobean Drama 9<br />

Interview with Stephen Unwin – Director 10<br />

Madness & Sanity in the 17 th Century 11<br />

Rehearsing <strong>The</strong> <strong>Changeling</strong> 12<br />

Interview with Mark Bouman - Costume Designer 15<br />

Interview with Paul Wills – Set Designer 17<br />

Interview with Ben Ormerod - Lighting Designer 18<br />

Interview with Timandra Dyer – Production Manager 19<br />

<strong>The</strong> Role of Women in 17 th Century England 20<br />

Women & Sexuality in <strong>The</strong> <strong>Changeling</strong> 22<br />

Assistant Director’s Essay 23<br />

Cast interviews 24<br />

Post-show questions for discussion 28<br />

Exercises 28<br />

Further reading & contact details 32<br />

2

CREATIVE POLICY<br />

ETT is England’s leading touring theatre company.<br />

ETT was founded in 1993. Since then we have toured over forty productions of both European classics and<br />

new plays, and have gained a reputation for work that is carefully conceived, crystal clear and respects the<br />

intelligence of its audience.<br />

At the heart of everything we do is the passionately held belief that quality theatre does not have to be elitist,<br />

and that people everywhere expect and deserve the best.<br />

We have won eighteen major awards, taken fourteen productions into London, and worked with some of the<br />

most talented and respected artists in the country.<br />

We want our work to reflect the diversity of the cities and towns we play in. We have a deep commitment to<br />

creative learning and provide workshops, master-classes, seminars and talks to people of all ages throughout<br />

the country. We provide a wide range of accessible performances.<br />

ABOUT THE COMPANY<br />

ETT was founded by Stephen Unwin in 1993 with the aim of creating outstanding theatre and touring it to the<br />

widest possible audience.<br />

We have always had a strong commitment to Shakespeare, and our award-winning productions include<br />

Hamlet, As You Like It, Henry IV Parts One and Two, King Lear and Hamlet again.<br />

A second line of work has been on Ibsen, with hailed productions of <strong>The</strong> Doll’s House, Hedda Gabler, <strong>The</strong><br />

Master Builder, Ghosts and John Gabriel Borkman.<br />

We have also been remarkably successful with our world premieres, which include two plays by Jonathan<br />

Harvey (Rupert Street Lonely Heart’s Club and Hushabye Mountain), Peter Gill’s <strong>The</strong> York Realist and Richard<br />

Bean’s Honeymoon Suite.<br />

ETT’s other successes include the 100th Anniversary production of <strong>The</strong> Importance of Being Earnest, revivals<br />

of <strong>The</strong> Cherry Orchard and <strong>The</strong> Seagull, and Tom Stoppard’s Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead and<br />

Alan Bennett’s <strong>The</strong> Old Country.<br />

We have played in London almost every year, with seasons at the Donmar (four times), the Old Vic (twice) and<br />

the Royal Court (twice), as well as four West End transfers.<br />

INTRODUCTION TO THIS PACK<br />

This education pack is intended as an introduction and follow up to seeing ETT’s performance of <strong>The</strong><br />

<strong>Changeling</strong>.<br />

It is primarily aimed at teachers and students of A-Level <strong>English</strong> and Drama Studies and students in Higher<br />

<strong>Education</strong>. We hope it may also be relevant for other further education courses or drama groups.<br />

We have included some background information about the play, writer and the world of the play. <strong>The</strong>re are<br />

also interviews from the production team and cast, articles on the themes in the production, as well as<br />

suggested areas for discussion, and practical drama exercises.<br />

We hope to enhance your enjoyment and understanding of this production and offer some interesting and<br />

useful information and exercises which will stimulate and inspire your own work.<br />

Aisling ONeill Zambon & Anthony Biggs<br />

3

THE CHANGELING<br />

THE CAST<br />

VERMANDERO Ken Bones<br />

BEATRICE-JOANNA Anna Koval<br />

TOMAZO DE PIRAQUO Daon Broni<br />

ALONSO DE PIRAQUO Gabriel Fleary<br />

ALSEMERO Gideon Turner<br />

JASPERINO Ian Mercer<br />

ALIBIUS Terrence Hardiman<br />

ISABELLA Marianne Oldham<br />

LOLLIO David Cardy<br />

PEDRO/FRANCISCUS Leon Williams<br />

ANTONIO Geoffrey Lumb<br />

DEFLORES Adrian Schiller<br />

DIAPHANTA Samantha Lawson<br />

CREATIVE TEAM<br />

DIRECTOR Stephen Unwin<br />

SET DESIGNER Paul Wills<br />

COSTUME DESIGNER Mark Bouman<br />

LIGHTING DESIGNER Ben Ormerod<br />

COMPOSER Olly Fox<br />

ASSISTANT DIRECTOR Suba Das<br />

FIGHT DIRECTOR Jonathan Waller<br />

CHOREOGRAPHER Susannah Broughton<br />

VOICE COACH Catherine Weate<br />

CASTING DIRECTOR Ginny Schiller<br />

PRODUCER Rachel Tackley<br />

This production opened at the Nottingham Playhouse on 28 th September 2007<br />

4

STEPHEN UNWIN ON THE CHANGELING<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Changeling</strong> (1622) is a perplexing mixture of styles and genres. From one perspective it is a classic<br />

Jacobean revenge drama: set in Catholic Spain, it is explicit about sex and violence, mixes the tragic with the<br />

grotesque, and offers little in the way of consolation or social reform. From another, it is an acutely<br />

perceptive domestic drama about the conflicting claims of familial duty and sexual desire.<br />

<strong>The</strong> play’s main plot is a love triangle; the aristocratic beauty Beatrice-Joanna and the handsome visitor<br />

Alsemero have fallen in love with each other; her father, Vermandero, however, has agreed to marry her off to<br />

the eligible young bachelor Alonso de Piracquo. Meanwhile, Vermandero’s disfigured manservant Deflores is<br />

in love with Beatrice-Joanna and wants her for himself, yet she in turn finds him utterly repulsive. <strong>The</strong><br />

working out of these conflicting passions is the motor of the tragic action.<br />

In their portrait of Beatrice-Joanna, Middleton and Rowley have drawn an intelligent and highly sexed young<br />

aristocrat who is prepared to do anything, including risk damnation, to get what she desires. In her nemesis,<br />

Deflores (the ‘deflowerer’), they show the extent a man will go to be with a woman with whom he is obsessed.<br />

By the end of the play they deserve each other. As Alsemero says to Deflores:<br />

Clip your adulteress freely. Tis the pilot<br />

Will guide you to the Mare Mortuum<br />

Where you will sink to fathoms bottomless.<br />

(5.3)<br />

<strong>The</strong> treatment is exceptionally acute in its psychological perception, even as it retains the highest level of<br />

moral discrimination.<br />

<strong>The</strong> subplot tells a parallel story, but with a comic outcome. <strong>The</strong> asylum keeper Alibius is jealously possessive<br />

of his young wife, Isabella, but does little to show her any affection or love. Two young men, Franciscus and<br />

Antonio, are both obsessed with her but are reduced to pretending to be mad fools in order to see her.<br />

Meanwhile Alibius’ servant, Lollio, wants her too, but cannot get any further than sexual innuendo and bawdy<br />

jokes. <strong>The</strong>y are all defeated by Isabella’s fidelity. If the main plot shows how untramelled sexual desire can<br />

lead to murder and your own death, the subplot shows the more common experience; that it results in<br />

foolishness and humiliation.<br />

Little is known about William Rowley, the comic actor who was largely responsible for the scenes in the<br />

madhouse. But Thomas Middleton, who wrote the main plot, was one of the leading dramatists of his time,<br />

and defies the usual characterisation of the Jacobean playwright as champion of the status quo and loyal<br />

supporter of the King. As Margot Heinemann shows in her definitive study, Puritanism and the <strong>The</strong>atre,<br />

Middleton was associated with the opposition forces which would, within a generation, bring down the<br />

monarchy. She also argues that Middleton, like Ibsen 250 years later, wrote about women of all classes with<br />

tremendous empathy and realism. His portrait of Beatrice-Joanna demonstrates just how rapacious and<br />

amoral certain strands of the aristocracy could be. He prefers instead to put his faith in the wisdom and<br />

decency of the middle class Isabella, or the healthy appetites of the freethinking servant girl Diaphanta.<br />

<strong>The</strong> result is a play which, with its cinematic technique, intercut soliloquies, and quickfire dialogue, is one of<br />

the most theatrical plays in the repertoire. What’s more, its acute psychological realism makes it<br />

astonishingly contemporary. Realism is the true language of the modern theatre and <strong>The</strong> <strong>Changeling</strong> is one<br />

of its key texts. If, ultimately, it cannot share the rarefied air occupied by Hamlet and King Lear, it looks<br />

forward to a world in which kings and queens no longer rule over us, and the intricate lives of ordinary men<br />

and women can become the subject of great tragedy. <strong>The</strong> much despised Deflores speaks for us all:<br />

Why, am not I an ass to devise ways<br />

Thus to be railed at? I must see her still.<br />

I shall have a mad qualm within this hour again<br />

I know, and like a common Garden bull<br />

I do but take breath to be lugged again.<br />

What this may bode I know not. I’ll despair the less<br />

Because there’s daily precedents of bad faces<br />

Beloved beyond all reason. <strong>The</strong>se foul chops<br />

May come into favour one day amongst his fellows.<br />

Wrangling has proved the mistress of good pastime.<br />

As children cry themselves asleep, I have seen<br />

Women have chid themselves abed to men.<br />

(2.1)<br />

5

SYNOPSIS<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Changeling</strong> (1622)<br />

A tragedy by Thomas Middleton (written with William Rowley)<br />

Set in Alicante in Spain, Beatrice-Joanna is daughter of Vermandero, the governor of the castle of Alicante.<br />

Her father orders her to marry Alonso but she falls in love with Alsemero. She asks her father's servant<br />

Deflores, whom she detests, to murder Alonso. He does so, but in return demands the right to take her<br />

virginity. She marries Alsemero but arranges to have her maid, Diaphanta, take her place on the wedding<br />

night. Deflores kills the maid to avoid betrayal.<br />

Meanwhile there is a comic subplot (by Rowley) in which Vermandero's men, Antonio (the <strong>Changeling</strong>) and<br />

Franciscus, both pretend to be crazy in order to gain access to Isabella, the young wife of Alibius, a jealous<br />

old mad-house doctor. She rejects them both. <strong>The</strong>y emerge from the madhouse and are charged with<br />

Alonso's murder which happened just as they vanished.<br />

<strong>The</strong> crime of Beatrice-Joanna is suspected by Alsemero and she admits that she ordered Alonso’s death. But<br />

Deflores tells the whole story, wounds Beatrice-Joanna mortally, then kills himself.<br />

Adrian Schiller as DEFLORES and Anna Koval as BEATRICE-JOANNA (photo: Stephen Vaughan)<br />

6

THOMAS MIDDLETON (1580-1627)<br />

Middleton was one of the most successful and prolific playwrights of the Jacobean period (alongside Webster,<br />

Jonson and Fletcher amongst others). Like Shakespeare, he is considered one of the few Renaissance<br />

dramatists to achieve equal success in comedy and tragedy. He was also an accomplished writer of masques<br />

and pageants.<br />

Thomas Middleton was born in 1580 in London. His father was a prosperous bricklayer who died when<br />

Middleton was five. Middleton attended grammar school and in 1598 he enrolled at Queen’s College, Oxford,<br />

where he studied from 1598 to 1601. <strong>The</strong>re are no records indicating whether he ever received a degree.<br />

He published three volumes of verse by 1600, and it is believed that he had already begun to write for the<br />

stage at that time. He was a working playwright by 1602, and his earliest surviving independent play, Blurt,<br />

Master Constable (1602) was printed.<br />

In 1603 Middleton married. <strong>The</strong> same year, an outbreak of plague forced the closing of all the theatres in<br />

London, and James I assumed the <strong>English</strong> throne. <strong>The</strong>se events marked the beginning of Middleton's<br />

greatest period as a playwright. Having passed the time during the plague composing prose pamphlets, he<br />

returned to drama with great energy.<br />

Middleton was an industrious writer, producing ‘citizen comedies’ and revenge tragedies for several<br />

companies. His comedies, written for boys' companies between 1602 and 1607, include A Mad World, My<br />

Masters (c.1605), A Trick to Catch the Old One (c.1605) and Michaelmas Term (c.1606). For the adult<br />

companies, he also wrote A Chaste Maid in Cheapside (1611), a satire which exposed bourgeois vice in<br />

contemporary London.<br />

He collaborated with Thomas Dekker on the comedies <strong>The</strong><br />

Honest Whore [Part I] (1604), <strong>The</strong> Family of Love (1603-<br />

1607), and <strong>The</strong> Roaring Girl (1610), a biography of<br />

contemporary thief Mary Frith.<br />

From 1613 Middleton wrote many City of London<br />

pageants for the Lord Mayor, and served as City<br />

Chronologer from 1620 until his death in 1627. But he<br />

continued to write plays as well, including his<br />

collaborations with William Rowley; A Fair Quarrel (1617),<br />

<strong>The</strong> World Tossed at Tennis (1620) and <strong>The</strong> <strong>Changeling</strong><br />

(1622).<br />

Middleton's wildly successful patriotic drama, A Game at<br />

Chess (1624), was closed after nine performances due to<br />

its inflammatory anti-Spanish content and the Spanish<br />

Ambassador's outrage. <strong>The</strong> writer and the actors were<br />

reprimanded and fined. One of Middleton's last plays,<br />

Women Beware Women (c.1625), was a tragedy where<br />

the final “slaughter” scene verged on comedy, a matter<br />

which has persuaded some critics that Middleton was also<br />

the author of <strong>The</strong> Revenger's Tragedy (1607).<br />

Middleton died at his home, in Newington Butts<br />

(Southwark, London) and was buried there on July 4,<br />

1627.<br />

Portrait of Thomas Middleton<br />

7

BACKGROUND TO THE CHANGELING<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Changeling</strong> by <strong>English</strong> dramatists Thomas Middleton and William Rowley, was first performed at London’s<br />

Phoenix <strong>The</strong>atre in 1622. <strong>The</strong> play was first printed in London in 1652 or 1653 and was popular in its day,<br />

but then fell into neglect. <strong>The</strong> last performance before modern times was in 1668. Interest in the play<br />

renewed in the twentieth century, and since 1930 there have been numerous successful productions in<br />

Britain and around the world.<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Changeling</strong> is considered to be Middleton’s finest tragedy. It was common at the time for dramatists to<br />

collaborate, and Middleton and Rowley wrote five plays together over a period of five years. For <strong>The</strong><br />

<strong>Changeling</strong> scholars believe that Rowley wrote the first and last scenes and the sub plot, while Middleton was<br />

responsible for the main plot and the characterisation of the major characters.<br />

Middleton wrote characters who defied the social norms and moral codes of their time. He wrote three-<br />

dimensional characters, which contradict the conventional characters we may initially assume them to be.<br />

<strong>The</strong> archetypes he does present are given further weight by being set against characters who defy<br />

convention, for example, Vermandero and his daughter, Beatrice-Joanna. This in turns lead us to explore and<br />

question the relationships and society they exist in. Each character has their own moral identity.<br />

He was particularly skilled in writing female roles; women who behave according to their own will. Most<br />

notably this appears in <strong>The</strong> <strong>Changeling</strong>; where the women are fully fleshed, complex characters who go<br />

through a journey in the play, rather than being an appendage to the male characters.<br />

Middleton could be described as a cynical writer, or one who wrote psychologically realistic characters.<br />

<strong>The</strong>mes in the play :<br />

• Madness and sanity<br />

• <strong>The</strong> role of women and sexuality<br />

• Class and status<br />

• Reason and passion<br />

• Appearance verses reality<br />

• Human corruption<br />

• Sin and temptation<br />

• Self destruction<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Changeling</strong> and its Relevance Today<br />

Questions:<br />

• Why do you think the play was titled <strong>The</strong> <strong>Changeling</strong>?<br />

• How is <strong>The</strong> <strong>Changeling</strong> relevant to today’s audiences?<br />

Exercises:<br />

• Search for stories in our current newspapers which relate to the themes in the play.<br />

• Consider contemporary plays and stories to find examples of character’s who don’t fit into our<br />

society’s rules and conventions.<br />

8

JACOBEAN DRAMA<br />

<strong>The</strong> term ‘Jacobean’ is used to describe the great flowering of dramatic writing that took place during the<br />

reign of King James I (1603-1625). As well as several plays of Shakespeare’s maturity – above all Macbeth,<br />

King Lear, Antony and Cleopatra and <strong>The</strong> Tempest – the masterpieces of Jacobean drama include Ben<br />

Jonson’s <strong>The</strong> Alchemist, John Webster’s <strong>The</strong> Duchess of Malfi, John Ford’s Tis Pity She’s a Whore and<br />

Middleton and Rowley’s <strong>The</strong> <strong>Changeling</strong>.<br />

Queen Elizabeth died in 1603 and the last ten years of her reign were troubled by widespread famine,<br />

popular rebellion, religious polarisation and a steadily worsening economic climate; these tendencies were<br />

exacerbated by the coronation in 1603 of the divisive and controversial James. <strong>The</strong> emergence of<br />

Puritanism, a powerful new grouping with a strong emphasis on the individual’s relationship with God, led to<br />

an increased questioning of the social order which would reach its climax with the <strong>English</strong> Revolution and the<br />

Civil War.<br />

This darkening of the social and political landscape was matched by widespread developments in science,<br />

philosophy, religion and culture. Profound questions about the position of mankind in the universe, the<br />

relationship between nature and human beings, and the role of the divine (and the satanic) in human<br />

behaviour all led to a growing sense of unease. At the same time, rural poverty and the rapid growth of<br />

London resulted in an increasingly dangerous mob, while the unlocking of new economic energies and the<br />

emergence of a new class of risk-taking entrepreneurs (capitalists, in fact) further widened the gap between<br />

rich and poor and undermined the social cohesion that marked the middle years of Elizabeth’s reign.<br />

All of this is reflected in the drama of the time which, in the best writers, is characterised by a restless<br />

questioning and a refusal to come to easy conclusions. Many of its leading characters – like Deflores in <strong>The</strong><br />

<strong>Changeling</strong> – refuse to accept their position in the social order, and many of its stories dramatise the<br />

divisions emerging between classes, sexes and generations. <strong>The</strong>y show daughters rebelling against fathers,<br />

servants against their masters, and human beings against God; as such these extraordinary plays are not just<br />

unique documents of their time, they speak to any period where the world is changing.<br />

Jacobean Playhouses<br />

Stephen Unwin<br />

Jacobean theatre sees playwrights moving away from earlier Elizabethan theatre and developing a more<br />

intense dramatic style. Performances moved from the outdoor theatres into private halls. This had a strong<br />

effect on a play's construction and staging. Audiences tended to become more elite, and a focus on wit, black<br />

humour and subtlety replaced the previous 'barnstorming' productions which had to hold an audience’s<br />

attention in the open air, with a noisy bustling crowd.<br />

<strong>The</strong> ‘indoor’ theatres enabled plays to be performed in all weathers. Candlelight was used to focus attention<br />

towards the stage, with the shadows creating a more atmospheric performance.<br />

Plays conducted in a more formal<br />

setting, where all spectators were<br />

seated, led to a more formal<br />

playing style. While old traditions,<br />

such as males playing the female<br />

roles continued, the actor reacted<br />

and performed differently within<br />

the new venues. Actors’<br />

performance styles became<br />

‘smaller’, and their character<br />

portrayals more dramatically<br />

intense.<br />

Intervals appeared between the<br />

plays’ acts with music and masque<br />

becoming an important feature in<br />

many plotlines and the plays’<br />

imagery.<br />

A model reconstruction of the interior of a Jacobean theatre<br />

9

INTERVIEW WITH STEPHEN UNWIN<br />

Director<br />

You’ve called <strong>The</strong> <strong>Changeling</strong> the greatest tragedy in <strong>English</strong> outside of Shakespeare, why?<br />

What this play has is a level of psychological realism, amazing realism that nobody else got. It hasn’t quite got<br />

the great grand genius of a King Lear, but it goes right inside these human beings. I think it’s more like Ibsen<br />

than Shakespeare because it is so psychologically intricate. It hasn’t got the great rolling language of<br />

Shakespeare or of Webster or Marlowe. It’s much tougher than that … it’s much quicker. And it has this<br />

amazing feeling of interiority, of the inner life of these people.<br />

<strong>The</strong>re are only three female characters in the play, can you tell us about them?<br />

And all three of them are superbly drawn. One of the amazing things is that their sexuality is so upfront … and<br />

that the writer seems to be so intrigued by that … but not in a simplistic, moralist way I don’t think. I suppose<br />

you could say that Beatrice-Joanna’s sexuality leads her to do terrible things … but I think it’s more that he’s<br />

saying; this is the truth, this is real, this is passionate, and complicated things happen. But you see the<br />

realism of Diaphanta having sex with Alsemero and staying longer than she should, it’s an astounding bit of<br />

realistic writing … Shakepeare would never get anywhere near that … because it’s kind of, well … there’s<br />

pleasure in that, she’s enjoying it, and that kind of stuff puts it into a modernity of understanding and<br />

psychology.<br />

Are we getting a slice of contemporary politics in the play too, an attitude to the monarchy for instance?<br />

I think there are some politics about the aristocracy. It’s a huge simplification but it looks like Middleton was<br />

a sympathiser of the parliamentary cause in the years leading up to the Civil War, which was more of a middle<br />

class group, and it seems the aristocracy, the Spanish, are shown to be worryingly corrupt, and if there are<br />

any virtues and values around then they are more likely to be in the middle class, or even in the working<br />

class. Deflores is a fallen aristocrat, it’s important to remember that. I think what we have here is a sceptical<br />

writer who sees the world in realistic terms.<br />

How do the two plots express this and link together?<br />

Stephen Unwin<br />

directs Gideon Turner<br />

as ALSEMERO and<br />

Anna Koval as<br />

BEATRICE-JOANNA<br />

in rehearsal (photo:<br />

Stephen Vaughan)<br />

Well they are kind of thematically linked. <strong>The</strong> main plot is about what would you do for love? Answer: you get<br />

a man killed. <strong>The</strong>n the sub-plot is: what would you do for love? Answer: I’ll disguise myself as a madman. Both<br />

are ruled by passion … and both lead to evil and foolish things. One of the really hard things to do with this<br />

play is to show why the mad scenes are there, but I think if you realise that love is a madness that leads<br />

people to do all sorts of strange things, you question: who really is mad? One of things we’ve tried to do with<br />

the set is to merge these two worlds by putting them in this great Victorian madhouse, this asylum.<br />

10

MADNESS AND SANITY IN THE 17 TH CENTURY<br />

Madness and sanity spins the plot in <strong>The</strong> <strong>Changeling</strong>. To understand the world of the play, it is important to<br />

begin to understand attitudes to madness in the Jacobean period.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Medieval belief, that mental illness was caused by evil spirits, continued into the 17 th Century. <strong>The</strong><br />

mentally ill were thought to be dangerous, defective and incompetent and were put in prison or locked away<br />

in asylums. <strong>The</strong>re were no professionals to take care of them and they were subject to cruel torture; being<br />

locked up in closets or cages for being disobedient. Mental illness was considered to be irreversible. <strong>The</strong> only<br />

people inmates communicated with were each other, and as a result of unprofessional and untrained staff,<br />

they often became more ill.<br />

In the 17 th Century any ‘care’ for the mentally ill was offered at such institutions as Bethlem Royal Hospital.<br />

This hospital, the original ‘Bedlam’, was one of the world’s first hospitals for the treatment of mental illness.<br />

It was founded in 1247 as the priory of St Mary of Bethlehem. By the 14 th Century it was already treating the<br />

insane. In 1547 it came under the control of the City of London as one of the five Royal hospitals refounded<br />

after the Reformation. Medical treatment for insanity was largely ineffective throught this time. Those<br />

considered violent and dangerous were restrained with iron manacles and chains.<br />

Bethlem Royal Hospital was only the second of its kind in Europe. It was like being in a zoo for the patients;<br />

for a small price the public could walk through the hospital. <strong>The</strong> study of human behaviour began to increase,<br />

but until the middle of the 18th Century there were no real advancements.<br />

Madness in <strong>The</strong> <strong>Changeling</strong> is closely related to love, passion and lust, and the loss of reason. Beatrice-<br />

Joanna loses reason, when wanting to do anything for her love of Alsemero. Deflores goes to the depths of his<br />

own dark passion to win over Beatrice-Joanna. In order to win over Isabella, Antonio poses as a fool and<br />

Franciscus pretends to be a madman. Alibius is a fool for love regarding his wife Isabella. One could infer that<br />

most of the characters in <strong>The</strong> <strong>Changeling</strong> are mad.<br />

<strong>The</strong> lines between madness and sanity are blurred in the two parallel worlds in the play. It is in the castle,<br />

where all appears to be noble and genteel, that Deflores’ and Beatrice-Joanna’s hidden crimes of passion<br />

take place. In the asylum, we see open debauchery and cruelty, yet the characters that emerge out of this<br />

chaos most strongly are Lollio, who outwits his master Alibius, and Isabella, who outwits all of the male<br />

characters. <strong>The</strong> <strong>Changeling</strong> highlights the obscure lines between life and death, sanity and madness.<br />

‘Madness’ and Sanity<br />

Questions:<br />

• How do we define ‘madness’ in our society today?<br />

• What constitutes sanity?<br />

• Are the symptoms of love and passion like that of insanity?<br />

• What is the relevance of the main plot to the sub plot?<br />

Exercise:<br />

• Draw up a list of parallels between the main and sub-plot.<br />

11

REHEARSING THE CHANGELING<br />

<strong>The</strong> Director’s Approach<br />

Director, Stephen Unwin’s overall approach to rehearsal is strongly text based; he is thorough in consistently<br />

guiding the actors to be specific in their scenes, to avoid generalised performances, by exploring the text indepth.<br />

He and the actors spent a long time studying and analysing the text to discover the meaning of the scenes,<br />

the language and to gain a clear perspective on how the scenes should be played. <strong>The</strong> actors with the<br />

director had lengthy discussions to gain a full understanding of each character.<br />

Practical Exercises used in Rehearsal<br />

• <strong>The</strong> aim of this exercise is to help the actors gain a better understanding of which words and<br />

phrases, spoken to them by other characters, their character really responds to.<br />

Two actors who have a dialogue together, sit on two chairs back-to-back. As the first actor speaks,<br />

the second actor vocalises their instinctive, emotional responses in modern, non-verse <strong>English</strong>, and<br />

then vice versa.<br />

This produces a lot of noise, and is practical when the actors in question have a strong enough<br />

command of their lines not to be distracted by the other person speaking. This is also why they sit<br />

back-to-back.<br />

• This exercise is used to make the actors on stage aware of what is unusual and strange about what<br />

actually happens in the play.<br />

<strong>The</strong> actors are instructed to act out the ‘ordinary’ version of the scene, and then play the version in<br />

the script. For example, at the start of the play, Beatrice-Joanna leaves a church. In an ‘ordinary’<br />

version of this scene, she may simply walk off and go home or have merely a passing conversation<br />

on her way, but instead she is distracted by Alsemero, who then declares that he loves her.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Director and Actor in Rehearsal<br />

Question:<br />

• Choose your favourite character from the play and imagine you are an actor playing this role,<br />

what does your character want more than anything else in the play?<br />

Exercise 1:<br />

• As actors, playing Beatrice-Joanna and Deflores, use the following excerpt to identify ‘wants’ on<br />

every passage spoken. <strong>The</strong>n play the scene, literally announcing your chosen ‘want’ prior to<br />

each section, e.g.:<br />

Beatrice-Joanna: I want to engage you intimately – Oh my Deflores<br />

<strong>The</strong> group should suggest ‘wants’ for the actors that feel most apt for the characters needs<br />

and the actor must play the chosen ‘want’ as effectively as possible whilst saying the lines.<br />

If a chosen ‘want’ isn’t effective enough, maybe it’s the wrong one? Consider why and think of<br />

and try alternatives.<br />

Once the group are happy with the chosen ‘wants’ for the actors, let the whole scene be played<br />

out once whilst announcing the ‘wants’ prior to the line.<br />

Re-play the scene again, this time not stating the ‘wants’ but going back to using the text as it<br />

stands. However, make sure the ‘wants ‘ are still being strongly played.<br />

12

[ACT 2 SCENE 2]<br />

BEATRICE-JOANNA<br />

...Oh my Deflores.<br />

DEFLORES<br />

How's that?<br />

She calls me hers already, ‘my Deflores’.<br />

You were about to sigh out somewhat, madam.<br />

BEATRICE-JOANNA<br />

No, was I? I forgot. Oh.<br />

DEFLORES<br />

<strong>The</strong>re tis again.<br />

<strong>The</strong> very fellow on it.<br />

BEATRICE-JOANNA<br />

You are too quick, sir.<br />

DEFLORES<br />

<strong>The</strong>re's no excuse for it now. I heard it twice, madam.<br />

That sigh would fain have utterance. Take pity on it<br />

And lend it a free word. Alas, how it labours<br />

For liberty. I hear the murmur yet<br />

Beat at your bosom.<br />

BEATRICE-JOANNA<br />

Would creation -<br />

DEFLORES<br />

Ay, well said, that's it.<br />

BEATRICE-JOANNA<br />

Had formed me man.<br />

DEFLORES<br />

Nay, that's not it.<br />

BEATRICE-JOANNA<br />

Oh tis the soul of freedom.<br />

I should not then be forced to marry one<br />

I hate beyond all depths. I should have power<br />

<strong>The</strong>n to oppose my loathings, nay remove them<br />

Forever from my sight.<br />

DEFLORES<br />

Oh blest occasion.<br />

Without change to your sex you have your wishes.<br />

Claim so much man in me.<br />

BEATRICE-JOANNA<br />

In thee, Deflores?<br />

<strong>The</strong>re's small cause for that.<br />

DEFLORES<br />

Put it not from me.<br />

It's a service that I kneel for to you.<br />

BEATRICE-JOANNA<br />

You are too violent to mean faithfully.<br />

<strong>The</strong>re's horror in my service, blood and danger.<br />

Can those be things to sue for?<br />

DEFLORES<br />

If you knew<br />

How sweet it were to me to be employed<br />

In any act of yours, you would say then<br />

I failed and used not reverence enough<br />

13

When I receive the charge on it.<br />

BEATRICE-JOANNA<br />

This is much methinks.<br />

Belike his wants are greedy and to such<br />

Gold tastes like angels' food. Rise.<br />

DEFLORES<br />

I'll have the work first.<br />

BEATRICE-JOANNA<br />

Possible his need<br />

Is strong upon him. <strong>The</strong>re's to encourage thee.<br />

As thou art forward and thy service dangerous<br />

Thy reward shall be precious.<br />

DEFLORES<br />

That I have thought on.<br />

I have assured myself of that beforehand<br />

And know it will be precious. <strong>The</strong> thought ravishes.<br />

BEATRICE-JOANNA<br />

<strong>The</strong>n take him to thy fury.<br />

DEFLORES<br />

BEATRICE-JOANNA<br />

Alonzo de Piracquo.<br />

I thirst for him.<br />

DEFLORES<br />

His end's upon him.<br />

He shall be seen no more.<br />

BEATRICE-JOANNA<br />

How lovely now<br />

Dost thou appear to me. Never was man<br />

Dearlier rewarded.<br />

Exercise 2:<br />

• Imagine you are a director, write an outline of a plan for a first day of rehearsal for<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Changeling</strong>.<br />

Share your opening director’s introduction with the group.<br />

14

INTERVIEW WITH MARK BOUMAN<br />

Costume Designer<br />

Stephen (Unwin) was talking about modernizing or bringing the costumes up to date. How have you done<br />

that?<br />

Our intention wasn’t necessarily to bring them up to date but to have a contemporary element. So that when<br />

you first look at them, the audience has got a feeling that it’s a period play, but when you look closer, just as<br />

the script has some quite modern bits in it, so the costume has too… so doublets have contemporary biker<br />

jacket zips or have seams, and details that you’d find on contemporary clothes as opposed to what you’d find<br />

on real period costumes… so we’re morphing a bit of a period costume with contemporary and making that a<br />

new language.<br />

How does that fit in with the Victorian madhouse set design?<br />

Well it’s more like a crumbling mansion… that could be an ancient period castle, but again if you look closer<br />

it’s got the odd radiator or an exit sign or some modern metal doors… so on first look, you think you’re in a<br />

period world but on closer inspection, as you’re watching the play you realise there are some much more<br />

modern bits there… same as with the story, it’s a sort of posh lady that gets told to marry, but she’s like<br />

“actually I don’t want to do this… I want to do something for myself”.<br />

How have you expressed these psychologically real and developed female characters in their costume?<br />

Instead of being an add-on or a background character, they are very<br />

much in the foreground, so opposed to having pretty Jacobean colours<br />

that are quite muted, we’re putting Beatrice-Joanna in a shocking fuschia<br />

pink with black lace …and then other colours, like her servant Diaphanta<br />

who instead of wearing a skirt, like most women up to the 1920’s would<br />

have worn a skirt, she’s actually in trousers but a modern version of a<br />

period doublet on her top half.<br />

Tell us more about Diaphanta’s costume?<br />

With her it’s more a case of contemporary fabrics. Her colours are more<br />

muted because she is a servant woman, a bit more working class, but<br />

I’ve added some African influences because of who the actress<br />

Samantha is, and then Isabella is in a shocking orange, which again<br />

you’d never find if you look at period paintings.<br />

Costume designs by Mark Bouman<br />

and examples of ideas which have<br />

influenced his designs for DIAPHANTA<br />

and BEATRICE-JOANNA<br />

15

Are the costumes linked in the two different<br />

plots?<br />

<strong>The</strong> asylum section is much more colourful…<br />

autumnal colours, oranges and reds, warmer<br />

colours really, while the castle is quite stark<br />

and has a lot of blacks and grey, whites and<br />

silver with Beatrice-Joanna standing out in her<br />

fuschia, but generally the slightly more comic<br />

characters having more vibrant colours in their<br />

costume.<br />

Stephen has mentioned how important class is<br />

in this play. How have you represented status<br />

in costume?<br />

I’m playing a little bit with the chaps’<br />

costumes… the father might be in period<br />

breeches, while the younger guys perhaps<br />

might be in jeans and a doublet. Just as you<br />

might see in the street where some might be<br />

wearing pin-stripe suits, others are wearing<br />

casual cottons and denims, I’m using a little of<br />

that fabric language in the costumes to<br />

demonstrate hierarchy within the play.<br />

Mark Bouman’s design and<br />

inspiration for DEFLORES<br />

16

INTERVIEW WITH PAUL WILLS<br />

Set Designer<br />

So, how did the design concept of a Victorian madhouse come about?<br />

I think my initial response, after reading the play and going to see Stephen, was for this very derelict,<br />

crumbling building. <strong>The</strong> play seemed to make sense in that world that was very distressed and old, and<br />

broken down, and because there’s the palace and also the madhouse, we were trying to find a world that<br />

both of those could kind of exist in. A big old mad Victorian lunatic asylum seemed an apt way of going about<br />

things.<br />

How does the design facilitate the two separate plots?<br />

Through various elements: the grandeur of the set is encapsulated in the tall walls with a series of pillars<br />

along the back wall. Through lighting, you can transform the space into being quite grand and quite epic, like<br />

a palace, and we have lots of windows that we can bring shafts of light through that’ll work for a palace. <strong>The</strong><br />

squalor of the madhouse will be shown by bringing out the dirty, kind of rusty broken down elements of it and<br />

the caged door, and the locks on the door. <strong>The</strong>re’s lots of talk of alley ways and passages and labyrinths; and<br />

to have all the doors on the set and corridors that lead off into darkness just kind of seemed to make sense<br />

to the design.<br />

Some aspects of the set which stand out are those which are out of date; what’s the idea behind that?<br />

I think Steve was quite keen, quite early on, to make the figures exist in the set, as almost ghostly apparitions<br />

of a time gone past, which is why there’s a slight contradiction between the set, which is Victorian and the<br />

costumes which Mark is doing, which seem to juxtapose each other. <strong>The</strong>y feel that they once inhabited that<br />

space but they don’t really belong there.<br />

<strong>The</strong> set appears to be quite a solid structure. How does it transform?<br />

Part of the set design by<br />

Paul Wills<br />

Because there are so many different walls and panels; we’ve put lots of windows in the space and lots of<br />

practical light bulbs, Ben (Lighting Designer) can really transform the space because every different surface<br />

he can light in a different way.<br />

17

INTERVIEW WITH BEN ORMEROD<br />

Lighting Designer<br />

What is your job as a lighting designer?<br />

Well, to illuminate! I happen to believe that there is nothing quite as beautiful, or atmospheric, or exciting on<br />

stage as the face, so my first job is to reveal that. I also have to evoke a world in which it is possible for the<br />

events of the play to take place. Modern audiences tend to treat theatre far too literally; anything that can lift<br />

them out of the pedestrian into the poetic is a good thing, and lighting, in this visual age, can help.<br />

How do you begin to think about the lighting for a show?<br />

I try to make all the artistic decisions first, and only then look at the lights I've been provided with. Lighting is<br />

about ideas, not equipment; it's best to know what you need to do before you find out what is possible. You<br />

usually end up being able to do what you want if the ideas are clear enough to begin with.<br />

What's the process for you?<br />

Of course I start by reading the play, making lists of references to weather, time of day, light as metaphor and<br />

so on. I try not to make any choices at this stage, just ask as many questions as possible. <strong>The</strong>n I start meeting<br />

with the director and the designer to look over the model of the set and storyboard of the show, if there is<br />

one. I'll start sketching ideas at this stage; usually the plan deadline isn't until near the end of rehearsals so I<br />

try not to commit myself to anything like a finished plan until I've spent some time in rehearsals. This is the<br />

most important time for me; the more I understand what the director and actors are working towards, the<br />

easier it is to join them on that journey. Most of my best ideas come out of the rehearsal room.<br />

What difference does good lighting make to the production?<br />

You start with a dark space. An actor must be seen, so you light the actor. Light is by it's very nature<br />

atmospheric, or rather, evocative, so when you light the actor you must make a choice as to what that light is<br />

going to evoke. Is it sunlight, daylight or moonlight? Electric light or light through water? <strong>The</strong>re is another<br />

cliché, as old as the one about good lighting being invisible, which says that lighting is atmospheric at the<br />

expense of visibility; good lighting squares that circle by accepting that the face is the most expressive object<br />

on stage and that light doesn't add atmosphere, it reveals it.<br />

<strong>The</strong> dance in the madhouse [4.3] (photo: Stephen Vaughan)<br />

18

INTERVIEW WITH TIMANDRA DYER<br />

Production Manager<br />

How are you involved from the initial design to the construction of the set?<br />

<strong>The</strong> process from design through to construction starts when the production managers meet with the<br />

designer at the white card model stage to get an idea of what’s in the designer’s head regarding the design<br />

for the set. At that stage I’m looking at whether the design/set can be built within the budget we’ve got. Also<br />

for ETT that meeting would also include me thinking about ‘is the idea that the designer is coming up with<br />

tourable?’ As production manager for a touring company I have certain perameters which I have to bear in<br />

mind when looking at a set, for example at ETT, the set, lighting, sound equipment, costumes/props etc all<br />

have to fit in a single truck. <strong>The</strong>re’s also only a certain amount of crew we can work with at each venue, so I<br />

have to consider ‘can it be fitted up by the amount of crew we have at each venue?’. <strong>The</strong> design then gets<br />

costed up and when we know we can build the set within budget this becomes the final design for the model<br />

which is presented to the full company at the start of rehearsals. Set construction begins and my involvement<br />

is to make sure it is built on time to the standard and look of the original design within budget!<br />

What has been particular about this production?<br />

<strong>The</strong> interesting nuance with this production is the fact that it’s a co-production with Nottingham Playhouse.<br />

So, at the white card phase looking at the model, there are certain things that the production manager from<br />

Nottingham would say, ‘Yes, you can go with…’ and I would say, ‘that doesn’t work for us for touring’.<br />

An example, would be the materials used in the set, such as the floor. <strong>The</strong> floor that Paul Wills has designed<br />

in the set has to look decrepit like broken concrete. Now, if the set was just stopping in one theatre i.e.<br />

Nottingham, we would have probably said, ‘We can go with a painted dance floor’. Whereas I would come<br />

from a touring perspective and say, ‘I need a material that is more durable’. We’re going to be taking the<br />

floor up and down across eight venues and I need to make sure that from when the floor/set leaves<br />

Nottingham to when it’s put down in the Lowry (our last venue), it looks the same and we won’t get that effect<br />

or durability with a dance floor. So touring has driven the decision there because we’re actually going for a<br />

wooden floor, which will be laid in sheets.<br />

During the production process, have you had to alter any decisions you’ve made earlier in the rehearsal<br />

room?<br />

Yes. Last week at rehearsals it was decided that Terrence Hardiman’s character would have a desk and<br />

some activity in the DSL (downstage left) corner. When we originally looked at a model for the set we were<br />

going to have a set with little or no furniture and gradually more and more bits of furniture have been added.<br />

Terrence suggested it might be an idea to have a desk in the DSL corner, which Steve and Paul didn’t<br />

particularly want, they want Terrence to have a writing area but not a desk. <strong>The</strong> next step is to go back to the<br />

workshops and look at what could be added to the construction. <strong>The</strong>n it required another conversation with<br />

Paul as to what else could be put in this area and look as though it was a logical part of the architecture of<br />

the set? Paul went away and designed a desk/shelf structure, which will live on the wall as a piece of wood<br />

jutting out at an angle.<br />

Model of the set by Paul Wills (photo: Timandra Dyer)<br />

19

THE ROLE OF WOMEN IN 17 TH CENTURY ENGLAND<br />

Marriage & Family<br />

In the 17 th Century, the husband's patriarchal role as governor of his family and household were assumed to<br />

have been instituted by God and nature. <strong>The</strong> family was seen as the secure foundation of society, and the<br />

patriarch's role as parallel to that of God in the universe, and the King in the state.<br />

Women were generally raised to believe that their spiritual and social worth resided above all else in their<br />

practice of, and reputation for, chastity. Unmarried virgins and wives were to maintain silence in the public<br />

sphere and to obey their father and husband, though widows had some scope for making their own decisions<br />

and managing their affairs. At this time, arranged marriages were commonplace; parents would select their<br />

daughter’s future husband and pay a dowry to the groom’s parents.<br />

Religious and legal definitions of male and female roles and norms were stated in the marriage liturgy from<br />

the Book of Common Prayer (1559) and in <strong>The</strong> Law's Resolutions of Women's Rights (1632), both of which<br />

begin from the Bible’s Genesis story of Adam and Eve's creation, marriage, and fall. <strong>The</strong> marriage liturgy sets<br />

forth the purposes of marriage as the Church understood them, the contract of indissoluble marriage ("till<br />

death us do part"). <strong>The</strong> Law's Resolution collected the several laws in place regarding women's legal rights<br />

and duties in each of her three states: unmarried virgin, wife, and widow.<br />

<strong>The</strong>re were many advice books written for women, dealing with specific family roles and duties, such as<br />

Richard Braithwaite’s <strong>English</strong> Gentlewoman (1631), which focused on virtues and activities for women of the<br />

higher classes, drawing attention to expectations of widows' chastity.<br />

Real families and households were not so clearly defined. Letters and diaries from the time have shown us a<br />

more realistic view of families, where specified gender roles were not always so rigid. Some texts written by<br />

women reveal direct challenges to the cultural norms defining gender and household roles.<br />

<strong>Education</strong> & Work<br />

Upper class women, such as Beatrice-Joanna, would<br />

normally be taught at home by a tutor. Subjects included<br />

Latin, French, needlework and conversational skills. <strong>The</strong>y<br />

were also taught how to look and behave in a ‘feminine’<br />

manner, and to play instruments such as the piano. It was<br />

very unusual for upper class women from wealthy families<br />

to work, rather they would manage the home and servants.<br />

Working class women did not go to school or have an<br />

education, they looked after the home, spun cotton or<br />

worked in fields. Children and servants were bound to the<br />

strictest obedience.<br />

Women & Politics<br />

<strong>The</strong> 17 th Century was not an era of drastic changes in the<br />

status or conditions of women. <strong>The</strong>y continued to play a<br />

significant, though not acknowledged, role in economic<br />

and political structures through their domestic activities.<br />

Though not directly involved in politics, women's roles<br />

within the family and local community allowed them to<br />

influence the political system. Women were discouraged<br />

from directly expressing political views counter to their<br />

husbands', or to publicly condemn established systems.<br />

Nevertheless, many women were able to make public their<br />

private views through the veil of personal, religious<br />

writings.<br />

Women participated in various community activities. For<br />

example, women were full members of <strong>English</strong> guilds;<br />

Anna Koval as BEATRICE-JOANNA and Samantha<br />

Lawson as DIAPHANTA (photo: Stephen<br />

Vaughan).<br />

guild records include references to ‘brethern and sistern’ and ‘freemen and freewomen’. Also, during the<br />

upheavals of the <strong>English</strong> Civil War period (between 1642 and 1651), some women claimed voices in the<br />

public sphere: in a petition to Parliament (1649), ‘Leveller’ women (a political movement) asserted some<br />

political rights in the commonwealth; and in 1664 Margaret Fell published a rationale for allowing women to<br />

testify and preach in church, as Quakers often did.<br />

20

<strong>The</strong> Role of Women<br />

Questions:<br />

• Do women have equal rights and freedoms to men today?<br />

• How has a woman’s role changed from the 17 th Century to the 21 st Century?<br />

• Do you think arranged marriage is acceptable in our time?<br />

Exercise:<br />

• In small groups choose one of the questions from above, using the subject, develop a 3 minute<br />

argument for or against. <strong>The</strong>n present to the whole group and discuss.<br />

Marianne Oldham as ISABELLA<br />

and Terrence Hardiman as<br />

ALIBIUS (photo: Stephen<br />

Vaughan)<br />

21

WOMEN & SEXUALITY IN THE CHANGELING<br />

<strong>The</strong> portrayal of the three female characters in <strong>The</strong> <strong>Changeling</strong> are radical in context of the period Middleton<br />

wrote and lived in. <strong>The</strong>y are presented in an entirely human, three dimensional and complex way; not<br />

diminished in the role of either ‘whore’ or ‘virgin’, ‘good’ or ‘bad’. <strong>The</strong>y have a strong sexuality and act out<br />

their desires. In the play the female characters develop and learn about themselves; Beatrice-Joanna<br />

experiences passion and sexual discovery, realising her passion for Alsemero:<br />

‘A True deserver like a diamond sparkles.<br />

In darkness you may see him, that’s in absence<br />

Which is the greatest darkness falls on love<br />

Yet is he best discerned then with intellectual eyesight…<br />

… Some speedy way must be remembered’ (2.1)<br />

And later an attraction for Deflores once their relationship has been consummated. She responds to her<br />

father’s assertion that Deflores is:<br />

‘good on all occasions’ by concurring that he is ‘[a] wondrous necessary man, my lord’ (5.1).<br />

She also states<br />

‘I’m forced to love thee now’,<br />

‘Cause thou provid’st so carefully for my honour’<br />

‘His face loathes one,’ she admits, ‘But look upon his care, who would not love him?’ (5.1)<br />

Diaphanta is shown to enjoy sex for it’s own sake, without guilt. She spends a long time with Alsemero on<br />

Beatrice-Joanna’s wedding night, simply because she is having so much fun. As she says;<br />

‘I never made so sweet a bargain’ (5.1)<br />

And Isabella has a shrewd understanding of<br />

how to outwit lustful men; including Antonio<br />

and Pedro/Franciscus: To Antonio;<br />

‘No I have no beauty now<br />

Nor never had, but what was in my garments.<br />

You a quick sighted lover? Come not near me.<br />

Keep your comparisons, you are aptly clad.<br />

I came a feigner to return stark mad’ (4.3)<br />

<strong>The</strong> appropriate behaviour for women in the<br />

17 th Century was to be chaste and obedient.<br />

This expectancy of chastity and submission to<br />

one's father and husband,therefore defines a<br />

‘bad woman’ when the rules are broken.<br />

Beatrice-Joanna defies her father and future<br />

husband Piraquo and follows her passion for<br />

Alsemero. Women had few options; a ‘good’<br />

woman's essence was a virginal body, so the<br />

very sexuality of that body suggested possible<br />

deviant behaviour.<br />

In ETT’s production of <strong>The</strong> <strong>Changeling</strong>, the Director has portrayed the sex scene between Deflores and<br />

Beatrice-Joanna in a dumb show; Deflores does not physically overpower Beatrice-Joanna, but she seems to<br />

submit to him as she cannot see another way out of the situation she finds herself in.<br />

Beatrice-Joanna and Deflores Sexual Relationship<br />

Small group discussion points:<br />

• Does Beatrice-Joanna consent to have sex with Deflores?<br />

• Does she choose to have sex with him for her own gains?<br />

• Does she feel desire for him?<br />

Anna Koval as BEATRICE-JOANNA and Samantha Lawson<br />

as DIAPHANTA in rehearsal (photo: Stephen Vaughan)<br />

• In the production why does Beatrice-Joanna have sex with Deflores?<br />

22

ASSISTANT DIRECTOR’S ESSAY<br />

by Suba Das<br />

Borrowing a phrase of Henry James, T.S Eliot’s eponymous Lady speaks of her ‘buried life’ in the 1917 poem<br />

Portrait of a Lady. <strong>The</strong> 1917 volume, <strong>The</strong> Love-song of J. Alfred Prufrock and Other Observations abounds<br />

with characters who have half-lives, secret selves and hidden imaginings beneath their surface skin.<br />

Dramatically, the collaboration of Anton Chekhov and Konstantin Stanislavski first explicitly formalised this<br />

idea of subtext, of characters with lives that are buried beneath what they apparently say or do in the late<br />

19 th Century. As the great theatre critic Martin Esslin writes:<br />

‘It was Chekhov who first deliberately wrote dialogue in which the mainstream of emotional<br />

action ran underneath the surface. It was he who articulated the notion that human beings hardly<br />

ever speak in explicit terms among each other about their deepest emotions, that the great,<br />

tragic, climactic moments are often happening beneath outwardly trivial conversation.’<br />

(Martin Esslin, from Text and Subtext in Shavian Drama, in 1922: Shaw and the last Hundred<br />

Years, ed. Bernard. F. Dukore, Penn State Press, 1994)<br />

However, a play like <strong>The</strong> <strong>Changeling</strong>, written some 250 years earlier than Chekhov’s works, with its disguises,<br />

hidden liaisons and masked intentions is packed full of ‘buried life’. Accordingly, a key focus of our rehearsal<br />

room work has been unpacking the depth of the play and finding the tensions that are really bubbling<br />

beneath the surface.<br />

An example from the opening of the play would be Beatrice-Joanna’s first entrance from the church, and her<br />

first encounter with Alsemero. Apparently a very simple, coincidental meeting, this moment is in fact packed<br />

with Beatrice-Joanna’s dangerous rebellion against both social convention and her father’s intended<br />

marriage for her. To help clarify how loaded this moment was, Anna Koval (Beatrice-Joanna) first improvised a<br />

sequence with Samantha Lawson (Diaphanta) of how Beatrice-Joanna might normally leave a church in<br />

stately, austere procession. This made the risk and flirtation of the actual sequence we see on stage<br />

explosively clear for the performers.<br />

<strong>The</strong> interaction of subtext and apparent action comes to a climax in the scene of Beatrice-Joanna’s<br />

commissioning of Deflores to kill Alonzo. <strong>The</strong> scene itself is loaded with asides, in which Deflores and<br />

Beatrice-Joanna reveal their true, and very contradictory intentions beneath the apparent agreement they are<br />

making. This very explicit creation of a subtext makes innuendo a key part of the scene – Deflores tells<br />

Beatrice-Joanna that the thought of killing Alonzo ‘ravishes’, simultaneously disguising and revealing his<br />

intention to claim Beatrice-Joanna’s virginity. Accordingly in rehearsal, we explored ways of staging the scene<br />

that made the subtext entirely explicit, with lots of direct sexualisation, and then completely hidden, to<br />

discover how to strike a balance that allowed both characters to believe they were fulfilling opposing<br />

objectives.<br />

<strong>The</strong> audience is primed for innuendo in the play by the bawdy fun of the madhouse scenes. Alibius and<br />

Lollio’s first scene together is a masterpiece in apparent kindness from Lollio concealing a mine of humour at<br />

the foolish Alibius’ expense– for instance Alibius being an ‘old tree raising himself higher and broader than<br />

the young plants’ implies an old man with a young wife growing older through the cuckold’s horns.<br />

Suba Das (photo: Stephen Vaughan)<br />

In the madhouse scenes, we discovered that<br />

this innuendo could be played for its full worth<br />

as the sexually charged humour of this world<br />

allowed it. However a real danger emerged in<br />

how to handle the interplay between the social<br />

lives of the characters in the courtly scenes, and<br />

their buried narratives. For instance if Deflores’<br />

obsession with Beatrice-Joanna is too apparent,<br />

then Beatrice-Joanna’s decision to trust him<br />

with the commission is a reckless move on her<br />

part. Having identified the character’s subtexts<br />

and buried journeys in the play as part of the<br />

rehearsal process, it is important to then return<br />

to what the action and society of the play itself<br />

demands so that both the visible and invisible<br />

worlds of the play hang together. As the play<br />

proceeds to its gory climax these separations<br />

and distinctions fall apart spectacularly.<br />

23

CAST INTERVIEWS<br />

1. Daon Broni/TOMAZO and Gabriel Fleary/ALONZO<br />

What’s happened in the scene you’ve just rehearsed (See p.25 in this pack)<br />

Gabriel Well, I’ve just been introduced to my wife to be, she’s been betrothed to me for a period of time…<br />

I’m extremely excited to see her, and I’ve come along with my brother who is my parental aspect<br />

right now, you know, he’s committed to look after me and he’s just watched over our first interaction<br />

as an engaged couple…<br />

Daon Yeah, I think basically we’ve come into the scene from two different points of view. Alonso is far<br />

more … he’s younger, he’s less experienced … I am slightly older, more reserved and more<br />

cautious…<br />

Gabriel Well you were raised the first son with far more responsibility for the house, whereas I am allowed to<br />

be more flippant…<br />

Daon So two very different reactions to the same event … from Tomazo’s point of view something isn’t<br />

right, something about this meeting … there’s a certain amount of ceremony, a sort of ritual and<br />

within the context of the play we don’t get to see that when Alonzo first meets Beatrice-Joanna, and<br />

that immediately makes me suspicious of her and her intentions toward my brother, because<br />

ultimately I’m very protective of him, of family, of our family name, of the honour of our family name.<br />

So I think this is me going: hold on, something isn’t right here, let’s just take a step back.<br />

Gabriel Yeah, you’ve got a really objective view while I’m blinded by the fact that I want this girl, I want to<br />

marry her.<br />

Daon Blinded by her beauty.<br />

Gabriel And I’ve got no reason to think she doesn’t feel the same way about me, so the way she reacts, it’s<br />

like ‘Oh, it doesn’t matter’.<br />

Daon <strong>The</strong>re’s an instinctual thing as well, when you see someone and you can’t really put your finger on it,<br />

but you feel something isn’t right, and Tonazo can’t express it because he hasn’t got any real proof.<br />

Why can’t Alonzo see that Beatrice isn’t in love with him?<br />

Daon Broni as<br />

TOMAZO and<br />

Gabriel Fleary as<br />

ALONSO in<br />

rehearsal (photo:<br />

Stephen Vaughan)<br />

Gabriel I’ve got no reason to think otherwise, I mean up to this point …our communications, she’s been<br />

sending gifts …it’s all been ‘yes’. He’s young and naïve, but he’s not looking for faults, he’s happy<br />

with the situation. My brother’s being cautious, I’ve got years of people saying ‘yes she’s perfect for<br />

you, yes she really likes you’, so I’m not going to take one moment where she doesn’t bow deeply<br />

24

enough, she doesn’t blush, whatever. I think my brother’s a little bit stern, a bit straight, he needs to<br />

relax a little, but of course he can’t as head of the household.<br />

Daon I think you’re right. When they enter this scene, Tomazo’s carrying all of that…<br />

Gabriel It’s Wills and Harry isn’t it?<br />

Daon Yeah, and this marriage is like a merging of assets.<br />

Gabriel And she gets a hell of a lot more from marrying a Piracquo, she’s their greatest asset and<br />

suddenly I get that, so I have something that’s mine, while he’s going to run the estate …So I’m<br />

excited about everything, not just the girl, but about being a man and having it all… being my own<br />

man for once.<br />

[ACT 2, SCENE 1]<br />

TOMAZO<br />

So did you mark the dullness of her parting now?<br />

ALONZO<br />

What dullness? Thou art so exceptious still.<br />

TOMAZO<br />

Why let it go then, I am but a fool<br />

To mark your harms so heedfully.<br />

ALONZO<br />

Where's the oversight?<br />

TOMAZO<br />

Come, your faith's cozened in her, strongly cozened.<br />

Unsettle your affection with all speed<br />

Wisdom can bring it to. Your peace is ruined else.<br />

Think what a torment tis to marry one<br />

Whose heart is leapt into another's bosom.<br />

If ever pleasure she receive from thee<br />

It comes not in thy name or of thy gift.<br />

She lies but with another in thine arms.<br />

He the half-father unto all thy children<br />

In the conception, if he get them not<br />

She helps to get them for him. And how dangerous<br />

And shameful her restraint may go in time to<br />

It is not to be thought on without sufferings.<br />

ALONZO<br />

You speak as if she loved some other then.<br />

TOMAZO<br />

Do you apprehend so slowly?<br />

ALONZO<br />

Nay, and that<br />

Be your fear only I am safe enough.<br />

Preserve your friendship and your counsel, brother<br />

For times of more distress. I should depart<br />

An enemy, a dangerous deadly one<br />

To any but thyself, that should but think<br />

She knew the meaning of inconstancy<br />

Much less the use and practice. Yet we are friends.<br />

Pray let no more be urged. I can endure<br />

Much till I meet an injury to her<br />

<strong>The</strong>n I am not myself. Farewell, sweet brother<br />

How much we are bound to heaven to depart lovingly.<br />

TOMAZO<br />

Why here is love's tame madness. Thus a man<br />

Quickly steals into his vexation.<br />

25

2. David Cardy/LOLLIO and Terrence Hardiman/ALIBIUS<br />

You’ve just been rehearsing your first scene in the play (See p.34 of this pack), what’s happening at the<br />

beginning of the scene?<br />

David Well, this is obviously setting up the madhouse…<br />

Terrence I’m Alibius who runs the place, he calls it a hospital .. He professes he’s<br />

going to cure the fools and madman, he’s going to make money out of them too.<br />

David Lollio is his right hand man, in fact he’s the only other man who seems to be working with<br />

him, and my speciality is dealing with fools.<br />

Terrence And mine is to deal with the madmen. You have to remember that at that time people<br />

went to the madhouse to be entertained, to watch the fools and madmen performing … it<br />

was pretty cruel.<br />

David And then my boss has a young wife and …<br />

Terrence I’m pretty concerned I’m going to lose her, and I confide in Lollio that I am older than she<br />

is and I’m frightened to death that she’s going to get taken away by some young fellow.<br />

And Lollio says ‘who have you got to be afraid of?’<br />

David Of course the number one person he’s got to be afraid of is Lollio.<br />

Terrence But I don’t know that, I would never suspect that of him.<br />

David No because he thinks I’m a very diligent servant.. so it sets up the storyline that he’s got a<br />

young wife, that he keeps her trapped, and he asks me to keep her when he’s not about.<br />

Terrence To watch where she goes and keep an eye on her.<br />

David Which is perfect for me because it gives me more opportunity to err…<br />

Terrence Exactly. You see I’m not afraid that the madmen will get at her at all, it’s all these young<br />

men who’ll be after her. But I don’t imagine that these young men will dress up and<br />

pretend to be fools and madmen in order to…<br />

David Get at her. So he wants me to help keep her for himself.<br />

Why does Lollio speak mostly in prose?<br />

David Yes, us low life characters don’t get afforded the quality of poetry.<br />

Terrence Whilst those who are middle class and up get the fiery stuff. It’s often a kind of status<br />

thing.<br />

David And also shows when there is actual high emotion, the verse is always there. Whereas<br />

when there’s comedy and knock about, mistaken identities and the fun, it tends to be<br />

prose.<br />

This scene comes after the set-up of the main plot, how does the asylum plot balance out the other?<br />

David Really? We haven’t read that! We don’t know yet because he haven’t seen it yet .. no it’s<br />

mayhem really. At the beginning you hear whip cracks and shouts and screams, so it’s a<br />

very disordered place in the madhouse, and yet through the story of Isabella she creates<br />

order, she shows the men who try to woo her the true way of life … and the main plot goes<br />

from a very ordered beginning into mayhem and chaos.<br />

Terrence In a strange way our side of the story, the sub-plot, it’s a kind of comment on the main<br />

one, similar themes are there.<br />

David Yes, at the beginning you have two very pure women, and the choices they make in their<br />

lives, how they are going to respond to the men who want to bed them is the main crux.<br />

26

Terrence But it’s the unmarried one, the virgin, who slips, when my wife who one must presume is<br />

not so …<br />

David Yes, but I think that Lollio would get to bed her if there was one more scene …<br />

Terrence You wish!<br />

David Cardy as LOLLIO and Terrence Hardiman as ALIBIUS in rehearsal (photo: Stephen Vaughan)<br />

27

POST-SHOW QUESTIONS FOR DISCUSSION<br />

• What were your expectations of the play before you saw it?<br />

• How did you feel at the end of the play?<br />

• Which character did you have most empathy for, and why?<br />

• Who is the most powerful character in the play?<br />

• What does Beatrice-Joanna want overall in the play?<br />

• Is Beatrice-Joanna unconsciously attracted to Deflores from the beginning?<br />

• How do Isabella and Alsemero’s characters act as a contrast to Beatrice-Joanna and Deflores in the<br />

play?<br />

• How do the lighting and sound designs enhance the atmosphere of the play?<br />

• How does the set symbolise the world of the play?<br />

• How do the costumes in the play help to depict the characters?<br />

• How has the director linked the main plot in the castle and the sub-plot in the asylum?<br />

• What image from the production has stayed in your mind and why?<br />

CLASS AND STATUS EXERCISES<br />

EXERCISE 1<br />

Referring to Act 1, Scene 2, (see p.30 overleaf in pack), experiment with the status of Alibius and Lollio. Lollio<br />

has inherent higher status through his use of metaphor and out-witing language. However, he has to take<br />

care to maintain a seemingly lower status, so as to keep his job! Use a scale of 1 – 10, with 1 being the<br />

lowest and 10 the highest. Explore the use of physicality and stage positioning (‘blocking’) to show Lollio’s<br />

status as 4 and Alibius’ as 8.<br />

EXERCISE 2<br />

See what happens if you invert the status ranking.<br />

EXERCISE 3<br />

Find examples in the text, where characters use their perceived or presumed higher status through class, to<br />

steer the course of events. Are there times when the same could be said of a characters deliberate use of<br />

their lower status (e.g. Deflores)?<br />

28

PLACING THE TEXT IN CONTEMPORARY LANGUAGE<br />

1. ACTING EXERCISE<br />

<strong>The</strong> aim of this exercise is to engage the students/actors in truthful emotions, playing objectives and using<br />

intentions. This may be useful for students who have difficulty connecting with the period of the play.<br />

In pairs, read-through the scene below, where Deflores offers Beatrice-Joanna the severed finger of Alonso.<br />

Now spend some time devising and rehearsing a modernised version of the same scene; still playing the<br />

same relationship, feelings and intentions. <strong>The</strong> story is the same, but the language, setting and time are<br />

contemporary.<br />

Now go back to the original script, carrying through the emotions you have just experienced and anything else<br />

you have learned.<br />

[ACT 3, SCENE 4]<br />

BEATRICE-JOANNA<br />

Deflores.<br />

DEFLORES<br />

Lady.<br />

BEATRICE-JOANNA<br />

Thy looks promise cheerfully.<br />

DEFLORES<br />

All things are answerable. Time, circumstance<br />

Your wishes and my service.<br />

BEATRICE-JOANNA<br />

Is it done then?<br />

DEFLORES<br />

Piracquo is no more.<br />

BEATRICE-JOANNA<br />

My joys start at mine eyes. Our sweetest delights<br />

Are evermore born weeping.<br />

DEFLORES<br />

BEATRICE-JOANNA<br />

For me?<br />

I've a token for you.<br />

DEFLORES<br />

But it was sent somewhat unwillingly.<br />

I could not get the ring without the finger.<br />

BEATRICE-JOANNA<br />

Bless me. What hast thou done?<br />

DEFLORES<br />

Why is that more<br />

Than killing the whole man? I cut his heart strings.<br />

A greedy hand thrust in a dish at court<br />

In a mistake hath had as much as this.<br />

BEATRICE-JOANNA<br />