Great Expectations Education Pack - English Touring Theatre

Great Expectations Education Pack - English Touring Theatre

Great Expectations Education Pack - English Touring Theatre

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

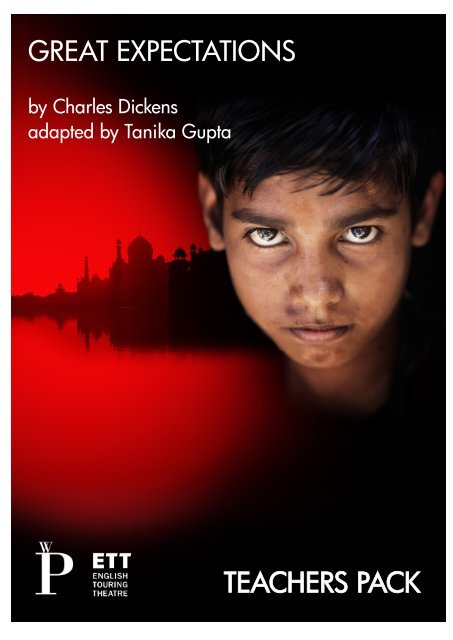

GREAT EXPECTATIONS<br />

by Charles Dickens<br />

adapted by Tanika Gupta<br />

TEACHERS PACK

Foreword from Tanika Gupta<br />

Of all the Dickens novels I read as a youth, <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Expectations</strong> was always a favourite. From<br />

the opening pages of Pip’s terrifying encounter with Abel Magwitch in the graveyard, the<br />

novel’s compelling story and Pip’s momentous life journey had me gripped. This was a story<br />

I could absolutely relate to because of the aspiration of the main character, Pip, to rise<br />

above his class and status and to be educated. It was what my 24 year old father aspired to<br />

when he got on a ship in Bombay in 1961 and sailed to England with the obligatory £1 note<br />

in his pocket .<br />

In this adaptation, I relocated the action of the play to India of 1861 which meant that I<br />

could use Dickens language without having to worry about modernising it. But I didn’t want<br />

to do a straight forward ‘Asian’ adaptation. So, Magwitch is now a black convict from Cape<br />

Colony. He is not a slave (as slavery was abolished by the British by 1861) but an African<br />

sailor with a criminal background. His story, as in the original, is one borne of poverty and<br />

degradation but in this adaptation , his anger at the white man’s treatment of the black<br />

man lends an added fury. He is determined to make Pip into ‘an <strong>English</strong> gentleman’ who will<br />

be able to hold his head high. Miss Havisham, the lawyer Jaggers and Herbert Pocket all<br />

represent the different <strong>English</strong> facets of the Raj whilst Joe Gargery (now a cobbler) and Pip<br />

and Biddy are Indian villagers.<br />

During the early part of the British Raj, Calcutta was the capitol city and Pip journeys there<br />

to begin his education as an <strong>English</strong> gentleman. I was fascinated by the way the Colonial<br />

British authorities in India educated Indians of ‘good families’ in a very <strong>English</strong> way,<br />

encouraging them to embrace <strong>English</strong> values and morals. It wasn’t an accident that<br />

Jawaharlal Nehru (The First Prime Minister of India) and Mohammed Ali Jinnah (The first<br />

Governor General of Pakistan) qualified as barristers in London and then went back to India<br />

to fight for their country’s independence.<br />

Ultimately, Pip’s dissatisfaction at the way he is treated by the <strong>English</strong> leads him to question<br />

their wisdom and awakens his Indian pride. Whilst Pip loses a lot at the end of the play<br />

(Estella, Magwitch and his inheritance), he gains a life-long friend in the quintessentially -<br />

<strong>English</strong> Herbert Pocket. It is this friendship across the races which gives us hope and which<br />

propels us forward into the present day.<br />

Tanika Gupta

Tanika Gupta<br />

Biography<br />

Tanika Gupta was born in 1963 in Chiswick, and is a British playwright of Bengali origin. She<br />

read moden history at Oxford University, then worked for an Asian Women's Refuge in<br />

Manchester and as a community worker in London while beginning to write.<br />

She has written for television, including for East Enders, Grange Hill, A Suitable Boy, The<br />

Bill, Crossroads, and adaptations and original radio plays for BBC Radio. She also wrote for<br />

the Asian network soap, Silver Street, and the BBC World Service soap, Westway.<br />

Her work for theatre includes many stage plays, the most recent being Meet The<br />

Mukherjees (2008), performed at Bolton Octagon theatre. Her first stage play was Voices<br />

on the Wind, which was workshopped at the National <strong>Theatre</strong> Studio in 1995. It tells the<br />

story of her 19-year-old great uncle, Dinesh Gupta, who was an Indian freedom fighter and<br />

was hanged by the British as a terrorist in 1930.<br />

Other plays include: Skeleton (1997) at Soho <strong>Theatre</strong>; an adaptation of Geeta Mehta's A<br />

River Sutra (Indoza 1997); The Waiting Room (2000) at the National <strong>Theatre</strong>; a translation<br />

of Brecht's The Good Woman of Setzuan (National <strong>Theatre</strong> <strong>Education</strong> 2001); Sanctuary<br />

(2002) at the National <strong>Theatre</strong>; and Inside Out (2002). Her adaptation of Hobson's Choice<br />

(2003) played at the Young Vic; Fragile Land (2003) at Hampstead; and Gladiator Games<br />

(2005) at Sheffield Crucible and Stratford East theatres. A group play, Catch (2006), was<br />

performed at the Royal Court <strong>Theatre</strong>, and White Boy (2008) at the National Youth <strong>Theatre</strong>/<br />

Soho.<br />

Tanika Gupta was awarded an MBE in 2008.

Bildungsroman novel definition<br />

Structure<br />

The Bildungsroman Novel<br />

A bildungsroman novel is one that follows a protagonists all-round self-development. More<br />

specifically it follows an individuals growth and development within the context of a defined<br />

social order. Additionally, to spur the protagonist on some form of loss or<br />

discontent must jar them at an early stage away from the family home or setting. The road<br />

to maturity is long where repeated conflict between the hero/heroine’s needs and desires<br />

and the views and judgements enforced by a rigid social order. Eventually the protagonist,<br />

whose values become more aligned with the social order is accepted by society and the<br />

novel ends with an assessment by the protagonist of their new place in that society.<br />

<strong>Great</strong> <strong>Expectations</strong> fits this model of novel by charting Pip’s development from childhood<br />

to young adulthood. On the surface the novel could just be read as Pip’s recollections of<br />

his youth, however the experiences he relates have a direct impact on his development, his<br />

‘expectations’ of his place in society and his realisation of what is actually important.

<strong>Great</strong> <strong>Expectations</strong><br />

by Charles Dickens<br />

adapted by Tanika Gupta<br />

Cast & Crew<br />

Commissioned by Watford Palace <strong>Theatre</strong> in partnership with<br />

<strong>English</strong> <strong>Touring</strong> <strong>Theatre</strong><br />

The production plays at Watford Palace <strong>Theatre</strong> from 17 February to 12 March<br />

before going on a national tour.<br />

Magwitch Jude Akuwudike<br />

Compeyson Rob Compton<br />

Pocket Giles Cooper<br />

Jaggers Russell Dixon<br />

Miss Havisham Lynn Farleigh<br />

Mrs Gargery/Molly Pooja Ghai<br />

Pumblechook Shiv Grewal<br />

Estella Simone James<br />

Joe Gargery Tony Jayawardena<br />

Pip Tariq Jordan<br />

Wemick Darren Kuppan<br />

Biddy Kiran Landa<br />

Writer Tanika Gupta<br />

Director Nikolai Foster<br />

Designer Colin Richmond<br />

Lighting Designer Lee Curran<br />

Composer Nicki Wells<br />

Musical Advisor Nitin Sawhney<br />

Sound Designer Sebastian Frost<br />

Casting Director Kay Magson<br />

Movement and Choreographer Zoobin Surty<br />

Movement and Choreographer Cressida Carré<br />

Fight Director Kate Waters<br />

Associate Director Nicola Samer

Plot summary of the Original Text<br />

Pip is an orphan who lives with his sister (Mrs Joe or Mrs Gargery) and her husband (Joe).<br />

The novel opens with Pip sitting in a cemetery looking at his parents’ tombstones. Pip is<br />

accosted by an escaped convict who orders him to bring him food and a file for his leg<br />

irons. Terrified, Pip complies but the convict is captured.<br />

One day Pip is taken by his Uncle Pumblechook to play at Satis House, the home of the<br />

wealthy but unhinged dowager Miss Havisham. As a young woman she was jilted at the<br />

altar and never having recovered she wears an old wedding dress and all of the clocks in<br />

her house are stopped at the same time. Miss Havisham has a ward, Estella, who is<br />

beautiful, yet cold and cruel. Nevertheless, he falls in love with her and dreams of<br />

becoming a wealthy gentleman so that he might be worthy of her. He hopes that Miss<br />

Havisham will help make him a gentleman and marry him to Estella. His hopes are<br />

disappointed when Miss Havisham decides to help him become a common labourer in his<br />

family’s business.<br />

With Miss Havisham’s guidance, Pip is apprenticed to his kindly brother-in-law, Joe, who is<br />

the village blacksmith. Pip works in the forge unhappily, struggling to better his education<br />

with the help of the plain, kind Biddy and encountering Joe’s malicious day labourer, Orlick.<br />

One night, after an altercation with Orlick, Pip’s sister, known as Mrs. Joe, is viciously<br />

attacked and becomes a mute invalid. From her signals, Pip suspects that Orlick was<br />

responsible for the attack.<br />

One day a lawyer named Jaggers appears with strange news: a secret benefactor has given<br />

Pip a large fortune, and Pip must come to London immediately to begin his education as a<br />

gentleman. Pip happily assumes that his previous hopes have come true—that Miss<br />

Havisham is his secret benefactor and that the old woman intends for him to marry Estella.<br />

In London, Pip befriends a young gentleman named Herbert Pocket. He expresses disdain<br />

for his former friends and loved ones, especially Joe, but he continues to pine after Estella.<br />

He furthers his education by studying with the tutor Matthew Pocket, Herbert’s father.<br />

Herbert himself helps Pip learn how to act like a gentleman. When Pip turns twenty-one<br />

and begins to receive an income from his fortune, he will secretly help Herbert buy his way<br />

into the business he has chosen for himself. But for now, Herbert and Pip lead a fairly<br />

undisciplined life in London, enjoying themselves and running up debts.<br />

Orlick reappears in Pip’s life, employed as Miss Havisham’s porter, but is promptly fired by<br />

Jaggers after Pip reveals Orlick’s unsavoury past. Mrs. Joe dies, and Pip goes home for the<br />

funeral, feeling tremendous grief and remorse.<br />

Several years go by, until one night a familiar figure barges into Pip’s room—the convict,<br />

Magwitch, who stuns Pip by announcing that he, not Miss Havisham, is the source of Pip’s<br />

fortune. He tells Pip that he was so moved by Pip’s boyhood kindness that he dedicated his<br />

life to making Pip a gentleman, and he made a fortune in Australia for that very purpose.<br />

Pip is appalled, but he feels morally bound to help Magwitch escape London, as the convict

is pursued both by the police and by Compeyson, his former partner in crime. A<br />

complicated mystery begins to fall into place when Pip discovers that Compeyson was the<br />

man who abandoned Miss Havisham at the altar and that Estella is Magwitch’s daughter.<br />

Miss Havisham raised Estella to break men’s hearts, as revenge for the pain her own<br />

broken heart caused her. Miss Havisham delighted in Estella’s ability to toy with Pip’s<br />

affections.<br />

As the weeks pass, Pip sees the good in Magwitch and begins to care for him deeply.<br />

Before Magwitch’s escape attempt, Estella marries an upper-class lout named Bentley<br />

Drummle. Pip makes a visit to Satis House, where Miss Havisham begs his forgiveness for<br />

the way she has treated him in the past, and he forgives her. Later that day, when she<br />

bends over the fireplace, her clothing catches fire and she goes up in flames. She survives<br />

but becomes an invalid. In her final days, she will continue to repent for her misdeeds and<br />

to plead for Pip’s forgiveness.<br />

When the time comes for Magwitch’s escape from London Pip is called to a shadowy<br />

meeting in the marshes, where he encounters the vengeful Orlick who attempts to kill Pip.<br />

Herbert arrives just in time with a group of friends and saves Pip’s life. Pip and Herbert<br />

hurry back to help Magwitch’s escape. They try to sneak him down the river, but they are<br />

discovered by the police, who Compeyson tipped off. Magwitch and Compeyson fight in<br />

the river, and Compeyson is drowned. Magwitch is sentenced to death, and Pip loses his<br />

fortune. Magwitch feels that his sentence is God’s forgiveness and dies at peace.<br />

Pip falls ill; Joe comes to London to care for him, and they are reconciled. Joe gives him the<br />

news from home: Orlick, after robbing Pumblechook, is now in jail; Miss Havisham has<br />

died and left most of her fortune to the Pockets; Biddy has taught Joe how to read and<br />

write. After Joe leaves, Pip decides to rush home after him and marry Biddy, but when he<br />

arrives there he discovers that she and Joe have already married.<br />

Pip decides to go abroad with Herbert to work in the mercantile trade. Returning many<br />

years later, he encounters Estella in the ruined garden at Satis House. Drummle, her<br />

husband, treated her badly, but he is now dead. Pip finds that Estella’s coldness and cruelty<br />

have been replaced by a sad kindness, and the two leave the garden hand in hand, Pip<br />

believing that they will never part again.

Themes<br />

<strong>Great</strong> <strong>Expectations</strong> explores several themes including: ambition and self-improvement,<br />

social class, love and loyalty, virtue and good character, crime and the law. The<br />

universality of these themes are what makes <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Expectations</strong> still relevant to<br />

contemporary readers, yet they draw deeply on the social context of its time, rooting it in<br />

the Victorian era.<br />

Ambition and Self-Improvement<br />

The moral of <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Expectations</strong> is that loyalty and conscience are more important than<br />

social advancement, wealth and class. Pip learns this lesson through the course of the<br />

story. Pip’s desire to be a gentlemen, thus becoming a ‘better’ person allows the novel to<br />

explore the idea of ambition and self-improvement. Whenever Pip sees something better<br />

than he has, he wants it. There are three areas of self improvement that are explored:<br />

moral, social and educational.<br />

Moral: Despite some of the poor choices that Pip makes in his desire to better himself Pip is<br />

a moral character. He feels badly when he acts immorally, which in turn propels him to be<br />

a better person in the future.<br />

Social: In love with Estella, Pip desires to better himself in society to be in the same social<br />

class as her. When Pip achieves his goal of becoming a gentlemen his life is not as fulfilling<br />

as he expected.<br />

<strong>Education</strong>al: This is linked to Pip’s social improvement. In order to become a gentleman<br />

and woo Estella Pip needs to be educated. He discovers however, that virtue and kindness<br />

are worth more than an education.<br />

Social Class<br />

Throughout <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Expectations</strong>, Dickens explores the class system of Victorian England,<br />

ranging from the most wretched criminals (Magwitch) to the poor (Joe and Biddy) to the<br />

middle class (Pumblechook) to the very rich (Miss Havisham). The theme of social class is<br />

central to the novel’s plot and to the ultimate moral theme of the book—Pip’s realisation<br />

that wealth and class are less important than affection, loyalty, and inner worth. Pip<br />

achieves this realisation when he is finally able to understand that, despite the esteem in<br />

which he holds Estella, one’s social status is in no way connected to one’s real character.<br />

Drummle, for instance, is an upper-class lout, while Magwitch, a persecuted convict, has a<br />

deep inner worth.<br />

Perhaps the most important thing to remember <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Expectations</strong>’ treatment of social<br />

class is that the class system it portrays is based on the post-Industrial Revolution model of<br />

Victorian England. Dickens generally ignores the nobility in favour of characters whose<br />

fortunes have been earned through commerce. In this way he connects the theme of social<br />

class to the idea of work and self-advancement.

Love and Loyalty<br />

<strong>Great</strong> <strong>Expectations</strong> examines the moral idea that love and loyalty underlie happiness and<br />

misery depending on how well placed that love and loyalty is. Pip’s unrequited love for<br />

Estella, who only ever treats him badly, brings him only misery. Miss Havisham also deals<br />

with the consequences of her misplaced love in Compeyson and her misery is only<br />

compounded by her choosing not to acknowledge the loyalty of the Pockets. Conversely,<br />

the good and kind Joe marries the equally good Biddy and despite their age difference, they<br />

are happy. Additionally <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Expectations</strong> examines the ideas of different kinds of love<br />

such as familial (Joe and Pip), admiration and gratitude (Pip and Magwitch) and what a lack<br />

of love can do to a person, such as Mrs Joe’s treatment of Pip. Again, the theme of love<br />

and loyalty ties in with the overall moral theme of <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Expectations</strong> that virtue and<br />

goodness pay far bigger dividends than wealth and high social standing.<br />

Crime and the Law<br />

Dickens work consistently looks at the injustices of the law and the system governing<br />

Victorian England and <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Expectations</strong> is no exception. The narrative starts with Pip<br />

meeting the ‘fearful’ criminal Magwitch who Pip fetches food and file for. We discover that<br />

despite Magwitch’s persecution and criminal history, he is far more noble than many of the<br />

other ‘law-abiding’ characters in the book. Dickens’ portrayal of Compeyson sharply<br />

compares the two. Compeyson, who destroys Miss Havisham psychologically, and is a far<br />

less ‘worthy’ character receives a lighter sentence as he looks like a gentleman.<br />

Additionally, Dickens use of the character of Jaggers demonstrates how the legal system<br />

can be unjust. Jaggers continually washes his hands, as if he is trying to wash off the guilt<br />

of the criminals he protects. Dickens clearly illustrates that in Victorian England some<br />

criminals were good men trapped by an unfair system, that lawyers were more concerned<br />

in their own best interest as opposed to seeing through justice, that punishment was not<br />

meted out fairly and that prison was an inhumane place.

Language in the Original Text<br />

Dickens uses language to deftly and efficiently draw highly detailed pictures of his<br />

characters, settings and narrative. He does this both in his narrative style, and in his use of<br />

dialogue. Below are two examples of this at work.<br />

Extract 1 – Dickens’ description of Mrs Joe (chapter 2)<br />

My sister, Mrs Joe, with black hair and eyes, had such a prevailing redness of skin that I<br />

sometimes used to wonder whether it was possible she washed herself with a<br />

nutmeg-grater instead of soap. She was tall and bony, and almost always wore a coarse<br />

apron, fastened over her figure behind with two loops, and having a square impregnable bib<br />

in front, that was stuck full of pins and needles.<br />

In two sentences Dickens is able to draw a clear character. What ostensibly is a description<br />

of her appearance actually gives the reader an insight into the personality of Mrs Joe. For<br />

example, ‘she washed herself with a nutmeg-grater instead of soap,’ illustrates a clear<br />

image for the reader but it also indicates the harshness and hardness of Mrs Joe’s<br />

character. The description of her apron, again to illustrate appearance, does much more as<br />

the description of the pins and needles denote her prickly personality and the ‘impregnable<br />

bib’ also hints at her own lack of children and maternal instinct.<br />

Extract 2: Miss Havisham and Joe speaking of Pip (chapter 13)<br />

‘You are the husband,’ repeated Miss Havisham, ‘of the sister of this boy?’<br />

… ‘Which I meantersay, Pip,’ Joe now observed in a manner that was at once expressive of<br />

focible argumentation, strict confidence, and great politeness, ‘as I hup and married your<br />

sister, and I were at the time what you might call (if you was anyways inclined) a single<br />

man.’<br />

‘Well!’ said Miss Havisham, ‘And you have reared the boy, with the intention of taking him<br />

for your apprentice; is that so, Mr Gargery?’<br />

‘You know Pip,’ replied Joe, ‘as you and me were ever friends, and it were look’d for’ard to<br />

betwixt us, as being calc’lated to lead to larks. Not but what, Pip, if you had ever made<br />

objections to the business – such as its being open to black and sut, or such-like – not but<br />

what they would have been attended to, don’t you see?’<br />

Dickens’ dialogue serves the dual purpose of moving the narrative forward as well as using<br />

it to give the reader a stronger understanding of the characters. In this extract the<br />

difference in the two characters is immediately apparent. The most notable being the use<br />

of accent for Joe, illustrating that he is not educated like Miss Havisham and showing the<br />

difference in their respective classes. Additionally, by looking at the sentence structure of<br />

Miss Havisham and Joe, we can also see the difference in their characters. Miss Havisham<br />

speaks in sharp complex sentences. She is to the point. Joe, conversely, also speaks in<br />

complex sentences but rather than being to the point he prevaricates, rambling on<br />

nervously to Miss Havisham. The use of punctuation aids in this. Joe’s use of dashes and<br />

brackets, and over use of commas compared to the pared down punctuation of Miss<br />

Havisham demonstrates this. Their tone of speaking is markedly different. Miss Havisham<br />

is imperious and Joe is deferential.

Characters<br />

Pip: The main character and narrator of the novel, Pip is a man that all through his young<br />

life tries to better himself because he is ashamed of who he is, and where he came<br />

from. When fortune falls in his lap, Pip is forced to realise that money does not make you<br />

happy, and that it cannot buy what he wants most, Estella's love, and the love of those he<br />

respects most.<br />

Joe: Pip's brother-in-law and father figure, Joe is the blacksmith with which Pip grew<br />

up. Though they are best friends and love each other, Joe represents all that Pip does not<br />

want out of his life, and so he pulls away from him as soon as fortune strikes. Pip later<br />

recognises that Joe’s goodness is worth more than money and they are reconciled.<br />

Mrs. Joe: A tyrannical sister and mother figure, Mrs. Joe raised Pip from the time his<br />

parents died when he was a baby until her accident. Abusive and prone to "rampages" of<br />

her temper, she appeared in the beginning to be an almost uncaring but authoritative<br />

figure.<br />

Uncle Pumblechook: Joe's uncle who introduces Pip to Miss Havisham. As a result of this,<br />

he looked at himself as Pip's real benefactor and when Pip came into wealth he wanted to<br />

use him for his own purposes.<br />

Biddy: Soft and sweet, Biddy was always one of Pip's best friends. When they were little,<br />

Biddy taught him all that she knew in school, and as they grew older she began to teach<br />

herself along with him. Biddy, like Joe, represents what is good and what Pip eventually<br />

aspires to. Pip wishes that he could love Biddy but never really does.<br />

Miss Havisham: Unhinged and bitter, having been jilted at the altar she is a woman whose<br />

broken heart has become cruel and malicious. Her only tender emotions she reserves for<br />

her ward, Estella, who she raises to break men’s hearts. She takes delight in Estella’s cruel<br />

treatment of Pip.<br />

Estella: Raised by Miss Havisham with a warped sense of reality Estella is cruel and cold.<br />

Estella follows her own journey throughout the novel and comes to realise that her<br />

behaviour and choices have led her down an unhappy path.<br />

Herbert: A young man with many dreams and aspirations, Herbert is kind and trustworthy.<br />

Even though at their first meeting as boys Herbert wanted to fight Pip. When Pip comes<br />

into fortune, Herbert becomes his best friend and beloved confidant.<br />

Matthew Pocket: Miss Havisham's cousin who is the only one in his family not after her<br />

fortune. Matthew is a kind and intelligent man who is a friend and teacher to Pip.<br />

Mr. Jaggers: The universal lawyer, Mr. Jaggers is a hard man who shows very little<br />

emotion. He bases his life on reason and fact. He acts as Pip’s guardian from when he<br />

leaves home until he comes into his inheritance. Jaggers handles Pip’s fortune and advises<br />

him when necessary.

Wemick: A clerk for Mr. Jaggers, at work Wemick appears to have no feelings. When Pip<br />

visits him at home however he is an entirely different person to whom Pip will go to for<br />

advice or companionship. Wemick takes care of his hearing impaired father, and in the end<br />

marries a woman, Miss Skiffins. His tiny house is his castle, and everything he has of value<br />

is "portable property."<br />

Abel Magwitch: A convict and Pip's benefactor, at different times in the story Magwitch is<br />

both villain and hero. After the loss of his daughter, Magwitch develops affection for the<br />

young boy who brings him food, brandy, and a file. Wanting the boy to be all he couldn't<br />

be, he devotes his life to making money and giving it to the boy to be a gentleman.<br />

Magwitch risks his life so he can see Pip, but his vengefulness shines through when he sees<br />

or talks of Compeyson.<br />

Bentley Drummle: Another student of Matthew Pocket’s, Drummle is a titled noble who is<br />

mistrustful and arrogant. Knowing that Pip has affection for her, Drummle courts Estella<br />

and taunts Pip with the knowledge. He later marries her but is an abusive husband.<br />

Orlick: Another of the villainous characters in the story, his jealousy of Pip dements<br />

him. Angry with Mrs. Joe for some offense that she committed, Orlick attacks her and tries<br />

to kill her. He later tries to kill Pip also but is thwarted. His diabolical mind and stupid<br />

demeanor makes for a perfect combination of evil stupidity that makes people not suspect<br />

him for his crimes.

Historical Context of the Original Text<br />

The Victorians<br />

For much of the last century the term Victorian, which literally describes things and events<br />

in the reign of Queen Victoria (1837-1901), conveyed connotations of "prudish,"<br />

"repressed," and "old fashioned." Although such associations have some basis in fact, they<br />

do not adequately indicate the nature of this complex, paradoxical age that was a second<br />

<strong>English</strong> Renaissance. Victorian England saw great expansion of wealth, power, and culture.<br />

Poor Law<br />

One of the most far-reaching pieces of legislation of the entire Nineteenth Century was the<br />

1834 Poor Law Amendment Act which abolished systems of poor relief that had existed<br />

since the passing of the Elizabethan Poor Law of 1601 . The new legislation established<br />

workhouses throughout England and Wales. It was extended to Ireland in 1838. Legislation<br />

for Scotland did not appear until 1845.<br />

Prior to the PLAA, poor relief took several forms based on the Elizabethan Poor Law of<br />

1601: outdoor relief was one type of relief where people would be given a 'dole' of money<br />

and remain in their own homes. The aged, infirm and sick were looked after either in<br />

almshouses, hospitals, poor houses or in their own homes. Orphans were looked after in<br />

orphanages. However, by the 1830s, many poor houses were vile and insanitary<br />

establishments; the sick were not nursed, children were not educated and paupers could<br />

starve to death in them.<br />

There was no single system of relief and no centralisation. However, all relief was based on<br />

the parish, the smallest unit of local government as well as the smallest ecclesiastical<br />

division. Some parishes were more generous than others in the amounts of relief they gave.<br />

The advantage of a parish based system was that 'everyone knew everyone else' and it was<br />

in the interests of all that the poor were looked after. The disadvantage was that the poor<br />

rates were borne by the same people who paid all other types of rates and from the<br />

outbreak of the French Wars (1793), poor rates tended to increase.<br />

Until around the beginning of the Nineteenth Century, poverty was accepted as a fact of<br />

life: at some point, most of the lower orders would suffer from poverty and would need<br />

help.<br />

Crime<br />

Due to poverty and under resourced policing, crime was rife in Victorian England. The<br />

following extract from The Victorian Web, outlines the types of crimes that were<br />

committed on an ongoing basis. The punishments for these crimes were usually severe,<br />

exportation to Australia and the death sentence among them. Additionally, people who<br />

found themselves in debt were sent to debtors prisons (Dickens’ father among them).<br />

Leaving aside drunkenness, theft was rampant. While children might pickpocket and steal<br />

from barrows on the streets, women might engage in shoplifting, and, as for London's sly<br />

con men, cheats, "magsmen" or "sharpers," they were notorious. So were the

housebreakers working in teams, and slipping into homes and shops and warehouses.<br />

Mugging, with its associated violence, was rife. A hanky dipped in chloroform might be<br />

used to subdue someone before robbing him, or a man's hat might be tipped over his face<br />

to facilitate the crime (this was called "bonneting"). Another ruse was to lure men down to<br />

the riverside by using prostitutes as decoys. The dupes would then be beaten up and<br />

robbed out of sight of passers-by. Violence could, of course, easily extend to murder.<br />

Prostitutes themselves ran uge risks. No one knows how many of them were strangled or<br />

stabbed or butchered (Jack the Ripper was far from the only villain). No respectable<br />

woman would have ventured forth after dark at all, if she had any choice in the matter. The<br />

helpless were at special risk. Well-turned-out children might be waylaid, dragged down an<br />

alley, and stripped of their finery, or pet dogs kidnapped for ransom or simply filched for<br />

their skins. Around mid-century, and again in 1862, "garrotting" or half-strangling unwary<br />

pedestrians from behind while accomplices stripped them of their valuables, caused great<br />

waves of panic. There were big-time criminals as well as gangs of street hooligans. In a new<br />

version of highway robbery, for instance, bankers' consignments might be snatched in<br />

transit. There was also a surge in gun crime in the 1880s, and hardened burglars<br />

"increasingly went armed".<br />

Class<br />

Class is a complex term, in use since the late eighteenth century, and employed in many<br />

different ways. Classes are the more or less distinct social groupings at any given<br />

historical period. Different social classes can be (and were by the classes themselves)<br />

distinguished by inequalities in such areas as power, authority, wealth, working and living<br />

conditions, life-styles, life-span, education, religion, and culture.<br />

Early in the nineteenth century the labels "working classes" and "middle classes" were<br />

already coming into common usage. The old hereditary aristocracy, reinforced by the new<br />

gentry who owed their success to commerce, industry, and the professions, evolved into an<br />

"upper class" which strongly maintained control over the political system, depriving not<br />

only the working classes but the middle classes of a voice in the political process. However,<br />

with the advent of the Corn Laws, the middle classes eventually were given the vote.<br />

The working classes, however, remained shut out from the political process, and became<br />

increasingly hostile not only to the aristocracy but to the middle classes as well. As the<br />

Industrial Revolution progressed there was further social separation.<br />

This basic hierarchical structure comprising the "upper classes," the "middle classes," the<br />

"Working Classes" and the impoverished "Under Class," remained relatively stable and a<br />

modified class structure clearly remains in existence today.<br />

Reference: www.victorianweb.org

Meet...Tariq Jordan who plays Pip<br />

1. Tell us a bit about your character, Pip<br />

Pip is a young inquisitive village boy from India, with a wild imagination. The play is set at<br />

the time of The Raj and he is asked to be a playmate for Miss Havisham’s adopted<br />

daughter. He falls in love with her and spends the rest of the play questioning his<br />

background and upbringing. You see the story through the eyes of Pip, who moves from his<br />

small village to the big city of Calcutta.<br />

2. What have been the challenges playing this role?<br />

As the play is seen through Pip’s eyes, he doesn’t really come off stage! The set changes<br />

around me whilst I am on stage, so having the stamina to play the role has been a<br />

challenge. Also Pip’s age ranges from 13 to 26 throughout the play, so I’ll go off stage and<br />

when I come back on it’s 5 years later!<br />

3. What made you want to be in this play?<br />

The challenges that presented themselves really made me interested in the play. The scope<br />

and emotional range of Pip is huge and I looked forward to the challenge of playing the<br />

different ages. There is also a cultural divide that I was interested in learning about.<br />

4. Did you have to do a lot of research?<br />

Yes quite a bit. I researched the time of the Raj quite thoroughly and looked at what life<br />

was like in India at that time. I find that pictures help me more than text, so I found as<br />

many pictures of India at that time as I could and tried to look at the physicality of the<br />

people in the pictures. You then just have to try it out in rehearsal! I try and trust that the<br />

writer has given you all the information you need in the script, it’s up to you to turn that<br />

into a believable character.<br />

5. How are rehearsals going?<br />

They’re going really well! We did a run of the first act yesterday, and we’re planning on<br />

running the whole show next week. I’m having an amazing time and enjoying every<br />

moment.<br />

6. What made you want to be an actor?<br />

I think the thing that made me want to be an actor was seeing Al Pacino’s Dog Day<br />

Afternoon. I loved that it was a film that looked like a play and was set in real time. The<br />

energy just seemed to leap out of the screen and I was amazed at the effect it had on the<br />

audience. I like the idea of taking the audience on a journey to another world. It’s just like<br />

playing - in fact it’s like the adult version of playing Cowboy’s and Indian’s as a child!<br />

7. How did you get into acting?<br />

I started at school, and then once I left I realised that I wanted to be an actor. It’s been a<br />

long journey. I started by going to open auditions for 1 line parts! After that I managed to<br />

get an agent and eventually I got this part, my first lead in a play. I also went to drama<br />

school, but not straight away. It took me 3 years to get in!<br />

8. What advice would you give to someone who wants to be an actor?<br />

If you really want it then go for it! Don’t give up - it’s not easy but it’s worth it. There are a<br />

million ways to get to the end goal, start small and then aim higher. Don’t forget that it’s<br />

good to dream...

Meet...The Designer, Colin Richmond<br />

1. Could you describe your role in this production?<br />

I design the set, costumes and props on the show. I work with stage management to create<br />

and source the props the actors use. I work with the costume department to help realise<br />

the costumes and with the builders, props makers and technical crew to help realise the set<br />

you see before you.<br />

2. How long does it take to design a show?<br />

It completely depends on the size of the show and the angle you are taking in your<br />

response to the text. But I’d say on average you can be thinking about a production up to<br />

9 months before curtain up. It then takes on average 4/5 weeks to rehearse it, again<br />

depending on the size of the piece and the number of actors involved. We would normally<br />

have a week of technical rehearsals and previews and then press night. So quite a long<br />

time.<br />

3. How did you get into this industry?<br />

I was always interested as a child in theatre and it carried on from there. I never realised<br />

that you could even train as a theatre designer but once I found out I applied, and was<br />

accepted at the Royal Welsh College of Music and Drama. I studied there for three years,<br />

gaining a first class BA Hons in theatre design, moved to London and tried to work my way<br />

into the theatre scene.<br />

4. What was the first show you ever designed?<br />

I did little bits and bobs at school and in a youth theatre I was involved in, but I was part of<br />

a team designing in theatre for a large scale puppetry project in college where we camped<br />

out in the grounds of a beautiful castle in Wales, just by the sea. Professionally I think the<br />

first real show I designed was an opera in Tuscany as part of the Batignano Opera<br />

Festival. It was called ‘ L’opera Seria’ directed by Rupert Goold. We were all staying in an<br />

old monastery in Tuscany on top of a hill in baking hot summer, and we were aiming<br />

towards putting this opera on in the cloister in the middle of the building. It was one of the<br />

most wonderful experiences and a fantastic start to anyone’s career.<br />

5. How have you worked with the director in developing your design concept?<br />

It’s very much a team effort. We have worked many times before, so you know how each<br />

other works. You need to build up trust. It’s hard in this industry because our jobs are<br />

very lonely ones at the best of times, so to have people to share your fears and problems<br />

whilst designing is so great, and most of the time that is the director who you turn to. We<br />

start by discussing ideas, concepts that might work for how the piece is written and take it<br />

from there. I’ll go away and sketch, research, model up a prelim design and then from<br />

there we look to finalising the design and set about presenting it to technical teams both on<br />

the tour and at the theatre in Watford.

6. How much does budget affect your design?<br />

Budget is a killer, especially these days and in this economic climate. The budgets get lower<br />

as purse strings get tighter for everyone, but the expectations get greater for the show as<br />

were all still keen to produce good work and maintain high standards and also get bums on<br />

seats. But it’s got very hard. So it’s a massive part of what you see. A lot of ideas get<br />

cut. It’s a game of compromise. But it’s the same the land over. It’s all part of the<br />

challenge, and sometimes produces a greater result.<br />

7. How do you decide what materials to use?<br />

For the set we decide this with the production manager and builders, and for the costumes<br />

these are decided with the costume supervisor.<br />

8. How do you go about designing costume?<br />

Research, and then draw up sketches for each character. These will change along the way<br />

and sometimes an actor’s physical shape dictates a lot of how the costume is interpreted<br />

from paper to body. Who owns what character often changes too throughout the<br />

rehearsal period so we need to be prepared for that. I then discuss at length with the<br />

costume supervisor what we perhaps hire/ buy/ make and they liaise with their crew as to<br />

how it is all realised. We have fittings with our actors and then the costumes are finished,<br />

and in a lot of cases broken down, to look old and dusty, dirty ,dyed etc….the process<br />

continues during the tech when things need to perhaps be altered to fit better, or for quick<br />

change purposes.<br />

9. When does your role start/stop?<br />

That’s a hard one to answer. It starts when you start reading the script and allowing<br />

yourself to think about it. It finishes officially after the press night.

Evaluating Live Performance<br />

Consider the following when watching the performance<br />

The Venue Geographical location, audience facilities, auditorium levels, any<br />

architectural/technical modifications<br />

Plot Summary What is the play about?<br />

OPC – Overall Was there any OPC in evidence? Your understanding of the OPC, methods<br />

Production used to communicate the OPC, any relevant material found in the<br />

Concept programme about the OPC, mood and atmosphere of the performance<br />

ODC – Overall What was the perceived ODC? Were the OPC and ODC appropriate to<br />

Design Concept each other?<br />

Dramatic Shape Tension, climax, anti-climax, suspense, form of production, tempo, and<br />

rhythm of whole production<br />

Spatial elements Actor/audience relationship, acting area, chosen stage form, audience<br />

sightlines<br />

Stage Action Entrances and exits, groupings, spatial patterns, proxemics, definition of<br />

location, symbolic areas of the stage<br />

Set (scenery) Realistic or non-realistic, use of flats, acting levels, screens/gauzes, units/<br />

structures, other scenic materials, stage properties, furniture, fabrics,<br />

textures<br />

Costume Relationship to OPC and ODC, period style and significance, fabric and<br />

texture, colour, symbolism, appropriateness to action, hand props, mask,<br />

make-up, quality and consistency of costuming, changes<br />

Props Significance, period<br />

Lighting Dramatic function, atmosphere and mood, colour, special effects, timing,<br />

intensity, technical competence, imaginative use<br />

Music and Dramatic function and means of creation, live sound effects, recorded<br />

Sound sounds or music, atmosphere and mood, period and style<br />

Special effects Pyrotechnics, smoke, multimedia images and live or recorded images<br />

Stylisation Naturalism, partial realism, expressionism, symbolic etc.<br />

Practitioners Evidence of the influence of other practitioners, artists, sculptors, filmmakers<br />

etc.

Casting Appropriateness, character demands, character relationships, doubling or<br />

casting combinations<br />

Characterisation Vocal: language, accent, mannerisms, volume, pace, pitch, tone, rhythms,<br />

pause, silence. Physical: posture, movement, pace, rhythm, mannerisms,<br />

use of hand props, costume, stillness, mime, use of space<br />

Audience Laughter, other vocal reactions, applause<br />

Reaction<br />

Structuring your written <strong>Theatre</strong> Evaluation<br />

Introduction<br />

Highlight the brief details of the production you saw: what, when, where, who (i.e. main<br />

cast, director, designer)<br />

Overview<br />

Give a brief account of your main impressions (e.g. how what you saw differed from your<br />

expectations)<br />

Main points<br />

A paragraph each, making sure that you include details from the production (production<br />

values) and that you analyse the effects of these details and that you evaluate them.<br />

Focus on key moments in the production. Make links between aspects of the production<br />

wherever possible (eg how the visual aspects relate to the performances of the actors).<br />

The number of paragraphs will vary, but four or five will probably be enough. Remember<br />

that you can also use diagrams with illustrations (make sure you annotate these).<br />

Final summing-up<br />

Keep this fairly brief and don’t just repeat previous information. You might, for example,<br />

focus on one key moment which (for you) summed up the whole approach to the<br />

production.<br />

Key points<br />

Most of your marks are from this section of your evaluation because it’s the longest and<br />

gives you most chance to fulfil the criteria. You may talk about key moments in the<br />

production, looking at the headings already given to you. Your choice of points will be<br />

decided by your own main impressions, and can include:<br />

Play’s central relationship<br />

Interpretation of main theme<br />

The effect of the ways in which the visual elements combine<br />

The acting style<br />

Specific major choices by the director (cutting / recording text etc)<br />

Actor/audience relations/hip (were you made to feel personally involved?)<br />

Remember: What? How? Why? How well?

Essay Questions<br />

Why is the play called <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Expectations</strong>? In what ways is this title relevant to Pip?<br />

How has the designer used set and costumes to create the world of <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Expectations</strong>?<br />

Discuss the theme of right and wrong, good and evil in <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Expectations</strong><br />

How does Dickens use settings to reflect characters in <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Expectations</strong>?<br />

Write about two incidents in <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Expectations</strong> which displays the productions ability to<br />

create atmosphere.<br />

Explore the development of Pip’s character in the opening scenes of <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Expectations</strong>.<br />

How is he affected by his initial encounters with Magwitch, Miss Havisham and Estella?<br />

How does the staging of <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Expectations</strong> reveal information about the characters?<br />

How does the set design and lighting impact the narrative in <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Expectations</strong>?<br />

How are each of the characters in <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Expectations</strong> made both memorable and striking?<br />

How is tension and fear created throughout <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Expectations</strong>?<br />

Consider the role and presentation of women and their influence on Pip in <strong>Great</strong><br />

<strong>Expectations</strong><br />

Discuss the themes of ambition and self-improvement in <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Expectations</strong><br />

Discuss how the audience is engaged in the opening scenes of <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Expectations</strong>

Further Reading and Contacts<br />

<strong>Great</strong> Directors At Work University of California Press<br />

The Empty Space Penguin<br />

Twentieth Century Actor Training Routledge