Paperskin: An introduction - Queensland Art Gallery

Paperskin: An introduction - Queensland Art Gallery

Paperskin: An introduction - Queensland Art Gallery

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

10<br />

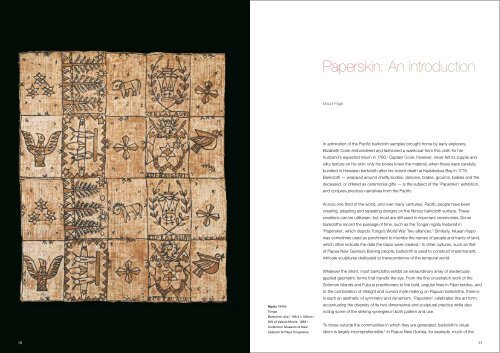

Ngatu 1940s<br />

Tonga<br />

Barkcloth, dye / 196.4 x 160cm /<br />

Gift of Valerie Morris, 1989 /<br />

Collection: Museum of New<br />

Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa<br />

<strong>Paperskin</strong>: <strong>An</strong> <strong>introduction</strong><br />

Maud Page<br />

in admiration of the Pacific barkcloth samples brought home by early explorers,<br />

elizabeth Cook embroidered and fashioned a waistcoat from this cloth for her<br />

husband’s expected return in 1780. 1 Captain Cook, however, never felt its supple and<br />

silky texture on his skin: only his bones knew the material, when these were carefully<br />

bundled in hawaiian barkcloth after his violent death at Kealakekua bay in 1779.<br />

barkcloth — wrapped around chiefly bodies, dancers, brides, grooms, babies and the<br />

deceased, or offered as ceremonial gifts — is the subject of the ‘<strong>Paperskin</strong>’ exhibition,<br />

and conjures precious narratives from the Pacific.<br />

Across one third of the world, and over many centuries, Pacific people have been<br />

creating, adapting and repeating designs on the fibrous barkcloth surface. These<br />

creations can be utilitarian, but most are still used in important ceremonies. some<br />

barkcloths record the passage of time, such as the Tongan ngatu featured in<br />

‘<strong>Paperskin</strong>’, which depicts Tonga’s World War Two alliances. 2 similarly, Niuean hiapo<br />

was sometimes used as parchment to inscribe the names of people and tracts of land,<br />

which often indicate the date the hiapo were created. 3 in other cultures, such as that<br />

of Papua New Guinea’s baining people, barkcloth is used to construct impermanent,<br />

intricate sculptures dedicated to transcendence of the temporal world.<br />

Whatever the intent, most barkcloths exhibit an extraordinary array of dexterously<br />

applied geometric forms that transfix the eye. From the fine crosshatch work of the<br />

solomon islands and Futuna practitioners to the bold, angular lines in Fijian textiles, and<br />

to the combination of straight and curved mark-making on Papuan barkcloths, there is<br />

in each an aesthetic of symmetry and dynamism. ‘<strong>Paperskin</strong>’ celebrates this art form,<br />

accentuating the diversity of its two-dimensional and sculptural practice while also<br />

noting some of the striking synergies in both pattern and use.<br />

To those outside the communities in which they are generated, barkcloth’s visual<br />

idiom is largely incomprehensible. 4 in Papua New Guinea, for example, much of the<br />

11

information in barkcloth designs is not meant to be shared with outsiders. The Omie<br />

women from Oro (or Northern) Province, on the country’s north-east coast, speak of<br />

the cloths as their ‘wisdom’ and, of the symbols in their works, will recount only those<br />

intended for outsiders. The titles of their nioje (barkcloths) refer to the rich, volcanic<br />

landscape that dominates their villages, including Mount lamington, mountains with<br />

clouds, jungle vines, tree bark, spider webs, frogs, and the backbones of mountain fish.<br />

Yet, each woman imagines this same landscape differently. some like Vivian Marumi<br />

can have entirely different interpretations of the same subject — one version of ‘jungle<br />

vines’ shows row upon row of symmetrically freehand horizontal lines as thick as a<br />

canopy. <strong>An</strong>other images this same jungle as chaotic and filled with spirals, diamond<br />

shapes and blocks of colour. This interpretive freedom is bountiful and produces an<br />

incredible diversity in barkcloths made within the same small, remote community.<br />

Australian writer Drusilla Modjeska spent time with these artists, and recounts that:<br />

When a woman comes into her vai hero (wisdom), it is not simply that she has learned<br />

the iconography, but that she lives it so fully that it forms, and informs, her relationship<br />

with the cloth. 5<br />

Modjeska’s engagement with the nioje, and her attempt to divulge customary<br />

knowledge of the work and practice to a Western audience, is evocative of how other<br />

barkcloth from the Pacific can be viewed:<br />

While the alphabet of motifs can be named, it is absorbed in such a way that parts do<br />

not require naming. The iconography works not by being broken into separate elements,<br />

but by a complex patterning of sensation and image that is not translatable — a way of<br />

seeing that is affective as well as instructive. 6<br />

As with much other Pacific barkcloth, the Omie’s nioje is a physical manifestation of<br />

the makers — who they are, their locality, their history and their cosmology. Titles<br />

of abstract works, such as ‘clan history’ and ‘wisdom’, allude to these textiles’<br />

genealogical memory. The Omie say their wisdom is intertwined with the wellbeing of<br />

12<br />

ABOVE<br />

Vivian Marumi<br />

Papua New Guinea b.1980<br />

Omie people, Oro Province<br />

Odunege 1 (Jungle vines 1) 2006<br />

Barkcloth, dye / 142 x 114cm /<br />

Purchased 2007. <strong>Queensland</strong> <strong>Art</strong><br />

<strong>Gallery</strong> Foundation<br />

RIGHT<br />

Vivian Marumi<br />

Odunege 4 (Jungle vines 4)<br />

(detail) 2006<br />

Barkcloth, dye / 163 x 99cm /<br />

Purchased 2007. <strong>Queensland</strong> <strong>Art</strong><br />

<strong>Gallery</strong> Foundation

Mount lamington. its eruption in 1951, the resulting deaths of 4000 of their Orokaivian<br />

neighbours and their own dislocation is interpreted as a consequence of the war on the<br />

Kokoda Trail which, among other horrors, grounded the dead soldiers’ restless spirits.<br />

some Omie blamed the eruption on the persistence of customary practices over those<br />

of Christianity, and proceeded to erase many of them. As a consequence, initiation<br />

ceremonies and the ensuing tattooing of clan insignia on the body ceased and designs<br />

were instead transposed to barkcloth. <strong>Art</strong>ist Nerry Keme has said, ‘i paint on barkcloth<br />

the designs that were on my grandparents’ bodies’. 7 These materialise on the nioje as<br />

three small concentric circles, repeated in several configurations across the textile, and<br />

were once confined to the area around the navels of her ancestors. in reviewing this<br />

dynamic transposition, Modjeska refers to these as ‘double skin’ designs.<br />

When speaking about barkcloth, the allusion to marked skin is particularly evocative<br />

and has been used in connection with other Pacific practices. <strong>An</strong>thropologist Alfred<br />

Gell noted that the Marquesans called their full-body tattoos pahu tiki, which translates<br />

as ‘wrapping in images’. researching samoan tattooing practices, he later concluded<br />

that they functioned as a second skin — wrapping, protecting and containing the<br />

person’s essence. The similarity of motifs from samoan tattoos to their siapo (barkcloth)<br />

is evident in works from the collection of Wellington’s Museum of New Zealand Te Papa<br />

Tongarewa, such as a 1940s example composed of horizontal rows of triangles. 8 Many<br />

Pacific peoples, most notably Tongans and Fijians, also wrap their bodies in barkcloth<br />

for important ceremonies. like tattooing, the cloth confers an entire matrix of meaning<br />

on the bearer. A drawing from 1877 shows a Fijian chief layered head to toe in masi with<br />

an accompanying description around that time, claiming that over 200 metres of cloth<br />

could be used for this purpose.<br />

There are many accounts of barkcloth being treated as an extension of the body — an<br />

extension of the skin. samoans would wrap barkcloth around the bride, and the material<br />

would then be ritually stained by the first intercourse. 9 Fijians rubbed turmeric on their<br />

The Tui Nadrau, dressed in masi<br />

for ceremonial presentation.<br />

Drawn from life by Theodor<br />

Kleinschmidt, Natuatuacoko,<br />

October, 1877 / Fiji Museum<br />

Collection<br />

Masi (detail) unknown<br />

Fiji<br />

Barkcloth, dye / 94.5 x 127.5cm /<br />

Collection: Museum of New<br />

Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa<br />

masi as well as on the bodies of a new mother and baby, binding them indistinguishably<br />

in this sweet-smelling, warm, earthy spice. likewise, the dead were also impregnated<br />

with turmeric and laid upon masi in their graves. 10 in 1920s Collingwood bay, Papua New<br />

Guinean women used to crawl around the village beneath a barkcloth when mourning<br />

their husbands, the cloth isolating them from sight and contact. 11<br />

Archaeologists Chris ballard and Meredith Wilson have posited a relationship between<br />

Melanesian rock art designs and those on tapa, specifically in mortuary contexts. The<br />

motifs, they argue, transfer between the two media and also appear in tattoos, carvings<br />

and engravings. 12 As ballard has said:<br />

Most of the rock art sites with tapa motifs are burial sites, with human remains in cliff<br />

niches or caves, and there are lots of instances of tapa being used to cover the bones,<br />

as a form of surrogate skin. 13<br />

Other scholars have also pointed to the link between designs found on ancient<br />

Pacific lapita pottery, tattooing and barkcloths, alluding to a complex aesthetic that is<br />

revitalised and used in a number of different art forms. 14 This ubiquitous transference<br />

of motifs can be understood as a method of communication (particularly as the Pacific<br />

region had no written language prior to european contact), and its continued use<br />

suggests an audience for whom these symbols represent a particular sense of being<br />

and place.<br />

For the baining people of the mountainous Gazelle Peninsula of New britain, Papua<br />

New Guinea, the creation of barkcloth masks enacts an intricate relationship with both<br />

their everyday agricultural subsistence and that of the spirits, particularly those of the<br />

recently departed. The ten baining masks in ‘<strong>Paperskin</strong>’ represent only a portion of the<br />

sculptures being made today, and include works from throughout the peninsula. 15 The<br />

masks are worn by men, with rare exceptions, such as the two Siviritki with fringes and<br />

accompanying fibre skirts that camouflage the dancer. each of the ten masks — except<br />

14 15

for the four-metre-high, three-pronged work — exhibit the baining characteristics of<br />

large, accentuated eyes, accompanied by vibrant designs painted directly onto the<br />

barkcloth in a restricted palette of red and black.<br />

These complex sculptures are used for a single ceremony and then discarded,<br />

even though they consume much of the villagers’ time and resources. The abstract<br />

designs featured on both sides are drawn mostly from memory, allowing for individual<br />

interpretation and change. Although customarily using designs drawn from nature —<br />

such as wild vines, insects or even pig intestines (the latter being a pattern used in<br />

several masks in ‘<strong>Paperskin</strong>’) — more recent designs include those derived from car<br />

tyre treads, mission crosses and manufactured cloth, as well as introduced figurative<br />

elements, such as flags and the ‘thumbs up’ gesture.<br />

The masks are produced for day or night ceremonies and represent female and male<br />

spirits in the form of animals or composite beings, such as bird–humans or snake–<br />

birds. Day dances are commonly associated with the commemoration of the dead and<br />

with the cyclical fertility of harvests and gardens, while night fire dances are thought to<br />

pertain to male initiation.<br />

A 1931 written account of a night fire ceremony is remarkably similar to more recent<br />

accounts, from the 1970s to the mid 2000s, as described by collector harold Gallasch.<br />

This points to the continued relevance of the practice despite the advent of modernity. 16<br />

each begins by noting the anticipation of the villagers following a long period of mask<br />

preparation, which occurs in locations inaccessible to women and children. Pigs are killed,<br />

food is distributed and a large bonfire ignited in the centre of the village. Gallasch recounts:<br />

. . . [A]t its zenith the chanting and drumming increased in tempo, as if in great<br />

urgency. Sweeping in from the blackness of the night, of the jungle, came the<br />

apparition of a bush spirit, a large white face outlined in red and black, large eyes to<br />

see in the darkness. As it came closer the disembodied face, shrouded behind the<br />

16<br />

ABOVE<br />

Kavat masks in performance,<br />

Malasaet village, East New Britain<br />

Province, Papua New Guinea,<br />

2009 / Image courtesy: John Wilson<br />

RIGHT<br />

Gabriel Asekia<br />

Papua New Guinea, b. Unknown<br />

Sibali Baining people, East New<br />

Britain Province<br />

<strong>An</strong>ui Lagun<br />

Papua New Guinea, b. Unknown<br />

Sibali Baining people, East New<br />

Britain Province<br />

Mandas mask c. 1995<br />

Barkcloth, dye, felt pen, cane /<br />

410 x174 x 40cm / Collection:<br />

Harold Gallasch, Hahndorf, South<br />

Australia<br />

17

18<br />

Kavat mask (front and back) 1971<br />

Papua New Guinea<br />

Kairak Baining people, East New<br />

Britain Province<br />

Barkcloth, paper, dye, felt<br />

pen, wood and cane / 135 x<br />

133 x 60cm / Purchased<br />

2009. <strong>Queensland</strong> <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong><br />

Foundation Grant.<br />

croton leaves, was propelled on black legs, pounding in time with the drumming,<br />

racing forwards, reversing, then stomping ever closer, the head swaying and<br />

pirouetting . . . children screamed in fear and ran to escape. In one last, swift burst<br />

of fervour, the masked apparition turned, raced and jumped in to the centre of the<br />

bonfire. There, for a few long seconds it stomped and twisted, burning sticks and<br />

embers scattering in all directions. 17<br />

The baining masks in ‘<strong>Paperskin</strong>’ bear the traces of their performance: soot from fires,<br />

and the remnants of dyes and oils used to paint and perfume the dancer’s skin.<br />

however, these masks are more than theatrical devices: they allow for an interaction<br />

with, and a continuation of, a specific cosmology. living in the Gazelle Peninsula in the<br />

1970s, theologians Karl hesse and Theo Aerts recorded that the ‘baining worldview<br />

accepts as it were two worlds, in which the other one (a rimbab) is the replica of this<br />

world’. 18 The invisibility of the rimbab becomes visible in the dances. Masked, their<br />

bodies adorned with paint and leaves, the dancers become the manifestation of spirits:<br />

They show the forces of nature — but at the same time also their limitations — the<br />

power of man, and the ambiguity of his relationship with that which is constantly<br />

beyond his immediate grasp. 19<br />

in many cultures across the Pacific, barkcloth continues to be significant. The<br />

deliberate repetition of geometric patterns has enabled a visual idiom historically linking<br />

barkcloth with other important cultural practices such as tattooing and weaving, as<br />

well as defunct art forms such as rock engravings and lapita pottery. recognition<br />

and appreciation of these designs has ensured the art form’s ongoing practice. On<br />

a fibrous surface, using a restricted colour palette and limited combinations of linear<br />

and curvilinear non-figurative designs, barkcloth makers have created extraordinarily<br />

diverse works that mediate the social and spiritual transformation of both individuals<br />

and groups.<br />

For some, the need to sustain this practice — to work communally, and to have goods<br />

to give and exchange — is so strong that, even when lacking the essential materials,<br />

they continue to innovate. in the mid 1990s in sydney’s west, for example, susana<br />

Kaafi gathered a group of women together to cut and glue interfacing material into long<br />

strips. laying them onto a large makeshift table in Kaafi’s backyard, they then painted<br />

the strips — using the dust scraped from red bricks — with the gridded emblems of the<br />

Tongan monarchy alongside stylised images of the sydney Opera house.<br />

Maud Page is Curator, Contemporary Pacific <strong>Art</strong>, <strong>Queensland</strong> <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong> / <strong>Gallery</strong> of Modern <strong>Art</strong>.<br />

19

ACKNOWleDGMeNT<br />

i would like to acknowledge the<br />

research and thoughtful input<br />

of ruth McDougall, Curatorial<br />

Assistant, Asian and Pacific <strong>Art</strong>,<br />

<strong>Queensland</strong> <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong> / <strong>Gallery</strong> of<br />

Modern <strong>Art</strong> to ‘<strong>Paperskin</strong>’.<br />

eNDNOTes<br />

1 Peter sharrad, ‘Trade and<br />

textiles in the Pacific and india’,<br />

in Diana Wood Conroy and<br />

emma rutherford, Fabrics<br />

of Change: Trading Identities<br />

[exhibition catalogue], university<br />

of Wollongong, NsW, p.14.<br />

2 see Adrienne Kaeppler,<br />

‘The structure of Tongan<br />

barkcloth design’, in Pacific<br />

<strong>Art</strong>: Persistence, Change and<br />

Meaning, <strong>An</strong>ita herle, Nick<br />

stanley, Karen stevenson and<br />

robert l Welsch (eds), Crawford<br />

house Publishing, hindmarsh,<br />

sA, 2002, pp.291–309.<br />

3 John Pule in John Pule and<br />

Nicholas Thomas, Hiapo:<br />

Past and Present in Niuean<br />

Barkcloth, university of Otago<br />

Press, Dunedin, 2005, p.47.<br />

4 simon Kooijman in his seminal<br />

and often quoted 1972 text on<br />

barkcloth, Tapa in Polynesia,<br />

thought that further study was<br />

needed on the names given to<br />

barkcloth patterns to decipher<br />

some of the meanings, but<br />

concluded that, ‘in the present<br />

state of our knowledge<br />

they have no interpretative<br />

significance’ and therefore did<br />

not include any. There has been<br />

some attempt at adding to this<br />

body of knowledge, but by and<br />

large, there remains remarkably<br />

little written information on<br />

barkcloth motifs across<br />

Polynesia and Melanesia.<br />

One pertinent example is rod<br />

ewins’s 1982 research on<br />

Fijian motifs (originally related<br />

to mats) and his more recent<br />

study of these in Staying Fijian:<br />

Vatulele Island Barkcloth and<br />

Social Identity, Crawford house<br />

Publishing, hindmarsh, sA,<br />

and university of hawaii Press,<br />

honolulu, 2009.<br />

5 Drusilla Modjeska, ‘This<br />

place, our art’, in Omie: The<br />

Barkcloth <strong>Art</strong> of Omie, [exhibition<br />

catalogue], <strong>An</strong>nandale Galleries,<br />

sydney, 2006, p.16.<br />

6 Modjeska, in Omie: The<br />

Barkcloth <strong>Art</strong> of Omie, p.16.<br />

rod ewins, speaking on Fijian<br />

masi (barkcloth), also states:<br />

‘Thus it is the totality of the<br />

pattern that gives meaning,<br />

and no one component of the<br />

pattern can carry more than a<br />

small part of the meaning by<br />

itself’, in Staying Fijian: Vatulele<br />

Island Barkcloth and Social<br />

Identity, p.147.<br />

7 Omie: The Barkcloth <strong>Art</strong> of<br />

Omie, p.29.<br />

8 Caption details: Siapo mamanu,<br />

samoa, barkcloth, dye / 173.5 x<br />

128.2cm / Collected by sir Guy<br />

richardson Powles c.1949–60.<br />

Gift of Michael Powles, 2001 /<br />

Collection: Museum of New<br />

Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa<br />

9 Nicholas Thomas, ‘The case<br />

of the misplaced ponchos:<br />

speculations concerning the<br />

history of cloth in Polynesia’,<br />

in Clothing the Pacific, Chloe<br />

Colchester (ed.), berg, Oxford,<br />

2003, p.90.<br />

10 simon Kooijman, Tapa in the<br />

Pacific, bernice P. bishop<br />

Museum bulletin 234, bishop<br />

Museum Press, honolulu,<br />

hawai‘i, 1972, p358.<br />

11 roger Neich and Mick<br />

Pendergrast, Pacific Tapa, David<br />

bateman, Auckland Museum,<br />

Auckland, 1997, p.136.<br />

12 Chris ballard, email to the<br />

author, 4 March 2009.<br />

13 rod ewins has also observed<br />

that human remains were<br />

found wrapped in black masi in<br />

a mortuary cave in Vanualevu,<br />

Fiji, in Staying Fijian: Vatulele<br />

Island Barkcloth and Social<br />

Identity, p.138.<br />

14 Most of Papua New Guinea,<br />

the outer islands and parts of<br />

the solomon islands have been<br />

inhabited for over 40 000 years.<br />

The rest of the Pacific was settled<br />

by speakers of Austronesian<br />

languages from south-east<br />

Asia approximately 4000 years<br />

ago. This expansion is marked,<br />

in particular, by the distinctive<br />

Barkcloth (detail) 19th century<br />

Papua New Guinea<br />

Doriri people, Oro Province<br />

Barkcloth, dye / 57.6 x 117.3cm /<br />

Collected by Captain F.R. Barton,<br />

1901. Donated 1966 / Collection:<br />

<strong>Queensland</strong> Museum<br />

pottery style known as lapita.<br />

15 it includes work by the simbali<br />

people in the south of the<br />

Gazelle Peninsula, the Chachet<br />

in the north-west, and the<br />

uramot and Kairak people in<br />

the central and central-east<br />

regions of the tip of this New<br />

britain island.<br />

16 see W.J. read, ‘A snake dance<br />

of the baining’, in Oceania,<br />

vol. 3, 1931–32, pp.232–37.<br />

17 harold Gallasch, letter to the<br />

author, 20 July 2009.<br />

18 Karl hesse and Theo Aerts,<br />

Baining Life and Lore, university<br />

of Papua New Guinea Press,<br />

Port Moresby, 1996, p.41.<br />

19 hesse and Aerts, Baining Life<br />

and Lore, p.41.<br />

20 21