EPHEMERIS NAPOCENSIS - Institutul de Arheologie şi Istoria Artei

EPHEMERIS NAPOCENSIS - Institutul de Arheologie şi Istoria Artei

EPHEMERIS NAPOCENSIS - Institutul de Arheologie şi Istoria Artei

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>EPHEMERIS</strong> <strong>NAPOCENSIS</strong><br />

XXII<br />

2012

ROMANIAN ACADEMY<br />

INSTITUTE OF ARCHAEOLOGY AND HISTORY OF ART CLUJ-NAPOCA<br />

EDITORIAL BOARD<br />

Editor: Coriolan Horaţiu Opreanu<br />

Members: Sorin Cociş, Vlad-Andrei Lăzărescu, Ioan Stanciu<br />

ADVISORY BOARD<br />

Alexandru Avram (Le Mans, France); Mihai Bărbulescu (Rome, Italy); Alexan<strong>de</strong>r Bursche (Warsaw,<br />

Poland); Falko Daim (Mainz, Germany); Andreas Lippert (Vienna, Austria); Bernd Päffgen (Munich,<br />

Germany); Marius Porumb (Cluj-Napoca, Romania); Alexan<strong>de</strong>r Rubel (Iași, Romania); Peter Scherrer<br />

(Graz, Austria); Alexandru Vulpe (Bucharest, Romania).<br />

Responsible of the volume: Ioan Stanciu<br />

În ţară revista se poate procura prin poştă, pe bază <strong>de</strong> abonament la: EDITURA ACADEMIEI<br />

ROMÂNE, Calea 13 Septembrie nr. 13, sector 5, P. O. Box 5–42, Bucureşti, România, RO–76117,<br />

Tel. 021–411.90.08, 021–410.32.00; fax. 021–410.39.83; RODIPET SA, Piaţa Presei Libere nr. 1,<br />

Sector 1, P. O. Box 33–57, Fax 021–222.64.07. Tel. 021–618.51.03, 021–222.41.26, Bucureşti,<br />

România; ORION PRESS IMPEX 2000, P. O. Box 77–19, Bucureşti 3 – România, Tel. 021–301.87.86,<br />

021–335.02.96.<br />

<strong>EPHEMERIS</strong> <strong>NAPOCENSIS</strong><br />

Any correspon<strong>de</strong>nce will be sent to the editor:<br />

INSTITUTUL DE ARHEOLOGIE ŞI ISTORIA ARTEI<br />

Str. M. Kogălniceanu nr. 12–14, 400084 Cluj-Napoca, RO<br />

e-mail: choprean@yahoo.com<br />

All responsability for the content, interpretations and opinions<br />

expressed in the volume belongs exclusively to the authors.<br />

DTP and print: MEGA PRINT<br />

Cover: Roxana Sfârlea<br />

© 2012 EDITURA ACADEMIEI ROMÂNE<br />

Calea 13 Septembrie nr. 13, Sector 5, Bucureşti 76117<br />

Telefon 021–410.38.46; 021–410.32.00/2107, 2119

ACADEMIA ROMÂNĂ<br />

INSTITUTUL DE ARHEOLOGIE ŞI ISTORIA ARTEI<br />

<strong>EPHEMERIS</strong><br />

<strong>NAPOCENSIS</strong><br />

XXII<br />

2012<br />

EDITURA ACADEMIEI ROMÂNE

SOMMAIRE – CONTENTS – INHALT<br />

STUDIES<br />

FLORIN GOGÂLTAN<br />

Ritual Aspects of the Bronze Age Tell-Settlements in the Carpathian Basin.<br />

A Methodological Approach .............................................7<br />

ALEXANDRA GĂVAN<br />

Metallurgy and Bronze Age Tell-Settlements from Western Romania (I) ............57<br />

DÁVID PETRUŢ<br />

Everyday Life in the Research Concerning the Roman Army in the Western European<br />

Part of the Empire and the Province of Dacia .................................91<br />

CORIOLAN HORAŢIU OPREANU<br />

From “στρατόπεδον” to Colonia Dacica Sarmizegetusa. A File of the Problem ........113<br />

CĂLIN COSMA<br />

Ethnische und politische Gegebenheiten im Westen und Nordwesten Rumäniens<br />

im 8.–10. Jh. n.Chr. ...................................................137<br />

ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND EPIGRAPHICAL NOTES<br />

AUREL RUSTOIU<br />

Commentaria Archaeologica et Historica (I) .................................159<br />

VITALIE BÂRCĂ<br />

Some Remarks on Metal Cups with Zoomorphic Handles<br />

in the Sarmatian Environment ............................................185<br />

FLORIN FODOREAN<br />

“Spa” Vignettes in Tabula Peutingeriana. Travelling Ad Aquas: thermal Water Resources<br />

in Roman Dacia .......................................................211<br />

DAN AUGUSTIN DEAC<br />

Note on Apis Bull Representations in Roman Dacia ...........................223<br />

SILVIA MUSTAŢĂ, SORIN COCIŞ, VALENTIN VOIŞIAN<br />

Instrumentum Balnei from Roman Napoca. Two Iron Vessels Discovered on the Site<br />

from Victor Deleu Street ................................................235<br />

IOAN STANCIU<br />

About the Use of the So-Called Clay “Breadcakes” in the Milieu of the Early Slav<br />

Settlements (6 th –7 th Centuries) ............................................253

DAN BĂCUEŢ-CRIŞAN<br />

Contributions to the Study of Elites and Power Centers in Transylvania during the second<br />

Half of the 9 th – first Half of the 10 th Centuries. Proposal of I<strong>de</strong>ntification Criteria Based<br />

on archaeological Discoveries .............................................279<br />

ADRIANA ISAC, ERWIN GÁLL, SZILÁRD GÁL<br />

A 12 th Century Cemetery Fragment from Gilău (Cluj County) (Germ.: Julmarkt;<br />

Hung.: Gyalu) ........................................................301<br />

ADRIAN ANDREI RUSU<br />

Stove Tiles with the Royal Coat of Arms of King Matthias I Corvinus ..............313<br />

REVIEWS<br />

IULIAN MOGA, Culte solare <strong>şi</strong> lunare în Asia Mică în timpul Principatului/Solar and Lunar Cults in<br />

Asia Minor in the Age of the Principate, Editura Universităţii “Alexandru Ioan Cuza” Iași (Iași<br />

2011), 752 p. (Szabó Csaba) .............................................327<br />

DAN GH. TEODOR, Un centru meşteşugăresc din evul mediu timpuriu. Cercetările arheologice <strong>de</strong> la<br />

Lozna-Botoşani/An Artisan centre from the Early Middle Ages. The archaeological research from<br />

Lozna-Botoşani, Bibliotheca Archaeologica Moldaviae XV, Aca<strong>de</strong>mia Română – Filiala Iași,<br />

<strong>Institutul</strong> <strong>de</strong> <strong>Arheologie</strong>, Editura Istros (Brăila 2011), 200 p. (including 118 figures), abstract<br />

and list of figures in French (Ioan Stanciu) ...................................331<br />

CĂLIN COSMA, Funerary Pottery in Transylvania of the 7 th –10 th Centuries, Series Ethnic and<br />

Cultural Interferences in the 1 st Millenium B.C. to the 1 st Millenium AD. 18, Romanian<br />

Aca<strong>de</strong>my – Institute of Archaeology and Art History Cluj-Napoca, Mega Publishing House<br />

(Cluj-Napoca 2011), 183 p., 49 plates (Aurel Dragotă) .........................339<br />

RESEARCH PROJECTS<br />

Crossing the Boundaries. Remo<strong>de</strong>ling Cultural I<strong>de</strong>ntities at the End of Antiquity in Central and Eastern<br />

Europe. A Case Study (Coriolan H. Oprean, Vlad-Andrei Lăzărescu) ...............343<br />

Warriors and military retainers in Transylvania of the 7 th –9 th centuries (Călin Cosma) .........349<br />

Seeing the Unseen. Landscape Archaeology on the Northern Frontier of the Roman Empire at Porolissvm<br />

(Romania) (Coriolan H. Oprean, Vlad-Andrei Lăzărescu) .......................352<br />

Abbreviations that can not be found in Bericht <strong>de</strong>r Römisch-Germanische Kommission .....363<br />

Gui<strong>de</strong>lines for “Ephemeris Napocensis” .........................................366

“SPA” VIGNETTES IN TABULA PEUTINGERIANA. TRAVELLING<br />

AD AQUAS: THERMAL WATER RESOURCES IN ROMAN DACIA 1<br />

Florin Fodorean 2<br />

Abstract: Tabula Peutingeriana is the most famous “map” of the Roman world. It represents the main<br />

Roman roads, the name of the cities with vignettes, representations of temples, and also edifices type “spa”.<br />

Our paper will start with some consi<strong>de</strong>rations regarding the thermal water resources in the Roman world.<br />

Then, we will present the main characteristics of the settlements represented with “spa” vignettes. Among<br />

them, three are in Roman Dacia. The most famous is the settlement from Germisara (today Geoagiu-Băi,<br />

Hunedoara County). This settlement was constantly visited in the Roman times, mainly because of the<br />

quality of the thermal waters, and due to its position, in the centre of the province. Marcus Statius Priscus,<br />

governor of Dacia Superior in 157 and 158 AD, is mentioned here in two votive monuments for the<br />

gods and the protectors of the thermal water. The next governor of Dacia Superior (in 161 AD), Publius<br />

Furius Saturninus, is also mentioned at Germisara in two votive inscriptions. This important character<br />

is mentioned in Dacia in 7 inscriptions. The thermal place was also visited by <strong>de</strong>curiones and quaestores<br />

from Sarmizegetusa and Apulum, augustales from Sarmizegetusa, soldiers from the auxiliary troops, a<br />

representative of a collegium Galatarum and another of a collegium aurariarum. The other two settlements<br />

were Ad Aquas (Călan) and Ad Mediam (Băile Herculane). So, we will explore the Roman Dacia and<br />

the Empire trying to un<strong>de</strong>rstand, perceive and <strong>de</strong>scribe, archaeologically and epigraphically, the resources<br />

of these thermal settlements.<br />

Keywords: spa vignettes, tourism, Roman Dacia, Ad Aquas, Germisara, Ad Mediam<br />

1. Into the Roman world. Natural resources: thermal waters<br />

It is hard today for us to un<strong>de</strong>rstand, in an era in which we make online reservations,<br />

fly by plain, ‘see’ using Google earth places we have never been, or schedule our time carefully,<br />

how other civilizations <strong>de</strong>veloped their perception concerning free time and the possibility to<br />

benefit of natural resources. But we would be surprised to see that, besi<strong>de</strong>s our technological<br />

means, Roman world was conscious about these things, too. The passion of the Romans for<br />

waters is famous 3 . It was transformed in exquisite, outstanding works of art. These were the<br />

aqueducts. Hundreds were built all over the Roman Empire. They were extremely sophisticated<br />

1 This article was written during my research stay in Germany, at the University of Erfurt. I received the<br />

support of the Fritz Thyssen Stiftung, which provi<strong>de</strong>d me a post-doctoral scholarship in 2011, therefore I express<br />

my gratitu<strong>de</strong> for Thyssen Foundation. I also want to thank prof. dr. Kai Bro<strong>de</strong>rsen, my supervisor in Germany, for<br />

all his constant help and support during my stay in Erfurt.<br />

2 Assistant professor, Ph. D, Babeş-Bolyai University Cluj-Napoca, Faculty of History and Philosophy, Department<br />

of Ancient History and Archaeology, Avram Iancu street, no. 11, Cluj-Napoca; e-mail: fodorean_f@yahoo.com.<br />

3 BLACKMAN/TREVOR 2001; DEMAN 2005; LANDELS 2000; TREVOR 2002.<br />

Ephemeris Napocensis, XXII, 2012, p. 211–221

212 Florin Fodorean<br />

constructions, built to remarkably fine tolerances, and of a technological standard that had a<br />

gradient (for example, at the Pont du Gard) of only 34 cm per km, <strong>de</strong>scending only 17 m vertically<br />

in its entire length of 50 km (31 miles). If this would not been enough, the Romans also<br />

were conscious about the advantages offered by the thermal waters. Using these hot springs, they<br />

built baths in Britannia (Bath and Buxton), in Gallia (Aix and Vichy), in Germania (Wiesba<strong>de</strong>n,<br />

Aachen), or in Pannonia Inferior (Aquincum) 4 . Some of these locations rapidly became<br />

important centers for recreational and social activities in Roman communities. Libraries, lecture<br />

halls, gymnasiums, and formal gar<strong>de</strong>ns became part of some bath complexes. In addition, the<br />

Romans used the hot thermal waters to relieve their suffering from diseases. The Roman bath<br />

inclu<strong>de</strong>d a far more complex ritual than a simple immersion. ‘Were the baths, then, and their<br />

concomitant aqueducts, a luxury?’ This question of Trevor 5 finds its answer easily: it <strong>de</strong>pends<br />

what we un<strong>de</strong>rstand today as ‘luxury’ and what Romans did un<strong>de</strong>rstood. In an advance civilization<br />

like the Roman Empire was, bath was not consi<strong>de</strong>red a luxury.<br />

2. Tabula Peutingeriana. Spa vignettes or thermal symbols<br />

Tabula Peutingeriana is the most representative piece of cartography of the Roman era.<br />

The map kept today in the National Library of Wien is a copy of another map created during late<br />

Roman era. The original can be dated in the fifth century AD. A long discussion <strong>de</strong>veloped within<br />

the historiography concerning the date of the original, with no concluding results even nowadays.<br />

Dozens of attempts were ma<strong>de</strong>. The original is a ‘compilation tardive’ 6 , was dated in the late third,<br />

fourth, fifth century AD, created in the third century and then completed with other data in the<br />

fourth and fifth centuries AD 7 , around 250 AD 8 , after 260 AD 9 , during Diocletian’s Tetrarchy<br />

(c. 300 AD) 10 , in 365–366 AD 11 , in between 402 and 452 AD 12 , in 435 AD 13 , ‘the fourth to fifth<br />

centuries’ 14 or, according to an attempting/speculative, but, unfortunately, not sufficient argued<br />

hypothesis, in the early nine century AD 15 . These attempts were based on the content of the map,<br />

the presence of certain cities and settlements (Rome, Constantinople, Antiochia 16 – personified<br />

vignettes; Ravenna, Aquileia, Nicaea, Nicomedia, Tessalonicae, Ancyra? – vignettes type ‘cities<br />

surroun<strong>de</strong>d by walls’), the mentioning of landscape <strong>de</strong>tails (silva Vosagus: 2A2–3, silva Marciana:<br />

2a4–3a1), the mentioning/non-mentioning of certain roads, the representation/non-representation<br />

of vignettes type ‘double-tower’, the signification of special vignettes/draws (Ad Sanctum<br />

Petrum, temple of Apollo in Antiochia). Suppositions about the author, place of production,<br />

method of creation, dimensions, purpose, role, sources used were also emitted.<br />

Dacia is represented in the segments VI and VII 17 . Five settlements are represented with<br />

double-tower vignettes: Tivisco, Sarmategte, Apula, Napoca and Porolisso. Ad Aquas is represented<br />

with a special vignette, corresponding to spas or thermal constructions. The other settlements,<br />

villages or mansiones are marked only with their names and the distance between them.<br />

4 YEGÜL 2010.<br />

5 TREVOR 2002, 6.<br />

6 CHEVALLIER 1997, 53–56.<br />

7 LEVI A./LEVI M. 1967.<br />

8 VON HAGEN 1978, 14.<br />

9 MANNI 1949, 30–31.<br />

10 TALBERT 2010, 136, 153.<br />

11 MILLER 1888; BOSIO 1983, agree with this date.<br />

12 WEBER 1999 (see http://www.christusrex.org/www1/ofm/mad/articles/WeberPeutingeriana.html#Web9).<br />

13 WEBER 1989, 113–17.<br />

14 SALWAY 2005, 131.<br />

15 ALBU 2005, 136–148; ALBU 2008, 111–19.<br />

16 LEYLEK 1993, 203–206.<br />

17 I prefer to use Weber’s system, who counted the 11 existing segments.

“Spa” Vignettes in Tabula Peutingeriana. Travelling Ad Aquas<br />

According to Talbert’s database 18 , there are 9 settlements with the name Ad Aquas<br />

(or <strong>de</strong>riving from it). These are: 1. Ad Aquas (segment grid 3C5 – IV 5 at Miller; with vignette);<br />

2. Adaquas (segment grid 4B3 – V 3/4 at Miller; no vignette); 3. Adaquas (segment grid 5C1 –<br />

VI 1 at Miller; vignette); 4. Adaquas (segment grid 5C3 – VI 3 at Miller; vignette) 19 ; 5. Ad aquas<br />

(segment grid 6A4 – VII 4 at Miller, no vignette); 6. Adaquas (segment grid 6A5 – VII 5 at<br />

Miller, vignette). This is the only settlement of this type mentioned in Dacia; 7. Adaquas Albulas<br />

(segment grid 4B5 – V 5 at Miller, no vignette); 8. Ad Aquas casaris (segment grid 3C4 – IV 4<br />

at Miller; vignette); 9. Ad aquas Herculis (segment grid 3C1 – IV 1 at Miller, vignette). These<br />

vignette usually <strong>de</strong>picts the same draw, a building drawn ‘à vol d’oiseaux’, quadrangular, with<br />

two front towers and a wall, and an inner yard. So, Tabula represents in Dacia with vignette only<br />

a thermal settlement: Adaquas, today Călan, Hunedoara County. But in the former province<br />

Dacia other two important settlements with thermal baths functioned: Germisara (Geoagiu<br />

Băi, Hunedoara County) and Băile Herculane (Fig. 1). So, a question arises: why these last two<br />

settlements mentioned do not appear in the famous Roman map with their specific vignettes?<br />

The answer is simple. Tabula is a selective map. The cartographer was forced by his support<br />

(a parchment roll of 7 m length and 34 cm high) to select the information, as a cartographer<br />

today, <strong>de</strong>pending on the scale, reduces and selects the main cartographic elements of a map,<br />

according to the well known principle of cartographic generalization. In the following, we will<br />

present data based on antique sources and archaeological researches, which will provi<strong>de</strong> information<br />

about the importance of these thermal settlements.<br />

Fig. 1. Thermal settlements in Roman Dacia.<br />

18 See: http://www.cambridge.org/us/talbert; http://peutinger.atlanti<strong>de</strong>s.org/map-a, also http://omnesviae.org.<br />

19 One should notice the interesting way or mentioning the distance from this Adaquas to the next settlement,<br />

Tacapae: aB AQVIS TACAPA MILIA XVI. See: http://www.cambridge.org/us/talbert/talbertdatabase/TPPlace226.<br />

html. This kind of indication is the basic formula found in the inscriptions from the milestones.<br />

213

214 Florin Fodorean<br />

3. Germisara – the ‘five stars’ thermal accommodation in Roman Dacia<br />

The area between Geoagiu Valley, in the East, the village of Geoagiu in the South and<br />

the locality Geoagiu-Băi was named in the Roman era Germisara 20 . The toponym is of Dacian<br />

origin. Archaeologically and topographically, the Roman city and the Roman fortress were<br />

exten<strong>de</strong>d on the territory of the current village of Geoagiu, in the East, and Cigmău in the<br />

West. So, we can distinguish two points situated on the northern, right bank of Mureş, close to<br />

the main military road that connected Ulpia Traiana Sarmizegetusa with Apulum. One of these,<br />

which took advantage of the thermal waters, had a civilian character. This place is situated North<br />

of Geoagiu. The other, which <strong>de</strong>veloped a little later, had a military character and inclu<strong>de</strong>d the<br />

Roman fortress from Cigmău and the civilian settlement (vicus militaris). We can say that un<strong>de</strong>r<br />

the name of Germisara three areas have functioned in the Roman era: 1. the Roman camp<br />

from Cigmău, situated on the “Turiac” plateau, at “Pogradie” point; 2. the civilian settlement<br />

(vicus militaris), placed between Cigmău and Geoagiu; 3. the thermal settlement, approximately<br />

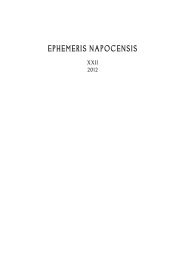

positioned 5 km North of the Roman fortress 21 (Fig. 2).<br />

Tabula Peutingeriana places Germigera along the imperial Roman road Sarmizegetusa<br />

– Apulum, between Petris (Uroiu) and Blandiana (Vinţu <strong>de</strong> Jos), at IX m(illia) p(assuum) away<br />

from both of these settlements. Between the military fortress from Cigmău and the thermal<br />

settlement a Roman road was i<strong>de</strong>ntified and investigated in 2002–2003 22 . As I noticed above,<br />

Germisara is not represented in Tabula with the specific vignette for thermal buildings. Instead,<br />

Ad Aquas (today Călan, Hunedoara County) is <strong>de</strong>picted with the specific vignette. The explanation<br />

relies on the fact that Germisara was famous as thermal settlement in Roman Dacia, but<br />

its position, north to the main road Sarmizegetusa – Apulum, <strong>de</strong>termined the mapmaker, using<br />

the same principle of selecting the information, not to represent it with vignette.<br />

The remains of the Roman spa are visible today. They are situated west of the current<br />

thermal complex. The Romans were extremely pragmatic. This is the reason why here they<br />

literally excavated the travertine promontory and created an outstanding, open air, system<br />

of basins, on a circular surface of circa 90–95 m. During time, besi<strong>de</strong> this, numerous other<br />

artifacts were discovered: 1. a temple <strong>de</strong>dicated to Nymphae 23 ; 2. statues representing the divinities<br />

of health protection (Aescupalius and Hygia, Hercules); 3. seven gold votive plates found in<br />

the nimphaeum 24 ; 4. a marble statue representing Diana; 5. small finds, mainly coins. Besi<strong>de</strong><br />

these, we are aware of the importance of this place if we analyze the Roman inscriptions found<br />

here. These are published in IDR III/3, no. 230–247 (votive inscriptions). Some of them were<br />

raised by very important persons involved in the administration of Dacia Superior.<br />

Marcus Statius Priscus 25 , governor of Dacia Superior in 157–158 AD, is mentioned at<br />

Germisara in two votive monuments for the gods and the protectors of the thermal waters 26 .<br />

He began his career as an equestrian officer, receiving a <strong>de</strong>coration from Hadrian during<br />

the Jewish rebellion. He then served as procurator in Southern Gaul before being ma<strong>de</strong> a<br />

senator and commanding two legions in succession. Priscus was in charge of Dacia as a governor<br />

between 157 and 158 AD. He held the consulship in 159. After this, he governed Moesia<br />

Superior in 160–161 and became governor of Roman Britain immediately afterwards, serving<br />

until perhaps as late as the mid 160 s .<br />

20 See, for a short presentation, IDR III/3, 211–13.<br />

21 PESCARU A./PESCARU E. 2001, 439–52; WOLLMANN 1968, 109–20.<br />

22 FODOREAN/URSUŢ 2001, 203–20; FODOREAN 2006, 257–65.<br />

23 On the cult of Nymphae in Roman Dacia: GHINESCU 1998, 123–44.<br />

24 PESCARU 1988–1991, 664–66.<br />

25 On this character: URLOIU 2010, 65–66.<br />

26 IDR III/3, 240, 241. RUSU 1988–1991, 653–56; RUSU/PESCARU 1995, 33.

“Spa” Vignettes in Tabula Peutingeriana. Travelling Ad Aquas<br />

Fig. 2. Geoagiu<br />

Publius Furius Saturninus 27 was also the governor of Dacia Superior in 160 He may<br />

have visited the thermal settlement, since two inscriptions with his name mentioned were found<br />

here 28 . In IDR III/3, 232 Saturninus <strong>de</strong>dicates this votive altar to the health gods, obviously<br />

after a pleasant voyage here at Germisara, and an efficient thermal treatment, as one who entirely<br />

benefited of the healing powers of the thermal waters.<br />

Besi<strong>de</strong> these two important persons, governors of Dacia Superior, monuments mention<br />

other people who visited this place and <strong>de</strong>dicated inscriptions. One of these monuments is IDR<br />

III/3, no. 233 29 . This votive altar, raised for the health of the three emperors (Septimius Severus,<br />

Aurelius Antoninus – Caracalla and Septimius Geta) was placed here from the or<strong>de</strong>r of the governor<br />

of the three Dacian provinces, Lucius Octavius Iulianus around 200–201 AD. The person <strong>de</strong>signated<br />

to fulfill this or<strong>de</strong>r was the comman<strong>de</strong>r of the auxiliary unit of cavalry Ala Asturum.<br />

Aurelius Crhestus, a Roman citizen with Roman gentilicium (Aurelius) and a Greek<br />

cognomen, also <strong>de</strong>dicated an inscription for the health gods 30 . The members of the collegium<br />

Galatarum (citizens who came in Dacia from Asia Minor) <strong>de</strong>dicate an inscription pro salute<br />

imperatoris to Hercules Invictus 31 . The members of collegium Aurariarum, with their representing<br />

27 PISO 1972, 463–471.<br />

28 IDR III/3, 232; IDR III/3, 236.<br />

29 Votive altar, fragmentary kept (broken in the right si<strong>de</strong>), the camp of inscription is <strong>de</strong>teriorated in the center by<br />

a ‘circle’ shape, obviously a mo<strong>de</strong>rn intervention ma<strong>de</strong> by a person who wanted to use the monument for a purpose.<br />

Its dimensions are: 100 × 52 × 46, with letters of 4 cm height. The monument was discovered in a point situated north<br />

of Geoagiu Băi, on the left si<strong>de</strong> of the Geoagiu valley. It was kept for a while in the medieval castle Kuun, where it was<br />

i<strong>de</strong>ntified and copied by A. Fodor. Text: Fortuna[e]/pro salute/aug(ustorum) n(ostrorum) (trium]/L(ucius) Octavius I[u]/lianus<br />

co(n)s(ularis) II[I]/Dac(iarum) fieri iussit/instante … L Ge– (?)/M A N T [p]rae[f(ecto) a]lae/Astu[rum_ _ _ _] B. Translation:<br />

‘To (the god<strong>de</strong>ss) Fortuna, for the health of our three augusti, Lucius Octavius Iulianus, consular of the three Dacia,<br />

or<strong>de</strong>red for this (monument), it took care for (this monument) Aelius Geminus (?), praefectus alae Asturum _ _ _ _’.<br />

30 IDR III/3, 231.<br />

31 IDR III/3, 234.<br />

215

216 Florin Fodorean<br />

person, Lucius Calpurnius, <strong>de</strong>dicate another inscription to Jupiter, also pro salute imperatoris 32 .<br />

An officer (centurio) from legio V Macedonica <strong>de</strong>dicates an altar to Jupiter 33 . All these examples<br />

show that Germisara was intensively visited.<br />

Maybe the most interesting example to sustain what we already highlighted above is the<br />

inscription IDR III/3, 243. This is a votive altar i<strong>de</strong>ntified by the middle of the XVI th century in<br />

Orăştie, where the text was copied by M. Singler. The <strong>de</strong>dicant, a signifer from the military trooped<br />

garrisoned in Cigmău, close to Germisara, raises the monument because he escape the danger of <strong>de</strong>ath<br />

maybe after he benefited of the qualities of the thermal waters. The inscription dated from 186 AD.<br />

4. Ad Aquas (Călan)<br />

This settlement is represented in Tabula Peutingeriana with vignette. Călan is positioned<br />

on the left bank of the Strei River, at the altitu<strong>de</strong> of 230 m. The thermal water resources are<br />

positioned circa 2 kilometers north of the current city (Fig. 3). During Roman times, the same<br />

point was positioned exactly along the main imperial road of the province. The settlement had<br />

the status of pagus, as the inscriptions prove (pagus Aquensis).<br />

Archaeologically, today we can still visit the Roman basin, directly cut in the rock 34 .<br />

It encloses a total perimeter of circa 94 m (length of 14.2 m, width of 7.2 m and a <strong>de</strong>pth of 4 m).<br />

The water source is still active today. The water of these sources has an average temperature of<br />

23°–24°. Epigraphically, we know that this settlement was also intensively visited in the Roman<br />

era. Six inscriptions are published in IDR III/3 (no. 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11). Among those who came<br />

here, we mention Quintus Decius Vin<strong>de</strong>x, financial procurator of Dacia Superior. He erected<br />

a monument for Fortunae Augustae 35 . Another important character who visited Ad Aquae was<br />

Caius Iulius Marcianus, <strong>de</strong>curion in Ulpia Traiana Sarmizegetusa and also member in the administrative<br />

staff of pagus Aquensis.<br />

5. Ad Mediam – Băile Herculane<br />

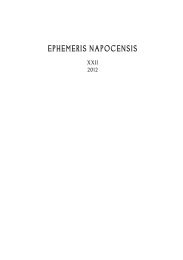

The third point on the map of Roman Dacia with thermal waters is Băile Herculane 36 .<br />

During Roman times it was also intensively visited. The name of the settlement also appears in<br />

the work of the Anonymous of Ravenna (Medilas). The Roman ruins were discovered during<br />

the 18 th century (Fig. 4). During the Habsburgic and Austro-Hungarian Empire the name of<br />

the settlement was Herkulesbad/Herkulesfürdő.<br />

The discoveries consist of water pipes, basins, public and private buildings, sanctuaries,<br />

altars with inscriptions <strong>de</strong>dicated to the gods of the health, statues of divinities and votive reliefs,<br />

funerary inscriptions, reliefs and funerary monuments, sarcophagi, stamped tiles of several<br />

military troops (legio VII Claudia, XIII Gemina, IV Flavia Felix), coins. Roman Ad Mediam was<br />

a totally different settlement, separated from the military fortress from today’s Mehadia, where<br />

cohors III Delmatarum was garrisoned. Only from 1817 the settlement received an official<br />

name. In 1736 begins the reconstruction and the mo<strong>de</strong>rnization of the ‘baths’. Most of the new<br />

buildings carry the imprint of an impressive Austrian Baroque style. The thermal settlement is<br />

visited by important people: emperor Josef II, Emperor Francis I, emperor Franz Josef. In 1852,<br />

Herculane was consi<strong>de</strong>red the most beautiful thermal settlement of Europe. Numerous inscriptions<br />

are <strong>de</strong>dicated to Hercules, which was the protector of the thermal waters 37 .<br />

32 IDR III/3, 235.<br />

33 IDR III/3, 237.<br />

34 RUSU/PESCARU 1996, 23–24.<br />

35 IDR III/3, 7.<br />

36 BOZU/MICLI 2005, 123–42.<br />

37 19 inscriptions published in IDR III/1 (no. 54 to 68).

“Spa” Vignettes in Tabula Peutingeriana. Travelling Ad Aquas<br />

One of the most interesting inscriptions found in Băile Herculane is a votive altar of<br />

marble, 73 × 37 × 30 cm. The base and the upper part have an elegant, symmetric shape. This<br />

monument stood a while actually built in the wall of the bridge over the Cerna River, within<br />

the thermal settlement 38 . This is an outstanding example with direct reference to the healing<br />

38 IDR III/1, no. 55.<br />

217

218 Florin Fodorean<br />

powers of the thermal waters from Băile Herculane. After a long infirmitas, a husband raises<br />

here an altar for the gods of health, specifically mentioning the she was cured ‘through the<br />

power of the thermal waters’.<br />

That Băile Herculane was intensively visited during Roman times is no longer a new fact.<br />

This is proved by the inscriptions 39 . Numerous soldiers are mentioned. For example, IDR III/1,<br />

54, is a votive altar, of marble, discovered in the XVIIIth century in Băile Herculane and during<br />

the same century transported at Viena. Now is kept in the Nationalbibliothek. The <strong>de</strong>dicant<br />

Marcus Aurelius Veteranus was praefectus in the legion XIII Gemina from Apulum. He came<br />

here to benefit of the qualities of the thermal waters. Another interesting inscription is a votive<br />

altar, discovered in 1736 40 . As recognition at the end of their long journey from Ulpia Traiana<br />

Sarmizegetusa to Rome, the <strong>de</strong>legates, who formed the provincial embassy of Dacia, erected<br />

at Băile Herculane this altar. They travelled to Rome to participate to the ceremony of installation<br />

of Marcus Sedatius Severianus in his consulship. Before that, he was the legatus legionis<br />

of the legion V Macedonica at Troesmis. After his mission in Apulum en<strong>de</strong>d, when he return<br />

to Rome (in 153 AD) the Dacian <strong>de</strong>legates go to Rome. Returning back in the province, they<br />

erected this monument as an expression of gratitu<strong>de</strong> because they returned safe home.<br />

Fig. 4. Băile Herculane.<br />

39 Numerous monuments are <strong>de</strong>dicated for Hercules: IDR III/1, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68.<br />

40 IDR III/1, 56: Text: Dis et Numinib(us)/Aquarum/Ulp(ius) Secundinus/Marius Valens/Pomponius<br />

Haemus/Iul(ius) Carus Val(erius) Valens/legati Romam ad/consulatum Seve/riani c(larissimi) v(iri) missi incolu/<br />

mes reversi ex voto/E A. Translation: ‘To the gods and to the holy powers of waters, Ulpius Secundinus, Marius<br />

Valens, Pomponius Haemus, Iulius Carus, Valerius Valens, <strong>de</strong>legates send to Rome to the consulship of Severianus,<br />

clarissimus vir, returned (home, in Dacia), safe, released the vow freely, as is <strong>de</strong>served’.

“Spa” Vignettes in Tabula Peutingeriana. Travelling Ad Aquas<br />

6. Concluding remarks. The thermal settlements and the road system<br />

Germisara, Ad Aquas and Ad Mediam represent three important Roman thermal settlements<br />

from Dacia. It is obvious, from what I presented above, that all three were intensively<br />

visited. These points of attractions offered for the inhabitants the opportunity, the chance for<br />

healing, but they also were perceived as touristic settlements. These ‘resorts’ offered what the<br />

Romans borrowed from Greeks: the concept of leisure as a state of mind. They all were connected<br />

to the road infrastructure of roads. Germisara was positioned 7 kilometers north of the main<br />

roads of Dacia and connected with another road, well preserved even nowadays. Ad Mediam<br />

was positioned 5 kilometers east of the road which connected Dierna (today Orşova, Mehedinţi<br />

County). The toponym itself indicates a settlement positioned close to the middle part of this<br />

road. Ad Aquas (Călan, Hunedoara County) was located along the main road of Roman Dacia,<br />

which connected the Danube line with the northern parts of Dacia, via Le<strong>de</strong>rata – Tibiscum<br />

– Ulpia Traiana Sarmizegetusa – Apulum – Potaissa – Napoca – Porolissum. This road was the<br />

‘highway’ of Roman Dacia. It was built during the two military camapaigns of Trajan in Dacia<br />

and finished immediately after the conquest. A Roman milestone discovered at Aiton (between<br />

Potaissa – today Turda, Cluj County, and Napoca, today Cluj-Napoca, Cluj County) dated in<br />

108 AD, during Trajan, <strong>de</strong>monstrates that the Romans succee<strong>de</strong>d to built this road up to the<br />

northern parts of the province.<br />

Using the infrastructure, and all the facilities created, including a rapid colonization<br />

of the new province (Eutropius, Breviarum ab urbe condita, 8, 6: Traianus victa Dacia ex toto<br />

urbe Romano infinitas copias hominum transtulerat ad agros et urbes colendas), people of all social<br />

statuses (soldiers, functionaries of the states) started to travel, to communicate, to benefit of all<br />

the advantages of the new province. The society of Roman Dacia (as well as of the whole Roman<br />

Empire) became very dynamic. These three thermal settlements were very attractive, as the<br />

archaeological finds and inscriptions inform us. Communication, as an essential element for any<br />

civilization, was done ‘physically’ by infrastructure, which provi<strong>de</strong>d opportunities for goods and<br />

people to travel and organize a territory. Communication also meant the possibility for people<br />

to travel, to interact, to exchange information.<br />

My examples, together with others already known from other provinces, are strong<br />

evi<strong>de</strong>nces to contradict with solid arguments the old concepts spread in the historiography,<br />

according to which the Roman Empire was a space of static communities. On the contrary, we<br />

discover, step by step, the huge resources of the Roman Empire and how people interacted with<br />

themselves and with the landscape.<br />

ABBREVIATIONS AND BIBLIOGRAPHY<br />

IDR<br />

Inscriptiones Daciae Romanae (București)<br />

ALBU 2005<br />

E. ALBU, Imperial Geography and the Medieval Peutinger Map. Imago Mundi 57, 2005,<br />

136–148.<br />

ALBU 2008<br />

E. ALBU, Rethinking the Peutinger Map. In: R. J. A. Talbert/R. W. Unger (Eds.), Cartography<br />

in Antiquity and Middle Ages: Fresh Perspectives, New Methods (Lei<strong>de</strong>n 2008), 111–119.<br />

BLACKMAN/TREVOR 2001<br />

D. R. BLACKMAN/A. H. TREVOR, Frontinus’ Legacy: Essays on Frontinus’ <strong>de</strong> aquis urbis<br />

Romae (Michigan 2001).<br />

219

220 Florin Fodorean<br />

BOSIO 1983<br />

L. BOSIO, La Tabula Peutingeriana: una <strong>de</strong>scrizione pittorica <strong>de</strong>l mondo antico (Rimini 1983).<br />

BOZU/MICLI 2005<br />

O. BOZU/V. MICLI, Edificii publice și amenajări termale romane pe un plan al staţiunii Băile<br />

Herculane din 1774. Patrim. Banaticum 4, 2005, 123–142.<br />

CHEVALLIER/DEMAN 2005<br />

R. CHEVALIER/E. B. DEMAN, Les voies romaines, 2 nd ed. (Paris 2005).<br />

DEMAN 2005<br />

E. B. DEMAN, The Building of the Roman Aqueducts (Washington 2005).<br />

FODOREAN 2006<br />

FL. FODOREAN, Drumurile din Dacia romană (Cluj-Napoca 2006).<br />

FODOREAN/URSUŢ 2001<br />

FL. FODOREAN/D. URSUŢ, The via silica strata Geoagiu-Băi – Cigmău. Archaeological,<br />

geo-topographic and technical study. Acta Mus. Napocensis 38/1, 203–220.<br />

GHINESCU 1998<br />

I. GHINESCU, Cultul nimfelor în Dacia romană. Ephemeris Napocensis 8, 1998, 123–144.<br />

LANDELS 2000<br />

G. J. LANDELS, Engineering in the Ancient World (Berkeley/Loss Angeles 2000).<br />

LEVI A./LEVI M. 1967<br />

A. LEVI/M. LEVI 1967, Itineraria picta. Contributo allo studio <strong>de</strong>lla Tabula Peutingeriana<br />

(Rome 1967).<br />

LEYLEK 1993<br />

E. LEYLEK, La vignetta di Antiochia e la datazione <strong>de</strong>lla Tabula Peutingeriana. Journal Ancient<br />

Topogr. 3, 1993, 203–206.<br />

MANNI 1949<br />

E. MANNI, L’impero di Gallieno. Contributo all storia <strong>de</strong>l terzo secolo (Roma 1949).<br />

MILLER 1888<br />

K. MILLER, Die Peutingerische Tafel (Ravensburg) [expan<strong>de</strong>d edition 1916; reissued 1929 and<br />

1962] (Stuttgart).<br />

PISO 1972<br />

I. PISO, Publius Furius Saturninus. Acta Mus. Napocensis 9, 463–471.<br />

PESCARU A./PESCARU E. 1988–1991<br />

A. PESCARU/E. PESCARU, Încă o plăcuţă votivă din aur <strong>de</strong>scoperită la Germisara (Geoagiu-<br />

Băi). Sargetia 21–24, 1988–1991, 664–666<br />

PESCARU A./PESCARU E. 2001<br />

A. R. PESCARU/E. PESCARU, Complexul termal roman Germisara. Faze și etape<br />

<strong>de</strong> amenajare”. In: G. Florea/G. Gheorghiu/E. Iaroslavschi (Eds.), Studii <strong>de</strong> istorie antică.<br />

Omagiu profesorului Ioan Glodariu. Bibl. Mus. Napocensis 20 (Cluj-Napoca/Deva), 439–452.<br />

RUSU 1988–1991<br />

A. RUSU, Marcus Statius Priscus la Germisara. Sargetia 21–24, 1988–1991, 653–656.<br />

RUSU/PESCARU 1995<br />

A. RUSU/E. PESCARU, Geoagiu Băi (complexul termal Germisara), jud. Hunedoara.<br />

In: Cronica Cerc. Arh. Campania 1994 (București 1995), 33.<br />

RUSU/PESCARU 1996<br />

A. RUSU/E. PESCARU, Călan Băi – Aquae, jud. Hunedoara. In: CCA. Campania 1995<br />

(București 1996), 23–24.<br />

SALWAY 2005<br />

B. SALWAY, The Nature and Genesis of the Peutinger Map”. Imago Mundi 57, 2005, 119–135.<br />

URLOIU 2010<br />

R. URLOIU, Cavaleri promovaţi în ordinal senatorial în secolul Antoninilor. Analele Univ.<br />

Creştine “Dimitrie Cantemir”. Ser. Istor. 1/1, 2010, 53–78.<br />

VON HAGEN 1978<br />

W. VON HAGEN, Le gran<strong>de</strong> stra<strong>de</strong> di Roma nel mondo (Roma 1978).

“Spa” Vignettes in Tabula Peutingeriana. Travelling Ad Aquas<br />

TALBERT 2010<br />

R. J. A. TALBERT, Rome’s World. The Peutinger map reconsi<strong>de</strong>red (Cambridge 2010).<br />

TREVOR 2002<br />

H. A. TREVOR, Roman Aqueducts and Water Supply. Duckworth Archaeology (2002).<br />

YEGÜL 2009<br />

F. YEGÜL, Bathing in the Roman World (Cambridge 2009).<br />

WEBER 1989<br />

E. WEBER, Zur Datierung <strong>de</strong>r Tabula Peutingeriana. In: H. Herzig/R. Frei-Stobla (Eds.),<br />

Labor omnibus unus. Festschrift für Gerold Walser (Stuttgart 1989), 113–117.<br />

WEBER 1999<br />

E. WEBER, The Tabula Peutingeriana and the Madaba Map. In: The Madaba Map Centenary<br />

1897–1997 (Jerusalem 1999), 41–46.<br />

WOLLMANN 1968<br />

V. WOLLMANN, Monumente sculpturale din Germisara. Sargetia 5, 1968, 109–120.<br />

221