AFGHANISTAN It is Afghanistan's national instrument with a dark ...

AFGHANISTAN It is Afghanistan's national instrument with a dark ...

AFGHANISTAN It is Afghanistan's national instrument with a dark ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

° T O O L S O F T H E T R A D E : T H E A F g H A n R U B A B °<br />

42 Songlines October 2010<br />

fghan<strong>is</strong>tan <strong>is</strong> a great place for lutes of all kinds<br />

– long-necked, short-necked, plucked, and<br />

bowed. But the king of Afghan <strong>instrument</strong>s <strong>is</strong><br />

the rubab. <strong>It</strong> lies at the heart of Afghan music,<br />

deeply embedded in Afghan <strong>national</strong> identity<br />

and spirituality. <strong>It</strong> has a deep, woody sound.<br />

And although its plucked sound doesn’t<br />

resonate long, it certainly does resonate<br />

amongst the people. “There <strong>is</strong> a spiritual<br />

quality about the <strong>instrument</strong>. <strong>It</strong>’s a pure sound<br />

that comes straight from the heart – and<br />

connects <strong>with</strong> the soul,” says Ghulam Hussain,<br />

the leading rubab player in Kabul today. “For<br />

me th<strong>is</strong> music has a direct relationship <strong>with</strong><br />

God. When I’m playing I close my eyes and I<br />

feel as if I’m in another place.”<br />

The very name rubab <strong>is</strong> said to be a<br />

combination of two Arabic words: ruh,<br />

meaning ‘soul’ and bab ‘doorway,’ so the rubab<br />

<strong>is</strong> ‘the doorway to the soul.’ <strong>It</strong> <strong>is</strong> a<br />

Tools oF<br />

The TRAde<br />

The<br />

AFGhAN<br />

RUBAB<br />

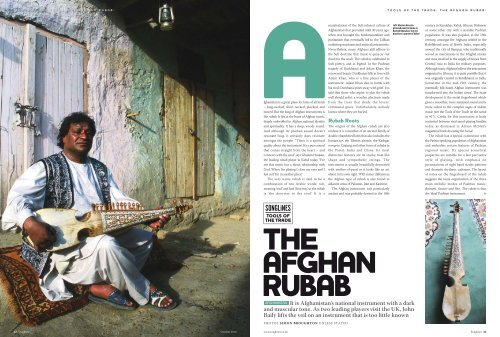

<strong>AFGHANISTAN</strong> <strong>It</strong> <strong>is</strong> Afghan<strong>is</strong>tan’s <strong>national</strong> <strong>instrument</strong> <strong>with</strong> a <strong>dark</strong><br />

and muscular tone. As two leading players v<strong>is</strong>it the UK, John<br />

Baily lifts the veil on an <strong>instrument</strong> that <strong>is</strong> too little known<br />

PHOTOS SI MON BROUGHTON U N L ESS STAT ED<br />

manifestation of the Sufi-infused culture of<br />

Afghan<strong>is</strong>tan that prevailed until 30 years ago,<br />

when war brought the fundamental<strong>is</strong>m and<br />

puritan<strong>is</strong>m that eventually led to the Taliban<br />

outlawing musicians and musical <strong>instrument</strong>s.<br />

Nevertheless, many Afghans still adhere to<br />

the Sufi doctrine that music <strong>is</strong> qaza-ye ruh<br />

(food for the soul). The rubab <strong>is</strong> celebrated in<br />

Sufi poetry, and in legend. In the Pashtun<br />

tragedy of Durkhanai and Adam Khan, the<br />

renowned beauty Durkhanai falls in love <strong>with</strong><br />

Adam Khan, who <strong>is</strong> a fine player of the<br />

<strong>instrument</strong>. Adam Khan dies in battle <strong>with</strong><br />

h<strong>is</strong> rival; Durkhanai pines away <strong>with</strong> grief. <strong>It</strong> <strong>is</strong><br />

said that those who aspire to play the rubab<br />

well should select a wooden plectrum made<br />

from the trees that shade the lovers’<br />

communal grave. Unfortunately, nobody<br />

knows where they are buried.<br />

Rubab Roots<br />

The origins of the Afghan rubab are also<br />

unclear. <strong>It</strong> <strong>is</strong> a member of an ancient family of<br />

double-chambered lutes that also includes the<br />

Iranian tar, the Tibetan danyen, the Kashgar<br />

rewap in Xinjiang and other form of rubabs in<br />

the Pamir, India and China. <strong>It</strong>s most<br />

d<strong>is</strong>tinctive features are its stocky, boat-like<br />

shape and sympathetic strings. The<br />

<strong>instrument</strong> <strong>is</strong> usually beautifully decorated<br />

<strong>with</strong> mother-of-pearl so it looks like an art<br />

object in its own right. With minor differences<br />

the Afghan type of rubab <strong>is</strong> also found in<br />

adjacent areas of Pak<strong>is</strong>tan, Iran and Kashmir.<br />

The Afghan <strong>instrument</strong> <strong>is</strong>n’t particularly<br />

ancient and was probably dev<strong>is</strong>ed in the 18th<br />

° T O O L S O F T H E T R A D E : T H E A F g H A n R U B A B °<br />

Left: Ghulam Hussain<br />

pictured near h<strong>is</strong> home in<br />

Kucheh Kharabat, the old<br />

musicians’ quarter of Kabul<br />

century in Kandahar, Kabul, Ghazni, Peshawar<br />

or some other city <strong>with</strong> a sizeable Pashtun<br />

population. <strong>It</strong> was also popular, in the 19th<br />

century, amongst the Afghans settled in the<br />

Rohilkhand area of North India, especially<br />

around the city of Rampur, who traditionally<br />

served as mercenaries in the Mughal armies<br />

and were involved in the supply of horses from<br />

Central Asia to India for military purposes.<br />

Although many Afghans believe the <strong>instrument</strong><br />

originated in Ghazni, it <strong>is</strong> quite possible that it<br />

was originally created in Rohilkhand, in India.<br />

Sometime in the mid-19th century, the<br />

essentially folk-based Afghan <strong>instrument</strong> was<br />

transformed into the Indian sarod. The main<br />

development <strong>is</strong> the metal fingerboard which<br />

gives a smoother, more sustained sound and <strong>is</strong><br />

more suited to the complex ragas of Indian<br />

music (see the Tools of the Trade on the sarod<br />

in #17). Credit for th<strong>is</strong> innovation <strong>is</strong> hotly<br />

contested between rival sarod-playing families<br />

today, as d<strong>is</strong>cussed in Adrian McNeil’s<br />

mag<strong>is</strong>terial book Inventing the Sarod.<br />

The rubab has a special connection <strong>with</strong><br />

the Pashto speaking population of Afghan<strong>is</strong>tan<br />

and embodies certain features of Pashtun<br />

regional music. <strong>It</strong>s special acoustical<br />

properties are suitable for a fast percussive<br />

style of playing, <strong>with</strong> emphas<strong>is</strong> on<br />

permutations of right hand stroke patterns<br />

and dramatic rhythmic cadences. The layout<br />

of notes on the fingerboard of the rubab<br />

suggests the tonal organ<strong>is</strong>ation of the three<br />

main melodic modes of Pashtun music:<br />

Bairami, Kesturi and Pari. The rubab <strong>is</strong> thus<br />

the ‘ideal’ Pashtun <strong>instrument</strong>. »<br />

www.songlines.co.uk Songlines 43

IllustratIoN: BaIly/MIoNet<br />

° T O O L S O F T H E T R A D E : T H E A F g H A n R U B A B °<br />

The Rubab<br />

Nut<br />

skin belly<br />

Four frets<br />

Pegs for<br />

sympathetic strings<br />

two or three<br />

drone strings<br />

three main<br />

strings<br />

Bridge<br />

strings<br />

holders<br />

Top: Rubab players for hire in<br />

Peshawar, Pak<strong>is</strong>tan<br />

Above: Jawed Qaderi from<br />

the renowned Qaderi family<br />

of rubab makers in Kabul<br />

Left, top to bottom: the neck<br />

and frets; mother-of-pearl<br />

decoration – note the<br />

songbirds; the skin-covered<br />

belly where the strings are<br />

plucked; the decorated body<br />

of Ghulam Hussain’s favourite<br />

<strong>instrument</strong> made by Azim<br />

Qaderi<br />

Rubab Repertoire<br />

Alongside a rich repertoire of folk music, the<br />

rubab <strong>is</strong> also widely used for playing the art<br />

music of Kabul, where it <strong>is</strong> the principal<br />

<strong>instrument</strong> accompanying ghazal singing, as<br />

we can hear in the work of great singers like<br />

Rahim Bakhsh, Hamahang and Amir<br />

Mohammad. As a poetic form, the Kabuli<br />

ghazal (usually in Persian, but sometimes in<br />

Pashto) cons<strong>is</strong>ts of a variable number of<br />

couplets, <strong>with</strong> the same rhyme scheme running<br />

through the whole poem. In performance,<br />

double-tempo accelerating <strong>instrument</strong>al<br />

sections on the rubab are interpolated between<br />

the texts sung at a slow tempo so a ghazal has<br />

the character of a dialogue between the singer<br />

and the rubab player. The texts of ghazals are<br />

very often of a Sufi spiritual nature, by poets<br />

such as Hafez, Bedil and others.<br />

In addition to th<strong>is</strong> role, the Afghan rubab <strong>is</strong><br />

also used for playing two types of <strong>instrument</strong>al<br />

music. One <strong>is</strong> the naghma-ye chahartuk (four<br />

part <strong>instrument</strong>al piece), often used as a group<br />

<strong>instrument</strong>al at the start of a concert, intended<br />

to warm up the <strong>instrument</strong>s, the musicians,<br />

and the audience. Th<strong>is</strong> allows the rubab player<br />

to exploit the rhythmic possibilities of the high<br />

drone string in what might be described as<br />

‘Afghan minimal<strong>is</strong>m.’ The other genre <strong>is</strong> the<br />

naghma-ye klasik (the classical <strong>instrument</strong>al<br />

piece), the Afghan equivalent of Indian alap<br />

and gat, which allows ample scope for melodic<br />

improv<strong>is</strong>ation. The art of playing classical<br />

music on the rubab was pioneered by Ghulam<br />

Jailani and Mohammad Omar and <strong>is</strong> these<br />

days pursued by Homayun Sakhi and Khaled<br />

Arman of the Ensemble Kaboul. Arman has<br />

added more frets to make it easier to play high<br />

up, making it more like h<strong>is</strong> first <strong>instrument</strong>, the<br />

Span<strong>is</strong>h guitar.<br />

Mulberry – With<br />

strings Attached<br />

The rubab has three main playing strings<br />

(tuned in 4ths), four frets (giving 12 semitones<br />

to the octave), two or three long drone strings,<br />

and up to 15 sympathetic strings. <strong>It</strong> <strong>is</strong> the<br />

sympathetic strings that give the rubab its<br />

special sound. They are tuned to the notes of<br />

the raga being played, and reinforce the sound<br />

of each note as it <strong>is</strong> played. They produce a<br />

wash of sound, <strong>with</strong> complex interactions<br />

<strong>with</strong> the harmonics of each string. <strong>It</strong>’s like<br />

having an echo chamber built into the<br />

<strong>instrument</strong>. Some rubabs have empty<br />

eggshells glued inside like tiny cups that<br />

amplify the sound. The shortest sympathetic<br />

string <strong>is</strong> ra<strong>is</strong>ed by a protuberance on the<br />

bridge so it can be easily struck in <strong>is</strong>olation<br />

and used as a high drone in the complex<br />

rhythmic patterns that are the hallmark of the<br />

virtuoso player.<br />

The favourite wood for the body of the<br />

rubab <strong>is</strong> mulberry – and in particular the<br />

variety called shah tut (king mulberry). The<br />

lower chamber has a skin belly, while the upper<br />

has a wooden lid that serves as the fingerboard.<br />

Th<strong>is</strong> <strong>is</strong> usually highly decorated <strong>with</strong> intricate<br />

mother-of-pearl inlays, laid out in the form of a<br />

tree of life, <strong>with</strong> leaves, flowers, and songbirds<br />

such as nightingales or canaries. Afghans have<br />

a great love of birdsong, especially when<br />

combined <strong>with</strong> the sound of music and<br />

understand that such birds are attracted by the<br />

sound of music and are stimulated to sing in<br />

response to it. The frets are of nylon line tied<br />

around the neck. Their positions are not<br />

changed according to the raga being played.<br />

Some rubab players in Herat, notably Rahim<br />

Khushnawaz, have tied two extra frets to their<br />

rubabs to allow the <strong>instrument</strong> to play the<br />

neutral seconds of Iranian music.<br />

44 Songlines October 2010<br />

PasCal laFay<br />

sIMoN BrouGHtoN<br />

KHaleD arMaN ColleCtIoN<br />

The rubab <strong>is</strong> played <strong>with</strong> a wooden, bone, or<br />

horn plectrum (shahbaz) and requires a special<br />

posture for the right hand, <strong>with</strong> the wr<strong>is</strong>t<br />

sharply flexed. With the weight of the hand<br />

behind it, the downstroke has a more powerful<br />

sound than the upstroke, especially when the<br />

hand also impacts on the skin belly, adding a<br />

certain percussive element. The different<br />

permutations of down and upstrokes produce<br />

subtly different rhythmic patterns. As for the<br />

left hand, most rubab players tend to use just<br />

the first and third fingers to stop the strings. <strong>It</strong><br />

<strong>is</strong> easy to play <strong>with</strong>in the limited fretted range<br />

(an octave plus a wholetone), but advanced<br />

players ascend above th<strong>is</strong> which requires great<br />

skill and lots of practice to keep in tune.<br />

Rubab Maestros<br />

Ghulam Hussain <strong>is</strong> a master of both ghazal<br />

accompaniment and solo playing. H<strong>is</strong> father,<br />

Habibullah, played for many years <strong>with</strong> ghazal<br />

singer Rahim Bakhsh, and I had the<br />

Top to bottom: Ensemble<br />

Kaboul featuring singer<br />

Mahwash and rubab player<br />

Khaled Arman; Ghulam<br />

Hussain performing <strong>with</strong> h<strong>is</strong><br />

ensemble in Ryad Moqri at<br />

th<strong>is</strong> year’s Fes Festival; the<br />

first Radio Orchestra <strong>with</strong><br />

rubab player Mohammad<br />

Omar at the back, 1943<br />

Far right: Homayun Sakhi,<br />

who plays the Barbican in<br />

September<br />

d<strong>is</strong>cography<br />

° T O O L S O F T H E T R A D E : T H E A F g H A n R U B A B °<br />

Various Art<strong>is</strong>ts, Rough<br />

Guide to the Music of<br />

Afghan<strong>is</strong>tan (World<br />

Music Network, 2010)<br />

alongside rubab<br />

recordings from Ghulam Hussain (h<strong>is</strong> only<br />

commercially available recording), rahim<br />

Khushnawaz and Homayun sakhi, th<strong>is</strong> includes<br />

popular and folk music from afghan musicians<br />

inside and outside the country. reviewed on p83.<br />

Songlines Digital subscribers can<br />

download a track from th<strong>is</strong> album.<br />

See p58 for details<br />

Mohammad Omar,<br />

Virtuoso from<br />

Afghan<strong>is</strong>tan<br />

(Smithsonian<br />

Folkways, 2002)<br />

the celebrated 1975 concert in seattle, <strong>with</strong> Zakir<br />

Hussain on tabla. Contains three of Mohammad<br />

omar’s most important classical compositions.<br />

Rahim Khushnawaz,<br />

The Rubab of Heart<br />

(VDE-Gallo, 1993)<br />

Herat’s outstanding rubab<br />

maestro, in recordings<br />

made by John Baily in 1974. these include the<br />

classical <strong>instrument</strong>al music of Kabul and local<br />

Herat folk melodies. rather charmingly, some<br />

tracks have canaries singing in the background.<br />

Homayun Sakhi, The<br />

Art of the Afghan<br />

Rubab (Smithsonian<br />

Folkways, 2005)<br />

an outstanding younger<br />

player of the rubab nowadays based in Fremont,<br />

near san Franc<strong>is</strong>co. He has extended the use of the<br />

high drone to new heights of virtuosity. a top of<br />

the World review in #37.<br />

Khaled Arman, Rubab<br />

Raga (Arion, 2003)<br />

Based in Geneva, Khaled<br />

arman (also leader of<br />

ensemble Kaboul) has<br />

made various innovations to the rubab, such as<br />

adding frets to aid the playing of more classical<br />

repertoire. reviewed in #20.<br />

Daud Khan, Tribute to<br />

Afghan<strong>is</strong>tan<br />

(Felmay, 2004)<br />

Daud Khan plays both<br />

rubab and, as a student<br />

of amjad ali Khan, the sarod. th<strong>is</strong> CD contains a<br />

selection of classical and folk pieces.<br />

reviewed in #24.<br />

opportunity to hear and record them perform<br />

together several times in the 70s at Ramadan<br />

concerts. Ghulam Hussain grew up in a<br />

hereditary musical family in the Kucheh<br />

Kharabat, Kabul’s musicians’ quarter. He<br />

learned initially from h<strong>is</strong> father and uncle, but<br />

in due course became the student of<br />

Mohammad Omar (1905-1980), the doyen of<br />

rubab players in the 20th century and the<br />

originator of the styl<strong>is</strong>tic school named after<br />

him. “Ustad Mohammad Omar was the<br />

person who inspired me most,” says Ghulam<br />

Hussain. He was a prolific composer of<br />

classical compositions, and light <strong>instrument</strong>al<br />

pieces for the small radio orchestra that he<br />

directed. He <strong>is</strong> credited <strong>with</strong> inventing the<br />

high drone technique that <strong>is</strong> the hallmark of<br />

h<strong>is</strong> style. Most rubab players today<br />

acknowledge him as the greatest master of the<br />

<strong>instrument</strong> in living memory.<br />

In 1973 I myself started playing the rubab<br />

under Mohammad Omar’s tutelage, going<br />

regularly to h<strong>is</strong> house for lessons. While I gave<br />

him cash for my lessons, Ghulam Hussain, as<br />

Mohammad Omar’s official student, paid for<br />

h<strong>is</strong> tuition through service, and he used to<br />

serve up the tea during my lessons. In 2003 he<br />

was appointed as one of four teachers in the<br />

newly created music school of the Aga Khan<br />

Music Initiative for Central Asia, establ<strong>is</strong>hed<br />

to revital<strong>is</strong>e the vocal and <strong>instrument</strong>al skills<br />

needed to perform Kabuli art music. Seven<br />

years on he <strong>is</strong> still there, teaching, making<br />

periodic concert tours to the West, and doing<br />

h<strong>is</strong> best to generate interest in th<strong>is</strong> wonderful<br />

<strong>instrument</strong>. As he says, “I am happy to play<br />

rubab and I want to develop the <strong>instrument</strong><br />

more and make it popular throughout the<br />

world.” May h<strong>is</strong> ambitions be blessed <strong>with</strong><br />

success. l<br />

dATes Homayun Sakhi plays <strong>with</strong> Alim<br />

Qasimov at the Barbican on September 19,<br />

www.barbican.org.uk<br />

Herati rubab player Wahid Delahang <strong>is</strong> on<br />

tour from September 18-26, www.amc.org.uk<br />

PodCAsT Hear John Baily’s rubab<br />

demonstration and a recording of Rahim<br />

Khushnawaz on th<strong>is</strong> <strong>is</strong>sue’s podcast<br />

www.songlines.co.uk Songlines 45<br />

aGa KHaN trust For Culture