OF

OF

OF

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

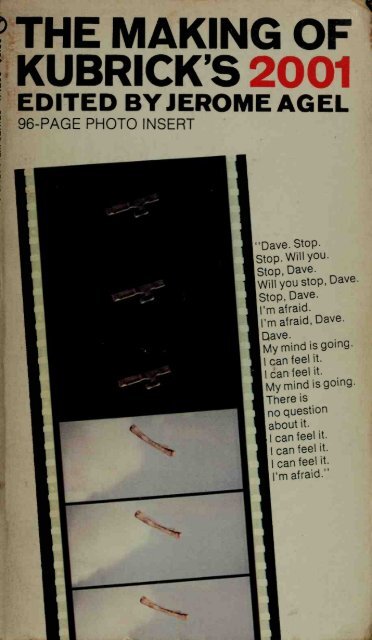

THE MAKING <strong>OF</strong><br />

KUBRICKS 2001<br />

EDITED BY JEROME AGEL<br />

96-PAGE PHOTO INSERT<br />

."Dave. Stop.<br />

IStop. Will you.<br />

Istop.Dave.<br />

lWill you stop, Dave.<br />

IStop.Dave.<br />

II 'm afraid.<br />

I'm afraid, Dave.<br />

I Dave.<br />

I My mind is going.<br />

I I can feel it.<br />

I can feel it.<br />

|My mind is going.<br />

I There is<br />

[no question<br />

\ about it.<br />

I can feel it.<br />

1 1 can feel it.<br />

1 1 can feel it.<br />

I'm afraid."

'See you on the way back.'<br />

In the beginning were the words: lots of them.<br />

On Monday, February 22, 1965,<br />

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer announced that it<br />

would finance production of Stanley Kubrick's<br />

next motion picture, journey Beyond the Stars.<br />

sv> n<br />

**S>"<br />

lcV lAG<br />

*£*»»jr£i°z tbe<br />

Aire<br />

be<br />

to<br />

P,<br />

6^0* » C c^fbWtC \G »*«\<br />

sevens*<br />

C

Dave. Stop.<br />

Stop. Will you.<br />

Stop, Dave.<br />

Will you stop, Dave.<br />

Stop, Dave.<br />

I'm afraid.<br />

I'm afraid, Dave.<br />

Dave.<br />

My mind is going.<br />

I can feel it.<br />

I can feel it.<br />

o<br />

My mind is going.<br />

There is no question<br />

about it.

I can feel it.<br />

I can feel it<br />

I can feel it.<br />

I'm afraid."<br />

The Making<br />

of Kubrick's 2007<br />

Edited, with lots<br />

of legwork, by<br />

JEROME AGEL<br />

SUN IN GEMINI<br />

MOON IN ARIES<br />

CANCER RISING<br />

New American Library

Cover photograph and all M-G-M photographs © 1968<br />

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Inc.<br />

Fourth Printing<br />

Copyright © 1970 by The Agel Publishing Company, Inc.<br />

All rights reserved<br />

©<br />

SIGNET TRADEMARK REG. U.S. PAT. <strong>OF</strong>F. AND FOREIGN COUNTRIES<br />

REGISTERED TRADEMARK—MARCA REGISTRADA<br />

HECHO EN CHICAGO, U.S.A.<br />

Signet, Signet Classics, Mentor and Plume Books<br />

are published by<br />

The New American Library, Inc.,<br />

1301 Avenue of the Americas, New York, New York 10019<br />

First Printing, April, 1970<br />

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES <strong>OF</strong> AMERICA<br />

4

JEROME AGEL, the editor of The Making of<br />

Kubrick's 2001, conceived and coordinated<br />

Marshall McLuhan's The Medium Is the Massage,<br />

coordinated McLuhan's War and Peace in the<br />

Global Village, and coauthored and coordinated<br />

Buckminster Fuller's / Seem To Be a Verb. He<br />

conceived and is writing and coordinating a new<br />

history series, Turning Point, and is co-authoring<br />

with Arthur C. Clarke and producing a project<br />

tentatively entitled Arthur C. Clarke Meets<br />

Hieronymus Bosch.

"It won't be a Buck Rogers kind of space epic/'<br />

— Robert O'Brien, president, M-G-M, who constantly<br />

supported production of 2007 : A Space Odyssey,<br />

even when it went $4,500,000 beyond the original<br />

budget.<br />

"A movie studio is the best toy a boy ever had."<br />

— Orson Welles<br />

"The screen is a magic medium. It has such power that<br />

it can retain interest as it conveys emotions and moods<br />

that no other art form can hope to tackle." — Stanley<br />

Kubrick<br />

Stanley Kubrick, left, and<br />

Arthur C. Clarke.<br />

"'MydearRikki,'<br />

Ka re lien retorted,<br />

'it's only by not taking<br />

the human race<br />

seriously that I retain<br />

what fragments of my<br />

once considerable<br />

mental powers I<br />

still<br />

possess/ " — from<br />

Childhood's End, by<br />

Arthur C. Clarke<br />

"2007; A Space<br />

Odyssey is about<br />

man's past and future<br />

life in space. It's<br />

about concern with<br />

man's hierarchy in the<br />

universe, which is<br />

probably pretty low.<br />

It's about the reactions of humanity to the discovery of<br />

higher intelligence in the universe. We set out with the<br />

deliberate intention of creating a myth. The Odyssean<br />

parallel was in our minds from the beginning, long before<br />

the film's title was chosen." -Arthur C. Clarke

"I don't like to talk about 200 7 much because it's<br />

essentially a nonverbal experience. Less than half the film<br />

has dialogue. It attempts to communicate more to the<br />

subconscious and to thefeelings than it does to the<br />

intellect. I think clearly that there's a basic problem with<br />

people who are not paying attention with their eyes.<br />

They're listening. And they don't get much from listening<br />

to this film. Those who won't believe their eyes won't<br />

be able to appreciate this film." —Stanley Kubrick<br />

Stanley Kubrick, left, and<br />

Arthur C. Clarke.

* « O

"Are you coming to my party<br />

tomorrow?"<br />

The cost of construction of the 200-inch Hale telescope at<br />

Palomar and the cost of production of the out-of-sight motion<br />

picture 2001: A Space Odyssey, produced and directed by<br />

Stanley Kubrick, were about the same: $10,500,000.00.<br />

The divorce rate at the Cape Kennedy missile-launch center<br />

is said to be the highest in the nation, but who's divorcing<br />

whom?<br />

Bob Dylan: "Just because you like my stuff doesn't mean I owe<br />

you anything."<br />

I have seen Stanley Kubrick's musical comedy (2001) every<br />

day since it opened in Manhattan nearly two years ago, and<br />

I can hardly wait to see it today. The first time I saw 2001 I<br />

was sure it was a put-on. It is, after all, riddled with humor;<br />

Kubrick is, after all, well known for tongue-in-cheek; the universe<br />

is, after all (it must be; look at the front page of The New<br />

York Times any day), a cosmic joke, and wasn't this motion<br />

picture about the universe?<br />

I am now convinced that the film is the best.<br />

Every time I see it, I re-love that sexy love scene in the car . .<br />

Leonard Rossiter maneuvering his whiskey glass . . . the stars<br />

exploding in an abandoned corset factory in Manhattan.<br />

Andre Breton: "Everything leads us to believe that there exists<br />

a certain point of the intelligence at which life and death, the<br />

real and the imaginary, the past and the future . . . cease to be<br />

perceived as opposites."<br />

Arthur C. Clarke: "M-G-M doesn't know it yet, but they've<br />

footed the bill for the first $10,500,000.00 religious film."<br />

(Clarke says he's been on Atlantis. Recently.)<br />

Kubrick: "It's hard to convey a film's unique qualities in its<br />

advertising. The sense of what a movie is like quickly gets<br />

around."<br />

.

"1 See 2001 Every Day" 1<br />

The word got around. The ads didn't convey the mindtaking,<br />

the breathtaking experience that is 2001 -the many reasons<br />

everyone should see it, and would like to see it. The title 2001:<br />

A Space Odyssey may even have been misleading. The medium<br />

is the message.<br />

2001 is an astonishing visual tour de force. (There are more<br />

murders in it than there were by Bonnie and Clyde on-screen.)<br />

"Hush" was the key word during production. As in, "Let's<br />

keep those secrets right here in the office, eh fellows." "Hush"<br />

was the key word during the movie itself. As in, "I don't suppose<br />

you have any idea what the damned thing is?" "Hush"<br />

continues to be the key word about the box office. "You know,<br />

Jerry, sir, we never give out those figures."<br />

The rule of Variety* % thumb is that a production of this magnitude<br />

must recoup two and one-half times its production nut to<br />

break even; in this case, at least $25,000,000.00. (Clarke says<br />

that he and Kubrick are laughing all the way to the bank.)<br />

For the box-office hit Dr. Strangelove, Kubrick had been voted<br />

Best Director by the New York Film Critics Circle. "Don't<br />

laugh," he said at Trader Vic's, "but I'm fascinated with the<br />

possibility of extraterrestrials."<br />

Clarke was contacted in Ceylon, and responded: interested<br />

IN WORKING WITH ENFANT TERRIBLE STOP CONTACT MY AGENT<br />

STOP WHAT MAKES KUBRICK THINK I'M A RECLUSE?<br />

Once upon a time (which would have made a provocative title<br />

for the film), Stanley Kubrick and Arthur C. Clarke -two of<br />

the best we have — set out to show the reactions of humanity<br />

to the discovery of the existence of higher intelligences in the<br />

universe. It turned out to be classified information.<br />

Kubrick: "If it can be written, or thought, it can be filmed."<br />

Oh that it were.<br />

Wyndham Lewis: "The artist is always engaged in writing a<br />

detailed history of the future because he's the only person<br />

aware of the nature of the present." H. Marshall McLuhan:<br />

"Knowledge of this simple fact is now needed for human survival."<br />

McLuhan's Fuller Nietzsche.<br />

Kubrick: "There's a new beauty afoot." (Terrific ten-year-old<br />

girl on her way home from the sixth grade: "You know, current<br />

events take up too much time.")<br />

1

1<br />

2<br />

The Making of Kubrick's 200<br />

Leonard Cohen: "God is alive, magic is afoot. Magic is alive,<br />

God is afoot."<br />

Celebrating the start of the third millennium, Kubrick made a<br />

motion picture that's a joy to look at, one that could be projected<br />

endlessly on a museum gallery wall. The Guggenheim<br />

in NYC! He wanted to make a motion picture about an event<br />

that might occur within the lifetime of most of today's filmgoers—<br />

an encounter between us and them. (It is probable that<br />

the encounter has already taken place.)<br />

The film's "star," HAL, a computer, was right when he said<br />

that it was human error that was endangering the Jupiter<br />

mission. (Look at The Times front page again.) HAL had been<br />

overprogrammed for mission enthusiasm and success. He became<br />

oversensitive to the human element.<br />

(To her indefatigable father after three grueling days of sightseeing<br />

in Washington, terrific ten-year-old, sensory-overloaded<br />

girl in the Smithsonian Institution: "I'll walk through<br />

the exhibits with you, but I won't look.")<br />

We are all machines. (What happened to your lunch?)<br />

We have met the enemy and we are theirs.<br />

Getting there was all the fun.<br />

In 2001:<br />

The brilliant, absolutely brilliant, acting - a Kubrick touchstone<br />

since The Killing (Timothy Carey, Sterling Hayden, Elijah<br />

Cook, Marie Windsor). Here, William Sylvester, Dan Richter,<br />

Keir Dullea, Gary Lockwood, Douglas Rain, Leonard Rqssiter,<br />

Vivian Kubrick.<br />

The brilliant, absolutely brilliant, use of music: "The Blue<br />

Danube," a stroke of genius. Khatchaturian's "Gayne Ballet<br />

Suite." Ligeti (who successfully sued for having had his music<br />

distorted). ("The Blue Danube" was also performed in Dullea's<br />

The Hoodlum Priest.)<br />

The brilliant, absolutely brilliant, dialogue: "A woman's<br />

cashmere sweater has been found . . . Sorry I'm late ... I don't<br />

know. What do you think? .<br />

think about it.<br />

. . Deliberately buried, eh." Please<br />

The brilliant, absolutely brilliant, sound effects: Breathing.<br />

Laughter and chatter of the extraterrestrials examining the<br />

1

"I See 2001 Every Day" 13<br />

astronaut in a room in his mind. More information than words.<br />

I don't like movies — and I only see the ones I've already seen.<br />

2001 may be the first motion picture that may be called a motion<br />

picture, that could have been produced only in the medium.<br />

"Dear 15-Year-Old Miss Stackhouse, of North Plainfield, N.J.:<br />

Yours is perhaps the most intelligent speculation I've read on<br />

2001 r Signed/Stanley Kubrick. (See page 201.)<br />

At one time, the director thought that his film would run about<br />

an hour. And then, the special effects started to take hold.<br />

Magic was afoot. (See ninety-six-page picture section.)<br />

And so, The Dawn of Man was made — and they called it, okay,<br />

2001: A Space Odyssey. It started where Dr. Strangelove<br />

had left off. At the territorial imperative. "Mein Fiihrer, I can<br />

walk, I can walk."<br />

It is said that 2001: A Space Odyssey — "Some sort of great<br />

film!" agreed The New Yorker— is about the first contact with<br />

a mysterious intelligence. Have you looked at your air-conditioner<br />

lately?<br />

(This book was produced with the help of the film's principals<br />

and many other friends: Edward Rosenfeld, Eric Norden,<br />

Carole Livingston, Joan Feinberg t<br />

and Stephan Chodorov.)

Elena, you're looking wonderful.'<br />

Would you believe .<br />

A Moon bus two feet long?<br />

Source of illumination<br />

for "the sun" had to be<br />

11 stops overexposed?<br />

A stellar cataclysm filmed<br />

in an abandoned corset<br />

factory in Manhattan?<br />

Three feet long?<br />

Thirteen inches in diameter?

"Hi, everybody. Nice to be<br />

back with you."<br />

Little did Arthur C. Clarke know in 1950 that his<br />

latest short story, "The Sentinel," would be the basis,<br />

fifteen years later, for a $10,500,000.00 motion-<br />

picture production.<br />

THE SENTINEL*<br />

Arthur C. Clarke<br />

the next time you see the full moon high in the south, look<br />

carefully at its right-hand edge and let your eye travel upward<br />

along the curve of the disk. Round about two o'clock you will<br />

notice a small, dark oval: anyone with normal eyesight can find<br />

it quite easily. It is the great walled plain, one of the finest on<br />

the Moon, known as the Mare Crisium — the Sea of Crises.<br />

Three hundred miles in diameter, and almost completely surrounded<br />

by a ring of magnificent mountains, it had never been<br />

explored until we entered it in the late summer of 1 996.<br />

Our expedition was a large one. We had two heavy freighters<br />

which had flown our supplies and equipment from the main<br />

lunar base in the Mare Serenitatis, five hundred miles away.<br />

There were also three small rockets which were intended for<br />

short-range transport over regions which our surface vehicles<br />

couldn't cross. Luckily, most of the Mare Crisium is very flat.<br />

There are none of the great crevasses so common and so dangerous<br />

elsewhere, and very few craters or mountains of any<br />

size. As far as we could tell, our powerful caterpillar tractors<br />

would have no difficulty in taking us wherever we wished to go.<br />

I was geologist — or selenologist, if you want to be pedantic<br />

— in charge of the group exploring the southern region of the<br />

Mare. We had crossed a hundred miles of it in a week, skirting<br />

the foothills of the mountains along the shore of what was<br />

once the ancient sea, some thousand million years before.<br />

When life was beginning on Earth, it was already dying here.<br />

* Copyright © 1950 by Arthur C. Clarke. Reprinted by permission<br />

of the author and his agents, Scott Meredith Agency, Inc., 580<br />

Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10036.

16 The Making of Kubrick's 2001<br />

The waters were retreating down the flanks of those stupendous<br />

cliffs, retreating into the empty heart of the Moon. Over the<br />

land which we were crossing, the tideless ocean had once been<br />

half a mile deep, and now the only trace of moisture was the<br />

hoarfrost one could sometimes find in caves which the searing<br />

sunlight never penetrated.<br />

We had begun our journey early in the slow lunar dawn, and<br />

still had almost a week of Earth-time before nightfall. Half a<br />

dozen times a day we would leave our vehicle and go outside<br />

in the space suits to hunt for interesting minerals, or to place<br />

markers for the guidance of future travelers. It was an unevent-<br />

ful routine. There is nothing hazardous or even particularly<br />

exciting about lunar exploration. We could live comfortably<br />

for a month in our pressurized tractors, and if we ran into<br />

trouble, we could always radio for help and sit tight until one<br />

of the spaceships came to our rescue.<br />

I said just now that there was nothing exciting about lunar<br />

exploration, but of course that isn't true. One could never<br />

grow tired of those incredible mountains, so much more rugged<br />

than the gentle hills of Earth. We never knew, as we rounded<br />

the capes and promontories of that vanished' sea, what new<br />

splendors would be revealed to us. The whole southern curve<br />

of the Mare Crisium is a vast delta where a score of rivers once<br />

found their way into the ocean, fed perhaps by the torrential<br />

rains that must have lashed the mountains in the brief volcanic<br />

age when the Moon was young. Each of these ancient valleys<br />

was an invitation, challenging us to climb into the unknown<br />

uplands beyond. But we had a hundred miles still to cover, and<br />

could only look longingly at the heights which others must<br />

scale.<br />

We kept Earth-time aboard the tractor, and precisely at<br />

22:00 hours the final radio message would be sent out to Base<br />

and we would close down for the day. Outside, the rocks would<br />

still be burning beneath the almost vertical sun, but to us it<br />

would be night until we awoke again eight hours later. Then<br />

one of us would prepare breakfast, there would be a great<br />

buzzing of electric razors, and someone would switch on the<br />

shortwave radio from Earth. Indeed, when the smell of frying<br />

sausages began to fill the cabin, it was sometimes hard to<br />

believe that we were not back on our own world — everything<br />

was so normal and homely, apart from the feeling of decreased<br />

weight and the unnatural slowness with which objects fell.<br />

It was my turn to prepare breakfast in the corner of the main<br />

cabin that served as a galley. I can remember that moment<br />

quite vividly ^fter all these years, for the radio had just played<br />

one of my favorite melodies, the old Welsh air "David of the<br />

White Rock." Our driver was already outside in his space suit,

The Sentinel 17<br />

inspecting our caterpillar treads. My assistant, Louis Garnett,<br />

was up forward in the control position, making some belated<br />

entries in yesterday's log.<br />

As I stood by the frying pan, waiting, like any terrestrial<br />

housewife, for the sausages to brown, I let my gaze wander<br />

idly over the mountain walls which covered the whole of the<br />

southern horizon, marching out of sight to east and west below<br />

the curve of the Moon. They seemed only a mile or two from<br />

the tractor, but I knew that the nearest was twenty miles away.<br />

On the Moon, of course, there is no loss of detail with distance<br />

— none of that almost imperceptible haziness which softens<br />

and sometimes transfigures all far-off things on Earth.<br />

Those mountains were ten thousand feet high, and they<br />

climbed steeply out of the plain as if ages ago some subterranean<br />

eruption had smashed them skyward through the molten<br />

crust. The base of even the nearest was hidden from sight by<br />

the steeply curving surface of the plain, for the Moon is a very<br />

little world, and from where I was standing the horizon was<br />

only two miles away.<br />

I lifted my eyes toward the peaks which no man had ever<br />

climbed, the peaks which, before the coming of terrestrial life,<br />

had watched the retreating oceans sink sullenly into their<br />

graves, taking with them the hope and the morning promise of a<br />

world. The sunlight was beating against those ramparts with a<br />

glare that hurt the eyes, yet only a little way above them the<br />

stars were shining steadily in a sky blacker than a winter midnight<br />

on Earth.<br />

I was turning away when my eye caught a metallic glitter<br />

high on the ridge of a great promontory thrusting out into the<br />

sea thirty miles to the west. It was a dimensionless point of<br />

light, as if a star had been clawed from the sky by one of those<br />

cruel peaks, and I imagined that some smooth rock surface<br />

was catching the sunlight and heliographing it straight into my<br />

eyes. Such things were not uncommon. When the Moon is in<br />

her second quarter, observers on Earth can sometimes see the<br />

great ranges in the Oceanus Procellarum burning with a bluewhite<br />

iridescence as the sunlight flashes from their slopes and<br />

leaps again from world to world. But I was curious to know<br />

what kind of rock could be shining so brightly up there, and I<br />

climbed into the observation turret and swung our four-inch<br />

telescope round to the west.<br />

I could see just enough to tantalize me. Clear and sharp in<br />

the field of vision, the mountain peaks seemed only half a mile<br />

away, but whatever was catching the sunlight was still too<br />

small to be resolved. Yet it seemed to have an elusive symmetry,<br />

and the summit upon which it rested was curiously flat.<br />

I stared for a long time at that glittering enigma, straining my

1<br />

8<br />

The Making of Kubrick's 200<br />

eyes into space, until presently a smell of burning from the<br />

galley told me that our breakfast sausages had made their<br />

quarter-million-mile journey in vain.<br />

All that morning we argued our way across the Mare Crisium<br />

while the western mountains reared higher in the sky. Even<br />

when we were out prospecting in the space suits, the discussion<br />

would continue over the radio. It was absolutely certain, my<br />

companions argued, that there had never been any form of<br />

intelligent life on the Moon. The only living things that had<br />

ever existed there were a few primitive plants and their slightly<br />

less degenerate ancestors. I knew that as well as anyone, but<br />

there are times when a scientist must not be afraid to make a<br />

fool of himself.<br />

"Listen," I said at last, "I'm going up there, if only for my<br />

own peace of mind. That mountain's Jess than twelve thousand<br />

feet high — that's only two thousand under Earth gravity — and<br />

I can make the trip in twenty hours at the outside. I've always<br />

wanted to go up into those hills, anyway, and this gives me an<br />

excellent excuse."<br />

"If you don't break your neck," said Garnett, "you'll be the<br />

laughingstock of the expedition when we get back to Base.<br />

That mountain will probably be called Wilson's Folly from now<br />

on."<br />

"I won't break my neck," I said firmly. "Who was the first<br />

man to climb Pico and Helicon?"<br />

"But weren't you rather younger in those days?" asked<br />

Louis gently.<br />

"That," I said with great dignity, "is as good a reason as any<br />

forgoing."<br />

We went to bed early that night, after driving the tractor to<br />

within half a mile of the promontory. Garnett was coming with<br />

me in the morning; he was a good climber, and had often been<br />

with me on such exploits before. Our driver was only too glad<br />

to be left in charge of the machine.<br />

At first sight, those cliffs seemed completely unscalable, but<br />

to anyone with a good head for heights, climbing is easy on a<br />

world where all weights are only a sixth of their normal value.<br />

The real danger in lunar mountaineering lies in overconfidence;<br />

a six-hundred-foot drop on the Moon can kill you just as<br />

thoroughly as a hundred-foot fall on Earth.<br />

We made our first halt on a wide ledge about four thousand<br />

feet above the plain. Climbing had not been very difficult, but<br />

my limbs were stiff with the unaccustomed effort, and I was<br />

glad of the rest. We could still see the tractor as a tiny metal<br />

insect far down at the foot of the cliff, and we reported our<br />

progress to the driver before starting on the next ascent.<br />

Inside our suits it was comfortably cool, for the refrigeration<br />

1

The Sentinel 19<br />

units were fighting the fierce sun and carrying away the body<br />

heat of our exertions. We seldom spoke to each other, except<br />

to pass climbing instructions and to discuss our best plan of<br />

ascent. I do not know what Garnett was thinking, probably that<br />

this was the craziest goose chase he had ever embarked upon.<br />

I more than half agreed with him, but the joy of climbing, the<br />

knowledge that no man had ever gone this way before, and the<br />

exhilaration of the steadily widening landscape gave me all<br />

the reward I needed.<br />

I don't think I was particularly excited when I saw in front<br />

of us the wall of rock I had first inspected through the telescope<br />

from thirty miles away. It would level off about fifty<br />

feet above our heads, and there on the plateau would be the<br />

thing that had lured me over these barren wastes. It would be,<br />

almost certainly, nothing more than a boulder splintered ages<br />

ago by a falling meteor, and with its cleavage planes still fresh<br />

and bright in this incorruptible, unchanging silence.<br />

There were no handholds on the rock face, and we had to<br />

use a grapnel. My tired arms seemed to gain new strength as<br />

I swung the three-pronged metal anchor round my head and<br />

sent it sailing up toward the stars. The first time it broke loose<br />

and came falling slowly back when we pulled the rope. On the<br />

third attempt, the prongs gripped firmly and our combined<br />

weights could not shift it.<br />

Garnett looked at me anxiously. I could tell that he wanted<br />

to go first, but I smiled back at him through the glass of my<br />

helmet and shook my head. Slowly, taking my time, I began the<br />

final ascent.<br />

Even with my space suit, I weighed only forty pounds here,<br />

so I pulled myself up hand over hand without bothering to use<br />

my feet. At the rim I paused and waved to my companion, then<br />

I scrambled over the edge and stood upright, staring ahead of<br />

me.<br />

You must understand that until this very moment I had been<br />

almost completely convinced that there could be nothing<br />

strange or unusual for me to find here. Almost, but not quite;<br />

it was that haunting doubt that had driven me forward. Well, it<br />

was a doubt no longer, but the haunting had scarcely begun.<br />

I was standing on a plateau perhaps a hundred feet across.<br />

It had once been smooth -too smooth to be natural -but falling<br />

meteors had pitted and scored its surface through immeasurable<br />

eons. It had been leveled to support a glittering, roughly<br />

pyramidal structure, twice as high as a man, that was set in the<br />

rock like a gigantic, many faceted jewel.<br />

Probably no emotion at all filled my mind in those first few<br />

seconds. Then I felt a great lifting of my heart, and a strange,<br />

inexpressible joy. For I loved the Moon, and now I knew that

20 The Making of Kubrick's 200<br />

the creeping moss of Aristarchus and Eratosthenes was not the<br />

only life she had brought forth in her youth. The old, discredited<br />

dream of the first explorers was true. There had, after all, been<br />

a lunar civilization -and I was the first to find it. That I had<br />

come perhaps a hundred million years too late did not distress<br />

me; it was enough to have come at all.<br />

My mind was beginning to function normally, to analyze and<br />

to ask questions. Was this a building, a shrine— or something<br />

for which my language had no name? If a building, then why<br />

was it erected in so uniquely inaccessible a spot? I wondered<br />

if it might be a temple, and I could picture the adepts of some<br />

strange priesthood calling on their gods to preserve them as the<br />

life of the Moon ebbed with the dying oceans, and calling on<br />

their gods in vain.<br />

I took a dozen steps forward to examine the thing more<br />

closely, but some sense of caution kept me from going too near.<br />

I knew a little of archaeology, and tried to guess the cultural<br />

level of the civilization that must have smoothed this mountain<br />

and raised the glittering mirror surfaces that still dazzled my<br />

eyes.<br />

The Egyptians could have done it, I thought, if their workmen<br />

had possessed whatever strange materials these far more<br />

ancient architects had used. Because of the thing's smallness,<br />

it did not occur to me that I might be looking at the handiwork<br />

of a race more advanced than my own. The idea that the Moon<br />

had possessed intelligence at all was still almost too tremendous<br />

to grasp, and my pride would not let me take the final, humiliating<br />

plunge.<br />

And then I noticed something that set the scalp crawling at<br />

the back of my neck — something so trivial and so innocent<br />

that many would never have noticed it at all. I have said that<br />

the plateau was scarred by meteors; it was also coated inches<br />

deep with the cosmic dust that is always filtering down upon<br />

the surface of any world where there are no winds to disturb<br />

it. Yet the dust and the meteor scratches ended quite abruptly<br />

in a wide circle enclosing the little pyramid, as though an invisible<br />

wall was protecting it from the ravages of time and the<br />

slow but ceaseless bombardment from space.<br />

There was someone shouting in my earphones, and I realized<br />

that Garnett had been calling me for some time. I walked unsteadily<br />

to the edge of the cliff and signaled him to join me, not<br />

trusting myself to speak. Then I went back toward that circle<br />

in the dust. I picked up a fragment of splintered rock and tossed<br />

it gently toward the shining enigma. If the pebble had vanished<br />

at that invisible barrier, I should not have been surprised, but I<br />

it seemed to hit a smooth, hemispheric surface and slide gently<br />

to the ground.<br />

1<br />

|

The Sentinel 21<br />

I knew then that I was looking at nothing that could be<br />

matched in the antiquity of my own race. This was not a build-<br />

ing, but a machine, protecting itself with forces that had challenged<br />

Eternity. Those forces, whatever they might be. were<br />

stilf operating, and perhaps I had already come too close. I<br />

thought of all the radiations man had trapped and tamed in the<br />

past century. For all I knew. I might be as irrevocably doomed<br />

as if I had stepped into the deadly, silent aura of an unshielded<br />

atomic pile.<br />

I remember turning then toward Garnett. who had joined<br />

me and was now standing motionless at my side. He seemed<br />

quite oblivious to me. so I did not disturb him but walked to the<br />

edge of the cliff in an effort to marshal my thoughts. There below<br />

me lay the Mare Crisium-Sea of Crises, indeed -strange<br />

and weird to most men. but reassuringly familiar to me. I lifted<br />

my eyes toward the crescent Earth, tying in her cradle of stars,<br />

and I wondered what her clouds had covered when these unknown<br />

builders had finished their work. Was it the steaming<br />

jungle of the Carboniferous, the bleak shoreline over which<br />

the first amphibians must crawl to conquer the land — or. earlier<br />

still, the long loneliness before the coming of life?<br />

Do not ask me why I did not guess the truth sooner — the<br />

truth that seems so obvious now. In the first excitement of my<br />

discovery. I had assumed without question that this crystalline<br />

apparition had been built by some race belonging to the Moon's<br />

remote past, but suddenly, and with overwhelming force, the<br />

belief came to me that it was as alien to the Moon as I myself.<br />

In twenty years we had found no trace of life but a few degenerate<br />

plants. No lunar civilization, whatever its doom, could<br />

have left but a single token of its existence.<br />

I looked at the shining pyramid again, and the more I looked.<br />

the more remote it seemed from anything that had to do with<br />

the Moon. And suddenly I felt myself shaking with a foolish,<br />

hysterical laughter, brought on by excitement and overexertion:<br />

For I had imagined that the little pyramid was speaking to me<br />

and was saying. "'Sorry. I'm a stranger here myself."<br />

It has taken us twenty years to crack that invisible shield<br />

and to reach the machine inside those crystal walls. What we<br />

could not understand, we broke at last with the savage might of<br />

atomic power and now I have seen the fragments of the lovely.<br />

glittering thing I found up there on the mountain.<br />

They are meaningless. The mechanisms — if indeed they are<br />

mechanisms -of the pyramid belong to a technology that lies<br />

far beyond our horizon, perhaps to the technology of paraphysical<br />

forces.<br />

The mystery haunts us all the more now that the other planets

22 The Making of Kubrick's 2001<br />

have been reached and we know that only Earth has ever been<br />

the home of intelligent life in our Universe. Nor could any lost<br />

civilization of our own world have built that machine, for the<br />

thickness of the meteoric dust on the plateau has enabled us to<br />

measure its age. It was set there upon its mountain before life<br />

had emerged from the seas of Earth.<br />

When our world was half its present age, something from the<br />

stars swept through the Solar System, left this token of its<br />

passage, and went again upon its way. Until we destroyed it,<br />

that machine was still fulfilling the purpose of its builders; and<br />

as to that purpose, here is my guess.<br />

Nearly a hundred thousand million stars are turning in the<br />

circle of the Milky Way, and long ago other races on the worlds<br />

of other suns must have scaled and passed the heights that we<br />

have reached. Think of such civilizations, far back in time<br />

against the fading afterglow of Creation, masters of a universe<br />

so young that life as yet had come only to a handful of worlds.<br />

Theirs would have been a loneliness we cannot imagine, the<br />

loneliness of gods looking out across infinity and finding none<br />

to share their thoughts.<br />

They must have searched the star clusters as we have<br />

searched the planets. Everywhere there would be worlds, but<br />

they would be empty or peopled with crawling, mindless things.<br />

Such was our own Earth, the smoke of the great volcanoes<br />

still staining the skies, when that first ship of the peoples of the<br />

dawn came sliding in from the abyss beyond Pluto. It passed<br />

the frozen outer worlds, knowing that life could play no part<br />

in their destinies. It came to rest among the inner planets,<br />

warming themselves around the fire of the Sun and waiting for<br />

their stories to begin.<br />

Those wanderers must have looked on Earth, circling safely<br />

in the narrow zone between fire and ice, and must have guessed<br />

that it was the favorite of the Sun's children. Here, in the distant<br />

future, would be intelligence; but there were countless<br />

stars before them still, and they might never come this way<br />

again.<br />

So they left a sentinel, one of millions they scattered throughout<br />

the Universe, watching over all worlds with the promise of<br />

life. It was a beacon that down the ages patiently signaled the<br />

fact that no one had discovered it.<br />

Perhaps you understand now why that crystal pyramid was<br />

set upon the Moon instead of on the Earth. Its builders were<br />

not concerned with races still struggling up from savagery.<br />

They would be interested in our civilization only if we proved<br />

j<br />

our fitness to survive — by crossing space and so escaping from<br />

the Earth, our cradle. That is the challenge that all intelligent<br />

races must meet, sooner or later. It is a double challenge, for

The Sentinel 23<br />

it depends in turn upon the conquest of atomic energy and the<br />

last choice between life and death.<br />

Once we had passed that crisis, it was only a matter of time<br />

before we found the pyramid and forced it open. Now its signals<br />

have ceased, and those whose duty it is will be turning their<br />

minds upon Earth. Perhaps they wish to help our infant civilization.<br />

But they must be very, very old. and the old are often<br />

insanely jealous of the young.<br />

I can never look now at the Milky Way without wondering<br />

from which of those banked clouds of stars the emissaries are<br />

coming. If you will pardon so commonplace a simile, we have<br />

set off the fire alarm and have nothing to do but to wait.<br />

I do not think we will have to wait for long.

"I must say you guys have<br />

come up with something."<br />

The New Yorker magazine published four articles<br />

on 200 1 :<br />

A review of the film, a review of the book,<br />

a Profile of Stanley Kubrick, and the following "Talk<br />

of the Town" article when Kubrick and Clarke were<br />

well into preproduction discussion and writing.<br />

BEYOND THE STARS*<br />

Jeremy Bernstein<br />

To most people, including us, the words "science-fiction<br />

movie" bring up visions of super-monsters who have flames<br />

shooting out of at least one eye while an Adonislike Earthman<br />

carries Sylvanna, a stimulating blonde, to a nearby spaceship.<br />

It is a prospect that has often kept us at home. However, we<br />

are happy to report, for the benefit of science-fiction buffs<br />

— who have long felt that, at its best, science fiction is a splendid<br />

medium for conveying the poetry and wonder of science — that<br />

there will soon be a movie for them. We have this from none<br />

other than the two authors of the movie, which is to be called<br />

Journey Beyond the Stars — Stanley Kubrick and Arthur C.<br />

Clarke. It is to be based on a forthcoming novel called Journey<br />

Beyond the Stars, by Arthur C. Clarke and Stanley Kubrick.<br />

Mr. Clarke and Mr. Kubrick, who have been collaborating on<br />

the two projects for over a year, explained to us that the order<br />

of the names in the movie and the novel was reversed to stress<br />

Mr. Clarke's role as a science-fiction novelist (he has written<br />

dozens of stories, many of them regarded as modern science-<br />

fiction classics) and Mr. Kubrick's role as a moviemaker (his<br />

most recent film was Dr. Strangelove).<br />

Our briefing session took place in the living room of Mr.<br />

Kubrick's apartment. When we got there, Mr. Kubrick was<br />

talking on a telephone in the next room, Mr. Clarke had not<br />

yet arrived, and three lively Kubrick daughters — the eldest is<br />

Inc.<br />

* Reprinted by permission; © 1965 The New Yorker Magazine,

Beyond the Stars by Jeremy Bernstein 25<br />

eleven — were running in and out with several young friends.<br />

We settled ourself in a large chair, and a few minutes later the<br />

doorbell rang. One of the little girls went to the door and asked,<br />

"Who is it?" A pleasantly English-accented voice answered,<br />

through the door, "It's Clarke," and the girls began jumping<br />

up and down and saying, "It's Clark Kent!" — a reference to<br />

another well-known science-fiction personality. They opened<br />

the door, and in walked Mr. Clarke, a cheerful-looking man in<br />

his forties. He was carrying several manila envelopes, which, it<br />

turned out, contained parts of Journey Beyond the Stars. Mr.<br />

Kubrick then came into the room carrying a thick pile of diagrams<br />

and charts, and looking like the popular conception of a<br />

nuclear physicist who has been interrupted in the middle of<br />

some difficult calculations. Mr. Kubrick and Mr. Clarke sat<br />

down side by side on a sofa, and we asked them about their<br />

joint venture.<br />

Mr. Clarke said that one of the basic problems they've had<br />

to deal with is how to describe what they are trying to do.<br />

"Science-fiction films have always meant monsters and sex,<br />

so we have tried to find another term for our film," said Mr. C.<br />

"About the best we've been able to come up with is a space<br />

Odyssey — comparable in some ways to the Homeric Odyssey''<br />

said Mr. K. "It occurred to us that for the Greeks the vast<br />

stretches of the sea must have had the same sort of mystery<br />

and remoteness that space has for our generation, and that the<br />

far-flung islands Homer's wonderful characters visited were<br />

no less remote to them than the planets our spacemen will soon<br />

be landing on are to us. Journey also shares with the Odyssey<br />

a concern for wandering, exploration, and adventure."<br />

Mr. Clarke agreed, and went on to tell us that the new film<br />

7<br />

is set in the near future, at a time when the Moon will have been<br />

colonized and space travel, at least around the planetary system,<br />

will have become commonplace. "Since we will soon be<br />

visiting the planets, it naturally occurs to one to ask whether, in<br />

the past, anybody has come to Earth to visit us," he said. "In<br />

Journey Beyond the Stars, the answer is definitely yes, and the<br />

Odyssey unfolds as our descendants attempt to make contact<br />

with some extraterrestrial explorers. There will be no women<br />

among those who make the trip, although there will be some on<br />

Earth, some on the Moon, and some working in space."<br />

Relieved, we asked where the film was to be made, and were<br />

told that it would be shot in the United States and several foreign<br />

countries.<br />

"How about the scenes Out There?" we inquired.<br />

Mr. Kubrick explained that they would be done with the aid<br />

of a vast assortment of cinematic tricks, but he added emphatically<br />

that everything possible would be done to make each

26 The Making of Kubrick's 2001<br />

scene completely authentic and to make it conform to what is<br />

known to physicists and astronomers. He and Mr. Clarke feel<br />

that while there will be dangers in space, there will also be<br />

wonder, adventure, and beauty, and that space is a source of<br />

endless knowledge, which may transform our civilization in the<br />

same way that the voyages of the Renaissance transformed the<br />

Dark Ages. They want all these elements to come through in<br />

the film. Mr. Kubrick told us that he has been a reader of<br />

science-fiction and popular-science books, including Mr.<br />

Clarke's books on space travel, for many years, and that he has<br />

become increasingly disturbed by the barrier between scientific<br />

knowledge and the general public. He has asked friends basic<br />

questions like how many stars there are in our galaxy, he went<br />

on, and has discovered that most people have no idea at all.<br />

"The answer is a hundred billion, and sometimes they stretch<br />

their imaginations and say maybe four or five million," he said.<br />

Speaking almost simultaneously, Mr. Clarke and Mr. Kubrick<br />

said that they hoped their film would give people a real<br />

understanding of the facts and of the overwhelming implica-<br />

tions that the facts have for the human race.<br />

We asked when the film will be released.<br />

Mr. Kubrick told us that they are aiming for December, 1 966,<br />

and explained that the longest and hardest part of the job will<br />

be designing the "tricks," even though the ones they plan to use<br />

are well within the range of modern cinematic technology.<br />

When we had been talking for some time, Mr. Clarke said<br />

he had to keep another appointment, and left. After he had<br />

gone, we asked Mr. Kubrick how Dr. Strangelove had been received<br />

abroad. It had been shown all over the world, he told<br />

us, and had received favorable criticism everywhere except,<br />

oddly, in Germany. He was not sure why this was, but thought<br />

it might reflect the German reliance on our nuclear strength<br />

and a consequent feeling of uneasiness at any attempt to make<br />

light of it. He said that his interest in the whole question of<br />

nuclear weapons had come upon him suddenly, when it struck<br />

him that here he was, actually in the same world with the hydrogen<br />

bomb, and he didn't know how he was learning to live<br />

with that fact. Before making Dr. Strangelove, he read widely<br />

in the literature dealing with atomic warfare.<br />

We said goodbye shortly afterward, and on our way out a<br />

phrase of J. B. S. Haldane's came back to us: 'The Universe<br />

is not only stranger than we imagine; it is stranger than we can<br />

imagine."<br />

!

"I know I've never completely<br />

freed myself of the suspicion that<br />

there are some extremely odd things<br />

about this mission."<br />

Kubrick's original plan was to open 2001 with a<br />

ten-minute prologue (35mm film, black and white) —<br />

edited interviews on extraterrestrial possibilities with<br />

experts on space, theology , chemistry, biology, astronomy.<br />

Kubrick says that he decided after the first screening<br />

o/2001 for M-G-M executives, in Culver City, Cali-<br />

fornia, that it wasn't a good idea to open 2001 with<br />

a prologue, and it was eliminated immediately.<br />

Partially edited transcripts of interviews follow.<br />

Academician A.I. Oparin<br />

Director, A.N. Bach Institute of Biochemistry<br />

Academy of Sciences of the U.S.S.R., Moscow<br />

The origination of life is not an extraordinary event, a lucky<br />

circumstance, as has been a general concept until quite recently;<br />

it is an inevitable phenomenon, part and parcel of the universal<br />

evolution. In particular, our terrestrial form of life is a result<br />

of the evolution of carbonic compounds and multimolecular<br />

systems formed in the process of this evolution.<br />

Could similar phenomena occur on other celestial bodies? We<br />

can observe the initial stages of evolution everywhere on various<br />

celestial objects. There can be no doubt of the existence of<br />

highly molecular complex organic substances on such objects<br />

as the Moon or Mars. Even if these substances could not be<br />

formed on those planets, they could be brought there by falling<br />

meteorites.<br />

For evolution to have taken place on Earth, large expanses of<br />

water were necessary, which we could not observe and did not<br />

even expect to find on the Moon or Mars.<br />

However, in the process of evolution of these planets, at the

28 The Making of Kubrick's 2001<br />

initial stage, these planets, for instance, Mars, could be more<br />

rich in water, and life could have emerged there along the same<br />

lines as on the Earth, and, having once emerged, it could develop<br />

and adjust to those severe, I would say unbearable for<br />

human beings, conditions existing on these celestial objects.<br />

We possess, so to say, a single copy of the Book of Life, that of<br />

terrestrial life, while the knowledge of other forms of life could<br />

tell us about our past and, what's more, it could supply us with<br />

many clues as to our future. The discovery of new forms of life<br />

superior to ours would immensely enrich our culture and expedite<br />

our development.<br />

Thus, human venture into space, direct perception of the solar<br />

system and, in particular, of Earth-type planets will add much<br />

to our perception of life and its development.<br />

I doubt if we can seriously talk of any visits to the Earth from<br />

outer space that took place in the past. It is still the sphere of<br />

science fiction more than that of science. Of course, science<br />

fiction is fine in its own right; however, we should in all honesty<br />

say that the boundaries of our knowledge are but too far from<br />

the point where we could seriously discuss this problem without<br />

having any evidence whatsoever of communications of this<br />

nature.<br />

Doubtless, a great number of complex and highly developed<br />

forms of the evolution of matter are to be found in the limitless<br />

expanse of the universe. But it is in no way imperative that we<br />

call these forms "life" or consider them such, as they differ in<br />

principle from our terrestrial form of life. It is my opinion that<br />

should we come across such phenomena in the process of our<br />

increasing space effort, we can work out some name other than<br />

"life" for them.<br />

We can hardly expect to find anywhere in space human beings<br />

or living organisms morphologically similar to those of our<br />

terrestrial world. I presume the highly organized forms that<br />

may be found elsewhere in the universe are completely different<br />

in their appearance, which does not, however, rule out the<br />

possibility of finding intelligent life of a new type, other than<br />

our terrestrial life. Taking into consideration a great number of<br />

planetary systems within our galaxy alone, there exists a strong<br />

probability of finding one or several planets similar to ours.<br />

However, the development of life is such a complex process<br />

that, even in this case, full coincidence of the forms of life on<br />

these duplicated planets with our terrestrial form of life is hardly

Interview with Dr. Harlow Shapley 29<br />

possible. These forms may be very close; however, certain distinctions<br />

will be observed.<br />

Dr. Harlow Shapley<br />

Paine Professor of Practical Astronomy Emeritus<br />

Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts<br />

Q: Dr. Shapley, what arguments mitigate against there being<br />

life on planets other than Earth?<br />

The thought is rather clear that we aren't going to have life in<br />

our solar system, because of the temperature problem. We can't<br />

have life without it being metabolic or metabolism-working —<br />

and it's not going to work if the water is all frozen or steamed<br />

away. We need water in a liquid state, and that we don't think<br />

we have much of in this solar system, and so that is the argument<br />

that mitigates having life as we know life, as we practice<br />

life, in this solar system. But there are a lot of other systems<br />

which we could have life on. In fact, it would do for me to point<br />

out that our studies of the number of galaxies and the number of<br />

stars in galaxies in all lead us to the conclusion that there must<br />

be something like ten to the twentieth — at least ten to the twentieth<br />

power stars: ten to the twentieth, that's a pretty big number,<br />

but if you write down one and put twenty zeros after it that<br />

would be the way it would look if you were expressing it in<br />

numbers. Well, that's a whole lot of stars, and suppose we say<br />

that only one in a billion, one in a thousand million, is suitable<br />

for life, we'd still have a tremendous number— we would have a<br />

hundred thousand million galaxies and stars that might harbor<br />

life. If only one in a million were comfortable, we would still<br />

have an enormous amount of life.<br />

We are peripheral — I like to use that word. I mean we are on<br />

the edge; we are not in the center of a galaxy, we are not important<br />

in a galaxy, we're just here.<br />

Of course, we ought to define life, shouldn't we — we should<br />

define life — and many people take shots at it, but I think the<br />

simplest one is to say that life is an activity of replication of<br />

macro-molecules. The macro-molecules, when they divide up,<br />

are self-replicating and represent what we would call life metabolic<br />

operations.<br />

On Mars the conditions are so poor that I would not want to<br />

gamble that we are going to find life — but we are going to send<br />

apparatus out toward the vicinity of Mars — we are going to

30 The Making of Kubrick's 2001<br />

make a lot of photographs; we are going to do a bit of thinking<br />

on the subject and we may come to the conclusion that Mars<br />

probably does have a low form of operation that we call meta-<br />

bolic life— could be . . .<br />

If one of my graduate students twenty-five years ago had said,<br />

"I want to write or study on the origin of life," I would have<br />

asked him to close the door as he went out and do it quickly,<br />

because you didn't do that then; it wasn't proper, especially for<br />

the young, to commence speculating in a big way about the<br />

origin of life or even the size of the universe.<br />

There is a little point that we are now getting brave enough to<br />

discuss, and that is cosmic evolution. My idea about cosmic<br />

evolution is that everything that we can name — material or immaterial—evolves<br />

and changes with time. It goes from simple to<br />

more complex, or moves away.<br />

We had novae, you see, for that evolutionary step from hydrogen<br />

into helium, burning hydrogen fuel into helium ash; and<br />

now we realize that in the novae we have temperatures that will<br />

take us further up this sequence of atoms.<br />

We now know how the elements evolve. Well, if the elements<br />

evolve that way and biology evolves that way and the stars and<br />

the galaxies evolve that way, we might as well go the whole<br />

distance — say there is a cosmic evolution. The whole works<br />

evolve with time. Time is a factor in the matter — I don't know<br />

what the end is going to be. Some people ask, "What will happen<br />

when we run out of this fuel?" ... I don't know the answer<br />

to that.<br />

Whence came the hydrogen out of which the universe has developed<br />

... we don't know the answers — well, it may come from<br />

twists in the space time. Maybe a source we are building on.<br />

Okay, I say, who is the twister?<br />

Life is going to appear where the chemical conditions are right:<br />

well, they are right now, on the surface of this planet, but back a<br />

few thousand million years ago, when the Earth was cooling off<br />

and rocks would be too hot, the life that could get started there<br />

would not have some of the necessary elements.<br />

It would have methane and ammonia and water vapor and hydrogen<br />

gas and maybe one other. Those were the kind of elements<br />

of molecules that were on the surface of the Earth when<br />

life began. But now we can have those same elements in a labo-<br />

ratory.

Interview with Dr. Harlow Shapley<br />

Out in space, of course, you have electrical discharges from<br />

lightnings and, let us say, at the primal atmospheres . . . and<br />

*<br />

3<br />

you<br />

have these that I have just named — ammonia, methane, water<br />

vapor, hydrogen gas. You had those out in space, but we can<br />

have them in the laboratory.<br />

That is what Stanley Miller, under the guidance of Harold Urey<br />

and some of the rest of us, put our oars in, what we could do<br />

also on the surface of the Earth. And so we set up a laboratory<br />

in Chicago that had just those things. . . . We didn't have any<br />

lightning from outer space, but we could put in electric discharges,<br />

which we did. Stanley Miller one day told me, he could<br />

see that his apparatus was showing something pink in what was<br />

otherwise a transparent gaseous medium. He let it run for a<br />

week. At the end of that week it was decidedly pink. And then<br />

he stopped his experiment and analyzed what he had done. He<br />

had used the same machinery that omnipotence — if there be<br />

such — could use, and we used it and he tested it and he used<br />

the new techniques that we don't know much about — mainly<br />

chronographic analysis — and what happened? He analyzed it<br />

and found he had amino acids, and that was one of the big<br />

jumps ... I would say it was one of the best experiments of the<br />

last ten years.<br />

First, just two or three, and then, at the end of the year, all<br />

twenty of the commonly accepted amino acids were found in<br />

this University of Chicago laboratory experiment. And that, of<br />

course, is a tremendous thing ... a step toward life, because<br />

amino acids are what proteins are made of, and proteins are<br />

what human beings are made of. So we found out how to do<br />

those things, and since then we don't need to appeal to the Almighty,<br />

I mean, to the supernatural, or to miracles for the origin<br />

of life. We know the tricks of how it can be done. How it undoubtedly<br />

was done on this peripheral planet in this one solar<br />

system and probably elsewhere.<br />

Who is — what is, aware? Is a dog aware of himself ... is a fish<br />

aware of himself ... is this amoeba of mine aware? It knows that<br />

one thing is edible and digestible, and another is not. So intelligence,<br />

to me, is just a matter of degree.<br />

Francis J. Heyden, SJ.<br />

Professor & Head of Dept. of Astronomy<br />

Georgetown University<br />

Washington, D.C.<br />

Now, as far as religion is concerned, I do not know of any<br />

1

3 2 The Making of Kubrick's 200<br />

eleventh commandment that says: 'Thou shalt not talk to anyone<br />

off the face of the Earth." As a matter of fact, though, this<br />

would be a big problem. I can understand where we would receive<br />

a message from some place out in space, but to talk back<br />

to them and exchange ideas, that I would say is close to physically<br />

impossible for the present, because all our communication<br />

is done by means of electromagnetic radiation, which travels at<br />

the speed of light. So that even if someone on a planet near the<br />

closest star were to send a message to us, it would take four-anda-half<br />

years from the time he said "hello" there until we heard<br />

it here; by the time we answered "glad to hear from you" and<br />

"how are you?" it would be four-and-a-half years before he got<br />

our answer. So you see, it would take quite a lifetime just to<br />

have a very casual passing of the time of day.<br />

If it doesn't look like man at all and it is intelligent, we could<br />

communicate with it and have an exchange of ideas. I do not<br />

know whether we would call it man or not. We don't call angels<br />

men, but all through the Old Testament we have had constant<br />

references to certain angels who are pure spirits— who have<br />

been messengers of God to men.<br />

On this question of the meaning of religion in exploration of life<br />

outside of our own Earth— whether that life be on one of the<br />

planets in space, or whether it be on even some star in a solar<br />

system all of its own, we would only have one question that<br />

would come up and that would be the question of the fall of<br />

Adam and Eve and the inheritance that we have gotten from<br />

that fall. These people probably never had an Adam and Eve<br />

who ran into trouble in Paradise and got thrown out. Possibly<br />

they are in what the philosophers and theologians of the Mid-<br />

dle Ages referred to as the state of pure nature, meaning that<br />

they do not have the darkened intellects and the weakened wills<br />

that we have, and therefore if we met them we would probably<br />

meet some of the finest guides and consultants and intelligent<br />

people that we could ever run into. It would be most beneficial<br />

for us. On the other hand, if the fall of Adam and Eve had been<br />

repeated, we might meet some people that would benefit by the<br />

same fruits of the redemption that we do, who would understand<br />

us, and speak almost the same language. But this is all<br />

speculation.<br />

A being anywhere in space is a creature of God. So that if you<br />

even meet some living thing on the most distant galaxy, it would<br />

be a creature created by the same God that made us all.<br />

In some respects, I suspect that eventually we may know, too,<br />

that we have the same biological or vital laws throughout the<br />

whole universe.<br />

1

Interview with Dr. Francis J. Heyden 33<br />

God can be known by any intelligent being. It is the belief of the<br />

philosophers, starting with Aristotle, and those who preceded<br />

him even, that an intelligent man looking at the wonders of<br />

nature — studying them, either from the standpoint of science or<br />

admiring them simply from the standpoint of beauty, with order<br />

and variety, to them . . . will come to the realization that there is a<br />

supreme being, or a God. On the other hand, we know from the<br />

Bible that God has revealed Himself to mankind on this Earth<br />

in a very, very special way, in order to help us appreciate Him<br />

more and more, or to come to know Him better. Now, as far as<br />

other beings in space are concerned, if they are intelligent they<br />

will know God the way a scientist would know Him — or the<br />

way Aristotle and other great philosophers down through the<br />

ages have instructed us that we can argue from the conditions of<br />

things in this world to the existence of a supreme being. Since<br />

we are intelligent, we would understand that God who made us<br />

is also intelligent. But we might not know whether or not these<br />

people have as full an understanding of God as we have through<br />

Revelation until we found out what form of Revelation was<br />

given to them.<br />

What could man learn from contacting extraterrestrial intelligence?<br />

First of all, the extraterrestrial might know more than<br />

we do. We might get answers to a lot of things; but it would depend<br />

on whether or not we could contact him directly and not<br />

wait for the long time-lag between question and answer, perhaps<br />

as long as a couple of hundred years. On the other hand,<br />

he might be just giving out information, and as we gathered it in<br />

and interpreted it, we would be advancing our own reservoir of<br />

knowledge in any field that he happened to be communicating to<br />

us. In addition to that, I would say this: that the satisfaction of<br />

knowing that there is someone else out in space, who is able to<br />

communicate by intelligent signals, is a great advance in our<br />

own knowledge — and that helps us, I think, to appreciate the<br />

position that we have in this universe and our own role in the<br />

universe.<br />

It is sometimes suggested to me that possibly there is a conflict<br />

over investigating whether or not there are intelligent beings<br />

somewhere else than on this Earth. People very often feel that<br />

we have been put here on this Earth to stay, and that is where<br />

we are going to stay, and that space is God's locker— we are not<br />

supposed to pry into it. I do not believe that; after all, we do<br />

have the psalm that says, 'The Heavens tell of Thy Glory, O<br />

God" and also, as a philosopher, we have the urge to learn as<br />

much as we can. We have restless minds as well as bodies.<br />

Minds that are always inquiring into things, to learn how they

34 The Making of Kubrick's 2001<br />

are made .<br />

they work .<br />

. . how . . what they are; and there is<br />

nothing in all of Revelation that is against learning more and<br />

more. As a matter of fact, I think myself that the man with<br />

what I call "scientific faith" is much more at rest in his soul<br />

than one who is just satisfied with what he knows from reading<br />

the scriptures.<br />

There has always been the attitude among believers as far back<br />

as we go in the history of religion that God is in His Heaven -<br />

God is above. One reason for that, of course, is that we are<br />

conscious that we don't see God face-to-face here on this Earth,<br />

and we have been accustomed to the beauties of, let us say, a<br />

sunset. If you stand looking at the sun as it sets, this beautiful<br />

panorama in the sky, something like Shelley's "In the golden<br />

glory of the setting sun, o'er which clouds are brightening" -<br />

and so on - 1 can see where a person might want to make that a<br />

sort of a shrine for himself. I can see and understand the idea of<br />

a sun worshiper . . . just from that; and I think that it is because<br />

of that we are inclined to place the residence of all divinity in<br />

space or up in the Heavens above: because there is so much<br />

beauty and so much wonderment there that we do not understand.<br />

But again, as one having scientific faith, I know that God<br />

is everywhere and that God is as much in my little finger as he<br />

is in the most distant star.<br />

There is a great conservatism among some people who feel we<br />

are not supposed to pry into, let us say, the mysteries of space.<br />

This is, of course, against all of the efforts of astronomers from<br />

time immemorial who have tried to know more and more about<br />

the stars and about the planets and the laws of their motion.<br />

What a tremendous achievement it was when, first of all, Johannes<br />

Kepler found from observational data the three laws of planetary<br />

motion, and having approached his goal from observational<br />

data, he was followed about two generations later by Isaac<br />

Newton, who started out with a theory, and from his theory of<br />

gravitation derived the same three laws that Kepler had gotten<br />

from observation. This is a real scientific advance. I do not<br />

think anyone in the world is ashamed of it. As a matter of fact,<br />

putting a satellite in orbit about the Earth in this generation —<br />

and I think we do live in a wonderful generation of discovery<br />

was an achievement of a dream that Isaac Newton had. Isaac<br />

Newton suggested that we put a cannon on top of a high mountain<br />

and fire a projectile parallel to the direction of the gravity<br />

of the Earth at such a speed that the cannonball would go in orbit<br />

about the Earth. No one would say that we have done wrong by<br />

launching artificial satellites.' We have actually achieved something<br />

that is worth all the money that we have put into the space<br />

—

Interview with Gerald Feinberg 35<br />

effort at present. The weather satellite and communications<br />

satellites are examples. Now if we are to go further in our in-<br />

vestigations of space, I do not think that we are going to violate<br />

any law of God. I don't think any conservatism on the part of<br />

people should have any influence on us.<br />

The origin of life on the Earth is a question that ... I do not<br />

know if it is ever going to be solved. On the humorous side, we<br />

have some people who think that it evolved from some garbage<br />

that was left behind after the crew of a spaceship stopped here<br />

one time, had a picnic, and then departed for another planet.<br />

Other people believe that life started after a molecule had been<br />

developed to a certain degree of complexity, so that it would<br />

support life such as DNA. This happened after the conditions<br />

for life, such as the right temperature, and other chemical requirements,<br />

such as free oxygen and water, were formed. Then,<br />

somehow or other, a pre-life germ or some sort of impulse<br />

started the life process going, and you had your very simple<br />

cells gradually becoming complicated animals. Eventually, out<br />

of it all, came the body of an animal that God decided to give a<br />

human soul and call man. This is all right if you want to believe<br />

in that form of evolution, as long as you remember that the human<br />

soul that we have is not something that evolved out of a<br />

chemical test tube, or whatever you had in the early stages of<br />

development of the Earth. We know that life did not always<br />

exist on this Earth — we know that living forms have changed<br />

and do change over long periods of time on the surface of the<br />

Earth . . . but, all we do have is a brief history of homo sapiens,<br />

of the intelligent man. We do not know exactly where he came<br />

from, how long he has really been here.<br />

Gerald Feinberg<br />

Professor of Physics, Columbia University<br />

New York<br />

I think men will travel to the stars sooner or later; the factors<br />

that will decide this are that some men want to, and that even<br />

today we can think of ways in principle by which it can be accomplished.<br />

Some scientists have said that the stars are too far<br />

away for us to ever reach them. But distance by itself doesn't<br />

mean anything. Distance is equal to speed multiplied by time,<br />

and if relativity and the amount of energy available keep us<br />

from traveling too fast, we can always try to extend the amount<br />

of time we have available. There are various ways we could do<br />

this. One is by extending the human life span, which would be a<br />

good idea for other reasons, also. Another would be by some<br />

kind of suspended animation for the travelers, either by lower-

36 The Making of Kubrick's 200<br />

ing their body temperature, or by some kind of chemicals which<br />

decrease the rate of metabolism. Already some scientists are<br />

working on methods like this. So I think that sooner or later it<br />

is pretty likely that some men from Earth will travel to other<br />

planetary systems.<br />

I think that in a million years the human race would be able to<br />

do anything one can think of right now, that doesn't specifically<br />

violate the laws of nature; and, perhaps, many things that we<br />

think of as violating the laws of nature. So, by extension, I<br />

would say that some other form of intelligent life, which is already<br />

a million years ahead of us, would be able to do all of<br />

those different things.<br />

Some of the things that such an intelligent race might do would<br />

be astronomical changes, like making their planets move differently,<br />

or perhaps even arranging them into some kind of<br />

geometrical array which had some value for whatever their<br />

purposes were. I think they would also do a great deal to reshape<br />

their own biology. Even if a race is much more intelligent<br />

than we are, it's unlikely that they would have reached any<br />

kind of perfection: so one of the things I foresee an intelligent<br />

race wanting to do is to make itself even better than it is. I<br />

think we'll do that to ourselves sooner or later, and I expect<br />

that another race would do the same thing.<br />

It is a little surprising that if there are superintelligent races<br />

around, we haven't seen some indication of them. One possi-<br />

bility is that they had visited us, say half a million years ago,<br />

when there probably wasn't anybody around to know that we'd<br />

been visited. But the Earth has been around for a very long<br />

time, and man, at least in his present form, has been here only<br />

one ten thousandth or so of the life of the Earth, so that the<br />

chances that we would have been visited while we were able to<br />

recognize it is pretty small.<br />

We're just beginning to get some idea of how we can manipu-<br />

late the genetic pattern to influence the functions of living cells.<br />

If we can do that, then I think it should be possible to produce<br />

human beings who can also think better and faster than we can.<br />

In fact, I think it's a very exciting prospect that fairly soon<br />

there'll be some kind of intellectual relationship between men<br />

and machines, in which each of us contributes those aspects of<br />

thought that we can do best. I think this is something very much<br />

in the cards, and something which I myself am looking forward<br />

to with a great deal of interest.<br />

But I don't think that the outlook for electronic machines is so<br />

1

Interview with Gerald Feinberg 37<br />

poor, either. There are many advantages that electronic machines<br />