Rory Sherlock - Architectural Association School of Architecture

Rory Sherlock - Architectural Association School of Architecture

Rory Sherlock - Architectural Association School of Architecture

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

The Phidian Fallacy:<br />

Dispelling Vanity in the Architect’s Self-‐Portrait.<br />

<strong>Rory</strong> <strong>Sherlock</strong><br />

Tutor: Ryan Dillon<br />

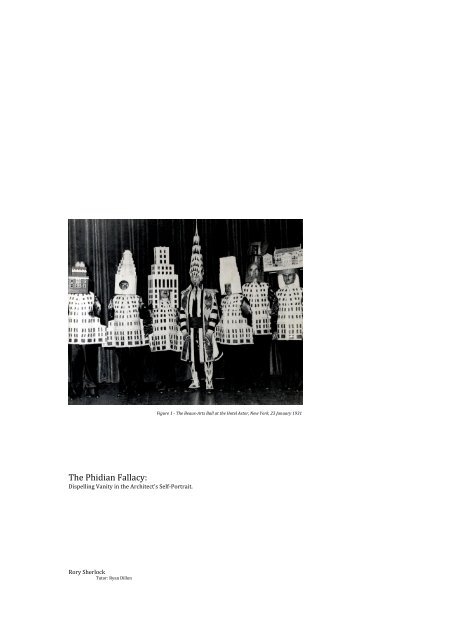

Figure 1 - The Beaux-Arts Ball at the Hotel Astor, New York, 23 January 1931

‘The first right on earth is the right <strong>of</strong> the ego’<br />

-‐ Howard Roarke 1<br />

Phidias (circa 480 – 430BC) is widely regarded as the greatest<br />

and most famous sculptor in ancient Greece. Renowned for his<br />

unbridled skill, delicacy and tact, he single-‐handedly revolutionised his<br />

art, with colossal sculptures <strong>of</strong> the Gods so unfathomably magnificent in<br />

their representation and composition, that it was said that ‘he alone had<br />

seen the exact image <strong>of</strong> the Gods and that he revealed it to man’ 2. He<br />

was the artistic director <strong>of</strong> the Parthenon and several other projects,<br />

and his statue <strong>of</strong> Zeus at Olympia was one <strong>of</strong> the Seven Wonders <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Ancient World.<br />

However, in spite <strong>of</strong> his overwhelming talent and fame, Phidias was not<br />

immune to criticism and made one catastrophic, yet seemingly<br />

inconsequential error. While carving his colossus <strong>of</strong> Athena Parthenos,<br />

destined to sit at the heart <strong>of</strong> the Parthenon, upon the Amazonomachy<br />

<strong>of</strong> the goddess’ shield he ‘included his own self-portrait among the<br />

reliefs’ 3. A signature; a trifling stamp <strong>of</strong> the artist himself upon his great<br />

work.<br />

This minor gesture, however, was construed as such a pr<strong>of</strong>ane act <strong>of</strong><br />

vanity and self-‐flagellatory arrogance by his rivals and the Athenian<br />

authorities, that he was imprisoned for his insolent egoism, until his<br />

ultimately sick, slow death. Phidias had stamped his own face upon the<br />

image <strong>of</strong> a deity, and in this fleeting act, had cemented in the opinion <strong>of</strong><br />

the viewers <strong>of</strong> his great work, the loathsome and to many,<br />

preposterous, notion that he considered himself above all others to<br />

warrant a place among the pantheon. Phidias, it appeared, fancied<br />

himself a God. And people hated him for it.<br />

Such proclamations <strong>of</strong> seeming self-‐worth and inflated egotism have,<br />

historically, never canvassed much favour with the general public,<br />

myself certainly included, in any field, be it architecture, art, politics or<br />

otherwise. The idea that somebody could hold themselves in such high<br />

regard, coupled with the possible fear that the person in question could<br />

in fact be more powerful, more knowledgeable, better, in that they, over<br />

all others are granted the freedom to undertake such projects in the<br />

public domain, makes him loathsome in the eyes <strong>of</strong> those who<br />

encounter his creations. Friedrich Nietzsche, in Thus Spoke Zarathustra,<br />

neatly summed up this sentiment;<br />

‘So I shall speak to them <strong>of</strong> the most contemptible man: and that is the Ultimate Man.’ 4<br />

Now, architects in the public eye have, traditionally, shared this<br />

somewhat reprehensible habit for bold statements concerning<br />

themselves and their subject; a habit that has its roots in Individualism.<br />

Adolf Loos talked <strong>of</strong> his aristocratic architectural ideal, <strong>of</strong> how he<br />

understands, as an architect, that ornamentation is detrimental, yet he<br />

‘can accept the African’s ornament … my shoemaker’s, for it provides the<br />

high point <strong>of</strong> their existence, which they have no other means <strong>of</strong><br />

achieving’ 5. Upon first reading this passage, I was incredulous. The very<br />

thought <strong>of</strong> someone being able to muster such genuine, unadulterated,<br />

wild condescension, to place themselves on a pedestal <strong>of</strong> such<br />

1 Rand, Ayn, ‘The Fountainhead’, Film, King Vidor, 1949<br />

2 Encyclopedia Britannica, ‘Phidias’, Online Edition, 2012<br />

3 Plutarch, Perikles, 13.31-‐2<br />

4 Nietzsche, Friedrich, ‘Thus Spoke Zarathustra’, Penguin Classics, 2003, p.45<br />

5 Loos, Adolf, ‘Ornament and Crime: Selected Essays’, Ariadne Press, 1998, p.174<br />

2

empyrean height from which to look down on the rest <strong>of</strong> humanity, in a<br />

serious academic piece <strong>of</strong> writing, blew my naïve mind. What became<br />

immediately clear, though, was that this must surely have been the<br />

response to Phidias’ gesture, over two millennia ago. However, no<br />

matter how contemptible such outbursts may seem, they are<br />

undeniably marks <strong>of</strong> the individual, signs that those in question have<br />

unmoving and total belief in themselves and their work.<br />

The character <strong>of</strong> Howard Roarke in Ayn Rand’s seminal novel, The<br />

Fountainhead, is clearly an exaggeration <strong>of</strong> this architectural, individual<br />

ideal, though he represents a very real desire. He is, rather than an<br />

exaggeration, an extrapolation <strong>of</strong> the real-‐life architect. Within the<br />

architectural pr<strong>of</strong>ession, (more so than most others, since the products<br />

<strong>of</strong> the work are to be seen in the public domain) everybody strives to<br />

make their mark, in their own specific way (even those who conform<br />

must design in their way) and as such everyone has their own opinions<br />

on what is the best, what is right. Frank Gehry once said,<br />

‘There are sort <strong>of</strong> rules about architectural expression which have to fit into a certain<br />

channel. Screw that! It doesn’t mean anything. I am going to do what I do best and if it’s<br />

not good the marketplace will deny it.’ 6<br />

Given this individualist outlook, every building designed by an<br />

individual architect, (this point must be carefully stressed, for many<br />

architects do not necessarily share this individualist ideal) like works <strong>of</strong><br />

art or sculpture, painted or carved by an artist, become, on some level, a<br />

personal reflection on their creator. If the architect truly believes that<br />

their view is the right one, that their design is better than all the others<br />

for a building, then their work, ultimately, is a representation <strong>of</strong> their<br />

self. This faith, then, in their own individual capabilities and opinions,<br />

turns every work <strong>of</strong> the architect, to a certain degree, into a self-‐<br />

portrait.<br />

Here, then, there begin to some appear potent and noteworthy parallels<br />

between the architect and Phidias. Firstly, the former, akin to the latter,<br />

has an inclination towards bold statements, which don’t necessarily<br />

work in their favour so far as winning people over is concerned.<br />

Additionally, they are both concerned with producing work in the<br />

public eye and the view <strong>of</strong> others, and yet for the inclusion <strong>of</strong> their self-‐<br />

portraits are castigated and scorned for their pride. It must be noted<br />

that not all architects are branded as vain, and this certainly has a<br />

certain degree, to do with the ‘starchitect’, however what I wish to focus<br />

on is instances <strong>of</strong> individualism, such as those <strong>of</strong> Howard Roarke, in<br />

which it is perceived that an architect gets carried away with his own<br />

sense <strong>of</strong> self-‐worth and the value <strong>of</strong> his ideas in the design <strong>of</strong> a building,<br />

the same crime attributed to Phidias. It is in such cases <strong>of</strong> the individual<br />

architect that the response to their work errs on the side <strong>of</strong> public<br />

frustration and the ultimate and woeful brand <strong>of</strong> vanity.<br />

So who is this man, he that holds himself in such high regard and<br />

delirious vainglory as to tell we, the public, what is best for us? Why is<br />

his opinion right, and why do we care who he is? It is this line <strong>of</strong><br />

questioning and this <strong>of</strong>ten brash ascription <strong>of</strong> vanity to an artist or<br />

architect, whose works are available and constant in the public view,<br />

with which I wish to quarrel, and to this I denote the title <strong>of</strong> the Phidian<br />

Fallacy. Fallacious, because I feel that this stamp <strong>of</strong> vain pride and<br />

narcissism with which we are so happy to brand artists and architects<br />

for statements and demonstrations <strong>of</strong> perceived wanton egotism, the<br />

6 Gehry, Frank, ‘Sketches <strong>of</strong> Frank Gehry’, film, Sydney Pollack, Sony/WNET, 2000<br />

3

cause <strong>of</strong> Phidias’ imprisonment and eventual death, is improper.<br />

Defined as ‘excessive pride in or admiration <strong>of</strong> one’s own appearance or<br />

achievements’ 7 vanity, it seems, finds its fault in pride. Architects do<br />

seem to have this habit <strong>of</strong> grandiose statements <strong>of</strong> their self-‐worth and<br />

pride in their work, but is this really so wrong; a cause for<br />

condemnation? Was Phidias’ gesture as self-‐centred as it may, on the<br />

face <strong>of</strong> it, seem? Focussing more closely on this self-‐representation in<br />

art and architecture, what is it about the inclusion <strong>of</strong> the self, this<br />

passing act <strong>of</strong> personal reflection within a work, that can elicit a<br />

response <strong>of</strong> such outrage?<br />

To address this issue, the whole notion <strong>of</strong> self-‐representation and its<br />

emergence in the aesthetic ‘arts’; that vast umbrella under which<br />

architecture now seems to find itself situated and sheltered from the<br />

clinging deception that hangs thick in the air <strong>of</strong> academic ambiguity,<br />

must be considered. To understand whether this vanity, this pride in<br />

one’s own work, is deserved <strong>of</strong> its delegation as a deadly sin when it<br />

comes to the architect, it must first be questioned where this desire for<br />

self-‐representation originates. Why did Phidias feel the need to include<br />

himself in his sculpture at all? Why do architects feel the need to imbue<br />

their buildings with their personality, and why is this so vehemently<br />

rejected by the public and denounced with such vigour? Are we really<br />

so vain?<br />

The self-‐portrait has existed since long before Phidias’ unfortunate<br />

debacle. Since humans first glimpsed their own reflections, those<br />

tentative first narcissi, we have been fascinated with the image <strong>of</strong> the<br />

self. However, it was not until the advent <strong>of</strong> cheaper and better quality<br />

mirrors, and the increased interest in the self as a subject during the<br />

early renaissance in the mid 15 th century that the self-‐portrait in art as<br />

we know it today emerged 8.<br />

The methods and reasoning for self-‐portraiture are numerous and far-‐<br />

reaching, and have evolved greatly over the millennia. Phidias carved<br />

out his portrait as an inclusion within a much larger work. Until this<br />

emergence <strong>of</strong> the self-‐portrait as a distinct and sole project in the early<br />

renaissance, almost every prior incidence <strong>of</strong> its existence was within a<br />

larger context. This would <strong>of</strong>ten be as a banal means to fill numbers in a<br />

crowd, for example, if a painter couldn’t afford more models. However,<br />

a painter would <strong>of</strong>ten, and more interestingly, include himself within a<br />

scene by way <strong>of</strong> a signature. Jan Van Eyck famously depicted himself<br />

within his works, most notably in his 1434 painting, ‘Wedding Portrait’,<br />

in which a young couple face the viewer, exchanging vows. In the<br />

distant background <strong>of</strong> the room, Van Eyck can be seen reflected in the<br />

mirror, the inscription above it reading ‘Johannes de Eyck fuit hic’; ‘Jan<br />

Van Eyck was here’ 9 (figure 2).<br />

This placement <strong>of</strong> the self portrait within an artist’s own work, and<br />

many others like it, was met with considerably less commotion than the<br />

case <strong>of</strong> Phidias, and the architect. But what’s the difference? It seems<br />

that a work such as this one, the intention <strong>of</strong> which is aesthetic beauty<br />

for either its creator or the commissioning party behind it, the inclusion<br />

<strong>of</strong> the artist himself is seen as a mark <strong>of</strong> authenticity, a valuable<br />

signature on an admirable work. Ins<strong>of</strong>ar as the architect is concerned, if<br />

they are well known enough, the patent inclusion <strong>of</strong> their own self-‐<br />

7 Oxford English Dictionary Online, 2012<br />

8 ‘Self Portrait’, UMBC Educational Pages Online, 2012<br />

9 Van Eyck, Jan, ‘Wedding Portrait’, 1434<br />

4

Figure 2 - Detail from ' Wedding portrait', Jan Van Eyck, 1434<br />

5

portrait may in some cases serve this novel purpose <strong>of</strong> confirming or<br />

ascribing some value to the work, however, purely on this level (<strong>of</strong><br />

going some way towards authenticating a work, or giving it value) it<br />

rarely does much to sway the people whom are affected by its<br />

existence. Similar to Phidias carving his face onto his deity, the<br />

inclusion <strong>of</strong> an architect’s self-‐portrait within his work more <strong>of</strong>ten than<br />

not is met with a somewhat more frosty reception.<br />

Seemingly patent vanity in this sense, though, is not particularly<br />

difficult to find amongst the work <strong>of</strong> artists, even when it is not<br />

necessarily commissioned to create a point <strong>of</strong> contact between the<br />

heavens and the earth. Diego Velázquez, in his 1656 painting ‘Las<br />

Meninas’ rather than painting a portrait <strong>of</strong> King Philip IV <strong>of</strong> Spain, the<br />

model sitting for the picture, he paints a portrait <strong>of</strong> himself instead.<br />

Now, this, clearly, is a somewhat curtailed and dramaticised description<br />

<strong>of</strong> the work, yet the sentiment rings true. There are many parallels<br />

between this painting and the tale <strong>of</strong> Phidias or the architect; the focus<br />

<strong>of</strong> the work is, in fact, on someone else, the self-‐portrait is merely an<br />

aside (although a considerably more prominent one in this case), the<br />

painting was for a King, not quite a deity but greater (possibly) than the<br />

public. Once again, though, rather than fury, the work was met with<br />

esteemed commendation. It was described as "Velázquez's supreme<br />

achievement, a highly self-‐conscious, calculated demonstration <strong>of</strong> what<br />

painting could achieve, and perhaps the most searching comment ever<br />

made on the possibilities <strong>of</strong> the easel painting" 10. High praise indeed.<br />

Why then was this self-‐reflection so distinct, so praiseworthy? Surely, if<br />

Phidias was jailed for his pride and vanity, Velázquez should have<br />

suffered the same fate?<br />

Furthermore, what then <strong>of</strong> the self-‐portrait as an entirely distinct work?<br />

Is this intricate study <strong>of</strong> one’s own features, the self, and its display as a<br />

piece <strong>of</strong> interest for public view, not a mark <strong>of</strong> vanity? Is it not vain to<br />

paint a picture <strong>of</strong> yourself, and to think this will be <strong>of</strong> interest to others?<br />

Since Jean Fouquet painted what is widely agreed to be ‘the earliest<br />

identified self-‐portrait, that is a separate painting, not an incidental part<br />

<strong>of</strong> a larger work’ 11, self-‐portraits have become a distinct art form in<br />

their own right. After this ice-‐breaking moment, there was a vast<br />

proliferation in the self-‐portrait as an individual work. Painters would<br />

originally study themselves for the purposes <strong>of</strong> furthering their skills as<br />

a fine artist, without the need to hire a model, <strong>of</strong>ten even drawing<br />

themselves as prominent historical figures as a method <strong>of</strong> self-‐<br />

promotion. Francisco de Zurbarán painted a self-‐portrait, ‘Saint Luke as<br />

a painter, before Christ on the Cross’, (Figure 3) in which he depicts<br />

himself as Saint Luke, stood before Jesus, head hanging, haggard and<br />

pale, nailed to the cross. This image should, by all accounts, be the<br />

ultimate icon <strong>of</strong> utter pride and self-‐centered pr<strong>of</strong>anity; a milestone in<br />

the ultimate subversion <strong>of</strong> the creator’s own self-‐worth and the product<br />

<strong>of</strong> their labour. Jesus Christ himself has become the secondary character.<br />

Saint Luke, defaced, is shown as the painter himself, and as such takes<br />

on prominence as the most interesting feature <strong>of</strong> the work; head held<br />

high, lit from the heavens, gazing up to the Son <strong>of</strong> God with a look <strong>of</strong> pity.<br />

It’s mind boggling stuff, it really is.<br />

However, at this point, it must be noted that in its transition into the<br />

modern era, the self-‐portrait endured a major shift in its rationale, and<br />

its reception, that makes apparent they key separation between the<br />

10 Honour and Fleming, ‘A World History <strong>of</strong> Art’, Laurence King, 1982, p.447<br />

11 Janson, H.W, ‘History <strong>of</strong> Art’, Harry N. Abrams Inc., 1986, p.386<br />

6

Figure 3 - 'Saint luke as a Painter, Before Christ on the Cross', Francisco de Zurbaran, 1630-<br />

1639<br />

7

aesthetic self-‐representation portrayed by the artist and that <strong>of</strong> the<br />

architect. The self-‐portrait became instrumental as a form <strong>of</strong> self-‐<br />

analysis, beyond merely the physical. This form <strong>of</strong> self-‐representation<br />

in the modern sense, far from being a vain act, is more <strong>of</strong>ten an attempt<br />

at a description <strong>of</strong> the person behind the work and their mental state,<br />

warts and all. The self portraits <strong>of</strong> Egon Schiele (1890 – 1918) are<br />

startlingly intense, and far from depicting perfection, are more a<br />

revelation <strong>of</strong> the psychology <strong>of</strong> the creative mind behind them. In his<br />

1911 ‘Selbstbefriedigung’, (Figure 4) he paints an image <strong>of</strong> himself<br />

masturbating, sallow and negative. His eyes are hollow and unfocused,<br />

his stature and expression, far from suggesting pleasure, cry out<br />

solitude.<br />

Here then, what becomes clear is that the artists self-‐portrait, as oppose<br />

to that <strong>of</strong> the architect, is not denounced for vanity, because it inherits<br />

interest in the mind <strong>of</strong> its viewers in giving the works <strong>of</strong> a given artist<br />

provenance and context. The works <strong>of</strong> an artist, as with the works <strong>of</strong> an<br />

architect, to an large extent, are greatly concerned with aesthetics.<br />

However, this is as far as the work <strong>of</strong> the artist stretches. The majority<br />

<strong>of</strong> art serves a purely aesthetic purpose, and as such, when we<br />

encounter the self-‐portrait <strong>of</strong> an artist, the experience is one <strong>of</strong><br />

revelation. This self-‐reflection in the modern sense, as we see in the<br />

case <strong>of</strong> Egon Schiele and its heightened openness gives the viewer an<br />

understanding <strong>of</strong> the person responsible for the work, the way he<br />

thinks, his history, and thus why his work looks the way it does, in a<br />

field concerned primarily with aesthetics. It is for this reason that<br />

vanity and pride are <strong>of</strong>ten overlooked, or if not overlooked, are seen as<br />

enhancements in the understanding <strong>of</strong> an artist’s motivation.<br />

Rembrandt, over the course <strong>of</strong> his life, painted over forty self-‐portraits,<br />

his self-‐obsession even stretching to the act <strong>of</strong> making his students copy<br />

these works as part <strong>of</strong> their study 12. However, it is because <strong>of</strong> this<br />

purely aesthetic nature <strong>of</strong> the product <strong>of</strong> the artists labour that we can<br />

overlook this seeming vanity, and dig deeper into the artists motives, as<br />

a means <strong>of</strong> giving increased power to his works.<br />

The works <strong>of</strong> the individual architect, on the other hand, although<br />

certainly concerned with aesthetics, have an intrinsic function as well,<br />

and therefore the intervention <strong>of</strong> their own self is open to far greater<br />

criticism. Questions arise as to whether it deserves to be there, (forced<br />

upon the public, as it were) or whether it is even necessary at all in a<br />

public context. Public works <strong>of</strong> architecture are not designed purely<br />

with the intention <strong>of</strong> satisfying the aesthetic whims and desires <strong>of</strong> a<br />

party with the necessary funds to facilitate such a creation. Phidias,<br />

though an artist, was carving a sculpture with a vastly important<br />

function, in addition to its aesthetic value. His statue was a means <strong>of</strong><br />

connection between the heavens and the earth, an icon for all Greeks to<br />

pray to. In this case, then, the self-‐portrait seemingly has no place at all.<br />

Phidias’ face was not worthy <strong>of</strong> its placement, and as such its reception<br />

was borderline hysterical.<br />

When the work in question has to satisfy a function, whether as a statue<br />

to pray to, or a library to read or work in, for example, the inclusion <strong>of</strong><br />

some essence <strong>of</strong> the self, the creator behind the outcome, is received as<br />

an act <strong>of</strong> severe vaingloriousness. The reception <strong>of</strong> the viewer, far from<br />

overlooking vanity, instead focuses on the function, and if the design,<br />

the personality <strong>of</strong> the architect, overbears this underpinning rationale,<br />

then the accusation <strong>of</strong> self-‐centred pride becomes all the more<br />

12 van de Wetering, Ernst, ‘Rembrandt by himself’, National Gallery, London, 1999, p.10 -‐<br />

8

Figure 4 - 'Selbstbefriedigung', Egon Schiele, 1911<br />

9

prevalent. It seems, when function is attached to aesthetic beauty, who<br />

the creator <strong>of</strong> the work is, becomes <strong>of</strong> little importance to those whom<br />

it concerns and affects. In a recent article on the death <strong>of</strong> world famous<br />

architect Oscar Niemeyer, it was said that<br />

‘His style was not to everyone's taste, and for a communist some people say his work was<br />

not very people-‐friendly -‐ focusing more on the architecture's form than on its inhabitants<br />

or functionality’ 13.<br />

Jacques Derrida, in ‘Memoirs <strong>of</strong> the Blind’ sets forward an argument<br />

about self-‐representation that contributes further to why the architect,<br />

in contrast to the artist, in his self-‐portrait, is seen as vain. The<br />

argument is essentially an attempt to prove that no self portrait can<br />

ever achieve its aim <strong>of</strong> being a true representation <strong>of</strong> the person<br />

responsible for it. Derrida argues that the draughtsman, or the painter<br />

is always concerned with drawing the blind object, in the architect<br />

designs buildings. Furthermore, he continues, the draughtsman is<br />

himself blind, ‘one draws only on the condition <strong>of</strong> not seeing’ 14, and thus<br />

every work becomes a self-‐portrait to some degree (exactly what was<br />

established at the earlier concerning the work <strong>of</strong> the architect).<br />

However, the crux <strong>of</strong> the argument lies in that ‘if the draughtsman is<br />

drawing the blind which is himself, he himself is drawing blindly, is blind<br />

to his drawing’ 15 and as such, ‘the desire for self-presentation is never<br />

met, it never meets up with itself, and that is why the simulacrum takes<br />

place.’ 16. In sum, the blind artist, who depicts the blind, and thus<br />

himself, cannot fully represent himself, since he is blind to what he is<br />

drawing. The self-‐portrait, then, can never be truly representational <strong>of</strong><br />

the creator behind it, and therefore the image and explanation <strong>of</strong> the<br />

person behind the work is individually formed in the minds <strong>of</strong> those<br />

who encounter it.<br />

This argument, coupled with the previously established notion that<br />

people care less for the provenance and personality <strong>of</strong> an architect, due<br />

to the fact that their creations have to satisfy a public function,<br />

highlights another explanation for why the architect is condemned with<br />

vanity for expressing his self-‐portrait within his work. If, as Derrida<br />

argues, through self expression and representation, the architect<br />

becomes a subjective, imagined personal entity in the mind <strong>of</strong> the<br />

viewers <strong>of</strong> his work and if the question <strong>of</strong> who the character behind the<br />

product is, is not necessarily <strong>of</strong> interest to those concerned with the day<br />

to day interaction with it, (as oppose to the case <strong>of</strong> the artist) the<br />

architect, and his personality becomes, entirely, his buildings.<br />

In the eyes <strong>of</strong> the public, so far as they are concerned, the architect then,<br />

is seen entirely as his material output. It seems, as a result, that<br />

materiality, and the greatness <strong>of</strong> their material product is the only thing<br />

with which the architect is concerned and through which he portrays<br />

himself. The fruit <strong>of</strong> the architect’s labor becomes his mask. He is<br />

known only through the guise <strong>of</strong> his buildings, leading to the incredible<br />

subversion, <strong>of</strong>ten again perceived as vanity, witnessed in the<br />

photograph <strong>of</strong> the Beaux-‐Arts Ball at the Hotel Astor in 1931, in which<br />

several <strong>of</strong> the mot famous architects in the world <strong>of</strong> the time dressed up<br />

as their own buildings. Patrick Bateman, (Figure 5) in American Psycho, is<br />

materially obsessed. The products he buys and his material goods are<br />

13 BBC News Online, 6 th December 2012<br />

14 Derrida, Jacques, ‘Memoirs <strong>of</strong> the Blind – The Self-‐Portrait and Other Ruins, The<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Chicago Press, 1993, p.49<br />

15 Duff, Mike John, Working Notes, Blogspot, December 11 th 2007<br />

16 Derrida, Jacques, ‘Memoirs <strong>of</strong> the Blind – The Self-‐Portrait and Other Ruins, The<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Chicago Press, 1993, p.121<br />

10

Figure 5' - Patrick Bateman, the mask <strong>of</strong> the material man, 2000<br />

11

what define him, and as such he to succumbs to this sweeping brand <strong>of</strong><br />

vanity.<br />

‘There is an idea <strong>of</strong> a Patrick Bateman; some kind <strong>of</strong> abstraction. But there is no real me:<br />

only an entity, something illusory.’ 17<br />

It appears a statement <strong>of</strong> great pride, and shallowness, to suggest that<br />

our buildings, our materials, are worthwhile replacements <strong>of</strong> our true<br />

personality. It alludes to the suggestion <strong>of</strong> greatness and bold<br />

individualism illustrated earlier that the architect is willing to attribute<br />

himself entirely to his material work.<br />

For the architect, then, his buildings become his mask, the primary<br />

means through which he finds a form <strong>of</strong> self-‐expression. For his self-‐<br />

portrait, he is denounced as vain, self-‐centered, and contemptible, for<br />

he must not only satisfy aesthetic desires, but also the pragmatic<br />

necessities <strong>of</strong> function. However, having initially agreed with the<br />

derogations <strong>of</strong> seemingly bold gestures <strong>of</strong> self-‐worth, such as those <strong>of</strong><br />

Phidias, and Adolf Loos, I am a convert. I believe that the architect is<br />

entirely right to include his individual ideals, himself, and to an extent<br />

his ego within his work, because the self-‐portrait <strong>of</strong> the architect is that<br />

<strong>of</strong> an entirely different sort. Such self-‐portraits and representations <strong>of</strong><br />

the self have historically existed in art for centuries, yet they are more<br />

difficult to find, less obvious, more intelligent than a mere physical<br />

depiction <strong>of</strong> oneself. The architects’ self-‐portrait, in my opinion, is one<br />

<strong>of</strong> emergence, through immersion.<br />

Agnes Varda is a key proprietor in this vein, with her film ‘The Gleaners<br />

and I’, in which she sets out to simply make a documentary about a<br />

subject in which she is very interested, namely, gleaning (scrounging,<br />

scavenging). However, the film ends up being, although not initially<br />

intended from the outset, a strong representation <strong>of</strong> Varda herself. She<br />

sees the work as ‘another kind <strong>of</strong> gleaning, which is artistic gleaning. You<br />

pick ideas, you pick images, you pick emotions from other people, and<br />

then you make it into a film’ 18. She films what inspires her, and in doing<br />

so the film becomes a reflection <strong>of</strong> her, the film maker. Her self-‐portrait<br />

emerges, through this total immersion, love <strong>of</strong> her work and<br />

inspiration. This, I feel, is the where the true defence from vanity in the<br />

architect’s self-‐portrait, lies. The way architects represent themselves<br />

stems from a total love <strong>of</strong> what they do. Works <strong>of</strong> architecture are not<br />

intended to be purely self-‐reflective, as monuments to their creator,<br />

from the outset. Rather, the personality they inherit is an emergent<br />

property <strong>of</strong> the real interest and inspiration the creator finds in the<br />

work that they do.<br />

To return again to Howard Roarke and his ideal individualism, he states<br />

that,<br />

‘to get things done, you must love the doing’ 19<br />

The architect doesn’t make such bold statements and proclamations<br />

about his work out <strong>of</strong> a longing to assert power over the swarming<br />

masses. I now feel that this is entirely misconstrued. The architect is not<br />

shallow for being concerned with the material world, this again is<br />

misconstrued. Oscar Wilde once said,<br />

17 American Psycho, Film, Mary Harron, Bret Easton-‐Ellis, 2000<br />

18 Anderson, M., and A. Varda. "The Modest Gesture <strong>of</strong> the Filmmaker -‐ an Interview with<br />

Agnes Varda." CINEASTE 26.4 (2001): 24-‐7. Print.<br />

19 Rand, Ayn, ‘The Fountainhead’, Film, King Vidor, 1949<br />

12

‘It is only shallow people who do not judge by appearances. The mystery <strong>of</strong> the world is<br />

the visible, not the invisible’ 20<br />

Maybe architects do sometimes fail in their work in the belief that they<br />

themselves are right, more right than anyone else. However we are<br />

wrong to cast the net <strong>of</strong> vanity over such judgments. The architect<br />

makes these decisions, grand, pubic and therefore open to great<br />

criticism, because he loves this doing, just as the artist paints for the<br />

love <strong>of</strong> his own form <strong>of</strong> doing. This, surely is not vanity! This self-‐<br />

representation within the architectural project arises from a total<br />

immersion within a subject which takes such hold <strong>of</strong> a man’s life and<br />

individual beliefs. In what position would we find ourselves without<br />

this form <strong>of</strong> the architect’s self-‐representation? The pr<strong>of</strong>ession would<br />

be in tatters, doomed to total architectural homogeneity and the refusal<br />

to produce something new, and individual. So condemn him not for<br />

vanity, and throw not Phidias in jail, for these are the men, who, without<br />

their belief and their individuality and their immersion within their<br />

subject to the point where they are willing to take a leap nobody else<br />

would dare, for without them, we are nowhere.<br />

20 Wilde, Oscar, in a letter, ref. Sontag, Susan, ‘Against Interpretation’, Vintage, 2001, p.1<br />

13

Bibliography<br />

Nietzsche, Friedrich, ‘Thus Spoke Zarathustra’, Penguin Classics, 2003<br />

Loos, Adolf, ‘Ornament and Crime: Selected Essays’, Ariadne Press, 1998<br />

Honour and Fleming, ‘A World History <strong>of</strong> Art’, Laurence King, 1982<br />

Janson, H.W, ‘History <strong>of</strong> Art’, Harry N. Abrams Inc., 1986<br />

Van de Wetering, Ernst, ‘Rembrandt by himself’, National Gallery, London, 1999<br />

Derrida, Jacques, ‘Memoirs <strong>of</strong> the Blind – The Self-‐Portrait and Other Ruins, The<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Chicago Press, 1993<br />

Sontag, Susan, ‘Against Interpretation’, Vintage, 2001<br />

La Cecla, Franco, ‘Against <strong>Architecture</strong>’, PM Press, 2012<br />

Easton-‐Ellis, Bret, ‘American Psycho’, Picador, 2011<br />

Rand, Ayn, ‘The Fountainhead’, Signet, New York, c1972<br />

Filmography<br />

‘The Fountainhead’, Film, King Vidor, 1949<br />

‘Sketches <strong>of</strong> Frank Gehry’, film, Sydney Pollack, Sony/WNET, 2000<br />

American Psycho, Film, Mary Harron, Bret Easton-‐Ellis, 2000<br />

‘The Gleaners and I’, Film, Agnes Varda, 2000<br />

Webography<br />

http://www.britannica.com<br />

http://oxforddictionaries.com<br />

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/<br />

http://userpages.umbc.edu<br />

http://perseus.mpiwg-‐berlin.mpg.de<br />

Images<br />

1 - The Beaux-Arts Ball at the Hotel Astor, New York, 23 January 1931<br />

2 - Detail from ' Wedding portrait', Jan Van Eyck, 1434<br />

3 - 'Saint luke as a Painter, Before Christ on the Cross', Francisco de Zurbaran, 1630-1639<br />

4 - 'Selbstbefriedigung', Egon Schiele, 1911<br />

5 - Patrick Bateman, the mask <strong>of</strong> the material man, 2000<br />

14