Frances Stark - Greengrassi

Frances Stark - Greengrassi

Frances Stark - Greengrassi

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>Frances</strong> <strong>Stark</strong><br />

My Best Thing<br />

Alvin Balkind Gallery<br />

February 3 to April 15, 2012<br />

<strong>Frances</strong> <strong>Stark</strong> was born in 1967, Newport<br />

Beach, California. She studied at San<br />

Francisco State University, San Francisco<br />

and Art Center College of Design, Pasadena,<br />

California. She now lives and works in Los<br />

Angeles. Recent solo exhibitions include<br />

the MIT List Visual Arts Center, Cambridge,<br />

Massachusetts and Centre for Contemporary<br />

Art, Glasgow (both 2010); Nottingham<br />

Contemporary (2009); Portikus, Frankfurt/<br />

Main and Wiener Secession, Vienna (both<br />

2008); FRAC – Bourgogne, Dijon (2007);<br />

Artspace, San Antonio (2006). Recent group<br />

exhibitions include Restless Empathy, Aspen<br />

Art Museum, The Page, Kimmerich, New York;<br />

For the blind man in the dark room looking<br />

for the black cat that isn’t there, Museum of<br />

Contemporary Art, Detroit (all 2010); Picturing<br />

the Studio, School of the Art Institute of<br />

Chicago; Poor. Old. Tired. Horse., Institute<br />

of Contemporary Arts, London; The Space<br />

of Words, MUDAM: Musée d’Art Moderne<br />

Grand-Duc Jean, Luxembourg (2009);<br />

Pretty Ugly, Gavin Brown’s Enterprise, New<br />

York; Word Event, Kunsthalle Basel and the<br />

Whitney Biennial, Whitney Museum, New York<br />

(2008). My Best Thing was presented at the<br />

54 th Venice Biennale and has subsequently<br />

been screened at Walter Phillips Gallery,<br />

The Banff Centre, Alberta, The Institute of<br />

Contemporary Arts, London and Marc Foxx<br />

Gallery, Los Angeles.<br />

To accompany the exhibition a publication<br />

with a major new text by Mark Godfrey,<br />

Curator, Tate Modern, London, has been<br />

produced by the Contemporary Art Gallery in<br />

collaboration with the Walter Phillips Gallery,<br />

The Banff Centre, dedicated exclusively to My<br />

Best Thing. Please see reception for details.<br />

The Contemporary Art Gallery presents My Best Thing (2011),<br />

<strong>Frances</strong> <strong>Stark</strong>’s first feature-length animation. Initially presented<br />

in ILLUMInations at the 54 th Venice Biennale, this recent work<br />

has rapidly gained critical attention. Using transcripts of an<br />

on-line relationship between <strong>Stark</strong> and two random strangers,<br />

the video unfolds to build an intimate portrait of the artist and<br />

her creative process. It continues <strong>Stark</strong>’s ongoing concerns with<br />

expectation and gender infused with notions of doubt, anxiety<br />

and musings on the general state of things. While arguably<br />

best known for her works on paper, where such issues are seen<br />

through the lens of writing, drawing and collage, her videos and<br />

performance pieces likewise comprise a forceful component in<br />

her overall artistic proposition.<br />

In My Best Thing two naked online avatars are pictured, a<br />

man and a woman, playmobil-like figures wearing discrete fig<br />

leaves for modesty. The video traces the development of their<br />

relationship beginning as a series of discussions revolving around<br />

standard chat-room flirtatiousness. These encounters then give<br />

way to talk about film, art and subjectivity, touching on ideas<br />

surrounding history, politics and the very act of art-making itself.<br />

As the work progresses between two people initially unfamiliar<br />

to each other, the sexually oriented chat evolves into talk of<br />

them becoming potential collaborators. However, at this point of<br />

heightened acquaintance their relationship comes to an abrupt<br />

halt and conversation with a second person ensues. The artist’s<br />

exchange with each of her on-line counterparts is poignant<br />

and oen comic, enhanced by the animation itself where <strong>Stark</strong><br />

used Xtranormal, freely available 3D movie-making soware, to<br />

render herself and her opposite number as cartoons, speaking in<br />

computer-generated accents transferred from actual dialogue.<br />

This is a compelling work that humorously and touchingly<br />

reflects on our changing world; a place where relationships<br />

mediated by technology challenge the usual understanding<br />

of how we interact with each other and allows new forms<br />

of behaviour to emerge. <strong>Stark</strong> continues to remind us of<br />

the complexity inherent in everyday encounters. Ideas of<br />

performance and role-playing, the anonymity versus intimacy<br />

implicit within the artist’s animation, are examined and brought<br />

into the wider philosophical discourse of subjectivity where<br />

strangers can so easily transform into confidantes.<br />

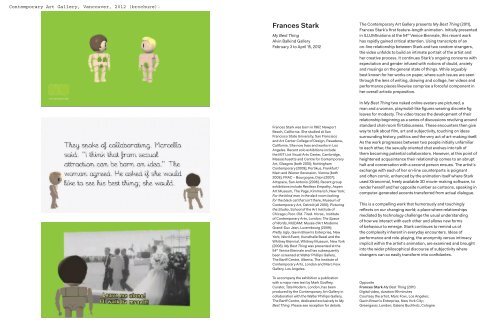

Opposite<br />

<strong>Frances</strong> <strong>Stark</strong> My Best Thing (2011)<br />

Digital video, duration 99 minutes<br />

Courtesy the artist, Marc Foxx, Los Angeles;<br />

Gavin Brown’s Enterprise, New York City;<br />

Greengassi, London; Galerie Buchholz, Cologne

Yablonsky, Linda, <strong>Frances</strong> <strong>Stark</strong>’s Best Thing, The New York Times Style Magazine,<br />

NYC, October 26, 2011.<br />

Artifacts | <strong>Frances</strong> <strong>Stark</strong>’s Best Thing<br />

Nadya Wasylko, courtesy of the artistThe artist <strong>Frances</strong> <strong>Stark</strong>, at right, with Skerrit Bwoy, from “Put a Song in<br />

Your Thing,” a work in progress to be performed at the Abrons Art Center on Nov. 4.<br />

Some people like to talk during sex. Others get their kicks by talking about it. And<br />

then there are those who would rather just watch.<br />

The Los Angeles artist <strong>Frances</strong> <strong>Stark</strong> has something for everyone in “My Best<br />

Thing,” a compulsively watchable, feature-length digital animation now playing<br />

at MoMA P.S. 1that goes well beyond the whisper of sweet nothings. Clad either<br />

in fig leaves or briefs, the wide-eyed, stock C.G.I. dolls on screen re-enact the<br />

flirtations that <strong>Stark</strong>, 44, carried on with two 20-something Italian men whom<br />

she met at different times last year while taking random strolls through a video<br />

sex chat site.<br />

Though they often talk dirty, the characters’ spoken and texted exchanges<br />

constantly digress into other channels of their very different lives, taking the film<br />

deep into the heart of intimate human relationships. Nietzsche, Fellini, Glenn

Gould, Picasso, political protest and the suicides of writers like David Foster<br />

Wallace all become part of each pair’s ardent, LOL–infused “post-coital” banter,<br />

as do their families, careers and <strong>Stark</strong>’s responsibilities as both the mother of an<br />

8-year-old boy and a professor at the University of Southern California.<br />

“Show me more,” says Marcello, her first suitor, once the two have repaired to the<br />

privacy of Skype. “Wow,” he says, though in his accent it comes out as, “Whoa.”<br />

“I’m old,” she replies. “So you have to be forgiving.”<br />

“Heh-heh,” he says. “I like mature women.”<br />

And so it goes, as the minimal small talk and virtual fondling escalate over 10<br />

episodes into a poignant, funny and revealing narrative of desire and self-doubt.<br />

Though the computer-generated voices lack emotion, the figures’ flashing eyes,<br />

pregnant pauses and twisting dance movements convey a remarkable depth of<br />

feeling.<br />

Courtesy of the artist and Gavin Brown Enterprise<br />

A scene from the <strong>Frances</strong> <strong>Stark</strong> video “My Best Thing.”<br />

<strong>Stark</strong> is a writer as well as a visual artist, and much of her work to date involves a<br />

struggle for words as well as meaning. “Why is it I always want to explain to you<br />

everything?” <strong>Stark</strong> asks Marcello, occasionally resorting to Google’s translator to<br />

make sure she understands him, while he apologizes for his awkward English. But<br />

the two speak volumes through their bodies.<br />

“I got fascinated by feeling so intensely for people I didn’t know,” <strong>Stark</strong> said in a<br />

Skype conversation the other day. “I was never into Internet sex, but because it’s<br />

a form of seduction that took place through typing and interacting visually, I got<br />

hooked.”

So do many viewers of “My Best Thing” — to my mind, <strong>Stark</strong>’s best thing yet. In<br />

an early episode, she tells her young suitor that she is in “a heavy dancehall<br />

phase,” and shows him a music video of the high-speed, violently sexual<br />

Jamaican dance style called daggering. Her obsession with it led to “Put a Song in<br />

Your Thing,” a live show that <strong>Stark</strong> will stage next week in New York as a<br />

commission from the Performa 11 biennial of performance art.<br />

Skerrit Bwoy, a “hype man” and D.J. for the dancehall band Major Lazer<br />

distinguished by his yellow mohawk, will join her onstage with a “BigBox” sound<br />

system rigged by the British artist Mark Leckey, who won the Turner Prize in<br />

2008. Mostly, though, the show will take place on a screen, where <strong>Stark</strong>’s Skype<br />

chats will again appear, along with projections from her current show at the Mills<br />

College Art Museum. This time, the performers will read the texts aloud as lyrics<br />

for the dozen songs in the show, which <strong>Stark</strong> says brings it close to a silent movie<br />

experience. “It’s a way of throwing my voice,” she said. “I’m there, but not really.”<br />

One tune is a piano piece composed by her second Italian discovery in “My Best<br />

Thing.” <strong>Stark</strong> made the video as her contribution to the current Venice Biennale,<br />

a decision played out in the course of the piece, when she asks Marcello, a<br />

filmmaker, to collaborate with her on the project. “I was willing to do whatever it<br />

took to get him here,” <strong>Stark</strong> said. “We had an interesting story, and I wanted to<br />

tell it but didn’t know how.”<br />

At that point, she discovered Xtranormal.com, a Web site supplying animators<br />

with characters, voices and music, and went to work, despite Marcello’s<br />

subsequent disappearance after he was badly beaten in a Roman political protest.<br />

Her biggest problem then was what to tell her boyfriend, Stuart Bailey, who is one<br />

half of Dexter Sinister, a design and publishing collaborative. “I told him that<br />

Chat Roulette had become part of my thinking,” she said. “But I don’t think it’s<br />

his favorite thing in the world.”<br />

<strong>Frances</strong> <strong>Stark</strong>’s “My Best Thing” is on view through January 2012 at MoMA P.S.<br />

1, 22-25 Jackson Avenue, Long Island City. She will perform “Put a Song in Your<br />

Thing” on Nov. 4 at the Abrons Art Center, 466 Grand Street. “The Whole of All<br />

the Parts as Well as the Parts of All the Parts” continues through Dec. 11 at Mills<br />

College Art Museum, 5000 MacArthur Boulevard, Oakland, Calif.

Princenthal, Nancy, <strong>Frances</strong> <strong>Stark</strong>, Art in America, NYC, January 4, 2011.<br />

FRANCES STARK<br />

by Nancy Princenthal<br />

The Internet Age is widely unde the apogee of image culture, but the medium in which we<br />

swim, buoyed by waves of chat, posts and tweets, seems increasingly to be the written word.<br />

Or so it appears in the company of <strong>Frances</strong> <strong>Stark</strong>.<br />

<strong>Frances</strong> <strong>Stark</strong>: Portrait of the Artist as Full-on Bird, 2004, collage on casein on canvas board, 20 by 24 inches.<br />

Courtesy Galerie Daniel Buchholz, Cologne/Berlin.<br />

Like more than a few artists of her generation, <strong>Stark</strong> (born 1967 in Newport Beach) often<br />

incorporates writing in her work, which was surveyed recently at the MIT List Visual Arts<br />

Center in Cambridge. She has also published her texts independently in various magazines,<br />

catalogues and freestanding books, and has penned the odd exhibition review. A cross<br />

between fluidly interdisciplinary commentary and wry interior monologue, <strong>Stark</strong>ʼs prose<br />

showed up at the List Center not only as content in her drawings and collages but also in the<br />

worksʼ titles; in wall labels, which were generally restricted to the usual identifying information<br />

but sometimes digressed rather freely; and, most prominently, in the exhibition catalogue,<br />

which is not a conventional document (there are no illustrations) but an anthology of her<br />

essays, graced very occasionally with exceedingly terse marginal notations by the surveyʼs<br />

curator, João Ribas. <strong>Stark</strong>ʼs relish for marginalia is confirmed by the title of both book and<br />

exhibition, This could become a gimick [sic] or an honest articulation of the workings of the<br />

mind, which derives from a comment written in the margin of a used copy of Alain Robbe-<br />

Grilletʼs 1955 novel The Voyeur. <strong>Stark</strong> transcribed the annotated page of this lucky find into a<br />

drawing in 1995.<br />

As this titular work suggests, there was a bounty of odd references on offer in the exhibition<br />

and its accompanying book. But above all, we got to know <strong>Stark</strong>—and generally felt fortunate<br />

to be in her company. The show opened with several biographical notes, among<br />

them Untitled (Self-portrait/Autobiography), 1992, a red carbon copy of her college transcripts<br />

(good grades predominate; there is one less successful semester). There were also a couple<br />

of nearly blank pieces of paper in the first room, variously enhanced (hand-ruled lines, a one-

line note from a friend), suggesting the outset of any routinely terrifying effort at writing, or artmaking.<br />

Bookishness was instated as a theme with a handful of found and altered volumes.<br />

The transcribed page of Robbe-Grillet shared a wall with altered copies of Henry<br />

Millerʼs Sexus (1992) andTropic of Cancer (1993), and with illegible drawings of two pages<br />

from John Deweyʼs Art as Experience(Having an Experience, 1995).<br />

Among other signature motifs introduced early on are birds; Portrait of the Artist as a Full-On<br />

Bird (2004) includes a collaged photo of a cockatoo. <strong>Stark</strong> explained to me in an interview<br />

that she favors birds because, like marginalia, they perch lightly on the edges of things,<br />

serving as points of entry—or, more to the point, re-entry. (In The Old In and Out, 2002, a<br />

collage/drawing of two birds mating, this function serves a simple joke.) Peacocks, which<br />

variously flaunt and modestly fold their feathers in several works, need no explanation as<br />

metaphor.<br />

Many artists depict birds, none of them evoked by <strong>Stark</strong> with any specificity. But often,<br />

interartist connections are freely acknowledged. One label explained that a red-painted<br />

wooden dining chair of vaguely Asian design traces its history to what is said to be the oldest<br />

Chinese restaurant in Los Angeles, the city where <strong>Stark</strong> lives; in recent decades the<br />

restaurant became an art bar, and then Jorge Pardoʼs studio. It was Pardo (whom <strong>Stark</strong> has<br />

known for 20 years) who provided her with the chair, which he dismembered; Evan Holloway<br />

helped her see that sheʼd need wooden splints to put it back together, duct tape not being up<br />

to the job. Its feet propped on plaster blocks, the chair (2001) is part of a series called “The<br />

Unspeakable Compromise of the Portable Work of Art,” a title borrowed from an essay by<br />

Daniel Buren published inOctober in 1971. (This last bit of information comes not from the<br />

label, but from <strong>Stark</strong>ʼs 1999 book of essays,The Architect & The Housewife.) Other<br />

friendships attested to include Olafur Elíassonʼs, in the form of a note he sent <strong>Stark</strong><br />

proclaiming that a blank piece of paper is not enough (It is not enouff, 1998).<br />

<strong>Stark</strong> cautions against reading all this collegiality as a testament to the special community<br />

spirit of the L.A. art scene. While she confirms a sense of “invisible connectedness,” and<br />

there is an undeniable tendency toward promiscuity in the matter of social as well as textual<br />

and visual allusions in her work, she is also at pains to demonstrate how much of her time is<br />

taken up with perfectly chaste domesticity. <strong>Stark</strong>ʼs home life can be glimpsed in Cat<br />

Videos (1999-2002), which features feline antics in alternation with those of two little boys—<br />

her son and a friend of his. The kids watch David Bowie on a laptop and groove, four-yearoldishly,<br />

to the music. <strong>Stark</strong> says she didnʼt intend to make an artwork when she turned on<br />

the camera, but was delighted to find it had recorded what she describes as a “perfect essay<br />

on cultural reproduction”—i.e., small boys acting out the pop-cultural myth of Bowie as Ziggy<br />

Stardust, touching down to greet the planet.<br />

The sense of hominess in these videos is expanded in several large collages featuring<br />

cabinets, mirrors and flowers. Foyer Furnishing (2006) is a large (more than 7-foot-high)<br />

drawing/collage that features all three: the mirror (made of Mylar) reflects potted flowers<br />

drawn in gouache; a collaged bag slumped by the cabinetʼs side holds actual printed matter<br />

(student papers, bills). In To a Selected Theme (Fit to Print), 2007, a long-stemmed<br />

chrysanthemum, in a vase on a table, leans its head toward the cover of a David Hockney<br />

catalogue on which the artist is seen lounging with trademark insouciance.<br />

Most of the work that was shown is on paper, occasionally mounted on canvas and/or panel.<br />

Scale varies widely, and while a few compositions are offhand, the majority are executed with<br />

considerable care; text is sometimes cut out and set into its support letter by letter, and the<br />

drawing is deft throughout. But self-doubt always threatens. Oh god, Iʼm so<br />

embarrassed (2007) makes use of a poster for a 1994 Sean Landers exhibition on which that<br />

irremediably self-demeaning artist wrote, “I regret to inform you that I could not come up with<br />

an idea for the invitation card. . . . Something is terribly wrong with me. . . . Oh god Iʼm so<br />

embarrassed.” <strong>Stark</strong> helps demonstrate the perfect ordinariness of his mortification by pairing

the poster with a mundane accessory: an umbrella parked in a stand (though that could allow<br />

Surrealist or sexual readings as well).<br />

Speaking for herself, <strong>Stark</strong> asks, in the title of a work of 2008, Why should you not be able to<br />

assemble yourself and write? The question also appears on a piece of paper held in the<br />

subjectʼs lap, which we view from above; in this drawing, the seated figureʼs feet drift upward<br />

and her head anchors the drawingʼs bottom. In I must explain, specify, rationalize, classify,<br />

etc. (2007), the subject—again, it is presumably the artist—stands on a chair on casters, not<br />

the steadiest of supports. Her back to us, she substantially obscures a long text, holding a<br />

builderʼs level under the word “nose” in the passage, “I must explain, enabling the reader to<br />

find the workʼs head, nose, fingers, legs, . . .” There will also be things that I donʼt like (2007)<br />

finds the subject standing on the same chair, struggling to hang a garland of big Mylar<br />

sequins; the titular declaration, printed in yellow vinyl letters, blares beside her.<br />

The text in I must explain (again), 2009, covers a big sheet of paper that extends to the floor;<br />

it is held by the outstretched hands of a silhouetted woman drawn on the ground sheet—a<br />

figure nearly concealed by her own lengthy declamation. This drawing shared the showʼs final<br />

room with works that are, in one way or another, nearly all time-based. The four examples<br />

shown from the series “Wisdom, Stupidity, Ugliness” (2008) each features the actual moving<br />

hands of a working clock, along with the image of a book and the profile of a progressively<br />

dejected woman, who proceeds from upright but leaning to slumped and then bent double: a<br />

day in the life. Toward a score for “Load every rift with ore” (2010) is a very large (nearly 80by-90-inch)<br />

collage that centers on an image of a music stand and features several printed<br />

fragments that could serve, in a pinch, as scores. This work faced a freestanding black dress,<br />

its skirt adorned with a massive dial modeled on an old-fashioned rotary phone. <strong>Stark</strong> wore<br />

this costume in a 2009 performance, about which no information was given. As shown, it is<br />

among the least accessible works in a survey that otherwise mostly manages to avoid the<br />

annoying trait common in much strenuously casual, neo-conceptual work, of talking over the<br />

audienceʼs head.<br />

Another time-based medium in <strong>Stark</strong>ʼs repertory is PowerPoint, which she uses to wickedly<br />

funny effect in the nearly half-hour-long presentation Structures that Fit My Opening (2006).<br />

Shown on a laptop, it offers, as in some loopy version of off-site higher ed, a rambling<br />

monologue, given in title frames, and a range of imagery dominated by photographs of the<br />

artistʼs home. The intermittent soundtrack features a typewriter clacking in use, a ticking<br />

clock, a ringing phone and cymbals striking to note the occasional punch line. One droll<br />

anecdote concerns an exchange of letters between <strong>Stark</strong> and an editor requesting a text; the<br />

artist declines, but her (written) refusal is accepted as a contribution, for which she is paid<br />

before she can explain the misunderstanding.<br />

In <strong>Stark</strong>ʼs boundary-less working life, such incidents seem to occur with some regularity. Mild<br />

confusion reigns, untidiness is accepted, things spill. Efforts are made to straighten out the<br />

mess, and duly documented: witness, perhaps, an otherwise hard to explain image of a<br />

vacuum cleaner, Hoover in a Corner (2006). But it remains a struggle, really, to keep it all<br />

straight—to maintain distinct professional and personal identities; to project a voice<br />

distinguished by its candor while protecting the speakerʼs privacy and integrity; and to be sure<br />

that what is said matches what is meant.<br />

The buzzing intertextuality of <strong>Stark</strong>ʼs work is more closely related to the densely referential<br />

installations of such artists as Rachel Harrison and Carol Bove than to drawings or paintings<br />

by other wordsmiths like Graham Gilmore and Raymond Pettibon. <strong>Stark</strong>ʼs kinship with rogue<br />

theorists/historians becomes most apparent in the writings collected in This could become a<br />

gimick [sic]. Ribasʼs exceedingly spare and recondite interventions, none more than a few<br />

words long, make for an amusing contrast with <strong>Stark</strong>ʼs voluble and often diffident prose. In<br />

one essay she acknowledges being flummoxed when people ask me ʻWhat is your work like?ʼ<br />

upon my foolishly having revealed to them that Iʼm an artist. I feel like my non-answer is often

misinterpreted as ʻIʼm too deep to tell you,ʼ but usually Iʼm just thinking a description of what I<br />

do is going to make what I do sound really un-worth doing.<br />

In the margin, Ribas writes, “A literature of refusal” and names the writers Robert Musil and<br />

Robert Walser; below, he adds, “Malevich and laziness.” But then <strong>Stark</strong> herself is just as likely<br />

to quote Musil (a touchstone), Stanley Cavell, Harold Bloom, Avital Ronell, Paul de Man and<br />

dozens of highbrow others.<br />

Strikingly, the bookʼs last essay ends with a little meditation about the shaky hold our minds<br />

have on the information delivered by our senses. <strong>Stark</strong>ʼs friend Sharon Lockhart, who made a<br />

well-known series of photographic portraits of young adolescents at Pine Flat, Calif., mistook<br />

a suicidal teen who appears in a film by Larry Clark for one of her subjects. Lockhart “had to<br />

rewatch the scene many times before she realized, with some sense of relief I suppose, she<br />

was mistaken.” <strong>Stark</strong> concludes, “It is this double take, this impossibly unfavorable crossover<br />

between two worlds seemingly so far from each other that moved me to write what you just<br />

read the way that I did.” It is a conclusion of considerable ambiguity.<br />

Robbe-Grilletʼs The Voyeur (whence the marginal note from which the book and exhibition<br />

took its title) is, typically for the author, a shifty novel. Its protagonist is short on affect and<br />

lacks any grasp of temporal reality, but he has the visual acuity of a raptor. His experiences<br />

are described in hypnotic detail, an account that is repetitious, inconsistent and altogether<br />

untrustworthy. <strong>Stark</strong>, by contrast, invites our faith in her emotional and intellectual honesty.<br />

But she also lets us know that sheʼs not a completely reliable narrator either. And if, as<br />

readers of her prose—or viewers of her art—we are tempted to add our second guesses and<br />

interpretive digressions to Ribasʼs and her own, we find ourselves in a peculiarly unstable<br />

position. Itʼs a very odd place from which to write criticism—which may be part of <strong>Stark</strong>ʼs<br />

exceptionally canny strategy.<br />

“<strong>Frances</strong> <strong>Stark</strong>: This could become a gimick [sic] or an honest articulation of the workings of<br />

the mind” was on view at the MIT List Visual Arts Center, Cambridge, Mass., Oct. 22, 2010-<br />

Jan. 2, 2011.<br />

NANCY PRINCENTHAL is a writer who lives in New York.

Martin Herbert, David Hockney & <strong>Frances</strong> <strong>Stark</strong>, Frieze, #128,<br />

London, Jan / Feb 2010.<br />

David Hockney & <strong>Frances</strong> <strong>Stark</strong> -‐ Nottingham Contemporary, Nottingham, UK<br />

David Hockney, A Lawn Sprinker (1967)<br />

You’re opening a kunsthalle in the UK’s seventh-‐largest city, two hours from London.<br />

You have several publics to please: your institution needs to speak to the locals, but<br />

without being provincial. So you imprint the façade of your striking, green and gold,<br />

Caruso St John-‐designed building in the city’s Lace Market area with a filigree pattern

sourced from lace found in a 19th-‐century time-‐capsule dug up on the site – but you also<br />

get Matthew Brannon in to decorate the café. And then, having remembered not to fill<br />

the place with Scandinavian abstraction, you launch with a crafty, diversely intersecting<br />

double-‐header. A youngish, art-‐world-‐approved (but not over-‐exposed) Californian who<br />

specializes in expressing assured anxiety and febrile joys through spacious, funky<br />

collage; and the UK’s most beloved living artist, seen here – in a show focusing tightly on<br />

1960–8, when he lived variously in England and California – at his edgiest and, arguably,<br />

most fulsomely inventive.<br />

Assembled by Nottingham Contemporary director Alex Farquharson and curator Jim<br />

Waters, the David Hockney show (‘A Marriage of Styles’) plays in reverse: beginning<br />

with the bright, familiar, sun-‐dazzled expat in California, it backtracks to trace the<br />

Yorkshireman’s scuffling route towards this easeful world of male bodies in Beverly<br />

Hills showers and blue, blue pools. In 1960, while a student at London’s Royal College of<br />

Art, Hockney made his first painting about homosexuality: the small, mustard-‐toned<br />

semi-‐abstraction Queer, its primary elements a black star and the barely legible titular<br />

epithet. It would be seven more years before gay relations were legal in the UK, and six<br />

before Hockney was lithely sketching men sharing beds for his series of etchings<br />

‘Illustrations for Fourteen Poems from C.P. Cavafy’ (1966). In this installation, those<br />

years reflect a steady emboldening in both subject matter and form.<br />

In the dual figure composition We Two Boys Together Clinging (1961), Hockney adapts<br />

the physiognomic deformations and sensuously feral paintwork of 1950s De Kooning<br />

into cartoonish tenderness, and stitches the composition together with the title phrase<br />

(in a child’s handwriting), a wry homoerotic repurposing of a Walt Whitman line. By<br />

1962 Hockney had spent time in America, as documented in the comic cautionary tale of<br />

his Hogarth-‐updating etchings suite, ‘A Rake’s Progress’ (1961–3). The First Marriage (A<br />

Marriage of Styles I) (1962), with its reshaped image of a friend beside an Egyptian<br />

statue, roomy composition and attendant palm tree, anticipates the warm-‐climate ease<br />

and stylistic intransigence of his later Los Angeles paintings. It’s a little sad to say<br />

farewell to the giddy mélanges of Hockney’s early style, and his exuberant obsessions<br />

with the young Cliff Richard and beefcake models. As he evolves into the deceptively<br />

serene architect of A Bigger Splash (1967) and its beautiful, lesser-‐known cousin A<br />

Lawn Sprinkler (1967) – LA gardens in perpetual mid-‐afternoon, subtended by a<br />

constant need to cool hot bodies, and hot earth – it’s underlined that Hockney is,<br />

essentially, a tenacious problem-‐solver. How to paint the dynamics of water and to talk<br />

about homosexuality in art are problems of different magnitudes, of course. What<br />

matters is that Hockney, boldly and satisfyingly, solves them.<br />

‘But what’ – to quote the full title of the exhibition that complements Hockney’s – ‘of<br />

<strong>Frances</strong> <strong>Stark</strong>, standing by itself, a naked name, bare as a ghost to whom one would like<br />

to lend a sheet?’ Looking at A Bigger Splash, one can imagine one of Joan Didion’s<br />

frazzled rich housewives standing motionless inside the bungalow with a fistful of<br />

tranquilizers; and <strong>Stark</strong>’s persona in her art sometimes suggests an equivalent to the<br />

self-‐image Didion presents in her journalism and fictional manquées: the sort of highly-‐<br />

strung, hyper-‐aware woman who used to get called ‘neurasthenic’. Underneath, though,<br />

both writer and artist are likely tough as old boots.<br />

Here, in a Farquharson-‐helmed array that underlines correspondences between <strong>Stark</strong><br />

and Hockney (beyond the latter featuring on a private view invitation in <strong>Stark</strong>’s To a<br />

Selected Theme (Fit to Print), 2007) – LA, self-‐exposure, theatricality, the invention or<br />

leveraging of an artistic persona, reverence for literature – we get a meld of recap and<br />

recent work. From the outset, <strong>Stark</strong> has twisted the Modernist permission to flaunt<br />

subjectivity, exposing thought’s fraying edges, its quicksilver succours. Momentarily

Lifted (2001) features the repeated handwritten phrase ‘momentarily lifted out of a<br />

tangle of rational intentions’, and it’s these paradoxical transcendences that <strong>Stark</strong> seems<br />

to chase and celebrate, finding them most obviously in literature: And brrrptzzap* the<br />

subject (2005) features a peacock whose tail is made up of pages of repeated letters and,<br />

it appears, pages from Robert Musil’s The Man Without Qualities (1930–42). In the<br />

painting/collage A Woman and a Peacock (2008), a graphical <strong>Stark</strong> doppelgänger<br />

encounters another specimen on a ledge or precipice: the bodies of both artist and bird<br />

are made up of collaged scraps of exhibition flyers and art works. Peacocks are a double-‐<br />

edged <strong>Stark</strong> motif, speaking of self-‐display and the sin of pride; of what it means to<br />

parade one’s mental workings as art.<br />

Even when it features no text, <strong>Stark</strong>’s art is partly one of offhandedly elegant and airy<br />

compositional instinct, but mostly one of deftly judged voice. It risks, however,<br />

becoming all intonation, all twitchy character. Seemingly she recognizes this: Stupidity<br />

(Pink) (2009), a painted silhouette of a hand appearing to hold a clutch of real fabrics<br />

and obscure papers on a pink background, and The Inchoate Incarnate (2009), a trio of<br />

black costumes in the shape of giant, old-‐fashioned dial telephones, open onto<br />

ambiguous emotional territory. One of the phone-‐dresses is pointedly subtitled<br />

‘Summon Me and I’ll Probably Come’. The key word, sustaining <strong>Stark</strong>’s delicate balance<br />

of light-‐headedness and grit, is ‘probably’.

Called upon (Same thing over and over), 2007.<br />

Courtesy: the artist. Photo: Marcus Leith<br />

Mousse 26 ~ <strong>Frances</strong> <strong>Stark</strong><br />

LOS ANGELES<br />

The Letter Writer, <strong>Frances</strong> <strong>Stark</strong><br />

by Andrew berArdini<br />

What is a love letter? The delicious agony of laboriously searching for just the right words,<br />

using the subtlest precision, though language will never be able to express the scent or the<br />

gestures of a loved one. To Andrew Berardini, the work of <strong>Frances</strong> <strong>Stark</strong> is an enormous,<br />

beautiful love poem in three dimensions, and she is a writer who writes in space…<br />

124

writers Mentioned in the <strong>Frances</strong> <strong>Stark</strong>’s Collected Writings: 1993-2003<br />

Oscar Wilde<br />

Friedrich Nietzsche<br />

Robert Musil<br />

P.D. Ouspenskij<br />

G.I. Gurdjieff<br />

Virginia Woolf<br />

E.H. Gombrich<br />

Gaston Bachelard<br />

Emily Dickinson<br />

Howard Singerman<br />

John Keats (non IL John<br />

Keats)<br />

Dorothy Parker<br />

Pierre Bourdieu<br />

Rudolf Steiner<br />

(alcuni sono ufficialmente artisti, altri sono storici, critici, seguaci della new<br />

Age; per i nostri scopi sono tutti scrittori)<br />

Other writers She Mentioned to Me as being important to Her not Listed<br />

Above:<br />

Witold Gombrowicz<br />

Ingeborg Bachmann<br />

Jonathan Pylypchuk<br />

Lane Relyea<br />

J.D. Salinger<br />

Gustave Flaubert<br />

David Foster Wallace<br />

Curtis White<br />

Ludwig Wittgenstein<br />

Jürgen Habermas<br />

Jimmie Durham<br />

Raymond Pettibon<br />

Novalis<br />

Joan Didion<br />

Goethe<br />

Thomas Bernhard<br />

Henry Miller<br />

...the clarity we are aiming at is indeed complete clarity. but this simply means<br />

that the philosophical problems should completely disappear.<br />

Ludwig wittgenstein, Philosophical Investigations<br />

in place of hermeneutics, we need an erotics of art.<br />

Susan Sontag, Against Interpretation<br />

A Single Paragraph on the Work of <strong>Frances</strong> <strong>Stark</strong> Before We Start Talking About<br />

Other Things:<br />

Los Angeles-based artist <strong>Frances</strong> <strong>Stark</strong> marks in her work the complex and<br />

beautiful struggle of how to clearly express the exact dimensions of thought<br />

and emotion. realized primarily through texts and fragile line drawings (as<br />

well as performance, collage, and paintings). <strong>Stark</strong>’s intensely personal practice<br />

reveals an artist engaging with literature, philosophy, and art history and how<br />

these effect the process of making art and the practice of everyday life. The<br />

effect of seeing an exhibition by her is similar to reading a novel of ideas all at<br />

once. To <strong>Stark</strong>, a thousand words is worth a picture.<br />

Chorus member in special position, 2008.<br />

Courtesy: Galerie Daniel Buchholz, Cologne/Berlin.<br />

Los Angeles ~ <strong>Frances</strong> <strong>Stark</strong><br />

125<br />

Chorus girl folding self in half, 2008.<br />

Courtesy: Galerie Daniel Buchholz, Cologne/Berlin.<br />

§ § §<br />

All writing to be read by someone else is a kind of a letter. One person writing<br />

to another. From me to you.<br />

This essay that i’m writing and you’re reading, and most writing found in magazines,<br />

is usually of the more impersonal variety. re: Subject. dear Sirs. To<br />

whom it may concern. Some writing published in the world are actual letters,<br />

from one single person to another. The epistolary novel. Love poetry.<br />

Though i’m sure some poets sit down and conjure an ideal beauty, as (to me,<br />

boring and sort of weird) exercise in formal strategy of love, but love (except<br />

for the naive) isn’t an ideal, it’s a specific. we love the grace of our lover’s long<br />

hands as they fold in weave in a conversation. we love the way they stand on<br />

their toes, naked body leaning forward, arched as the arms stretch up to close<br />

a window. we love their smell, wholly unique, and always difficult to articulate<br />

in words, but worth trying: the mix of cloves and motor oil, or like if a ship carrying<br />

cinnamon sank off the coast of a Caribbean sugar plantation just as they<br />

began to burn the cane, or freshly mown grass and old books. i could go on.<br />

we know our lover’s smell as only a lover can, even if it’s impossible to describe<br />

it accurately. it’s really specific though and us, writers of love letters, minor<br />

poets all, try and fail to put it into words. The poems get printed and reprinted,<br />

and sometimes centuries later we learn what a horny englishman quill penned<br />

to his desired woman in english 201a in an anthology with pages as thin as tissue<br />

paper. Perhaps we imagine ourselves the lover, memorizing lines to recite<br />

to the Literature major we’re trying to seduce sitting next to us in class – her<br />

blouse open showing the smooth, dark skin of her chest, his sensual lips pursed<br />

in thought. Or we image ourselves the object of affection, the surge of being<br />

desired, the look of lust. A little displaced, but poetry is meaningful when we<br />

make it meaningful for each of us, individually.<br />

i’m going to quote a bit of writing from <strong>Frances</strong> <strong>Stark</strong>. i hate performing these<br />

kinds of minute vivisections on language, but i think if i take it apart i can show<br />

you something perhaps beautiful, i promise, the words will return unharmed<br />

from whence they came.<br />

“One hundred years ago, my favorite artist, author Rubert Musil, wrote this in a<br />

letter friend: ‘Art’ for me is only a means of reaching a higher level of ‘self.’”<br />

“One hundred years ago”<br />

A simple time stamp but it’s exactitude implies a parallel, Musil then, <strong>Stark</strong><br />

now.<br />

“my favorite artist, author Robert Musil”<br />

robert Musil (november 6, 1880 – April 15, 1942), an Austrian writer who’s<br />

most famous book, The Man Without Qualities, is a hyperobsessive detailing of<br />

the Viennese ruling class right before the Austro-Hungarian empire collapsed,<br />

widely considered one of the great novels of the twentieth century. To see a<br />

writer described as a favorite artist is telling, though we’ll get to that more<br />

later.

I must explain,<br />

specify, rationalize,<br />

classify, etc.,<br />

2007. Courtesy: Thea<br />

Westreich and Ethan<br />

Wagner, New York.<br />

Toward a score for<br />

“Load every rift with<br />

ore”, 2010. Courtesy:<br />

the artist and Marc<br />

Foxx Gallery, Los<br />

Angeles.<br />

Mousse 26 ~ <strong>Frances</strong> <strong>Stark</strong><br />

126<br />

The New Vision, 2008.<br />

Courtesy: Galerie Daniel<br />

Buchholz, Cologne/Berlin.<br />

The Inchoate Incarnate:<br />

Bespoke costume for the<br />

artist, 2009. Courtesy:<br />

Galerie Daniel Buchholz,<br />

Cologne/Berlin.

129 Surface Screen<br />

Projection Production<br />

Still (Screen), 2006.<br />

Courtesy: Overduin and<br />

Kite, Los Angeles.<br />

Los Angeles ~ <strong>Frances</strong><br />

<strong>Stark</strong><br />

Los Angeles ~ <strong>Frances</strong> <strong>Stark</strong><br />

127

“wrote this in a letter to a friend”<br />

A letter! And to a friend, an intimate correspondence.<br />

“‘Art’ for me is only a means of reaching a higher level of ‘self.’”<br />

Musil’s book describes things with the exactitude of engineer, as if here were<br />

trying to capture the exact thing that he meant, rather than an approximation,<br />

a loose synonym, a flat cliche that conveyed little. To say the thing that you exactly<br />

mean to say is almost impossible, to find the precise shade of nuance makes<br />

communication almost impossible. The Man Without Qualities at some 7,000<br />

pages was never completed. Through the book, in the face of all this precision,<br />

there’s a yearning for the mysterious and mystical qualities of art.<br />

it’s a simple sentence, containing within its nouns (years, letter, artist, Musil,<br />

friend, art, self ) a miniature of a whole complex and brilliant career stretching<br />

and circling itself for twenty years, that of <strong>Frances</strong> <strong>Stark</strong>.<br />

<strong>Frances</strong> <strong>Stark</strong> is an artist, the kind of artist (i’m going to go ahead and declare)<br />

that <strong>Frances</strong> <strong>Stark</strong> describes robert Musil to be.<br />

There was a moment in the ’60s where artist Marcel broodthaers the poet became<br />

Marcel broodthaers the artist. He took a raft of unsold books of his poems<br />

(forty-four to be exact) and encased them in plaster, making a sculpture (Pense-<br />

Bête [reminder,] 1964).<br />

i used to think about this as literature failing to accommodate a visionary writer.<br />

That the community of readers and the practice of literature could hardly<br />

support (partly intellectually and more truly financially) someone as great as<br />

broodthaers, but that the art world, with its gobs of money, could. (One doesn’t<br />

here even known russian oligarchs or Saudi princes throwing money at literature).<br />

i felt like maybe we were losing some of our best writers to visual art.<br />

After talking to <strong>Frances</strong> in her studio, i had this moment of epiphany, a flash of<br />

astonishing awareness, that it was not so. writing had colonized art. Literature<br />

had burst its boundaries. The country of Literature had invaded the country of<br />

Art and claimed some of its territory. but when the US purchased Louisiana<br />

from napoleon, it didn’t stop being Louisiana, it went right on being Louisiana,<br />

just under the rubric and rules of a different domain.<br />

Lee Lozano’s piece of notebook paper on a pedestal as a piece of writing may<br />

have easily gotten lost, but here on the pedestal the writing has a presence, the<br />

action she describes on the notebook paper is a stand-in for a performance going<br />

on in the world, not only hers but ours.<br />

There was a moment in the Sixties when painters wanted to break free of the<br />

canvas, eve Hesse and Lee bontecou created works where the flat terrain of<br />

painting was insufficient to contain their ideas about what painting could be,<br />

they forced painting into the third dimension. Perhaps broodthaers did the<br />

same for writing. Though there were others to be sure putting text (and poetical<br />

writing) into art before or at about the same time, broodthaers’ gesture is a<br />

resonating one, a legend of art.<br />

what does it mean to be a writer writing in space? Look at the work of <strong>Frances</strong><br />

<strong>Stark</strong>. Though emerging from a literary tradition, she still wrestles with the<br />

problems of art history, visuality, and space, but through the potency of poetry<br />

and writing, a self realized with words.<br />

i call <strong>Frances</strong> <strong>Stark</strong> the letter writer because all of her works feel like a letter,<br />

perhaps even a love letter. She told me that once in school, she collected all her<br />

lover letters from an ex-boyfriend and then sent them to her professors. Using<br />

the raw material of life to deal with the problems of art history (her professors<br />

at the time were all very influential artists).<br />

when composing a love letter, one can agonize over the slightest turn of phrase,<br />

and the agony is a delicious one. Of all the writing i’ve done in my life, of which<br />

there has been a lot, i’ve never put as much energy, emotion, and care as i put<br />

into my love letters. in a love letter you have that agony which derives from the<br />

yearning to be as precise as possible, using the humbling materials of beautiful<br />

language. The best love letters have embedded in them the physical, sexual<br />

yearning of being apart from the object of your desire and in that you’ll use in<br />

their intimate composition everything you have to make yourself felt, to bridge<br />

the divide. As i describe it, i understand it may sound like sentimental drivel,<br />

but if you are as bright and engaged as <strong>Frances</strong> <strong>Stark</strong>, the letter grows in size<br />

and shape, it grows to encompass drawing and painting, performance and collage,<br />

all of the media that feel right to express clearly the exact dimensions of<br />

her thought and emotion.<br />

As writing has expanded its domain into the realm of art, <strong>Frances</strong> <strong>Stark</strong>’s love<br />

Mousse 26 ~ <strong>Frances</strong> <strong>Stark</strong><br />

128<br />

Above – A Torment Of Follies,<br />

installation view at Secession,<br />

Wien, 2008. Photo: Pez Hejduk.<br />

Down – Oh god, I’m so<br />

embarrassed, 2007. Courtesy:<br />

the artist and greengrassi,<br />

London.

Backside of the Performance, 2007.<br />

Courtesy: the artist. Photo Marcus Leith.<br />

letter to literature to philosophy to art to people<br />

in her life has expanded beyond the confines of a<br />

simple page with words scratched with a pen and<br />

into a lifetime of artmaking. Her exhibition at the<br />

Secession in Vienna in 2008, A Torment of Follies,<br />

dealt primarily with realizing a libretto derived<br />

from witold Gombrowicz’s Ferdydurke (another<br />

great novel of the twentieth century) through her<br />

own visual and textual practice as an artist, even in<br />

its realization as an exhibition, <strong>Frances</strong> <strong>Stark</strong> appears<br />

as a character giving asides and doubts as she<br />

brings the process of art into realization. its installation<br />

looks like a dress rehearsal for a folly, a theatrical<br />

revue, one in which the agents and armature<br />

of production, the playwright, the director, the<br />

sets, are all still there for the audience to see.<br />

even now her love letter expands, <strong>Stark</strong>’s most recent<br />

work involves a complex opera (“I’ve Had It!<br />

And i’ve Also Had it!”) realized with musicians<br />

Los Angeles ~ <strong>Frances</strong> <strong>Stark</strong><br />

and a vaudevillian backdrop that changes with<br />

the clarity of a Powerpoint presentation (another<br />

medium she’s used before), drawing from letters<br />

written to her and letters she’s written as well as<br />

life and literature. First realized at the Aspen Art<br />

Museum and to be performed this spring at the<br />

Hammer Museum in Los Angeles, the opera is performed<br />

by the artist standing on stage in a dress,<br />

designed by her, gauzy and black, and on the front<br />

are the white circle of numbers found on a rotary<br />

phone. The finale involves <strong>Frances</strong> removing the<br />

dress and standing in black shirt and pants, leaning<br />

over computer and doing a live transcription of<br />

Lady Gaga’s “Telephone”.<br />

And i leave off this essay, my letter to you, with<br />

Lady Gaga’s lines from her song. (How many<br />

of us have leaned on lyrics, and mixed tapes, to<br />

speak our feelings for us?) even in love however,<br />

we still need a break from the work of it some-<br />

di Andrew berArdini<br />

129<br />

times, not to overthink Lady Gaga or <strong>Frances</strong><br />

<strong>Stark</strong>’s referencing Lady Gaga too much, or love<br />

in general perhaps; talking about life and love is<br />

ever always going to be a shadow of physically<br />

and actually being alive. between talking and<br />

dancing, though it doesn’t always happen like<br />

this, i’d rather dance. And when we can’t dance,<br />

the words all there, nearly always ready for us to<br />

use them.<br />

Stop callin’, stop callin’,<br />

I don’t wanna think anymore!<br />

I left my head and my heart on the<br />

dance floor.<br />

Stop callin’, stop callin’,<br />

I don’t wanna talk anymore!<br />

I left my head and my heart on the<br />

dance floor.<br />

Cos’è una lettera d’amore? La sofferenza piacevolissima di rintracciare faticosamente le parole<br />

più adatte, applicare la precisione più sottile nell’uso di una lingua comunque insufficiente a<br />

esprimere l’odore della persona amata o il movimento delle sue mani. L’opera di <strong>Frances</strong> <strong>Stark</strong><br />

è per Andrew Berardini un’enorme, bellissima poesia d’amore in tre dimensioni, e lei<br />

una scrittrice che scrive nello spazio...

Scrittori citati in Collected writings: 1993-2003 di<br />

Oscar Wilde<br />

Friedrich Nietzsche<br />

Robert Musil<br />

P.D. Ouspenskij<br />

G.I. Gurdjieff<br />

Virginia Woolf<br />

E.H. Gombrich<br />

Gaston Bachelard<br />

Emily Dickinson<br />

Howard Singerman<br />

John Keats (non IL John<br />

Keats)<br />

Dorothy Parker<br />

Pierre Bourdieu<br />

Rudolf Steiner<br />

(alcuni sono ufficialmente artisti, altri sono storici, critici, seguaci della new<br />

Age; per i nostri scopi sono tutti scrittori)<br />

Altri scrittori che mi ha detto essere importanti per lei, ma che non sono citati<br />

nell’elenco precedente:<br />

Witold Gombrowicz<br />

Ingeborg Bachmann<br />

...La chiarezza cui aspiriamo è certo una chiarezza completa. Ma questo vuol<br />

dire soltanto che i problemi filosofici devono svanire completamente.<br />

Ludwig wittgenstein, Ricerche filosofiche<br />

Anziché di un’ermeneutica, abbiamo bisogno di un’erotica dell’arte.<br />

Susan Sontag, Contro l’interpretazione<br />

Un singolo paragrafo sull’opera di <strong>Frances</strong> <strong>Stark</strong> prima di cominciare a parlare di<br />

altre cose:<br />

L’artista losangelina <strong>Frances</strong> <strong>Stark</strong> rappresenta, nella sua opera, il complesso e<br />

bellissimo sforzo richiesto per esprimere in modo chiaro e preciso le dimensioni<br />

del pensiero e dell’emozione. Fatta principalmente di testi e di delicati disegni<br />

al tratto (ma anche di performance, collage e dipinti), la pratica artistica personalissima<br />

di <strong>Frances</strong> <strong>Stark</strong> ce la rivela come artista intenta a cimentarsi con la<br />

letteratura, la filosofia e la storia dell’arte e con i modi in cui queste influenzano<br />

il processo di produzione dell’arte e la vita quotidiana. Vedere una sua mostra è<br />

un po’ come leggere un romanzo di idee tutto d’un fiato. Per <strong>Stark</strong> mille parole<br />

valgono quanto un’immagine.<br />

Compunction’s Work, 2002.<br />

Courtesy: the artist and greengrassi, London.<br />

Jonathan Pylypchuk<br />

Lane Relyea<br />

J.D. Salinger<br />

Gustave Flaubert<br />

David Foster Wallace<br />

Curtis White<br />

Ludwig Wittgenstein<br />

Jürgen Habermas<br />

Jimmie Durham<br />

Raymond Pettibon<br />

Novalis<br />

Joan Didion<br />

Goethe<br />

Thomas Bernhard<br />

Henry Miller<br />

Mousse 26 ~ <strong>Frances</strong> <strong>Stark</strong><br />

130<br />

§ § §<br />

Tutto ciò che viene scritto e che deve essere letto da altri è una sorta di lettera.<br />

Una persona che scrive ad un’altra. da me a te.<br />

il saggio che sto scrivendo e che voi state leggendo, così come la maggior parte<br />

degli scritti che si trovano nelle riviste appartengono, solitamente, alla varietà<br />

più impersonale. re: Oggetto. egregi signori. A chi di competenza. Alcuni<br />

scritti pubblicati nel mondo sono vere lettere, indirizzate da una persona ad<br />

un’altra. il romanzo epistolare. La poesia d’amore.<br />

Sebbene io sia certo che alcuni poeti si siedano e creino dal nulla una bellezza<br />

ideale come esercizio (per me noioso e piuttosto bizzarro) che fa parte di una<br />

strategia formale dell’amore, l’amore stesso (tranne quello ingenuo) non è un<br />

ideale, ma qualcosa di specifico. Amiamo la grazia delle lunghe mani della persona<br />

amata quando gesticolano durante una conversazione. Amiamo quando<br />

lui o lei sta in punta di piedi, il corpo nudo proteso in avanti e le braccia allungate<br />

per chiudere una finestra. Amiamo il suo odore, unico e inconfondibile,<br />

quell’odore così difficile da spiegare a parole, anche se vale la pena di provarci:<br />

un miscuglio di chiodi di garofano e di olio per motori, oppure l’odore di una<br />

nave che portava un carico di cannella e che è affondata nei pressi di una piantagione<br />

caraibica di canna da zucchero proprio mentre cominciavano a bruciare le<br />

canne, oppure ancora il profumo di erba appena falciata e di vecchi libri. Potrei<br />

continuare all’infinito.<br />

Conosciamo l’odore del nostro amato come solo un amante può conoscerlo,<br />

anche se è impossibile descriverlo in modo preciso. Per noi è qualcosa di veramente<br />

specifico e, da scrittori di lettere d’amore, poeti minori, proviamo a dirlo<br />

a parole, ma falliamo miseramente. Le poesie vengono stampate e ristampate,<br />

così capita che, secoli dopo, in un’antologia dalle pagine sottili quanto carta<br />

velina, veniamo a scoprire quel che aveva scritto un inglese arrapato alla donna<br />

da lui desiderata. Magari ci immedesimiamo nell’amante, imparando a memoria<br />

versi da recitare alla laureanda in letteratura che siede accanto a noi in classe – la<br />

camicetta slacciata che lascia intravedere la pelle liscia e bruna del suo petto, le<br />

labbra increspate mentre riflette. O ci immedesimiamo nell’oggetto del desiderio,<br />

nella sensazione impetuosa dell’essere desiderati, nell’immagine della lussuria.<br />

Scostandosi un po’, la poesia acquista significato quando ha un significato<br />

per ciascuno di noi, presi singolarmente.<br />

Voglio citare alcuni passi dei testi di <strong>Frances</strong> <strong>Stark</strong>. detesto questo genere di<br />

minuziose vivisezioni del linguaggio, ma penso che, smontandolo, forse potrò<br />

mostrarvi qualcosa di bellissimo. Lo prometto, le parole torneranno illese là da<br />

dove sono venute.<br />

Cent’anni fa, il mio artista preferito, l’autore Rubert Musil, scrisse in una lettera ad<br />

un amico: “L’‘arte’ per me è solo un modo per elevare il ‘sé’”<br />

“Cent’anni fa”<br />

Una semplice indicazione temporale, ma la sua precisione implica un parallelismo<br />

tra Musil allora e <strong>Stark</strong> oggi.<br />

“il mio artista preferito, l’autore Robert Musil”<br />

robert Musil (6 novembre 1880 – 15 aprile 1942), uno scrittore austriaco, il cui<br />

libro più famoso, L’uomo senza qualità, è una descrizione dettagliata e iperossessiva<br />

della classe dirigente viennese appena prima del collasso dell’impero<br />

Austro-Ungarico, da molti considerato uno dei grandi romanzi del novecento.<br />

Vedere uno scrittore descritto come l’artista preferito è indicativo, anche se di<br />

questo si parlerà più avanti.<br />

“scrisse in una lettera ad un amico”<br />

Una lettera! e ad un amico: una corrispondenza intima.<br />

“L’‘arte’ per me è solo un modo per elevare il ‘sé’”<br />

il libro di Musil descrive le cose con la precisione di un ingegnere, come se<br />

cercasse di catturare proprio ciò che lui aveva in mente anziché un’approssimazione,<br />

un vago sinonimo, un piatto cliché capace di trasmettere ben poco.<br />

dire esattamente la cosa che si aveva in mente è quasi impossibile. La ricerca<br />

della giusta sfumatura rende la comunicazione quasi impossibile. L’uomo senza<br />

qualità, nonostante le sue circa 7.000 pagine non fu mai completato. nel libro, a<br />

dispetto di tutta questa precisione, vi è il desiderio e la ricerca di qualità misteriose<br />

e mistiche nell’arte.<br />

È una frase semplice, che contiene, nei suoi sostantivi (anni, lettera, artista, Musil,<br />

amico, arte, sé), la miniatura di un’intera carriera, complessa e brillante, che<br />

si è estesa e ha girato in tondo per vent’anni: la carriera di <strong>Frances</strong> <strong>Stark</strong>.

Surface Screen<br />

Projection Production<br />

Still (Screen), 2006.<br />

Courtesy: Overduin and<br />

Kite, Los Angeles.<br />

Los Angeles ~ <strong>Frances</strong> <strong>Stark</strong><br />

131<br />

<strong>Frances</strong> <strong>Stark</strong> è un’artista, il genere d’artista che (sto per spingermi a dichiarare)<br />

lei riconosce in Musil.<br />

C’è stato un momento, negli anni Sessanta, in cui Marcel broodthaers il poeta è<br />

diventato Marcel broodthaers l’artista. Ha comprato una gran quantità di volumi<br />

invenduti delle sue poesie (quarantaquattro per l’esattezza) e li ha racchiusi<br />

nel gesso, creando una scultura (Pense-Bête [Promemoria], 1964).<br />

Pensavo che questo fosse il sintomo di un’incapacità della letteratura di accogliere<br />

uno scrittore visionario, che la comunità dei lettori e l’attività letteraria<br />

avessero difficoltà a sostenere (in parte da un punto di vista intellettuale, ma più<br />

verosimilmente da un punto di vista economico) un grande come broodthaers,<br />

mentre il mondo dell’arte, con tutto il suo denaro, era in grado di farlo.<br />

(del resto non si sente nemmeno di oligarchi russi o di principi sauditi che<br />

spendano fiumi di soldi per la letteratura.) Ho avuto la sensazione che forse<br />

stessimo perdendo alcuni dei nostri migliori scrittori in favore delle arti visive.<br />

dopo aver parlato con <strong>Frances</strong> nel suo studio, ho avuto un’epifania, un lampo<br />

di stupefacente consapevolezza, e ho capito che non era così. La scrittura aveva<br />

colonizzato l’arte. La Letteratura aveva fatto saltare i muri di separazione e valicato<br />

i propri confini. il paese della Letteratura aveva invaso il paese dell’Arte e<br />

rivendicato una parte del suo territorio. Ma quando gli Stati Uniti acquistarono<br />

la Louisiana da napoleone, quella non smise di essere Louisiana, ma continuò<br />

ad essere Louisiana, semplicemente sottostando alle regole di un diverso dominatore.<br />

il pezzo di carta di quaderno su un piedistallo di Lee Lozano, in quanto brano<br />

di scrittura, avrebbe potuto facilmente andar perso, ma qui, sul piedistallo, la<br />

scrittura possiede una presenza: l’azione che Lee Lozano descrive sulla carta da<br />

quaderno sta a simboleggiare una performance che ha luogo nel mondo, non<br />

solo il suo ma anche il nostro.<br />

C’è stato un momento negli anni Sessanta in cui i pittori hanno voluto liberarsi<br />

dalla tela. eve Hesse e Lee bontecou hanno creato opere dove il piatto terreno<br />

della pittura non era sufficiente per contenere le loro idee sulle possibilità<br />

della pittura stessa. Così hanno forzato la pittura affinché entrasse nella terza<br />

dimensione. Forse broodthaers ha fatto lo stesso con la scrittura. Sebbene vi<br />

siano stati certamente altri che, prima di lui o pressappoco nello stesso periodo,<br />

hanno trasferito testi (e scrittura poetica) nell’arte, il gesto di broodthaers ha<br />

una risonanza particolare, è una leggenda dell’arte.<br />

Che cosa significa essere uno scrittore che scrive nello spazio? Guardate il lavoro<br />

di <strong>Frances</strong> <strong>Stark</strong> che, sebbene emerga da una tradizione letteraria, vede la<br />

sua autrice ancora alle prese con i problemi della storia dell’arte – la visualità, lo<br />

spazio – ma attraverso la potenza della poesia e della scrittura, un sé realizzato<br />

con le parole.<br />

Chiamo <strong>Frances</strong> <strong>Stark</strong> la scrittrice di lettere perché tutte le sue opere sembrano<br />

una lettera, forse persino una lettera d’amore. Mi ha raccontato che una volta,<br />

quando andava ancora a scuola, ha raccolto tutte le lettere d’amore che un ex<br />

fidanzato le aveva scritto, e le ha spedite ai suoi professori. Usando il materiale<br />

grezzo della vita per discutere dei problemi della storia dell’arte (i suoi professori,<br />

all’epoca, erano tutti artisti influenti).<br />

Quando si scrive una lettera d’amore si possono passare ore ad arrovellarsi su<br />

un giro di frase, e quel rovello risulta delizioso. non ho mai messo tanta energia,<br />

emozione e attenzione nelle cose che ho scritto nella mia vita – e di cose ne<br />

ho scritte parecchie – quanto nelle mie lettere d’amore. in una lettera d’amore<br />

c’è quel tormento che deriva dal desiderio di essere il più precisi possibile,<br />

servendosi degli avvilenti materiali di una lingua pur bellissima. Le migliori<br />

lettere d’amore hanno dentro di sé il desiderio fisico, sessuale, di essere separate<br />

dall’oggetto del proprio desiderio affinché nella composizione si possa usare<br />

tutto ciò che è necessario per farsi percepire, per colmare la distanza. Mentre<br />

descrivo tutto questo mi rendo conto che potrebbero sembrare solo stupidaggini<br />

sentimentali, ma se si è brillanti e impegnati come lo è <strong>Frances</strong> <strong>Stark</strong>, la lettera<br />

cresce in grandezza e cambia forma, racchiudendo dentro di sé il disegno e la<br />

pittura, la performance e il collage, tutti media che appaiono adatti ad esprimere<br />

in modo chiaro le esatte dimensioni del suo pensiero e della sua emozione.<br />

Poiché la scrittura ha allargato il suo dominio al reame dell’arte, la lettera<br />

d’amore di <strong>Frances</strong> <strong>Stark</strong> alla letteratura, alla filosofia, all’arte e alle persone<br />

della sua vita si è allargata oltre i confini di una singola pagina ricoperta di parole<br />

tracciate a penna, fino ad abbracciare una vita intera di lavoro come artista. La<br />

sua mostra al Palazzo della Secessione a Vienna nel 2008, A Torment of Follies,<br />

trattava essenzialmente della realizzazione di un libretto a partire da Ferdydurke<br />

di witold Gombrowicz (un altro grande romanzo del novecento) servendo-

si della propria pratica artistica, visiva e testuale.<br />

Anche nella realizzazione della mostra, <strong>Frances</strong><br />

<strong>Stark</strong> appare come un personaggio che si lancia in<br />

digressioni e avanza dubbi nel momento stesso in<br />

cui porta a compimento il processo artistico. L’installazione<br />

si presenta come una prova costumi per<br />

uno spettacolo di varietà, di teatro di rivista, in cui<br />

gli agenti e l’armatura della produzione, il drammaturgo,<br />

il regista, le scenografie sono ancora lì<br />

per essere viste dal pubblico.<br />

Anche adesso la sua lettera d’amore si sta espandendo.<br />

il suo lavoro più recente consiste in una<br />

complessa opera (“I’ve Had It! And i’ve Also Had<br />

it!”) realizzata con musicisti e con un fondale da<br />

vaudeville che cambia con la chiarezza di una presentazione<br />

Powerpoint (un altro medium da lei già<br />

utilizzato in precedenza), attingendo da lettere che<br />

le sono state scritte e che lei ha scritto, così come<br />

dalla vita e dalla letteratura. Messa per la prima volta<br />

in scena all’Aspen Art Museum e in programma<br />

per la prossima primavera all’Hammer Museum di<br />

Mousse 26 ~ <strong>Frances</strong> <strong>Stark</strong><br />

Another Chorus Individual (On Aspiration),<br />

2007. Courtesy: the artist.<br />

Los Angeles, l’opera è performata dalla stessa artista,<br />

che sta in piedi in scena, con indosso un abito<br />

nero e trasparente che ha disegnato, mentre di<br />

fronte a lei vi sono i cerchi bianchi dei numeri di un<br />

telefono a disco. nel finale <strong>Frances</strong> si toglie l’abito,<br />

rimane in pantaloni e maglietta neri, si china su un<br />

computer e comincia a trascrivere dal vivo le parole<br />

della canzone “Telephone” di Lady Gaga.<br />

Concludo questo mio saggio – la mia lettera per<br />

voi – con alcuni versi della canzone di Lady Gaga.<br />

(Quanti di noi si sono affidati ai testi delle canzoni<br />

e alle compilation musicali per esprimere i propri<br />

sentimenti?) Perfino in amore qualche volta abbiamo<br />

bisogno di prenderci una pausa dalle fatiche<br />

che lui stesso richiede – tanto per non cadere in<br />

un eccesso di analisi su Lady Gaga o sul fatto che<br />

<strong>Frances</strong> <strong>Stark</strong> la citi. O forse dobbiamo prenderci<br />

una pausa dall’amore in generale. Parlare di vita<br />

e di amore sarà sempre e solo un’ombra dell’esistenza<br />

fisica e reale. Tra parlare e ballare, anche<br />

se non è sempre così, preferisco ballare. e quando<br />

132<br />

non possiamo ballare, le parole sono tutte lì, quasi<br />

sempre pronte per essere usate.<br />

Stop callin’, stop callin’,<br />

I don’t wanna think anymore!<br />

I left my head and my heart on the<br />

dance floor.<br />

Stop callin’, stop callin’,<br />

I don’t wanna talk anymore!<br />

I left my head and my heart on the<br />

dance floor.<br />

[Smetti di chiamare,smetti di chiamare,<br />

non voglio più pensare!<br />

Ho lasciato mente e cuore sulla pista da ballo.<br />

Smetti di chiamare, smetti di chiamare,<br />

non voglio più parlare!<br />

Ho lasciato mente e cuore sulla pista da ballo.]

133

Michael Ned Holte: <strong>Frances</strong> <strong>Stark</strong>, www.artforum.com, NYC, Sept 1, 2010<br />

<strong>Frances</strong> <strong>Stark</strong>, Oh God I'm So Embarrassed, 2007,<br />

collage on paper, 81 x 52 1/2".<br />

<strong>Frances</strong> <strong>Stark</strong><br />

MIT LIST VISUAL ARTS CENTER<br />

CAMBRIDGE<br />

Through January 2 2011<br />

Curated by João Ribas<br />

The title of <strong>Frances</strong> <strong>Stark</strong>’s first US museum survey, “This could become a gimick [sic] or an<br />

honest articulation of the workings of the mind,” not only confirms the Los Angeles–based artist’s<br />

ongoing investment in language but also gamely foregrounds the self-‐critical deliberation that<br />

frequently emerges as the subject of her work. Comprising more than fifty works made between<br />

1992 and the present, this exhibition will highlight the full range of <strong>Stark</strong>’s nimble practice—<br />

elegant works on paper incorporating found text (from Emily Dickinson’s to Robert Musil’s),<br />

collages repurposing junk mail (including gallery postcards),and a PowerPoint piece (Structures<br />

That Fit My Opening and Other Parts Considered in Relation to Their Whole, 2006) that uses the<br />

drily corporate format to unexpectedly moving effect by addressing the everyday convolutions of<br />

raising a child and teaching while attending to the difficulties of making art in fleeting moments.

Stewart Oksenhorn, She's got it! <strong>Stark</strong> gives Aspen musical a spin, The Aspen Times,<br />

Aspen, CO, June 30, 2010.<br />

“The Inchoate Incarnate: After a Drawing, Toward an Opera, but before a Libretto Even Exists”, by <strong>Frances</strong><br />

<strong>Stark</strong>, is featured in <strong>Stark</strong>'s theater piece, “I've Had It! and I've Also Had It!” showing Wednesday at Aspen's<br />

Wheeler Opera House.<br />

Jason Dewey

ASPEN — In “I've Had It!”, a musical that debuted at the Wheeler Opera House in<br />

1951, a Hotel Jerome bellhop watches as his girlfriend falls for an Aspen Music<br />

Festival composer, who is in Aspen working on a new piece of music. With the<br />

help of his bartending friend, the bellhop exposes the pomposity and<br />

pretentiousness of the composer by demonstrating, for a room full of critics, that<br />

the new composition is actually a familiar pop song, played backward.<br />

It's a simple, screwball comedy of class warfare. But as Los Angeles artist<br />

<strong>Frances</strong> <strong>Stark</strong> revisits the work Wednesday at the Wheeler, as part of the Aspen<br />

Art Museum's Restless Empathy group exhibition, simplicity doesn't seem to be<br />

part of the formula. Retitled “I've Had It! And I've Also Had It!”, the reworked<br />

version introduces <strong>Stark</strong>'s thoughts on art criticism, symmetry, the divide<br />

between high and low art, opera, and the frustrations the artist has encountered<br />

in her career.<br />

The production, presented in collaboration with the Aspen Music Festival,<br />

features two string trios and back-‐up dancers; a costume — titled “The Inchoate<br />

Incarnate: After a Drawing, Toward an Opera, but before a Libretto Even Exists,”<br />

and created by <strong>Stark</strong> before she conceived of “I've Had It! And I've Also Had It!”<br />

— and <strong>Stark</strong> herself in her first performance piece.<br />

When she visited Aspen last November to begin work on her Restless Empathy<br />

project, <strong>Stark</strong>, who had made two trips here earlier in her life to visit family<br />

friends, zeroed in on the 121-‐year-‐old Wheeler. “Because in the Wheeler, you get<br />

the whole history of Aspen,” she said.<br />

<strong>Stark</strong>, a 43-‐year-‐old Southern California native who lives in Los Angeles and<br />

often uses text in her visual work, went to the Pitkin County Library and quickly<br />

found an out-‐of-‐date brochure detailing the history of the Wheeler. When she<br />

saw a mention of “I've Had It!” she knew the old, forgotten musical would be the<br />

foundation of her own piece.<br />

<strong>Stark</strong> was aware that several prominent visual artists — including Denmark's<br />

Olafur Eliasson, who has exhibited work in Aspen — had recently ventured into<br />

opera. And a friend of <strong>Stark</strong>'s, looking at <strong>Stark</strong>'s recent series of large-‐scale<br />

drawings, likened the work to a libretto, and gave the series the alternate title,<br />

“Notes to a Pedagogical Opera.” <strong>Stark</strong> had already made a costume that looked<br />

like an outfit you'd find in a modernist stage production. And when she read the<br />

title of the 1951 musical, she saw the stars align.<br />

“I couldn't believe the title,” <strong>Stark</strong> said. “‘I've Had It!' — I've said that over and<br />

over.” She also noted that tweaking the title, making it “I've Had It! And I've Also<br />

Had It!” is a neat play on the “empathy” theme. (The Restless Empathy exhibition,<br />

which runs through July 18, also features benches around Aspen inscribed with<br />

quotes by the late Hunter S. Thompson, an installation near the Aspen Center for<br />

Physics, a large-‐scale photograph at the base of Aspen Mountain, and works at<br />

the Aspen Art Museum.)

<strong>Stark</strong> said the high art/low art divide spotlighted in the original “I've Had It!” has<br />

been a theme in her past work. “In my writing, I definitely address that. It's the<br />

issue of pomposity and fraudulence.”<br />

Criticism, too, is an idea raised in the 1951 musical that interests her. “It's about<br />

a work's reception: The bellhop thinks [the composition] is crap; the critics are<br />

supposedly duped by hype,” <strong>Stark</strong> said. “So the reception — and production — of<br />

work is a big theme that runs through my practice.”<br />

<strong>Stark</strong> also engages in a narrative of self-‐reflection. The performance has her<br />

showing slides, commenting on them, and looking at her own career and her<br />

work: “Why I've had it, and what I've had it with,” she said. “A subtheme is, ‘Why<br />

can't I write?” Part of her libretto is a quote from the Polish writer Witold<br />

Gombrowicz: “Instead of marching forward and erect like the great writers of all<br />

time, I'm revolving ridiculously on my own heels.”<br />

Perhaps the most obvious, and prescient angle of the original “I've Had It!”, the<br />

theme of class warfare in Aspen, gets underplayed in the new production. <strong>Stark</strong><br />

said she doesn't want to ignore the theme, but notes, “I'm really walking on<br />

eggshells about that.”<br />

Instead, <strong>Stark</strong> has a perspective that reveals the visual artist in her. The heart of<br />

her interpretation is the various layers of symmetry. “Really, the most<br />

compelling aspect of the play is the formal symmetry of it,” she said. “There's the<br />

song, and it's played backward and forward. There's the two string trios. There's<br />

a complete binary aspect to understand.<br />

“I think what I'm trying to do is set them spinning so you don't know what's front<br />

and back. Spinning is definitely the subtle motif in this work.”

Jessica Lack, Artist of the week 46: <strong>Frances</strong> <strong>Stark</strong>, guardian.co.uk, London, June 24, 2009.<br />