Davies, Lucy, Roe Ethridge: Commercial Break, The ... - Greengrassi

Davies, Lucy, Roe Ethridge: Commercial Break, The ... - Greengrassi

Davies, Lucy, Roe Ethridge: Commercial Break, The ... - Greengrassi

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>Davies</strong>, <strong>Lucy</strong>, <strong>Roe</strong> <strong>Ethridge</strong>: <strong>Commercial</strong> <strong>Break</strong>, <strong>The</strong> Telegraph, London, March 25, 2011 <br />

<strong>Roe</strong> <strong>Ethridge</strong>: <strong>Commercial</strong> break <br />

<strong>Roe</strong> <strong>Ethridge</strong>'s pictures blur the boundaries between advertising and art photography. <br />

His work has put him in line for this year's Deutsche Börse prize <br />

<br />

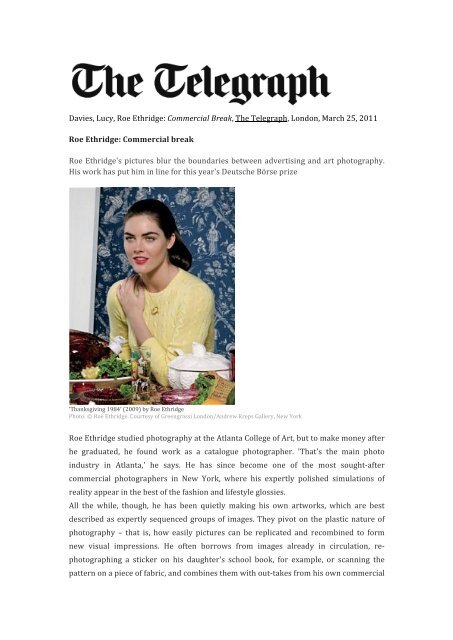

'Thanksgiving 1984' (2009) by <strong>Roe</strong> <strong>Ethridge</strong> <br />

Photo: © <strong>Roe</strong> <strong>Ethridge</strong>. Courtesy of <strong>Greengrassi</strong> London/Andrew Kreps Gallery, New York <br />

<strong>Roe</strong> <strong>Ethridge</strong> studied photography at the Atlanta College of Art, but to make money after <br />

he graduated, he found work as a catalogue photographer. 'That's the main photo <br />

industry in Atlanta,' he says. He has since become one of the most sought-‐after <br />

commercial photographers in New York, where his expertly polished simulations of <br />

reality appear in the best of the fashion and lifestyle glossies. <br />

All the while, though, he has been quietly making his own artworks, which are best <br />

described as expertly sequenced groups of images. <strong>The</strong>y pivot on the plastic nature of <br />

photography – that is, how easily pictures can be replicated and recombined to form <br />

new visual impressions. He often borrows from images already in circulation, re-photographing<br />

a sticker on his daughter's school book, for example, or scanning the <br />

pattern on a piece of fabric, and combines them with out-‐takes from his own commercial

work, harking back to a time when photographers such as Irving Penn and Man Ray sat <br />

comfortably in both commercial and art camps. <br />

This collision of high and low modes is central to his art. <strong>The</strong> manufactured perfection of <br />

the commercial world injects his work with a kitsch sheen, and while his portraits of <br />

women nod to Picasso and Matisse, they also twinkle with humour. 'It became obvious <br />

that pulling things from one side to the other was how photography had to work for me,' <br />

he says. <br />

<strong>Ethridge</strong>, 41, never intends his work to generate a precise meaning. In his mind, the <br />

most disappointing gallery experience is when he feels he has finished with the <br />

exhibition before he has even left the building. 'I think work should take some time to <br />

open up,' he says, 'and the intentionally mysterious combinations of images in my work <br />

are to ensure that you continue to mull over it for some time after you have seen it.' <br />

His show at the Arles Photography Festival, for which he is nominated for this year's <br />

Deutsche Börse Photography Prize, is meant to radiate the idea of seasons. 'It's not <br />

conceptual,' he says. 'It's about whatever sticks. I don't have a script. I have an idea that I <br />

work around, but don't necessarily solve.'

Wilson, Michael, <strong>Roe</strong> <strong>Ethridge</strong>: Le Luxe, Time Out, New York, May 31<br />

Review: <strong>Roe</strong> <strong>Ethridge</strong>, “Le Luxe”<br />

<strong>The</strong> artist’s photos only seem to tell a story.<br />

LeLe<br />

Photograph: Courtesy Andrew Kreps Gallery<br />

<strong>Roe</strong> <strong>Ethridge</strong>’s photographs at once deny and utterly depend on the possibility of narrative. Self-consciously<br />

diverse in terms of origin and theme, they acquire meaning only when considered en masse, though their order is<br />

never quite linear or even logical. <strong>Ethridge</strong> shares with many of his contemporaries an absolute ease with the<br />

process of shifting between original and appropriated images, using the camera as both instrument and sampler.<br />

As “Le Luxe” demonstrates, this constitutes both a freedom and a challenge: If you can do anything, what do you<br />

do? In the case of this particular show, which contains new work alongside older shots, the answer lies in<br />

examining a range of ideas around the good life alluded to in its title, as well as in a more random exploration of<br />

life in the city.<br />

A few photos were taken as part of a commission to document the construction of Goldman Sachs’ new<br />

headquarters, but they don’t stand out from an outwardly heterogeneous pack. Equally if not more imposing are<br />

the American Beauty–evoking image of a plastic bag drifting past a red-painted wall, a weirdly doctored take on<br />

the promo poster for turn-of-the-’90s flick Point <strong>Break</strong> and a pixelated close-up of a gift-wrap bow. Added to this<br />

mix is a sculptural component in the form of two empty shelving units, one in pine, the other shiny stainless steel.<br />

Seemingly awaiting “content,” these mute objects take on an almost heraldic role in this context, signifying the<br />

artist’s role as collector, collator and archivist.

Rosenberg, Karen, <strong>Roe</strong> <strong>Ethridge</strong>: Le Luxe, <strong>The</strong> New York Times, NYC, June 16, 2011.<br />

ROE ETHRIDGE: ‘Le Luxe’<br />

525 West 22nd Street, Chelsea<br />

Through July 2<br />

Visitors to <strong>Roe</strong> <strong>Ethridge</strong>’s latest show, his fifth solo at Kreps, must maneuver<br />

around a pine shelving unit. It’s just one of several barriers breached in this wry<br />

exhibition.<br />

Here, as is his wont, Mr. <strong>Ethridge</strong> mixes commissioned and more personal work<br />

with a smart editorial sensibility. <strong>The</strong> commercial, in this case, is fairly distinct: a<br />

six-year assignment from the investment bank Goldman Sachs, which hired him<br />

to document the construction of its new headquarters downtown. One of the<br />

pleasures of this show is seeing Mr. <strong>Ethridge</strong> apply his subtle, scattershot<br />

approach to a powerful corporation with a tightly controlled image.<br />

He begins with the 2005 groundbreaking, zooming in on Senator Hillary Clinton<br />

and Henry Paulson, then the Goldman chairman, so that a public ceremony<br />

becomes a tense tête à tête. Later, in “Sand Pit 3,” he captures the swirling,<br />

primordial ooze of the foundation. And in an exterior shot from 2009, he catches<br />

the edge of a banner so that the word “Money” intrudes on the rising building<br />

frame. (That frame, by the way, is echoed in the shelving unit and in a shorter,<br />

stainless-steel bookcase.) More images from the site can be found in an<br />

accompanying book, also titled “Le Luxe,” which may be an easier entry point for<br />

viewers who are new to Mr. <strong>Ethridge</strong>’s work.<br />

Conventional photodocumentary narrative seems entirely absent from the second<br />

half of the show, where a rephotographed poster from the movie “Point <strong>Break</strong>”<br />

(with Mr. <strong>Ethridge</strong> in Patrick Swayze’s role) hangs opposite dusky shots of the<br />

Tokyo skyline. <strong>The</strong>re’s a pixellated image of a giant red bow, too, though Mr.<br />

<strong>Ethridge</strong> has made clear that he is not one to tie things up in a pretty package.<br />

A version of this review appeared in print on June 17, 2011, on page C27 of the New York edition with the<br />

headline: <strong>Roe</strong> <strong>Ethridge</strong>: ‘Le Luxe’.

Lokke, Maria, <strong>Roe</strong> <strong>Ethridge</strong>: “Le Luxe”, <strong>The</strong> New Yorker, NYC, June 28, 2011.<br />

ROE ETHRIDGE’S “LE LUXE”<br />

From 2005 to 2010, the photographer <strong>Roe</strong> <strong>Ethridge</strong> was commissioned to photograph the construction<br />

of the Goldman Sachs building in lower Manhattan. Documents from this project serve as the backbone<br />

of his most recent book, “Le Luxe,” which pieces together an eclectic and often mysterious portrait of<br />

luxury culture. In the book, photographs from various stages of the building’s development alternate<br />

with<br />

seemingly random glimpses of the odd corners and loose ends of American leisure and luxury class:<br />

newspaper clippings on exotic pets running loose in Florida, screen grabs from a live feed of the<br />

Rockaway Beach surf line, a photo of a floating “I

Setareh, Candice, <strong>Roe</strong> <strong>Ethridge</strong>: Le Luxe II BHGG, Hellion magazine, Los Angeles, June 24, 2011.<br />

(© <strong>Roe</strong> <strong>Ethridge</strong>. Courtesy Gagosian Gallery. Photography by the Douglas M. Parker Studio)<br />

<strong>Roe</strong> <strong>Ethridge</strong>: Le Luxe II BHGG<br />

By Candice Setareh<br />

June 24th 2011<br />

<strong>The</strong> Gagosian Gallery’s are nothing short of chic, modern, and highly admired. With eleven<br />

gallery locations around the world; in cities such as New York, London, Paris and Rome- its high<br />

acclaim is of no surprise and without many objections. It’s the only art gallery of it’s kind to<br />

gracefully carry an influential appeal that is sought after and often imitated. So, it’s not a surprise<br />

that many of the exhibitions have gathered more guests then most major modern art museums.<br />

Thus, the reason for the many comparisons to a phenomenon. With the support and admiration<br />

from art enthusiasts and the general public alike, - artists consider having their pieces displayed at<br />

any of the Gagosian galleries -something similar to a euphoric experience. (I’m sure Picasso and<br />

Willem would have agreed) Thus, the opportunity to view pieces from the likes of ;Pablo Picasso,<br />

Willem De Kooning, Damien Hirst, and Joel Morrison are priceless and should not be<br />

overlooked.<br />

<strong>The</strong> newest artist who has joined this exclusive and fortunate group is- <strong>Roe</strong> <strong>Ethridge</strong>. <strong>The</strong><br />

Gagosian Gallery in Beverly Hills is presenting an exhibition of his photos from June 9, 2011<br />

through July 22, 2011. His unique interpretation of imagery in combination with his seamless<br />

approach to manipulating and duplicating photographs, makes his pieces, at their best- truly<br />

authentic to himself. <strong>The</strong> pieces from Le Luxe don’t stray far from <strong>Ethridge</strong>’s spontaneous yet

staged approach to capturing imagery from different genres. For example, he combines<br />

commercial images already in circulation in other contexts with conceptual pieces such as,<br />

vintage movie posters, and fashion models. He is clearly talented at seamlessly imposing his view<br />

on the juxtaposition of objects to his audience. For example; “in this exhibition, he juxtaposes<br />

polished photographs of posed models, such as Marloes Horst (2010) and Louise (2011), with<br />

gritty still life’s of ashtrays (Butts 1, Butts 2, and Butts 3, 2010) and the grainy pages of a<br />

newspaper (Plane Crash at Sea, 2004-2011).” (Gagosian Gallery) Lastly, it seems as though he is<br />

driven by the concept of presenting an allusion that is often too difficult to ascertain. He edits<br />

the pieces with a controlled complexity that no one but himself will ever probably understand,<br />

yet this dose of mystery is exactly what is drawing people in by the masses. Le Luxe will continue<br />

to show at the Gagosian Gallery in Beverly Hills through July 22, 2009. Visit their website at<br />

gagosian.com for more information

Prize fighters, Time Out London, April 13, 2011<br />

Prize fighters<br />

<strong>The</strong> final four in the Deutsche Börse Photography Prize 2011, rated<br />

and reviewed<br />

As the Photographers’ Gallery gets a facelift, we go underground to see the Deutsche<br />

Börse Photography Prize in a new venue and to rate the finalists’ chances in this £30k<br />

shutter showdown<br />

<strong>Roe</strong> <strong>Ethridge</strong><br />

For a fluorescent lesson in the dissonances of capitalism, see <strong>Ethridge</strong>. <strong>The</strong> American artist<br />

wilfully ignores the barrier between commercial photography and art, with the pleasing result<br />

that you’re never quite sure if he’s trying to sell you something. That bland beauty at<br />

Thanksgiving dinner, sandwiched between a weirdly shiny turkey and a Japanese wall<br />

hanging: what is she offering, exactly? And why does she look so wrong? Actually, she’s a<br />

model, and the food has been styled. But that helps only in the way that buying a lipstick<br />

helps a woman feel beautiful: it’s a temporary solution, inadequate to the scale of the<br />

problem. <strong>The</strong>re’s another image of her, not included here, in a daring emerald dress. <strong>The</strong><br />

whole exercise was originally a shoot for fancy magazine Visionaire. That doesn’t help, either.<br />

<strong>The</strong> hanging speaks of one venerable culture, the dinner of another. <strong>The</strong> retouched babe in<br />

between doesn’t speak – fantasies don’t – but her silence is infinitely troubling.<br />

<strong>Ethridge</strong> comprehends greed, of all kinds. His still life of rotting fruit is so luscious it switches<br />

off atavistic alarms: you want to stroke the mouldy strawberries, lick the superannuated<br />

nectarine. His flawless images laugh at our obsession with perfection, and this flawed<br />

exhibition, in its unforgivingly cavernous temporary home, echoes with that amusement.<br />

Verdict <strong>Ethridge</strong> for President.

Nina Caplan: <strong>Roe</strong> <strong>Ethridge</strong>, Time Out, London, November 15, 2010. <br />

<strong>Roe</strong> <strong>Ethridge</strong> <br />

Until Wed Dec 22 <strong>Greengrassi</strong>, 1A Kempsford Rd, London, SE11 4NU <br />

<strong>Roe</strong> <strong>Ethridge</strong>, '4th Floor', 2008 -‐ <strong>Greengrassi</strong> <br />

Time Out says<br />

In 2005, Goldman Sachs commissioned <strong>Roe</strong> <strong>Ethridge</strong> to photograph its new headquarters near Ground<br />

Zero, which opened in 2009. He finished last month, so it seems safe to assume the three images here<br />

are a very small proportion of his overall haul. But that's appropriate, since <strong>Ethridge</strong>'s images are often<br />

more about what he isn't photographing than what he is.<br />

So, these large-format shots of the pre-operational trade floor are all floor - dusty and footprint-pocked<br />

- and no trade. <strong>The</strong>re's no reference to 9/11 or the financial crisis or to the horrific on-site accident in<br />

2007 when a nylon sling broke and dumped seven tonnes of metal, seriously injuring an architect.<br />

Except, maybe there is. Dust is, after all, a mightily flexible substance: look long enough at these<br />

images and you'll start to see the white dust of the Twin Towers, the dust that signifies construction<br />

(and destruction) and the metaphorical dust that our financial institutions' reputations have become.<br />

<strong>The</strong>re are oddly assorted other images here (including some unpleasant glossy advertising pictures of a<br />

perky-nippled pubescent model in the shower) and a set of shelves. <strong>The</strong>re are geometrically beautiful<br />

pictures of some house <strong>Ethridge</strong> liked somewhere. But it's the '4th Floor' series that stays with you - an<br />

almost textured loveliness, the prints without feet, the tyre treads with no wheels. <strong>Ethridge</strong> should have<br />

called the exhibition Ozymandias, after Shelley's overweening monarch; certainly, given the current<br />

state of the Western world, it is easy to look on these works and despair.

Amoreen Armetta: <strong>Roe</strong> <strong>Ethridge</strong>. Frieze, London, Sept 23, 2008. <br />

<br />

<strong>Roe</strong> <strong>Ethridge</strong> <br />

09.04.08-‐10.04.08 Andrew Kreps Gallery <br />

In <strong>Roe</strong> <strong>Ethridge</strong>’s photograph Oysters, 2008, six gleaming bivalves are arranged <br />

on a crisp bed of sea salt that has been poured onto a sturdy white plate resting <br />

on a rustic wooden table. <strong>The</strong> composition is bathed in sunlight. Initially <br />

seductive, on second glance one discovers this is not a great photograph: <strong>The</strong> <br />

shadows are a bit harsh, the angle is awkward, and the framing is skewed. In no <br />

time at all, the viewer no longer really desires these oysters. Similarly, in Myla <br />

with Column, 2008, what at first glance seems to be a classical nude turns out to <br />

be just odd. Not Vice-‐magazine odd, but still too knowing to be earnest and too <br />

well crafted to be amateur. <strong>The</strong> shadows are harsh again, the neo-‐geo ’80s <br />

backdrop—complete with Roman column—comes off as neither ironic nor <br />

funny, and the lighting and color palette are reminiscent of ’40s pinups. This is <br />

an aesthetic pioneered by Paul Outerbridge, one of <strong>Ethridge</strong>’s primary <br />

influences, who presciently opted for color photography in the ’30s and fused (as <br />

<strong>Ethridge</strong> does) a commercial and fine-‐art aesthetic until his increasingly <br />

fetishistic nudes got him into trouble. <strong>Ethridge</strong> dials up Outerbridge’s stylistic <br />

oddities; in this exhibition, single images are more complex than those in his <br />

previous series, and they rely less on adjacent works for meaning. Each <br />

photograph leads viewers through a gamut of reactions. Because seduction isn’t <br />

his only aim, <strong>Ethridge</strong>’s images, which are not so many things they are frequently <br />

made out to be (Lynchian, or banal, or mere documentation of an artist’s <br />

decadent lifestyle), seduce.

Issue 97 March 2006<br />

<strong>Roe</strong> <strong>Ethridge</strong><br />

Andrew Kreps Gallery, New York, USA<br />

Photography is all about arbitrary borders, about the illusion of self-containment and completeness. We<br />

want to believe that we’ve got the whole picture. In his large-format photographs of often exorbitantly<br />

bland subjects, <strong>Roe</strong> <strong>Ethridge</strong> undermines that very certitude. A pine tree, a watermelon, suburban<br />

signage, a few portraits – the work appears to be little more than the erratic product of an unsettled,<br />

expansive attention. Yet taken together in his various series (this show featured selections from two) or<br />

looked at generally, <strong>Ethridge</strong>’s groupings allow his images to bounce off each other, their cumulative<br />

effect suggestive rather than illustrative of his fundamental inquiry into our ready assumption that<br />

photography will tell us something true.<br />

‘County Line Plus Town and Country’ was a selection from two recent series, the C-type prints unified<br />

by their exploration of various borders and boundaries, imaginary and real. In Hedge, Miami (2004) the<br />

surface is dominated by the rust and dried jalapeno-coloured leaves of a hedge, its function revealed in<br />

the lower left corner, where a tiny bit of brick pavement peeks out. That small revelation converts what<br />

is almost an abstract colour and shape study into a baneful, eerie creature. A similarly apparently<br />

benign but actually quite sinister image is Canada (near Banff) (2005), a snowy, wooded pastoral<br />

traversed by a stream. <strong>The</strong> natural border is completely overpowered by the bristling remains of a

forest devastated by logging. Dense clusters contrast with more sparsely flecked areas, and from a few<br />

feet away the photograph has the erratic profile of a denial-filled polygraph session.<br />

Other kinds of separations are indicated by images of commercial mini-mall signs. Borrowing from the<br />

former Main Street idea of wooden shingles, the individual strip-mall residents list themselves on one<br />

big roadside billboard. <strong>The</strong> odd juxtapositions – a nail salon, an off-track betting joint, a kosher diner, a<br />

pizza parlour, a launderette and video game shop – are offered up for view with editorializing or<br />

judgement in Cedarhurst Mall Sign (2004). <strong>The</strong>y are facts of suburban American life, obviously<br />

peculiar when extracted from their usual surroundings. <strong>Ethridge</strong> shoots the signs at an angle,<br />

emphasizing letter shapes and colour choices, the eccentric line-ups supplying their own commentary;<br />

liquor stores and weight-loss centres dominate. <strong>The</strong> particular economic moment of such signage<br />

stands in contrast to Town and Country, Liberty, New York (2005), which shows a dilapidated<br />

bungalow-style store in a bedraggled corner of upstate New York, with the words ‘Town and Country’,<br />

aspiring to some upscale respectability, scripted across its rust-coloured façade. A young black kid sits<br />

on the bench outside, and the image is bisected by a telephone pole bristling with American flags.<br />

Alongside the exuberant strip-mall signs, the once aspirational, now passé script is like a young man<br />

grown old.<br />

Clearly referencing Thomas Ruff, the Bechers and especially Chris Williams, <strong>Ethridge</strong> also shows<br />

unexpected painterly influences, particularly in his portraits. Holly at Marlow and Sons (2005) is like a<br />

merging of a Madonna by Sandro Botticelli (in the tilt of the head, a gesture at once contemplative and<br />

judging) and Jean-Luc Godard (the young woman an echo of Anna Karina, in her impenetrable,<br />

futuristic black and white turtleneck) – in itself no mean feat. <strong>The</strong> blue-filtered Mary Beth Holcomb<br />

(2005), with her downcast eyes and almost surreally truncated arm, could be a modern-day cousin to<br />

Jan Vermeer’s women. Most unsettling and effective is the seemingly drab Rick Holcomb (2005). <strong>The</strong><br />

microscopically close image – you can actually see his contact lenses – shows a man with a squarish,<br />

stubbled face, a sideward glance and open mouth approaching a smirk, as though he’s hatching some<br />

plan. With the face slightly shadowed against a completely neutral grey background, <strong>Ethridge</strong> achieves<br />

something close to a Caravaggian sense of emotional betrayal in what is essentially a head shot.<br />

Paul Outerbridge is the steady backbeat to <strong>Ethridge</strong>’s work. Like Outerbridge, <strong>Ethridge</strong> incorporates<br />

the ridiculous and the sublime, ignoring the artificial conceits that divide photography into fine art and<br />

commercial work, embracing whatever will further his investigation into the singularity of the<br />

commonplace. <strong>Ethridge</strong> assumes a certain sophistication of his viewer, born of familiarity with the<br />

conventions of editorial photography. By showing tableaux of determined ordinariness, <strong>Ethridge</strong><br />

manages to convey the much larger context from which these are suggestive rather than definitive<br />

extracts. <strong>The</strong> approach is playful, with a humour that mercifully softens the bleakness: what could be<br />

merely reportage becomes.<br />

Megan Ratner