Dams in River Systems - Warner College of Natural Resources ...

Dams in River Systems - Warner College of Natural Resources ...

Dams in River Systems - Warner College of Natural Resources ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

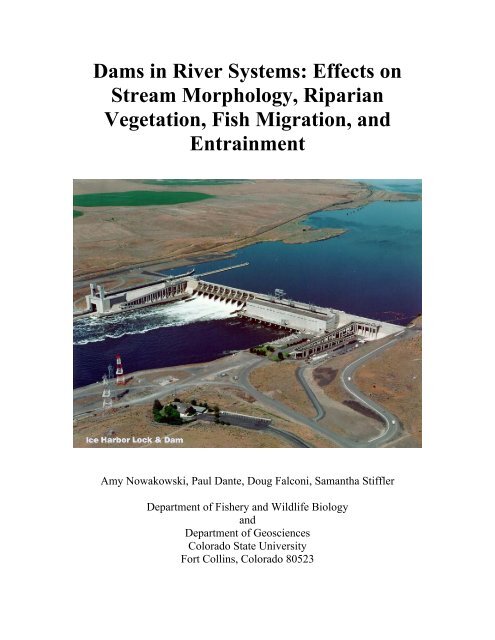

<strong>Dams</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>River</strong> <strong>Systems</strong>: Effects on<br />

Stream Morphology, Riparian<br />

Vegetation, Fish Migration, and<br />

Entra<strong>in</strong>ment<br />

Amy Nowakowski, Paul Dante, Doug Falconi, Samantha Stiffler<br />

Department <strong>of</strong> Fishery and Wildlife Biology<br />

and<br />

Department <strong>of</strong> Geosciences<br />

Colorado State University<br />

Fort Coll<strong>in</strong>s, Colorado 80523

Abstract.−<strong>Dams</strong> have harmful effects on<br />

river systems, because they disrupt<br />

stream morphology, riparian vegetation,<br />

fish migration, and cause fish<br />

entra<strong>in</strong>ment. <strong>Dams</strong> generate water<br />

temperature changes, reduce sediment<br />

transport, and alter flow regimes with<strong>in</strong><br />

a river system. Changes <strong>in</strong> flow regimes<br />

have adverse affects on native riparian<br />

vegetation recruitment. <strong>Dams</strong> deny fish<br />

access to critical upstream habitats, and<br />

have the potential to cause fish<br />

entra<strong>in</strong>ment. Multiple consequences are<br />

associated with entra<strong>in</strong>ment, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g<br />

isolation <strong>of</strong> populations, prevent<strong>in</strong>g<br />

genetic exchange, block<strong>in</strong>g access to<br />

essential habitat, <strong>in</strong>jury, loss <strong>of</strong><br />

recruitment, potential <strong>in</strong>creased<br />

hybridization, and both direct and<br />

<strong>in</strong>direct mortality.<br />

<strong>Dams</strong> are <strong>in</strong>timately tied to river<br />

systems <strong>in</strong> North America, with<br />

approximately 79,000 dams currently<br />

exist<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the United States (ASCE<br />

2005). Water storage, flood prevention,<br />

hydropower generation, irrigation,<br />

<strong>in</strong>dustrial use, and recreation are touted<br />

as benefits to dam construction.<br />

Unfortunately, most dams were built<br />

before research <strong>of</strong> the potential negative<br />

effects was <strong>in</strong>itiated. The goal <strong>of</strong> this<br />

paper is to assess disruptions <strong>in</strong> aquatic<br />

and riparian habitats caused by dams.<br />

Disruptions <strong>in</strong>clude changes <strong>in</strong> abiotic<br />

factors, such as water temperature,<br />

sediment transport, and flow regime.<br />

Biotic factors, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g riparian<br />

vegetation recruitment, fish migration,<br />

and fish entra<strong>in</strong>ment, are also negatively<br />

<strong>in</strong>fluenced by dam constra<strong>in</strong>ts.<br />

Colorado pikem<strong>in</strong>now. Photo by Falconi. 2005.<br />

<strong>Dams</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>River</strong> <strong>Systems</strong>: Abiotic<br />

Factors and Stream Morphology<br />

by Amy Nowakowski<br />

The occurrence <strong>of</strong> dams <strong>in</strong> river<br />

systems has been widely studied to<br />

identify the relationships between dams,<br />

stream morphology, and the function <strong>of</strong><br />

aquatic and riparian ecosystems (Baxter<br />

1977; P<strong>of</strong>f et al. 1997; Graff 1999). The<br />

goal <strong>of</strong> this paper is to explore<br />

correlations between dams, water<br />

quality, sediment transport, flow regime,<br />

and the result<strong>in</strong>g disruptions <strong>of</strong> the river<br />

ecosystem. It is imperative to understand<br />

how dams affect the natural processes <strong>of</strong><br />

river systems so watershed managers can<br />

strive to ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong> ecosystem <strong>in</strong>tegrity<br />

while fulfill<strong>in</strong>g management activities<br />

(Hart and P<strong>of</strong>f 2002).<br />

<strong>Dams</strong> change aquatic habitat by<br />

alter<strong>in</strong>g water temperatures. Deep water<br />

stored beh<strong>in</strong>d a dam becomes stratified<br />

<strong>in</strong>to layers <strong>of</strong> differ<strong>in</strong>g temperatures<br />

(P<strong>of</strong>f and Hart 2002). When water is<br />

released from the dam, the cold<br />

hypolimnion layer flows downstream<br />

(American <strong>River</strong>s 2002). Aquatic<br />

species can reproduce, grow, and survive<br />

only with<strong>in</strong> a particular range <strong>of</strong><br />

temperatures (Kendeigh 1961). Changes<br />

<strong>in</strong> water temperature can lead to a shift<br />

<strong>in</strong> species composition or density, if<br />

<strong>in</strong>vad<strong>in</strong>g species overtake native species<br />

due to their higher range <strong>of</strong><br />

environmental tolerances (P<strong>of</strong>f and Hart<br />

2002).<br />

Sediment transport through a river<br />

system is also greatly affected by dams.<br />

Most sediment enter<strong>in</strong>g a reservoir is<br />

stored beh<strong>in</strong>d dams, result<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong><br />

sediment-starved conditions downstream<br />

(Graf 2002). This creates the potential<br />

for channel <strong>in</strong>cision, bank erosion,<br />

change <strong>in</strong> channel planform, and<br />

development <strong>of</strong> a coarse armor layer on<br />

the streambed as f<strong>in</strong>e sediments wash

downstream (Knighton 1998; Graf 2002;<br />

Pizzuto 2002). A river system with a<br />

conf<strong>in</strong>ed sediment flow <strong>of</strong>ten has<br />

reduced habitat diversity due to the<br />

decreased nutrient flux and loss <strong>of</strong><br />

habitat (American <strong>River</strong>s 2002; Graf<br />

2002).<br />

The flow regime is a fundamental<br />

variable <strong>in</strong> the river ecosystem which is<br />

significantly disrupted by dams, thereby<br />

alter<strong>in</strong>g ecological <strong>in</strong>tegrity (Figure 1).<br />

Flow regimes provide the stream<br />

environment with naturally vary<strong>in</strong>g<br />

fluxes <strong>of</strong> both water and sediment,<br />

which def<strong>in</strong>e the stream morphology and<br />

the function <strong>of</strong> the stream ecosystem<br />

(P<strong>of</strong>f et al. 1997). In a natural river<br />

system, the diversity <strong>of</strong> flow conditions<br />

provide habitat for aquatic species<br />

(Newberry 1995), and riparian species<br />

dependent upon overbank floods (P<strong>of</strong>f<br />

and Hart 2002; American <strong>River</strong>s 2002).<br />

<strong>Dams</strong> constra<strong>in</strong> a river’s flow regime by<br />

stor<strong>in</strong>g water <strong>in</strong> reservoirs, limit<strong>in</strong>g<br />

overbank floods, and regulat<strong>in</strong>g and<br />

m<strong>in</strong>imiz<strong>in</strong>g the magnitude, frequency,<br />

duration, and tim<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> natural flows<br />

(Baxter 1977; P<strong>of</strong>f et al. 1997; P<strong>of</strong>f and<br />

Hart 2002). Consequently, the food web<br />

and productivity <strong>of</strong> species adapted to<br />

dynamic flow conditions is considerably<br />

modified by dams (P<strong>of</strong>f and Hart 2002).<br />

Figure 1.─Flow regime is <strong>of</strong> central importance <strong>in</strong> susta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g the ecological <strong>in</strong>tegrity <strong>of</strong> flow<strong>in</strong>g water<br />

systems. The five components <strong>of</strong> the flow regime–magnitude, frequency, duration, tim<strong>in</strong>g, and rate <strong>of</strong><br />

change–<strong>in</strong>fluence <strong>in</strong>tegrity both directly and <strong>in</strong>directly, through their effects on other primary regulators <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong>tegrity. Modification <strong>of</strong> flow thus has cascad<strong>in</strong>g effects on the ecological <strong>in</strong>tegrity <strong>of</strong> rivers (from P<strong>of</strong>f et<br />

al. 1997; after Karr 1991).<br />

Although dam removal is a<br />

management option that can potentially<br />

reverse the morphological and ecological<br />

disruptions discussed above, little is<br />

known about the response <strong>of</strong> rivers to<br />

dam removal (P<strong>of</strong>f and Hart 2002;<br />

Stanley 2002; Doyle 2005; Santucci<br />

2005). Hart et al. (2002) provides a<br />

simple representation <strong>of</strong> the potential<br />

abiotic and biotic responses to dam<br />

removal (Figure 2). The potential<br />

responses to dam removal are time<br />

dependent, and may take days to several<br />

decades to respond. Therefore, it is a<br />

great challenge to predict the ecosystem<br />

response occurr<strong>in</strong>g after dam removal,<br />

because river ecosystems <strong>in</strong>volve a<br />

complexity <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>teractions over a<br />

multitude <strong>of</strong> spatial and temporal scales<br />

(Hart et al. 2002).

Figure 2.─A simple spatial and temporal context for exam<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g potential ecological responses to dam<br />

removal. Prior to removal, upstream and downstream free-flow<strong>in</strong>g areas are separated by an impoundment.<br />

Dam removal <strong>in</strong>itiates a series <strong>of</strong> abiotic and biotic changes that vary among areas and occur at different<br />

rates. For example, the rate <strong>of</strong> sediment transport and channel adjustment is a function <strong>of</strong> the distribution <strong>of</strong><br />

sediment particle sizes and flow magnitudes, and the response rate <strong>of</strong> aquatic and riparian biota to these<br />

changes depends on their dispersal and growth rates. Key changes occurr<strong>in</strong>g with<strong>in</strong> each spatial and<br />

temporal area have been highlighted. For some processes, arrows <strong>in</strong>dicate net change as either <strong>in</strong>crease<br />

( ↑ ) or decreases ( ↓ ), though <strong>in</strong> other cases the change may be <strong>in</strong> either direction ( ↑↓) (from Hart et al.<br />

2002).<br />

Riparian Response to Upstream Dam<br />

Creation<br />

by Paul Dante<br />

Riparian zones are a vital l<strong>in</strong>k to our<br />

river systems, be<strong>in</strong>g described by<br />

Naiman and Décamps (1997) as “some<br />

<strong>of</strong> the most diverse, dynamic, and<br />

complex biophysical habitats on the<br />

terrestrial portion <strong>of</strong> the planet.” Most<br />

<strong>of</strong> the research <strong>in</strong>to the effects <strong>of</strong> dams<br />

on riparian zones has occurred only<br />

with<strong>in</strong> the last two decades; however<br />

they are still <strong>of</strong>ten overlooked by the<br />

government, as well as the public. As<br />

approximately 79,000 dams are <strong>in</strong> the<br />

U.S. National Inventory <strong>of</strong> <strong>Dams</strong> (ASCE<br />

2005), any degradation or destruction <strong>of</strong><br />

riparian zones will cont<strong>in</strong>ue to be a<br />

problem <strong>in</strong> the United States for a long<br />

time to come. In this paper I will discuss<br />

the importance <strong>of</strong> riparian zones and<br />

describe some <strong>of</strong> the negative effects <strong>of</strong><br />

river regulation on these zones.<br />

Riparian corridors (or riparian zones),<br />

are the <strong>in</strong>terface between terrestrial and<br />

aquatic systems described by Lowrence<br />

et al. (1985, <strong>in</strong> Wenger 1999) as “the<br />

complex assemblage <strong>of</strong> organisms and<br />

their environment exist<strong>in</strong>g adjacent to<br />

and near flow<strong>in</strong>g water.” Naiman et al.<br />

(1993) ref<strong>in</strong>ed the def<strong>in</strong>ition to be the<br />

area between the low water marks and<br />

any areas above the high water mark<br />

affected by the heightened water table or<br />

regular flood<strong>in</strong>g, as well as “the ability<br />

<strong>of</strong> the soils to hold water”. Along with<br />

the trapp<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> sediment and pollutants,

iparian zones moderate water<br />

temperature, mitigate bank erosion and<br />

attenuate peak flows (Leavitt 1998;<br />

Wenger 1999). These attributes stabilize<br />

the ecology conditions <strong>of</strong> the stream, as<br />

well as help ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong> water quality for<br />

human and <strong>in</strong>dustrial use.<br />

Dam systems degradate riparian<br />

corridors for multiple reasons. <strong>Dams</strong><br />

fragment rivers by alter<strong>in</strong>g flow patterns,<br />

limit<strong>in</strong>g downstream movement <strong>of</strong><br />

sediment, and upstream and downstream<br />

movement biological material. Guppy<br />

(1906 <strong>in</strong> Merritt and Wohl 2006) and<br />

McAtee (1925 <strong>in</strong> Merritt and Wohl<br />

2006) noted the importance <strong>of</strong> plant<br />

hydrochory (dispersal by water) for<br />

riparian ecosystem health. Andersson et<br />

al. (2000) and Merritt and Wohl (2002)<br />

found that dam fragmentation <strong>of</strong> rivers<br />

blocks transport, decreas<strong>in</strong>g the<br />

effectiveness <strong>of</strong> hydrochory <strong>of</strong> the seeds<br />

and other vegetative propagules.<br />

Bradley and Smith (1986) found that<br />

cottonwood (Populus sp.) seed dispersal,<br />

which is timed around natural peak<br />

floods, had decreased effectiveness<br />

under regulated flow that altered peak<br />

tim<strong>in</strong>g. Merritt and Cooper (2000)<br />

found that the spr<strong>in</strong>g flood peak <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Green <strong>River</strong> <strong>of</strong> northwest Colorado was<br />

completely removed by river regulation,<br />

and as a result, riparian Populus<br />

recruitment has been elim<strong>in</strong>ated.<br />

Riparian vegetation (Al-Kaisi 2000).<br />

Along with removal <strong>of</strong> peak flow,<br />

related changes <strong>in</strong> the water table may<br />

affect riparian health. Dur<strong>in</strong>g the 37<br />

years after the <strong>in</strong>troduction <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Flam<strong>in</strong>g Gorge dam on the Green <strong>River</strong>,<br />

there was a transition <strong>in</strong> riparian<br />

vegetation that seems to <strong>in</strong>dicate a shift<br />

to shrublands from Populus, and an<br />

<strong>in</strong>crease <strong>of</strong> fluvial marshes (Merritt and<br />

Cooper 2000) (Figure 1). This may<br />

<strong>in</strong>dicate a change <strong>in</strong> available water.<br />

Riparian cottonwood and willow (Salix<br />

sp.) dependence on shallow alluvial<br />

groundwater make them extremely<br />

susceptible to water table changes<br />

(Aml<strong>in</strong> and Rood 2002; Rood et al.<br />

2003). Reduction <strong>in</strong> water table height<br />

can be lethal to seedl<strong>in</strong>gs, and thus limit<br />

or prevent recruitment <strong>of</strong> new trees<br />

(Rood and Mahoney 1990; Segelquist et<br />

al. 1993).<br />

Until regulated rivers are allowed to<br />

return to more natural flow patterns,<br />

riparian zones <strong>in</strong> the United States will<br />

cont<strong>in</strong>ue to degrade, and with them the<br />

ecological health <strong>of</strong> these river. That is<br />

why it is important for research to<br />

cont<strong>in</strong>ue to delve <strong>in</strong>to the requirements<br />

<strong>of</strong> riparian zones and for local, state, and<br />

federal governmental agencies to take<br />

this <strong>in</strong>formation <strong>in</strong>to account when<br />

establish<strong>in</strong>g flow regulation.

Figure 1.─Model <strong>of</strong> channel response to flow regulation on the Green <strong>River</strong> <strong>in</strong> Browns Park from 1938<br />

through the present, <strong>in</strong>ferred from planform geometry. Frame (a) shows the pre-dam quasi-equilibrium<br />

meander<strong>in</strong>g channel prior to regulation. Stage I: frame (b) shows the short-term (1966–1977) narrow<strong>in</strong>g<br />

response <strong>of</strong> the channel to reduced flow; note the establishment <strong>of</strong> vegetation <strong>in</strong> the formerly active<br />

channel. Stage II and III: frames (c) and (d) illustrate the longer-term (1977–1994) channel response, which<br />

<strong>in</strong>cludes the development <strong>of</strong> bars, the stabilization <strong>of</strong> bars to form islands, and the cont<strong>in</strong>ued widen<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong><br />

the channel. Frame (e) is the hypothetical long-term form <strong>of</strong> the channel after several more decades <strong>of</strong><br />

widen<strong>in</strong>g, the coalescence <strong>of</strong> islands through channel <strong>in</strong>fill<strong>in</strong>g, and formation <strong>of</strong> a meander<strong>in</strong>g channel<br />

with<strong>in</strong> the newly formed floodpla<strong>in</strong> nested with<strong>in</strong> the high banks <strong>of</strong> the former floodpla<strong>in</strong>. (from Merritt<br />

and Cooper 2000).

Instream Barriers: Prevent<strong>in</strong>g Fishes<br />

From Access<strong>in</strong>g Upstream Habitats<br />

by Douglas A. Falconi<br />

The most important effect <strong>of</strong> all<br />

<strong>in</strong>stream barriers is to prevent upstream<br />

movement <strong>of</strong> fishes (Baxter 1977).<br />

Instream barriers have had the most<br />

noticeable impact on diadromous fishes<br />

(Table 1; Leggett 1977; P<strong>of</strong>f et al. 1997).<br />

However, many river<strong>in</strong>e fishes that were<br />

once considered to be residents have<br />

now been observed to require many<br />

kilometers <strong>of</strong> unobstructed stream to<br />

fulfill their life cycle (W<strong>in</strong>ston et al.<br />

1991; Gowan et al. 1994; Gowan and<br />

Fausch 1996; Fausch et al. 2002).<br />

Although fish passageways have been<br />

implemented at some dams to restore<br />

partial connectivity, they may not be<br />

adequate for all species to access<br />

upstream habitat (Clay 1995; Beasley<br />

and Hightower 2000; Moser et al. 2000).<br />

Only removal <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>stream barriers will<br />

restore connectivity.<br />

Table 1.─Some common diadromous fishes <strong>of</strong> North America that are impeded by <strong>in</strong>stream barriers and<br />

native occurrence (modified from Lucas and Baras 2001).<br />

Species<br />

Common Name Scientific Name<br />

Atlantic or<br />

Pacific<br />

Atlantic sea lamprey Petromyzon mar<strong>in</strong>us Atlantic<br />

Arcitic lamprey Petromyzon japonica Pacific<br />

American Atlantic sturgeon Acipenser oxyr<strong>in</strong>chus Atlantic<br />

shortnose sturgeon Acipenser brevirostrum Atlantic<br />

alewife Alosa psuedoharengus Atlantic<br />

blueback herr<strong>in</strong>g Alosa aestivalis Atlantic<br />

American shad Alosa sapidissima Atlantic<br />

delta smelt Hypomesus transpacificus Pacific<br />

ch<strong>in</strong>ook salmon Oncorhynchus tshawytscha Pacific<br />

Atlantic salmon Salmo salar Atlantic<br />

coho salmon Oncorhynchus kisutch Pacific<br />

chum salmon Oncorhynchus keta Pacific<br />

p<strong>in</strong>k salmon Oncorhynchus gorbuscha Pacific<br />

striped bass Morone saxatilis Atlantic<br />

white perch Morone americana Atlantic<br />

On the East Coast, the presence <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong>stream barriers has prevented<br />

American shad Alosa sapidissima from<br />

access<strong>in</strong>g natal spawn<strong>in</strong>g sites (Rohde et<br />

al. 1994; Beasley and Hightower 2000).<br />

Beasley and Hightower (2000) observed<br />

striped bass Morone saxatilis us<strong>in</strong>g the<br />

denil passageway at the Quaker Neck<br />

Dam, but American shad rema<strong>in</strong>ed at the<br />

base <strong>of</strong> the dam. When the Quaker Neck<br />

Dam was removed <strong>in</strong> 1998, both striped<br />

bass and American shad were observed<br />

spawn<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> upstream habitats (Beasley<br />

and Hightower 2000). For passageway<br />

design, fish lifts have been most<br />

successful for American shad (Barry and<br />

Kynard 1986; Spankle 2005). The Essex<br />

Dam fish lifts on the Merrimack <strong>River</strong> <strong>in</strong><br />

Massachusetts passed 5,283 American<br />

shad, or 10% <strong>of</strong> the run, <strong>in</strong> 2002<br />

(Spankle 2005). A common means <strong>of</strong><br />

passage for American shad on East<br />

Coast rivers has been the use <strong>of</strong>

navigation locks (Moser et al. 2000;<br />

Bailey et al. 2004). For example, on the<br />

Cape Fear <strong>River</strong> <strong>in</strong> North Carol<strong>in</strong>a, 3 <strong>of</strong><br />

66 (4.5%) radio-tagged American shad<br />

used the denil passageway, whereas 28<br />

out <strong>of</strong> 66 (42%) passed upstream us<strong>in</strong>g<br />

the navigation lock (Moser et al. 2000).<br />

Bailey et al. (2004) observed that 50% <strong>of</strong><br />

the American shad that returned to the<br />

New Savannah Bluff Lock and Dam on<br />

the Savannah <strong>River</strong> <strong>in</strong> Georgia also<br />

passed upstream us<strong>in</strong>g the navigation<br />

lock.<br />

The effects <strong>of</strong> diversion dams and<br />

<strong>in</strong>stream barriers are not limited to<br />

diadromous fishes. Many <strong>in</strong>land fishes<br />

have also been severely impacted. In the<br />

Colorado <strong>River</strong> Bas<strong>in</strong>, <strong>in</strong>stream barriers<br />

are a ma<strong>in</strong> cause for the decl<strong>in</strong>e <strong>of</strong><br />

Colorado pikem<strong>in</strong>now, Ptychocheilus<br />

lucius (M<strong>in</strong>ckley 1973; Tyus 1986).<br />

White <strong>River</strong> resident Colorado<br />

pikem<strong>in</strong>now migrate over 600 km <strong>in</strong> the<br />

Green <strong>River</strong> Bas<strong>in</strong> to one <strong>of</strong> two<br />

spawn<strong>in</strong>g areas year after year (Tyus and<br />

McAda 1984; Tyus 1986, 1990; Irv<strong>in</strong>g<br />

and Modde 2000). Instream barriers, like<br />

the Taylor Draw Dam on the White<br />

<strong>River</strong>, prevent <strong>in</strong>dividuals from<br />

access<strong>in</strong>g potential spawn<strong>in</strong>g areas and<br />

w<strong>in</strong>ter<strong>in</strong>g habitat (Tyus 1986; Burdick<br />

1995; Irv<strong>in</strong>g and Modde 2000).<br />

Construct<strong>in</strong>g passageways may be a<br />

viable recovery option for this species.<br />

Burdick (2001) observed several subadult<br />

and adult Colorado pikem<strong>in</strong>now<br />

use a newly constructed vertical slot<br />

passageway at the Redlands Diversion<br />

Dam on the Gunnison <strong>River</strong> near Grand<br />

Junction, Colorado.<br />

Clearly, <strong>in</strong>stream barriers have<br />

negative effects on the native<br />

ichthy<strong>of</strong>auna <strong>of</strong> streams by prevent<strong>in</strong>g<br />

upstream access to spawn<strong>in</strong>g sites and<br />

w<strong>in</strong>ter<strong>in</strong>g habitats (Tyus 1986, 1990;<br />

Beasley and Hightower 2000; Irv<strong>in</strong>g and<br />

Modde 2000). Install<strong>in</strong>g passageways<br />

may help some species to use historic<br />

habitat, but the efficiency <strong>of</strong> a<br />

passageway is very difficult to calculate,<br />

so the degree <strong>of</strong> success <strong>of</strong>ten rema<strong>in</strong>s<br />

uncerta<strong>in</strong> (Clay 1995). Only complete<br />

removal will ensure that all species are<br />

able to freely migrate upstream.<br />

Salmon attempt migration over <strong>in</strong>stream barrier<br />

(LCS 2001).<br />

Environmental Effects and Potential<br />

Consequences <strong>of</strong> Fish Entra<strong>in</strong>ment<br />

by Samantha Stiffler<br />

Entra<strong>in</strong>ment <strong>of</strong> fish at power plant<br />

and other water <strong>in</strong>takes has the potential<br />

to adversely affect fish populations.<br />

Jude et al. (1986, <strong>in</strong> Savitz et al. 1998)<br />

described entra<strong>in</strong>ment as the process <strong>of</strong><br />

an organism pass<strong>in</strong>g through a plant and<br />

be<strong>in</strong>g discharged back <strong>in</strong>to the<br />

environment. Multiple consequences are<br />

associated with entra<strong>in</strong>ment: isolation <strong>of</strong><br />

populations, prevent<strong>in</strong>g genetic

exchange, block<strong>in</strong>g access to essential<br />

habitat, <strong>in</strong>jury, loss <strong>of</strong> recruitment,<br />

potential <strong>in</strong>creased hybridization, and<br />

both direct and <strong>in</strong>direct mortality<br />

(USFWS 2001).<br />

Degree <strong>of</strong> impacts on populations<br />

depends on fish species and <strong>in</strong>take<br />

characteristics. Species specific effects<br />

depend on: motility; physiological and<br />

behavioral responses; vertical and<br />

horizontal distribution <strong>in</strong> vic<strong>in</strong>ity to the<br />

<strong>in</strong>take, and growth rate, which<br />

determ<strong>in</strong>es the period <strong>of</strong> vulnerability to<br />

entra<strong>in</strong>ment. Intake characteristics<br />

<strong>in</strong>clude: location and construction<br />

details, which control flow conditions <strong>in</strong><br />

the immediate vic<strong>in</strong>ity <strong>of</strong> the <strong>in</strong>take; size<br />

<strong>of</strong> structure; discharge volume; type <strong>of</strong><br />

release; and depth <strong>of</strong> turb<strong>in</strong>es (Boreman<br />

1977; Travnichek et al. 1993).<br />

Multiple studies have shown that the<br />

majority <strong>of</strong> organisms entra<strong>in</strong>ed are<br />

young-<strong>of</strong>-year or juveniles (Gray et al.<br />

1986; Jaeger et al. 2005; New York<br />

Power Authority 2005). Larval drift<br />

obta<strong>in</strong>s a maximum peak dur<strong>in</strong>g the<br />

early days or weeks <strong>of</strong> life, and primarily<br />

occurs at night, with a maximum shortly<br />

after dusk (Figure 1), and <strong>in</strong> some cases,<br />

close to dawn (Carter and Reader 2000).<br />

Determ<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g the number <strong>of</strong> fish<br />

entra<strong>in</strong>ed is difficult; to determ<strong>in</strong>e<br />

percent loss, the average concentration<br />

<strong>of</strong> organisms <strong>in</strong> the water, mortality <strong>of</strong><br />

entra<strong>in</strong>ed organisms, and period <strong>of</strong><br />

vulnerability to entra<strong>in</strong>ment must be<br />

taken <strong>in</strong>to account (Boreman 1977). The<br />

effect on larvae entra<strong>in</strong>ed is also<br />

particularly difficult to determ<strong>in</strong>e<br />

because larvae abundance, mortality, and<br />

growth are difficult to estimate (Jensen<br />

1990).<br />

Figure 1.─Diel Variation <strong>in</strong> (a) entra<strong>in</strong>ment and (b) drift <strong>of</strong> 0+ fish, on two dates, <strong>in</strong> the <strong>River</strong> Trent,<br />

England. (BST = British Summer Time; from Carter and Reader 2000).

Legislation <strong>in</strong>volved with<br />

entra<strong>in</strong>ment <strong>in</strong>volves state and federal<br />

requirements. Under section 316(b) <strong>of</strong><br />

the Clean Water Act, cool<strong>in</strong>g water<br />

<strong>in</strong>take structures are required to reflect<br />

the best technology available for<br />

m<strong>in</strong>imiz<strong>in</strong>g adverse environmental<br />

impacts (W<strong>in</strong>kle and Kadvany 2003).<br />

This section evaluates water <strong>in</strong>takes and<br />

documents permits after the evaluation is<br />

approved (Ed<strong>in</strong>ger and Kolluru 2000).<br />

In addition to state requirements, the<br />

National Oceanic and Atmospheric<br />

Adm<strong>in</strong>istration Fisheries and the US<br />

Fish and Wildlife Service <strong>of</strong>ten require<br />

screen<strong>in</strong>g to protect fish species listed as<br />

threatened or endangered. Justification<br />

for these screen<strong>in</strong>gs result from the<br />

removal <strong>of</strong> threatened or endangered<br />

species by a diversion constitut<strong>in</strong>g<br />

“take” under section 4(d) <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Endangered Species Act (Moyle and<br />

Israel 2005).<br />

Various technologies have been<br />

developed to attempt to reduce<br />

entra<strong>in</strong>ment. These barriers have been<br />

divided <strong>in</strong>to physical and behavioral<br />

barriers. The Federal Energy Regulatory<br />

Commission (1995, <strong>in</strong> New York Power<br />

Authority 2005) report five types <strong>of</strong><br />

physical barriers that have been<br />

deployed at hydroelectric stations: low<br />

velocity fish screens, high velocity fish<br />

screens, close-spaced and angled bar<br />

racks, louvers, and barrier nets.<br />

Behavioral barriers <strong>in</strong>clude: lights, such<br />

as strobe and mercury, which have<br />

variable response rates (McK<strong>in</strong>stry et al.<br />

2005; Johnson et al. 2005), sound, air<br />

bubble curta<strong>in</strong>s, and electrical barriers<br />

(New York Power Authority 2005).<br />

Entra<strong>in</strong>ment can be compared to<br />

natural mortality; if the rate <strong>of</strong><br />

entra<strong>in</strong>ment is small and less than<br />

natural mortality, the impact would not<br />

be appreciably noticeable. However, if<br />

the rate exceeds natural mortality, the<br />

population may not be susta<strong>in</strong>able<br />

(Ed<strong>in</strong>ger and Kolluru 2000).<br />

Percentage <strong>of</strong> entra<strong>in</strong>ment from a s<strong>in</strong>gle<br />

<strong>in</strong>take may be low, but cumulative<br />

impacts could be high (Ed<strong>in</strong>ger and<br />

Kolluru 2000). Population-level<br />

responses may be characterized by a<br />

significant time lag, where effects would<br />

not be seen for many years. In turn,<br />

ecosystem-level effects, such as size and<br />

structure <strong>of</strong> populations, are likely to<br />

become evident with cont<strong>in</strong>ued<br />

population changes caused by<br />

entra<strong>in</strong>ment (Benstead et al. 1999).<br />

Conclusion<br />

One management option that has<br />

potential to mediate the adverse effects<br />

<strong>of</strong> dams <strong>in</strong> river systems is dam removal.<br />

Dam removal can restore aquatic and<br />

riparian habitats by reestablish<strong>in</strong>g the<br />

natural flow regime, allow<strong>in</strong>g fish<br />

migration, and elim<strong>in</strong>at<strong>in</strong>g entra<strong>in</strong>ment<br />

occurrences. However, abiotic and biotic<br />

responses to dam removal are difficult to<br />

predict because complex <strong>in</strong>teractions<br />

occur over different spatial and temporal<br />

scales.<br />

Removal <strong>of</strong> low-head dam on the Ashuelot<br />

<strong>River</strong>, New Hampshire (USFWS 2005).

References<br />

Al-Kaisi, M. 2000. Conservation buffers<br />

and water quality. Integrated Crop<br />

Management. Available:<br />

www.ent.iastate.edu/.../buffer/buffer.<br />

html. (April 2006).<br />

American <strong>River</strong>s. 2002. The ecology <strong>of</strong><br />

dam removal: a summary <strong>of</strong> benefits<br />

and impacts. Available:<br />

http://www.americanrivers.org/site/<br />

DocServer/ ecology<strong>of</strong><br />

damremoval.pdf?docID=494. (March<br />

2006).<br />

Aml<strong>in</strong>, N.M., and S.B. Rood. 2002.<br />

Comparative tolerances <strong>of</strong> riparian<br />

willows and cottonwoods to watertable<br />

decl<strong>in</strong>e. Wetlands 22(2):338–<br />

346.<br />

Andersson, E., C. Nilsson, and M.E.<br />

Johansson. 2000. Effects <strong>of</strong> river<br />

fragmentation on plant dispersal and<br />

riparian flora. Regulated <strong>River</strong>s:<br />

Research and Management 16:83–<br />

89.<br />

[ASCE] American Society <strong>of</strong> Civil<br />

Eng<strong>in</strong>eers. 2005. National<br />

Infrastructure Report Card.<br />

Available:<br />

http://www.asce.org/reportcard/2005<br />

/page.cfm?id=23. (February 2006).<br />

Bailey, M.M., J.J. Isely, and W.C.<br />

Bridges, Jr. 2004. Movement and<br />

population size <strong>of</strong> American shad<br />

near a low-head lock and dam.<br />

Transactions <strong>of</strong> the American<br />

Fisheries Society. 133:300-308.<br />

Barry, T., and B. Kynard. 1986.<br />

Attraction <strong>of</strong> adult American shad to<br />

fish lifts at Holyoke Dam,<br />

Connecticut <strong>River</strong>. North American<br />

Journal <strong>of</strong> Fisheries Management.<br />

6:233-241.<br />

Baxter, R. M. 1977. Environmental<br />

effects <strong>of</strong> dams and impoundments.<br />

Annual Review <strong>of</strong> Ecology and<br />

Systematics 8:255-283.<br />

Beasley, C.A., and J.E. Hightower.<br />

2000. Effects <strong>of</strong> a low-head dam on<br />

the distribution and characteristics <strong>of</strong><br />

spawn<strong>in</strong>g habitat used by striped<br />

bass and American shad.<br />

Transactions <strong>of</strong> the American<br />

Fisheries Society. 129:1316-1330.<br />

Benstead, J.P., J.G. March, C.M.<br />

Pr<strong>in</strong>gle, and F.N. Scatena. 1999.<br />

Effects <strong>of</strong> a low-head dam and water<br />

abstraction on migratory tropical<br />

stream biota. Ecological<br />

Applications 9:656-668.<br />

Boreman, J. 1977. Impacts <strong>of</strong> power<br />

plant <strong>in</strong>take velocities on fish. Fish<br />

and Wildlife Service. US<br />

Department <strong>of</strong> the Interior. Fish and<br />

Wildlife resources and electric power<br />

generation. Report no. 1. Ann<br />

Arbor, Michigan.<br />

Bradley, C.E., and D.G. Smith. 1986.<br />

Pla<strong>in</strong>s cottonwood recruitment and<br />

survival on a prairie meander<strong>in</strong>g<br />

river floodpla<strong>in</strong>, Milk <strong>River</strong>,<br />

southern Alberta and northern<br />

Montana. Canadian Journal <strong>of</strong><br />

Botany 64:1433-1442.<br />

Burdick, B.D. 1995. Ichthy<strong>of</strong>aunal<br />

studies <strong>of</strong> the Gunnison <strong>River</strong>,<br />

Colorado, 1992 -1994. U.S. Fish and<br />

Wildlife Service, Asp<strong>in</strong>all Unit<br />

Umbrella Studies Recovery Program<br />

Project 42, Grand Junction,<br />

Colorado.<br />

Burdick, B.D. 2001. Five-year<br />

evaluation <strong>of</strong> fish passage at the<br />

Redlands Diversion Dam on the<br />

Gunnison <strong>River</strong> near Grand Junction,<br />

Colorado: 1996 – 2000. U.S. Fish<br />

and Wildlife Service, Recovery<br />

Program Project CAP-4b, Grand<br />

Junction, Colorado.

Carter, K.L., and JP Reader. 2000.<br />

Patterns <strong>of</strong> drift and power station<br />

entra<strong>in</strong>ment <strong>of</strong> 0+ fish <strong>in</strong> the <strong>River</strong><br />

Trent, England. Fisheries<br />

Management and Ecology 7:447-<br />

464.<br />

Clay, C.H. 1995. Design <strong>of</strong> fishways and<br />

other fish facilities. Second Edition.<br />

CRC Press, Boca Raton, Florida.<br />

Doyle, M.W., E.H. Stanley, C.H. Orr,<br />

A.R. Selle, S.A. Sethi, and J.M.<br />

Harbor. 2005. Stream ecosystem<br />

response to small dam removal:<br />

lessons from the heartland.<br />

Geomorphology 71:227-244.<br />

Ed<strong>in</strong>ger, J.E., and VS Kolluru. 2000.<br />

Power plant <strong>in</strong>take entra<strong>in</strong>ment<br />

analysis. Journal <strong>of</strong> Energy<br />

Eng<strong>in</strong>eer<strong>in</strong>g 1:1-14.<br />

Fausch, K.D., C.E. Torgersen, C.V.<br />

Baxter, and H.W. Li. 2002. A<br />

cont<strong>in</strong>uous view <strong>of</strong> the river is<br />

needed to understand how processes<br />

<strong>in</strong>teract<strong>in</strong>g among scales set the<br />

context for stream fishes and their<br />

habitat. BioScience. 52:483-498.<br />

Gowan, C., and K.D. Fausch. 1996.<br />

Mobile brook trout <strong>in</strong> two high<br />

elevation Colorado streams: reevaluat<strong>in</strong>g<br />

the concept <strong>of</strong> restricted<br />

movement. Canadian Journal <strong>of</strong><br />

Fisheries and Aquatic Science.<br />

53:1370-1381.<br />

Gowan, C., M.K. Young, K.D. Fausch,<br />

and S.C. Riley. 1994. Restricted<br />

movement <strong>in</strong> resident stream<br />

salmonids: a paradigm lost?<br />

Canadian Journal <strong>of</strong> Fisheries and<br />

Aquatic Science. 51:2626-2637.<br />

Graf, W.L. 1999. Dam nation: a<br />

geographic census <strong>of</strong> American dams<br />

and their large-scale hydrologic<br />

impacts. Water <strong>Resources</strong> Research<br />

35:1305-1311.<br />

Graf, W.L., editor. 2002. Dam removal<br />

research status and prospects.<br />

Proceed<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>of</strong> the He<strong>in</strong>z Center’s<br />

Dam Removal Research Workshop.<br />

The H. John He<strong>in</strong>z III Center for<br />

Science, Economics and the<br />

Environment. Wash<strong>in</strong>gton, D.C.<br />

Gray, R.H., T.L. Page, D.A. Neitzel, and<br />

D.D. Dauble. 1986. Assess<strong>in</strong>g<br />

population effects from entra<strong>in</strong>ment<br />

<strong>of</strong> fish at a large volume water<br />

<strong>in</strong>take. Journal <strong>of</strong> Environmental<br />

Science and Health A21:191-209.<br />

Hart, D.D., Johnson T.E., Bushaw-<br />

Newton K. L., Horwitz R. J.,<br />

Bednarek A. T., Charles D. F.,<br />

Kreeger D. A., and D. J. Vel<strong>in</strong>sky.<br />

2002. Dam removal: challenges and<br />

opportunities for ecological research<br />

and river restoration. BioScience<br />

52:669-681.<br />

Hart, D.D., and N.L. P<strong>of</strong>f. 2002. A<br />

special section on dam removal and<br />

river restoration. BioScience 52:653-<br />

655.<br />

Irv<strong>in</strong>g, D.B., and T. Modde. 2000. Home<br />

range fidelity and use <strong>of</strong> historic<br />

habitat by adult Colorado<br />

pikem<strong>in</strong>now (Ptychocheilus lucius)<br />

<strong>in</strong> the White <strong>River</strong>, Colorado and<br />

Utah. Western North American<br />

<strong>Natural</strong>ist. 60:16-25.<br />

Jaeger, M.E., A.V. Zale, T.E. McMahon,<br />

and B.J. Schmitz. 2005. Seasonal<br />

movements, habitat use, aggregation,<br />

exploitation, and entra<strong>in</strong>ment <strong>of</strong><br />

saugers <strong>in</strong> the Lower Yellowstone<br />

<strong>River</strong>: an empirical assessment <strong>of</strong><br />

factors affect<strong>in</strong>g population<br />

recovery. North American Journal<br />

<strong>of</strong> Fisheries Management 25:1550-<br />

1568.<br />

Jensen, A.L. 1990. Estimation <strong>of</strong><br />

recruitment forgone result<strong>in</strong>g from<br />

larval fish entra<strong>in</strong>ment. Journal <strong>of</strong><br />

Great Lakes <strong>Resources</strong> 16:241-244.<br />

Johnson, P.N., K. Bouchard, and F.A.<br />

Goetz. 2005. Effectiveness <strong>of</strong> strobe

lights for reduc<strong>in</strong>g juvenile salmonid<br />

entra<strong>in</strong>ment <strong>in</strong>to a navigation lock.<br />

North American Journal <strong>of</strong> Fisheries<br />

Management 25:491-501.<br />

Karr, J.R. 1991. Biological <strong>in</strong>tegrity: a<br />

long-neglected aspect <strong>of</strong> water<br />

resource management. Ecological<br />

Applications 1:66-84.<br />

Kendeigh, W.C. 1961. Animal ecology.<br />

Prentice-Hall. Englewood Cliffs,<br />

New Jersey.<br />

Knighton, D. 1998. Fluvial forms and<br />

processes. Oxford University Press,<br />

New York.<br />

[LCS] Ludlow Civic Society. 2001.<br />

Available:<br />

web.onetel.com/~jagludlow/waterme<br />

adows.htm. (April 2006).<br />

Leavitt, J. 1998. The functions <strong>of</strong><br />

riparian buffers <strong>in</strong> urban watersheds.<br />

Master’s Thesis. University <strong>of</strong><br />

Wash<strong>in</strong>gton, Seattle.<br />

Leggett, W.C. 1977. The ecology <strong>of</strong> fish<br />

migrations. Annual Review <strong>of</strong><br />

Ecology and Systematics. 8:285-308.<br />

Lucas, M.C., and E. Baras. 2001.<br />

Migration <strong>of</strong> freshwater fishes.<br />

Blackwell Science, London,<br />

England.<br />

McK<strong>in</strong>stry, C.A., M.A. Simmons, C.S.<br />

Simmons, and R.L. Johnson. 2005.<br />

Statistical assessment <strong>of</strong> fish<br />

behavior from split-beam hydroacoustic<br />

sampl<strong>in</strong>g. Fisheries<br />

Research 72:29-44.<br />

Merritt, D.M., and D.J. Cooper. 2000.<br />

Riparian vegetation and channel<br />

change <strong>in</strong> response to river<br />

regulation: a comparative study <strong>of</strong><br />

regulated and unregulated streams <strong>in</strong><br />

the Green <strong>River</strong> bas<strong>in</strong>, USA.<br />

Regulated <strong>River</strong>s: Research and<br />

Management 22:1–26.<br />

Merritt, D.M., and E.E. Wohl. 2002.<br />

Processes govern<strong>in</strong>g hydrochory<br />

along rivers: hydraulics, hydrology,<br />

and dispersal phenology. Ecological<br />

Applications 12:1071–1087.<br />

Merritt, D.M., and E.E. Wohl. 2006.<br />

Plant dispersal along rivers<br />

fragmented by dams. <strong>River</strong> Research<br />

and Applications 16:543–564.<br />

M<strong>in</strong>ckley, W.L. 1973. Fishes <strong>of</strong> Arizona.<br />

Arizona Game and Fish Department,<br />

Phoenix, Arizona.<br />

Moser, M.L., A.M. Darazsdi, and J.R.<br />

Hall. 2000. Improv<strong>in</strong>g passage<br />

efficiency <strong>of</strong> adult American shad at<br />

low-elevation dams with navigation<br />

locks. North American Journal <strong>of</strong><br />

Fisheries Management. 20:376-385.<br />

Moyle, P.B., and J.A. Israel. 2005.<br />

Untested assumptions: effectiveness<br />

<strong>of</strong> screen<strong>in</strong>g diversions for<br />

conservation <strong>of</strong> fish populations.<br />

Fisheries 30:20-25.<br />

Naiman, R.J., and H. Décamps. 1997.<br />

The ecology <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>terfaces: riparian<br />

zones. Annual Review <strong>of</strong> Ecology<br />

and Systematics. 28:621-658.<br />

Naiman, R.J., H. Décamps, and M.<br />

Pollock. 1993. The role <strong>of</strong> riparian<br />

corridors <strong>in</strong> ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g regional<br />

biodiversity. Ecological<br />

Applications 3:209-212.<br />

Newberry, R. 1995. <strong>River</strong>s and the art <strong>of</strong><br />

stream restoration. <strong>Natural</strong> and<br />

anthropogenic <strong>in</strong>fluences <strong>in</strong> fluvial<br />

geomorphology: Geophysical<br />

Monograph 89:137-149.<br />

New York Power Authority. 2005. Fish<br />

entra<strong>in</strong>ment and mortality study.<br />

Niagara Power Project FERC No.<br />

2216. White Pla<strong>in</strong>s, New York<br />

Pizzuto, J. 2002. Effects <strong>of</strong> dam removal<br />

on river form and process.<br />

BioScience 52:683-691.<br />

P<strong>of</strong>f, N.L., J.D. Allen, M.B. Ba<strong>in</strong>, J.R.<br />

Karr, K.L. Prestegaard, B.D.<br />

Richter, R.E. Sparks, and J.C.<br />

Stromberg. 1997. The natural flow<br />

regime: a paradigm for river

conservation and restoration.<br />

Bioscience 47:769–784.<br />

P<strong>of</strong>f, N.L., and D.D. Hart. 2002. How<br />

dams vary and why it matters for the<br />

emerg<strong>in</strong>g science <strong>of</strong> dam removal.<br />

BioScience 52:659-668.<br />

Rago, P.J. 1984. Production forgone: An<br />

alternative method for assess<strong>in</strong>g the<br />

consequences <strong>of</strong> fish entra<strong>in</strong>ment<br />

and imp<strong>in</strong>gement losses at power<br />

plants and other water <strong>in</strong>takes.<br />

Ecological Model<strong>in</strong>g 24:79-111.<br />

Rohde, F.C., R.G. Arndt, D.G.<br />

L<strong>in</strong>dquist, and J.F. Parnell. 1994.<br />

Freshwater fishes <strong>of</strong> the Carol<strong>in</strong>as,<br />

Virg<strong>in</strong>ia, Maryland, and Delaware.<br />

The University <strong>of</strong> North Carol<strong>in</strong>a<br />

Press. USA.<br />

Rood, S.B., J.H. Braatne, and F.M.R.<br />

Hughes. 2003 Ecophysiology <strong>of</strong><br />

riparian cottonwoods: stream flow<br />

dependency, water relations and<br />

restoration. Tree Physiology<br />

23:1113–1124.<br />

Rood, S.B., and J.M. Mahoney. 1990.<br />

Collapse <strong>of</strong> riparian poplar forests<br />

downstream from dams <strong>in</strong> western<br />

prairies: probable causes and<br />

prospects for mitigation.<br />

Environmental Management 14:451–<br />

464.<br />

Santucci, V.J., Jr., S.R. Gephard, and S.<br />

M. Pescitelli. 2005. Effects <strong>of</strong><br />

multiple low-head dams on fish,<br />

macro<strong>in</strong>vertebrates, habitat, and<br />

water quality <strong>in</strong> the Fox <strong>River</strong>,<br />

Ill<strong>in</strong>ois. North American Journal <strong>of</strong><br />

Fisheries Management 25:975–992.<br />

Savitz, J., L.G. Bardygula-Nonn, R.A.<br />

Nonn, and G. Wojtowicz. 1998.<br />

Imp<strong>in</strong>gement and entra<strong>in</strong>ment <strong>of</strong><br />

fishes with<strong>in</strong> a high volume-low<br />

velocity deep water <strong>in</strong>take system on<br />

Lake Michigan. Journal <strong>of</strong><br />

Freshwater Ecology 13:165-169.<br />

Segelquist, C.A., M.L. Scott, and G.T.<br />

Auble. 1993. Establishment <strong>of</strong><br />

Populus deltoids under simulated<br />

alluvial groundwater decl<strong>in</strong>es.<br />

American Midland <strong>Natural</strong>ist<br />

130:274-285.<br />

Spankle, K. 2005. Interdam movements<br />

and passage attraction <strong>of</strong> American<br />

shad <strong>in</strong> the lower Merrimack <strong>River</strong><br />

ma<strong>in</strong> stem. North American Journal<br />

<strong>of</strong> Fisheries Management. 25:1456-<br />

1466.<br />

Stanley, E.H., M.A. Luebke, M.W.<br />

Doyle, and D.W. Marshall. 2002.<br />

Short-term changes <strong>in</strong> channel form<br />

and macro<strong>in</strong>vertebrate communities<br />

follow<strong>in</strong>g low-head dam removal.<br />

Journal <strong>of</strong> the North American<br />

Benthological Society 21:172-187.<br />

Travnichek, V.H., A.V. Zale, and W.L.<br />

Fisher. 1993. Entra<strong>in</strong>ment <strong>of</strong><br />

ichthyoplankton by a warmwater<br />

hydroelectric facility. Transactions<br />

<strong>of</strong> the American Fisheries Society<br />

122:709-716.<br />

Tyus, H.M. 1986. Life strategies <strong>in</strong> the<br />

evolution <strong>of</strong> the Colorado squawfish<br />

(Ptychocheilus lucius). Great Bas<strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>Natural</strong>ist. 46:656-661.<br />

Tyus, H.M. 1990. Potamodromy and<br />

reproduction <strong>of</strong> Colorado squawfish<br />

<strong>in</strong> the Green <strong>River</strong> Bas<strong>in</strong>, Colorado<br />

and Utah. Transactions <strong>of</strong> the<br />

American Fisheries Society.<br />

119:1035-1047.<br />

Tyus, H.M., and C.W. McAda. 1984.<br />

Migration, movements and habitat<br />

preferences <strong>of</strong> Colorado squawfish,<br />

Ptychocheilus lucius, <strong>in</strong> the Green,<br />

White, and Yampa <strong>River</strong>s, Colorado<br />

and Utah. The Southwestern<br />

<strong>Natural</strong>ist. 29:289-299.<br />

[USFWS] (United States Fish and<br />

Wildlife Service). 2001.<br />

Biological/Conference Op<strong>in</strong>ion<br />

regard<strong>in</strong>g the effects <strong>of</strong> long term

operation <strong>of</strong> the Bureau <strong>of</strong><br />

Reclamation’s Klamath Project on<br />

the Endangered Lost <strong>River</strong> sucker<br />

(Deltistes luxatus), Endangered<br />

shortnose sucker (Chasmistes<br />

brevirostris), Threatened BALD<br />

EAGLE (Haliaeetus leucocephalus),<br />

and proposed critical habitat for the<br />

Lost <strong>River</strong> and shortnose suckers.<br />

US Fish and Wildlife Service,<br />

Klamath Falls, OR.<br />

[USFWS] United States Fish and<br />

Wildlife Service. 2005. Connecticut<br />

<strong>River</strong> Coord<strong>in</strong>ator’s Office:<br />

Restor<strong>in</strong>g migratory fish to the<br />

Connecticut <strong>River</strong> bas<strong>in</strong>. Available:<br />

http://www.fws.gov/r5crc/Habitat/fis<br />

h_passage.htm. (April 2006).<br />

Wenger, S. 1999. A review <strong>of</strong> the<br />

scientific literature on riparian buffer<br />

width, extent and vegetation. Office<br />

<strong>of</strong> Public Service & Outreach,<br />

Institute <strong>of</strong> Ecology, University <strong>of</strong><br />

Georgia, Athens.<br />

W<strong>in</strong>kle, W.V., and J. Kadvany. 2003.<br />

Model<strong>in</strong>g fish entra<strong>in</strong>ment and<br />

imp<strong>in</strong>gement impacts: bridg<strong>in</strong>g<br />

science and policy. Pages 46-69 <strong>in</strong><br />

V.H. Dale, editor. Ecological<br />

model<strong>in</strong>g for resource management.<br />

Spr<strong>in</strong>ger-Verlage, New York.<br />

W<strong>in</strong>ston, M.R., C.M. Taylor, and J.<br />

Pigg. 1991. Upstream extirpation <strong>of</strong><br />

four m<strong>in</strong>now species due to<br />

damm<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> a prairie stream.<br />

Transactions <strong>of</strong> the American<br />

Fisheries Society. 120:98-105.