Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

PaulineViardot<br />

andFriends<br />

ORR240<br />

In association with Prima Donna Productions<br />

Box cover: Pauline Viardot, c. 1853, by Eugène (Jevgenij) Pluchart<br />

(1798-1880). Oil on canvas. akg-images<br />

<strong>Book</strong> cover: Pauline Viardot<br />

CD faces: CD 1 ‘Scène d’Hermione’ by Pauline Viardot<br />

CD 2 ‘La Captive’ by Hector Berlioz<br />

Opposite: Pauline Viardot at 75<br />

–1–

CONTENTS<br />

Pauline Viardot – A Chronology and Introduction............................................Page 9<br />

Pauline Viardot – Présentation........................................................................Page 21<br />

Pauline Viardot – Einführung.........................................................................Page 31<br />

Pauline Viardot – Introduzione.......................................................................Page 41<br />

Notes and song texts.......................................................................................Page 51<br />

Picture credits:<br />

Pages 8, 20, 30 and 104 Pauline Viardot courtesy of the Wigmore Hall, pages 40 and 56 Opera Rara<br />

archive.<br />

Page 82 Giacomo Meyerbeer by kind permission of the Brigham Young University, Harold B. Lee<br />

Library, Music Special Collections<br />

Page 15 Portrait of George Sand (1804-76) 1830 (pastel on paper) by Candide Blaize<br />

(1795-c.1855) ©Musée de la Ville de Paris, Musée Carnavalet, Paris France/Lauros/Giraudon/The<br />

Bridgeman Art Library<br />

Page 17 Ivan Sergeevich Turgenev (1818-83) (b&w photo) ©Private Collection/The Bridgeman Art<br />

Library<br />

Page 79 Charles-Francois Gounod (1818-93) late 19th century (b&w photo) by French<br />

photographer, ©Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris, France/Giraudon/The Bridgeman Art Library<br />

Page 84 Frederic Chopin (1810-49) engraved by Gottfried Engelmann (1788-1839) 1833 litho by<br />

Pierre Roch Vigneron (1789-1872) ©The Cobbe Collection Trust, UK/The Bridgeman Art Library<br />

Page 89 Portrait of Hector Berlioz (1803-69) (oil on canvas) (b&w photo) by Emile Signol<br />

(1804-94) ©Villa Medici, Rome, Italy/Roger-Viollet, Paris/The Bridgeman Art Library<br />

–2–

Managing Director: Stephen Revell<br />

Producer: James Mallinson<br />

Assistant Producer: Ludmilla Andrew<br />

Music research and translations by Marta Johansen<br />

Concert performance directed by Lotfi Mansouri<br />

Narration on this album is excerpted from the original monologues<br />

by Georgia Smith (©2005)<br />

French coach: Michel Vallat<br />

German coach: Hildburgh Williams<br />

Russian coach: Ludmilla Andrew<br />

Chronology, introduction and notes on songs: Patrick O’Connor<br />

Transcriptions of songs for this album<br />

were made by Ian Schofield<br />

Recording Engineer: Chris Braclik<br />

Assistant Engineers: Chris Bowman and Tom Bennellick<br />

Editing: James Mallinson and Classic Sound<br />

Recorded live at the Wigmore Hall, 27 February 2006<br />

–3–

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS<br />

Anyone who writes about Pauline Viardot is indebted to the late April Fitzylon,<br />

whose biography The Price of Genius (John Calder, 1964) remains the definitive<br />

study of Viardot’s life.<br />

Other sources consulted:<br />

David Cairns: Berlioz (2 Vols, Allen Lane, 1999)<br />

April Fitzlyon and Alexander Schouvaloff: Turgenev’s ‘A Month in the Country’<br />

(Victoria and Albert Museum, 1983)<br />

James Radomski: Manuel García (in The New Grove Dictionary of Music and<br />

Musicians, 2000 edition)<br />

Ivan Turgenev: Poems and Prose, translated by Evgenia Schimanskaya<br />

(Lindsay Drummond, 1945)<br />

Viardot-García, Pauline, 1821-1910. Papers: Guide (Houghton Library,<br />

Harvard University, MA)<br />

Patrick Waddington: Pauline Viardot-García, a chronological catalogue<br />

(Whirinaki Press, NZ, 2001)<br />

–4–<br />

Patrick O’Connor, 2007

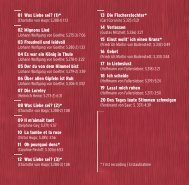

CD 1 37’56<br />

Frederica von Stade, Anna Caterina Antonacci, Vladimir Chernov<br />

David Watkin (cello), David Harper – piano<br />

Fanny Ardant – narrator<br />

Duration Page<br />

[1] Fanny Ardant, narration 1’42<br />

[2] ‘Две розы ’ (Dve rozy) – Pauline Viardot 1’16 51<br />

Vladimir Chernov<br />

[3] Fanny Ardant, narration 0’15<br />

[4] ‘Celos’ – Manuel García 2’47 53<br />

Anna Caterina Antonacci<br />

[5] Fanny Ardant, narration 0’32<br />

[6] ‘La regata veneziana’ – Gioachino Rossini 3’53 57<br />

Frederica von Stade, Anna Caterina Antonacci<br />

[7] Fanny Ardant, narration 0’40<br />

[8] ‘L’absence’ – Pauline Viardot 1’55 60<br />

Frederica von Stade<br />

[9] Fanny Ardant, narration 0’06<br />

[10] ‘Berceuse’ – Pauline Viardot 2’51 62<br />

Frederica von Stade<br />

[11] Fanny Ardant, narration 0’26<br />

[12] ‘Le chêne et le roseau’ – Pauline Viardot 4’53 64<br />

Anna Caterina Antonacci<br />

[13] Fanny Ardant, narration 1’54<br />

[14] ‘Утёс’ (Utës) – Pauline Viardot 3’31 66<br />

Vladimir Chernov<br />

–5–

Duration Page<br />

[15] ‘Die Sterne’ – Pauline Viardot 4’05 67<br />

Frederica von Stade, David Watkin (cello)<br />

[16] Fanny Ardant, narration 0’05<br />

[17] ‘Scène d’Hermione’ – Pauline Viardot 6’54 70<br />

Anna Caterina Antonacci<br />

CD 2 45’20<br />

[1] Fanny Ardant, narration 0’29<br />

[2] ‘Синица’ (Sinitsa) – Pauline Viardot 2’11 75<br />

Vladimir Chernov<br />

[3] Fanny Ardant, narration 0’37<br />

[4] ‘Indécision’ – Pauline Viardot 1’48 77<br />

Frederica von Stade<br />

[5] Fanny Ardant, narration 0’16<br />

[6] ‘Chanson de printemps’ – Charles Gounod 1’53 80<br />

Vladimir Chernov<br />

[7] Fanny Ardant, narration 0’19<br />

[8] ‘Délire’ – Giacomo Meyerbeer 3’02 81<br />

Anna Caterina Antonacci<br />

[9] ‘Berceuse’ – Fryderyk Chopin 1’21 85<br />

Frederica von Stade<br />

[10] Fanny Ardant, narration 0’25<br />

[11] ‘Allein’ – Pauline Viardot 2’36 87<br />

Anna Caterina Antonacci<br />

[12] Fanny Ardant, narration 0’26<br />

[13] ‘La captive’ Op.12 – Hector Berlioz 4’24 88<br />

Frederica von Stade, David Watkin (cello)<br />

–6–

Duration Page<br />

[14] ‘En mer’ – Pauline Viardot 5’36 92<br />

Vladimir Chernov<br />

[15] Fanny Ardant, narration 1’17<br />

[16] ‘Буря’ (Buria) – Pauline Viardot 4’24 94<br />

Vladimir Chernov<br />

[17] ‘C’est moi’ – Pauline Viardot 4’07 98<br />

Frederica von Stade, Vladimir Chernov<br />

[18] Fanny Ardant, narration 1’03<br />

[19] ‘Ici-bas tous les lilas meurent’ – Pauline Viardot 2’03 100<br />

Anna Caterina Antonacci<br />

[20] Fanny Ardant, narration 0’23<br />

[21] ‘Заклинаниe’ (Zaklinanie) – Pauline Viardot 3’28 101<br />

Vladimir Chernov<br />

[22] Fanny Ardant, narration 0’24<br />

[23] ‘Havanaise’ – Pauline Viardot 2’37 105<br />

Frederica von Stade, Anna Caterina Antonacci,<br />

Vladimir Chernov<br />

Translations of дверозы (Dve rozy), утёс(Utës) by Marta Johansen and Robert Leek.<br />

La regata veneziana, L’absence, Le chêne et le roseau, Indécision, Chanson de printemps,<br />

La captive, C’est moi by Richard Stokes and Mireille Ribèrie. Berceuse, Ici-bas tous les<br />

lilas meurent by Marta Johansen and Georgia Smith. Die Sterne, Allein, En mer by<br />

Marta Johansen. Celos, Délire by Jacqueline Cockburn. Буря (Buria) from<br />

www.pushkins-poems.com, Заклинаниe(Zaklinanie) by Marta Johansen,<br />

Robert Leek and Georgia Smith, Havanaise by Avril Bardoni.<br />

Cyrillic text and translations by Olia Grebenyuk.<br />

–7–

Pauline Viardot<br />

(self-portrait)

PAULINE VIARDOT – A Chronology<br />

1821 Birth in Paris of Pauline García, 18 July, youngest child of Manuel<br />

García (1775-1832) and his second wife, Joaquina García (1780-1854).<br />

1825 García family go to America, and in New York give the first US<br />

performances of operas by Rossini and Mozart, including Don<br />

Giovanni. Meeting with Lorenzo Da Ponte. Pauline’s older sister,<br />

Maria García, meets and marries Eugène Malibran.<br />

1832 Begins piano studies with Liszt.<br />

1834 Appears as pianist in concerts with her sister Maria and Charles de<br />

Bériot.<br />

1836 Death of Maria Malibran.<br />

1839 Pauline García’s stage debut, as Desdemona in Rossini’s Otello<br />

(Her Majesty’s, London); Paris debut (Odéon).<br />

1840 Marriage to Louis Viardot.<br />

1841 Vienna debut as Rosina in Il barbiere di Siviglia.<br />

1843 St Petersburg debut; first meeting with Turgenev.<br />

–9–

1844 Second Russian season; debut as Norma.<br />

1848 Appears in concert in London with Chopin, when she sings her own<br />

arrangements of several of his mazurkas.<br />

1849 Creates the role of Fidès in Meyerbeer’s Le prophète, Paris Opéra,<br />

16 April.<br />

1851 Title role in premiere of Gounod’s Sapho, Paris Opéra, 16 March.<br />

1855 Sings Azucena in first London performance of Verdi’s Il trovatore.<br />

1859 Lady Macbeth in Verdi’s opera, Dublin and Manchester.<br />

1859 Sings title-role in Berlioz’s edition of Gluck’s Orphée, Paris Théâtre<br />

Lyrique.<br />

1860 Sings Isolde in private performance of Act II of Tristan und Isolde,<br />

with Wagner as Tristan.<br />

1861 Gluck’s Alceste, Paris Opéra.<br />

1869 Viardot’s Le dernier sorcier performed at Weimar.<br />

1870 Gives first performance of Brahms’s Alto Rhapsody in Jena.<br />

–10–

1873 Sings Massenet’s Marie Magdeleine, Paris Odéon.<br />

1874 Dalila in private performance of Acts I and II of Samson et Dalila,<br />

accompanied by Saint-Saëns.<br />

1876 Death of George Sand.<br />

1883 Deaths of Louis Viardot and Ivan Turgenev.<br />

1889 Meeting, in Paris, with Tchaikovsky to whom she shows the<br />

manuscript score of Mozart’s Don Giovanni, which she later presents<br />

to the Paris Conservatoire.<br />

1901 Awarded Légion d’Honneur by the French government.<br />

1910 Death of Pauline Viardot, 18 May.<br />

–11–

PAULINE VIARDOT 1821–1910<br />

HECTOR BERLIOZ described one of Pauline Viardot’s performances: “All<br />

her poses, her gestures, her expressions… are studied with profound art. As<br />

to the perfection of her singing, the extreme skill of her vocalisation, her<br />

musical assurance – those are things known and appreciated by<br />

everyone…Madame Viardot is one of the greatest artists… in the past and<br />

present history of music.”<br />

Pauline Viardot’s reputation lived on for decades after she had ceased to<br />

perform. Like that of her elder sister, Maria Malibran, her name came to be<br />

associated with a romantic ideal, the notion of striving for perfection that so<br />

suited the modern writers and free-thinkers of the mid-19th century.<br />

Pauline was born into a family of musicians and actors, and grew up<br />

backstage. Her father, Manuel García, was born in Seville in 1775. He<br />

trained as a chorister at Seville Cathedral and – having escaped the knife –<br />

became an accomplished tenor soloist. He was equally, if not more, successful<br />

as a composer, having many works performed in Madrid, where he became<br />

one of the resident composers at the Teatro del Principe. García was first<br />

married to the soprano Manuela Morales, with whom he had two daughters,<br />

but in 1807 he made his way to Paris, accompanied by the singer Joaquina<br />

Briones, who eventually became his second wife and the mother of his three<br />

famous children, Manuel, Maria and Pauline.<br />

–12–

García created the roles of Norfolk in Rossini’s Elisabetta, regina<br />

d’Inghilterra, and later that of Almaviva in Il barbiere di Siviglia. Renowned<br />

in Italy, France and England, García was considered the greatest interpreter<br />

of Rossini’s Otello. In 1826 García, his family and a small company went to<br />

America where they gave the first performances of Italian opera in New York.<br />

With his son as Figaro, and his daughter Maria as Rosina, García sang<br />

Almaviva once more. Lorenzo Da Ponte, then teaching at Columbia<br />

University, urged them to put on Don Giovanni, and thus Mozart’s opera was<br />

given its US premiere, with the librettist in attendance.<br />

When Maria left her parents to marry her first husband, Eugène Malibran,<br />

the family, without their leading prima-donna, embarked on a tour of<br />

Mexico. One of Pauline’s most vivid childhood recollections was of an<br />

ambush, in which the travellers were attacked by bandits, and lost all their<br />

money and possessions. On their return to Europe, García began to teach,<br />

his voice having all but given out. His pupils included such famous names as<br />

Adolphe Nourrit, Henriette Méric-Lalande (Donizetti’s first Lucrezia Borgia)<br />

and eventually Pauline herself. She was only 11, though, when her father<br />

died, and in 1836, after the untimely death of Maria Malibran, it was<br />

decided by Mme García that Pauline, who wanted to be a pianist, and had<br />

studied for a while with Liszt, should instead devote her studies to singing.<br />

She made her debut as Desdemona in Rossini’s Otello, the work that had<br />

been so closely associated with both her father and her sister; she was an<br />

immediate success. At the age of 19, having rejected the poet Alfred de<br />

–13–

Musset, she married Louis Viardot, director of the Théâtre Italien in Paris.<br />

He left his post to oversee her career.<br />

Pauline Viardot had triumphs as great as those of her sister, in London,<br />

Paris, Vienna, Berlin and, above all, St Petersburg. She seems never to have<br />

appeared in Italy. This may have been because of the fierce rivalry she enjoyed<br />

for a while with Giulia Grisi, even though the two of them appeared together<br />

in Rossini’s Semiramide and Bellini’s I Capuleti e i Montecchi.<br />

An accomplished linguist, from her adolescence Pauline Viardot began to<br />

build a wide circle of friends and acquaintances which eventually represented<br />

the intellectual and musical élite of Europe. Chopin, Liszt, Berlioz, Gounod,<br />

Meyerbeer, Saint-Saëns, Schumann and Fauré all composed or dedicated<br />

works for her. Alfred de Musset, Flaubert, Dickens, Delacroix, even Henry<br />

James as a young man, were all admirers, but the two greatest friendships of<br />

her life were with the writers George Sand and Ivan Turgenev.<br />

George Sand first met Pauline shortly after her Paris debut in 1839. The<br />

following year Mme Sand wrote a long article in praise of the young singer,<br />

and soon Pauline was a treasured member of the group that was invited to<br />

stay at George Sand’s country house at Nohant. Sand modelled the central<br />

character in her novel Consuelo on Pauline. Although set in the 18th century,<br />

the protagonist, a Spanish singer, was easily recognisable to their friends:<br />

–14–

George Sand<br />

(1804-1876)

‘The pale, still – one might at first glance say lustreless –<br />

countenance, the suave and unconstrained movements, the<br />

astonishing freedom from every sort of affectation, how transfigured<br />

and illumined all this appears when she is carried away by her genius<br />

on the current of song.’<br />

What was Viardot’s voice like? She would nowadays be classified as a<br />

mezzo-soprano, and the repertory she sang, the heroines of Rossini, Bellini<br />

and even Donizetti, a little Mozart (Zerlina and Donna Anna), and then later<br />

operas by Meyerbeer, Gounod and Verdi, can give one a fair idea. Her<br />

greatest triumph was in Berlioz’s edition of Gluck’s Orphée, a part she sang<br />

150 times. The critic Henry Chorley wrote:<br />

‘The peculiar quality of Mme Viardot’s voice – its unevenness, its<br />

occasional harshness and feebleness, consistent with tones of the<br />

gentlest sweetness – was turned by her to account with rare felicity as<br />

giving the variety of light and shade to every word of soliloquy, to<br />

every appeal of dialogue.’<br />

When Pauline Viardot decided to retire from the stage, making her farewell<br />

as Orphée in Paris, she was 42 (almost exactly the same age as Maria Callas<br />

would be when she too retired).<br />

In 1862 the Viardots left Paris – they were utterly opposed to the regime<br />

of Napoleon III – and took up residence in Baden-Baden. There, they were<br />

–16–

Ivan Turgenev<br />

(1818-1883)

joined by Turgenev, who had been in love with Pauline since he had first met<br />

her in St Petersburg in the 1840s. Although there had been periods in which<br />

they had not been in touch, Pauline had taken Turgenev’s illegitimate<br />

daughter and brought her up with her own family. Inevitably, this also led to<br />

much friction. Nevertheless, Turgenev lived for much of the rest of his life<br />

with Louis and Pauline. This complicated ménage à trois finds an echo in<br />

several of Turgenev’s novels, and in his play A Month in the Country. In her<br />

biography of Pauline Viardot, The Price of Genius, April Fitzlyon wrote that<br />

the typical Turgenev heroine was a married woman: ‘They are almost always<br />

predatory, masterful, self-seeking, dangerously attractive; they scarcely ever<br />

make the men who love them happy, they almost always dominate them.’<br />

Turgenev undoubtedly enjoyed the happiest times of his life living in the<br />

Viardots’ houses, in Baden or later, after the Franco-Prussian war and the<br />

dissolution of the Second Empire, in Paris, and finally at Bougival, where he<br />

died in 1883. Turgenev wrote three librettos for Viardot’s operettas, works<br />

designed to be performed not in the theatre, but as amateur theatricals at<br />

home (Trop de femmes, L’ogre and Le dernier sorcier). Some of his conservative<br />

Russian friends pretended to be shocked that Turgenev took part occasionally<br />

in these performances. He was oblivious to criticism where Pauline was<br />

concerned, and wrote to her: “I am so happy at the thought that everything,<br />

everything in me to the very depths is linked with your being, and depends<br />

on you. If I am a tree, then you are my roots and crown.”<br />

–18–

It has taken nearly a century since Pauline Viardot’s death for performers<br />

and listeners to take an interest in her music. From her adolescence she had<br />

composed songs and piano pieces. Some of these were published long after<br />

they were composed, and there is speculation about the dates of many of them.<br />

Although Viardot did not consider herself to be a composer, or so it is said, she<br />

achieved more than most women of her time working in this pre-eminently<br />

male sphere. She grew up in Paris when the vogue for romances and<br />

chansonnettes dominated the vocal-music publishing business. Through her<br />

acquaintance with Schumann, and later Gounod, Berlioz, Tchaikovsky and<br />

Fauré, she saw the whole notion of song transformed into a separate art. Her<br />

choice of poets reflects the trajectory of her life, including Mörike, Lermontov<br />

and Turgenev. As a child she had met Lorenzo Da Ponte, Mozart’s librettist;<br />

she lived long enough to know the music of Debussy and Richard Strauss.<br />

Pauline Viardot’s life in many ways sums up the whole history of music in the<br />

19th century.<br />

–19–<br />

© Patrick O’Connor, 2007

Pauline Viardot

PAULINE VIARDOT – Chronologie<br />

1821 Naissance le 18 juillet à Paris de Pauline García, troisième et dernier<br />

enfant de Manuel García (1775-1832) et de sa seconde épouse<br />

Joaquina García (1780-1854).<br />

1825 La famille García se rend aux États-Unis, et donne à New York les<br />

toutes premières représentations sur le sol américain des opéras de<br />

Rossini et Mozart – notamment Don Giovanni. Rencontre avec<br />

Lorenzo Da Ponte. Maria García, sœur aînée de Pauline, rencontre et<br />

épouse Eugène Malibran.<br />

1832 Pauline prend ses premières leçons de piano avec Liszt.<br />

1834 Elle se produit en concert comme pianiste aux côtés de Maria et de<br />

Charles de Bériot.<br />

1836 Décès de Maria Malibran.<br />

1839 Débuts de Pauline García sur scène, en Desdemona dans Otello de<br />

Rossini au Majesty’s Theatre de Londres ; débuts parisiens à l’Odéon.<br />

1840 Elle épouse Louis Viardot.<br />

1841 Débuts à Vienne en Rosina dans Il barbiere di Siviglia.<br />

–21–

1843 Débuts à Saint-Pétersbourg ; elle fait la connaissance de Tourgueniev.<br />

1844 Deuxième saison en Russie ; débuts dans le rôle de Norma.<br />

1848 Elle se produit en concert à Londres avec Chopin et, à cette occasion,<br />

chante plusieurs mazurkas dont elle a fait elle-même l’arrangement.<br />

1849 16 avril, elle crée le rôle de Fidès dans Le prophète de Meyerbeer à<br />

l’Opéra de Paris.<br />

1851 16 mars, elle interprète le rôle-titre de Sapho de Gounod lors de sa<br />

création à l’Opéra de Paris.<br />

1855 Elle chante Azucena dans Il trovatore de Verdi lors de sa création à<br />

Londres.<br />

1859 Elle incarne Lady Macbeth dans l’opéra éponyme de Verdi à Dublin et<br />

à Manchester.<br />

1859 À Paris, au Théâtre Lyrique, elle chante le rôle-titre de l’Orphée de<br />

Gluck adapté à son intention par Berlioz.<br />

1860 Elle incarne Isolde lors d’une représentation privée de l’acte II de<br />

Tristan und Isolde, aux côtés de Wagner dans le rôle de Tristan.<br />

–22–

1861 Alceste de Gluck à l’Opéra de Paris.<br />

1869 Le dernier sorcier de Viardot est joué à Weimar.<br />

1870 Elle participe à la création de la Rhapsodie pour contralto de Brahms à<br />

Iéna.<br />

1873 Elle chante Marie Magdeleine de Massenet à l’Odéon.<br />

1874 Avec Saint-Saëns au piano, elle interprète Dalila lors de la<br />

représentation privée des actes I et II de Samson et Dalila.<br />

1876 Décès de George Sand.<br />

1883 Décès de Louis Viardot et d’Ivan Tourgueniev.<br />

1889 Elle rencontre Tchaïkovski à Paris et lui montre la partition<br />

autographe de Don Giovanni de Mozart dont elle fera don au<br />

Conservatoire de Paris.<br />

1901 Le gouvernement français la décore de la Légion d’honneur.<br />

1910 Décès de Pauline Viardot, le 18 mai.<br />

–23–

PAULINE VIARDOT 1821–1910<br />

HECTOR BERLIOZ, qui avait assisté à un concert de Pauline Viardot,<br />

vantait la recherche dont témoignaient son jeu et sa gestuelle, ainsi que la<br />

perfection de son chant, la richesse de sa vocalisation et son assurance<br />

musicale : « Madame Viardot est l’une des plus grandes artistes dont le nom<br />

vient à l’esprit, dans le passé ou le présent. »<br />

La réputation de Pauline Viardot perdurera longtemps après ses adieux à la<br />

scène. Comme celui de sa sœur aînée, Maria Malibran, son nom en vient à<br />

symboliser la recherche inlassable de la perfection, idéal romantique cher aux<br />

écrivains modernes et aux libres-penseurs du milieu du XIX e siècle.<br />

Issue d’une famille de musiciens et de comédiens, Pauline grandit dans les<br />

coulisses des théâtres. Manuel García, son père, est né à Séville en 1775.<br />

Jeune choriste à la cathédrale de Séville, il a échappé au scalpel pour devenir<br />

un grand ténor soliste. Il est également, sinon plus, connu pour ses<br />

compositions : nombre de ses œuvres sont jouées à Madrid où il séjourne<br />

comme compositeur en résidence au Teatro del Principe. Après avoir épousé<br />

en premières noces la soprano Manuela Morales, qui lui a donné deux filles,<br />

García se rend à Paris en 1807 en compagnie de la cantatrice Joaquina<br />

Briones, qui devient sa seconde épouse et la mère de trois enfants promis à la<br />

célébrité, Manuel, Maria et Pauline.<br />

–24–

García, qui a créé le rôle de Norfolk dans Elisabetta, regina d’Inghilterra de<br />

Rossini, participe également à la création d’Il barbiere di Siviglia en Almaviva.<br />

Célèbre en Italie et en France comme en Angleterre, García est considéré le<br />

plus grand Otello rossinien. Accompagné de sa famille et d’une petite troupe,<br />

il s’embarque en 1826 pour New York où il est le premier à présenter des<br />

opéras italiens au public américain. Avec son fils Manuel en Figaro et sa fille<br />

Maria en Rosina, Garcia incarne à nouveau Almaviva. Lorenzo Da Ponte, qui<br />

enseigne alors à la Columbia University, le presse de monter Don Giovanni,<br />

et c’est ainsi que l’opéra de Mozart est créé aux États-Unis en présence du<br />

librettiste.<br />

Lorsque Maria quitte ses parents pour épouser Eugène Malibran, la famille<br />

se retrouve sans chanteuse principale et se lance dans une tournée au<br />

Mexique. L’un des souvenirs d’enfance les plus mémorables de Pauline est<br />

celui d’une embuscade au cours de laquelle les voyageurs furent attaqués par<br />

des bandits et dépouillés de tout – argent et bagages. De retour en Europe,<br />

Garcia, dont la voix a fini par se casser se met à donner des cours de chant et<br />

compte parmi ses élèves de futurs grands noms comme Adolphe Nourrit,<br />

Henriette Méric-Lalande (qui créera Lucrezia Borgia de Donizetti) et Pauline<br />

elle-même. Elle n’a que 11 ans, mais lorsque son père meurt en 1836, peu<br />

après la disparition prématurée de Maria Malibran, sa mère décide que<br />

Pauline, qui a toujours voulu être pianiste et a eu Liszt comme professeur, se<br />

consacrera d’abord au chant.<br />

–25–

Elle débute en Desdemona dans Otello de Rossini, œuvre étroitement<br />

associée à son père et à sa sœur, et son succès est immédiat. À l’âge de 19 ans,<br />

ayant rejeté les avances du poète Alfred de Musset, elle épouse Louis Viardot,<br />

alors directeur du Théâtre italien de Paris, qui renoncera à ce poste pour<br />

s’occuper de la carrière de la jeune femme.<br />

À Londres, à Paris, à Vienne, à Berlin et surtout à Saint-Pétersbourg, Pauline<br />

Viardot remporte un succès comparable à celui de sa sœur. Si elle ne se produit<br />

apparemment jamais en Italie, peut-être est-ce en raison de la rivalité féroce qui<br />

l’oppose pendant un certain temps à Giulia Grisi – avec laquelle elle interprète<br />

pourtant Semiramide de Rossini et I Capuleti e i Montecchi de Bellini.<br />

Particulièrement douée pour les langues, Pauline Viardot se constitue dès<br />

l’adolescence un large cercle d’amis et de relations qui représenteront bientôt<br />

l’élite intellectuelle et musicale d’Europe. Chopin, Liszt, Berlioz, Gounod,<br />

Meyerbeer, Saint-Saëns, Schumann et Fauré lui composent ou dédient des<br />

œuvres. Elle compte parmi ses admirateurs Alfred de Musset, Flaubert,<br />

Dickens, Delacroix, voire le jeune Henry James, mais les deux plus grandes<br />

amitiés de sa vie sont avec des écrivains : George Sand et Ivan Tourgueniev.<br />

George Sand fait la connaissance de Pauline Viardot peu après ses débuts<br />

parisiens en 1839. L’année suivante, Sand dresse l’éloge de la jeune cantatrice<br />

dans un long article de presse, et bientôt Pauline est un membre très apprécié<br />

du groupe invité par Sand dans sa maison de campagne à Nohant. L’écrivain<br />

s’inspire d’ailleurs de Pauline pour le personnage principal de Consuelo. Bien<br />

–26–

que l’intrigue du roman se situe au XVIII e siècle, les amis des deux femmes<br />

n’ont aucun doute sur l’identité de celle qui a servi de modèle à la cantatrice<br />

espagnole :<br />

« La pâleur, l’immobilité – le manque d’éclat, pourrait-on même<br />

dire à première vue – de son visage, la grâce et la spontanéité de ses<br />

mouvements, l’étonnante absence de toute forme d’affectation,<br />

comme tout cela se transforme et s’illumine lorsque son génie se laisse<br />

emporter par le flot du chant. »<br />

Quelle voix la Viardot avait-elle ? Aujourd’hui on la classerait parmi les<br />

mezzo-sopranos, et son répertoire – les héroïnes de Rossini, Bellini et parfois<br />

Donizetti, quelques rôles mozartiens (Zerlina et Donna Anna) et, plus tard,<br />

les opéras de Meyerbeer, Gounod et Verdi – en donne une assez bonne idée.<br />

Sa gloire atteint son apogée avec l’Orphée de Gluck dans la version de Berlioz,<br />

qu’elle interprète quelque 150 fois. Le critique Henry Chorley écrit alors :<br />

« La voix mobile de Mme Viardot – faite tantôt de dureté, tantôt<br />

de faiblesse alliées à un timbre d’une extrême douceur – rend avec un<br />

rare bonheur toutes les nuances de chaque monologue, de chaque<br />

imploration. »<br />

Lorsque Pauline Viardot décide de faire ses adieux à la scène de l’opéra,<br />

c’est Orphée qu’elle chante. Elle a alors 42 ans (l’âge, ou presque, auquel<br />

Maria Callas choisira également de se retirer).<br />

–27–

Profondément opposés au régime de Napoléon III, les Viardot quittent<br />

Paris en 1862 pour s’installer à Baden-Baden. Ils y sont rejoints par<br />

Tourgueniev, très épris de Pauline depuis leur première rencontre à Saint-<br />

Pétersbourg dans les années 1840 ; malgré des contacts parfois épisodiques,<br />

Pauline s’est occupée de la fille illégitime de Tourgueniev et l’a élevée au sein<br />

de sa propre famille. Cette situation ne va pas sans friction. Néanmoins,<br />

jusqu’à sa mort, Tourgueniev vivra la majeure partie du temps aux côtés de<br />

Louis et de Pauline. C’est un ménage à trois compliqué dont plusieurs<br />

romans de Tourgueniev et sa pièce Un mois à la campagne se font l’écho. Dans<br />

sa biographie de Pauline Viardot, The Price of Genius (« Le prix du génie »),<br />

April Fitzlyon note que l’héroïne de Tourgueniev est la plupart du temps une<br />

femme mariée. « Elle est presque toujours rapace, autoritaire, égoïste,<br />

dangereuse et séduisante ; elle fait rarement le bonheur de ceux qui l’aiment<br />

et domine presque toujours. »<br />

Tourgueniev passe sans aucun doute ses plus heureuses années chez les<br />

Viardot, à Baden-Baden et, plus tard, après la guerre franco-prussienne et la<br />

dissolution du Second Empire, à Paris et à Bougival, où il meurt en 1883.<br />

Tourgueniev écrit le livret de trois opérettes de Pauline Viardot (Trop de<br />

femmes, L’Ogre et Le Dernier Sorcier) destinées à être chantées, non pas à<br />

l’opéra, mais chez soi par des amateurs. Certains amis russes conformistes se<br />

disent alors choqués de voir Tourgueniev participer parfois à ces<br />

représentations. Néanmoins aucune critique à l’endroit de Pauline ne le<br />

touche tant il est heureux à l’idée que tout, au plus profond de lui-même, le<br />

lie à elle : « si je suis un arbre, vous êtes en même temps mes racines et ma<br />

couronne. »<br />

–28–

Il aura fallu attendre près d’un siècle après sa mort pour que musiciens et<br />

mélomanes redécouvrent la musique de Pauline Viardot. Dès l’adolescence<br />

Pauline a composé des mélodies et des pièces pour piano ; celles-ci firent<br />

parfois l’objet de publications tardives, d’où certaines difficultés à dater<br />

nombre d’entre elles. Viardot ne se considérait pas, dit-on, comme un<br />

compositeur. Néanmoins, dans ce domaine à prédominance masculine, sa<br />

production est supérieure à celle de la plupart de ses contemporaines. À Paris,<br />

pendant sa jeunesse, la mode est à la romance et la chansonnette, qui<br />

occupent alors une place prépondérante dans l’édition musicale. À travers<br />

Schumann, et plus tard Gounod, Berlioz, Tchaïkovski et Fauré, elle voit le<br />

chant se transformer en un art à part entière. L’œuvre de différents poètes,<br />

dont Mörike, Lermontov et Tourgueniev, jalonne son parcours. Enfant, elle<br />

a rencontré Lorenzo Da Ponte, le librettiste de Mozart ; elle a vécu assez<br />

longtemps pour connaître la musique de Debussy et de Strauss. Toute<br />

l’histoire musicale du XIX e siècle se trouve, à bien des égards, résumée dans<br />

la vie de Pauline Viardot.<br />

–29–<br />

© Patrick O’Connor, 2007<br />

Traduction : Mireille Ribière

Pauline Viardot<br />

in the title role of<br />

Lully’s Alceste

PAULINE VIARDOT – Chronologie<br />

1821 Geboren als Pauline García am 18. Juli in Paris als jüngstes Kind von<br />

Manuel García (1775-1832) und seiner zweiten Frau Joaquina<br />

García (1780-1854).<br />

1825 Die Familie García reist nach Amerika und gibt in New York die<br />

ersten amerikanischen Aufführungen von Rossini- und Mozart-<br />

Opern, u.a. Don Giovanni. Begegnung mit Lorenzo Da Ponte. Maria<br />

García lernt Eugène Malibran kennen und heiratet ihn.<br />

1832 Beginn des Klavierunterrichts bei Liszt.<br />

1834 Auftritt als Pianistin bei Konzerten mit Schwester Maria und Charles<br />

de Bériot.<br />

1836 Tod Maria Malibrans.<br />

1839 Pauline Garcías Bühnendebüt als Desdemona in Rossinis Otello in<br />

London, Her Majesty’s. Debüt in Paris, Odéon.<br />

1840 Heirat mit Louis Viardot.<br />

1841 Debüt in Wien als Rosina in Il barbiere di Siviglia.<br />

–31–

1843 Debüt in St. Petersburg, Begegnung mit Turgenjew.<br />

1844 Zweite Spielzeit in Russland, Debüt als Norma.<br />

1848 Konzertauftritte in London mit Chopin, singt eigene Arrangements<br />

seiner Mazurken.<br />

1849 Singt bei der Uraufführung von Meyerbeers Le prophète am 16. April<br />

in der Pariser Opéra die Rolle der Fidès.<br />

1851 Titelrolle bei der Uraufführung von Gounods Sapho am 16. März in<br />

Paris, Opéra.<br />

1855 Singt bei der ersten Londoner Aufführung von Verdis Il trovatore die<br />

Azucena.<br />

1859 Lady Macbeth in Verdis Oper in Dublin und Manchester.<br />

1859 Titelrolle in Berlioz’ Bearbeitung von Glucks Orphée in Paris, Théatre<br />

Lyrique.<br />

1860 Singt bei einer privaten Aufführung des 2. Akts von Tristan und Isolde<br />

die Isolde, mit Wagner als Tristan.<br />

1861 Glucks Alceste, Paris, Opéra.<br />

–32–

1869 Viardots Le dernier sorcier wird in Weimar aufgeführt.<br />

1870 Gibt erste Aufführung von Brahms’ Alt-Rhapsodie, Jena.<br />

1873 Singt Massenets Marie Magdeleine, Paris, Odéon.<br />

1874 Singt die Dalila bei einer privaten Aufführung des 1. und 2. Akts von<br />

Samson et Dalila, begleitet von Saint-Saëns.<br />

1876 Tod George Sands.<br />

1883 Tod von Louis Viardot und Iwan Turgenjew.<br />

1889 Begegnung mit Tschaikowski in Paris, dem sie die handschriftliche<br />

Partitur von Mozarts Don Giovanni zeigt, die sie später dem Pariser<br />

Konservatorium überlässt.<br />

1901 Auszeichnung mit der Légion d’Honneur durch die französische<br />

Regierung.<br />

1910 Tod Pauline Viardots am 18. Mai.<br />

–33–

PAULINE VIARDOT 1821–1910<br />

HECTOR BERLIOZ schrieb einmal über eine Aufführung Pauline<br />

Viardots: „All ihre Posen, ihre Gesten, ihre Ausdrücke … sind von tiefstem<br />

Kunstverständnis durchdrungen. Was die Vollkommenheit ihres Gesangs,<br />

das überragende Geschick ihrer Stimmgebung, ihre musikalische Sicherheit<br />

betrifft, so werden sie von jedermann anerkannt und bewundert … Madame<br />

Viardot ist eine der größten Künstlerinnen … der früheren und<br />

gegenwärtigen Musikgeschichte.“<br />

Pauline Viardots Ruf überdauerte Jahrzehnte, auch nachdem sie sich von<br />

der Bühne zurückgezogen hatte. Wie bei ihrer älteren Schwester Maria<br />

Malibran verband man auch mit ihrem Namen ein romantisches Ideal, ein<br />

Streben nach Vollkommenheit, das in der Mitte des 19. Jahrhunderts die<br />

modernen Schriftsteller und Freidenker ungemein ansprach.<br />

Pauline entstammte einer Familie von Musikern und Schauspielern und<br />

wuchs praktisch hinter den Kulissen auf. Ihr Vater Manuel García wurde<br />

1775 in Sevilla geboren und erhielt an der dortigen Kathedrale eine<br />

Ausbildung zum Chorknaben. Nachdem er dem Messer entronnen war,<br />

entwickelte er sich zu einem gerühmten Tenorsolisten. Nicht minder<br />

erfolgreich war er als Komponist, viele seiner Werke kamen in Madrid zur<br />

Aufführung, wo er am Teatro del Principe als Haus-Komponist tätig war. In<br />

erster Ehe war er mit der Sopranistin Manuela Morales verheiratet, mit der<br />

er zwei Töchter hatte, doch 1807 zog er mit der Sängerin Joaquina Briones<br />

–34–

nach Paris; sie wurde später seine zweite Frau und die Mutter seiner drei<br />

berühmten Kinder Manuel, Maria und Pauline.<br />

García interpretierte erstmals die Rolle des Norfolk in Rossinis Elisabetta,<br />

regina d’Inghilterra und später die des Almaviva in Il barbiere di Siviglia. Er<br />

wurde in Italien, Frankreich und England gefeiert und galt als bedeutendster<br />

Interpret von Rossinis Otello. 1826 reiste García mit seiner Familie und einer<br />

kleinen Truppe nach Amerika, wo sie mehrere italienische Opern zur<br />

Erstaufführung brachten. So sang er mit seinem Sohn als Figaro und seiner<br />

Tochter Maria als Rosina wieder den Almaviva. Lorenzo Da Ponte, der zu der<br />

Zeit an der Columbia University lehrte, überredete ihn, Don Giovanni zu<br />

inszenieren, und somit erlebte diese Mozart-Oper ihre US-amerikanische<br />

Premiere in Anwesenheit des Librettisten.<br />

Als Maria die Familie verließ, um ihren ersten Mann Eugène Malibran zu<br />

heiraten, unternahmen die Garcías ohne ihre Primadonna eine Tournee<br />

durch Mexiko. Zu Paulines lebhaftesten Kindheitserinnerungen gehört ein<br />

Überfall, bei dem die Reisegruppe von Banditen ausgeraubt wurde und ihr<br />

ganzes Hab und Gut, inklusive des Geldes, verlor. Nach der Rückkehr nach<br />

Europa begann García, dessen Stimme mittlerweile versagte, zu unterrichten;<br />

zu seinen Schülern gehörten Größen wie Adolphe Nourrit, Henriette Méric-<br />

Lalande (Donizettis erste Lucrezia Borgia) und später auch Pauline.<br />

Allerdings war sie erst elf, als ihr Vater starb, und nach dem frühen Tod Maria<br />

Malibrans beschloss Mme. García, dass Pauline, die von einer Karriere als<br />

Pianistin träumte und eine Weile Unterricht von Liszt bekommen hatte, sich<br />

auf Gesang verlegen sollte.<br />

–35–

Ihr Debüt gab sie als Desdemona in Rossinis Oper Otello, in der ihr Vater<br />

und ihre Schwester brilliert hatten, und war sofortig ein durchschlagender<br />

Erfolg. Nachdem sie den Antrag des Dichters Alfred de Musset abgelehnt<br />

hatte, heiratete sie mit 19 Jahren Louis Viardot, den Leiter des Théâtre Italien<br />

in Paris. Diese Stelle gab er auf, um sich ihrer Karriere zu widmen.<br />

Die Triumphe, die Pauline Viardot feierte, waren nicht minder groß als die<br />

ihrer Schwester, ob in London, Paris, Wien, Berlin und insbesondere in St.<br />

Petersburg. In Italien selbst trat sie offenbar nie auf – womöglich wegen einer<br />

Rivalität mit Giulia Grisi, obwohl die beiden Sängerinnen gemeinsam in<br />

Rossinis Semiramide und Bellinis I Capuleti e i Montecchi auftraten.<br />

Dank ihrer Sprachkenntnis konnte Pauline Viardot bereits in jungen<br />

Jahren einen großen Freundes- und Bekanntenkreis aufbauen, der später die<br />

intellektuelle und musikalische Elite Europas bildete. Chopin, Liszt, Berlioz,<br />

Gounod, Meyerbeer, Saint-Saëns, Schumann und Fauré komponierten<br />

Werke für sie oder widmeten ihr Musikstücke. Alfred de Musset, Flaubert,<br />

Dickens, Delacroix und selbst der junge Henry James gehörten zu ihren<br />

Bewunderern, doch die für sie wichtigsten Freundschaften hatte sie mit den<br />

Schriftstellern George Sand und Iwan Turgenjew.<br />

George Sand lernte Pauline kurz nach deren Pariser Debüt 1839 kennen.<br />

Im folgenden Jahr schrieb Sand einen ausführlichen, positiven Artikel über<br />

die junge Sängerin, und bald war Pauline ein geschätztes Mitglied der<br />

Gruppe, die in George Sands Landhaus in Nohant eingeladen wurde. Die<br />

Schriftstellerin lehnte die Hauptfigur ihres Romans Consuelo an Pauline an.<br />

–36–

Auch wenn er im 18. Jahrhundert spielt, war die Protagonistin, eine<br />

spanische Sängerin, für den Freundeskreis unverkennbar:<br />

„Das blasse, stille Gesicht – fast leblos, wie man auf den ersten Blick<br />

meinen könnte –, die geschmeidigen, ungezwungenen Bewegungen,<br />

der erstaunliche Mangel an jeder Art von Gehabe – wie verändert und<br />

erleuchtet erscheint das alles, wenn sie sich auf den Flügeln des<br />

Gesangs von ihrem Genie forttragen lässt.“<br />

Und wie klang Pauline Viardots Stimme? Heute würde man sie als<br />

Mezzosopranistin bezeichnen; das Repertoire, das sie sang – die Heldinnen<br />

Rossinis, Bellinis und auch Donizettis, bisweilen Mozart (Zerlina und<br />

Donna Anna) und dann später Opern von Meyerbeer, Gounod und Verdi –<br />

geben uns eine Ahnung davon. Ihren größten Erfolg hatte sie mit Berlioz’<br />

Bearbeitung von Glucks Orphée, eine Rolle, die sie 150 Mal sang. Der<br />

Kritiker Henry Chorley schrieb:<br />

„Durch die eigentümliche Qualität ihrer Stimme – ihre<br />

Unebenheit, die gelegentliche Schroffheit und Schwäche gepaart mit<br />

Klängen zartester Sanftheit – verstand Mme. Viardot es, mit selten<br />

glücklicher Fügung jedem Wort eines Monologs, jeder Wendung<br />

eines Dialogs Licht und Schatten zu verleihen.“<br />

Als Pauline Viardot ihren Abschied von der Bühne nahm, tat sie es als<br />

Orphée. Damals war sie 42 Jahre alt (und damit fast im selben Alter, in dem<br />

Maria Callas sich zurückzog).<br />

–37–

1862 zogen die Viardots als entschiedene Gegner des Regimes von<br />

Napoleon III. aus Paris fort und ließen sich in Baden-Baden nieder. Dort<br />

gesellte sich Turgenjew zu ihnen, der in Pauline verliebt war, seit er sie in den<br />

1840er Jahren in St. Petersburg kennen gelernt hatte. Zwar waren sie seitdem<br />

nicht ununterbrochen in Kontakt gewesen, aber Pauline hatte Turgenjews<br />

illegitime Tochter zu sich geholt und mit ihren eigenen Kindern erzogen. Das<br />

führte unvermeidlich zu gewissen Spannungen, dennoch verbrachte<br />

Turgenjew fast den ganzen Rest seines Lebens mit Louis und Pauline. Diese<br />

komplizierte Ménage-à-trois kommt in mehreren Romanen des russischen<br />

Schriftstellers vor, aber auch in seinem Drama Ein Monat auf dem Lande. In<br />

The Price of Genius, ihrer Biografie von Pauline Viardot, schreibt April<br />

Fitzlyon, dass Turgenjews Heldinnen vielfach verheiratete Frauen sind. „Sie<br />

sind fast immer raubgierig, herrisch, selbstsüchtig, gefährlich attraktiv, ganz<br />

selten machen sie den Mann glücklich, der sie liebt, fast immer dominieren<br />

sie ihn.“<br />

Turgenjew verbrachte zweifellos die glücklichste Zeit seines Lebens bei den<br />

Viardots, ob nun in Baden-Baden oder später, nach dem deutschfranzösischen<br />

Krieg und dem Ende des Zweiten Kaiserreichs, in Paris und in<br />

Bougival, wo er 1883 starb. Turgenjew schrieb für Paulines Operetten drei<br />

Libretti. Diese Werke waren nicht für eine öffentliche Aufführung gedacht<br />

sondern vielmehr für Amateurdarbietungen im häuslichen Kreis (Trop de<br />

femmes, L’ogre und Le dernier sorcier). Einige von Turgenjews konservativen<br />

russischen Freunden zeigten sich entsetzt, dass er bisweilen bei diesen<br />

Aufführungen mitwirkte. Doch wenn es um Pauline ging, ließ Turgenjew<br />

–38–

keine Kritik gelten, und schrieb ihr: „Der Gedanke beglückt mich, dass alles,<br />

alles in mir bis in die tiefsten Tiefen mit deinem Wesen verbunden und auf<br />

dich angewiesen ist. Wenn ich ein Baum bin, so bist du meine Wurzeln und<br />

meine Krone.“<br />

Nach ihrem Tod dauerte es nahezu hundert Jahre, bis Musiker und Zuhörer<br />

sich für ihre Musik zu interessieren begannen. Pauline Viardot hatte bereits als<br />

junges Mädchen Lieder und Klavierstücke komponiert, einige wurden lange<br />

nach ihrer Entstehung veröffentlicht, so dass sie vielfach schwer zu datieren<br />

sind. Pauline Viardot verstand sich selbst nicht als Komponistin, oder so<br />

behauptete sie zumindest, doch erreichte sie in dieser von Männern<br />

beherrschten Domäne mehr als die meisten ihrer Zeitgenossinnen. Während<br />

ihrer Jugend in Paris gab in Musikverlagen die Vorliebe für romances und<br />

chansonnettes den Ton an. Durch die Bekanntschaft mit Schumann und später<br />

mit Gounod, Berlioz, Tschaikowski und Fauré erlebte Pauline Viardot, wie das<br />

Genre des Lieds zu einer eigenständigen Kunstform wurde. Die Wahl ihrer<br />

Dichter, darunter Mörike, Lermontow und Turgenjew, spiegelt den Lauf ihres<br />

Lebens wider. Als Kind hatte sie Lorenzo Da Ponte kennen gelernt, Mozarts<br />

Librettisten, sie lebte lange genug, um noch die Musik Debussys und Strauss’<br />

zu hören. So subsumiert Pauline Viardots Leben in vieler Hinsicht die<br />

Musikgeschichte des ganzen 19. Jahrhunderts.<br />

–39–<br />

© Patrick O’Connor, 2007<br />

Übersetzt von Ursula Wulfkamp

Pauline Viardot

PAULINE VIARDOT – Cronologia<br />

1821 Pauline García, ultima figlia di Manuel (1775-1832) e di Joaquina, sua<br />

seconda moglie (1780-1854), nasce a Parigi, il 18 luglio.<br />

1825 I García si recano a New York, dove allestiscono le prime<br />

rappresentazioni statunitensi delle opere di Rossini e Mozart, tra cui<br />

Don Giovanni, e fanno la conoscenza di Lorenzo Da Ponte. Maria<br />

García incontra e sposa Eugène Malibran.<br />

1832 Pauline comincia a studiare pianoforte con Liszt.<br />

1834 Al pianoforte esegue concerti con la sorella Maria e Charles de Bériot.<br />

1836 Muore Maria Malibran.<br />

1839 Pauline García debutta in teatro nel ruolo di Desdemona nell’Otello di<br />

Rossini, al teatro Her Majesty’s di Londra; esordio all’Odéon di Parigi.<br />

1840 Pauline sposa Louis Viardot.<br />

1841 Esordisce a Vienna cantando Rosina nel Barbiere di Siviglia.<br />

1843 Esordio a San Pietroburgo; primo incontro con Turgenev.<br />

–41–

1844 Seconda stagione russa, esordio nel ruolo di Norma.<br />

1848 A Londra si esibisce in concerto con Chopin, interpretandone le<br />

mazurche arrangiamenti composti da lei.<br />

1849 Crea il ruolo di Fidès nell’opera di Meyerbeer Le prophète, Opéra di<br />

Parigi, 16 aprile.<br />

1851 Protagonista alla prima della Sapho di Gounod, Opéra di Parigi, 16<br />

marzo.<br />

1855 Azucena nel primo allestimento londinese del Trovatore di Verdi.<br />

1859 Lady Macbeth nell’opera di Verdi a Dublino e Manchester.<br />

1859 Protagonista nell’edizione di Berlioz dell’Orphée di Gluck al Théâtre<br />

Lyrique di Parigi.<br />

1860 Isolde in alcune esecuzioni private dell’Atto 2 del Tristan und Isolde di<br />

Wagner. Il compositore interpreta Tristan.<br />

1861 Alceste di Gluck, Opéra di Parigi.<br />

1869 Le dernier sorcier della Viardot allestito a Weimar.<br />

–42–

1870 Prima interprete della Rapsodia per Contralto di Brahms a Jena.<br />

1873 Marie Magdeleine di Massenet, Odéon di Parigi.<br />

1874 Dalila in spettacoli privati degli Atti 1 e 2 di Samson et Dalila,<br />

accompagnata da Saint-Saëns.<br />

1876 Morte di George Sand.<br />

1883 Morte di Louis Viardot e Ivan Turgenev.<br />

1889 Pauline Viardot conosce aikovskij a Parigi e gli mostra la partitura<br />

manoscritta del Don Giovanni di Mozart, da lei successivamente donata<br />

al Conservatorio di Parigi.<br />

1901 Riceve la Légion d’Honneur dal governo francese.<br />

1910 Pauline Viardot muore il 18 maggio.<br />

–43–

PAULINE VIARDOT 1821–1910<br />

ECCO COME Hector Berlioz descrisse una delle esibizioni di Pauline<br />

Viardot: “Tutti i suoi atteggiamenti, i suoi gesti, le sue espressioni…sono<br />

studiati con profonda arte. Per quanto riguarda la perfezione del suo canto,<br />

l’estrema capacità della vocalizzazione, la sicurezza musicale – si tratta di cose<br />

note e apprezzate da tutti… Madame Viardot è una delle più grandi artiste …<br />

nella storia della musica, ieri e oggi.”<br />

La reputazione di Pauline Viardot sopravvisse per decenni dopo il suo addio<br />

alle scene. Il suo nome, come quello della sorella maggiore, Maria Malibran,<br />

finì per essere associato a un ideale romantico, a un anelito alla perfezione che<br />

si attagliava alla perfezione agli scrittori moderni e ai liberi pensatori della metà<br />

dell’Ottocento.<br />

Figlia d’arte, Pauline crebbe tra le quinte dei teatri. Suo padre, Manuel<br />

Garcia, nato a Siviglia nel 1775, era stato corista nella cattedrale della sua città.<br />

Essendo sfuggito al destino di castrato, divenne un abile tenore solista. Le sue<br />

composizioni ebbero altrettanto, se non maggiore successo, e molte furono<br />

eseguite a Madrid, dove García divenne uno dei compositori residenti al Teatro<br />

del Principe. Sposato in prime nozze con il soprano Manuela Morales, da cui<br />

ebbe due figlie, nel 1807 si trasferì a Parigi, accompagnato dalla cantante<br />

Joaquina Briones, che infine sposò in seconde nozze e che gli diede tre famosi<br />

figli: Manuel, Maria e Pauline.<br />

–44–

García creò i ruoli di Norfolk nell’Elisabetta, regina d’Inghilterra di Rossini e<br />

in seguito quello di Almaviva nel Barbiere di Siviglia. Famoso in Italia, Francia<br />

e Inghilterra, fu considerato il più grande interprete dell’Otello di Rossini. Nel<br />

1826 si recò in America, con la famiglia e una piccola compagnia, e a New<br />

York diede le prime interpretazioni delle opere italiane. Con il figlio nel ruolo<br />

di Figaro e la figlia Maria nelle vesti di Rosina, García cantò ancora una volta<br />

Almaviva. Lorenzo Da Ponte, che allora insegnava presso la Columbia<br />

University, li sollecitò ad allestire Don Giovanni, e così l’opera di Mozart<br />

ricevette la sua prima statunitense alla presenza del librettista.<br />

Quando Maria lasciò i genitori per sposare il primo marito, Eugène<br />

Malibran, la famiglia, ormai senza primadonna, intraprese una tournée in<br />

Messico. Uno dei ricordi più vividi dell’infanzia di Pauline fu un agguato in<br />

cui i viaggiatori furono aggrediti dai banditi e derubati di tutto. Al loro ritorno<br />

in Europa, avendo ormai praticamente perso la voce, García si dedicò<br />

all’insegnamento. Tra suoi allievi ci furono nomi famosi come Adolphe<br />

Nourrit, Henriette Méric-Lalande (la prima Lucrezia Borgia di Donizetti) e<br />

infine la stessa Pauline, che aveva appena 11 anni quando il padre morì. Nel<br />

1836, dopo la prematura morte di Maria Malibran, la madre decise che<br />

Pauline, ormai avviata alla carriera di pianista, avendo studiato per qualche<br />

tempo con Liszt, si dedicasse invece allo studio del canto.<br />

L’esordio fu nel ruolo di Desdemona nell’Otello di Rossini, un’opera ormai<br />

strettamente legata ai nomi del padre e della sorella, e Pauline riscosse<br />

immediato successo. All’età di 19 anni respinse il poeta Alfred de Musset e<br />

–45–

sposò Louis Viardot, direttore del Théâtre Italien di Parigi, il quale abbandonò<br />

il suo posto per dedicarsi alla carriera della moglie.<br />

Come sua sorella, Pauline Viardot ebbe grandi trionfi a Londra, Parigi,<br />

Vienna, Berlino e soprattutto a San Pietroburgo, ma non cantò mai in Italia,<br />

forse a causa della grande rivalità che si era creata per qualche tempo con<br />

Giulia Grisi, anche se entrambe le cantanti apparvero insieme nella<br />

Semiramide di Rossini e nei Capuleti e Montecchi di Bellini.<br />

Raffinata poliglotta, fin dall’adolescenza Pauline Viardot si creò una vasta<br />

cerchia di amicizie e conoscenze che avrebbero costituito l’élite intellettuale e<br />

musicale d’Europa. Chopin, Liszt, Berlioz, Gounod, Meyerbeer, Saint-Saëns,<br />

Schumann e Fauré composero opere per lei o gliele dedicarono. Alfred de<br />

Musset, Flaubert, Dickens, Delacroix, persino il giovane Henry James furono<br />

suoi ammiratori, ma i suoi più grandi amici furono George Sand e Ivan<br />

Turgenev.<br />

George Sand conobbe Pauline poco dopo il suo debutto parigino nel 1829.<br />

L’anno successivo scrisse un lungo articolo di elogi sulla giovane cantante e ben<br />

presto Pauline divenne una componente apprezzata del gruppo di persone<br />

invitate nella casa di campagna di George Sand a Nohant. La scrittrice si ispirò<br />

a lei per l’eroina di Consuelo. Sebbene il romanzo fosse ambientato nel<br />

Settecento, la protagonista, una cantante spagnola, era facilmente<br />

riconoscibile:<br />

–46–

“Il volto pallido, immobile – a prima vista, si direbbe ordinario – i<br />

movimenti affabili e spontanei, straordinariamente liberi da affettazioni<br />

d’ogni sorta, tutto si trasfigura e s’illumina quando il suo genio la<br />

trasporta lungo la corrente del canto.”<br />

Com’era la voce della Viardot? Oggi sarebbe definita un mezzosoprano: ne<br />

offre una discreta idea il suo repertorio, che comprende le eroine di Rossini,<br />

Bellini e anche Donizetti, un po’ di Mozart (Zerlina e Donna Anna), e poi<br />

opere più tarde di Meyerbeer, Gounod e Verdi. Il suo più grande trionfo fu<br />

l’Orphée di Gluck nell’edizione di Berlioz, una parte che cantò 150 volte. Il<br />

critico Henry Chorley scrisse:<br />

“La qualità peculiare della voce di Madame Viardot – la sua<br />

irregolarità, la sua occasionale asprezza e debolezza, che si accompagna<br />

a toni della più delicata dolcezza – fu rivolta da lei a proprio vantaggio<br />

con rara felicità d’espressione e varietà di chiaroscuri in ogni parola dei<br />

soliloqui, in ciascun richiamo del dialogo.”<br />

Quando Pauline Viardot decise di ritirarsi, il suo addio alle scene a Parigi fu<br />

nelle vesti di Orphée: aveva 42 anni (quasi l’età di Maria Callas quando anche<br />

lei si ritirò).<br />

Nel 1862 i coniugi Viardot, risolutamente contrari al regime di Napoleon<br />

III, lasciarono Parigi e si stabilirono a Baden-Baden. Qui li raggiunse Turgenev,<br />

che si era innamorato di Pauline a prima vista a San Pietroburgo nel decennio<br />

–47–

del 1840. Sebbene ci fossero stati periodi in cui non si erano tenuti in contatto,<br />

Pauline aveva accolto la figlia illegittima di Turgenev e l’aveva allevata con la<br />

propria famiglia. Questo portò inevitabilmente a numerosi contrasti.<br />

Ciononostante, Turgenev visse per la maggior parte del resto della sua vita con<br />

Louis e Pauline. Il complicato ménage-à-trois trova eco in diversi romanzi di<br />

Turgenev e nel suo dramma Un mese in campagna. Nella sua biografia di<br />

Pauline Viardot, The Price of Genius, April Fitzlyon scrisse che la caratteristica<br />

eroina di Turgenev era una donna sposata: “Sono quasi sempre sfruttatrici,<br />

prepotenti, egoiste, pericolosamente attraenti; non fanno quasi mai felici gli<br />

uomini che le amano, vogliono quasi sempre dominarli.”<br />

Per Turgenev gli anni più felici furono indubbiamente quelli trascorsi nelle<br />

residenze dei Viardot a Baden-Baden o in seguito, dopo la guerra francoprussiana<br />

e la dissoluzione del secondo Impero, a Parigi e Bougival, dove morì<br />

nel 1883. Turgenev scrisse tre libretti per le operette di Pauline, destinate non<br />

al teatro, ma alle abitazioni degli attori dilettanti (Trop de femmes, L’ogre e Le<br />

dernier sorcier). Alcuni suoi amici conservatori finsero di scandalizzarsi del fatto<br />

che lo scrittore prendesse parte occasionalmente a queste rappresentazioni, ma<br />

Turgenev era ignaro delle critiche per quanto riguardava Pauline e le scrisse:<br />

“Sono così felice al pensiero che tutto, tutto in me fino alle maggiori<br />

profondità, sia collegato con il vostro essere e dipenda da voi. Se sono un<br />

albero, voi siete le mie radici e la mia corona.”<br />

È passato più di un secolo dalla morte di Pauline Viardot prima che artisti e<br />

ascoltatori si interessassero alla sua musica. Fin dall’adolescenza, Pauline aveva<br />

–48–

composto canzoni e brani per pianoforte. Alcuni furono pubblicati molto<br />

tempo dopo essere stati composti e le date di molti sono oggetto di congettura.<br />

Sebbene pare che la Viardot non si considerasse una compositrice, si impose<br />

più di tante altre donne del suo tempo lavorando in questa sfera dominata<br />

dagli uomini. Crebbe a Parigi, dove la moda delle romances e chansonnettes<br />

dominava le case editrici di partiture vocali. Attraverso i suoi contatti con<br />

Schumann e successivamente Gounod, Berlioz, Tchaikovskij e Fauré, la<br />

cantante vide l’intero concetto di canzone trasformarsi in un’arte a sé. I poeti<br />

che scelse, tra cui Mörike, Lermontov e Turgenev, seguono la traiettoria della<br />

sua vita. Da bambina aveva conosciuto il librettista di Mozart, Lorenzo Da<br />

Ponte; visse abbastanza a lungo da conoscere la musica di Debussy e Strauss.<br />

Per molti versi, la vita di Pauline Viardot riassume l’intera storia della musica<br />

nel XIX secolo.<br />

–49–<br />

© Patrick O’Connor, 2007<br />

Traduzione: Emanuela Guastella

Fanny Ardant (narrator)

CD 1 37’56<br />

Pauline Viardot<br />

Poem by Afanasi Fet<br />

‘Дв е розы’Dve rozy (Two roses) [CD 1 Track 2]<br />

(pub. 1864 Russia, 1866 France)<br />

VLADIMIR CHERNOV<br />

WHEN PAULINE VIARDOT first appeared in Russia, she helped to win the<br />

hearts of her new audience by learning Russian, and singing in the language of<br />

her listeners. After the interval of one performance of Il barbiere di Siviglia, she<br />

and her colleagues Rubini and Tamburini joined with a local choir to sing<br />

‘God Save the Tsar’. After 1850, Viardot never returned to Russia, but she<br />

always felt close to the country where she had received such an extravagantly<br />

warm reception. This song, one of a group in Russian that she published in<br />

1864, is a setting of a poem by Afanasi Afanesevich Fet (real name Shenshin,<br />

1820-92) who came to know the Viardots well (see CD 1 Track 15).<br />

Пол н оспать! Тебедв е розы Enough of sleeping: it’s daybreak<br />

Polno spat’! Tebe dve rozy<br />

Япринёссрассветом дня. And I’ve brought you two roses<br />

Ya prinës s rassvetom dnia.<br />

Сквозь сереб ряныесл ёзы The delight of their fire<br />

Skovz’ serebriannye slëzy<br />

Ярченега их огн я. Seems brighter through silver tears.<br />

Yarche nega ikh ognia.<br />

–51–

Vladimir Chernov

Веш нихдн ей минутн ы грозы , Spring thunderstorms are brief,<br />

Veshnikh dnei minutny grozy<br />

Воздух чист, свежей листы … The air is clean, the leaves fresh...<br />

Vozkukh chist, svezhei listy.<br />

И роняю ттихо слёзы And quiet tears fall<br />

I roniaiut tikho slëzy<br />

Аром атн ыецветы . From the fragrant flowers.<br />

Aromatnye tsvety.<br />

Manuel García<br />

Poem by Louis Pomey (?)<br />

‘Celos’ (Jealousy) [CD 1 Track 4]<br />

Arr. Pauline Viardot, dedicated to George Sand<br />

ANNA CATERINA ANTONACCI<br />

VIARDOT’S FATHER, whose full name was Manuel del Populo Vicente<br />

Rodríguez García, was born in Seville in 1775. During the first half of his<br />

remarkable career, he was equally renowned as a composer and singer. He<br />

wrote stage works in Spanish, Italian and French. His songs continued to be<br />

sung by both his daughters, indeed both of them would insert his aria ‘Yo que<br />

soy contrabandista’ from El poeta calculista in the lesson scene in Act 2 of<br />

Rossini’s Il barbiere di Siviglia. In 1830 he published a collection of Spanish<br />

songs, and this arrangement by Pauline of one of his songs in the Andalusian<br />

manner is her own tribute to the genius of her father. ‘He believed neither in<br />

God nor in the Devil,’ she said. ‘His own religion was life, with all its most<br />

ardent passions, it was art, it was love!’<br />

–53–

Anna Caterina Antonacci

¿Qué quieres Panchito What do you want me to think,<br />

que me piense yo, Panchito?<br />

que me piense yo? What do you want me to think,<br />

¿Qué quieres Panchito Panchito?<br />

que me piense yo?<br />

Si te vi ayer tarde I saw you late yesterday<br />

al dar la oración during prayer<br />

con una señora in conversation<br />

en conversación, with a woman.<br />

en conversación.<br />

Si te vi ayer tarde I saw you late yesterday<br />

al dar la oración, during prayer.<br />

al dar la oración,<br />

al dar la oración.<br />

¿Qué quieres Panchito What do you want me to think,<br />

que me piense yo, Panchito?<br />

que me piense yo?<br />

Si seguí tus pasos I followed you and saw<br />

y vi con dolor to my pain<br />

que la dabas pruebas that you gave her proof<br />

de un constante amor. of constant love.<br />

–55–

Gioachino Rossini<br />

(1792-1868)

¿Qué quieres Panchito What do you want me to think,<br />

que me piense yo, Panchito?<br />

que me piense yo?<br />

Si después de todo If, after all we have been through,<br />

te pido un favor I ask you a favour<br />

y tu me lo niegas and you, full of rage,<br />

lleno de furor, deny me this.<br />

lleno de furor.<br />

¿Qué quieres Panchito What do you want me to think,<br />

que me piense yo, Panchito?<br />

que me piense yo,<br />

que me piense yo,<br />

que me piense yo?<br />

Gioachino Rossini<br />

Poem by G. Pepoli<br />

‘La regata veneziana’ (The Venetian regatta) [CD 1 Track 6]<br />

FREDERICA VON STADE & ANNA CATERINA ANTONACCI<br />

ROSSINI HAD known Pauline since she was an infant. Just as her father and<br />

sister had triumphed in his operas, so many of Pauline’s early successes were in<br />

Rossini roles – Desdemona, Rosina, Cenerentola and Ninetta (in La gazza<br />

ladra). When they were both living in Paris in the 1850s, Pauline frequented<br />

Rossini’s musical evenings at his house in the rue Chausée d’Antin. ‘La regata<br />

veneziana’ is one of the duets from Rossini’s collection Les soirées musicales,<br />

–57–

Frederica von Stade

composed in the early 1830s, just after he had written his final opera,<br />

Guillaume Tell. Much later, he wrote a sequence of songs about the regatta, in<br />

the Album italiano of his Péchés de vieillesse (Sins of old age).<br />

Voga o Tonio benedeto Row, O Tonio, my good man,<br />

Voga, voga, arranca, arranca: row, row, harder, harder:<br />

Beppe el suda, el batte l’anca Beppe is sweating, losing heart,<br />

Poverazzo el nol pò più, poor devil, he can’t go on,<br />

Voga, voga, voga su! row, row, keep rowing!<br />

Caro Beppe el me vecchieto Dear old Beppe,<br />

No straccarte col te remo; don’t exhaust yourself rowing:<br />

Za ghe semo, spinze, daghe, you’re almost there, almost<br />

voga più. there, pull harder!<br />

Ziel pietoso una novizza Good heavens, your future bride,<br />

C’ha el so ben nella regada, as you well know is expecting you<br />

at the finish<br />

Fala o zielo consolada, make her happy, for goodness sake,<br />

No la far stentarde più don’t make her suffer anymore!<br />

Voga o Tonio benedeto ... Row, O Tonio, my good man ...<br />

–59–

Pauline Viardot<br />

Text anonymous<br />

‘L’absence’ (Absence) [CD 1 Track 8]<br />

(pub. 1844)<br />

FREDERICA VON STADE<br />

PUBLISHED JUST after the first of Viardot’s Russian seasons, this has a<br />

decidedly Spanish feel to it – is it, perhaps, another evocation of one of Manuel<br />

García’s songs? The fashion for the music of Spain took hold in Paris later,<br />

during the reign of the Emperor Napoleon III, and his Spanish wife, Eugénie<br />

de Montijo.<br />

Aux longs tourments de l’absence The only remedy for the long torment<br />

Le seul remède est mourir. of absence is to die,<br />

Dans la triste indifférence why languish so long<br />

Pourquoi si longtemps languir? in sad indifference?<br />

Sans repos, sans espérance? Without rest, without hope?<br />

Est-ce vivre que souffrir? Is to live to suffer?<br />

Aux longs tourments de l’absence The only remedy for the long torment<br />

Le seul remède est mourir. of absence is to die,<br />

Ah! ah!<br />

Lorsque je tiens ma promesse, While I keep my promise,<br />

Ingrat, de t’aimer toujours, ungrateful one, to love you always,<br />

Peut-être une autre maîtresse another mistress perhaps<br />

T’enivre d’autres amours. exalts you with other loves.<br />

C’est hélas! trop de souffrance, The suffering is too great, alas!<br />

–60–

Rehearsal for the concert at the Wigmore Hall with<br />

Fanny Ardant, David Watkin, David Harper, Anna Caterina Antonacci<br />

Frederica von Stade and Vladimir Chernov

Je sens mon coeur défaillir. I feel my heart grow weak.<br />

Ah! des tourments de l’absence Ah! the only remedy for the long torment<br />

Le seul remède est mourir. of absence is to die,<br />

Ah! ah!<br />

Pauline Viardot<br />

Poem by Auguste de Châtillon (1813-1881)<br />

‘Berceuse’ (Lullaby) [CD 1 Track 10]<br />

(pub. 1884)<br />

FREDERICA VON STADE<br />

PAULINE AND LOUIS Viardot had four children, Louise (b. 1841), Claudie<br />

(b. 1852), Marianne (b. 1853) and Paul (b. 1857). Louise was married in 1862<br />

to Ernest Héritte, a diplomat, and their son, born in 1864, made Pauline a<br />

grandmother at the age of 43. Almost to the end of her life, there was always<br />

music in Pauline’s house; her children and grandchildren visited her often, and<br />

this cradle-song was perhaps composed for one of them.<br />

Enfant, si tu dors, Child, if you’ll fall asleep,<br />

Les anges alors the angels<br />

T’apporteront mille choses: will bring you a thousand things:<br />

Des petits oiseaux, little birds,<br />

Des petits agneaux, little lambs,<br />

Des lys, des lilas et des roses, lilies, and lilacs, and roses,<br />

–62–

Puis, des lapins blancs, and then white rabbits<br />

Avec des rubans with ribbons<br />

Pour traîner ta voiture; will pull your carriage;<br />

Ils te donneront they’ll give you<br />

Tout ce qu’ils auront, everything they have<br />

Et des baisers, je t’assure! and many kisses, you’ll see!<br />

Enfant, dors à mes accords, Child, sleep to my melody,<br />

Dors, mon petit enfant, sleep, my little child,<br />

Dors! Dors, petit enfant. Sleep! Sleep, little child.<br />

J’entends l’éléphant du grand I hear the elephant of the Great<br />

Mogol Mogul<br />

Il s’avance, coming along,<br />

Portant sur son dos deux carrying on his back two closed<br />

palanquins clos, palanquins.<br />

Que lentement il balance, How slowly he ambles along,<br />

Lentement, lentement il balance! slowly, slowly ambles ...<br />

Dans les palanquins sont les In the palanquins are the white<br />

lapins blancs rabbits<br />

Qui vont traîner ta voiture... who are going to pull your carriage...<br />

Tu n’entends pas mon murmure, you don’t hear my whisper,<br />

Enfant, dors à mes accords, Child, sleep to my melody,<br />

Dors, mon petit enfant Sleep, my little child.<br />

Dors! dors! dors! dors! Sleep! Sleep! Sleep! Sleep!<br />

–63–

Pauline Viardot<br />

Fable by Jean De La Fontaine<br />

‘Le chêne et le roseau’ (The oak and the reed) [CD 1 Track 12]<br />

(pub. 1843, possibly 1841)<br />

ANNA CATERINA ANTONACCI<br />

MANY COMPOSERS have been drawn to the Fables of La Fontaine, notably<br />

Offenbach, Lecoq and Caplet, but Viardot was one of the first. ‘Le chêne et le<br />

roseau’ was first sung by Viardot at a concert in 1842, in which she was<br />

accompanied by Chopin. It has been suggested that she made the piano part<br />

more elaborate in this song in order to give the virtuoso composer something<br />

more interesting to play. It was one of the songs that Viardot chose to include<br />

in her album of eight songs, published the following year, with illustrations by<br />

Ary Scheffer, the painter she referred to as ‘a spiritual counsellor and guide’.<br />

Le Chêne, un jour, dit au Roseau: The oak one day addressed the reed:<br />

« Vous avez bien sujet d’accuser ‘You have every reason to accuse<br />

la nature, nature:<br />

Un roitelet pour vous est un a wren for you is a heavy<br />

pesant fardeau; burden;<br />

Le moindre vent, qui the slightest wind which<br />

d’aventure happens<br />

Fait rider la face de l’eau, to ripple the water’s surface<br />

Vous oblige à baisser la tête, forces you to lower your head;<br />

Cependant que mon front, au while my brow, like the<br />

Caucase pareil, Caucasus,<br />

–64–

Non content d’arrêter les rayons Not content to halt the rays of<br />

du soleil, the sun<br />

Brave l’effort, l’effort de la tempête. bravely confronts the storm.<br />

Tout vous est aquilon, tout me What to you is a North Wind is<br />

semble zéphir. to me a Zephyr.<br />

Encor si vous naissiez à l’abri if you were to grow sheltered<br />

du feuillage by the foliage<br />

Dont je couvre le voisinage, with which I cover the neighbourhood,<br />

Vous n’auriez pas tant à souffrir: you would not suffer so much:<br />

Je vous défendrais de l’orage; I would defend you from the storm.<br />

Mais vous naissez le plus souvent But you are wont to grow<br />

Sur les humides bords des by the damp borders of the<br />

royaumes du vent. winds’ realm.<br />

La nature envers vous me Nature seems most unjust<br />

semble bien injuste. » towards you.’<br />

« Votre compassion, lui répondit ‘Your compassion,’ replied the<br />

l’arbuste, little shrub,<br />

Part d’un bon naturel; mais ‘is well meant; but do not<br />

quittez ce souci: worry.<br />

Les vents me sont moins qu’à The winds are less to be feared<br />

vous redoutables; by me than you.<br />

Je plie, je plie et ne romps pas. I bend, and do not break.<br />

Vous avez jusqu’ici You have till now<br />

Contre leurs coups épouvantables resisted their fearful blows<br />

Résisté sans courber le dos; without bending your back;<br />

Mais attendons la fin. » but let’s await the end.’<br />

–65–

Comme il disait ces mots, as the reed spoke these words,<br />

Du bout de l’horizon accourt from the horizon there roared<br />

avec furie in fury<br />

Le plus terrible des enfants the fiercest child<br />

Que le nord eût portés jusque that the North Wind had ever sired.<br />

là dans ses flancs.<br />

L’arbre tient bon, le roseau plie. The tree stands fast, the reed bends;<br />

Le vent redouble ses efforts, the wind redoubles its efforts,<br />

Et fait si bien qu’il déracine with such effect that it uproots<br />

Celui de qui la tête au ciel était the tree whose crown reached<br />

voisine up to heaven,<br />

Et dont les pieds touchaient à and whose feet dwelt in the<br />

l’empire des morts. empire of the dead.<br />

Pauline Viardot<br />

Poem by Yuriy Mikhail Lermontov<br />

‘У тёс’ Utës (The Cliff) [CD 1 Track 14]<br />

(pub. 1868)<br />

VLADIMIR CHERNOV<br />

AFTER PUSHKIN, Lermontov (1814-1841) was the most influential<br />

Russian writer of the mid-19th century. The author of A Hero of Our Time,<br />

like Pushkin he had been killed in a duel, two years before Viardot’s first<br />

Russian season. This poem, written in the last year of Lermontov’s life, inspired<br />

Viardot to one of her most interesting songs. In it she seems to have captured<br />

that mixture of irony and pessimism that is characteristic of so much Russian<br />

poetry and music.<br />

–66–

Ноч евала туч к азолотая A little golden cloud spent the night<br />

Nochevala tuchka zolotaia<br />

Н а груди утёса-в ел ик ан а; Snuggled up to a great cliff.<br />

Na grudi utiosa velikana.<br />

У тром в путьона ум чалась рано, Early next morning she whirls away,<br />

Utrom v put’ ona umchalas’ rano,<br />

П о лазури в есел о играя; Happily playing in the blue skies<br />

Po lazuri veselo igraia ...<br />

Н о остал ся влажный след But a dramp trace<br />

вморщ ине<br />

No ostalsia vlazhnyi sled v morshchine<br />

Старого утёса. Одиноко Remained in a wrinkle of the old cliff.<br />

Staravo utiosa ... Odinoko<br />

Он стоит, задум ался глуб око, Lonely, the cliff stands lost in reverie<br />

On stoit zadumalsia g luboko,<br />

И тих он ько пл ач ет он в пусты н е. And quietly weeps in the desert.<br />

I tikhon’ko plachet on v pustyne.<br />

Pauline Viardot<br />

Poem by Afanasi Fet, translated by Friedrich Bodenstedt and Ivan Turgenev<br />

‘Die Sterne’ (The stars) [CD 1 Track 15]<br />

(pub. 1864)<br />

FREDERICA VON STADE, DAVID WATKIN (CELLO)<br />

IN 1856, Afanasi Fet came to join his friend Turgenev at the Viardots’ country<br />

retreat at Courtavenel. Although he did not seem to fit in with the liberal-<br />

–67–

David Watkin (cello)

minded, sophisticated circle always surrounding Pauline, Fet spent happy<br />

hours talking with Turgenev. Fet, in his memoirs (Moi Vospominaniya,<br />

Moscow, 1890) recalled the beauty of the chateau, the sunny autumn days<br />

spent walking, picking fruit, and then the evenings, always with readings, and<br />

music. Later, when he heard Pauline sing in Russian at one of her Paris<br />

concerts (Turgenev and Tolstoy were both present), he wrote: ‘That<br />

unexpected, masterly Russian singing aroused in me such rapture that I had to<br />

restrain myself from some mad escapade.’<br />

Ich starrte und stand unbeweglich, I stand and stare motionless,<br />

Den Blick zu den Sternen gewandt, my gaze turned to the stars,<br />

Und da zwischen mir und den and an intimate bond weaves<br />

Sternen itself<br />

Sich wob ein vertrauliches Band. between me and them.<br />

Ich dachte ... weiß nicht, was I imagine ... I don’t know what I<br />

ich dachte ... imagine ...<br />