insanity.pdf

insanity.pdf

insanity.pdf

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

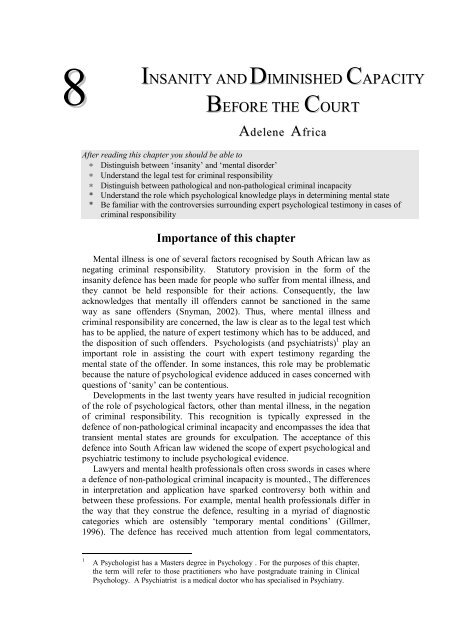

8 INSANITY AND DIMINISHED CAPACITY<br />

BEFORE THE COURT<br />

Adelene Africa<br />

After reading this chapter you should be able to<br />

∗ Distinguish between ‘<strong>insanity</strong>’ and ‘mental disorder’<br />

∗ Understand the legal test for criminal responsibility<br />

∗ Distinguish between pathological and non-pathological criminal incapacity<br />

* Understand the role which psychological knowledge plays in determining mental state<br />

* Be familiar with the controversies surrounding expert psychological testimony in cases of<br />

criminal responsibility<br />

Importance of this chapter<br />

Mental illness is one of several factors recognised by South African law as<br />

negating criminal responsibility. Statutory provision in the form of the<br />

<strong>insanity</strong> defence has been made for people who suffer from mental illness, and<br />

they cannot be held responsible for their actions. Consequently, the law<br />

acknowledges that mentally ill offenders cannot be sanctioned in the same<br />

way as sane offenders (Snyman, 2002). Thus, where mental illness and<br />

criminal responsibility are concerned, the law is clear as to the legal test which<br />

has to be applied, the nature of expert testimony which has to be adduced, and<br />

the disposition of such offenders. Psychologists (and psychiatrists) 1 play an<br />

important role in assisting the court with expert testimony regarding the<br />

mental state of the offender. In some instances, this role may be problematic<br />

because the nature of psychological evidence adduced in cases concerned with<br />

questions of ‘sanity’ can be contentious.<br />

Developments in the last twenty years have resulted in judicial recognition<br />

of the role of psychological factors, other than mental illness, in the negation<br />

of criminal responsibility. This recognition is typically expressed in the<br />

defence of non-pathological criminal incapacity and encompasses the idea that<br />

transient mental states are grounds for exculpation. The acceptance of this<br />

defence into South African law widened the scope of expert psychological and<br />

psychiatric testimony to include psychological evidence.<br />

Lawyers and mental health professionals often cross swords in cases where<br />

a defence of non-pathological criminal incapacity is mounted., The differences<br />

in interpretation and application have sparked controversy both within and<br />

between these professions. For example, mental health professionals differ in<br />

the way that they construe the defence, resulting in a myriad of diagnostic<br />

categories which are ostensibly ‘temporary mental conditions’ (Gillmer,<br />

1996). The defence has received much attention from legal commentators,<br />

1 A Psychologist has a Masters degree in Psychology . For the purposes of this chapter,<br />

the term will refer to those practitioners who have postgraduate training in Clinical<br />

Psychology. A Psychiatrist is a medical doctor who has specialised in Psychiatry.

Insanity and diminished capacity 2<br />

who have focussed largely on its form and content, as well as the factors<br />

which the courts have taken into account in passing judgement. These<br />

discussions have also focussed on the content of expert psychological<br />

testimony in cases where it has been adduced, specifically in relation to<br />

reasons why courts have either accepted or rejected such testimony (Snyman,<br />

1989; 1991; 1995; Rumpff, 1990; Burchell, 1995; Boister, 1996).<br />

This chapter explores the role which psychological knowledge plays in<br />

assisting the court in determining criminal responsibility where the accused’s<br />

mental state is in question. In order to achieve this aim, the chapter provides<br />

an overview of the statutory provisions for defences which negate criminal<br />

responsibility. These include the <strong>insanity</strong> defence, the defence of diminished<br />

responsibility, and the defence of non-pathological incapacity. This provides a<br />

platform to explore some of the difficulties which arise when psychological<br />

conceptions of mental illness (or disorder) intersect with legal notions of<br />

<strong>insanity</strong>. Figure 8.1 provides a flowchart summary that the reader may wish to<br />

refer to during the course of the chapter.<br />

Yes<br />

Was X able to act in accordance with an<br />

appreciation of wrongfulness?<br />

Yes<br />

Trial proceeds<br />

Verdict: Guilty<br />

or not guilty<br />

Disposition:<br />

Imprisonment<br />

X is charged with an offence<br />

Did X appreciate the wrongfulness of the act?<br />

No<br />

What was X’s mental state at the time of the<br />

offence?<br />

Pathological condition? Non-pathological condition?<br />

Mental<br />

disorder<br />

Mental defect Temporary<br />

emotional<br />

states<br />

Verdict: Not<br />

guilty by<br />

reason of<br />

mental illness<br />

Disposition:<br />

Indefinite<br />

hospitalisation<br />

Verdict: Not<br />

guilty<br />

Figure 8.1 Flowchart of the possible routes through the criminal justice<br />

system when criminal responsibility is at stake<br />

Free

Africa 3<br />

Insanity is a<br />

legally defined<br />

state of mind and<br />

does not refer to<br />

a mental<br />

disorder<br />

Mental illness<br />

refers to a<br />

behavioural or<br />

psychological<br />

pattern which<br />

causes personal<br />

distress and<br />

impairment<br />

The Insanity Defence (Pathological Criminal Incapacity)<br />

The term ‘<strong>insanity</strong>’ refers to a legally defined state of mind and does not<br />

refer to a particular psychological disorder or state. In fact, as will be shown,<br />

legal conceptions of <strong>insanity</strong> may be far removed from psychiatric or<br />

psychological conceptions of mental illness.<br />

Fitness to stand trial<br />

In terms of criminal procedure, every person is presumed to be sane until<br />

the contrary is proven. However in the case of mental illness or defect, when<br />

an accused’s capacity to follow court proceedings is compromised, he or she<br />

cannot be tried in a court of law. Section 77 of the Criminal Procedure Act 51<br />

of 1977 (CPA) therefore makes provision for an inquiry and report on the<br />

accused’s fitness to stand trial. Further statutory provision is made for expert<br />

testimony to establish the presence of mental illness or defect and the extent to<br />

which it impacts on the accused’s ability to follow proceedings. Where the<br />

offence has been violent, as in the case of murder, rape or culpable homicide,<br />

Section 79 of the CPA provides for the inquiry to be conducted by a panel of<br />

psychiatrists at a psychiatric hospital. Psychiatric evidence regarding the<br />

presence of mental illness and its impact on the capacity of the accused to<br />

understand proceedings is contained within the report presented to the court.<br />

However, the court may also require psychological evidence - for example,<br />

evidence pertaining to the accused person’s level of intellectual functioning.<br />

This inquiry is conducted and reported on by a psychologist 2 . If the findings of<br />

the psychiatrists and psychologist conclude that the accused is not fit to stand<br />

trial, he or she will be admitted to a state psychiatric hospital for an indefinite<br />

period of time.<br />

Where fitness to stand trial is concerned, the<br />

psychologist may play a role at the court’s request.<br />

Psychological knowledge regarding factors such as<br />

intellectual functioning, personality functioning and<br />

emotional functioning may therefore be admitted as<br />

testimony so that the court is put in a position to make a<br />

finding regarding the accused person’s capacity to<br />

follow proceedings.<br />

The impact which the accused person’s mental state has on his or her<br />

functioning is relevant to both the capacity to understand and to follow court<br />

proceedings, as well as his or her criminal responsibility. However, as will see,<br />

an inquiry into an accused’s fitness to stand trial has no bearing on the inquiry<br />

into his or her responsibility.<br />

The Legal Test for Insanity in South Africa<br />

When the <strong>insanity</strong> defence is raised, the court is concerned as to whether<br />

the accused can be held criminally responsible in light of the purported mental<br />

2 In terms of Section 6 of the Criminal Matters Amendment Act 68 of 1998 (which amends Section 79<br />

(1) of Act 51 of 1977), clinical psychologists are also empowered to conduct and report on forensic<br />

assessments concerning pathological mental states. Prior to this, only psychiatrists were legally<br />

allowed to perform this duty.<br />

Activity 8.1.<br />

X is accused of murdering his neighbour.<br />

In court he babbles incoherently and laughs<br />

inappropriately when the judge addresses<br />

him. Is he fit to stand trial? Explain your<br />

answer.

Affective<br />

functioning<br />

refers to<br />

emotional<br />

functioning.<br />

Conative<br />

functioning<br />

refers to<br />

volitional<br />

functioning<br />

Insanity and diminished capacity 4<br />

illness or defect (Reed and Seago, 1999). There are various legal tests which<br />

must be applied when this defence is raised, and while there are differences in<br />

various jurisdictions, these tests, and the defence in general, have their roots in<br />

English law.<br />

The legal test for <strong>insanity</strong> in South Africa is rooted in the McNaughton<br />

Rules of 1843 which stemmed from a murder trial where the accused was<br />

found ‘not guilty on the ground of <strong>insanity</strong>’. This right-from-wrong test is<br />

concerned with the accused’s legal responsibility at the time of the alleged<br />

offence and Card (1992, p.127) summarises it as follows:<br />

(a) Everyone is presumed sane until the contrary is proved.<br />

(b) It is a defence to a criminal prosecution for the accused to show<br />

that he was labouring under such a defect of reason, due to disease<br />

of the mind, as either not to know the nature and quality of his act<br />

or, if he did know this, not to know that he was<br />

doing wrong.<br />

Activity 8.3<br />

Discuss the difference between affective,<br />

conative and cognitive functioning.<br />

The McNaughton test relies heavily on the accused’s<br />

cognitive capacity (intellectual capacity) which may<br />

have compromised his or her insight and judgment. ‘Defect of reason due to<br />

disease of mind’ is central to the defence and does not consider other aspects<br />

Affective<br />

functioning<br />

refers to<br />

Activity 8.2<br />

emotional What is the legal test for <strong>insanity</strong> in South<br />

functioning. Africa?<br />

Conative<br />

functioning<br />

refers to<br />

volitional<br />

functioning<br />

of psychological functioning namely,<br />

affective (emotional) and conative (volitional)<br />

functioning, which are integral to human<br />

nature.. As a result, in English law, the<br />

defence cannot be raised if the offence was committed because of emotional<br />

upheaval caused by emotions such as rage, jealousy or stress. Equally, it is not<br />

possible to raise the defence of <strong>insanity</strong> where the accused has committed an<br />

alleged offence because of poor self-control as would be in the case of an<br />

‘irresistible impulse’. Card (1992) criticises the McNaughton Rules as being<br />

too restrictive because they do not allow for a defence of ‘irresistible impulse’.<br />

He says that the narrow focus on impaired cognitive capacities ignores the<br />

reality that mental illness can impair conative functioning.<br />

English law therefore explicitly requires biological evidence of mental<br />

illness and its concomitant effects, with the result that psychiatrists generally<br />

serve as expert witnesses in cases where ‘sanity’ is contested. This may<br />

explain why affective and volitional factors are not recognised in this defence,<br />

as they can be better understood within a psychological framework as opposed<br />

to a strictly medical or biological model.<br />

Box 8.1 Who was Daniel McNaughton?<br />

Mental defect<br />

refers to<br />

significantly<br />

below average<br />

intellectual<br />

functioning<br />

The McNaughton Rules of 1843 have their roots in the trial of Daniel McNaughton who was accused<br />

of murdering Edward Drummond. McNaughton, a wood-turner from Glasgow was in his early thirties<br />

and suffered from persistent delusions of persecution by the Tories. He was plagued by these delusions<br />

for several years prior to the murder and he tried to evade the ‘spies who were following him by going to<br />

England and to France. He claimed that they continued to follow him and that he was compelled to kill<br />

the British Prime Minister, Sir Robert Peel but mistakenly shot Edward Drummond who was Prime<br />

Minister’s Private Secretary. At his trial eight medical witnesses testified that his psychosis resulted in an<br />

inability to distinguish right from wrong. Today McNaughton’s symptoms would probably qualify for a<br />

diagnosis of schizophrenia, however as the diagnosis has not been developed at that time, records show<br />

that he was diagnosed with ‘chronic mania and dementia’.

Africa 5<br />

The jury found McNaughton ‘not guilty by reason of <strong>insanity</strong>’and he was remanded to a psychiatric<br />

institution for the rest of his life. (Rollin,1977).<br />

In the late nineteenth century, the scope of the McNaughton Rules was<br />

broadened in South Africa [CT3]so as to include the ‘irresistible impulse’ rule.<br />

The courts acknowledged that mental illness or defect could impair conative<br />

functioning and therefore negate responsibility (Kruger, 1980). In R v Koortz<br />

1953 (1) SA 371 (A), the re-formulated McNaughton Rules were accepted by<br />

the court:<br />

A person is not punishable for conduct which would in ordinary<br />

circumstances have been criminal if, at the time, through disease of mind<br />

or mental defect -<br />

(a) he was prevented from knowing the nature and quality of the<br />

conduct, or that it was wrong; or<br />

(b) he was the subject of an irresistible impulse which prevented him<br />

from controlling such conduct<br />

(Gardiner and Lansdown, cited in Kruger, 1980, p.156).<br />

Where the <strong>insanity</strong> defence was raised, most cases were decided under the<br />

‘irresistible impulse’ rule but several difficulties arose in its application. These<br />

centred around establishing whether in fact the impulse derived from mental<br />

illness and not from emotional factors such as jealousy, greed or revenge. In<br />

addition, it was difficult to establish whether the impulse was indeed<br />

irresistible and whether the accused genuinely had no control over it. These<br />

problems and perceived loopholes within the law were addressed by the<br />

Rumpff Commission of Inquiry into the Responsibility of Mentally Deranged<br />

Persons and Related Matters (RP 69/1967), which was established following<br />

the assassination of the South African Prime Minister, Hendrik Verwoerd, by<br />

a mentally ill offender. The Rumpff Commission concluded that a person’s<br />

responsibility for his or her actions is based on the ability to exercise free<br />

choice and the ability to distinguish between right and wrong (Kruger, 1980).<br />

The recommendations of the Commission subsequently gave rise to the<br />

provisions in Section 78(1) of the CPA which states that:<br />

A person who commits an act which constitutes an offence and who at<br />

the time of such commission suffers from a mental illness or mental<br />

defect which makes him incapable<br />

(a) of appreciating the wrongfulness of his act; or<br />

(b) of acting in accordance with an appreciation of the wrongfulness of<br />

his act,<br />

shall not be criminally responsible for such act.3<br />

3 This section of the Act has subsequently been amended as follows:<br />

A person who commits an act or makes an omission which constitutes an offence and<br />

who at the time of such commission suffers from a mental illness or mental defect<br />

which makes him or her incapable<br />

(a) of appreciating the wrongfulness of his or her act or omission; or<br />

(b) of acting in accordance with an appreciation of the wrongfulness of his or her act<br />

or omission.shall not be criminally responsible for such act or omission<br />

Section 5 of the Criminal Matters Amendment Act 68 of 1998<br />

The clinical<br />

assessment<br />

process includes<br />

the clinical<br />

interview,<br />

psychological<br />

testing and<br />

collateral<br />

information

Insanity and diminished capacity 6<br />

Diagnosing Mental Illness<br />

The criteria which courts apply with respect to responsibility embody a<br />

right-from-wrong-test, which assesses the capacity to act according to the<br />

appropriate insight. The test has biological (i.e. presence<br />

of mental illness) and psychological components (i.e.<br />

impairment of cognitive and/or conative functions) and<br />

a successful defence requires the presence of both.<br />

Case example 8.1 : Depression, murder and criminal responsiblity<br />

Activity 8.5<br />

Discuss the difference between mental<br />

illness and mental defect.<br />

In S v Kavin 1978 (2) SA 731 (W), the accused was charged with murdering his wife, daughter and son. He was<br />

also charged with the attempted murder of another daughter. His defence was that he was suffering from a mental<br />

illness which rendered him non-responsible. He was examined by three psychiatrists who concurred with a<br />

diagnosis of ‘severe reactive depression superimposed on a type of personality disorder displaying immature and<br />

unreflective behaviour’ (p. 734). Two psychiatrists opined that he was able to appreciate the wrongfulness of his<br />

act while a third was uncertain. However, all three concurred that his depressive state rendered him incapable of<br />

acting in accordance with an appreciation of wrongfulness. In this case the accused’s conative functioning was<br />

impaired by a depressive disorder.<br />

Case Exercise<br />

Read the case, along with S v Mahlinza 1967 1 SA 408 (A) (both can be accessed in the collections of law reports<br />

held by most academic libraries). Compare the arguments regarding what constitutes mental illness by focussing<br />

on the expert evidence which was led.<br />

The DSM-IV TR<br />

is a taxonomy of<br />

mental disorders<br />

The law does not provide a definition of mental illness or mental defect<br />

and therefore makes provision for expert testimony to establish this (Van<br />

Oosten, 1990). In order to make a diagnosis of mental illness, the psychologist<br />

uses a variety of tools as part of the clinical assessment process. The clinical<br />

interview provides the psychologist with the opportunity to gather salient<br />

aspects of the accused’s psychosocial history. This history-taking includes<br />

information such as the nature of the symptoms, the level of distress which is<br />

experienced, family history and occupational functioning. In addition the<br />

clinician (psychologist) may make use of measures such as psychological tests<br />

which provide objective information about the accused’s functioning. For<br />

example, personality tests will yield information regarding personality style<br />

and functioning while intelligence tests assess cognitive<br />

functioning. Collateral information (third party<br />

information) may be gathered from significant others so<br />

as to provide additional insight into the accused’s<br />

functioning in various spheres. This information may<br />

be provided by family members, work colleagues or other professionals (such<br />

as general practitioners, psychiatrists and psychologists) whom the accused<br />

has consulted.<br />

An important diagnostic tool which psychologists in South Africa use to<br />

make diagnoses, is the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders<br />

(DSM-IV TR) 8(APA, 2000). This system classifies mental disorders in terms<br />

of their diagnostic criteria (symptoms) and provides clinicians with the<br />

information necessary to make diagnoses. For example, to make a diagnosis of<br />

Schizophrenia 4 , the clinician has to establish the presence of psychotic<br />

symptoms, the duration of these symptoms and the degree to which the<br />

4 Schizophrenia is a psychotic disorder characterised by delusions, hallucinations, disorganised speech<br />

and disorganised or catatonic behaviour. (DSM-IV-TR, APA, 2000).<br />

Activity 8.4<br />

What are the various tools which the<br />

psychologist may use to make a diagnosis?<br />

Psychologists<br />

diagnose mental<br />

illness and do<br />

not determine<br />

criminal<br />

responsibility

Africa 7<br />

person’s functioning has been impaired. The DSM-IV TR (APA, 2000)<br />

provides guidelines which assist the clinician in this process. The evidence<br />

which the psychologist presents in court will therefore allude to the presence<br />

of mental illness (for example, Schizophrenia) and how this impacts on the<br />

accused’s functioning.<br />

It is important to note that the psychologist, in providing a diagnosis, is not<br />

required or able to offer an opinion on the accused’s criminal responsibility.<br />

This is a matter to be decided by the courts. As Ogilivie Thompson J A in R v<br />

Harris 1965 (2) SA 340 (A) at 365 B-C states,<br />

... it must be borne in mind that...in the ultimate analysis, the crucial<br />

issue of the appellant’s criminal responsibility for his actions at the<br />

relevant time is a matter to be determined not by psychiatrists but by the<br />

Court itself. In determining that issue - initially the trial Court and on<br />

appeal this Court - must of necessity have regard not only to expert<br />

medical evidence but also to all the other facts of the case, including the<br />

reliability of the appellant as a witness and the nature of his proved<br />

actions throughout the relevant period’. This dictum highlights that the<br />

issue of determining criminal responsibility is a legal question while the<br />

diagnosis of mental illness is a psychological question.<br />

A diagnosis of mental illness does not automatically imply that an accused<br />

is non-responsible. Snyman (2002) says that the fact that a person has been<br />

declared mentally ill in terms of the Mental Health Act 18 of 1973, does not<br />

imply that he or she is also mentally ill in terms of s78(1) of the CPA. This is<br />

because the latter is chiefly concerned with how mental illness negates<br />

responsibility, and not with the nature of mental illness itself. For example, if a Mentally ill<br />

person is diagnosed with Schizophrenia and certified in terms of the Mental offenders are<br />

Health Act 18 of 1973, this does not automatically negate responsibility. In hospitalised for<br />

order for a successful defence to be raised, it has to be<br />

indefinite<br />

Activity 8.6 periods of time<br />

proven that the symptoms of Schizophrenia impaired What kind of psychological knowledge can<br />

the person’s cognitive and/or conative functioning. assist the court in making findings<br />

regarding mental state?<br />

Disposition of Mentally Ill Offenders<br />

Where the court accepts the defence of <strong>insanity</strong>, the accused is found not<br />

guilty and will be remanded into the care of a state psychiatric hospital for an<br />

indefinite period of time (Kruger 1999). For example, in S v Kavin 1978 (2)<br />

SA 731 (W), the court accepted the evidence that the accused’s depression<br />

impaired his conative functioning and therefore he was found not guilty of<br />

murder and attempted murder. He was remanded into the care of a state<br />

psychiatric hospital for an indefinite period, and was declared unfit to possess<br />

a firearm. In cases such as this, provision is made for the review of the<br />

patient’s progress and the hospital may recommend a discharge based on the<br />

prognosis of the illness and the danger which the patient poses to him or<br />

herself and society. This process has to be ratified by the courts, particularly<br />

where the offence has been violent (Kruger, 1980).<br />

The Insanity Defence – Controversies and Challenges<br />

The <strong>insanity</strong> defence in South Africa has not evoked the same kind of<br />

controversy as in the case of American jurisdictions. For this reason it is useful<br />

to explore some of the debates which have plagued legal and psychological

Insanity and diminished capacity 8<br />

The legal test for<br />

pathological<br />

incapacity is<br />

identical to that<br />

for nonpathological<br />

incapacity<br />

practitioners in the U.S. American conceptions of <strong>insanity</strong> are much broader<br />

than those found in South African law. Consequently, a wide range of<br />

psychological states, which do not necessarily have a biological basis, are<br />

considered to be instances of <strong>insanity</strong> (Slovenko, 1995). The inclusion of an<br />

array of diagnoses as grounds for exculpation has been viewed as problematic<br />

by various legal commentators. Dershowitz (1994), for example, is sceptical<br />

of the mitigating function of syndrome evidence involving allegations of<br />

abuse. He views such evidence as an ‘abuse excuse’ which purely functions as<br />

a means of evading responsibility. He comments on psychiatry and<br />

psychology’s complicity in helping offenders to evade appropriate punishment<br />

by providing them with ‘cop-outs’ and ‘sob stories’ couched in psychological<br />

jargon. He feels that this kind of evidence threatens the foundations of the<br />

American legal system as it expands the parameters of excusable behaviour.<br />

This kind of thinking, along with the public outcry subsequent to the acquittal<br />

of John Hinckley 5 , has resulted in the re-evaluation of the <strong>insanity</strong> defence at<br />

both state and federal levels in the US. Consequently, some American<br />

jurisdictions have abolished the defence while in others the McNaughton rules<br />

have been modified (Steadman, McGreevy, Morrissey, Callahan, Robbins and<br />

Cirincione, 1993).<br />

Slovenko (1995) argues that it is difficult to establish the current status of<br />

the <strong>insanity</strong> defence in America, given the many changes which it has<br />

undergone in various states. Current debate has centred on whether or not the<br />

defence should be abolished completely, particularly because it is seen as a<br />

loophole for those who should be subject to the full force of the law. Some<br />

proponents of abolition argue that criminal responsibility is a matter of law<br />

and should be left to juries for deliberation and not to the assessment of<br />

psychiatric experts. Slovenko says that these critics argue that ‘psychiatry is<br />

corrupting the criminal justice system by expanding the concept of mental<br />

illness, always at the expense of the concept of responsibility’ (1995, p.34).<br />

While South African law has not been plagued with the same conundrums,<br />

there is some controversy regarding the legal test which is applied. The debate<br />

centres on the fact that the tests for pathological and non-pathological<br />

incapacity are identical. The defence of non-pathological incapacity<br />

acknowledges that psychological states such as anger, fear, shock and<br />

emotional stress may render a person non-responsible for his or her actions.<br />

Consequently, the circumstances within which an accused may be exculpated<br />

are substantially broadened. Unlike a successful <strong>insanity</strong> plea, a verdict of not<br />

guilty does not imply indefinite hospitalisation. Instead the accused is free to<br />

resume his or her life.<br />

Petty (1998) argues that the application of the provisions within s78 (1) of<br />

the CPA to what are in fact two distinct mental states, is problematic. The<br />

dilemma which this poses is exacerbated by the fact that because the law<br />

construes mental illness in terms of the degree of criminal responsibility, no<br />

diagnostic parameters have been set. From a psychological perspective, there<br />

is a clear distinction between distress and impairment caused by pathology and<br />

that which is caused by a temporary emotional state. However, these kinds of<br />

5 Public outcry followed the 1982 <strong>insanity</strong> acquittal of John Hinckley following the<br />

assassination attempt on President Reagan (Steadman, McGreevy, Morrissey,<br />

Callahan, Robbins and Cirincione, 1993).

Africa 9<br />

distinctions are not central to legal deliberations because the court is<br />

concerned with whether the accused met the criteria for the legal test and not<br />

with the nature of the mental state. Petty (1998) feels that the lack of<br />

conceptual clarity and the fact that the defences can be raised in the<br />

alternative, present challenges for the psychologist. Consequently, the<br />

boundaries between the defences are blurred, resulting in ‘an anomalous,<br />

circuitous process whereby the court applies the test for criminal capacity...’<br />

(Petty, 1998, p. 4).<br />

Diminished Responsibility<br />

South African law, in line with Anglo-American jurisdictions,<br />

acknowledges that there are varying degrees of criminal responsibility. As a<br />

result, Section 78(7) of the Criminal Procedure Act (51 of 1977) states that:<br />

If the court finds that the accused at the time of the commission of the<br />

act in question was criminally responsible for the act but that his<br />

capacity to appreciate the wrongfulness of the act or to act in accordance<br />

with an appreciation of wrongfulness of the act was diminished by<br />

reason of mental illness or mental defect, the court may take the fact of<br />

such diminished responsibility into account when sentencing the<br />

accused.<br />

In terms of this provision, the accused may be suffering from some form of<br />

mental illness but the level of impairment experienced does not fulfil the<br />

requirements for the legal test of <strong>insanity</strong>. The pathology is then considered to<br />

be a mitigating factor in the degree of responsibility. A defence of diminished<br />

responsibility does not afford the accused complete exculpation, but may<br />

result in a reduced sentence instead of indefinite confinement to a state<br />

psychiatric hospital (Snyman, 2002).<br />

Controversy<br />

It stands to reason that expert testimony is required to establish that an<br />

abnormality of the mind existed at the time of the offence. However some<br />

English legal commentators have questioned the role which psychiatrists and<br />

psychologists play in assessing diminished responsibility. In a report by the<br />

Butler Committee on Mentally Abnormal Offenders (cited in Clarkson and<br />

Keating, 1990), the proficiency of such experts in<br />

assessing degrees of mental responsibility was<br />

questioned, since this is a concept of law and morality<br />

and not of psychiatry or psychology. The Committee<br />

questioned whether the accused’s ability to conform to<br />

the law could be measured clinically given that the law requires a substantial<br />

impairment of mental responsibility. Allen argues that ‘ the question of<br />

substantial impairment is inappropriate for medical witnesses as it is one of<br />

degree and whether it exists depends not only on the medical evidence but on<br />

all the evidence of the case relating to the facts and circumstances of the<br />

killing’ (1995, p. 128). He argues that the courts have allowed expert opinion<br />

in these matters so as to produce a greater range of exemptions from murder.<br />

Activity 8.78.<br />

Discuss the elements of the defence of<br />

diminished responsibility

Insanity and diminished capacity 10<br />

The defence of<br />

automatism<br />

questions the<br />

voluntariness of<br />

the act<br />

Sane automatism<br />

is caused by a<br />

psychological<br />

blow resulting in<br />

an altered state<br />

of consciousness<br />

Dissociative<br />

amnesia is<br />

characterised by<br />

gaps in memory<br />

caused by<br />

traumatic events<br />

Other Defences Related to Capacity/voluntariness of the act – Sane and<br />

Insane Automatism<br />

The provisions within s78 (1) of the CPA are chiefly concerned with the<br />

extent to which mental illness affects criminal capacity. Thus while the court<br />

acknowledges that an offence has been committed, its chief concern is whether<br />

the accused can be held criminally responsible. However, there are instances<br />

where the court questions whether the act itself was voluntary, and in these<br />

cases the defence of automatism is raised. In this defence, an altered state of<br />

consciousness is presumed to result in a person committing an offence in an<br />

automaton state. When the voluntariness of the act is in question, it does not<br />

constitute an act in law and therefore the accused cannot be held criminally<br />

responsible (Kruger, 1999).<br />

South African courts, in line with Anglo-American<br />

jurisdictions, distinguish between sane and insane<br />

automatism. While the voluntariness of the act is central<br />

to both of these defences, a successful outcome has<br />

Activity 8.89.<br />

Explain how the defence of diminished<br />

responsibility differs from the <strong>insanity</strong><br />

defence<br />

differing implications for the accused. In cases of sane automatism, an<br />

acquittal means that the accused is free, while in instances of insane<br />

automatism, the accused is remanded to a psychiatric hospital for an indefinite<br />

period of time.<br />

Sane Automatism<br />

Sane automatism occurs when a person involuntarily performs an action<br />

while experiencing a change in his or her state of consciousness. This altered<br />

state does not have a pathological basis which can be linked to some inherent<br />

biological cause. Instead, the automatism is presumed to arise from severe<br />

psychological stress caused by life events, and results in ‘dissociation’. This<br />

complete splitting between mental and physical activity renders the person<br />

incapable of controlling his or her actions and consequently the act which is<br />

performed cannot be recognised as an act in law (Schopp, 1995).<br />

Dissociation is a psychological state which involves ‘a disruption in the<br />

usually integrated functions of consciousness, memory, identity or perception<br />

of the environment’ (Barnard, 1998, p. 28). The impairment in the integration<br />

of functions is caused by a ‘psychological blow’ which causes the person to<br />

dissociate. In the same way that a physical blow to the head can result in an<br />

altered state of consciousness, so too can traumatic experiences impair<br />

functioning. For example, if a person experiences a horrific attack, he or she<br />

may dissociate from that experience and experience amnesia for the event.<br />

Consequently, the person will be unable to recall details of the event while not<br />

experiencing any other difficulties in memory. This dissociation and the<br />

resultant amnesia occur, ostensibly because the psychological effects of the<br />

event are too traumatic for the conscious mind to deal with.<br />

Dissociative amnesia is an example of a dissociative disorder which has<br />

been forwarded as a diagnosis in the defence of sane automatism. The<br />

diagnostic features (symptoms) which are reported relate to gaps in memory,<br />

and these in turn are linked to traumatic or stressful events. In essence, a<br />

person suffering from dissociative amnesia will not suffer any other memory<br />

impairment and the amnesia is limited to the traumatic experience itself<br />

(DSM-IV TR, APA, 2000). For example, a person may report amnesia for<br />

Dissociation is a<br />

complete<br />

splitting between<br />

mental and<br />

physical activity

Africa 11<br />

episodes of sexual abuse at the hands of another. The physical and<br />

psychological trauma which characterises sexual abuse triggers the<br />

dissociative episode resulting in an altered state of consciousness. He or she<br />

‘blocks out’ the painful episodes and experiences<br />

amnesia for these events. Consequently the person is<br />

unable to relate any of these experiences as they are<br />

inaccessible to conscious memory. Mounting a defence<br />

of sane automatism<br />

In order to mount a defence of sane automatism it must be proven that the<br />

there has been an antecedent build-up such as a period of conflict or dispute<br />

which the person has experienced. The dissociative episode which the person<br />

undergoes must have been caused by some external trigger mechanism For<br />

example, a person a who has been experiencing marital difficulties may be so<br />

overwhelmed by the news that his or her is spouse is filing for divorce that he<br />

or she reacts violently and murders the spouse. Consequently, he or she may<br />

have no conscious memory of this action because of the extreme nature of the<br />

emotional reaction (in this example, rage), which completely overwhelms the<br />

conscious mind and renders him or her incapable of goal-directed action.<br />

Where such a claim is made, the psychologist has to assess whether the<br />

accused experienced a discrete dissociative episode at the time of the murder.<br />

An integral part of this diagnosis is whether the person has amnesia for the<br />

event. This diagnosis is15 difficult to make in that the psychologist relies on<br />

the accused’s version of events, which may not always be reliable. The<br />

assessment as to whether the person has a true absence of memory for that<br />

discrete period is also problematic, given that the clinician again relies on the<br />

accused’s account. On one hand, it may be more plausible that a person<br />

‘blocks out’ memories of situations in which they have<br />

been victimised, while on the other, it is more difficult<br />

to accept such claims made by a person who is the<br />

victimiser. While the question of the veracity of such<br />

claims falls within the ambit of the court, the<br />

psychologist is to a certain extent placed in the position of assessing the<br />

accused’s truthfulness. In essence one has to ask whether it is plausible that<br />

someone who commits a crime triggered by an external stressor is so<br />

overwhelmed by emotion, that he or she has no memory of it.<br />

For example, in S v Pederson [1998] 3 All SA 321, the appellant appealed<br />

against his conviction for the murder of his estranged wife. The appellant<br />

claimed that he had not acted consciously and voluntarily in killing his wife<br />

and that even if the act was voluntary, he had no intention of murdering her.<br />

He claimed that he was under the influence of alcohol and had been angry and<br />

aggressive because his wife was leaving him. There was a history of domestic<br />

violence which culminated in the stabbing of the wife. The appellant claimed<br />

to have no recollection of the incident as he had experienced an acute<br />

catathymic crisis at the time of the murder. The psychological evidence<br />

defined this crisis as a ‘mental storm’ which overwhelmed his mental capacity<br />

such that he was unable to exert control over actions. The Court questioned<br />

whether the Appellant had experienced a true absence of memory for the<br />

incident or whether the amnesia served the purpose of repressing the trauma<br />

caused by the incident. The Court held that for the defence of sane automatism<br />

to succeed, the Appellant had to prove that he had experienced true amnesia<br />

Activity 8.910.<br />

Explain what is meant by the voluntariness<br />

of an act.<br />

Activity 8.1011<br />

Give three examples of psychological<br />

blows which may result in sane automatism

Insanity and diminished capacity 12<br />

for the event and that there was an absence of control by the mind over his<br />

actions. The Court upheld the conviction the basis of the evidence that the<br />

accused had not acted in an automaton state and that his actions were<br />

sufficiently goal-directed.<br />

Case example 8.2 : How do we assess the truthfulness of an accused claiming sane automatism?<br />

In S v Potgieter 1994 (1) SACR 61 (A) the appellant appealed against the conviction and sentence which was<br />

imposed for the murder of her partner. At the trial, the defence argued that the appellant acted in a state of sane<br />

automatism and therefore was not criminally liable. The evidence which was led, indicated that she has been in a<br />

abusive relationship with her partner for six years. She had endured physical, verbal, emotional and financial<br />

abuse and also witnessed the maltreatment of her children from a previous marriage. The appellant testified that<br />

on the day in question, the deceased had once again assaulted her and ordered her to leave the house with her<br />

children. He left the house and she called a locksmith to open the safe so that she could retrieve the pistol which<br />

was kept there. She inserted a magazine and left the holstered pistol on the vanity slab in the bathroom. She<br />

testified that that night, she had woken up when she heard the baby crying. She found the deceased sitting in the<br />

lounge and asked him to turn down the volume on the television. She gave the baby his bottle and when she<br />

returned to her room, the deceased stood in the doorway, grabbed her and threw her against the wall. Her last<br />

memory was of him shouting at her and she saw his blurred image moving away from her. She then heard a loud<br />

bang after which she realised that she had a pistol in her hand and that he must have shot the deceased who was<br />

lying on the bed. Based on her account of events, the defence argued that the appellant had acted in an automaton<br />

state. The psychological evidence to support this highlighted her emotional reaction subsequent to the shooting as<br />

well as the fact that she did not have a history of violence. The state however questioned her account and her<br />

truthfulness as a witness. There were several inconsistencies in her testimony which did not accord with the facts<br />

of the case. Consequently, the state argued that her actions were not consistent with automatism as she had<br />

performed several goal-directed actions which resulted in the death of her partner. The court accepted the state’s<br />

evidence and found that the accused’s version of the events did not accord with the factual evidence. On appeal,<br />

the court upheld the conviction and supported the findings of the trial court. However in considering the sentence<br />

imposed, the court found that the trial court had erred in imposing a sentence of imprisonment. The court held that<br />

the abusive conditions which the appellant had endured, had resulted adversely affected her and that murder was<br />

committed when she was emotionally distraught and unable to exercise the requisite self-control. Consequently,<br />

the sentence was set aside and the matter was remitted to the trial court for consideration of a sentence of<br />

correctional supervision.<br />

Case Exercise<br />

Read the full case (in the law reports). Consider the argument advanced by the defence counsel. Construct your<br />

own argument in support of the defence’s contention that the trial judge had misdirected himself in finding that the<br />

appellant had acted in a goal-directed manner.<br />

Insane Automatism<br />

While sane automatism is brought about by external factors, insane<br />

automatism arises from a change in consciousness which is caused by mental<br />

illness (Reed and Seago, 1999). In this sense it can be seen as a variant of the<br />

<strong>insanity</strong> 16 defence in that it also requires the ‘disease of mind’ criterion. For<br />

example, the psychotic symptoms associated with schizophrenia can impair<br />

cognitive and volitional functioning to such an extent that the person is unable<br />

to act in a goal-directed manner. Consquently, the law acknowledges that an<br />

accused who suffers from a biological condition which may induce an<br />

automaton state, cannot be held criminally responsible as the act occurred<br />

outside of conscious awareness. A successful defence of insane automatism<br />

results in a verdict of ‘not guilty by reason of <strong>insanity</strong>’ which requires<br />

mandatory commitment to a psychiatric hospital for an indefinite period of<br />

time. The conditions governing commitment are therefore the same as for

Africa 13<br />

those who have been found not guilty under the <strong>insanity</strong> plea (Reed and<br />

Seago, 1999).<br />

Automatism : controversies and challenges<br />

While English courts have clear-cut guidelines as to the interpretation of<br />

sane automatism, American courts have failed to develop any clarity as to<br />

their interpretations. Schopp (1995), in reflecting on the stance in American<br />

jurisdictions, says that some courts have viewed automatism as a variation of<br />

the <strong>insanity</strong> plea while others have expressly rejected this notion and<br />

considered it a separate defence. Finkel (1988) refers to the sane automatism<br />

defence as an ‘atypical’ <strong>insanity</strong> defence because the jury rules on whether<br />

there was an act and does not concern itself with the existence of disease of<br />

mind or the issue of intent. Thus the mental state of the accused is not central<br />

to ascertaining responsibility. Finkel (1988) argues that psychiatric testimony<br />

provides ‘the room, shadings, and interpretative leeway’ (p. 291) which<br />

enables lawyers to employ the defence if other avenues have failed.<br />

The legal debates as to the interpretation of the defence are paralleled by<br />

psychological debates regarding the clinical veracity of acute periods of<br />

dissociative amnesia. Schopp (1999) argues that the incidence of the complete<br />

splitting between mental and physical activity is a clinical rarity. In fact, the<br />

DSM-IV TR (APA, 2000) states that an acute form of dissociative amnesia<br />

which is characterised by a sudden onset is less common than dissociation<br />

arising from protracted periods of trauma.<br />

As in Anglo-American jurisdictions, claims of sane automatism are viewed<br />

with caution by South African courts because a diagnosis of dissociation relies<br />

heavily on the accused’s account of the event. There are no objective<br />

psychological measures for assessing whether he or she experienced a discrete<br />

dissociative episode or the concomitant amnesia. While the factual evidence is<br />

central to the court’s deliberations, the psychologist’s diagnosis hinges on the<br />

accused’s account. The difficulty which arises is that expert psychological<br />

evidence is based on a claim of a discrete period of dissociation which<br />

occurred some time before the assessment. Kruger (1999) says that the<br />

reliability and truthfulness of the accused are crucial factors in laying a factual<br />

basis for the defence. This raises the question as to whether the expert is<br />

placed in the position of assessing the reliability of the accused or whether<br />

such claims are accepted on the face of what the accused has said. It is<br />

therefore an ethical and professional dilemma - does the expert have to assume<br />

the role of moral judge when asked to adduce evidence of such a nature? In<br />

addition, if the accused’s truthfulness is questioned by the court, how is the<br />

expert’s testimony viewed, based as it is on the accused’s account?<br />

Non-pathological Criminal Incapacity<br />

In the last twenty years South African courts have come to recognise the<br />

importance of psychological factors in the assessment of criminal<br />

responsibility. The provisions within s78(1) of the CPA have been interpreted<br />

in such a way that factors other than mental illness have been considered in the<br />

issue of non-responsibility (Strauss, 1995). Thus the biological component<br />

(i.e. mental illness) of this test is not the sole negating factor, and emotional<br />

factors have been held to affect criminal capacity.

Insanity and diminished capacity 14<br />

Non-pathological states refer to a wide range of temporary emotional<br />

reactions17 which may affect the accused’s ability to distinguish between right<br />

and wrong or the ability to act in accordance with an appreciation of<br />

wrongfulness (Snyman, 1989). As with the concept of <strong>insanity</strong>, nonpathological<br />

incapacity is not a psychological construct and merely refers to<br />

non-responsibility which does not arise from mental illness. Several landmark<br />

cases (such as S v Arnold 1985 (3) SA 256 (C) and S v Campher 1987 (1) SA<br />

940 (A) introduced the notion of non-pathological states<br />

such as emotional stress, personality disintegration,<br />

shock or anger, which can impair cognitive and/or<br />

conative functioning. In S v Laubscher 1988 (1) SA 163<br />

(A) for example, the accused appealed against his<br />

Activity 8.1112.<br />

Identify the elements of the defence of<br />

provocation<br />

conviction for the murder of his father-in-law. The shooting occurred as result<br />

of a confrontation with his parents-in-law regarding their efforts to dissolve<br />

his marriage and to deny him access to his son. The accused confronted his<br />

father-in-law, whereupon he fired twenty-one rounds into various rooms, some<br />

of which hit and killed the deceased. The defence led psychological and<br />

psychiatric evidence at the trial and the accused was said to have suffered<br />

from a ‘total personality disintegration’ which resulted in an impairment of<br />

functioning. However, both the trial and appeal court held that the expert<br />

testimony did not accord with the facts of the case. These facts showed that<br />

the accused demonstrated insight into what he was doing and that his actions<br />

were goal-directed and voluntary. The Laubscher judgement also commented<br />

that expert testimony is not indispensable in this defence and that the court is<br />

in a position to make a decision based on the facts of the case.<br />

Given that commonly accepted textbook diagnoses for temporary<br />

impairment do not exist, the defence has been interpreted by experts in various<br />

ways. Consequently, various psychological terms have been bandied about in<br />

an attempt to explain phenomena which do not fall within the parameters of<br />

psychopathology. Gillmer (1996) describes the defence as a ‘many-headed<br />

creature’ which can embody anything from a ‘total psychological<br />

disintegration’ to a ‘narrowing of consciousness’, ‘a separation of intellect and<br />

emotion’, ‘annihilator rage’, ‘dissociation’ or ‘good old-fashioned<br />

automatism’ (p. 20). It would seem as if psychology has attempted to provide<br />

the language and understanding to describe those non-pathological states<br />

which do not fit into the law’s conception of human nature. However, Gillmer<br />

(1996) questions whether psychology has not been complicit in assisting the<br />

law with diagnoses to support claims of temporary impairment, in order that<br />

courts view these as more credible and therefore acceptable as grounds for<br />

non-responsibility.<br />

Provocation<br />

The defence of provocation also falls within the ambit of non-pathological<br />

incapacity because it focuses on words or behaviour or a combination of the<br />

two which incite a person to react violently (Snyman, 2002). The emotional<br />

state induced by the provocation is temporary but may be so intense that the<br />

person’s cognitive and or conative functioning is impaired. The law is<br />

concerned with the effect of provocation on the accused, taking into account<br />

personal characteristics such as temperament which may explain the violent<br />

behaviour (Theron du Toit, 1993).

Africa 15<br />

An example of the way in which expert testimony has been adduced in this<br />

defence, is that of spousal homicide. Theron du Toit draws on the work of<br />

Hoffman and Zeffert (1988) by saying that ‘[t]he opinion of expert witnesses<br />

is admissible whenever, by reason of their special knowledge or skill, they are<br />

better qualified to draw inferences than the court. The admissibility of the<br />

evidence of expert witnesses is furthermore governed by the relevance of that<br />

evidence’ (1993, p. 247). She says that developments within case law<br />

regarding spousal homicide have pointed to the need for psychiatric or<br />

psychological evidence in ascertaining criminal responsibility. In the case of S<br />

v Campher 1987 (1) SA 940 (A), the court acknowledged this need and<br />

consequently expert testimony regarding battered woman syndrome was<br />

considered to be relevant and admissible. However, as cases such as S v Wiid<br />

1990 (1) SACR 561 (A) have shown, expert testimony is not indispensable,<br />

particularly when a factual foundation for non-responsibility has been laid in<br />

evidence. The result is that the onus is on the State to prove that the accused<br />

was criminally responsible. When a factual foundation has been laid, expert<br />

testimony may serve the purpose of facilitating this process but in the final<br />

analysis, it may well be superfluous (Theron du Toit, 1993). This antithetical<br />

situation highlights the difficulties which arise in defences which fall within<br />

the ambit of non-pathological incapacity. On one hand, expert testimony<br />

serves the purpose of outlining the psychological factors which lead to nonresponsibility.<br />

On the other, expert testimony is not required by law because<br />

the court may be in a position to make a finding based solely on the factual<br />

evidence (Van Oosten, 1993).<br />

Case example 8.3: Can rage impair conative functioning?<br />

In S v Moses 1996 (1) SACR 701 (C), the accused was charged with the murder of his lover. On the day<br />

in question, the accused and the deceased had unprotected intercourse after which the deceased declared<br />

that he had AIDS. The accused testified that he became enraged at hearing this and went to find an<br />

ornament with which he struck the deceased twice on his head. He then went to the kitchen to get a<br />

small knife and stabbed the deceased in the side. He returned to the kitchen to find a big knife with which<br />

he slit the deceased’s throat and wrists. The accused testified that he was overwhelmed with hatred for<br />

the deceased and he felt that his trust had been abused. It also reminded him of the sexual abuse which he<br />

had suffered at the hands of his father. His mind was flooded with thoughts as to how he would break the<br />

news of being HIV positive to his family and he also feared dying a horrible death. He testified that he<br />

was aware of what he was doing but was unable to control his actions because he was so enraged. In<br />

support of the defence of non-pathological incapacity resulting from extreme provocation, the defence<br />

led psychiatric and psychological evidence. This evidence focused on the accused’s psychosocial history<br />

which included sexual abuse, domestic violence and depression. He was diagnosed with borderline<br />

personality disorder and it was argued that he had manifested various neurotic behaviours such as head<br />

banging, bedwetting and fear of the dark, in childhood. This psychiatric ‘picture’ of the accused was<br />

coupled with a psychological ‘picture’ which traced a pattern of poor impulse control. It was argued that<br />

he was prone to anger and outbursts of violence and that he had exhibited rage reactions whenever he<br />

was provoked. The defence argued that given the accused’s personality structure and poor impulse<br />

control, his conative ability was impaired. He was therefore unable to control himself even though he<br />

was cognitively aware of his actions. In contrast, the state led rebuttal evidence in which the psychiatrist<br />

argued that a person’s conative functioning can only be impaired in sane automatism or other<br />

pathological states. It was argued that the accused did not act in an involuntary or automatic manner and<br />

that his actions were goal-directed and guided by conscious thought. He therefore had the cognitive<br />

capacity to distinguish right from wrong. The accused did not exhibit any signs of dissociative amnesia

Insanity and diminished capacity 16<br />

and therefore did not fulfil the criteria for sane automatism. The court found that the state’s evidence was<br />

problematic as it focussed on the accused’s cognitive capacity – which was never in dispute. The defence<br />

had argued that the accused had the cognitive capacity to appreciate wrongfulness but was unable to<br />

control his actions because of extreme provocation. In weighing up the evidence, the court found the<br />

accused’s ability to control his actions was significantly impaired and he was therefore acquitted.<br />

Case Exercise<br />

Read the case in the law reports. Provide a coherent argument as to why the accused should not have<br />

been acquitted.<br />

Non-pathological incapacity : controversies and challenges<br />

There are several problematic issues regarding the defence of nonpathological<br />

incapacity which are highlighted by legal commentators.<br />

The first issue relates to the onus of proof. Unlike the <strong>insanity</strong> defence, the<br />

accused does not bear the onus of proof, instead the State is required to prove<br />

beyond reasonable doubt that that s/he had criminal capacity at the time of the<br />

offence. However, the accused has to lay a foundation in evidence which the<br />

State then has to rebut (Boister, 1997). Burchell (1995) argues that there is an<br />

‘inherent injustice’ in placing the burden of proof on the accused claiming<br />

<strong>insanity</strong> while a plea of non-pathological incapacity places the onus of proof<br />

on the state. This ‘injustice’ is extended to the successful outcomes of these<br />

defences - in the former, it means confinement to a psychiatric hospital while<br />

the latter provides for complete acquittal. Burchell (1995) feels that a complete<br />

revision of legislation and burden of proof standards may address these<br />

problems but he is not optimistic about this occurring. It would seem that the<br />

courts are intent on applying the subjective test of criminal capacity<br />

particularly in the case of non-pathological incapacity.<br />

Following on from this, Burchell (1997) questions<br />

whether South African law is correct in applying a 19<br />

subjective test of criminal capacity and argues that it<br />

may be more useful to have some kind of objective test<br />

by which to measure the accused’s behaviour. He<br />

Activity 8.1213<br />

Identify three non-pathological states<br />

which may be used as grounds for<br />

exculpation.<br />

views the normative yardstick used in Anglo-American jurisdictions as being<br />

more useful and argues that a partial excuse as opposed to complete<br />

exculpation is more appropriate. .<br />

A third issue centres around a concern that the defence may be abused by<br />

those who have exhausted all other avenues in attempt to escape punishment.<br />

Snyman (1991) says that the courts have therefore treated such defences with<br />

great caution because they can be easily raised. In the same way that courts are<br />

circumspect with regards to the defence of sane automatism, so too do they<br />

view the defence of non-pathological incapacity. Snyman (2002) says that in<br />

those cases in which the defence has been considered seriously, the accused<br />

had shown a cumulative build-up of stress and/or provocation which then<br />

resulted in a temporary impairment of cognitive and/or conative functioning.<br />

Fourthly, while the notion of temporary emotional reactions suggests an<br />

interplay of psychological phenomena, there is no statutory requirement for<br />

expert evidence in such cases. It would appear that while a significant number<br />

of reported cases have relied on expert testimony, it is unclear whether the<br />

courts consider this evidence as indispensable for the defence to succeed.<br />

Kruger (1999) argues that psychiatric and psychological evidence do not play

Africa 17<br />

an indispensable role because the court itself is in a good position to make a<br />

decision based on the facts of the case. Burchell (1995) views the indecision<br />

regarding the importance of this testimony as problematic. There are instances<br />

when courts do not receive a balanced view of the accused’s actions because<br />

the state has not adduced psychiatric or psychological evidence. He suggests<br />

that judges should require the state to lead such evidence so as to mitigate<br />

against a one-sided view of the accused’s actions.<br />

The ambivalent attitude which courts have towards expert testimony is further<br />

fuelled by the courts’ concern as to the accused’s reliability and truthfulness<br />

since this defence hinges on the accused’s account of events. Burchell (1995)<br />

says that this defence by its very nature, is viewed with caution and if the<br />

accused’s reliability and truthfulness are questionable then the expert<br />

testimony will also be viewed in the same light (see, for example, S v<br />

Potgieter 1994 (1) SACR 61 (A). Burchell (1995) argues that one of the<br />

problems which arises in the forensic assessment of an accused, is that it<br />

occurs before the evidence has been heard in court. Therefore in pursuit of the<br />

truth, it would be advisable to allow the expert to re-evaluate his/her opinion<br />

after the factual evidence has been led. In this way greater weight may be<br />

given to such evidence after it has been established that the accused has<br />

provided the court with a convincing account of events.<br />

Finally, while the defence has been the focus of legal debate, it has also<br />

received some attention from mental health professionals, albeit to a lesser<br />

extent. The focus of discussion in these circles has been on the nature of<br />

expert evidence which is adduced (Van Rensburg & Verschoor, 1989; Strauss,<br />

1995; Van der Merwe, 1997). However the role of expert testimony in these<br />

cases has raised particular challenges for experts, and Zabow (1990) says that<br />

they ‘have been less than successful in attempting to adapt theory, diagnosis<br />

and clinical method to the framework of existing legal standards’ (p.5). In<br />

addition, in these cases experts do not have recourse to textbook diagnoses<br />

which can describe temporary cognitive or conative impairment (Strauss,<br />

1995).<br />

The discussion has shown that South African courts have been more accepting<br />

of the role of psychological factors in negating criminal responsibility but it<br />

would seem that a rather ambivalent attitude towards expert testimony<br />

prevails. As Boister concludes ‘[t]his indicates clearly that the crucial aspect<br />

of the defence of non-pathological criminal incapacity is not its psychological<br />

validity but its legal validity’ (1996, p. 373).<br />

Summary<br />

1. The legal test for <strong>insanity</strong> in South Africa has a biological component<br />

(ie the presence of mental illness) and a psychological component (the<br />

impairment of cognitive and/or conative functioning).<br />

2. The diagnosis of mental illness falls within the domain of psychiatrists<br />

and psychologists while the assessment of criminal responsibility falls<br />

within the domain of the court.<br />

3. In the defence of automatism the voluntariness of the act is in question.<br />

The person cannot be held criminally liable because the act is

Insanity and diminished capacity 18<br />

committed while he or she is an altered state of consciousness and is<br />

unable to perform goal-directed actions.<br />

4. The defence of non-pathological incapacity allows for temporary<br />

emotional states to be used as grounds for exculpation.<br />

Recommended reading<br />

Boland, F (1999). Anglo-American <strong>insanity</strong> defence reform: The war between<br />

law and medicine. Aldershot: Ashgate/Dartmouth.<br />

Burchell, J. M. (1997). South African Criminal Law and Procedure vol 1:<br />

General principles of Criminal Law. (Third edition) Cape Town: Juta.<br />

Reznek, L. (1997). Evil or ill? Justifying the <strong>insanity</strong> defence. London:<br />

Routledge.<br />

Snyman, C. R. ( 2002). Criminal Law. (Fourth edition). Durban: Butterworths.<br />

Slovenko, R. (1995) Psychiatry and criminal culpability. New York: John<br />

Wiley and Sons.<br />

Exercises<br />

1. How does the assessment of fitness to stand trial differ from an assessment<br />

of criminal responsibility. Use two examples to illustrate your answer.<br />

2. The defence of non-pathological incapacity provides a loophole in the law<br />

for those accused who want to evade criminal responsibility. Discuss this<br />

statement .<br />

3. Psychological evidence is superfluous in assisting the court in determining<br />

criminal responsibility. Argue in favour or against this statement by<br />

drawing on case law to support your argument.<br />

4. John is charged with the murder of his mother and his attorney raises<br />

queries regarding his mental state at the time of the offence. Collateral<br />

information from his sister indicates that John had been ‘acting strangely’<br />

for a few weeks prior to the offence. She reports that he was agitated,<br />

unable to sleep at night and would pace around restlessly. He also had an<br />

insatiable appetite which was quite out of character. On the day of the<br />

murder, John’s mother told him to do some gardening. He seemed very<br />

upset and agitated and was mumbling incoherently. He became enraged<br />

and bludgeoned his mother with a spade. Using a diagram, illustrate the<br />

process which should be followed to ascertain whether John can be held<br />

criminally responsible.<br />

5. Emma is charged with the murder of her lover but claims to have no<br />

memory of the incident when questioned by the police. She recalls that<br />

they had an argument about her partner’s infidelity and that she had been<br />

very upset by this. She has no memory of shooting her partner and says<br />

that it feels as if she ‘blacked out’ for a while. Her first memory<br />

subsequent to the shooting is of seeing her partner lying on the floor with<br />

the gun next to her. When Emma was questioned by the police, she<br />

appeared confused, disoriented and tearful. As her attorney, you will be

Africa 19<br />

arguing that Emma cannot be held criminally responsible on nonpathological<br />

grounds. Construct an argument to support your claim that<br />

she was unable to exercise volitional control because she was<br />

overwhelmed by rage. Draw on case law to support your argument and<br />

suggest how psychological evidence may assist your case.<br />

References<br />

Allen, M. J. (1995). Textbook on Criminal Law. London : Blackstone Press Limited.<br />

American Psychiatric Association (2000). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental<br />

Disorders-TR (Fourth edition Revised).<br />

Barnard, P. G. (1998). Diminished capacity and automatism as a defence. American<br />

Journal of Forensic Psychology, 16(2), 27- 62.<br />

Boister, N. (1996). Recent cases : general principles of liability. South African Journal of<br />

Criminal Justice, 9(3), 371-374.<br />

Burchell, J. (1995). Non-pathological incapacity: evaluation of psychiatric testimony. South<br />

African Journal of Criminal Justice, 8(1), 37-42.<br />

Burchell, J. M. (1997). South African Criminal Law and Procedure Vol 1: General Principles<br />

of Criminal Law. (Third edition) Cape Town: Juta.<br />

Card, R. (1992). Criminal Law. London : Butterworths.<br />

Clarkson, C. M.. V. and Keating, H. M. (1990). Criminal Law : Texts and materials. London<br />

: Sweet and Maxwell.<br />

Criminal Procedure Act, 51 of 1977.<br />

Criminal Matters Amendment Act 68 of 1998.<br />

Dershowitz, A (1994). The Abuse Excuse and other cop–outs, sob-stories and evasions of<br />

responsibility. New York : Free Press.<br />

Finkel, N. J. (1988). Insanity on trial. New York: Plenum Press.<br />

Gillmer, B. (1996). Psycho-legal incoherence. Paper presented to the National Congress of the<br />

South African Psychological Society. Johannesburg, September 1996.<br />

Kruger, A. (1980). Mental health law in South Africa. Durban: Butterworths.<br />

Kruger, A. (1999). Accused: Capacity to understand proceedings: Mental illness and criminal<br />

responsibility. In E. Du Toit, F. De Jager, A. Paizes, A. Skeen& S. van der Merwe(eds.).<br />

Commentary on the Criminal Procedure Act (Service 22). Cape Town: Juta.<br />

Rollin, H (1977). ‘McNaughton’s madness’. In D. West and A.Walk (eds). Daniel<br />

McNaughton: His trial and the aftermath. Kent: Gaskell Books.<br />

Petty, C. (1998). The psychopathology of self-control. Unpublished MA thesis, University of<br />

Stellenbosch.<br />

Reed, A. and Seago, P. (1999). Criminal Law. London: Sweet and Maxwell.<br />

Rumpff, (1990). Feite of woorde. Consultus, 3 (1), 19-22.<br />

R v Harris 1965 (2) SA 340 (A)<br />

S v Arnold 1985 (3) SA 256 (C)<br />

S v Campher 1987 (1) SA 940 (A)<br />

S v Kavin 1978 (2) SA 731 (W)<br />

S v Laubscher 1988 (1) S A 163 (A)<br />

S v Mahlinza 1967 (1) SA 408 (A)<br />

S v Moses 1996 (1) SACR 701 (C)<br />

S v Pederson 1998 3 All SA 321<br />

S v Potgieter 1994 (1) SACR 61 (A)<br />

S v Wiid 1990 (1) SACR 561 (A)<br />

Schopp, R. F. (1991). Automatism, <strong>insanity</strong> and the psychology of criminal responsibility: A<br />

philosophical enquiry. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.<br />

Slovenko, R. (1995) Psychiatry and criminal culpability. New York: John Wiley and Sons.<br />

Snyman, C. R. (1989). Die verweer van nie-patologiese ontoerekeningsvatbaarheid in<br />

die strafreg. Tydskrif vir Regswetenskap, 14(1), 1-15.<br />

Snyman, C. R. (1991). Provokasie as volkome verweer in die Strafreg. Consultus, 4(1),35-38.<br />

Snyman, C. R. ( 2002). Criminal Law. (Fourth edition). Durban: Butterworths.<br />

Steadman H., McGreevy, M., Callahan, L., Robbins, P. and Cirincone, C. (1993). Before and<br />

after Hinckley: evaluating <strong>insanity</strong> defence reform. New York: Guilford Press.

Insanity and diminished capacity 20<br />

Strauss, S. A. (1995). Nie-patologiese ontoerekeningsvatbaarheid as verweer in die<br />

strafreg. South African Practice Management, 16(4), 14-34.<br />

Theron Du Toit, R. (1993). Provocation to killing in domestic relationships. Responsa<br />

Meridiana, 6, (3), 230-252.<br />

Van der Merwe, R. (1997). Sielkundige perspektiewe op tydelike nie-patologiese<br />

ontoerekeningsvatbaarheid. Obiter, 18(1), 138-144.<br />

Van Oosten, F. F.W. (1990). The <strong>insanity</strong> defence : its place and role in criminal law. South<br />

African Journal of Criminal Justice, 3(1), 1-9.<br />

Van Oosten, F. F.W. (1993). Non-pathological criminal incapacity versus pathological<br />

criminal incapacity. South African Journal of Criminal Justice, 6(2), 127-147.<br />

Van Rensburg, P. and Verschoor, T. (1989) Medies-geregtelike aspekte van amnesie.<br />

Tydskrif vir Regswetenskap,14(2), 40-54.<br />

Zabow, T. (1990). Conditions other than mental illness or mental disorder in ‘criminal’ and<br />

‘diminished responsibility’ (the meaning of psychiatric disorder in criminal responsibility).<br />

Psychiatric Insight, 7 (1), 4-5.