here - UCLA

here - UCLA

here - UCLA

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

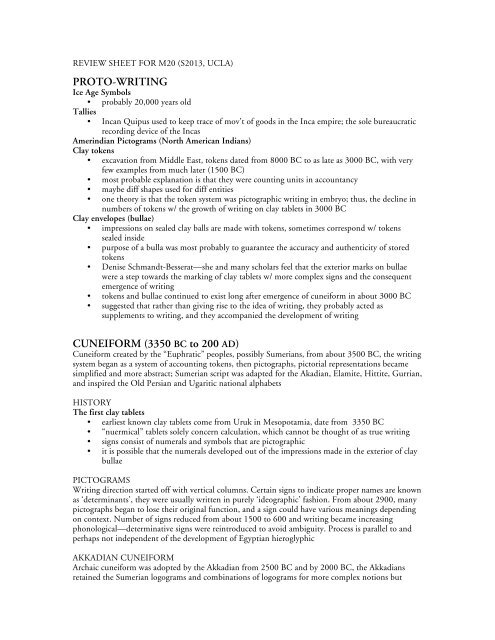

REVIEW SHEET FOR M20 (S2013, <strong>UCLA</strong>)<br />

PROTO-WRITING<br />

Ice Age Symbols<br />

• probably 20,000 years old<br />

Tallies<br />

• Incan Quipus used to keep trace of mov’t of goods in the Inca empire; the sole bureaucratic<br />

recording device of the Incas<br />

Amerindian Pictograms (North American Indians)<br />

Clay tokens<br />

• excavation from Middle East, tokens dated from 8000 BC to as late as 3000 BC, with very<br />

few examples from much later (1500 BC)<br />

• most probable explanation is that they were counting units in accountancy<br />

• maybe diff shapes used for diff entities<br />

• one theory is that the token system was pictographic writing in embryo; thus, the decline in<br />

numbers of tokens w/ the growth of writing on clay tablets in 3000 BC<br />

Clay envelopes (bullae)<br />

• impressions on sealed clay balls are made with tokens, sometimes correspond w/ tokens<br />

sealed inside<br />

• purpose of a bulla was most probably to guarantee the accuracy and authenticity of stored<br />

tokens<br />

• Denise Schmandt-Besserat—she and many scholars feel that the exterior marks on bullae<br />

were a step towards the marking of clay tablets w/ more complex signs and the consequent<br />

emergence of writing<br />

• tokens and bullae continued to exist long after emergence of cuneiform in about 3000 BC<br />

• suggested that rather than giving rise to the idea of writing, they probably acted as<br />

supplements to writing, and they accompanied the development of writing<br />

CUNEIFORM (3350 BC to 200 AD)<br />

Cuneiform created by the “Euphratic” peoples, possibly Sumerians, from about 3500 BC, the writing<br />

system began as a system of accounting tokens, then pictographs, pictorial representations became<br />

simplified and more abstract; Sumerian script was adapted for the Akadian, Elamite, Hittite, Gurrian,<br />

and inspired the Old Persian and Ugaritic national alphabets<br />

HISTORY<br />

The first clay tablets<br />

• earliest known clay tablets come from Uruk in Mesopotamia, date from 3350 BC<br />

• “nuermical” tablets solely concern calculation, which cannot be thought of as true writing<br />

• signs consist of numerals and symbols that are pictographic<br />

• it is possible that the numerals developed out of the impressions made in the exterior of clay<br />

bullae<br />

PICTOGRAMS<br />

Writing direction started off with vertical columns. Certain signs to indicate proper names are known<br />

as ‘determinants’, they were usually written in purely ‘ideographic’ fashion. From about 2900, many<br />

pictographs began to lose their original function, and a sign could have various meanings depending<br />

on context. Number of signs reduced from about 1500 to 600 and writing became increasing<br />

phonological—determinative signs were reintroduced to avoid ambiguity. Process is parallel to and<br />

perhaps not independent of the development of Egyptian hieroglyphic<br />

AKKADIAN CUNEIFORM<br />

Archaic cuneiform was adopted by the Akkadian from 2500 BC and by 2000 BC, the Akkadians<br />

retained the Sumerian logograms and combinations of logograms for more complex notions but

pronounced them as the corresponding Akkadian words. They also kept the phonetic values but<br />

extended them far beyond the original Sumerian inventory of simple types. Many more complex<br />

syllabic values of Sumerian logograms were transferred to the phonetic level, and polyphony became<br />

an increasingly serious complication in Akkadian cuneiform.<br />

King Hammurabi of Babylon (died 1750 BC) unified all of southern Mesopotamia. Babylonia<br />

thus became the great and influential center of Mesopotamian culture. The Code of Hammurabi is<br />

written in Old Babylonian cuneiform, which developed throughout the shifting and less brilliant later<br />

eras of Babylonian history into Middle and New Babylonian types.<br />

The expansion of cuneiform writing outside Mesopotamia began in the 3rd millennium, when<br />

the country of Elam in southwestern Iran was in contact with Mesopotamian culture and adopted the<br />

system of writing. The Elamite sideline of cuneiform continued far into the 1st millennium BC,<br />

when it presumably provided the Indo-European Persians with the external model for creating a new<br />

simplified quasi-alphabetic cuneiform writing for the Old Persian language<br />

In the 2nd millennium the Akkadian of Babylonia, frequently in somewhat distorted and<br />

barbarous varieties, became a lingua franca of international intercourse in the entire Middle East, and<br />

cuneiform writing thus became a universal medium of written communication.<br />

DERIVED SCRIPTS<br />

Complexity of the system prompted simplified versions of the script ! Old Persian was written in a<br />

subset of simplified cuneiform characters known as Old Persian Cuneiform.<br />

DECIPHERMENT<br />

• 17th century (1618): European travelers return from Persia with records of inscriptions in<br />

Old Persian on walls of ancient Persepolis, the capital of Darius and the Persian kings of the<br />

Achaemenid dynasty<br />

• 18th century: 1) Carsten Niebuhr noticed that many of the (new and more) inscriptions<br />

were duplicated, enabling him to check one set of readings against another. He confirmed<br />

the left-to-right direction of the writing. He was able to distinguish 3 unique scripts.<br />

• knowledge of cuneiform was lost until 1835 when Henry Rawlinson found the Behistun<br />

inscriptions in Persia.<br />

• inscription consist of identical texts in 3 official languages of the empire: Old Persian,<br />

Babylonian, and Elamite (3300-500BC), helped in decipherment of cuneiform.<br />

IMPORTANT PEOPLE<br />

• Carsten Niebuhr – a Danish traveler who noticed that t<strong>here</strong> were 3 different cuneiform<br />

scripts at Persepolis<br />

• Grotefend – a German high school teacher who took the first serious step towards<br />

decipherment; attempted to decipher Old Persian cuneiform; concluded that the single<br />

slanting wedges must be word dividers and the system must be alphabetic; although not<br />

wholly correct, it served well in identifying names which were indeed spelt alphabetically;<br />

complied an alphabet of Old Persian, many proved wrong esp when he tried to extend his<br />

system beyond proper name; he attempted decipherment of Old Persian as an alphabet. In<br />

fact, the script is partially syllabic; many of his values were t<strong>here</strong>fore incorrect, particularly<br />

w<strong>here</strong> he allocated more than one sign to a single sound value and more than one sound<br />

value to a single sign<br />

• Henry Rawlinson—the person who copied the entire Behistun inscription; generally credited<br />

with decipherment of Babylonian cuneiform, but never explained how he did it, recent study<br />

of his notebooks suggests that he borrowed the work of the scholar Edward Hicks w/o giving<br />

him credit; knowledge of Avestan and Sanskirt, he expected consistent relationship btw<br />

words of the same meaning in Avestan, Sanskirt and Old Persian ! decipherment of the<br />

Behistun inscription in Old Persian; he came across different Babylonian signs for<br />

ba,bi,bu,ab,ib,ub, he at first regarded the all as diff ways of writing b (homophonous);<br />

conversely, he accepted that vertain signs could stand for more than one sound (polyphonic);

he was able to add to Grotefend’s decipherment; he identified the names of people rule by<br />

Darius and allotted values to many more signs in Old Persian.<br />

Babylonian cuneiform was considered decip<strong>here</strong>d in 1857 when both Rawlinson and Hincks<br />

came up w/ the same translation of the Tiglath-Pileser I’s text<br />

Babylonian and Elamite cuneiform clearly contained non-alphabetic elements, given their large #<br />

of diff signs<br />

OLD PERSIAN CUNEIFORM (550-400 BC)<br />

• it is not a direct descendent of the Sumerian and Babylonian systems b/c even though the<br />

physical appearance of the signs are cuneiform, but the actual shape of the signs were<br />

completely original<br />

- it is a syllabic script that also contain some logograms, but majority of the signs are syllabogram,<br />

and it is classified as a syllabic script<br />

EVOLUTION of cuneiform:<br />

beginning = pictographic symbols, by the time of Babylonian cuneiform ! signs bore almost no<br />

resemblance to their pictographic origins; perhaps as late as the middle of the 2 nd millennium BC,<br />

signs on clay tablets became turned through 90 degrees counter-clockwise, and script written<br />

horizontally instead of vertically anymore, and from writing direction of colums R to L change to<br />

inline L to R<br />

Egyptian hieroglyphs (3300 BC – 400 AD)<br />

Egyptian hieroglyphs contained a combination of logographic and syllabic elements<br />

HISTORY AND EVOLUTION<br />

For many years, earliest known hieroglyphic inscription was the Narmer Palette (3200BC), but<br />

excavation at Abydos under Gunder Dreyer discovered the Tablets of Abydos with protohieroglyphic<br />

inscriptions<br />

Hieroglyphs consist of 3 kinds of glyphs: phonetic glyphs, including 1)single-consonant<br />

characters that functioned like an alphabet; 2) logographs, representing morphemes (smallest<br />

linguistic unit that has semantic meaning); 3) determinatives, which narrowed down the meaning of<br />

a logographic or phonetic words<br />

As writing developed and became more widespread among the Egyptian people, simplified<br />

glyphs forms developed, resulting in the hieratic (priestly) and demotic (popular) script<br />

Hieroglyphs continued to be used under Persian rule, and after Alexander’s conquest of Egypt.<br />

Some believe that hieroglyphs may have functioned as a way to distinguish ‘true Egyptians’ from the<br />

foreign conquerors, another reason may be the refusal of the change of culture by a foreign country.<br />

But by 400AD, few Egyptians were capable of reading hieroglyphs.<br />

DECIPHERNMENT OF HIEROGLYPHIC WRITINGS<br />

Real breakthrough in decipherment began in the early 1800s ! IMPORTANT PEOPLE!<br />

• Thomas Young – one of the first who tried to decipher Egyptian hieroglyphs, he used the 29<br />

letters of demotic alphabet for decipherment. He concluded that the demotic script was a<br />

mixture of alphabetic signs and other hieroglyphic-type signs, and hieroglyphic script used<br />

an alphabet to spell foreign names, remaining hieroglyphs, the part used to write the<br />

Egyptian language, were non-phonetic<br />

• Jean-Francois Champollion – made the complete decipherment of the hieroglyphs. He<br />

translated parts of the Rosetta stone in 1822, showing that the written Egyptian language<br />

was similar to Coptic (The Coptic alphabet is a modified form of the Greek alphabet, with<br />

some letters (which vary from dialect to dialect) deriving from demotic.), and that the<br />

writing system was combination of phonetic and ideographic signs.

WRITING SYSTEM<br />

same sign can be interpreted in different ways: as a phonogram (phonetic reading) as a logogram, or<br />

as an ideogram (“determinative”, semantic meaning” ), Determinative was not read as a phonetic<br />

constituent, but facilitated understanding by differentiating the word from its homophones<br />

PHONETIC READING<br />

• most hieroglyphic signs are phonetic in nature, meaning the sign is read independent of its<br />

visual characteristics<br />

(Rebus principle)<br />

• phonograms, whether w/ one consonant (unilateral), or two or three. The 24 uniliteral signs<br />

make up the so-called hieroglyphic alphabet<br />

• hieroglyphs are written from right to left and left to right, or from top to bottom, usually<br />

direction from R to L<br />

• words are not separated by blanks or by punctuation marks, but certain hieroglyphs tend to<br />

appear at the end of words, making words easier to distinguish<br />

• T<strong>here</strong> are some 24 uniconsonantal signs in the hieroglyphic script, referred to as an alphabet.<br />

In addition, the script used biconsonantal and triconsonantal signs, and various nonphonetic<br />

signs.<br />

PHONETIC COMPLEMENTS<br />

Egyptian writing is often redundant; redundant characters accompanying bilateral or trilateral signs<br />

are called phonetic complements added before the sign or after the sign or even frame the sign to<br />

provide clarity to the spelling of the hieroglyph, also used to allow the reader to differentiate between<br />

signs which are homophones (A characteristic of several written signs expressing the same phoneme<br />

in the language. For example, the written ‘too, two, to’ are all pronounced too.)<br />

SEMANTIC READING<br />

• Logogram – most frequently used common nouns, they are always accompanied by a mute<br />

vertical stroke, indicating their status as a logogram<br />

• Determinatives – these mute characters are placed at the end of the word to clarify what the<br />

word is about, as homophonc glyphs are common<br />

ANOTHER VERSION<br />

1) Decipherment<br />

Before the Rosetta Stone, most decip<strong>here</strong>rs believed that Egyptian hieroglyphs did not represent<br />

sounds, but rather ideas. Most of these ideas came from Horapollo who wrote a treatise in 4th<br />

century AD, a combination of fictitious ideas about the meaning and the use of signs.<br />

Kircher, entrusted with deciphering a cartouche (a small group of hieroglyphs in the inscription<br />

enclosed in an oval outline), found an elaborate text, while it was just the name of a pharaoh spelt out<br />

phonetically. However, he assisted in the rescue of Coptic, the language of the last phase of ancient<br />

Egypt. The Coptic language dates from Christian times and was the official language of the Egyptian<br />

church, but lost ground to Arabic and by the late 17th century was headed for extinction.<br />

Meanwhile, others started to hypothesize that some hieroglyphs might have phonetic values.<br />

The Rosetta Stone was found in 1799 by French soldiers, the bottom one being Greek and the<br />

top one Egyptian hieroglyphs with visible cartouches and the middle being demotic, a cursive form of<br />

the hieroglyphic script. The Greek translation produced a decree passed by a council of priests on the<br />

first anniversary of the coronation of Ptolemy V Epiphanes, king of Egypt, on 27 March 196 BC.<br />

After looking for names like Ptolemy, Alexander, etc in the demotic script, they noticed that they<br />

names were also spelled alphabetically. However, the demotic script was not wholly alphabetic.<br />

Thomas Young started his work on the Rosetta Stone in 1814. He noticed that demotic and<br />

hieroglyphic symbols were very much alike. He concluded that the demotic scrpt was a mixture of<br />

alphabetic signs and other, hieroglyphic-type signs. Going further, he assumed that Ptolemy, through

written in hieroglyphs, was spelt alphabetically. His reason was that Ptolemy was a foreign name,<br />

non-Egyptian, and t<strong>here</strong>fore could not be spelt non-phonetically as a native Egyptian name would<br />

be.<br />

The full decipherment of Egyptian hieroglyphs is the work of Jean-Francois Champollion, who<br />

announced it in 1823. His knowledge of Coptic aided him in the decipherment and figuring out the<br />

meaning of the words produced.<br />

In addition to the Rosetta stone, another key was the Philae Obelisk. The base block inscription<br />

was in Greek, the column inscription in hieroglyphic script. In the Greek the names of Ptolemy and<br />

Cleopatra were mentioned, in the hieroglyphs only two cartouches occurred. One of the cartouches<br />

was almost identical to one form of the cartouche of the Ptolemy on the Rosetta Stone. T<strong>here</strong> was<br />

also a shorter version of the Ptolemy cartouche on the Rosetta stone. He decided that the shorter<br />

version spelt Ptolemy, while the longer (Rosetta) cartouche must involve some royal title, tacked onto<br />

Ptolemy's name. He got 2 different signs for t, but deduced that they were homophones (signs<br />

representing the same sound). He applied these values to other non-Egyptian and Egyptian names<br />

and was surprised to discover that they produced Egyptian sounding words. Although initially, he did<br />

not think that the hieroglyphic script had phonetic elements, he accepted it, allowing him to decipher<br />

the second half of the long cartouche of Ptolmey on the Philae obelisk. Knowledge of Coptic was<br />

essential in apply sound values and pronunciation.<br />

The writing system is a mixture of semantic symbols, i.e. symbols that stand for words and ideas,<br />

also known as logograms, and phonetic signs, phonograms, that represent one or more sounds<br />

(alphabetic or poly-consonantal). Some hieroglyphs are recognizable pictures, but the picture does<br />

not necessarily give the meaning of the sign. A picture of a hand can function as a hand or the sound<br />

value of t.<br />

2) Development:<br />

Egyptian hieroglyphs suddenly appear in about 3300 BC, just prior to the beginning of dynastic<br />

Egypt, and virutally fully developed. The stimulus for the creation of the hieroglyphic script may<br />

have been the system of writing that had started in Mesopotamia around 3350 BC. They could have<br />

borrowed the idea of phonography from the Sumerians.<br />

Possible elements of Late Uruk influence on Egyptian writing, Naqada II-III period (3500-3300<br />

BC):<br />

• No evident pre-historical development that would explain the rapid development of<br />

architecture, art, ceramics as is the case in Mesopotamia<br />

• Niched-wall architecture of 1st-3rd dynasties<br />

• clay cones used in architecture<br />

• cylinder seals<br />

• artistic motifs<br />

a. entwined necks (Narmer Palette)<br />

b. Hero scenes (grave paintings (Hieronkopolis) and knife handles)<br />

From hieroglyphs, two cursive scripts developed, hieratic and from it demotic, the first dating<br />

almost from the invention of hieroglyphs, the second from after about 650 BC. Hieratic became a<br />

priestly script, as suggested by its name, only after it was ousted by demotic; originally hieratic was<br />

Egypt's everyday administrative and business script.<br />

Egyptian hieroglyphs were written and read both from right to left and from left to right. They<br />

usually wrote right to left if it was not a special case (like for symmetry).<br />

No one knows what ancient Egyptian sounds like. We assume. Egyptians did not mark their<br />

vowels, we have to guess what they are. Clues are from Coptic and other bilingual texts with Egyptian<br />

script and a script that marks their vowels.<br />

CHINESE (ca 1200 BC to present)<br />

Origin of Chinese characters emerged around 1600 BC, possibly much earlier; influenced Japanese,<br />

Korean and Vietnamese

MAYAN (300 BC to 1600 AD)<br />

• a writing system of the pre-Columbian Maya civilization of Mesoamerica, earliest<br />

inscriptions dated to 3rd cent. BC, usage continued until shortly after Spanish exploration in<br />

the 16th cent.<br />

• Maya writing used logograms complemented by a set of syllabic glyphs<br />

• individual symbols could represent either a word or a syllable, and the same glyph could<br />

often be used for both<br />

• different glyphs could be read the same way (homophony)<br />

Decipherment<br />

The numbers (and calendar) were the first part of the Mayan writing system to be decip<strong>here</strong>d by<br />

scholars during the 19th century. Mayans used place value that increases in multiples of 20.<br />

• In measuring time, the Maya began by combining the numerals 1 to 13 with 20 named days.<br />

Then they expanded the 260 day count by making a third wheel to make 365 days a year.<br />

This was for the short count.<br />

• For the long count, they created a zero at 4 Ahau 8 Cumku.<br />

• The Dresden Codex is full of dates. It is an almanac for difination, in which each day is<br />

linked to other days by complex astronomical calculations and is t<strong>here</strong>by given an<br />

astrological significance expressed in the deeds of gods.<br />

The next major step in the decipherment of Mayan glyphs - the realization that they were<br />

partially phonetic—dates back to the time of the Spanish Inquisition. De Landa wrote a book that<br />

contains the Mayan 'alphabet', which proved to be the key to deciphering Mayan glyphs in the 20th<br />

century. He did not realize that the glyphs were syllabic. But he knew that Mayan consonants could<br />

change their meaning depending on whether they were unglottalized or glottalized.<br />

In 1876, Leon de Rosny applied the Landa alphabet to the first sign in the glyph for 'turkey' in<br />

the Madrid Codex. Rosny went on to propose that Mayan writing was a phonetic system, based on<br />

syllables. He was critized by Thompson, who dominated Maya studies, and ad<strong>here</strong>d to his belief that<br />

the script, was logographic.<br />

In 1952, Yuri Knorosov propsed phonetic readings of many glyphs, including the one for dog.<br />

Knorosov noticed that the first sign in the dog glyph was the same as the second sign in the turkey<br />

glyph. He also produced other decipherments like this in the Dresden Codex.<br />

Dramatic breakthroughs occurred in the 1970's - in particular, at the first Mesa Redonda de<br />

Palenque, a scholarly conference organized by Merle Greene Robertson at the Classic Maya site of<br />

Palenque held in December, 1973. A working group was led by Linda Schele and identified a sign as<br />

an important royal title, enabling them to understand the histories of each Mayan king.<br />

Problems with decipherment: no Mayan dictionary, mixed writing system of phonography and<br />

logography (same word could be written in several ways). Words can be written with just logographs,<br />

just phonograms, or both.<br />

Basic features of Mayan: 85% of the Mayan glyphs can be ‘read’. T<strong>here</strong> is a Mayan syllabary<br />

w<strong>here</strong> t<strong>here</strong> are a large number of variant signs for a single sound (homophony). Some syllabic signs<br />

can also act as logograms. T<strong>here</strong> is also polyphony (one sign with several different pronunciations).<br />

Development<br />

• The Olmec is viewed as the “mother culture” in Central America; They developed a system<br />

of writing, the long-count calendar and a complex religion. The Olmecs had a considerable<br />

influence on the fledgling Maya culture.<br />

• During 300 to 900 AD, the Maya refined the long-count calendar and developed a more<br />

advanced written language. New evidence maybe suggests that the Maya were the ones who<br />

invented writing in Mesoamerica.<br />

PRECOLUMBIAN , MESOAMERICAN COMMUNICATION DEVICES<br />

• quipu: a knotted arrangement of ropes used to record and keep track of goods in the Inca<br />

empire. They were the sole bureaucratic recording device of the Incas; it was the job of the

'quipucamayocs' to tie and interpret the knots for uses like tax collecting, output, etc. Each<br />

knot represented a value in the decimal system, depending on its position or absense. Used<br />

during 2500 BC.<br />

• abacus: T<strong>here</strong> have been recent suggestions of a Mesoamerican (the Aztec civilization that<br />

existed in present day Mexico) abacus called the Nepohualtzitzin, circa 900-1000 A.D.,<br />

w<strong>here</strong> the counters were made from kernels of maize threaded through strings mounted on a<br />

wooden frame.<br />

THE ALPHABETS<br />

• The history of the alphabet begins in Ancient Egypt, more than a millennium into the<br />

history of writing. The first more or less true alphabet emerged around 2000 BC to represent<br />

the language of Semitic workers in Egypt, and was derived from the alphabetic principles of<br />

the Egyptian hieroglyphs.<br />

• Egyptian acrophonic principle influenced the Proto-Canaanite and Proto-Sinaitic<br />

inscriptions<br />

• Inscriptions of what are considered Proto-Sinaitic are from Serabit el-Khadem, dated to<br />

1500 BC. Sir Alan Gardiner saw the resemblance between some of these Proto-Sinaitic signs<br />

and Egyptian hieroglyphs that were pictographic. He named the signs using the Semitic<br />

word that was equivalent to the meaning that the sign had in Egyptian, and these names are<br />

the Hebrew alphabet’s letter’s names. The actual inventors could be Canannites and not the<br />

Semitic people living in Egypt.<br />

• Ugaritic alphabet: By the 14th century, hard evidence of the alphabet’s existence is found in<br />

a place called Ugarit. T<strong>here</strong> are only 30 distinct characters. The order of these signs is nearly<br />

identical to the order traditionally used for Aramaic, Phoenician, Arabic, and Hebrew<br />

• Phoenician alphabet: Used as early as 15th century BC at Byblos, the Phoenician alphabet<br />

consisted of 22 letters, and vowels were not indicated. This descended from a North Semitic<br />

script, and it changed only in letters’ shapes. Greek, Hebrew, and the Arabic alphabets<br />

evolved from this script.<br />

• Aramaic alphabet: The Aramaic alphabet, which evolved from the Phoenician in the 7th<br />

century BC as the official script of the Persian Empire, appears to be the ancestor of nearly<br />

all the modern alphabets of Asia. (Hebrew, Arabic, Brahmic alphabet, etc.) It displaced<br />

cuneiform as the main language and became extinct after Arabic. It is a Semitic language that<br />

does not mark vowels, only consonants.<br />

• Greek alphabet: the Greeks borrowed their alphabet from Phoenician alphabet or could be<br />

from Greeks living in Phoenicia. Earliest Greek alphabet inscriptions are from 730 BC, but it<br />

might have been invented anyw<strong>here</strong> from 1100-800 BC. They changed the Phoenician<br />

alphabet to make it into sounds that are used in Greek, added vowels, and 3 more signs. The<br />

signs for the classic Greek alphabet are known as the Ionian alphabet, compulsory during<br />

403 BC.<br />

• Roman alphabet: The alphabetic link between the Greeks and the Romans are the<br />

Etruscans. The Greeks that went to Italy brought with them the Euboean alphabet during<br />

750 BC, leading to the different scripts used for Greek and Etruscan/Roman. Etruscans<br />

modified the script to change the g sound to the k sound, etc. Then the Roman/Latin script<br />

was modified with 4 more signs and sounds.<br />

• Hebrew alphabet: Known as the script of orthodox Jewry and a national script of modern<br />

Israel. The older one (Old or Paleo-Hebrew) evolved from Phoenician around the 9th<br />

century BC and disappeared from secular use by 6th century. The second script, known as<br />

square Hebrew, evolved from Aramaic (developed in 3rd century). Hebrew is an abjad<br />

without vowels.<br />

• Brahmi alphabet: The Brahmi script is one of the most important writing systems in the<br />

world by virtue of its time depth and influence. It represents the earliest post-Indus corpus of<br />

texts, and some of the earliest historical inscriptions found in India. Most importantly, it is

the ancestor to hundreds of scripts found in South, Southeast, and East Asia. Appeared by<br />

5th century BC. It is syllabic alphabetic, each sign can be a consonant or syllable. It indicates<br />

the same consonant with a different vowel by drawing extra strokes, called matras, attached<br />

to the character. Ligatures are used to indicate consonant clusters.