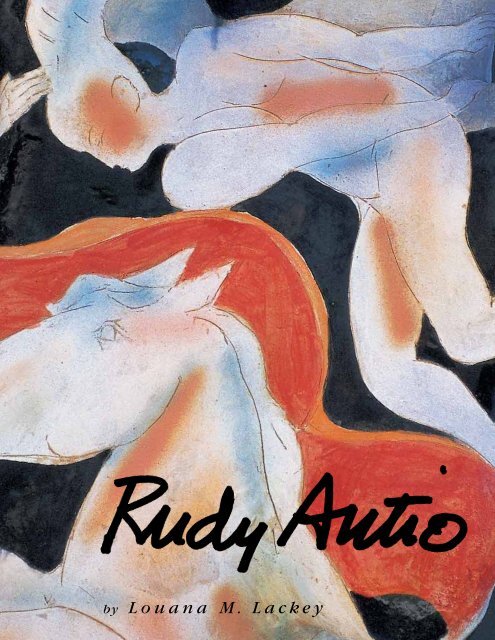

by Louana M. Lackey - Ceramic Arts Daily

by Louana M. Lackey - Ceramic Arts Daily

by Louana M. Lackey - Ceramic Arts Daily

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

y <strong>Louana</strong> M. <strong>Lackey</strong>

y <strong>Louana</strong> M. <strong>Lackey</strong><br />

With A Foreword <strong>by</strong> Peter Voulkos<br />

Published <strong>by</strong><br />

The American <strong>Ceramic</strong> Society<br />

600 North Cleveland Avenue, Suite 210<br />

Westerville, OH 43082<br />

<strong>Ceramic</strong><strong>Arts</strong><strong>Daily</strong>.org

Published <strong>by</strong> The American <strong>Ceramic</strong> Society<br />

600 N. Cleveland Ave., Suite 210<br />

Westerville, OH 43082 USA<br />

http://ceramicartsdaily.org<br />

© 2002, 2013 <strong>by</strong> The American <strong>Ceramic</strong> Society<br />

All rights reserved.<br />

ISBN: 1-57498-144-7 (Cloth bound)<br />

ISBN: 978-1-57498-541-2 (PDF)<br />

No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any<br />

form or <strong>by</strong> any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, microfilming, recording or<br />

otherwise, without written permission from the publisher, except <strong>by</strong> a reviewer, who may<br />

quote brief passages in review.<br />

Authorization to photocopy for internal or personal use beyond the limits of Sections 107<br />

and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law is granted <strong>by</strong> The American <strong>Ceramic</strong> Society, provided<br />

that the appropriate fee is paid directly to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222<br />

Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923 U.S.A., www.copyright.com. Prior to photocopying<br />

items for educational classroom use, please contact Copyright Clearance Center, Inc. This<br />

consent does not extend to copyright items for general distribution or for advertising or<br />

promotional purposes or to republishing items in whole or in part in any work in any format.<br />

Requests for special photocopying permission and reprint requests should be directed to<br />

Director, Publications, The American <strong>Ceramic</strong> Society, 600 N. Cleveland Ave., Westerville,<br />

Ohio 43082 USA.<br />

Every effort has been made to ensure that all the information in this book is accurate. Due<br />

to differing conditions, equipment, tools, and individual skills, the publisher cannot be<br />

responsible for any injuries, losses, and other damages that may result from the use of the<br />

information in this book. Final determination of the suitability of any information, procedure<br />

or product for use contemplated <strong>by</strong> any user, and the manner of that use, is the sole<br />

responsibility of the user. This book is intended for informational purposes only.<br />

The views, opinions and findings contained in this book are those of the author. The<br />

publishers, editors, reviewers and author assume no responsibility or liability for errors or<br />

any consequences arising from the use of the information contained herein. Registered<br />

names and trademarks, etc., used in this publication, even without specific indication<br />

thereof, are not to be considered unprotected <strong>by</strong> the law. Mention of trade names of<br />

commercial products does not constitute endorsement or recommendation for use <strong>by</strong> the<br />

publishers, editors or authors.<br />

Publisher: Charles Spahr, Executive Director, The American <strong>Ceramic</strong> Society<br />

Art Book Program Manager: Bill Jones<br />

Editors: Barbara Case and Susan Sliwicki<br />

eBook Manager: Steve Hecker<br />

Graphic Design: Melissa Bury<br />

Photographs appearing in this book are reprinted courtesy of: Christofer Autio, Lar Autio,<br />

Rudy Autio, Jaap Borgers, Bill Brown, Dave DonTigny, L.H. Jones, <strong>Louana</strong> M. <strong>Lackey</strong>,<br />

Hiromu Narita, Joan K. Prior, Bruce S. Rose, Roger Schreiber, and Howard Skaggs.<br />

Library of Congress Catalog Number: 2002019766

Dedication<br />

To Frederick R. Matson, who introduced me to ceramic studies as an<br />

undergraduate, guided me through the pitfalls of graduate school,<br />

saw me through to the successful completion of my dissertation, and<br />

graciously continues in his role of mentor.<br />

v

Contents<br />

Foreword <strong>by</strong> Peter Voulkos ix<br />

Preface xi<br />

Acknowledgments xiv<br />

Becoming an Artist 1<br />

At the Archie Bray 21<br />

Teaching and Making Art in Missoula 47<br />

An Artist Abroad 79<br />

In the Studio 103<br />

More Time for Art 127<br />

Plates 151<br />

Chronology 247<br />

Appendix 249<br />

Bibliography 255<br />

Index 259

Rudy and Pete, New Jersey, 2000.

BI Know Rudy<br />

eing in Rudy Autio’s presence is to experience the<br />

greatness and humbleness we all seek. The time we’ve<br />

spent together is extraordinary, to put it mildly.<br />

Rudy and I have been friends and colleagues for fifty-five years.<br />

Rudy’s vastly diverse talents, enhanced at times <strong>by</strong> his wife Lela’s<br />

remarks, amazed all. From the beginning we had a lot in common;<br />

we had clay, music, guitars, art, Montana, immigrant parents, new<br />

families, no money, military service, the G.I. Bill, athlete’s foot, and<br />

a passion for making stuff.<br />

At the Archie Bray we also had the chance to collaborate and<br />

build something together. We were the “Kids,” according to Archie.<br />

He called what Rudy made “horses and babes,” and what I made<br />

“ribs, guts, and belly buttons.” We were a good influence on each<br />

other. We had give and take.<br />

Rudy is the consummate artist. I am constantly astounded and<br />

jealous. He can paint, draw, sculpt, and play the accordion; he’s a<br />

real renaissance guy. Our relationship has taught me a world of<br />

ideas. I respect Rudy as one of the finest artists and teachers, and<br />

hold him as my best friend.<br />

Foreword<br />

—Peter Voulkos<br />

ix

At the Archie Bray<br />

A<br />

t the end of Rudy’s first year of graduate school in<br />

1951, he and Lela went back to Montana for the<br />

summer. Lela and their ba<strong>by</strong> stayed in Bozeman with<br />

Bob and Gennie DeWeese while Lela took classes in lithography at<br />

the university. Rudy and Peter Voulkos, who also was back in<br />

Montana after his first year of graduate school, went to Helena<br />

together hoping to find summer jobs and a place where they could<br />

do their work. They found both at the Western Clay Manufacturing<br />

Shoji Hamada decorating a bowl at the Archie Bray, 1952.

Company in Helena. The firm’s owner, Archie Bray, hired both of<br />

them to work in his brickyard and to help him build a pottery for the<br />

art center he wanted to start.<br />

Archie Bray was not just a simple maker of brick. He had a<br />

degree in ceramic engineering from the Ohio State University, and<br />

he played the piano, sponsored concerts and theater productions,<br />

Hank Meloy, with his portrait of his brother,<br />

Peter, ca. 1951.<br />

22<br />

RUDY AUTIO<br />

and owned a modest art col-<br />

lection. Archie dreamed of<br />

building a place where artists<br />

and musicians could work,<br />

and he talked about his idea<br />

of an art center with his<br />

friends—Branson Stevenson,<br />

and Peter and Henry Meloy.<br />

All three were enthusiastic<br />

about the idea. Stevenson, an<br />

oil company executive, was<br />

an amateur artist. Peter Meloy<br />

and his brother Henry Meloy,<br />

were interested in pottery.<br />

Pete was an attorney in<br />

Helena and an amateur potter.<br />

Henry “Hank” Meloy taught<br />

painting and life drawing at<br />

Columbia University in New<br />

York City, and returned to Helena in the summers to make pottery<br />

with his brother. The Meloys had unsuccessfully tried to build a kiln

At the Archie Bray<br />

on their ranch, so Archie had been letting them fire their pots on top<br />

of the bricks in his brick kiln. The first phase of the projected art<br />

center would be a pottery. The projected center would begin with<br />

ceramics. Painting, sculpture, weaving, and possibly, a music<br />

conservatory could be added later.<br />

A high-school friend of Rudy’s, Kelly Wong, who had also<br />

studied art at Bozeman, joined Rudy and Pete in the brickyard. The<br />

three worked from early morning until late at night. They shoveled<br />

raw clay onto conveyer belts to be crushed and fed into the pugmill;<br />

they sometimes would relieve the regular “nippers” to pick up brick<br />

as it came from the extruder; at other times, they were assigned to<br />

help with the firing. When they weren’t working in the brickyard,<br />

they laid brick for the new pottery. They did not labor alone at this;<br />

Pete Meloy and many other volunteers helped to build the pottery.<br />

Frances Senska (1982:35) reports that “So many eager amateurs laid<br />

brick for those walls, it’s a wonder they remain standing. But the<br />

experts managed to compensate for the wavering rows, and the roof<br />

plate landed on a level course.” By all working together, they man-<br />

aged to construct a building with a showroom, a workroom, and<br />

rooms for clay mixing, glazing, and kilns. When the pottery was fin-<br />

ished, Archie and Peter Voulkos built a large downdraft kiln for high-<br />

fire reduction wares, the first gas-fired kiln in the state. Under<br />

Archie’s guidance, Rudy built the twenty-five-foot chimney stack.<br />

While they were building the pottery, Rudy, Pete, and Kelly did their<br />

own work at night in a corner of the tile-drying shed. Pete made<br />

pots on the wheel while Rudy made hand-built sculptures <strong>by</strong> coiling<br />

shapes together. Until the new kilns were built, they fired their work<br />

23

Lela Autio, 1952.<br />

24<br />

RUDY AUTIO<br />

on top of the brick in the big beehive kilns, just as the Meloys had<br />

done earlier. That first summer at the Bray, Rudy and Pete shared a<br />

shack with Kelly behind the present pottery building.<br />

The following summer, 1952, after Rudy and Peter Voulkos<br />

finished graduate school, they returned to the Bray as resident artists.<br />

Rudy and Lela bought a small house in Helena, and Pete and Peggy<br />

Voulkos moved into an old chicken house behind the pottery.<br />

Although Archie paid Rudy and Pete a modest wage, money from<br />

the sale of their work was used to help sup-<br />

port the pottery.<br />

Rudy and Pete and the other resident pot-<br />

ters made work for the shop—gift store items<br />

such as planters, fruit bowls, and nut dish-<br />

es—nothing that could be called art. They<br />

had barely enough money to live on, and<br />

Rudy says he still doesn’t know how Lela<br />

made do on his small salary.<br />

Lela and Peggy made enameled ashtrays<br />

for the shop and taught pottery classes. Lela<br />

found some of the customers and students<br />

difficult to deal with:<br />

A lot of rich people would come and look at<br />

the stuff, but they would never buy anything,<br />

and that made it difficult. Sometimes the rich<br />

people would come and work there and then<br />

they’d leave and write letters and ask us to<br />

glaze all their stuff and send it on and send us<br />

a ten-dollar bill.

Lela continued to do her own work <strong>by</strong> painting in an attic studio of<br />

their little house, and she also painted sets for theater productions.<br />

Helena’s active arts community included painting, pottery, music,<br />

theater, and even ballet. There were parties with home brew, and<br />

guitar music played <strong>by</strong> Rudy, Pete, Peter Meloy, and the DeWeeses.<br />

Poor as they were, Rudy and Lela found Helena an interesting place<br />

to live.<br />

Hamada, Leach, and Yanagi<br />

At the Archie Bray<br />

Rudy and Pete, Helena, Montana, 1953.<br />

That fall, the first of many workshops held at the Bray, and probably<br />

the most famous, was given <strong>by</strong> Bernard Leach, Shoji Hamada, and<br />

Soetsu Yanagi. Bernard Leach, who had been born in Hong Kong<br />

and had studied in Japan, explained the philosophy of the humble<br />

25

Peter Voulkos, Rudy, and Pete Meloy watching Shoji<br />

Hamada’s demonstration at the Archie Bray, 1952.<br />

26<br />

RUDY AUTIO<br />

potter whose roots were in the<br />

earth, and who found great satis-<br />

faction in the repeated making of<br />

pottery objects. Leach had philo-<br />

sophical support from Soetsu<br />

Yanagi. Yanagi, a visiting lecturer<br />

in Zen philosophy at Harvard, dis-<br />

cussed the “thusness” of Korean<br />

wood turning—just letting it hap-<br />

pen—as compared with Japanese<br />

wood turning, which was so pre-<br />

cise, so exact, and so perfectly<br />

done that it lost its spirit. It was all a new experience for the native<br />

Montanans. For Rudy, who later confessed that he had some prob-<br />

lems with Bernard Leach as a “humble potter,” Yanagi’s lectures on<br />

Zen were liberating ideas. He thought Dr. Yanagi was “very interest-<br />

ing, insightful, an aesthetician. He talked about Zen. We had never,<br />

ever heard about Zen.” Although Rudy didn’t entirely accept this<br />

philosophy, he began to understand the way of thinking that is the<br />

essence of Zen. Hamada was a “doer” whose workshop had a pro-<br />

found and lasting effect upon Rudy. Watching Hamada work was a<br />

great revelation; at this point in his life Rudy really didn’t think<br />

much about clay, it was just something you made nut dishes, knick-<br />

knacks, and pottery dishes out of. But Rudy was especially<br />

impressed when Hamada demonstrated how to throw off the hump.<br />

Shoji could take a lump of clay and throw a whole teapot set off<br />

of one lump of clay, and we admired that ancient technique. Most<br />

of all, though, I think that I began to discover that pottery making

Rudy watching Hamada trim a bowl.<br />

was not just a matter of throwing pots and selling them in the<br />

trade world, but from the way he handled things and examined<br />

them, turned them around, held them, and communicated with<br />

the work that he was doing, I began to sense that there was a kind<br />

of a spiritual connection to it, that it was more than just making a<br />

pot to make a few bucks on the sale.<br />

To see someone like Hamada working with it was to infuse it with<br />

a spirit that was as good as anything that could happen in painting<br />

or drawing and fine arts. I could see that in Japanese eyes this was<br />

a very important, almost a spiritual kind of experience when they<br />

worked with clay. The economy of move ment, everything that he<br />

did, the way he considered the piece before he painted on it. All<br />

of those things had great impact on me.<br />

For a while Rudy even tried to throw like Hamada, and he<br />

believes that the experience made a lot of difference in the way he<br />

approached working with clay.<br />

At the Archie Bray<br />

27

Archie Bray, 1952.<br />

28<br />

Change in Leadership<br />

RUDY AUTIO<br />

In the winter of 1953, as work continued on the arts center build-<br />

ings, Archie was injured in the brickyard. Then he developed pneu-<br />

monia and other complications. Two weeks later his son, Archie Jr.,<br />

came to see Rudy in the drying shed where he was pressing clay, and<br />

told him “The old man is gone.” Rudy was stunned. For a while, it<br />

looked as though the foundation would be buried with Archie. But<br />

then, according to Senska and Douglas<br />

(1993), “Archie Bray, Jr., who took over the<br />

management of the brickyard, kept it up at<br />

the insistence of his mother and sister. The<br />

brickyard continued to absorb the overhead.”<br />

Rudy remembers the relief he felt:<br />

Archie Jr., whom we all felt was against all<br />

this foolishness in the brickyard—pottery,<br />

bohemians, artists, and everything else we<br />

stood for—said he wanted to carry on the<br />

work his dad had started, and told me he<br />

wanted me and Pete to stay as long as we<br />

wanted—to carry on the work of the Archie<br />

Bray Foundation. It seemed that we’d just<br />

gotten things going. Things looked pretty<br />

gloomy. As I look back on that day, it’s possible that if Archie<br />

hadn’t died, things may not have continued.<br />

With the future of the Bray assured, other workshops followed<br />

that of Hamada, Leach, and Yanagi. Among the visitors were Rex<br />

Mason, a potter from San Francisco; Marguerite Wildenhain, also<br />

from California, and one of Frances Senska’s teachers, who drew an

enormous crowd; and Tony Prieto, who taught<br />

at Mills College. There were many others, and<br />

Rudy learned from them all. He says that<br />

Tony Prieto<br />

was full of hell, and taught me a lot of things<br />

about firing and glaze application as well as<br />

surface decoration. He communicated ideas<br />

about his contact with Artigas, the Spanish potter,<br />

and Miró, who was starting to work with<br />

clay. Tony would periodically visit them in<br />

Spain.<br />

Rudy learned a great deal about high-temperature<br />

glazes from Carlton Ball who worked<br />

at the Bray one summer on a Ford Foundation<br />

grant. Rudy thought Carlton was a great guy:<br />

He could throw very well; he taught us a lot of<br />

wonderful, simple things about glazes—you<br />

can do this, add feldspar to this; a lot of wonderful<br />

simple things to do with materials. I think<br />

I learned from him that there was a sense of<br />

experimenting, and trying, and testing and all<br />

kinds of things that are importantly related to<br />

anyone working in clay. Carlton taught us that.<br />

He was very generous with his information, no<br />

secretiveness like a lot of potters.<br />

Working on a Bigger Scale<br />

At the Archie Bray<br />

Three Musicians, 1952.<br />

21 in. 14 in. 14 in.<br />

Aside from the production work Rudy did for the shop, most of his<br />

work at the Bray was sculptural. Examples include Three Musicians<br />

and his large, salt-glazed bust, Archie Bray, now installed in Robert<br />

Harrison’s Potters’ Shrine on the grounds of the Archie Bray Foundation.<br />

The bust was fired in a salt firing on top of the bricks in the brick kiln.<br />

29

30<br />

RUDY AUTIO<br />

Rudy also had begun to make small, decorative architectural<br />

pieces, such as plaques, that the brickyard gave away with orders for<br />

brick. Many of these plaques were designed for fireplaces; others,<br />

designed for a kindergarten, were based on fairy tales and nursery<br />

rhymes. Rudy’s plaques with various decorative motifs were shipped<br />

all over Montana. He even created a bison skull and recreated<br />

Charlie Russell’s signature on a plaque he made for the C.M. Russell<br />

Gallery in Great Falls. He remembers, “The bison’s skull was an idea<br />

foisted on me <strong>by</strong> Branson Stevenson. I hated it, but finally made the<br />

damned thing.” He had had problems; his clay was full of grog and<br />

difficult to work with, and he made about fifteen attempts—pound-<br />

ing about fifteen molds—before he finally patched one together.<br />

One of Rudy’s earliest large architectural commissions was done<br />

in 1953 for the south face of the Liberal <strong>Arts</strong> Building at the<br />

University of Montana. This large, circular, terra cotta medallion has<br />

a relief of a Native American writing on a skin. Archie, Jr. asked<br />

Rudy to design the medallion using traditional terra cotta tech-<br />

niques. These techniques would serve Rudy well in his later work.<br />

First, he created a design showing a Native American intent upon<br />

writing. Then he made the medallion in plaster and cast it some nine<br />

and a half feet in diameter, to allow for shrinkage to the<br />

finished size of eight feet. Then Rudy divided the medallion into<br />

twenty-four sections and cast a negative mold of each section. Next,<br />

he pounded clay into these press molds. Rudy removed the clay<br />

when it was leather-hard <strong>by</strong> inverting the molds onto plywood bats.<br />

Finally, he touched up the sections and smoothed them with a trow-<br />

el. Peter Voulkos helped develop colors and glazes for the piece,<br />

which is still in place on the university campus at Missoula.<br />

Through his work at the brickyard, Rudy developed a technique

At the Archie Bray<br />

Medallion, Liberal <strong>Arts</strong> building, University of Montana, 1953.<br />

that he was to use again and again. He noticed that one method of<br />

making decorative brick was to carve fired brick, and he wondered<br />

why the technique couldn’t be used with unfired brick. So he<br />

removed some of the cutting wires from the brick-cutting machine so<br />

that he could make large blocks rather than individual bricks. He<br />

used this technique to make a large relief, Sermon on the Mount, ten<br />

feet tall and thirty feet wide, which he designed for the First<br />

Methodist Church in Great Falls, Montana in 1954. Unfired bricks of<br />

clay measuring 3 1 ⁄2 in. <strong>by</strong> 8 in. <strong>by</strong> 9 in. were set on easels that<br />

leaned just enough to keep them in place. After carving the blocks,<br />

31

32<br />

RUDY AUTIO<br />

Sermon on the Mount, 1954. Carved-brick relief, 10 ft. 30 ft., First Methodist<br />

Church, Great Falls, Montana.<br />

Rudy stained them <strong>by</strong> rubbing iron oxide into them and, after they<br />

dried, sprayed them with borax to seal the stain. Next the blocks<br />

were numbered for placement on the wall, fired in the brick kilns at<br />

the brickyard, and installed at the church <strong>by</strong> brick masons. Christ is<br />

portrayed preaching to the multitudes with His arms outstretched,<br />

and a self-portrait of the artist can be seen in front. Several of Rudy’s

At the Archie Bray<br />

friends also can be seen in the crowd, including Peter Voulkos and<br />

Cyril Conrad, Rudy’s advisor at Bozeman. The carved figures are<br />

blocky, echoing the form of the brick, and giving a linear feeling that<br />

carried a swinging movement across the thirty-foot wall it covered.<br />

Both Rudy and Peter Voulkos had been experimenting with new<br />

techniques, and they each entered work in the Eighth National<br />

Wichita Decorative <strong>Arts</strong>—<strong>Ceramic</strong> Exhibition. Rudy’s ceramic<br />

33

34<br />

RUDY AUTIO<br />

Bird and Egg, early 1950s. Stoneware, 13 in. 23 1 ⁄2 in. 9 3 ⁄4 in.<br />

sculpture, Bird and Egg, is pictured in <strong>Ceramic</strong>s Monthly on page 19<br />

of its July 1953 issue. Pete took first prize for a brown- and gray-<br />

flecked tureen with wax-resist decoration pictured on the facing<br />

page of the same issue. Pete had made wax resist very popular with<br />

potters at the Bray after Branson Stevenson brought them a new<br />

liquid wax emulsion that made the process very easy. Rudy tried

the technique on a few pots, and took full advantage of it in a large<br />

repeat motif wall mural he designed for the C.M. Russell Gallery in<br />

Great Falls in 1957. The committee rejected Rudy’s original pro-pos-<br />

al, a wall of running horses. Rudy then designed a mural sixteen feet<br />

tall <strong>by</strong> thirty feet wide, based on a stone with Native American pic-<br />

tographic writing. The pattern on the stone is thought to be a maze<br />

meant to confuse evil spirits, to keep them from finding burial<br />

grounds in eastern Montana. The overall pattern of this work is a<br />

checkerboard with tiles alternating in black and natural terra cotta.<br />

He scratched in the line drawing, and inlaid the design in white<br />

engobe, using the new wax-resist<br />

process. Rudy then fired the hol-<br />

low construction tiles to cone<br />

one in the brickyard kilns.<br />

For Peter Voulkos, the year<br />

1953 was a turning point. His<br />

At the Archie Bray<br />

Mural, 1957. Glazed and unglazed<br />

terra cotta, 16 ft. 30 ft. C.M.<br />

Russell Gallery, Great Falls,<br />

Montana.<br />

35

36<br />

RUDY AUTIO<br />

work had begun to change shortly after he returned from giving a<br />

three-week summer workshop at Black Mountain College in North<br />

Carolina. At Black Mountain, Pete “acquired a fresh outlook on art<br />

and an attitude toward experimentation that were to release his own<br />

adventurous spirit and fierce energies” (Slivka and Tsujimoto 1995:<br />

37). After Black Mountain, he visited New York, and was exposed to<br />

the heady atmosphere of Abstract Expressionism. His classical pots<br />

of the early fifties were now replaced <strong>by</strong> large, dramatically shaped<br />

and dramatically made forms—forms that were torn, flattened, com-<br />

bined, and recombined. He returned to the Bray at the end of the<br />

summer but spent only a few more months there. When Pete was<br />

offered an opportunity to set up a new ceramics department at the<br />

Otis Art Institute in Los Angeles, he and Peggy and their young<br />

daughter, Pier, left Helena and the Bray in August 1954.<br />

Rudy was kept busy with architectural commissions. In 1955 he<br />

designed a large (eighteen feet <strong>by</strong> thirty feet) carved brick, terra cotta<br />

wall relief, Christ and the Disciples, for the Hope Lutheran Church,<br />

in Anaconda, Montana. Rudy felt that the project had lost some of its<br />

integrity because it was separated <strong>by</strong> a glass wall. That same year, he<br />

made a series of stoneware reliefs, Fourteen Stations of the Cross, for<br />

Saint Gabriel’s Catholic Church, in Chinook, Montana. This series of<br />

partly glazed, 20 in.-square, stoneware reliefs, shows Christ’s journey<br />

to the cross. As part of this commission Rudy also made a relief of<br />

the Crucifixion for the central altar area.<br />

In 1956, Rudy was asked to create a relief for an exterior wall of<br />

the Glacier County Library in Cutbank, Montana. He made a terra<br />

cotta relief twelve feet high and four feet wide, partly glazed in

white, turquoise, and light blue, along with<br />

the natural terra cotta tiles. For the design,<br />

Rudy chose animals symbolizing three peri-<br />

ods in the history of the lands of the<br />

Blackfeet: a bison to symbolize prehistory, a<br />

horse for exploration, and an ox for the early<br />

settlement of the west. Contours of the hol-<br />

low, hand-built sections of the relief follow<br />

the curves of the animals’ figures. Rudy was<br />

to use this technique to emphasize important<br />

lines and curves in his compositions again<br />

and again in later reliefs and wall murals.<br />

Although Rudy spent most of his time on<br />

large commissions or clay sculpture, he con-<br />

tinued to make a few pots for sale in the<br />

shop. Lela continued to paint at home, but<br />

she also was at the Bray much of the time<br />

teaching classes and making enameled ware.<br />

Interesting people came to the pottery all the<br />

time—as students, as residents, to give dem-<br />

onstrations and workshops and, of course, to<br />

buy its ceramics.<br />

At the Archie Bray<br />

The Montana Historical Society<br />

Museum<br />

Except for his architectural commissions,<br />

Rudy did not earn very much at the brick-<br />

yard. Fortunately, just when he needed money<br />

Exterior Wall Relief, 1956. Glazed terra<br />

cotta, 12 ft. 4 ft. Glacier County Library,<br />

Cutbank, Montana.<br />

37

38<br />

for a new car, he found temporary work. The Montana Historical<br />

Society, one of the institutions that contributed to the teeming cul-<br />

tural activity in Helena, had built a new museum building on the<br />

grounds of the State Capitol and had hired K. Ross Toole as its direc-<br />

tor. Toole was young, energetic, and ambitious. In his first three<br />

years at the museum, while finishing his doctoral dissertation in his-<br />

tory at U.C.L.A., Toole began to implement his plans for the muse-<br />

um. These included permanent exhibits with dioramas depicting the<br />

development of the West. For these Toole needed artists. Peter<br />

Meloy, a volunteer director of the museum, was in a position to<br />

make recommendations, so he introduced Toole to Rudy. Meeting<br />

Toole solved Rudy’s immediate financial crisis, and was to have<br />

long-term importance.<br />

RUDY AUTIO<br />

Toole hired several other artists, including Gardell Christiansen,<br />

Robert DeWeese, Shorty Shope, Clarence Zuehlke, and John Weaver.<br />

With help from the museum staff, these artists and craftsmen made<br />

most of the dioramas in the museum. John Weaver, a sculptor who had<br />

studied at the Chicago Art Institute, was the son of “Pop” Weaver,<br />

Rudy’s high-school art teacher. Rudy remembers that<br />

Weaver had an uncanny ability to cast plaster into all kinds of<br />

unbelievable objects—horses, cars, figures—so he also began to<br />

make a series of dioramas based on the oil industry, which donated<br />

funds for the making of their series of exhibition cases.<br />

Gardell Christiansen created a dramatic and very popular exhibit<br />

of a bison drive that showed bison being driven over a cliff, hanging<br />

in mid-air, and falling, as Native American hunters chased them to<br />

their deaths. The fact that none of the suspension wires could be<br />

seen added to the effect. Christiansen also made, fired, and painted

At the Archie Bray<br />

several terra cotta figures at the Bray to use for dioramas of Native<br />

American costume and related exhibits.<br />

Rudy was assigned the task of making a large Lewis and Clark<br />

diorama. Toole wanted him to illustrate the expedition on the day in<br />

1805 when Lewis set out to discover a route to the Pacific while<br />

Clark was left behind with a larger group to reconnoiter the head-<br />

waters of the Missouri. Rudy was no expert on dioramas.<br />

In fact, I’d never even heard of them. The dioramas he had in mind<br />

were exhibits showing bucking broncos, wild buffalo exhibits,<br />

scenes from Virginia City—small accurate models of buildings—a<br />

kind of childlike fantasyland with exhibits of various kinds. I had<br />

no skills along these lines, but I was confident I could model<br />

Lewis and Clark diorama, 1954. Mixed media, 7 ft. 10 ft. 9 ft. Montana<br />

State Historical Society Museum, Helena, Montana.<br />

39

40<br />

RUDY AUTIO<br />

figures. After looking at the painful efforts of some of the artists<br />

Ross had hired earlier, I knew it wouldn’t be difficult, so I modeled<br />

some sample studies. Ross loved the studies and his staff was joyous.<br />

Here was an artist who could create the figures they needed.<br />

The historical society did the research for Rudy, who took leave<br />

from the Bray for the project. He began <strong>by</strong> developing the figures<br />

from beeswax. They started to take shape at home where he could<br />

keep the beeswax warm and malleable on the kitchen stove. For<br />

weeks afterward, Lela worked to get the stove burners unclogged.<br />

Rudy later switched to petroleum wax, which was easier to model<br />

than beeswax and didn’t crystallize or become moldy. He constructed<br />

the figures over wire armatures, which made them rigid enough to<br />

place into position in the exhibit. In addition to modeling the figures<br />

with authentic costumes, Rudy had to paint the diorama, model its<br />

landscape, and fill it with figures, canoes, tents, camping gear—the<br />

works. He did a great deal of improvising to build ground forms, riv-<br />

ers, and canoes, and to find indigenous grasses and colorful material<br />

typical of the site on the Beaverhead. Muriel Guest from the Bray and<br />

Bob Morgan helped him with some of the basic work. Morgan was a<br />

sign painter and exhibits designer who later became a popular wild-<br />

life artist. Les Peters, also a wildlife painter who had a good sense of<br />

the western landscape, painted the background, successfully merging<br />

it with the foreground and the three-dimensional figures.<br />

People began to drop <strong>by</strong> to watch the progress of the work.<br />

Once the figures of the Lewis and Clark expedition were finished<br />

and painted, they were put into place in the exhibit. When the<br />

exhibit was finally finished, it was seven feet high, ten feet wide,<br />

and nine feet deep. Rudy describes the scene, which depicted

Captain Clark taking a compass reading as he waves farewell to a<br />

group of three men in the middle distance. Sergeant York, Clark’s<br />

manservant, held a map of the area beside him. Sacagawea, with<br />

her papoose on her back, sat cross-legged on the slope near the<br />

hunter who was carrying into camp a deer he shot that morning.<br />

In the middle distance the party of three—Lewis, Shannon, and<br />

Charbonno, with Scanlon, the Labrador dog—were setting out to<br />

find the Shoshones. Under a small hummock in the foreground I<br />

made a little mouse for my daughter Lisa, who couldn’t see above<br />

the sill, being only three years old at the time, but it was for her<br />

and the other little kids to look at.<br />

Rudy had been happy working at the museum, but his work was<br />

finished. He went back to the Bray where he found that things had<br />

not been going well. The new tunnel kiln at the brickyard was a<br />

disaster, and Archie Jr. was losing money. He and Rudy had had an<br />

understanding that they would split any net profit from the pottery at<br />

the end of the year. Rudy’s books showed a profit of $3,000, but<br />

the bookkeeper’s records of the pottery’s accounts showed a loss.<br />

When the discrepancy was discovered, the bookkeeper was fired.<br />

Rudy began to think about moving. His family was always on the<br />

edge of financial disaster, and he was desperate. He didn’t know<br />

where to turn.<br />

At the Archie Bray<br />

Leaving the Bray<br />

Peter Voulkos had urged Rudy to come to California to make archi-<br />

tectural ceramics, so Rudy finally wrote to Pete to say he was com-<br />

ing. Pete was becoming increasingly well known and successful in<br />

California, and Rudy wanted to get in on the good life too. So, one<br />

bitterly cold day in the winter of 1956–57, Rudy kissed Lela and his<br />

children good<strong>by</strong>e, promised to send money as soon as he could,<br />

and set off for California in his rickety old truck. He moved in with<br />

41

42<br />

Pete and Peggy Voulkos and “tried not to eat too much” while he<br />

looked for a job.<br />

For Rudy, California was no promised land. He found a part-time<br />

job in Whittier setting bricks into kilns at the Advanced Kiln<br />

Company for a friend, Mike Kalan. Meanwhile he continued to<br />

search for a way to work at his art. He made some designs for<br />

stained-glass windows for a synagogue, but they weren’t accepted.<br />

He sat in line with many other artists, trying to make connections<br />

with architects. He had sample photos of his carved-brick reliefs,<br />

and some designers expressed interest, but Rudy couldn’t afford to<br />

leave a portfolio. Engineers at a plant in Pasadena interviewed him<br />

and offered him a job doing their lab work, but he seemed to be<br />

getting farther and farther away from art. Another job prospect was<br />

being a foreman in a ceramic plant, supervising the manufacture of<br />

electrical parts. Rudy turned it down: “I don’t think I would’ve made<br />

a good foreman.”<br />

RUDY AUTIO<br />

The last straw came one day as Rudy was turning off the freeway<br />

exit to Whittier on his way to the Advanced Kiln Company:<br />

A motorcycle cop pulled me over just to inspect my poor old<br />

1941 pickup truck. Everything worked on it, thank God—wipers,<br />

brakes—but it was an old truck that didn’t have turn signals. I got<br />

a warning to take it to a state traffic inspector for a check. This was<br />

the end. I was homesick. I missed my kids. I had no money. I<br />

called Ross Toole and asked him for a job at the Historical Society.<br />

Ross said, “Come on home.” He wired me a hundred dollars. So<br />

I drove home and ended my big California adventure.<br />

Meanwhile back in Helena, Lela was having her own problems:<br />

It was a horrible winter, and all the pipes froze and it was about fifty<br />

below, and the kids got chickenpox and measles, and my dad had<br />

to come and help us because we were having such a horrible time.

At the Archie Bray<br />

Rudy rejoined the museum in Helena as an assistant curator,<br />

although the position was only part-time and temporary. Rudy had<br />

given the brickyard notice before he went to California, so he decided<br />

to work freelance from his own studio, but in cooperation with the<br />

brickyard. Archie Jr. agreed to the idea. One of Rudy’s college room-<br />

mates at Bozeman, Harold Godtland, who had become an architect,<br />

asked him to design a carved-brick relief, Christ Surrounded <strong>by</strong><br />

Children, for the Gold Hill Lutheran Church in Butte. Working at<br />

home, Rudy made a carved plaster model to present to the commit-<br />

tee. He envisioned a monumental figure of Christ facing the children<br />

as He blessed them, with the figures concentrated into the shape of a<br />

cross, and framed <strong>by</strong> areas of glazed tiles at the corners. It took sever-<br />

al weeks and many studies, but he received the commission.<br />

Rudy used unfired clay blocks for the project and rubbed iron<br />

oxide and rutile stain into them after they were carved in order to<br />

highlight the carving. The relief was then partly glazed with borax<br />

and fired to cone one in the brick kilns. Rudy thought it was a perfect<br />

job technically. The blocks had fired well in the brick kilns at the<br />

Bray, and the glaze also had worked well. One of Rudy’s friends from<br />

the museum staff, Clarence Zuehlke, went to Butte to help him install<br />

the sixteen- <strong>by</strong> eighteen-foot relief on an exterior wall of the church’s<br />

educational wing. The shape fit the space exactly as planned. The<br />

Gold Hill relief was Rudy’s last architectural project while he and his<br />

family lived in Helena. With no new projects or commissions in<br />

sight, Rudy once again began to look for a teaching position for the<br />

fall of 1957. Once again, Ross Toole came to the rescue.<br />

43

44<br />

RUDY AUTIO<br />

Christ Surrounded <strong>by</strong> Children, 1956. Carved brick, 16 ft. 18 ft., Gold Hill<br />

Lutheran Church, Butte, Montana.

Carl McFarland, president of the University of Montana, was<br />

looking for someone to start a ceramics program, and he asked Ross<br />

Toole if he knew a good potter. Toole answered that he knew “the<br />

best one in the whole world” (Pietala, I977: A2). Carl McFarland<br />

remembered Rudy from his days at the Bray, four years earlier, when<br />

he had chosen Rudy’s design for the medallion for the Liberal <strong>Arts</strong><br />

Building at the university. Now McFarland thought that Rudy could<br />

start a ceramics department, teach, and also add ceramic decora-<br />

tions to some of the other campus buildings, starting with studies for<br />

the Main Hall, and the old science building; later, possibly, he might<br />

do some terra cotta murals for the planetarium based on Native<br />

American star legends. McFarland offered Rudy the rank of<br />

Instructor at Missoula with a starting salary of $550 a month. Rudy<br />

accepted, not realizing that the way he had been recruited was<br />

extremely irregular: McFarland had circumvented all the written and<br />

unwritten rules and rituals of academic hiring practice. Little wonder<br />

that the Art Department faculty was cool to Rudy when he arrived,<br />

and for a long time afterward.<br />

At the Archie Bray<br />

45