Winter 99/00 - Petroleum Engineering | The University of Oklahoma

Winter 99/00 - Petroleum Engineering | The University of Oklahoma

Winter 99/00 - Petroleum Engineering | The University of Oklahoma

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

OU Discovery<br />

School <strong>of</strong> <strong>Petroleum</strong> and Geological <strong>Engineering</strong><br />

our pr<strong>of</strong>essional development in a very<br />

paternalistic fashion. That viewpoint<br />

does not work any more. We have to<br />

take charge <strong>of</strong> our own continuing<br />

education. We, as individuals, must be<br />

proactive in ensuring that we remain<br />

technically current if we want to stay<br />

competitive and provide added value<br />

to our employer, which is what we are<br />

paid for.<br />

This is where the interconnective<br />

“umbilical cord” comes in. Our<br />

universities can help us remain up to<br />

date; they must also be effective in<br />

providing the right pr<strong>of</strong>essional for our<br />

industry. Industry, <strong>of</strong> course, will<br />

provide the specific training that may<br />

be required for a certain job. SPE can<br />

help members move in this direction<br />

and provide them with the international<br />

perspective that is so important<br />

in today’s world <strong>of</strong> globalized economies<br />

and industries.<br />

To put this in perspective, I refer to<br />

an article that circulated in the mid-<br />

1960s. <strong>The</strong> article, written by George A.<br />

Hawkins, who was dean <strong>of</strong> <strong>Engineering</strong><br />

at Purdue <strong>University</strong> at the time,<br />

appeared in Engineer magazine (1966-<br />

67, Volume 7, No. 4). <strong>The</strong> article called<br />

this obsolescence process “the four ages<br />

<strong>of</strong> an engineer.” Hawkins’ point was<br />

that it is a costly mistake not to recognize<br />

that maintaining our technical<br />

knowledge is a lifelong process and<br />

that the solution requires a great deal <strong>of</strong><br />

self-discipline.<br />

Our complaints about our knowledge<br />

requirements and the fault with<br />

university education can be divided<br />

into four periods after graduation.<br />

According to Hawkins, after between<br />

one and five years after graduation, the<br />

engineer would like to have had more<br />

practical courses. <strong>The</strong> young engineer<br />

becomes impatient because he or she<br />

cannot solve the practical problems<br />

that the experienced engineer can<br />

solve. After five to 12 years, engineers<br />

wish for greater competence in the<br />

basic sciences - math, physics, chemistry<br />

- because they lack the knowledge<br />

to solve difficult engineering problems.<br />

<strong>The</strong> engineer begins to show a lack <strong>of</strong><br />

newer scientific and theoretical<br />

knowledge.<br />

After 12 to 25 years, engineers require<br />

more administrative and managerial<br />

knowledge - speech and report writing,<br />

industrial relations, finance. <strong>The</strong><br />

mature engineer realizes that she or he<br />

needs not only the technical knowhow<br />

but also supervisory, administrative<br />

and managerial skills. After 25<br />

years, the engineer becomes more<br />

philosophical and may desire to know<br />

more about the arts, music, literature,<br />

and drama. As they approach retirement,<br />

some may admit to a total lack <strong>of</strong><br />

cultural activities.<br />

Hawkins quite rightly identifies<br />

these four stages. Each requires<br />

specialized knowledge and skills.<br />

Certainly, no engineering program can<br />

prepare its graduates for the next 40 or<br />

50 years <strong>of</strong> pr<strong>of</strong>essional life. Hawkins<br />

believes that it is totally inappropriate<br />

to talk <strong>of</strong> not being technically competent<br />

some 10 years after graduation,<br />

when the process really starts the<br />

moment we graduate.<br />

Hawkins’ article was written more<br />

than 30 years ago. <strong>The</strong> rapidity with<br />

which technology is now being<br />

developed, and changing our ways <strong>of</strong><br />

thinking and working, reduces those<br />

first 10 years substantially. We can<br />

become obsolete a lot more quickly<br />

now. My message to younger engineers<br />

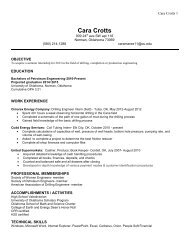

Inciarte with <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Oklahoma</strong> President David Boren and other<br />

<strong>University</strong> dignitaries at the signing ceremony <strong>of</strong> the Charter for the Energy<br />

Institute <strong>of</strong> the Americas on May 12, 1<strong>99</strong>5 in President Boren’s <strong>of</strong>fice.<br />

is to let your pr<strong>of</strong>essional society, your<br />

company, and your university help you<br />

defeat the obsolescence process. Keep<br />

yourself up to date not only technically<br />

but also in your total pr<strong>of</strong>essional and<br />

life development. Remember, it is not<br />

one instead <strong>of</strong> another, but a different<br />

emphasis at different stages <strong>of</strong> your life.<br />

continued on page 6<br />

5