United States Court of Appeals

United States Court of Appeals

United States Court of Appeals

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

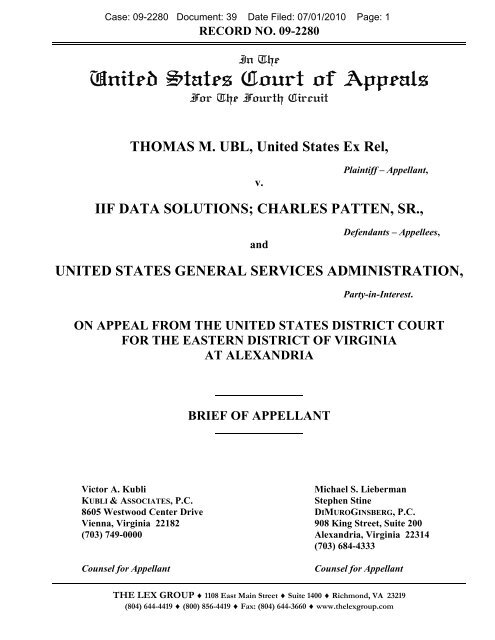

Case: 09-2280 Document: 39 Date Filed: 07/01/2010 Page: 1<br />

RECORD NO. 09-2280<br />

In The<br />

<strong>United</strong> <strong>States</strong> <strong>Court</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Appeals</strong><br />

For The Fourth Circuit<br />

THOMAS M. UBL, <strong>United</strong> <strong>States</strong> Ex Rel,<br />

v.<br />

Plaintiff – Appellant,<br />

IIF DATA SOLUTIONS; CHARLES PATTEN, SR.,<br />

and<br />

Defendants – Appellees,<br />

UNITED STATES GENERAL SERVICES ADMINISTRATION,<br />

Party-in-Interest.<br />

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT<br />

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF VIRGINIA<br />

AT ALEXANDRIA<br />

BRIEF OF APPELLANT<br />

Victor A. Kubli Michael S. Lieberman<br />

KUBLI & ASSOCIATES, P.C. Stephen Stine<br />

8605 Westwood Center Drive DIMUROGINSBERG, P.C.<br />

Vienna, Virginia 22182 908 King Street, Suite 200<br />

(703) 749-0000 Alexandria, Virginia 22314<br />

(703) 684-4333<br />

Counsel for Appellant Counsel for Appellant<br />

THE LEX GROUP ♦ 1108 East Main Street ♦ Suite 1400 ♦ Richmond, VA 23219<br />

(804) 644-4419 ♦ (800) 856-4419 ♦ Fax: (804) 644-3660 ♦ www.thelexgroup.com

Case: 09-2280 Document: 39 9 Date Filed: 07/01/2010 12/03/2009 Page: 21<br />

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT<br />

DISCLOSURE OF CORPORATE AFFILIATIONS AND OTHER INTERESTS<br />

Only one form needs to be completed for a party even if the party is represented by more than<br />

one attorney. Disclosures must be filed on behalf <strong>of</strong> all parties to a civil, agency, bankruptcy or<br />

mandamus case. Corporate defendants in a criminal or post-conviction case and corporate amici<br />

curiae are required to file disclosure statements. Counsel has a continuing duty to update this<br />

information.<br />

No. _______ Caption: __________________________________________________<br />

Pursuant to FRAP 26.1 and Local Rule 26.1,<br />

______________________ who is _______________________, makes the following disclosure:<br />

(name <strong>of</strong> party/amicus) (appellant/appellee/amicus)<br />

1. Is party/amicus a publicly held corporation or other publicly held entity? YES NO<br />

2. Does party/amicus have any parent corporations? YES NO<br />

If yes, identify all parent corporations, including grandparent and great-grandparent<br />

corporations:<br />

3. Is 10% or more <strong>of</strong> the stock <strong>of</strong> a party/amicus owned by a publicly held corporation or<br />

other publicly held entity? YES NO<br />

If yes, identify all such owners:<br />

4. Is there any other publicly held corporation or other publicly held entity that has a direct<br />

financial interest in the outcome <strong>of</strong> the litigation (Local Rule 26.1(b))? YES NO<br />

If yes, identify entity and nature <strong>of</strong> interest:<br />

5. Is party a trade association? (amici curiae do not complete this question) YES NO<br />

If yes, identify any publicly held member whose stock or equity value could be affected<br />

substantially by the outcome <strong>of</strong> the proceeding or whose claims the trade association is<br />

pursuing in a representative capacity, or state that there is no such member:<br />

6. Does this case arise out <strong>of</strong> a bankruptcy proceeding? YES NO<br />

If yes, identify any trustee and the members <strong>of</strong> any creditors’ committee:<br />

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE<br />

**************************<br />

I certify that on _________________ the foregoing document was served on all parties or their<br />

counsel <strong>of</strong> record through the CM/ECF system if they are registered users or, if they are not, by<br />

serving a true and correct copy at the addresses listed below:<br />

_______________________________ ________________________<br />

(signature) (date)

Case: 09-2280 Document: 39 Date Filed: 07/01/2010 Page: 3<br />

TABLE OF CONTENTS<br />

i<br />

Page<br />

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ....................................................................................iv<br />

JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT ..........................................................................1<br />

STATEMENT OF ISSUES .......................................................................................1<br />

STATEMENT OF THE CASE..................................................................................2<br />

STATEMENT OF FACTS ........................................................................................7<br />

I. Overview <strong>of</strong> GSA Contracting Procedures at Issue in This Case.........7<br />

II. IIF Obtained its GSA Contracts Through False Representations .........8<br />

A. IIF and Its Award <strong>of</strong> GSA Contracts ..........................................8<br />

B. During Ubl’s Case in Chief The Evidence Showed that<br />

IIF Knowingly Made Material False Representations to<br />

Obtain Contract Awards .............................................................9<br />

C. IIF Defended the Complaint Based Upon a<br />

Misconstruction <strong>of</strong> the Government Knowledge Defense<br />

and by Having Factual Witnesses Testify as Experts...............14<br />

D. Jury Deliberations and the Verdict ...........................................15<br />

E. IIF’s Post Trial Motion for Attorney Fees Was Granted<br />

Against Ubl in the Amount <strong>of</strong> $501,546...................................15<br />

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ...............................................................................16<br />

ARGUMENT ...........................................................................................................18<br />

STANDARDS OF REVIEW.........................................................................18

Case: 09-2280 Document: 39 Date Filed: 07/01/2010 Page: 4<br />

I. THE TRIAL COURT ERRED IN FAILING TO ENFORCE<br />

THE MAY 6, 2008 SETTLEMENT AGREEMENT FOR<br />

$8,900,000 WITH THE IIF DEFENDANTS .....................................19<br />

II. THE TRIAL COURT ERRED IN PERMITTING IIF TO<br />

PRESENT EVIDENCE AND ARGUE THAT NGB’S<br />

ACCEPTANCE OF UNQUALIFIED LABOR NEGATES<br />

LIABILITY UNDER THE GOVERNMENT KNOWLEDGE<br />

DEFENSE ...........................................................................................23<br />

A. The Trial <strong>Court</strong> Erred in Denying Ubl’s Motion in<br />

Limine........................................................................................23<br />

1. The Requirements in IIF’s Contracts with GSA<br />

Could Not Be Altered by NGB ......................................25<br />

2. The Government’s Knowledge Defense Is<br />

Inapplicable In This Case ...............................................31<br />

B. The Trial <strong>Court</strong>’s Error Was Immensely Prejudicial to<br />

Ubl.............................................................................................35<br />

III. THE TRIAL COURT ABUSED ITS DISCRETION IN<br />

STRIKING UBL’S GSA EXPERT, NEAL FOX...............................37<br />

A. The <strong>Court</strong> Abused its Discretion in Finding Fox Was Not<br />

Qualified and Would Not Provide Helpful Testimony to<br />

the Jury......................................................................................37<br />

1. Standard <strong>of</strong> Review for Excluding An Expert<br />

Witness ...........................................................................39<br />

2. The <strong>Court</strong> Abused Its Discretion in Excluding Mr.<br />

Fox ..................................................................................40<br />

B. The <strong>Court</strong> Abused Its Discretion in Finding Fox Could<br />

Not Testify as to IIF’S New Defenses at Trial and Could<br />

Not Testify as to GSA’s Opinion <strong>of</strong> IIF’S Actions ..................46<br />

ii

Case: 09-2280 Document: 39 Date Filed: 07/01/2010 Page: 5<br />

IV. THE TRIAL COURT ABUSED ITS DISCRETION IN<br />

PERMITTING IIF’S PRIVATE ACCOUNTANT TO<br />

TESTIFY AS TO GSA POLICIES AND PROCEDURES<br />

WHEN HE WAS NEVER IDENTIFIED AS AN EXPERT..............48<br />

V. THE TRIAL COURT EXCLUDED RELEVANT<br />

TESTIMONY FROM TWO FACT WITNESSES ON THE<br />

ERRONEOUS BASIS THAT THE FACT WITNESSES’<br />

TESTIMONY INCLUDED ADDITIONAL INFORMATION<br />

NOT CONTAINED IN THEIR DEPOSITION TESTIMONY .........50<br />

VI. THE TRIAL COURT ERRED IN PERMITTING IIF TO<br />

ELICIT TESTIMONY THAT NGB WAS AWARE OF THE<br />

LAWSUIT AND HAD NOT CANCELLED IIF’S<br />

CONTRACT AS WELL AS INTRODUCING EVIDENCE<br />

AND ARGUMENT THAT THE GOVERNMENT HAD NOT<br />

INTERVENED IN THIS ACTION ....................................................53<br />

VII. THE TRIAL COURT ERRED IN AWARDING IIF<br />

$501,546.00 IN ATTORNEY FEES FOR THE TIME PERIOD<br />

OF MARCH 24, 2009 TO OCTOBER 27, 2009................................55<br />

A. The <strong>Court</strong> Erred In Finding Ubl’s Claims to be “Clearly<br />

Frivolous”..................................................................................55<br />

B. The <strong>Court</strong> Erred In Finding that As <strong>of</strong> March 24, 2009<br />

Ubl Should Have Known That He Had No Reasonable<br />

Chance <strong>of</strong> Success.....................................................................67<br />

C. Defendant’s Fees For the Five Attorneys Billed Were<br />

Unreasonable.............................................................................70<br />

CONCLUSION........................................................................................................72<br />

CERTIFICATE OF COMPLIANCE<br />

CERTIFICATE OF FILING AND SERVICE<br />

iii

CASES<br />

Case: 09-2280 Document: 39 Date Filed: 07/01/2010 Page: 6<br />

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES<br />

iv<br />

Page(s)<br />

American Sys. Consulting, Inc.,<br />

B 294644, 2004 CPD 247 (Dec. 13, 2004).................................................26<br />

Christianburg Garment Co. v. EEOC,<br />

434 U.S. 412 (1978).......................................................................................57<br />

Fiberglass Insulators, Inc. v. Dupuy,<br />

856 F.2d 652 (4 th Cir. 1988) ..........................................................................22<br />

Friendship Heights Assocs. v. Vlastimil Koubek, A.I.A.,<br />

785 F.2d 1154 (4 th Cir. 1986) ............................................................40, 41, 42<br />

Garrett v. Desa Industries, Inc.,<br />

705 F.2d 721 (4 th Cir. 1983) .................................................................. passim<br />

Hensley v. Alcon Laboratories, Inc.,<br />

277 F.3d 535 (4 th Cir. 2002) ..........................................................................22<br />

Houston v. Norton,<br />

215 F.3d 1172 (10 th Cir. 2000) ......................................................................57<br />

Koon v. <strong>United</strong> <strong>States</strong>,<br />

518 U.S. 81 (1996).........................................................................................19<br />

Kopf v. Skyrm,<br />

993 F.2d 374 (4 th Cir. 1993) ..........................................................................40<br />

McDonnell v. Miller Oil Co.,<br />

134 F.3d 638 (4 th Cir. 1988) ..........................................................................19<br />

Melton v. Pasqua,<br />

339 F.3d 222 (4 th Cir. 2003) ..........................................................................18

Case: 09-2280 Document: 39 Date Filed: 07/01/2010 Page: 7<br />

Moore v. Beaufort County,<br />

936 F.2d 159 (4 th Cir. 1991) ..........................................................................22<br />

Perot Systems Government Services, Inc.,<br />

B-402138, 2010 CPD 64, 2010 WL 884032 (Jan. 21, 2010) ...............26, 28<br />

Persinger v. Norfolk & Western Railway Co.,<br />

920 F.2d 1185 (4 th Cir. 1990) ........................................................................45<br />

Pfingston v. Ronan Eng’g Co.,<br />

284 F.3d 999 (9 th Cir. 2002) .................................................................... 57-58<br />

Rafizadeh v. Continental Common, Inc.,<br />

553 F.2d 869 (5 th Cir. 2008) ..........................................................................58<br />

Rowland v. Am. Gen. Fin., Inc.,<br />

340 F.3d 187 (4 th Cir. 2003) ..........................................................................19<br />

Sanford’s Domestic/International Trade,<br />

B-230580, B-230580-2 88-2 CPD 214 (Sept. 6, 1998)..............................64<br />

Science Applications International,<br />

B-401773, 2009 CPD 229 (Nov. 10, 2009).......................................... 26-27<br />

Scott v. Sears, Roebuck & Co.,<br />

789 F.2d 1052 (4 th Cir. 1986) .................................................................. 45-46<br />

Tarheel Specialties, Inc.,<br />

B-298197; B-298197.2, 2006 CPD 140 (July 17, 2006)................26, 29, 30<br />

<strong>United</strong> <strong>States</strong> v. Basham,<br />

561 F.3d 302 (4 th Cir 2009) .....................................................................19, 72<br />

<strong>United</strong> <strong>States</strong> v. Cheek,<br />

94 F.3d 136 (4 th Cir. 1996) ............................................................................18<br />

<strong>United</strong> <strong>States</strong> v. Collins,<br />

415 F.3d 304 (4 th Cir. 2005) ..........................................................................18<br />

v

Case: 09-2280 Document: 39 Date Filed: 07/01/2010 Page: 8<br />

<strong>United</strong> <strong>States</strong> v. Cripps,<br />

460 F. Supp. 969 (E.D. Mich. 1978) .............................................................33<br />

<strong>United</strong> <strong>States</strong> v. Cushman & Wakefield, Inc.,<br />

275 F. Supp. 2d 763 (N.D. Tex. 2002) ..........................................................33<br />

<strong>United</strong> <strong>States</strong> v. Nat’l Wholesalers,<br />

236 F.2d 944 (9th Cir. 1956) .........................................................................33<br />

<strong>United</strong> <strong>States</strong> v. Perkins,<br />

470 F.3d 150 (4 th Cir. 2006) ..........................................................................40<br />

<strong>United</strong> <strong>States</strong> v. Safavian,<br />

528 F.3d 957 (D.C. Cir. 2008).......................................................................49<br />

<strong>United</strong> <strong>States</strong> ex rel. Atkins v. McInteer,<br />

470 F.3d 1350 (11 th Cir. 2006) ......................................................................55<br />

<strong>United</strong> <strong>States</strong> ex rel. Berge v.<br />

Board <strong>of</strong> Trustees <strong>of</strong> the University <strong>of</strong> Alabama,<br />

104 F.3d 1453 (4 th Cir. 1997), cert denied,<br />

522 U.S. 916 (1997).......................................................................................54<br />

<strong>United</strong> <strong>States</strong> ex rel. Butler v. Hughes Helicopters, Inc.,<br />

71 F.3d 321 (9 th Cir. 1995) ............................................................................33<br />

<strong>United</strong> <strong>States</strong> ex rel. El-Amin v. The George Washington Hospital,<br />

533 F. Supp. 2d 12 (D.D.C. 2008).................................................................55<br />

<strong>United</strong> <strong>States</strong> ex rel. Grynberg v. Praxair, Inc.,<br />

389 F.3d 1038 (10 th Cir. 2004) ..........................................................19, 32, 57<br />

<strong>United</strong> <strong>States</strong> ex rel. Gudur v. Deloitte Consulting LLP,<br />

512 F. Supp. 2d 920 (S.D. Tex. 2007)...........................................................32<br />

<strong>United</strong> <strong>States</strong> ex rel. Hagood v. Sonoma County Water Agency,<br />

929 F.2d 1416 (9 th Cir. 1992) ........................................................................32<br />

<strong>United</strong> <strong>States</strong> ex rel. Harrison v. Westinghouse Savannah River Co.,<br />

352 F.3d 908 (4 th Cir. 2003) ..........................................................................31<br />

vi

<strong>United</strong> <strong>States</strong> ex rel. J. Cooper & Assocs. v. Bernard Hodes Group, Inc.,<br />

422 F. Supp. 2d 225 (D.D.C. 2006)...............................................................58<br />

<strong>United</strong> <strong>States</strong> ex rel. Mayman v. Martin Marietta Corp.,<br />

894 F. Supp. 218 (D. Md. 1995)....................................................................33<br />

<strong>United</strong> <strong>States</strong> ex rel. Norman Rille and Neal Roberts v.<br />

EMC Corporation,<br />

No. 1:09-cv-00628-GBL-TRJ .......................................................................28<br />

<strong>United</strong> <strong>States</strong> ex rel. Stone v. Rockwell International Corp.,<br />

282 F.3d 787 (10 th Cir. 2002), rev’d in part on other grounds,<br />

549 U.S. 457 (2007).......................................................................................33<br />

<strong>United</strong> <strong>States</strong> ex rel. Vuyyuru v. Jahdav,<br />

555 F.3d 337 (4 th Cir. 2009) ..........................................................................58<br />

Winter v. Cath-DR/Balti Joint Venture,<br />

497 F.3d 1339 (Fed. Cir. 2007) .....................................................................34<br />

STATUTES<br />

Case: 09-2280 Document: 39 Date Filed: 07/01/2010 Page: 9<br />

10 U.S.C. § 2304......................................................................................................26<br />

18 U.S.C. § 1001......................................................................................................65<br />

28 U.S.C. § 1291........................................................................................................1<br />

28 U.S.C. § 1331........................................................................................................1<br />

31 U.S.C. §§ 3729 et seq........................................................................................1, 3<br />

31 U.S.C. § 3729(a)(1)(A)-(B) ................................................................................34<br />

31 U.S.C. §§ 3729-32 ................................................................................................1<br />

31 U.S.C. § 3732........................................................................................................1<br />

41 U.S.C. § 253........................................................................................................26<br />

vii

RULES<br />

Fed. R. Civ. P. 9(b) ................................................................................................3, 4<br />

Fed. R. Civ. P. 26(e).....................................................................................14, 17, 52<br />

Fed. R. Civ. P. 37(c)(1)............................................................................................48<br />

Fed. R. Civ. P. 50.......................................................................................................6<br />

Fed. R. Evid. 702 .........................................................................................39, 40, 41<br />

REGULATIONS<br />

Case: 09-2280 Document: 39 Date Filed: 07/01/2010 Page: 10<br />

48 C.F.R. § 2.101 ...............................................................................................10, 63<br />

48 C.F.R. § 6.102(d) ................................................................................................26<br />

48 C.F.R. § 8.402(a).................................................................................................25<br />

48 C.F.R. § 8.404(a).................................................................................................26<br />

48 C.F.R. § 15 ......................................................................................................7, 26<br />

48 C.F.R. § 15.402 .....................................................................................................8<br />

48 C.F.R. § 15.403-1..................................................................................................8<br />

48 C.F.R. § 3729(b) .................................................................................................25<br />

48 C.F.R. § 3729(b)(4).............................................................................................67<br />

48 C.F.R. § 3730(d)(4).............................................................................6, 56, 57, 58<br />

viii

Case: 09-2280 Document: 39 Date Filed: 07/01/2010 Page: 11<br />

OTHER AUTHORITIES<br />

Advisory Committee Notes to Federal Rules <strong>of</strong> Civil Procedure 26(e)..................53<br />

John Cibinic, Jr., Ralph C. Nash, Jr. & James F. Nagle,<br />

Administration <strong>of</strong> Government Contracts (4th ed. 2006) ........................................34<br />

Moore’s Federal Practice § 26.131[1] ....................................................................52<br />

ix

JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT<br />

The federal courts have jurisdiction <strong>of</strong> this action under 28 U.S.C. § 1331<br />

and 31 U.S.C. §§ 3729-32 (2000). Venue was proper in the District <strong>Court</strong> for the<br />

Eastern District <strong>of</strong> Virginia (“the court”) under id. § 3732, because at least one<br />

Defendant/Appellee transacted business in the District, and at least one act<br />

proscribed by 31 U.S.C. § 3729 occurred in that District.<br />

This <strong>Court</strong> possesses jurisdiction under 28 U.S.C. § 1291 (2000). The<br />

Orders appealed from were entered on October 27, 2009, April 28, 2010 and<br />

December 4, 2010. Timely notices <strong>of</strong> appeal were filed by Relator on November<br />

9, 2009, January 4, 2010 (Amended Notice) and May 5, 2010 (Second Amended<br />

Notice).<br />

Case: 09-2280 Document: 39 Date Filed: 07/01/2010 Page: 12<br />

STATEMENT OF ISSUES<br />

1. Whether the trial court erred in failing to enforce the IIF Defendants’<br />

May 6, 2008 settlement agreement?<br />

2. Whether the trial court erred in permitting IIF to present evidence and<br />

argue that the National Guard’s acceptance <strong>of</strong> unqualified IIF labor under IIF’s<br />

U.S. General Services Administration contract may negate False Claims Act<br />

liability under the government knowledge defense?<br />

3. Whether the trial court abused its discretion in striking Ubl’s U.S.<br />

General Services Administration expert witness?

Case: 09-2280 Document: 39 Date Filed: 07/01/2010 Page: 13<br />

4. Whether the trial court abused its discretion in permitting IIF’s<br />

accountant to testify as to U.S. General Services Administration policies and labor<br />

categories when he was never identified as an expert witness?<br />

5. Whether the trial court abused its discretion in excluding relevant<br />

testimony from two fact witnesses on the grounds that the anticipated testimony<br />

included information not included in their deposition testimony?<br />

6. Whether the trial court abused its discretion in permitting IIF to elicit<br />

testimony that NGB was aware <strong>of</strong> this lawsuit and had not cancelled IIF’s contracts<br />

as well as introducing evidence and argument that the Government had not taken<br />

legal action against IIF?<br />

7. Whether the trial court abused its discretion in awarding defendants<br />

$501,546 in attorneys’ fees for the time period <strong>of</strong> March 24 to October 27, 2009?<br />

STATEMENT OF THE CASE<br />

As Judge O’Grady noted in his April 28, 2010 Memorandum Opinion,<br />

“[t]his case proceeded down a long and tumultuous procedural path,” 1 culminating<br />

in a seven day jury trial… “where after deliberation, the jury returned a verdict in<br />

Defendants’ favor on all counts.” (J.A. 1983). Unfortunately, the court’s errors in<br />

refusing to enforce an $8.9 million settlement between the parties, followed by the<br />

court’s multiple erroneous trial rulings have prejudiced Appellant Thomas Ubl<br />

1 “J.A. #” designates the joint appendix page.<br />

2

(“Ubl”) and destroyed the core legal mandate supporting the rationale and indeed<br />

entire raison d’etre <strong>of</strong> the U.S. General Services Administration’s (“GSA’s”)<br />

Government-wide contracting program. These serious errors by the court require<br />

correction. This <strong>Court</strong> should vacate the court’s judgment in favor <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Appellees.<br />

Case: 09-2280 Document: 39 Date Filed: 07/01/2010 Page: 14<br />

On June 2, 2006, Ubl, initiated this qui tam action under the False Claims<br />

Act (“FCA”), 31 U.S.C. §§ 3729 et seq., by filing a Complaint, under seal, alleging<br />

that his former employer, IIF Data Solutions, Inc. (“IIF”), and its vice-president,<br />

Charles Patten, Sr. (“Patten”), (collectively “IIF”) fraudulently induced an award<br />

<strong>of</strong> GSA Multiple Award Schedule (“MAS”) contracts, 2 and thereafter submitted<br />

false claims under those MAS contracts. (Dkt. 1). Ubl worked for IIF in 2001-02,<br />

starting soon after IIF received a lucrative GSA Schedule Information Technology<br />

(“IT”) contract and continuing during the time IIF obtained two additional GSA<br />

contracts (MOBIS 3 and Environmental) utilizing the sales and pricing data<br />

supplied to GSA to obtain the IT contract.<br />

The Complaint was unsealed and served on IIF, which moved to dismiss<br />

under Fed. R. Civ. P. 9(b). (Dkt. 16). On March 30, 2007, the motion was granted<br />

2 MAS contracts also are referred to as Federal Supply Schedule (“FSS”) contracts,<br />

an older description. Cases cited herein occasionally refer to FSS contracts.<br />

3<br />

MOBIS stands for Management Organizational & Business Improvement<br />

Services. (J.A. 1371).<br />

3

with leave to amend (Dkt. 30), and Ubl filed an Amended Complaint on April 13,<br />

2007. (J.A. 41-59). IIF’s motion to dismiss under Rule 9(b) was denied by Judge<br />

T.S. Ellis, III, and after discovery, several IIF motions for summary judgment, to<br />

dismiss and to exclude evidence were denied by Judge Liam O’Grady. (Dkt. 45,<br />

187, 234) (J.A. 137). Just prior to the scheduled trial date <strong>of</strong> May 6, 2008, the<br />

court decided several pre-trial motions. Among those germane to this appeal are<br />

IIF’s Daubert Motion to Exclude Neal Fox and G. Thorn McDaniel, III<br />

(respectively, Ubl’s GSA and damages experts), denied on April 29, 2008 (J.A.<br />

138, 315, 348), and Ubl’s Motion to Exclude Evidence Regarding the <strong>United</strong><br />

<strong>States</strong>’ Decision Not to Intervene (J.A. 314a), granted on April 30, 2008. (J.A.<br />

348).<br />

Case: 09-2280 Document: 39 Date Filed: 07/01/2010 Page: 15<br />

On May 6, 2008, when the jury trial was to commence, IIF and Ubl reached<br />

a settlement during mediation before Magistrate Judge Jones, which was<br />

memorialized in a written settlement agreement. Under the settlement, IIF agreed<br />

to pay the <strong>United</strong> <strong>States</strong> $8,900,000, including Ubl’s attorney fees and costs (inter<br />

alia). (J.A.435-437). Settlement agreement paragraph 21 states that the agreement<br />

is void without Government approval, but that “if the Government does not<br />

approve this agreement, the parties shall cooperate in good faith to effectuate<br />

changes to this Agreement that will be satisfactory to the Government.” (J.A.<br />

436). The Department <strong>of</strong> Justice (“DOJ”), whose representative was present in<br />

4

Case: 09-2280 Document: 39 Date Filed: 07/01/2010 Page: 16<br />

chambers during the final construction <strong>of</strong> the agreement, later objected to several<br />

aspects <strong>of</strong> the settlement agreement relating to allocation between the <strong>United</strong> <strong>States</strong><br />

and Ubl <strong>of</strong> the $8.9 million in proceeds.<br />

On March 19, 2009, IIF added Robert Cynkar as counsel. (Dkt. 280).<br />

On April 17, 2009, IIF filed a motion to dismiss for lack <strong>of</strong> subject matter<br />

jurisdiction, which was denied on May 5, 2009. (Dkt. 287). On May 15, 2009, the<br />

<strong>Court</strong> re-scheduled the jury trial for October 19, 2009 (Dkt. 290), although the<br />

Government and Ubl remained in discussions relating to the settlement agreement<br />

with the aid <strong>of</strong> Magistrate Judge Jones. See, e.g., Docket Sheet, June 25, 2009.<br />

Through September <strong>of</strong> 2009, discussions between Ubl and the Government<br />

continued toward resolving DOJ’s objections to the settlement agreement issues.<br />

On September 17, 2009, the DOJ and Ubl reached an agreement in principle. (J.A.<br />

432). Based on the Government’s approval in principle, Ubl filed a motion to<br />

enforce the settlement agreement. (J.A.419-437). Despite the resolution-in-<br />

principle <strong>of</strong> the settlement agreement issues, on October 9, 2009 (ten days before<br />

the trial was scheduled to commence), the court heard argument (J.A. 438-453) and<br />

denied Ubl’s motion to enforce the settlement agreement or take the case <strong>of</strong>f the<br />

docket for further proceedings (Dkt. 309), thereby disregarding and frustrating the<br />

cooperative terms and conditions <strong>of</strong> the settlement.<br />

5

The case proceeded to trial on October 19, 2009. During the seven-day jury<br />

trial, the court limited the testimony <strong>of</strong> several important Ubl witnesses, and<br />

excluded Ubl’s GSA expert, Neal Fox. (J.A. 977-1033). After Ubl presented his<br />

case-in-chief, the court declined to grant IIF’s motion under Fed. R. Civ. P. 50. On<br />

October 27, 2009, the jury returned a verdict for IIF on the Amended Complaint<br />

and for Ubl on IIF’s counterclaim alleging theft <strong>of</strong> trade secrets. (J.A.1649).<br />

Judgment was entered that day. (J.A. 1661).<br />

On November 12, 2009, IIF filed a motion for attorneys’ fees arguing that<br />

Ubl’s case was “clearly frivolous” within the meaning <strong>of</strong> FCA § 3730(d)(4) (Dkt.<br />

341), which was granted as to Ubl on December 4, 2009. (J.A. 1951). On April<br />

28, 2009 the <strong>Court</strong> assessed $501,546.00 in attorneys’ fees against Ubl. (J.A.<br />

2008).<br />

Case: 09-2280 Document: 39 Date Filed: 07/01/2010 Page: 17<br />

On November 9, 2009, Ubl timely filed a Notice <strong>of</strong> Appeal <strong>of</strong> the October<br />

27, 2009 Judgment Order. (J.A. 1674). On January 4 and 6, 2010, an Amended<br />

Notice <strong>of</strong> Appeal was timely filed to the <strong>Court</strong>’s December 4, 2009 Order granting<br />

attorney fees against Ubl. (J.A. 1954). On May 5, 2010, a subsequent Amended<br />

Notice <strong>of</strong> Appeal was timely filed by Ubl to include an appeal <strong>of</strong> the April 28,<br />

2010 award <strong>of</strong> $501,546 in attorney fees against him. (Dkt. 379).<br />

6

STATEMENT OF FACTS<br />

I. Overview <strong>of</strong> GSA Contracting Procedures at Issue in This Case<br />

The GSA’s MAS program provides a simplified mechanism by which U.S.<br />

agencies may acquire commercial services and supplies without the burden <strong>of</strong> full<br />

and open competition for each individual agency order. The GSA awards MAS<br />

contracts for each commercial service or supply. The items and the prices for the<br />

items are established through initial negotiations between the GSA’s warranted<br />

Contracting Officer and the potential MAS contractor; and the negotiated items<br />

and prices are set forth in the resulting GSA MAS contract award.<br />

The MAS contractor then publishes its MAS catalog to the federal agencies,<br />

and those agencies use the MAS catalog to order the approved items, services or<br />

supplies. Significantly, since the prices already have been vetted in connection<br />

with the original MAS contract award, the federal agencies may place orders<br />

without a cost and pricing audit, or the full and open competition otherwise<br />

required by the Truth in Negotiations Act, the Competition in Contracting Act and<br />

Title 48 <strong>of</strong> the Code <strong>of</strong> Federal Regulations, Federal Acquisition Regulation<br />

(“FAR”) Part 15.<br />

Case: 09-2280 Document: 39 Date Filed: 07/01/2010 Page: 18<br />

In the initial negotiations, the would-be MAS contractor must provide the<br />

GSA with either: (1) correct, accurate and complete “cost or pricing data” and<br />

submit to an audit, or (2) if the <strong>of</strong>feror has the requisite commercial sales, its<br />

7

complete commercial sales history for the services or items supplied, including<br />

pricing and discount information, and a commercial price list. In the latter case,<br />

the GSA Contracting Officer uses that information, in lieu <strong>of</strong> more detailed and<br />

cumbersome “cost or pricing data,” to evaluate the reasonableness <strong>of</strong> <strong>of</strong>fered price,<br />

to negotiate a Government discount and to then make an award decision. E.g. FAR<br />

15.402; 15.403-1.<br />

Offerors providing false commercial sales, pricing and discount information<br />

in a proposal to obtain a MAS contract deny the GSA Contracting Officer what she<br />

needs to protect the Government’s interests, i.e., to award MAS contracts to<br />

experienced and responsible contractors at prices tested in the commercial<br />

marketplace which therefore are fair and reasonable; and thereby to meet the GSA<br />

Contracting Officer’s “fiduciary responsibility to the American taxpayer and to<br />

customer agencies to take full advantage <strong>of</strong> the government’s leverage in the<br />

market in order to obtain the best deal for the taxpayer” and to obtain the Most<br />

Favored Customer status for the government by obtaining the <strong>of</strong>feror’s best price.<br />

(J.A. 1368).<br />

Case: 09-2280 Document: 39 Date Filed: 07/01/2010 Page: 19<br />

II. IIF Obtained its GSA Contracts Through False Representations<br />

A. IIF and Its Award <strong>of</strong> GSA Contracts<br />

IIF was established in 1998 by Patten and his wife. At the time, Patten was<br />

in the National Guard. While he was still employed by the Guard, Patten began<br />

8

Case: 09-2280 Document: 39 Date Filed: 07/01/2010 Page: 20<br />

negotiating to obtain National Guard contracting work for IIF from The McVey<br />

Corp., Inc. (“TMCI”). Patten retired from the National Guard in August, 1998, and<br />

subsequently, IIF and TMCI entered into a contract to perform subcontracting<br />

work for Amerind, Inc., a prime contractor performing services for the National<br />

Guard Bureau (“NGB”). IIF’s work for TMCI concluded in May, 1999, and<br />

shortly thereafter, IIF began performing work directly as a subcontractor for<br />

Amerind providing services to NGB.<br />

In August 2000, IIF submitted a proposal to GSA for a MAS contract for IT<br />

services which involved labor categories ranging from program manager to quality<br />

assurance analyst. In November 2000, GSA awarded IIF a MAS contract for six<br />

labor categories as specific prices. In 2001, IIF sought several additions to the<br />

labor categories, and in July 2001, GSA added these to labor categories to IIF’s<br />

MAS IT contract. In 2002, IIF obtained two additional GSA MAS contracts:<br />

MOBIS and Environmental. Virtually all <strong>of</strong> the orders under these three GSA<br />

contracts were placed by NGB, where (as noted) Patten had worked.<br />

B. During Ubl’s Case in Chief The Evidence Showed that IIF<br />

Knowingly Made Material False Representations to Obtain<br />

Contract Awards<br />

In their proposals to the GSA for the MAS contracts, IIF provided false prior<br />

sales and discounting information to induce GSA to award the contract at specific<br />

prices. For example, IIF reported to GSA commercial prices based on negotiated<br />

9

discounts for a 60-hour work week with TMCI, and asked GSA not to take those<br />

lower labor rates into account in determining the MAS contract price (J.A. 1302).<br />

In reality, there were no such discounts, much less negotiated discounts.<br />

IIF also submitted to GSA a “January 2000 commercial price list” <strong>of</strong> the<br />

labor categories IIF supposedly had sold in the open market at the established<br />

catalog or market prices therein (J.A. 1329). In fact, IIF had never previously used<br />

the commercial price list that was presented to the GSA (J.A. 582-589). Indeed,<br />

IIF could not recall selling any <strong>of</strong> the items on the commercial price list at the<br />

prices listed therein (J.A. 583, 587); the price list itself was backdated (J.A. 586-<br />

587); and the price list lacked the statement expressly required by the GSA’s MAS<br />

contract solicitation that warned GSA that the pr<strong>of</strong>fered price list was not actually<br />

used in the marketplace (J.A. 589, 1294 at (c)(1)). Further, IIF reported to GSA<br />

standard discounts <strong>of</strong>f <strong>of</strong> IIF’s so-called commercial sales prices (J.A. 1303), when<br />

in fact there never were previous sales <strong>of</strong> the labor categories at the listed prices<br />

and, necessarily, no standard discounts <strong>of</strong> such non-existent sales prices. (J.A.<br />

1305).<br />

Case: 09-2280 Document: 39 Date Filed: 07/01/2010 Page: 21<br />

Finally, IIF reported to GSA a specific “hourly rate on PO [Purchase Order]”<br />

purportedly issued by Amerind (J.A. 1305) in order to establish that the prices<br />

proposed for each <strong>of</strong> the <strong>of</strong>fered labor categories were “market tested” and<br />

therefore fair and reasonable. (J.A. 61) (citing FAR 2.101). In fact, there were no<br />

10

“hourly rates on PO” for the listed labor categories (or indeed any labor<br />

categories). (J.A.1151-53; 1228-1231; 1305). Instead, the sales to Amerind were<br />

fixed-price, billed monthly. They were not sales <strong>of</strong> labor categories at hourly rates<br />

(much less from a catalog or price list for such labor categories at the hourly rates<br />

listed therein) as IIF told the GSA. (J.A. 1115-53; 1228-1231). The prices IIF<br />

proposed for the <strong>of</strong>fered labor categories were not market-tested. IIF simply made<br />

them up.<br />

Case: 09-2280 Document: 39 Date Filed: 07/01/2010 Page: 22<br />

IIF’s false representations to GSA formed the basis for its award <strong>of</strong> the MAS<br />

IT contract and the labor category prices therein. IIF’s fabricated and backdated<br />

commercial price list – and the fictive pricing data therein -- was one <strong>of</strong> the<br />

explicitly-stated “Bas[e]s for Negotiation and Award.” (J.A. 1332-1333)<br />

[“Commercial Price List effective January 2000”) (“This contract includes the<br />

following . . . Commercial Price List dated January-1-2000”). The listed Amerind<br />

purchase orders and supposed labor category “hour rates” therein were an explicit<br />

“basis” for the GSA’s ultimate “negotiation and award” <strong>of</strong> the IT MAS contract to<br />

IIF. (J.A. 1333). IIF’s subsequent two contracts (the “Environmental” and<br />

“MOBIS” contracts) were obtained on the basis <strong>of</strong> the IT contract award, as the<br />

awards themselves expressly state. (J.A. 1366-69; 1370-1373) (Sections 3,<br />

“Justification,” therein).<br />

11

Case: 09-2280 Document: 39 Date Filed: 07/01/2010 Page: 23<br />

IIF also induced the award <strong>of</strong> the IT contract by falsely claiming in its<br />

August 23, 2000 <strong>of</strong>fer (J.A. 1288) that it had previously “sold” Analyst II labor to<br />

Amerind for $37.80 per labor hour (J.A. 1305), which required a minimum <strong>of</strong> four<br />

years IT experience and a four year bachelor degree. In fact, unbeknownst to<br />

GSA, these “Analyst II” services were performed by Charles Patten, Jr., a recent<br />

high school graduate with virtually no IT experience. (J.A. 878). Likewise, IIF<br />

billed Vince Apesa as an Analyst II, even though his resume and testimony<br />

indicated that he had less than four years <strong>of</strong> IT experience. (J.A. 920).<br />

Once GSA awarded the IT MAS contract to IIF (and later the Environmental<br />

and MOBIS contracts), the company continued its pattern <strong>of</strong> lying about its<br />

unqualified labor, <strong>of</strong> exploiting its GSA contracts by billing GSA for labor<br />

categories at inflated prices and by misclassifying many <strong>of</strong> the labor personnel it<br />

provided into higher-priced categories for which the individuals who performed<br />

the work did not remotely qualify. See June 2001 through June 2002 IIF invoices<br />

billing IT contract services to GSA. (J.A. 1374-75, 1381-82, 1386-87, 1391-92,<br />

1445-46, 1450-51, 1459-60, 1477-78, 1151-1512). Specifically, IIF consistently<br />

billed for work by individuals who lacked the education or experience to qualify<br />

for the labor categories at which they were (over) billed and even billed Kim<br />

Trimble for IT services for three-quarters <strong>of</strong> her time when she was not performing<br />

12

any IT related services for NGB. 4 As one <strong>of</strong> many examples, IIF continued to<br />

report Mr. Patten’s son, a recent high school graduate, with no more than five<br />

months <strong>of</strong> IT experience and no bachelor’s degree as an Analyst II. (J.A. 593-597;<br />

1317).<br />

At trial, Ubl introduced the testimony <strong>of</strong> several GSA Contracting Officers<br />

(“COs”), including the CO who awarded the IT contract, that false commercial<br />

pricing information contained in an <strong>of</strong>fer was capable <strong>of</strong> affecting their award<br />

decision, and that if such information were discovered, a recommendation <strong>of</strong> no<br />

award would likely be issued. (J.A. 506-509). In other words, the fabricated and<br />

backdated commercial price list and other false sales and pricing information were<br />

material.<br />

Case: 09-2280 Document: 39 Date Filed: 07/01/2010 Page: 24<br />

Under its IT, Environmental and MOBIS contracts, IIF submitted to GSA a<br />

total <strong>of</strong> at least 2,100 invoices claiming over $74 million. The <strong>United</strong> <strong>States</strong> paid<br />

these invoices in full. (E.g., J.A. 1374-75, 1380-81, 1386-87, 1391-92, 1397-98,<br />

1445-46, 1450-51, 1459-60, 1477-78, 1511-1512). Ubl’s damages expert, Thorne<br />

McDaniel, who did not testify due to the court’s exclusion <strong>of</strong> a predicate expert<br />

witness, Fox (see Argument III, infra at n. 11), estimated in his report that IIF’s<br />

4 See testimony <strong>of</strong> Charles Patten, Sr. (J.A. 593-598); Charles Patten Jr, (J.A. 878-<br />

881);Vince Apesa (J.A. 920); Kim Trimble, (J.A. 749, 783-800) and other<br />

documentary evidence (e.g. Apesa resume, J.A.1282-87).<br />

13

Case: 09-2280 Document: 39 Date Filed: 07/01/2010 Page: 25<br />

actual overcharges to the government for unqualified labor or improperly awarded<br />

task orders totaled over $18 million. (J.A. 225).<br />

Besides excluding Ubl’s experts, the court also prevented several fact<br />

witnesses from giving critical testimony as to IIF’s fraudulent activities, on the<br />

grounds that Ubl violated Fed. R. Civ. P. 26(e) by not informing IIF that the<br />

witnesses’ anticipated testimony would include material not disclosed during their<br />

depositions, which Ubl had just learned. See Argument V, infra.<br />

C. IIF Defended the Complaint Based Upon a Misconstruction <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Government Knowledge Defense and by Having Factual<br />

Witnesses Testify as Experts<br />

IIF defended Ubl’s Complaint in significant part by arguing that regardless<br />

<strong>of</strong> any false statements to the GSA in obtaining the MAS contracts or in providing<br />

unqualified personnel to fulfill the contracts, the ordering agency, NGB, was<br />

permitted to ignore the requirements <strong>of</strong> the GSA MAS contract and hire personnel<br />

at labor categories and rates for which the person lacked either the education or<br />

experience stated in the GSA MAS contracts (as long as the ordering agency was<br />

happy with the work). Ubl explained to the court that IIF’s argument was clearly<br />

wrong as a matter <strong>of</strong> fact and as a matter <strong>of</strong> law. However, the trial court rejected<br />

Ubl’s objections. (J.A.1026-1028). See Argument II, infra.<br />

Furthermore, during IIF’s case, over Ubl’s objection, the court permitted IIF<br />

to elicit expert testimony from a factual witness, accountant Robert Taylor, to the<br />

14

Case: 09-2280 Document: 39 Date Filed: 07/01/2010 Page: 26<br />

effect that a GSA MAS contractor may provide and bill labor even if it does not<br />

satisfy the definition for the MAS contract labor category and price under which<br />

such labor is billed. (J.A.1059). Moreover, Taylor also was permitted to testify<br />

that the “government” for purposes <strong>of</strong> the administration <strong>of</strong> GSA MAS contracts is<br />

the ordering agency (here, NGB) and not the GSA. (J.A. 1080).<br />

D. Jury Deliberations and the Verdict<br />

After approximately seven hours, the jury returned a verdict denying Ubl’s<br />

claims and also denying IIF’s counterclaim. Judgment was entered that day,<br />

October 27, 2009. (J.A. 1661).<br />

E. IIF’s Post Trial Motion for Attorney Fees Was Granted Against<br />

Ubl in the Amount <strong>of</strong> $501,546<br />

After trial, IIF’s motion for attorney fees was granted by the court on<br />

December 4, 2009, and on April 28, 2010, the court issued a Judgment Order and<br />

Memorandum Opinion awarding attorney fees against Ubl in the amount <strong>of</strong><br />

$501,546, and setting forth what it considered to be “the most prevalent examples<br />

<strong>of</strong> the frivolous nature <strong>of</strong> Ubl’s case.” (J.A. 1987-1999). In part, the court relied<br />

upon the notion that it was NGB which “had the responsibility for determining<br />

whether a particular employee met the relevant qualifications” and hence there was<br />

no basis for alleging that IIF’s billing <strong>of</strong> personnel who failed to satisfy the<br />

definitions <strong>of</strong> the labor categories and prices at which they were billed rose to the<br />

level <strong>of</strong> fraud. Similarly, the court found that certain misrepresentations were a<br />

15

“hyper-technical” construction <strong>of</strong> whether IIF listed rates were “on” purchase<br />

orders, that IIF’s backdated and previously unused commercial pricelist was an<br />

oversight, and that other erroneous pricing information was mere “technical” error.<br />

(J.A. 1987-1999).<br />

Case: 09-2280 Document: 39 Date Filed: 07/01/2010 Page: 27<br />

Accordingly, despite the court’s denial <strong>of</strong> IIF’s motion for summary<br />

judgment, despite the fact that IIF entered into a settlement agreement with Ubl for<br />

$8.900,000 on the day the first trial was scheduled to commence, and despite the<br />

fact that Ubl repeatedly demonstrated during the trial that IIF had submitted false<br />

information in order to obtain its MAS contracts, the court concluded that Ubl’s<br />

claims were “clearly frivolous” and had no reasonable chance <strong>of</strong> success. (J.A.<br />

1984-1989). In this appeal, Ubl challenges the court’s conclusions in this regard<br />

and its award <strong>of</strong> $501,546 in attorney fees. See Argument VIII, infra.<br />

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT<br />

In this qui tam action, the trial court initially erred in not enforcing an $8.9<br />

million settlement agreement after the Government and Ubl resolved their<br />

differences and the Government was prepared to obtain the proper authorized<br />

signatures. (Issue 1).<br />

Then, at trial the court made numerous erroneous rulings that were highly<br />

prejudicial to the Relator’s case and led to a defense verdict. First, the court<br />

allowed IIF to misapply the government knowledge defense by arguing that the<br />

16

National Guard’s purported knowledge <strong>of</strong> IIF’s fraudulent conduct absolved IIF<br />

from liability even though the contracts at issue were with the GSA and<br />

administered by the GSA and by law, the National Guard could not change the<br />

contracts or ratify IIF’s fraud. (Issue 2). In addition, the court excluded Ubl’s<br />

GSA expert (the former GSA Assistant Commissioner <strong>of</strong> Acquisitions, the third<br />

ranking position at GSA and who oversaw GSA’s MAS program) from testifying<br />

based upon the erroneous conclusion that his testimony would not be helpful to the<br />

jury (issue 3), even though the court then (erroneously) allowed IIF’s private<br />

accountant, who was not designated as an expert, to provide his opinions on some<br />

<strong>of</strong> the same issues regarding IT qualifications, GSA contract requirements and<br />

GSA policy. (Issue 4). In addition to excluding the Relator’s expert, the court also<br />

erroneously excluded important testimony from two fact witnesses under a<br />

misapplication <strong>of</strong> Rule 26(e) because Relator did not inform the defense that the<br />

fact witnesses’ anticipated testimony differed from their deposition testimony<br />

(which Relator had just learned). (Issue 5). The last trial error before the <strong>Court</strong> is<br />

that the trial court erroneously permitted the defense to elicit testimony and argue<br />

that NGB was aware <strong>of</strong> the lawsuit and had not cancelled IIF’s contracts, as well as<br />

introducing evidence and argument that the Government had not instituted legal<br />

proceedings against IIF, both in contravention <strong>of</strong> law and an earlier court pre-trial<br />

order. (Issue 6).<br />

Case: 09-2280 Document: 39 Date Filed: 07/01/2010 Page: 28<br />

17

After trial, the trial court abused its discretion by awarding defendants’ over<br />

$500,000 in attorney fees based upon the clearly erroneous conclusion that the<br />

Relator’s should have known that he could not have prevailed in this case and that<br />

his claims were clearly frivolous. (Issue 7).<br />

Due to these errors, Ubl asks that the judgments <strong>of</strong> the court be vacated and<br />

the case remanded for enforcement <strong>of</strong> the settlement agreement or a new trial.<br />

STANDARDS OF REVIEW<br />

ARGUMENT<br />

Issue: 1: Appellate courts review a court’s finding as to the validity <strong>of</strong> a<br />

settlement agreement de novo. Melton v. Pasqua, 339 F.3d 222 (4 th Cir. 2003).<br />

Issue 2: Whether the court erred in permitting IIF to present evidence and<br />

argue that NGB’s acceptance <strong>of</strong> unqualified labor may negates False Claims Act<br />

liability under the “government knowledge” defense is reviewed de novo because<br />

the issue regarding the propriety <strong>of</strong> the argument and defense is a legal issue. See<br />

<strong>United</strong> <strong>States</strong> v. Collins, 415 F.3d 304 (4 th Cir. 2005) (as this issue raises a question<br />

<strong>of</strong> law, the appropriate standard <strong>of</strong> review is de novo. <strong>United</strong> <strong>States</strong> v. Cheek, 94<br />

F.3d 136, 140 (4 th Cir. 1996)).<br />

Issue 3: Appellate courts review a court’s exclusion <strong>of</strong> an expert witness for<br />

abuse <strong>of</strong> discretion. Garrett v. Desa Industries, Inc., 705 F.2d 721, 724 (4 th Cir.<br />

1983).<br />

Case: 09-2280 Document: 39 Date Filed: 07/01/2010 Page: 29<br />

18

Case: 09-2280 Document: 39 Date Filed: 07/01/2010 Page: 30<br />

Issues 4 - 6: Appellate courts review a district court’s evidentiary rulings for<br />

abuse <strong>of</strong> discretion. Rowland v. Am. Gen. Fin., Inc., 340 F.3d 187, 194 (4 th Cir.<br />

2003). However, a district court by definition abuses its discretion when it makes<br />

an error <strong>of</strong> law. McDonnell v. Miller Oil Co., 134 F.3d 638, 640 (4 th Cir. 1988),<br />

citing Koon v. <strong>United</strong> <strong>States</strong>, 518 U.S. 81 (1996).<br />

Issue 7: Appellate courts review a district court’s decision to award<br />

attorney fees under an abuse <strong>of</strong> discretion standard, McDonnell v. Miller Oil Co.,<br />

134 F.3d 638, 640 (4 th Cir. 1988); however, a “clearly frivolous” finding is a<br />

difficult standard and rarely met. <strong>United</strong> <strong>States</strong> ex rel. Grynberg v. Praxair, Inc.,<br />

389 F.3d 1038, 1058 (10 th Cir. 2004).<br />

All issues: The cumulative error doctrine requires a reversal when two or<br />

more individually harmless errors prejudice a party to the same extent as a single<br />

reversible error and deny a party a fair trial. <strong>United</strong> <strong>States</strong> v. Basham, 561 F.3d<br />

302, 330 (4 th Cir 2009).<br />

I. THE TRIAL COURT ERRED IN FAILING TO ENFORCE THE<br />

MAY 6, 2008 SETTLEMENT AGREEMENT FOR $8,900,000 WITH<br />

THE IIF DEFENDANTS<br />

On May 6, 2008, Ubl and IIF and Charles Patten Sr. executed a written<br />

Settlement Agreement in the Chambers <strong>of</strong> Magistrate Judge Jones. (J.A. 435-37).<br />

Under the Settlement Agreement, IIF and Patten were required to pay $8.9 million<br />

“inclusive <strong>of</strong> all damages, costs and fees.” (J.A. 435 1).<br />

19

Case: 09-2280 Document: 39 Date Filed: 07/01/2010 Page: 31<br />

The Settlement Agreement also addressed the role <strong>of</strong> the <strong>United</strong> <strong>States</strong>, as<br />

the real party-in-interest in this FCA action, in the action. Namely, it provided that<br />

“[i]f the Government has not approved this Agreement by June 7, 2008, all<br />

payments due under this Agreement shall be held in escrow pending Government<br />

approval or disapproval.” (J.A. 436 20). In anticipation <strong>of</strong> the possibility that the<br />

Government might require modifications to the Settlement Agreement, Ubl and the<br />

Defendants further agreed that the Settlement Agreement is “void without<br />

Government approval. If the Government does not approve this Agreement, the<br />

parties shall cooperate in good faith to effectuate changes to this Agreement that<br />

will be satisfactory to the Government.” (J.A. 436 21).<br />

As Ubl and Defendants contemplated in drafting and executing their<br />

Settlement Agreement, the Government did object to a number <strong>of</strong> the terms therein<br />

relating principally to the allocation <strong>of</strong> proceeds between Ubl and the Government.<br />

After a lengthy period <strong>of</strong> negotiations, Ubl and the Government resolved their<br />

disputes, and Government counsel authorized Ubl’s counsel to represent to the<br />

court in Relator’s Motion to Enforce Settlement and Enter Judgment Pursuant to<br />

Such Settlement (J.A. 419-434) that:<br />

Relator’s counsel and Government trial attorneys have resolved in<br />

principle between them the issues <strong>of</strong> the total Settlement Amount<br />

specified in the May 6, 2008 Agreement (“Settlement Amount”), the<br />

allocation <strong>of</strong> the Settlement Amount between the <strong>United</strong> <strong>States</strong>,<br />

Relator, and Relator’s Counsel, and the terms specified in the May 6,<br />

2008 Agreement with respect to the upfront payment and payout<br />

20

Case: 09-2280 Document: 39 Date Filed: 07/01/2010 Page: 32<br />

terms. Government trial attorneys are prepared to recommend to<br />

<strong>of</strong>ficials with authority within the <strong>United</strong> <strong>States</strong> Department <strong>of</strong> Justice<br />

and the relevant agencies approval under such terms, should the <strong>Court</strong><br />

grant enforcement <strong>of</strong> the May 6, 2008 Agreement between Relator<br />

and Defendants.<br />

(J.A. 432-433). Hence, as <strong>of</strong> September 25, 2009, Ubl and the Government had<br />

resolved their disagreements and the Settlement Agreement term that requires<br />

Government approval was being satisfied.<br />

Nevertheless, on October 9, 2009, after a hearing, the <strong>Court</strong> not only denied<br />

Relator’s Motion to Enforce Settlement because the Government had not yet<br />

signed the agreement, but also refused to grant the Government a period <strong>of</strong> time to<br />

complete its internal administrative process for signature. The <strong>Court</strong> stated that:<br />

the continued negotiations have resulted in material changes to the<br />

initial agreement to agree that was entered into by two <strong>of</strong> the three<br />

parties. And the third party is missing from the consent. And as a<br />

result, there has never been a binding, enforceable contract entered<br />

into.<br />

(J.A. 449-450). The supposed “material changes” were not identified -- and indeed<br />

there were no material changes that could constitute a legal excuse to relieve IIF<br />

and Patten from their obligations under their executed Settlement Agreement.<br />

Furthermore, as the Motion to Enforce explicitly stated, the supposedly “missing”<br />

party (i.e., the Government) had just indicated that it was prepared to approve the<br />

Settlement Agreement.<br />

21

The court has the inherent authority, arising from its equitable power, to<br />

enforce the Settlement Agreement. Hensley v. Alcon Laboratories, Inc., 277 F.3d<br />

535, 540 (4 th Cir. 2002). “In deciding whether a settlement agreement has been<br />

reached, the <strong>Court</strong> looks to the objectively manifested intentions <strong>of</strong> the parties.”<br />

Moore v. Beaufort County, 936 F.2d 159, 162 (4 th Cir. 1991). The courts have<br />

noted that public policy favors settlements, and therefore construe settlements in<br />

favor <strong>of</strong> enforceability. Fiberglass Insulators, Inc. v. Dupuy, 856 F.2d 652, 654<br />

(4 th Cir. 1988).<br />

Here, Ubl and IIF and Patten had a meeting <strong>of</strong> the minds on May 6, 2008<br />

and objectively manifested their intentions <strong>of</strong> entering into the Settlement<br />

Agreement which they signed in the Chambers <strong>of</strong> a Federal Magistrate Judge. The<br />

parties expressly contemplated the need for Government approval and the<br />

concomitant possibility that the Government may require modifications.<br />

Accordingly, they committed themselves to “cooperate in good faith to effectuate<br />

changes to this Agreement that will be satisfactory to the Government.” (J.A.<br />

436). Yet precisely when the Government indicated that its objections to the<br />

proceeds allocation issues had been satisfied and that it was prepared to<br />

recommend approval <strong>of</strong> the Settlement Agreement, the court ruled it to be<br />

unenforceable.<br />

Case: 09-2280 Document: 39 Date Filed: 07/01/2010 Page: 33<br />

22

Case: 09-2280 Document: 39 Date Filed: 07/01/2010 Page: 34<br />

In effect, the court’s decision placed Ubl in a catch-22 situation. On the one<br />

hand, the Government had resolved in principle all issues with Ubl and simply<br />

wished the court to put its blessing on the May 6, 2008 settlement agreement by<br />

finding it to be enforceable before the Government went through the cumbersome<br />

process <strong>of</strong> obtaining the proper sign <strong>of</strong>fs from the authorized DOJ <strong>of</strong>ficials. On the<br />

other hand, the court ruled that the settlement agreement was not enforceable until<br />

the Government had <strong>of</strong>ficially signed <strong>of</strong>f on the May 6 settlement agreement. The<br />

court’s decision was clearly erroneous. At a minimum, the court should have taken<br />

the case <strong>of</strong>f the active docket, as Ubl suggested in the Motion to Enforce (J.A.<br />

433), and set a date certain for the final agreement to be implemented.<br />

II. THE TRIAL COURT ERRED IN PERMITTING IIF TO PRESENT<br />

EVIDENCE AND ARGUE THAT NGB’S ACCEPTANCE OF<br />

UNQUALIFIED LABOR NEGATES LIABILITY UNDER THE<br />

GOVERNMENT KNOWLEDGE DEFENSE<br />

A. The Trial <strong>Court</strong> Erred in Denying Ubl’s Motion in Limine<br />

During the trial in the instant matter, it became clear that IIF intended to<br />

present evidence and argument that it submitted no false claims to GSA because<br />

the ordering agency, NGB, approved the IIF personnel and was satisfied with their<br />

work. Because this contention is not a valid defense to an FCA claim, Ubl filed a<br />

“Motion in Limine to Preclude Admission <strong>of</strong> Evidence That the National Guard<br />

Bureau Was Entitled to Vary the Terms <strong>of</strong> Defendants’ Federal Supply Schedule<br />

Contracts.” (J.A. 1529-1536). In response, IIF argued that Ubl was trying to “turn<br />

23

Case: 09-2280 Document: 39 Date Filed: 07/01/2010 Page: 35<br />

this fraud case into a breach <strong>of</strong> contract action.” (J.A. 1026). IIF relied on the<br />

government knowledge defense, arguing that it was entitled to introduce “evidence<br />

<strong>of</strong> the [National] Guard’s knowledge <strong>of</strong> what IIF was doing” because “it is well<br />

established that the government’s full knowledge <strong>of</strong> the material facts underlying<br />

any representations implicit in a contractor’s conduct negates any knowledge that<br />

the contractor had regarding the truth or falsity <strong>of</strong> those representations.”<br />

(J.A.1026). Ubl in turn pointed out that the government knowledge defense was<br />

inapplicable because “the knowledge <strong>of</strong> the National Guard has no bearing on the<br />

knowledge and the consent <strong>of</strong> GSA, who was administering the program and who<br />

made the finding <strong>of</strong> fair and reasonable pricing.” (J.A. 1027-28).<br />

Despite the clear legal mandates <strong>of</strong> GSA MAS contracting, the court<br />

erroneously denied Ubl’s Motion in Limine and accepted IIF’s government<br />

knowledge defense because it found “when you are dealing with fraud such as this,<br />

certainly it is relevant what occurred between the National Guard and IIF Solutions<br />

in fulfilling the terms <strong>of</strong> the contract.” (J.A. 1028). Later, in its April 28, 2010<br />

Memorandum Order, the court explained: “it appeared that it was NGB which had<br />

the responsibility for determining whether a particular employee met the relevant<br />

qualifications.” (J.A. 1987).<br />

24

Case: 09-2280 Document: 39 Date Filed: 07/01/2010 Page: 36<br />

The court’s misapplication <strong>of</strong> the government knowledge defense premised<br />

upon a severe and serious misapprehension <strong>of</strong> GSA contracting was perhaps its<br />

most fundamental error in the trial. The court permitted testimony and argument<br />

that NGB’s alleged acceptance <strong>of</strong> IIF’s unqualified labor personnel negated IIF’s<br />

fraudulent intent, i.e., whether IIF submitted false statements to the government<br />

“knowingly” as the FCA defines that term. See FCA § 3729(b). As set forth<br />

below, IIF’s three MAS contracts were with GSA, not NGB. (J.A. 1288, 1366,<br />

1370). That NGB may have been “happy” with the work performed by IIF cannot<br />

nullify the fact that IIF fraudulently obtained these three GSA contracts and then<br />

used them to overbill GSA by millions <strong>of</strong> dollars.<br />

1. The Requirements in IIF’s Contracts with GSA Could Not<br />

Be Altered by NGB<br />

The GSA’s MAS program provides federal agencies with a “simplified<br />

process for obtaining commercial supplies and services at prices associated with<br />

volume buying.” FAR 8.402(a). Under the GSA’s MAS program, the GSA fully<br />

vets and negotiates the proposed MAS contractor’s items and prices prior to the<br />

MAS contract award. Once the GSA Contracting Officer approves the items and<br />

negotiates a reasonable price, the items and negotiated prices are fixed in an MAS<br />

25

Case: 09-2280 Document: 39 Date Filed: 07/01/2010 Page: 37<br />

contract and may not be varied. 5 See Competition in Contracting Act, 10 U.S.C. §<br />

2304; 41 U.S.C. § 253; see also 48 C.F.R. § 8.404(a).<br />

An ordering agency such as NGB has no legal authority to vary the terms <strong>of</strong><br />

GSA’s MAS contracts. If a MAS contractor or ordering agency deviates from the<br />

GSA vetted and negotiated items and prices in the vendor’s MAS contract, the<br />

above carefully crafted and heavily regulated framework for ensuring that the<br />

Government receives a fair and reasonable price is destroyed. “When a concern<br />

arises that a vendor is <strong>of</strong>fering services outside the scope <strong>of</strong> its MAS contract, the<br />

relevant inquiry is not whether the vendor is willing to provide the services that the<br />

agency is seeking, but whether the services or positions <strong>of</strong>fered are actually<br />

included on the vendor’s MAS contract, as reasonably interpreted.” Tarheel<br />

Specialties, Inc., B-298197; B-298197.2, 2006 CPD 140 (July 17, 2006)<br />

(emphasis added); American Sys. Consulting, Inc., B 294644, 2004 CPD 247<br />

(Dec. 13, 2004); see also Science Applications International, B-401773, 2009 CPD<br />

5 Given the GSA’s vetting and negotiation <strong>of</strong> the terms and prices in the GSA<br />

MAS contracts they award, agency orders under those MAS contracts are<br />

considered to satisfy the requirements <strong>of</strong> full and open competition, FAR 6.102(d)<br />

(3), and are not subject to FAR Part 15, which prescribes competitive procedures<br />

for most negotiated contracts. FAR 8.404(a). The MAS contractor’s catalog with<br />

the approved items and prices may be used by agencies throughout the<br />

Government and those “[a]gencies are not required to conduct competitive<br />

acquisitions when making purchases under the FGSS . . . .” REEP, Inc., B-<br />

290665, 2002 CPD 158. See also, Perot Systems Gov’t Serv’s., B-402138, 2010<br />

CPD 64.<br />

26

229 (Nov. 10, 2009) at 1 (under an MAS acquisition, all items ordered must be<br />

included on the vendor’s schedule contract).<br />

As the U.S. Government Accountability Office (“GAO”) stated in a recent<br />

report to Congress:<br />

Where an agency announces its intention to order from an existing<br />

GSA contractor, all items ordered are required to be within the scope<br />

<strong>of</strong> the vendors’ contracts [citing Tarheel Specialties, Inc., B-298197,<br />

298197.2, 2006 CPD 140 (July 17, 2006)]. Orders issued outside<br />

the scope <strong>of</strong> the underlying GSA contract do not satisfy legal<br />

requirements under the Competition in Contracting Act for<br />

competing the award <strong>of</strong> government contracts and limit the<br />

government’s ability to know if it is paying a fair and reasonable<br />

price.<br />

(J.A. 1623) [GAO Report 08-360, Army Case Study Delineates Concerns with Use<br />

<strong>of</strong> Contractors as Contract Specialists (March 2008) at 24] [emphasis added]. “[I]t<br />

is the responsibility <strong>of</strong> the ordering activity to follow ordering procedures and stay<br />

within scope. It is also the responsibility <strong>of</strong> the contractor to follow Terms &<br />

Conditions <strong>of</strong> its contract.” (J.A. 1646).<br />

Consistent with these long-standing and core requirements <strong>of</strong> the GSA’s<br />

MAS contracting program, the MAS contracts at issue in this case explicitly state<br />

that:<br />

The Contractor [IIF] shall only tender for acceptance those items that<br />

conform to the requirements <strong>of</strong> this contract.<br />

(J.A. 1287, 1367, 1372) [emphasis added]. IIF’s IT MAS contract further states<br />

that:<br />

Case: 09-2280 Document: 39 Date Filed: 07/01/2010 Page: 38<br />

27

Case: 09-2280 Document: 39 Date Filed: 07/01/2010 Page: 39<br />

All delivery orders or task orders are subject to the terms and<br />

conditions <strong>of</strong> this contract. In the event <strong>of</strong> conflict between a<br />

delivery order or task order and this contract, the contract shall<br />

control.<br />

(J.A. 1290 [emphasis added]). 6<br />

In sum, GSA MAS contractors and ordering agencies, such as NGB,<br />

definitively may not vary the terms <strong>of</strong> their MAS contract, and IIF was not free to<br />

charge personnel under labor categories and at prices for which the personnel did<br />

not qualify. Decisions <strong>of</strong> the GAO confirm this clear rule. For example in Perot<br />

Systems Government Services, Inc., B-402138, 2010 CPD 64, 2010 WL 884032<br />

(Jan. 21, 2010), the ordering agency (the Veterans Administration) solicited <strong>of</strong>fers<br />

for an order for IT labor to be acquired under an IT MAS contract. When GSA<br />

MAS contractor Perot proposed IT labor category rates that varied from the rates in<br />

its GSA MAS IT contract, the GAO ruled that Perot’s bid for the Veteran’s<br />

Administration order properly was rejected, because:<br />

Perot quoted prices that were not on its current MAS contract and<br />

thus were neither published nor determined to be fair and<br />

reasonable by GSA. This being the case, Perot’s quotation was<br />

inconsistent with the terms and conditions <strong>of</strong> the RFQ [Request for<br />

Quotation] and MAS regulations, and therefore unacceptable. Thus,<br />

GSA properly eliminated it from consideration.<br />

Id. at *3 (emphasis added).<br />

6 The <strong>United</strong> <strong>States</strong> reiterated this core element <strong>of</strong> the GSA’s MAS program in<br />

<strong>United</strong> <strong>States</strong> ex rel. Norman Rille and Neal Roberts v. EMC Corporation, No.<br />

1:09-cv-00628-GBL-TRJ, U.S. First Am. Compl. in Intervention 17. (J.A.<br />

1541).<br />

28

Similarly in Tarheel (see supra), the U.S. Department <strong>of</strong> Homeland Security<br />

solicited an order under GSA MAS contracts for labor categories. Consistent with<br />

the mandates <strong>of</strong> the GSA’s MAS program, the agency’s solicitation advised MAS<br />

contractors that:<br />

id. at *2.<br />

Case: 09-2280 Document: 39 Date Filed: 07/01/2010 Page: 40<br />

the [<strong>of</strong>feror’s proposal] must identify each category <strong>of</strong> labor proposed<br />

for performance mapped to the applicable GSA Schedule labor<br />

category, provide the GSA Schedule price, show the proposed<br />

discounts for the rate, and the rate proposed for the particular labor<br />

category inclusive <strong>of</strong> the discount.<br />

When Tarheel protested the award on the grounds that awardee’s, USIS,<br />

GSA MAS contract did not contain all <strong>of</strong> the labor categories required by the<br />

agency’s order solicitation, the GAO reiterated that:<br />

Where an agency announces its intention to order from an existing<br />

GSA MAS contractor, it means that the agency intends to order all<br />

items using GSA MAS procedures and that all items are required to<br />

be within the scope <strong>of</strong> the vendor’s MAS contract. See Armed<br />

Forces Merchandise Outlet, Inc., B-294281, Oct. 12, 2004, 2004 CPD<br />

218 at 4. Non–MAS products and services may not be purchased<br />

using MAS procedures; instead, their purchase requires compliance<br />

with the applicable procurement laws and regulations, including those<br />

requiring the use <strong>of</strong> competitive procedures. OMNIPLEX World<br />

Servs. Corp., B-291105, Nov. 6, 2002, 2002 CPD 199 at 4-5.<br />

Tarheel, 2006 CPD 140 at *3 (emphasis added).<br />

29

Case: 09-2280 Document: 39 Date Filed: 07/01/2010 Page: 41<br />

After examining labor categories in both the Tarheel and USIS GSA MAS<br />

contracts, the GAO found that neither contract contained the labor categories<br />

solicited by the agency. With regard to Tarheel, the GAO noted:<br />

Tarheel’s MAS contract is for guard services and the labor categories<br />

that it proposed in response to this RFP were not listed in or mapped<br />

to the labor categories listed in Tarheel’s MAS contract. Thus, the<br />

agency properly determined that Tarheel’s proposal was<br />

unacceptable under this RFP, since the RFP required the labor<br />

categories to be on an applicable MAS contract.<br />

Id. (emphasis added). In addition, the GAO found that “USIS’s proposal should<br />

have been regarded as unacceptable as well because USIS’s MAS contract also<br />

did not contain all <strong>of</strong> the labor categories that were required to perform the RFP<br />

requirements.” Id. (emphasis added). The “experience,” “education” and “job<br />

function” requirements <strong>of</strong> USIS’s MAS contract labor categories failed to satisfy<br />

the experience, education and job function requirements in the agency’s order<br />

solicitation. Id. at *5-7. Consequently, GAO held that “it was not proper for the<br />