Slull reacquisition after acquired brain injury - villa martelli disability ...

Slull reacquisition after acquired brain injury - villa martelli disability ...

Slull reacquisition after acquired brain injury - villa martelli disability ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

NeuroRehabilitation 23 (2008) 1 15-126<br />

10s Press<br />

<strong>Slull</strong> <strong>reacquisition</strong> <strong>after</strong> <strong>acquired</strong> <strong>brain</strong> <strong>injury</strong>:<br />

A holistic habit retraining model of<br />

neurorehabilitation<br />

Michael F. ~artelli"~~~~~*, Keith ~icholson~ and Nathan D. ~ asler"~~~~~~~g<br />

aTree of Life Services, Inc., Glen Allen, VA, USA<br />

b~epartments of Psychology and Psychiatry, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA, USA<br />

CDepartment of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA, USA<br />

d~omprehensive Pain Program, The Toronto Western Hospital, Toronto, Ont., Canada<br />

Concussion Care Centre of Virginia, Ltd.<br />

f~epartment of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA, USA<br />

Wortheast Center for Special Care, Lake Katrine, NI: USA<br />

Abstract. Persistent cognitive, emotional and behavioral dysfunction following <strong>brain</strong> <strong>injury</strong> present formidable challenges in<br />

the area of neurorehabilitation. This paper reviews a model and practical methodology for community based neurorehabilitation<br />

based upon:<br />

1. Evidence from the "automatic learning" and "errorless learning" literature for skills relearning <strong>after</strong> <strong>brain</strong> <strong>injury</strong>;<br />

2. A widely applicable task analytic approach to designing relevant skills retraining protocols;<br />

3. Analysis of organic, reactive, developmental, and characterological obstacles to strategy utilization and relearning, and<br />

generation of effective therapeutic interventions; and<br />

4. Procedures for (a) promoting rehabilitative strategy use adapted to acute and chronic neurologic losses, (b) an individual's<br />

inherent reinforcement preferences and coping style, (c) reliant on naturalistic reinforcers which highlight relationships to<br />

functional goals, utilize social networks, and (d) employ a simple and appealing cognitive attitudinal system and set of<br />

procedures.<br />

This Holistic Habit Retraining Model and methodology integrates core psychotherapeutic and learning principles as rehabilitation<br />

process ingredients necessary for optimal facilitation of skills retraining. It presents a model that generates practical, utilitarian<br />

strategies for retraining adaptive cognitive, emotional, behavioral and social skills, as well as strategies for overcoming common<br />

obstacles to utilizing methods that promote effective skills acquisition.<br />

Keywords: Neurorehabilitation, holistic rehabilitation, cognitive rehabilitation, traumatic <strong>brain</strong> inju~y, habit retraining<br />

1. Introduction formidable challenges in the field of neurorehabilitation.<br />

Traditional treatments provided by clinical psy-<br />

Persistent cognitive, emotional, behavioral and chology and psychiatry, special education, physical resocial<br />

dysfunction following <strong>brain</strong> <strong>injury</strong> present habilitation, and related fields have proven inadequate<br />

for addressing these persisting - sequelae and their as-<br />

-<br />

sociated disablement-~44,651. As a result, specialized<br />

*Address for correspondence: Michael F. Martelli, Ph.D., Tree<br />

cognitive rehabilitation services have been designed<br />

of Life Services, Inc., 13458 North Gayton, Richmond, VA 23233,<br />

USA. Tel,: +1 804 307 5293; F ~ +I ~ 775 : 305 4791; ~ - ~ ~ i l with : the goal of minimizing cognitive and behavioral<br />

mfrnartelli@<strong>villa</strong><strong>martelli</strong>.com; Wehpage: http://<strong>villa</strong><strong>martelli</strong>.com. impairments and improving functional behaviors.<br />

ISSN 1053-8135/08/$17.00 @ 2008 - IOS Press and the authors. All rights reserved<br />

.

116 M.F: Marteffi et a/. /Skiff <strong>reacquisition</strong> <strong>after</strong> <strong>acquired</strong> <strong>brain</strong> <strong>injury</strong><br />

Schutz and Trainor [65] recently reviewed the status<br />

of cognitive rehabilitation as a neurorehabilitation<br />

treatment paradigm. They suggest that there has been<br />

a shift from the original meaning as a paradigm of<br />

complex, sophisticated, and integrated interventions,<br />

to more recent poorly conceptualized, compartmentalized<br />

and largely ineffectual service modalities. Based<br />

on considerable empirical support for treatment efficacy<br />

for the former "holistic" programs, they proposed a<br />

new definition. Cognitive rehabilitation is defined as<br />

a systematic, theory based program of "integrated di-<br />

4. A procedure that (a) promotes rehabilitative strat-<br />

egy use adapted to individual's neurobehavioral<br />

losses, inherent reinforcement preferences, and<br />

coping style, that is (b) reliant on naturalistic rein-<br />

forcers which (c) highlight relationships to func-<br />

tional goals, (d) utilize social networks, and (e)<br />

employs a simple and appealing cognitive attitu-<br />

dinal system and set of procedures that maximize<br />

motivation.<br />

&tic, experiential, procedural and psychosocial training<br />

aimed at restoring -cognitively cornpromised<br />

adaptation, including decrements in interpersonal<br />

and vocational participation, self-awareness and selfdetermination."<br />

ip. 546). They noted a central focus<br />

on psychosocia~emotional aspects of recovery, recognizing<br />

defective insight and consequent "dearth of adjustive<br />

motivation" as major rehabilitation obstacles.<br />

They recommended that all mediational processes, including<br />

wanting, feeling and thinking, are necessary<br />

targets - of rehabilitation. They further elaborate that<br />

well developed neurorehabilitation programs necessar-<br />

The Holistic Habit Retraining (HHR) neurorehabilitation<br />

mode1 represents a for continuing<br />

neurorehabilitation that integrates psychotherapeutic<br />

strategies with rehabilitation training as necessary<br />

ingredients for the rehabilitation process. HHR aims<br />

to reduce the complexity of conducting psychotherapy<br />

with persons with <strong>acquired</strong> neurological disorders as<br />

well as identifying and facilitating accomplishment of<br />

meaningful individual rehabilitation goals through optimal<br />

learning procedures. HHR accomplishes this by<br />

simplifying and integrating the Processes and methods<br />

of interdependent goal accomplishment in ps~chotherapy<br />

& rehabilitation. At the heart of this model is the deily<br />

do the following: (a) combine systematic treatment sign and presentation of practical, utilitarian strategies<br />

of cognitivehehavioral deficiencies with psychothera- for retraining adaptive cognitive, emotional, behavioral<br />

py and milieu therapy; (b) address many different im- and social skills. This includes strategies for overcompairments<br />

and disabilities, and; (c) strive to supportpar- ing common obstacles to utilizing methods that proticipation,<br />

independence and self managed adaptation<br />

to all aspects of life through use of adaptive strategies<br />

that represent durable adaptive systems that are used in<br />

mote effective habit acquisition.<br />

the real world.<br />

2. Rehabilitation and the Holistic Habit Retraining<br />

In the present paper, a model of holistic neurorehabilitation<br />

that addresses persisting <strong>brain</strong> <strong>injury</strong> seque-<br />

(HHR) model: Rehabilitation is relearning<br />

lae and disablement is examined, along with illustrative Rehabilitation is the Systematic Process of Removing<br />

methodology. This model conceptualizes many <strong>brain</strong><br />

<strong>injury</strong> sequelae in terms of disruption of previously<br />

established hierarchical and interdependent habits that<br />

underlie all efficient, adaptive living skills. The Holistic<br />

Habit Retraining (HHR) model and methodology<br />

of neurorehabilitation [32,35-37,39,40,42,44] is based<br />

upon the following:<br />

Obstacles to Independence & Accessing Opportunities<br />

for Achievements of Desired Goals in the areas of love,<br />

Work and Play! The Purpose of Rehabilitation is to<br />

Change Fate!<br />

- M.E Martelli, PhD & the Obstacle Busters ABI<br />

Cope Group, circa 1994 -<br />

1. The "automatic learning" and "errorless learning" Adaptive behavior is reliant on intact central nervous<br />

literature and evidence supporting efficacy of this system (CNS) function. The ability to learn and store<br />

methodology for skills relearning <strong>after</strong> <strong>brain</strong> in- information and execute tasks related to that behavior<br />

jury [261;<br />

is dependent on intact <strong>brain</strong> cells. Damage to <strong>brain</strong><br />

2. A task analytic examination of acquisition of rele- cells that occurs in <strong>acquired</strong> <strong>brain</strong> <strong>injury</strong> (ABI) can divant<br />

behavioral habits as a model for constructing minish or delete the stored knowledge and adaptive beskills<br />

retraining protocols;<br />

havioral habits that sustain important human abilities.<br />

3. Analysis of organic, reactive, developmental, and Despite the fact that damage to <strong>brain</strong> cells can impair<br />

characterologic obstacles and facilitators of strat- adaptive behavior and habits, the ability to reorganize<br />

egy utilization; and<br />

and support re-learning is seldom erased 1161.

The highly evolved capacity of the human CNS to<br />

support learning is the hallmark of our species. While<br />

the behavior of many animals is controlled primari-<br />

ly by instincts, human behavior is driven by complex<br />

learning and a network of complex behavioral habits<br />

that are established over the lifespan. From birth on,<br />

human behavior is predominantly shaped by learning.<br />

Through the construction of a sequence of hierarchical-<br />

ly arranged habits with more complex learning built on<br />

top of more basic learning, everyday functioning be-<br />

comes an increasingly sophisticated network of habits.<br />

The complex behaviors that make up the average per-<br />

sons everyday behaviors are performed efficiently and<br />

automatically because of the establishment of a hier-<br />

archy of habits <strong>acquired</strong> through incremental learning.<br />

In recognition of the critical role of behavioral habits<br />

to human function, William James, the father of Amer-<br />

ican Psychology, referred to them as the flywheel of<br />

society [20].<br />

Neural plasticity is the mechanism that underlies the<br />

capacity of the human CNS to convert repeatedly per-<br />

formed behaviors into habits. This enables the learn-<br />

ing of complex behaviors that can be performed auto-<br />

matically whereupon important adaptive functions like<br />

concentration, energy and effort are freed up to ad-<br />

dress other tasks. However, damage to neural tissue<br />

can weaken, degrade, or erase some of the most basic<br />

<strong>acquired</strong> habits of adaptive living. Everyday abilities<br />

and routines can be seriously disrupted. and any sem-<br />

blance of efficiency can be lost as some of the interde-<br />

pendent components of automatic behavior disrupt be-<br />

havioral routines. Previously automatic behavior that<br />

had been performed easily or thoughtlessly can require<br />

an enormous amount of effort and conscious control<br />

subsequent to <strong>brain</strong> <strong>injury</strong>.<br />

Although important prior learned habits may be se-<br />

riously degraded or even erased, newly learned habits<br />

can usually be developed as replacements. Importantly,<br />

the primary requirements for both learning and relearn-<br />

ing are becoming increasingly understood. Emotional<br />

state, attitudes and expectancies constitute important<br />

variables for learning and some of the moqt important<br />

variables for relearning [44,77]. Emotions and atti-<br />

tudes can both promote and guide re-establishment of<br />

new habits, or interfere with their development. Nega-<br />

tive expectancies regarding learning, including expec-<br />

tations for only a relatively effortless return of previous<br />

automaticity, or a belief that only childrencan or should<br />

learn, will undermine relearning. Attitudes can facil-<br />

itate or contaminate relearning and fertilize or poison<br />

rehabilitation.<br />

M.E Martelli er al. /Skill <strong>reacquisition</strong> <strong>after</strong> <strong>acquired</strong> <strong>brain</strong> <strong>injury</strong> 117<br />

In the HHR model, three primary and essential in-<br />

gredients for relearning and rehabilitation are empha-<br />

sized. These three basic components, the 3 P's of reha-<br />

bilitation, involve the Plan, Practice and a Promoting<br />

attitude [44]:<br />

- Plan: The plan component is a prescriptive reha-<br />

bilitative strategy and design for stepwise progress<br />

toward relearning a deficient behavioral skill.<br />

These are derived from thorough functional task<br />

analyses. Functional task analyses are the most re-<br />

lied upon building block of relearning in the HHR<br />

model. This involves breaking seemingly com-<br />

plex tasks down into simple component steps, and<br />

putting them into a checklist that can be followed<br />

in a list wise fashion. More specific, concrete, and<br />

conspicuous plans or prescriptions for successful<br />

task completion are more likely to be effectively<br />

utilized [22].<br />

- Practice: The practice or repetition component<br />

is the habit manufacturing process stage. It in-<br />

volves structured, consistent and repeated trials of<br />

practice. conducted over many weeks to months.<br />

It is the cement for learning that makes complex,<br />

challenging and cumbersome or boring tasks more<br />

automatic and effortless. With practice and repe-<br />

tition, even complex tasks become automatic and<br />

habitual. That is, a habit, or our automatic robots,<br />

can perform many tasks for us without special ef-<br />

fort, energy, concentration, memory, or other cog-<br />

nitive demands.<br />

- Promoting attitude: The promoting or facilitat-<br />

ing attitude component represents the fuel for mo-<br />

bilization and persistence of effort that is prerequi-<br />

site for sustaining the repeated practice necessary<br />

for establishing reliable skills learning. Sustaining<br />

motivated practice over numerous repetitions and<br />

aprogressive series of increasingly challenging se-<br />

quences is required to achieve automaticity in per-<br />

formance of adaptive task sequences and behav-<br />

ioral habits. This is especially true in more chal-<br />

lenging situations and where skills require longer<br />

training periods. This promotional attitude build-<br />

ing component fosters continued practice through;<br />

(a) shaping of incremental expectancies; (b) re-<br />

inforcement for incremental gains; and (c) adap-<br />

tive reinterpretation and redirection of any sig-<br />

nificant residual negative emotion. Anger, frus-<br />

tration, depression, fear, pessimism, feelings of<br />

victimization, self pity, hopelessness and/or low<br />

grade chronic despair may be left over from the<br />

early post-<strong>injury</strong> experience of being confronted<br />

by overwhelming deficits [44].

118 M.E Martelli et al. /Skill real cquisition <strong>after</strong> <strong>acquired</strong> <strong>brain</strong> <strong>injury</strong><br />

The HHR model posits that the greatest obstacle to<br />

learning or relearning is the diversion of energy away<br />

from sustained, adaptive goal directed activity and to-<br />

ward inactivity or debilitating activity. Some of the<br />

most potent habit relearning "poisons", or rehabilita-<br />

tion debilitating attitudes, are depression, anger and re-<br />

sentment, feelings of victimization, fear, and inertia.<br />

These obstacles both direct energy away from relearn-<br />

ing and inhibit it. These common catastrophic emo-<br />

tional reactions following <strong>brain</strong> injuries represent sig-<br />

nificant internal obstacles that must be removed as bar-<br />

riers before the very challenging process of relearning<br />

can be optimally engaged [32,35-37,39,40,42,44,49,<br />

501.<br />

3. The catastrophic reaction<br />

Three central postulates of the HHR model are: 1)<br />

significant emotional reactions frequently follow neu-<br />

rological injuries; 2) These reactions often exert per-<br />

sistent negative influences on post <strong>injury</strong> adaptation;<br />

3) Formal treatment of these reactions is frequently re-<br />

quired in order to optimize rehabilitation. Early post<br />

<strong>injury</strong>, an individual's discovery of traumatic loss of<br />

functional abilities and accustomed aspects of the self<br />

can be overwhelmingly devastating. The sudden loss<br />

of limb function, the inability to stand or control one's<br />

bowels, difficulty expressing a need or understanding<br />

another's speech or intentions, or inability to remember<br />

previous events can produce a powerful reaction char-<br />

acterized by acutely intense despair and distress. This<br />

response, which has been observed and described most<br />

clearly <strong>after</strong> left hemisphere cerebrovascular accidents<br />

(CVA) or other neurologic insults, has been referred<br />

to as the "catastrophic reaction" [15]. Kurt Goldstein<br />

observed that in patients with left-hehisphere CVA's,<br />

when faced with "unsolvable tasks", states of ordered<br />

behavior could "decompensate into catastrophic reac-<br />

tions" showing all the characteristics of "acute anxi-<br />

ety". Goldstein interpreted this reaction as the individu-<br />

al struggling to cope with the challenges of the environ-<br />

ment and hisher own changed body. Goldstein argued<br />

that an individual could not be divided into "organs" or<br />

"mind" and "body". Rather than tissue damage, he de-<br />

fined disease as a changed state of adaptation with the<br />

environment. This early biopsychosocial conceptual-<br />

ization posited that "healing" came from adaptation to<br />

conditions causing the new state of person-environment<br />

interaction, and not through "repair".<br />

Importantly, catastrophic or related reactions do not<br />

occur only in the context of left hemispheric lesions<br />

but may reflect a host of situational, personological, or<br />

other biomedical factors. Many post <strong>injury</strong> syndromes<br />

reflect problems in adaptation and coping with persist-<br />

ing <strong>injury</strong> sequelae. Miller [49,50] has described "neu-<br />

rosensitization syndromes" to summarize empirical and<br />

theoretical work in the area of post traumatic disabili-<br />

ty syndromes characterized by long-term demoralizing<br />

<strong>disability</strong>. Persistent postconcussion syndrome, chron-<br />

ic pain, posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, and<br />

other syndromes share many common pathophysiolog-<br />

ical mechanisms and are hypothesized to develop as<br />

the result of progressively enhanced sensitivity or re-<br />

activity of the central nervous system (CNS). A prima-<br />

ry mechanism in the perpetuation of <strong>disability</strong> in these<br />

disorders is an avoidance of stimuli that evoke anxiety<br />

and emotional distress. Because these syndromes are<br />

frequently comorbid, they can create vicious cycles of<br />

impairment and reduced quality of life.<br />

Recent research on constraint induced movement<br />

therapy (CIMT) [28,70-721 offers evidence indicating<br />

that a significant portion of <strong>disability</strong> is explained by<br />

"learned non-use" [71]. This concept is similar to<br />

Seligman's learned helplessness model of depression<br />

and coping [67]. Failure and punishment for use at-<br />

tempts early post <strong>injury</strong> can permanently suppress fu-<br />

ture efforts <strong>after</strong> acute organic damage resolution and<br />

return of potential for cerebral reorganization and re-<br />

training and regrowth for body part use. CIMT and<br />

other emerging research [16] provide empirical sup-<br />

port that neurologic <strong>disability</strong> is an adaptational phe-<br />

nomenon and that learning following <strong>injury</strong> can sup-<br />

press rehabilitation. Moreover, this suppression can be<br />

reversed through relearning to produce significant im-<br />

provements in human function even many years <strong>after</strong><br />

<strong>injury</strong>.<br />

The HHR model recognizes that the initially expe-<br />

rienced acute distress and catastrophic reactions fol-<br />

lowing <strong>injury</strong> usually become less conspicuous over<br />

time and often reach some level of resolution. How-<br />

ever, residual effects can also persist and become more<br />

subtle or concealed. Catastrophic emotional reactions<br />

can be maintained or recapitulated through continued<br />

confrontation of <strong>injury</strong> related deficits and continued<br />

requirement for compensatory efforts that are difficult,<br />

unsuccessful or result in chronic anxiety, frustration<br />

andlor resignation [18,35,37,44,59,60]. These emo-<br />

tions can easily subvert goal directed activity, energetic<br />

efforts and progress leading to feelings of powerless-<br />

ness, helplessness and being overwhelmed by the chal-

*<br />

lenge of coping. That is, the remnants of early catas-<br />

trophic emotional reactions are seen as negative, en-<br />

ergy consuming emotions. They can deplete adaptive<br />

energy, hope and persistent goal directed effort neces-<br />

sary for relearning and rebuilding functional abilities<br />

and optimizing post <strong>injury</strong> adaptation.<br />

The HHR model postulates, as its most critical tenet,<br />

that persisting catastrophic emotional reactions are a<br />

frequent impediment to adaptation that must be re-<br />

solved in order to optimize rehabilitation. Further, con-<br />

siderable anecdotal and observational data and unpub-<br />

lished case reports collected by the authors, along with<br />

emerging research reports in related areas [63,70-721<br />

indicate that the gains that can follow resolution of<br />

the catastrophic reaction, when combined with potent<br />

retraining strategies, can convert into impressive im-<br />

provements in functional status and adaptation even<br />

many years post <strong>injury</strong>.<br />

The proposal that persistent emotional distress must<br />

be reduced in order to improve functional adaptation is<br />

a common theme in post traumatic disorder treatment.<br />

Miller [49,50] observed that the same classes of psy-<br />

chotropic medications are usually the first treatments<br />

for most of these disorders, while psychotherapy is usu-<br />

ally the treatment of choice. Dubovsky [7] described<br />

that the post <strong>injury</strong> psychotherapy relationship "splints"<br />

neurophysiological regulatory mechanisms and pro-<br />

vides a repeated corrective stabilization that eventually<br />

allows normal functioning. In the system of holistic<br />

"neuropsychotherapy" developed by Ben Yishay [4],<br />

psychotherapy is central to the rehabilitation process.<br />

Prigatano [59,60] also strongly articulated the impor-<br />

tance of psychotherapy for facilitating post <strong>injury</strong> adap-<br />

tation. In the HHR model, resolving the persistent<br />

catastrophic emotional reaction is posited as an inte-<br />

gral and necessary part of the rehabilitation training<br />

process.<br />

The rationale and method for resolving the persis-<br />

tent catastrophic reaction in the HHR model is derived<br />

largely from the research literature on learning [64],<br />

cognitive-behavioral psychotherapy, and coping with<br />

anxiety, especially procedures involving graduated ex-<br />

posure and cognitive restructuring [461. Resolving per-<br />

sistent catastrophic emotionarreactions involves three<br />

integrated HHR components:<br />

1) Confronting deficits in an incremental manner in<br />

order to prevent being overwhelmed by distressful<br />

emotion, through graduated exposure.<br />

2) A supportive conceptual framework and rehabilitation<br />

methodology that fosters hope and includes<br />

self-instruction to reinforce graduated successes<br />

M.E Martelli et al. /Skill real ~quisition ajier <strong>acquired</strong> <strong>brain</strong> <strong>injury</strong> 119<br />

in very incremental stages that progress toward<br />

desired goals<br />

3) A rehabilitation methodology that emphasizes er-<br />

rorless learning and task analyses, as described<br />

below. This simultaneously simplifies reacquisi-<br />

tion and habitualization of many basic adaptation-<br />

a1 skills while minimizing anxiety and distressful<br />

emotions that are associated with hopelessness<br />

and failure.<br />

In the HHR methodology, Graduated Exposure (GE)<br />

is an important behavioral anxiety reduction procedure<br />

that involves slowly and incrementally increasing a pa-<br />

tient's exposure to a feared or distressful situation (46,<br />

62,681. It has been applied by the first author for suc-<br />

cessfully reducing disruptive levels of specific post in-<br />

jury anxieties across a wide range of persistent symp-<br />

toms [3,33-40,43,73,78,79].<br />

Critical to the HHR methodology is the intention<br />

to promote learning through calming the CNS and de-<br />

creasing the significant anxiety and negative emotional<br />

states which are consistently shown to be highly disrup-<br />

tive to performance and learning [53]. The envisioning<br />

of a progressively more desirable future is a guiding<br />

principle and "psychoemotional magnet" in HHR that<br />

pulls persons toward their goals. Incremental move-<br />

ment toward desired goals is accomplished to the extent<br />

that a person focuses on the vision of a desirable future,<br />

breaks expectancies and goals into small, progressive<br />

steps, and develops habits that facilitate persistent and<br />

stepwise, goal directed efforts. Patterns of interpreting<br />

events and expectancies of rehabilitation progress rep-<br />

resent predictions of the future. Habitual patterns of ex-<br />

pecting failure or dissatisfaction, or mistreatment, and<br />

habitual patterns of becoming depressed, angry, fearful<br />

andfor resigned are energy depleting debilitative habits<br />

that reinforce <strong>disability</strong> and failure.<br />

The "Five Commandments of Rehabilitation" [32,<br />

35,39,40,42,44] were developed through examination<br />

of the successful adaptive attitudes of rehabilitation pa-<br />

tients who despite poor prognoses made remarkable<br />

progress. These serve as a primary prescription for<br />

countering the catastrophic emotional reactions that<br />

block optimal rehabilitation achievement. They in-<br />

clude (1) making accurate comparisons, (2) learning<br />

new ways to do old things, (3) building one self up,<br />

(4) employing positive self-coaching, and (5) viewing<br />

rehabilitation as a series of small steps each requiring<br />

celebration. These commandments, and some illustra-<br />

tive explanations that are typically given to patients, are<br />

included in Table 1.

120 M.E Martelli et al. /Skill <strong>reacquisition</strong> afier <strong>acquired</strong> <strong>brain</strong> ir~jury<br />

Table 1<br />

Five commandments of rehabilitation<br />

Commandment 1: Thou Shall Make Only Accurate Comparisons. Thou shall not make false comparisons.<br />

That is, it is only fair (and adaptive) to compare oneself to persons with similar injuries, illnesses, disabilities and stress, as this comparison<br />

allows us to accurately measure ourselves. It is unfair to compare ourselves to others without similar challenges, or to ourselves before we<br />

were challenged, as this makes us look poor by comparison.<br />

Commandment 2: Thou Shall Learn New Ways to Do Old Things.<br />

Learning new ways, or finding another way to do desired tasks, vs. giving up & feeling hopeless because the old way doesn't work, is the<br />

key to Challenging obstacles and overcoming them.<br />

. . . Overcome thinking that the old way is the best way (i.e., Stinking Thinking)<br />

Commandment 3: Thou Shall Not Beat Thyself Up . . . Instead, Thou Shall Build Thyself Up!<br />

We clearly understand that when we have a physical <strong>injury</strong>, such as a broken leg, getting mad, yelling at, or hitting (i.e., beating up) the leg<br />

only delays recovery, increases symptoms and pain, and makes us and the leg function worse. We know that pampering the leg, massaging it<br />

and coaxing it along gently & patiently will help it recover. Unfortunately, we too often forget that our <strong>brain</strong>s are similar. An injured <strong>brain</strong><br />

will perform poorly when we get mad with it, or get frustrated. Instead, understanding it, pampering it, being patient, using pacing & coaxing<br />

it along in a supportive way will help us function our best, and help our recovery and rehabilitation. Talking to ourselves in supportive and<br />

understanding ways (vs. getting mad at ourselves for being injured or having difficulty) and coaxing things out gently is a good way of<br />

building ourselves up in order to face the challenges of rehabilitation. Rewarding ourselves for efforts and each small step of progress, despite<br />

tremendous obstacles & challenges, is the best way to build ourselves up!<br />

. . . Child & Spouse Abuse are recognized as illegal and intntoral . . . Sey'Abuse is just as bad!<br />

Commandment 4: Thou Shall View Progress as a Series of Small Steps.<br />

Rehabilitation is appropriately viewed One Step At a Time - by focusing on the gains over where we were when we were one step behind<br />

where we are now, we can focus on the Graduated Successes and feelings of accomplishment (despite giant obstacles) which will leave us<br />

feeling proud and hopeful and enable us to focus and reach the next small step ahead, and make progress through the many small steps<br />

necessary to make substantial progress. Focusing on our current gains and small steps of progress (compared to where we were earlier in<br />

rehab and when we were at our worst) will build hope and a sense of challenge and growing victories (versus comparing ourselves to before<br />

the <strong>injury</strong>, which only makes us feel sad & depressed.<br />

. . . Inch by Inch & It's a Cinch. Meter by Meter; Lifi. is Sweeter:<br />

Commandment 5: Thou Shall Expect Challenge & Strive to Beat It.<br />

By Converting Complaint (I don't want) To Challenge (I want), We Can Shape Our Future Through Our Vision and Driving Thoughts. We<br />

will actively shape our future by focusing on a vision of hope, challenge, control & satisfaction. By changing our focus from complaint<br />

and feelings of victimization & helplessness & pessimism, we can avoid giving up and giving in to a pessimistic prophecy of dissatisfaction<br />

and doom. (cf. "Thou Shall not Pretend to Have a Contract Guaranteeing Freedom from Injury, Disease, Illness or Unfair circumstances or<br />

Significant Stress!")<br />

M.E Martelli, Ph.D: @ 1995<br />

The prescribed attitude "antidotes" captured in<br />

the "Five Commandments of Rehabilitation" are the<br />

essence of the "medicines" that interrupt the rehabilitation<br />

"poison" cycles. Energy tends to be selfpropagating<br />

in a cyclical fashion. Given negative expectancies<br />

and hopelessness, more energy is expended<br />

nonproductively. This depletes and redirects limited<br />

energy and resources away from allocation toward<br />

adaptive relearning and rehabilitation accomplishments.<br />

A habitual depressive response to physical<br />

losses can reduce activity, prevent adaptive relearning,<br />

and lead to increased depression by depletion of<br />

<strong>brain</strong> chemicals associated with positive mood and energy<br />

[46,50]. Ongoing depression, in turn, leads to<br />

poorer progress, more negative expectancy and confirmation<br />

of reasons to be depressed.<br />

The "Five Commandments" represent a cognitive<br />

behavioral prescription for a more positive vision of a<br />

gradually improved future necessary for planning and<br />

successfully practicing compensatory cognitive and be-<br />

persons against depression, anger, and other destructive<br />

emotion. This ensures that energy and motivation will<br />

be available for the persistent pursuit of desired goals,<br />

with each step of progress adding momentum for con-<br />

tinued hope, self-efficacy, energy, and continued effort.<br />

With the addition of potent learning strategies like task<br />

analyses, errorless learning strategies, and scheduling<br />

to help promote routines, energy is increasingly pro-<br />

tected and positively allocated through adaptive inter-<br />

pretations and expectancies. In a cyclic fashion, energy<br />

fueling consistent repeated practice turns these rehabil-<br />

itation promoting strategies into incremental success-<br />

es and increasingly automatic habits. These produce<br />

continued achievements and energy that strengthen the<br />

adaptive interpretations and expectancies that strength-<br />

ens adaptive energy.<br />

To summarize, any behavior that is structured and<br />

consistently repeated will eventually become a habit.<br />

The HHR model promotes both the activity and attitude<br />

routines that will mobilize energy for practicing potent<br />

learning strategies that will help shape patient efforts<br />

havioral strategies. Simultaneously, they help inoculate toward their important goals.

4. Functional task analyses<br />

A task analytic examination of relevant behavioral<br />

habits is the model for constructing slulls retraining<br />

protocols in HHR. Task Analysis is a learning proce-<br />

dure based upon brealung any task, chore. or complex<br />

procedure into single, simple, and logically sequenced<br />

steps. It typically includes recording the steps in a<br />

Checklist [221. The checklist guides task performance<br />

by checlung off each sequential step as it is completed.<br />

Task analyses simplify and optimize task initiation, se-<br />

quencing, completion and follow-up, and make previ-<br />

ously formidable or impossible tasks much easier. Per-<br />

forming a Task Analysis and generating a checklist to<br />

guide behavior assists in errorless learning in persons<br />

with a wide range of neurocognitive difficulties [32,<br />

35-37,4042,441.<br />

A growing body of research is consistently demon-<br />

strating the effectiveness of errorless training methods<br />

across a range of disorders [I, 17,2 1,23-261. This evi-<br />

dence further demonstrates its relative superiority ver-<br />

sus traditional training procedures for persons with sig-<br />

nificant memory problems following <strong>brain</strong> <strong>injury</strong> and<br />

disease [6,8,14,24,26,29,47.64,65,69,74], and for per-<br />

sons with executive impairments [23,57,45].<br />

Task analysis checklists are also especially useful in<br />

countering performance and learning difficulties asso-<br />

ciated with fatigue [41,48,54]. The disruptive effects<br />

of fatigue can be mitigated by reducing the demand<br />

for, and energy consumed by, reasoning, problem solv-<br />

ing and effort associated with planning, organizing and<br />

having to recall, make decisions, sequence and priori-<br />

tize appropriate steps for a task. They provide an er-<br />

rorless learning format, especially when supplemented<br />

with any needed direct instruction or supervision. The<br />

checklist represents the support that ensures: (a) a sim-<br />

plified learning process; (b) successful task comple-<br />

tion; (c) learning of only correct and successful learning<br />

procedures; (d) a reduced number of competing mem-<br />

ory traces and elimination of frustration and distressful<br />

emotional reactions; these can be especially inhibitory<br />

to memory and learning performance in persons with<br />

<strong>brain</strong> <strong>injury</strong>, disease andlor dysfunction.<br />

Task analyses can be beneficial for both basic and<br />

complex behaviors. Most importantly, Task Analy-<br />

ses facilitate re-establishing the efficient routines that<br />

make up normal everyday human behavior and activ-<br />

ity. When the procedures assisted by Task Analyses<br />

are repeated consistently, they eventually become auto-<br />

matic and habitualized. Samples of task Analyses are<br />

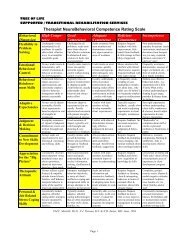

included in Table 2.<br />

M.F: Martelli et al. /Skill <strong>reacquisition</strong> afler <strong>acquired</strong> <strong>brain</strong> injuq 121<br />

To reiterate, in the HHR model, the ingredients for<br />

rebuilding automatic habits are the 3 P's: Plan, Practice,<br />

and Promotional attitude. These components of reha-<br />

bilitation represent a formula for removing obstacles<br />

to continually increasing independence while achiev-<br />

ing incremental progress toward recovery of important<br />

functional life skills.<br />

5. Application of HHR principles and strategies<br />

A case study that illustrates an early application of<br />

the HHR model is that of JF. JF was a 39 year old wom-<br />

an who was seen 2.5 years status post craniotomy for<br />

resection of a very large pituitary adenoma. The tumor<br />

and surgery produced complete blindness, an amnestic<br />

syndrome and numerous vegetative-metabolic distur-<br />

bances. This former architect showed especially severe<br />

memory problems. She was unable to recall the route<br />

out of the bathroom in the house in which she grew up<br />

havingreturned home to be taken care of by her parents<br />

(even <strong>after</strong> living there for 2 years post surgery), and<br />

was only able to conduct over learned activities of daily<br />

living with assistance. She had just been discharged<br />

from the state school for rehabilitation of the visually<br />

impaired due to inability to show any benefit from train-<br />

ing. She had been deemed incapable of new learning<br />

by virtually all health and rehabilitation professionals,<br />

who recommended that her elderly parents institution-<br />

alize her. JF was admitted for assessment of capacity to<br />

benefit from rehabilitation in a transitional living pro-<br />

gram for persons with <strong>brain</strong> <strong>injury</strong>. This was offered<br />

as a last resort in the hopes of altering permanent dis-<br />

ability and avoiding need for institutional care. While<br />

admitted, she was seen for a more focal and supportive<br />

approach to memory rehabilitation screening. Previ-<br />

ously unable to demonstrate recall of any new informa-<br />

tion <strong>after</strong> 10 to 20 seconds, her memory was assessed<br />

in a relaxed atmosphere, in a non confronting manner<br />

during a birthday party and discussion invoking her<br />

more intact remote memory. Numerous repetitions of<br />

the examiner's name were conducted while recall was<br />

subsequently prompted <strong>after</strong> one minute with calming<br />

self talk, humor and the following repeated phrases:<br />

"Patience, persistence, coax it out gently, build yourself<br />

up, don't beat yourself up . . . if it comes it will come<br />

in calmness and that will be okay, and if it doesn't,<br />

that's very, very good too, because you persisted with-<br />

out quitting and you have the best persistence I've ever<br />

seen,'' along with lots of support, encouragement and<br />

instruction in calming, paced breathing.

TA Samples: Single Tasks<br />

'Making A Bed' "Cheatlist"<br />

1. Strip sheets, blankets and pillow cases<br />

2. Put blankets and pillows on table<br />

3. Take break<br />

4. Get sheets and pillow cases from closet<br />

5. Put on fitted sheet<br />

6. Put on top sheet, evening it out<br />

7. Put on blankets and tuck in comers<br />

8. Put pillow cases on pillow<br />

9. Put comforter on bed<br />

M.E Martelli et al. /Skill <strong>reacquisition</strong> <strong>after</strong> <strong>acquired</strong> <strong>brain</strong> <strong>injury</strong><br />

TA Sample: Daily Habits & Routines<br />

AT'S Initiative~Energy Retrainer<br />

MORNING<br />

- Wash Face<br />

- Shave<br />

- Apply medication to face if needed<br />

- Brush Teeth<br />

- Comb Hair<br />

- Dress before "morning" nap<br />

- Check finger nails & toe nails; trim when needed<br />

-Check hair length and get a haircut as needed<br />

- Shower and wash hair<br />

-Perform an ActivitylChore (Choose from Menu)<br />

-Check Schedule (e.g., M,W,F = Y; Tues = RedX)<br />

-Check your appearance before leaving the house<br />

AFTERNOON<br />

-Fill Out Chart (Behavioral Activity Monitor & Points)<br />

- . . . etc.<br />

EVENING<br />

- Eat Dinner<br />

- PRN (PowerRelaxationNap; Use Tape)<br />

-Engage in Evening Activity<br />

- . . . etc.<br />

-Prep for Bed (PJ'S, Brush Teeth, etc.)<br />

- BedTime<br />

On this occasion, <strong>after</strong> approximately 5 minutes of<br />

supportively coached persistence of effort, JF demon-<br />

strated her first documented successful recall of new in-<br />

formation. Her second documented recall was that her<br />

memory had actually functioned and that she had been<br />

able to eventually recall something, even though she<br />

couldn't recall what it was. Despite these promising<br />

accomplishments, JF's overall progress was judged in-<br />

sufficient to justify continued residential rehabilitation<br />

treatment. Nonetheless, her elderly parents refused to<br />

institutionalize her and continued to care for her in their<br />

home. Over the next two years, she was seen twice<br />

Table 2<br />

Task analysis samples<br />

TA Samples: Daily Activity Trainers<br />

DH's Daily Plan Checklist<br />

MORNING<br />

-Wake 6:00 AM to the Alarm Clock<br />

- Take Medication<br />

- Make Bed<br />

- Shower<br />

- Get Dressed<br />

- Comb Hair<br />

- Make and eat breakfast<br />

- Clear, rinse, stack breakfast dishes (for pm wash)<br />

-Wipe counter, table stovetop if needed<br />

- Feed animals<br />

- Brush teeth<br />

- Gather items to take for the day<br />

- Leave house at 7:OO; go to Grandma's<br />

REHAB CENTER<br />

-Arrive between 7:3&8:00Am by van<br />

- Follow Morning Schedule (In Rehab SchedBook)<br />

- Lunch at 11:30, Take medication<br />

- Follow Afternoon schedule<br />

- Leave for Grandma's between 3:3@4:00<br />

LATE AFTERNOON<br />

- Dinner at Grandma's & take medication<br />

- Home between 6:0&7:00PM<br />

- Get mail, read & sort; put bills on microwave<br />

WENING: PREPARE FOR THE NEXT DAY<br />

Loundry if needed (clothes, sheets,batb/'kit towels)<br />

- separate colors and whites<br />

- set water level<br />

- . . . etc.<br />

Kitchen<br />

-wash dishes<br />

- . . . etc.<br />

Bathroom if needed<br />

-clean sink, tub, countertop<br />

- . . . etc.<br />

ReladFree Time<br />

Prepare for Bed<br />

- Floss/Brush Teeth<br />

-Wash Face<br />

- Shave<br />

-Put away clothes (in hamper or drawerlcloset)<br />

Pick & lay out clothes to wear for the next day<br />

Set Alarm for 6:00 AM<br />

weekly in an outpatient neurobehavioral "Cope" group,<br />

and once to twice a week for tutoring from a humorous<br />

and friendly ex-patient volunteer. Her mother and vol-<br />

unteer were instructed in use of repetition (e.g., "Three-<br />

Peat" - a timely term in the early 90's when the Chicago<br />

Bulls had won three consecutive NBA championships)<br />

and association as memory enhancement strategies, and<br />

"tiny step" expectations with positive shaping and lib-<br />

eral praise, as reinforcers of continued hope and efforts.<br />

With this scant treatment, JF slowly showed increasing<br />

recall for more and more information. Increasing social<br />

activities were especially facilitative as they seemed to

eawaken this previously very gregarious woman and<br />

fuel slow but incremental gains in new memory. No-<br />

tably, JF contributed to the development of the "Five<br />

Commandments of Rehabilitation" by offering inspira-<br />

tional one liners, coined or borrowed from Sunday tele-<br />

vision preachers, during outpatient group attendance.<br />

At four years post <strong>injury</strong>, despite strenuous resistance<br />

to even stronger advocacy, she was re-accepted at the<br />

state school for the visually impaired for a one week<br />

evaluation for ability to benefit from a typing recording<br />

device. She amazed the staff with her ability to learn<br />

the basics of Braille and the use of a Braille typewrit-<br />

er that also served as a compensatory memory device.<br />

Two years later, she was typing 60 words a minute and<br />

had learned to use adaptive text-voice equipment and<br />

was working a volunteer job and applying for more<br />

competitive jobs with the support of a job coach.<br />

Per the HHR model, JF's case is conceptualized in<br />

terms of the suppression of memory by the underly-<br />

ing catastrophic emotion experienced every time shc<br />

attempted to recall information. JF was undoubtedly<br />

sensitized to distressful emotion by her blindness, her<br />

repeated confrontations with it due to arnnestic syn-<br />

drome, and her punishing failures with every memory<br />

effort. JF could not be expected to endure the contin-<br />

ued distress that accompanied repeated failed recollec-<br />

tion efforts without hope for success. However, when<br />

recollection efforts were incremented for a single, sim-<br />

ple piece of socially relevant information and persis-<br />

tent recollection effort was strongly supported through<br />

emotionally calming talk, a discovery occurred. It was<br />

learned that she did retain at least some memory stor-<br />

age ability - that is, she demonstrated slow but intact<br />

storage and retrieval capacity only <strong>after</strong> five minutes.<br />

JF's ability to recall that her memory could work,<br />

given patient persistence and supportive coaching from<br />

a caring and empathic professional whom she liked,<br />

ushered in a hopeful expectancy that undoubtedly trans-<br />

formed her. The content for shaping this expectancy is<br />

now transcribed in the "5 Commandments". The for-<br />

mula for delivery within the HHR model format is one<br />

that borrows from the knowledge of psychotherapy and<br />

personality change. In what is arguably the best scien-<br />

tific analysis of psychotherapy to date, Wampold [75]<br />

demonstrates that specific therapy techniques are not<br />

active in and of themselves, and are active only be-<br />

cause they are a component of the healing context.<br />

The overwhelming conclusion of all major reviews of<br />

psychotherapy data [5,9-13,19,56,75] show that ther-<br />

apist relationship factors play a much more important<br />

role in influencing outcome than treatment approach-<br />

M.E Martelli et al. /Skill <strong>reacquisition</strong> <strong>after</strong> <strong>acquired</strong> <strong>brain</strong> <strong>injury</strong> 123<br />

es. Wampold [75] and many others recommend defin-<br />

ing therapist competence by the quahty of their out-<br />

comes. The HHR model adopts this same recommen-<br />

dation with regard to rehabilitationists, prescribes spe-<br />

cific strategies for facilitating strong therapeutic rela-<br />

tionships, and offers a model of rehabilitation delivery<br />

that can be summarized by the u s : Belationship, &-<br />

tionale and &tual [40]. That is, a strong, positive and<br />

trusting therapeutic Relationship is required to facilitate<br />

emotional trust while calming anxieties and emotion-<br />

al distress, and inspiring hope and collaborative effort.<br />

A credible Rationale is required to offer a believable<br />

treatment model and procedure that is logically con-<br />

vincing and sets positive expectancies. Finally, a cred-<br />

ible Ritual or methodology and procedural intemen-<br />

tions that produces measurable successes and confirm<br />

expectations, hope and continued efforts is required.<br />

Since the HHR model and methodology have been<br />

developed, refined and consistently applied in our clin-<br />

ical treatment, numerous other illustrative HHR case<br />

studies have been catalogued and are being written up.<br />

Some are included on the <strong>villa</strong><strong>martelli</strong>.com <strong>disability</strong><br />

resources webpage [3 1 1, including an interesting one<br />

involving rehabilitation of severe dorsolateral frontal<br />

lobe <strong>injury</strong> related initiation problems [41]. Although<br />

space limitations do not allow review or discussion of<br />

other case studies, or even many other specific HHR<br />

strategies, an instructive introduction to building reha-<br />

bilitation protocols using the "3 P's" approach is includ-<br />

ed on the <strong>villa</strong><strong>martelli</strong>.com resources website [3 1.1. The<br />

online protocol segments illustrate samples of applica-<br />

tion of task analytic derived, errorless learning based<br />

slulls building protocols (the Plan), individually adapt-<br />

ed reinforcement via a palatable cognitive attitudinal<br />

approach for countering inherent resistances to strate-<br />

gy utilization and practice, and promoting increment-<br />

ed goal achievement and reinforcement from graduated<br />

successes (the Practice and Promotional attitude com-<br />

ponents). Complete protocols and a larger sample of<br />

illustrative adapted strategies can be downloaded from<br />

this website [3 I].<br />

6. Conclusion<br />

The HHR model of neurorehabilitation is a skills<br />

re-aquisition paradigm which postulates that a primary<br />

learning function of the human CNS involves "habit"<br />

manufacturing - that is, converting repeated behav-<br />

iors that are functionally adaptive into efficient and<br />

automatic habits. For example, it is adaptive to re-

124 M.F: Martelli et a[. /Skill <strong>reacquisition</strong> <strong>after</strong> <strong>acquired</strong> <strong>brain</strong> <strong>injury</strong><br />

member how to walk, so the sequences involved in<br />

walking are chained together in a task analysis that<br />

makes it automatic so that performance requires min-<br />

imal thought and energy. The same conversion oc-<br />

curs when such habits as attentional focusing, memory,<br />

and multi-tasking are <strong>acquired</strong> and automated through<br />

chaining of the component steps. Through learning,<br />

internally incorporating the tasks that are involved in<br />

getting dressed, or remembering what to take with us<br />

when we leave the house, etc. are <strong>acquired</strong> as habits<br />

through natural task analysis that sequences behaviors<br />

as if we were learning automatic task inventories. The<br />

same is true for self control habits ranging from ini-<br />

tiation and awareness to inhibition, which involve the<br />

very complex chaining of multiple tasks to produce the<br />

highest level executive shlls habits.<br />

Although HHR shares many features with other<br />

holistic neurorehabilitation models, it also provides a<br />

distinctive and unique approach. HHR is a parsimo-<br />

nious model that is relatively simple to understand and<br />

apply. It offers an uncomplicated and intuitively ap-<br />

pealing model and methodology for devising and indi-<br />

vidualizing specific retraining protocols. Protocol tem-<br />

plates have been developed for a broad range of relevant<br />

skills areas. Most importantly, HHR recognizes the<br />

powerful importance of psychotherapy, or neuropsy-<br />

chotherapy, synchronizing it with potent and compati-<br />

ble learning methods. It integrates psychotherapy as an<br />

inseparable part of the rehabilitation process. HHR em-<br />

powers therapists and family members as agents armed<br />

with highly potent neurorehabilitation-specific learn-<br />

ing and psychotherapeutic strategies. Finally, and ul-<br />

timately, HHR aims to expand "neuropsychotherapeu-<br />

tic" rehabilitation beyond enhancing emotional adjust-<br />

ment and functional compensation to include promo-<br />

tion of neuroplastic based rehabilitation of cognitive,<br />

behavioral and physical capabilities.<br />

References<br />

[l] S. Akhtar, C.J. Moulin and P.C. Bowie, Are people with mild<br />

cognitive impairment aware of the benefits of errorless learn-<br />

ing? Neuropsychol Rehabilitation 16 (2006), 329-346.<br />

121 N.D. Anderson and F.I. Craik, The mnemonic mechanisms of<br />

errorless learning, Neuropsychologia 44 (2006). 2806-2813.<br />

131 M.C. Bender, M.F. Martelli and N.D. Zasler, A Graduated Ex-<br />

posure Protocol for Post Traumatic Driving Anxiety, Present-<br />

ed at the Williamsburg Traumatic Brain Injury Conference,<br />

27th Annual Meeting, Williamsburg, 2003.<br />

[4] Y. Ben-Yisbay, Postacute Neuropsychological Rehabilitation,<br />

in: lntenlational Handbook of Neuropsychological Reha-<br />

bilitation, Christenson and Uzzell, eds, Kluwer Academ-<br />

iclPlenum, New York, 2000.<br />

A.E. Bergin and S.L. Garfield, eds, Handbook of Psychotherapy<br />

and Behavior Change: An Empirical Analysis, 4th ed.,<br />

John Wiley and Sons, New York. 1994.<br />

L. Clare, B.A. Wilson, G. Carter, I. Roth and J.R. Hodges,<br />

Relearning face-name associations in early Alzheimer's disease,<br />

Nerrropsychology 16 (2002), 538-547. Y. Ben-Yishay,<br />

Postacute Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, in: Internntiona1<br />

Handbook of Nerrrop.sychologica1 Rehabilitation, Chnstenson<br />

and Uzzell, eds. Kluwer Academic/Plenum. New York.<br />

2000.<br />

S.L. Dubovsky. Mind-Body Deceptions: The Psychosomatics<br />

ofEveryday Life, Norton, New York, 1997.<br />

J.M. Ducharme, "Errorless" rehabilitation strategies of proactive<br />

intervention for individuals with <strong>brain</strong> <strong>injury</strong> and their<br />

children, Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation 18 (2003),<br />

88-105.<br />

J.D. Frank, Therapeutic components of psychotherapy: A 25year<br />

progress report of research, Journal of Nervous and Mental<br />

Diseases 159 (1974). 325-342.<br />

J.D. Frank. Therapeutic components shared by all psychotherapies,<br />

in: Psychotherapy Research and Behavior Change, J.H.<br />

Harvey and M.M. Peeks, eds, American Psychological Association,<br />

Washington, DC, 1982, pp. 9-37.<br />

J.D. Frank, The placebo is psychotherapy, The Behavioral and<br />

Brain Sciences 6 (1983), 291-292.<br />

J.D. Frank and J.B. Frank. Persuasion and Healing: A Comparative<br />

Study of Psychotherapy, The Johns Hopkins University<br />

Press. Baltimore. MD. 1991.<br />

J.D. Frank, Persuasion and Healing: A Comparative Study of<br />

Psychotherapy. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore,<br />

MD, 1993.<br />

E.L. Glisky and D.L. Schacter, Extending the limits of complex<br />

learning in organic amnesia: computer training in a vocational<br />

domain, Neuropsychologia 27 (1989), 107-120.<br />

K. Goldstein, The Organism: A Holistic Approach to Biology<br />

Derived from Pathological Data in Man, American Book Co:<br />

1939: Zone Books, New York. 1995.<br />

R. Greenwood, The future of rehabilitation, Lies in retraining,<br />

replacement, and regrowth, British Medical Journal 323<br />

(2001), 1082-1083.<br />

C. Haslam, D. Gilroy, S. Black and T. Beesley, How successful<br />

is errorless learning in supporting memory for high and lowlevel<br />

knowledge in dementia? Neuropsychol Rehabil5 (2006),<br />

505-536.<br />

C.A. Hopewell, The Neuropsychological Assessment of Personality<br />

and Emotional Changes <strong>after</strong> Traumatic Brain Injury,<br />

IMH-Network, Limited, Sparks, NV, 2001.<br />

M.A. Hubble, B.L. Duncan and S.D. Miller, eds, The Heart<br />

and Soul of Change: What Works in Therapy, American Psychological<br />

Association, Washington, DC, 1999.<br />

W. James, The Principles of Psychology. Vol. 2, Henry Holt<br />

and Co, New York, 1890.<br />

J. Jerome, E.P. Frantino and P. Sturmey. The effects of errorless<br />

learning and backward chaining on the acquisition of Internet<br />

skills in adults with developmental disabilities, JAppl Behav<br />

Anal 40 (2007), 185-189.<br />

D.H. Jonassen. M. Tessmer and W.H. Hannum, Task Analysis:<br />

Methods for Instructional Design, Lawrence Erlbaum<br />

Associates, Mahwah, NJ, 1999.<br />

R.S. Kern, R.P. Liberman, A. Kopelowicz, J. Mintz and M.F.<br />

Green, Applications of Errorless Learning for Improving Work<br />

Performance in Persons With Schizophrenia, An~erican Journal<br />

of Psychiatry 159 (2002). 921-1926.

R.S. Kern, M.F. Green, J. Mintz and R.P. Liberman, Does 'er-<br />

rorless learning' compensate for neurocognitive impairments<br />

in the work rehabilitation of persons with schizophrenia? Psy-<br />

chol Med 33 (2003). 433-442.<br />

R.S. Kern, M.F. Green, S. Mitchell, A. Kopelowicz, J. Mintz<br />

and R.P. Liberman, Extensions of errorless learning for social<br />

problem-solving deficits in schizophrenia, American Journal<br />

of Psychiatry 162 (2005). 5 13-5 19.<br />

R.P. Kessels and E.H. de Haan, Implicit learning in memory<br />

rehabilitation: a meta-analysis on errorless learning and van-<br />

ishing cues methods, Journal of Clinical and Experimental<br />

Neuropsychology 25 (2003), 805-814.<br />

R.P. Kessels, S.T. Boekhorst and A. Postma, The contribu-<br />

tion of implicit and explicit memory to the effects of error-<br />

less learning: a comparison between young and older adults,<br />

Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society 11<br />

(2005).<br />

A. Kunkel, B. Kopp, G. ~'uller, K. Villringer, A. Villringer, E.<br />

Taub and H. Flor, Constraint-induced movement therapy for<br />

motor recovery in chronic stroke patients, Archives of Physical<br />

Medicine and Rehabilitation 80 (1999), 624-628.<br />

N.R.C. Leng, A.G. Copello and A. Sayegh, Learning <strong>after</strong><br />

<strong>brain</strong> <strong>injury</strong> by the method of vanishing cues: a case study,<br />

Behavioural Psychotherapy 19 (1991), 173-181.<br />

P. MacMillan and M.F. Martelli, Modification of treatment<br />

disruptive anxiety in an inpatient rehabilitation setting: A<br />

case study, Presented at the Rehabilitation Progress annu-<br />

al meeting. Richmond, 1989. http://<strong>villa</strong><strong>martelli</strong>.com/TX<br />

disrupt-Anx-Mgmtl989.pdf.<br />

M.F. Martelli, Villa Martelli Internet Disability Resources: A<br />

Comprehensive Listing of Some of the Most Useful Infor-<br />

mation and Links for Professionals and Persons Who Assess,<br />

Treat, or Cope With Physical andor Neurologic Injury andor<br />

Impairment [Comprehensive Website]. Richmond, VA: Au-<br />

thor. World Wide Web: http://<strong>villa</strong>Martelli.corn, 1999-2007.<br />

M.F. Martelli, Model and Method for Improving Vocational<br />

Rehabilitation Outcomes Through Collaboration With Neu-<br />

ropsychological ~ehabilitationisis. Lecture presented to the<br />

lrst Combined Training Conference of the VA. Rehab. Assoc.,<br />

VA. Assoc. of community Rehabilitation Programs and the<br />

VA. Assoc. of Persons in Supported Employment, Virginia<br />

Beach, 1997.<br />

M.F. Martelli. Assessment of Avoidance Conditioned Pain Re-<br />

lated Disability (ACPRD): Kinesiophobia and Cogniphobia.<br />

HeadsUp: RSS Newsletter 2 (1999).<br />

M.F. Martelli. P.J. MacMillan, N.D. Zasler and R.L. Grayson,<br />

Kinesiophobia and Cogniphobia: Avoidance Conditioned<br />

Pain Related Disability, Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology<br />

14 (1999), 804. http://<strong>villa</strong><strong>martelli</strong>.codnanpostersl999.htm.<br />

M.F. Martelli, Neurobehavioral Rehabilitation: Empirical Ev-<br />

idence for Habit Retraining. Candlelight Presentation at the<br />

2Ist Annual Symposium of the Brain Injury Association of<br />

America, Minneapolis, 2002.<br />

M.F. Martelli, Treatment of Conimonly Neglected Sequelae<br />

Following Traumatic Brain Injury Presented at the New York<br />

Academy of Traumatic Brain Injury, New York, 2002.<br />

M.F. Martelli, Integrating Psychotllerapy With Brain Injury<br />

Rehabilitation for Rebuilding the Shattered SeK Workshop<br />

presented at the annual meeting of the Coalition of Clini-<br />

cal Practitioners in Neuropsychology (CCPN), Dallas, 2003.<br />

http://<strong>villa</strong><strong>martelli</strong>.com/NPTXRehabCCPN2003.pdf.<br />

M.F. Martelli, Methods for Controlling Distress, Pain and<br />

Sensory Disorders Following Brain Injury, Lecture presented<br />

M.E Martelli et al. /Skill <strong>reacquisition</strong> <strong>after</strong> <strong>acquired</strong> <strong>brain</strong> <strong>injury</strong> 125<br />

at the Universidad de Se<strong>villa</strong> and Centro de Rehabilitacion de<br />

Daiio Cerebro. Seville, Spain, 2003.<br />

M.F. Martelli, Neuropsychotherapy: Cognitive and Behav-<br />

ioral Approaches to Managing Pain and other Sensory Dis-<br />

orders Following Brain Injury. Presented at the 4th annual<br />

meeting of the Brain Injury Association of Wyoming, Lander,<br />

2003.<br />

M.F. Martelli, Strategic Rehabilitation for Seniors with Neu-<br />

rologic Impairments, Workshop presented at the annual meet-<br />

ing of the Coalition of Clinical Practitioners in Neuropsy-<br />

chology (CCPN), Las Vegas, 2005. http://<strong>villa</strong><strong>martelli</strong>.cod<br />

CCPN2005HHRSlides2.pdf.<br />

M.F. Martelli, A.W. Siegal and N.D. Zasler, Grand Rounds:<br />

Frontal lobe syndromes following neurologic insult, Bulletin<br />

of the National Academy ofNeuropsychology 17 (2002), 8-17.<br />

M.F. Martelli, Integrating Psychotherapy with Brain Injury<br />

Rehabilitation for Rebuilding the Shattered Se& Workshop<br />

presented at the annual meeting of the Coalition of Clinical<br />

Practitioners in Neuropsychology (CCPN), Dallas, 2003.<br />

M.F. Martelli, N.D. Zasler, K. Nicholson and M.C. Ben-<br />

der. Psychological, neuropsychological and medical consid-<br />

erations in the assessment and management of pain, Jour-<br />

nal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation 19 (2004), 10-28. http:<br />

//<strong>villa</strong><strong>martelli</strong>.com/lNSS PainNP2005- Hndout.pdf.<br />

M.F. Martelli, N.D. Zasler and P.J. Tiernan, Skill Acquisition<br />

and Automatic Process Development After Brain Injury: A<br />

Holistic Habit Retraining Model, Brain Injury Professional 2<br />

(2005), 10-16.<br />

S. Martins, B. Guillery-Girard, I. Jambaqd. 0 . Dulac and F.<br />

Eustache, How children suffering severe amnesic syndrome<br />

acquire new concepts? Neuropsychologia 44 (2006). 2792-<br />

2805.<br />

J.C. Masters, T.B. Burish, S.C. Hollon and D.C. Rimm, Behav-<br />

ior Therapy: Techniques and Empirical Findings, Harcourt<br />

Brace Jovanovich, New York, 1987.<br />

R.S. Masters, K.M. MacMahon and H.S. Pall, Implicit Motor<br />

Learning in Parkinson's Disease, Rehabilitation Psychology<br />

49 (2004), 79-82.<br />

R.S. Masters. J.M. Poolton and J.P. Maxwell, Stable implicit<br />

motor processes despite aerobic locomotor fatigue, Conscious<br />

Cognition. Apr 28,17470398 (2007). Epub ahead of print.<br />

L. Miller, Shocks to the System: Psychotherapy of Traumatic<br />

Disability Syndromes, Norton, New York, 1998.<br />

L. Miller, Neurosensitization: A model for persistent <strong>disability</strong><br />

in chronic pain, depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder<br />

following <strong>injury</strong>, Neurorehabilitation 14 (2000), 25-32.<br />

S.D. Miller, B.L. Duncan and M.A. Hubble, Escape from Ba-<br />

bel: Towarda Untfiing Longuage for Psychotherapy Practice,<br />

W.W. Norton, New York, 1997.<br />

E.C. Miotto, Cognitive rehabilitation of amnesia <strong>after</strong> virus<br />

encephalitis: A case report, Neuropsyclwl Rehabill7 (2007),<br />

551-566.<br />

J.E. Ormrod, Human Learning, (3rd edition), Menill, Prentice<br />

Hall Australia Pty Ltd, Sydney, New South Wales, 1999.<br />

A.J. Orrell, F.F. Eves and R.S. Masters, Motor learning of a<br />

dynamic balancing task <strong>after</strong> stroke: implicit implications for<br />

stroke rehabilitation, Physical Therapy 86 (2006), 369-380.<br />

M. Page, B.A. Wilson, A. Shiel, G. Carter and D. Nonis, What<br />

is the locus of the errorless-learning advantage?, Neuropsy-<br />

chologia 44 (2006). 90-100.<br />

C.H. Patterson, Foundations for a Systematic Eclectic Psy-<br />

chotherapy, Psycl~otherapy 26 (1989), 427435. [Also in: Un-<br />

derstanding Psychotherapy: Fijij Years of Client-Centered<br />

Tlleo? and Practice. PCCS Books, 20001.

126 M.E Martelli et al. /Skill <strong>reacquisition</strong> aper <strong>acquired</strong> <strong>brain</strong> injurj<br />

A.L. Pitel, H. Beaunieux, N. Lebaron, F. Joyeux, B. Des-<br />

granges and E Eustache. Two case studies in the application<br />

of errorless learning techniques in memory impaired patients<br />

with additional executive deficits, Brain Inj 10 (2006). 1099-<br />

11 10.<br />

J.W. Pope and R.S. Kern, An "errorful" learning deficit in<br />

schizophrenia? Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neu-<br />

mpsychology 28 (2006). 101-1 10.<br />

G.P. Prigatano, Psychiatric aspects of head <strong>injury</strong>: Problem<br />

areas and suggested guidelines for research, in: Neurobehav-<br />

ioral Recoveryfmm Head Injury, H.S. Levin, J. Grafman and<br />

H.M. Eisenberg, eds, Oxford University Press, New York,<br />

1987, pp. 215-231.<br />

G. Prigatano, Principles of Neuropsychological Rehabilita-<br />

tion, Oxford, New York, 1999.<br />

G.A. Riley. A.J. Brennan and T. Powell, Threat appraisal and<br />

avoidance <strong>after</strong> traumatic <strong>brain</strong> <strong>injury</strong>: why and how often are<br />

activities avoided?, Brain Injury 18 (2004). 871-888.<br />

D.C. Rim and J.C. Masters. Behavior Therapy: Techniques<br />

and Empirical Findings, (2nd ed.), Academic Press, New<br />

York, 1979.<br />

R.J. Sbordone. Cognitive rehabilitation of the traumatic <strong>brain</strong>-<br />

injured patient in the year 2000, Psychotherapy in Private<br />

Practice 8 (1990). 129-138.<br />

D. Schacter, Searching for Memo?. Basicbooks, New York,<br />

1996.<br />

M. Schmitter-Edgecombe and L. Beglinger, Acquisition of<br />

skilled visual search performance following severe closed-<br />

head <strong>injury</strong>, Journal of the International Neuropsychological<br />

Society 7 (2001). 615-630.<br />

L.E. Schutz and K. Trainor, Evaluation of cognitive rehabili-<br />

tation as a treatment paradigm, Brain Injury 21 (2007). 545-<br />

557.<br />

M.E.P. Seligman and D.M. Isaacowitz, Learned helplessness,<br />

in: Encyclopedia of Stress, G. Fink, ed., Academic Press, San<br />

Diego, 2000.<br />

M.D. Spiegler, Contemporay Behavioral Therapy, (4th ed.),<br />

Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.<br />

E.J. Squires, N.M. Hunkin and A.J. Parkin, Errorless learning<br />

of novel associations in amnesia, Neuropsychologia 35 (1997),<br />

1103-1111.<br />

E. Taub, Movement in nonhuman primates deprived of so-<br />

matosensory feedback, Exercise and Sports Science Reviews<br />

4 (1977), 335-374.<br />

E. Taub, J.E. Crago and G. Uswatte, Constraint-induced move-<br />

ment therapy: A new approach to treatment in physical reha-<br />

bilitation, Rehabilitation Psychology 43 (1998). 152-170.<br />

E. Taub, G. Uswatte and D.M. Moms, Improved motor recov-<br />

ery <strong>after</strong> stroke and massive cortical reorganization follow-<br />

ing Constraint-Induced Movement therapy, Phys Med Rehabil<br />

Clin NAm 14 (2003), S77-S91. ix.<br />

D.D. Todd, M.F. Martelli and R.L. Grayson, The Cogni-<br />

phobia Scale (C-scale), Test in the public domain, 1998.<br />

http://<strong>villa</strong><strong>martelli</strong>.com/nanposters1999.htm<br />

M. Verfaellie, L.S. Cermak, S.P. Blackford and S. Weiss,<br />

Strategic and automatic priming of semantic memory in alco-<br />

hoIic Korsakoff patients, Brain Cognition 13 (1990), 178-192.<br />

B.E. Wampold, The Great Psychotherapy Debate: Models,<br />

Methods, and Findings. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, New<br />

Jersey, 2001.<br />

F.C. Wilson and T. Manley, Sustained attention training and<br />

errorless learning facilitates self care functioning and chronic<br />

ipsilesional neglect following severe traumatic <strong>brain</strong> <strong>injury</strong>,<br />

Neuropsychological Rehabilitation 13 (2003). 537-548.<br />

R.L. Wood, Understanding the 'miserable minority'; a<br />

diathesis-stress paradigm for post concussional syndrome,<br />

Brain Injury 18 (2004), 1135-1 153.<br />

N.D. Zasler and M.F. Martelli, Stare of the Art Reviews:<br />

Functional Disorders in Rehabilitation, Hanley and Bel-<br />

fus, Philadelphia, 2002. http://<strong>villa</strong><strong>martelli</strong>.com/STARSAbs&<br />

ChapLnks.htrn.<br />

N.D. Zasler, M.E Martelli and K. Nicholson, Chronic Pain<br />

(and Traumatic Brain Injury), in: Textbook of Traumatic<br />

Brain Injury, J.M. Silver, S.C. T.W. McAllister and Yudofsky,<br />

eds, American Psychiatric Publishing, Arlington, VA, 2005,<br />

pp. 419436.