Gamma-Grassridge: Compensation-Specialist Study - Eskom

Gamma-Grassridge: Compensation-Specialist Study - Eskom

Gamma-Grassridge: Compensation-Specialist Study - Eskom

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>Gamma</strong>-<strong>Grassridge</strong>:<br />

<strong>Compensation</strong>-<strong>Specialist</strong> <strong>Study</strong><br />

by<br />

Erwin Rode<br />

assisted by<br />

Nancy Graham<br />

Rode & Associates CC<br />

Tel. 021 946 2480<br />

22 October 2007

Contents<br />

1. Introduction 1<br />

1.1 The visual effect of lines 1<br />

1.2 Maintenance nuisance 1<br />

1.3 Multiple lines 1<br />

1.4 Public relations 1<br />

2. Aim and objectives 2<br />

3. Review of mainly North-American countries 2<br />

3.1 Visual encumbrance 2<br />

3.2 Urban, residential land 3<br />

3.3 Agricultural land 4<br />

3.4 Perceptions and fears of EMF health hazard 5<br />

3.5 Technical alternatives 6<br />

3.6 <strong>Compensation</strong> for first servitude 6<br />

3.7 <strong>Compensation</strong> for additional rights in existing corridors 9<br />

4. Review of European countries 10<br />

4.1 <strong>Compensation</strong> 10<br />

4.2 Utility corridors 10<br />

5. Review of the South Africa legal situation 11<br />

5.1 Acts governing expropriation by <strong>Eskom</strong> 11<br />

5.2 Constructive expropriation 12<br />

5.3 Servitudes are expropriations 12<br />

5.4 How compensation is calculated 12<br />

5.4.1 <strong>Compensation</strong> for a property with full rights 13<br />

5.4.2 <strong>Compensation</strong> for the taking of a servitude 15<br />

6. Project and operational claims 16<br />

7. Renting versus lump-sum payment 17<br />

8. How to quantify loss of business 19<br />

9. Summary of conclusions 20<br />

10. Recommendations 23<br />

Reference list 27<br />

Annexures 1, 2 & 3

1. Introduction:<br />

1<br />

The background to this study is an accumulation of compensation-related issues<br />

that have started to affect the environment in which <strong>Eskom</strong> operates. Some of<br />

these issues were highlighted to this author by <strong>Eskom</strong> officials during two separate<br />

interviews at Megawatt Park on May 8 and September 28, 2007.<br />

1.1 The visual effect of lines:<br />

In the early 1990s, <strong>Eskom</strong> still paid one-third of the market value of the land for<br />

the servitude area. Then eco tourism and game farming arrived, which meant<br />

that visual impairment became a financial factor, and <strong>Eskom</strong> now pays 100% of<br />

market value.<br />

At present, the affected neighbour is not compensated for, for instance, visual<br />

impairment.<br />

1.2 Maintenance nuisance:<br />

The presence of <strong>Eskom</strong> maintenance personnel will be an impediment as long as<br />

the line exists (maintenance applies to both lines and roads). Examples are:<br />

o Hunting has to be stopped temporarily.<br />

o Entering of <strong>Eskom</strong> personnel results in expenditure on fuel and time lost when<br />

the farmer or members of his staff has to investigate the presence of strangers<br />

on the property.<br />

o <strong>Eskom</strong> personnel “do not close gates”.<br />

o Helicopter noise disturbs game.<br />

1.3 Multiple lines:<br />

A case can be made for paying more compensation should and when more than<br />

one line is constructed on a servitude.<br />

1.4 Public relations and “consumerism”:<br />

Land owners are becoming more aware of their rights and have become less pliant<br />

when negotiating servitudes. A contributing factor might be the higher percentage<br />

of foreign land owners who have a stronger culture of “consumerism”.<br />

But, in addition, <strong>Eskom</strong> has a serious PR problem because farmers tend to see it<br />

as an agency of a hostile government.<br />

As a result, in respect of the Venetia line at Louis Trichardt, farmers argue market<br />

value is not acceptable as compensation in the light of their complaints. Also, in<br />

respect of the Venetia line, a combative Transvaal Landbou-Unie (TLU) demands<br />

R100 000 per km or R32 000 per ha, compared to the <strong>Eskom</strong> offer of R2 500 per<br />

ha. Thus, it seems <strong>Eskom</strong> will have to talk to organised agriculture on a national<br />

level.<br />

There seems to be a perception that <strong>Eskom</strong> is reluctant to pay claims for damages,<br />

which may have two root causes. Firstly, there is the possibility that there<br />

is maladministration on the part of <strong>Eskom</strong> in the settling claims. Secondly, and<br />

this is a fact, <strong>Eskom</strong>, as a matter of policy, only pays for claims when <strong>Eskom</strong> had<br />

been negligent, e.g. fires caused by sparks, caused by poor maintenance. Thus,

2<br />

if in this example, <strong>Eskom</strong> had actually done the maintenance just prior to the fire,<br />

<strong>Eskom</strong> would refuse to entertain a damages claim. This legalistic stance by <strong>Eskom</strong><br />

might be the cause of much animosity.<br />

The alienation of farmers is inevitably going to lead to delays in constructing infrastructure,<br />

especially when farms have to be expropriated.<br />

2. Aim and objectives<br />

Thus, the aim of this study is to serve as an aid to <strong>Eskom</strong> Transmission’s management<br />

in formulating a compensation policy and valuation approach with respect<br />

to the proposed <strong>Gamma</strong>-<strong>Grassridge</strong> power lines. With this in mind, the specific<br />

objectives are:<br />

• To suggest methods of compensation when acquiring a servitude; and the<br />

formulation of alternative proposals that could be applied, e.g. outright lumpsum<br />

payout versus renting of a servitude. In doing so, consideration is to be<br />

given to administrative aspects related to different compensation options.<br />

• The consideration and analysis of compensation-calculation methods to cater<br />

for loss of business due to the proposed transmission lines, viz. direct salescomparison<br />

method vs. discounted cash flow.<br />

• The consideration of compensation-calculation methods to deal with cumulative<br />

transmission line servitudes.<br />

• Ways to improve the compensation system in respect of project and operational<br />

claims, e.g. fires from lightning strikes, animal deaths (being scared<br />

and running into fences due to live-wire maintenance by helicopter, animal<br />

losses when gates are left open).<br />

3. Review of mainly North-American countries<br />

The majority of studies on the impact of transmission lines on property values<br />

have been conducted in the United States and Canada. This review of mostly<br />

peer-reviewed literature looks at these international studies and attempts to relate<br />

these geographic-specific studies to the proposed <strong>Eskom</strong> <strong>Gamma</strong>-<strong>Grassridge</strong><br />

765 kV transmission line. Most of the studies are concerned with the impact on<br />

residential property values; however, the majority of land impacted in this project<br />

is agricultural.<br />

Power lines have widely dispersed benefits, but the negative impacts are concentrated<br />

on those living near the line (Gregory & Von Winterfeldt, 1996). In general,<br />

all the impact studies show that the presence of transmission lines negatively affect<br />

property values. The most reliable studies use regression analysis and show<br />

a reduction in mean house prices of between 2 and 10 percent. The impact,<br />

however, differs according to distance from the line: properties within 15 metres<br />

experience a loss of 6 to 9 percent, whereas those within 62 m lose 1 to 6 percent<br />

of their value. The proximity of pylons has an even greater negative impact<br />

(Sims & Dent, 2005).<br />

3.1 Visual encumbrance<br />

The most commonly cited impact of transmission lines of any voltage or height is<br />

visual encumbrance. Colwell (1990) states that developers often increase the lot<br />

size of a property adjacent to an easement 1 (servitude) to mitigate the negative<br />

1<br />

A type of servitude, the right to use of another’s land for a specific purpose. It can be for a specified<br />

period or permanent.

3<br />

impact. Many prior studies, however, do not hold lot size constant and, therefore,<br />

some have found a positive impact on property values. Colwell (ibid), found that<br />

negative value effects due to proximity to a line were experienced regardless of<br />

whether a house was on an easement or not, which shows that it is not purely the<br />

restrictions of the easement which impact the value of the property. This is of importance<br />

because it is difficult for these property owners to claim compensation<br />

from the utility company. Colwell (ibid) also states that the negative impact reduced<br />

over time, which could be due to natural screening of lines by tree growth<br />

or residents may have adapted to the sight.<br />

There are conflicting results on the impact of pylons or towers on property values.<br />

Colwell & Foley (1979) found that the presence of a tower on an easement did<br />

not have a significant impact, while Hamilton & Schwann (1995) found that they<br />

had a significant negative impact on adjacent properties. Des Rosiers (2002) analysed<br />

the impact of visual encumbrance of power lines and pylons using 507<br />

house sales in Greater Montreal between 1991 and 1996 in a multiple-regression<br />

model. The conclusion reached was that the location and extent of the view of the<br />

line or pylon were important in determining the value decline. The value of properties<br />

adjacent to an easement and facing a pylon declined by 9,6% on average;<br />

however, those properties along the easement one or two lots away from a pylon<br />

had increased values of between 7,4% and 9,2% because these properties had<br />

greater visual clearance, privacy and recreational use of the easement. Those<br />

properties not adjacent to the line but within 50 to 150m had values decline by<br />

5,3% because they had the visual encumbrance but no proximity advantages.<br />

Luxury houses suffered greater decline in value than lower-end houses (Fourie et<br />

al., 2003; Des Rosiers, 2002).<br />

In order to decrease visual impacts, United States utility companies have landscaped<br />

the easement, painted pylons green and introduced new, less intrusive<br />

tower designs. According Priestly & Evans (1996) less than 50% of residents felt<br />

these measures made a difference to the visual impact and it was suggested that<br />

the local community be consulted as to the colours, landscaping and designs used<br />

in order to best decrease visual encumbrance.<br />

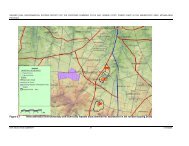

<strong>Eskom</strong> plans to reduce visual encumbrance in the <strong>Gamma</strong>-<strong>Grassridge</strong> corridor by<br />

aligning lines “at the base of mountains, plateaus and ridges … [and using] existing<br />

passages through mountains”. Also, if the second proposed line is eventually<br />

required, it can be constructed parallel to the first line (ACER, 2006: 109).<br />

Visual encumbrance is typically a major factor in urban, residential transmission<br />

lines, but increasingly it could be expected to become a factor affecting values of<br />

rural properties, and businesses on such properties, in the light of the growing<br />

incidence of eco tourism.<br />

3.2 Urban, residential land<br />

Most international studies look at the impact of transmission lines on residential<br />

property values. Some studies have found no significant effect on property values<br />

but, as mentioned previously, in general, methodologically robust studies find a<br />

value decline of between 2% and 10% and property values increase with greater<br />

distance from the line (Kroll & Priestly, 1992; Sims & Dent, 2005; Colwell &<br />

Foley, 1979). Different geographic locations and methodologies make it difficult<br />

to compare study results. Properties in New Zealand, like those in the United<br />

Kingdom, can be built directly beneath a power line, unlike in the United States<br />

and Canada. A New Zealand residential study found a 10% decline in values, and<br />

UK valuers and estate agents estimated the negative impact from transmission<br />

lines to be between 5% and 10%. In the UK, property developers have begun to

4<br />

place low-cost and social housing closest to lines (Haider & Haroun, 2000; Sims &<br />

Dent, 2005). This contrasts with Toronto, Canada, where those areas with transmission<br />

lines are not run-down or low-income but are often desirable because<br />

transmission lines are placed near transportation networks (Haider & Haroun,<br />

2000).<br />

Appraisers (valuers) from 47 US states participated in a survey on whether high<br />

voltage lines affect residential property values, and the response showed that<br />

84% believed it did and the mean estimated decline in value was 10%. New England<br />

had a higher estimated value decline, which is probably due to greater<br />

awareness of the environmental issues surrounding such lines, and the higher<br />

population density means more properties would be affected by power lines (Delaney<br />

& Timmons, 1992).<br />

The issues raised by residents in residential neighbourhoods next to transmission<br />

lines are the visual encumbrance, safety concern, noise and fear of possible<br />

health hazards from electromagnetic field (EMF) exposure, the latter which will be<br />

discussed in detail further (Delaney & Timmons, 1992). Houses in residential areas<br />

are far closer to transmission lines than those on agricultural land, therefore<br />

the effect of transmission lines on agricultural property values is expected to differ.<br />

3.3 Agricultural land<br />

Boyer et al’s study on 1000 agricultural property sales in Canada from 1966-77 is<br />

still the definitive analysis of the effect of transmission lines on agricultural land<br />

values. Boyer et al looked at the difference between the ‘per-acre value’ means of<br />

sales near a transmission line and the mean values in a control area. Per-acre<br />

values near the line were 16-29% lower than those in the control area and properties<br />

with less than 10 acres had almost twice the percentage loss as those<br />

properties with more than 50 acres (Kroll & Priestly, 1992; Gregory & von Winterfeldt,<br />

1996).<br />

Appraiser studies show that agricultural land values experience a greater negative<br />

effect due to power lines than residential land, but the effect depends on the degree<br />

of disruption to farming activities and irrigation. Most studies showed that<br />

agricultural landowners objected more to the inconvenience of the line rather<br />

than the effect on property values (Kroll & Priestly, 1992).<br />

According to the Public Service Commission of Wisconsin report (2004), the impact<br />

on agricultural land depends on the line design and type of farming. A<br />

transmission line could affect the operation and movement of field machinery and<br />

irrigation equipment, fieldwork patterns may need to be altered, soils are compacted,<br />

wind breaks may be removed, and weed encroachment is harder to control<br />

beneath the lines. According to the Environmental Impact Statement for the<br />

Schultz-Hanford power line project, most crops can still be grown and livestock<br />

can graze. The height of trees and crops in the servitude are, however, controlled<br />

to prevent a fire hazard (Bonneville Power Authority, 2003a).<br />

Access roads often need to be constructed by the utility company for the construction<br />

and maintenance of the line once in operation. Landowners in the<br />

<strong>Gamma</strong>-<strong>Grassridge</strong> corridor have security concerns related to access roads and<br />

fencing because of the possibility of poachers, stock theft and damage to crops<br />

and infrastructure and this may need to be compensated for; however, there is<br />

no precedent in the international literature. Another novel concern is that helicopters<br />

flying over the land to do aerial maintenance of the lines make animals skit-

5<br />

tish and they can injure or kill themselves by running into fences as a result<br />

(ACER, 2006).<br />

Agricultural landowners are also concerned with the impact if EMF exposure on<br />

their animals and crops. Studies on the continuous exposure of grazing animals to<br />

EMF show that the reproductive functions and pregnancy of cows are not affected,<br />

and cows and sheep are never underneath the lines for long periods.<br />

Sheep and cattle exposure to EMF also does not affect their levels of the hormone<br />

melatonin, which is important for seasonal breeders. Plant responses such as<br />

germination, seedling emergence growth and production, and flowering are also<br />

not affected (E x ponent & T. Dan Bracken, Inc, 2001). <strong>Eskom</strong> commissioned an<br />

EMF study which reviews all the major studies on EMF exposure on humans, animals<br />

and plants (Pretorius, 2006).<br />

The only possible impact on cattle is that stray voltage — known as neutral-toearth<br />

voltage, and which is often unnoticed by humans — is felt by cattle. It affects<br />

their behaviour and can lead to increased milking time and sometimes decreased<br />

milk production. A cow may receive an electric shock when it makes contact<br />

with a water trough, and this results in hesitation in approaching troughs,<br />

nervousness at milking, and increased defecation and urination during the process.<br />

This effect can be mitigated by using additional grounding where there is one<br />

or more milliamps of stray voltage (Public Service Commission of Wisconsin,<br />

2004; American Transmission Company, 2005).<br />

3.4 Perceptions and fears of EMF health hazard<br />

The impact of EMF exposure on humans is of greater concern to the general public.<br />

The strength of the electric fields produced by 765 kV lines is 3 kV/m and the<br />

maximum level determined by the International Radiation Protection Association<br />

is 5 kV/m. Vegetation and buildings significantly reduce the strength of electric,<br />

but not magnetic, fields (Fourie et al, 2003). “In 2001, the International Agency<br />

for Research on Cancer classified power frequency EMFs as a ‘possible’ human<br />

carcinogen on the basis of childhood leukaemia studies” (Von Winterfeldt et al.,<br />

2004: 1501). Two of these studies were Swedish, published in 1992, and increased<br />

public awareness in the United States of the possible health hazard (Gallimore<br />

& Jayne, 1999). Many other studies have shown no effect due to EMF exposure<br />

and the question of whether EMF exposure results in increased cancer risk<br />

is widely debated in the literature, and thus far the evidence is inconclusive.<br />

What is of concern for the impact of transmission lines on property values is,<br />

however, not whether there is scientific evidence of an adverse health impact but<br />

rather the impact of the negative perceptions and public fears on property values.<br />

Property values are a mental concept and depend on people’s attitudes and<br />

perceptions. The problem with a hazard such as EMF exposure is that it is “novel,<br />

unseen, difficult to control through individual action, delayed in its effects [and]<br />

perceived to increase cancer frequency” (Gallimore & Jayne, 1999: 247). Therefore,<br />

the increased public concern and stigmatization associated with EMF transmission<br />

lines in recent decades impact property values. A landmark case (Criscuola<br />

vs. Power Authority of State of New York, 1993) ruled that whether the EMF<br />

danger is a fact is irrelevant to the issue of the market value impact. A claimant is<br />

no longer expected to give scientific evidence of the health impact but rather evidence<br />

of a prevalent public perception of so-called ‘cancerphobia’. This fear is not<br />

required to be reasonable (Rikon, 1996; Jaconetty, 2001; Gallimore & Jayne,<br />

1999). This marketplace-fear theory is not endorsed by the United States Supreme<br />

Court and Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals, who call it ‘junk science’, and<br />

California will not apply this principle in inverse condemnation cases, where damages<br />

are being claimed where a power line was in existence prior to an owner ac-

6<br />

quiring the property. In general, US courts “are becoming more flexible and admitting<br />

testimony of subjective fear in the marketplace” (Jaconetty, 2001:27). In<br />

the US, evidence of marketplace fear is well established, but the question is to<br />

what extent is such a public fear prevalent in South Africa, and therefore, likely to<br />

affect property values (Rikon, 1996).<br />

According to a study by Gallimore & Jayne (1999), those living further from the<br />

line saw the health risk as greater than those who lived next to it. This may be<br />

because, according to Priestly & Evans (1995), those residents who use the rightof-way<br />

for recreation purposes perceive lower health and safety risks; and perhaps<br />

those living near a line are more likely to use this land. Those with greater<br />

negative perceptions of transmission lines were generally older, had higher occupational<br />

status and had lived in the area prior to the construction of the line. This<br />

study showed that an individual’s characteristics and relationship to the line determines<br />

their perceptions and, therefore, while a current property owner may<br />

not believe the EMF health risk, buyers’ decisions are influenced by the perceptions<br />

of future buyers and resale value (Priestly & Evans, 1995; Gallimore &<br />

Jayne, 1999).<br />

3.5 Technical alternatives<br />

Some of the literature discusses the possibility of placing transmission lines underground,<br />

as this is shown to dramatically increase affected property values<br />

(Von Winterfeldt et al., 2004). This can be done for lower voltage lines, but lines<br />

higher than 132 kV are prohibitively costly to bury and heavy insulation and large<br />

servitudes are required (Elliot & Wadley, 2004). In the case of a 765 kV underground<br />

line, a servitude as wide as a 10-lane highway may be required and these<br />

areas cannot be used for farming activities once construction is completed. If the<br />

proposed second <strong>Gamma</strong>-<strong>Grassridge</strong> 765 kV line is required in the future, it could<br />

be constructed parallel to the original line; however, this will require a larger servitude<br />

in both cases and visual impacts will be greater in the latter (ACER, 2006).<br />

A moderate-cost retrofitting alternative is re-phasing or split phasing transmission<br />

lines. Split phasing involves two or more conductors per phase, which increase<br />

power transfer capability, and if the geometry of the design makes the centroids<br />

of each phase concentric, the magnetic fields are reduced (Von Winterfeldt et al,<br />

2004; Woolery & Ferguson, 1996).<br />

3.6 <strong>Compensation</strong> for first servitude<br />

The abbreviated definition of market value is “the price at which a willing seller<br />

would sell and a willing buyer would buy” at usual market conditions (American<br />

Institute of Real Estate Appraisers cited in Gregory & Von Winterfeldt, 1996:<br />

203). In the case of utility companies acquiring a servitude, there is no equality<br />

between buyer and seller. There is no exchange of property, but rather an estimation<br />

of loss; and there is a difference between what people would be prepared<br />

to pay to obtain a good and what they would require to be willing to accept its<br />

loss or damage (Gregory & von Winterfeldt, 1996). In the United States, and<br />

most countries worldwide, including South Africa, utility companies have powers<br />

of eminent domain 2 whereby, subject to the Public Utility Commission’s approval,<br />

they can take (expropriate) private property for public use, provided ‘just compensation’<br />

is paid. In the United States, these powers are not often used, as negotiations<br />

are usually successful. However, the fact that utilities have such powers<br />

can skew good-faith negotiations (Hutchinson & Rowan-Robinson, 2002; The<br />

Pennsylvania Code, 2007; Landowners Association of Wyoming, ND). The conditions<br />

surrounding the acquisition of the servitude are also not ‘usual market con-<br />

2 The power to take private property for public use with just compensation (expropriation).

7<br />

ditions’ because the landowners do not have a say in which portion of their land<br />

they sell or lease and when this construction will occur (Gregory & Von Winterfeldt,<br />

1996). However, in South Africa, landowners do have a say in the alignment<br />

of the servitude and therefore, where towers will be constructed.<br />

In many states in the United States, courts will allow compensation for impairment<br />

of the view from a property, but not for the loss of visibility of the property.<br />

According to Colwell (1990), negative value effects due to visual encumbrance<br />

are also experienced by those without transmission lines and pylons on<br />

their property; however, not many courts allow view impairment compensation<br />

for such properties.<br />

As stated previously, United States courts are becoming more flexible in recent<br />

years in awarding compensation for marketplace fear of EMF exposure. However,<br />

the <strong>Eskom</strong> Scoping Report does not address the issue of compensation due to<br />

marketplace fear in South Africa (ACER, 2006). As stated above, even if potential<br />

buyers do not have negative perceptions of transmission lines themselves, they<br />

are concerned with the resale value of their properties and this, therefore, needs<br />

to be accounted for in compensation (Rikon, 1996; Gallimore & Jayne, 1999). The<br />

issue of circularity in the determination of property values must also be taken into<br />

account because, for instance, in the United Kingdom, valuers were issued guidelines<br />

to take into consideration that public fears may affect the marketability and<br />

future value of properties. This could, of course, lead to valuers decreasing property<br />

values, which in turn increases the public’s fear that transmission lines, in<br />

particular EMF exposure, affect property values (Gallimore & Jayne, 1999).<br />

The evidence for the health impact of EMF exposure due to transmission lines is<br />

inconclusive; however, utility companies may consider paying more to increase<br />

the width of servitudes in case their liability is increased due to future conclusive<br />

scientific evidence. This measure could remove or reduce the magnitude of possible<br />

future liabilities (Bryant & Epley, 1998). Utilities could also further investigate<br />

the source of the transmission line stigma to better educate the public, thereby<br />

possibly altering their negative perceptions (Elliot & Wadley, 2002).<br />

Thompson & Suntum (2006) discuss two valuation approaches that are similar to<br />

those in South Africa:<br />

(a) Paying the fair market value of the portion taken and severance damages for<br />

the remainder, or<br />

(b) Using the ‘before and after’ rule whereby the compensation paid is the difference<br />

between the fair market value of the whole parcel before, and the value<br />

of the remainder after, the purchase.<br />

In determining before and after values for ‘just compensation’, the matched-pairs<br />

sales analysis seems to be the most robust method as this measures people’s actual<br />

behaviour as opposed to their perceptions, which often differ. Data on similar<br />

sales along a transmission line corridor before and after the construction of the<br />

line should be compared. However, where such data is unavailable, actual market<br />

sales of comparable unaffected properties (which are adjusted according to location,<br />

physical characteristics and time and terms of sale) are compared with sales<br />

data of properties next to a transmission line (Bryant & Epley, 1998; Rikon,<br />

1996; Gregory & Von Winterfeldt, 1996).<br />

The matched-pairs sales method is far easier to use to determine compensation<br />

within an urban, residential setting because similar sales along the corridor are<br />

more numerous and occur more often. Agricultural sales data are much less<br />

common, which could explain why such little research has been done on the im-

8<br />

pact of transmission lines on agricultural land values. In the case of poor market<br />

evidence to calculate the fair market value before and after, the discounted<br />

cash flow approach can be used, whereby all future income and expenditure<br />

are discounted back to the present day at an appropriate discount rate. However,<br />

this method is highly sensitive to changes in key variables, so comparable sales<br />

should be used where available (Hutchinson & Rowan-Robinson, 2001). Agricultural<br />

land also differs so greatly because there are many types of agricultural<br />

use, different qualities of land and also the availability of resources differ for<br />

each parcel (Kroll & Priestly, 1992).<br />

In the United Kingdom, most power lines over agricultural land are constructed<br />

according to wayleave 3 agreements rather than easements. A wayleave is an<br />

agreement for right of use of land and can be terminated after the period of lease<br />

expires; the landowner can give notice of termination or, if the property is sold,<br />

the agreement is not binding on the successor. The wayleave and easement<br />

payment in the UK is calculated per tower and per kilometre of overhead lines<br />

across the property, and the rates are based on the underlying rental value (National<br />

Association of Real Estate Appraisers, 1999; National Grid, 2006; Hutchinson<br />

& Rowan-Robinson, 2001).<br />

In the UK, enhanced compensation of 150% of the arable rate is paid where the<br />

movement of machinery in commercial orchards and hop gardens is hampered by<br />

the presence of towers (Valuation Office Agency, 2000). The redesign of irrigation<br />

systems also needs to be compensated for if the placement of the line interferes<br />

with these. The compensation damages also need to include both the loss<br />

of land within the servitude and, where a portion of land is severed and can no<br />

longer be utilised, the loss of land outside the servitude (Bonneville Power Authority,<br />

2003b; Thompson & Suntum, 2006).<br />

The smaller farms in the southern section of the proposed <strong>Eskom</strong> corridor, from<br />

Kleinpoort to the <strong>Grassridge</strong> substation outside the Nelson Mandela Bay metropolis,<br />

are more likely to have portions severed by transmission lines than those larger<br />

farms in the northern section of the Karoo (ACER, 2006).<br />

Where the transmission line is permanent and deforestation of the corridor is<br />

required, this land becomes sterile and the land value is reduced sharply. Therefore,<br />

its value reduction and its future potential income loss need to be compensated<br />

for. For arable land, only the land displaced by the apparatus and that<br />

which is severed and of no use is sterilised (Hutchinson & Rowan-Robinson,<br />

2001).<br />

<strong>Eskom</strong>’s policy is that trees and crops higher than 4 m as well as dwellings are<br />

not allowed within the servitude. Most agriculture in the <strong>Gamma</strong>-<strong>Grassridge</strong> corridor<br />

is citrus, livestock and game farming and most of the terrain is sparsely<br />

vegetated. A landowner would suffer considerable loss if the line crosses citrus<br />

orchards and must be duly compensated (Bonneville Power Authority, 2003b;<br />

ACER, 2006). Disturbance and damages to land or movables during construction<br />

and subsequent maintenance are also subject to compensation (Hutchinson<br />

& Rowan-Robinson, 2001).<br />

There is easy access from existing roads for most of the proposed corridor for the<br />

<strong>Gamma</strong>-<strong>Grassridge</strong> line project. Where roads do need to be constructed, they<br />

will be aligned and constructed according to the landowner’s specifications so that<br />

the road may serve both <strong>Eskom</strong> and the landowner. In the Schultz-Hanford<br />

3 A wayleave is an agreement between the utility company and owner/occupier which gives the utility<br />

the right to “install, maintain, adjust, repair, alter, keep and enter to inspect apparatus on, under or<br />

over their property” (Openreach, 2006)

9<br />

transmission line project, if the landowner has equal benefit from the new access<br />

road, only 50% of the full compensation fee is paid (Bonneville Power Authority,<br />

2003b).<br />

3.7 <strong>Compensation</strong> for additional rights in existing corridors<br />

In the USA, a new industry requiring the use of right-of-way corridors for communication<br />

lines and fibre-optic cables emerged during the closing years of the<br />

20 th century. These communication lines are responsible for transmitting data involving<br />

national security, banking, the Worldwide Web, teleconferencing and most<br />

types of data transmission (Bolton & Sick, 1999). This created a market for additional<br />

property rights within existing right-of-way corridors, and, of<br />

course, the need to value these rights. As a consequence of the robust demand<br />

for these new rights-of-way, a multitude of sales and leases were concluded. One<br />

might expect that appraisers (valuers) would look upon these as comparables for<br />

valuation purposes.<br />

In this respect, Bolton & Sick (1999) discuss the differences between the valuation<br />

approach taken by the condemnors (utility companies) and the landowners.<br />

In the evaluation of a taking of additional property rights within an existing corridor,<br />

the former typically values the property using the pro rata share of the<br />

easement (servitude) value using ‘across the fence’ (ATF) values 4 . The authors<br />

correctly point out that this methodology does not conform to appraisal practices<br />

because in an existing corridor the ‘highest and best use’ (see below) “cannot be<br />

anything other than for those kind of uses that are already found within the corridor”.<br />

Furthermore, in Texas, amounts paid by utilities with eminent domain (power of<br />

expropriation) are legally inadmissible as comparable evidence to determine<br />

compensation. The obvious reason for this is that such transactions are not arms<br />

length, given the threat of coercion (expropriation).<br />

The proper valuation methodology should be that of the value based on the ‘highest<br />

and best use’, which is defined as “the reasonably probable and legal use of<br />

vacant land or an improved property, which is physically possible, appropriately<br />

supported, financially feasible and that results in the highest value”. The highest<br />

and best use is usually the same as the current land use of the corridor, which in<br />

most cases will be much higher than ATF values (Bolton & Sick, 1999).<br />

Thus, if the land required by the utility also had potential for consolidation of<br />

fields or for sub-division for residential development, the just compensation<br />

will reflect this highest and best use (Public Service Commission of Wisconsin,<br />

2004; Fourie et al, 2003). This potentiality principal also applies to South Africa<br />

(Gildenhuys, 2001: 301).<br />

It is inevitable that this American trend to create additional rights within existing<br />

corridors will soon reach South African shores. For instance, MTN announced in<br />

September 2007 that it intends spending R1,3 billion over the next two years on<br />

an optic-fibre network, covering 5 000 km (Sake24, Die Burger). The question is:<br />

where does MTN intend laying these cables if not in existing corridors?<br />

4 ‘At (or across) the fence’ value is the value of land adjacent to a transmission line. The premise is<br />

that “the corridor land should be worth at least as much as the land through which it passes”. (Lusvardi<br />

& Warren, 2001)

10<br />

By creating a corridor that would allow for additional rights in the future, <strong>Eskom</strong><br />

can potentially add more value to its corridors than it might have expected until<br />

now. <strong>Eskom</strong> will be well advised to keep this in mind when negotiating new corridors<br />

with owners. In the USA, telecommunication companies had rented old dormant<br />

railway rights of way from the railways, without compensation to the owners<br />

over whose land these corridors run, and this resulted in long drawn-out class<br />

action suits against these communication companies (Lusvardi & Warren, 2001).<br />

4. Review of European countries<br />

Various entities in the USA commissioned a study of right-of-way practises in<br />

Europe (US Department of Transportation, 2002). The focus of the study was on<br />

highways, and it covered the following countries: Norway, Germany, the Netherlands<br />

and England. The study is valuable for our purposes because of its comprehensiveness<br />

as well as the alternative view. In this chapter, we summarise the<br />

study’s findings as they pertain to our study.<br />

The countries that the study team visited have an underlying philosophy of sensitivity<br />

to the needs of property owners.<br />

Practises used in these countries encourage property-owner involvement before<br />

completion of final right-of-way plans and they use an extensive property-owner<br />

interview process. Also, they make a conscientious effort to limit the number of<br />

people contacting the property owner. Thus, one person would be assigned to do<br />

the valuation, the acquisition negotiations and manage relocation services.<br />

4.1 <strong>Compensation</strong><br />

In many cases, compensation includes provisions for payment for land acquired,<br />

damages to remaining property, and relocation reimbursements. The impact on<br />

properties outside the project limits is also considered.<br />

The countries all provide liberal payments to businesses affected by property<br />

acquisition, project construction or highway operations. These payments range<br />

from the liquidation and acquisition of businesses to the negotiated reimbursement<br />

of moving and relocation costs and incidental expenses incurred by displaced<br />

businesses.<br />

Each country has a method for facilitating early possession or acquisition.<br />

These methods include mediation, advance payment and advance right-of-entry.<br />

Several countries use geographic information system (GIS) technology to track<br />

land uses, including right-of-way.<br />

4.2 Utility corridors<br />

As a result of their observations, the American study team recommended that<br />

State Departments of Transportation (DOTs) consider developing utility corridors,<br />

including placing conduits for future use and using joint trenching techniques, as<br />

well as requiring utility companies to coordinate installation of facilities within<br />

these corridors. The team also recommended that State DOTs should encourage<br />

the use of pipelines as a transportation mode.<br />

The implication of these trends, read together with the rise in the need for optic-<br />

fibre corridors in the USA, is that <strong>Eskom</strong> should assume that other utilities will

11<br />

want to share its high-voltage corridors. This has important legal and financial<br />

implications. In the USA, communication companies that had rented old unused<br />

railway servitudes without the consent of the owners eventually had to face protracted<br />

class actions.<br />

5. Review of the South Africa legal situation:<br />

In this chapter, we extensively cite Dr Antonie Gildenhuys. His book titled Eiendomsreg<br />

(2 nd edition, 2001) is the standard work in South Africa, and is not<br />

available in English. This author went to great trouble to find the correct translation<br />

for the Afrikaans terminology but nevertheless included the original Afrikaans<br />

for a few key terms.<br />

The word ‘expropriation’ means ‘deprivation of property’ (ontneming van eiendom),<br />

and in expropriation legislation it normally has a wide meaning, including<br />

the creation of a new right over property (goed), like a servitude in favour of the<br />

expropriator or other legal entity (Gildenhuys: 61). S 25 of the 1996 Constitution<br />

states ‘property is not limited to land’ (Southwood: 15).<br />

The expropriator may expropriate as much land as he may need, but he may not<br />

expropriate more than what the enabling law allows. Land does not need to be a<br />

cadastral unit in order to be expropriated (Gildenhuys, 65).<br />

The expropriator does not need to take the full bundle of property rights of the<br />

expropriated land. Specific rights, like a right of way or mineral rights, may remain<br />

for the owner or third party. But the expropriator may expropriate these<br />

remaining rights at a later stage. Where the expropriator takes less than the full<br />

bundle of property rights, the expropriated person is entitled to register as a servitude<br />

in his favour the rights retained by him (67).<br />

5.1 Acts governing expropriation by <strong>Eskom</strong><br />

The expropriator may derive his authority to expropriate from the provisions of<br />

the Expropriation Act of 1975 or from the provisions of another enabling act.<br />

<strong>Eskom</strong> is enabled to expropriate land, or a right in land, in terms of ss 27(1) of<br />

the Electricity Regulation Act, no 4 of 2006. The Minister may, in terms of ss<br />

27(2), prescribe the procedure to be followed in giving effect to ss 27(1). Importantly,<br />

ss 27(3) states:<br />

“The State may exercise the powers contemplated in subsection (1) only if —<br />

(a) a licensee is unable to acquire land or a right in, over or in respect of such<br />

land by agreement with the owner, and<br />

(b) the land or any right in, over or in respect of such land is reasonably required<br />

by a licensee for facilities which will enhance the electricity infrastructure<br />

in the national interest.” (Government Gazette no 28992: 5 July<br />

2006)<br />

Section 26(1) of the Expropriation Act of 1975 provides that, should any authority<br />

to expropriate be exercised in terms of another act, the compensation due should<br />

be determined and paid, mutatis mutandis, in terms of the provisions of the Expropriation<br />

Act of 1975. This provision was only inserted in the 1992 amendment<br />

of the Expropriation Act of 1975. Thus, in 1992 South Africa had uniform norms<br />

for compensation procedures and the calculation of compensation (134). However,<br />

legislation that was promulgated after 1992 will take precedence over<br />

s 26(1) (51-2).

12<br />

The Electricity Regulation Act (referred to above) was promulgated in 2006, but<br />

at the time of writing, the Minister had not exercised his powers in terms of<br />

ss 27(2). Thus, at this time, the procedures to be followed would be in terms of<br />

the Expropriation Act of 1975.<br />

In interpreting these acts, cognisance should also be taken of the 1996 Constitution,<br />

more specifically section 25 that deals with property deprivation (see Annexure<br />

1).<br />

5.2 Constructive expropriation<br />

A deprivation (ontneming) that is not executed by means of a formal expropriation<br />

action is sometimes called constructive expropriation, a de facto expropriation,<br />

a quasi expropriation, or an effective expropriation. Examples are control<br />

measures (beheermaatreëls) like land-use planning and development controls,<br />

building regulation and environmental conservation laws (137; 22-7).<br />

5.3 Servitudes are expropriations<br />

When a public body creates a new servitude for itself over private property, it<br />

constitutes an expropriation of ‘property’ in terms of the Constitution (142). The<br />

Constitution prescribes that, in order for deprivation (ontneming) to be expropriation<br />

and, therefore, legal it:<br />

o needs to be executed by due process (algemeen geldende regsvoorskrif)<br />

o may not be arbitrary<br />

o should serve the public or be in the public interest (142)<br />

Some legislation in South Africa authorises public bodies, especially municipalities,<br />

to lay pipelines over private property. By laying the pipe, the public body effectively<br />

gets a servitude over the property concerned. This is in effect expropriation,<br />

and compensation is payable (348-9).<br />

Gildenhuys cites Judge Baker in Abdullah v City Council of Cape Town:<br />

The general rule of the common law is that for any deprivation of property (land,<br />

buildings or any other kind of property) by a local authority, compensation is to be<br />

paid to the owner, unless the enabling legislation expressly or by necessary implication<br />

takes away the common law right to compensation. (1976 (2) SA 370 (C))<br />

Gildenhuys then comments: “This finding was set aside on appeal, but in the current<br />

constitutional dispensation the verdict of Judge Baker … may prove to be<br />

correct.” (148)<br />

5.4 How compensation is calculated<br />

A property’s value is derived from a bundle of rights, and the expropriation involves<br />

the deprivation of the rights rather than the physical property. Thus, if a<br />

property with an existing servitude is expropriated, its value is less than a property<br />

unencumbered by a servitude. The compensation payable should be equal to<br />

the value of these rights in the open market, and the owner’s subjective interest<br />

in these rights is irrelevant in determining the compensation (153). Where there<br />

is no open market for these rights, the alternative valuation method might be replacement<br />

costs less depreciation (156).

13<br />

In South Africa, the courts have always accepted that the unwillingness of the<br />

owner to part with his property should play no role in the determination of the<br />

compensation amount. Neither should the sentimental value the owner attaches<br />

to his property influence the market value (246).<br />

The Expropriation Act of 1975 prescribes that compensation should not be more<br />

than the market value of the property, plus an amount to cover further actual<br />

financial loss (155; 165; 167). Also, the overriding compensation principle enshrined<br />

in the Constitution is one of justness and equity, “reflecting an equitable<br />

balance between the public interest and the interests of those affected” (165).<br />

Where a right is expropriated (excluding a registered right to minerals), the compensation<br />

norm is the financial loss suffered (ss 12(b) of the Expropriation Act of<br />

1975). Where the relevant right has a market value, the compensation could,<br />

thus, be market value.<br />

As stated earlier, claims for damage that may result from possible (future)<br />

unlawful acts of the employees or agents of the expropriator during their activities<br />

on the expropriated land cannot be included in the compensation fee. Should<br />

such damage be caused, the owner could claim damages for the delict (318).<br />

In terms of a clause in the Expropriation Act of 1975, the fact that the expropriated<br />

land has a special value for the expropriator (e.g. as an airport) cannot influence<br />

the determination of market value if it is unlikely that the expropriated<br />

land would be sold for that purpose (246).<br />

In South Africa, tax claims are not considered in computing the compensation<br />

amount (333).<br />

5.4.1 <strong>Compensation</strong> for a property with full rights<br />

<strong>Compensation</strong> for taking a property with full rights is made up of two main<br />

categories (heads of claim), and should not exceed (see Annexure 2):<br />

o The market value of the expropriated property<br />

o Further actual financial loss suffered by the owner.<br />

In addition, a solatium might also be payable in terms of s 12(2) of the Expropriation<br />

Act of 1975 (165; Annexure 2).<br />

The head for further actual financial loss can be broken down into:<br />

o Value derogation to the remainder through severance (afskeiding)<br />

o Disturbance (ontwrigting)<br />

o Injurious affection (nadelige aantasting) (155)<br />

According to Gildenhuys (324), there is no limit to the various items that could be<br />

claimed under further actual financial loss. “Financial loss” is defined as “loss of<br />

money or decrease in financial value” by WordNet, the online lexical database<br />

of English developed at Princeton University. This implies it could include capital<br />

loss.

Severance loss<br />

14<br />

Severance loss occurs when the value of the remaining (unexpropriated) portion<br />

is reduced because, for instance, its physical characteristics (like its extent) now<br />

make it less viable or even worthless.<br />

Where land is severed, it is important to avoid double counting in calculating the<br />

financial loss or value diminution inflicted on the remaining portion (338). The<br />

‘before and after’ approach (stated previously) implicitly already contains the financial<br />

loss through severance.<br />

In order to be valid, a severance claim should be:<br />

(a) a claim for a financial loss<br />

(b) caused by the taking of the expropriated portion, and<br />

(c) related to land value.<br />

No damages claim is payable if it is “remote, speculative, contingent, conjectural,<br />

peculiar to the land owner, or strictly an inconvenience” (340).<br />

Disturbance losses<br />

Gildenhuys cites David Hawkins, who compiled a list of “disturbance claims” in<br />

England, examples of which are: costs of moving stock and machinery; telephone<br />

removals; loss of goodwill; and temporary loss of profit of the business (324).<br />

Injurious affection<br />

This term describes further financial loss inflicted on the remainder through the<br />

intended use by the expropriator of the expropriated portion.<br />

A layman’s term for this might be ‘collateral damage’.<br />

An example is the construction of a sewage plant on the expropriated portion, the<br />

odours of which might affect the value of the remainder. In the recent past (albeit<br />

before the 1993 and 1996 Constitutions), the South African courts followed a<br />

narrow approach in that damages owing to the intended use of the expropriated<br />

portion were not allowed. These verdicts are in conflict with the thinking behind<br />

ss 12(5)(f) and (h)(ii) of the Expropriation Act of 1975, which do allow for compensation<br />

under certain circumstances. However, in the case of servitudes, the<br />

court did take cognisance of the probable impact the servitude would have on the<br />

servient tenement (342-3).<br />

Gildenhuys proposes that in the event of value impairment of the remaining portion<br />

of a claimant’s property caused by the intended use by the expropriator of<br />

the expropriated portion, the owner be compensated for this value derogation<br />

(343). In this author’s view, this might include visual impairment.<br />

Under the new constitutional regime, Gildenhuys looks upon such a step as a<br />

practical way to satisfy the Constitution’s provision (ss 25(3)(e)) that, in determining<br />

the compensation amount, cognisance should be taken of the “purpose of<br />

the expropriation” (342-3; 353-4). Hence he proposes that the legislator should<br />

consider this option, pointing out that in many other jurisdictions these damages<br />

are claimable (346). See also §4: Review of European countries.<br />

In terms of s 2(2) of the Expropriation Act of 1975, the expropriator may under<br />

these circumstances expropriate the remainder but he is not forced to do so (74).

15<br />

Citing Canadian, English and Dutch sources, Gildenhuys states no claim for damages<br />

caused by intended works that are not on the expropriated portion will be<br />

entertained (344).<br />

Solatium<br />

A solatium is the component of compensation that relates to non-financial loss,<br />

e.g. inconvenience, nuisance, remorse and suffering (186).<br />

In terms of the Expropriation Act of 1975, it is incumbent on the expropriator to<br />

pay a percentage allowance as a solatium, although the final amount is subject to<br />

a ceiling (188; Annexure 2). If the enabling act — the act in terms of which the<br />

compensation is calculated — does not contain compensation norms, the court<br />

has the power to award a solatium for non-financial loss. Where such an enabling<br />

act does contain compensation norms, it is a question of legal interpretation<br />

whether solatium should be paid. Given the Constitutional provision of justness<br />

and equity, Gildenhuys is of the opinion that the payment of a solatium may in<br />

such cases be obligatory (190).<br />

5.4.2 <strong>Compensation</strong> for the taking of a servitude<br />

<strong>Compensation</strong> for financial loss is subjectively determined based on the personal<br />

circumstances of the expropriated person. In contrast, the market value of<br />

the expropriated property is determined objectively, without reference to the<br />

personal circumstances of the expropriated person (319).<br />

In terms of s 12(b) of the Expropriation Act of 1975, the compensation may, in<br />

the case of a right (excluding a registered right to minerals), not exceed the financial<br />

loss suffered through the taking (see Annexure 2).<br />

An expropriator can through expropriation create a new servitude or right over<br />

land for him (70). This happens when the expropriator does not need the full use<br />

of the land for his works, but is satisfied with the lesser rights he will enjoy under<br />

the servitude. Examples are water pipelines and power lines. The compensation<br />

for such a servitude equals the financial loss suffered by the owner. In evaluating<br />

the value diminution, cognisance should be taken of the nature, extent and expected<br />

duration of the servitude. In the case of a road servitude, the courts will<br />

normally award the full market value of the affected land because there is no expectation<br />

that the land will ever again be used for anything but a road (348).<br />

As for power-line servitudes, the following factors should be considered in evaluating<br />

the compensation (349):<br />

o Extent of the land taken<br />

o The remaining use the owner has over the land taken: Should the owner not<br />

be able to use the affected land at all, the compensation might be equal to<br />

the full market value.<br />

o The duration of the servitude<br />

o The value diminution on the whole property as a result of the unsightliness of<br />

the power lines and towers<br />

o Loss of privacy<br />

o The nuisance when maintenance personnel enter the property.<br />

Claims for damage that may result from possible (future) unlawful acts of the<br />

employees or agents of the expropriator during their activities on the expropriated<br />

land cannot be included in the compensation fee. Should such damage be<br />

caused, the owner could claim damages for the delict or get an interdict (318).

16<br />

From the above, it is not clear to this author what the legislator had in mind when<br />

it prescribed different approaches to compensation for the expropriation of properties<br />

with full rights as distinct from the taking of servitudes (taking of limited<br />

rights) (cf. ss 12(a) and (b) of the Expropriation Act of 1975). In practise, the two<br />

approaches should yield the same compensation amount (assuming the same<br />

rights are expropriated), but the full-rights approach has the advantage that it<br />

concentrates the mind on the important value-detracting attributes. Nevertheless,<br />

the list of value-detracting attributes for servitudes enunciated by Gildenhuys<br />

above under §5.4.2 is very helpful.<br />

Note too that s 12 puts a maximum value on the compensation. Overcompensation<br />

is not allowed.<br />

Roads:<br />

In terms of most provincial ordinances, the declaration of a road establishes a<br />

road servitude over the land concerned — and involves no land transfer. Nevertheless,<br />

the compensation is calculated as if the land in question is expropriated<br />

(Gildenhuys, 2001:135).<br />

6. Project and operational claims<br />

Claims at <strong>Eskom</strong> are handled by <strong>Eskom</strong> Insurance Management Services at<br />

Megawatt Park. This author had an interview with Ms Beverley Jemain-Cain<br />

(Claims Manager) and Mr Krishan Chaithoo (Technical and Administration Manager:<br />

Insurance) on September 28, 2007.<br />

Their work is guided by a manual titled Claims Procedures. <strong>Eskom</strong>’s legal liabilities<br />

towards third parties are insured, and <strong>Eskom</strong> only pays claims where there<br />

was negligence that was the cause of injuries or damage to property.<br />

In ‘grey’ cases, <strong>Eskom</strong> would make an offer of settlement, based on the quantum<br />

calculated by an expert.<br />

<strong>Eskom</strong> has not done any research on their claims history and performance, so<br />

there are no statistics covering facets like the trend in claims over time, percentages<br />

of claims that succeed, the reasons for those that do not succeed, the procedures<br />

in deciding on the veracity or reasonableness of claims, and the time lag<br />

between the submission of a claim and the settling thereof. Neither do the two<br />

officials have the manpower to extract these statistics from their files. As a consequence,<br />

this author obviously cannot comment on the efficiency of the claims<br />

handling.<br />

S 23 of the Electricity Regulation Act grants <strong>Eskom</strong> powers of entry and inspection.<br />

Any person wishing to enter any premises must — “if possible” — make the<br />

necessary arrangements with the legal occupant of the premises before entering<br />

and adhere to all reasonable security measures of the occupant or owner. In<br />

terms of ss 23(3), “damage caused by such entry, inspection or removal shall be<br />

repaired or compensated for by the licensee”.<br />

In terms of ss 5(b) of the <strong>Eskom</strong> Conversion Act, 2001, <strong>Eskom</strong> “must pay compensation<br />

for any damage caused by its officers or employees in the performance<br />

of their duties upon the land.” (Government Gazette no 22545: 3 August 2001)<br />

As we saw under §1 — Public Relations, it is <strong>Eskom</strong> policy at present to pay only<br />

for claims where <strong>Eskom</strong> had been negligent. This guiding principle seems to be

17<br />

insurance-policy or common-law driven, as the above two clauses do not stipulate<br />

negligence on the part of <strong>Eskom</strong> as a precondition for paying damage claims, although<br />

one can infer from the context of the clauses that they were only meant<br />

to cover damages caused by entry.<br />

In this regard, s 26 of the Electricity Regulation Act (Annexure 3) is also of interest.<br />

It states:<br />

In any civil proceedings against a licensee arising out of damage or injury<br />

caused by induction or electrolysis (sic) or in any other manner by means of<br />

electricity generated, transmitted or distributed by a licensee, such damage or<br />

injury is deemed to have been caused by the negligence of the licensee,<br />

unless there is credible evidence to the contrary. [this author’s emphasis]<br />

This section clearly puts the onus on <strong>Eskom</strong> to prove that it has not been negligent<br />

(which, presumably, differs from the common-law situation). But nothing in<br />

this section prevents <strong>Eskom</strong> Holdings for the sake of good public relations from<br />

settling claims in cases where its infrastructure has caused damage like fires −<br />

irrespective of whether <strong>Eskom</strong> was negligent — but provided the third party was<br />

not negligent either. Another example of this kind of no-negligence claim might<br />

be maintenance helicopters that cause game to run into fences.<br />

7. Renting versus lump-sum payment<br />

It has been suggested by some owners that they would prefer an income stream<br />

in the form of rentals rather than a capital sum as compensation for the servitude.<br />

Sons sometimes complain that their father had frittered the capital sum<br />

away and they now have nothing to show for the inconvenience of the servitude.<br />

If <strong>Eskom</strong> could offer as compensation a rental stream as an alternative to a capital<br />

sum this might please these owners.<br />

Thus, the question posed by <strong>Eskom</strong> is whether it is best to acquire the necessary<br />

rights from the owner of the land through a rental agreement or through outright<br />

purchase of the rights by paying a lump sum. The latter option is the conventional<br />

way of creating a servitude in South Africa.<br />

Financially speaking, the two payment modes should in the very long run yield<br />

similar cost-return results before tax to the expropriated owner. In the shorter<br />

run, the short answer to the eternal question of buy versus rent is: it all depends<br />

on where we are in the property cycle. At times, when land’s market values rise<br />

faster than market rentals, it pays to own; and vice versa. But in the very long<br />

run they should converge.<br />

In the light of the government’s policy of land redistribution and its ambitious<br />

long-term targets in this regard, the government has become a net buyer of rural<br />

land. This means there is a giant additional buyer in the market, pushing up demand.<br />

This is so because the farmers that are bought out typically have cash in<br />

hand to buy another farm. But not only does this giant buyer push up the demand,<br />

it also takes supply off the commercial farm market. The result is steeplyrising<br />

values that have no relation to economic fundamentals. The statement<br />

about steeply-rising land values is based on anecdotal evidence, and does of<br />

course not apply to all parts of South Africa. Also, it can be assumed that certain<br />

types of agricultural land are currently rising as a consequence of the strong<br />

grain prices, but this phenomenon is purely cyclical and should not be confused<br />

with the structural shift in demand described above. In addition, it is claimed that

18<br />

the rise of the biofuels industry is internationally also creating a structural rise in<br />

demand for agricultural products and, therefore, one might assume, land.<br />

Thus, because of state intervention in the marketplace and maybe the rise of the<br />

biofuels industry, one could expect that land values will rise faster than land rent<br />

for a long time to come. This is so because one suspects that land rents will be<br />

closer aligned to economic fundamentals than capital values. After all, not many<br />

farmers will lease land at a rental that yields a negative cash flow. This analysis<br />

implies that, purely from a financial point of view, <strong>Eskom</strong> should rent the rights.<br />

But high-voltage lines and utility corridors have a long life expectancy, and who<br />

can say what South Africa, or the world, will be like in two decades? In addition,<br />

one can argue that the business of <strong>Eskom</strong> Transmission is to transmit energy –<br />

not to take a view on the property market.<br />

From <strong>Eskom</strong>’s point of view, another argument in favour of renting rather than<br />

buying is the cash-flow requirement – especially given <strong>Eskom</strong>’s heavy capital<br />

commitment in decades to come. In the greater scheme of things, this probably<br />

does not weigh heavily as an argument, but <strong>Eskom</strong>’s treasury department will be<br />

better equipped to comment on this aspect.<br />

Thus, in sum, there are two financial arguments in favour of renting.<br />

From a legal point of view, the Constitution (ss 25(b)) and the Expropriation Act<br />

(ss 12(a)) only speak of the ‘amount’ of compensation, whereas the Electricity<br />

Regulation Act is silent on this matter but does refer to the above-mentioned<br />

acts. ‘Rent’ or ‘renting’ or ‘leasing’ is not mentioned, and clearly renting as an<br />

option never occurred to the legislator. Whether, under the circumstances, renting<br />

would be legal, is a matter of interpretation, that is, whether “amount” may<br />

include “rental amount”. However, as stated above in §5.1, the Minister has not<br />

exercised his powers in terms of ss 27(2) of the Electricity Regulation Act yet,<br />

and this may allow him the opportunity to permit explicitly the possibility of renting.<br />

From the landowner’s point of view, and again, financially speaking, there should<br />

not be any difference between receiving a lump sum payment from <strong>Eskom</strong> and<br />

receiving a rental stream. The reason is, of course, that the owner could invest<br />

the lump sum in an <strong>Eskom</strong> or government bond or equity, or any other incomeproducing<br />

investment and, thereafter, receive an interest/dividend stream on this<br />

capital amount. Should <strong>Eskom</strong> go the renting route, or offer it as an alternative,<br />

the owner would similarly receive an income stream (in the form of rentals);<br />

there is no difference in principle. However, there might be psychological reasons<br />

peculiar to individuals for preferring the one mode of payment above the other.<br />

What counts heavily against a rental agreement by <strong>Eskom</strong> with the owner, is the<br />

administrative cost and hassles for <strong>Eskom</strong>. Establishing the market rentals initially<br />

would be at least as much work as determining the market value of the tobe-encumbered<br />

land. But thereafter the rentals will have to revert to market levels<br />

every few years – an expense that <strong>Eskom</strong> does not have at present. In addition,<br />

keeping track of <strong>Eskom</strong>’s thousands upon thousands of potential “landlords”<br />

and paying them on time would almost certainly become a nightmare and create<br />

much more animosity than the current situation. Subdivisions of farms after creating<br />

the servitude will complicate matters even further.<br />

As previously stated in §3.6, wayleave agreements in the United Kingdom are<br />

paid by way of rentals, but considering the nature of these agreements, there is<br />

no choice in the matter because these agreements are for a limited period. Limited-period<br />

agreements naturally also result in higher administrative costs.

19<br />

Another example of a utility that pays rental can be found in Alberta, Canada. The<br />

power transmission company AltaLink in Alberta, Canada, pays rental of up to<br />

$CAN945 per annum for a single-circuit 500-kV tower and up to $CAN1155 for a<br />

double-circuit tower (Transmission & Distribution World). This means that the extra<br />

line increases the rental by up to 22%, compared to <strong>Eskom</strong>’s current policy of<br />

adding 10% per line. (Note: The rentals quoted here have just been increased<br />

five fold. Canadian dollars are now on a par with the US dollar.)<br />

8. How to quantify loss of business<br />

We have previously seen in §4.1 that many European countries provide liberal<br />

payments to businesses affected by property acquisition. With the growing<br />

number of eco-tourist and game farms, value diminution through visual impairment<br />

especially, is becoming an issue in South Africa. The question is how to approach<br />

the value-loss calculation.<br />

The correct point of departure is to separate the business from the real estate. In<br />

practise, this is easier said than done, but professional valuers are au fait with a<br />

similar problem when valuing a hotel or guest house, or a petrol station.<br />

Agricultural land, like residential property, is typically traded on a directcomparison<br />

basis. For instance, the farm under irrigation is worth so many rands<br />

per hectare, or a modern house with three bedrooms should sell for about Rx<br />

in this suburb. The comparisons are as a rule derived from sales. Properties like<br />

these are typically not valued on an income-yield basis because the market actors<br />

use the direct-comparison method to set prices (“I hear my neighbour has<br />

just sold his farm for Rx per hectare”). Nevertheless, one could, as a check, impute<br />

the income yield after having used the comparative-sales method to value<br />

the real estate, provided one has the going market rental of course.<br />

A trap in the valuation of farms is that many sales include livestock, implements<br />

or game. These must of course be stripped out before the sale can be used as a<br />

comparison.<br />

For all practical purposes, going-concern businesses can only be valued using the<br />

income approach – by either using discounted cash flow (DCF) or capitalisation,<br />

or a combination of these. In lieu of capitalisation, one could, of course, use its<br />

inverse, viz. the price-earnings (PE) ratio (e.g. a 20% capitalisation rate equals a<br />

PE ratio of 5). These approaches are all inter-related. In valuing businesses, the<br />

direct-comparison method is generally not possible because of a lack of direct<br />

comparisons.<br />

A crucial assumption to make when valuing a business where the owner of the<br />

business also owns the real estate occupied by the business, is to assign, as an<br />

expense to the business, a notional market rental for the use of the real estate.<br />

In order to quantify the loss suffered by the business, the valuer should value the<br />

business before and after the creation of the servitude. The difference in the two<br />

scenarios will be discernible in the cash flow, and it might also show up in the<br />

capitalisation rate/ discount rate/ PE ratio. In practise it might be extremely difficult<br />

to quantify the loss.<br />

As a matter of interest, when valuing a business using the income method, the<br />

value thus calculated in this way implicitly includes ‘goodwill’.

20<br />

There are few valuers in South Africa that do both business and real estate valuations<br />

– and one tends to question the quality of either if they do both. In many<br />

instances it might be wise to appoint a team consisting of a registered Professional<br />

Valuer or Professional Associated Valuer to value the real estate and a<br />

business valuer to value the business.<br />

9. Summary of conclusions<br />

There is a dearth of research on the impact of transmission lines on agricultural<br />

property values in the international literature and there is none on the impact on<br />

tourism. The literature discussed here has shown that the major factors to be accounted<br />

for in compensating for the negative impact of transmission lines on<br />

property values are:<br />

• visual encumbrance<br />

• the marketplace fear of EMF exposure (more of an urban problem)<br />

• financial loss owing to severance, with smaller farms being more affected<br />

• damage to irrigation fields.<br />

Visual encumbrance is typically a major factor in urban, residential transmission<br />

lines, but increasingly it could be expected to become a factor affecting values of<br />

some rural properties − and businesses on such properties − in the light of the<br />

growing incidence of eco tourism and game farming.<br />

The value impact on agricultural land depends on the line design and type of<br />

farming. A transmission line could affect the operation and movement of field<br />

machinery and irrigation equipment, fieldwork patterns may need to be altered,<br />

soils are compacted, wind breaks may be removed, and weed encroachment is<br />

harder to control beneath the lines. But most crops can still be grown and livestock<br />

can graze. The height of trees and crops in the servitude are, however, controlled<br />

to prevent a fire hazard.<br />

Landowners in the <strong>Gamma</strong>-<strong>Grassridge</strong> corridor have security concerns related to<br />

access roads and fencing because of the possibility of poachers, stock theft and<br />

damage to crops and infrastructure. Claims for damage that may result from possible<br />

(future) unlawful acts of the employees or agents of the expropriator during<br />

their activities on the expropriated land cannot be included in the compensation<br />

fee. Should such damage be caused, the owner could claim damages for the<br />

delict. However, the solatium should cover the inconvenience of a possibly higher<br />

crime rate.<br />

Another novel concern is that helicopters flying over the land to do aerial maintenance<br />

of the lines make animals skittish and they can injure or kill themselves by<br />