pdf 1 - exhibitions international

pdf 1 - exhibitions international

pdf 1 - exhibitions international

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

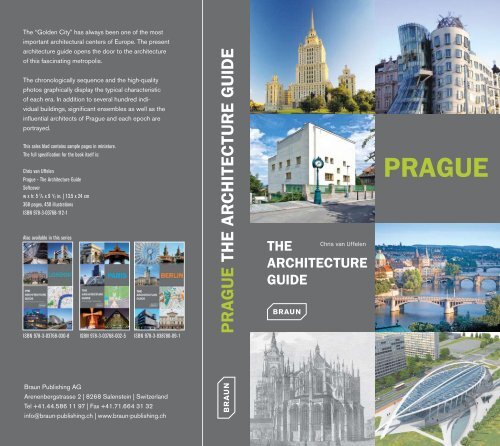

The “Golden City” has always been one of the most<br />

important architectural centers of Europe. The present<br />

architecture guide opens the door to the architecture<br />

of this fascinating metropolis.<br />

The chronologically sequence and the high-quality<br />

photos graphically display the typical characteristic<br />

of each era. In addition to several hundred individual<br />

buildings, significant ensembles as well as the<br />

influential architects of Prague and each epoch are<br />

portrayed.<br />

This sales blad contains sample pages in miniature.<br />

The full specification for the book itself is:<br />

Chris van Uffelen<br />

Prague - The Architecture Guide<br />

Softcover<br />

w x h: 5 1 /4 x 9 1 /2 in. | 13.5 x 24 cm<br />

368 pages, 450 illustrations<br />

ISBN 978-3-03768-112-1<br />

Also available in this series<br />

ISBN 978-3-03768-030-8<br />

ISBN 978-3-03768-002-5 ISBN 978-3-938780-09-1 PRAGUE THE ARCHITECTURE GUIDE<br />

Braun Publishing AG<br />

Arenenbergstrasse 2 | 8268 Salenstein | Switzerland<br />

Tel +41.44.586 11 97 | Fax +41.71.664 31 32<br />

info@braun-publishing.ch | www.braun-publishing.ch<br />

Chris van Uffelen<br />

THE<br />

ARCHITECTURE<br />

GUIDE<br />

PRAGUE

162<br />

Continuing Chaos – the Post-War Period<br />

1945–1961 (263)<br />

Today, there is still a conflicting relationship<br />

to the Berlin architecture in the postwar<br />

years. The so-called reconstruction<br />

has been rightly called a “second destruction”<br />

of the city. Yet a considerable number<br />

of these buildings have since been<br />

raised to the status of architectural monuments.<br />

From an architectural point of<br />

view, they often have little in common<br />

with each other as shown with the comparison<br />

of the “Hansa Quarter” (see no.<br />

296) cityscape, kept in the modern style,<br />

with the monumental “Stalinallee” mainline<br />

(Nos. 274, 289, 297), which speaks a<br />

traditionalist language which National<br />

Socialism also used before. Its function<br />

also does not necessarily permit inference<br />

to the developers: the Hansa Quarter<br />

as a prestigious object of West Berlin<br />

is a social residential area, Stalinallee<br />

as the “first address” of the apparently<br />

“anti-imperialistic” “workers’ and farmers’<br />

state” an imperial splendour mile.<br />

In fact, the chaos that prevailed after<br />

1945 is reflected in all these refractions.<br />

The former Reich capital was “the largest<br />

contiguous area of ruins in Europe”.<br />

Around 40 percent of the living space<br />

was destroyed, two thirds of the city centre<br />

in ruins – in particular to the south of<br />

the Memorial Church (no. 302), between<br />

Potsdamer Platz and Ostbahnhof.<br />

The first reconstruction plans were<br />

also subject to psychological paralysis.<br />

The consequence from the catastrophe of<br />

the Second World War, it was said, could<br />

only be dealt with by means of a radical<br />

break with the past. Large parts of the old<br />

city in which society’s memory had become<br />

a fixed pillar were to fall victim to<br />

this thinking.<br />

With regard to the formation of the<br />

future, there was a lack of conception,<br />

though, which is shown not least by the<br />

most radical design of these years: the<br />

collective plan, which Hans Scharoun<br />

(no. 281) introduced as the first Berlin<br />

senior government building officer after<br />

the war, did not succeed in creating a new<br />

aimed-for identity in terms of urban development.<br />

Air raids and disassembly<br />

had reduced the economic capacity of the<br />

once largest industrial metropolis of the<br />

continent by 85 percent. Of the 4.3 million<br />

Berliners (1939), hardly more than<br />

2.3 million remained.<br />

Tangibles in the west, ideology in the east: the Marshall Plan and “National Development Work”.<br />

Only the Marshall Plan introduced in<br />

1947, the goal of which was an economic<br />

and subsequent political consolidation of<br />

Western Europe, brought about change.<br />

The American aid programme totalling<br />

billions did not just revitalise the economy:<br />

with material prosperity, it was possible<br />

to remove the NS ideology as well<br />

and, at the same time, it was to serve a<br />

policy of “containment” of communist influence.<br />

In the cultural sector, too, there<br />

were efforts to contain nationalism: the<br />

influence was again the modernism (see<br />

no. 210) of the Weimar Republic which<br />

now returned to Germany as an “<strong>international</strong><br />

style” from America. The West’s<br />

desire to be new again was typified in the<br />

virginal white of the residential communities.<br />

For the Soviet occupying power, however,<br />

the communist society was the logical<br />

consequence of history. Since the<br />

sympathisers of this utopia had the power<br />

but no democratic or material basis,<br />

(the latter even being undermined by<br />

the USSR by its dismantling and clearing<br />

activities) they developed suggestive<br />

dialectics: “National in form, socialistic<br />

in content” which should enable the revolution<br />

to succeed. This meant that as<br />

part of the “national construction work”<br />

(no. 296), workers’ palaces, educational<br />

temples and countless monuments were<br />

built to promote the way of the East towards<br />

a different Germany.<br />

At least, the competition between both<br />

systems had a positive effect for Berlin:<br />

building was done with twice the energy.<br />

But at the same time the conflict of interests<br />

of the superpowers prevented a<br />

mutual policy. And what is more: in 1948,<br />

as a consequence of the Berlin blockade,<br />

there was a division of the city government.<br />

Berlin developed into an <strong>international</strong><br />

crisis hotspot. Finally, when the<br />

Berlin Wall was built in 1961, this indicated<br />

that it was not only in town planning<br />

that the ideological differences had<br />

become insurmountable. hwh<br />

163<br />

306<br />

Hans Scharoun<br />

*1893 in Bremerhaven, †1972 in Berlin (281)<br />

“...make a world out of the smallest part.”<br />

Hans Scharoun 1954<br />

In his outlook for the year 2008, the<br />

editor-in-chief of the architecture magazine,<br />

Baumeister, recently saw a few older<br />

people standing near the Philharmonic<br />

Hall. They are holding tattered slides<br />

up to the wind with the demand that the<br />

culture forum be completed in accordance<br />

to Hans Scharoun’s plans! For this<br />

fiction it needed little fantasy: there really<br />

is a Scharoun society. That it also acts<br />

as a caller in the desert fits in with an ar-<br />

Botschaft des<br />

Königreiches der Niederlande (497)<br />

Embassy of the<br />

Kingdom of the Netherlands<br />

2001<br />

Klosterstraße 49–50<br />

Office for Metropolitan Architecture (OMA),<br />

Rem Koolhaas<br />

You’d never believe the little Netherlands<br />

to be capable of so much extravagance.<br />

Off the Diplomatenviertel in the Tiergarten,<br />

the embassy of the neighbouring<br />

country resides near to the water in<br />

Rolandufer in Mitte. The building fits externally<br />

into the local block development;<br />

however, it breaks with all other conventions.<br />

A narrow strip, in which the apartments<br />

of the embassy members are located,<br />

borders on to the compartment<br />

walls of the neighbouring buildings and<br />

is separated from the actual residence<br />

through a courtyard. This transparent<br />

building part accommodates the representation<br />

and studies of the ambassador<br />

and is accessible in an unusual way. Instead<br />

of storeys, which are one on top of<br />

the other and reachable by stairways and<br />

lifts, the folded split-levels are reached<br />

1989–2005<br />

chitect who created countless exceptional<br />

buildings – but no complete artwork<br />

which would have been continued. Hans<br />

Scharoun always stood as solid as a rock.<br />

He was born in 1893 in Bremerhaven<br />

as the child of a trader who was always<br />

suspicious of the artistic tendencies of<br />

his son. He found the first encouragement<br />

of his talent from the neighbouring<br />

family of the architect Georg Hoffmeyer,<br />

whose daughter Scharoun would later<br />

marry. He completed his first plans at<br />

school: the seventeen year old boy gave<br />

the Bremen senior government building<br />

through a passageway which runs<br />

through all eight floors to the roof terraces.<br />

This serves as air circulation at the<br />

same time. The study of the Netherlands<br />

ambassador overhangs like a gazebo:<br />

with a free look across the quiet water of<br />

the River Spree.<br />

Deutsches Historisches Museum<br />

Erweiterungsbau (498)<br />

German Historical Museum<br />

Extension building<br />

2003<br />

Hinter dem Gießhaus/ Unter den Linden 2<br />

Ieoh Ming Pei<br />

The museum was so close to the heart of<br />

the former chancellor, Helmut Kohl, that<br />

he immediately commissioned the architects<br />

with the extension building himself<br />

without any prior competition. The twopart<br />

new building with its triangular<br />

ground plan, located in Am Festungsgraben,<br />

supplements the baroque arsenal<br />

(no. 16), in which the museum had<br />

been housed to date. A glazed round tower<br />

building crowns the new part of the<br />

building, which serves to develop the<br />

subsequent exhibition wing, with its entrance,<br />

rotunda and stairway and corresponds<br />

to the conventional museum typology.<br />

While the entrance area with its<br />

glassy transparency articulates an invitation<br />

to the public, the facade of the exhibition<br />

area is clad in natural stone. A<br />

tunnel combines the new building with<br />

the historical arsenal, whose beautiful<br />

ARCHITECTS OF THIS PERIOD<br />

officer “fundamental considerations for<br />

the connection of land and sea”.<br />

He was not able to complete his architecture<br />

studies, which he started in<br />

1912 at the Charlottenburg Technical College,<br />

because he was conscripted at the<br />

start of World War One. During the war,<br />

Scharoun was appointed assistant head<br />

of the building consultation office in Insterburg/East<br />

Prussia and dealt with the<br />

reconstruction of destroyed East Prussian<br />

towns. A member of the expressionistic<br />

“Gläserne Kette”, a group of artists<br />

founded by Bruno Taut from the end of<br />

the war, from 1925–1932 he was a professor<br />

at the State Academy of Art and<br />

Applied Arts in Breslau but remained focussed<br />

on Berlin, where he opened his office<br />

in 1926 and joined the architects’ association<br />

“Der Ring”, which also included<br />

Walter Gropius and Hugo Häring. With<br />

the latter, the mentor of organic building,<br />

he remained associated all his life.<br />

For the German Werkbund he made<br />

several contributions, including in 1927<br />

for the building exhibition at Stuttgart<br />

Weissenhof.<br />

In Berlin, he designed part of the<br />

Siemensstadt large residential area: individual<br />

lines stretch into the sea of trees<br />

in Jungfernheide. A typical characteristic<br />

of Scharoun’s architecture is the use of<br />

maritime motifs such as rails and portholes,<br />

like with the bachelors’ house at<br />

Kaiserdamm (no. 203). Ship quotes and<br />

city hostility are completely typical of the<br />

period here. The unique thing is reflected<br />

in the varied ground plans. They are<br />

therefore more individual than the architecture<br />

of these years, which was primarily<br />

aligned towards collective needs. In<br />

this period Scharoun found his very own<br />

theme – understanding the individual as<br />

the centre of architecture: in 1932 fourteen<br />

villas were constructed full of refractions<br />

and material variations. Only the inhabitants<br />

function as a fixed point of the<br />

buildings (see Haus Baensch no. 227).<br />

It is obvious that Scharoun’s subjectcentred<br />

architecture would have to come<br />

into conflict with the concept of art of the<br />

National Socialists. This is why he limited<br />

his activities to the construction of private<br />

detached houses during the Third<br />

Schlüter courtyard, named after the architect<br />

of the Baroque period, is covered<br />

by a glass roof again as it was before.<br />

Institut für Physik<br />

der Humboldt-Universität (499)<br />

The Institute for Physics<br />

at the Humboldt University<br />

2003<br />

Newtonstraße 15<br />

Augustin & Frank<br />

The Institut für Physik is the most prominent<br />

project of the ambitious architects<br />

Augustin und Frank. The Berlin architects,<br />

who were still really young, interpreted<br />

the building, which was almost a<br />

hectare, made up of special laboratories,<br />

lecture rooms, study rooms and offices,<br />

which the competition from 1998 demanded,<br />

as a labyrinth. However, from<br />

the outside, the building shows an elaborate<br />

transparency: the view breaks<br />

through distorted ornamental supports<br />

made from wood, bamboo plants, wicker<br />

boxes, servicing bridges and room-sized<br />

glazing, in order to remain clinging to<br />

sloping neon lights and indirectly lit<br />

coloured walls. Instinctively, the visitor<br />

remains standing, looks, is amazed and is<br />

barely cleverer than before at the end: as<br />

the actual experiments, which take place<br />

in the North of the complex, remain hidden<br />

behind frosted glass.<br />

Kommunikationszentrum<br />

der Humboldt-Universität (500)<br />

Communication Centre at the<br />

Humboldt University<br />

2003<br />

Rudower Chaussee 26<br />

Daniel Gössler<br />

Residing in the midst of the science city<br />

of Adlershof, the accommodation of the<br />

THE NEW BERLIN<br />

Reich. The festival halls, railway stations<br />

and communal palaces which Scharoun<br />

designed for himself during the Second<br />

World War, however, make it evident that<br />

his architecture must also be seen as an<br />

attempt at a new social model. But above<br />

all, they radiate an optimism which is astonishing<br />

when we consider what was<br />

happening at the time.<br />

So Scharoun became the man for Zero<br />

Hour. As the first post-war senior government<br />

building officer of Berlin, he presented<br />

in 1946 the (later mistakably<br />

titled) “Collective Plan”. The plan he elaborated<br />

with a group of young architects<br />

provided for the creation of a new town<br />

structure coming from the position of<br />

Berlin in the glacial valley between Barnim<br />

and Teltow. Only the historic Unter<br />

den Linden street of houses and individual<br />

historic buildings were to remain.<br />

The entire rest of the structural legacy<br />

was there to be used. The fundamental<br />

idea is the design of a “city band” which,<br />

running parallel to the Spree, would combine<br />

all political, economic and cultural<br />

functions. The motorways which were to<br />

pass through the cityscape were going<br />

to be created in terms of North American<br />

chess board road patterns. It was the<br />

most radical break with all townplanning<br />

tradition. Scharoun visualised<br />

individual freedom and a new beginning<br />

– and therefore fulfilled the wishes of<br />

many people, especially in the West. But<br />

ultimately his plan was so subversive<br />

that it could not be implemented.<br />

Hans Scharoun is seen as an intellectual<br />

authority for this reason alone.<br />

Already in 1946, he was no more than the<br />

town planning professor at the Berlin<br />

Technical University. He remained President<br />

of the Academy of Arts until 1968.<br />

During this period, he built a great deal,<br />

but always in solitary projects. The highlight<br />

of his achievements is the Philharmonie<br />

Hall at the Kulturforum (no. 307).<br />

This provides the best evidence of the<br />

rich collective experiences which his<br />

anthropocentric architecture enabled.<br />

hwh<br />

HU computer pool and their library<br />

grew to the Kommunikationszentrum. To<br />

house this, there was initially only the<br />

former energy central from the times of<br />

the Deutsche Versuchsanstalt für Luftfahrt<br />

(no. 230) on the plot of land. The<br />

Hamburg architect Daniel Gössler received<br />

the commission because he preserved<br />

the long scales according to a type<br />

of basilica and interlocked it closely with<br />

the new L-shaped strip made from charcoal<br />

grey zinc plates. Before the ambulatory-like<br />

diagonal wing, there is room for<br />

a light-grey auditorium cube as well as a<br />

veritable reception area. At the rear, the<br />

central square of the lowered reading<br />

room is included. In the rear part of the<br />

red-painted old building, the study areas<br />

of the library are situated today, in front,<br />

the cafeteria for the entire campus.<br />

Haus Knauthe (501)<br />

Knauthe House<br />

2000<br />

Leipziger Platz 10<br />

Axel Schultes Architekten<br />

The Haus Knauthe is the only building on<br />

Leipziger Platz which has a private owner<br />

– a fact which is reflected in the architecture.<br />

Since where with economically<br />

surface-optimised office buildings, every<br />

visitor finds it hard to catch their breath<br />

as soon as they enter, the house no. 10 is<br />

presented in a more generous flair. The<br />

entrance area receives visitors with a<br />

bistro and leads to a rear part of the building,<br />

whose glass surfaces themselves<br />

provide the daylight in the depth of the<br />

plot. Circular segment and curves are the<br />

basic forms, which have been set on all<br />

storeys against the strongly, orthogonal<br />

173<br />

307

![01 -[BE/INT-2] 2 KOL +UITGEV+ - exhibitions international](https://img.yumpu.com/19621858/1/184x260/01-be-int-2-2-kol-uitgev-exhibitions-international.jpg?quality=85)