218 Bell Museums Creator of Wildlife Dioramas - webapps8

218 Bell Museums Creator of Wildlife Dioramas - webapps8

218 Bell Museums Creator of Wildlife Dioramas - webapps8

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

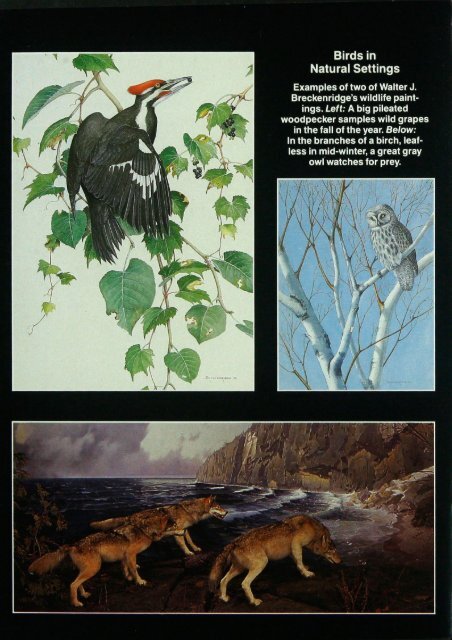

Birds in<br />

Natural Settings<br />

Examples <strong>of</strong> two <strong>of</strong> Walter J.<br />

Breckenridge's wildlife paintings.<br />

Left: A big pileated<br />

woodpecker samples wild grapes<br />

in the fall <strong>of</strong> the year. Below:<br />

In the branches <strong>of</strong> a birch, leafless<br />

in mid-winter, a great gray<br />

owl watches for prey.

For 60 years, Walter J. Breckenridge created<br />

exhibits to stimulate viewers' curiosity about<br />

the natural world. Naturalist, painter, taxidermist,<br />

he saw himself primarily as an educator<br />

4CT NOW ASK: What is our educa-<br />

X tional system doing to encourage<br />

personal, amateur scholarship in<br />

the natural history field? Does the<br />

educated citizen know he is only a cog<br />

in an ecological mechanism? That if<br />

he will work with that mechanism his<br />

mental health and his material wealth<br />

can expand indefinitely? But that if<br />

he refuses to work with it, it will ultimately<br />

grind him to dust? If education<br />

does not teach us these things,<br />

then what is education for?<br />

Author-conservationist Aldo Leopold<br />

posed these questions nearly 40<br />

years ago in A Sand County Almanac<br />

<strong>Bell</strong><br />

Museum's<br />

<strong>Creator</strong> <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Wildlife</strong><br />

<strong>Dioramas</strong><br />

Don Luce and Gayle Crampton<br />

Left: Prepared by Walter J. Breckenridge in 1940, a trio <strong>of</strong><br />

timber wolves scent a deer on the North Shore <strong>of</strong> Lake Superior<br />

near Palisade Head. Diorama is on display at <strong>Bell</strong> Museum.<br />

to help spark the environmental<br />

movement. Several decades earlier,<br />

Leopold and a few other scientists and<br />

teachers had already foreseen the<br />

negative effects <strong>of</strong> a growing population<br />

and expanding industry on the<br />

environment. By promoting the<br />

teaching <strong>of</strong> natural history, they laid<br />

the foundation for a greater understanding<br />

<strong>of</strong> our natural surroundings.<br />

One <strong>of</strong> those teachers was Walter<br />

J. Breckenridge, past director <strong>of</strong> the<br />

James Ford <strong>Bell</strong> Museum <strong>of</strong> Natural<br />

History on the University <strong>of</strong> Minnesota<br />

campus, Minneapolis. As a naturalist,<br />

ecologist, photographer, and<br />

37

<strong>Creator</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Dioramas</strong><br />

illustrator, he spent much <strong>of</strong> his career<br />

designing and creating educational<br />

experiences to help us become<br />

familiar with the natural world.<br />

Anyone who has hiked trails in our<br />

state parks lias been exposed to<br />

Breckenridges work. Many children<br />

saw their first moose or bear in a<br />

Breckenridge diorama at <strong>Bell</strong> Museum.<br />

In the museum s Touch and See<br />

Room, they stroked a wolfs pelt or<br />

touched the points on a rack <strong>of</strong> antlers.<br />

These exhibits expressed the<br />

spirit and philosophy <strong>of</strong> Walt<br />

Breckenridge.<br />

But this sophisticated level <strong>of</strong> environmental<br />

education is a relatively<br />

recent phenomenon. During Breckenridges<br />

school years, little or nothing<br />

was taught about natural history.<br />

"When I was a boy," he recalled,<br />

"no teacher ever mentioned anything<br />

that was out-<strong>of</strong>-doors. Reading, writing,<br />

and arithmetic were all they<br />

thought about. I got acquainted with<br />

outdoor things by playing hooky from<br />

school and going down to play along<br />

the creek."<br />

At the University <strong>of</strong> Iowa, Breckenridge<br />

studied zoology. Graduating<br />

in 1926, he came to UM as a preparator<br />

and taxidermist.<br />

The museum, then housed in the<br />

Zoology Building, was headed by the<br />

well-known ornithologist T. S. Roberts.<br />

Roberts had left a successful<br />

medical career 10 years earlier to<br />

pursue his interest in natural history<br />

— compiling ornithological observations,<br />

experimenting with bird photographs,<br />

and directing the construc-<br />

38<br />

tion <strong>of</strong> dioramas. Breckenridge was<br />

just the person Roberts needed.<br />

Grass Machine. The young preparator's<br />

first project was the Pipestone<br />

Prairie diorama. The prairie<br />

scene required more than 100,000<br />

blades <strong>of</strong> artificial grass. The same<br />

exhibit contained a buffalo-berry bush<br />

for which 9,000 leaves were cut with<br />

stencils and assembled by hand. Ordinarily,<br />

plants for dioramas were<br />

carefully hand-sculpted from colored<br />

waxes and molds.<br />

Faced with this daunting task,<br />

Breckenridge set about devising a new<br />

method <strong>of</strong> creating a prairie. He built<br />

a machine operated by a foot pedal<br />

which produced 2,500 blades <strong>of</strong> grass<br />

in a day. Preparators mounted each<br />

blade in a papier-mache base among<br />

dead grass to produce the lifelike<br />

plants in the prairie exhibit.<br />

Breckenridge then constructed a<br />

series <strong>of</strong> portable dioramas, one <strong>of</strong> the<br />

museum's earliest efforts to extend<br />

education beyond the walls <strong>of</strong> the<br />

University. The cases, two feet square<br />

and 10 inches deep, included scenes<br />

<strong>of</strong> birds and other animals in small<br />

slices <strong>of</strong> natural habitat.<br />

These portable dioramas circulated<br />

among schools — teachers used<br />

them in natural history lessons. In<br />

1927, 15 schools participated in the<br />

program; by the next year the number<br />

had doubled. Eventually more<br />

than 150 cases were built. Many are<br />

still used today.<br />

When the museum's new home, the<br />

<strong>Bell</strong> Museum, was completed in 1940,<br />

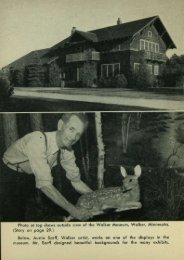

Walter J. Breckenridge in workshop at <strong>Bell</strong> Museum, Minneapolis,<br />

with animals prepared for exhibit — cormorants on rocks in 1942<br />

(top, right), and wolves in 1941 (bottom, right).

<strong>Creator</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Dioramas</strong><br />

Breckenridge supervised moving the<br />

Pipestone Prairie and six other large<br />

exhibits — no small task since the exhibits<br />

could not be moved as units. A<br />

herd <strong>of</strong> caribou in a bog, a beaver dam<br />

and lodge, a cattail marsh containing<br />

dozens <strong>of</strong> birds and nests had to be<br />

carefully taken apart, moved down the<br />

street, then reassembled.<br />

In the new museum, Breckenridge<br />

planned dioramas featuring<br />

wolves, snow geese, sandhill cranes,<br />

and more. To design and paint the<br />

background panoramas, Francis Lee<br />

Jaques came from New York where<br />

he had worked as an artist for the<br />

American Museum <strong>of</strong> Natural History.<br />

Later, John Jarosz, a remarkably<br />

talented taxidermist, joined the team.<br />

Together they created a series <strong>of</strong> exhibits<br />

for the museum that are still<br />

considered among the finest in the<br />

country.<br />

Minnesota Habitats. Breckenridge<br />

and Jaques wanted to design a<br />

series <strong>of</strong> exhibits featuring species,<br />

seasons, and habitats appropriate for<br />

Minnesota. Breckenridge said:<br />

"Our groups were planned as a trip<br />

through the various habitats in Minnesota.<br />

As you walked through the<br />

exhibit halls, you traveled all around<br />

the state, from the southeastern<br />

hardwoods, up along the Mississippi,<br />

out into the prairies in the west, and<br />

back through the pine and spruce<br />

woods in the north."<br />

In the new exhibits, Breckenridge<br />

and Jaques strove for biological accuracy<br />

and educational value — the<br />

dioramas were not to be glorified trophy<br />

cases. Each exhibit featured ecological<br />

stories that stimulated a visitor's<br />

curiosity. Snow geese fly at the<br />

peak <strong>of</strong> migration; sandhill cranes leap<br />

in a courtship dance; songbirds mob<br />

a great gray owl. Even the rocks, soil,<br />

and vegetation are realistic. The result:<br />

a set <strong>of</strong> exhibits <strong>of</strong> outstanding<br />

beauty, realism, and authenticity.<br />

Breckenridge also pioneered in<br />

nature films. At first, he was restricted<br />

to heavy, hand-cranked cameras.<br />

Nevertheless, he collected valuable<br />

footage. On one 1928 trip, he<br />

filmed nesting cranes, a ruffed grouse<br />

drumming, prairie chickens on their<br />

booming grounds, and the first sequences<br />

filmed <strong>of</strong> strutting sharptailed<br />

grouse.<br />

For years, his films were shown<br />

during the museum's popular Sunday<br />

afternoon programs. Later, Breckenridge<br />

produced films to accompany<br />

his Audubon Society lectures<br />

throughout the country. Topics ranged<br />

from the territorial behavior <strong>of</strong> birds<br />

to current conservation issues. His<br />

nature films were among the first to<br />

be aired on public television.<br />

40 Above: <strong>Wildlife</strong> artist Francis Lee Jaques painting background<br />

for wolf group diorama, June 1940. Right: Breckenridge filming<br />

winter wildlife at Lake 4, Cook County, March 1938.

<strong>Creator</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Dioramas</strong><br />

Some films he made during research<br />

or collecting trips to northern<br />

Canada and the Arctic. He was one<br />

<strong>of</strong> the first non-Eskimos since the<br />

1800s to travel on the Back River in<br />

Canada's Northwest Territory.<br />

Park Programs. In 1947, soon after<br />

becoming the museum's director,<br />

Breckenridge saw an opportunity to<br />

expand the education program to state<br />

parks. At the time, the Department<br />

<strong>of</strong> Conservation was buying land while<br />

prices were low; no funds were available<br />

for nature programs.<br />

"We figured people visiting the<br />

parks were good subjects," Breckenridge<br />

said, "because by being there<br />

they showed an interest in nature, but<br />

probably didn't know much about it."<br />

As a result, the State Park Interpretive<br />

Program was created.<br />

Breckenridge sent museum employee<br />

Donald Lewis to Itasca State<br />

Park for several summers. Lewis designed<br />

nature trails, led hiking groups,<br />

and lectured 011 the park s flora and<br />

fauna.<br />

The program grew rapidly. The first<br />

year, 4,227 visitors to Itasca took part<br />

in the program. By 1955, the figure<br />

had grown to 15,917. Naturalists<br />

joined the staffs at Gooseberry Falls,<br />

Lake Shetek, and Whitewater state<br />

parks. For several years, <strong>Bell</strong> Museum<br />

continued to pay part <strong>of</strong> their<br />

salaries. As the interpretive program<br />

grew, more parks began to participate.<br />

Today, Breckenridge's interpretive<br />

programs have expanded to nearly<br />

every state park in Minnesota.<br />

In recent photo, Breckenridge holds skin<br />

<strong>of</strong> wood duck to depict bird accurately.<br />

Since his retirement as museum<br />

director in 1969, Breckenridge has<br />

devoted his days to painting. His work<br />

has appeared in such prestigious exhibitions<br />

as "Birds in Art at the<br />

Woodson Museum in Wisconsin and<br />

at the <strong>Wildlife</strong> Heritage Art Show in<br />

Minneapolis. In recent years, he has<br />

traveled to Africa, South America, and<br />

New Zealand in search <strong>of</strong> new subject<br />

material. The artist's studio is in<br />

his home in Brooklyn Park.<br />

His artistic career started a halfcentury<br />

ago. In the early 1930s, he<br />

painted the shorebirds and woodpeckers<br />

for T. S. Roberts' The Birds<br />

<strong>of</strong> Minnesota and illustrated maga-<br />

42 THE MINNESOTA VOLUNTEER

Walter J. Breckenridge:<br />

A Life in Natural History<br />

An exhibition displaying photographs, artifacts,<br />

and paintings from Dr. Breckenridge's<br />

60-year career as an educator and<br />

interpreter <strong>of</strong> natural history now appears<br />

at the James Ford <strong>Bell</strong> Museum <strong>of</strong> Natural<br />

History, 10 Church Street SE, on the Minneapolis<br />

campus <strong>of</strong> the University <strong>of</strong> Minnesota.<br />

The exhibition will remain open until<br />

March 15,1987.<br />

-fr 1k ft<br />

zine articles on natural history with<br />

drawings and paintings.<br />

These days it's hard to coax him<br />

away from his easel. But promoter <strong>of</strong><br />

natural history that he is, Breckenridge,<br />

at age 83, still delivers lectures,<br />

writes articles, and serves on<br />

committees <strong>of</strong> The Nature Conservancy<br />

and Audubon Society.<br />

His goal, as always: to encourage<br />

interest and scholarship in the fascinating<br />

study <strong>of</strong> natural history. •<br />

Dun Luce is Assistant Curator <strong>of</strong> Exhibits,<br />

James Ford <strong>Bell</strong> Museum <strong>of</strong><br />

Natural History, Minneapolis. With<br />

Chris Brooks, he wrote about wildlife<br />

painter Francis Lee Jaques in<br />

"Master Painter <strong>of</strong> the North Country"<br />

in the November-December 1984<br />

Volunteer. Gayle Crampton is a special<br />

research assistant at the <strong>Bell</strong><br />

Museum.<br />

What Northeastern Minnesota Woodland Owners Value Most<br />

"WANTED: 10 to 49 acres wooded upland with paved road access, lake or stream<br />

access, excellent fishing, abundant wildlife, pine or oak trees. A University <strong>of</strong><br />

Minnesota study found that these property characteristics were most highly prized<br />

by buyers <strong>of</strong> woodland in 13 northeastern Minnesota counties.<br />

— University <strong>of</strong> Minnesota, Minnesota Extension Service<br />

Promise and Pro<strong>of</strong> <strong>of</strong> Changing Season<br />

"CHANGE has already set in. Slight change. That's one thing you must say for<br />

January: Its daylight hours increase rather than diminish . . . sunset now comes<br />

later. By the end <strong>of</strong> January there will be about three-quarters <strong>of</strong> an hour more<br />

daylight.<br />

"Thus do winters days change, even as molasses-slow January flows past. Already,<br />

if we watch the sunset closely, we can glimpse the end <strong>of</strong> winter. On a<br />

brittle cold day that ice-green band <strong>of</strong> light may mark the horizon . but it<br />

comes later than it did a week ago. It's still a matter <strong>of</strong> minutes, but the change<br />

has begun. That's the promise, and that's the pro<strong>of</strong>."<br />

— Editorial in The New York Times<br />

JANUARY-FEBRUARY 1987<br />

43