1836 What Were Learning About Black Bears in - webapps8

1836 What Were Learning About Black Bears in - webapps8

1836 What Were Learning About Black Bears in - webapps8

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

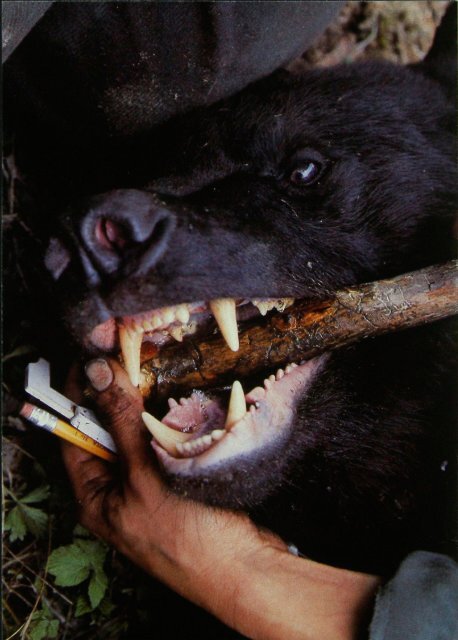

<strong>What</strong> We're <strong>Learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong><strong>About</strong> <strong>Black</strong> <strong>Bears</strong><strong>in</strong> M<strong>in</strong>nesota<strong>Bears</strong> <strong>in</strong> north-central M<strong>in</strong>nesota producemore robust cubs than those <strong>in</strong> northeasternM<strong>in</strong>nesota. Why is this so? Two DNR wildlifebiologists report on black bears they havestudied over the past three yearsKaren Noyce and Dave GarshelisPICKING OUR way through w<strong>in</strong>terbrittlealder and squeak<strong>in</strong>gsnow, we approached the den with acerta<strong>in</strong> anticipation. Twenty feetfrom the mound of dirt mark<strong>in</strong>g theden entrance, we stopped. Last yearthis bear, female #400. was alert <strong>in</strong>her den, mak<strong>in</strong>g it difficult to getclose enough to adm<strong>in</strong>ister the immobiliz<strong>in</strong>gdrug. But last year shehad year-old cubs. This Decembershe should be pregnant with a newlitter. Based on previous experiencewith pregnant females, we expectedher to be soundly asleep.We were still 10 feet away whenwe heard the telltale pop-pop of herjaws and the heavy breath<strong>in</strong>g characteristicof a not-too-pleased bear.There she was, head up, star<strong>in</strong>g usstraight <strong>in</strong> the eye, and look<strong>in</strong>g notthe least bit groggy from her eightweeks of rest. So much for ourtheory about pregnant females.It has taken three w<strong>in</strong>ters ol visit<strong>in</strong>gbear dens to learn a simple lesson:Some bears sleep soundly,whereas others are more wary <strong>in</strong>their dens, regardless of sex, age, orreproductive status. It will requiremany more years to answer importantquestions: How many cubs areborn each w<strong>in</strong>ter? How many surviveto adulthood? <strong>What</strong> factors <strong>in</strong>fluencerates of reproduction andAbove: In spotter plane, observer Karen Noyce locates radio-collared bearsby telemetry. Directional antenna is on w<strong>in</strong>g strut at right. Left: Branchholds jaw of drug-immobilized bear open. (Color photo by Tim Smalley, DNR.)37

illm

Study<strong>in</strong>g <strong>Black</strong> <strong>Bears</strong>survival? The answers will help uspractice responsible bear management<strong>in</strong> M<strong>in</strong>nesota.Fortunately, many of the <strong>in</strong>tricaciesof bear ecology <strong>in</strong> M<strong>in</strong>nesotahave already been revealed by U.S.Forest Service biologist Lynn Rogerswho studied bears for 15 years <strong>in</strong>the Superior National Forest. Rogers'data have been helpful <strong>in</strong> establish<strong>in</strong>gguidel<strong>in</strong>es for manag<strong>in</strong>g M<strong>in</strong>nesota'sbear population, but grow<strong>in</strong>ghunt<strong>in</strong>g pressure through thelate 1970s made it apparent thatmore data were needed. Also, thereis a strong likelihood that populationparameters differ widely betweenRogers' study area on the CanadianShield and other parts of the state.Thus, the Department of NaturalResources <strong>in</strong>itiated its own blackbear research project <strong>in</strong> late 1980 <strong>in</strong>north-central M<strong>in</strong>nesota.females sometimes fail to produce alitter. Instead ol hav<strong>in</strong>g cubs everyother year, it may be three or fouryears between litters. This may bedue to premature term<strong>in</strong>ation ofpregnancies when females enterdens <strong>in</strong> poor condition. In threeyears of our study, all adult femalesentered dens <strong>in</strong> relatively good conditionand produced a litter everyother year. In addition, females <strong>in</strong>north-central M<strong>in</strong>nesota are largerthan females <strong>in</strong> the northeast andproduce more robust cubs.<strong>What</strong> accounts for these differences<strong>in</strong> reproduction between thenortheastern and north-central partsof the state is not known, but we suspectit is related to differences <strong>in</strong> thequality of food resources. <strong>Bears</strong> arePursu<strong>in</strong>g Answers. With nearlythree years of field work completed,some important questions are be<strong>in</strong>ganswered, but many mysteries stillrema<strong>in</strong>.We found, for example, thatfemales <strong>in</strong> north-central M<strong>in</strong>nesotareach sexual maturity and breeddur<strong>in</strong>g June of their third or fourthyear, and occasionally when they areonly two years old. Conversely, Rogersfound that many females <strong>in</strong>northeastern M<strong>in</strong>nesota do notreach sexual maturity until five- oreven six-years of age and producetheir first litters at six and seven.Rogers also observed that adultTop, left: At bear's den, Noyce jabs bear with drug <strong>in</strong> syr<strong>in</strong>ge on end of pole.Bottom, left: Draw<strong>in</strong>g blood from femoral ve<strong>in</strong> of cub. Above: Noyce and coauthorDave Garshelis carry trap for mid-May to mid-July live-bear study.39

Study<strong>in</strong>g <strong>Black</strong> <strong>Bears</strong>How to weigh a bear? Noyce and Garshelis use a net, scale, and sturdy branchprimarily vegetarian. They live ongreens, catk<strong>in</strong>s, carrion, and <strong>in</strong>sectsuntil mid-July, then turn to wildfruits and nuts for the rema<strong>in</strong>der ofsummer and fall.In most parts of the country, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>gnortheastern M<strong>in</strong>nesota, <strong>in</strong>sectslike ants and bees make up lessthan 15 percent of the volume ofbear dropp<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>in</strong> any season. Wehave found, however, that betweenmid-June and mid-July, just beforeberries beg<strong>in</strong> to ripen, ants dom<strong>in</strong>atethe diet of bears <strong>in</strong> northcentralM<strong>in</strong>nesota, compris<strong>in</strong>g65-75 percent of scat volume.It is possible, therefore, that thisconcentrated source of prote<strong>in</strong> contributesto improved reproductivesuccess of bears <strong>in</strong> our area. In addition,oak trees, farm crops, and garbagedumps are more prevalent herethan <strong>in</strong> northeastern M<strong>in</strong>nesota, andthe longer grow<strong>in</strong>g season and richersoils of our area may provide morereliable wild fruits each year.Bear Deaths. Indirect evidencesuggests that some cubs die dur<strong>in</strong>gtheir first year. Cubs generally staywith their mother for a year and ahalf, but of 25 cubs checked <strong>in</strong> theirnatal dens, only 20 were re-observeddenn<strong>in</strong>g with their mothers the follow<strong>in</strong>gw<strong>in</strong>ter.These youngsters are too small to40 THE MINNESOTA VOLUNTEER

<strong>What</strong> do bears eat? In laboratory, Noyce exam<strong>in</strong>es scats, f<strong>in</strong>ds tree seed, right.wear radio transmitters, so the fateof the five miss<strong>in</strong>g cubs is unknown.Some may have parted companywith their mothers earlier than usualand survived on their own. However,some of the miss<strong>in</strong>g cubs mayrepresent mortalities, especiallys<strong>in</strong>ce their sibl<strong>in</strong>gs rema<strong>in</strong>ed withthe mothers.Hunt<strong>in</strong>g accounts for the greatestnumber of adult bear deaths, sohunt<strong>in</strong>g pressure must be controlled.But what constitutes anacceptable level of hunt<strong>in</strong>g mortality?Theoretically, the harvestshould equal the number of newcubs born each year, m<strong>in</strong>us thenumber of bears dy<strong>in</strong>g from causesother than hunt<strong>in</strong>g. Data from ourtelemetry study and from Rogers <strong>in</strong>dicatethat hunt<strong>in</strong>g mortality shouldconstitute roughly 10-15 percent ofthe total bear population. Unfortunately,there is no easy way to estimatethe population of bears that <strong>in</strong>habitdense forests.One way to estimate populationsize is to catch and radio-collar allbears <strong>in</strong> a given area. The bear densityobserved <strong>in</strong> that area can thenbe extrapolated to other areas ofsimilar habitat. Rogers collared everybear <strong>in</strong> his study area <strong>in</strong> northeasternM<strong>in</strong>nesota, and we havenearly accomplished this <strong>in</strong> our area.Surpris<strong>in</strong>gly, bear-density estimatesMARCH-APRIL 1984 41

Study<strong>in</strong>g <strong>Black</strong> <strong>Bears</strong>Top: Ken Kerr, DNR medical technologist,measures electrolytes <strong>in</strong> bear's blood.Bottom: Computer analyzes study data.cooperate by submitt<strong>in</strong>g teetli fromtheir bears which we use to determ<strong>in</strong>ethe animal's age. They alsoanswer survey questions about location.duration, and success of theirhunt so we can quantify hunt<strong>in</strong>geffort.At present, our best estimate derivedfrom the computer model is apopulation of 6,000-7,000 bears <strong>in</strong>M<strong>in</strong>nesota. Unfortunately, the modelmakes a lot of assumptions aboutbears. Our estimates may change asfurther research shows us that someassumptions are <strong>in</strong>correct.for these two areas are nearlyequivalent: one bear per two orthree square miles.We also are us<strong>in</strong>g a more theoreticalapproach to estimate the state'sbear population. Male bears, especiallyyoung males, are more vulnerablethan females to hunt<strong>in</strong>g. A computerprogram exam<strong>in</strong>es the maleto-femaleratio <strong>in</strong> each age-class ofbears <strong>in</strong> the harvest. These ratios,when compared to a measure ofhunt<strong>in</strong>g pressure — for example,hunter-days afield — exerted on thepopulation over several years, enablethe program to calculate thepercentage of the population representedby the legal harvest. HuntersWhy Nuisance <strong>Bears</strong>? The shoot<strong>in</strong>gof nuisance animals is the secondmost important cause of bear mortality<strong>in</strong> M<strong>in</strong>nesota. A nuisance bearmay be anyth<strong>in</strong>g from an <strong>in</strong>dividualthat wanders <strong>in</strong>to town and raids afew garbage cans to one that causesconsiderable damage to crops, beehives,livestock, or other property.Nuisance bears are reported to localDNB Conservation Officers who usetheir discretion <strong>in</strong> handl<strong>in</strong>g eachcase. Some of these bears are killed,some are transported to other areas,and others leave on their own.Every year, Conservation Officerssend us a report summariz<strong>in</strong>g eachcompla<strong>in</strong>t they <strong>in</strong>vestigate. In thisway, we monitor fluctuations <strong>in</strong> nuisance-bearactivity across the state.Numbers of compla<strong>in</strong>ts vary42 THE MINNESOTA VOLUNTEER

greatly from year to year, more thanwe can attribute to changes <strong>in</strong> thenumber of bears. Also, the peakperiod for nuisance activity differsamong years. For example, nuisanceactivity was high both <strong>in</strong> 1981 and1983. Most compla<strong>in</strong>ts <strong>in</strong> 1981 wereregistered <strong>in</strong> August dur<strong>in</strong>g astatewide failure of many wild fruits.In 1983, most compla<strong>in</strong>ts occurred<strong>in</strong> June and early July, but taperedoff as a good crop of fruits ripened <strong>in</strong>August. This suggests that availabilityof natural food largely <strong>in</strong>fluencesnuisance behavior.The old adage proves true: Themore we learn, the more we need tolearn. It may seem a small lessonthat <strong>in</strong>dividual bears vary <strong>in</strong> theirbehavior, but the ramifications ofthis loom large. If all bears were thesame, our task would be easy. As itis, the <strong>in</strong>dividuality of these animalsadds enormously to the time andeffort necessary to uncover each axiomof bear biology. As scientistspractic<strong>in</strong>g wildlife management, wesearch for commonalities, but as humanswe get secret enjoyment fromthe bear's unpredictability.When the time comes to countcubs <strong>in</strong> dens this spr<strong>in</strong>g, female#400 will undoubtedly make thatpo<strong>in</strong>t clear once aga<strong>in</strong>. •Karen Noyce and Dave Garshelisare wildlife biologists specializ<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>black bear research at the DNRForest Wildlife Population and ResearchGroup, Grand Rapids.&-frHow Many Turkey Hunters Are SuccessfulPDESPITE SNOW, cold, ra<strong>in</strong>, and strong w<strong>in</strong>ds dur<strong>in</strong>g most of last year s 25-daylongspr<strong>in</strong>g turkey hunt <strong>in</strong> M<strong>in</strong>nesota, more birds were harvested than <strong>in</strong> the1982 season. By May 8, the day the hunt ended, DNR check<strong>in</strong>g stations recorded116 birds — a n<strong>in</strong>e percent <strong>in</strong>crease over 1982. <strong>About</strong> 1.700 huntersparticipated <strong>in</strong> the season; one hunter <strong>in</strong> 14 bagged a turkey.— DNR News ServiceCost of Water to Produce Food We Eat Each Year: $3,000"THE CURRENT, s<strong>in</strong>gle, greatest consumption of water <strong>in</strong> the United States is foragriculture and the irrigation of crops for the production of food. Based upon theamount of water needed to grow the food products which we typically consume. . . the follow<strong>in</strong>g prices would have to be added to cover the cost of the waterused <strong>in</strong> production. For a hamburger, French fries, and cola, $3. For a loaf ofbread, 60 cents. For a pound of beef, $8. For a dozen eggs, 96 cents. For abushel of corn, $10. At a price of two cents for every 10 gallons, it would cost$3,000 a year for the water to produce the food for just one person <strong>in</strong> the United— Journal of FreshwaterMARCH-APRIL 1984 43