1373 Smokechasers from Minnesota Monthly - webapps8

1373 Smokechasers from Minnesota Monthly - webapps8

1373 Smokechasers from Minnesota Monthly - webapps8

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

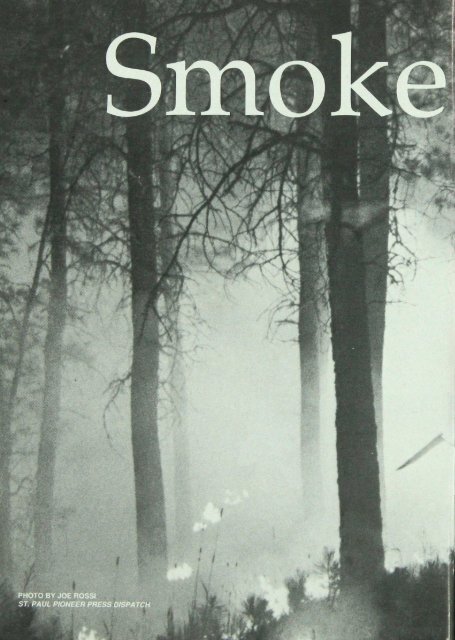

Smoke

Free-lance firefightershelp the DNR battleforest firesPeter M. Leschak* ^ ^^ A was armedfor the fear anddestruction, but IV* didn't expect the beauty.We were Department of Natural Resources "smokechasers,"racing north on <strong>Minnesota</strong> Highway 73, closing

<strong>Smokechasers</strong>in on a forest fire. It was my 22nd fire in 19 days, but it would be thefirst one I'd fought after sunset.In a few moments we saw it. A curling arm of smoke was risinginto the yellow-banded sky. It was tinged with the glow of twilight,a luminous auburn cloud swelling out of the trees. Just below thejagged silhouettes of the spruce and balsams we sawflashes of orange. Suddenly one of the trees in the foregroundburst into a dazzling fountain of sparks thatdanced and twisted upward, propelled by a column offlame.It was a terrible, pulse-quickening beauty. And overit all—a lonely star in the indigo sky of falling night—was Aero-2, the spotter plane. The pilot had switchedon his landing light, and it shone like a beacon over the storm. It wasas if Venus had decided to swirl, to approach the earth and orbit theblaze as our guardian angel.She spoke: "Is that you coming <strong>from</strong> the south?""Affirmative, Aero-2. We have the fire.""Ten-four. Be careful."We wheeled off the highway, bouncing down a narrow dirt road,and in a moment we were on the fireground. A U.S. Forest Servicecrew and a local volunteer fire department had just arrived, and wewere quickly enmeshed in the confusion of initial attack. But this farinto fire season, chaos was a familiar, if not comfortable, acquaintance.I felt the pleasing rush of adrenaline."Suddenly one ofthe trees burst intoa dazzling fountainof sparks."Combat. Firefighting is a form of combat, and the DNR smokechasersare the infantry in the annual war against wildfire. After thesnow melts, before spring rains turn the fields and forests green, northern<strong>Minnesota</strong> is a dry expanse of potential fuel. The battles generallybegin around the first week in April and blaze on into mid-May.Carelessness, arson, or lightning can ignite dozens of fires each day.The DNR's regular staff can't begin to handle the emergency load, soevery year the state recruits hundreds of volunteers. Experience ispreferred but not necessary.Assembling the smokechaser force is an interesting problem. Fire-Peter M. Leschak, Side Lake, is the author of Letters From Side Lake. Thisarticle was reprinted <strong>from</strong> the April 1989 issue of <strong>Minnesota</strong> <strong>Monthly</strong>.48 THE MINNESOTA VOLUNTEER

fighters need to be hard workers who are available to put in long,odd hours for three to six weeks. They should be responsible, trainablepeople—physically fit, willing to take initiative, and possessedof basic mechanical skills and a certain amount of bravery. In short,they're the kind of people who tend to be gainfully and inextricablyspliced into the economy and thus unavailable for short-notice, lowpaying,dangerous work. So how does the DNR find enough smokechasers?Mostly, it's a chancy, potluck operation, driven by word ofmouth and energized by public awareness of the need. It's nebulous,haphazard, and it seems to work.Among the two dozen smokechasers I served with in the spring of1988 (average age: 31), two had just mustered out of the military andhad no immediate plans. One was a farmer. One was a teenagerfresh out of high school, another had recently quit a job, and anotherhad been laid off. One was a moonlighter trying to juggle smokechasingand his regular job, and one a college student attempting todo the same with classes and exams. But the majority were freelancers—inveterateseekers of temporary jobs and contracts. Somedid construction work—roofing, painting, concrete. Some planted ortrimmed trees or did part-time logging. Others opted for seasonalmaintenance work such as mowing and snow removal. As a freelancewriter, I fit right in.A smokechaser is paid $8.36 per hour, straight time. There's noovertime pay unless you surpass 106 hours in a two-week payrollperiod. When you're on standby at the station, doing light work(raking, washing vehicles, sweeping floors), it seems like good money.When you've got a 50-pound pump can on your back and you'rehumping through the woods on the flank of a hot blaze, scaling ravines,slogging through swamps, eating smoke, it seems a tad low.Fire Boss. On the first day of the 1988 fire season, my crew wasdispatched to a fire that the Aero-2 spotter plane reported to be threateningbuildings. Our smokechaser contingent was organized intofour three-man crews (there are some female smokechasers, but noneserved on the crews I worked with). Each crew rode a pickup truckequipped with hand tools, pump cans, and a pump and hose reelhooked up to a 100- to 200-gallon water tank. The other three unitswere already committed to other fires, so as we sped out of the stationwe realized there was no backup.JANIUARY-FEBRUARY 1990 51

<strong>Smokechasers</strong>My firefighting education had reached the point where I was trustedwith a portable radio, the symbol and tool of command. For the firsttime I was to be the "fire boss." Tradition demands that the bossdrive the truck, but Darin had a keener knowledge of the territory, soI asked him to be the pilot while I concentrated on being nervous.This is where the "smokechasing" comes in. The"I was spraying<strong>from</strong> the hip as Ireached the seat ofthe fire."airborne spotter sees smoke and calls in a location.Each truck carries a plat book, and as we head in thegeneral direction of the fire we pore over the maps todetermine the best route. But a site reckoned <strong>from</strong>the air may or may not be precise, so we scan the horizonfor smoke. By the time we reach the neighborhood,any fire worthy of our attention is kicking upan obvious column, and we "chase" it, homing in like bugs to a lamp.This one was easy. Aero-2 not only gave us a clear description, butnarrowed it down to a specific section of a specific road. The smokewas readily visible, and Darin turned into a private drive that leddirectly to the fire.Horses in the Barn. Four-foot flames had just burst out of the woodsand were licking the side of a garage. I leapt out of the truck, grabbedthe hose, and sprinted for the garage. Karl started the pump, and Iwas spraying <strong>from</strong> the hip as I reached the seat of the fire. In a momentI'd twisted the nozzle into semifog mode and knocked down a 20-foot length of flames. I doused the wall of the garage, then droppedthe nozzle and grabbed my radio. Darin and Karl had donned pumpcans and were hurrying to the far side of the house, where the headof the fire was eating up a field of tall grass and brush and sweepingtoward a pine plantation only a few minutes away. There was anotherhomestead beyond the pines, and three "civilians" were outthere swatting at the fire with shovels.I was about to report to base and request a helicopter when ZeroPapa Alpha, a Hughes 500, banked in <strong>from</strong> the south. The chopperpilot had been working a fire a few miles away, and base had toldhim to take a swing over us. I tried to raise him but got no reply. Basebroke in and reminded me to switch to the tactical frequency. In myexcitement I'd forgotten that on the fireground we were supposed togo to a "working" frequency to avoid cluttering the main channel.But the pilot was already landing, easing into a field on the south50 THE MINNESOTA VOLUNTEER

flank of the fire, so I grabbed a pump can and joined the fray.The first time you use a pump can in earnest, you are surprised bytwo things: how much fire you can snuff and what arduous work itis. The can holds five gallons of water, which you eject by pumpingthe slide on a two-handled "trombone" hooked to the can via a shortrubber hose. Essentially, it's a large, sturdy squirt gun. During aninitial attack, you pump as fast as you can while walking or trottingthrough forest or field in the teeth of smoke and flame. The most efficientway to use a pump can is to wade right in, spraying parallel tothe fireline so that all of the water strikes flame. If possible, one firefighterhurries along the line hitting the big chunks while a crewmatefollows behind, mopping up.I didn't have that luxury as I fought toward the pine plantation.We were spread thin, and I enlisted one of the civilians to back me upwith his shovel. We hit the fire hard, but it kept springing up <strong>from</strong>beneath the matted grass, and we'd have to backtrack and nail it again.The man pointed to a barn about 400 yards ahead of the fire."I've got horses in there," he gasped. "Should I move them?"The question caught me off guard. In the heat of the struggle I'dforgotten I was an authority figure, complete with fire-resistant Nomexuniform and radio. My first impulse was to say, "Damned if I know!"But when you're packing a radio, such candor is forbidden. The manhad posed a legitimate question, and it was my job to ponder it—fora second. While still pumping away, I noted the distance to the barn,the force of the wind, the condition of the fuels, and the fact that threesmokechasers had just piled out of the helicopter and were hookingup a 100-gallon bucket."No," I replied, "they'll be fine. We're about to get a handle on thisthing." I sounded glib and sure, or at least I tried to. In any case, theman didn't run for the barn.In a few minutes the helicopter was ready. It roared off with itsbucket dangling, and the "helitac" foreman and his two firefighterswere deploying along the line. Each of them carried a bladder bag—a rubber sack with hose and trombone that holds as much water as apump can but is easier to carry in the tight confines of a small aircraft.Helitac. In northern <strong>Minnesota</strong>, helicopters are used as instrumentsof initial attack. There's almost always a body of water near a fire,and in minutes (or even seconds) an experienced pilot can dip a bucketJANIUARY-FEBRUARY 1990 51

<strong>Smokechasers</strong>"His son had inadvertentlyignitedthe blaze whileburning trash."into a lake or pond and return with 800 pounds of water—the equivalentof 20 pump cans. It's like having a dozen extra firefighters.Papa Alpha returned shortly, and his first bucket-drop hit the burgeoningline of fire that was singeing the plantation. It looked as iftwo more buckets would quench it. Before the chopper returned witha second load, the helitac crew had helped snuff therest of the line, and I hurried off to grab a fresh pumpcan and head for the north flank of the blaze.The flames had entered a stand of hardwoods andslowed down considerably, since there was less fueland wind. The ground was also swampy, and I hadthe comic experience of fighting a fire while wading inankle-deep water. The flames were consuming the drygrass and brush above the waterline, creeping toward a dense standof balsam fir. I radioed the helitac foreman and requested a drop atthe earliest opportunity. Papa Alpha zoomed over two minutes later,his bucket whipping just above the treetops as he laid down a swathof water that wiped out 30 feet of flame. Two more passes and it wasall over but the mop-up. Karl joined me, and we cleaned up the northflank with pump cans. The helicopter landed, and in five minutesthe crew had stowed the bucket, strapped themselves in, and liftedoff for new adventures.The fire had burned 5 to 10 acres of mostly grass and brush, but inthe forested area it had left behind a half-dozen smoldering "snags"—standing dead trees that were now burning inside and high up andwould have to be felled. I radioed base for a chainsaw, and while wewaited I chatted with the property owner. He and his son had helpedbattle the fire, but he was embarrassed. His son had inadvertentlyignited the blaze while burning trash. There had been a similar mishapthe year before. The man knew he'd be charged for suppressioncosts—that is, the smokechasers' wages, mileage on our truck, andthe cost of the helicopter. Fortunately for him, the operation had beenbrief, and it appeared that he'd get off with a bill of $250 or so. Thoughit costs $300 per hour, the chopper probably saves people money inthe long run. The bucket-drops shorten the life of a fire dramatically.We returned to base less than two hours after we'd left, having saveda garage (with an $8,000 boat inside) and most of a small pine plantation.We felt great—satisfied and a little high. But not all of our battleswere so quick and clean. •52 THE MINNESOTA VOLUNTEER