Journal of Film Preservation N° 56 - FIAF

Journal of Film Preservation N° 56 - FIAF

Journal of Film Preservation N° 56 - FIAF

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Film</strong> <strong>Preservation</strong><br />

Revue de la Fédération Internationale des Archives du <strong>Film</strong> <strong>56</strong> • June / juin 1998<br />

Published by the International Federation <strong>of</strong> <strong>Film</strong> Archives

<strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Film</strong> <strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>N°</strong> <strong>56</strong><br />

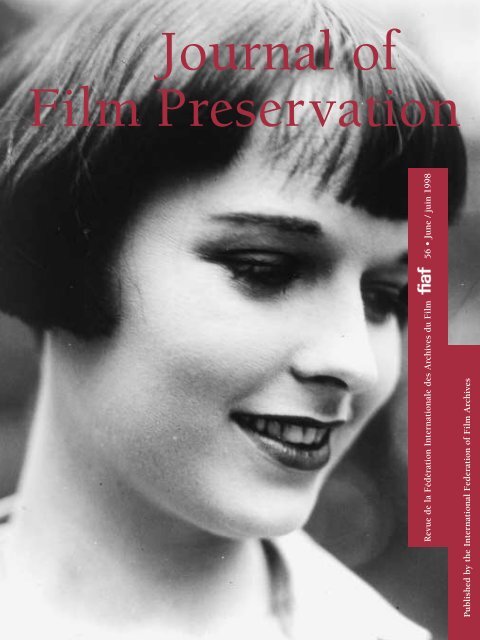

Louise Brooks by Hans Casparius (SDK)<br />

News from the Affiliates / Nouvelles des Affiliés<br />

2 Amsterdam<br />

4 Jerusalem<br />

5 Mexico<br />

<strong>FIAF</strong><br />

7 The Administration <strong>of</strong> the Federation: some preliminary<br />

results from an analysis <strong>of</strong> past Executive Committees <strong>of</strong> <strong>FIAF</strong><br />

by Roger Smither<br />

Historical Column / Chronique historique<br />

18 80 Days: Discoveries from a Unique Collection<br />

by Brian Taves<br />

23 Where do we go from here?<br />

by Martin Koerber<br />

27 Restoration(s) / Restauration(s)<br />

28 On « Wild » <strong>Film</strong> Restoration, or Running a Minor<br />

Cinematheque<br />

by Enno Patalas<br />

39 Miracolo di Bologna<br />

by Peter von Bagh<br />

New Restorations Projects / Nouveaux projets de restauration<br />

44 Le Service des Archives du <strong>Film</strong> du CNC (Bois d’Arcy)<br />

Open Forum<br />

50 Out <strong>of</strong> the Attic : Archiving Amateur <strong>Film</strong><br />

by Jan-Christopher Horak<br />

54 There Was this film about ... The Case for the Shotlist<br />

by Olwen Terris

In Memoriam<br />

58 Ricardo Muñoz Suay (1917-1997)<br />

by Nieves López-Menchero<br />

June / juin 1998<br />

International Groupings / Groupements internationaux<br />

61 The Council <strong>of</strong> North-American <strong>Film</strong> Archives - CNAFA<br />

by Iván Trujillo Bolio<br />

62 Third Nordic <strong>Film</strong> Archives Meeting<br />

by Vigdis Lian<br />

63 SEAPAVAA - Two Years on<br />

by Ray Edmondson<br />

66 CLAIM Meeting held in Prague<br />

by Iván Trujillo Bolio<br />

66 Association des Cinémathèques Européennes - ACE<br />

by José Manuel Costa<br />

Publications<br />

69 Uncharted territory : Essays on early nonfiction film<br />

69 Pierre Hébert, l’homme animé<br />

70 De la figure au musée imaginaire<br />

72 AFI publishes catalog on Ethnic-american films<br />

72 Jubilee Book. Essays on Amateur <strong>Film</strong>/Rencontres autour des<br />

Inédits<br />

73 Footage : The Worldwide Moving Image Sourcebook<br />

74 La Crise des Cinémathèques... et du Monde<br />

<strong>FIAF</strong> Bookshop / Librairie <strong>FIAF</strong><br />

<strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Film</strong> <strong>Preservation</strong><br />

Bisannuel / Biannual<br />

ISSN 1017-1126<br />

Copyright <strong>FIAF</strong> 1998<br />

Comité de Rédaction<br />

Editorial Board<br />

Chief Editor/Editeur en Chef<br />

Robert Daudelin<br />

Members / Membres<br />

Mary Lea Bandy<br />

Paolo Cherchi Usai<br />

Gian Luca Farinelli<br />

Michael Friend<br />

Steven Higgins<br />

Steven Ricci<br />

Hillel Tryster<br />

Résumés / Summaries<br />

Eileen Bowser<br />

Christian Dimitriu<br />

Editorial Assistant<br />

Sophie Quinet<br />

Graphisme / Design<br />

Meredith Spangenberg<br />

Impression / Printing<br />

Poot<br />

Bruxelles / Brussels<br />

Editeur/ Publisher<br />

Christian Dimitriu<br />

Fédération Internationale des<br />

Archives du <strong>Film</strong> - <strong>FIAF</strong><br />

Rue Defacqz 1<br />

1000 Bruxelles / Brussels<br />

Belgique / Belgium<br />

Tel : (32-2) 538 30 65<br />

Fax : (32-2) 534 47 74<br />

E-mail : fiaf@skypro.be

Amsterdam<br />

The Nederlands <strong>Film</strong>museum<br />

Le Regard du spectateur<br />

Le Nederlands <strong>Film</strong>museum organise,<br />

du 22 au 25 juillet 1998 son troisième<br />

Atelier d’Amsterdam. Celui-ci, intitulé<br />

Le regard du spectateur aura pour but<br />

l’étude de films des collections du NFM<br />

portant sur des sociétés non occidentales<br />

et non urbaines réalisés par des<br />

cinéastes occidentaux pour des publics<br />

occidentaux. L’intérêt de ces films,<br />

conçus comme produits de<br />

divertissement, réside principalement<br />

dans le fait que, plutôt que les sociétés<br />

décrites, ils illustrent la manière de voir<br />

de ces réalisateurs et de ces publics et<br />

documentent les sentiments, les<br />

fantaisies et les idées (préconçues) sur le<br />

sujet filmé.<br />

Une question importante à laquelle<br />

l’Atelier tâchera de répondre est : « En<br />

tant qu’archivistes, historiens, cinéastes,<br />

qu’est ce que nous faisons avec ce<br />

matériel aujourd’hui ? »<br />

News from the Affiliates /<br />

Nouvelles des Affiliés<br />

3rd Amsterdam Workshop: ‘The eye <strong>of</strong> the beholder’<br />

Nico de Klerk<br />

From 22 through 25 July 1998 the Nederlands <strong>Film</strong>museum will organize<br />

its 3rd Amsterdam Workshop. This workshop, called ‘The eye <strong>of</strong> the<br />

beholder’, will focus largely on documentary material from the NFM film<br />

collection about non-western (and non-urban) peoples and cultures<br />

made by western filmmakers for western film audiences. Furthermore,<br />

these films were for the most part shown in western commercial cinemas,<br />

that is to say, they were largely made to entertain. The workshop,<br />

then, is not concerned with (academic) ethnographic filmmaking; accuracy<br />

<strong>of</strong> representation is not a consideration in this project. The interest<br />

<strong>of</strong> these films lies primarily in the way they document their makers’ and<br />

audiences’, in short their beholders’ ways <strong>of</strong> seeing, their feelings and<br />

fantasies and (preconceived) notions about the subjects filmed.<br />

This kind <strong>of</strong> film material merits special attention. For one thing, since<br />

the post-war years, more particularly since the era <strong>of</strong> decolonization, it<br />

has fallen into disrepute. That hasn’t made the films go away. On the<br />

contrary, many archives <strong>of</strong> former colonial empires are full <strong>of</strong> them. So<br />

one basic question the workshop will address is, ‘What do we - film<br />

archivists, film historians, filmmakers and others with a pr<strong>of</strong>essional<br />

interest in these films - do with it today?<br />

Secondly, for more than half a century the cinema provided the public<br />

with the most vivid image <strong>of</strong> the non-western (and non-urban) world.<br />

However, one cannot help observing that during this period commercial<br />

filmmaking especially appears to have largely and blatantly refused to<br />

express or give an understanding <strong>of</strong> the experiences <strong>of</strong> the people filmed.<br />

The films sometimes show sympathy, but empathy is conspicuously<br />

absent. And although with this we do not mean to sneak the concept <strong>of</strong><br />

accuracy back in again, as a norm or standard to judge the films against,<br />

still we cannot simply eliminate our knowledge <strong>of</strong> twentieth-century<br />

colonial history and look at this material in a detached way, with no<br />

regard for social and political events, then as well as now. In a way,<br />

then, it seems as if this material constitutes some kind <strong>of</strong> missed opportunity.<br />

With hindsight, this may well be part <strong>of</strong> a sadness one feels when<br />

watching these films.<br />

The film material eligible for this project was shot between the beginning<br />

<strong>of</strong> the century and ca. 1960. The workshop’s delineation <strong>of</strong> these sixty<br />

years is content—motivated and based on viewings <strong>of</strong> the available<br />

material at the NFM. In view <strong>of</strong> the fact that the selection this topic<br />

makes from the collection is concerned with matters <strong>of</strong> imaging - and<br />

imagination - in a specific historical period (the last decades <strong>of</strong> colonialism<br />

and the era <strong>of</strong> decolonization), contextual considerations were put<br />

before purely cinematic ones in keeping the overwhelming amount <strong>of</strong><br />

material manageable.<br />

The most significant context, then, for much <strong>of</strong> this material, was formed<br />

colonialism (and de-colonization). Nevertheless, it would be a mistake to<br />

simply, or exclusively, label this material as colonialist (or racist). For<br />

2 <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Film</strong> <strong>Preservation</strong> / <strong>56</strong> / 1998

present-day audiences these terms may function as formulas to allay<br />

post-colonial feelings <strong>of</strong> guilt, to which this material doubtlessly appeals.<br />

But such a response tells more about these audiences than about the<br />

films, as such labels <strong>of</strong>ten completely ignore that the films in fact show<br />

more than just colonialism - or what we think colonialism is. The films<br />

may not have given a proper image <strong>of</strong>, or even a voice to, the people<br />

filmed, but apart from documentating the fascinations and blind spots <strong>of</strong><br />

their beholders, they also retain traces <strong>of</strong> the situations, the encounters<br />

in which they came about. These labels, in other words, don’t do justice<br />

to the specific character <strong>of</strong> cinematic records. In contrast to, for instance,<br />

written sources, filmed reports presuppose a direct contact with those<br />

who are being filmed. For that reason, ‘colonialism’ or ‘imperialism’ are<br />

awkward, abstract terms for these films, shorthand for a complex <strong>of</strong> factors,<br />

forces and influences. While together these make up social, political,<br />

and economic reality, this reality, it is assumed, only partly<br />

determines the shape <strong>of</strong> actual contacts, both filmed and unfilmed.<br />

The Amsterdam Workshop, an initiative <strong>of</strong> the Research Department <strong>of</strong><br />

the Nederlands <strong>Film</strong>museum, is a festival-cum-conference in which, on<br />

the basis <strong>of</strong> screenings <strong>of</strong> a selection <strong>of</strong> films from NFM’s collection, film<br />

historical and -archival topics are addressed that have not been studied<br />

closely or programmed extensively. What we want to realize with this<br />

workshop is a re-animation, re-vision, and re-evaluation <strong>of</strong> this so-called<br />

colonial material in an international context. With ‘The eye <strong>of</strong> the<br />

beholder’ we want to contribute to the international ‘research agenda’<br />

and bring together experts who have either been working in this area or<br />

those whose views we think are worthwhile for discussing this topic. It<br />

is our assumption, moreover, that as an archival source film has neither<br />

been mined adequately nor exhaustively. The workshop, therefore, is<br />

also an opportunity to stress the importance <strong>of</strong> film archives in general<br />

for work in this area, not only for historians, but also for anthropologists,<br />

social historians, etc.<br />

Secondly, we want to make this material known and visible again. We<br />

want to look for formats in which this material could be screened and<br />

programmed in ways that are acceptable to present-day audiences, or<br />

even challenging. After all, television documentaries and news programmes<br />

especially have contributed to an hesitation, to say the least, in<br />

showing this material.<br />

Participation in the Amsterdam Workshop is exclusively by invitation.<br />

The NFM prefers to keep the number <strong>of</strong> participants restricted in order<br />

to guarantee fruitful discussion. However, in order to ensure ‘virtual participation’<br />

by a larger audience, the discussions will be taped, edited and<br />

published on the Internet soon after the Workshop.<br />

3 <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Film</strong> <strong>Preservation</strong> / <strong>56</strong> / 1998<br />

L’Atelier d’Amsterdam proposera des<br />

projections et des conférences qui, autour<br />

d’une sélection de films du NFM, abordera<br />

ont des sujets d’histoire et d’archivistique qui<br />

n’ont pas été étudiés ou programmés jusque<br />

là. L’Atelier se propose une re-animation, une<br />

re-vision et une re-évaluation de ce matériel<br />

que l’on serait tenté de qualifier de colonial<br />

dans le contexte international habituel.<br />

La participation à l’Atelier est exclusivement<br />

sur invitation. Pour permettre une participation<br />

« virtuelle » plus large, les discussions<br />

seront enregistrées, éditées et publiées sur<br />

Internet.<br />

La mirada del espectador<br />

El Nederlands <strong>Film</strong>museum organiza, del 22<br />

al 25 de julio de 1998 su tercer Taller de<br />

Amsterdam. Intitulado La Mirada del<br />

espectador, éste tendra por objeto el estudio<br />

de películas de la colección del NFM sobre<br />

sociedades no occidentales y no urbanas<br />

realizadas por directores occidentales para<br />

públicos occidentales. El interés de estos<br />

filmes, concebidos como meros productos de<br />

diversión, reside sobre todo en el hecho que<br />

documentan la manera de ver de estos<br />

directores y de estos públicos, ilustrando así<br />

los sentimientos, fantasías e ideas (preconcebidas)<br />

sobre los temas filmados.<br />

Una de les preguntas importantes a la que el<br />

Taller procurará responder es : « ¿Qué<br />

debemos, como archiveros, historiadores,<br />

cineastas, hacer con este material hoy en<br />

día ? ».<br />

El Taller propondrá proyecciones y<br />

conferencias y abordará temas de historia y<br />

de archivística no estudiados o programados<br />

hasta entonces. El Taller se propone una reanimación,<br />

una re-visión y una re-evaluación<br />

de material que se podria calificar un tanto<br />

precipitadamente como colonial, en el<br />

contxto internacional.<br />

La participacion al Taller es exclusivamente<br />

sobre invitación. Para facilitar una<br />

participación « virtual » más amplia, las<br />

discusiones seran grabadas, editadas y<br />

difundidas por Internet.

Jerusalem<br />

Steven Spielberg<br />

Jewish <strong>Film</strong> Archive<br />

Adolf Eichmann at his trial in Jerusalem in 1961<br />

Holocauste : Importante collection de<br />

films à la Hebrew University.<br />

La SSJFA a été choisie comme dépositaire de<br />

l’une des plus importantes collections de<br />

films sur l’Holocauste, celle du Ghetto<br />

Fighter’s House, Musée de l’Holocauste et de<br />

la Résistance. Situé au nord du pays, le<br />

Musée a été créé en 1949 par des survivants<br />

de l’Holocauste. C’est l’un des principaux<br />

centres de documentation sur la Shoah. Il<br />

abrite, en particulier, une collection<br />

d’environ 1.600 films et vidéos sur<br />

l’Holocauste. Il s’agit de films de fiction<br />

récents aussi bien que de fragments de<br />

documentaires jamais montés. Par ailleurs,<br />

l’année dernière, dans le cadre d’un<br />

programme commun, l’Archive d’Etat<br />

d’Israël et le SSJFA ont préservé les<br />

enregistrements en vidéo du procès d’Adolf<br />

Eichmann à partir des bandes originales de<br />

deux pouces. Cette année, une vidéo<br />

cassette d’une heure sera éditée afin de<br />

diffuser les extraits les plus marquants sur<br />

les déclarations émises pendant le procès.<br />

Holocausto : importante colección de<br />

películas pasa a la Hebrew University<br />

Major Holocaust <strong>Film</strong> Collection Comes to Hebrew University<br />

The Steven Spielberg Jewish <strong>Film</strong> Archive, at the Hebrew University <strong>of</strong><br />

Jerusalem, has become the depository for one <strong>of</strong> the world’s largest collections<br />

<strong>of</strong> films about the Holocaust, that <strong>of</strong> the Ghetto Fighters’<br />

House, Museum <strong>of</strong> the Holocaust and the Resistance (Beit Lohamei<br />

Haghetaot).<br />

The Ghetto Fighters’ House, located in northern Israel, was established<br />

by Holocaust survivors in 1949. It is among Israel’s premier Shoah documentation<br />

centers, containing over a dozen large archival groups. The<br />

film archive includes over 1600 films and videos on all aspects <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Holocaust. The richness <strong>of</strong> the collection and the rarity <strong>of</strong> some <strong>of</strong> the<br />

items can be attributed to two main factors. Firstly, the task <strong>of</strong> gathering<br />

moving image records <strong>of</strong> the Holocaust period was undertaken immediately<br />

after the Ghetto Fighters’ House was founded, resulting in one <strong>of</strong><br />

the earliest <strong>of</strong> these efforts by any such institution. The second, no less<br />

important, factor was the energy <strong>of</strong> the late Miriam Novitch, who collected<br />

all types <strong>of</strong> material, including film, for several decades, on behalf<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Ghetto Fighters’ House, tracking down and acquiring hundreds <strong>of</strong><br />

titles in the process.<br />

According to the agreement between the two institutions, all the 35 mm<br />

and 16 mm prints in the Ghetto Fighters’ House collection will henceforth<br />

be housed in the Spielberg Archive’s new premises on Mount<br />

Scopus. Also to be deposited are hundreds <strong>of</strong> cans <strong>of</strong> Jewish historical<br />

material that the Museum duplicated from archives all over the world<br />

for use in its famous trilogy <strong>of</strong> documentary films dealing with different<br />

aspects <strong>of</strong> the Holocaust: “The 81st Blow”, “The Last Sea” and “The Face<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Revolt”. A third party to the agreement, the United States<br />

Holocaust Memorial Museum, will fund the transfer <strong>of</strong> this material to<br />

video viewing copies to be archived at the Museum in Washington, D.C.,<br />

as well as in Israel. This tri-partite arrangement was negotiated by<br />

Spielberg Archive Director Marilyn Koolik with Yossi Shavit, Archive<br />

Director <strong>of</strong> the Ghetto Fighters’ House, and Raye Farr, Director <strong>of</strong> <strong>Film</strong><br />

and Video at the US Holocaust Memorial Museum.<br />

Work on this project, scheduled to be completed over a three-year<br />

period, commenced shortly after the agreement was finalized in late<br />

1997. The range <strong>of</strong> material in the collection is very wide, encompassing<br />

everything from comparatively recent feature film productions to<br />

unedited documentary fragments. This major deposit further consolidates<br />

the Spielberg Archive’s position as a key resource for film documentation<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Holocaust. Last year, in a co-operative venture that<br />

marked the first time in Israeli history that government funds were spent<br />

on moving image preservation, the Spielberg Archive and the Israel State<br />

Archive digitally preserved the video record <strong>of</strong> the 1961 trial <strong>of</strong> Adolf<br />

Eichmann from the original two-inch videotapes. The recording <strong>of</strong> the<br />

trial itself was a technical landmark, as it was the first time that the<br />

medium <strong>of</strong> video had been used for news purposes. This year, facilitated<br />

by the preservation <strong>of</strong> the trial record, a one-hour videocassette will be<br />

4 <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Film</strong> <strong>Preservation</strong> / <strong>56</strong> / 1998

eleased containing some <strong>of</strong> the most important segments <strong>of</strong> testimony<br />

delivered at the trial. The organizations responsible for this undertaking<br />

are the Spielberg Archive, the Israel State Archive and Yad Vashem,<br />

Israel’s Holocaust Martyrs’ and Heroes’ Remembrance Authority, which is<br />

contributing the consultation services <strong>of</strong> its experts to help in selecting<br />

the sequences to be included in the tape. Aimed primarily at Israeli educational<br />

institutions, the tape will be distributed on a non-pr<strong>of</strong>it basis<br />

under the auspices <strong>of</strong> all three institutions.<br />

Spielberg Archive TV Series Begins Broadcasting<br />

A series <strong>of</strong> short television programs, co-produced by the Steven<br />

Spielberg Jewish <strong>Film</strong> Archive as a contribution to the State <strong>of</strong> Israel’s<br />

50th anniversary celebrations, is now being broadcast on a weekly basis<br />

from early February to late June, 1998. The series, comprising 14<br />

episodes, was co-produced with Israel Educational Television, which will<br />

also distribute it on cassette to high schools and other educational institutions.<br />

Each installment consists <strong>of</strong> historical footage related to the pioneering<br />

efforts that preceded and followed the birth <strong>of</strong> the State, and<br />

each was based on a different film from the period in the Archive’s collection.<br />

Aimed at a youthful audience, the project was the brainchild <strong>of</strong><br />

Educational Television producer Yossi Halachmi and historical consultant<br />

Dr. Dalia Hurevitz. At present, the series exists only in a Hebrew version.<br />

Disaster in Oaxaca<br />

Francisco Gaytan<br />

At the risk <strong>of</strong> sounding melodramatic, it can be said that we are all aware<br />

<strong>of</strong> the tragic story <strong>of</strong> Sergei Eisenstein’s journey to Mexico in 1930 to<br />

film a movie produced by the American writer, Upton Sinclair. The<br />

tragedy lies in the fact that conflicts arose between Eisenstein and<br />

Sinclair with the result that Sinclair would not allow him<br />

to edit the filmed material. Knowing the importance <strong>of</strong><br />

editing in Eisenstein’s work we realize that no editing<br />

done by any other film-maker has the same power as<br />

Eisenstein’s own. The editing we are familiar with, such<br />

as Time In The Sun by Marie Seton, Storm over Mexico by<br />

Sol Lesser, and even the more recent Que Viva Mexico,<br />

edited by Eisenstein’s collaborator Alexandrov, all lack the<br />

vitality and distinction <strong>of</strong> Eisenstein’s own work.<br />

What few people know is that Eisenstein about that same<br />

time made another film in Mexico, which was finished<br />

and even shown here in Mexico. We at the UNAM <strong>Film</strong><br />

Archive knew about this film but we did not have a copy.<br />

Fortunately the Museum <strong>of</strong> Modern Art in New York did<br />

have this material and generously provided us with a<br />

copy <strong>of</strong> the film, demonstrating once more how the collaboration<br />

5 <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Film</strong> <strong>Preservation</strong> / <strong>56</strong> / 1998<br />

El SSJFA ha sido designado depositario de<br />

una de las más importantes colecciones de<br />

filmes sobre el Holocausto : la del Ghetto<br />

Fighter’s House del Museo del Holocausto y<br />

de la Resistencia. El museo ha sido creado<br />

por sobrevivientes del Holocausto en el norte<br />

del país en 1949. Se trata de uno de los<br />

principales centros de documentación sobre<br />

la Shoah. Una de sus secciones consta de<br />

una colección de unos 1.600 filmes y cintas<br />

magnéticas sobre diversos aspectos del<br />

Holocausto. Se trata tanto de películas de<br />

ficción recientes que de fragmentos de<br />

documentales inéditos. Por otra parte, el<br />

año pasado, el Archivo estatal de Israel y el<br />

SSJFA presevaron conjutamente las<br />

grabaciones en vídeo del proceso de Adolf<br />

Eichmann a partir de la cintas originales de<br />

dos pulgadas. Este año, una video cassete<br />

de una hora sera publicada con el fin de<br />

difundir las declaraciones más importantes<br />

del proceso.<br />

México<br />

<strong>Film</strong>oteca de la UNAM

Désastre à Oaxaca<br />

En janvier 1931, la ville d’Oaxaca a été<br />

dévastée par un tremblement de terre.<br />

Lorsqu’il apprit la nouvelle, Eisenstein prit<br />

un avion et s’y rendit en compagnie de son<br />

équipe, Alexandrov et Tissé, et y tourna,<br />

avec son style très personnel, divers aspects<br />

du désastre.<br />

L’existence de ce film était connue à l’UNAM,<br />

mais il n’y avait pas de copie dans ses<br />

collections. Par chance, le MoMA possédait<br />

ce matériel et mit généreusement une copie à<br />

la disposition de l’UNAM, démontrant une<br />

fois de plus combien la collaboration entre<br />

archives de la <strong>FIAF</strong> est importante pour la<br />

préservation et la diffusion du patrimoine<br />

cinématographique.<br />

Disaster in Oaxaca, 1931, Sergei Eisenstein<br />

Desastre en Oaxaca<br />

En enero de 1931, la ciudad de Oaxaca fué<br />

destruída por un terremoto. Cuando se<br />

enteró, Eisenstein tomó un avión con su<br />

equipo, Alexandrov y Tissé, y rodó, con su<br />

estilo tan personal, diversos aspectos del<br />

desastre. La UNAM tenía conocimiento de la<br />

existencia de esta película, pero no disponía<br />

de copia en sus archivos. Afortunadamente,<br />

el MoMA poseía el material, que puso<br />

generosamente a disposición, demostrando<br />

una vez más cuán importante es la<br />

cooperación entre archivos de la <strong>FIAF</strong> para<br />

la preservación y la difusión del patrimonio<br />

cinematográfico mundial.<br />

1 La Memoria Restaurada, UNAM <strong>Film</strong><br />

Archive, 1996. Eduardo de la Vega.<br />

between film archives within <strong>FIAF</strong> is <strong>of</strong> fundamental importance for film<br />

preservation and diffusion. I once said that films earn for themselves<br />

their restoration and diffusion, and I think this film is a case in point. It<br />

is a documentary called in Mexico La destruccion de Oaxaca1 (The<br />

Destruction <strong>of</strong> Oaxaca) according to newspaper items <strong>of</strong> that time,<br />

although the copy provided by MoMA bears the title in Spanish: El<br />

desastre en Oaxaca (The Disaster in Oaxaca.)<br />

In January 1931 the city <strong>of</strong> Oaxaca (capital city <strong>of</strong> a southern state <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Mexican Republic) was devastated by an earthquake. Eisenstein saw in<br />

this catastrophe an opportunity to collect funds for the filming <strong>of</strong> Que<br />

Viva México, by showing the film about Oaxaca not only in Mexico but<br />

also in the United States and other parts <strong>of</strong> the world. As soon as he<br />

heard about the earthquake he got on a plane with his equipment and<br />

his team, Alexandrov and Tisse, and flew to Oaxaca where he filmed,<br />

with his very individualistic style, diverse aspects<br />

<strong>of</strong> the disaster. The film’s 28 captions (it is a<br />

silent movie), punctuate the film’s progress but<br />

given Eisenstein’s social vision they could not be<br />

other than these examples :<br />

“Rich people’s houses”; “Poor people’s houses”,- “God’s<br />

dwelling place”; “The houses <strong>of</strong> the dead” ; “The<br />

dreadful misery <strong>of</strong> these people cries out for help”.<br />

While this film is not precisely a rescue made by<br />

the UNAM <strong>Film</strong> Archive, it does seem to count as<br />

a discovery <strong>of</strong> ours, as <strong>of</strong> the first time we<br />

showed it in 1996.<br />

By the miracles <strong>of</strong> present day communication,<br />

on learning <strong>of</strong> the existence <strong>of</strong> this film, several<br />

film archives have asked for it, not only here in<br />

Mexico but also abroad. MoMA has authorized<br />

its diffusion and it has therefore been shown very successfully all in<br />

Spain, at the <strong>Film</strong>oteca de la Generalitat de Cataluna, at the Huelva<br />

Festival and the Lleida Festival. At the time <strong>of</strong> writing this article the<br />

copy has also been authorized for showing at the Cineteca Nacional de<br />

Mexico and in Europe at the Oesterreichisches <strong>Film</strong>museum and at the<br />

Landeshauptstadt München <strong>Film</strong>museum.<br />

6 <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Film</strong> <strong>Preservation</strong> / <strong>56</strong> / 1998

The Administration <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Federation: some preliminary results<br />

from an analysis <strong>of</strong> past Executive<br />

Committees <strong>of</strong> <strong>FIAF</strong><br />

Roger Smither<br />

Introduction<br />

During the discussion in Beijing <strong>of</strong> possible changes to the procedures to<br />

be used in electing the Officers and Executive Committee members <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>FIAF</strong>, it was suggested that it might be interesting or useful to study the<br />

composition <strong>of</strong> previous Executives and analyse the results <strong>of</strong> previous<br />

elections. Besides being <strong>of</strong> value in its own right as part <strong>of</strong> the study <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>FIAF</strong>’s history, it was thought that such analysis might show up how<br />

well, or how badly, the Federation functioned as a democracy - for<br />

example, how much artificial pressure for rotation <strong>of</strong> <strong>of</strong>fice holders was<br />

needed, how <strong>of</strong>ten the <strong>of</strong>ficers had been elected without a «real» election<br />

(in other words, with only one name on the ballot paper), and so on.<br />

More controversially, analysis <strong>of</strong> the composition <strong>of</strong> past ECs might also<br />

provide a basis for informed consideration <strong>of</strong> the question <strong>of</strong> how true is<br />

the perception that <strong>FIAF</strong> has traditionally been dominated by one or<br />

more particular archive, country or linguistic/cultural group. This paper<br />

<strong>of</strong>fers a preliminary report on such an analysis.<br />

Sources and their limitations<br />

The information used in this analysis is not 100% complete. Data on the<br />

composition <strong>of</strong> early Executive Committees is available from the book 50<br />

Ans d’Archives du <strong>Film</strong> («the Golden Book» published in 1986) and its<br />

predecessor International Federation <strong>of</strong> <strong>Film</strong> Archives / Fédération<br />

Internationale des Archives du <strong>Film</strong> (published in 1958). These books do<br />

not, however, give details about the elections to each EC, so do not permit<br />

analysis <strong>of</strong> the number <strong>of</strong> candidates, etc. Information on elections<br />

has only been analysed as far back as 1966 (the period for which I have<br />

had access to copies <strong>of</strong> the minutes from General Assemblies). If there is<br />

any desire to complete this project, further research will be needed into<br />

the history <strong>of</strong> early elections.<br />

It is also important to note, before making too much <strong>of</strong> the results <strong>of</strong> the<br />

‘analysis’, that it hides or reflects some distorting factors. First <strong>of</strong> all, and<br />

most obviously, there are various changes in the composition <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Executive and the frequency <strong>of</strong> elections. The number <strong>of</strong> people constituting<br />

the Executive increased from 4 in 1946 to 9 in 1953 and 15 in<br />

1959. In 1961 it settled into the stable pattern <strong>of</strong> 3 <strong>of</strong>ficers, 8 members<br />

and 3 reserves which lasted until 1987, when the present structure <strong>of</strong> 3<br />

7 <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Film</strong> <strong>Preservation</strong> / <strong>56</strong> / 1998<br />

<strong>FIAF</strong>

<strong>of</strong>ficers plus 10 members was introduced. Another important change was<br />

the adoption <strong>of</strong> the principle <strong>of</strong> enforced rotation in <strong>of</strong>fice with the introduction<br />

<strong>of</strong> the «three term» rule, agreed by the General Assembly in<br />

Lausanne in 1979. The frequency <strong>of</strong> elections changed as well - the<br />

change to regular elections every two years was also introduced in 1979;<br />

previously elections had normally been annual events.<br />

Other distortions are less easy to spot, and I do not claim to have identified<br />

all <strong>of</strong> them even in the elections I have looked at. However, some <strong>of</strong><br />

them <strong>of</strong>fer interesting indications <strong>of</strong> ways in which <strong>FIAF</strong> has in the past<br />

addressed the issue <strong>of</strong> reforming itself. For example -<br />

• in 1967, the Minutes record one delegate declining nomination «out <strong>of</strong><br />

respect for the <strong>FIAF</strong>’s unwritten and traditional rule <strong>of</strong> requesting only<br />

one member from each country to serve on the Executive Committee»<br />

- a rule that has since been institutionalised to limit representation to<br />

one member from each archive.<br />

• in 1969 and 1970, special steps were taken to ensure the election <strong>of</strong><br />

members from outside Europe, two places out <strong>of</strong> eight being voted for<br />

on this basis before the remaining places were filled. This procedure<br />

was then abandoned, after Eileen Bowser, who had failed to be elected<br />

to a non-European place, was in any case elected in the general ballot.<br />

• in 1971, and at various elections thereafter, the outgoing EC<br />

announced that it had made or was making specific efforts to ensure<br />

that there should be more than one nomination for each <strong>of</strong> the <strong>of</strong>ficers,<br />

though a study <strong>of</strong> the following pages will indicate that these efforts<br />

have rarely had much impact on actual election procedures.<br />

• also in 1971, the outgoing EC particularly asked for the election to the<br />

EC <strong>of</strong> the host <strong>of</strong> the next year’s congress<br />

• in 1972, it was suggested specifically to restrict one <strong>of</strong> the «reserve»<br />

EC places to a delegate who had never yet served on the Executive<br />

Committee<br />

Results<br />

The results <strong>of</strong> this analysis are now available in various ‘products’.<br />

Complete information on the history <strong>of</strong> all previous generations <strong>of</strong> <strong>FIAF</strong>’s<br />

Executive Officers and Committees has been compiled into two documents<br />

which have been placed with the Secretariat in Brussels, where<br />

they can be made available for anyone interested in reading them. The<br />

first document is a ‘time line’ showing the changing composition <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Officers and <strong>of</strong> the Executive Committee over the sixty-year history <strong>of</strong><br />

the Federation. The second is an alphabetical ‘Who’s Who’ which identifies<br />

the 102 people named in the ‘time line’ by listing their parent archive<br />

and their service on the Executive. From these two documents are<br />

derived the tables and charts reproduced in the following pages.<br />

Preliminary conclusions derived from this analysis are <strong>of</strong>fered in two<br />

groups <strong>of</strong> observations, given below. Observation Group 1 examines various<br />

questions relating to the degree <strong>of</strong> ‘turnover’ in the composition <strong>of</strong><br />

8 <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Film</strong> <strong>Preservation</strong> / <strong>56</strong> / 1998

the <strong>FIAF</strong> Executive. Observation Group 2 examines questions relating to<br />

the origins <strong>of</strong> those serving as <strong>FIAF</strong>’s Executive over the past sixty years.<br />

OBSERVATION GROUP 1: ‘TURNOVER’<br />

1A. Turnover: arrival <strong>of</strong> «new faces» in the EC<br />

In the 40 Executive Committees that have held <strong>of</strong>fice since 1946, on<br />

average just under 2.5 new members have joined the EC after each<br />

election<br />

One measure <strong>of</strong> ‘turnover’ in an administration is the extent to which<br />

elections do - or do not - introduce «new faces». In spite <strong>of</strong> the general<br />

impression that <strong>FIAF</strong> inclines to stability, there have only been 4 elections<br />

out <strong>of</strong> the 40 held since the revival <strong>of</strong> <strong>FIAF</strong> in 1946 at which no<br />

new faces were introduced onto the Executive. At all other elections,<br />

between 1 and 8 new people joined the ranks <strong>of</strong> those elected, the average<br />

being 2.37. (See Chart 1.) This position would seem to be reasonably<br />

satisfactory, although at the extremes, while zero turnover is certainly not<br />

good, it could be argued that a turnover <strong>of</strong> 8 people out <strong>of</strong> a Committee<br />

<strong>of</strong> 13 (as happened in 1993) represents a threat to continuity that is just<br />

as unhealthy.<br />

Eight<br />

Seven<br />

Six<br />

Five<br />

Four<br />

Three<br />

Two<br />

One<br />

None<br />

Chart 1: Turnover in EC Elections<br />

0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14<br />

1B. Turnover: Contested elections to the three ‘Officer’ posts<br />

There is a tendency for Officer posts to be filled by the election <strong>of</strong><br />

single, unopposed candidates. This tendency is stronger for the<br />

<strong>of</strong>fices <strong>of</strong> Secretary-General and Treasurer than it is for the<br />

Presidency, and appears to be gaining in strength over recent years.<br />

Another measure <strong>of</strong> turnover is the extent to which elections for the<br />

9 <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Film</strong> <strong>Preservation</strong> / <strong>56</strong> / 1998<br />

F R E Q U E N C Y

three Officers’ positions and for the EC are contested. It is common<br />

knowledge that several <strong>FIAF</strong> <strong>of</strong>ficers have had long tenure in their positions,<br />

but this could be as a result <strong>of</strong> regularly winning contested elections.<br />

A study <strong>of</strong> election returns, however, shows that this is not the<br />

case. In the 23 elections that have taken place since 1966,<br />

• the President was elected without anyone standing against him/her on<br />

fourteen occasions, 61% <strong>of</strong> the elections held<br />

• the Secretary-General was elected without anyone standing against<br />

him/her sixteen times, 70% <strong>of</strong> the elections held<br />

• the Treasurer was elected without anyone standing against him/her on<br />

fourteen occasions, again 61% <strong>of</strong> the elections held<br />

• If the focus is narrowed to the last 10 elections (1979 - 1997: also the<br />

period in which <strong>FIAF</strong> has introduced the «three term» rule), then we<br />

find the position changed as follows<br />

• the President has been elected unopposed on six occasions (60%)<br />

• the Secretary-General has been elected unopposed on seven occasions<br />

(70%)<br />

• the Treasurer has been elected unopposed on eight occasions (80%)<br />

The above analysis would appear to confirm the opinion voiced by several<br />

EC members in Beijing that elections for the Secretary-General and<br />

the Treasurer have not in recent years conformed to the optimum levels<br />

<strong>of</strong> democratic interest and involvement by the membership at large, and<br />

formed part <strong>of</strong> the justification advanced in the 1998 Prague Congress<br />

for changes to the current procedures.<br />

1C. Turnover: Ratio <strong>of</strong> candidates to places in EC elections<br />

In the 23 elections held since 1966, an average <strong>of</strong> 1.81 candidates<br />

have <strong>of</strong>fered themselves for each ordinary post on the EC. The figures<br />

at all the last four elections have, however, been below this<br />

average.<br />

A third measure <strong>of</strong> the democratic ‘health’ <strong>of</strong> an organisation may be the<br />

number <strong>of</strong> candidates presenting themselves for election to that organisation’s<br />

governing body. Discounting the three separately-elected ‘Officer’<br />

posts (which were the subject <strong>of</strong> the previous section) <strong>FIAF</strong>’s record in<br />

this area over the past 23 elections shows an average <strong>of</strong> 1.81 candidates<br />

<strong>of</strong>fering themselves for each post on the Executive Committee. (See Chart<br />

2.) This would appear to be quite healthy, although it may be noted that<br />

the four elections so far held during the 1990s have all seen ratios lower<br />

than this average - a trend that should give cause for concern if it continues.<br />

10 <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Film</strong> <strong>Preservation</strong> / <strong>56</strong> / 1998

Chart 2: Turnover in EC Elections<br />

Ratio <strong>of</strong> Candidates to Places in EC Elections, 1966-1997<br />

1997<br />

1995<br />

1993<br />

1991<br />

1989<br />

1987<br />

1985<br />

1983<br />

1981<br />

1979<br />

1978<br />

1977<br />

1976<br />

1975<br />

1974<br />

1973<br />

1972<br />

1971<br />

1970<br />

1969<br />

1968<br />

1967<br />

1966<br />

0<br />

1D. Turnover: Long-serving members <strong>of</strong> the <strong>FIAF</strong> Executive<br />

In the more than fifty years since the reconstitution <strong>of</strong> <strong>FIAF</strong> in 1946,<br />

102 people have served on the Executive. Of this total, 20 individuals<br />

have served for 10 or more years. The longest service recorded<br />

by any one individual is 31 years. In contrast to this figure, 23 individuals<br />

have been elected to a single one- or two-year term.<br />

A fourth and last measure <strong>of</strong> ‘turnover’ in an institution’s governing body<br />

may be the periods <strong>of</strong> long service recorded by individuals. This information<br />

is available in full in the information held at the Secretariat. Ranked<br />

in order <strong>of</strong> number <strong>of</strong> years served, and listed with the <strong>of</strong>fices they have<br />

held, the 20 people with the longest record <strong>of</strong> service are listed below.<br />

(See Table 1.)<br />

Some <strong>of</strong> those listed in the table not only have long tenure on the EC in<br />

general, but also have long periods in occupation <strong>of</strong> a single <strong>of</strong>fice.<br />

However, it will be seen that the large majority <strong>of</strong> such cases are people<br />

whose involvement with the EC dates back to the 1960s or earlier. The<br />

introduction <strong>of</strong> the «three term» rule in 1979 appears to have signalled<br />

the end <strong>of</strong> the era when this needed to be considered as a serious «problem»<br />

- if indeed it ever was.<br />

11 <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Film</strong> <strong>Preservation</strong> / <strong>56</strong> / 1998<br />

0.5 1 1.5 2 2.5<br />

RATIO

Note that the following abbreviations are used in the table for positions<br />

held:<br />

SecGen - Secretary-General<br />

VP - Vice President<br />

EC - full member <strong>of</strong> the Executive Committee<br />

Res - reserve member <strong>of</strong> the Executive Committee (1961-1987 only)<br />

TABLE No 1:<br />

Long-Serving Officers and Members <strong>of</strong> the <strong>FIAF</strong> Executive<br />

Yrs Name Positions Held<br />

31 Jan De Vaal SecGen 1960-61; Treasurer 1963-64, 1965-66,<br />

1977-85;VP 1953-54; EC 1949-53, 1961-62,<br />

1966-69, 1974-77; Res 1958-59, 1962-63, 1964-<br />

65, 1969-71, 1973-74, 1985-87<br />

27 Ernest Lindgren SecGen 1951-52; Treasurer 1946-48; VP 1948-<br />

51, 1952-54, 1955-71; EC 1954-55, 1972-73;<br />

Res 1971-72<br />

27 Jerzy Toeplitz President 1948-1972; VP 1946-48; EC 1972-73<br />

23 Raymond Borde SecGen 1978-79; Treasurer 1985-91; VP 1972-<br />

73, 1981-85; EC 1966-67, 1969-70, 1971-72,<br />

1973-78, 1979-81; Res 1967-68<br />

23 Robert Daudelin President 1989-95; SecGen 1979-85; EC 1974-<br />

79, 1985-1989, 93-95<br />

23 Wolfgang Klaue President 1979-83; VP 1973-79, 1985-89; EC<br />

1968-73, 1989-91<br />

23 Vladimir Pogacic President 1972-79; VP 1969-72, 1979-81; EC<br />

19<strong>56</strong>-57, 1962-69; Res 1958-59, 1960-62<br />

22 Eileen Bowser VP 1977-1985; EC 1969-71, 1972-77 1985-91;<br />

Res 1971-72<br />

21 Victor Privato VP 1958-79<br />

20 Jacques Ledoux SecGen 1961-78; EC 1959-60, 1978-79; Res<br />

1960-61<br />

16 David Francis VP 1979-85; EC 1977-79, 1985-93<br />

15 Henri Langlois SecGen 1946-48, 1955-57, 1959-60; VP 1954-<br />

55, 1957-58; EC 1948-54, 1958-59, 1960-61<br />

14 Eva Orbanz SecGen 1989-95; VP 1987-89; EC 1981-85<br />

14 Paulo E Sales Gomes Treasurer 1952-53; VP 1951-52, 19<strong>56</strong>-58,<br />

1959-60, 1963-65; EC 1948-49, 1953-<strong>56</strong>, 1961-<br />

63; Res 1958-59<br />

12 Anna-Lena Wibom President 1985-89; Treasurer 1991-93; EC<br />

1981-85, 1989-91<br />

11 John Kuiper VP 1971-77; EC 1970-71, 1977-78; Res 1978-81<br />

11 Jon Stenklev Treasurer 1973-77; EC 1971-72, 1979-81; Res<br />

1970-71, 1972-73, 1977-79<br />

12 <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Film</strong> <strong>Preservation</strong> / <strong>56</strong> / 1998

10 Freddy Buache SecGen 1957-58; Treasurer 1955-<strong>56</strong>; EC 19<strong>56</strong>-<br />

57, 1978-81; Res 1973-74, 1975-78<br />

10 Guido Cincotti SecGen 1985-89; EC 1981-85, 1989-91<br />

10 André Thirifays SecGen 1952-55, 1958-59; Treasurer 19<strong>56</strong>-58;<br />

VP 1949-52; EC 1955-<strong>56</strong><br />

In contrast to the above, it may be <strong>of</strong> interest to note that out <strong>of</strong> 99 people<br />

recorded as having been elected to serve <strong>FIAF</strong> in some capacity<br />

between 1938 and 1995, just under one quarter - 23 individuals - have<br />

been elected only to a single term. (This figure excludes those elected for<br />

the first time in 1997, since the length <strong>of</strong> their service on the EC can not<br />

be predicted.)<br />

OBSERVATION GROUP 2: ‘COMPOSITION’<br />

For the purposes <strong>of</strong> this group <strong>of</strong> observations, the 102 individuals from<br />

49 archives in 33 countries (counting Germany as a single country - 34<br />

if the period <strong>of</strong> a divided Germany is taken into account) who have<br />

served in some capacity or other on the <strong>FIAF</strong> Executive have been<br />

«weighted» according to the number <strong>of</strong> years they served. This has generated<br />

a unit <strong>of</strong> measurement that could be termed the «person-year» -<br />

so that the Cinémathèque Québécoise, which has provided two members<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Executive over the years (Françoise Jaubert with 2 years service,<br />

and Robert Daudelin with 23) has a weighting <strong>of</strong> 25 person-years. The<br />

analysis given on the following pages is made on the basis <strong>of</strong> this weighting.<br />

2A. Composition: Archive representation on the <strong>FIAF</strong> EC<br />

In the history <strong>of</strong> <strong>FIAF</strong>, 49 archives have contributed members to the<br />

Executive. Of this total, 14 archives have contributed 20 or more<br />

‘person-years’ <strong>of</strong> service - the greatest total by any one archive being<br />

55.<br />

Arranged according to <strong>FIAF</strong>’s traditional alphabetical listing by city, the<br />

archives that have had staff members on the <strong>FIAF</strong> Executive between<br />

1938 and 1999 (the end <strong>of</strong> the current term for the present EC), with<br />

their respective weighting, are listed in Table 2A.<br />

TABLE No 2A:<br />

ARCHIVE REPRESENTATION ON THE EXECUTIVE<br />

(alphabetical)<br />

Amsterdam 35<br />

Beograd 24<br />

Berlin RFA 2<br />

Berlin SDK 14<br />

Berlin SFA 32<br />

Bogota FPFC 4<br />

Bois d’Arcy 6<br />

Bologna 2<br />

13 <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Film</strong> <strong>Preservation</strong> / <strong>56</strong> / 1998<br />

Bruxelles 34<br />

Bucuresti 7<br />

Budapest 11<br />

Buenos Aires 2<br />

Canberra 2<br />

Frankfurt DIF 2<br />

Habana 12<br />

Helsinki 3

Kobenhavn 14<br />

Lausanne 17<br />

Lisboa 4<br />

London IWM 6<br />

London NF(TV)A 55<br />

Los Angeles UCLA 12<br />

Madrid 6<br />

Mexico UNAM 8<br />

Milano 10<br />

Montevideo CU 2<br />

Montevideo SODRE 1<br />

Montreal 25<br />

Moskva 26<br />

New York MOMA 39<br />

Oslo 12<br />

Ottawa 12<br />

Paris CF 17<br />

If the 14 archives with weightings <strong>of</strong> 20 or more person-years are separated<br />

from Table 2A and listed in weighted order, the result contains not<br />

only some predictable names but also some inclusions (and omissions)<br />

that may be considered more surprising. (See Table 2B.)<br />

TABLE No 2B:<br />

ARCHIVE REPRESENTATION ON THE EXECUTIVE (weighted)<br />

London NF(TV)A 55<br />

New York MOMA 39<br />

Amsterdam 35<br />

Bruxelles 34<br />

Berlin SFA 32<br />

Warszawa 28<br />

Toulouse 27<br />

Moskva 26<br />

Montreal 25<br />

Beograd 24<br />

Stockholm 24<br />

Praha 22<br />

Rochester 21<br />

Sao Paulo 20<br />

Whether any conclusions may be drawn from the above, to justify concerns<br />

about the traditional dominance <strong>of</strong> the Federation by any single<br />

archive, seems very questionable.<br />

2B. Composition: National representation on the <strong>FIAF</strong> EC<br />

Collated by country, the figures show 14 countries with over 20<br />

years <strong>of</strong> collective service, <strong>of</strong> which 4 have 50 or more years service,<br />

the greatest total by a single country being 76. (See Chart 3)<br />

14 <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Film</strong> <strong>Preservation</strong> / <strong>56</strong> / 1998<br />

Praha 22<br />

Pune 6<br />

Rio de Janeiro 8<br />

Rochester 21<br />

Roma 17<br />

San Juan de PR 2<br />

Rio de Janeiro 8<br />

Sao Paulo 20<br />

S<strong>of</strong>ia 8<br />

Stockholm 24<br />

Tokyo 2<br />

Toulouse 27<br />

Torino 2<br />

Warszawa 28<br />

Washington LC 4<br />

Wien OFA 2<br />

Wien OFM 6

Argentina<br />

Australia<br />

Austria<br />

Belgium<br />

Brazil<br />

Bulgaria<br />

Canada<br />

Colombia<br />

Cuba<br />

Czech R<br />

Denmark<br />

Finland<br />

France<br />

Germany<br />

Hungary<br />

India<br />

Italy<br />

Japan<br />

Mexico<br />

Netherlands<br />

Norway<br />

Poland<br />

Portugal<br />

Puerto Rico<br />

Romania<br />

Spain<br />

Sweden<br />

Switzerland<br />

UK<br />

Uruguay<br />

USA<br />

USSR<br />

Yugoslavia<br />

Chart 3: EC Service by Country<br />

2C. Composition: Representation on the <strong>FIAF</strong> EC by Continent<br />

and Language Group<br />

If the figures given in the preceding pages are collated by continent and<br />

language group, patterns emerge that appear to confirm the traditional<br />

complaints that <strong>FIAF</strong> is heavily dominated, in geographical terms, by the<br />

‘Northern Hemisphere’, and within that grouping very specifically by<br />

Europe. In linguistic terms, the largest single group <strong>of</strong> members have<br />

come from archives in countries where the first language is English, with<br />

French in a reasonably close second place. The historic division among<br />

other language groups is less clear cut than might be expected.<br />

I suggest, however, that it would be unwise to load too much significance<br />

into the very superficial analysis so far made <strong>of</strong> these issues. It<br />

might be constructive to look more specifically at the geographical composition<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>FIAF</strong>’s Executive in the period since 1979 (last ten elections)<br />

than over the whole <strong>of</strong> its history since the significant expansion <strong>of</strong> <strong>FIAF</strong><br />

beyond Europe and North America is a relatively recent phenomenon. It<br />

must also be pointed out that there are simply more archives in certain<br />

15 <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Film</strong> <strong>Preservation</strong> / <strong>56</strong> / 1998<br />

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80

countries (and continents) than others, so a «fair» representation by distribution<br />

<strong>of</strong> archives will tend to look distinctly «unfair» when mapped<br />

according to geography. Equally, the ‘language’ issue would be better<br />

explored if the category <strong>of</strong> those outside the English/French/Spanish<br />

speaking groups took account <strong>of</strong> the preferred <strong>of</strong>ficial languages <strong>of</strong> EC<br />

members belonging to that category. These are not arguments for complacency,<br />

but they do indicate the dangers <strong>of</strong> jumping to conclusions<br />

without more careful research.<br />

2C1. Representation by Continent<br />

Collated by continent, the figures show an overwhelming domination<br />

by Europe, whose archives have provided over 70 % <strong>of</strong> EC<br />

membership over the years.<br />

Chart 4: EC Service by Continent<br />

Europe<br />

72.3%<br />

2C2. Representation by Language<br />

Collated by language group, the figures show most clearly the need<br />

for more careful analysis.<br />

If the historic weightings <strong>of</strong> individual archives or countries are collected<br />

according to native language, a position emerges that emphasises only<br />

that the majority <strong>of</strong> EC business has always been done in a language<br />

(whether English, French or Spanish) that is not native to the majority <strong>of</strong><br />

participants - 9 other native languages have each provided over 20 ‘person-years’<br />

<strong>of</strong> EC service, 4 <strong>of</strong> which - German, Dutch, Portuguese and<br />

16 <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Film</strong> <strong>Preservation</strong> / <strong>56</strong> / 1998<br />

North America<br />

7.2%<br />

English<br />

23.9%<br />

Asia/Pacific<br />

1.5%<br />

South & Latin America<br />

9.0%<br />

Chart 5: EC Service by Native Language<br />

Other<br />

51.3%<br />

Spanish<br />

5.6%<br />

French<br />

19.2%

Italian - actually score over 30 (30 representing 4.6 % <strong>of</strong> the total). As<br />

already noted, however, it is not suggested that much importance be<br />

attached to these «findings» without more research being done.<br />

HISTORICAL SUMMARY<br />

As a final ‘output’ from this survey, Table 3 <strong>of</strong>fers a resumé <strong>of</strong> all those<br />

who have held the three major <strong>of</strong>fices in the Federation since its founding<br />

in 1938. The table has been so arranged as to give an indication <strong>of</strong><br />

which Officers served together in each period.<br />

TABLE No 3:<br />

<strong>FIAF</strong>’s OFFICERS, 1938-1999<br />

President<br />

Abbott, John E<br />

1938-39<br />

Hensel, Frank<br />

1939-40<br />

Barry, Iris<br />

1946-48<br />

Toeplitz, Jerzy<br />

1948-72<br />

Pogacic, Vladimir<br />

1972-79<br />

Klaue, Wolfgang<br />

1979-85<br />

Wibom, Anna-Lena<br />

1985-89<br />

Daudelin, Robert<br />

1989-95<br />

Aubert, Michelle<br />

1995-99<br />

17 <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Film</strong> <strong>Preservation</strong> / <strong>56</strong> / 1998<br />

Secretary-General<br />

Langlois, Henri<br />

1938-40<br />

Langlois, Henri<br />

1946-48<br />

Barry, Iris<br />

1948-49<br />

Rognoni,<br />

Luigi<br />

1949-51<br />

Lindgren, Ernest<br />

1951-52<br />

Thirifays, André<br />

1952-55<br />

Langlois, Henri<br />

1955-57<br />

Buache, Freddy<br />

1957-58<br />

Thirifays, André<br />

1958-59<br />

Langlois, Henri<br />

1959-60<br />

De Vaal, Jan<br />

1960-61<br />

Ledoux, Jacques<br />

1961-78<br />

Borde, Raymond<br />

1978-79<br />

Daudelin, Robert<br />

1979-85<br />

Cincotti, Guido<br />

1985-89<br />

Orbanz, Eva<br />

1989-95<br />

Smither, Roger<br />

1995-99<br />

Treasurer<br />

Vaughan, Olwen<br />

1938-40<br />

Lindgren, Ernest<br />

1946-48<br />

Brusendorff, Ove<br />

1948-52<br />

Sales Gomes, Paulo E<br />

1952-53<br />

Lauritzen, Einar<br />

1953-55<br />

Buache, Freddy<br />

1955-<strong>56</strong><br />

Thirifays, André<br />

19<strong>56</strong>-58<br />

Lauritzen, Einar<br />

1958-63<br />

De Vaal, Jan<br />

1963-64<br />

Lauritzen, Einar<br />

1964-65<br />

De Vaal, Jan<br />

1965-66<br />

Morris, Peter<br />

1966-69<br />

Geber, Nils-Hugo<br />

1969-70<br />

Konlechner, Peter<br />

1970-73<br />

Stenklev, Jon<br />

1973-77<br />

De Vaal, Jan<br />

1977-85<br />

Borde, Raymond<br />

1985-91<br />

Wibom, Anna-Lena<br />

1991-93<br />

Jeavons, Clyde<br />

1993-95<br />

Bandy, Mary Lea<br />

1995-99

80 Days:<br />

Discoveries from a unique collection<br />

Historical Column / Chronique historique<br />

Brian Taves<br />

The organizing and cataloging <strong>of</strong> a valuable collection at the Library <strong>of</strong><br />

Congress has led to new discoveries about the filming <strong>of</strong> the definitive<br />

version <strong>of</strong> Jules Verne’s classic 1873 novel, Le Tour du monde en quatrevingt<br />

jours: Michael Todd’s adventure-comedy spectacular, Around the<br />

World in 80 Days, first released in 19<strong>56</strong>.<br />

Around the World in 80 Days was the culmination <strong>of</strong> showman Michael<br />

Todd’s life; he died at age 50 in an airplane crash March 22, 1958, just as<br />

his film was breaking box-<strong>of</strong>fice records and winning awards from all<br />

over the globe. Todd’s widow was the actress Elizabeth Taylor. Nearly a<br />

quarter-century after Todd’s death, while Taylor was married to John<br />

Warner, a United States Senator from Virginia, she donated the film<br />

footage that she had inherited from Todd to the Library <strong>of</strong> Congress.<br />

This was an appropriate decision, since the Library has one <strong>of</strong> the<br />

world’s largest collections relating to Jules Verne, and certainly the most<br />

extensive holdings <strong>of</strong> Verne film and television adaptations <strong>of</strong> any<br />

archive in the world. The Verne films at the Library <strong>of</strong> Congress are<br />

highlighted by such rarities as the 1914 version <strong>of</strong> Michael Strog<strong>of</strong>f, the<br />

first feature-length film adaptation <strong>of</strong> a Verne story, and the recent<br />

restoration <strong>of</strong> With Williamson beneath the Sea, the 1932 filmed autobiography<br />

<strong>of</strong> the pioneer <strong>of</strong> undersea photography who codirected Twenty<br />

Thousand Leagues under the Sea (1916) and The Mysterious Island (1929)<br />

(see ‘<strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Film</strong> <strong>Preservation</strong>’, 52 [April 1996], 52-61).<br />

The collection <strong>of</strong> Around the World in 80 Days footage consists <strong>of</strong> 426<br />

reels <strong>of</strong> picture and sound track material, in several languages, in 16<br />

mm., 35 mm., and 70 mm. The footage varies from preliminary rough<br />

cut “workprints” to production elements, preprints, color separations,<br />

tests, shots <strong>of</strong> the premieres, and “behind-the-scenes” footage. The<br />

footage includes portions <strong>of</strong> the original 1957 German, Italian, and<br />

French versions <strong>of</strong> Around the World in 80 Days, with the entire original<br />

French soundtrack. Other original soundtrack material is broken down<br />

into various components, such as music, sound effects, and dialogue.<br />

Among the movie’s special treats were the amusing concluding credits<br />

animated by Saul Bass and the superlative, soaring score by Victor<br />

Young, perhaps the best he ever wrote, and the collection includes<br />

preprint material on both the Bass and Young contributions.<br />

Collections <strong>of</strong> this type, especially on a Hollywood feature, are unusual<br />

in film archives, which generally hold only a standard theatrical release<br />

print <strong>of</strong> a movie. As an independent production, released through<br />

United Artists, there was no studio to properly care for the Around the<br />

World in 80 Days footage. All <strong>of</strong> the material was stored in a warehouse<br />

during the years after Todd’s death, and came to the Library <strong>of</strong> Congress<br />

18 <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Film</strong> <strong>Preservation</strong> / <strong>56</strong> / 1998

in 1982 in many poorly identified or completely unmarked cans. At the<br />

time, no one on the staff <strong>of</strong> the Library’s Motion<br />

Picture/Broadcasting/Recorded Sound Division had sufficient expertise to<br />

sort, inventory, and identify the Around the World in 80 Days footage, and<br />

most <strong>of</strong> it was placed in storage. However, later the Library was able to<br />

take advantage <strong>of</strong> the special expertise <strong>of</strong> a member <strong>of</strong> the staff, Brian<br />

Taves, who had just coauthored ‘The Jules Verne Encyclopedia’ and is<br />

also writing a book on all 300 adaptations <strong>of</strong> Verne to movies and television<br />

worldwide.<br />

Michael Todd had been interested in Le Tour du monde en quatre-vingt<br />

jours since he briefly sponsored Orson Welles’s 1946 theatrical production,<br />

with music and lyrics by Cole Porter. Although Todd’s previous<br />

experience was in the stage, he realized that, in the mid-1950s, with<br />

audiences craving widescreen spectacles, Le Tour du monde en quatre-vingt<br />

jours was ideal for an epic treatment encompassing nearly all the story’s<br />

principal incidents in a three-hour running time. In mid-1954, Todd<br />

bought rights to film the novel that had been held for two decades by<br />

British producer Alexander Korda. At various times since the 1930s,<br />

Korda announced a production with Maurice Chevalier starring as<br />

Passepartout, then planned to work with on a film with Welles. Korda<br />

shot a portion <strong>of</strong> an animated feature version, Indian Fantasy (1939),<br />

preserved by the National <strong>Film</strong> Archive.<br />

Todd was also looking for a vehicle appropriate for his new film process,<br />

Todd-A0, developed in cooperation with the American Optical Labs. This<br />

was the era when new techniques, such as 3-D and Cinemascope, were<br />

hailed as a way for movies to <strong>of</strong>fer an experience with which television<br />

could not compete. One <strong>of</strong> the disadvantages <strong>of</strong> Cinemascope, used by<br />

Walt Disney to film 20,000 Leagues under the Sea in 1954, was that in using<br />

an anamorphic lens to squeeze a widescreen image onto standard 35 mm.<br />

stock, there was distortion at the edges <strong>of</strong> the frame, particularly noticeable<br />

in a panning shot. Todd-AO sought to supplant the anamorphic technique<br />

by creating, instead, an image photographed and projected on a<br />

larger, wider filmstock, doubling the 35 mm. width to 70 mm.<br />

The new 70 mm. process posed extraordinary technical challenges, especially<br />

for a neophyte film producer. Tests in the Taylor collection reveal<br />

that the question <strong>of</strong> how 70 mm. would photograph such necessities as<br />

miniature ship exteriors was an early concern. After a year <strong>of</strong> preparation,<br />

principal photography began in September 1955 and was completed<br />

at the end <strong>of</strong> the year, although various effects work and other<br />

shooting continued until April 19<strong>56</strong> (as indicated in cards in the collection<br />

that document each day’s filming among several units). As director<br />

Michael Anderson recalled to Brian Taves, shooting in 70 mm. was<br />

essentially blind, because it was impossible to see “dailies” on a regular<br />

basis, to view what had been shot the previous day and judge the work.<br />

Nor could there be any process shots with 70 mm., filling in the background<br />

<strong>of</strong> scenes. Anderson noted to Taves, “If you wanted to shoot the<br />

Indians attacking the train you had to have a real train, take the sides<br />

<strong>of</strong>f, mount a camera platform, get the train up to speed, then get the<br />

19 <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Film</strong> <strong>Preservation</strong> / <strong>56</strong> / 1998<br />

80 Days : Découvertes d’une collection<br />

unique.<br />

Around the World in 80 Days, sorti en<br />

19<strong>56</strong>, a été le point culminant de la vie du<br />

showman Michael Todd. Celui-ci disparut à<br />

l’âge de 50 ans dans un accident d’avion en<br />

1958, au moment même où son film<br />

pulvérisait tous les records du box-<strong>of</strong>fice et<br />

raflait de nombreux prix autour du globe.<br />

La veuve de Todd, Madame Elisabeth Taylor,<br />

presque 25 ans après, fit don du matériel<br />

qu’elle avait hérité de feu son mari à la<br />

Library <strong>of</strong> Congress. Ce fut un reflexe<br />

heureux, car la LC - qui par ailleurs<br />

conserve l’une des plus importantes<br />

collections des adaptations de Jules Verne au<br />

cinéma et à la télévision - était la mieux<br />

préparée pour recevoir et préserver ce<br />

matériel. Le fonds Taylor comprend une<br />

grande variété d’éléments tels que 426<br />

bobines d’image et de son, en plusieurs<br />

langues, en 16mm, 35mm et 70mm. Le<br />

matériel film comprend des rushes et copies<br />

de travail, des séparations de couleurs, tests,<br />

prises de vues des premières, tournages de<br />

plateau, et bien d’autres curiosités. Il<br />

constitue une source de documentation d’une<br />

valeur inestimable pour l’étude de la<br />

superproduction hollywoodienne de Michael<br />

Todd.

80 Days : Descubrimientos de una<br />

colección única<br />

La vuelta al mundo en 80 días, estrenada<br />

en 19<strong>56</strong>, fué el punto culminante de la vida<br />

del showman Michael Todd. Este,<br />

desapareció a los 50 años de edad en un<br />

accidente aéreo ocurrido en 1958, en el<br />

preciso momento en que el film pulverizaba<br />

los records de taquilla y se llevaba los<br />

mayores premios a través del mundo. La<br />

viuda de Todd, la señora Elisabeth Taylor,<br />

25 años más tarde, legó todo el material que<br />

había heredado de su difunto esposo a la<br />

Library <strong>of</strong> Congress. Se trata de un acto<br />

feliz, ya que la LC - que por otra parte<br />

detiene una de las más importantes<br />

colecciones de adaptaciones de la obra de<br />

Jules Verne al cine y a la televisión - estaba<br />

bien preparada para recibir y preservar este<br />

material. El Fondo Taylor está integrado de<br />

una gran variedad de elementos tales como<br />

426 bobinas de imagen y de sonido, en<br />

varios idiomas, en en 16mm, 35mm et<br />

70mm. El material film consiste en rushes y<br />

copias de trabajo, separaciones de colores,<br />

tests, tomas, rodajes de estudio y numerosas<br />

curiosidades. La colección constituye una<br />

fuente de documentación de un valor<br />

inestimable para el estudio de la superproducción<br />

hollywoodiana de Michael Todd.<br />

horsemen up to speed outside and then say action to those playing the<br />

scenes in the railway carriage.”<br />

Making the schedule even more crowded was the necessity <strong>of</strong> shooting<br />

two versions <strong>of</strong> the film, one in 70 mm., and another in CinemaScope.<br />

At the time, it was impossible to transfer a film shot in 70 mm. to 35<br />

mm. widescreen stock, and a CinemaScope version was essential so that<br />

Around the World in 80 Days could play the many theaters only equipped<br />

to show 35 mm. film. Most scenes were shot with the two different cameras<br />

placed side by side, but sometimes scenes had to be reshot for the<br />

benefit <strong>of</strong> one or the other camera. Consequently, there are actually two<br />

different release versions <strong>of</strong> Around the World in 80 Days, and the Library’s<br />

collection holds print and preprint material on both.<br />

Todd found that raising financial backing necessary for the project was<br />

difficult, especially since he was a Hollywood outsider. Often the movie<br />

continued with just enough backing to keep progressing on a day-to-day<br />

basis. After the project had been underway for nine months and Todd<br />

was broke, he turned down <strong>of</strong>fers to buy him out, holding on until<br />

finally United Artists and Paramount Theaters came through with a<br />

releasing deal and the necessary funding to complete work.<br />

Humorist S.J. Perelman rewrote the script, staying very close to the<br />

Verne novel, although James Poe and John Farrow (who was also originally<br />

set to direct) sued and won a share <strong>of</strong> credit for authoring the original<br />

draft. Associate producer was the talented William Cameron<br />

Menzies, who selected the exteriors in Europe and the United States.<br />

Kevin O’Donovan McClory, who began as an assistant director, became<br />

steadily more important to the production and was ultimately also credited<br />

as associate producer. McClory directed scenes in Paris, the Middle<br />

East, Pakistan, Siam, Hong Kong, and Japan, before assisting in the editing<br />

<strong>of</strong> the 680,000 feet <strong>of</strong> film exposed during the summer <strong>of</strong> 19<strong>56</strong>.<br />

The expected budget doubled to $6 million as filming took place in 112<br />

locations in 13 countries over 127 days <strong>of</strong> shooting (75 days for principal<br />

photography under Anderson), employing, supposedly, nearly<br />

70,000 people and 8,000 animals. In the United States, the principal<br />

locations outside California were in Oklahoma and New Mexico, and<br />

five Hollywood studio lots were used, with the bulk <strong>of</strong> the interiors shot<br />

at RKO.<br />

The result is what Todd called a show on film: a travelogue, a circus, a<br />

revue, a comedy, a mystery, a romance, a Wild West show, and a bullfight<br />

all rolled into one. Yet, unlike many such enormous productions,<br />

Around the World in 80 Days does not seem heavy, but light and charming;<br />

the awesome scale seldom dwarfs the story and characters.<br />

Apparently most <strong>of</strong> the leads were chosen with relative ease, and David<br />

Niven was quickly selected for the part <strong>of</strong> Phileas Fogg. By retaining<br />

Verne’s satire <strong>of</strong> English manners and mores in the portrayal <strong>of</strong> Fogg, the<br />